Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

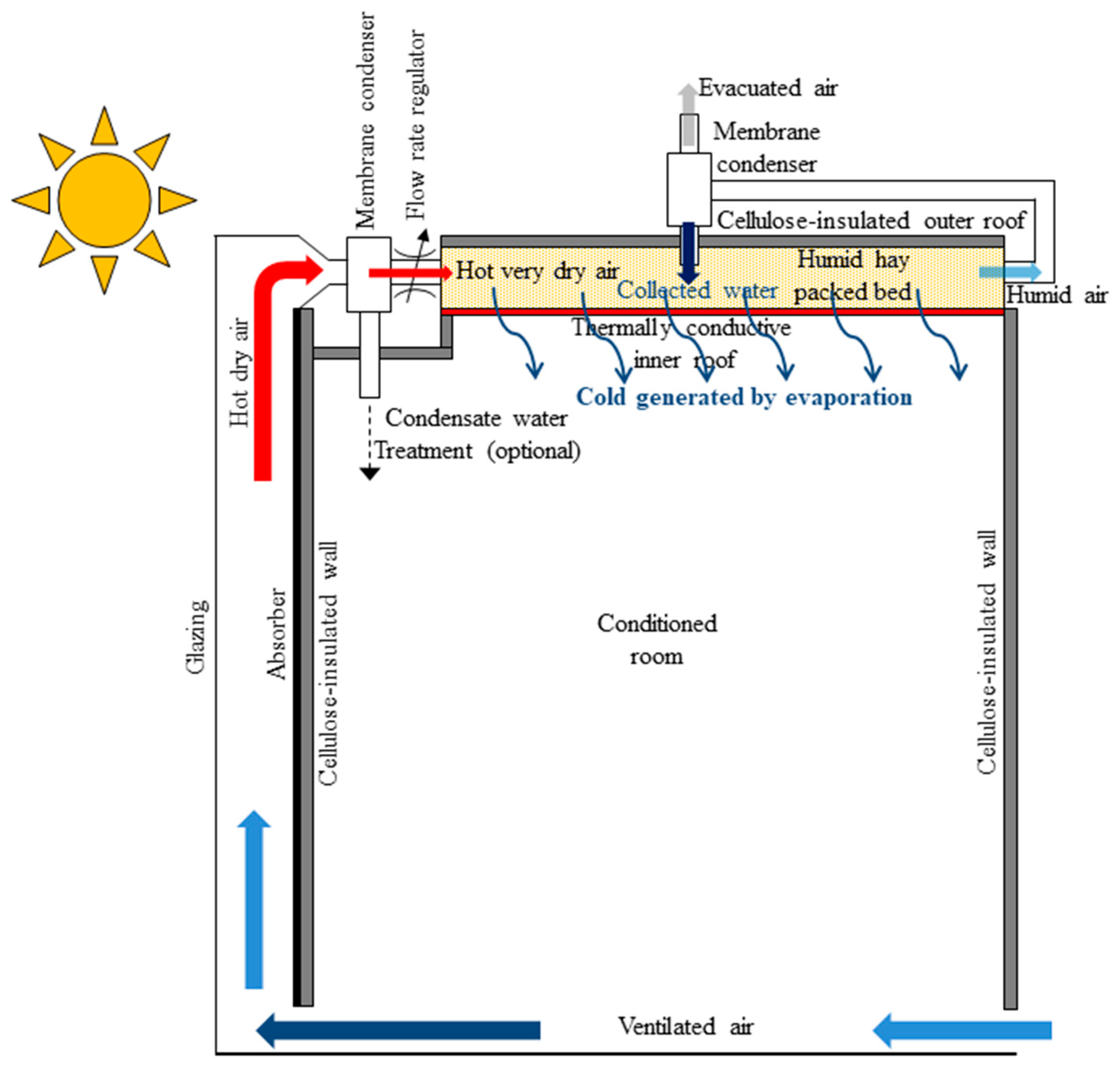

2. Innovative Design

2.1. Description

2.2. Design Key Features

- Hay bed: Uses natural materials for cooling via evaporation. Optimized for airflow, air humidity ratio and hay moisture content;

- Solar-powered ventilation: A solar wall chimney induces hot and dry airflow through the hay bed;

- Insulation and convection: Cellulose insulation for the outer roof and thermally conductive inner roof for efficient cold transfer;

- Moisture recovery: A membrane condenser recovers the moisture from the bed outlet air and returns it to the hay bed to safe water. Moreover, another membrane condenser recovers the moisture from the relatively dry inlet air to further dehumidify it;

- Natural airflow: Promotes ventilation and thermal comfort within the conditioned space;

- Controlled inlet air flow: A flow regulator is used to control the inlet air flow rate.

2.2. Design Key Features

- Sustainable: Eco-friendly materials and processes which minimizes environmental impact;

- Energy efficient: Reduces energy consumption through the use of solar energy;

- Cost-effective: Low operational costs due to free solar;

- Improved indoor air quality: Improves thermal comfort within the conditioned space based on enhanced convection, due to ventilation and cooling effect, due to the evaporation process;

- Scalable: Adaptable to various building sizes and climates.

2.3. Claims

- A sustainable Coupled Solar Ventilation-Evaporative Cooling (SVEC) system comprising:

- Roof-mounted hay bed using a water-evaporation process to generate cooling effect when relatively dry and hot air passes through it;

- Solar wall chimney for inducing natural ventilation and enhancing convection within the conditioned space;

- Cellulose-insulated conditioned room;

- Membrane condenser for recovering moisture from the humid air at the hay bed’s outlet. The recovered moisture is reintroduced into the hay bed;

- Membrane condenser for recovering moisture from the inlet process air to further dry it. The condensate water can be optionally treated to produce potable water.

- 2.

- The sustainable SVEC system of claim 1, wherein the hay bed is insulated at the top with cellulose insulation and using a thermally conductive inner roof at the bottom to efficiently transfer cold via convection to the cellulose-insulated conditioned room.

- 3.

- The sustainable SVEC system of claim 1, wherein the solar wall chimney uses solar energy to induce natural ventilation, reducing reliance on fossil energy sources and minimizing environmental impact.

- 4.

- The sustainable SVEC system of claim 1, wherein optimizing the airflow rate, air humidity ratio and hay moisture content improves the cooling effect of the system.

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Assumptions

- Uniform temperature distribution in the hay bed: In our proposed system, hot air flows through the hay-packed bed, where evaporation cools the hay bed. If the airflow is well-distributed, spatial temperature differences inside the bed remain small. This makes reasonable the assumption of uniform temperature. In practical applications, engineering designs often ensure proper airflow distribution to maintain efficiency which supports this assumption;

- Steady-state conditions: The system is assumed to operate continuously without significant variations over time. This means that temperature and humidity levels remain stable. Since many industrial and applied research works focus on steady performance rather than transient fluctuations, this assumption simplifies the analysis without significantly affecting accuracy;

- Constant air properties: Variations in air density, specific heat and other thermophysical properties due to temperature and humidity changes are often small enough to be negligible. Using average values is common in engineering models as the errors introduced are minor compared to the overall uncertainties in realistic conditions;

- No resistance to heat transfer: This is justified by the fact that heat transfer occurs instantaneously since the hay bed has high surface area and good thermal contact with the passing air. In many practical designs, the heat exchange process is efficient enough that additional resistance effects have minimal impact on the overall system behavior;

- No condensation or heat generation: The system is designed in the way that air remains unsaturated which prevents condensation inside the hay bed. No additional heat sources such as chemical reactions or external heaters affect the thermal balance. Thus, it is reasonable to exclude internal heat generation in the model.

3.2. Modeling

3.2.1. Air-Hay Energy Transfer

3.2.2. Energy Needed for Evaporation of Water in Hay Bed

3.2.2. Final Temperature of Hay

4. Simulation Results and Discussions

4.1. Simulation Procedure

- Parameter definition;

- Initial hay temperature;

- Inlet Air humidity Ratio;

- Moisture content;

- Airflow rate;

- Bed dimensions;

- Physical properties such as latent heat, specific heat and densities.

- 2.

- Bulk property calculations;

- Hay bed density, total mass, and water content are determined.

- 3.

- Energy balance analysis;

- The air mass flow rate, heat transfer from air to hay and the energy required for moisture evaporation are computed.

- 4.

- Simulation execution.

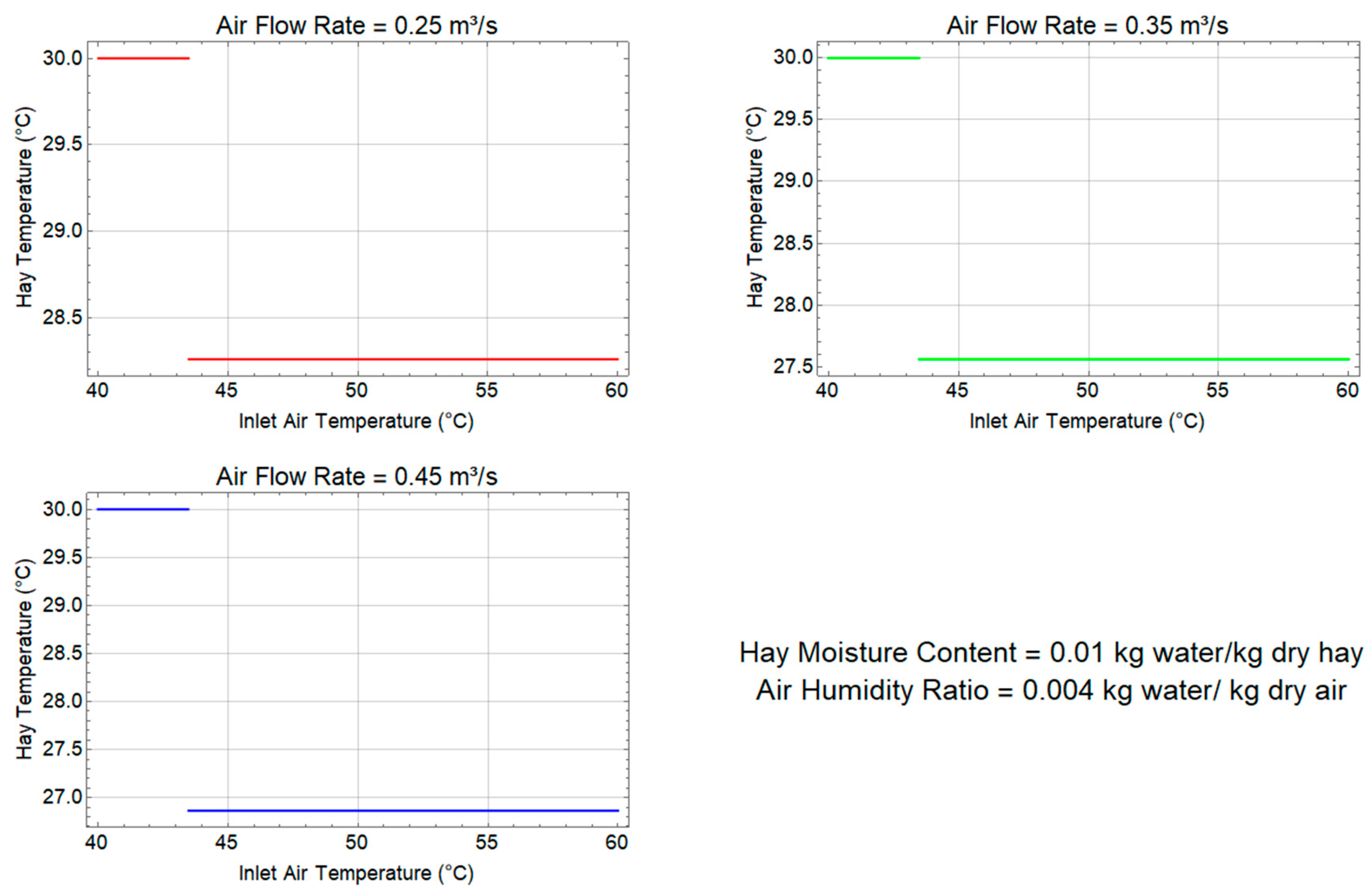

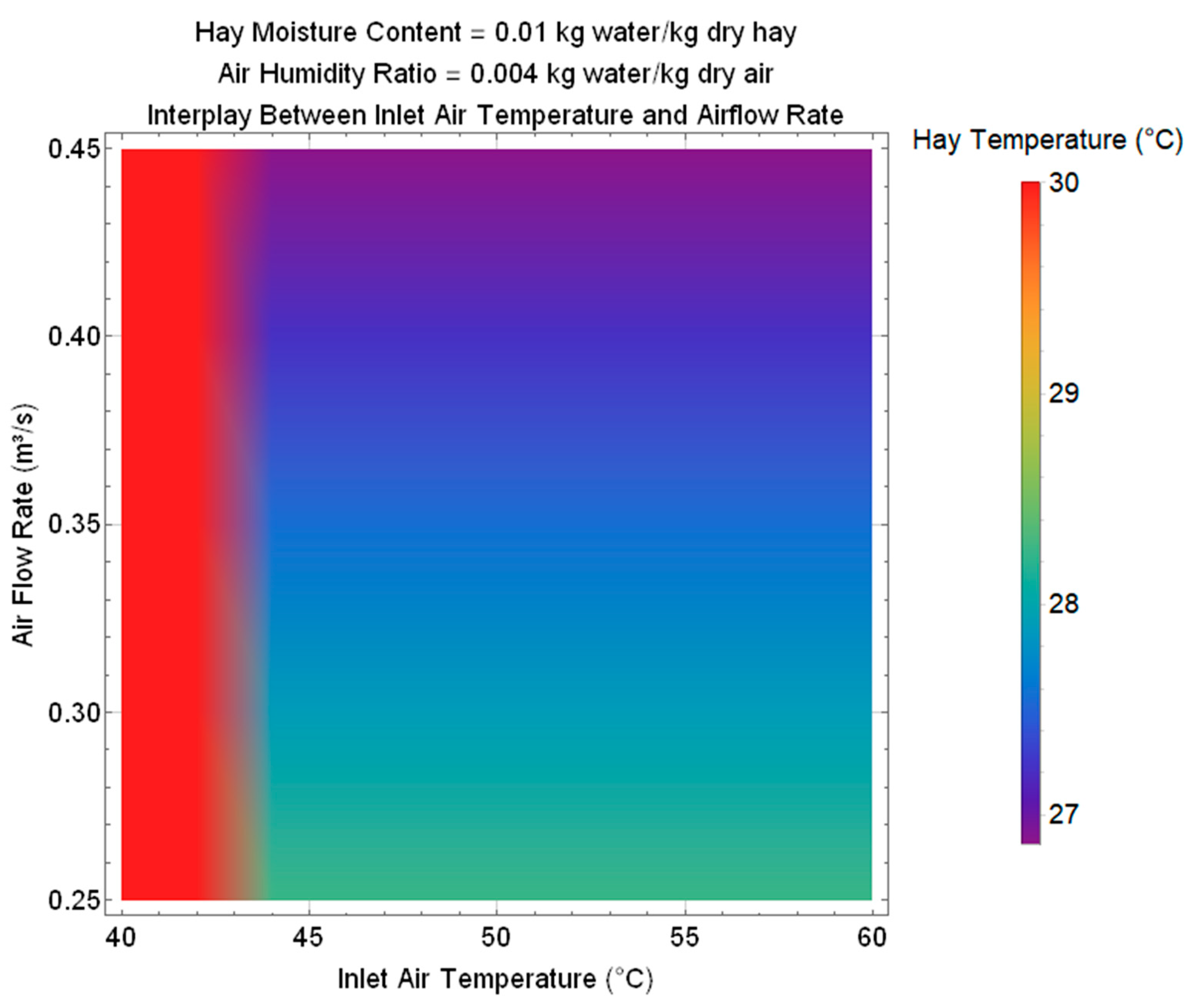

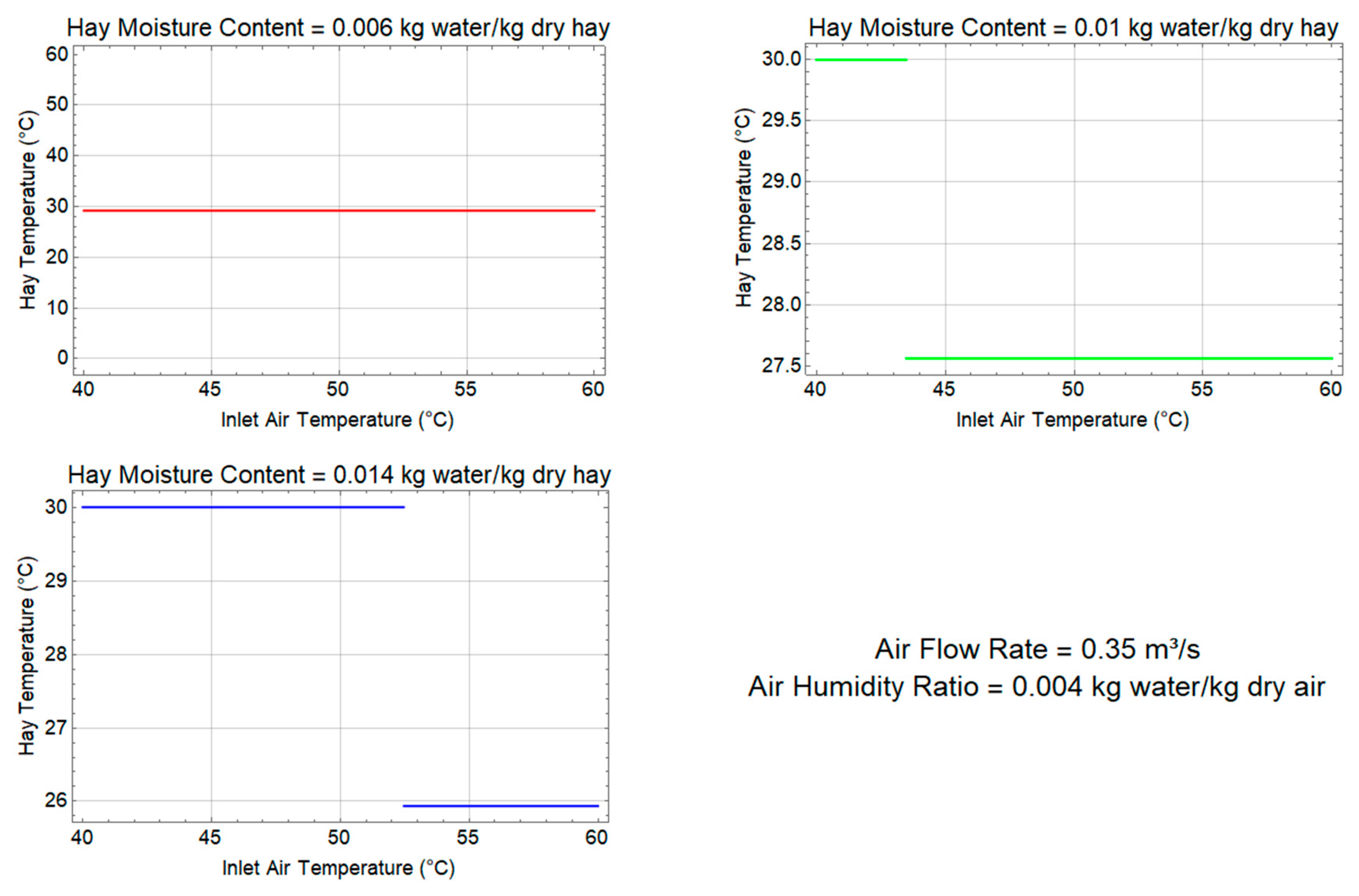

- The model is run for air temperatures between 40–60 °C and hay moisture contents between 0.005–0.015 kg water/kg dry hay;

- 2D and density plots visualize temperature variations.

| Variable | Value | |

| Initial temperature of hay Th,i | 30 °C | |

| Justification: Although the study assumes steady-state conditions, initial hay temperature is used as a reference for energy balance calculations, not as an indication of a transient process. It represents the hay’s temperature before interacting with the airflow and serves as a baseline for determining the final equilibrium temperature. | ||

| Air temperature | [40 °C; 60 °C] | |

| Justification: The most suitable air temperature range for effective evaporative cooling is generally 25–40 °C. However, in our design, the air is supplied by a solar chimney to ensure proper ventilation. Since the air temperature in a solar chimney is naturally higher than 25–40 °C, a range of 40–60 °C remains suitable only if two key conditions are met: (1) the air must be sufficiently dry and (2) the hay must be continuously wetted to sustain effective evaporative cooling. These 2 conditions should be ensured by the proposed design. | ||

| Moisture content of hay Xw | 0.006 ; 0.01; 0.014 kg water/kg dry hay | |

| Justification: Practical values for effective evaporative cooling, ensuring sufficient moisture for heat absorption while preventing excessive saturation. These values align with typical hay moisture levels and the 40–60 °C air from the solar chimney. | ||

| Humidity ratio of the air ωa | 0.002; 0.004; 0.006 kg water/kg dry air | |

| Justification: These values are reasonable and align with real atmospheric conditions, particularly in dry and semi-dry regions. In reality, very dry air, such as that found in desert climates, can have a humidity ratio as low as 0.002 kg/kg, while typical ambient air in many regions ranges between 0.004 and 0.006 kg/kg, especially in warm conditions. | ||

| Flow rate of air FR | 0.25 ; 0.35 ; 0.45 m3/s | |

| Justification: Ensure an optimal balance between evaporative cooling and ventilation. The lower value: 0.25 m³/s allows more time for moisture evaporation which maximizes cooling. The higher value: 0.45 m³/s enhances airflow and heat removal. The intermediate value: 0.35 m³/s provides a balanced approach. | ||

| Porosity of hay packed bed ε | 0.85 | |

| Justification: Ensure a balance between airflow and heat transfer efficiency. Higher porosity than 0.85 facilitates better ventilation at the expense of weaker heat exchange. While, lower porosity than 0.85 enhances heat exchange but may restrict airflow which potentially limits moisture removal and heat exchange. | ||

| Specific heat of hay Cp,h | 1.8 kJ/kg hay | |

| Density of dry hay ρh | 400 kg dry hay/m3 hay | |

| Specific heat of air Cp,a | 1.006 kJ/kg°K | |

| Density of air ρa | 1.11 kg/m3 | |

| Length of hay packed bed L | 2 m | |

| Cross-sectional area of hay packed bed A | 0.01 m | |

| Latent heat of evaporation He | 2260 kJ/kg | |

5. Conclusions

- Innovative sustainable design for a Coupled Solar Ventilation-Evaporative Cooling (SVEC) System is developed;

- Numerical performance analysis is carried out to assess the evaporative cooling effect of the proposed design:

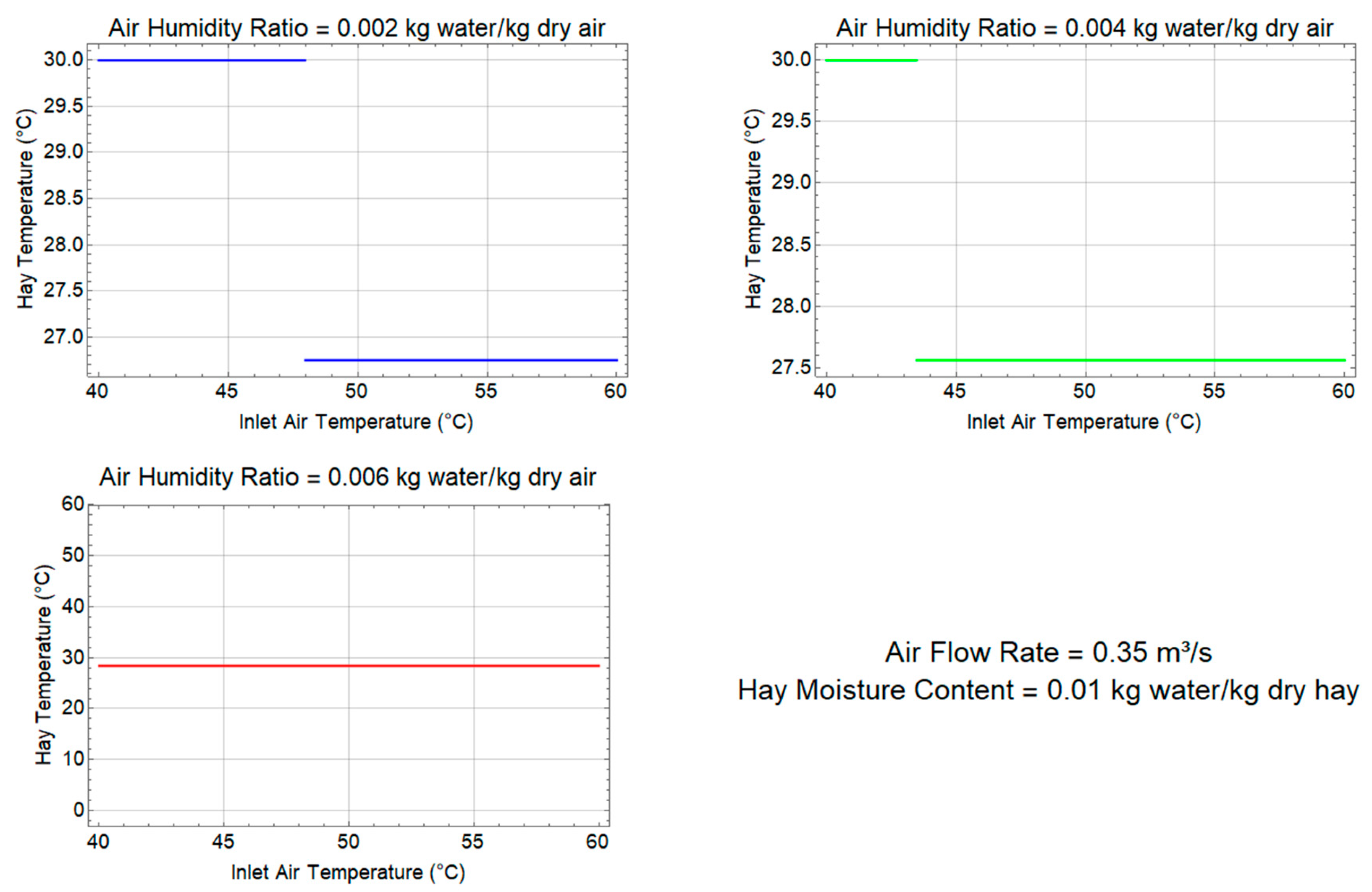

- For a fixed hay moisture content and air humidity ratio around 0.01 kg water/kg dry hay and 0.004 kg water/kg dry air respectively, when the air flow rate increases as 0.25 m3/s, 0.35 m3/s and 0.45 m3/s, the hay temperature decreases from 30 °C to reach 28.2 °C, 27 °C and 26.9 °C respectively when the inlet air temperature exceeds the threshold of 43.5 °C. A plot is provided to serve as a tool for presizing or optimizing the proposed cooling system as well as precisely selecting the operating parameters, based on inlet air temperature and airflow rate;

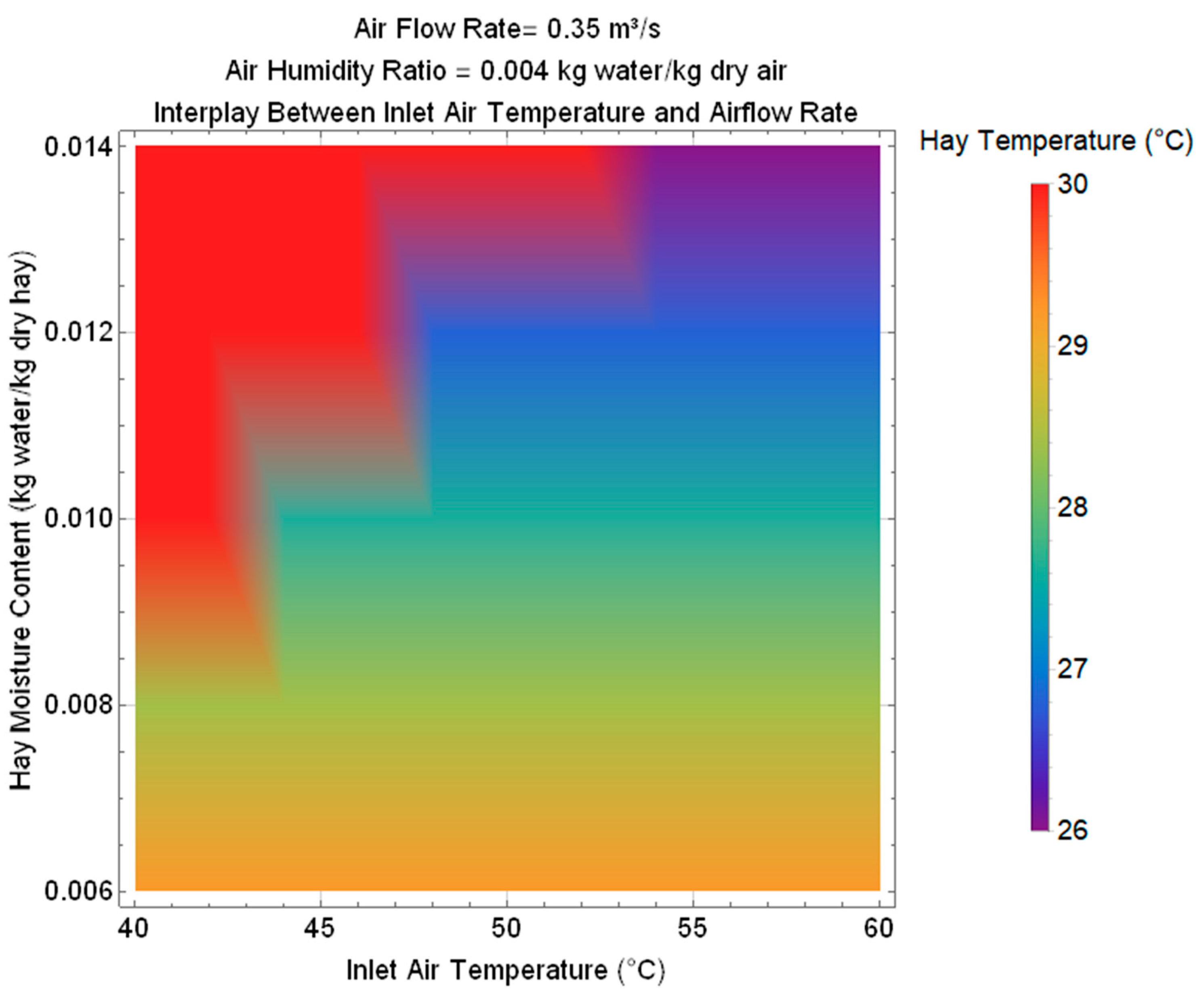

- For a fixed air flow rate and air humidity ratio around 0.35 m3/s and 0.004 kg water/kg dry air respectively, the hay temperature remains slightly below 30 °C when the hay moisture content is 0.006 kg water/kg dry hay. The hay temperature decreases to reach 27.5 °C and 26 °C when the hay moisture content is 0.01 kg water/kg dry hay and 0.014 kg water/kg dry hay respectively when the inlet air temperature exceeds the threshold of 43.5 °C and 52.5 °C respectively. A plot is provided to serve as a tool for presizing or optimizing the proposed cooling system as well as precisely selecting the operating parameters, based on inlet air temperature and hay moisture content;

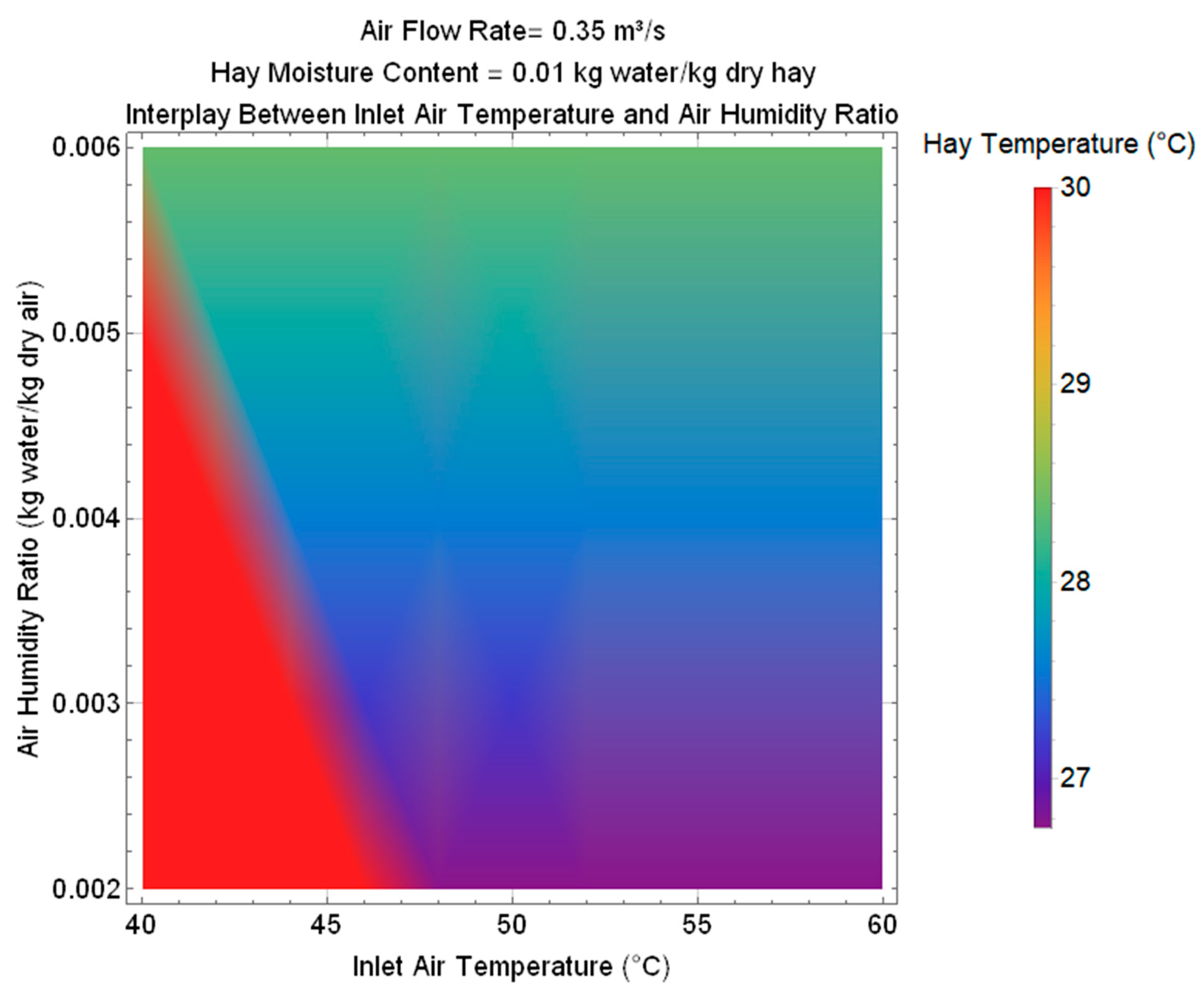

- For a fixed air flow rate and hay moisture content around 0.35 m3/s and 0.01 kg water/kg dry hay respectively, The hay temperature decreases to reach 26.8 °C and 27.5 °C for an air humidity ratio around 0.002 kg water/kg dry air and 0.004 kg water/kg dry air respectively when the inlet air temperature exceeds the threshold of 48 °C and 43.5 °C respectively. The hay temperature remains slightly below 30 °C when the air humidity ratio is around 0.006 kg water/kg dry air. A plot is provided to serve as a tool for presizing or optimizing the proposed cooling system as well as precisely selecting the operating parameters, based on inlet air temperature and air humidity ratio.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Variable | Description | Unit |

| A | Area of the cross section | m2 |

| Cp | Specific Heat | J/kgK |

| d | Diameter | m |

| FR | Flow rate | m3/s |

| g | Gravitational acceleration | m/s2 |

| H | Latent heat | J/kg |

| h | Vertical chimney height | m |

| L | Length | m |

| m | Mass | kg |

| Mass flow rate | kg/s | |

| Actual mass change | kg/s | |

| P | Pressure | N/m2 |

| Q | Heat | J |

| R | Universal gas constant | J/kg.K |

| T | Temperature | K |

| X | Moisture content | kg water/kg dry hay |

| Bed porosity | - | |

| Pressure difference | N/m2 | |

| Dynamic viscosity | Ns/m2 | |

| ρ | Density | m3/kg |

| Air Humidity Ratio | kg water/kg dry air | |

| Subscript | Description | |

| a | Air | |

| amb | Ambient | |

| atm | Atmospheric | |

| b | Bed | |

| c | Chimney | |

| evap | Evaporation | |

| f | Final | |

| h | Hay | |

| i | Initial | |

| p | Particle | |

| spl | Supply | |

| t | Transferred energy from air to hay | |

| w | Water |

References

- Sioshansi, F. Energy, Sustainability and the Environment: Technology, Incentives, Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wasewar, K.L.; Rao, S.N. Sustainable engineering, energy, and the environment. In Apple Academic Press eBooks; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chen, Z. Trends in environmental sustainability and green energy. In Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.R.; Chaudhry, H.N.; Ghani, S.A. A review of sustainable cooling technologies in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3112–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spentzou, E.; Cook, M.J.; Emmitt, S. Low-energy cooling and ventilation refurbishments for buildings in a Mediterranean climate. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 18, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydes, K.; Fosket, J. Sustainable heating ventilation and air conditioning. In Springer eBooks; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicker, U. Low Energy Cooling for Sustainable Buildings; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Asim, N.; Badiei, M.; Mohammad, M.; Razali, H.; Rajabi, A.; Haw, L.C.; Ghazali, M.J. Sustainability of heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems in buildings—An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabhi, K.; Ali, C.; Nciri, R.; Bacha, H.B. Novel design and simulation of a solar air-conditioning system with desiccant dehumidification and adsorption refrigeration. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2015, 40, 3379–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, C.; Attyaoui, S.; Nasri, F.; Bacha, H.B. Heat and mass transfer in a solar tunnel dryer: Modelling and simulation. Int. Rev. Mech. Eng. 2012, 6, 810–817. [Google Scholar]

- Dalei, N.N.; Gupta, A. Adoption of renewable energy to phase down fossil fuel energy consumption and mitigate territorial emissions: Evidence from BRICS group countries using panel FGLS and panel GEE models. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.F. Estimation of global solar energy to mitigate world energy and environmental vulnerability. In CRC Press eBooks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A global assessment: Can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.K.; Panigrahi, C.K. A state-of-the-art review of solar passive building systems for heating or cooling purposes. Front. Energy 2016, 10, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.; Knaack, U.; Auer, T.; Klein, T. COOLFACADE: State-of-the-art review and evaluation of solar cooling technologies on their potential for façade integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, R.; Lei, C. Solar chimney—A passive strategy for natural ventilation. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Elsaid, K.; Sayed, E.T.; Radwan, A.; Rezk, H.; Wilberforce, T.; Abo-Khalil, A.G.; Olabi, A. A review of solar chimney for natural ventilation of residential and non-residential buildings. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, N.; Baadi, A.; Ghedamsi, R.; Guerrout, A.; Settou, N. An experimental study and numerical simulation of natural ventilation in a semi-arid climate building using a wind catcher with evaporative cooling system and solar chimney. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 108475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.; Poshtiri, A.H.; Gilvaei, Z.M. Enhancing thermal comfort and natural ventilation in residential buildings: A design and assessment of an integrated system with horizontal windcatcher and evaporative cooling channels. Energy 2024, 289, 130040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Kalantar, V. Numerical simulation of natural ventilation with passive cooling by diagonal solar chimneys and windcatcher and water spray system in a hot and dry climate. Energy Build. 2021, 256, 111714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffouri, A.A.; Jubear, A.J. Numerical analysis of a passive ventilation system coupled with a hybrid cooling system. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 49, 2688–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.; Silveira, R.M.F.; Lensink, J.; Da Silva, I.J.O. Thermal performance of a low-profile cross-ventilated freestall dairy barn with evaporative cooling pads in a hot and humid climate. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, A.; Martínez, P.; Soto, V.M.; Martínez, P.J. Analysis of the performance of a passive downdraught evaporative cooling system driven by solar chimneys in a residential building by using an experimentally validated TRNSYS model. Energies 2021, 14, 3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, S. Fluid flow through packed columns. Chem. Eng. Prog. 1952, 48, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).