Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

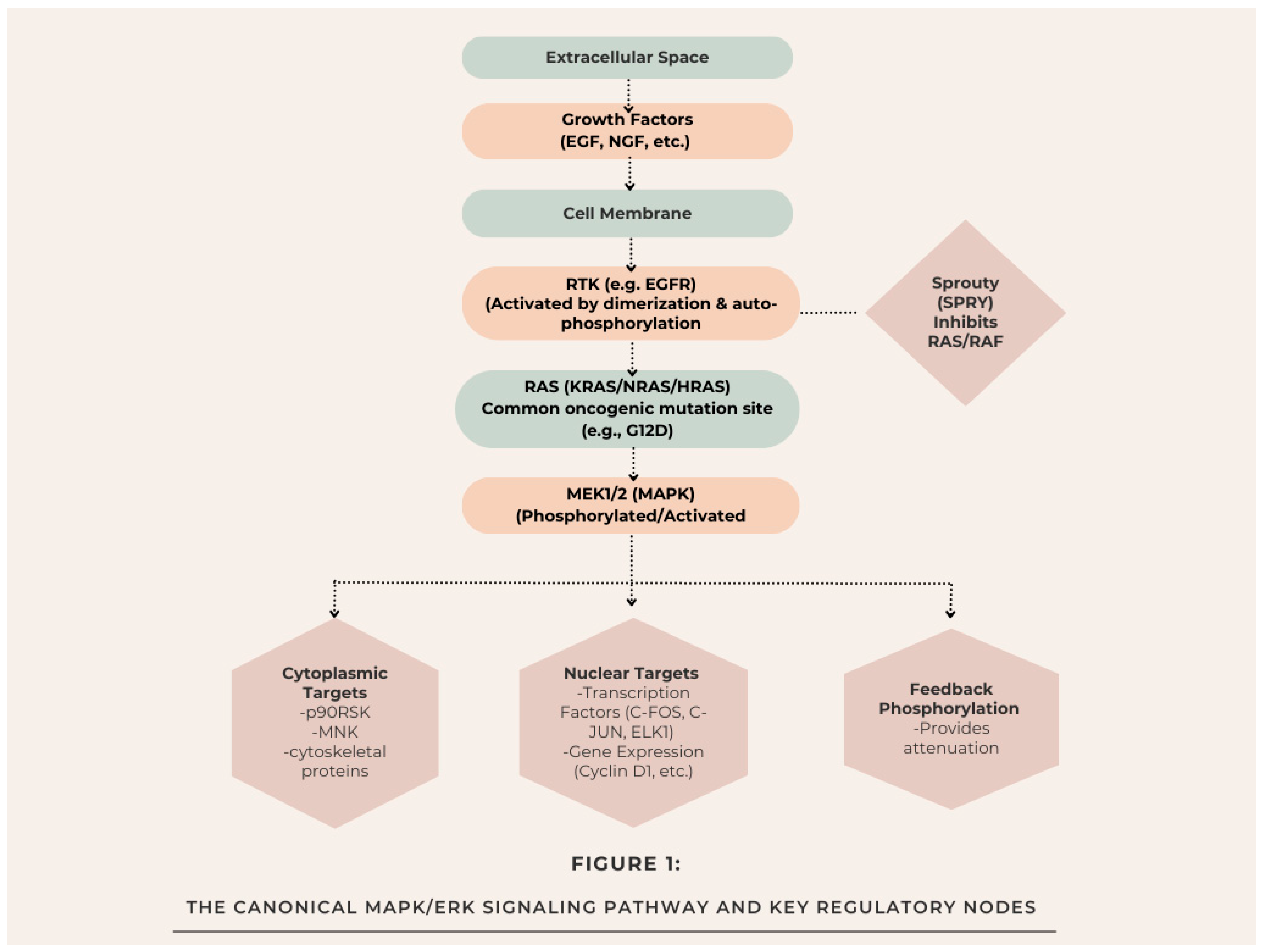

2. The Canonical MAPK/ERK Pathway and Its Regulation

- Dual-specificity phosphatases (DUSPs): There's a group of enzymes that help turn off ERK by removing its phosphate groups, acting like an important off-switch [16].

- Sprouty (SPRY) proteins: These proteins inhibit RAS activation and RAF membrane recruitment, often acting as tumor suppressors [17].

- Feedback phosphorylation: ERK can add phosphate groups to earlier components such as SOS and RAF, which in turn creates feedback loops that decrease the signaling [18].

3. Oncogenic Hijacking: The MAPK/ERK Pathway in Cancer Development

3.1. Key Mutations and Driver Events

3.2. Role in Tumor Hallmarks: Proliferation, Survival, EMT, and Metastasis

3.3. Shaping the Tumor Microenvironment

| Cancer Type | RAS Mutation Frequency | BRAF Mutation Frequency | MEK (MAP2K1/2) Mutation Frequency | Primary Alterations & Notes |

| Melanoma | 15-30% (NRAS) [32,33] | 40-50% (V600E/K) [12] | 5-8% [34] | BRAF V600 is the classic driver; it defines a major therapeutic subtype. |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | ~40% (KRAS) [22] | 8-12% (V600E) [23] | <2% [35] | KRAS mutations predict resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | 25-30% (KRAS) [22] | 2-4% (V600E & non-V600) [36] | Rare | KRAS G12C is a recent therapeutic target. BRAF V600E defines a small subset. |

| Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) | >90% (KRAS) [22] | Rare | Rare | KRAS mutation is near-universal and a critical early event. |

| Thyroid Cancer (Papillary) | 10-20% (NRAS, HRAS) [37] | 45-60% (V600E) [37] | Rare | BRAF V600E correlates with aggressive features. |

| Ovarian Cancer (Low-Grade Serous) | 20-35% (KRAS) [38] | 30-50% (BRAF) [38] | Reported [39] | Distinct from high-grade serous, mutations are common in this subtype. |

| Hairy Cell Leukemia | Very Rare | ~100% (V600E) [40] | N/A | BRAF V600E is a disease-defining genetic lesion. |

4. The Signaling Nexus of Pain: MAPK/ERK in Nociception and Sensitization

4.1. Peripheral Sensitization: From Inflammation to Injury

4.2. Central Sensitization: Spinal Cord and Supraspinal Plasticity

- Enhancing Synaptic Efficacy: Adding phosphate groups to postsynaptic receptors, like NMDA and AMPA receptors, helps control their activity and encourages them to be inserted into the membrane, which in turn boosts the strength of synaptic transmission [46].

- Regulating Transcription: It's about getting to the nucleus to trigger the expression of pain-related genes like c-Fos, Cox-2, and prodynorphin, which can result in lasting changes in function [47].

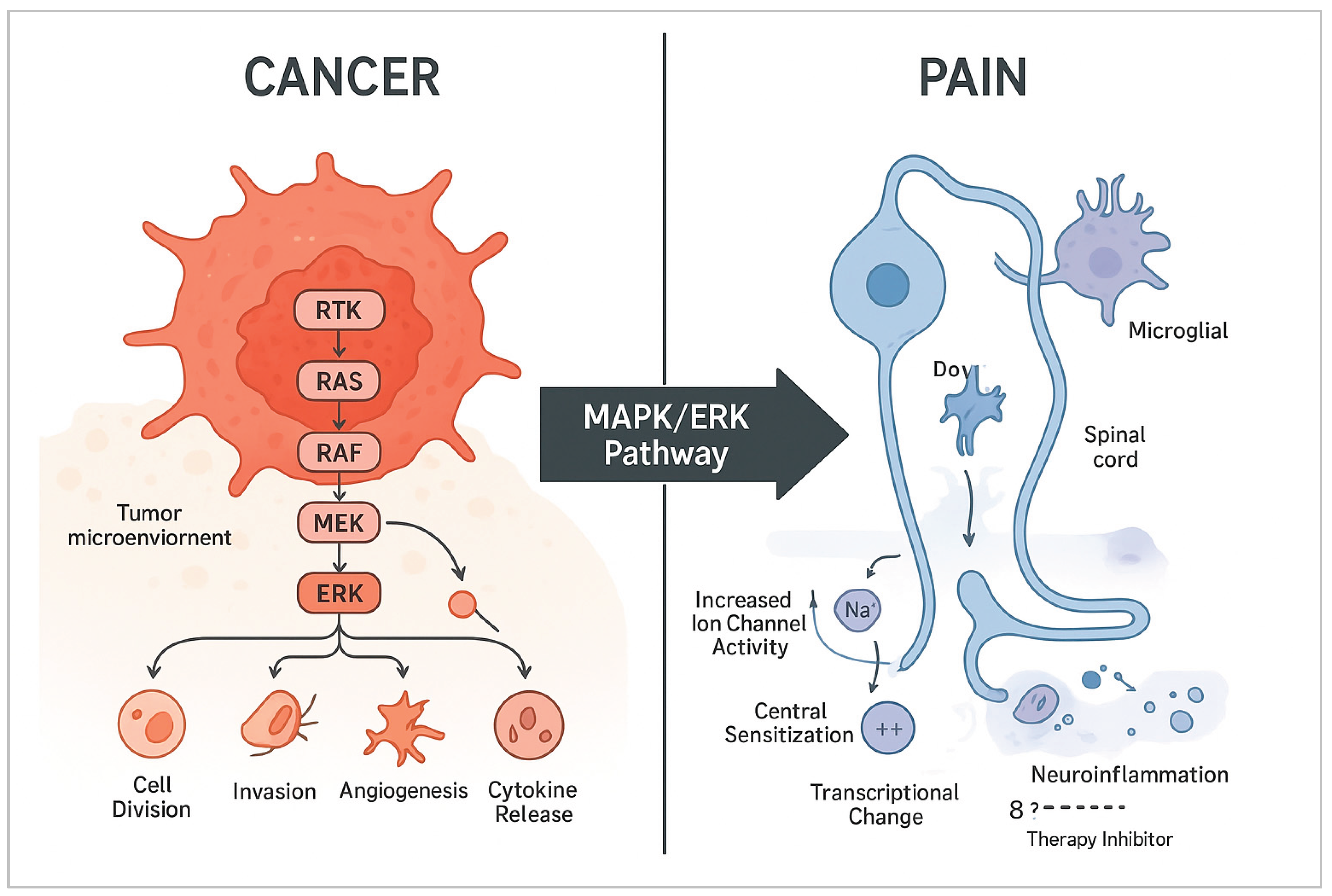

5. Convergence: The MAPK/ERK Axis as a Shared Hub in Cancer and Pain

5.1. Mechanistic Overlap in Cellular Processes

- Amplifies Inflammatory Signaling: In the tumor microenvironment and nervous system, when ERK gets activated in immune cells like macrophages and in glial cells such as microglia and astrocytes, it triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. This sets off a feedback loop that not only encourages tumor growth but also increases pain sensitivity at the same time [48,49].

5.2. Clinical Intersection: Cancer-Induced and Therapy-Induced Pain

6. Therapeutic Targeting of the MAPK/ERK Axis

6.1. MAPK/ERK Inhibitors in Clinical Oncology: A Comprehensive List

6.2. Evidence for MAPK/ERK Modulation in Pain Management

6.3. Challenges: Resistance, Toxicity, and the Therapeutic Window

References

- Shaul, Y.D.; Seger, R. The MEK/ERK cascade: From signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2007, 1773, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, M.M.; Morrison, D.K. Integrating signals from RTKs to ERK/MAPK. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Ian A.; Hood, Fiona E.; Hartley, James L. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer research 2020, 80.14, 2969–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, U.; Wang, M.; Hu, J. Targeting Aberrant RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK Signaling for Cancer Therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.-R.; Gereau, R.W.; Malcangio, M.; Strichartz, G.R. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res. Rev. 2009, 60, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obata, K.; Noguchi, K. MAPK activation in nociceptive neurons and pain hypersensitivity. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 2643–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Gerner, P.; Woolf, C.J.; Ji, R.-R. ERK is sequentially activated in neurons, microglia, and astrocytes by spinal nerve ligation and contributes to mechanical allodynia in this neuropathic pain model. Pain 2005, 114, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantyh, Patrick. Bone cancer pain: causes, consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. PAIN® 2013, 154, S54–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, B.L.; Hamamoto, D.T.; Simone, D.A.; Wilcox, G.L. Mechanism of Cancer Pain. Mol. Interv. 2010, 10, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamsky, K.; Weizer, O.; Amariglio, N. Bibliography Current World Literature Vol 12 No 2 March 2005. Clinical Genetics 2004, 65, 378–383. [Google Scholar]

- Simanshu, D.K.; Nissley, D.V.; McCormick, F. RAS Proteins and Their Regulators in Human Disease. Cell 2017, 170, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, Robert, Jr. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacological research 2012, 66.2, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, R.; Blenis, J. The RSK family of kinases: emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.O.; Blenis, J. MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caunt, Christopher J.; Keyse, Stephen M. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) Shaping the outcome of MAP kinase signalling. The FEBS journal 2013, 280.2, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.M.; Morrison, D.J.; Basson, M.A.; Licht, J.D. Sprouty proteins: multifaceted negative-feedback regulators of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, D.; Corrêa, S.A.L.; Müller, J. Negative feedback regulation of the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 4397–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.C.; Er, E.E.; Blenis, J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lito, P.; Rosen, N.; Solit, D.B. Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Mina, M.; Armenia, J.; Chatila, W.K.; Luna, A.; La, K.C.; Dimitriadoy, S.; Liu, D.L.; Kantheti, H.S.; Saghafinia, S.; et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.D.; Fesik, S.W.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Luo, J.; Der, C.J. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission Possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 828–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Yaeger, R.; Rodrik-Outmezguine, V.S.; Tao, A.; Torres, N.M.; Chang, M.T.; Drosten, M.; Zhao, H.; Cecchi, F.; Hembrough, T.; et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 2017, 548, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarden, Y.; Pines, G. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloche, S.; Pouysségur, J. The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3227–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmanno, K.; Cook, S.J. Tumour cell survival signalling by the ERK1/2 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 16, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.B.; Nabha, S.M.; Atanaskova, N. Role of MAP kinase in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003, 22, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, K.N.; Bryant, P.; Pumiglia, K. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Induction of the Angiogenic Phenotype Requires Ras Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 49289–49298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.; Nguyen, T.; Gundre, E.; Ogunlusi, O.; El-Sobky, M.; Giri, B.; Sarkar, T.R. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: The chief architect in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1089068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu-Lieskovan, Siwen; et al. Improved antitumor activity of immunotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF V600E melanoma. Science translational medicine 2015, 7.279, 279ra41–279ra41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombino, M.; Capone, M.; Lissia, A.; Cossu, A.; Rubino, C.; De Giorgi, V.; Massi, D.; Fonsatti, E.; Staibano, S.; Nappi, O.; et al. BRAF/NRAS Mutation Frequencies Among Primary Tumors and Metastases in Patients With Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2522–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlundh-Rose, E.; Egyházi, S.; Omholt, K.; Månsson-Brahme, E.; Platz, A.; Hansson, J.; Lundeberg, J. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: a study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006, 16, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I Nikolaev, S.; Rimoldi, D.; Iseli, C.; Valsesia, A.; Robyr, D.; Gehrig, C.; Harshman, K.; Guipponi, M.; Bukach, O.; Zoete, V.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2011, 44, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, A.K.; Dong, J.; Xie, J.; Xing, M. MEK1 mutations, but not ERK2 mutations, occur in melanomas and colon carcinomas, but none in thyroid carcinomas. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardarella, S.; Ogino, A.; Nishino, M.; Butaney, M.; Shen, J.; Lydon, C.; Yeap, B.Y.; Sholl, L.M.; Johnson, B.E.; Jänne, P.A. Clinical, Pathologic, and Biologic Features Associated with BRAF Mutations in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4532–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M. B. R. A. F. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocrine-related cancer 2005, 12.2, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, G.; Oldt, R., III; Cohen, Y.; Wang, B.G.; Sidransky, D.; Kurman, R.J.; Shih, I.-M. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS Characterize the Development of Low-Grade Ovarian Serous Carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Wang, T.-L.; Shih, I.-M.; Mao, T.-L.; Nakayama, K.; Roden, R.; Glas, R.; Slamon, D.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Vogelstein, B.; et al. Frequent Mutations of Chromatin Remodeling Gene ARID1A in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Science 2010, 330, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiacci, Enrico; et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2011, 364.24, 2305–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.-R.; Xu, Z.-Z.; Gao, Y.-J. Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezet, S.; McMahon, S.B. NEUROTROPHINS: Mediators and Modulators of Pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 507–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Oxford, G.S. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways mediate acute NGF sensitization of TRPV1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007, 34, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudmon, A.; Choi, J.-S.; Tyrrell, L.; Black, J.A.; Rush, A.M.; Waxman, S.G.; Dib-Hajj, S.D. Phosphorylation of Sodium Channel Nav1.8 by p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Increases Current Density in Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3190–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Kohno, T.; Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Brenner, G.J.; Wang, H.; Van Der Meer, C.; Befort, K.; Woolf, C.J.; Ji, R.-R. Ionotropic and Metabotropic Receptors, Protein Kinase A, Protein Kinase C, and Src Contribute to C-Fiber-Induced ERK Activation and cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein Phosphorylation in Dorsal Horn Neurons, Leading to Central Sensitization. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 8310–8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Qiu, C.-S.; Kim, S.J.; Muglia, L.; Maas, J.W.; Pineda, V.V.; Xu, H.-M.; Chen, Z.-F.; Storm, D.R.; Muglia, L.J.; et al. Genetic Elimination of Behavioral Sensitization in Mice Lacking Calmodulin-Stimulated Adenylyl Cyclases. Neuron 2002, 36, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.-R.; Befort, K.; Brenner, G.J.; Woolf, C.J. ERK MAP Kinase Activation in Superficial Spinal Cord Neurons Induces Prodynorphin and NK-1 Upregulation and Contributes to Persistent Inflammatory Pain Hypersensitivity. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Wen, Y.-R.; Zhang, D.-R.; Borsello, T.; Bonny, C.; Strichartz, G.R.; Decosterd, I.; Ji, R.-R. A Peptide c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase (JNK) Inhibitor Blocks Mechanical Allodynia after Spinal Nerve Ligation: Respective Roles of JNK Activation in Primary Sensory Neurons and Spinal Astrocytes for Neuropathic Pain Development and Maintenance. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 3551–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-J.; Ji, R.-R. Targeting Astrocyte Signaling for Chronic Pain. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantyh, P.W. The neurobiology of skeletal pain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-Q.; Wu, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-F.; Wu, A.-M. Neurophysiological mechanisms of cancer-induced bone pain. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 35, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.R.; Woolf, C.J. Neuronal Plasticity and Signal Transduction in Nociceptive Neurons: Implications for the Initiation and Maintenance of Pathological Pain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, N.P.; Grisold, A.; Grisold, W.; Windebank, A.J. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A current review. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.-Y.; Xu, H.; Clapham, D.E.; Ji, R.-R. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Activates ERK in Primary Sensory Neurons and Mediates Inflammatory Heat Hyperalgesia through TRPV1 Sensitization. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 8300–8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, T.; Shen, M.; Xu, J.; Gao, W.; Pan, J.; Wei, L.; Su, H.; et al. Esketamine inhibits the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in the spinal dorsal horn to relieve bone cancer pain in rats. Mol. Pain 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchook, G.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Infante, J.R.; Gordon, M.S.; Vogelzang, N.J.; DeMarini, D.J.; Sun, P.; Moy, C.; A Szabo, S.; Roadcap, L.T.; et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Marcus, L.J.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Martin, S.; Aschbacher-Smith, L.E.; Rizvi, T.A.; et al. Activity of Selumetinib in Neurofibromatosis Type 1–Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. New Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2550–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lito, P.; Rosen, N.; Solit, D.B. Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Karaszewska, B.; Schachter, J.; Rutkowski, P.; Mackiewicz, A.; Stroiakovski, D.; Lichinitser, M.; Dummer, R.; Grange, F.; Mortier, L.; et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Drug Name (Examples) | Status (Key Indications) | Notable Clinical Context |

| BRAF (Monotherapy) | Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, Encorafenib | FDA-Approved: *BRAF V600E/K* mutant Melanoma, NSCLC, Thyroid Cancer. | First-generation inhibitors: effective but prone to resistance. Encorafenib is often used in combination for CRC. |

| MEK1/2 (Monotherapy) | Trametinib, Cobimetinib, Binimetinib, Selumetinib | FDA-Approved: Trametinib/Cobi/Bini for BRAF mutant Melanoma (in combo). Selumetinib: Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1). | Selumetinib shows activity in low-grade serous ovarian cancer and pediatric gliomas. |

| BRAF + MEK (Combination) | Dabrafenib + Trametinib, Vemurafenib + Cobimetinib, Encorafenib + Binimetinib | FDA-Approved: Standard of care for BRAF mutant Melanoma, NSCLC. Encorafenib+Binimetinib is also for CRC. | Combination improves efficacy, reduces cutaneous toxicities (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma) vs. BRAF monotherapy. |

| ERK1/2 (Direct) | Ulixertinib (BVD-523), MK-8353, LY3214996 | Phase I/II Trials (Various solid tumors, incl. BRAF/NRAS mutant). | Designed to overcome resistance to upstream BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Emerging safety and efficacy data. |

| RAF (Pan-RAF or Paradox Breaker) | LXH254, Tovorafenib (DAY101) | Clinical Trials. Tovorafenib in pediatric low-grade glioma. | Aim to inhibit all RAF isoforms or avoid paradoxical activation in RAS-mutant cells. |

| SHP2 (Upstream Node) | RMC-4630, TNO155 | Phase I/II Trials (e.g., with Osimertinib in NSCLC, with MEKi in KRAS mutants). | Targets node connecting RTKs to RAS; potential in KRAS-driven and resistant cancers. |

| Compound / Drug Class | Target | Pain Model (Example) | Observed Analgesic Effect & Proposed Mechanism |

| U0126, PD0325901 | MEK1/2 | Neuropathic pain (SNL, CCI), Inflammatory pain (CFA), Cancer-induced bone pain. | Reversal of mechanical allodynia & thermal hyperalgesia. ↓ p-ERK in DRG/spinal cord; ↓ cytokine production in glia. |

| SL327 | MEK1/2 | Formalin test, Capsaicin-induced hyperalgesia. | Attenuation of phase 2 formalin response & capsaicin-evoked sensitization. Blocks central sensitization. |

| ASN007 (ERK1/2 inhibitor) | ERK1/2 | Inflammatory pain (CFA). | Dose-dependent reduction in pain hypersensitivity. More direct target than MEK inhibitors. |

| Schwann Cell-derived Exosomes | N/A (Modulate pathway) | Neuropathic pain (SNI). | Alleviate pain by delivering miRNAs that suppress RAS/MAPK signaling in neurons. |

| Peripheral Opioids (e.g., Morphine) | µ-opioid receptor (Gᵢ) | Various | Analgesia is partly via inhibition of cAMP/PKA, leading to reduced downstream ERK activation in neurons. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).