Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolates

2.2. Identification of Metarhizium Isolates

2.3. Bacteria-free Metarhizium

2.4. Endobacteria Isolation

2.5. Identification of bacterial Isolates

2.6. Bacterial DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.7. Comparative genomic Analysis

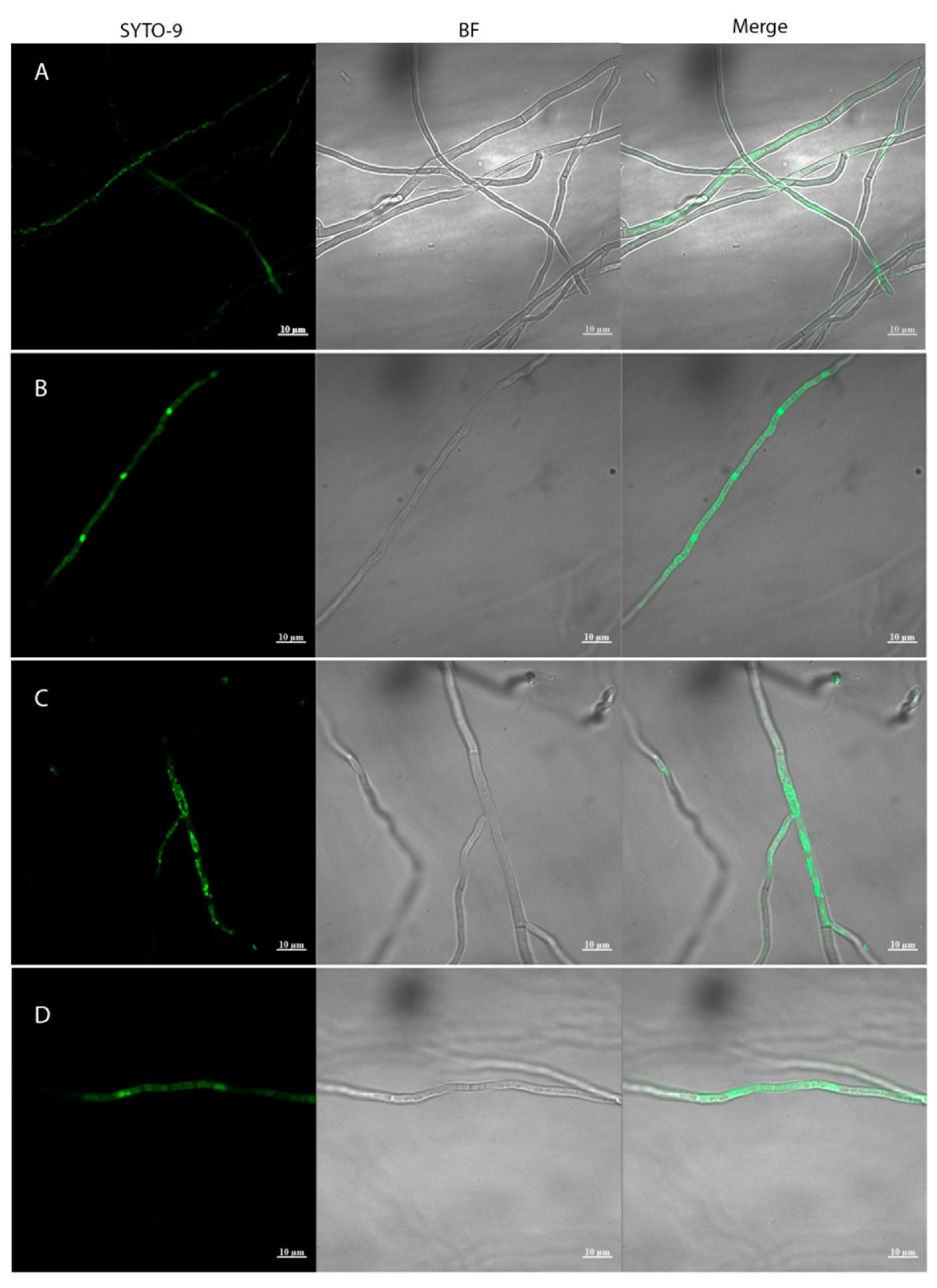

2.8. Localization of Endobacteria Using Microscopy

2.9. Conidial Yield

2.10. Conidia Germination Assay

2.11. Insect bioassays

2.12. Phylogenetic analyses

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Associated endobacteria Can Be Identified in Native Metarhizium Strains

3.2. Metarhizium Endobacteria Isolation and Identification

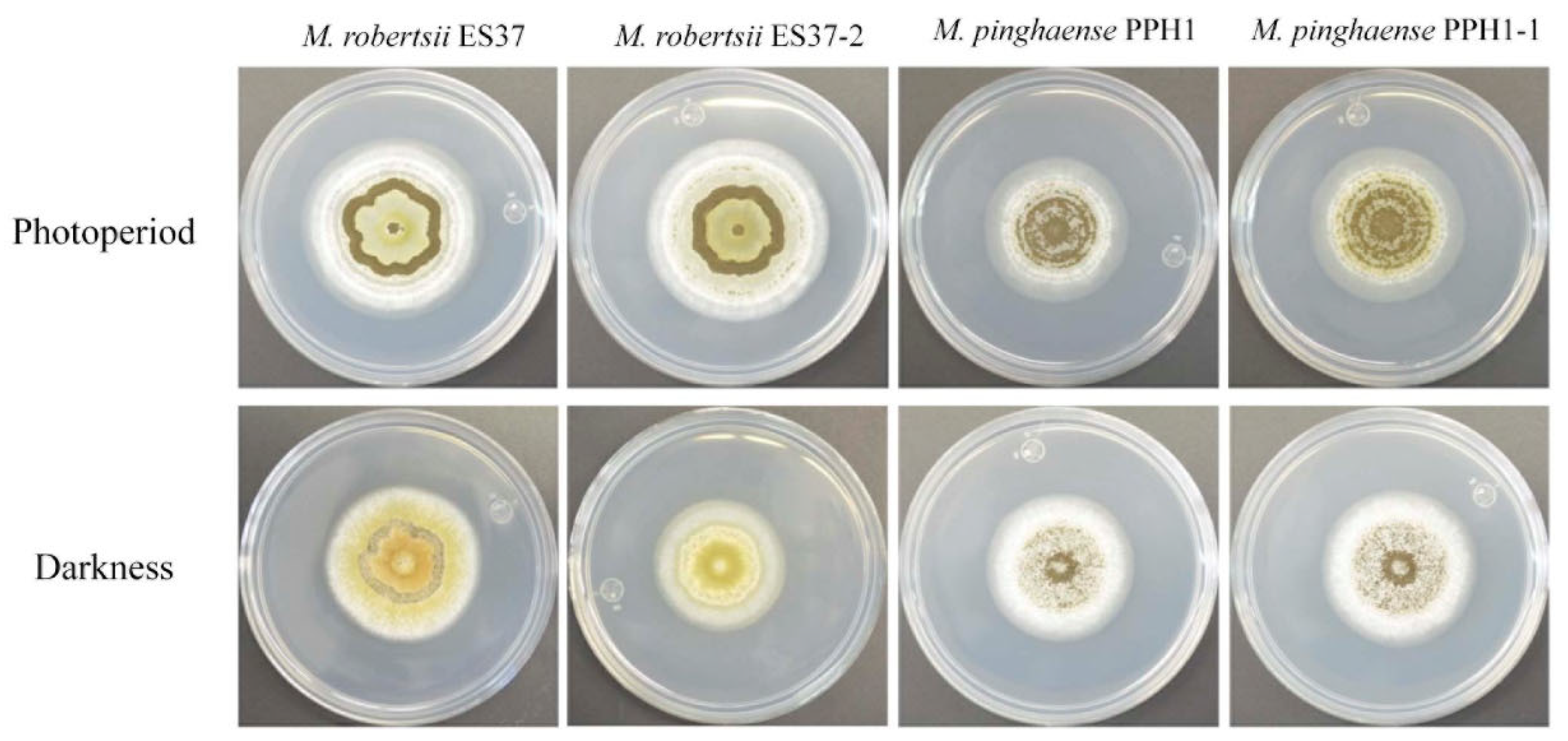

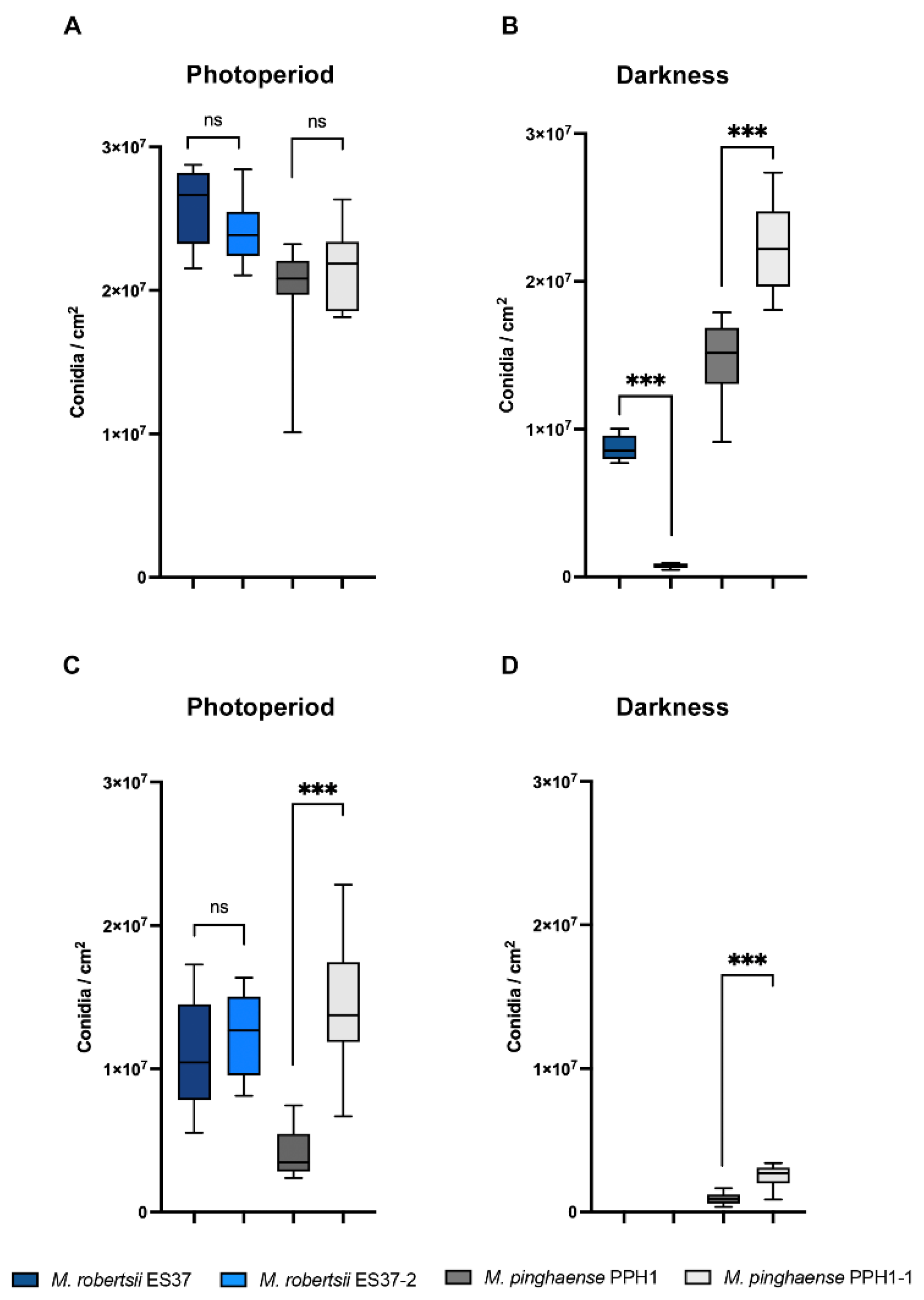

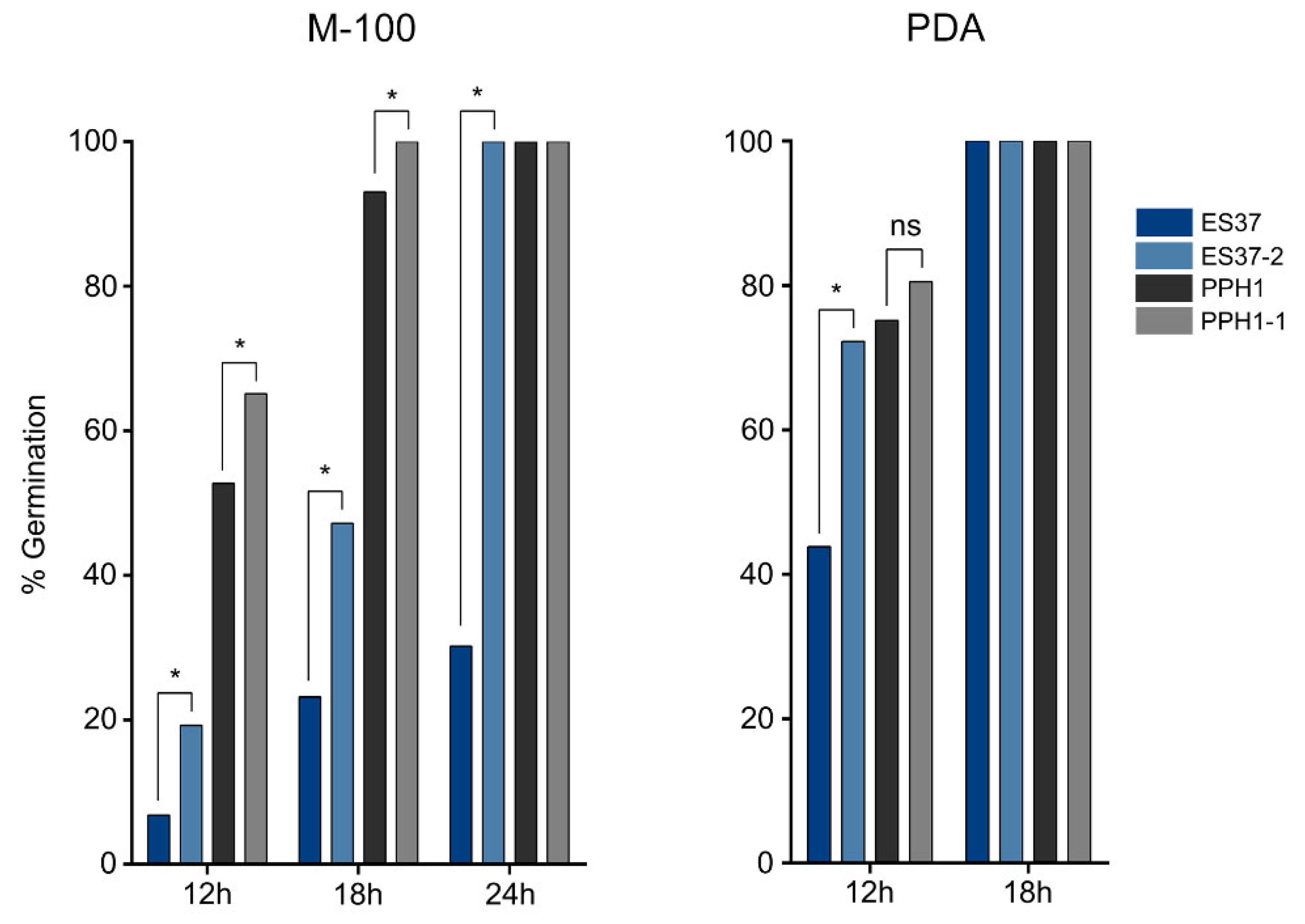

3.3. Endobacteria's Impact on Metarhizium Conidiation

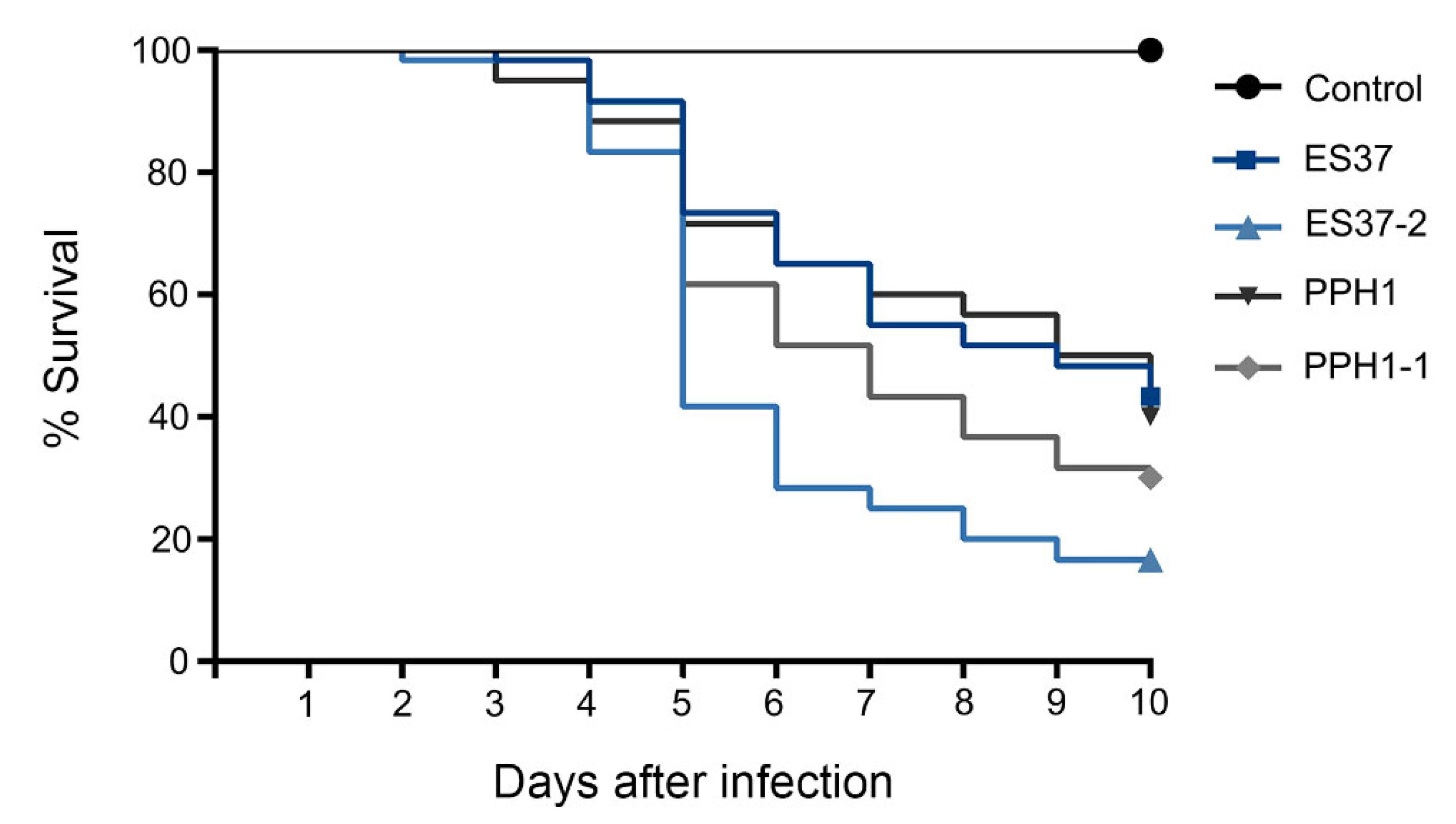

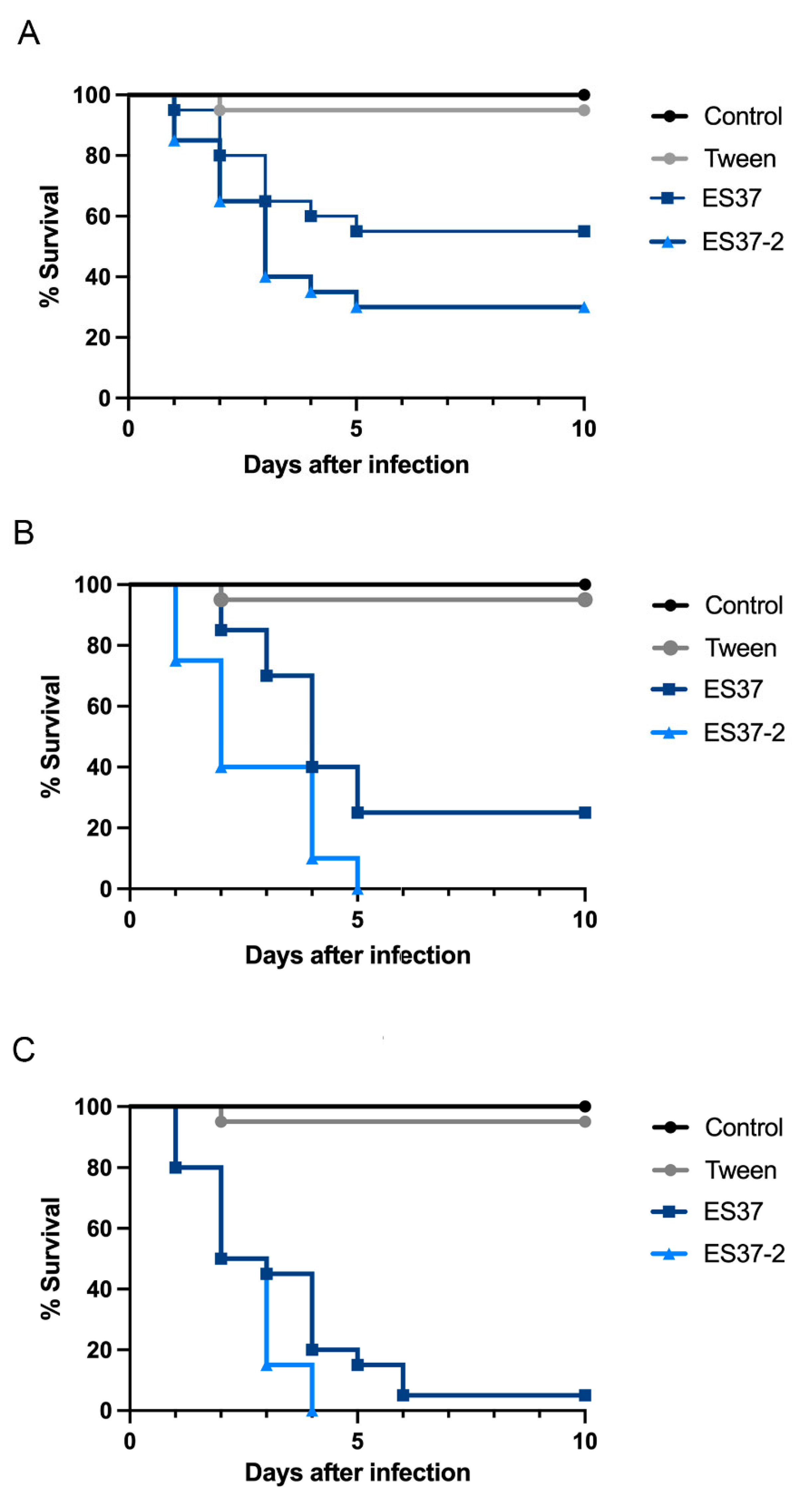

3.4. Associated Endobacteria Affected Metarhizium Virulence

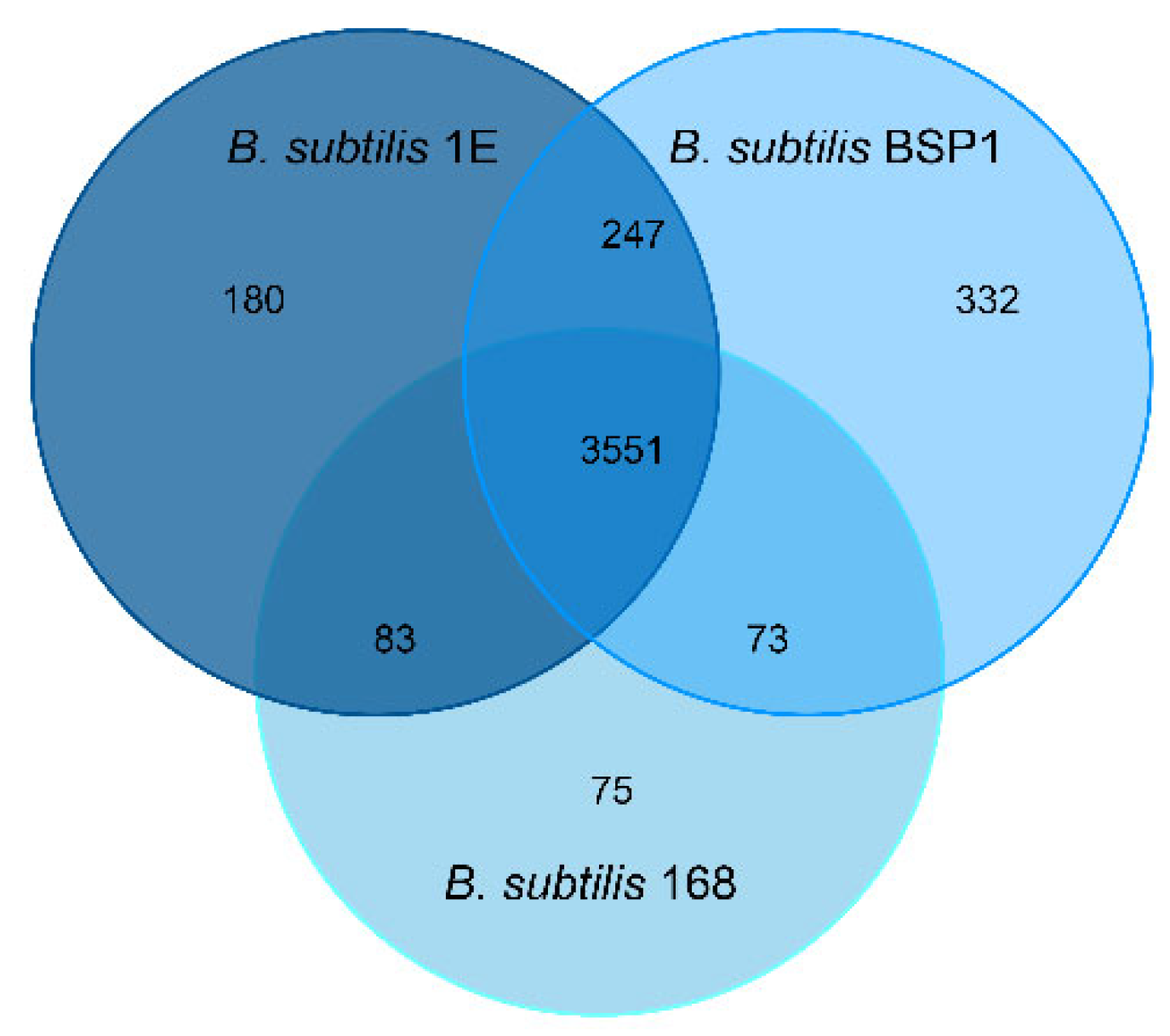

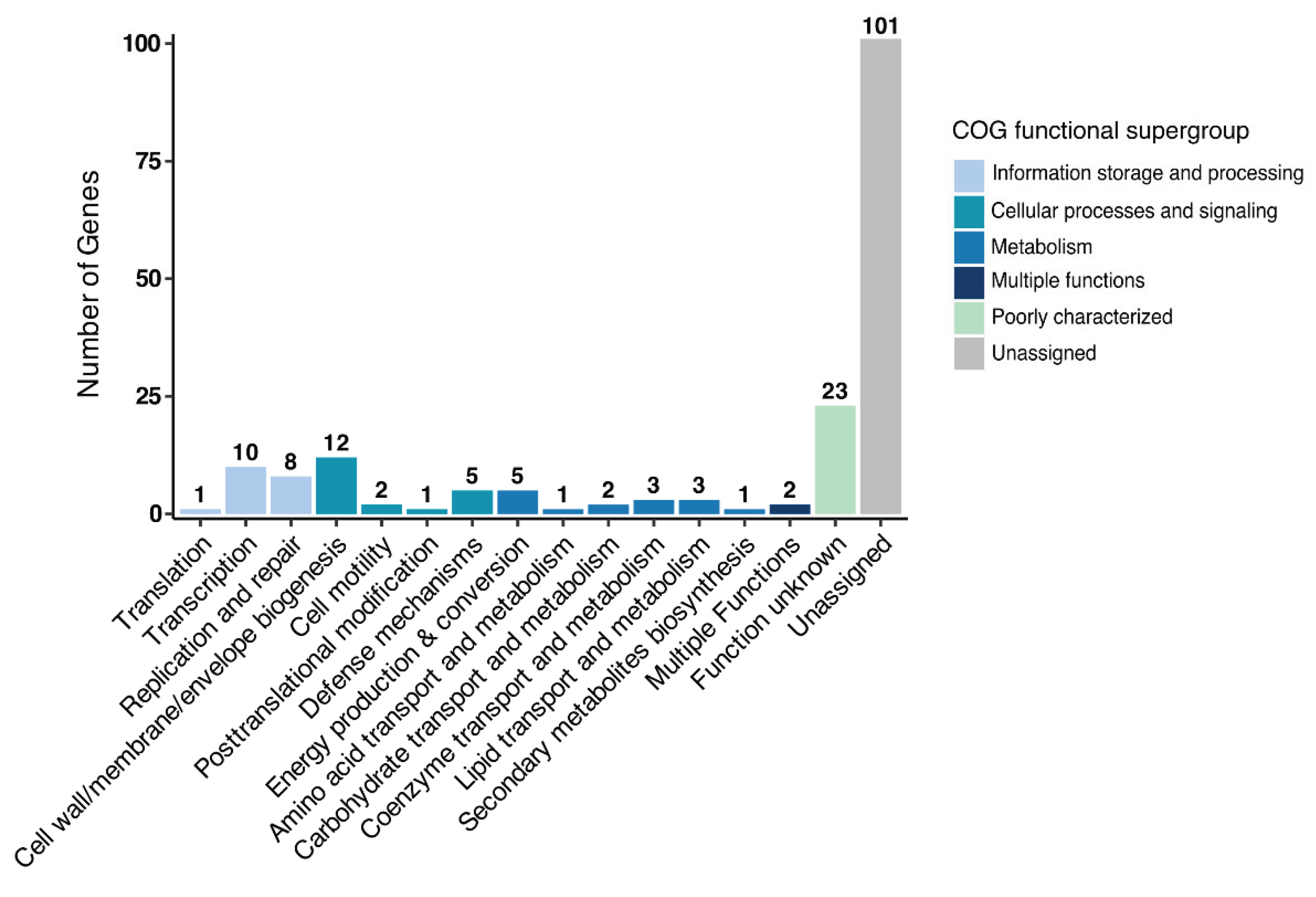

3.5. Genomic Analysis of Associated Endobacteria

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EHB | Endofungal bacteria |

References

- Moya, A.; Peretó, J.; Gil, R.; Latorre, A. Learning how to live together: genomic insights into prokaryote–animal symbioses. Nature Reviews Genetics 2008, 9, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araldi-Brondolo, S.J.; Spraker, J.; Shaffer, J.P.; Woytenko, E.H.; Baltrus, D.A.; Gallery, R.E.; Arnold, A.E. Bacterial Endosymbionts: Master Modulators of Fungal Phenotypes. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosse, B. Honey-coloured, sessile Endogone spores: II. Changes in fine structure during spore development. Archiv für Mikrobiologie 1970, 74, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, J.M.; Robinson, A.J.; Longley, R.; Johnson, L.Y.D.; Hanson, B.T.; Morales, D.P.; Cailleau, G.; Junier, P.; Bonito, G.; Chain, P.S.G. The endohyphal microbiome: current progress and challenges for scaling down integrative multi-omic microbiome research. Microbiome 2023, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabid, I.; Glaeser, S.; Kogel, K.-H. Endofungal Bacteria Increase Fitness of their Host Fungi and Impact their Association with Crop Plants. Current issues in molecular biology 2018, 30, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Martínez, L.P. The fungal holobiont: Evidence from early diverging fungi. Environ Microbiol 2017, 19, 2919–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J.; House, G.L.; Morales, D.P.; Kelliher, J.M.; Gallegos-Graves, L.V.; LeBrun, E.S.; Davenport, K.W.; Palmieri, F.; Lohberger, A.; Bregnard, D.; et al. Widespread bacterial diversity within the bacteriome of fungi. Communications Biology 2021, 4, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianciotto, V.; Bandi, C.; Minerdi, D.; Sironi, M.; Tichy, H.V.; Bonfante, P. An obligately endosymbiotic mycorrhizal fungus itself harbors obligately intracellular bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996, 62, 3005–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerdi, D.; Fani, R.; Gallo, R.; Boarino, A.; Bonfante, P. Nitrogen Fixation Genes in an Endosymbiotic<i>Burkholderia</i> Strain. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2001, 67, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partida-Martinez, L.P.; Hertweck, C. Pathogenic fungus harbours endosymbiotic bacteria for toxin production. Nature 2005, 437, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itabangi, H.; Sephton-Clark, P.C.S.; Tamayo, D.P.; Zhou, X.; Starling, G.P.; Mahamoud, Z.; Insua, I.; Probert, M.; Correia, J.; Moynihan, P.J.; et al. A bacterial endosymbiont of the fungus Rhizopus microsporus drives phagocyte evasion and opportunistic virulence. Curr Biol 2022, 32, 1115–1130.e1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Martinez, L.P.; Groth, I.; Schmitt, I.; Richter, W.; Roth, M.; Hertweck, C. Burkholderia rhizoxinica sp. nov. and Burkholderia endofungorum sp. nov., bacterial endosymbionts of the plant-pathogenic fungus Rhizopus microsporus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2007, 57, 2583–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawana, A.; Adeolu, M.; Gupta, R.S. Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov. harboring environmental species. Front Genet 2014, 5, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partida-Martínez, L.P. Fungal holobionts as blueprints for synthetic endosymbiotic systems. PLoS biology 2024, 22, e3002587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Herrera, J.; León-Ramírez, C.; Vera-Nuñez, A.; Sánchez-Arreguín, A.; Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Salgado-Lugo, H.; Sánchez-Segura, L.; Peña-Cabriales, J.J. A novel intracellular nitrogen-fixing symbiosis made by Ustilago maydis and Bacillus spp. New Phytologist 2015, 207, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; González-Prieto, J.M.; Vera-Núñez, J.A.; Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Peña-Cabriales, J.J.; Ruiz-Herrera, J. Wide distribution of the Ustilago maydis-bacterium endosymbiosis in naturally infected maize plants. Plant Signal Behav 2021, 16, 1855016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behie, S.W.; Padilla-Guerrero, I.E.; Bidochka, M.J. Nutrient transfer to plants by phylogenetically diverse fungi suggests convergent evolutionary strategies in rhizospheric symbionts. Commun Integr Biol 2013, 6, e22321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R.; Lomer, C.; Prior, C. Biological control of locusts and grasshoppers. 1992.

- Nishi, O.; Sato, H. Isolation of Metarhizium spp. from rhizosphere soils of wild plants reflects fungal diversity in soil but not plant specificity. Mycology 2019, 10, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.W.; St Leger, R.J. Metarhizium spp., cosmopolitan insect-pathogenic fungi: mycological aspects. Adv Appl Microbiol 2004, 54, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G. Review on safety of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Beauveria brongniartii. Biocontrol Science and Technology 2007, 17, 553–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.B.L.; Bidochka, M.J. The multifunctional lifestyles of Metarhizium: evolution and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 9935–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behie, S.W.; Zelisko, P.M.; Bidochka, M.J. Endophytic insect-parasitic fungi translocate nitrogen directly from insects to plants. Science 2012, 336, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behie, S.W.; Bidochka, M.J. Ubiquity of insect-derived nitrogen transfer to plants by endophytic insect-pathogenic fungi: an additional branch of the soil nitrogen cycle. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behie, S.W.; Moreira, C.C.; Sementchoukova, I.; Barelli, L.; Zelisko, P.M.; Bidochka, M.J. Carbon translocation from a plant to an insect-pathogenic endophytic fungus. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Elena; Posadas, J. ; Perticari, A.; Alejandro, L.; Roberto, E. Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschnikoff) Sorokin Promotes Growth and Has Endophytic Activity in Tomato Plants. Advances in Biological Research 2011, 5, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, X.; O'Brien, T.R.; Fang, W.; St Leger, R.J. The plant beneficial effects of Metarhizium species correlate with their association with roots. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 7089–7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pérez, E.; Ortega-Amaro, M.A.; Bautista, E.; Delgado-Sánchez, P.; Jiménez-Bremont, J.F. The entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae enhances Arabidopsis, tomato, and maize plant growth. Plant Physiol Biochem 2022, 176, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, B. Entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae play roles of maize (Zea mays) growth promoter. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Hamayun, M.; Khan, S.A.; Kang, S.M.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Kamran, M.; Ur Rehman, S.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, I.J. Pure culture of Metarhizium anisopliae LHL07 reprograms soybean to higher growth and mitigates salt stress. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 28, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.Z.H.; Mostofa, M.G.; Mim, M.F.; Haque, M.A.; Karim, M.A.; Sultana, R.; Rohman, M.M.; Bhuiyan, A.U.; Rupok, M.R.B.; Islam, S.M.N. The fungal endophyte Metarhizium anisopliae (MetA1) coordinates salt tolerance mechanisms of rice to enhance growth and yield. Plant Physiol Biochem 2024, 207, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canassa, F.; Esteca, F.C.N.; Moral, R.A.; Meyling, N.V.; Klingen, I.; Delalibera, I. Root inoculation of strawberry with the entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium robertsii and Beauveria bassiana reduces incidence of the twospotted spider mite and selected insect pests and plant diseases in the field. Journal of Pest Science 2020, 93, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasan, R.; Bidochka, M. Antagonism of the endophytic insect pathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii against the bean plant pathogen Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2013, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachapa, J.C.; Meyling, N.V.; Burow, M.; Hauser, T.P. Induction and Priming of Plant Defense by Root-Associated Insect-Pathogenic Fungi. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2021, 47, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Keppanan, R.; Leibman-Markus, M.; Rav-David, D.; Elad, Y.; Ment, D.; Bar, M. The Entomopathogenic Fungi Metarhizium brunneum and Beauveria bassiana Promote Systemic Immunity and Confer Resistance to a Broad Range of Pests and Pathogens in Tomato. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Leger, R.J.; Wang, J.B. Metarhizium: jack of all trades, master of many. Open Biol 2020, 10, 200307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Leger, R. The evolution of complex Metarhizium-insect-plant interactions. Fungal Biology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Liu, C.; He, R.; Wang, R.; Qu, L. Detection and Identification of Novel Intracellular Bacteria Hosted in Strains CBS 648.67 and CFCC 80795 of Biocontrol Fungi Metarhizium. Microbes Environ 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, J.F.; Rehner, S.A.; Humber, R.A. A multilocus phylogeny of the Metarhizium anisopliae lineage. Mycologia 2009, 101, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W.; Irwin, C.A.; Janssen, K.A. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 2001.

- Fredriksson, N.J.; Hermansson, M.; Wilén, B.M. The choice of PCR primers has great impact on assessments of bacterial community diversity and dynamics in a wastewater treatment plant. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautreau, G.; Bazin, A.; Gachet, M.; Planel, R.; Burlot, L.; Dubois, M.; Perrin, A.; Médigue, C.; Calteau, A.; Cruveiller, S.; et al. PPanGGOLiN: Depicting microbial diversity via a partitioned pangenome graph. PLoS Comput Biol 2020, 16, e1007732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vargas, C.; Linares-López, C.; López-Torres, A.; Wrobel, K.; Torres-Guzmán, J.C.; Hernández, G.A.; Lanz-Mendoza, H.; Contreras-Garduño, J. Methylation on RNA: A Potential Mechanism Related to Immune Priming within But Not across Generations. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, G.; Serra, C.R.; Lapointe, T.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Potot, S.; Fickers, P.; Perkins, J.B.; Wyss, M.; Henriques, A.O. Genome of a Gut Strain of Bacillus subtilis. Genome Announc 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.L.; Stoyanov, J.V.; Kidd, S.P.; Hobman, J.L. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2003, 27, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulin, G.; Figueroa, N.R.; Checa, S.K.; Soncini, F.C. The multifarious MerR family of transcriptional regulators. Mol Microbiol 2024, 121, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Li, C.; Xie, J. The underling mechanism of bacterial TetR/AcrR family transcriptional repressors. Cell Signal 2013, 25, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Meredith, T.; Swoboda, J.; Walker, S. Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis W23 make polyribitol wall teichoic acids using different enzymatic pathways. Chem Biol 2010, 17, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Santa Maria, J.P., Jr.; Walker, S. Wall teichoic acids of gram-positive bacteria. Annual review of microbiology 2013, 67, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, G.; Fogel, G.B.; Abramson, B.; Brinkac, L.; Michael, T.; Liu, E.S.; Thomas, S. Horizontal transfer and evolution of wall teichoic acid gene cassettes in Bacillus subtilis. F1000Res 2021, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aunpad, R.; Panbangred, W. Evidence for two putative holin-like peptides encoding genes of Bacillus pumilus strain WAPB4. Curr Microbiol 2012, 64, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frąc, M.; Hannula, S.E.; Bełka, M.; Jędryczka, M. Fungal Biodiversity and Their Role in Soil Health. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares-Rodriguez, F.d.J.; Aréchiga-Carvajal, E.T.; Ruiz-Herrera Ŧ, J.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; González-Herrera, S.M.; León-Ramírez, C.G.; Martínez-Roldán, A.d.J.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, O.M. A new bacterial endosymbiotic relationship in Kluyveromyces marxianus isolated from the mezcal fermentation process. Process Biochemistry 2023, 131, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alonzo, K.; Silva-Mieres, F.; Arellano-Arriagada, L.; Parra-Sepúlveda, C.; Bernasconi, H.; Smith, C.T.; Campos, V.L.; García-Cancino, A. Nutrient Deficiency Promotes the Entry of Helicobacter pylori Cells into Candida Yeast Cells. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakolian, A.; Heydari, S.; Siavoshi, F.; Brojeni, G.N.; Sarrafnejad, A.; Eftekhar, F.; Khormali, M. Localization of Staphylococcus inside the vacuole of Candida albicans by immunodetection and FISH. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 75, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska, T.E.; Gaspar, M.L.; Lastovetsky, O.A.; Mondo, S.J.; Real-Ramirez, I.; Shakya, E.; Bonfante, P. Biology of Fungi and Their Bacterial Endosymbionts. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2018, 56, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, P.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S. Endohyphal bacteria; the prokaryotic modulators of host fungal biology. Fungal Biology Reviews 2019, 33, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, S.; Peña-Bahamonde, J.; Bonito, G.; Rodrigues, D.F. Effect of Endosymbiotic Bacteria on Fungal Resistance Toward Heavy Metals. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 822541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partida-Martinez, L.P.; Monajembashi, S.; Greulich, K.O.; Hertweck, C. Endosymbiont-dependent host reproduction maintains bacterial-fungal mutualism. Curr Biol 2007, 17, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.T.; Gunatilaka, M.K.; Wijeratne, K.; Gunatilaka, L.; Arnold, A.E. Endohyphal bacterium enhances production of indole-3-acetic acid by a foliar fungal endophyte. PLoS One 2013, 8, e73132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, T.; Li, W.; Hong, J.; Xu, J.; Yu, Z. Endosymbiotic bacteria within the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys musiformis and their potential roles in nitrogen cycling. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1349447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, S.; Nguyen, H.N.; Morales, D., 3rd; House, G.L.; Paudel, S.; Chain, P.S.G.; Rodrigues, D.F. Diversity of fungal microbiome obtained from plant rhizoplanes. Sci Total Environ 2023, 892, 164506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Y.I. Characterization of a Plant Growth-Promoting Endohyphal Bacillus subtilis in Fusarium acuminatum from Spiranthes sinensis. Pol J Microbiol 2023, 72, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeier, S.; Smits, T.H.; Ford, R.M.; Keel, C.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Taking the fungal highway: mobilization of pollutant-degrading bacteria by fungi. Environ Sci Technol 2005, 39, 4640–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, T.; Centler, F.; Hübschmann, T.; Remer, R.; Thullner, M.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Mycelia as a focal point for horizontal gene transfer among soil bacteria. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 36390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. The known and the unknown in soil microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2019, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Guo, Q.; Cao, S.; Zhan, Z. Diversity of bacterium communities in saline-alkali soil in arid regions of Northwest China. BMC Microbiol 2022, 22, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, M.S.; Hussain, M.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, D.; Li, X.; Song, S.; Wang, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, S. Root-Zone Restriction Regulates Soil Factors and Bacterial Community Assembly of Grapevine. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüneberg, K.; Schneider, D.; Siebe, C.; Daniel, R. Drylands soil bacterial community is affected by land use change and different irrigation practices in the Mezquital Valley, México. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Castellanos, M.L.; Rodríguez-Segura, Z.; Villalobos, F.J.; Hernández, L.; Lina, L.; Nuñez-Valdez, M.E. Pathogenicity of Isolates of Serratia Marcescens towards Larvae of the Scarab Phyllophaga Blanchardi (Coleoptera). Pathogens 2015, 4, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez, M.; Romero-López, A. Klebsiella Bacteria Isolated from the Genital Chamber of Phyllophaga obsoleta. Southwestern Entomologist 2017, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, H.; Sabtharishi, S.; Chandel, R.; Gandotra, S. Exploration of gut bacteria in white grub Anomala sp. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), a major pest of vegetables and fruit trees in India. 2020.

- Desirò, A.; Salvioli, A.; Ngonkeu, E.L.; Mondo, S.J.; Epis, S.; Faccio, A.; Kaech, A.; Pawlowska, T.E.; Bonfante, P. Detection of a novel intracellular microbiome hosted in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Isme j 2014, 8, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Desirò, A.; González, J.B.; Tao, G.; Morton, J.B.; Bonfante, P.; Pawlowska, T.E. ' Candidatus Moeniiplasma glomeromycotorum', an endobacterium of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2017, 67, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovetsky, O.A.; Caruso, T.; Brennan, F.P.; Wall, D.; Pylni, S.; Doyle, E. Spores of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi host surprisingly diverse communities of endobacteria. New Phytologist 2024, 242, 1785–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.F.; Ishii, T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores host bacteria that affect nutrient biodynamics and biocontrol of soil-borne plant pathogens. Biol Open 2012, 1, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, H.; Guo, C. Bacillus subtilis HSY21 can reduce soybean root rot and inhibit the expression of genes related to the pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2021, 178, 104916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russi, A.; Almança, M.A.K.; Schwambach, J. Bacillus subtilis strain F62 against Fusarium oxysporum and promoting plant growth in the grapevine rootstock SO4. An Acad Bras Cienc 2022, 94, e20210860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertkova, E.; Kabilov, M.R.; Yaroslavtseva, O.; Polenogova, O.; Kosman, E.; Sidorenko, D.; Alikina, T.; Noskov, Y.; Krivopalov, A.; Glupov, V.V.; et al. Links between Soil Bacteriobiomes and Fungistasis toward Fungi Infecting the Colorado Potato Beetle. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.P.S.; Keerthana, A.; Priya; Singh, S. K.; Rai, D.; Jaiswal, A.; Reddy, M.S.S. Exploration of culturable bacterial associates of aphids and their interactions with entomopathogens. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barelli, L.; Waller, A.S.; Behie, S.W.; Bidochka, M.J. Plant microbiome analysis after Metarhizium amendment reveals increases in abundance of plant growth-promoting organisms and maintenance of disease-suppressive soil. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, N.; Greco, C.; Drott, M.T.; Koss, M.J.; Ludwikoski, I.; Keller, N.M.; Keller, N.P. Bacterial hitchhikers derive benefits from fungal housing. Curr Biol 2022, 32, 1523–1533.e1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, G.; Qian, Y.; Liu, R.; Guo, N.; Mi, W.; et al. Horizontal gene transfer allowed the emergence of broad host range entomopathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 7982–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, R.W.; Tao, W.; Bedzyk, L.; Young, T.; Chen, M.; Li, L. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol 2000, 182, 4458–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).