1. Introduction

Eggs are highly nutritious but naturally perishable foods whose quality begins to deteriorate shortly after they are laid. This deterioration is primarily due to the loss of moisture and carbon dioxide through the porous eggshell [

1,

2], resulting in increased albumen pH, weakening of the yolk membrane and thinning of the thick albumen. These physicochemical changes impair both the nutritional and functional properties of the egg [

3,

4].

Ensuring the microbiological safety and quality of eggs requires a careful balance between effective preservation techniques and various legal, economic and practical constraints. Refrigeration is a common method of slowing down microbial and physico-chemical degradation and thus extending the shelf life of eggs. However, its widespread use may be limited due to high energy requirements and high operating costs, especially in rural areas or where resources are limited. In the European Union, refrigeration of eggs at retail level is not mandatory. According to Commission Regulation (EC) No 589/2008, eggs are usually stored at room temperature to prevent surface condensation, which could otherwise favor the growth of microorganisms on the eggshell.

In addition to storage considerations, there are also significant limitations to current egg decontamination procedures. In countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and Japan, eggs are routinely washed with water and sanitizers during industrial processing to reduce microbial contamination [

5]. While this practice effectively removes surface contaminants, it can affect the natural cuticle of the eggshell, increasing susceptibility to moisture loss and microbial ingress. In contrast, the European Union prohibits the washing of Grade A eggs and emphasizes the importance of preserving the natural cuticle as a critical barrier to contamination [

6]. Thermal pasteurization methods are unsuitable for whole eggs as the temperatures required to inactivate pathogens would lead to coagulation of the egg contents [

7]. Non-thermal alternatives such as electron irradiation have demonstrated their potential; however, higher doses can cause undesirable changes such as loss of flavor and oxidative degradation [

8].

Given these limitations, current research is increasingly focused on the development of edible surface coatings as a cost-effective and energy-efficient method of preserving the quality and safety of eggs during storage and distribution. Such coatings based on proteins, lipids, polysaccharides or combinations thereof can reduce moisture loss, limit gas exchange, increase microbial safety and help maintain albumen viscosity and internal quality parameters such as Haugh units [

5,

9,

10,

11]. While mineral oils have long been used for this purpose, more recent studies have investigated the preservative potential of various vegetable oils, including flaxseed [

9], peanut, cottonseed, coconut [

12], rapeseed, corn, grapeseed, olive, soybean and sunflower oils [

13]. Another promising natural coating material is propolis - a resinous substance collected by bees and known for its antifungal, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of propolis extracts in extending the shelf life of eggs, suggesting their potential as a natural and bioactive alternative to synthetic coatings [

18,

19].

Despite these advances, most existing studies have focused on a single poultry species, a single type of coating or a narrow range of storage conditions. Comparative data on different coating types and poultry species remain limited. The present study fills these gaps by systematically investigating the effects of three surface coatings - propolis, olive oil and paraffin oil - on the preservation of hen eggs and Japanese quail eggs stored both at room temperature and under refrigerated conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 750 hen eggs (

Gallus gallus domesticus) and 750 Japanese quail eggs (

Coturnix coturnix japonica) were included in the analysis. The hens were 52 weeks old and kept in a floor housing system with ad libitum access to drinking water and a complete feed mixture formulated for laying hens (16.2% CP; 11.3 MJ ME/kg). There was a 24-hour light regime consisting of 14 hours of light and 10 hours of darkness. The quails were 28 weeks old and were housed as part of a breeding flock in group cages with a male to female ratio of 1:3–5. They had unrestricted access to drinking water and a complete laying quail diet (19.0% CP; 11.9 MJ ME/kg) with a lighting schedule of 17 hours of light and 7 hours of darkness. The hen and quail eggs were collected within 12 hours of laying. All eggs (hen and quail eggs) were randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups: control (uncoated; 210 eggs), coated with propolis (180 eggs), coated with paraffin oil (180 eggs) and coated with olive oil (180 eggs). Each group was further divided into subgroups of 15 eggs, which were individually numbered, weighed and analysed (

Table 1).

Eggs coated with propolis were sprayed with a 7% ethanolic propolis solution with added niacin (Medex, Ljubljana, Slovenia), ensuring complete coverage on both sides before air-drying. Eggs coated with paraffin oil were dipped in food-grade paraffin oil (Samson, Kamnik, Slovenia). Eggs coated with olive oil were dipped in a mixture of 80 % refined olive oil and 20 % extra virgin olive oil with 2 % added vitamin E (Gea, Slovenska Bistrica, Slovenia), while the control eggs were not coated. Both hen and quail eggs were stored under two controlled environmental conditions: at room temperature (22.0 °C, 65.0 % relative humidity) and in a cold room (12.0 °C, 80.0 % relative humidity). The entire experiment was carried out over a period of 56 days. The eggs were analyzed weekly until the 28th day of storage and every two weeks thereafter (

Table 1).

Each egg was weighed individually using an electronic scale, and its width and length were measured using a digital caliper. The shape index was calculated using the following formula: Shape Index = (egg width / egg length) × 100. The volume (V) and surface area (S) of hen eggs were calculated according to the equations proposed by [

20]:

where EW is the egg width, EL is the egg length.

For quail eggs, the volume (V) and surface area (S) were determined using the formulas described by [

21]:

where EW is the egg width, EL is the egg length and EWt is the egg weight.

The Haugh units (HU) were calculated using the equation developed by Haugh [

22]:

where H is the height of the thick albumen and EWt is the egg weight.

Eggshell strength was measured using a universal testing machine (Instron 3345, Instron Corporation, Norwood, MA, USA). After measuring the shell strength, the cracked eggs were opened on a flat glass surface and the yolk diameter was measured with a digital caliper. Other egg quality parameters were assessed using a range of specialized electronic equipment developed by Technical Services and Supplies Ltd (Dunnington, York, UK). These included a reflectometer for eggshell color, a tripod micrometer for thick albumen height, a colorimeter for yolk color and a microprocessor with an integrated computer. Egg albumen and yolk were separated into individual plastic tubes and their pH values were measured with a calibrated pH meter (S47-K SevenMulti pH/CON, Mettler Toledo International Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland). After each measurement, the electrode of the pH meter was rinsed with distilled water and dried. The yolk color of quail eggs was not evaluated because the small size of the yolks prevents reliable measurement by colorimetry; likewise, the shell color could not be determined by reflectometry due to the mottled and uneven pigmentation of the eggshell.

For the statistical analysis, the data was prepared using Microsoft Excel in the Windows environment and then analyzed using the SAS statistical package [

23]. The UNIVARIATE procedure was used to test the normality of the data distribution. Normality was assessed by graphical inspection (histograms), two statistical tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk) and by assessing skewness and kurtosis. The GLM (General Linear Models) method was used to analyze the data according to the following statistical model:

where:

yijkl = observed characteristic (e.g. egg width, albumen pH, yolk diameter, etc.)

μ = total mean value

Ai = influence of storage temperature (room temperature, cold storage)

Bj = influence of the treatment group (control, olive oil, paraffin oil, propolis)

Ck = influence of the storage period of the eggs (7, 14, 21, 28, 42, 56 days)

ABij, BCjk, ACik = two-way interactions

eijkl = random error term

Differences between groups were assessed using the Tukey post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Storage Conditions on the Quality Characteristics of Hen and Quail Eggs

Table 2 and

Table 3 provide a comparative overview of the external and internal quality characteristics of hen eggs (

Table 2) and quail eggs (

Table 3) stored for 56 days under two different environmental conditions — cold storage and room temperature.

Storage temperature had no significant effect (p > 0.05) on the external morphological characteristics - such as width, length, shape index, surface area and volume - of hen and quail eggs (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

However, the internal quality parameters of both species were clearly influenced by the storage conditions. Eggs stored at room temperature showed significantly (p < 0.05) larger yolk diameters, higher albumen and yolk pH, lower albumen height and lower HU, all indicating an accelerated deterioration of albumen quality at higher temperatures. A species-specific difference was found in the strength of the eggshell: Hen eggs stored at room temperature had significantly (p < 0.05) higher shell strength than eggs stored at refrigeration temperature (

Table 2), while no such difference was found in quail eggs (

Table 3).

These results suggest that the internal quality of eggs is more susceptible to temperature-induced deterioration than the external characteristics and that there may be species-specific responses to storage conditions, particularly in shell strength (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.2. Influence of Surface Coating on the Quality Characteristics of Hen and Quail Eggs

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the comparative effects of four different surface coatings — control (uncoated), olive oil, paraffin oil and propolis — on various external and internal quality parameters of hen (

Table 4) and quail (

Table 5) eggs.

The external morphological parameters including egg size, surface area and volume of both hen and quail eggs were not significantly affected by the application of surface coatings (p > 0.05) (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

In contrast, significant and consistent effects on the internal quality of the eggs were observed. In both species, eggs treated with paraffin and olive oil retained significantly (p < 0.05) more weight during storage than uncoated and propolis-coated eggs. Among the coatings, paraffin oil was the most effective for maintaining internal quality, as it had the highest values for thick albumen height and HU (p < 0.05), followed by olive oil, while uncoated eggs had the poorest internal quality indicators. Yolk diameter was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by all coatings, with the greatest reduction observed in the olive oil treatment. Conversely, uncoated eggs had the largest yolk diameters, indicating a greater deterioration. Species-specific differences were only observed in the parameters of hen eggs. Propolis treatment significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the intensity of shell color, while it significantly (p < 0.05) improved the color of the yolk compared to the control (

Table 4). The shell strength remained unaffected by the coating treatment in both species (

Table 4 and

Table 5).

The results confirm that surface coatings, especially paraffin and olive oil, can effectively mitigate internal quality loss during egg storage, with additional pigment-related effects observed in propolis-treated hen eggs.

3.3. Temporal Changes in the Quality Characteristics of the Eggs During Storage

Table 6 and

Table 7 show the changes in the most important quality parameters of hen (

Table 6) and quail (

Table 7) eggs during a storage period of 7, 14, 21, 28, 42 and 56 days.

The external morphological characteristics - width, height, shape index, surface area and volume - remained stable in both hen and quail eggs throughout the storage period, with no statistically significant changes observed over time (p > 0.05) (

Table 6 and

Table 7).

Shell strength also did not follow a consistent trend, although slight fluctuations were observed in hen eggs at certain time points (

Table 6).

In contrast, internal egg quality was significantly (p < 0.05) influenced by the duration of storage in both species. A significant (p < 0.05) decrease in egg weight was observed in hen eggs from day 42 and in quail eggs from day 56. The yolk diameter increased progressively in both species, indicating a weakening and flattening of the yolk membrane.

The pH values of albumen and yolk increased significantly over time in both hens and quails (p < 0.05), indicating ongoing biochemical changes. Thick albumen height, an important indicator of freshness, decreased continuously during storage, with a significant decrease in hen eggs from day 14 (

Table 6) and in quail eggs from day 42 (

Table 7).

In summary, the external characteristics of the eggs remained largely unaffected by storage duration, while the internal quality deteriorated significantly over time in both species (p < 0.05), with overall similar trends observed, albeit with some species-specific differences in the onset and extent of changes.

3.4. Interaction Between Treatment and Storage Conditions

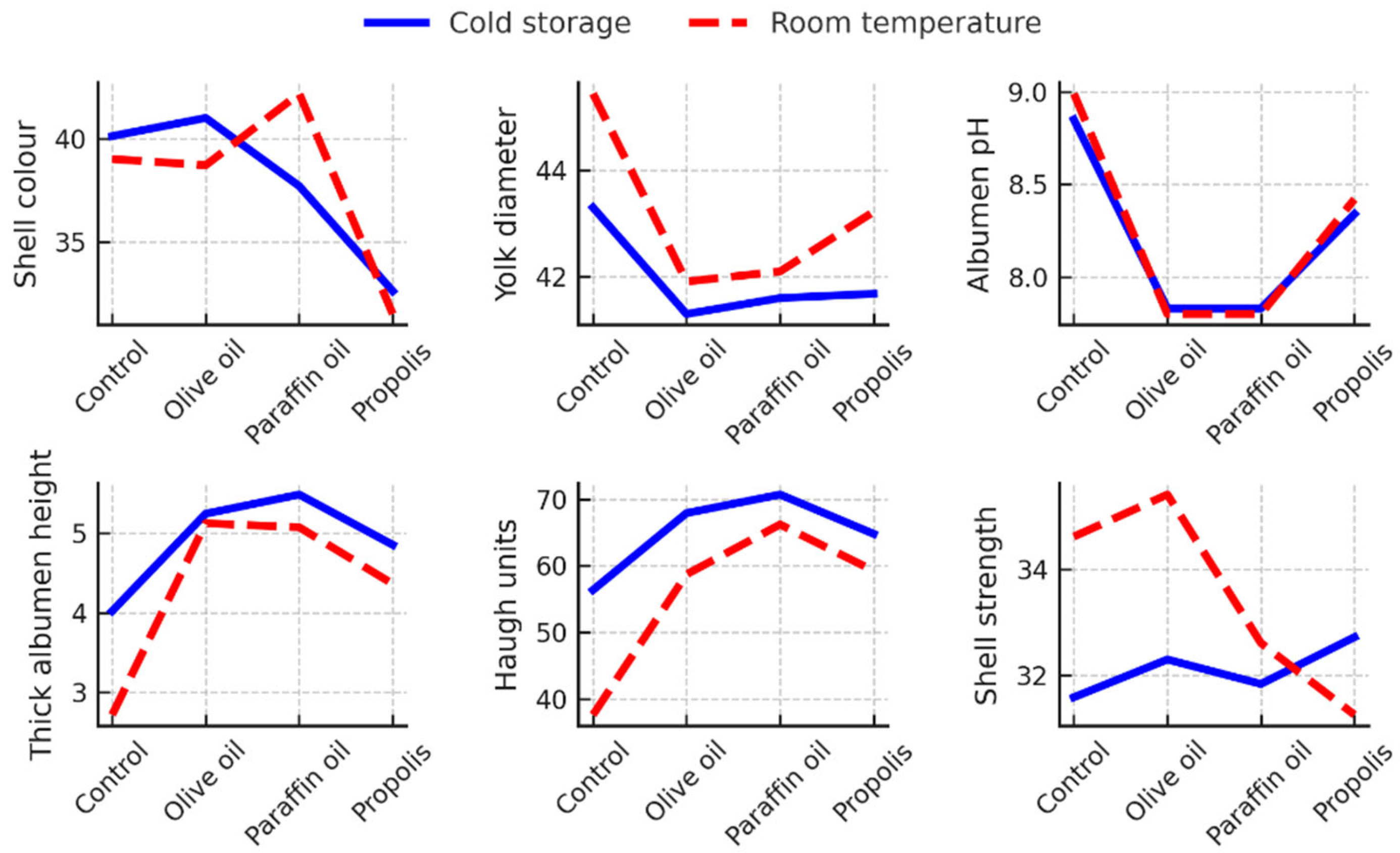

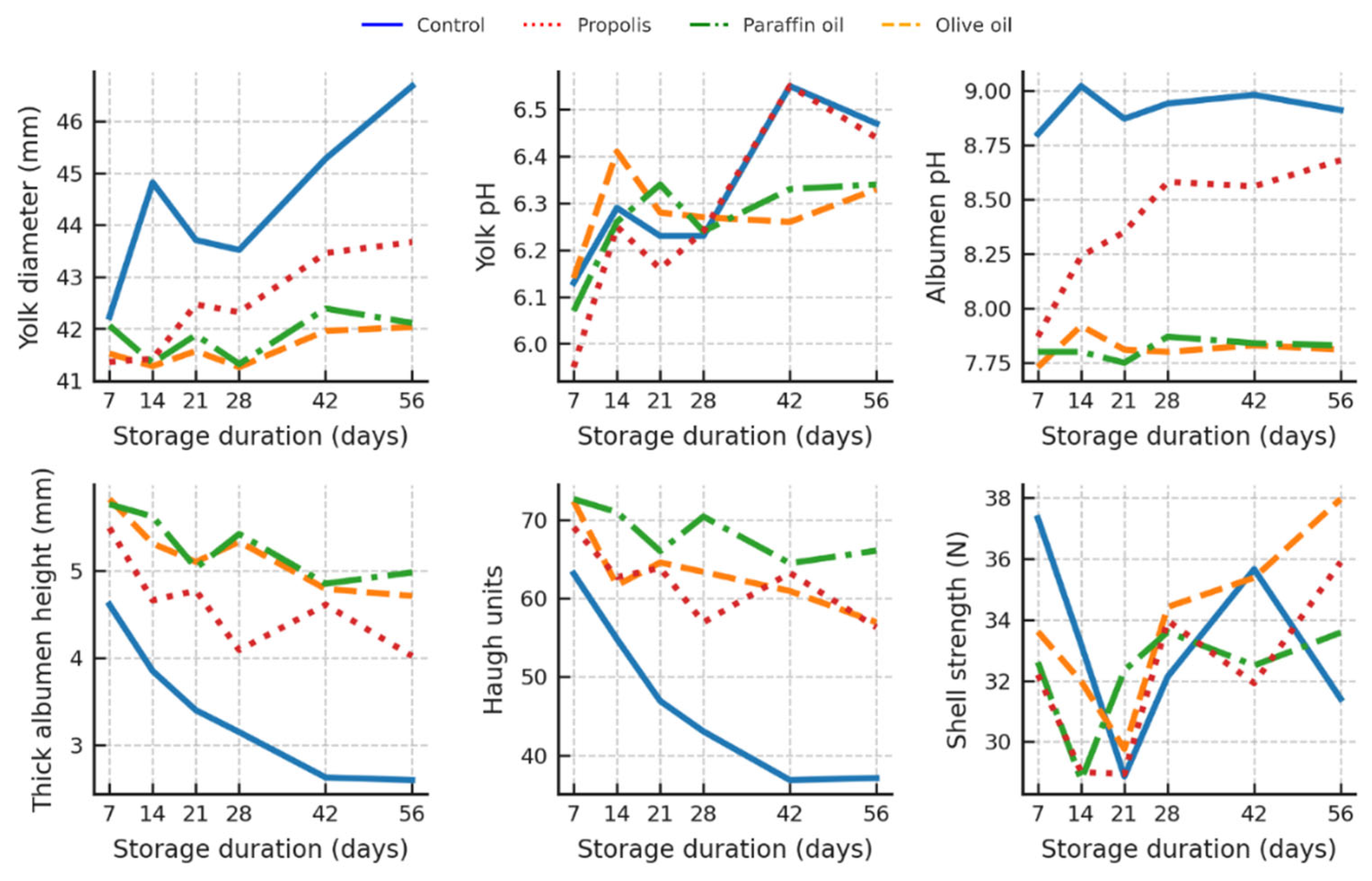

The interaction analysis between the experimental treatment and the storage conditions revealed several significant effects (p < 0.05) on the characteristics of both the hen eggs (

Figure 1) and the quail eggs (

Figure 2), but particularly in the hen eggs, where the internal quality parameters were most affected.

The most pronounced interactions were observed for albumen pH, thick albumen height and HU values.

Hen eggs from the uncoated control group stored at room temperature had the poorest internal quality, with the highest albumen pH (8.99), the lowest thick albumen height (2.72 mm) and the lowest HU (37.63). In contrast, paraffin-coated eggs showed better preservation of albumen quality, with HU reaching up to 70.66 and thick albumen height up to 5.48 mm under refrigerated storage (Figure 1).

A significant interaction (p < 0.05) was also found for yolk diameter. This parameter increased during storage at room temperature, especially in uncoated and propolis-coated eggs. Conversely, eggs coated with olive or paraffin oil maintained consistently smaller yolk diameters regardless of storage conditions, indicating better structural stability.

Significant interactions (p < 0.05) were also observed for shell color and strength (Figure 1). The propolis coating led to a visible darkening of the shell, probably due to interactions between the dark propolis pigments and the natural shell color. While the differences in shell strength were generally small, uncoated and olive oil-coated hen eggs stored at room temperature had statistically significantly (p<0.05) higher shell strength than propolis-coated eggs, although no such difference was observed compared to paraffin-coated eggs (Figure 1).

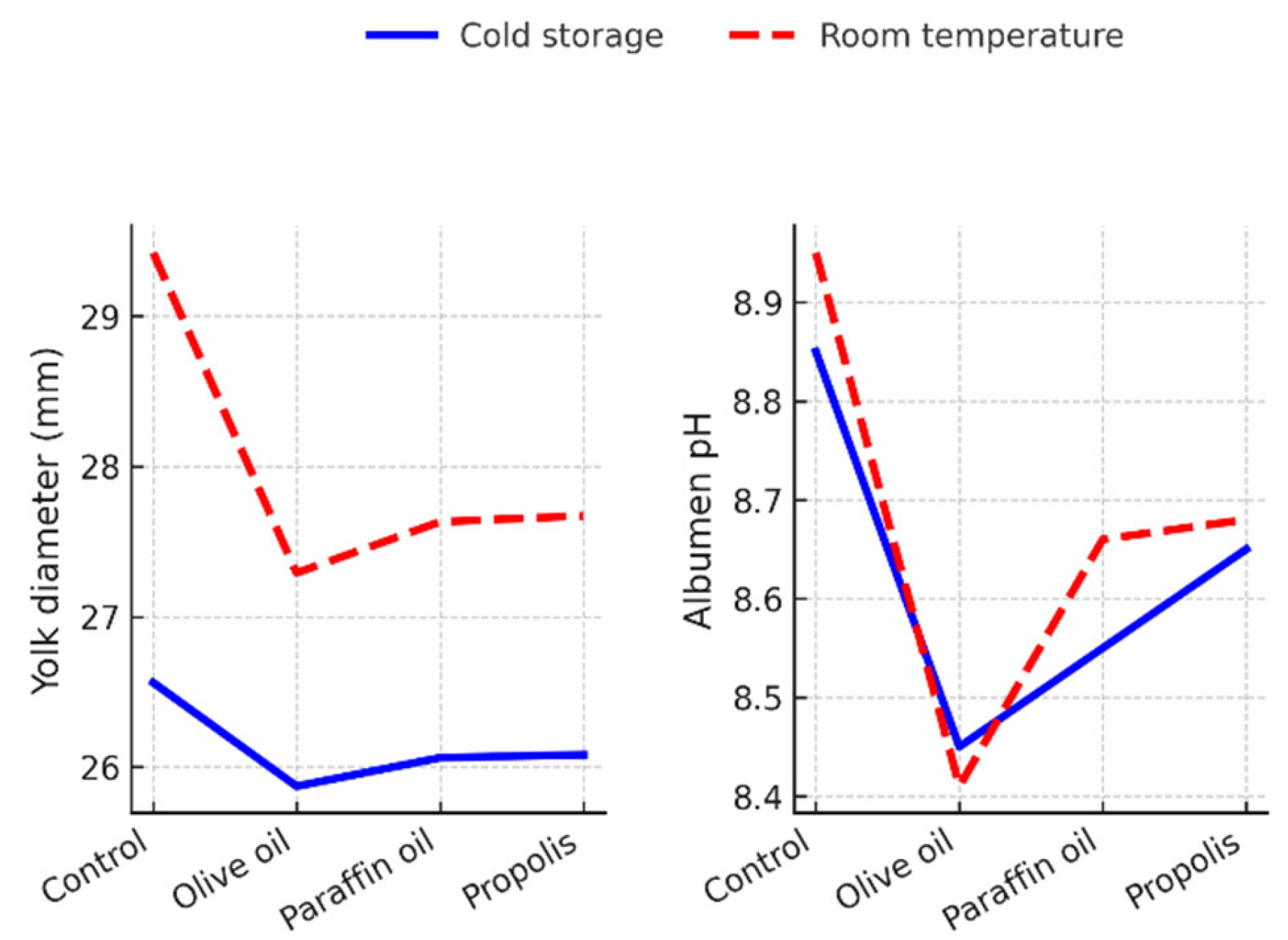

In quail eggs, statistically significant interactions (p < 0.05) were found between treatment and storage conditions for yolk diameter and albumen pH (Figure 2).

Storage at room temperature led to an increase in yolk diameter in all treatments, with the effect being most pronounced in the uncoated control group (29.42 mm). Albumen pH increased significantly (p < 0.05) during room temperature storage in the control group and in the paraffin-coated group, while pH remained relatively stable in the propolis- and olive oil-coated eggs, indicating better resistance to biochemical changes in different storage conditions (Figure 2).

These results confirm that the coating materials and storage temperature interact in complex ways to influence egg quality, with paraffin oil providing the most effective protection of internal parameters in both species.

3.5. Interaction Between Storage Duration and Storage Conditions

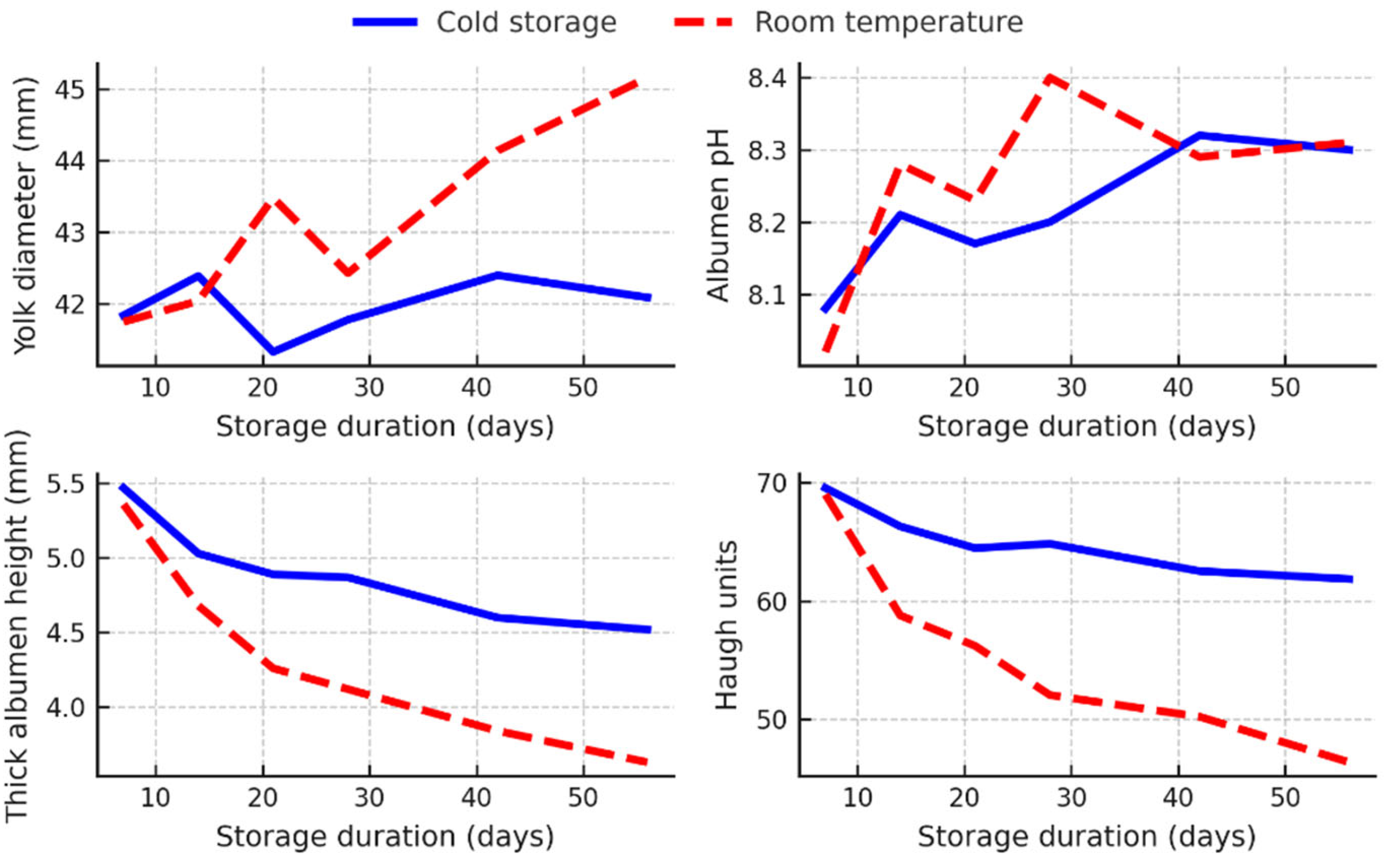

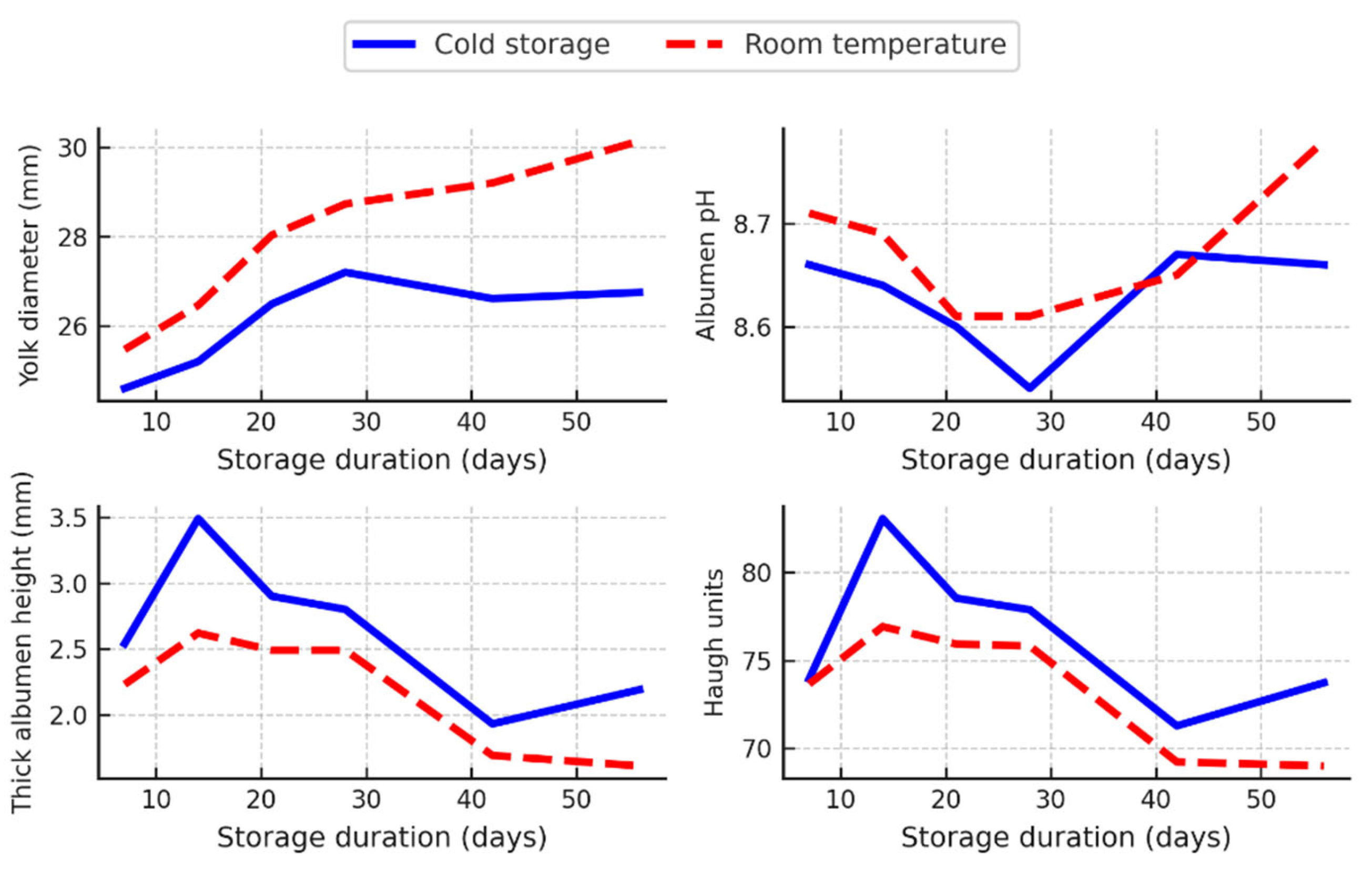

The interaction analysis of storage duration and storage conditions revealed significant effects on the internal quality characteristics of both hen eggs (

Figure 3) and quail eggs (

Figure 4), especially when the storage duration was extended beyond 14 days.

In hen eggs, the yolk diameter increased significantly (p < 0.05) on days 42 and 56 of storage under room temperature conditions, whereas no statistically significant (p > 0.05) changes were observed across storage durations in cold-stored eggs (

Figure 3). Albumen pH showed a general upward trend over time in both storage environments, with a slight acceleration at room temperature on day 28. However, these pH changes were generally small and often not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The height of the thick albumen decreased significantly more in eggs stored at room temperature. On day 56, hen eggs stored at room temperature had a significantly lower thick albumen height (3.63 mm) than cold-stored eggs (4.52 mm) (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3). This decrease in albumen quality was reflected in the HU values, which decreased from approximately 69 on day 7 to 46.36 on day 56 at room temperature, whereas the values for refrigerated eggs remained above 60 throughout the storage period (

Figure 3).

Similar interactions between storage time and temperature were also observed in quail eggs, with significant effects (p < 0.05) on yolk diameter, albumen pH, thick albumen height and HU (

Figure 4). Yolk diameter was significantly (p < 0.05) larger in room-stored quail eggs at all time points, with the most significant difference observed at day 56 (30.14 mm vs. 26.75 mm). The pH of the albumen gradually increased, with a significant difference (p < 0.05) observed on day 56 between room-stored (pH 8.78) and cold-stored eggs (pH 8.66). The decrease in albumen height was more abrupt in room-stored eggs, decreasing from 2.23 mm on day 7 to 1.61 mm on day 56, with a corresponding decrease in HU from 73.65 to 68.99 over the same period (

Figure 4).

These results show that prolonged storage, especially at room temperature, leads to a measurable deterioration in the internal quality of eggs in both hens and quails, with more pronounced and rapid changes in albumen structure and functional indices such as HU.

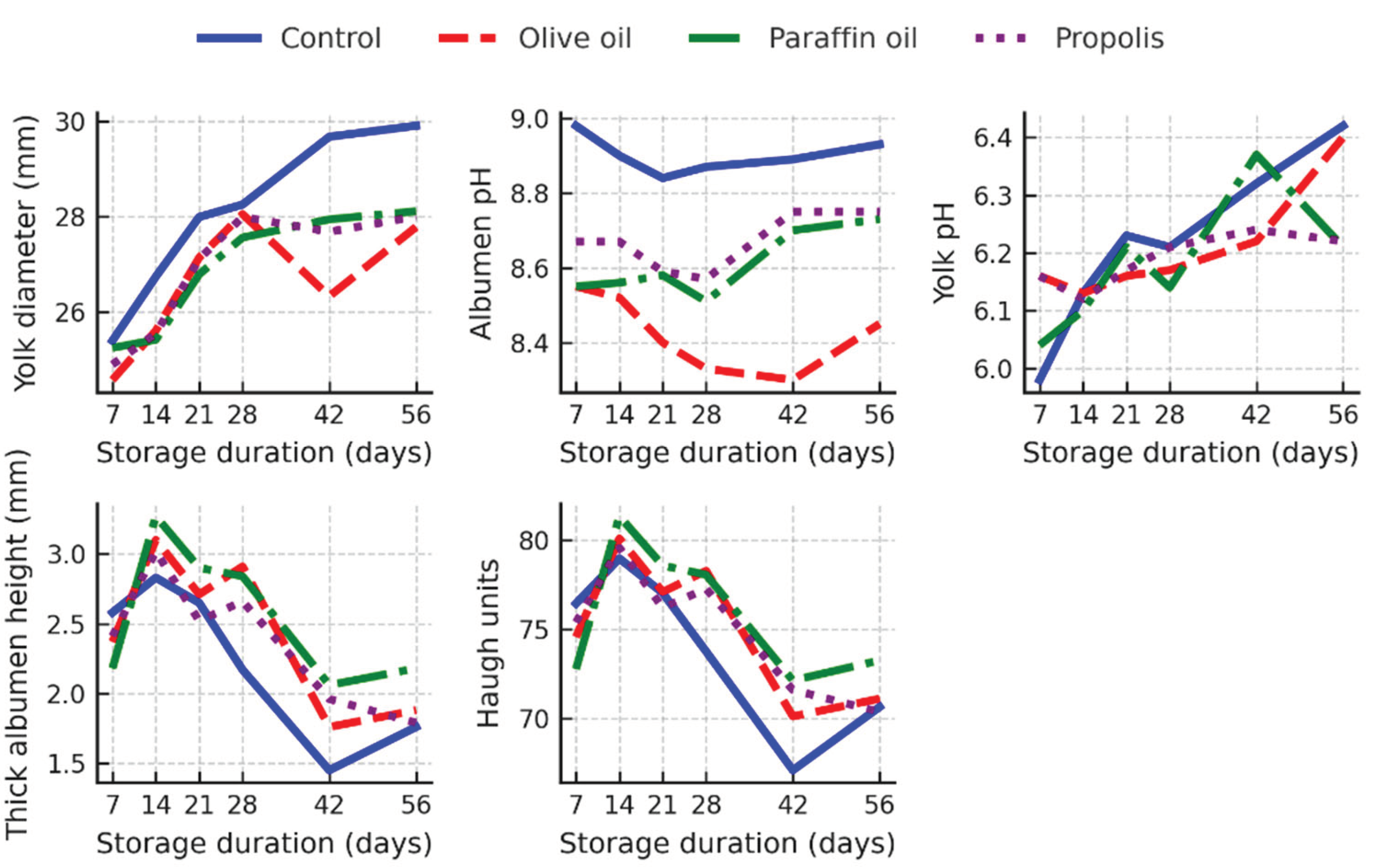

3.6. Interaction Between Storage Duration and Treatment

Regarding the interaction effects between storage duration and treatment group in both hen and quail eggs, the most consistent and biologically relevant differences were observed between coated and uncoated eggs, especially in the later stages of storage (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

In hen eggs, yolk diameter increased most significantly (p < 0.05) over time in uncoated (control) eggs, reaching 46.68 mm after 56 days, compared to significantly (p < 0.05) lower and more stable values in all coated groups (e.g. ~42 mm in olive oil and paraffin coated eggs) (

Figure 5).

Albumen pH increased steadily in the control group, peaking at 9.02 on day 14 and remaining high thereafter. In contrast, oil-coated eggs maintained significantly (p < 0.05) lower albumen pH values (~7.8–7.9) throughout the storage period compared to uncoated eggs and after 14 days of storage also compared to propolis-coated eggs.

Thick albumen height and HU decreased significantly over time in the control eggs (from 4.61 mm to 2.60 mm and from 63.14 to 37.12 HU), while the paraffin and olive oil coatings helped to maintain higher thick albumen height (up to ~5.0 mm) and better HU values (up to ~70).

Shell strength and yolk pH did not show consistent patterns over time or treatment, although slight variations were noted (

Figure 5).

The observed interactions in quail eggs followed similar trends as in hen eggs, although the differences were slightly less pronounced compared to hen eggs (

Figure 6).

The yolk diameter increased with age. However, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was only observed after day 42, when the control group eggs had a significantly larger yolk diameter compared to all other treatment groups, reaching almost 30 mm on day 56, while the coated eggs maintained smaller diameters of around 27–28 mm (

Figure 6).

Compared to the control group, the pH of the albumen remained lower in the oil-coated eggs throughout the experiment (e.g. 8.33–8.45 in olive oil), while the control eggs had consistently higher values (up to 8.98–8.93). In absolute terms, the height of the thick albumen was best maintained in paraffin-coated eggs throughout the storage period, although the difference to the control group was only statistically significant on day 28 (p < 0.05). The differences in yolk pH were less variable between treatments (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Storage Conditions on the Quality Parameters of Hen and Quail Eggs

In both species, the external morphological characteristics such as width, length, shape index, surface area and volume of the eggs were not significantly influenced by the storage temperature. This was to be expected, as temperature-induced changes in external dimensions are generally minimal and can only be detected with very high-precision measuring devices. This result is supported by the study by [

24], in which they observed no significant influence of storage temperature on the shape index, shell thickness or shell weight of hen's eggs.

In contrast, internal quality parameters showed clear and consistent responses to storage conditions, highlighting the critical role of temperature in egg preservation. Eggs stored in the cold room (12 °C) maintained their internal quality significantly better than eggs stored at room temperature (22 °C). In hen and quail eggs, storage at room temperature resulted in significantly larger yolk diameters, higher pH values in both the albumen and the yolk and lower values for thick albumen height and HU. These changes reflect the accelerated aging of the eggs, which is due to the increased diffusion of carbon dioxide through the eggshell at elevated temperatures, leading to alkalization of the albumen [

2,

25,

26]. According to [

27], lower storage temperatures slow down the increase in the pH value of the albumen, while [

28] found no significant temperature effect after 28 days of storage. The resulting alkalization not only contributes to an increased albumen pH, but also to the dilution of the albumen [

29], the weakening of the yolk membrane and the enlargement of the yolk [

25] - all processes that reduce the functional and nutritional quality of the eggs. Higher albumen alkalinity reduces the ovomucin content [

30], which leads to the breakdown of the thick, gelatinous albumen layer [

29] and liquefaction of the albumen. Consequently, both hen and quail eggs stored at room temperature exhibited lower albumen height and lower HU values. The significant decrease in thick albumen height at room temperature is consistent with the results of other studies [

31,

32,

33]. Since HU is strongly and positively correlated with thick albumen height, this also explains the lower HU values observed at room temperature.

Higher storage temperatures promote the diffusion of alkaline compounds and water from the egg albumen into the yolk [

34], which increases the pH of the yolk. This process is accelerated by the thermal weakening of the yolk membrane [

35], while cooling helps to maintain membrane integrity and slow down this exchange. This could be the reason for the significantly higher yolk pH observed in both hen and quail eggs stored at room temperatures.

Refrigerated hen eggs had a darker yolk color, which is probably due to less degradation of carotenoid pigments such as lutein and zeaxanthin. Due to their highly unsaturated structure, lutein and zeaxanthin are particularly sensitive to higher temperatures, but also to light and oxygen. This makes them susceptible to spontaneous oxidation, isomerization and degradation in food matrices [

36]. Lower temperatures inhibit oxidative and enzymatic reactions that would otherwise lighten yolk color, and limited water transfer into the yolk helps maintain pigment concentration. These results are consistent with those of [

4], who reported higher yolk brightness at room temperature, but are in contrast to [

37], who found no temperature effect on yolk color between 3 °C and 10 °C.

Similar trends observed in hen and quail eggs confirm that quail eggs, like hen eggs, are very sensitive to deterioration at sub-optimal storage temperatures. An interesting observation was that shell strength was slightly higher in hen eggs after storage at room temperature, whereas no significant difference in shell strength was observed in quail eggs, suggesting species-specific responses probably related to differences in eggshell structure and composition.

Although many studies [

3,

25,

38,

39,

40] reported greater egg weight loss at room temperature due to enhanced moisture and gas diffusion [

25], our results showed no significant difference between storage conditions. This could be due to active ventilation in the cold room [

41,

42], which probably disrupted the moist boundary layer around the eggshell despite the higher relative humidity. Such air circulation maintains a steep vapor pressure gradient that favors moisture loss and thus negates the expected benefit of lower temperature to reduce weight loss.

4.2. Influence of Surface Coatings on the Quality Characteristics of Hen and Quail Eggs

Compared to uncoated controls, all coatings showed positive effects, although there were significant differences between the individual coating types. In particular, both hen and quail eggs coated with olive oil or paraffin oil showed significantly less weight loss during storage. These results highlight the effectiveness of oil-based coatings in minimizing moisture evaporation, probably by forming a physical barrier that restricts water diffusion through the eggshell. Similar results were reported by [

11,

13,

43,

44], who demonstrated that oil coatings effectively seal the pores of the shell, thereby reducing water loss during storage.

In addition to lower weight loss, paraffin oil also resulted in the highest HU values and thick albumen heights in both species. This result indicates better preservation of albumen structure and freshness, which is due to the ability of the oil coating to reduce CO₂ loss and consequently slow down the alkalization of the albumen.

Hen eggs coated with propolis showed a distinct color profile of the yolk. Although treatment with propolis did not significantly reduce weight loss during storage, it was associated with an increase in yolk color intensity. This effect may be attributed to the antioxidant properties of propolis, which can reduce lipid oxidation and delay pigment degradation in the yolk. Propolis is rich in bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, phenolic acids and flavones, which are known for their strong antioxidant capacity [

45]

, and can indirectly contribute to the preservation and stabilization of yolk pigments. In addition, the antimicrobial properties of propolis, as well as the antimicrobial activity of the ethanol used in the propolis extract, may help to inhibit microbial growth on the eggshell surface, thereby reducing the risk of pigment degradation by microbial metabolism [

17,

46]. The observed preservation of yolk pigmentation in propolis-coated eggs could therefore be due to a synergistic effect of antioxidant and antimicrobial mechanisms. These observations are consistent with the findings of [

19], who reported that eggs coated with a 30% ethanolic propolis extract showed significantly lower microbial contamination, including complete inhibition of aerobic mesophilic bacteria and

Staphylococcus spp. after 35 days of storage at 25 °C. While the study also showed a significant reduction in weight loss - in contrast to the present results - the consistent maintenance of thick albumen height, HU levels and microbial suppression supports the proposed protective role of propolis for yolk and albumen stability. Additional support comes from the study by [

47], who investigated the effects of propolis coatings on Japanese quail eggs. In their study, eggs treated with 10 % and 15 % propolis extract showed the lowest weight loss, the highest HU values and the most delayed increase in albumen pH during five weeks of storage at 25 °C. Although these results differ from those of the present study in terms of weight loss, they emphasize the role of propolis in maintaining the internal quality of the eggs.

Regarding pH measurements, no significant differences in yolk pH were found between treatments in both species. However, significant differences were found in the pH of the albumen. Uncoated eggs had a significantly higher albumen pH than coated eggs, suggesting a greater loss of CO₂ during storage. In the coated eggs, the eggs treated with propolis had a significantly higher albumen pH than those treated with oils. This indicates that the oil coatings were more effective in reducing CO₂ diffusion and the resulting pH increase, while the propolis coating was comparatively less effective in this respect.

4.3. Temporal Changes in the Quality Parameters of Eggs During Storage

The temporal development of the quality characteristics of hen eggs and Japanese quail eggs was systematically evaluated over a storage period of 56 days. The results show that the external morphological parameters — including the width, height, shape index, surface area and volume of the eggs — remained largely unchanged throughout the study, indicating that these characteristics are stable and are not significantly affected by the storage period.

In contrast, the internal quality parameters of both species deteriorated more and more over time. Significant weight loss occurred after 42 days in hen eggs and 56 days in quail eggs, most likely due to moisture loss through the eggshell. This is in line with previous studies [

25,

38,

39], which emphasized the role of shell permeability and ambient humidity in influencing evaporation losses. A clear sign of egg aging was the progressive increase in yolk diameter observed after 42 days in hen eggs and 28 days in quail eggs. This increase in size reflects the flattening of the yolk and the weakening of the yolk membrane, a process supported by the findings of [

48], who describe the migration of water from the albumen into the yolk as a contributing factor to yolk expansion. A gradual increase in the pH of the albumen and yolk was observed in hen eggs. In quail eggs, however, only the pH of the yolk increased significantly over time, while the pH of the albumen remained relatively stable. In fresh eggs, carbon dioxide is present in the albumen in the form of bicarbonate. During storage, CO₂ diffuses through the pores of the egg shell, which leads to alkalization and a subsequent decrease in the viscosity of the albumen [

31,

32,

49]. On day 56, both hen and quail eggs had the lowest values for thick albumen height and HU. This trend reflects albumen liquefaction, which has been widely documented [

32,

50] and is characterized by a decrease in thick albumen height over time. The strong decrease in thick albumen height is an indication of reduced albumen quality and contributes directly to the reduced HU values [

25,

33,

51].

Shell strength remained relatively stable in both species. However, a slight but statistically significant decrease was observed in hen eggs after 14 and 21 days, while a significant increase was observed in quail eggs after 42 days. These results suggest that the structural integrity of the shell is largely maintained at controlled temperature and humidity, although subtle microstructural changes may still occur.

Interestingly, the color of the yolk of hen's eggs did not change significantly during the 56-day storage period. This stability can be attributed to the chemical nature of the pigments responsible for yolk coloration, primarily carotenoids such as lutein and zeaxanthin. These compounds are relatively stable in the absence of light and oxygen [

36], especially if the eggs are stored under controlled conditions (e.g. low temperature and humidity). In addition, the yolk is enclosed by the yolk membrane and surrounded by albumen and shell, which act as physical barriers and limit exposure to oxidative stress. These results suggest that yolk color is relatively stable under controlled environmental conditions and that pigment degradation requires either more severe environmental stressors or longer storage times to become apparent.

4.4. Interaction Effects Between Storage Temperature, Coating Treatment and Storage Duration

In addition to the individual effects of storage temperature, coating treatment and storage duration, several significant interactions between these factors were found in this study, highlighting the complex and dynamic nature of egg quality deterioration under different storage conditions.

The interaction between storage temperature and coating treatment was particularly evident in relation to albumen height and HU, especially in hen eggs. While both olive and paraffin oil coatings were effective in slowing the deterioration of these quality parameters, their protective effect was more pronounced at room temperature, where deterioration would otherwise progress more rapidly. These results emphasize the importance of coating choice in non-refrigerated environments, where oil-based barriers appear to partially compensate for the lack of refrigeration.

A further interaction was observed between the type of coating and storage time, particularly in influencing the pH of the albumen. In uncoated eggs, the pH of the albumen increased steadily over time, indicating a loss of CO₂ and alkalization of the albumen [

2,

25,

26]. In contrast, oil-coated eggs - especially those treated with paraffin oil - showed a delayed increase in pH, supporting the hypothesis that hydrophobic coatings [

52,

53] reduce gas permeability. Although propolis-treated eggs also showed some buffering effect, the results indicate a weaker barrier function compared to lipid-based coatings, probably due to the more hydrophilic nature [

54] of the propolis matrix.

The interaction between storage temperature and duration reinforced the expected pattern of accelerated quality loss under room conditions. Albumen thinning, HU reduction and yolk enlargement were significantly more pronounced over time in eggs stored at room temperature. These effects were partially attenuated by coatings, especially oils, but remained significant in the uncoated and propolis-treated groups. The stabilization of yolk pH across all treatments and temperatures indicates that the yolk reacts less strongly to environmental changes within the time frame studied, which is probably due to the selective permeability [

55] of the yolk membrane.

Similar interaction trends were observed in quail eggs, although the magnitude of treatment effects was generally less pronounced than in hen eggs. This could be due to species-specific differences in shell structure, surface area to volume ratio or yolk buffering capacity. For example, the variability of yolk diameter as a function of treatment and storage time was greater in quail eggs, indicating possible differences in the dynamics of water migration.

Overall, the interaction analysis emphasizes that the effectiveness of a particular coating treatment cannot be fully evaluated in isolation, but must be interpreted in the context of the storage environment and storage duration.

4.5. Implications and Future Prospects

When recommending suitable coating materials for egg quality preservation, it is critical to evaluate not only their effectiveness in maintaining internal freshness at different storage temperatures and times, but also their economic feasibility, toxicological safety, biodegradability, water resistance, migration and regulatory compliance [

5]. Under USDA and European Union regulations, edible coatings are classified as food additives or ingredients; therefore, the materials used must be food grade, non-toxic and applied under strict sanitary conditions [

5].

Importantly, many commonly used edible coatings are derived from allergenic foods such as milk, soy, peanuts or wheat, requiring allergen labeling and potentially restricting their use [

5,

56]. In contrast, paraffin oil and olive oil offer significant advantages. Both are widely available, relatively inexpensive and recognized as safe for food contact. Paraffin oil, a purified mineral oil, is specifically recommended for egg coatings due to its low volatility and excellent barrier properties that slow down moisture and CO₂ loss and help maintain albumen structure. It is inert, protein-free and non-allergenic, making it a practical choice for large-scale use in the egg industry. Similarly, olive oil is a natural, food-grade lipid with minimal allergenic potential and proven effectiveness in reducing weight loss and maintaining internal egg quality, especially when stored at room temperature. Although both oils are functionally effective, their use must also be evaluated in terms of consumer acceptance and industrial scalability. Although the coating process drives up the overall cost of the product, simple oil coatings offer a cost-effective and safe alternative to refrigeration, especially in resource-limited areas. Therefore, further research on scaling, automation and microbiological impact is warranted to facilitate the commercial application of such coatings. The development of hybrid formulations - combining oils with natural bioactives (e.g. propolis) - could also improve barrier and antimicrobial performance and offers a promising direction for future innovation in egg preservation technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, D.T.; investigation, visualization, and original draft preparation, D.T., Z.B.K. and M.B.; validation and writing—review and editing, D.T., Z.B.K. and M.B.; resources and data curation, D.T.; resources, M.B.; formal analysis and validation, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Ms Renata Bregar and Mr Žiga Mikolič for their valuable help in conducting the egg analyses. Their technical support and commitment contributed significantly to the successful completion of this work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 40 for the purposes of generating figures and graphical abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mellor, D.B.; Gardner, F.A.; Campos, E.J. Effect of type of package and storage temperature on interior quality of shell treated shell eggs. Poult. Sci. 1975, 54, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, W.I.; Han, Y.K. Effects of storage temperature and time on the quality of eggs from laying hens at peak production. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 24, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Tabidi, M.H. Impact of storage period and quality on composition of table eggs. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2011, 5, 856–861. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Yum, K.H.; Lee, W.T.; Park, S.H.; Lim, Y.H.; Choi, N.Y. , Jang, S.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.H. Effects of storage temperature and egg washing on egg quality and physicochemical properties. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf Eddin, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Tahergorabi, R. Egg quality and safety with an overview of edible coating application for egg preservation. Food Chem. 2019, 296, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, M.L.; Gittins, J.; Sparks, A.W.; Humphrey, T.J.; Burton, C.; Moore, A. An assessment of the microbiological risks involved with egg washing under commercial conditions. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, A.B.; Curtis, P.A.; Anderson, K.E.; Kerth, L.K.; Oyarazabal, O.; Jones, D.R.; Musgrove, M. T. The effects of commercial cool water washing of shell eggs on Haugh unit, vitelline membrane strength, aerobic microorganisms, and fungi. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahergorabi, R.; Matak, K.E.; Jaczynski, J. Application of electron beam to inactivate Salmonella in food: Recent developments. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrani, M.; Payne, C.G. Effect of oiling on internal quality of eggs stored at 28 and 12°C. Br. Poult. Sci. 1978, 19, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, B.; Bond, C.; Diab, M. Egg quality as affected by storage and handling methods. J. Food Qual. 1980, 3, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waimaleongora-Ek, P.; Garcia, K.M.; No, H.K.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Ingram, D.R. Selected quality and shelf life of eggs coated with mineral oil with different viscosities. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obanu, Z.A.; Mpieri, A.A. Efficiency of dietary vegetable oils in preserving the quality of shell eggs under ambient tropical conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1984, 35, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.N.; No, H.K.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Internal quality and shelf life of eggs coated with oils from different sources. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banskota, A.H.; Tezuka, Y.; Kadota, S. Recent progress in pharmacological research of propolis. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, M.C. Propolis: chemical composition, biological properties and therapeutic activity. Apidologie 1995, 26, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocot, J.; Kiełczykowska, M.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Kurzepa, J.; Musik, I. Antioxidant potential of propolis, bee pollen, and royal jelly: Possible medical application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 7074209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.G.S.; Pires, P.D.S.; Cardinal, K.M.; Leuven, A.F.R.; Kindlein, L.; Andretta, I. Effects of rice protein coatings combined or not with propolis on shelf life of eggs. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4196–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.C.B.; Brito, D.A.P.; Soares, S.C.P.; Gomes, K.S.; Saldanha, G.K.M.S.; Soares, V. S. Maintenance of quality of eggs submitted to treatment with propolis extract and sanitizers. Acta Sci. Anim. Sci. 2022, 44, e53584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narushin, V.G. Egg geometry calculation using the measurements of length and breadth. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchev, A. Quality and composition of Japanese quail eggs (Coturnix japonica). Trakia J. Sci. 2012, 10, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tyc, J.; Wysok, B.; Drażbo, A.; Naczmański, J.; Szymański, Ł. External and internal quality traits of eggs from different ornamental chicken breeds. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2023, 26, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 14.2 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, Y.; Kasim, A.; Omar, H.; Sazili, A.Q. Effect of storage time and temperature on the quality characteristics of chicken eggs. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2014, 12, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Feddern, V.; De Prá, M.C.; Mores, R.; Nicoloso, R. da S.; Coldebella, A.; de Abreu, P.G. Egg quality assessment at different storage conditions, seasons and laying hen strains. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2017, 41, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashorn, M.A. Effects of storage conditions on egg quality. Lohmann Information 2016, 50, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Škrbić, Z.; Lukić, M.; Petričević, V.; Bogosavljević-Bošković, S.; Rakonjac, S.; Dosković, V.; Tolimir, N. Egg quality of Banat naked neck hens during storage. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2021, 37(1), 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandikçi Altunatmaz, S.; Aksu, F.; Aktaram Bala, D.; Akyazi, İ.; Çelik, C. Evaluation of quality parameters of chicken eggs stored at different temperatures. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2020, 26, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, L.; Al-Shami, A.; Mikhaylenko, G.; Tang, J. Dielectric characterization of hen eggs during storage. J. Food Eng. 2007, 82, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Omana, D.A.; Wu, J. Effect of shell eggs storage on ovomucin extraction. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2280–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, M.; Kuźniacka, J.; Czarnecki, R.; Kucharska-Gaca, J.; Kowalska, E. Variation in egg quality traits depending on storage conditions. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2017, 32, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marzec, A.; Damaziak, K.; Kowalska, H.; Riedel, J.; Michalczuk, M.; Koczywąs, E.; Cisneros, F.; Lenart, A.; Niemiec, J. Effect of hens age and storage time on functional and physiochemical properties of eggs. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2019, 28, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabib, I.; Onbaşilar, E.E.; Yalçin, S. The effects of cage type, oviposition time and egg storage period on the egg quality characteristics of laying hens. Ank. Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2021, 68, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.L. Chemical and related osmotic changes in egg albumen during storage. Poult. Sci. 1977, 56, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R. Conserving and monitoring shell egg quality. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium 2006; Poultry Research Foundation, University of Sydney; Sydney, Australia, 2006; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.D.; Huang, W.Y.; Li, D.J.; Song, J.F.; Liu, C.Q.; Wei, Q.Y.; Zhang, M.W. Thermal degradation kinetics of all-trans and cis-carotenoids in a light-induced model system. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, Y.O.; Kwon, J.T. Effects of egg storage, storage temperature, and insemination of hens on egg quality. Korean J. Poult. Sci. 2004, 31, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sati, N.M.; Oshibanjo, D.O.; Emennaa, P.E.; Mbuka, J.J.; Haliru, H.; Ponfa, S.B.; Abimiku, O.R.; Nwamo, A.C. Egg quality assessment within day 0 to 10 as affected by storage temperature. Asian J. Res. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 3, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Ward, G.E.; Regmi, P.; Karcher, D.M. Impact of egg handling and conditions during extended storage on egg quality. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 97–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodacki, A.; Batkowska, J.; Drabik, K.; Chabroszewska, P.; Łuczkiewicz, P. Selected quality traits of table eggs depending on storage time and temperature. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2016–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, D.P.; Brusewitz, G.H.; Smith, M.W.; Zhang, X. Humidity and airflow during storage affect peach quality. HortScience 1994, 29, 29–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimenu, S.M.; Koo, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, B.S. Kinetic modeling impacts of relative humidity, storage temperature, and air flow velocity on various indices of hen egg freshness. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 4384–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biladeau, A.M.; Keener, K.M. The effects of edible coatings on chicken egg quality under refrigerated storage. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirangrat, W.; Torrico, D.D.; No, J.; No, H.K.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Effects of mineral oil coating on internal quality of chicken eggs under refrigerated storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendueles, E.; Mauriz, E.; Sanz-Gómez, J.; González-Paramás, A. M.; Vallejo-Pascual, M.-E.; Adanero-Jorge, F.; García-Fernández, C. Biochemical profile and antioxidant properties of propolis from Northern Spain. Foods 2023, 12, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanović, S.; Antić, N.; Dakić, I.; Švabić-Vlahović, M. In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis and synergism between propolis and antimicrobial drugs. Microbiol. Res. 2003, 158, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, G.C.; Canogullari, S.; Baylan, M.; Alasahan, S.; Aygun, A. The use of propolis extract for the storage of quail eggs. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2015, 24, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, M.O.; Olaitan, N.I.; Ochefu, J.H. Effect of storage conditions on the quality attributes of shell (table) eggs. Niger. Food J. 2013, 31, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Keener, K.M.; Lukito, V.D. Influence of carbon dioxide on the activity of chicken egg white lysozyme. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, L.A.F.; Ekine, O.A. Evaluation of commercial layer feeds and their impact on performance and egg quality. Niger. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 20, 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, N.; Gao, S.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Sheng, X.; Wang, X.; Xing, K.; Xiao, L.; Ni, H.; Qi, X. Effects of supplementing natural astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis to laying hens on egg quality during storage at 4 °C and 25 °C. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6877–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachtanapun, P.; Homsaard, N.; Kodsangma, A.; Leksawasdi, N.; Phimolsiripol, Y.; Phongthai, S.; Khemacheewakul, J.; Seesuriyachan, P.; Chaiyaso, T.; Chotinan, S.; Jantrawut, P.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Wangtueai, S.; Sommano, S. R.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Jantanasakulwong, K. Effect of egg-coating material properties by blending cassava starch with methyl celluloses and waxes on egg quality. Polym. 2021, 13, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahansoy, H.; Caner, C.; Yüceer, M. The shellac and shellac nanocomposite coatings on enhanced the storage stability of fresh eggs for sustainable packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261(Pt 1), 129817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, J. F.; Mokochinski, J. B.; Torres, Y. R. Chemical characterization of the hydrophilic fraction of (geo)propolis from Brazilian stingless bees. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J. L. Investigation of changes in yolk moisture. Poult. Sci. 1975, 54, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Patil, T. D.; Gaikwad, K. K. Plant-based edible films and coatings for food-packaging applications: Recent advances, applications, and trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).