Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

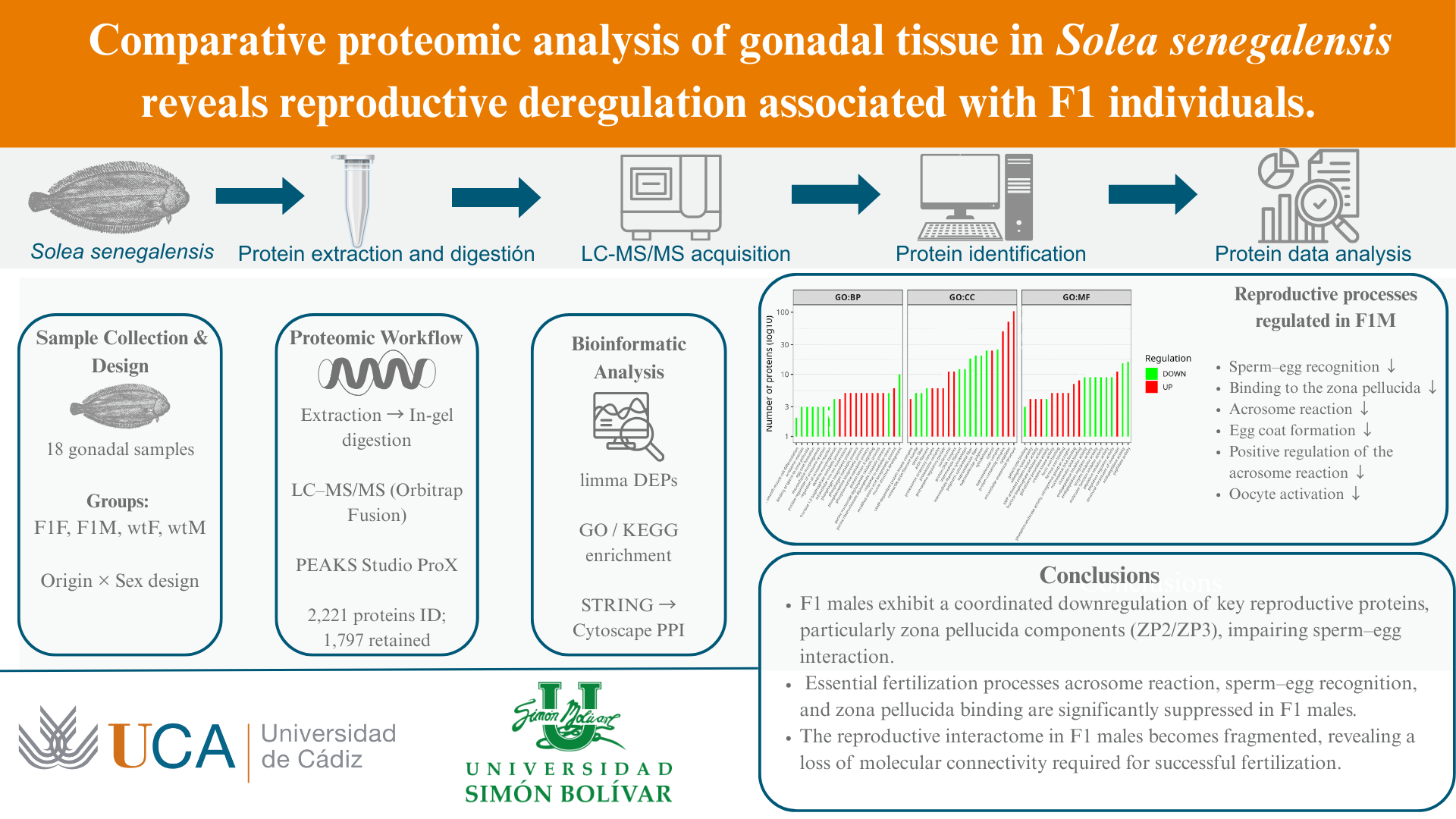

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Individuals and sampling

2.2. Protein extraction

2.3. Preparation of samples for proteomic study

2.4. nLC-MS2 Analysis

2.5. Data analysis

2.6. Bioinformatic study

3. Results

3.1. Identification and quantification of proteins

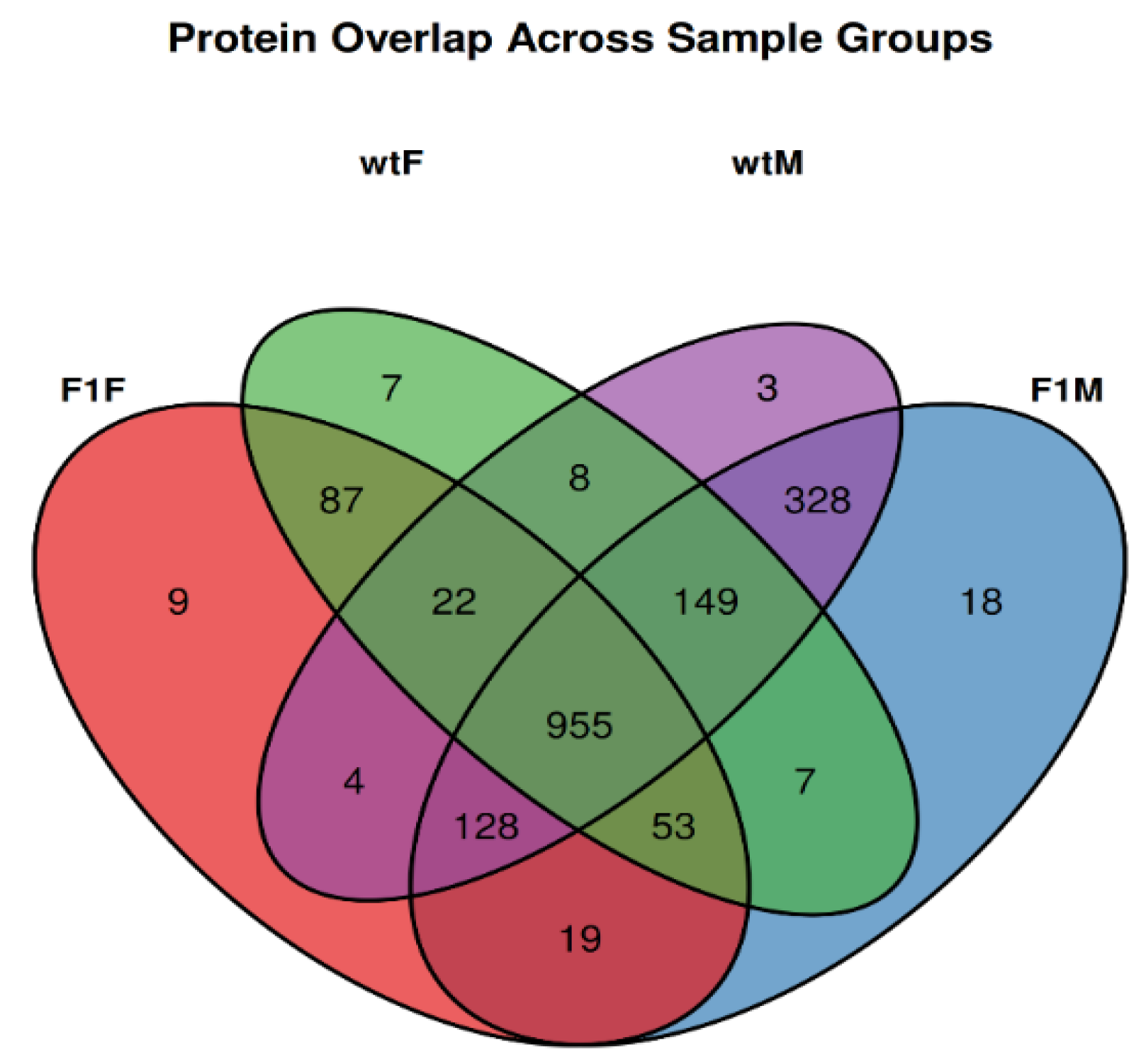

Exploratory proteomic analysis and identification of exclusive proteins

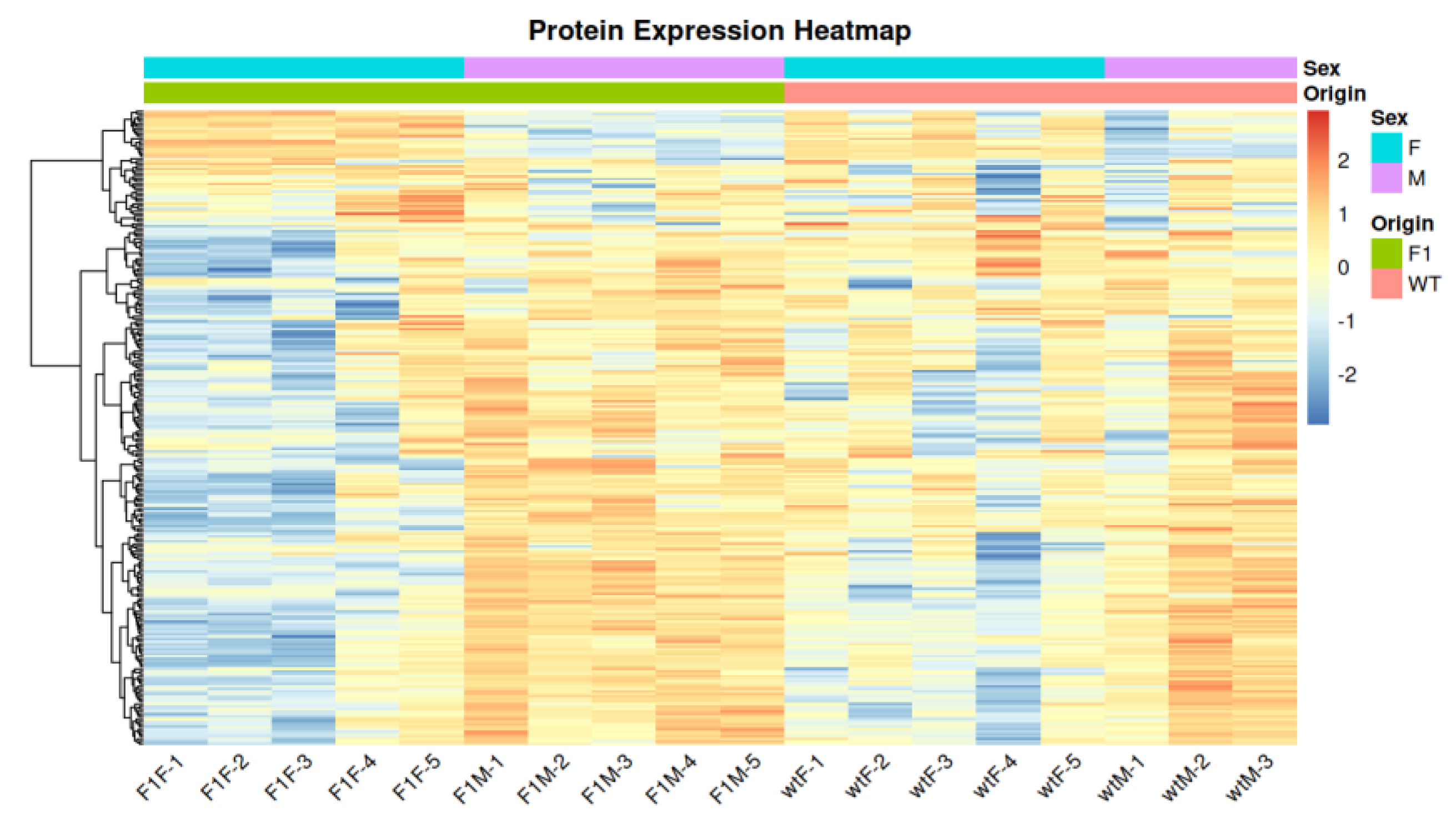

3.2. Correlation and clustering analysis

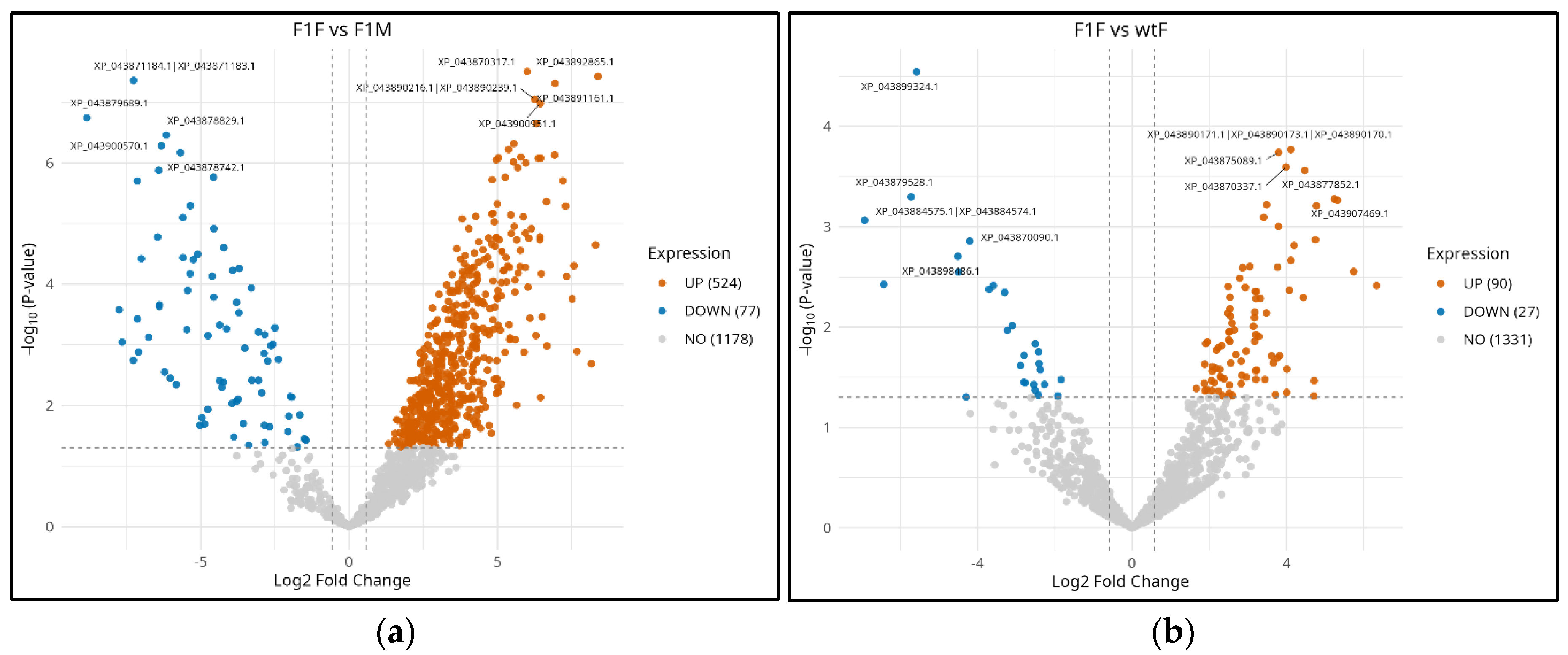

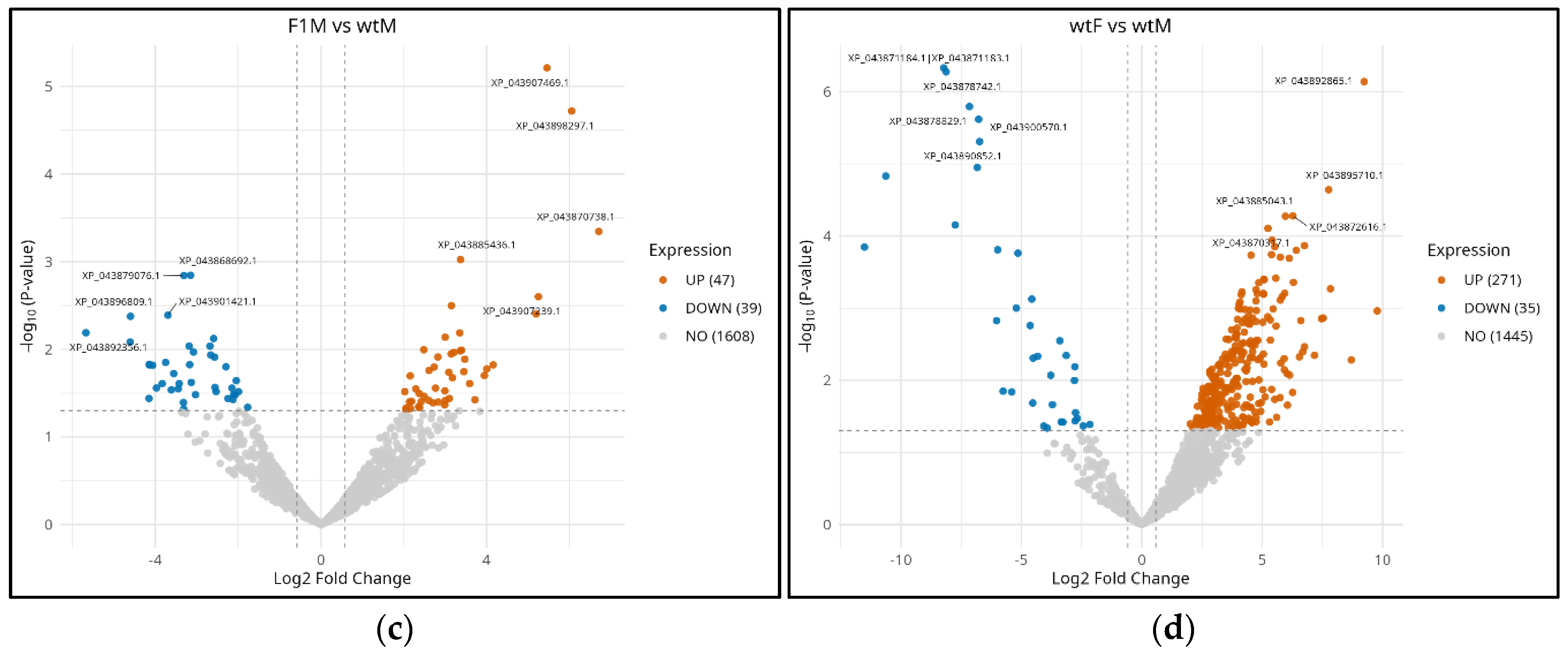

3.3. Differential expression analysis

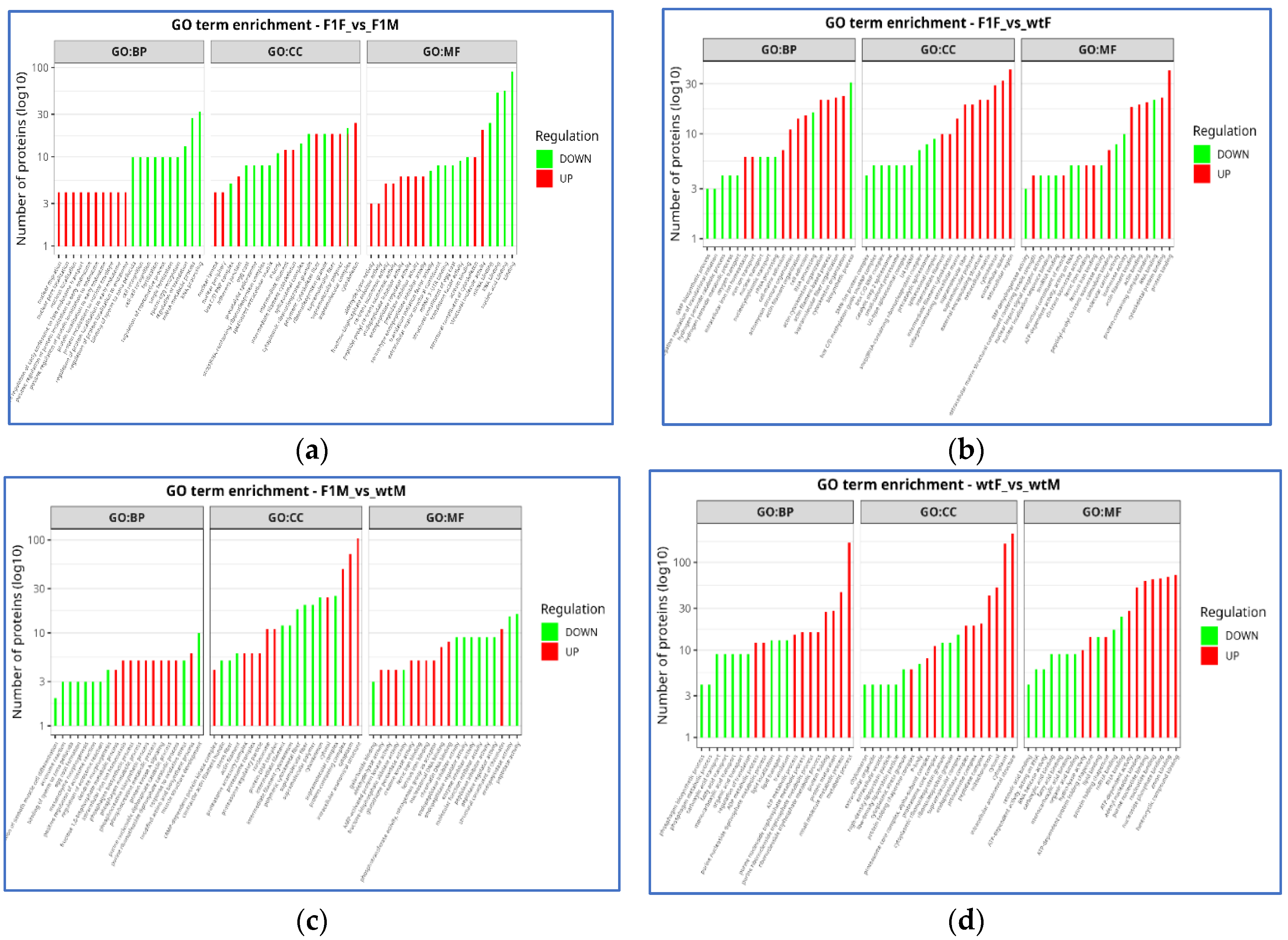

3.4. Functional enrichment analysis in Gene Ontology (GO)

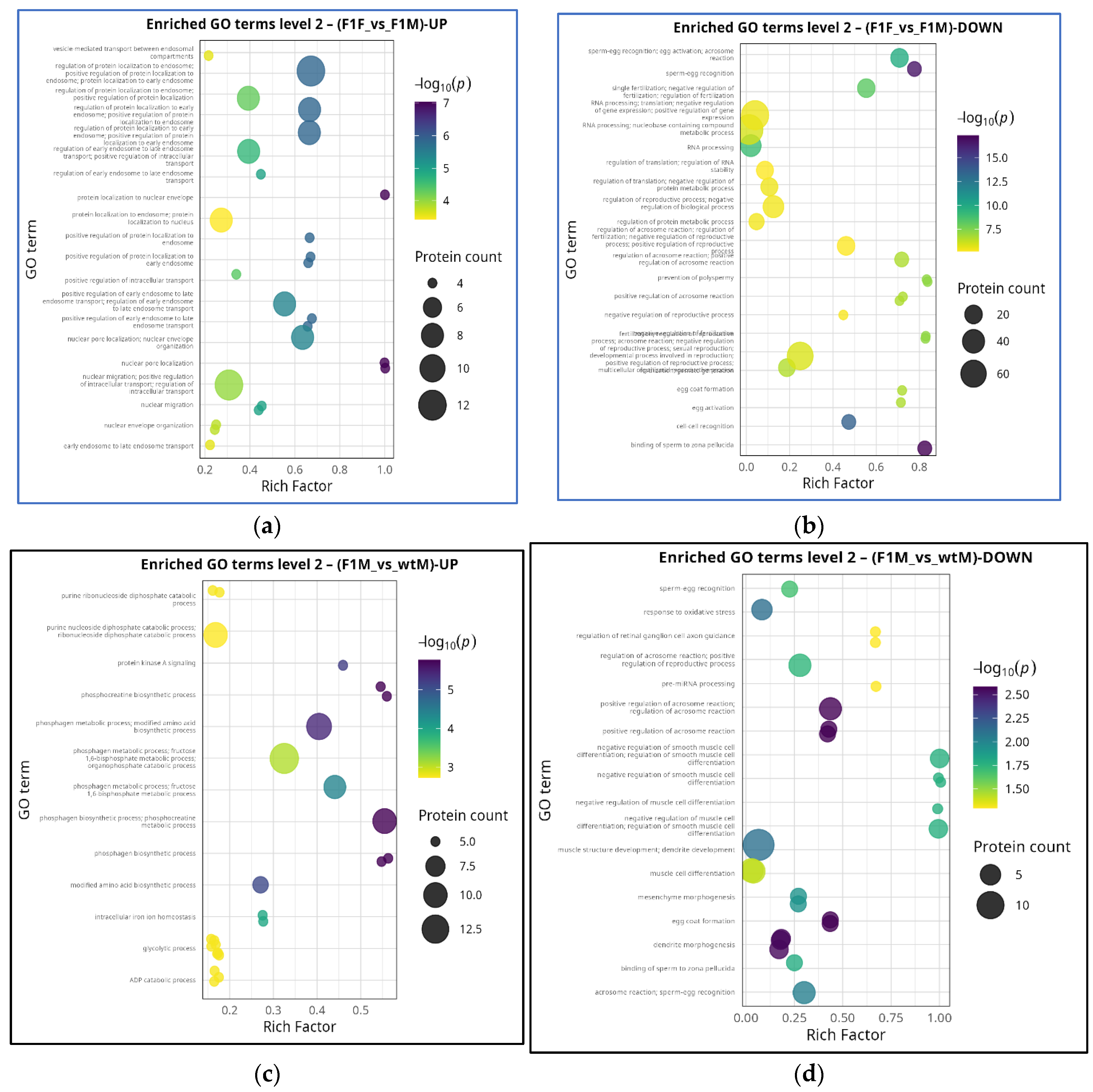

GO Level 2 term enrichment in F1F vs F1M and F1M vs wtM comparisons

3.5. Functional analysis in KEGG pathways

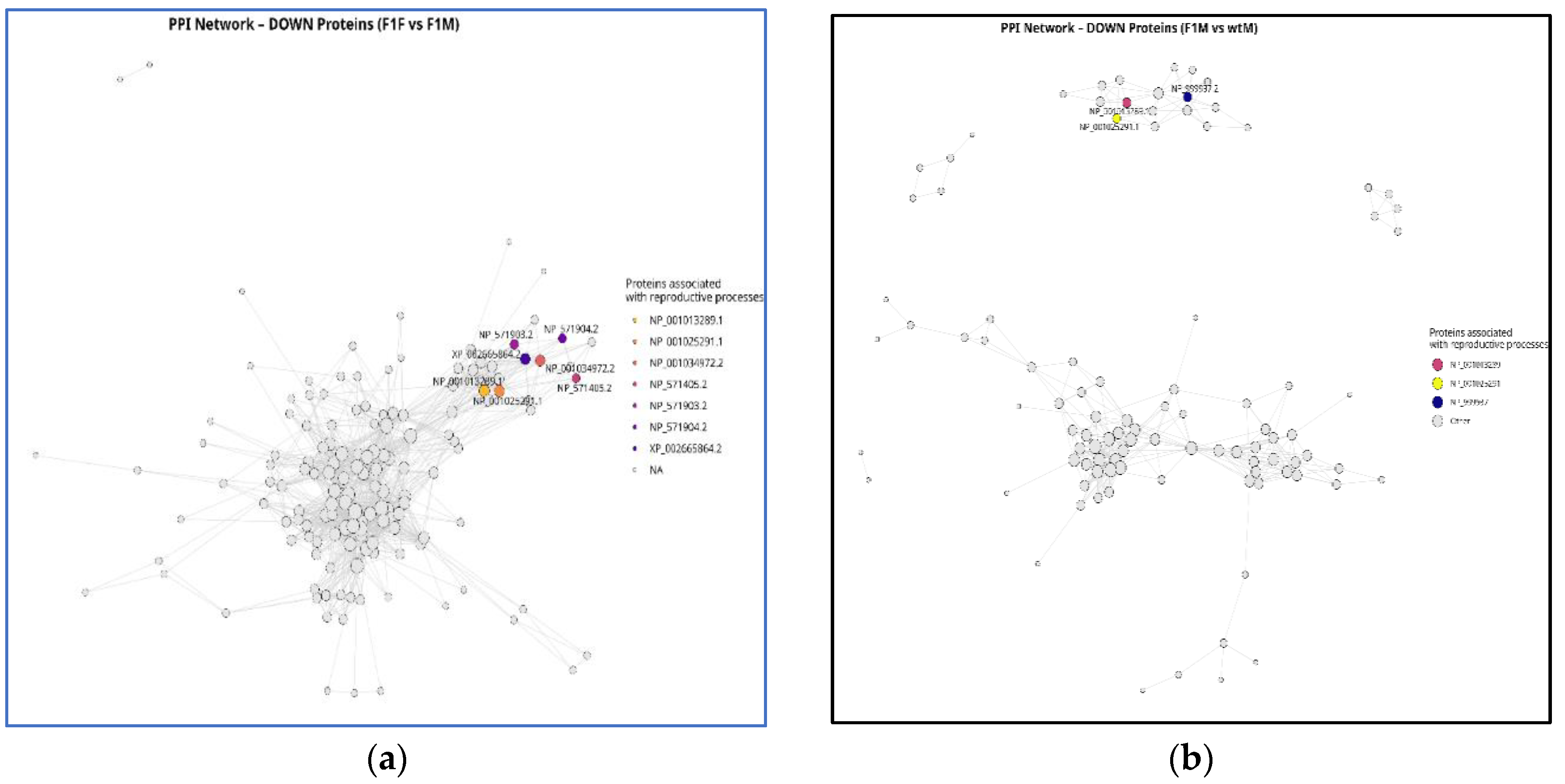

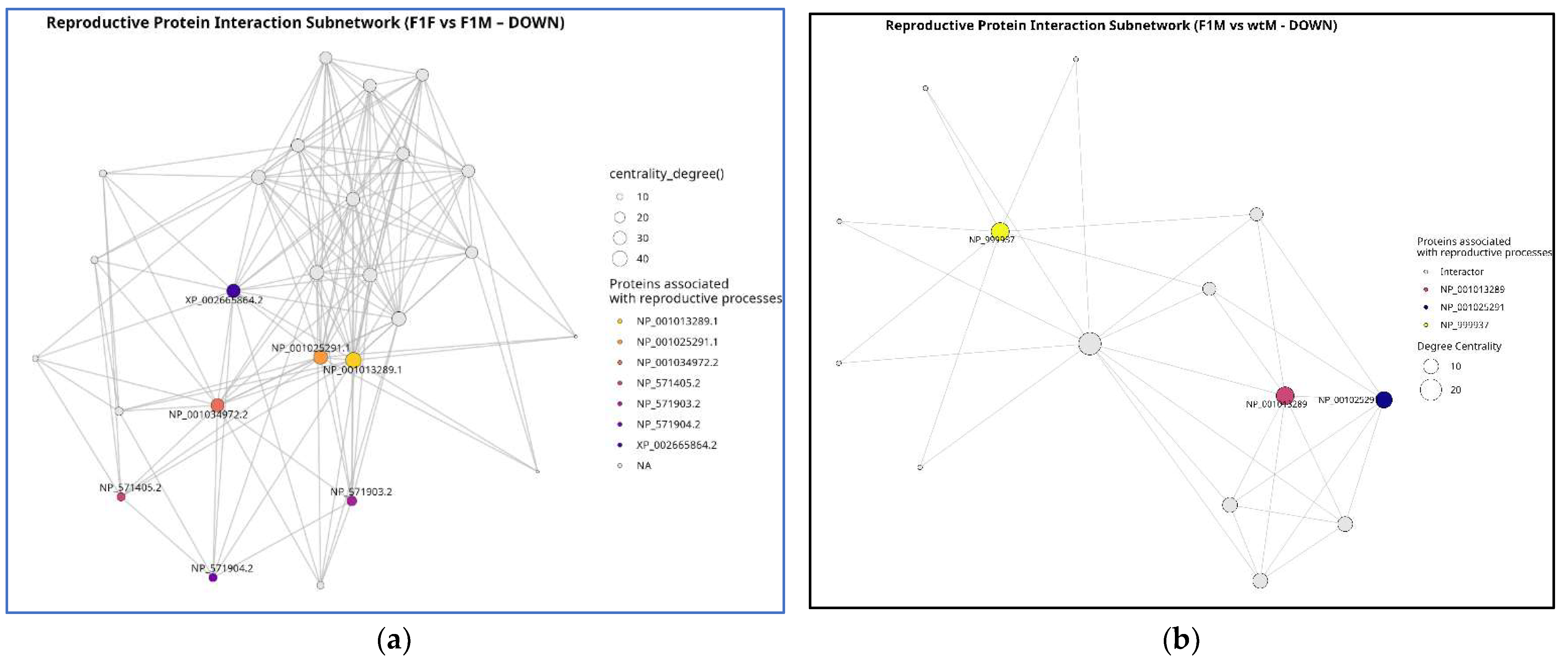

3.6. Protein -protein interaction (PPI) network

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) subnetwork

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Adenosine diphosphate |

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| BP | Biological process |

| BLASTp | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for proteins |

| CC | Cellular component |

| CID | Collision-induced dissociation |

| CpG | Cytosine–phosphate–guanine dinucleotide |

| DEPs | Differentially expressed proteins |

| DMCpG | Differentially methylated CpG |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| F1 | Cultivated or born and breed in captivity |

| F1F | Cultivated female |

| FIM | Cultivated male |

| FSHR | Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GPX1b | Glutathione peroxidase 1b |

| KEEG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LC–MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MF | Molecular function |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| SCAI | Servicios Centrales de Apoyo a la Investigación |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate – polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| SPACA4 | Sperm acrosome associated 4 |

| STRING | Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| TFA | Trifluoride acetic acid |

| TGF-beta | Transforming growth factor beta |

| UPLC | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| wt | Wild-type |

| wtF | Wild-type female |

| wtM | Wild-type male |

| XP / NP | RefSeq protein accession prefixes |

| ZP | Zona pellucida |

References

- Díaz-Ferguson, E.; Cross, I.; Barrios, M.; Pino, A.; Castro, J.; Bouza, C.; Martínez, P.; Rebordinos, L. Caracterización genética mediante microsatélites de Solea senegalensis (Soleidae, Pleuronectiformes) en poblaciones naturales de la costa atlántica del suroeste de la Península Ibérica. Ciencias Marinas 2012, 38, 129–142. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-38802012000100010&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. [CrossRef]

- APROMAR. Aquaculture in Spain 2024. APROMAR 2024. Available online: https://apromar.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Informe2024_v1.4.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Morais, S.; Aragão, C.; Cabrita, E.; Conceição, L.E.C.; Constenla, M.; Costas, B.; Dias, J.; Duncan, N.; Engrola, S.; Estevez, A.; et al. New developments and biological insights into the farming of Solea senegalensis reinforcing its aquaculture potential. Rev. Aquacult. 2016, 8, 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, C.E.; Brummett, R.E.; Ponzoni, R.W. Exploitation and conservation of fish genetic resources in Africa: issues and priorities for aquaculture development and research. Rev. Aquacult. 2012, 4, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvigné, F.; Lleberia, J.; Vilafranca, C.; Rosado, D.; Martins, M.; Silva, F.; González-López, W.; Ramos-Júdez, S.; Duncan, N.; Giménez, I.; et al. Gonadotropin induction of spermiation in Senegalese sole: Effect of temperature and stripping time. Aquaculture 2022, 550, 737844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, I.; Carazo, I.; Rasines, I.; Rodríguez, C.; Fernández, R.; Martínez, P.; Norambuena, F.; Chereguini, O.; Duncan, N. Reproductive performance of captive Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis, according to the origin (wild or cultured) and gender. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 17, e0608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carazo, I.; Chereguini, O.; Martín, I.; Huntingford, F.; Duncan, N. Reproductive ethogram and mate selection in captive wild senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). Span. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 14, e0401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, Á.; Martínez-Rodríguez, G.; Sarasquete, C. Male reproductive system in senegalese sole Solea senegalensis (Kaup): Anatomy, histology and histochemistry. Histol. Histopath. 2005, 20, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, E.; Soares, F.; Dinis, M.T. Characterization of Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis, male broodstock in terms of sperm production and quality. Aquaculture 2006, 261, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, E.; Soares, F.; Beirão, J.; García-López, A.; Martínez-Rodríguez, G.; Dinis, M.T. Endocrine and milt response of Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis, males maintained in captivity. Theriogenology 2001, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.M.; Cal, R.; García-López, Á.; Chereguini, O.; Kight, K.; Olmedo, M.; Sarasquete, C.; Mylonas, C.C.; Peleteiro, J.B.; Zohar, Y.; Mañanós, E.L. Effects of in vivo treatment with the dopamine antagonist pimozide and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) on the reproductive axis of Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2011, 158, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvigné, F.; González, W.; Ramos, S.; Ducat, C.; Duncan, N.; Giménez, I.; Cerdà, J. Seasonal-and dose-dependent effects of recombinant gonadotropins on sperm production and quality in the flatfish Solea senegalensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2018, 225, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Júdez, S.; González-López, W.A.; Huayanay Ostos, J.; Cota Mamani, N.; Marrero Alemán, C.; Beirâo, J.; Duncan, N. Low sperm to egg ratio required for successful in vitro fertilization in a pair-spawning teleost, Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, F.; Silva, N.; Oliveira, C.C.V.; Cabrita, E.; Gavaia, P.J. Effects of dietary supplementation with macroalgae on sperm quality and antioxidant system in Senegales sole. Aquaculture 2024, 590, 741069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatsini, E.; González, W.; Ibarra-Zatarain, Z.; Napuchi, J.; Duncan, N.J. The presence of wild Senegalese sole breeders improves courtship and reproductive success in cultured conspecifics. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, W.A.; Ramos-Júdez, S.; Duncan, N.J. Reproductive behaviour and fertilized spawns in cultured Solea senegalensis broodstock co-housed with breeders during their juvenile stages. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2024, 354, 114546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzekri, H.; Armesto, P.; Cousin, X.; Rovira, M.; Crespo, D.; Merlo, M.A.; Mazurais, D.; Bautista, R.; Guerrero-Fernández, D.; Fernandez-Pozo, N.; et al. De novo assembly, characterization and functional annotation of Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) and common sole (Solea solea) transcriptomes: integration in a database and design of a microarray. BMC Genomics 2014, 3, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Cózar, I.; Perez-Garcia, C.; Benzekri, H.; Sánchez, J.J.; Seoane, P.; Cruz, F.; Gut, M.; Zamorano, M.J.; Claros, M.G.; Manchado, M. Development of whole genome multiplex assays and construction of an integrated genetic map using SSR markers in Senegalese sole. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Cózar, I.; Gomez-Garrido, J.; Berbel, C.; Martinez-Blanch, J.F.; Alioto, T.; Claros, M.G.; Gagnaire, P.A.; Manchado, M. Chromosome anchoring in Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) reveals sex-associated markers and genome rearrangements in flatfish. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Herrán, R.; Hermida, M.; Rubiolo, J.A.; Gómez-Garrido, J.; Cruz, F.; Robles, F.; Navajas-Pérez, R.; Blanco, A.; Villamayor, P.R.; Torres, D.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly enables the identification of the follicule stimulating hormone receptor as the master sex-determining gene in the flatfish Solea senegalensis. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 00, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, D.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Mukiibi, R.; Peñaloza, C.; D’Cotta, H.; Robledo, D.; Rebordinos, L. Methylation profile of the testes of the flatfish Solea senegalensis. Aquacult. Rep. 2024, 39, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, D.; Anaya-Romero, M.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Arias-Pérez, A.; Mukiibi, R.; D’Cotta, H.; Robledo, D.; Rebordinos, L. Insights into Solea senegalensis Reproduction Through Gonadal Tissue Methylation Analysis and Transcriptomic Integration. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Romero, M.; Ramírez, D.; Arias-Pérez, A.; Rodríguez, M.E.; Robledo, D.; Rebordinos, L. Comparative transcriptomic profiling of gonads in Solea senegalensis: Exploring sex, maturity, and origin variations. Aquaculture 2025, 604, 742461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, C.J.; Popesku, J.T.; Chown, B.; Denslow, N.D.; Trudeau, V.L. Quantitative proteomics in teleost fish: Insights and challenges for neuroendocrine and neurotoxicology research. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2012, 176, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, M.; Piñeiro, C.; Martinez, I. Proteomic strategies to evaluate the impact of farming conditions on food quality and safety in aquaculture products. Foods 2020, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, S.; Tang, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Xiao, T.; Xu, B. Gonadal development and differentiation of hybrid F1 line of Ctenopharyngodon idella (♀) × Squaliobarbus curriculus (♂). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Dong, C.; Han, M.; Ma, S.; Chen, W.; Dou, J.; Feng, C.; Liu, X. Multi-omics perspective on studying reproductive biology in Daphnia sinensis. Genomics 2022, 114, 110309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, K.J.; Nesatyy, V.J.; Segner, H.; Eggen, R.I.L.; Suter, M.J.F. Global proteomics analysis of testis and ovary in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 37, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Zeng, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L. The molecular mechanism of ovary development in Thamnaconus septentrionalis induced by rising temperature via transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1556002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forné, I.; Castellana, B.; Marín-Juez, R.; Cerdà, J.; Abián, J.; Planas, J. V. Transcriptional and proteomic profiling of flatfish (Solea senegalensis) spermatogenesis. Proteomics 2011, 11, 2195–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forné, I.; Aguileiro, M.J.; Asensio, E.; Abián, J.; Cerdà, J. 2-D DIGE analysis of Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) testis proteome in wild-caught and hormone-treated F1 fish. Proteomics 2009, 9, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yan, P.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, M.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, X.; Zhu, H. Deficiency of TPPP2, a factor linked to oligoasthenozoospermia, causes subfertility in male mice. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2583–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, F.; Martínez-Herández, J.; Parra-Balaguer, P.; Llavanera, M.; Yeste, M. The Sarcoplasmic/Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is present in pig sperm and modulates their physiology over liquid preservation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Ordziniak, E.; Umer, N.; Arévalo, L.; Hinterlang, L.D.; Ziaeipour, S.; Suvilla, S.; Merges, G.E.; Schorle, H. Actin-related protein M1 (ARPM1) required for acrosome biogenesis and sperm function in mice. Preprint (bioRxiv) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Azhar, M.; Umair, M. Decoding the genes orchestrating egg and sperm fusion reactions and their roles in fertility. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, L.; Cui, Z.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ding, L.; Xu, D.; Xu, W. Proteomic analysis to explore potential mechanism underlying pseudomale sperm defect in Cynoglossus semilaevis. Aquacult. Rep. 2025, 40, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Nan, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, P.; Tan, Q. Label-free quantitative proteomic analysis reveals the characteristics of ovarian development from stage II to III in Chinese sturgeon (Acipenser sinensis). Aquaculture 2025, 597, 741928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbaugh, A. J. Physiological responses of euryhaline marine fish to naturally-occurring hypersalinity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A-Mol. Integr. Physiol 2025, 299, 111768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.H.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Radical solutions and cultural problems: could free oxygen radicals be responsible for the impaired development of preimplantation mammalian embryos in vitro? Bioessays 1994, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, G.J.; Arthur, J.R. Selenium and endocrine systems. J. Endocrinol. 2005, 184, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, M.; de los Santos, M.J.; Simón, C.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J.; Garrido, N. Effect of sperm glutathione peroxidase 1 and 4 on embryo asymmetry and blastocyst quality in oocyte donation cycles. Fertil Steril. 2006, 85, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinov, D.I.; Ayvazova, N.P.; Konova, E.I.; Atanasova, M.A. Glutathione content and glutathione peroxidase activity of sperm in males with unexplained infertility. J. Biomed. Clin. Res. 2021, 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubzens, E.; Young, G.; Bobe, J.; Cerdà, J. Oogenesis in teleosts: How fish eggs are formed. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 165, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coticchio, G.; Dal Canto, M.; Renzini, M.M.; Guglielmo, M.C.; Brambillasca, F.; Turchi, D.; Novara, P.V.; Fadini, R. Oocyte maturation: Gamete-somatic cells interactions, meiotic resumption, cytoskeletal dynamics and cytoplasmic reorganization. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 21, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupa, R.; Rodrõâguez, C.; Mylonas, C.C.; Rosenfeld, H.; Fakriadis, I.; Papadaki, M.; Peârez, J.A.; Pousis, C.; Basilone, G.; Corriero, A. Comparative study of reproductive development in wild and captive-reared greater amberjack Seriola dumerili (Risso, 1810). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e016964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, K.; Restoux, G.; Phocas, F. Genome-wide detection of positive and balancing signatures of selection shared by four domesticated rainbow trout populations (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Genet. Sel. Evol. 2024, 56, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berois, N.; Arezo, M.J.; Papa, N.G. Gamete interactions in teleost fish: the egg envelope. Basic studies and perspectives as environmental biomonitor. Bio. Res. 2011, 144, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, H.; Saito, T. Mechanisms of sperm–egg interactions: What ascidian fertilization research has taught us. Cells 2022, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S.F. Recognition of Egg and Sperm. In Developmental Biology, 6th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland (MA), 2000; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10010/.

- Okabe, M. The cell biology of mammalian fertilization. Development 2013, 140, 4471–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Xiang, Q.M.; Zhu, J.Q.; Chen, Y.E.; Tang, D.J.; Zhang, C.D.; Hou, C.C. Transport of acrosomal enzymes by KIFC1 via the acroframosomal cytoskeleton during spermatogenesis in Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Crustacea, Decapoda, Malacostracea). Animals 2022, 12, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, L.; Jones, R. Interactions between zona pellucida glycoproteins and sperm proacrosin/acrosin during fertilization. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 53, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Uchida, Y.; Kanai-Kitayama, S.; Suzuki, R.; Sato, R.; Toma, K.; Geshi, M.; Akagi, S.; Nakano, M.; Yonezawa, N. Binding of Sperm to the Zona Pellucida Mediated by Sperm Carbohydrate-Binding Proteins is not Species-Specific in vitro between Pigs and Cattle. Biomolecules 2013, 3, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaba, K. Molecular basis of sperm flagellar axonemes: structural and evolutionary aspects. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1101, 506–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, R.W.; Chemes, H.; Albertini, D.F. The axoneme: the propulsive engine of spermatozoa and cilia and associated ciliopathies leading to infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T. Axoneme Structure from Motile Cilia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrageta, D.F.; Guerra-Carvalho, B.; Sousa, M.; Barros, A.; Oliveira, P.F.; Monteiro, M.P.; Alves, M.G. Mitochondrial activation and reactive oxygen-species overproduction during sperm capacitation are independent of glucose stimuli. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavuluri, H.; Bakhtiary, Z.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Hellstrom, W.J.G. Oxidative stress-associated male infertility: Current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Medicina 2024, 60, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.; Li, H. Mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced sperm dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1520835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakawa, S.; Kraitavin, W.; Yoshitake, K.; Igarashi, Y.; Mitsuyama, S.; Kinoshita, S.; Kambayashi, D.; Watabe, S. Transcriptome analysis of yamame (Oncorhynchus masou) in normal conditions after heat stress. Biology 2019, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Lin, H. Fertility enhancement but premature ovarian failure in esr1-deficient female zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mold, D.E.; Dinitz, A.E.; Sambandan, D.R. Regulation of zebrafish zona pellucida gene activity in developing oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 81, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clelland, E.; Peng, C. Endocrine/paracrine control of zebrafish ovarian development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 312, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Pardeshi, L.; Chen, Y.; Ge, W. Transcriptomic analysis for differentially expressed genes in ovarian follicle activation in the zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugananthkumar, R.; Sudhakumari, C.C. Understanding the impact of stress on teleostean reproduction. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Chu, P.; Han, B.; Ning, X.; Wang, T.; Yin, S. Acute cold stress leads to zebrafish ovarian dysfunction by regulating miRNA and mRNA. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics 2023, 48, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litscher, E.S.; Williams, Z.; Wassarman, P.M. Zona pellucida glycoprotein ZP3 and fertilization in mammals. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, B.; Srivastava, N.; Kumar, M.S.; Kumar, R. Protein-protein networks analysis of differentially expressed genes unveils the key phenomenon of biological process with respect to reproduction in endangered catfish, C. magur. Gene 2023, 860, 147235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Replicas | Origin1 | Sex2 | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1F-1, F1F-2, F1F-3, F1F-4, F1F-5 | 5 | F1 | F | F1F |

| F1M-1, F1M-2, F1M-3, F1M-4, F1M-5 | 5 | F1 | M | F1M |

| wtF-1, wtF-2, wtF-3, wtF4, wtF-5 | 5 | wt | F | wtF |

| wtM-1, wtM-2, wtM-3 | 3 | wt | M | wtM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).