1. Introduction

Egg quality is a critical attribute for both industry and consumers, encompassing external traits such as weight and shell thickness and internal traits such as albumen height, Haugh units, yolk color, and the yolk index. These parameters are influenced by genetics, nutrition, rearing conditions, storage time and temperature, and the age of the laying hens. As hens age, their eggs exhibit decreased shell quality, reduced albumen viscosity, and alterations in component proportions, which compromise both table use and industrial applications [

1,

2].

Age-related changes have been extensively studied. At the physiological level, modifications occur in progesterone receptor expression and in the morphology of the magnum, which can impair proper albumen formation [

3,

4]. In parallel, changes in the concentration and activity of albumen antimicrobial proteins occur with hen age: several studies report that the lysozyme concentration and enzymatic activity tend to increase in eggs from older hens, which may interact with other age-related declines in albumen physical quality to affect overall egg resistance to contamination and storage stability [

5,

6,

7].

Despite these limitations, flocks at advanced ages, including those over 80 weeks, remain in production owing to the economic need to maximize flock use. Consequently, their eggs continue to enter the market for industrial processing [

2,

8].

Given this scenario, strategies to extend shelf-life and maintain egg quality are of increasing interest, especially for eggs from older hens, which are more fragile and prone to quality deterioration. The use of coatings to slow egg degradation has been studied for decades, with mineral oil applied since the first half of the 20th century [

9]. However, as a petroleum-derived product, mineral oil has limited commercial appeal in current markets, particularly among consumers seeking environmentally sustainable and residue-free products.

Natural coatings, therefore, represent a promising alternative. Edible coatings and biofilms act as physical and selective barriers, reducing moisture loss and delaying internal quality decline [

10]. Various natural materials have been tested, including carnauba wax, which has proven effective in slowing internal losses [

11,

12];

Aloe vera, which is valued for its polysaccharides and bioactive compounds [

13]; and whey protein, which forms stable and functional protein-based films with protective effects [

14]. Recent reviews have shown that biofilms with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties are promising for egg preservation [

15,

16].

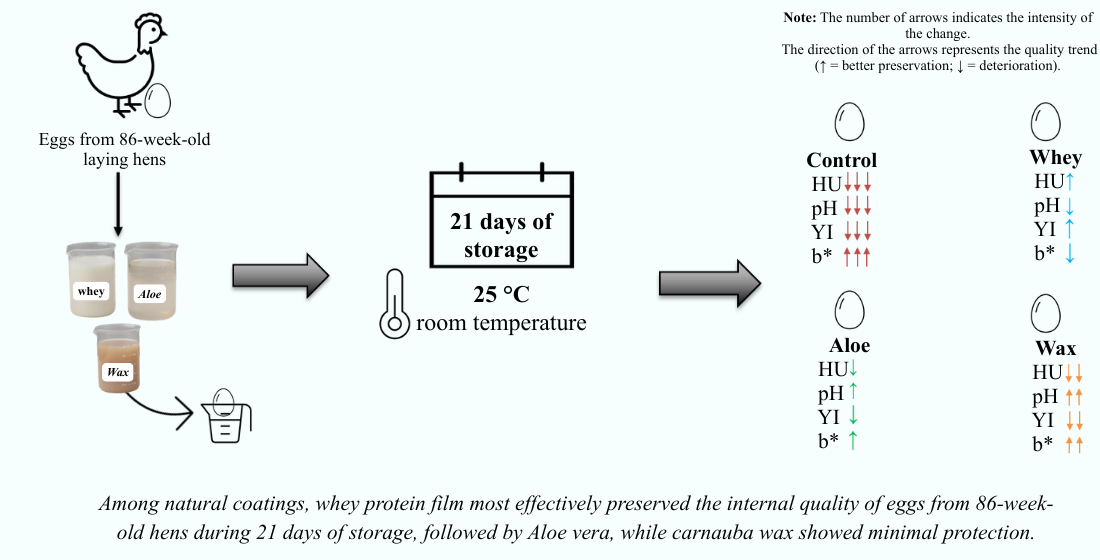

Therefore, investigating biofilms in eggs from older hens is particularly relevant, as studies in this context remain limited. The application of natural coatings may reduce the qualitative losses typical of advanced production stages while offering a sustainable alternative for the preservation of eggs destined for both direct consumption and industrial use. The hypothesis is that natural biofilms based on whey protein, aloe vera, and carnauba wax would be effective in maintaining the internal quality of eggs from older hens during storage. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the internal quality of eggs from 86-week-old hens coated with different materials (carnauba wax, Aloe vera, and whey protein) and stored at room temperature for 21 days. This study contributes to the development of eco-friendly preservation methods to extend the shelf-life of eggs from aged hens and reduce quality losses during storage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Conditions

The experiment was conducted in Jaboticabal, São Paulo, Brazil (21.2437° S, 48.2995° W) in November 2024. Eggs were obtained from 86-week-old Hisex White hens raised in a conventional cage system, and no procedures were performed on live animals for the purpose of this study.

2.2. Experimental Design

A completely randomized design with a 4 × 4 factorial arrangement (coating treatments × storage periods) was used. The treatments included uncoated eggs (control) and eggs coated with whey protein, Aloe vera, or carnauba wax. Eggs were stored at room temperature for 0, 7, 14, and 21 days. Fresh eggs were analyzed on day 0 to obtain the control group. Thirteen treatment combinations were tested, with 15 replicates (one egg per replicate), totaling 195 eggs.

2.3. Preparation of Biofilms

The coating solutions were prepared according to the literature protocols, with adaptations for this study. The whey protein solution contained 8% whey protein and 4% glycerol [

17]. Carnauba wax, which was commercially diluted in vegetable resin (60% carnauba wax and 40% resin), was used at 10% with 4% glycerol.

Aloe vera gel was used in its natural form without dilution or heating.

Glycerol was added as a plasticizer to improve film flexibility and reduce brittleness, as hydrophilic plasticizers are commonly incorporated into protein and lipid matrices [

18]. Since wax-based coatings tend to form rigid but less homogeneous barriers [

19], additional glycerol was included to increase flexibility while maintaining protective properties.

Solutions (

with the exception of Aloe vera) were heated in a water bath using beakers placed in an aluminum pan over a tripod with asbestos mesh and a refractory disk to avoid direct flame contact. The whey protein mixture was maintained at 40–50 °C for 10 min, while the carnauba wax mixture was heated to 60–80 °C for 10 min. The temperature was monitored via a digital penetration thermometer (SA9791 PLUS). After heating, the solutions were cooled and homogenized on a magnetic stirrer (Fisatom). The pH was adjusted following the methods of Alleoni and Antunes [

1] to ensure stability and uniformity.

Preparation of Aloe vera gel

Fresh Aloe vera leaves were purchased from a commercial supplier. Leaves were washed under running water and longitudinally cut, and the mucilaginous parenchyma was manually extracted. The gel was homogenized in a blender until a uniform gel was obtained and used directly for egg coating.

2.4. Application of Coatings

Eggs were immersed in the coating solutions for 1 min in 500 mL beakers. The eggs were then placed on metal grids and air-dried for 1 h. After drying, the eggs were stored in cellulose pulp trays under room conditions, simulating common commercial practices. The temperature and relative humidity were monitored with a digital thermohygrometer throughout the experiment. The average maximum temperature was 31.3 ± 0.6 °C, with a minimum of 20.7 ± 0.6 °C, and the relative humidity ranged from 29.4 ± 10.0% (minimum) to 75.2 ± 10.2% (maximum).

2.5. Quality Assessment

On day 0, eggshell thickness was measured to characterize initial quality. Throughout storage, egg weight, albumen height, yolk diameter and height, albumen pH, and yolk color were determined.

Eggs were weighed on a precision balance (Bel® S2202H) and then broken onto a marble surface. The albumen height was measured via a tripod micrometer. Yolks were separated, and their diameter and height were measured with a digital caliper (Mitutoyo, São Paulo, Brazil). Yolk color was evaluated via a Minolta CR-400 colorimeter (Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Osaka, Japan) in the CIELab system: L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness).

The albumen pH was measured via a handheld penetration pH meter (Testo 205), which was previously calibrated. The albumen and yolk were separated into labeled containers, and the pH was recorded individually.

The yolk index (YI) was calculated as YI = yolk height/yolk diameter. Haugh units (HUs) were calculated according to the following formula:

where H = albumen height (mm) and W = egg weight (g) [

20].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SAS® OnDemand for Academics, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Means were compared via Tukey’s test at the 5% significance level. Polynomial orthogonal contrasts (linear and quadratic) were applied to evaluate storage time effects.

3. Results

The internal quality parameters of eggs were significantly influenced by both storage time and coating treatment, with a significant interaction (

p < 0.05) observed for all traits except yolk color parameters a* and L*. Fresh eggs presented an average shell thickness of 0.36 mm (

Table 1).

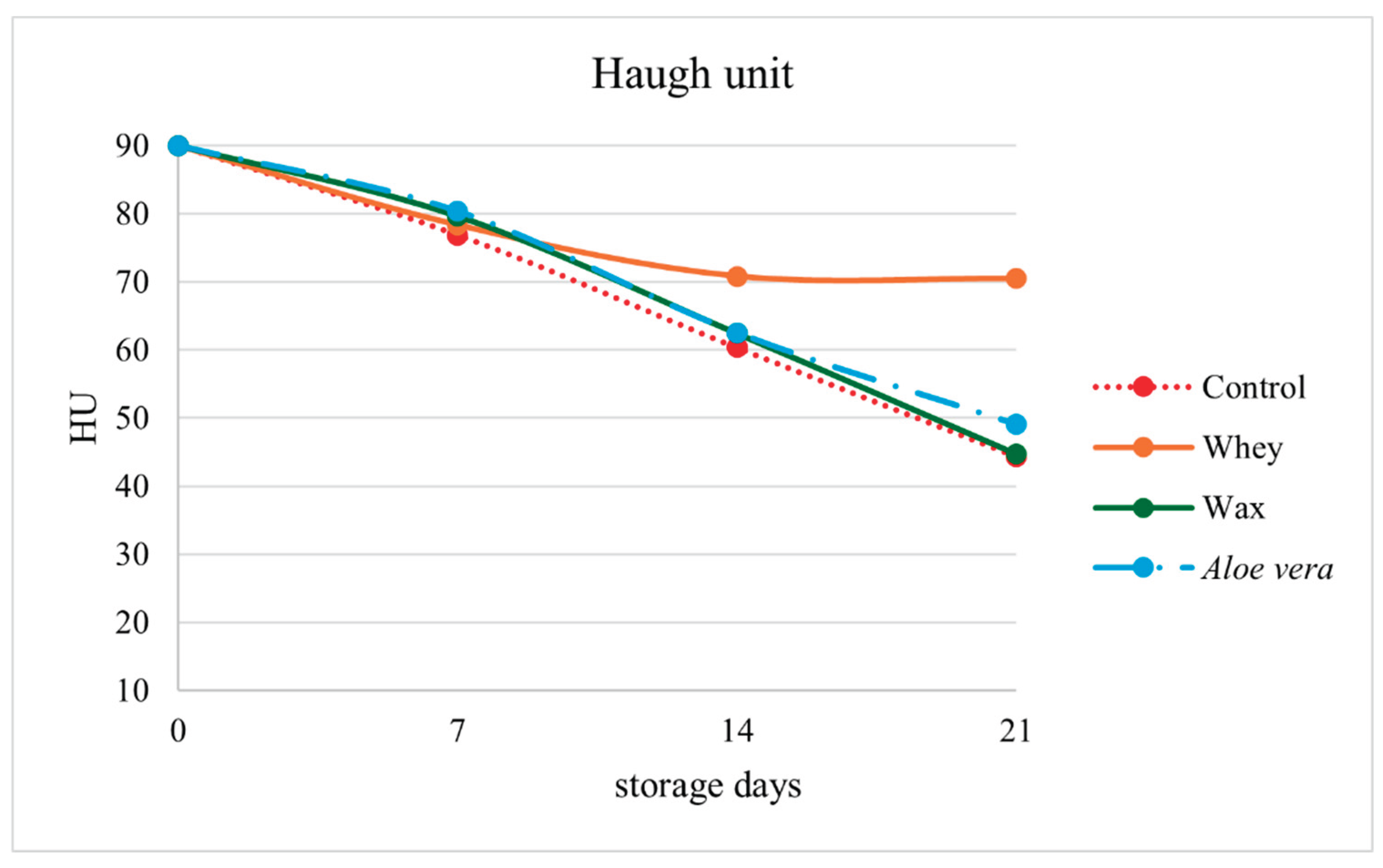

The Haugh unit (HU) was significantly affected by both storage time and coating treatment

(p < 0.001). Fresh eggs had a mean HU of 90.00. In the control group, the HU values decreased sharply over time, reaching 44.38 at 21 days. In contrast, the whey protein and

Aloe vera coatings better preserved the albumen quality. At 7 days, the HU values of 78.35 (whey) and 80.38 (

Aloe vera) were significantly greater than those of the control (76.90). At 14 days, whey-coated eggs maintained the highest HU (70.81), whereas

Aloe vera and carnauba wax markedly reduced HU (62.42 and 62.53, respectively). At 21 days, whey remained superior (70.46), whereas uncoated eggs presented the lowest value (44.38) (

Figure 1).

The yolk index (YI) followed a similar trend to that of HU (

p < 0.001). Fresh eggs presented an average YI of 0.40, which progressively decreased during storage. At 7 days, the whey (0.35) and

Aloe vera (0.37) treatments maintained higher YIs than did the control (0.32). At 14 days, whey still presented the best value (0.32), while the control and carnauba wax contents decreased to less than 0.30. At 21 days, whey maintained a YI of 0.31, whereas that of the other treatments declined more markedly (

Table 1).

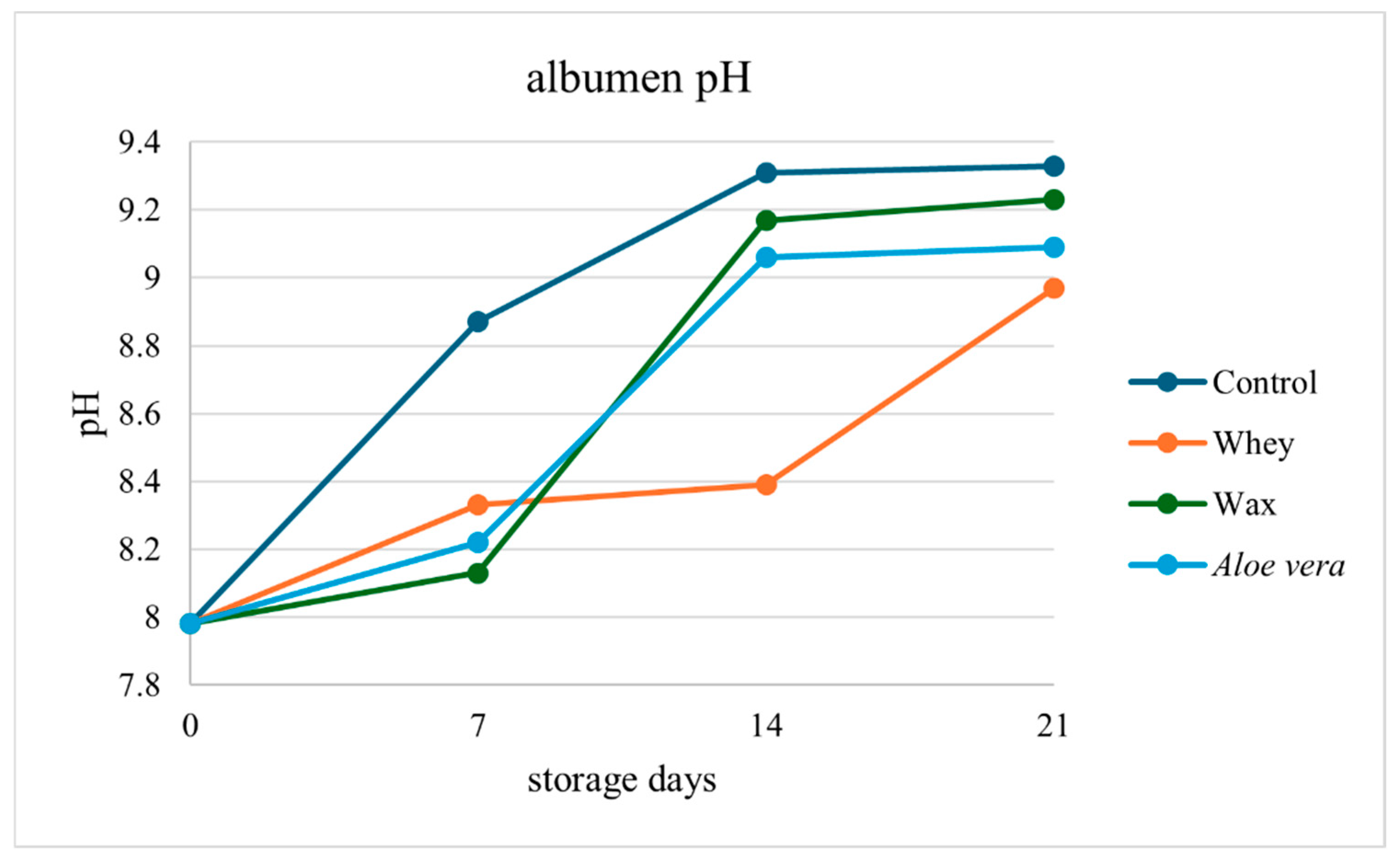

Albumen pH was significantly affected by storage time (

p < 0.001). Fresh eggs had an average pH of 7.98 (

Table 1). After 7 days, the whey- and

Aloe vera-coated eggs presented lower pH values (8.33 and 8.22, respectively) than the control eggs did (8.87). Over time, whey and

Aloe vera maintained relatively stable pH levels, whereas the pH of the control group progressively increased (

Figure 2).

Yolk color analysis revealed no significant variation in L* with storage time (

p = 0.074), coating treatment (

p = 0.192), or their interaction (

p = 0.143). Parameter a* was unaffected by storage (

p = 0.952) or the interaction (

p = 0.995) but was influenced by coating treatment

(p = 0.008) (

Table 1). The parameter b* was significantly influenced by storage, coating, and their interaction (

p < 0.05). A progressive increase was observed in all the groups, indicating increased yolk yellowness. At 21 days, the control (54.91) and carnauba wax (54.17) groups presented the highest b* values, suggesting greater pigment oxidation, whereas the whey (48.62) and

Aloe vera (49.97) groups presented smaller increases, remaining closer to fresh egg values.

Overall, the application of natural biofilms, particularly those based on whey protein and Aloe vera, effectively preserved albumen viscosity and yolk structure, as evidenced by higher HU and YI values and lower albumen pH during storage. These results confirm the potential of protein- and polysaccharide-based coatings to extend the shelf-life of eggs from aged hens under room temperature conditions.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that whey protein, Aloe vera, and Carnauba wax biofilms significantly influenced the preservation of internal egg quality in 86-week-old hens. This response is directly linked to both the physicochemical properties of each coating and the physiological changes associated with hen aging. These findings support our hypothesis that natural biofilms can preserve internal egg quality in aged hens, with whey protein being the most effective due to its semipermeable barrier properties.

Aging is known to reduce eggshell thickness and increase porosity because of the lower efficiency of shell gland cells in depositing calcium carbonate [

21]. These changes increase moisture loss and facilitate CO₂ diffusion, accelerating albumen alkalinization and protein liquefaction [

22,

23];. The relatively thin shell observed in fresh eggs in this study (0.36 mm), compared with the typical values of approximately 0.38–0.44 mm reported for younger hens, reflects this physiological decline [

24,

25]. Although fresh eggs initially presented satisfactory internal parameters, deterioration became evident during storage, supporting the role of shell porosity in accelerating quality loss [

26].

The Haugh unit is highly sensitive to storage, confirming that albumen degradation is the main indicator of quality loss [

14]. Whey-coated eggs maintained significantly higher HU values for up to 21 days. This effect can be attributed to the protein-based film forming a semipermeable barrier that reduces CO₂ loss, delaying the pH increase and preserving ovomucin integrity, which is essential for albumen viscosity [

27]. Similar effects were reported by Vale et al. [

14] in quail eggs coated with whey protein and garlic essential oil. Other protein-based coatings, such as rice protein, have also been shown to be effective at preserving internal egg quality [

17,

28,

29,

30].

The yolk index followed a similar pattern, with whey maintaining the best performance. Yolk weakening is associated with vitelline membrane rupture and water migration from the albumen to the yolk, processes accelerated by increased pH [

30]. The ability of whey coatings to delay these changes reinforces their semipermeable barrier function.

Aloe vera also has a positive effect, particularly within the first 7 days, which may be associated with its polysaccharides and bioactive compounds with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

13,

31]. However, its protective effect declined after 14 days, suggesting lower film stability or adherence.

Carnauba wax had intermediate results. Although it is recognized as an effective barrier against moisture and gas loss [

11,

12], its performance is less expressive than that of whey in preserving HU and YI. [

32] reported that carnauba wax coatings produced homogeneous but porous surfaces, limiting their sealing capacity compared with that of mineral oil. These findings suggest that the efficacy of carnauba wax depends on the formulation and shell characteristics.

The albumen pH results were consistent with those of previous reports [

31]. The progressive increase in CO₂ in control eggs reflects CO₂ diffusion, which is intensified by thinner shells in older hens [

21]. Whey and

Aloe vera coatings effectively reduce pH, corroborating studies on protein-, polysaccharide-, and lipid-based films that delay albumen alkalinization [

27,

29,

31]

Yolk color changed during storage and was affected by the coating treatment. The parameter b* progressively increased in all groups, reflecting an intensification of yolk yellowness and confirming the sensitivity of yolk color to storage conditions. Previous studies have reported similar changes in yolk color during storage, with variations in b* depending on specific conditions [

33,

34]. Compared with the control and carnauba wax, the whey and aloe vera coatings mitigated these changes, suggesting that the coatings can help maintain yolk color stability by preserving the yolk structure and moisture, likely through the sealing properties of whey and the antioxidant activity of

Aloe vera [

13,

14]. Eyng et al. [

11] reported that carnauba wax coatings, while effective at preserving internal egg quality, were less efficient at preventing oxidative changes, indicating that their protective effect relies primarily on water and CO₂ retention.

However, this study was conducted under a single room temperature condition and with eggs from a single flock of 86-week-old hens. Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these coatings under variable storage temperatures, industrial-scale conditions, and across different hen ages.

In addition, future studies could explore combinations of protein- and polysaccharide-based films, their antimicrobial effects, and sensory evaluation to optimize edible coatings for commercial applications.

Overall, whey protein and Aloe vera biofilms effectively mitigated quality deterioration in eggs from aged hens, suggesting their potential as sustainable and practical solutions for extending shelf-life while maintaining internal quality.

5. Conclusions

The evaluated biofilms significantly preserved the internal quality of eggs from 86-week-old hens stored at room temperature. Whey protein was the most effective coating, maintaining high Haugh unit and yolk index values, Aloe vera showed intermediate efficacy, and carnauba wax was less effective. These findings indicate that natural biofilms are a viable option for extending the shelf-life of eggs from hens at the end of the production cycle.

6. Patents

Not applicable

Author Contributions

Jhenifer Favacho: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, project administration, funding acquisition; Paulo Lima: Investigation, methodology, writing - review & editing; Isabela Milla: Investigation, methodology; Lucas Ferreira: Investigation, methodology; Vanessa Nunes: Investigation, methodology; Isabella de Souza: Investigation, methodology; Hirasilva Borba: Supervision, resources, project administration, writing – review & editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil), through a doctoral scholarship and research support (bench fee), grant number 141606/2023-1. The bench fee resources were used to purchase the whey protein, Aloe vera, and eggs required for the experimental procedures.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study did not involve live animals or human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions.

Declaration of generative ai- and ai-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI) only for spelling corrections and reference formatting. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alleoni, A.C.C.; Antunes, A.J. Perfil de Textura e Umidade Espremível de Géis Do Albume de Ovos Recobertos Com Soro de Leite. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2005, 25, 153–157. [CrossRef]

- Bain, M.M.; Nys, Y.; Dunn, I.C. Increasing Persistency in Lay and Stabilising Egg Quality in Longer Laying Cycles. What Are the Challenges? British Poultry Science 2016, 57, 330–338. [CrossRef]

- González-Morán, M.G. Changes in Progesterone Receptor Isoforms Expression and in the Morphology of the Oviduct Magnum of Mature Laying and Aged Nonlaying Hens. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 478, 999–1005. [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Kuehu, D.L.; Khadka, V.S.; Deng, Y.; Jha, R.; Wasti, S.; Mishra, B. RNA Sequencing-Based Analysis of the Magnum Tissues Revealed the Novel Genes and Biological Pathways Involved in the Egg-White Formation in the Laying Hen. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 318. [CrossRef]

- Lewko, L.; Krawczyk, J.; Calik, J. Effect of Genotype and Some Shell Quality Traits on Lysozyme Content and Activity in the Albumen of Eggs from Hens under the Biodiversity Conservation Program. Poultry Science 2021, 100, 100863. [CrossRef]

- Nowaczewski, S.; Lewko, L.; Kucharczyk, M.; Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Rudzińska, M.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Biadała, A.; Szulc, K.; Tomczyk, Ł.; Kaczmarek, S.; et al. Effect of Laying Hens Age and Housing System on Physicochemical Characteristics of Eggs. Annals of Animal Science 2021, 21, 291–309. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, J.; Lewko, L.; Sokołowicz, Z.; Koseniuk, A.; Kraus, A. Effect of Hen Genotype and Laying Time on Egg Quality and Albumen Lysozyme Content and Activity. Animals 2023, 13, 1611. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Musgrove, M.T. Effects of Extended Storage on Egg Quality Factors. Poultry Science 2005, 84, 1774–1777. [CrossRef]

- Rosser, F.T. Preservation Of Eggs: Ii. Surface Contamination On Egg-Shell In Relation To SpoilagE. Can. J. Res. 1942, 20d, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ramírez, G.S.; Velasco, J.I.; Plascencia, M.Á.; Absalón, Á.E.; Cortés-Espinosa, D.V. Development of Edible Coatings Based on Different Biopolymers to Enhance the Internal Shelf-Life Quality of Table Eggs. Coatings 2024, 14, 1525. [CrossRef]

- Eyng, C.; Nunes, K.C.; Matumoto-Pintro, P.T.; Vital, A.C.P.; Garcia, R.G.; Sanches, L.M.; Rohloff Junior, N.; Tenório, K.I. Carnauba Wax Coating Preserves the Internal Quality of Commercial Eggs during Storage. Semina: Ciênc. Agrár. 2021, 42, 1229–1244. [CrossRef]

- Piazentin MO; Mangili ELM; Correia DC; Martins EH; Nobre JAS; Córdoba GMC; Veríssimo CJ; Katiki LM; Rodrigues L Carnauba Wax Applied to the Shell Surface of Chicken Eggs Improved the Shelf Life and Internal Quality of the Eggs. Austin Journal of Nutrition and Food sciences 2023, 11, 08.

- Kilinç, G.; Köksal, M.; Seyrekoğlu, F. Evaluation of Some Parameters in Eggs Coated with Materials Prepared from Aloe Vera Gel and Chitosan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vale, I.R.R.; Oliveira, G.D.S.; McManus, C.; De Araújo, M.V.; Salgado, C.B.; Pires, P.G.D.S.; De Campos, T.A.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Almeida, A.P.C.; Martins, G.D.S.; et al. Whey Protein Isolate and Garlic Essential Oil as an Antimicrobial Coating to Preserve the Internal Quality of Quail Eggs. Coatings 2023, 13, 1369. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Pires, P.G.; Bavaresco, C.; Wirth, M.L.; Moraes, P.O. Egg Coatings: Trends and Future Opportunities for New Coatings Development. World’s Poultry Science Journal 2022, 78, 751–763. [CrossRef]

- Jurić, M.; Maslov Bandić, L.; Carullo, D.; Jurić, S. Technological Advancements in Edible Coatings: Emerging Trends and Applications in Sustainable Food Preservation. Food Bioscience 2024, 58, 103835. [CrossRef]

- Dilelis, F; Reis, T. L; Favacho, J. S. P Biofilmes Proteicos Para Manutenção Da Qualidade Interna de Ovos Caipiras Armazenados Em Temperatura Ambiente. XXI Congresso APA - Produção e Comercialização de Ovos, 2024, Ribeirão Preto - São Paulo. Anais... Ribeirão Preto - São Paulo. 2024, 26.

- Devi, L.S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Lipid Incorporated Biopolymer Based Edible Films and Coatings in Food Packaging: A Review. Current Research in Food Science 2024, 8, 100720. [CrossRef]

- Chiumarelli, M.; Hubinger, M.D. Evaluation of Edible Films and Coatings Formulated with Cassava Starch, Glycerol, Carnauba Wax and Stearic Acid. Food Hydrocolloids 2014, 38, 20–27. [CrossRef]

- Souza, H. B. A; Souza, P. A; Brognoni, E; Rocha, O. E Científica, São Paulo. 1994, pp. 217–226.

- Molnár, A.; Maertens, L.; Ampe, B.; Buyse, J.; Kempen, I.; Zoons, J.; Delezie, E. Changes in Egg Quality Traits during the Last Phase of Production: Is There Potential for an Extended Laying Cycle? British Poultry Science 2016, 57, 842–847. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, K.; Wu, S. The Change of Albumen Quality during the Laying Cycle and Its Potential Physiological and Molecular Basis of Laying Hens. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104004. [CrossRef]

- Tainika, B.; Şekeroğlu, A.; Akyol, A.; Şentürk, Y.; Abaci, S.; Duman, M. Effects of Age, Housing Environment, and Strain on Physical Egg Quality Parameters of Laying Hens. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2024, 26, eRBCA-2024-1911. [CrossRef]

- Yamak, U.; Sarica, M.; Boz, M.; Ucar, A. The Effect of Eggshell Thickness on Hatching Traits of Partridges. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2016, 18, 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; McDaniel, C.D.; Kiess, A.S.; Loar, R.E.; Adhikari, P. Effect of Housing Environment and Hen Strain on Egg Production and Egg Quality as Well as Cloacal and Eggshell Microbiology in Laying Hens. Poultry Science 2022, 101, 101595. [CrossRef]

- Qiang, T.; Zhang, K.; Zeng, Q.; Ding, X.; Bai, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Xuan, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Comparative Analysis of Intestinal and Reproductive Function in Older Laying Hens with Three Egg Laying Levels. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1582516. [CrossRef]

- Mardewi, N.K.; Suriati, L.; Defy Janurianti, N.M. Effect of Aloe-Coating Application on Quail Egg Quality During Storage. JAC 2023, 384–390. [CrossRef]

- Pires, P.G.S.; Leuven, A.F.R.; Franceschi, C.H.; Machado, G.S.; Pires, P.D.S.; Moraes, P.O.; Kindlein, L.; Andretta, I. Effects of Rice Protein Coating Enriched with Essential Oils on Internal Quality and Shelf Life of Eggs during Room Temperature Storage. Poultry Science 2020, 99, 604–611. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.D.S.; McManus, C.; Salgado, C.B.; Pires, P.G.D.S.; De Figueiredo Sousa, H.A.; Da Silva, E.R.; Dos Santos, V.M. Antimicrobial Coating Based on Tahiti Lemon Essential Oil and Green Banana Flour to Preserve the Internal Quality of Quail Eggs. Animals 2023, 13, 2123. [CrossRef]

- De Araújo, M.V.; Oliveira, G.D.S.; McManus, C.; Vale, I.R.R.; Salgado, C.B.; Pires, P.G.D.S.; De Campos, T.A.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Almeida, A.P.C.; Martins, G.D.S.; et al. Preserving the Internal Quality of Quail Eggs Using a Corn Starch-Based Coating Combined with Basil Essential Oil. Processes 2023, 11, 1612. [CrossRef]

- Radev, R. EDIBLE COATINGS FOR EGGS. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kuster B.; Aline F. S. B; Pabst J. A. Microscopia eletrônica de varredura da casca de ovos comerciais cobertos com óleo mineral, cera de carnaúba e quitosana. Revista Ambientes em Movimento. December 2024.

- Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Yum, K.H.; Lee, W.T.; Park, S.H.; Lim, Y.H.; Choi, N.Y.; Jang, S.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, J.H. Effects of Storage Temperature and Egg Washing on Egg Quality and Physicochemical Properties. Discov Appl Sci 2024, 6, 111. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.; Özdemir, H.H.; Gökkaya Erdem, B. Physical Changes in Hen Eggs Stored at Different Temperatures. Food Health 2024, 10, 253–261. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).