Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

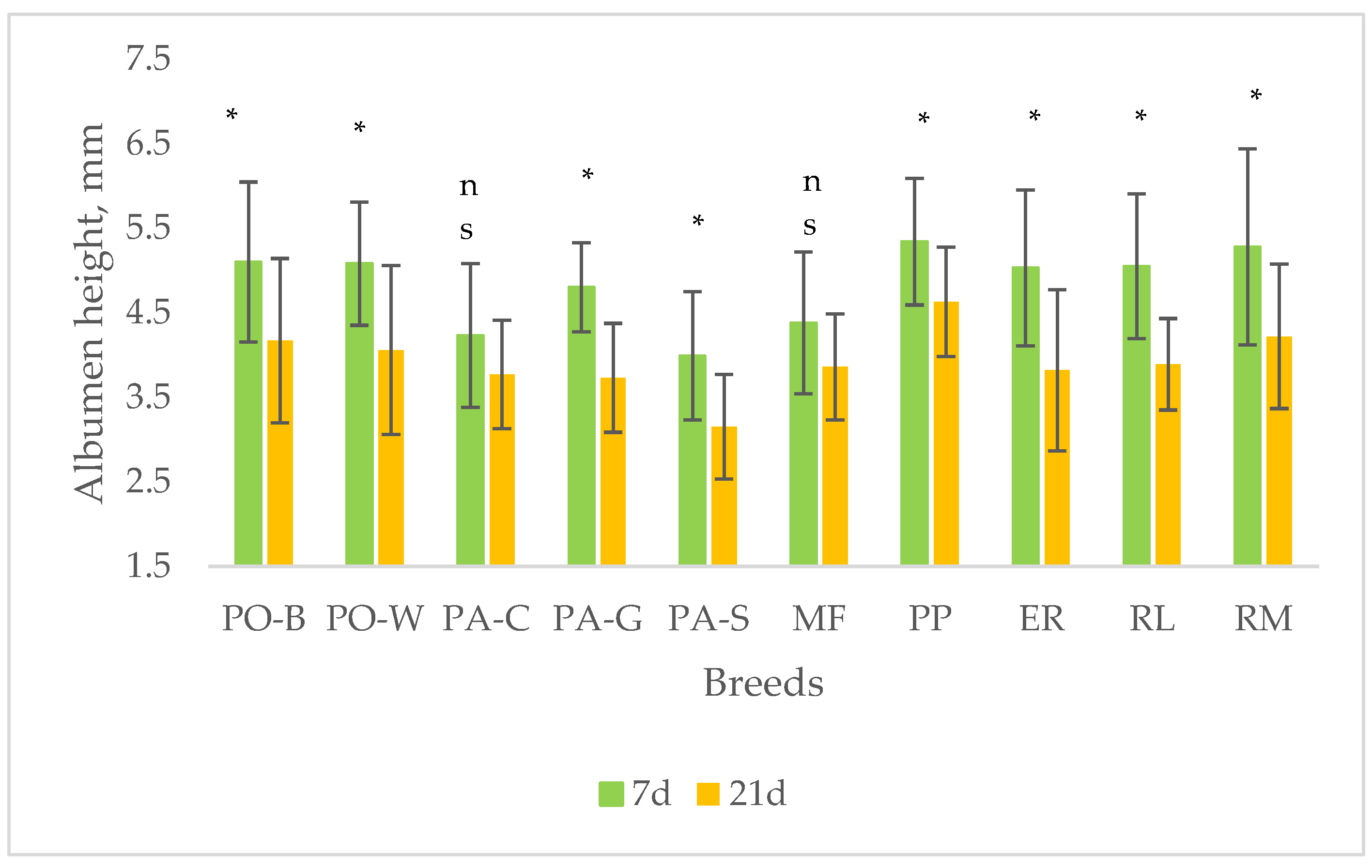

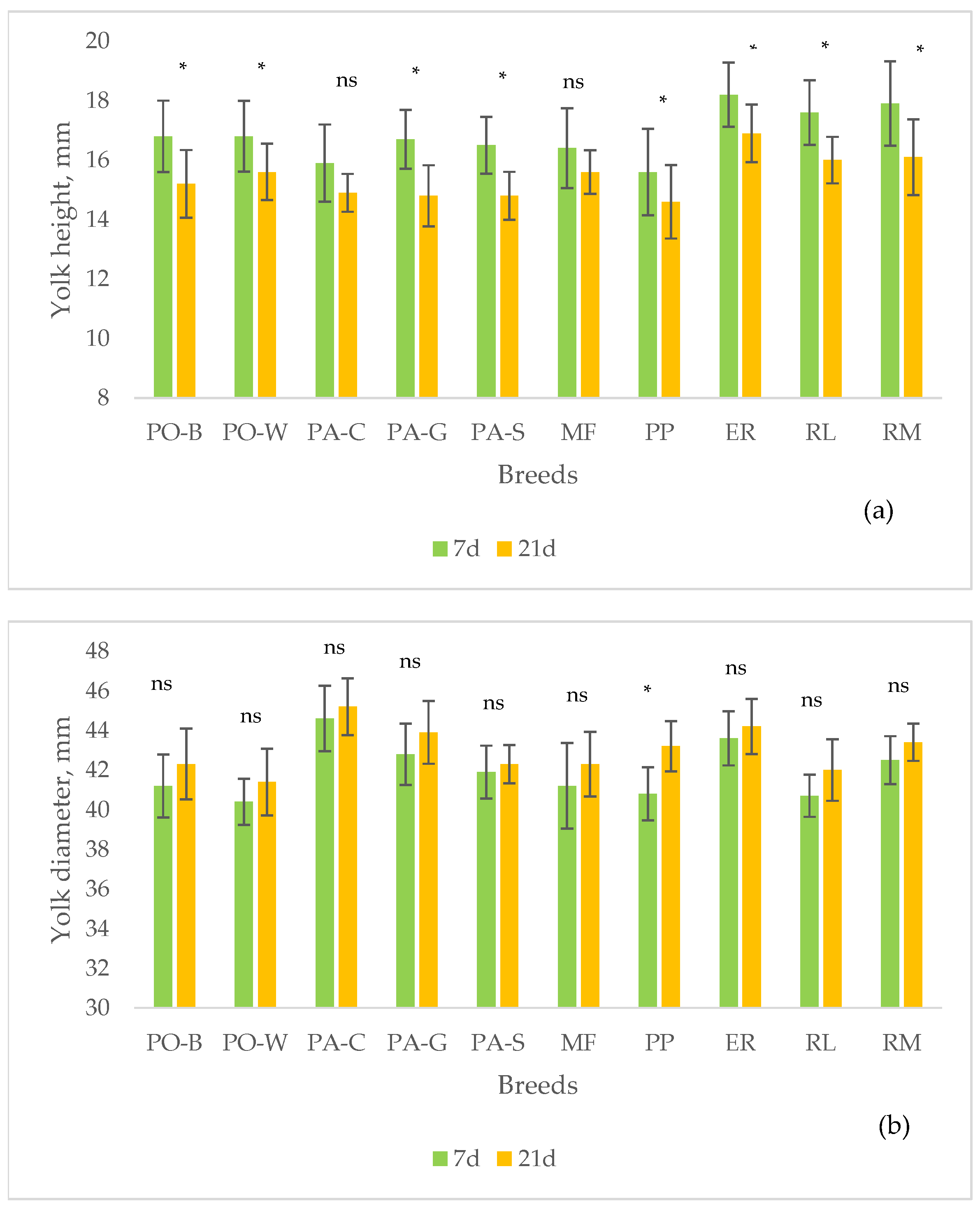

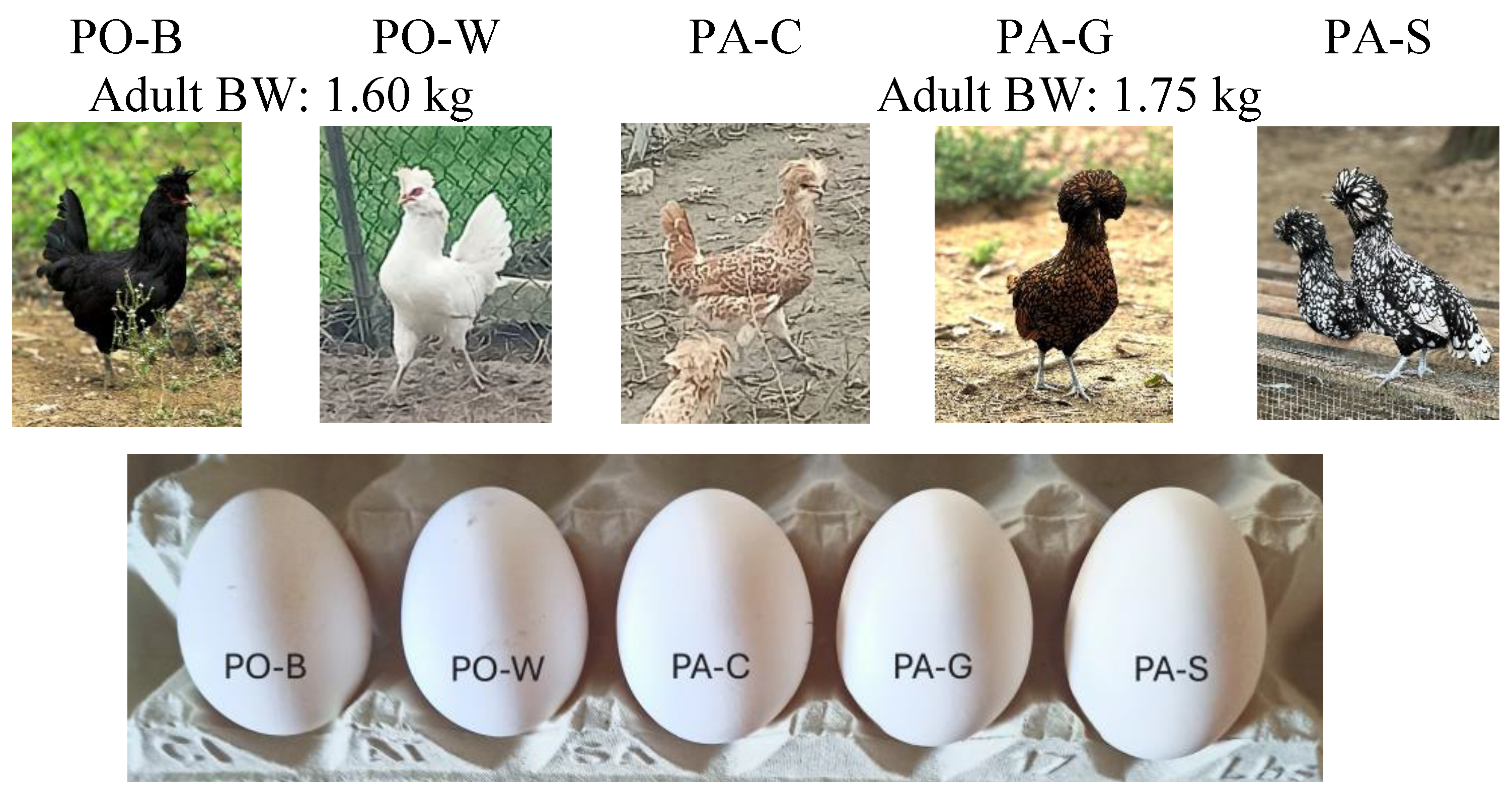

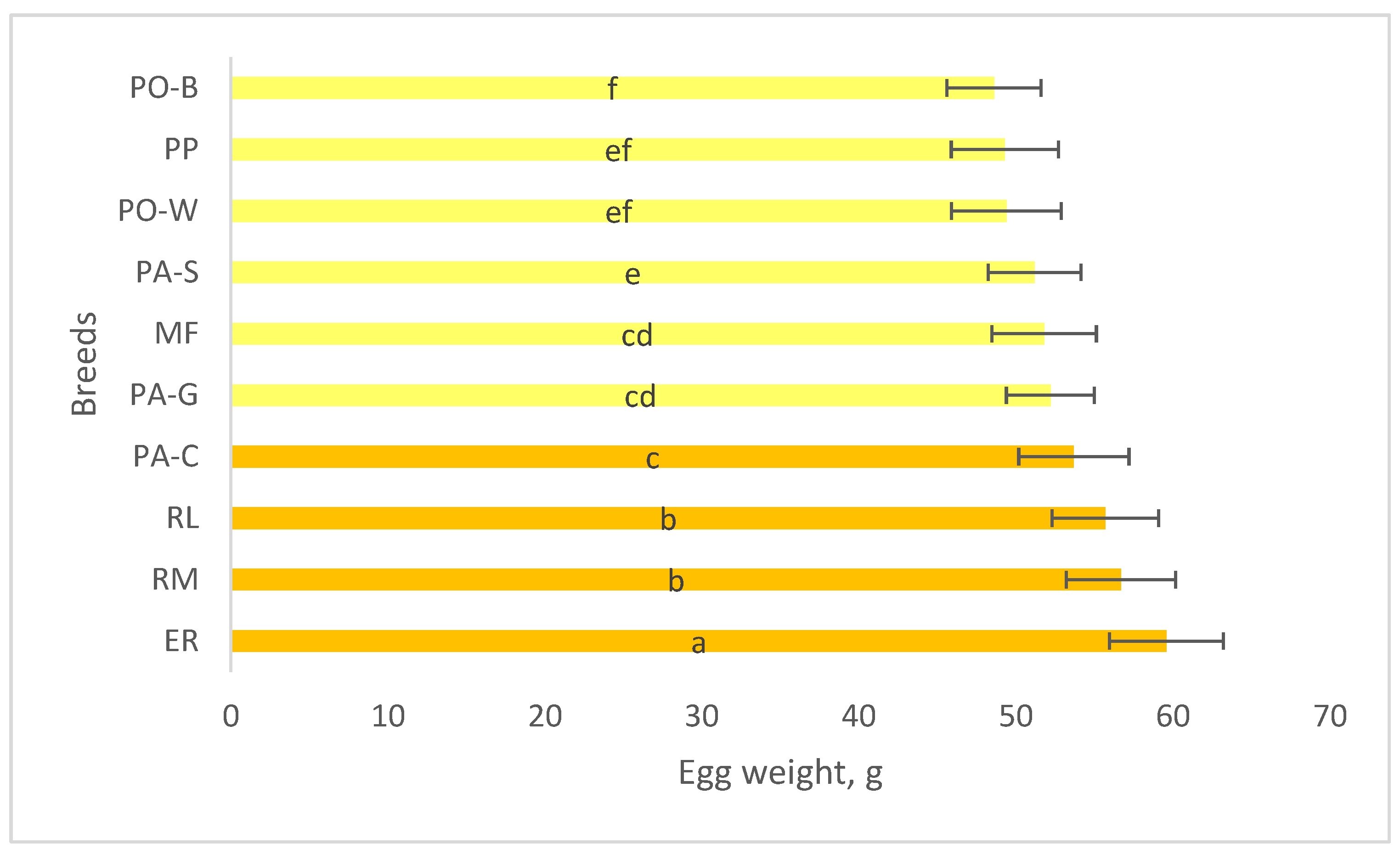

A trial was carried out to profile the quality of stored eggs, at 15 °C and 75% RH until to 21 d, of 10 Italian breeds of the Veneto region with different productive purpose (egg laying purpose: Polverara nera – PO-B, Polverara bianca – PO-W, Padovana camosciata – PA-C, Padovana dorata – PA-G, Padovana argentata – PA-S; dual-purpose: Millefiori di Lonigo – MF, Pepoi – PP, Ermellinata di Rovigo – ER, Robusta Lionata – RL, Robusta Maculata – RM. All the eggs were homogeneous for the hens age and rearing system (58week-old hens, outdoor rearing). The 1-d eggs showed differences (highest vs lowest, p < 0.05) for the egg weight (ER vs PO-B), and yolk to albumen ratio (PO-B vs RL). A factorial model, breed (10 breeds) x storage time (7 d and 21 d), was used for detecting the effect of breed, storage time and interaction on the eggshell traits and internal quality (weight loss rate, albumen and yolk quality). The effect of breed was significant (highest vs lowest, p < 0.05) for shape index (MF vs ER), eggshell lightness (PO-B, PO-W, PA-C, PA-G, PA-S vs RM), and eggshell thickness (PO-W, RM vs ER). The effect of storage was significant (p < 0.05) for all the internal quality traits. According to significant (p < 0.05) effect of breed, the highest weight loss rate was shown by RM and the lowest by PA-G. The highest Haugh units were shown by PP and the lowest by PA-S. The highest yolk index was shown by RL and the lowest by PA-C. From 7 until 21 d of storage, significant (p < 0.05) changes of the egg internal quality occurred according to the breed, as the thick albumen height and the yolk height decreased in all groups, with exception of PA-C and MF, probably for changes earlier than those of the other groups, whereas the yolk diameter did not change, with exception of PP. The results indicate that the natural decline of egg quality throughout storage varies differently between the breeds and more study is needed for understanding the changes of each egg component.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Rearing Conditions

2.2. Data Collection on Egg Quality

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sirri, F.; Zampiga, M.; Soglia, F.; Meluzzi, A.; Cavani, C.; Petracci, M. Quality characterization of eggs from Romagnola hens, an Italian local breed. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 4131–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordelo, M.; Cid, J.; Cordovil, C.M.D.S.; Alves, S.P.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Carolino, I. A comparison between the quality of eggs from indigenous chicken breeds and that from commercial layers. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianni, A.; Bartolini, D.; Bennato, F.; Martino, G. Egg quality from Nera Atriana, a local poultry breed of the Abruzzo region (Italy), and Isa Brown hens reared under free range conditions. Animals 2021, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiter, R.; Freick, M. Laying performance characteristics, egg quality, and integument condition of Saxonian chickens and German Langshan bantams in a free-range system. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, G.; Bell, d.; Weaver, W.D., Jr. Shell eggs and their nutritional value. In Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 1109–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Bao, M.; Yang, N.; Zhuo-Cheng, H.; Ning, Z. Traits of eggshell and shell membranes of translucent eggs. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasri, H.; Brand van den, H.; Najjar, T.; Bouzouaia, M. Egg storage and breeder age impact on egg quality and embryo development. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 104, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yimenu, S.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Koo, J.; Kim, B.S. Predictive modeling for monitoring egg freshness during variable temperature storage conditions. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Xue, H.; Xiong, C.; Li, J.; Tu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Effects of temperature on quality of preserved eggs during storage. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3144–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaziak, K.; Kieliszek, M.; Buclaw, M. Characterization of structure and protein of vitelline membranes of precocial (ring-necked pheasant, gray partridge) and superaltricial (cockatiel parrot, domestic pigeon) birds. PlosOne 2020, 15(1), e0228310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qiu, N.; Mine, Y.; Meng, Y.; Keast, R.; Zhu, Ch. Quantitative comparative proteomic analysis of chicken egg vitelline membrane proteins during high-temperature storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 9816–9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Qiu, N.; Mine, Y.; Keast, R.; Meng, Y. Comparative N-glycoproteomic analysis provides novel insights into the deterioration mechanisms in chicken egg vitelline membrane during high-temperature storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alig, B.N.; Malheiros, R.D.; Anderson, K.E. Evaluation of physical egg quality parameters of commercial brown laying hens housed in five production systems. Animals 2023, 13, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Song, J.; Xu, G.; Yang, N.; Zheng, J. Impact of cuticle quality and eggshell thickness on egg bacterial efficiency. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chousalkar, K.K.; Samiullah, K.; McWhorter, A.R. Microbial quality, safety and storage of eggs. Current Opinion in Food Science 2021, 38, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketta, M.; Tůmová, E. Eggshell structure, measurements, and quality-affecting factors in laying hens: a review. Czech. J Anim. Sci. 2016, 61, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ning, Z. Research progress on bird eggshell quality defects: a review. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirunda, D.F.K.; Mc Kee, S.R. Relating quality characteristic of aged eggs and fresh eggs to vitelline membrane strenght as determined by a texture analyzer. Poult. Sci. 2000, 79, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaziak, K.; Marzec, A.; Riedel, J.; Szeliga, J.; Koczywąs, E.; Cisneros, F.; Michalczuk, M.; Lukasiewicz, M.; Gozdowski, D.; Siennicka, A.; Kowalska, H.; Niemiec, J.; Lenart, A. Effect of dietary canthaxanthin and iodine on the production performance and egg quality of laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 4008–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlborn, G.; Sheldon, B.W. Enzymatic and microbiological inhibitory activity in eggshell membranes as influenced by layer strains and age and storage variables. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1935–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, C. Albumen quality of fresh and stored table eggs: hen genotype as a further chance for consumer choise. Animals 2021, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/dad-is/browse-by-country-and-species/en/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Cassandro, M.; Baruchello, M.; Catania, S.; Gobbo, F.; Moronato, M.L.; Baldan, G.; Carnio, D.; Parise, M.; Rizzi, C. Conservazione e Caratterizzazione Delle Razze Avicole Venete–Programma Bionet. Rete Regionale Per la Conservazione e Caratterizzazione Della Biodiversità di Interesse Agrario. In Gruppo di Lavoro Avicoli; Veneto Agricoltura: Legnaro, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Verdiglione, R.; Cassandro, M. Characterization of muscle fiber type in the pectoralis major muscle of slow-growing local and commercial chicken strains. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2433–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slow Food Presidia. Available online: https://slowfood.com/biodiversity-programs/presidia/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Mauldin, J.M.; Bell, d.; Weaver, W.D., Jr. Operating the hatchery. In Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 775–798. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 2023/2465 of 17 August 2023 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards marketing standards for eggs and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 589/2008. Official Journal of the European Union of 8.11.2023, L. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Narushin, V.G. Egg geometry calculation using the measurements of lenght and breath. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission International de l’Eclairage. CIELab Color System; CIE: Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Haugh, R.R. The Haugh unit for measuring egg quality. U.S. Egg Poult. Mag. 1937, 43, 552–555, 572–573. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.D.; Bell, d.; Weaver, W.D., Jr. Cage management for layers. In Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 1007–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Réhault-Godbert, S.; Guyot, N.; Nys, Y. The golden egg: nutritional value, bioactivities, and emerging benefits for human health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, C. A study on egg production and quality according to the age of four chicken dual-purpose purebred hens reared outdoors. Animals 2023, 13, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.D.; Bell, d.; Weaver, W.D., Jr. Egg production and egg weight standards for table-egg layers. In Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 1079–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Coon, C.; Bell, d.; Weaver, W.D., Jr. Feeding commercial egg-type layers. In Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 287–328. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, C. Plumage colour in Padovana chicken breed: growth performance and carcass quality. Italian J. Anim. Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, C.; Cendron, F.; Penasa, M.; Cassandro, M. Egg quality of Italian local chicken breeds: I. Yield performance and physical characteristics. Animals 2023, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiullah, S.; Omar, A.S.; Roberts, J.; Chousalkar, K. Effect of production system and flock age on eggshell and egg internal quality measurements. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P. Recent advances in avian egg science: A review. Poult. Sci. 2017, 0, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, G.; Portugal, S.J.; Hauber, M.E.; Mikšík, I.; Russell, D.G.D.; Cassey, P. First light for avian embryos: eggshell thickness and pigmentation mediate variation in development and UV exposure in wild bird eggs. Functional Ecology 2015, 29, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell Stoddard, M.; Yong, E.H.; Akkayanak, D.; Sheard, C.; Tobias, J.A.; Mahadevan, L. Avian egg shape: Form, function, and evolution. Science 2017, 356, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincke, M.T. The eggshell: structure, composition and mineralization. J. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Reyes, C.; Folegatti, E.; Domingues-Gasca, N.; Litta, G.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Rodriguez-Navarro, A.B.; Faruk, M.U. Research note: Changes in eggshell quality and microstructure related to hen age during a productive cycle. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, A.; Damaziak, K.; Kowalska, H.; Riedel., J.; Michalczuk, M.; Koczywąs, E.; Cisneros, F.; Lenart, A.; Niemiec, J. Effect of hens age and storage time on functional and physiochemical properties of eggs. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2019, 28, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbar, V.; Nedomova, S.; Trnka, J.; Buchar, J.; Pytel, R. Effect of storage duration on the rheological properties of goose liquid egg products and eggshell membranes. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 1693–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, A.; Michalczuk, M.; Damaziak, K.; Mieszkowska, A.; Lenart, A.; Niemiec, J. Correlations between vitelline membrane strenght and selected physical parameters of poultry eggs. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2016, 3, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasenko, G.M.; Robinson, F.E.; Hardin, R.T.; Wilson, J.L. Variability in preincubation embryonic development in domestic fowl. 2. Effects of duration of egg storage period. Poult. Sci. 1992, 71, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PO-B | PO-W | PA-C | PA-G | PA-S | MF | PP | ER | RL | RM | p | RMSE | |

| Yolk weight, g | 16.8 de | 16.1 e | 18.7 ab | 17.3 cd | 17.2 cde | 16.4 de | 14.8 f | 17.9 bc | 17.3 cd | 19.0 a | < 0.0001 | 1.41 |

| Albumen weight, g | 27.9 d | 28.4 cd | 31.3 b | 30.1 bc | 28.7 bcd | 29.4 bcd | 28.2 cd | 34.9 a | 35.2 a | 33.6 a | < 0.0001 | 2.72 |

| Yolk/albumen, g/g | 0.604 a | 0.568 ab | 0.596 ab | 0.578 ab | 0.601 ab | 0.565 abc | 0.529 bc | 0.518 cd | 0.493 d | 0.572 ab | < 0.0001 | 0.05 |

| PO-B | PO-W | PA-C | PA-G | PA-S | MF | PP | ER | RL | RM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape index, % | 74.2 de | 76.4 bc | 75.6 bcd | 76.9 b | 74.1 de | 80.8 a | 75.5 bcd | 73.5 e | 74.8 cde | 77.3 b |

| Surface area/volume, cm2/cm3 | 1.36 a | 1.35 a | 1.31 bc | 1.32 b | 1.33 b | 1.32 b | 1.35 a | 1.27 e | 1.29 cd | 1.28 de |

| L | 92.1 a | 92.5 a | 92.8 a | 93.2 a | 92.1 a | 86.8 b | 84.5 c | 79.7 d | 83.0 c | 72.3 e |

| a* | -5.30 e | -5.09 e | -5.13 e | -5.25 e | -4.77 e | -1.86 d | -1.78 d | 2.29 b | 0.22 c | 6.86 a |

| b* | 8.15d | 7.95 d | 7.12 d | 7.44 d | 9.00 d | 14.7 c | 19.2 b | 22.0 a | 18.3 b | 23.8 a |

| Thickness, µm | 344 ab | 359 a | 340 ab | 332 bcd | 319 cd | 336 bc | 339 b | 315 d | 335 bc | 359 a |

| B | S | BxS | p | RMSE | B | S | BxS | p | RMSE | ||

| Shape index | < 0.0001 | 0.09 | 0.33 | < 0.0001 | 2.75 | Albumen height | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.2187 | < 0.0001 | 0.80 |

| Area/volume | < 0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.11 | < 0.0001 | 0.03 | Yolk height | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.2307 | < 0.0001 | 1.09 |

| L | < 0.0001 | 0.30 | 0.44 | < 0.0001 | 3.03 | Yolk diameter | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0386 | < 0.0001 | 1.47 |

| a* | < 0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.97 | < 0.0001 | 2.86 | Egg weight loss | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0550 | < 0.0001 | 0.47 |

| b* | < 0.0001 | 0.25 | 0.89 | < 0.0001 | 3.62 | Haugh units | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.2486 | < 0.0001 | 7.97 |

| Thickness | < 0.0001 | 0.22 | 0.31 | < 0.0001 | 27.8 | Yolk index | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.5248 | < 0.0001 | 0.03 |

| PO-B | PO-W | PA-C | PA-G | PA-S | MF | PP | ER | RL | RM | |

| Weight loss rate, % | 1.42 bc | 1.31 bcd | 1.19 dc | 1.10 d | 1.39 bc | 1.52 b | 1.32 bcd | 1.45 bc | 1.55 b | 1.96 a |

| 7 d | 1.02 ab | 0.837 ab | 0.604 b | 0.656 b | 0.816 ab | 1.02 ab | 0.860 ab | 0.986 ab | 0.977 ab | 1.21 a |

| 21 d | 1.83 bc | 1.79 bc | 1.77 bc | 1.55 bc | 1.96 bc | 2.01 bc | 1.78 bc | 1.92 c | 2.12 bc | 2.71 a |

| Haugh units | 69.3 ab | 68.2 abc | 60.9 de | 64.2 cd | 57.7 e | 63.6 cd | 72.8 a | 61.4 de | 64.2 cd | 66.6 bcd |

| 7 d | 73.7 ab | 73.2 ab | 63.6 c | 70.0 abc | 61.9 c | 66.0 bc | 75.4 a | 67.9 abc | 69.7 abc | 70.8 abc |

| 21 d | 65.4 ab | 63.8 ab | 58.7 bc | 59.5 bc | 54.1 c | 61.1 bc | 70.1 a | 55.7 c | 59.7 bc | 62.9 abc |

| 7 vs 21d | * | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | * | * | ns |

| Yolk index | 0.383 bc | 0.395 ab | 0.343 e | 0.361 d | 0.371 cd | 0.384 bc | 0.359 de | 0.399 ab | 0.405 a | 0.395 ab |

| 7 d | 0.409 ab | 0.417 ab | 0.359 d | 0.390 bc | 0.394 bc | 0.399 bc | 0.380 cd | 0.418 ab | 0.432 a | 0.421 ab |

| 21 d | 0.360 abcd | 0.376 ab | 0.330 e | 0.337 de | 0.351 bcde | 0.369 abc | 0.339 cde | 0.382 a | 0.382 a | 0.372 abc |

| 7 vs 21d | * | * | ns | * | * | ns | * | * | * | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).