Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

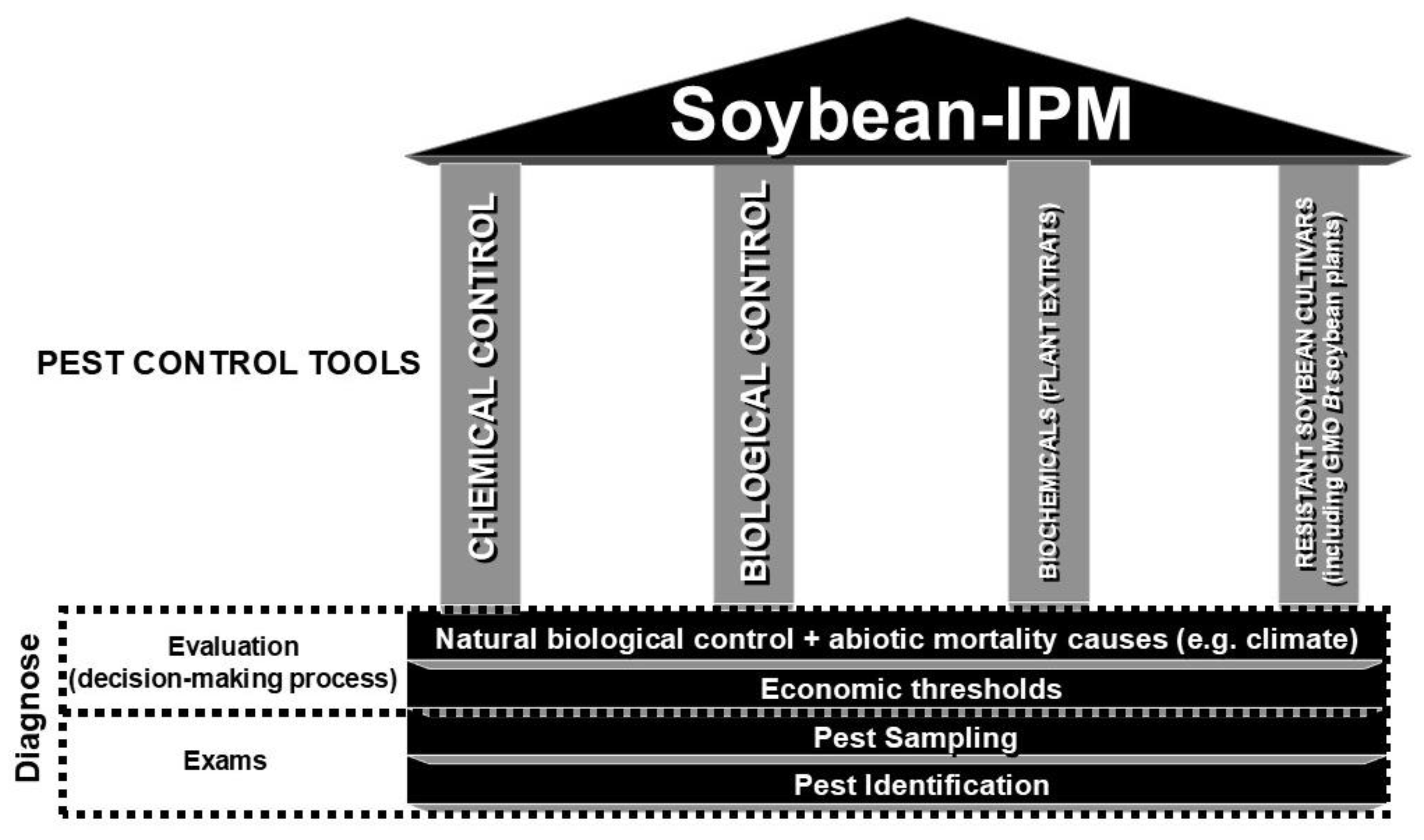

2. Soybean-IPM: A Successful Case Study from the State of Paraná, Brazil

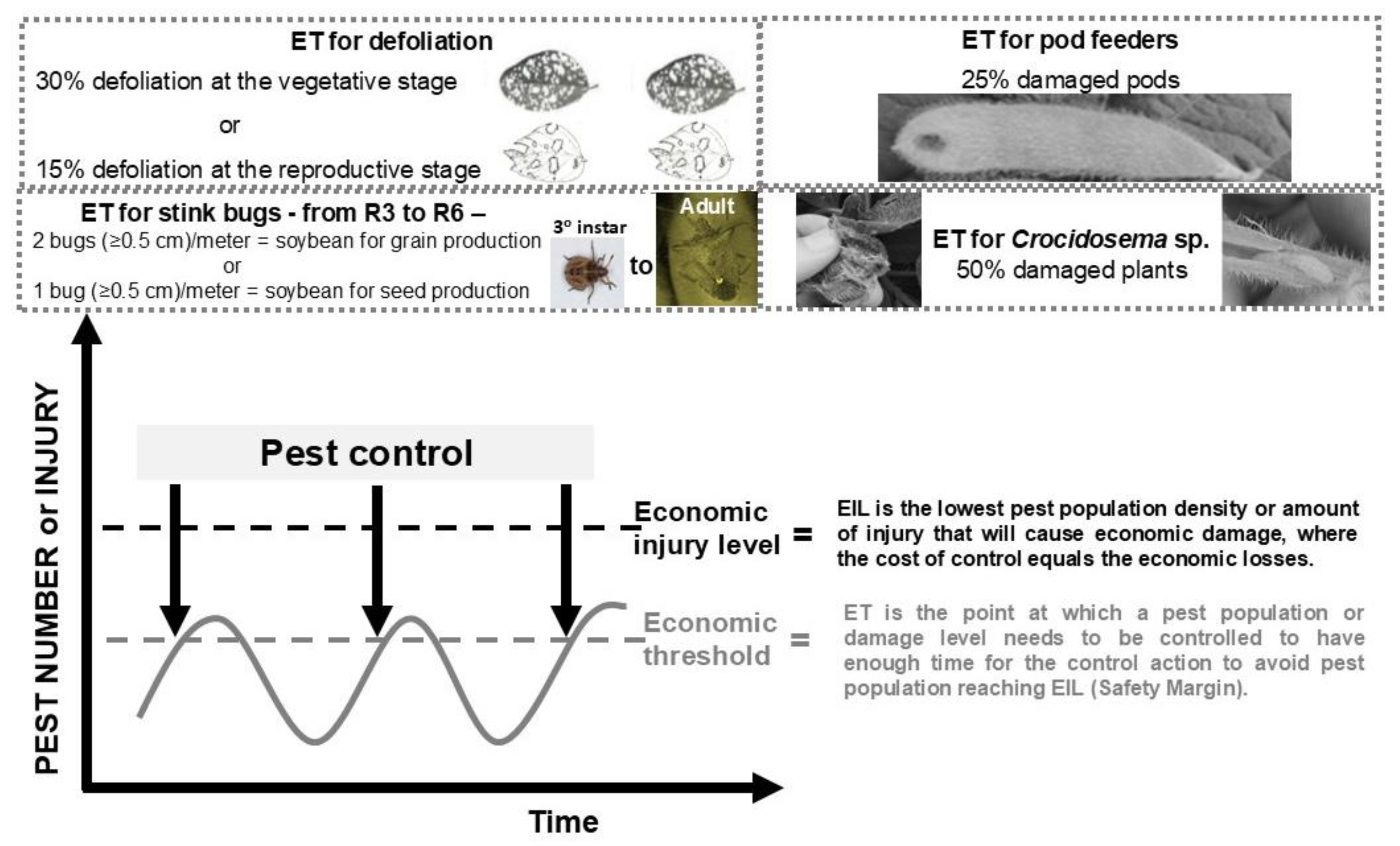

3. Use of Economic Thresholds (ETs) in Soybean-IPM

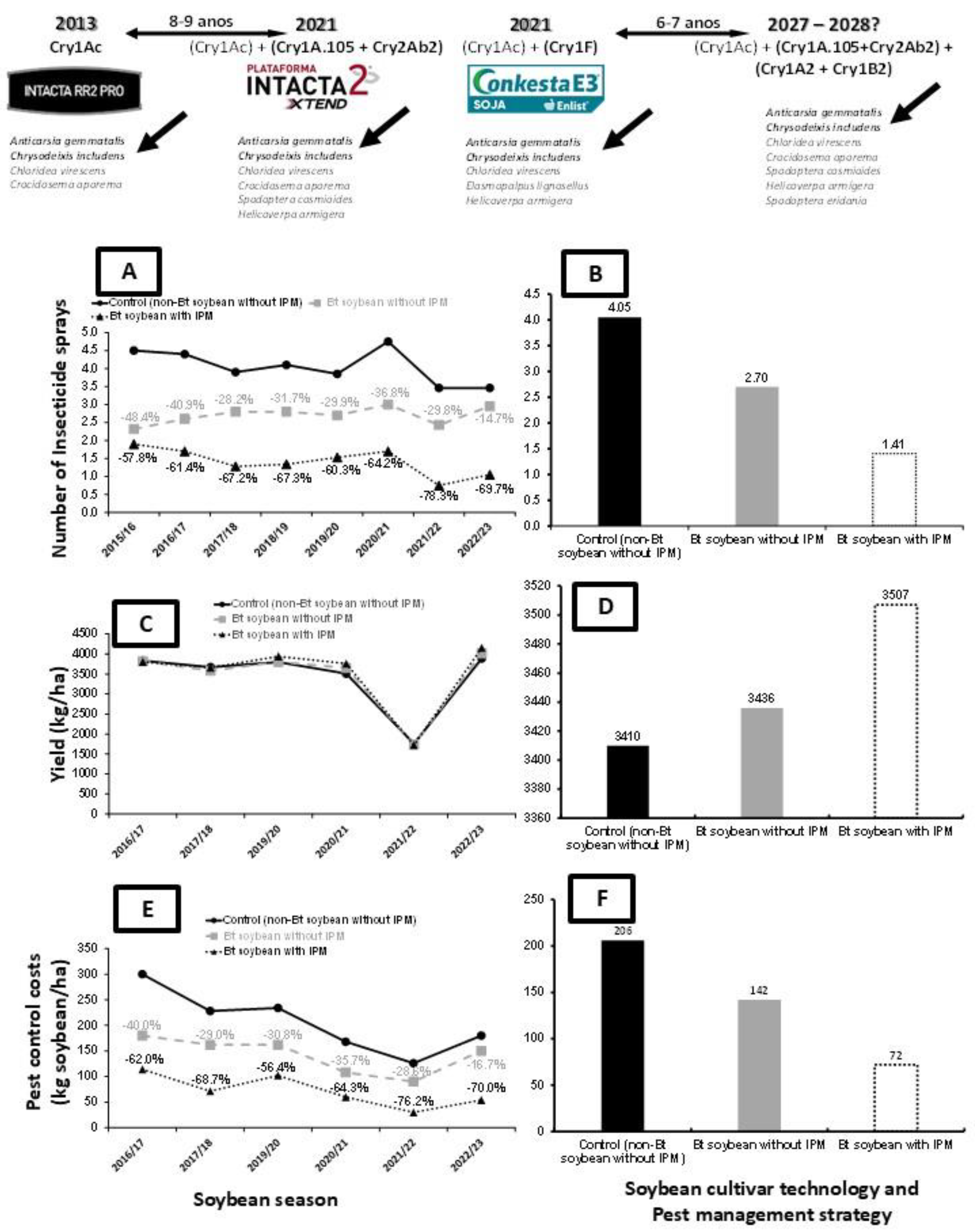

4. Use of Bt Cultivars in Soybean-IPM

5. Role of Biological Control in Soybean-IPM

6. Opportunities for Increasing the Adoption of Soybean-IPM

7. Final Considerations and Future Perspectives of Soybean-IPM

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamza, M.; Basit, A.W.; Shehzadi, I.; Tufail, U.; Hassan, A.; Hussain, T.; Siddique, M.U.; Hayat, H.M. Global impact of soybean production: A review. Asian Journal of Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology 2024, 16, 12–20. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Anokhe, A.; Duraimurugan, P. A brief overview of pest complex in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merill] and their management. Journal of Oilseeds Research 2023, 40, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- SoyStats. A reference guide to important soybean facts & figures. The American Soybean Association, 2025. Available at: https://soystats.com/2024-soystats/ Accessed November 1, 2025.

- Jiang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Li, Q. The research progress and frontier studies on soybean production technology: Genetic breeding, pest and disease control, and precision agriculture applications. Adv. Resour. Res. 2025, 5, 1065–1082. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, N.; Mogalapu, S. Pests of Soybean. In: Omkar (Ed.). Pests and Their Management. Springer, Singapore, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Abudulai, M.; Salifu, A.B.; Opare-Atakora, D.; Haruna, M.; Denwar, N.N.; Baba, I.I.Y. Yield loss at the different growth stages in soybean due to insect pests in Ghana. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2012, 45, 1796–1809. [CrossRef]

- Musser, F.R.; Bick, E.; Brown, S.A.; et al. 2023 Soybean Insect Losses in the United States. Midsouth Entomol. 2023, 17, 6–30. Available at: https://www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu/ Consulted at: 01/11/2025.

- Saldanha, A.V.; Horikoshi, R.; Dourado, P.; Lopez-Ovejero, R.F.; Berger, G.U.; Martinelli, S.; Head, G.P.; Moraes, T.; Corrêa, A.S.; Schwertner, C.F. The first extensive analysis of species composition and abundance of stink bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) on soybean crops in Brazil. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 3945-3956. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Guru-Pirasanna-Pandi, G.; Murtaza, G.; et al. Evolving strategies in agroecosystem pest control: transitioning from chemical to green management. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 2307–2324. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Colmenarez, Y.C.; Carnevalli, R.A.; Sutil, W.P. Benefits and perspectives of adopting soybean-IPM: the success of a Brazilian programme. Plant Health Cases 2023a, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, T.; Hussain, A.; Xia, X.; Shang, Q.; Ali, A. The side effects of insecticides on insects and the adaptation mechanisms of insects to insecticides. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1287219. [CrossRef]

- Mali, H.; Shah, C.; Raghunandan, B.H.; et al. Organophosphate pesticides: an emerging environmental contaminant: pollution, toxicity, bioremediation progress, and remaining challenges. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 127, 234–250. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Panizzi, A.R.; Hunt, T.E.; Dourado, P.M.; Pitta, R.M.; Gonçalves, J. Challenges for adoption of integrated pest management (IPM): the soybean example. Neotrop. Entomol. 2021, 50, 5–20. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Kraemer, B.; et al. Prevalence, damage, management and insecticide resistance of stink bug populations (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in commodity crops. Agric. Forest Entomol. 2020, 22, 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.F.; Otesbelgue, A.; Blochtein, B. The dilemma of agricultural pollination in Brazil: Beekeeping growth and insecticide use. Plos One, 2018, 13, e0200286. [CrossRef]

- Lisi, F.; Siscaro, G.; Biondi, A.; Zappalà, L.; Ricupero, M. Non-target effects of bioinsecticides on natural enemies of arthropod pests. Current Opinion in Environmental Sci. Health 2025, 45, 100624. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, M.; Achal, V. A comprehensive review on environmental and human health impacts of chemical pesticide usage. Emerging Contaminants 2025, 11, 100410. [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, F.; Jeuffroy, M.H.; Jouan, J.; et al. Pesticide-free agriculture as a new paradigm for research. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; den Uyl, R.; Runhaar, H. Assessment of policy instruments for pesticide use reduction in Europe: Learning from a systematic literature review. Crop Protec. 2019, 126, 104929. [CrossRef]

- Dara, S.K.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Morrison III, W.R. Editorial: Integrated pest management strategies for sustainable food production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1224604. [CrossRef]

- Dara, S.K. The new integrated pest management paradigm for the modern age. J. Int. Pest Manag. 2019, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A. Safe food production with minimum and judicious use of pesticides. In: Selamat, J.; Iqbal, S. (Eds.). Food Safety. Springer, Cham, 2016, pp. 43–55. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.L.; Peluzio, J.M.; Picanço, M.C.; Sarmento, R.A. Integrated pest management of soybean emerging pests in Brazil and United States: a review. Concilium 2024, 24, 0010-5236.

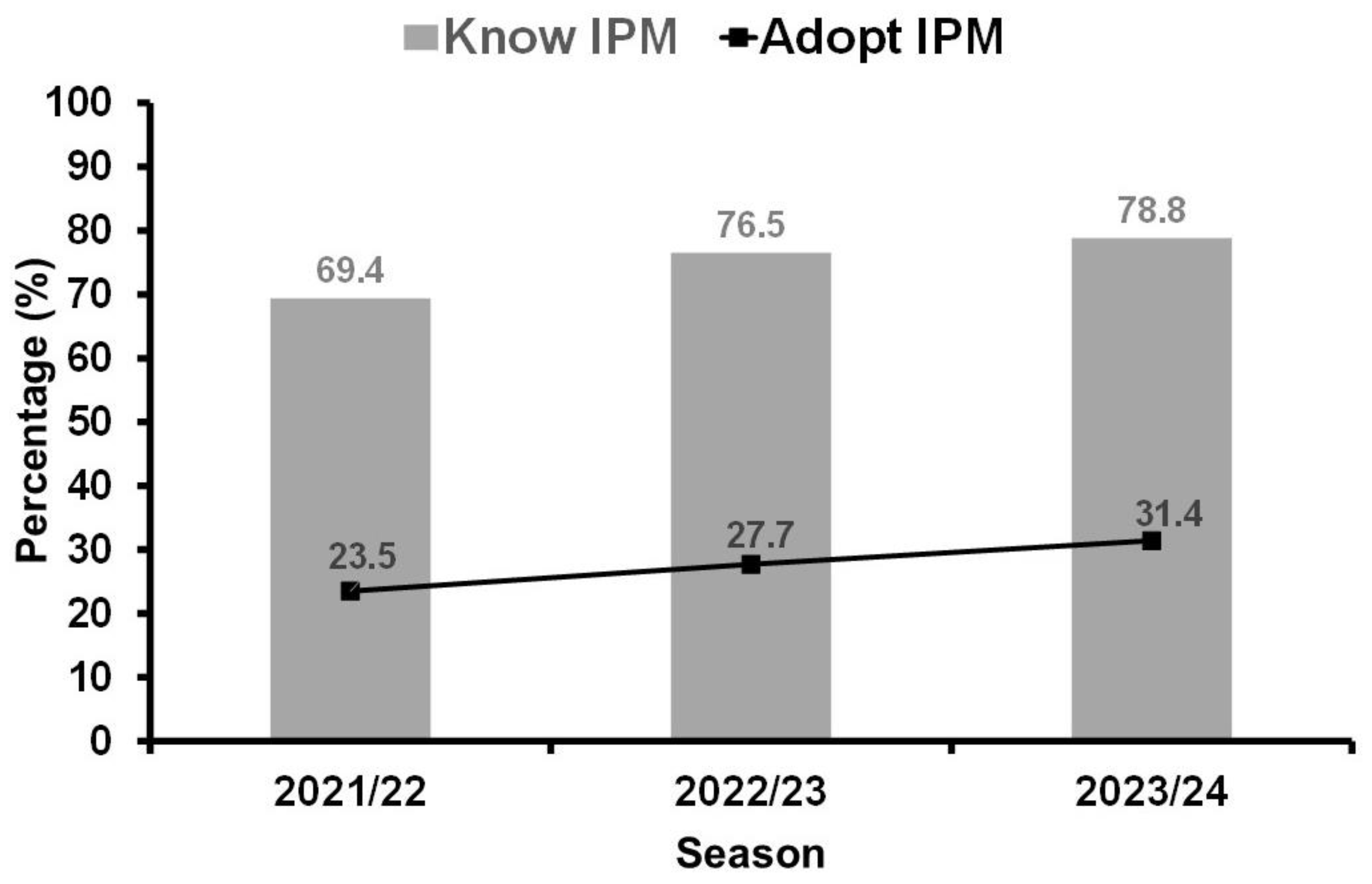

- Carnevalli, R.A.; Oliveira, A.B.; Gomes, E.C.; Possamai, E.J., Silva, G.C.; Reis, E.A.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Lima, D. Resultados do manejo integrado de pragas da soja na safra 2021/2022 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 448 2022, 1-43.

- Carnevalli, R.A.; Prando, A.M.; Lima, D.; Borges, R.S.; Possamai, E.J.; Silva, G.C.; Reis, E.A.; Gomes, E.C.; Silva, G.C.; Roggia, S. Resultados do manejo integrado de pragas da soja na safra 2022/2023 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 455 2023, 1-44.

- Carnevalli, R.A.; Prando, A.M.; Lima, D.; Borges, R.S.; Possamai, E.J.; Reis, E.A.; Gomes, E.C.; Roggia, S. Resultados do manejo integrado de pragas da soja na safra 2023/2024 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 467 2024, 1-51.

- Panizzi, A.R. History and contemporary perspectives of the integrated pest management of soybean in Brazil. Neotrop. Entomol. 2013, 42, 119–127. [CrossRef]

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2013/14 no Paraná. Londrina, EMBRAPA-CNPSo, Documentos 356 2014, 1-53.

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2014/15 no Paraná. Londrina, EMBRAPA-CNPSo, Documentos 361 2015, 1-60.

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Seratto, C.D. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2015/16 no Paraná. Londrina, EMBRAPA-CNPSo, Documentos 375 2016, 1-59.

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Seratto, C.D. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2016/17 no Paraná. Londrina, EMBRAPA-CNPSo, Documentos 394 2017, 1-70.

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Seratto, C.D. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2017/18 no Paraná. Londrina, EMBRAPA-CNPSo, Documentos 402 2018, 1-66.

- Conte, O.; Oliveira, F.T.; Harger, N.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Possmai, E.J.; Reis, E.A.; Marx, E.F. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2018/19 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 416 2019, 1-63.

- Conte, O.; Possamai, E.J.; Silva, G.C.; Reis, E.A.; Gomes, E.C.; Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M. Resultados do Manejo Integrado de Pragas da Soja na safra 2019/20 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 431 2020, 1-66.

- Oliveira, A.B.; Gomes, E.C.; Possamai, E.J.; Silva, G.C.; Reis, E.A.; Roggia, S.; Prando, A.M.; Conte, O. Resultados do manejo integrado de pragas da soja na safra 2020/2021 no Paraná. Embrapa Soja, Londrina, Documentos 443 2022, 1-68.

- Norton, G.W.; Moore, K.; Quishpe, D.; et al. Evaluating Socio-Economic Impacts of IPM. In: Norton, G.W.; Heinrichs, E.A.; Luther, G.C.; Irwin, M.E. (Eds.). Globalizing Integrated Pest Management: A Participatory Research Process 2005, 223–244. [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Swinton, S.M. Returns to Integrated Pest Management Research and Outreach for Soybean Aphid. Journal of Economic Entomology 2009, 102, 2116–2125. [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.J.; Vessoni, I.C.; Silva, I.F.; Vieira, E.C.S.; Mariani, A.; Moreira, S.C.S. IPM in soybeans: how to reduce crop damage and increase profit for the farmer. Ver. Agric. Neotrop. 2024, 11, e8214. [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, S.S.; Dupare, B.U. Monetary benefits of integrated pest management in soybean [Glycine max (L) Merrill] cultivation. Soybean Research 2019, 17, 89–94. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/SsenthilVinayagam/publication/370872196_Monetary_Benefits_of_Integrated_Pest_Management_in_Soyabean_Glycine_max_L_Merill_Cultivation/links/646727d5c9802f2f72e81724/Monetary-Benefits-of-Integrated-Pest-Management-in-Soyabean-Glycine-max-L-Merill-Cultivation.pdf.

- Mariyono, J. The impact of integrated pest management technology on insecticide use in soybean farming in Java, Indonesia: Two models of demand for insecticides. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development 2008, 5. Available at: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/198979/.

- Bueno, A.F.; Paula-Moraes, S.V.; Gazzoni, D.L.; Pomari, A.F. Economic thresholds in soybean integrated pest management: old concepts, current adoption, and adequacy. Neotrop. Entomol. 2013, 42, 439–447. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Sperandio, G.; Caffi, T.; Simonetto, A.; Gilioli, G. Critical success factors for the adoption of decision tools in IPM. Agronomy 2019, 9, 710. [CrossRef]

- Higley, L.G.; Peterson, R.K.D. The biological basis of the EIL. In: Higley, L.G.; Pedigo, L.P. (Eds.). Economic threshold for integrated pest management. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London, 1996, 327 p.

- Batistela, M.J.; Bueno, A.F.; Nishikawa, M.A.N.; Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Hidalgo, G.; Silva, L.; Corbo, E.; Silva, R.B. Re-evaluation of leaf-lamina consumer thresholds for IPM decision in short-season soybeans using artificial defoliation. Crop Protec. 2012, 32, 7-11. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Bortolotto, O.C.; Pomari-Fernandes, A.; França-Neto, J.B. Assessment of a more conservative stink bug economic threshold for managing stink bugs in Brazilian soybean. Crop Protec. 2015, 71, 132-137, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.012.

- Justus, C.M.; Paula-Moraes, S.V.; Pasini, A.; Hoback, W.W.; Hayashida, R.; Bueno, A.F. Simulated soybean pod and flower injuries and economic thresholds for Spodoptera eridania (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) management decisions. Crop Protect. 2022, 155, 105936. [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, R.; Hoback, W.W.; Dourado, P.M.; Bueno, A.F. Re-evaluation of the economic threshold for Crocidosema aporema injury to indeterminate Bt soybean cultivars. Agronomy Journal 2023, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Pedigo, L.P.; Rice, M.E. Entomology and pest management, 6th ed. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2009, xxvii + 749 p.

- Pedigo, L.P.; Rice, M.E.; Krell, R.K. Entomology and pest management. Waveland Press, 2021.

- Ragsdale, D.W.; Mccornack, B.P.; Venette, R.C.; Potter, B.D.; V. Macrae, V.; Hodgson, E.W.; O’neal, M.E.; Johnson, K.D.; O’neil, R.J.; Difonzo, C.D.; Hunt, T.E.; Glogoza, P.A.; Cullen, E.M. Economic threshold for soybean aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100: 1258Ð1267. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.S.; Lourenção, A.L.; da Graça, J.P.; Janegitz, T.; Salvador, M.C.; Oliveira, M.C.N.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B. Biological aspects of Bemisia tabaci biotype B and the chemical causes of resistance in soybean genotypes. Arthropod-Plant Interac. 2016, 10, 525–534. [CrossRef]

- Padilha, G.; Pozebon, H.; Patias, L.S.; Ferreira, D.R.; Castilhos, L.B.; Forgiarini, S.E.; Donatti, A.; Bevilaqua, J.G.; Marques, R.P.; Moro, D.; Rohrig, A.; Bones, S.A.S.; Cargnelutti Filho, A.; Pes, L.Z.; Arnemann, J.A. Damage assessment of Bemisia tabaci and economic injury level on soybean. Crop Protec. 2021, 143, 105542. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Daves, C.; Koger, T.; et al. Insect control guides for cotton, soybeans, corn, grain sorghum, wheat, sweet potatoes & pastures. Mississippi State University Extension Service, {S.l.}, 2009, 64 p.

- Seiter, N.J.; Decker, A.L.; Kelley J Tilmon, K.J.; McCornack, B.; Krupke, C.; DiFonzo, C.; Knodel, J. Soybean defoliation estimation methods and thresholds in the North Central United States. J. Econ. Entomol. 2025, toaf288, . [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.P.; Cook, D.R.; Catchot, A.L.; Gore, J.; Musser, F.; Stewart, S.D.; Kerns, D.L.; Lorenz, G.M.; Irby, J.T.; Golden, B. Evaluation of corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), economic injury levels in Mid-South reproductive stage soybean. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1161–1166. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Bueno, A.F.; Moscardi, F.; Parra, J.R.P.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B. Lepidopteran larvae consumption of soybean foliage: basis for developing multiple-species economic thresholds for pest management decisions. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 170-174. [CrossRef]

- Kalmosh, F.S. Economic threshold and economic injury levels for the two spotted spider mite Tetranychus cucurbitacearum (Sayed) on soybean. Annals of Agric. Sci. Moshtohor 2016, 54. Available at: http://annagricmoshj.com Accessed November 14, 2025.

- Hall, D.C. The regional economic threshold for integrated pest management. Nat. Resour. Model. 1988, 2, 631–652.

- Vieira, S.S.; Bueno, R.C.O.F.; Bueno, A.F.; Boff, M.I.C.; Gobbi, A.L. Different timing of whitefly control and soybean yield. Ciência Rural 2013, 43, 247-253. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, S.E.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Chu, C.C.; Henneberry, T.J.; Riley, D.G.; Watson, T.F.; Nichols, R.L. Action Thresholds for the Management of Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) in Cotton. J. Econo. Entomol. 1998, 91, 1415-1426. [CrossRef]

- Onstad, D.W.; Bueno, A.F.; Favetti, B.M. Economic Thresholds and sampling in Integrated Pest Management. In: The economics of Integrated Pest Management of insects, ed. 1. CABI, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, UK, 2019, v. 1, pp. 122–139. [CrossRef]

- Krisnawati, A.; Adie, M.M. The leaflet shape variation from several soybean genotypes in Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2017, 18, 359–364. [CrossRef]

- Padilha, G.; Fiorin, R.A.; Filho, A.C.; et al. Damage assessment and economic injury level of the two-spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae in soybean. Pesq. Agropec. Brasileira 2020, 55, e01836. [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.V.C.; Lopes, M.C.; Sarmento, R.A.; Pereira, P.S.; Pires, W.S.; Peluzio, J.M.; Picanço, M.C. Economic injury levels for control decision-making of thrips in soybean crops (Glycine max (L.) Merrill). Res., Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e52411932114. http://dx.doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v11i9.32114.

- Leach, A.; Gomez, A.A.; Kaplan, I. Threshold-based management reduces insecticide use by 44% without compromising pest control or crop yield. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 710. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.; Popp, I. Migrants and Cities: Stepping Beyond World Migration Report 2015. In: World Migration Report 2018. IOM, Geneva. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2018_en_chapter10.pdf.

- Hoidal, N.; Koch, R.L. Perception and use of Economic Thresholds among farmers and agricultural professionals: A case study on soybean aphid in Minnesota. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2021, 12, 9, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Mariyono, J. The impact of IPM training on farmers’ subjective estimates of economic thresholds for soybean pests in central Java, Indonesia. International J. Pest Manag. 2007, 53, 83–87. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Jasrotia, P.; Kumar, D.; et al. Biotechnological approaches for host plant resistance to insect pests. Front. in Genetics 2022, 13, 914029. [CrossRef]

- Warghat, A.N.; Kumar, A.; Raghuvanshi, H.R.; Aman, A.S.; Kumar, A. Recent advancements in plant protection. In: Kumar, N.; Purushotham, P.; Kumar, A.; Sahu, A.; Nandeesha, S.V. (Eds.). Recent advances in plant protection. Golden Leaf Publishers, Uttar Pradesh, 2023, pp. 1–25.

- Baldin, E.L.L.; Vendramim, J.D.; Lourenção, A.L. Introdução a resistência de plantas a insetos: fundamentos e aplicações. In: Resistência de Plantas a Insetos: Fundamentos e Aplicações. FEALQ, Piracicaba, 2019, pp. 1–493.

- Martins-Salles, S.; Machado, V.; Massochin-Pinto, L.; Fiuza, L.M. Genetically modified soybean expressing insecticidal protein (Cry1Ac): Management risk and perspectives. Facets 2017, 2, 496–512. [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, S.E. Effects of GE Crops on Non-target Organisms. In: Ricroch, A.; Chopra, S.; Kuntz, M. (Eds.). Plant Biotechnology. Springer, Cham, 2021, pp. 127–144. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Braz-Zini, E.C.; Horikoshi R.J.; Bernardi, O.; Andrade, G.; Sutil, W.P. Over 10 years of Bt soybean in Brazil: lessons, benefits, and challenges for its use in Integrated Pest Management (IPM). Neotrop. Entomol. 2025, 54, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications) (2018) Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2018. ISAAA Brief 54. Available at: https://www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/briefs/54/ (Accessed October 24, 2024).

- Brookes, G.; Barfoot, P. Environmental impacts of genetically modified (GM) crop use 1996–2016: impacts on pesticide use and carbon emissions. GM Crops & Food 2018, 9, 109–139. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, E.; Bedini, S.; Nuti, M.; Ercoli, L. Impact of genetically engineered maize on agronomic, environmental and toxicological traits: A meta-analysis of 21 years of field data. Scient. Reports 2018, 8, 3113. [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.R.A.; Filho, J.B.D.S.F.; Silveira, J.M.F.J.D.; Costa, M.S.D.; Osaki, M.; Lima, F.F.D.; Ribeiro, R.G. Genetically modified corn adoption in Brazil, costs and production strategy: Results from a four-year field survey. Revista de Economia e Agronegócio 2020, 18, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.D.; Ciliberto, F.; Hennessy, D.A.; Moschini, G. Genetically engineered crops and pesticide use in U.S. maize and soybeans. Sci. Advan. 2016, 2, e1600850. [CrossRef]

- Romeis, J.; Naranjo, S.E.; Meissle, M.; Shelton, A.M. The role of Bt crops in integrated pest management programs. Biocontrol 2019, 64, 611–617.

- Marques, L.H.; Santos, A.C.; Castro, B.A.; et al. Impact of transgenic soybean expressing Cry1Ac and Cry1F proteins on the non-target arthropod community associated with soybean in Brazil. Plos One 2018, 13, e0191567. [CrossRef]

- Rousset, R.; Gallet, A. Unintended effects of Bacillus thuringiensis spores and Cry toxins used as microbial insecticides on non-target organisms. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 100598, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Reisig, D.D.; Huseth, A.S.; Bacheler, J.S.; et al. Long-term empirical and observational evidence of practical Helicoverpa zea resistance to cotton with pyramided Bt toxins. J. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 1824–1833. [CrossRef]

- Tabashnik, B.E.; Carrière, Y. Global patterns of resistance to Bt crops highlighting pink bollworm in the United States, China, and India. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 2513–2523. [CrossRef]

- Horikoshi, R.J.; Bernardi, O.; Godoy, D.N.; et al. Resistance status of lepidopteran soybean pests following large-scale use of MON 87701 × MON 89788 soybean in Brazil. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 21323. [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, E.A.; Reis, A.C.; Palharini, R.B.; et al. Characterization of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in Crocidosema sp. (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) from Brazil. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 3066–3073. [CrossRef]

- Jerez, P.G.P.; Otero, J.; González, M. Ten years of Cry1Ac Bt soybean use in Argentina: Historical shifts in the community of target and non-target pest insects. Crop Protec. 2023, 170, 106265. [CrossRef]

- Murúa, M.G.; Vera, M.A.; Herrero, M.I.; Fogliata, S.V.; Michel, A. Defoliation of soybean expressing Cry1Ac by lepidopteran pests. Insects 2018, 9, 93. [CrossRef]

- Giraudo, W.G.; Figueruelo, A.M.; Trumper, E.V. Effects of Bt soybean on biodiversity are limited to target species and host-specific parasitoids in La Pampa province, Argentina. Rev. de invest. Agropec. 2024, 50, 112-129.

- Lorente, J.; Vassallo, M.; García Suárez, F. Economic and environmental impacts of stacked transgenic events on soybean and corn. Agrociencia Uruguay 2025, 29, e1323, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- CIB (Conselho de Informações sobre Biotecnologia). 20 anos de transgênicos: impactos ambientais, econômicos e sociais no Brasil. 2018, 20 p. Available at: https://agroavances.com/img/publicacion_documentos/153575459920-anos-de-transgenicos-no-brasil.pdf Accessed November 15, 2025.

- Denning, G. Sustainable intensification of agriculture: the foundation for universal food security. npj Sust. Agric. 2025, 3, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.S.; Medina, R.F. Agriculture sows pests: how crop domestication, host shifts, and agricultural intensification can create insect pests from herbivores. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. Intensification for redesigned and sustainable agricultural systems. Science 2018, 362, eaav0294. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; et al. Soybean genetic resources contributing to sustainable protein production. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4095–4121. [CrossRef]

- Dukariya, G.; Shah, S.; Singh, G.; Kumar, A. Soybean and Its Products: Nutritional and Health Benefits. J. Nut. Sci. Heal. Diet 2020, 1, 22–29. Available at: https://journalofnutrition.org Accessed November 15, 2025.

- Andreata, F.L.; Mian, S.; Andrade, G.; Bueno, A.F.; et al. The current increase and future perspectives of the microbial pesticides market in agriculture: the Brazilian example. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1574269. [CrossRef]

- Fenibo, E.O.; Ijoma, G.N.; Matambo, T. Biopesticides in Sustainable Agriculture: A Critical Sustainable Development Driver Governed by Green Chemistry Principles. Front. Sustain. Food Systems 2021, 5. [CrossRef]

- Marrone, P.G. Status of the biopesticide market and prospects for new bioherbicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.F.; Sutil, W.P.; Jahnke, S.M.; et al. Biological control as part of the soybean integrated pest management (IPM): Potential and challenges. Agronomy 2023b, 13, 2532. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, S.; Bhavana, P.; Padhan, E.K. Insecticide resistance and management strategies. In: Dash, S.S.; Pradhan, P.P.; Sahoo, S.; Nag, Y.K.; Sorahia, D. (Eds). Advan. Applied Entomol. 2025, 184-208. [CrossRef]

- Perini, C.R.; Tabuloc, C.A.; Chiu, J.C.; et al. Transcriptome analysis of pyrethroid-resistant Chrysodeixis includens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) reveals overexpression of metabolic detoxification genes. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 274–283. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Moscardi, F. Seasonal occurrence and host spectrum of egg parasitoids associated with soybean stink bugs. Bio. Control 1995, 5, 196–202. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, K.K.; Andow, D.A. Lady beetle (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) communities in soybean and maize. Environ. Entomol. 2016, 45, 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Noma, T.; Brewer, M.J. Seasonal abundance of resident parasitoids and predatory flies and corresponding soybean aphid densities, with comments on classical biological control of soybean aphid in the Midwest. J. Econ. Entomol. 2008, 101, 278–287. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Gómez, D.R.; Delpin, K.E.; Moscardi, F.; Farias, J.R. Natural occurrence of the entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium, Beauveria and Paecilomyces in soybean under till and no-till cultivation systems. Neotrop. Entomol. 2001, 30, 407–410.

- Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Pollato, S.L.B. Biology and consumption of predator Callida sp. (Coleoptera: Carabidae) reared on Anticarsia gemmatalis Hübner, 1818. Pesquisa Agropec. Brasileira 2014, 24, 923–927.

- Silva, G.V.; Bueno, A.F.; Neves, P.M.O.J.; Favetti, B.M. Biological characteristics and parasitism capacity of Telenomus podisi (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae) on eggs of Euschistus heros (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Agricult. Sci. 2018, 10, 210–220. [CrossRef]

- Taguti, E.A.; Goncalvez, J.; Bueno, A.F.; Marchioro, S.T. Telenomus podisi parasitism on Dichelops melacanthus and Podisus nigrispinus eggs at different temperatures. Flo. Entomol. 2019, 102, 607–613. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.Z.; Tariq, T.; Shen, Z.; et al. Eri silkworm eggs as a superior factitious host for mass rearing Trichogramma leucaniae, the key natural enemy of soybean pod borer. Biological Control 2025, 105860.

- Corrêa-Ferreira, B.S.; Hoffmann-Campo, C.B.; Sosa-Gómez, D.R. Inimigos naturais de Helicoverpa armigera em soja. Comunicado Técnico Embrapa Soja 80. Londrina, 2014, 12 p. Available at: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-publicacoes/-/publicacao/992733/inimigos-naturais-de-helicoverpa-armigera-em-soja Accessed November 15, 2025.

- van Lenteren, J.C.; Bolckmans, K.; Köhl, J.; Ravensberg, W.J.; Urbaneja, A. Biological control using invertebrates and microorganisms: plenty of new opportunities. BioControl 2018, 63, 39–59. [CrossRef]

- Horne, P.A.; Page, J.; Nicholson, C. When will integrated pest management strategies be adopted? Example of the development and implementation of integrated pest management strategies in cropping systems in Victoria. Australian J. Experimen. Agric. 2008, 48, 1601–1607. [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, L.M.; Torres, J.B.; Abram, P.K.; et al. Insect biological control: a global perspective. Entomol. Generalis 2025, 45, 879–904. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmanović, D. Sustainable development in agriculture with a focus on decarbonization. West. Balk. J. Agric. Econom. 2023, 5, 163-177. [CrossRef]

- Khatri Chhetri, A.; Junior, C.; Wollenberg, E. Greenhouse gas mitigation co-benefits across the global agricultural development programs. Global Environ. Change 2022, 76, 102586. [CrossRef]

- USDE. Industrial Decarbonization Roadmap. Document no. DOE/EE-2635, United States Department of Energy, Washington, USA, 2022. Available at: www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/Industrial%20Decarbonization%20Roadmap.pdf Accessed November 15, 2025.

- EMBRAPA. Brazil defines guidelines for certifying low-carbon soybean. 2024. Available at: https://www.brazilianfarmers.com/news/brazil-defines-guidelines-for-certifying-low-carbon-soybean/ Accessed November 15, 2025.

- ANPIIBIO (Associação Nacional de Promoção e Inovação da Indústria de Biológicos). Estatística 2024. Available at: https://anpiibio.org.br/estatisticas/ Accessed 15 November 2025.

|

Soybean season |

Number of fields |

Number of sprays (insecticides) |

Days until first insecticide spray |

Pest control costs2 (kg/ha) |

Yield (kg/ha) |

Increased profits2,3 (kg/ha) |

|||||

| Adopter | Non-Adopter | Adopter | Non-Adopter | Adopter | Non-Adopter | Adopter | Non-Adopter | Adopter | Non-Adopter | ||

| 2013/14 | 46 | 333 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 57.5 | 33.0 | 144 | 302 | 2952 | 2922 | 186 |

| 2014/15 | 106 | 330 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 66.0 | 34.0 | 120 | 300 | 3612 | 3516 | 276 |

| 2015/16 | 123 | 314 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 66.8 | 36.0 | 120 | 240 | 3426 | 3282 | 264 |

| 2016/17 | 141 | 390 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 70.8 | 40.5 | 138 | 246 | 3870 | 3828 | 150 |

| 2017/18 | 196 | 615 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 78.7 | 43.6 | 138 | 324 | 3702 | 3630 | 258 |

| 2018/19 | 241 | 773 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 74.0 | 40.3 | 126 | 246 | 3006 | 2916 | 210 |

| 2019/20 | 255 | 553 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 75.0 | 56.0 | 108 | 186 | 3864 | 3804 | 138 |

| 2020/21 | 191 | 518 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 76.0 | 59.0 | 60 | 120 | 3654 | 3618 | 96 |

| 2021/22 | 175 | 522 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 85.0 | 57.0 | 36 | 96 | 1752 | 1740 | 72 |

| 2022/23 | 150 | 443 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 86.0 | 61.0 | 54 | 156 | 4128 | 4002 | 228 |

| 2023/24 | 138 | 543 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 72.0 | 56.0 | 162 | 276 | 3552 | 3228 | 438 |

| Average | 160.8 | 484.9 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 73.4 | 46.9 | 109.6 | 226.6 | 3410.7 | 3316.9 | 210.7 |

| Pests | ET(s) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Aphis glycines | 273 ± 38 aphids/plant | [50] |

| Bemisia tabaci | (a) 1.5 insect per leaflet (b) Beginning of sooty mood formation |

[51] |

| Crocidosema sp. | 50% of damaged plants | [47] |

| Defoliators | (a) 30% defoliation (soybean in the vegetative stage) - Brazil, Illinois, Iowa and North Dakota (USA) (b) 35% defoliation (soybean in the vegetative stage) – USA (c) 40% defoliation (soybean in the vegetative stage) – Michigan and Ohio (USA) (d) >40% defoliation (soybean in the vegetative stage) – Indiana (USA) or (e) 15% defoliation (soybean in the reproductive stage R1 to R6) – Brazil, Ohio and Michigan (USA) (f) >15% defoliation (soybean in the reproductive stage R1 to R6) – Indiana (USA) (g) 20% defoliation (soybean in the reproductive stage) – Illinois, Iowa and North Dakota (USA) |

[44,53,54] |

| Helicoverpa zea | 3.5 caterpillars /meter or sample cloth or 9 caterpillars/ 25 seweeps - USA | [55] |

| Heliothinae (Helicoverpa spp. and Chloridea virescens) | (a) four caterpillars/meter or sample cloth (soybean in the vegetative stage) – Brazil or (b) two caterpillars/meter or sample cloth (soybean in the reproductive stage) - Brazil |

[24] |

| Pod feeders | 25% damaged pods | [46] |

| Spodoptera spp. | 10 caterpillars (≥1.5 cm)/meter or sample cloth | [56] |

| Stink bugs |

(a) two stink bugs (≥0.5 cm)/meter or sample cloth (soybean for grain production) - Brazil (b) three stink bugs (≥0.6 cm)/meter or sample cloth – USA (c) nine stink bugs (≥0.6 cm)/25 sweeps - USA or (d) one stink bugs (≥0.5 cm)/meter or sample cloth (soybean for seed production) - Brazil |

[45,53] |

| Tetranychus cucurbitacearum | 21.23 mites/leaflet | [57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).