1. Introduction

Tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum L.) belongs to the Solanaceae family and is one of the most widely grown and consumed horticultural crops worldwide [

1]. According to [

2] the production of tomatoes exceeds 5 million hectares annually, which makes them a key horticultural crop globally. Tomato is a nutritious and valuable food containing various bioactive compounds, including carotenoids (notably lycopene and ß-carotene), ascorbic acid (vitamin C), tocopherols (vitamin E), fibre, vitamin A, and polyphenolic compounds (such as phenols, flavonoids, and phenolic acids) [

1]. However, from the crop is infected by numerous fungal pathogens that adversely affect its production globally, leading to significant economic losses [

3]. These include

Rhizoctonia solani (Kuhn),

Fusarium spp., and

Pythium spp., causing seed rot, pre-emergence damping-off, and stem rot in greenhouses and field crops [

4]

Rhizoctonia solani is an aggressive necrotrophic plant pathogen, with a wide host range, including solanaceous crops, cereals, vegetables, cotton, cucurbits, ornamental plants and forest trees [

5], with Losses range from 20% to 40% worldwide [

6]. The fungus produces highly resistant sclerotia, enabling

R. solani to survive harsh environmental conditions.

R. solani is currently managed using fungicides, crop rotation, biological control agents, and resistant cultivars [

7,

8,

9]. Biological control is safe, eco-friendly, and efficient [

10]. The biological control of

R. solani on various crops has been extensively studied [

11,

12,

13].

Vermicompost is the product of utilising and degrading organic matter in soil, manure or compost by earthworms such as

Eisenia fetida (Savigny),

Eudrilus eugeniae (Kinberg), and

Perionyx excavatus (Perrier) [

14]. Treating livestock and poultry manure with earthworms can lead to effective bioenergy utilisation, reduced investment in environmental protection, and significantly decreased pathogens in the valuable manure. It is even more valuable because vermicompost may contain microorganisms that control soil-borne pathogens [

15,

16,

17]. The microbes in vermicompost may boost crop production, and play a role in maintaining soil structure stability. Various bacterial genera can be found in vermicompost, depending on environmental conditions and the raw materials used in the vermicomposting process [

18,

15,

19].

Biocontrol strains of

Bacillus spp. establish a protective biofilm layer and then generate a number of antimicrobial secondary metabolites that inhibit plant pathogens. These include antimicrobial peptides (AMP), volatile substances, and hydrolytic enzymes (such as chitinases, glucanases, and proteases). They may also compete with pathogens for resources or space requirements [

20,

21,

22].

This is the first study in Saudi Arabia aimed at screening vermicompost for antagonistic bacteria that have inhibitory effects on R. solani, identifying these bacteria, and investigating their potential to control R. solani in tomato plants under laboratory and greenhouse conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation Technique for Rhizoctonia Root Rot and Identification of R. solani

Tomato seedlings were observed that exhibited damping-off symptoms were processed for isolation. These were initially rinsed with tap water to eliminate soil debris from the roots. Small sections from the infected areas (usually the stem near the soil surface) were then excised. The plant tissue was surface sterilised through two successive treatments, each lasting one minute: first with a 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution, followed by sterile distilled water. The sterilized samples were then transferred onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium in Petri dishes (6mm), after excess water was removed using sterile filter paper. The dishes were then incubated at 25 ± 1°C for 2 days. Mycelia growing on the plates were transferred onto PDA slants using an inoculation needle, and incubated at 25 ± 1°C for a week [

23]. A similar method was used by [

9]. The identification of

R. solani was confirmed based on its distinct mycelial morphology [

24].

2.2. Vermicompost Sample Collection

Fresh vermicompost samples were collected from the vermicomposting unit at the National Organic Agriculture Center (NOAC), Qassim, Saudi Arabia (25°48′23″N 42°52′24″e). Nine samples, each weighing 0.5 kg, were collected using an auger. The samples were subsequently sieved to remove insects and other debris. All samples were stored at 4°C until used.

2.3. Isolation of Antagonistic Bacteria from Vermicompost and Screening for Their Inhibitory Effects on Rhizoctonia solani

A 10g sample of vermicompost from each type was weighed, added to a flask containing 90 ml of sterilized distilled water, and then shaken for 3 min to obtain a suspension stock of vermicompost. To make a dilution series, 1 ml of the suspension stock was added to a flask containing 9 ml of sterilized distilled water. A series of dilutions were prepared at 10-3, 10-4, and 10-5 of the original suspension. From each vermicompost sample, 0.1 ml of each dilution was applied to nutrient agar medium (NA) (Neogen, Ltd.). After 48 hrs incubation at 30°C, single colonies were picked for pure culture isolation [

25].

Bacterial isolates were screened for their ability to produce antifungal substances against R. solani using in vitro dual culture assays on (PDA) (Neogen, Ltd.). Each bacterial colony was inoculated 2.5 cm from the edge of a Petri dish (9 mm in diameter) at four evenly distributed spots (three plates per isolate). After 48 hours of incubation at 28°C in the dark, a 5-mm plug from the leading edge of a 15-day-old culture of R. solani grown on PDA was placed in the center of the plate. Plates without bacteria served as controls. The plates were incubated at 28°C for five days, after which the diameter of the fungal colony was measured, and the inhibition rate was calculated as follows:

Inhibition rate = ((colony diameter in Control − colony diameter in treatment) /colony diameter in Control) × 100%

2.4. In Vitro Antagonistic Activity Against R. solani

To determine the effects of various incubation times, the three best bacterial strains (NOAC.B77, NOAC.B42, and NOAC.B17) were assessed for their antagonistic activity against R. solani over time. Each strain was inoculated onto NA for 0, 1, 2, and 3 days, as described in

Section 2.3 Subsequently, 0.5 mm of

R. solani was added to each plate and incubated at 28°C. Three days of adding

R. solani at each specific time point, the inhibition (%) of the fungus on each plate was calculated, as outlined in

Section 2.3.

2.5. Morphological Changes in the Mycelium of R. solani Due to the Antagonistic Effect of Bacterial Strains

A thinner-than-normal layer of nutrient agar (NA) was prepared in Petri dishes, to ensure a clear view under the light microscope (Euromex, Netherlands). Three Petri dishes (9 mm in diameter), were utilised for each bacterial strain. The bacterial inoculum was introduced according to the methods outlined in

Section 2.3. After a three-day period, a 0.5 mm plug of

R. solani, which had been cultured for 15 days, was added to each Petri dish, while the Control treatment contained only

R. solani. All Petri dishes for each strain were examined to observe if there were any morphological changes in mycelial growth caused by the bacterial strain, in comparison with the Control treatment.

2.6. Plant Growth Promotion by Bacterial Strains

The plant-growth-promoting ability of the best biocontrol strains (NOAC.B17, NOAC.B42 and NOAC.B77) was tested using paper towels. Un treated Tomato seeds Var. Nurdan F1 (Argeto Vegetable Seeds, Turkey) were soaked in a bacterial suspension (1 × 10^8 CFU ml-1) for 3 hrs at 25°C. Three replicates were used for each strain. Ten seeds were used per replicate. The treated seeds were placed between two moist germination papers, rolled, and incubated at 25°C. Sterile distilled water was used to treat seeds in the Control treatment. After 15 days of incubation, the percentage germination, root length, and shoot length of the seedlings were recorded [

26]. A vigour index was calculated: = (mean root length + mean shoot length) × percentage germination [

27].

2.7. Root Colonization

To assess the colonization capability of the three best bacterial strains on tomato roots, tomato seeds of Var. Nurdan F1 were surface sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 1 minute, followed by two rinses in sterile distilled water. The seeds were then immersed in a bacterial cell suspension (10^8 CFU ml-1) and shaken for 20 minutes. The bacterial-coated seeds were placed on sterilized filter paper in Petri dishes and incubated at 25°C. Once the seeds had germinated and the primary roots had grown to approximately 5 cm, segments of 3–4 mm from the elongation zones were cut and transferred to NA medium. The test plates were incubated at 29°C for 3–5 days and monitored daily for the development of bacteria from the excised root elongation zones.

2.8. Identification of the Three Selected Bacterial Isolates

2.8.1. DNA Extraction and PCR Conditions

DNA of the bacteria was extracted as per [

28], with minor modifications. The three isolates were grown at 30ºC in a nutrient broth medium (Oxoid, Ltd.) for 24 hours. Cells were centrifuged for 3 minutes at 12,000 rpm and rinsed with Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 7.7). The cells were then re-dissolved in TE buffer (300 µl), heated at 95ºC for 10 minutes in a boiling water bath, cooled to room temperature, and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 8 minutes. The extracted DNA was transferred to a clean tube and stored at 4°C until PCR amplification. Thermo Scientific's DreamTaq™ Green PCR Master Mix (USA) was employed in 30 µl volumes to amplify 16S rDNA using the universal primers 27 F 5′- AGA GTT TGA TCA TGG CTC AG-3 and 1492 R 5′-TACG GTT ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT-3. To verify that the correct fragment size was amplified, PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel. These products were purified and sequenced in both directions (Macrogen, South Korea).

2.8.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

The maximum likelihood approach was used to infer the phylogenetic tree, using the following parameters: the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) methodology, the Tamura-Nei model, and the Neighbor-Joining method. The phylogenetic tree analysis was performed in MEGA 11 software [

29]. The obtained sequences were deposited at the GenBank (NCBI database) with accession numbers PP961956, PP961957 and KY034383.

2.9. Greenhouse Experiment

2.9.1. Preparation of Fungal Inoculum and Bacterial Isolates

The three selected bacterial isolates were cultured in nutrient broth at 30°C on a shaker for 48 hours. A bacterial suspension of (9 × 10^8 CFU ml-1) was prepared to be used in the experiment. To prepare

R. solani inoculum, 500 g of barley grain was washed and soaked overnight, then autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes, followed by a 24-hour cooling period at 22–25°C. Colonies of

R. solani were cultured on PDA, using the previously isolated strain of

R. solani (

Section 2.5). From a 15-day-old culture five squares of 0.05 x 0.05 mm of colonies of were added to the barley grain. The mixture was incubated for 15 days at 25°C, at which stage

R. solani had fully colonized the barley grains.

2.9.2. Pot Experiment Design

An in vivo experiment was conducted in a glasshouse to study the effect of the three selected bacterial isolates on damping-off of tomato seedlings caused by R. solani. The tomato cultivar used for the pot experiments was Var. Nurdan F1. The plants were grown in pots 28cm in diameter, filled with a peat-based artificial growing medium. The experiment was laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replicates of eight treatments. These were (1) B. subtilis (NOAC.B77), (2) B. cereus (NOAC.B17) (3) B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42), (4) B. subtilis (NOAC.B77) + R. solani, (5) B. cereus (NOAC.B17) + R. solani, (6) B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42) + R. solani (7) R. solani (Infected Control), and (8) Tomato seeds only (Untreated Control).

2.9.3. Inoculation Technique and Data Collection

A soil drench of 50 ml of the appropriate strain of bacterium was added to each pot, for Treatments 1-6. A pathogenic inoculum of 10g of barley grains colonized with R. solani was introduced into each pot of Treatments 4-7. Tomato seeds Var. Nurdan F1 were sown in pots at a rate of 15 seeds per pot, three days after the addition of the antagonistic bacteria. The percentage of germinated seeds was calculated after the seeds in the Untreated Control had fully germinated.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were compared using the Duncan’s multiple range test at a 5.0% level of significance. The analyses were conducted using GenStat for Windows, 23rd edition.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Antagonistic Bacteria from Vermicompost

Eighty five bacterial isolates were obtained from the collected vermicompost samples, and were then evaluated for their antagonistic effects against R. solani. Among the tested isolates, five were active in the dual culture method, and three exhibited antifungal activity against R. solani.

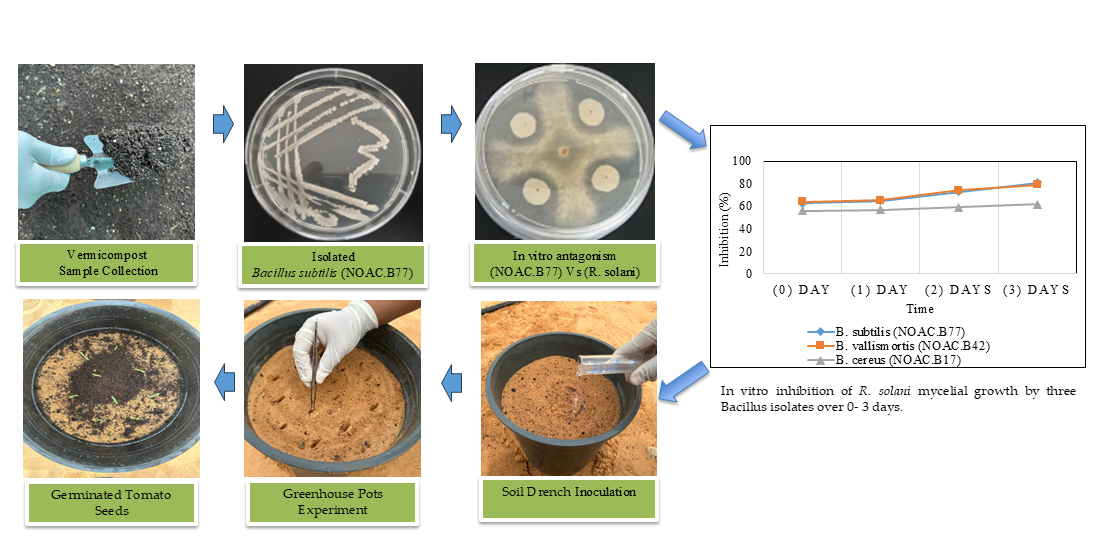

3.2. In Vitro Antagonistic Activity Against R. solani

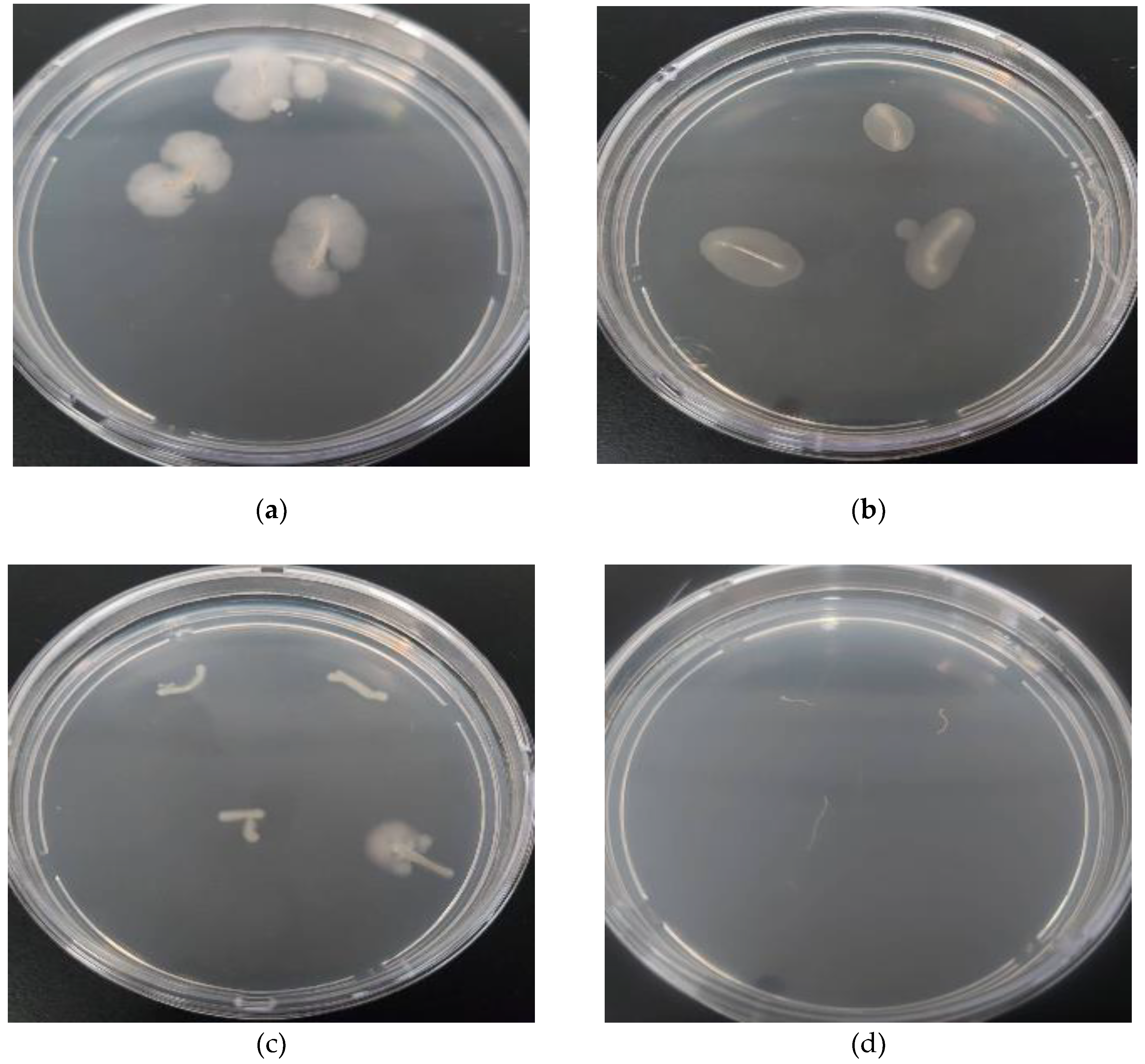

The selected bacterial isolates reduced the growth of

R. solani in culture (

Figure 1.) Significant differences among the tested isolates were observed at all exposure times after adding the bacterial inoculum, with inhibition percentages ranging from 56% to 65% for all isolates on zero and one day after the addition of the bacterial inoculum (

Table 1). A notable increase in inhibition percentages, reaching 79.15% and 80.78%, was noted by day three with B. subtilis (NOAC.B77) and

B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42), respectively.

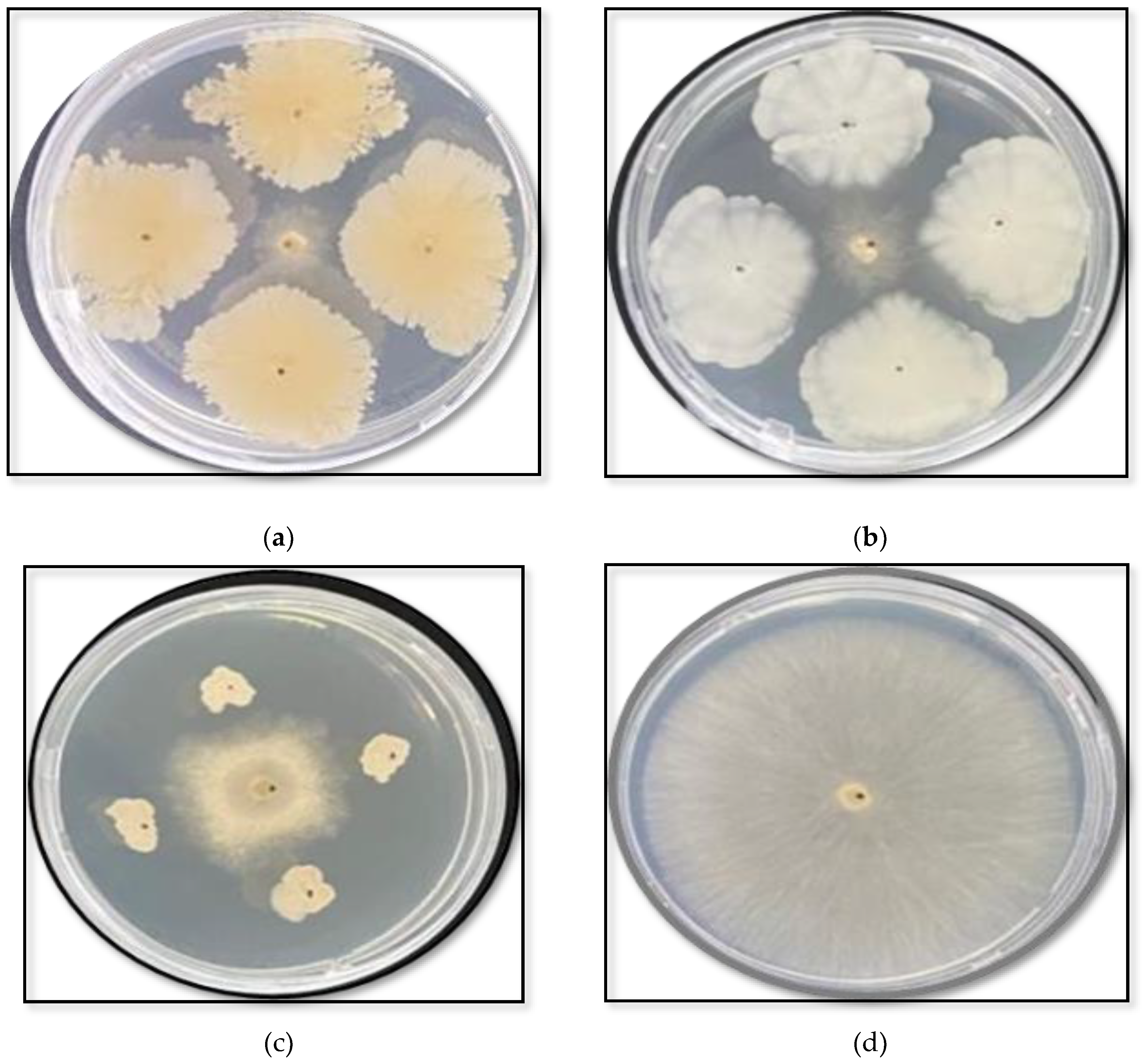

These results demonstrated the ability of the tested bacteria to produce inhibitory substances over time, comparing to the fungal colony measurements taken at zero, one and three days after inoculum addition (

Table 1). A linear response to increased inoculation times of bacterial isolates was observed across all tested isolates, with R² > 0.9. (

Figure 2).

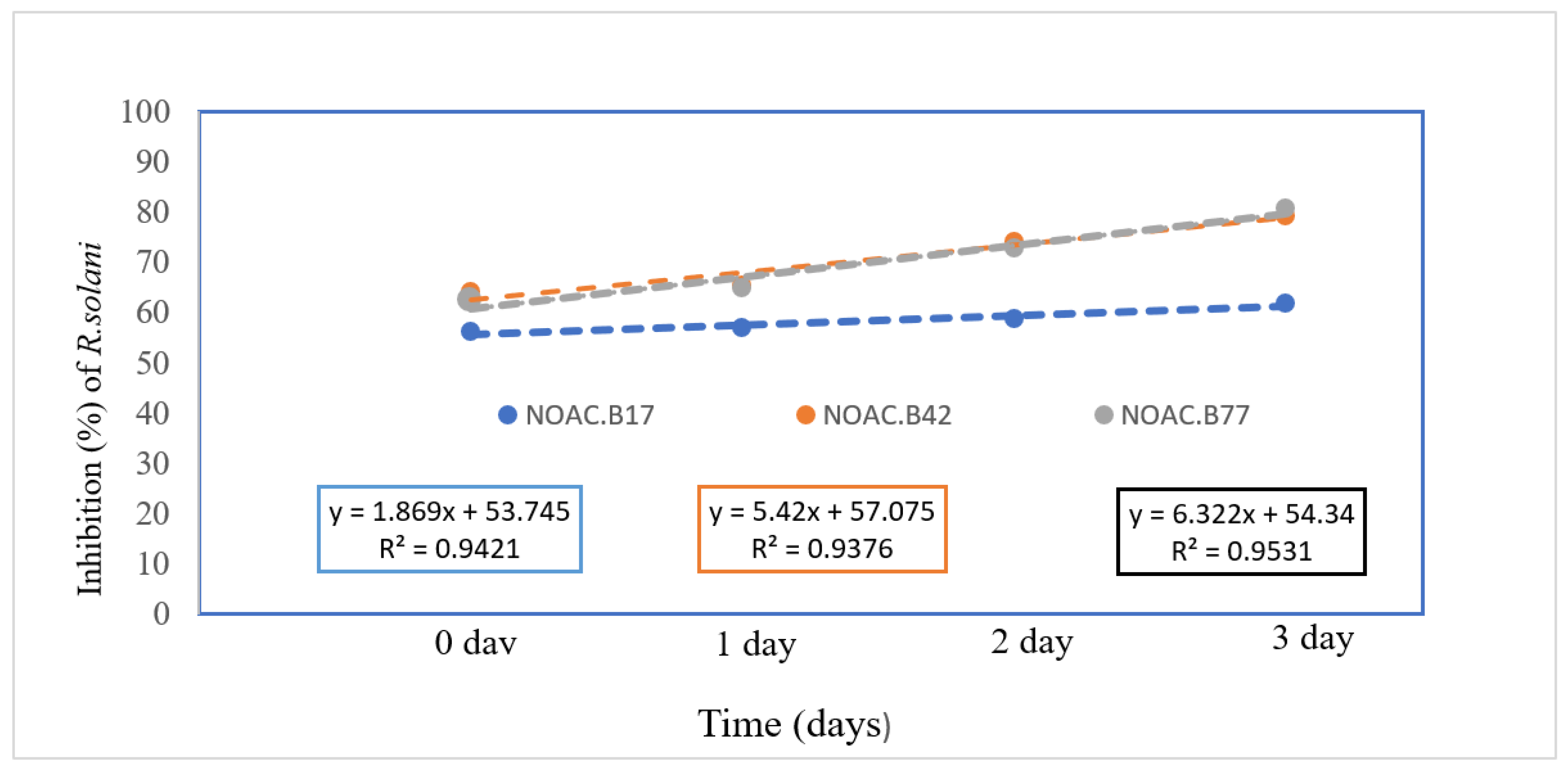

3.3. Morphological Changes in the Mycelium of R. solani Due to the Antagonistic Effect of Bacterial Isolates

Observation of the mycelium of

R. solani in the inhibition zone of culture assay plates using light microscopy revealed significant damage to hyphal structures caused by the antifungal compounds released by the bacterial isolates (

Figure 3). Common observations included shrivelling, twisting, and distortion of the hyphae of

R. solani when the fungus was co-cultivated with these bacteria. Conversely, the hyphae of

R. solani in the Control cultures appeared healthy, with a branched, tubular structure and a smooth surface.

3.4. Plant Growth Promotion by the Three Bacterial Strains and Their Ability to Colonize Tomato Roots

No significant (p < 0.05) differences were measured in the seed germination percentage, shoot length or root length of seedlings, comparing the Control and rhizobacteria-treated tomato seedlings in a rolled paper towel assay (

Table 2).

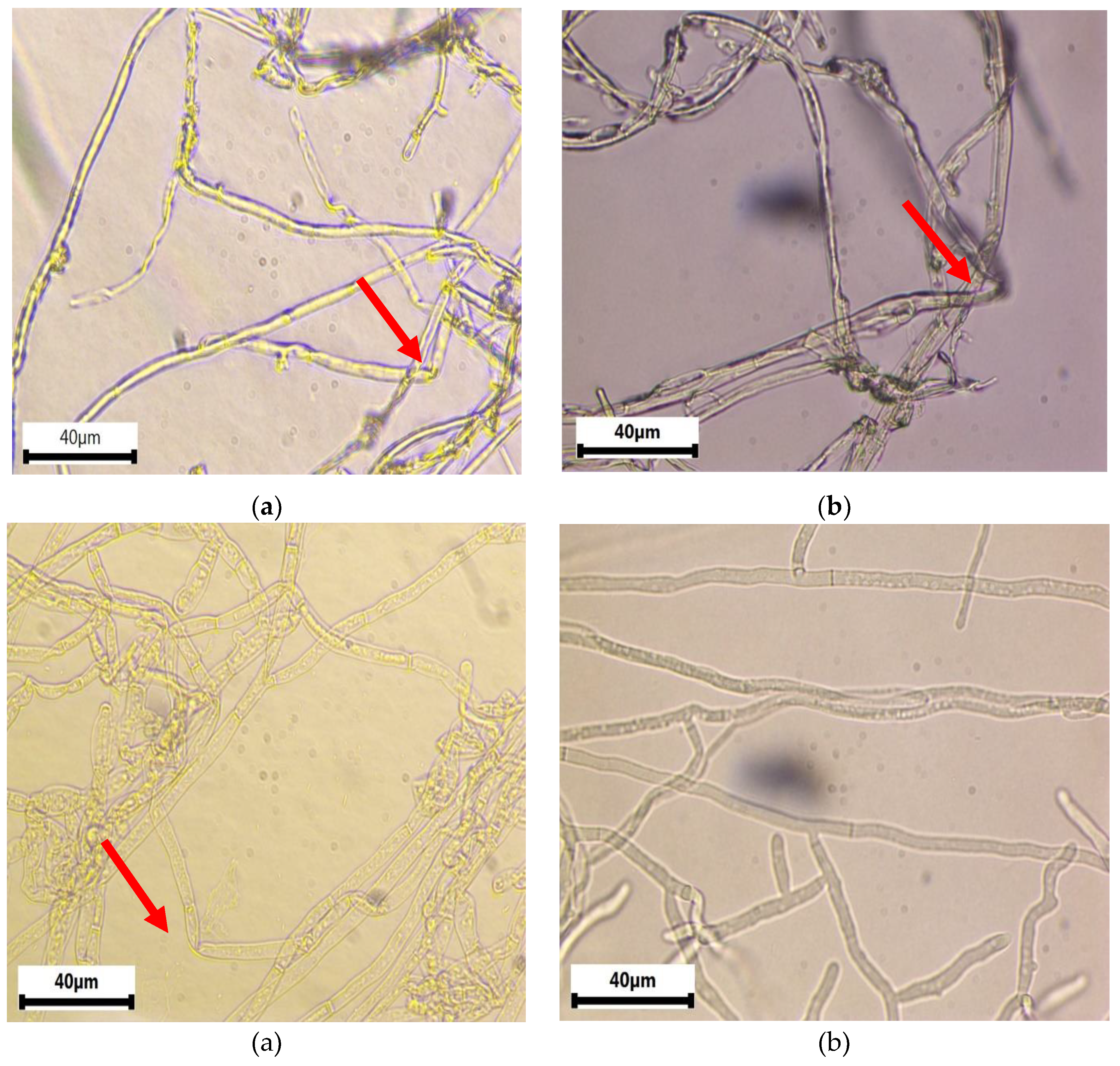

3.6. Root Colonization

The formation and development of colonies following the sterile transfer of cutting roots onto Nutrient Agar (NA) medium revealed that the tested strains colonized the roots of tomato seedlings (

Figure 4). The root fragments were sterilized in sodium hypochlorite before being cultured. This process would have killed active cells of Bacillus. Hence, it is speculated that endospores of the three Bacillus strains were present on the root samples. These endospores would have germinated and multiplied in culture. In practice, the colonisation of roots is a well-established phenomenon exhibited by Bacillus species [

30], including many biocontrol strains [

31,

32].

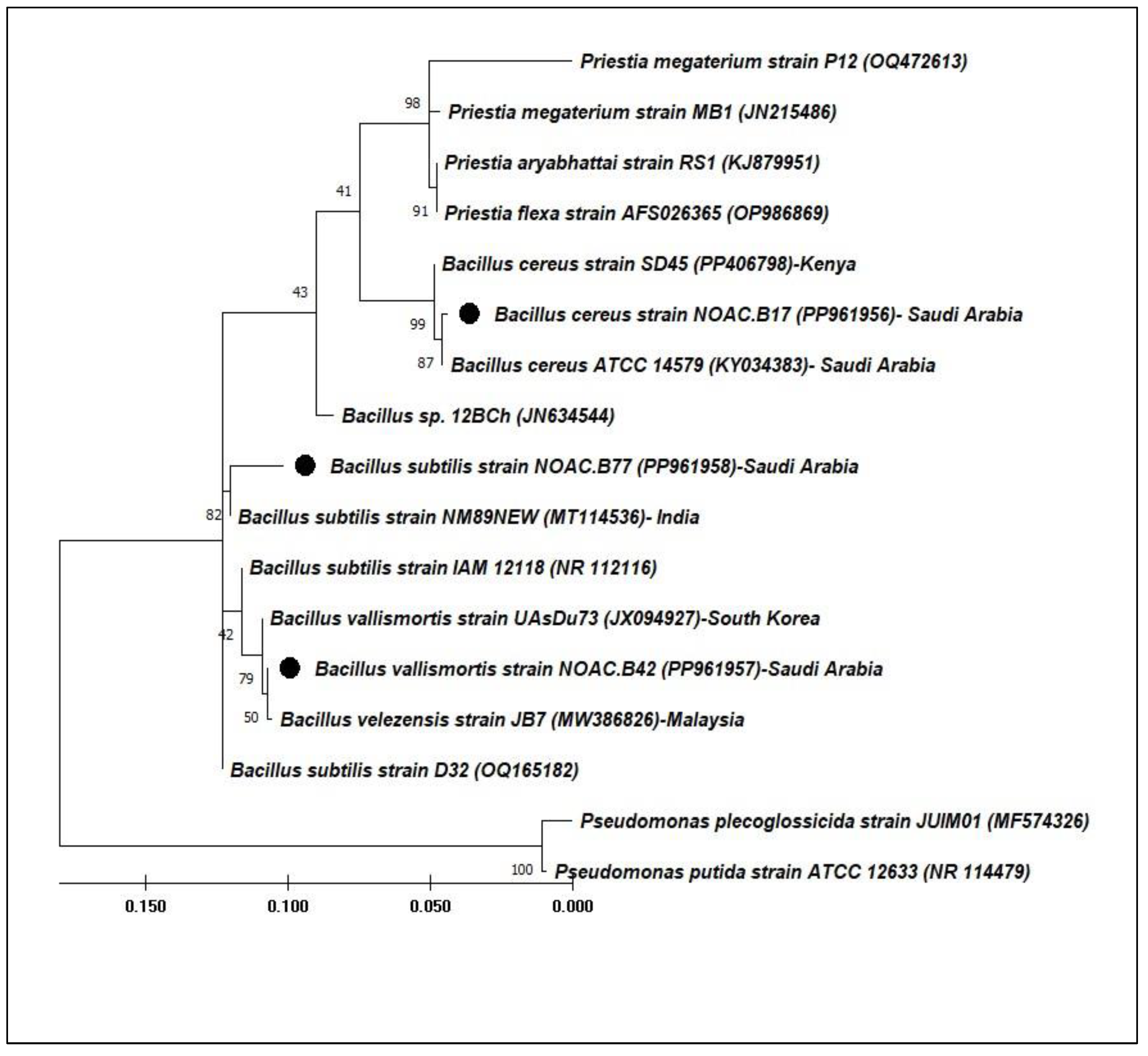

3.7. Identification of Three Selected Bacterial Isolates

The sequences generated from 16S rRNA were blasted and aligned with identified sequences in GenBank. The phylogenetic analysis of the selected isolates and their closely related counterparts is presented to illustrate their phylogenetic relationships (

Figure 5.). Bacillus cereus Strain NOAC.B17 (PP961956) demonstrated a similarity of 99.75% to Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 (KY034383) from Saudi Arabia, while

Bacillus vallismortis Strain NOAC.B42 (PP961957) displayed a relatedness of 99.82% to

Bacillus velezensis Strain JB7 from Malaysia.

Bacillus subtilis strain NOAC.B77 (PP961958) exhibited a similarity of 98.00% with

Bacillus subtilis Strain NM89NEW from India.

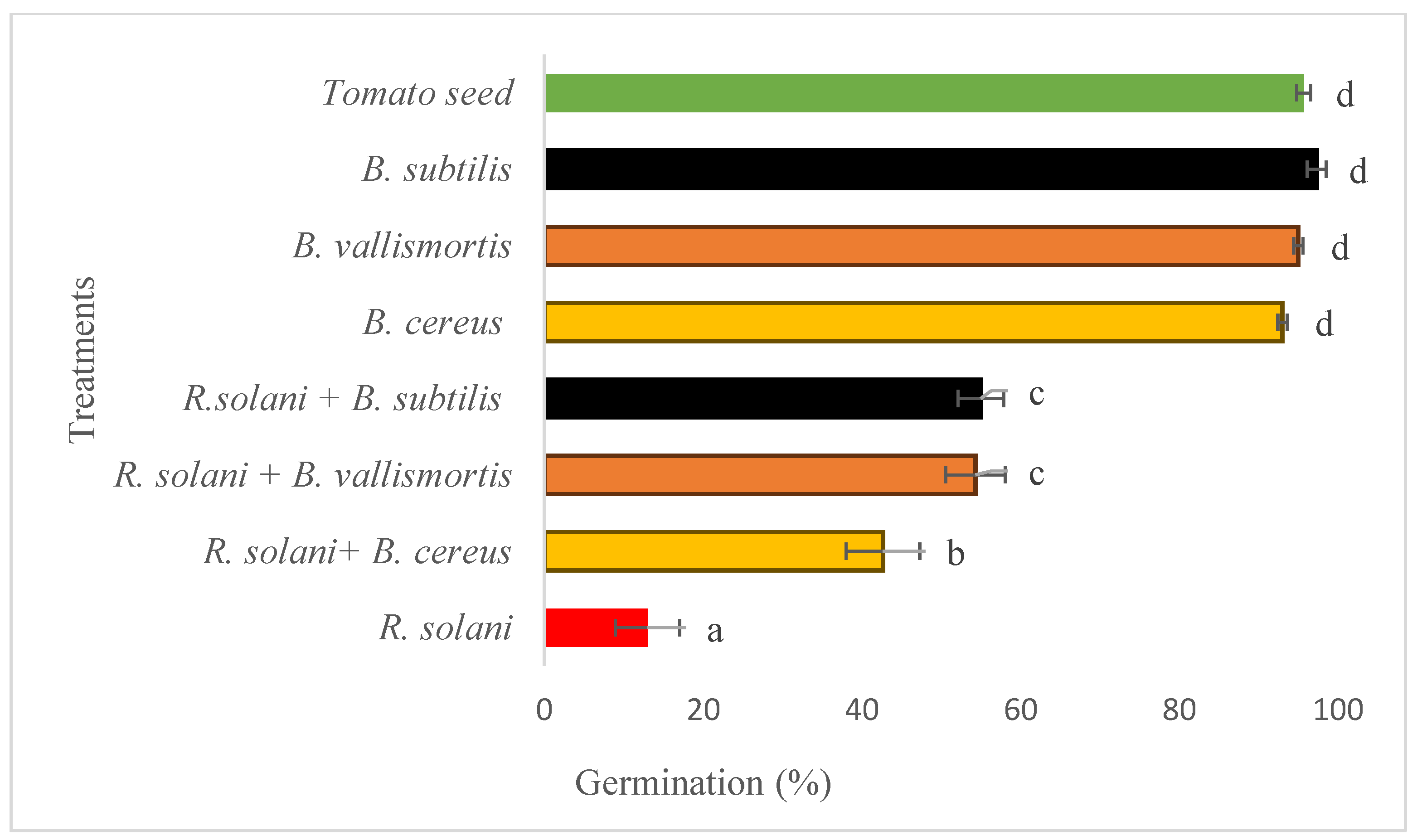

3.7. Greenhouse Experiment

Significant differences were observed (F 111.17; P<0.001; d.f. = 7) between the treatments applied to investigate the effect of the bacterial strains on

R. solani damping off of tomato seeds under greenhouse conditions. No effects were observed on tomato seeds when treated with any of the tested bacterial strains alone, and the germination percentage was similar to that of the Control treatment (>92%). The level of successful germination of the Control treatment was 13%, where the tomato seeds were inoculated with

R. solani. However, B. subtilis Strain NOAC.B77,

B. vallismortis Strain NOAC.B42 and B. cereus Strain BOAC.B17 reduced the level of

R. solani damping off by 55.0%, 54.3% and 47.7%, respectively. (

Figure 6.).

4. Discussion

Biological control is a good option for managing soil-borne vegetable crop diseases, including those caused by

R. solani, due to its environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and user-friendly attributes. Many commercial biopesticide products are available worldwide for large-scale field application [

33]. However, the successful biocontrol of soil pathogens relies on the competitiveness of the microbial biocontrol agents in the soil. Therefore, the focus in this study was on identifying indigenous antagonistic bacterial strains from vermicompost, which is regarded as the most suitable and practical natural fertiliser in organic agriculture in Saudi Arabia.

Out of 85 bacterial isolates screened, three isolates (

Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77),

Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), and

Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17)) exhibited antagonistic activity against

R. solani in a dual culture in vitro assay, producing a clear zone of inhibition around the fungus. The antagonistic performance of the effective strains increased over time, from 56% on day zero and increasing to 79.2% and 80.8% on day three for

B. subtilis (NOAC.B77) and

B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42), respectively. These increases may result from the continuous release of antimicrobial compounds by the bacterial strains into the agar medium. Applying these bacteria to tomato seeds or seedlings three days before planting them should enhance their ability to control

R. solani under field conditions, by allowing the bacteria the time to multiply, spread and release antimicrobial compounds into the growing medium or soil. This would lead to a reduction in the inoculum levels of

R. solani and subsequently reduce the levels of seed and plant infections. These results align with the findings of [

34], who used

B. subtilis Strain RB14 to treat tomato seeds. Treated seeds strongly inhibited the growth of

R. solani in culture. Similarly, [

35] found that another isolate of B. subtilis, Strain SR22, inhibited the growth of

R. solani in a dual culture test by 51%. The differences in the levels of inhibition of

R. solani as a result of the different bacterial isolates in the present study can be attributed to the quantity and toxicity of the inhibitory compounds produced by these bacterial strains [

26].

The inhibitory effect of the bacterial isolates was further confirmed by examining

R. solani hyphae in the inhibition zone of dual culture plates using a light microscope.

R. solani hyphae, when co-cultivated with antagonistic bacterial strains, exhibited morphological abnormalities, including distortion, shrivelling, twisting, and irregular growth. Similar observations were reported by [

36] when

Bacillus velezensis GH1-13 was co-cultivated with

R. solani, the causal agent of a disease affecting cool-season turfgrasses. Irregular growth distortions were also reported by [

37] when

Bacillus subtilis SL-44 was co-cultivated with

R. solani on paper, specifically with Capsicum annuum (L.) The morphological changes of

R. solani mycelium caused by the tested Bacillus strains suggest that the antifungal compounds generated by these strains may play a key role in their biological control activity.

In the in vitro plant growth promotion test in this study the tested bacterial strains did not significantly increase or decrease seed germination or seedling vigour of the tomato seeds. In contrast, other studies have found that the bacterization of seeds with bacteria can suppress plant growth. For instance, [

38] reported that treating seeds with the Klebsiella oxytoca Strain D1/3 led to a reduction in both shoot and root lengths of tomato seedlings, as well as seedling vigor, when compared to the Control treatment. This study also confirmed that the three selected bacterial strains all colonized roots successfully, and the colonization appeared to be with both living cells and endospores.

In a greenhouse pot trial,

B. subtilis (NOAC.B77),

B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42) and

B. cereus (NOAC.B17) reduced damping off caused by

R. solani by 55.0%, 54.3% and 47.7%, respectively. When tomato seeds were exposed to

R. solani without a bacterial treatment, 87% of the seed were killed by

R. solani. These findings align with those of [

39], who found that the bacterization of potato tuber seeds with B. subtilis Strain V26 significantly improved plant growth and reduce the incidence of black scurf disease caused by

R. solani.

Relatively few studies have used

B. vallismortis as a biocontrol agent for

R. solani on tomato [

40]. We found that our isolate of this species was as effective as our isolate of

B. subtilis in controlling

R. solani under field conditions. In other studies, strains of

B. vallismortis controlled various diseases, including

Fusarium solani ((Mart.) Sacc.) infecting Panax ginseng (Mey), (a perennial herb with a history of use spanning over 2,000 years in China [

41], and

Fusarium oxysporum,

Fusarium moniliforme (Sheld.),

Fusarium proliferatum (Matsush.) Nirenberg ex Gerlach & Nirenberg), and

F. solani on apple (

Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh.) [

42].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, vermicompost may be a good source of antagonistic bacteria that can be utilised in the biocontrol of soilborne diseases, such as R. solani. The most effective bacterial strains from this study, B. subtilis (NOAC.B77) and B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42), demonstrated the capacity to reduce seedling damping in tomato plants caused by R. solani. These strains may have potential as commercial biocontrol agents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.S (Mohamed Baha Saeed) ; methodology M.B.S and A.M.A (Abdulaziz M. Alnasser); software, M.B.S; validation, N.I.A. (Nasser I. Alaruk), A.A.A (Abdulrahmn A. Algrwai); formal analysis, M.B.S.; investigation, All authors.; resources, S.M.A. (Sultan, M. Al-Eid) and S.A.A (Salman, A. Aloudah); data curation, M.B.S and A.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.S.; writing—review and editing, M.B.S and M.D.L (Mark D. Laing).; visualization, M.B.S and A.A.A.; supervision, M.B.S and S.M.A. (Sultan, M. Al-Eid).; project administration, S.A.A (Salman, A. Aloudah.; funding acquisition, S.A.A (Salman, A. Aloudah).

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (Saudi Arabia) and the Saudi Organic Farming Association through the Scientific Research Development Project in Organic Farming (Grant No. 23060114771).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (Saudi Arabia), the Organic Farming Administration, and the Saudi Organic Farming Association for overseeing and funding the current work through the Scientific Research Development Project in Organic Farming (Grant No. 230601147751). The authors also acknowledge the National Center for Sustainable Agriculture Research and Development (Estidama) for overseeing the research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| NaOcl |

Sodium hypochlorite |

| PDA |

Potato Dextrose Agar |

| NOAC |

National Organic Agriculture Center |

| NA |

Nutrient Agar |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| MCL |

Maximum Composite Likelihood |

| MEGA 11 |

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11 |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| CFU |

Colony Forming Unit |

| RCBD |

Randomized Complete Block Design |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| LSD |

Least Significant Difference |

| CV% |

Coefficient of Variation |

References

- Collins, E.J.; Bowyer, C.; Tsouza, A.; Chopra, M. Tomatoes: An extensive review of the associated health impacts of tomatoes and factors that can affect their cultivation. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11(2), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAOSTAT). World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, A.A.; Ghoneem, K.M.; Rashad, Y.M.; Abdulkhair, W.M.; Hafez, E.E.; Shabana, Y.M.; Baka, Z.A. Occurrence and distribution of tomato seed-borne mycoflora in Saudi Arabia and its correlation with the climatic variables. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefzi, A.; Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H.; Abdallah, R.A.B.; Ammar, N.; Medimagh-Saïdana, S.; Haouala, R.; Daami-Remadi, M. Suppressing Fusarium crown and root rot infections and enhancing the growth of tomato plants by Lycium arabicum extracts. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kanwar, P.; Jha, G. Alterations in rice chloroplast integrity, photosynthesis and metabolome associated with pathogenesis of Rhizoctonia solani. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Bist, V.; Srivastava, S.; Singh, P.C.; Trivedi, P.K.; Asif, M.H.; Chauhan, P.S.; Nautiyal, C.S. Unraveling aspects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens-mediated enhanced production of rice under biotic stress of R. solani. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, C.; Prabha, D.; Negi, Y.K.; Maheshwari, D.K.; Dheeman, S.; Gupta, M. Macrolactin A mediated biocontrol of Fusarium oxysporum and R. solani infestation on Amaranthus hypochondriacus by Bacillus subtilis BS-58. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogazy, A.M.; Abdallah, W.E.; Mohamed, H.I.; Omran, A.A. The efficacy of chemical inducers and fungicides in controlling tomato root rot disease caused by R. solani. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Shoaib, A.; Javaid, A.; Perveen, S.; Umer, M.; Arif, M.; Cheng, C. Exploration of resistance level against black scurf caused by R. solani in different cultivars of potato. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, M.H. Rhizoctonia solani and its biological control. Turk. J. Agric. Res. 2022, 9, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akber, M.A.; Fang, X. Research progress on diseases caused by the soil-borne fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani in alfalfa. Agronomy 2024, 14(7), 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intana, W.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Wonglom, P.; Sunpapao, A. Plant growth promotion and biological control against Rhizoctonia solani in Thai local rice variety “Chor Khing” using Trichoderma breve Z2-03. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wekesa, T.B.; Wekesa, V.W.; Onguso, J.M.; Kavesu, N.; Okanya, P.W. Study of pathogenicity test, antifungal activity, and secondary metabolites of Bacillus spp. from Lake Bogoria as biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani Kühn in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 6620490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehana, Z.G.; Gebremikael, M.T.; Beyene, S.; Sleutel, S.; Wesemael, W.M.L.; De Neve, S. Organic residue valorization for Ethiopian agriculture through vermicomposting with native (Eudrilus eugeniae) and exotic (Eisenia fetida and Eisenia andrei) earthworms. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2023, 116, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltan, H.; Dakhly, O.; Mahmoud, M.; Fayz, Y.F. Microbiological and genetical identification of some vermicompost beneficial associated bacteria. SVU-Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, C.; Barman, D.; Kalita, M.C.; Deka, S. A biosurfactant-producing novel bacterial strain isolated from vermicompost having multiple plant growth-promoting traits. J. Basic Microbiol. 2023, 63, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediyawa, H.; Munidasa, W. Diversity and Ecological Significance of Vermicomposting Bacteria. In Transformative Applied Research in Computing, Engineering, Science and Technology; 141; Damayanthi, D., Miruna, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kawicha, P.; Laopha, A.; Chamnansing, W.; Sopawed, W.; Wongcharone, A.; Sangdee, A. Biocontrol and plant growth-promoting properties of Streptomyces isolated from vermicompost soil. Indian Phytopathol. 2020, 73, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yan, H.; Yin, Y.; Dong, R.; Wu, C. Use of Bacillus velezensis JNS-1 from vermicompost against strawberry root rot. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1566949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmiya, K.; Aravindharajan, S.; Bhagyashree, K.; Manoj, M. Biofilm-forming capability of Bacillus and its related genera. In Applications of Bacillus and Bacillus-Derived Genera in Agriculture, Biotechnology and Beyond; 71; Mageshwaran, V., et al., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Dong, K.; Du, Q.; Wei, Q.; Wu, J.; Deng, J.; Wang, F. Biofilm-forming of Bacillus tequilensis DZY 6715 enhanced suppression of the Camellia oleifera anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum fructicola and its mechanism. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y. Optimizing surfactin yield in Bacillus velezensis BN to enhance biocontrol efficacy and rhizosphere colonization. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1551436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, P.; Yadav, R.K.; Manandhar, H.K.; Parajulee, M.N. Management of Root Rot (Rhizoctonia solani Kühn) of Common Bean Using Host Resistance and Consortia of Chemicals and Biocontrol Agents. Biology (Basel) 2025, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, T. Characterization of variability in Rhizoctonia solani by using morphological and molecular markers. J. Phytopathol. 2005, 153, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Min, C.; Yang, Y. Isolation and antimicrobial activities of actinomycetes from vermicompost. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2015, 40, 614. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Daghari, D.S.S.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Mahmooli, I.H.; Janke, R.; Velazhahan, R. Biological control efficacy of indigenous antagonistic bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of cabbage grown in biofumigated soil against Pythium aphanidermatum damping-off of cucumber. Agriculture 2023, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Baki, A.A.; Anderson, J.D. Vigor determination in soybean seed by multiple criteria. Crop Sci. 1973, 13(6), 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.E.; Meyers, P.R. Rapid identification of filamentous actinomycetes to the genus level using genus-specific 16S rRNA gene restriction fragment patterns. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard-Massicotte, R.; Tessier, L.; Lécuyer, F.; Lakshmanan, V.; Lucier, J.-F.; Garneau, D.; Caudwell, L.; Vlamakis, H.; Bais, H.P.; Beauregard, P.B. Bacillus subtilis early colonization of Arabidopsis thaliana roots involves multiple chemotaxis receptors. MBio 2016, 7, e01664-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, A.; Deravel, J.; Krier, F.; Béchet, M.; Ongena, M.; Jacques, P. Biofilm formation is determinant in tomato rhizosphere colonization by Bacillus velezensis FZB42. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, H.C.; Thomas, V.P.; Schwientek, P.; Salamzade, R.; Chien, J.-T.; Waidyarathne, P.; Kloepper, J.; De La Fuente, L. Strain-specific quantification of root colonization by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus firmus I-1582 and B. amyloliquefaciens QST713 in non-sterile soil and field conditions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Kenfaoui, J.; Esmaeel, Q.; El Hamss, H.; Belabess, Z.; Barka, E.A. Biological control of plant pathogens: A global perspective. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohora, U.; Ano, T.; Rahman, M. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani K1 by iturin A producer Bacillus subtilis RB14 seed treatment in tomato plants. Adv. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, Y.M.; Abdalla, S.A.; Sleem, M.M. Endophytic Bacillus subtilis SR22 triggers defense responses in tomato against Rhizoctonia root rot. Plants 2022, 11, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Choi, H.; Liu, H.; Han, Y.-H.; Paul, N.C.; Han, G.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, P.I.; Seo, S.-I.; Song, J. Biocontrol of the causal brown patch pathogen Rhizoctonia solani by Bacillus velezensis GH1-13 and development of a bacterial strain-specific detection method. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1091030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Dong, J.; Liu, X.; Li, C. Biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani via induction of the defense mechanism and antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacillus subtilis SL-44 on pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussini, H.S.; Al-Rawahi, A.Y.; Al-Marhoon, A.A.; Al-Abri, S.A.; Al-Mahmooli, I.H.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Velazhahan, R. Biological control of damping-off of tomato caused by Pythium aphanidermatum by using native antagonistic rhizobacteria isolated from Omani soil. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 101, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedher, S.B.; Kilani-Feki, O.; Dammak, M.; Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H.; Daami-Remadi, M.; Tounsi, S. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis V26 as a biological control agent against Rhizoctonia solani on potato. C. R. Biol. 2015, 338, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotar, V.K.; Gancheva, M.S.; Chizhevskaya, E.P.; Erofeeva, A.V.; Khiutti, A.V.; Lazarev, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Xue, J.; Yang, C.; Tikhonovich, I.A. Endophyte Bacillus vallismortis BL01 to control fungal and bacterial phytopathogens of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, L.-Y.; Lei, M.-Y.; Yang, Y.-X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, W.; Han, Z.-M.; Cheng, L.; Lv, Z.-L.; Han, M. Bacillus vallismortis acts against ginseng root rot by modifying the composition and microecological functions of ginseng root endophytes. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1561057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X.; Yin, C.; Mao, Z. Isolation and identification of Bacillus vallismortis HSB-2 and its biocontrol potential against apple replant disease. Biol. Control 2022, 170, 104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

In vitro antagonistic activity of three bacterial isolates against Rhizoctonia solani in a dual culture assay, after three days of bacterial incubation: (A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), (B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), (C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and (D) R. solani only, Untreated Control.

Figure 1.

In vitro antagonistic activity of three bacterial isolates against Rhizoctonia solani in a dual culture assay, after three days of bacterial incubation: (A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), (B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), (C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and (D) R. solani only, Untreated Control.

Figure 2.

Linear regression analysis showed the relationship between inhibition percentage of R. solani mycelial growth and increasing time of bacterial inoculum following application of three bacterial isolates Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42) and Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17).

Figure 2.

Linear regression analysis showed the relationship between inhibition percentage of R. solani mycelial growth and increasing time of bacterial inoculum following application of three bacterial isolates Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42) and Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17).

Figure 3.

Light microscope images of Rhizoctonia solani hyphae in the inhibition zone of the dual culture assay, showing morphological abnormalities. A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and D) R. solani only, Untreated Control.

Figure 3.

Light microscope images of Rhizoctonia solani hyphae in the inhibition zone of the dual culture assay, showing morphological abnormalities. A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and D) R. solani only, Untreated Control.

Figure 4.

A test for root colonisation of tomato seedling roots by three Bacillus strains reveals colonies, following the aseptic transfer of root samples onto NA medium: A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and D) Untreated seed (Control).

Figure 4.

A test for root colonisation of tomato seedling roots by three Bacillus strains reveals colonies, following the aseptic transfer of root samples onto NA medium: A) Bacillus subtilis (NOAC.B77), B) Bacillus vallismortis (NOAC.B42), C) Bacillus cereus (NOAC.B17), and D) Untreated seed (Control).

Figure 5.

A molecular phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA of the three selected bacteria. The tree is divided into two groups: the first group involves all identified strains and their relatives, while Pseudomonas bacteria are found in the second group.

Figure 5.

A molecular phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA of the three selected bacteria. The tree is divided into two groups: the first group involves all identified strains and their relatives, while Pseudomonas bacteria are found in the second group.

Figure 6.

Effect of three bacterial isolates: Bacillus subtilis Strain NOAC.B77, Bacillus vallismortis Strain NOAC.B42 and Bacillus cereus Strain NOAC.B17 on seedling damping off caused by R. solani of tomato seedlings grown under greenhouse conditions. The error bars represent the SE.

Figure 6.

Effect of three bacterial isolates: Bacillus subtilis Strain NOAC.B77, Bacillus vallismortis Strain NOAC.B42 and Bacillus cereus Strain NOAC.B17 on seedling damping off caused by R. solani of tomato seedlings grown under greenhouse conditions. The error bars represent the SE.

Table 1.

In vitro mycelial growth inhibition of R. solani following exposure to three Bacillus isolates at 0.0, 1, 2, and 3 days from the addition of bacterial inoculum.

Table 1.

In vitro mycelial growth inhibition of R. solani following exposure to three Bacillus isolates at 0.0, 1, 2, and 3 days from the addition of bacterial inoculum.

| Isolate |

Inhibition (%) in R. solani |

| Time after bacterial inoculation (days) |

| (0) day |

(1) day |

(2) days |

(3) days |

|

B. subtilis (NOAC.B77) |

62.38 b |

64.70 b |

72.72 b |

80.77 b |

|

B. vallismortis (NOAC.B42) |

64 b |

65.30 b |

74.05 b |

79.15 b |

|

B. cereus (NOAC.B17) |

56.12 a |

57.0 a |

58.8 a |

61.75 a |

| LSD |

4.329 |

6.39 |

6.03 |

4.025 |

| P value |

0.015 |

0.034 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| F Value |

9.14 |

6.28 |

30.81 |

82.21 |

| CV% |

4.5 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

3.1 |

Table 2.

Efficacy of seed treatment with antagonistic bacterial strains on seed germination and seedling vigor of tomato under laboratory conditions.

Table 2.

Efficacy of seed treatment with antagonistic bacterial strains on seed germination and seedling vigor of tomato under laboratory conditions.

| Strain |

Germination (%) |

Root Length (cm) |

Shoot Length (cm) |

Vigor Index |

|

B. subtilis (NOAC. B77) |

96.80 a |

3.340 a |

0.64 a |

385.7 a |

|

B. vallismortis (NOAC. B42) |

96.80 a |

3.540 a |

0.80 a |

384.2 a |

|

B. cereus (NOAC. B17) |

94.20 a |

3.680 a |

0.40 a |

382.5 a |

| Control |

95.20 a |

3.600 a |

0.18 a |

352.2 a |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).