1. Introduction

Alecrim-do-campo (

Baccharis dracunculifolia) is a species belonging to the Asteraceae family, widely distributed in South America, with marked agroindustrial importance due to its close relationship with propolis production, and, in traditional medicine, due to its pharmacological potential [

1,

2,

3]. The pharmacological potential of compounds synthesized by alecrim-do-campo is strongly associated with antimicrobial activity against a range of medically important microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi [

4,

5], as well as antitumor activity [

6], cytoprotective, immunomodulatory [

7], hepatoprotective [

8] and photoprotective effects [

9].

Within the components of its complex chemical profile, several phenolic compounds, such as artepillin C and p-coumaric acid [

10,

11], and terpenoids such as α-pinene, trans-nerolidol, δ-elemene and α-muurolol have been reported [

12,

13,

14,

15]. In general, terpenoids play a crucial role in plant ecophysiology, contributing both to organism survival through indirect defense against herbivores and to reproduction, by attracting pollinators [

16]. In addition to their ecological functions, in agroindustry terpenoids stand out not only for their bioactive properties but also for their organoleptic characteristics, such as characteristic odor, which are important for product quality and consumer acceptance.

For the analysis of volatile compounds, one widely used method is solid-phase microextraction in headspace mode (HS-SPME). This method uses fibers coated with specific materials to adsorb analytes in the sample, and the choice of fiber coating and the definition of extraction parameters are decisive in the analytical process [

17].

Coupled to this method, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is used as the analytical technique, enabling the separation of complex mixtures, compound identification and quantification. Separation of mixture components is based on the time each compound takes to pass through the chromatographic column. Subsequently, identification is achieved by ionizing and fragmenting these compounds in the mass spectrometer. Ionization and fragmentation allow analysis based on the mass-to-charge ratio of fragments, enabling compound identification [

18].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the efficiency of different extraction conditions for volatile compounds in alecrim-do-campo to support the search for biochemical markers of alecrim-do-campo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Sample Preparation

Samples were collected from a population in Sete Lagoas, Minas Gerais, Brazil, at an altitude of 761 m, at 19° 27’ 57” S and 44° 14’ 48” W. After collection, the plant material, without distinction of plant sex (as it was not the flowering season), was placed in polyethylene bags and transported to the Phytochemistry Laboratory of the Federal University of São João del-Rei, Sete Lagoas Campus (UFSJ/CSL), where it was washed with running water to remove impurities.

2.2. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Fibers

The extraction of volatile compounds was evaluated using three semipolar HS-SPME fibers: polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB, 65 μm), divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS, 50/30 μm) and carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (CAR/PDMS, 75 μm).

2.3. Equipment

Analyses were performed on a gas chromatograph (GC-2010 Plus, Shimadzu) coupled to a GC/MS-QP2010 SE mass spectrometric detector with an ion-trap analyzer and a split/splitless injector operated in splitless mode, installed at the Food Analysis Laboratory – UFSJ/CSL.

Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow of 1 mL min⁻¹. The chromatographic analysis conditions were as follows: injector temperature 250 °C; desorption time 5 min; ion source temperature 200 °C; interface temperature 275 °C. A capillary column RTx®-5MS (Crossbond® 5% diphenyl / 95% dimethylpolysiloxane) was used with the following dimensions: 30 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter and 0.25 μm film thickness (Restek, USA). Column oven temperature was programmed as follows: initial temperature 40 °C (3 min), then 7 °C min⁻¹ to 125 °C (1 min isothermal), followed by 5 °C min⁻¹ to 210 °C (1 min isothermal), and finally 15 °C min⁻¹ to 245 °C, held isothermally for 3 min.

2.4. Equipment

A 2³ factorial design with three replicates at the central point was employed (Neto, 2003), aiming to determine the optimal conditions to reach the partition equilibrium of analytes between the sample and the fiber in the headspace mode, yielding the highest recovery of volatile organic compounds after chromatographic analysis. The following independent variables were evaluated: extraction time (min), extraction temperature (°C) and sample mass (g), for the extraction of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from alecrim-do-campo (

Table 1). The factorial design was built using Matlab, version 7.9.0.529 (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA, 2009). The number of VOCs captured per run was used as the response variable for the optimization of the evaluated factors, at a significance level of p = 0.05.

2.5. Extraction of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

As a standard procedure for conditioning the SPME fibers (PDMS/DVB, DVB/CAR/PDMS and CAR/PDMS), the fibers were conditioned in the gas chromatograph, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations for each fiber type. HS-SPME was used for the extraction of volatile organic compounds. Samples (0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 g) were weighed into 20 mL headspace vials, sealed with screw-cap aluminum lids and rubber septa. The headspace vials were preheated for 5 min at the temperature designated for each treatment (40, 50 or 60 °C) in a stainless-steel bath on a heating plate. Then, the SPME fiber was introduced in the headspace mode for analyte adsorption and exposed to the gaseous phase for the extraction time defined for each treatment. After extraction, the fiber was inserted into the GC injector at 250 °C for 5 min for desorption of the extracted volatile organic compounds [

19].

2.6. Identification of Volatile Organic Compounds

Peaks selected for identification were those with a slope of 1000 min⁻¹ and a relative area greater than 0.05%. Compound identification was performed by comparing the obtained spectra with the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) library, considering a similarity index (SI) higher than 85.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were identified based on the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio corresponding to each peak in the total ion chromatogram of each analyzed sample, which were compared with mass spectra obtained by electron impact (EI) ionization at 70 eV, with a full-scan range from 35 to 350 m/z [

20]. To confirm VOCs, the identified compounds were compared with those previously reported in the literature. Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios and peak intensities were obtained from the GCMSolution software (Shimadzu) and exported to Microsoft Office Excel 2024, which was used for peak selection; in this work, only peaks with relative area higher than 0.05% were retained.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Extraction Conditions for HS-SPME Fibers

The results from the 2³ factorial design with three central-point replicates are presented in

Table 2, with the number of VOCs as the response variable. The number of extracted compounds varied from 41 to 75 for the CAR/PDMS fiber, from 21 to 67 for the PDMS/DVB fiber and from 39 to 74 for the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber, considering the treatments with the lowest and highest numbers of compounds obtained, respectively.

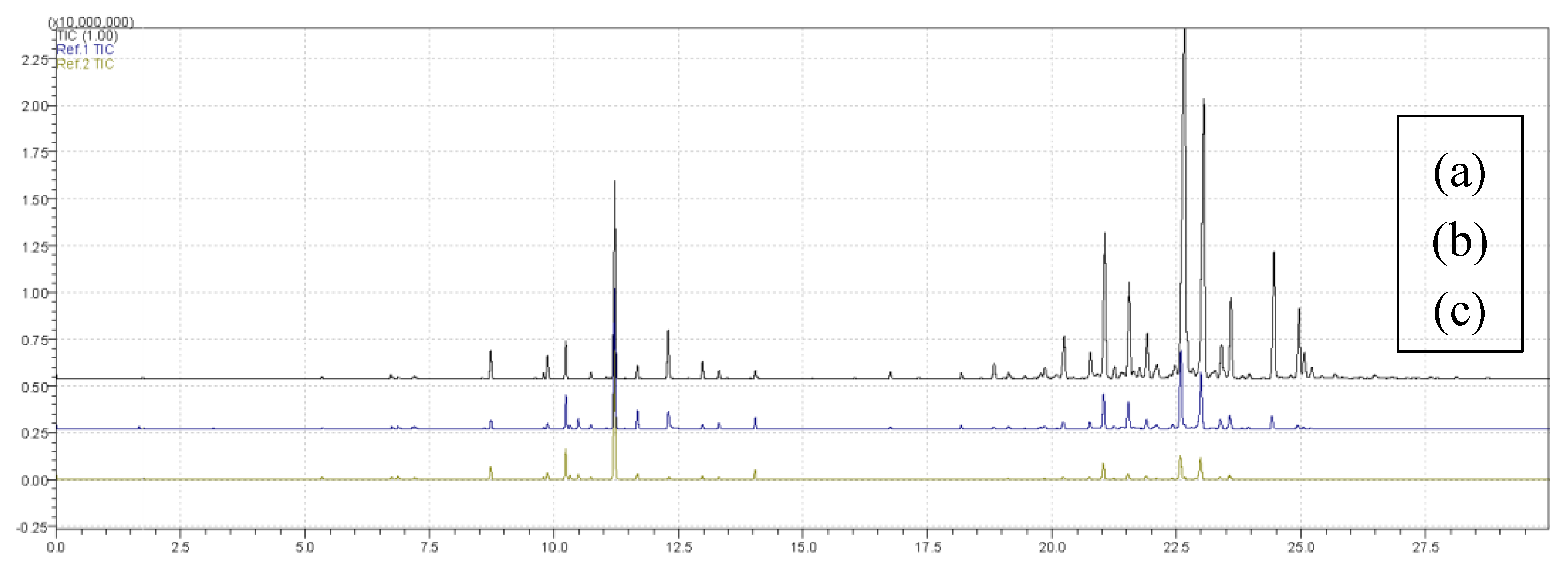

Pareto charts for each fiber (

Figure 1) show that the factors that cross the red line corresponding to a significance level of p = 0.05 are considered statistically significant. Only fiber exposure time was statistically significant in the extraction process when using the CAR/PDMS fiber (

Figure 4a).

Figure 1b shows the results for the PDMS/DVB fiber. For this fiber, no factor showed a statistically significant influence on compound extraction.

Figure 1c was generated from the data obtained using the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber. Similarly to the PDMS/DVB fiber, no factor had a statistically significant impact on compound extraction.

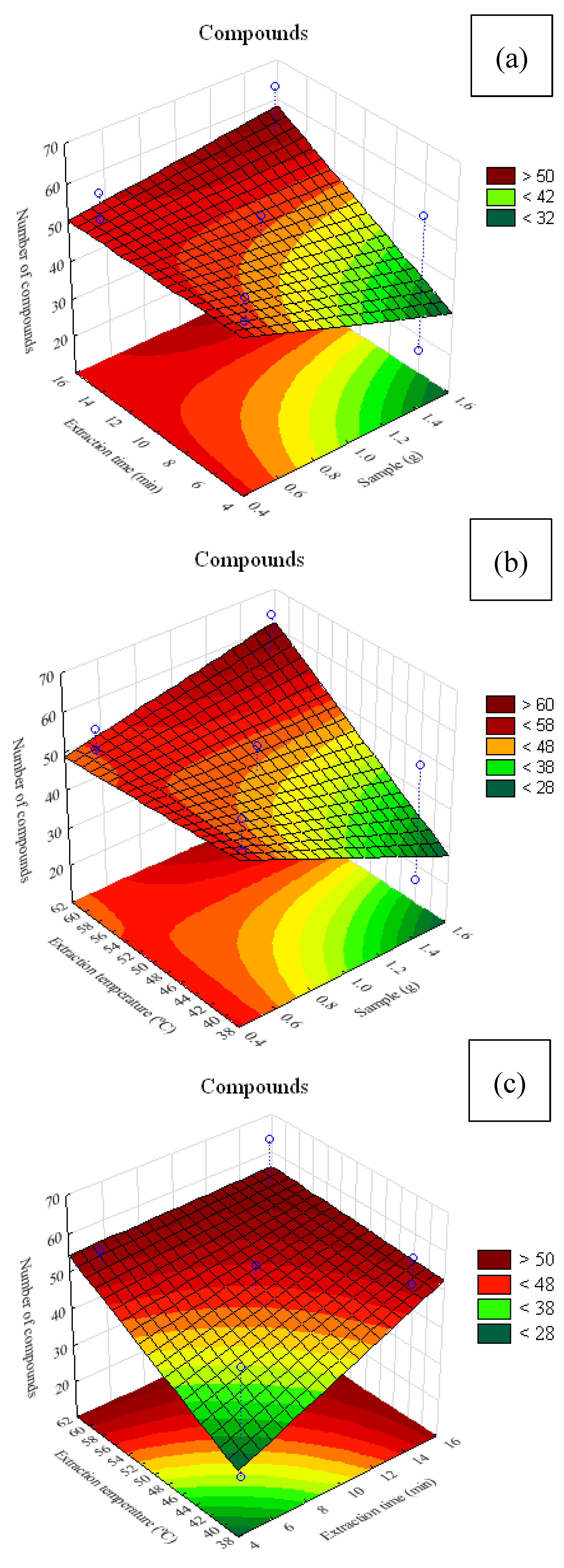

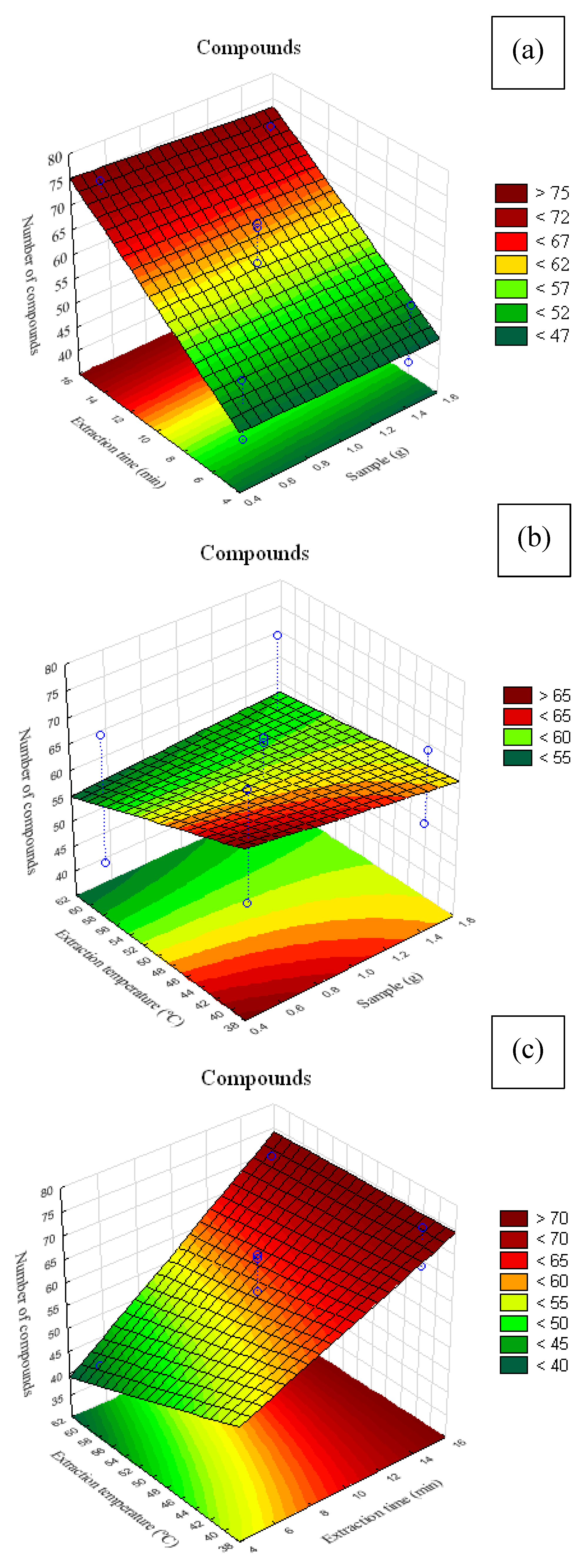

Response surface plots illustrating the interaction among factors and the number of extracted compounds using the CAR/PDMS fiber are presented in

Figure 2. Among the treatments, T4, corresponding to 0.5 g of sample, heating at 60 °C and extraction time of 15 min, yielded the highest number of compounds (75). In contrast, treatment T9, with 1.5 g of sample, heating at 60 °C and extraction time of 5 min, showed the lowest number of extracted compounds (

Table 2).

In

Figure 5a, it can be observed that the sample mass used did not markedly interfere with the number of extracted compounds. In

Figure 5b, it can be inferred that, at temperatures close to 40 °C, smaller sample masses resulted in a lower number of identifiable compounds. In

Figure 5c, it is evident that significant numbers of compounds can be obtained with extraction times shorter than 10 min, regardless of temperature.

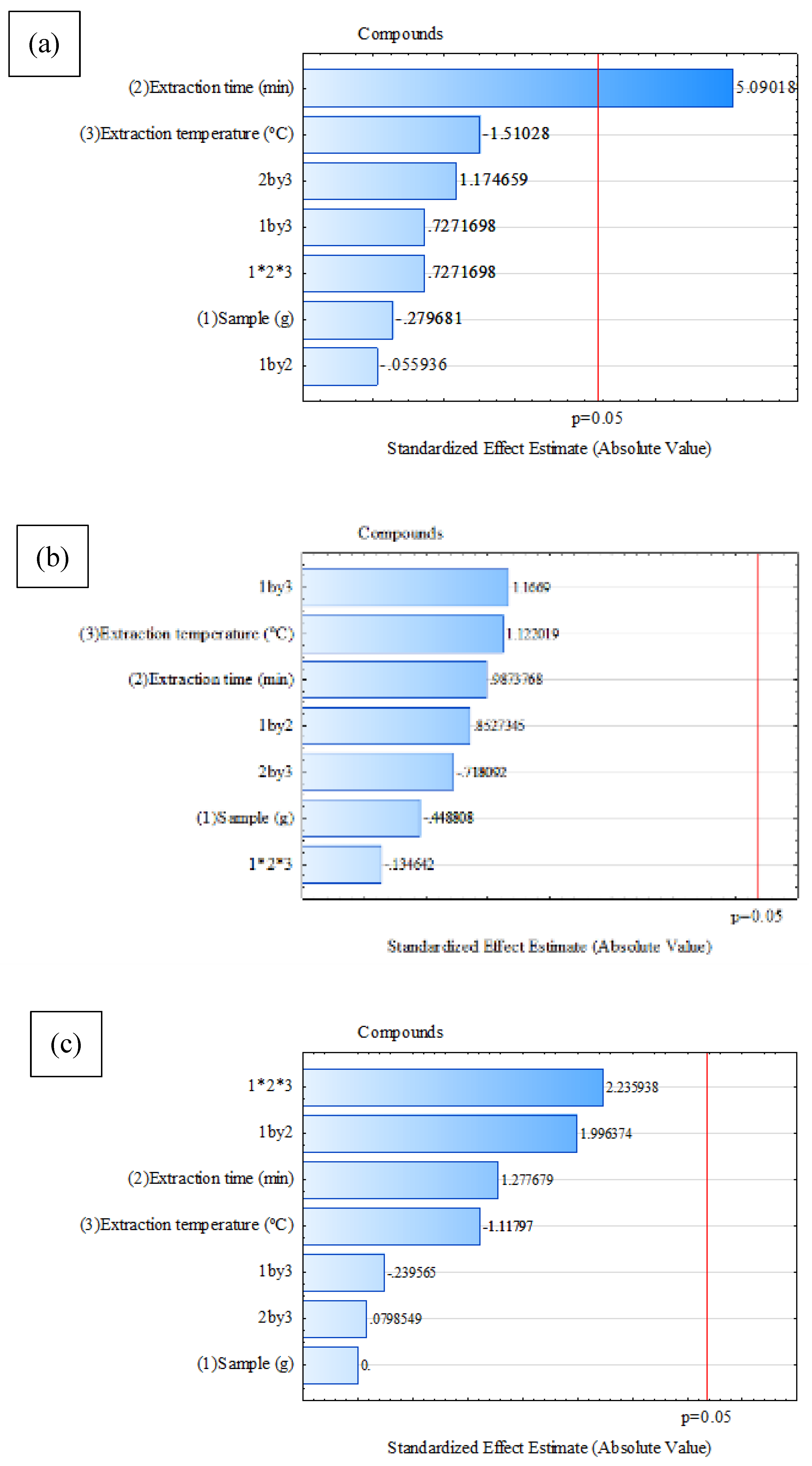

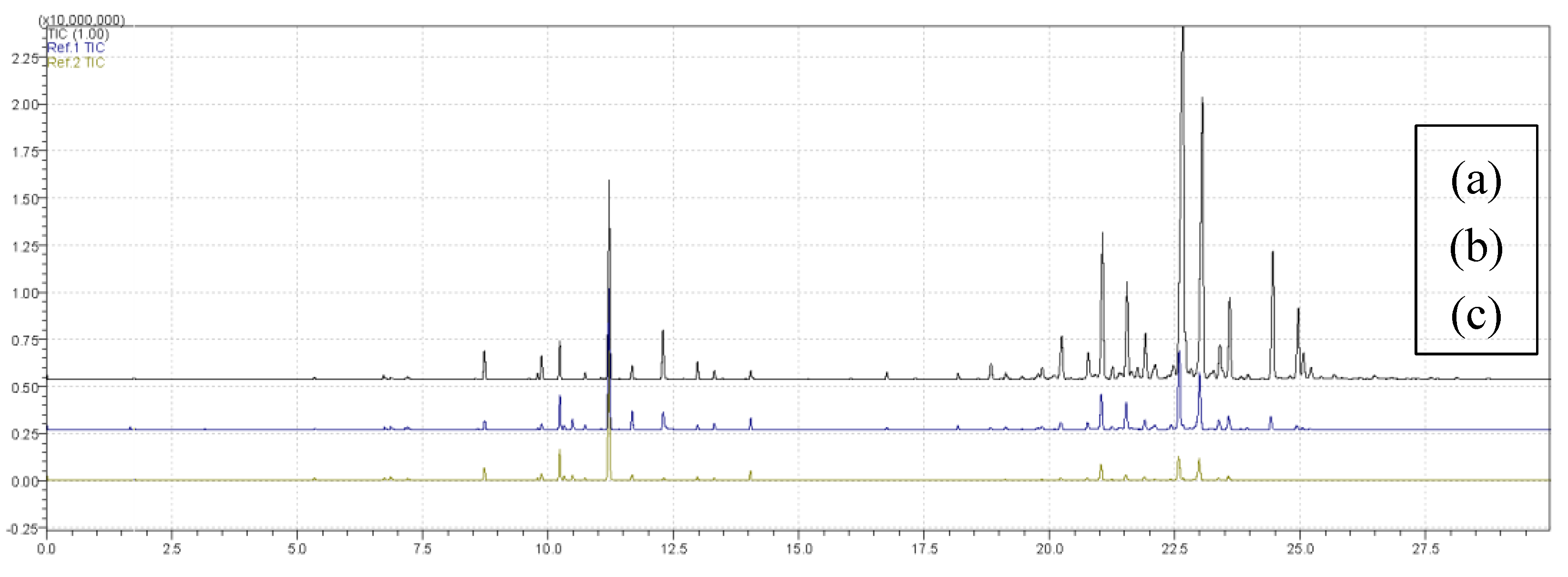

Figure 2 presents overlapping chromatograms for treatments (a) T4, (b) T6 and (c) T9, obtained using the CAR/PDMS fiber. The chromatographic profiles differ in intensity and number of peaks, indicating variations in volatile composition among treatments, with T4 showing the highest number of compounds, T6 corresponding to the central point of the design, and T9 yielding the lowest number of extracted compounds.

For the PDMS/DVB fiber, the treatment that most stood out was T11, corresponding to 1.5 g of sample, heating at 60 °C and 15 min of fiber exposure, with 67 extracted compounds. The treatment that resulted in the lowest number of isolated compounds was T8, corresponding to 1.5 g of sample, heating at 40 °C and 5 min of extraction, yielding 21 compounds (

Table 2). Response surface plots illustrating the interaction between factors and the number of extracted compounds are shown in

Figure 3.

In

Figure 3a, it can be seen that, for extraction times above 12 min, higher sample masses favored an increase in the number of extracted VOCs. In

Figure 3b, it can be inferred that temperatures above 50 °C and sample masses greater than 1.0 g tended to yield more VOCs.

Figure 3c shows that more compounds were extracted at temperatures above 55 °C and with extraction times of at least 12 min.

Figure 4 presents overlapping chromatograms for treatments (a) T11, (b) T6 and (c) T8, obtained with the PDMS/DVB fiber. The chromatographic profiles showed variations in intensity and number of peaks, reflecting differences in volatile composition among treatments. Treatment T11 showed the highest number of extracted compounds, T6 corresponded to the central point of the experimental design, and T8 showed the lowest diversity of detected compounds.

Figure 4.

Overlaid chromatograms of treatments (a) T11, (b) T6 and (c) T8 obtained using the PDMS/DVB fiber in the extraction process.

Figure 4.

Overlaid chromatograms of treatments (a) T11, (b) T6 and (c) T8 obtained using the PDMS/DVB fiber in the extraction process.

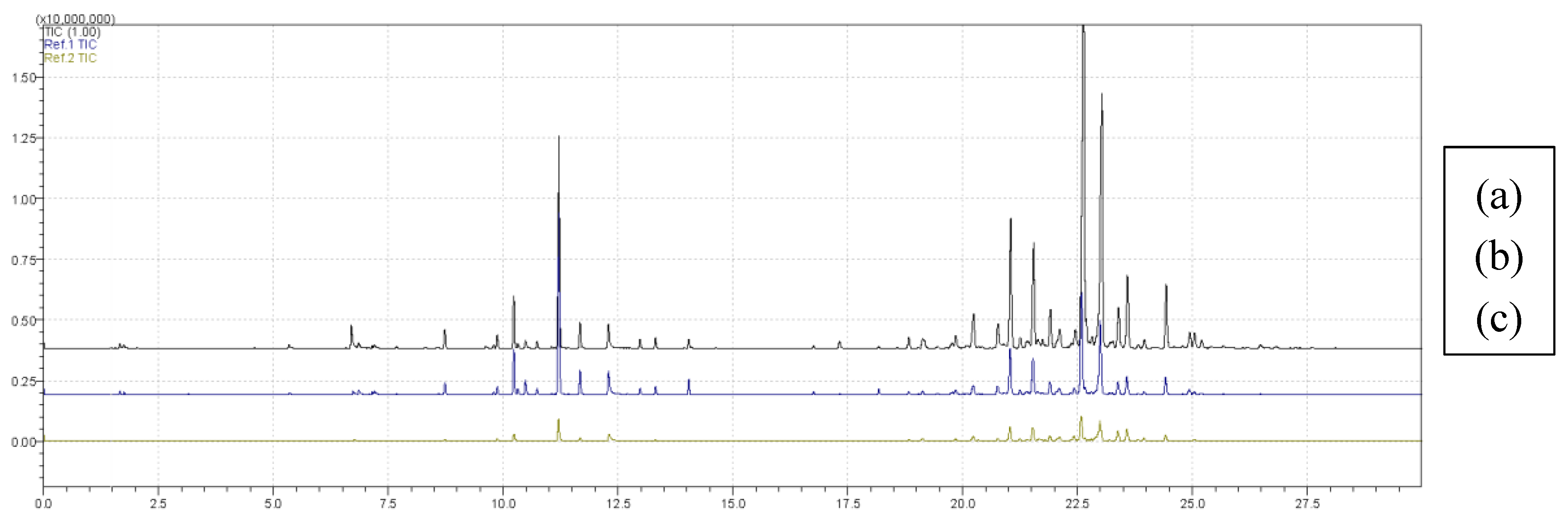

For the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber, the treatment that most stood out was T11, corresponding to 1.5 g of sample, heating at 60 °C and 15 min of extraction, with 74 extracted compounds. The treatment that resulted in the lowest number of extracted compounds was T9, corresponding to 1.5 g of sample, heating at 60 °C and 5 min of extraction, yielding 39 compounds (

Table 2). Figure 9 shows the response surface plots illustrating the interaction among factors and the number of extracted compounds.

Figure 5.

Response surface plots for volatile compounds present in alecrim-do-campo obtained with the PDMS/DVB fiber. (a) interaction between sample mass (g) and extraction time (min); (b) interaction between sample mass (g) and analyte heating temperature (°C); (c) interaction between fiber exposure time (min) and analyte heating temperature (°C).

Figure 5.

Response surface plots for volatile compounds present in alecrim-do-campo obtained with the PDMS/DVB fiber. (a) interaction between sample mass (g) and extraction time (min); (b) interaction between sample mass (g) and analyte heating temperature (°C); (c) interaction between fiber exposure time (min) and analyte heating temperature (°C).

In

Figure 5a, it can be seen that higher extraction was obtained with extraction times above 12 min and sample masses close to 1.5 g. In

Figure 5b, it is observed that, at temperatures below 45 °C, regardless of sample mass, there was a tendency to extract more VOCs.

Figure 5c shows that temperatures below 45 °C combined with 15 min of extraction favored an increase in the number of extracted compounds.

Figure 6 shows overlapping chromatograms for treatments (a) T11, (b) T6 and (c) T9, obtained with the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber. The chromatographic profiles present significant variations in intensity and number of peaks, indicating differences in volatile composition among treatments. Treatment T11 stood out for its greater diversity of extracted compounds, while T6 represented the central point of the experimental design and T9 showed the lowest number of detected compounds.

Figure 7.

Response surface plots for volatile compounds present in alecrim-do-campo obtained with the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber. (a) interaction between sample mass (g) and extraction time (min); (b) interaction between sample mass (g) and analyte heating temperature (°C); (c) interaction between fiber exposure time (min) and analyte heating temperature (°C).

Figure 7.

Response surface plots for volatile compounds present in alecrim-do-campo obtained with the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber. (a) interaction between sample mass (g) and extraction time (min); (b) interaction between sample mass (g) and analyte heating temperature (°C); (c) interaction between fiber exposure time (min) and analyte heating temperature (°C).

3.2. Identification of Compounds

Considering the criteria used for identification, 79 compounds were tentatively identified (

Table 3). The fiber that showed the highest affinity for the volatiles present in the plant matrix was DVB/CAR/PDMS, with 64 adsorbed compounds, followed by CAR/PDMS and PDMS/DVB, each with 51 adsorbed compounds.

Of the compounds identified, 33 were present in all three fibers, which can be attributed to the similarity of their physical properties. Despite the overlap in VOCs, some compounds were detected in only one fiber: 10 compounds were exclusive to CAR/PDMS, 4 were exclusive to PDMS/DVB and 11 were exclusive to DVB/CAR/PDMS.

The predominant phytochemical class was that of terpenoids, accounting for 76% of the volatile profile. Among them, 14 monoterpenes and 32 sesquiterpenes were identified. This trend was observed for all fibers, but the fiber that most efficiently extracted these compounds was PDMS/DVB, which agrees with the findings of García et al. (2019) concerning the affinity of this fiber for compounds belonging to these phytochemical classes.

Compounds such as α-pinene, β-pinene, α-thujene, sabinene, myrcene, γ-terpinene, α-copaene, α-humulene, γ-muurolene and p-cymene occur in marked amounts in other Baccharis species (Trombin-Souza et al., 2017; Minteguiaga et al., 2015; Tomazzoli et al., 2021), suggesting a chemotaxonomic pattern for the genus that can be used as chemical biomarkers.

The pronounced presence of these terpenes and sesquiterpenes underscores their relevance as characteristic components of the species and highlights their potential as chemical markers and promising targets in studies on bioactivity and pharmacological applications.

5. Conclusions

Among the evaluated factors, only extraction time significantly influenced compound extraction using the CAR/PDMS fiber, with no specific factor or interaction effects detected for the other fibers. Extraction times exceeding 10–12 min were essential for obtaining significant numbers of extracted compounds across all fibers (CAR/PDMS, PDMS/DVB, and DVB/CAR/PDMS), regardless of temperature and sample mass, with optimal conditions varying by fiber type. Although the number of compounds was very similar across the fibers, the fibers that extracted the most were the CAR/PDMS and DVB/CAR/PDMS fibers.

Thus, optimizing extraction parameters is crucial for industry, providing an alternative strategy for identifying biochemical markers and ensuring the quality of plant-derived products rich in bioactive compounds. Moreover, using fibers composed of different materials offers substantial advantages by enabling detection across a broader spectrum of volatiles, thereby enhancing the precision of biomarker searches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.G. and J.O-F.M..; methodology, L.S.G, T.C., A.L.S.V, M.R.S., E.J.A.C, A.C.C.F.F.P, E.M.G., H.A.T and J.O-F.M.; software, L.S.G., M.R.S, E.J.A.C. and A.H.O.J.; validation, L.S.G., T.C., A.L.S.V, E.J.A.C, A.C.C.F.F.P, E.M.G., H.A.T and J.O-F.M..; data curation, L.S.G. and J.O.-F.M.; writing—review and editing, L.S.G, T.C., A.L.S.V, E.J.A.C, A.C.C.F.F.P, E.M.G., H.A.T and J.O.-F.M.; visualization, A.H.d.O.J. and J.O.-F.M.; supervision, J.O-F. M .; project administration, J.O-F. M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) / code 001), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (research productivity 307787/2022-2 and 404432/2024-7), Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG)- Finance Code APQ-04336-23, APQ-05883-24, PPE-00094-23.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei, the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and the Teaching, Research and Extension Group in Chemistry and Pharmacognosy (GEPEQF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Minteguiaga, M., González, H. A., Ferreira, F., & Dellacassa, E. (2021). Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of South America Vol. 2: Argentina, Chile and Uruguay (pp. 85-105). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Bonin, E., Carvalho, V. M., Avila, V. D., dos Santos, N. C. A., Benassi-Zanqueta, E., Lancheros, C. A. C., ... & do Prado, I. N. (2020). Baccharis dracunculifolia: Chemical constituents, cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity. Lwt, 120, 108920. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, C. T. V., Ribeiro, V. P., de Carvalho, T. C., Furtado, R. A., Jacometti Cardoso Furtado, N. A., & Bastos, J. K. (2022). Disinfectant activities of extracts and metabolites from Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 75(2), 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Contigli, C., de Souza-Fagundes, E. M., de Andrade, W. P., Takahashi, J. A., Oki, Y., & Fernandes, G. W. (2022). Perspectives of Baccharis secondary metabolites as sources for new anticancer drug candidates. In Baccharis: From Evolutionary and Ecological Aspects to Social Uses and Medicinal Applications (pp. 427-473). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Cappellucci, G., Biagi, M., Romão-Veiga, M., Ribeiro-Vasques, V. R., Miraldi, E., Baini, G., & Sforcin, J. M. (2025). Molecular mechanisms involved in the immunomodulatory action of Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. extract using an integrated in silico/in vitro approach. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, rgaf110. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, A. C., Santos França, T. C., de Queiroz e Silva, T. F., Rodrigues, D. M., Mendes Pilati, S. F., Bastos, J. K., & da Silva, L. M. (2025). Baccharis dracunculifolia and Brazilian green propolis extracts improve “two-hit” liver injury in MICE. Natural Product Research, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- de Assis Lage, T. C., Montanari, R. M., Fernandes, S. A., de Oliveira Monteiro, C. M., Senra, T. D. O. S., Zeringota, V., ... & Daemon, E. (2015). Chemical composition and acaricidal activity of the essential oil of Baccharis dracunculifolia De Candole (1836) and its constituents nerolidol and limonene on larvae and engorged females of Rhipicephalus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Experimental parasitology, 148, 24-29.

- Barreto, A. L. H., Lopes, M. T. do R., Pereira, F. de M., & Souza, B. de A. (2020). Controle de qualidade da própolis (48 p.). Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte. Disponível em: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1128584.

- Gazim, Z. C., Valle, J. S., Carvalho dos Santos, I., Rahal, I. L., Silva, G. C. C., Lopes, A. D., ... & Gonçalves, D. D. (2022). Ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. (ASTERACEAE). Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 1048688.

- García, Y. M., Rufini, J., Campos, M. P., Guedes, M. N., Augusti, R., & Melo, J. O. (2019). SPME fiber evaluation for volatile organic compounds extraction from acerola. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 30, 247-255.

- García, Y. M., Melo, J. O. F. (Org.). (2021). Extração e análise de compostos orgânicos voláteis por SPME-HS e GC-MS – um breve referencial teórico. In Ciências Agrárias: o avanço da ciência no Brasil (Vol. 1, pp. 68–83). Editora Científica Digital Ltda.

- Garcia, L. S., Coelho, T., Oliveira Júnior, A. H. D., Vieira, A. L. S., Cardoso, C. I., Moreira, J. P. D. S., Corrêa, E. J. A., Paula, A. C. C. F. F. D., Taroco, H. A., & Melo, J. O. F. (2025). Volatile Profile of the Baccharis Genus: A Narrative Review. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Minteguiaga, M., Umpiérrez, N., Xavier, V., Lucas, A., Mondin, C., Fariña, L., ... & Dellacassa, E. (2015). Recent findings in the chemistry of odorants from four Baccharis species and their impact as chemical markers. Chemistry & Biodiversity, 12(9), 1339-1348.

- de Oliveira Sartori, A. G., Saliba, A. S. M. C., Martarello, N. S., Lazarini, J. G., do Amaral, J. E. P. G., da Luz, C. F. P., & de Alencar, S. M. (2024). Changes in phenolic profile and anti-inflammatory activity of Baccharis beebread during gastrointestinal digestion/intestinal permeability in vitro. Food Chemistry, 432, 137234.

- Pinto-Zevallos, D. M., Martins, C. B., Pellegrino, A. C., & Zarbin, P. H. (2013). Volatile organic compounds in induced plant defense against herbivorous insects. Química Nova, 36, 1395-1405.

- Ramos, A. L. C. C., Nogueira, L. A., Silva, M. R., do Carmo Mazzinghy, A. C., Mariano, A. P. X., de Albuquerque Rodrigues, T. N., de Paula, A. C. C. F. F., de Melo, A. C., Augusti, R., de Araújo, R. L. B., Lacerda, I. C. A., & Meloelo, J. O. F. (2022). Chemical approach to the optimization of conditions using HS-SPME/GC-MS for characterization of volatile compounds in Eugenia brasiliensis fruit. Molecules, 27(15), 4955. [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, M., Facanali, R., Haber, L. L., Vieira, M. A. R., Isobe, M. T. C., Cavallari, M. M., ... & Marques, M. O. M. (2023). Chemical and genetic diversity of Baccharis dracunculifolia DC.(Asteraceae) from the Cerrado biome. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 111, 104735.

- Tomazzoli, M. M., Amaral, W. D., Cipriano, R. R., Tomasi, J. D. C., Gomes, E. N., Ferriani, A. P., ... & Deschamps, C. (2021). Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of essential oils from populations of Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. in southern Brazil. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 64, e21190253.

- Trombin-Souza, M., Trombin-Souza, M., Amaral, W., Pascoalino, J. A. L., Oliveira, R. A., Bizzo, H. R., & Deschamps, C. (2017). Chemical composition of the essential oils of Baccharis species from southern Brazil: a comparative study using multivariate statistical analysis. Journal of EssEntial oil rEsEarch, 29(5), 400-406.

- Tsikas, D. (2025). Quantitative GC-NICI-MS and GC-NICI-MS/MS analysis by using isotopologs as internal standards: A tutorial review. Journal of Chromatography B, 124648. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, R. S., De Mendonça, S., Mendes, P. B., Paulino, N., Mimica, M. J., Lagareiro Netto, A. A., Lira, I. S., López, B. G., Negrão, V., & Marcucci, M. C. (2017). Artepillin C and phenolic compounds responsible for antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of green propolis and Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. Journal of applied microbiology, 122(4), 911–920. [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, I. T., Da Silva, A. C. P., Accioli, C. D. A. F., Amorim, J. M., Leite, P. M., Faraco, A. A. G., Santos, B. A. M. C., Scopel, M., & Castilho, R. O. (2023). Optimized Baccharis dracunculifolia extract as photoprotective and antioxidant: In vitro and in silico assessment. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 440, 114654. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).