Submitted:

27 October 2023

Posted:

30 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- In Section 3 we propose a conditional independence test for functional data that combines a novel test statistic based on hscic with cpt to generate samples under the null hypothesis. The algorithm also searches for the optimised regularisation strength required to compute hscic, by pre-test permutations and calculating an evaluation rejection rate.

- In Section 4.1.2, we extend the historical functional linear model [19] to the multivariate case () for regression-based causal structure learning, and we show how a joint independence test can be used to verify candidate directed acyclic graph (dags) [20, § 5.2] that embed the causal structure of function-valued random variables. This model has been contributed to the Python package scikit-fda [21].

- On synthetic data, we show empirically that our bivariate, joint and conditional independence tests achieve high test power, and that our causal structure learning algorithms outperform previously proposed methods.

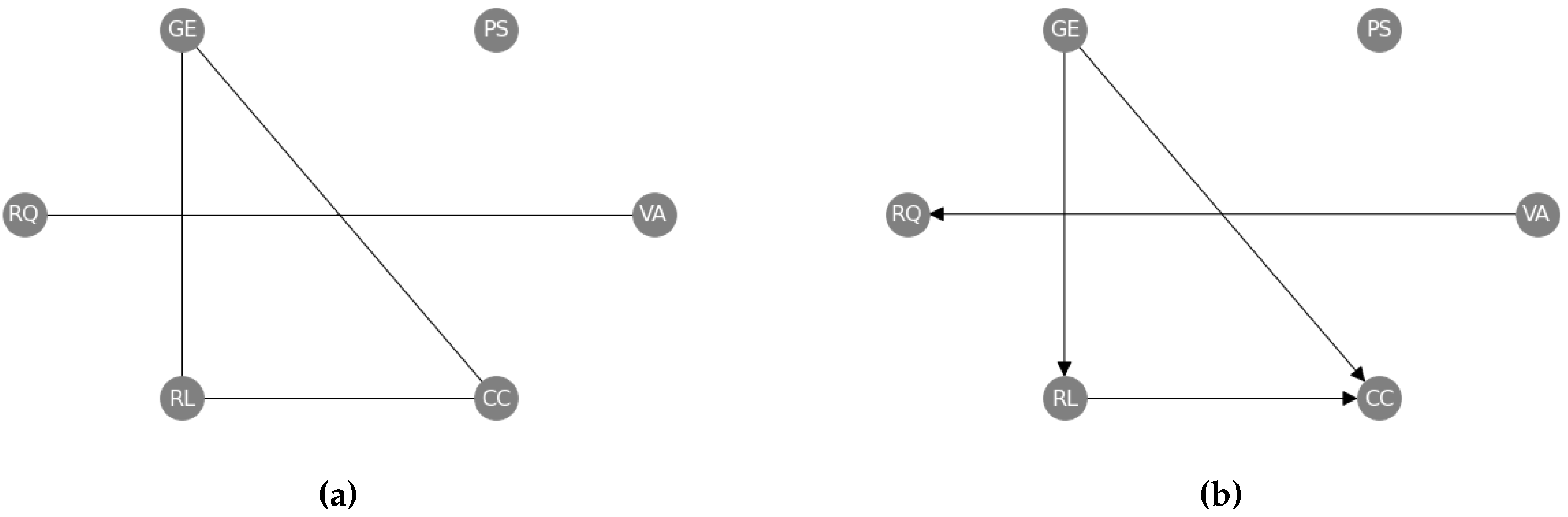

- Using a real-world data set (World Governance Indicators) we demonstrate how our method can yield insights into cause-effect relationships amongst socio-economic variables measured in every country worldwide.

- Implementations of our algorithms are made available at https://github.com/felix-laumann/causal-fda/ in an easily usable format that builds on top of scikit-fda and causaldag [22].

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Functional Data Analysis

2.2. Kernel Independence Tests

2.3. Causal Structure Learning

- Score-based approaches assign a score, such as a penalised likelihood, to each candidate graph and then pick the highest scoring graph(s). A common drawback of score-based approaches is the need for a combinatorial enumeration of all dags in the optimisation, although greedy approaches have been proposed to alleviate such issues [40].

- Constraint-based methods start by characterising the set of conditional independences in the observed data [13]. They then determine the graph(s) consistent with the detected conditional independences by using a graphical criterion called d-separation, as well as the causal Markov and faithfulness assumptions, which establish a one-to-one connection between d-separation and conditional independence (see Appendix D for definitions). When only observational i.i.d. data are available, this yields a so-called Markov equivalence class, possibly containing multiple candidate graphs. For example, the graphs , , and are Markov equivalent, as they all imply and no other conditional independence relations.

- Regression-based approaches directly fit the structural equations of an underlying scm for each , where denote the parents of in the causal dag and are jointly independent exogenous noise variables. Provided that the function class of the is sufficiently restricted, e.g., by considering only linear relationships [41] or additive noise models [42], the true causal graph is identified as the unique choice of parents for each i such that the resulting residuals are jointly independent.

3. Methods

3.1. Conditional Independence Test on Functional Data

| Algorithm 1 Search for with subsequent conditional independence test |

|

3.2. Causal Structure Learning on Functional Data

3.2.1. Constraint-Based Causal Structure Learning

3.2.2. Regression-Based Causal Structure Learning

4. Experiments

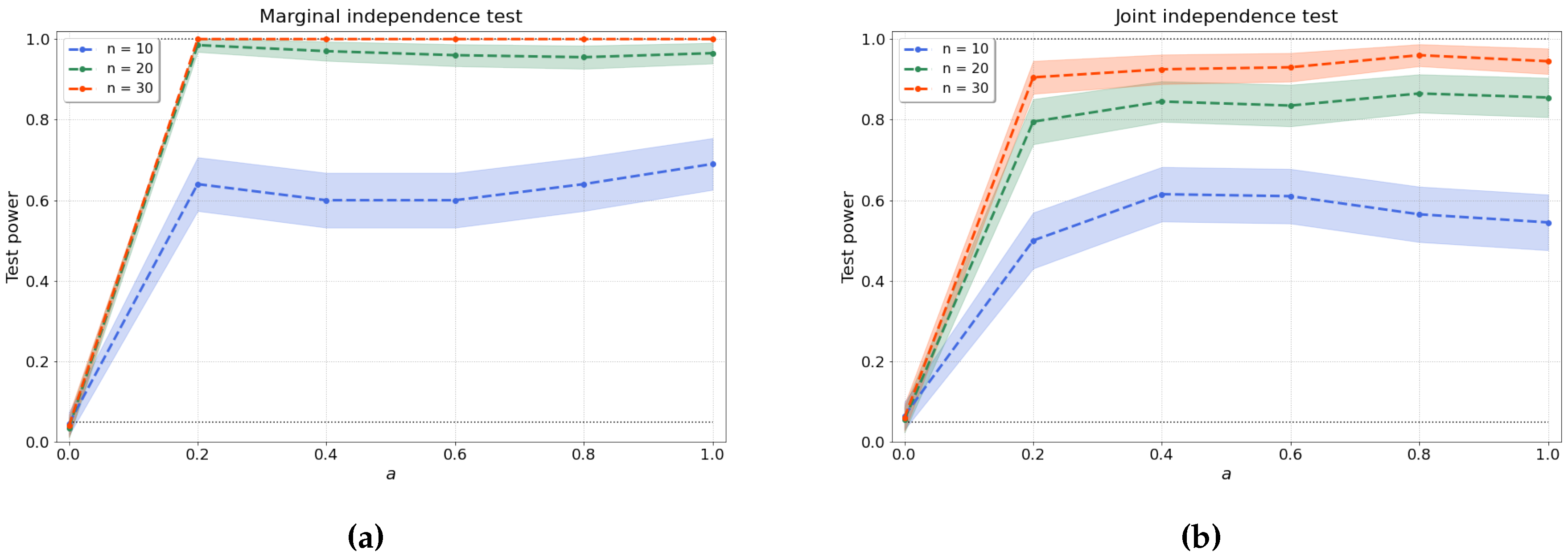

4.1. Evaluation of Independence Tests for Functional Data

4.1.1. Bivariate Independence Test

4.1.2. Joint Independence Test

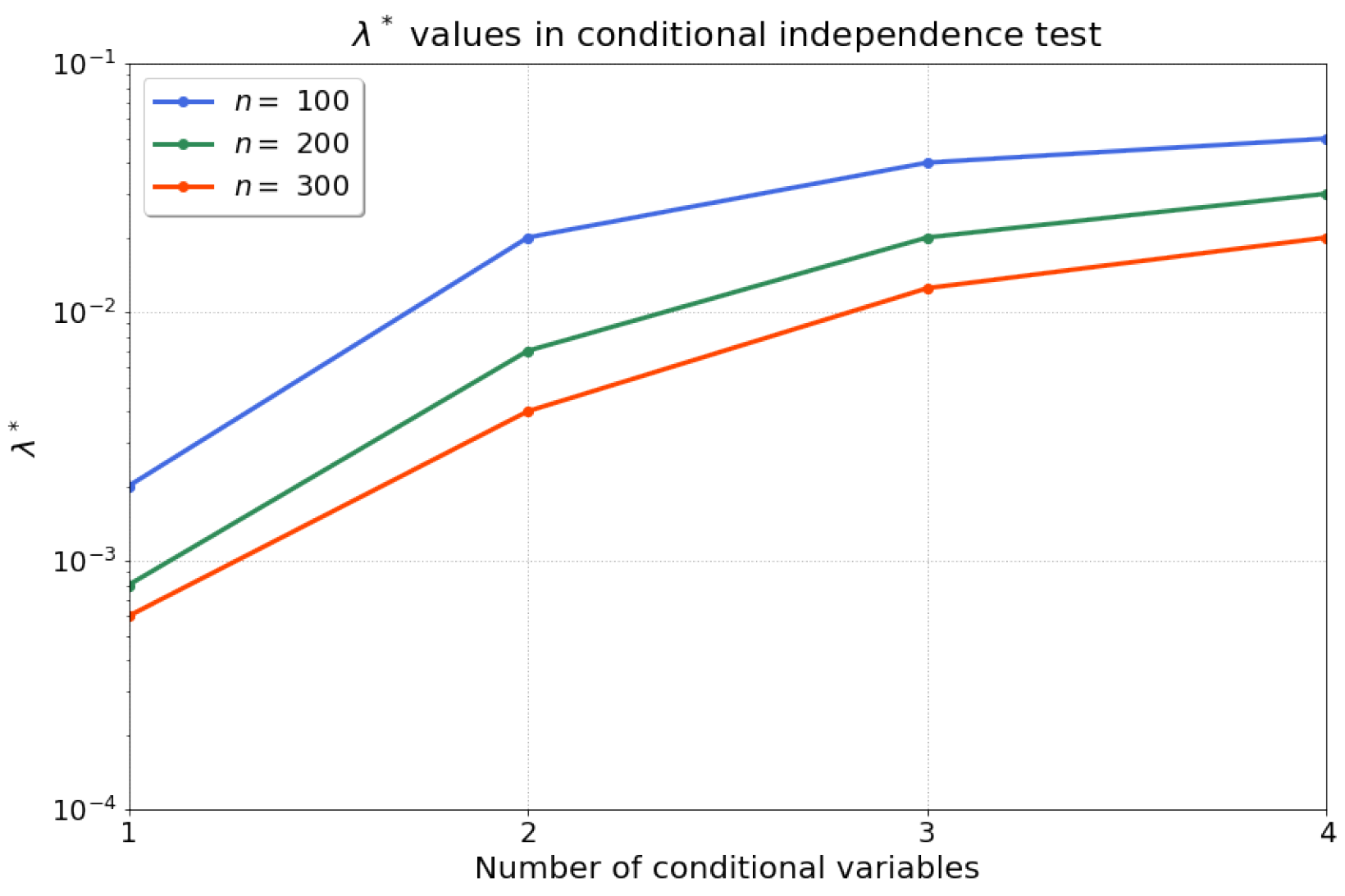

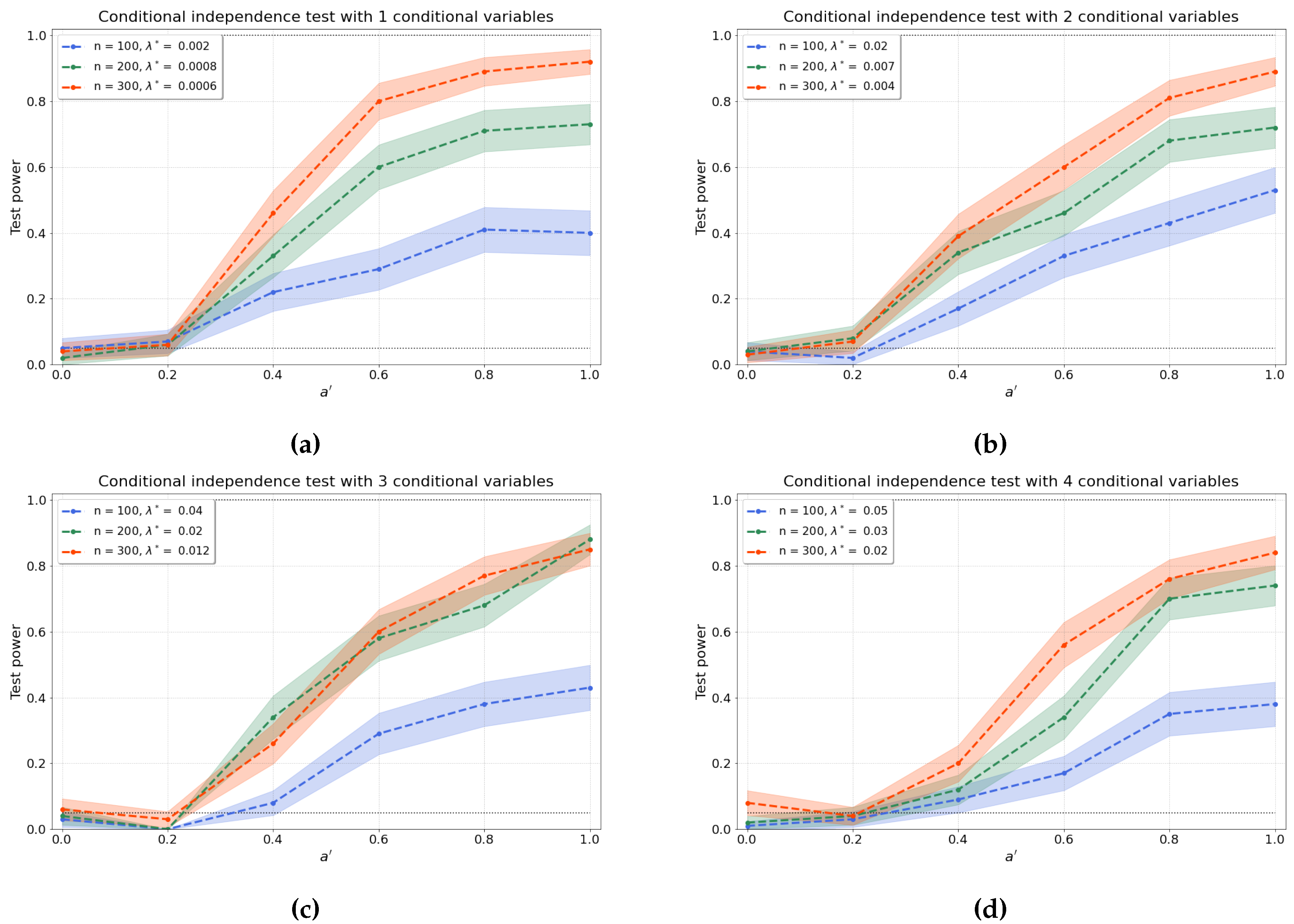

4.1.3. Conditional Independence Test

4.2. Causal Structure Learning

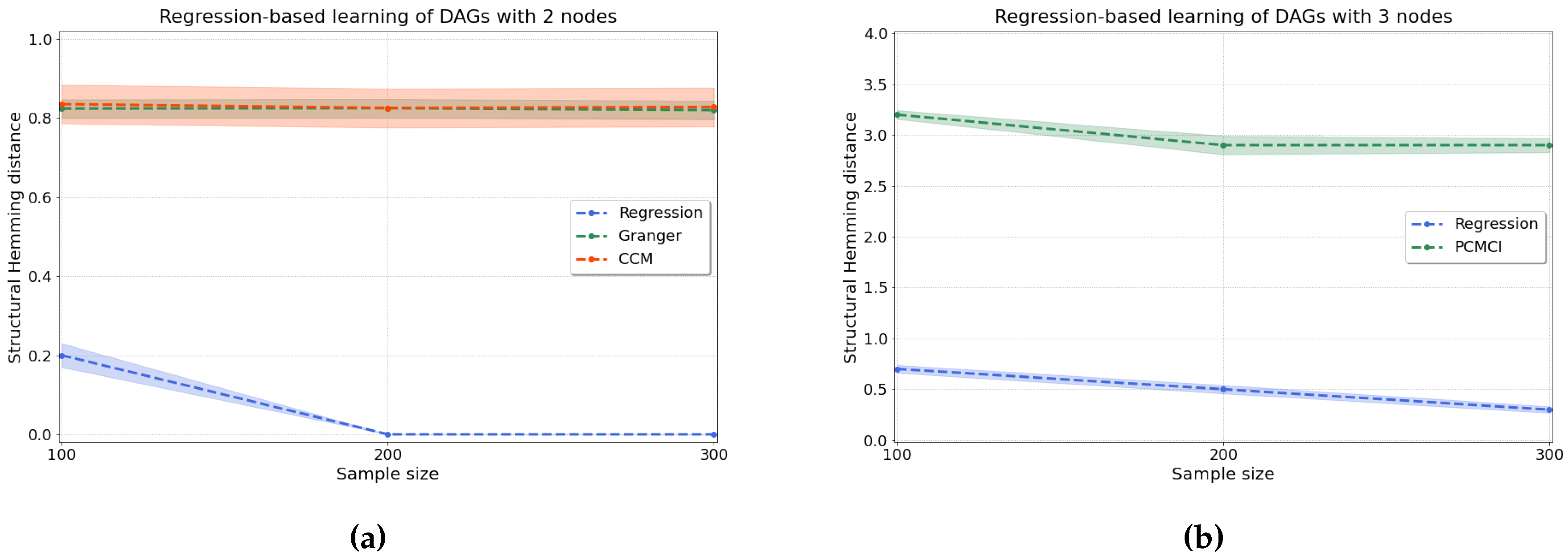

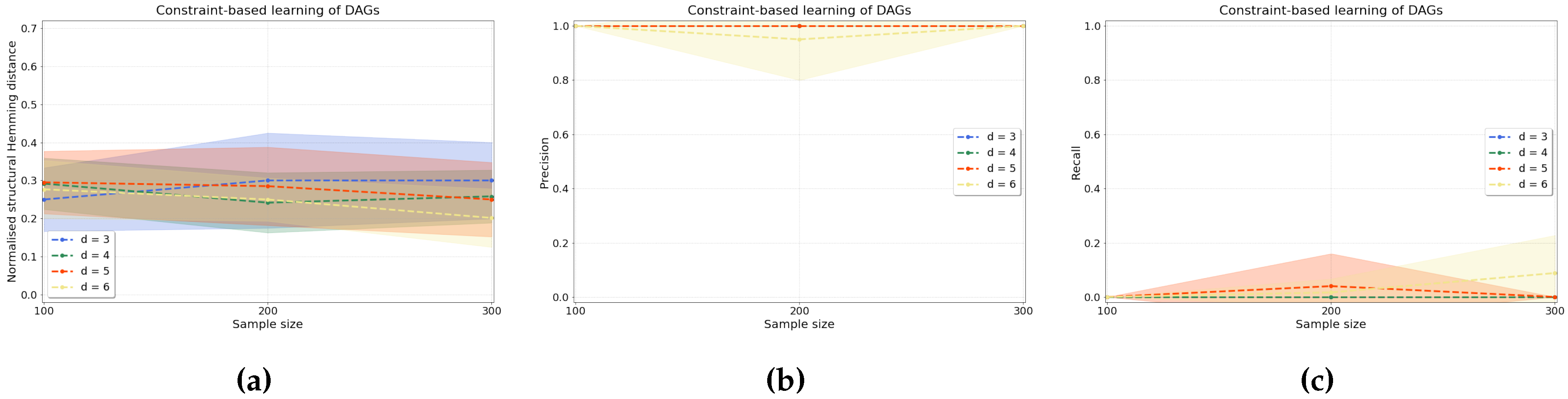

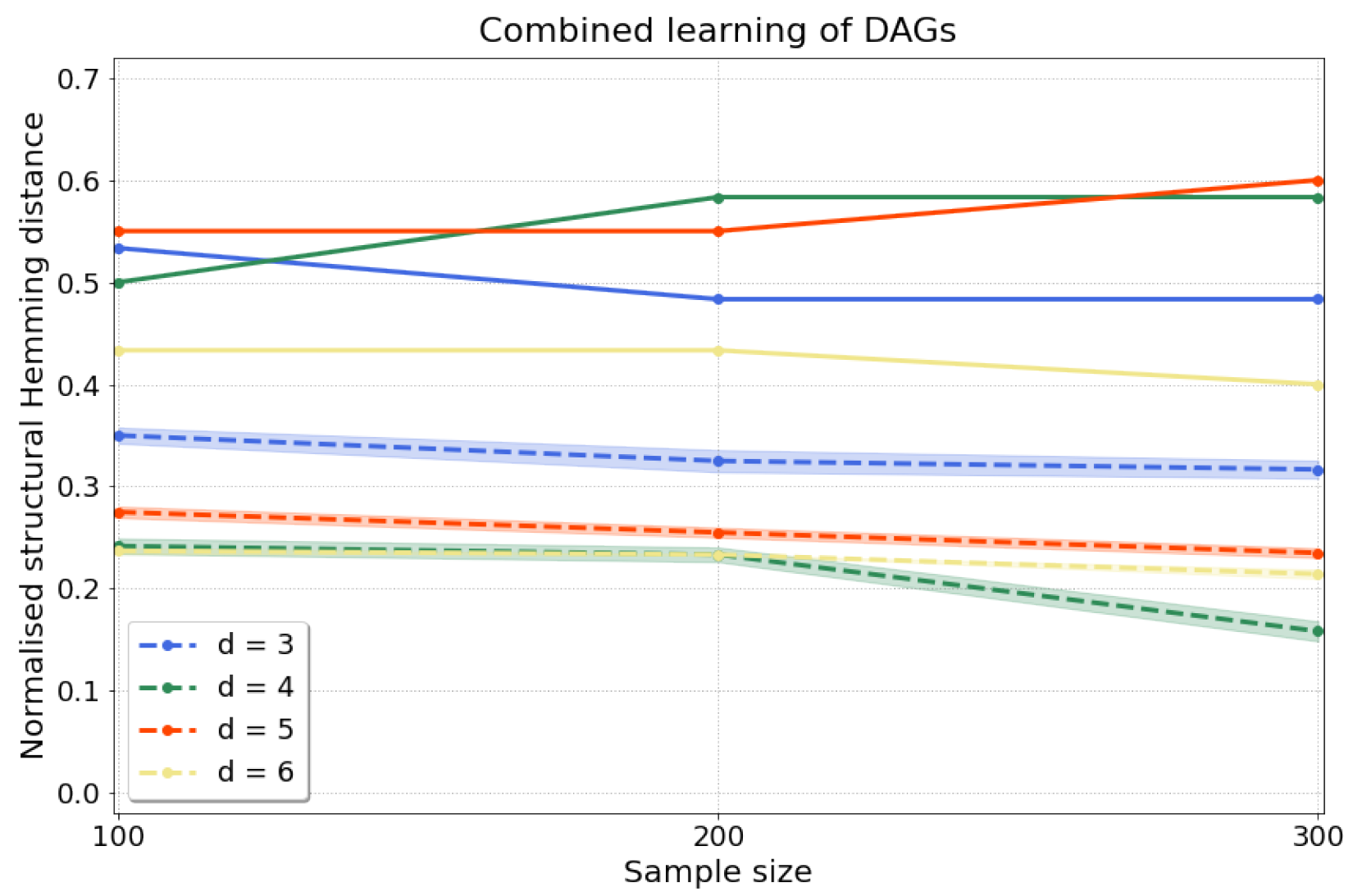

4.2.1. Synthetic Data

4.2.2. Real-World Data

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Appendix A. Data

Appendix A.1. Fourier Basis Functions

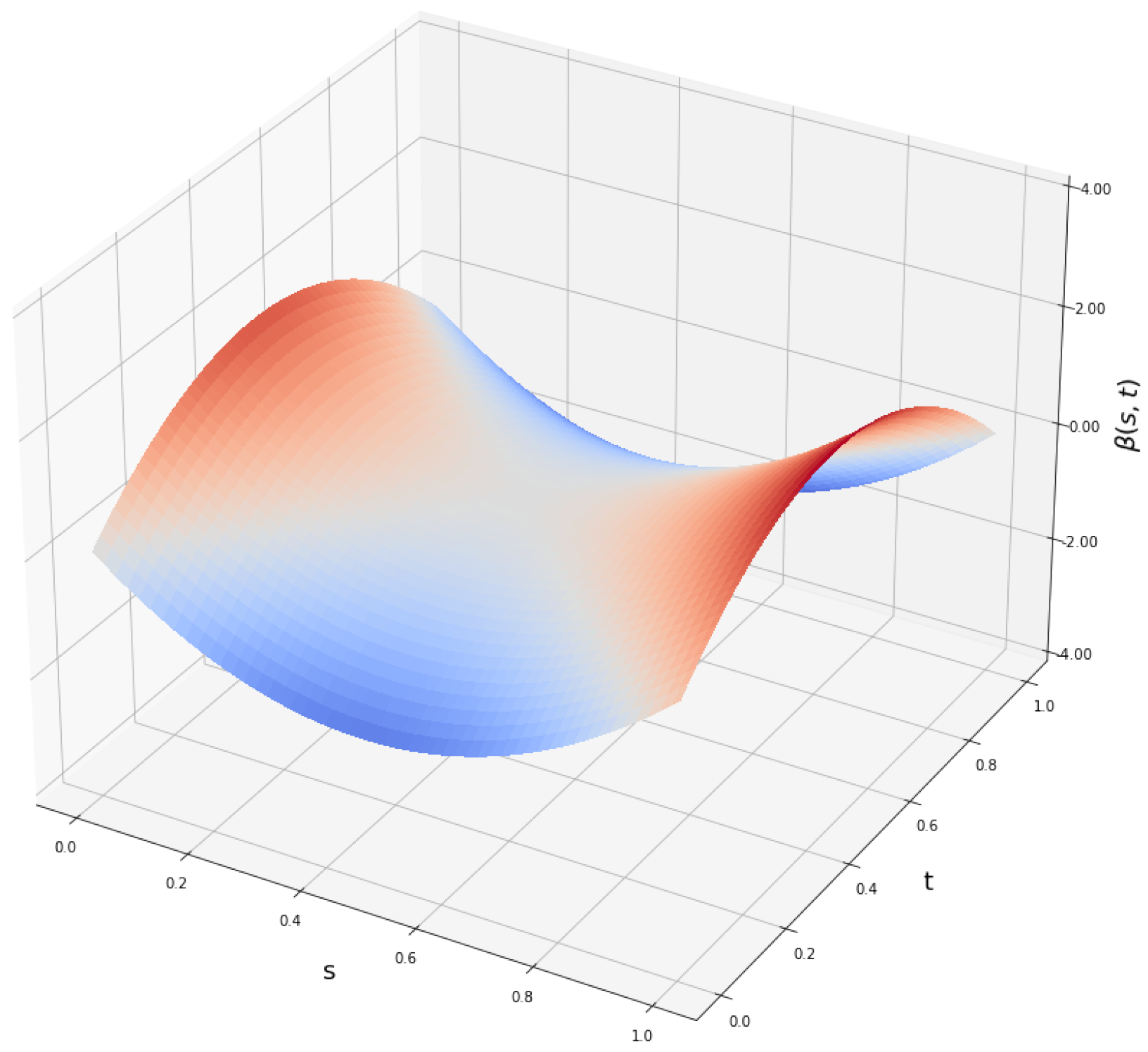

Appendix A.2. Lower and Upper Bounds of β-Functions

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.75 | |

| 0.25 | 0.75 |

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 1

Appendix C. Supplementary Information about Computational Complexity

Appendix D. Supplementary Definitions

Appendix D.1. D-Separation

Appendix D.2. Faithfulness Assumption

Appendix D.3. Causal Markov Assumption

Appendix E. Definitions of Metrics

Appendix E.1. shd

Appendix E.2. Normalised shd

Appendix E.3. Precision

Appendix E.4. Recall

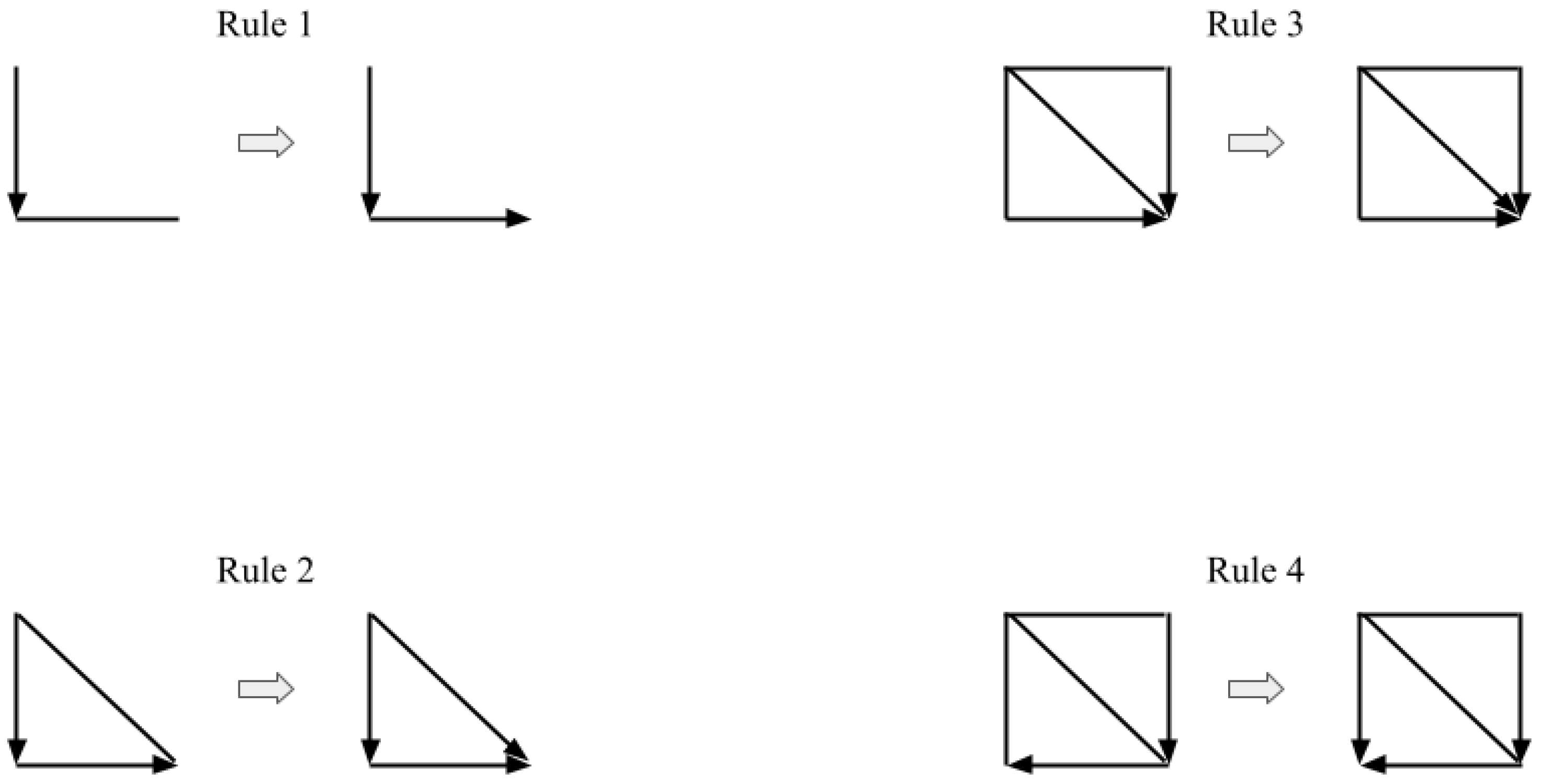

Appendix F. Meek’s Orientation Rules, the SGS and the PC Algorithms

- Form the complete undirected graph G from the set of vertices (or nodes) .

- For each pair of vertices X and Y, if there exists a subset S of such that X and Y are d-separated, i.e., conditionally independent (causal Markov condition), given Z, remove the edge between X and Y from G.

- Let K be the undirected graph resulting from the previous step 2. For each triple of vertices X, Y, and Z such that the pair X and Y and the pair Y and Z are each adjacent in K (written as ) but the pair X and Z are not adjacent in K, orient as if and only if there is no subset S of Y that d-separates X and Z.

-

Repeat the following steps until no more edges can be oriented:

- (a)

- If , Y and Z are adjacent, X and Z are not adjacent, and there is no arrowhead of other vertices at Y, then orient as (Rule 1 of Meek’s orientation rules).

- (b)

- If there is a directed path over some other vertices from X to Y, and an edge between X and Y, then orient as (Rule 2 of Meek’s orientation rules).

Appendix G. Comparison Methods

Appendix G.1. Granger-Causality

Appendix G.2. ccm

Appendix G.3. pcmci

Appendix H. World Governance Indicators

| Abbreviation | Official Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VA | Voice and Accountability | Voice and accountability captures perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. |

| PS | Political Stability and No Violence | Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism measures perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically-motivated violence, including terrorism. |

| GE | Government Effectiveness | Government effectiveness captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. |

| RQ | Regulatory Quality | Regulatory quality captures perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. |

| RL | Rule of Law | Rule of law captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. |

| CC | Control of Corruption | Control of corruption captures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as "capture" of the state by elites and private interests. |

References

- Runge, J.; Bathiany, S.; Bollt, E.; Camps-Valls, G.; Coumou, D.; Deyle, E.; Glymour, C.; Kretschmer, M.; Mahecha, M.D.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; et al. Inferring causation from time series in Earth system sciences. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulemana, I.; Kpienbaareh, D. An empirical examination of the relationship between income inequality and corruption in Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy 2018, 60, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkle, J.D.; Wu, J.J.; Bagheri, N. Windowed granger causal inference strategy improves discovery of gene regulatory networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 2252–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glymour, C.; Zhang, K.; Spirtes, P. Review of causal discovery methods based on graphical models. Frontiers in genetics 2019, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, J.O.J.O. Functional Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.W. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1969, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, G.; May, R.; Ye, H.; Hsieh, C.h.; Deyle, E.; Fogarty, M.; Munch, S. Detecting causality in complex ecosystems. science 2012, 338, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues1. Hague journal on the rule of law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Gini index. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jong-Sung, Y.; Khagram, S. A comparative study of inequality and corruption. American sociological review 2005, 70, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Angeletos, G.M. Corruption, inequality, and fairness. Journal of Monetary Economics 2005, 52, 1227–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, S.; Ramlogan-Dobson, C. Is there a trade-off between income inequality and corruption? Evidence from Latin America. Economics letters 2010, 107, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirtes, P.; Glymour, C.N.; Scheines, R.; Heckerman, D. Causation, Prediction, and Search. MIT Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Mooij, J.M.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B. Causal discovery with continuous additive noise models. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2014, 15, 2009–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Muandet, K.; Fukumizu, K.; Sriperumbudur, B.; Schölkopf, B.; et al. Kernel mean embedding of distributions: A review and beyond. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2017, 10, 1–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, G.; Duncan, A.B. A kernel two-sample test for functional data. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Muandet, K. A measure-theoretic approach to kernel conditional mean embeddings. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.03689 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berrett, T.B.; Wang, Y.; Barber, R.F.; Samworth, R.J. The conditional permutation test for independence while controlling for confounders. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2020, 82, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfait, N.; Ramsay, J.O. The historical functional linear model. Canadian Journal of Statistics 2003, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfister, N.; Bühlmann, P.; Schölkopf, B.; Peters, J. Kernel-based tests for joint independence. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 2018, 80, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Carreño, C.; Suárez, A.; Torrecilla, J.L.; Carbajo Berrocal, M.; Marcos Manchón, P.; Pérez Manso, P.; Hernando Bernabé, A.; García Fernández, D.; Hong, Y.; Rodríguez-Ponga Eyriès, P.M.; et al. GAA-UAM/scikit-fda: Version 0.7.1. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, C. causaldag: creation, manipulation, and learning of causal models. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, O.; Lattier, G.; Micallef, J.P.; Millet, G.P. Changes in exercise characteristics, maximal voluntary contraction, and explosive strength during prolonged tennis playing. British journal of sports medicine 2006, 40, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Kuhn, T.; Mayo, P.; Hinds, W.C. Comparison of daytime and nighttime concentration profiles and size distributions of ultrafine particles near a major highway. Environmental science & technology 2006, 40, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, J.; Hooker, G. Dynamic Data Analysis. Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fukumizu, K.; Gretton, A.; Sun, X.; Schölkopf, B. Kernel Measures of Conditional Dependence. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Platt, J.C., Koller, D., Singer, Y., Roweis, S., Eds.; Red Hook, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 20, pp. 489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Gretton, A.; Fukumizu, K.; Teo, C.H.; Song, L.; Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. A kernel statistical test of independence. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2008; pp. 585–592. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Peters, J.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B. Kernel-based conditional independence test and application in causal discovery. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1202.3775 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kong, L. Testing independence of functional variables by angle covariance. Journal of Multivariate Analysis 2021, 182, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, T.; Krzyśko, M.; Wołyński, W. Independence test and canonical correlation analysis based on the alignment between kernel matrices for multivariate functional data. Artificial Intelligence Review 2020, 53, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, G.; Muandet, K.; Zhang, K.; Schölkopf, B. A Permutation-Based Kernel Conditional Independence Test. In Proceedings of the UAI. Citeseer; 2014; pp. 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Gretton, A.; Borgwardt, K.M.; Rasch, M.J.; Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A. A kernel two-sample test. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2012, 13, 723–773. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Honavar, V.G. Self-discrepancy conditional independence test. In Proceedings of the Uncertainty in artificial intelligence; 2017; Voulme 33. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality; Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mooij, J.M.; Peters, J.; Janzing, D.; Zscheischler, J.; Schölkopf, B. Distinguishing cause from effect using observational data: methods and benchmarks. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2016, 17, 1103–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B. Elements of Causal Inference; The MIT Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf, B.; von Kügelgen, J. From statistical to causal learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.00607 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Squires, C.; Uhler, C. Causal structure learning: a combinatorial perspective. In Foundations of Computational Mathematics; 2022; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vowels, M.J.; Camgoz, N.C.; Bowden, R. D’ya like dags? a survey on structure learning and causal discovery. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickering, D.M. Optimal structure identification with greedy search. Journal of machine learning research 2002, 3, 507–554. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, S.; Hoyer, P.O.; Hyvärinen, A.; Kerminen, A.; Jordan, M. A linear non-Gaussian acyclic model for causal discovery. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2006, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, P.; Janzing, D.; Mooij, J.M.; Peters, J.; Schölkopf, B. Nonlinear causal discovery with additive noise models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2008, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, Z.; Sriperumbudur, B.K. Characteristic and Universal Tensor Product Kernels. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Meek, C. Complete Orientation Rules for Patterns; Carnegie Mellon [Department of Philosophy], 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Mooij, J.; Janzing, D.; Schölkopf, B. Identifiability of causal graphs using functional models. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1202.3757 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bühlmann, P.; Peters, J.; Ernest, J. CAM: Causal additive models, high-dimensional order search and penalized regression. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.D.; Peters, J.; et al. The hardness of conditional independence testing and the generalised covariance measure. Annals of Statistics 2020, 48, 1514–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, J.; Nowack, P.; Kretschmer, M.; Flaxman, S.; Sejdinovic, D. Detecting and quantifying causal associations in large nonlinear time series datasets. Science advances 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, C. On the measure of concentration with special reference to income and statistics. Colorado College Publication, General Series 1936, 208, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vaart, A.W. Asymptotic Statistics; Cambridge University Press, 2000; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Bühlmann, P. Structural intervention distance for evaluating causal graphs. Neural computation 2015, 27, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Munch, E.; Khasawneh, F.; Myers, A.; Yesilli, M.; Tymochko, S.; Barnes, D.; Guzel, I.; Chumley, M. teaspoon: Topological Signal Processing in Python. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, G.J.; Rizzo, M.L.; Bakirov, N.K. Measuring and testing dependence by correlation of distances. 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).