2. Materials and Methods

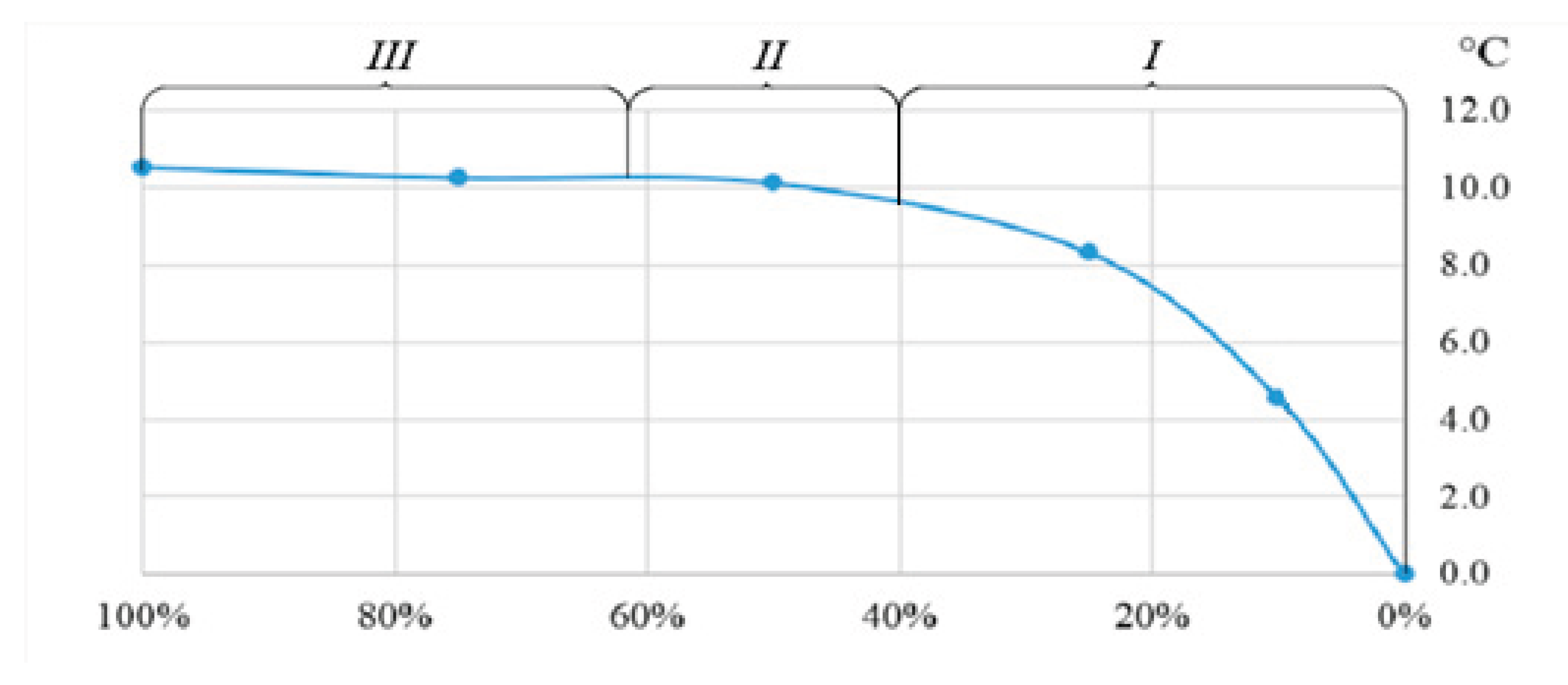

The implementation of the physical potential of water evaporative cooling depends largely on the properties of the media involved in the process and the nature of their interaction. The process is multifactorial and depends primarily on the parameters of the cooled air (outdoor air temperature

to and initial air moisture content

di), which are determined by weather conditions and the required microclimate (

tint, φ

int) [

11]. The listed fundamental indicators determine the physical potential of water evaporative cooling, while the completeness of its realization depends on the characteristics of a particular unit and is the subject of optimization problem [

12,

13].

The efficiency of saturation of the treated air with moisture, as well as the degree of its cooling, depends on the area of contact between the media, aerodynamic characteristics, process duration and other characteristics. Of those metrics that we can effectively influence, the area of the interaction surface is the most significant. It is important to note that it is different from the sprayed surface area and is determined by the properties of the interacting media, flow rate, and spraying method [

14,

15,

16].

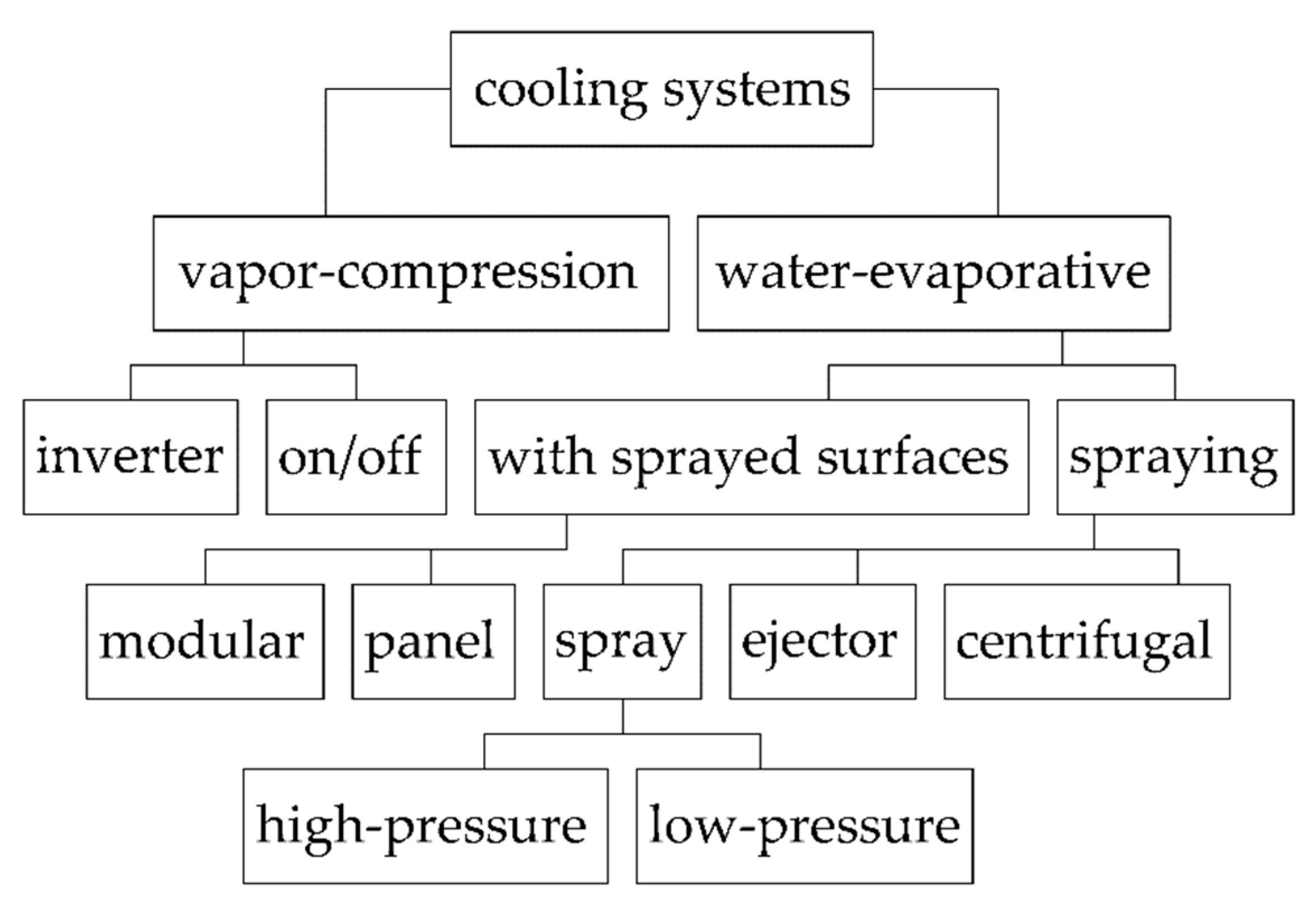

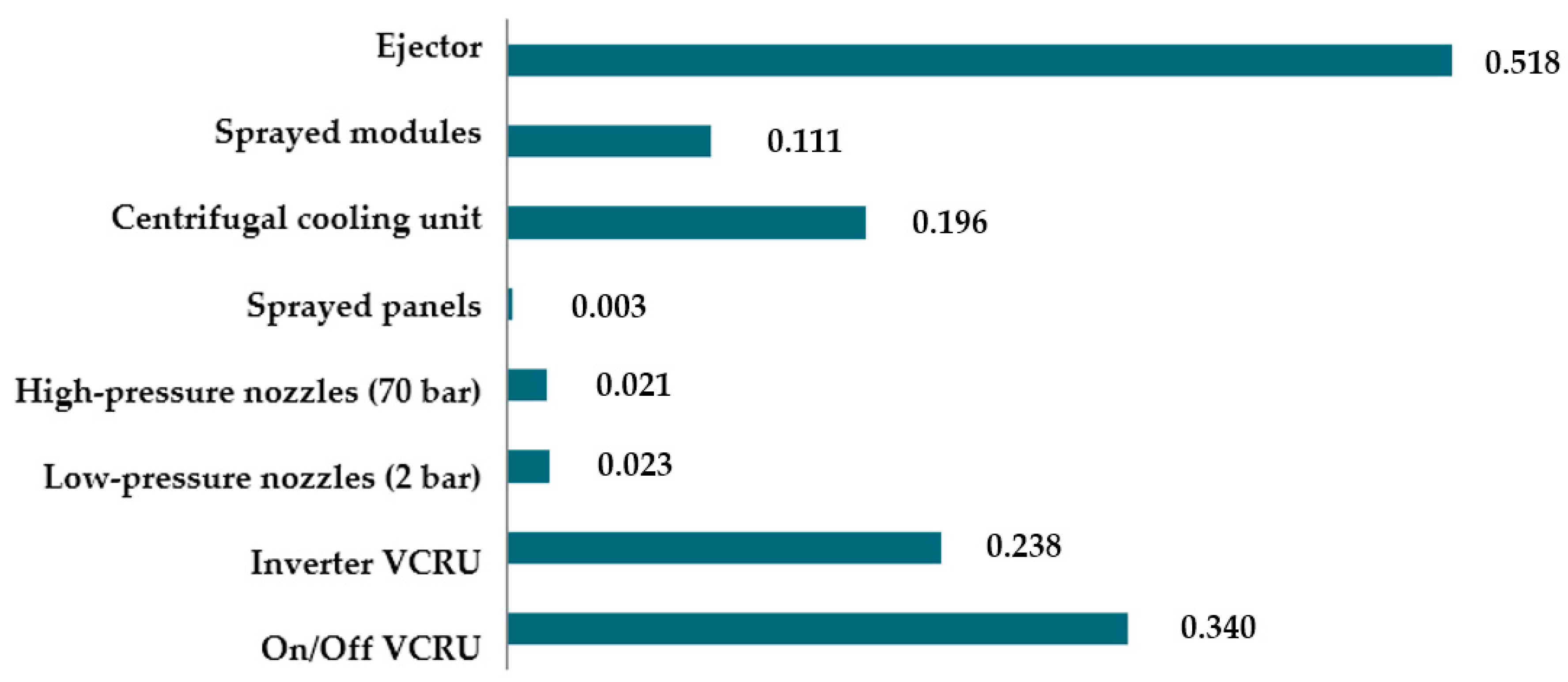

The use of water-evaporative cooling is significantly cheaper than vapor-compression refrigeration units. Water is extracted at the facility, and the specific energy consumption per unit of cold produced is an order of magnitude lower. At the same time, water is a valuable resource and it is reasonable to identify the dependence that determines the minimum water flow rate that guarantees the realization of the physical potential of water evaporative cooling in a particular unit [

17].

The above can be written down in mathematical form:

where

to is the outside air temperature, °С;

di, df is the initial and final air moisture content, g/kg of dry air;

S is the area of the sprayed surface, m

2;

Re is the Reynolds criterion;

is the process duration, s;

is the edge angle of wetting of the heat exchanger surface, °;

b, h are the dimensions of the tube cross-section, m;

Qw is hourly water flow rate, m

3/h;

ПΣ,

Пs.f. is the total length of the water-air interaction line in the cross-section at jet and film modes, m;

C(

Ca+2, Mg+2) is the concentration of hardness salts.

Let’s consider the process of water-evaporative cooling in a heat exchanger consisting of cellular polycarbonate plates with channels of square cross-section. A downward flow of a two-phase mixture (water and air) in a rectangular channel is assumed, with liquid flowing down the walls and the core of the section represented by a flow of cooled air and small liquid droplets. As assumptions, we take the air and water flow rate to be constant, with the water flow rate determined from the condition of sufficiency to saturate the cooled air to a given moisture content.

In steady flow, liquid droplets are deposited on the walls of the unit. The process of water-evaporative cooling involves evaporation of liquid over the surface of the film with decreasing thickness of the film itself, while on an infinitesimal section dy the thickness of the liquid layer can be assumed to be unchanged.

In the steady-state regime the droplet sizes are negligibly small and commensurate with the sizes of molecules, the vapor-gas medium can be considered quasi-homogeneous. The droplet velocities are commensurate with the gas flow velocity, hence a two-speed regime takes place. The flow velocity of the vapor-gas medium is higher than that of the liquid film, which leads to accelerated flow of the liquid phase and increases the drag for the vapor-gas phase. Vertical orientation of channels in space excludes the influence of gravity on the character of phase velocity distribution in the cross section, i.e., axisymmetric distribution is characteristic.

In considering the problem at hand, it is important to determine the volume ratio of the gas and liquid phases. In the cross-section the area of gas phase S

г is distinguished and related to the cross-sectional area of the channel S

i (cross-sectional area of one tube), the obtained value is called the volume concentration of the gas medium:

where

Sg is the cross-sectional area of the tube occupied by the gas phase, m

2;

Si is the cross-sectional area of the tube, m

2.

The fraction of the channel cross-section occupied by the liquid phase can be determined from the Equation (1-γ).

It is known that at gas volume concentrations less than 0.6 - 0.8 the liquid phase can form overlapping regions, and depending on the ratio of velocities and volume concentrations a bubble or slug flow regime can be formed. Only the dispersed and dispersed-film regimes are considered here. The liquid films can be completely interlocked, forming a closed ring in cross-section, or form separate jets. The nature of the film formed is largely determined by the properties of the interacting substances, with wetting ability having the most significant influence.

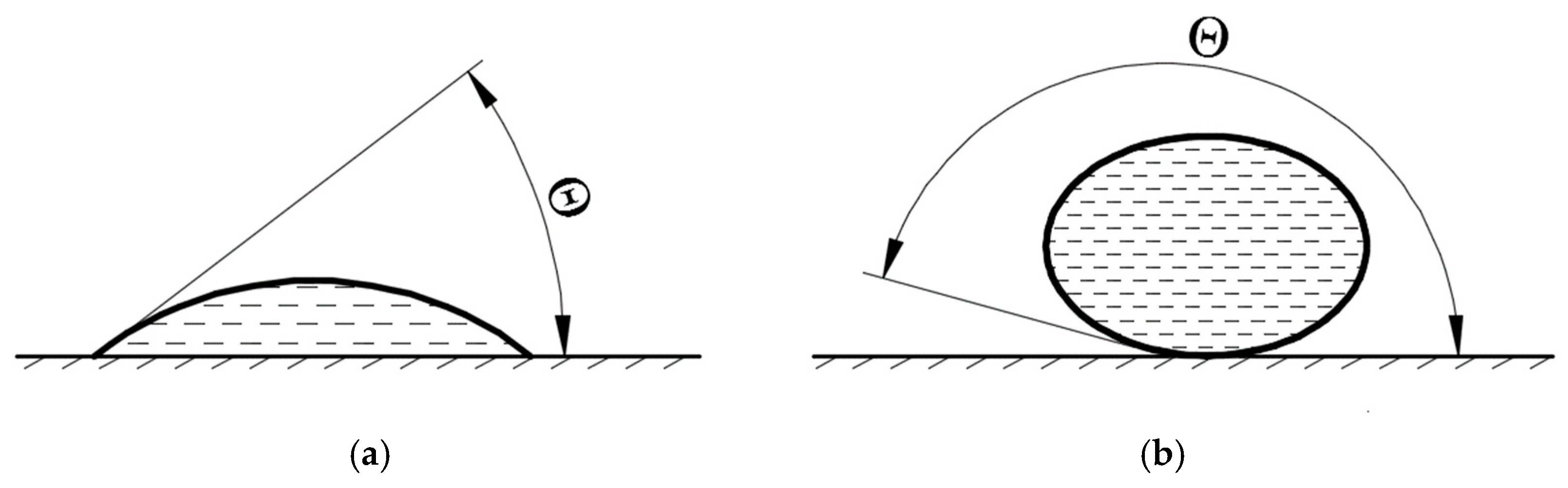

When considering wetting ability, two limiting cases could be distinguished: absolute wetting ability and absolute non-wetting. In the first case the marginal wetting angle is 0° and the liquid spreads out in a thin film over the surface, in the second case the marginal wetting angle is 180° and the moisture collects in droplets. In most real cases there is an intermediate state (

Figure 5).

The relationship between the surface energies of interacting bodies and the equilibrium boundary wetting angle is determined by Young’s law (16).

where σ is the surface energy at the interface; 1, 2, 3 are the liquid, gas and solid, respectively.

3. Results

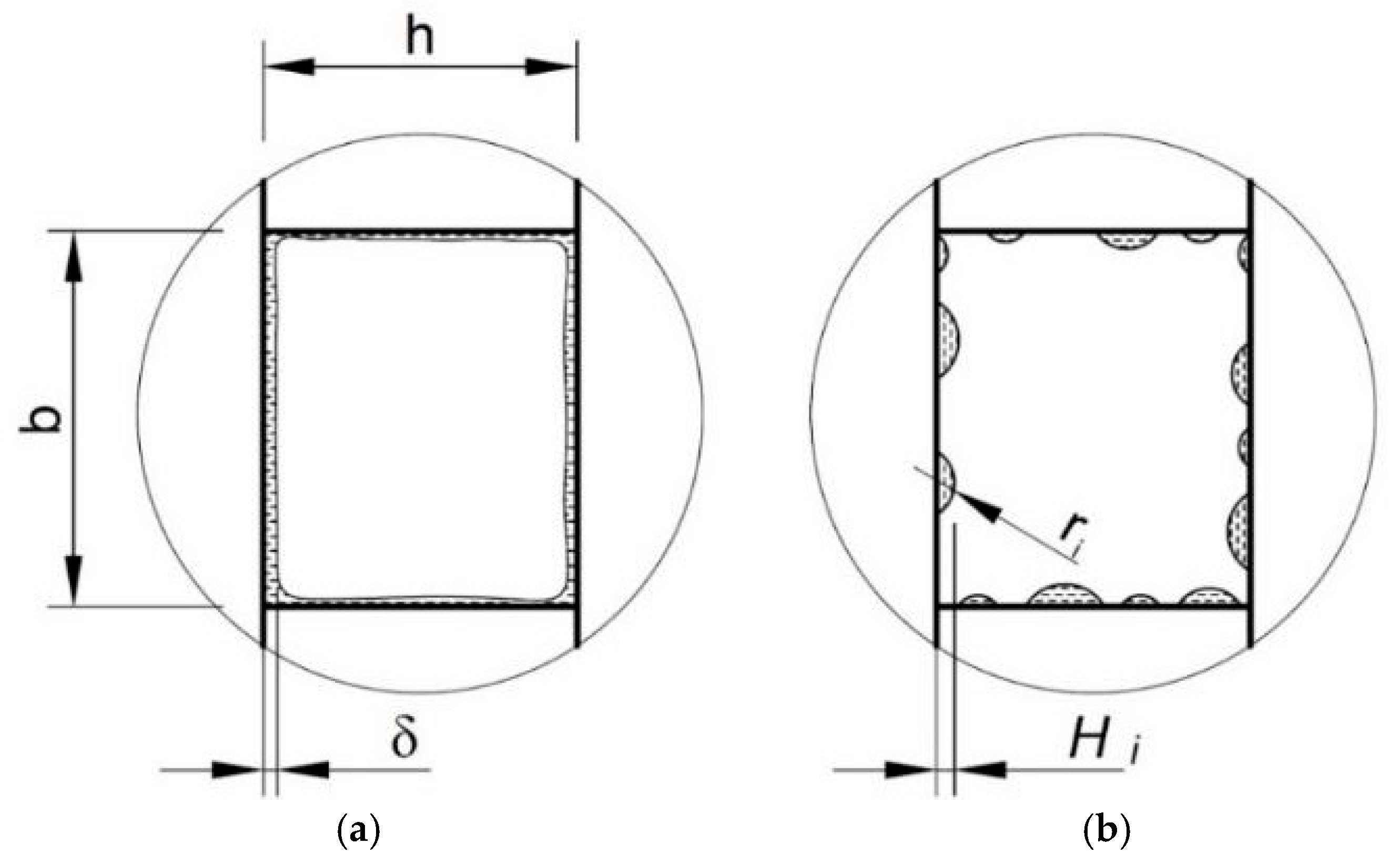

Let us consider an example of film and jet fluid flow in the cross and longitudinal sections of the unit. The unit is a plurality of elementary tubes, let us consider the process using a single tube as an example [

18].

In case of good wetting ability and sufficient water flow a continuous film is formed (

Figure 6a), otherwise water collects in drops or runs down the surface in separate streams, in hydrodynamics of jets such phenomenon is called semi-limited jet (

Figure 6b and

Figure 7).

The volumetric gas concentration can also be expressed by the following equation:

where

W, Qw are the air and water flow rates in the cooler, m

3/h.

In the case under consideration, the water flow rate is four orders of magnitude less than the air flow rate, so its effect on the air capacity can be considered insignificant. Consequently, the statement about the constancy of the volumetric flow rate is true.

If the water evaporates completely, dissolved salts are deposited on the surface of the unit. Some form insoluble sludge that contaminates the unit and incurs operational costs for cleaning. Calcium and magnesium salts, so-called hardness salts, have these properties. Taking into account their concentration, water consumption for evaporation should be increased and at least 10% of the circulating water should be discharged to the sewer. Otherwise, the concentration of salts in the recirculate will increase.

Since the contact area of the media is directly proportional to the evaporation rate, the ratio of the surface areas of the jets facing the gas core at different wetting ability will reflect the effect of wetting ability on the efficiency of water-evaporative cooling (humidification of the supply air).

The length of the considered section Δl of the tube decreases at the ratio of areas and has no influence on the described ratio, only the perimeter matters. It is important to obtain a comparative value derived from the ratio of the contact line length at the current marginal wetting angle to the reference contact length.

Let’s call this characteristic the evaporation area conversion factor:

where

SΘ, Sref are the area of contact of media respectively at current value of marginal wetting angle and reference, m

2;

ПΘ, Пref are the lengths of contact line at current marginal wetting angle and reference, m.

It is advisable to take an available well-wetted material as a reference. In water evaporative cooling units, heavy paper is used as the material of choice. The marginal wetting angle for it is 20-30°. 25° is taken as the baseline.

In the case of the film regime, the length of the contact line can be defined as the perimeter of the closed surface by the following equation:

where

b, h are the dimensions of the tube cross section, m (

Figure 7);

δ it the thickness of the liquid film, m.

Water consumption for evaporation is constant and is determined from the condition of sufficiency for the process:

where

ds,do are the moisture content of supply and outdoor air, respectively, g/kg dry air.

Air moisture content is determined using the following equation:

where φ is the relative air humidity, %;

e is the base of the natural logarithm;

t is the air temperature, °C [

12].

Outdoor air parameters are taken from climatic data. The moisture content of the supply air should not be greater than the moisture content of the air in the animal housing, hence one of the limit states will be the equality of the moisture content of the supply and indoor air. Solving (7) and (8) together, we obtain the theoretical water flow rate to ensure the given conditions:

The resulting flow rate must be increased by at least 10% based on the recirculate drainage.

Let us determine the thickness of the liquid film:

After some mathematical transformations, a quadratic equation of the standard form is obtained:

where

are the area and perimeter of the tube, respectively.

Solving jointly 6 and 12 with respect to the perimeter of the film, we obtain:

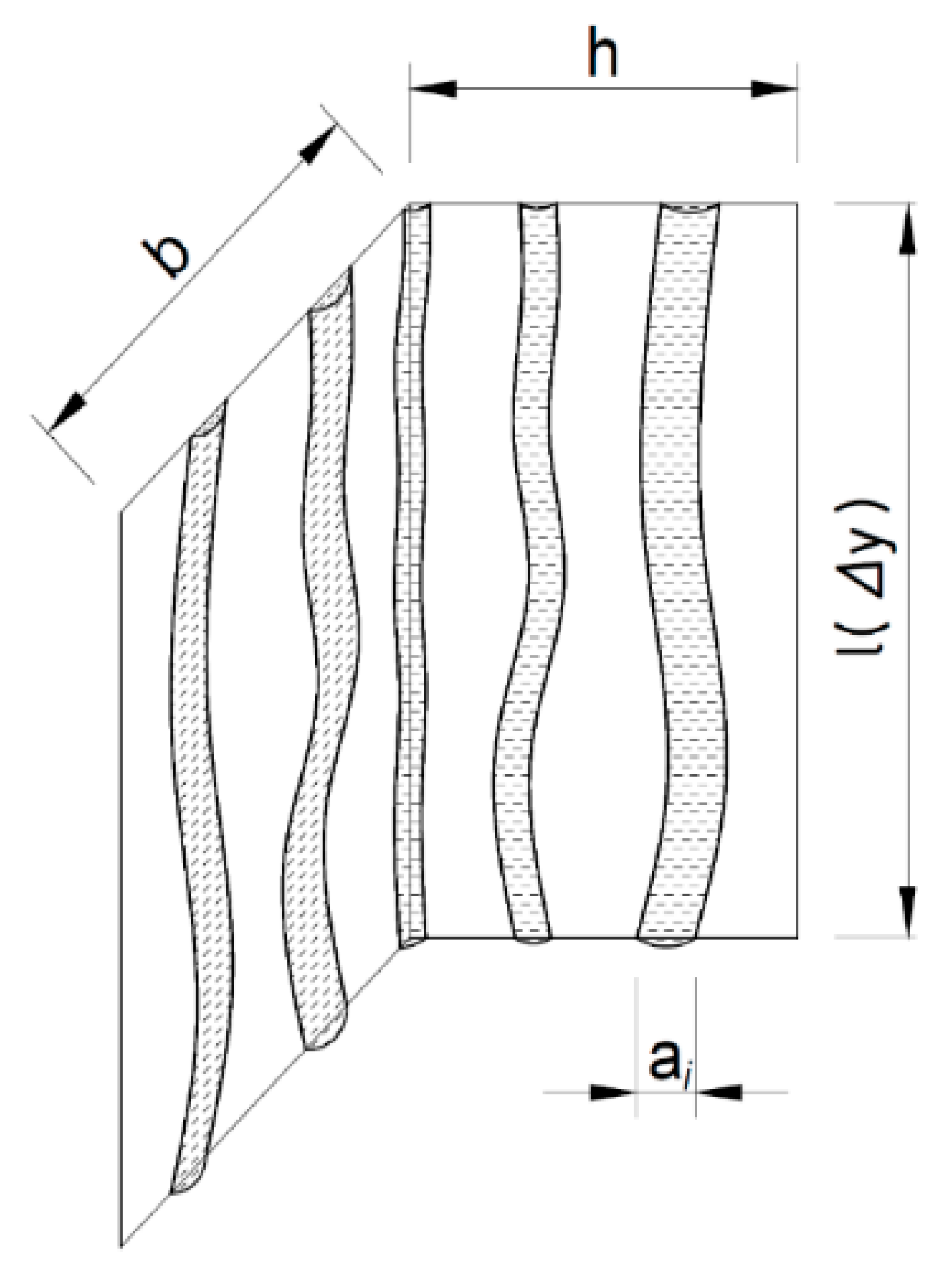

In the jet mode, at the same water flow rate as in the annular mode, the films will cluster under the action of surface tension, tending to adopt an energetically favorable state.

Obviously, the filament band origin is a droplet. Upon reaching a critical size, the drop rolls downward, carried away by gravity and the flow of cross-current air. The process takes place at a constant cooling water flow rate, droplets are formed one after the other, resulting in a filament band.

Water enters the heat exchanger by spraying from nozzles, the droplets have different dispersity and direction of movement, the surface is wetted randomly, i.e., uniformly within each filament bond. Consequently, it is acceptable to assume that the bonds formed will be close in size.

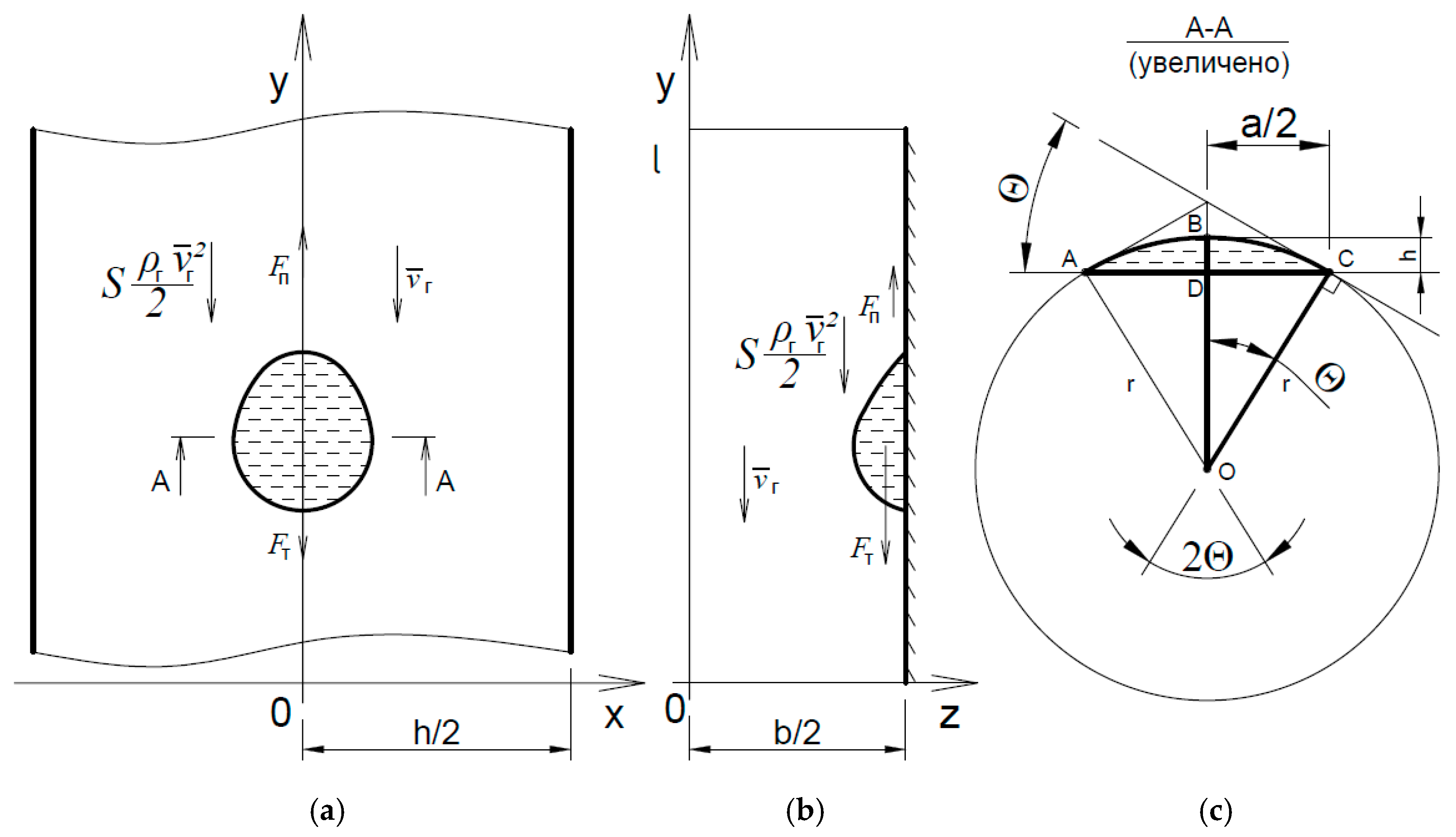

Determination of the total length of the water-air interaction line in the cross-section at the jet regime can be carried out by the following equation:

where

ri is the radius of the

i-th jet, m;

2Θ is the arc opening angle, rad (

Figure 8).

As can be seen from

Figure 8, the edge wetting angle is equal to half of the arc opening angle. For the convenience of calculations we will convert the units of angles from radians to degrees by multiplying by π/180, and the equation will take the following form:

Using the average value of the jet cross-sectional radius, Equation (15) can be rewritten as follows:

where

n is the number of jets;

is the average jet radius in cross section, m.

If the sum of bases is not less than the perimeter of the tube, the jets will close and the flow regime will change to annular film flow. These conditions can be expressed by a dependency:

where

Пi is the perimeter of the tube, m,

is the length of the base of the elementary jet, m.

From the triangle ODC (

Figure 8) we can see that the base “a” (AC) and the radius of the jet are related, hence

To find the radius of the elementary jet, we examine the moment of drop detachment as fundamental. At this point, the droplet is balanced by the action of gravity, the frontal pressure from the airflow on the droplet, and the force of surface tension (

Figure 8b).

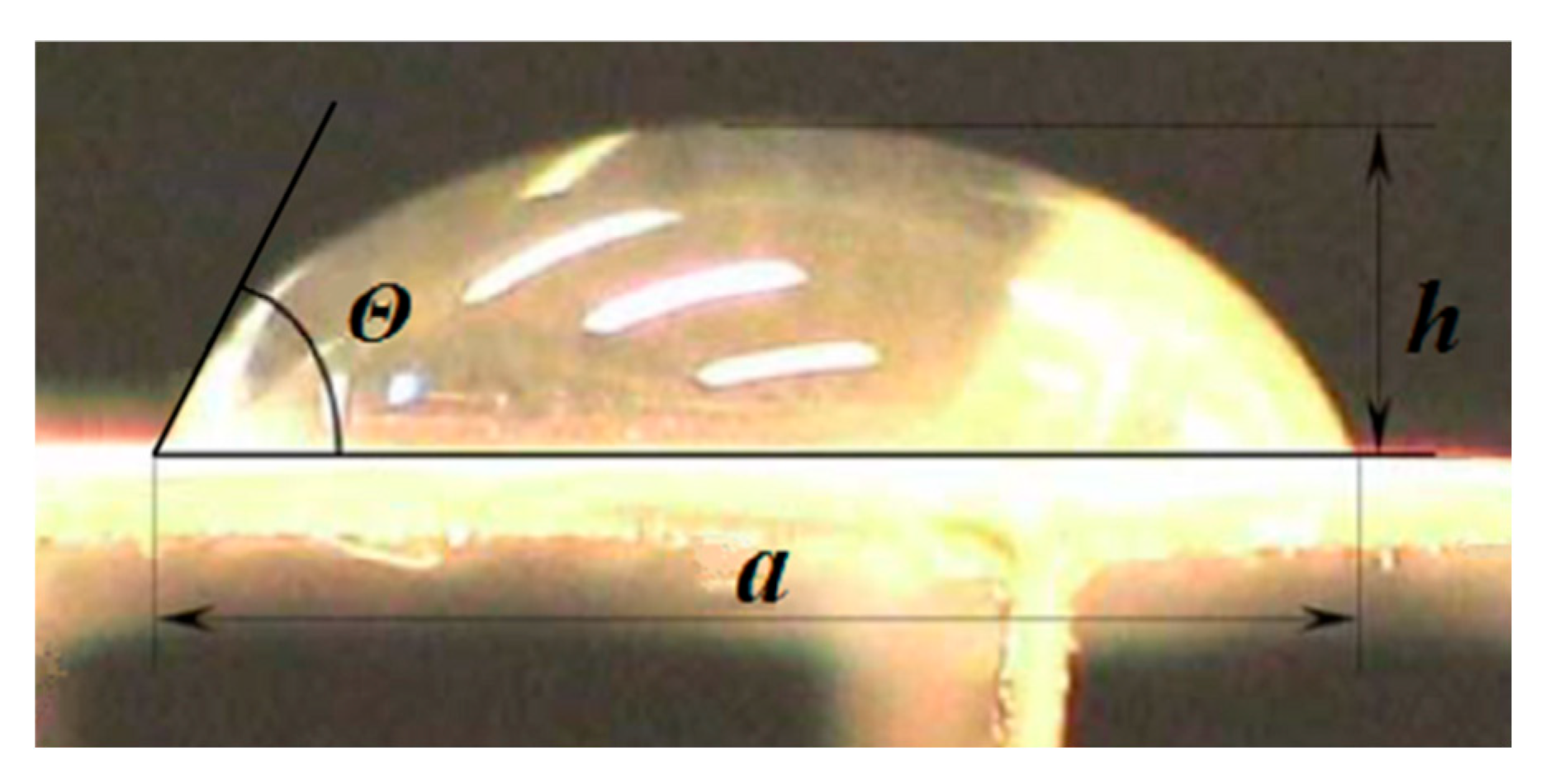

The geometric characteristics of the cross section of the filament bond are assumed to be equal to the parameters of the drop at the moment of detachment. The drop can be represented as a segment of a sphere with radius “r” and base width “a”.

The balance of forces can be expressed by the following formula:

where

S is the frontal area of the drop, m

2;

is the surface tension force, N; σ is the surface tension of water σ = 0.072 N/m).

The force of gravity is defined as the product of the mass of the liquid by the acceleration of free fall

g, and the mass is expressed through the product of the volume by the density:

where ρ

w is the density of water, kg/m

3,

is the drop volume, m

3.

The volume and frontal area of the droplet are calculated using the following equations:

It follows from

Figure 8c that

OD/r = cosΘ, at that

OD = r - h, as a result of mathematical transformations we obtain:

Solving jointly Equations (21) and (23) we obtain:

Substituting Equations (20)-(23) into Equation (19) we obtain:

The solution of Equation (25) will be as follows:

Solving jointly Equations (2) and (22) we can find the number of jets and express the jet regime condition:

Solving together with Equation (5), we determine the conversion coefficient of evaporation area:

Thus, the minimum water flow rate for evaporation can be determined by the formula:

Or, taking into account Equation (9):

where

Qw.min is the theoretical water flow rate to ensure cooling in a given mode, kg/h;

= 1,1 is the drain coefficient,

is the coefficient of evaporation area conversion.

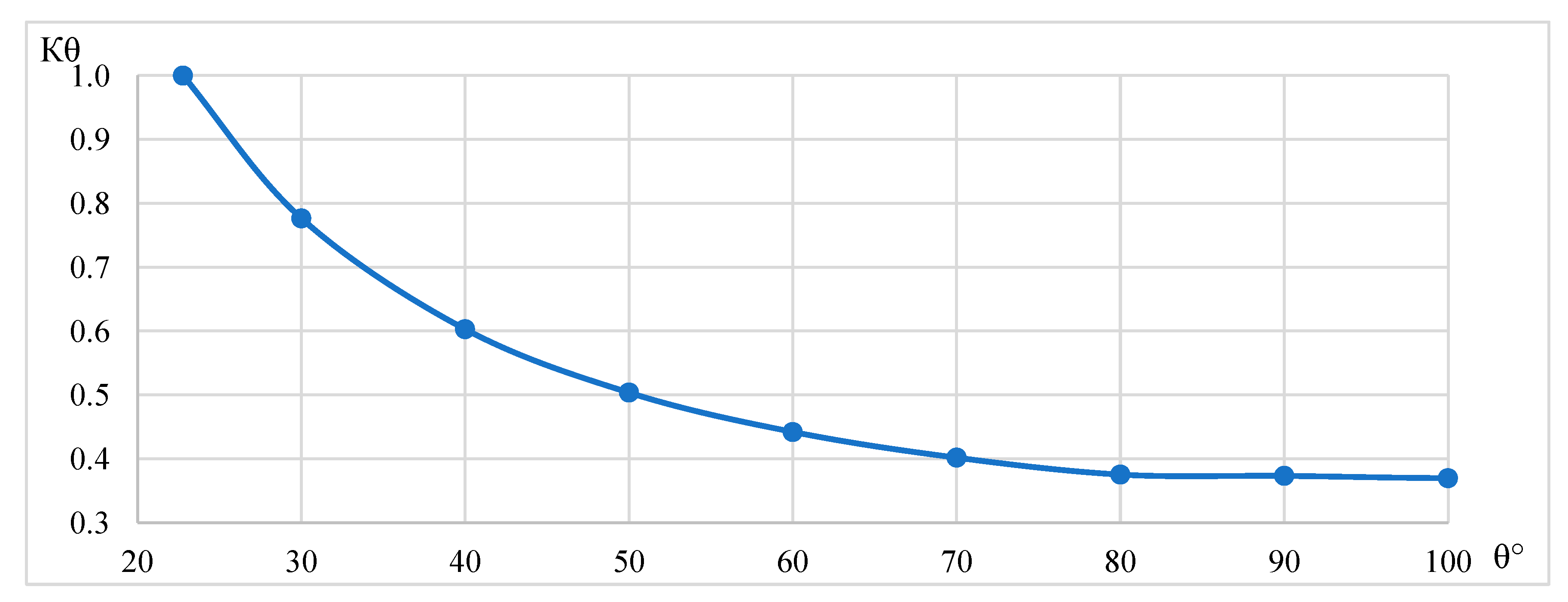

Figure 9 shows the dependence of the relative evaporation area coefficient on the edge angle.

The range of adequate use of the model is in the range of = 20 … 120°. The droplet behavior cannot be described with the assumptions of the model outside of this range of wetting angle values.

At wetting angles above 80°, the coefficient values stabilize and reach 0.36.

The experimentally obtained marginal wetting angle of polycarbonate with water is 63° (

Figure 10).

For surfaces with a marginal wetting angle of 60-65°, water consumption for evaporation should be increased by 2.3-2.4 times compared to the minimum necessary.

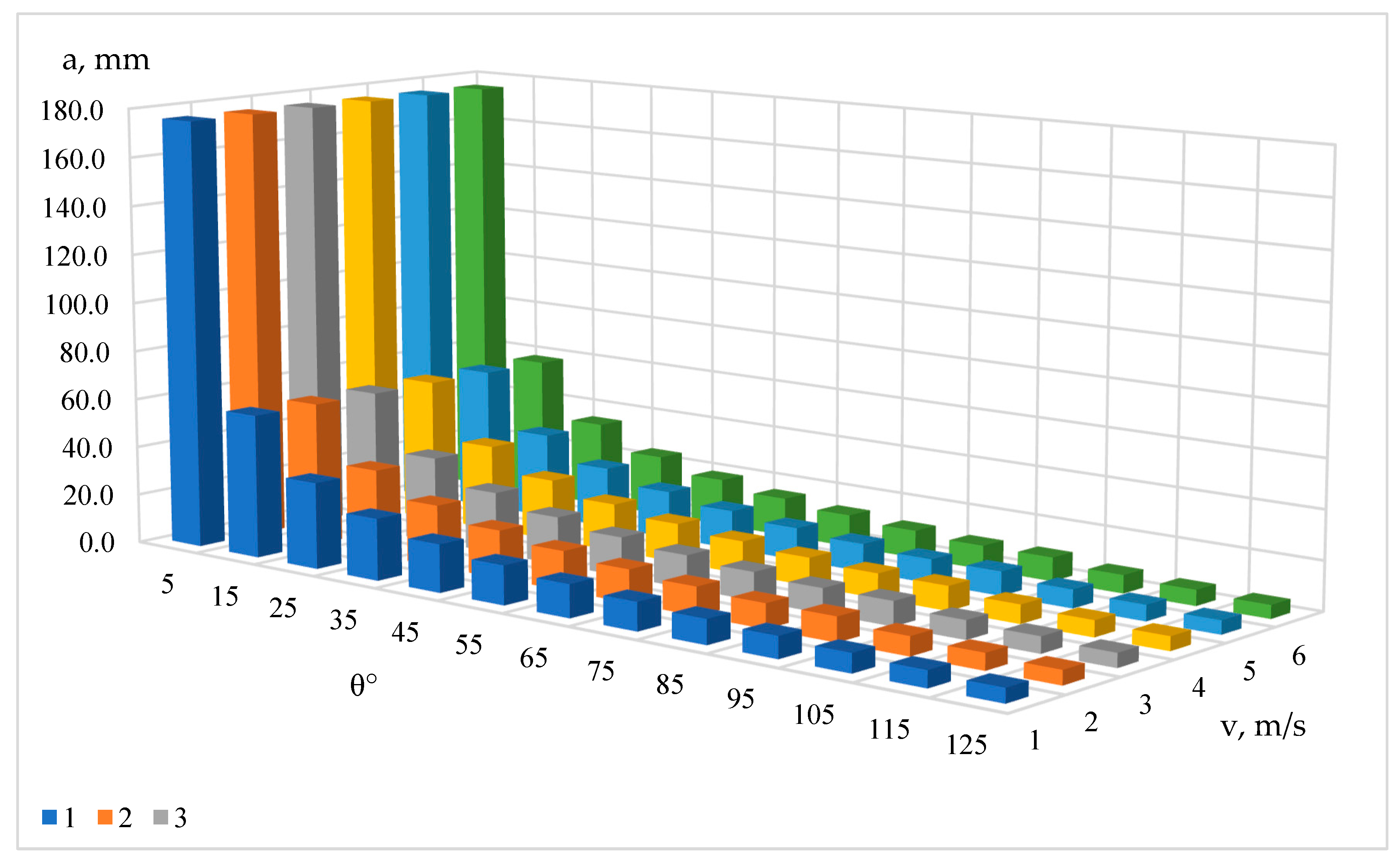

Let us construct a theoretical graph of the dependence of the jet base length on the wetting edge angle and the air flow velocity in the tube (

Figure 11).

According to the obtained model, it can be concluded that in the considered velocity range its influence on the jet base area is insignificant.