Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Signs

3. Diagnosis

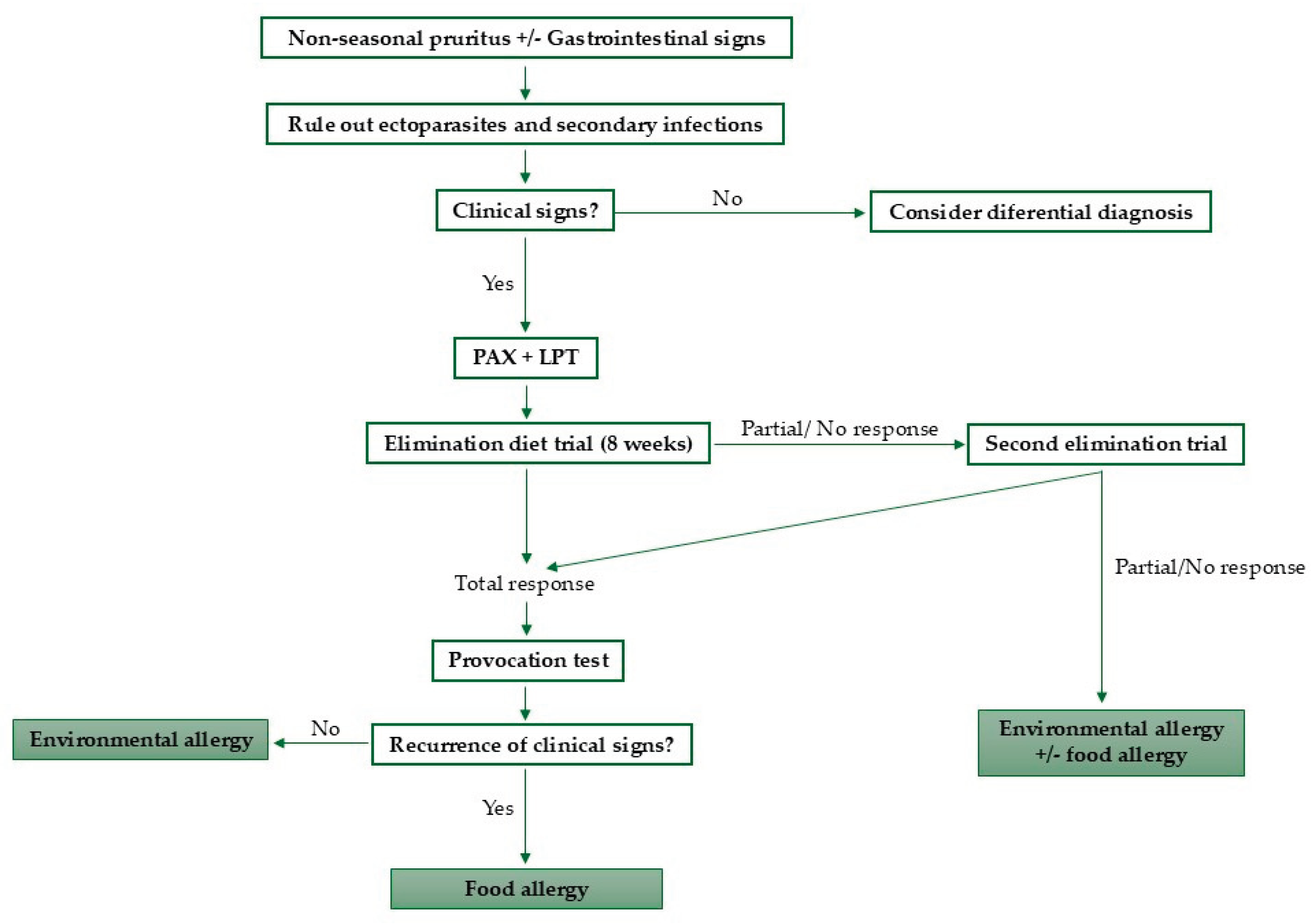

3.1. Elimination-Provocation Test

3.2. Other Diagnostic Tests

4. Therapeutic Approaches

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| PAX | Pet Allergy Xplorer |

| LPT | Lymphocyte Proliferation Test |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

References

- Mueller, R.S.; Unterer, S. Adverse Food Reactions: Pathogenesis, Clinical Signs, Diagnosis and Alternatives to Elimination Diets. Vet. J. 2018, 236, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, R.; Pucheu-Haston, C.M.; Olivry, T.; Prost, C.; Jackson, H.; Banovic, F.; Nuttall, T.; Santoro, D.; Bizikova, P.; Mueller, R.S. Feline Allergic Diseases: Introduction and Proposed Nomenclature. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32, 8–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, H.A. Food Allergy in Dogs and Cats; Current Perspectives on Etiology, Diagnosis, and Management. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Mueller, R. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (3): Prevalence of Cutaneous Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs and Cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 4 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Mueller, R.S. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (7): Signalment and Cutaneous Manifestations of Dogs and Cats with Adverse Food Reactions. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudebush, P. Ingredients and Foods Associated with Adverse Reactions in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Dermatol. 2013, 24, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.; Olivry, T.; Prélaud, P. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (2): Common Food Allergen Sources in Dogs and Cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 7 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łoś-Rycharska, E.; Gołębiewski, M.; Grzybowski, T.; Rogalla-Ładniak, U.; Krogulska, A. The Microbiome and Its Impact on Food Allergy and Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2020, 37, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, M.; Masuda, K.; Hayashiya, M.; Okayama, T. Flow Cytometric Analysis of Lymphocyte Proliferative Responses to Food Allergens in Dogs with Food Allergy. J. Vet. Med. Sci. Jpn. Soc. Vet. Sci. 2011, 73, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaschen, F.P.; Merchant, S.R. Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2011, 41, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J.; Frank, L.A. Food Allergy in the Cat: A Diagnosis by Elimination. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2010, 12, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, F.; Zini, E.; Nett, C.; Naegeli, C.; Bigler, B.; Rüfenacht, S.; Roosje, P.; Gutzwiller, M.E.R.; Wilhelm, S.; Pfister, J.; et al. A Prospective Study on Canine Atopic Dermatitis and Food-Induced Allergic Dermatitis in Switzerland. Vet. Dermatol. 2008, 19, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.S.; Olivry, T. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (6): Prevalence of Noncutaneous Manifestations of Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs and Cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 13 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobi, S.; Linek, M.; Marignac, G.; Olivry, T.; Beco, L.; Nett, C.; Fontaine, J.; Roosje, P.; Bergvall, K.; Belova, S.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Causes of Pruritus in Cats: A Multicentre Study on Feline Hypersensitivity-Associated Dermatoses. Vet. Dermatol. 2011, 22, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivry, T.; Mueller, R.; Prélaud, P. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (1): Duration of Elimination Diets. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 15 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.; Simpson, A.; Bloom, P.; Diesel, A.; Friedeck, A.; Paterson, T.; Wisecup, M.; Yu, C.-M. 2023 AAHA Management of Allergic Skin Diseases in Dogs and Cats Guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2023, 16 59, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Mueller, R. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (5): Discrepancies between Ingredients and Labeling in Commercial Pet Foods. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 17 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, E.; Soto Del Rio, M. de L.D.; Dalmasso, A.; Bottero, M.T.; Schiavone, A.; Prola, L. Cross-Contamination in Canine and Feline Dietetic Limited-Antigen Wet Diets. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 18 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, R.; Conficoni, D.; Morelli, G.; Losasso, C.; Alberghini, L.; Giaccone, V.; Ricci, A.; Andrighetto, I. Undeclared Animal Species in Dry and Wet Novel and Hydrolyzed Protein Diets for Dogs and Cats Detected by Microarray Analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, C.G.L.; Marchi, P.H.; Amaral, A.R.; Príncipe, L. de A.; do Carmo, A.A.; Zafalon, R.V.A.; Miyamoto, N.N.; Garcia, N.A.C.R.; Balieiro, J.C. de C.; Vendramini, T.H.A. An Assessment of the Impact of Insect Meal in Dry Food on a Dog with a Food Allergy: A Case Report. Anim. Open Access J. MDPI 2024, 14, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, H.A.; Dembele, V. Conducting a Successful Diet Trial for the Diagnosis of Food Allergy in Dogs and Cats. Vet. Dermatol. 2024, 35, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesponne, I.; Naar, J.; Planchon, S.; Serchi, T.; Montano, M. DNA and Protein Analyses to Confirm the Absence of Cross-Contamination and Support the Clinical Reliability of Extensively Hydrolysed Diets for Adverse Food Reaction-Pets. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.; Moore, G.; Laporte, C.; Daristotle, L.; Frantz, N. Evaluation of Hydrolyzed Salmon and Hydrolyzed Poultry Feather Diets in Restrictive Diet Trials for Diagnosis of Food Allergies in Pruritic Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 23 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, K.; Sato, A.; Tanaka, A.; Kumagai, A. Hydrolyzed Diets May Stimulate Food-Reactive Lymphocytes in Dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2020, 82, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favrot, C.; Bizikova, P.; Fischer, N.; Rostaher, A.; Olivry, T. The Usefulness of Short-course Prednisolone during the Initial Phase of an Elimination Diet Trial in Dogs with Food-induced Atopic Dermatitis. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 25 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, N.; Spielhofer, L.; Martini, F.; Rostaher, A.; Favrot, C. Sensitivity and Specificity of a Shortened Elimination Diet Protocol for the Diagnosis of Food-induced Atopic Dermatitis (FIAD). Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 27; Olivry, T.; Mueller, R.S. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (9): Time to Flare of Cutaneous Signs after a Dietary Challenge in Dogs and Cats with Food Allergies. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimakura, H.; Kawano, K. Results of Food Challenge in Dogs with Cutaneous Adverse Food Reactions. Vet. Dermatol. 2021, 28 32, 293–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lozano, C.; Mas-Fontao, A.; Auxilia, S.; Welters, M.; Olivrī, A.; Mueller, R.; Olivry, T. Evaluation of a Direct Lymphocyte Proliferation Test for the Diagnosis of Canine Food Allergies with Delayed Reactions after Oral Food Challenge. Vet. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, J.; Griffin, C.; Sheinberg, G.; Griffin, J.; Cross, E.; Gagné, J.; Romero, A. An Open-label Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of an Elemental Diet for the Diagnosis of Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2023, 30 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.M.; Campos, I.; Antunes, C.; Costa, A.; Valdevira, A.; Bento, O. Testes intradérmicos e imunodots podem ser úteis no diagnostico de alergia canina a carne – Intradermal testing and immunodot may be useful in diagnosing dog allergy to meat. Rev Port Imunoalergologia 2019, 27(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, C.; Mariani, C.; Mueller, R.S. Evaluation of Canine Adverse Food Reactions by Patch Testing with Single Proteins, Single Carbohydrates and Commercial Foods. Vet. Dermatol. 2017, 32 28, 473–e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Possebom, J.; Cruz, A.; Gmyterco, V.C.; de Farias, M.R. Combined Prick and Patch Tests for Diagnosis of Food Hypersensitivity in Dogs with Chronic Pruritus. Vet. Dermatol. 2022, 33 33, 124–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, E.; Matricoti, I.; Noli, C. An Assessment of a Western Blot Method for the Investigation of Canine Cutaneous Adverse Food Reactions. Vet. Dermatol. 2018, 29, 217–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favrot, C.; Linek, M.; Fontaine, J.; Beco, L.; Rostaher, A.; Fischer, N.; Couturier, N.; Jacquenet, S.; Bihain, B.E. Western Blot Analysis of Sera from Dogs with Suspected Food Allergy. Vet. Dermatol. 2017, 28, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, R.; Olivry, T. Critically Appraised Topic on Adverse Food Reactions of Companion Animals (4): Can We Diagnose Adverse Food Reactions in Dogs and Cats with in Vivo or in Vitro Tests? BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 36 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.T.H.; Johnson, L.N.; Heinze, C.R. Assessment of the Clinical Accuracy of Serum and Saliva Assays for Identification of Adverse Food Reaction in Dogs without Clinical Signs of Disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, E.; Leistra, M.H.G.; Sinke, J.; Vroom, M.W.; Savelkoul, H.; Hendriks, W.H. Measurement of Allergen-Specific IgG in Serum Is of Limited Value for the Management of Dogs Diagnosed with Cutaneous Adverse Food Reactions. Vet. J. 2017, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivry, T.; Fontao, A.; Aumayr, M.; Ivanovova, N.; Mitterer, G.; Harwanegg, C. Validation of a Multiplex Molecular Macroarray for the Determination of Allergen-Specific IgE Sensitizations in Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suto, A.; Suto, Y.; Onohara, N.; Tomizawa, Y.; Yamamoto-Sugawara, Y.; Okayama, T.; Masuda, K. Food Allergens Inducing a Lymphocyte-Mediated Immunological Reaction in Canine Atopic-like Dermatitis. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2015, 77, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, E.; Cox, E. A Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo Controlled Trial of the Efficacy, Quality of Life and Safety of Food Allergen-Specific Sublingual Immunotherapy in Client Owned Dogs with Adverse Food Reactions: A Small Pilot Study. Vet. Dermatol. 2016, 41 27, 361–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, E.; Pelst, M.; Hesta, M.; Cox, E. Food-Specific Sublingual Immunotherapy Is Well Tolerated and Safe in Healthy Dogs: A Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 42 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagoa, T.; Martins, L.; Queiroga, M.C. Microbiota Modulation as an Approach to Prevent the Use of Antimicrobials Associated with Canine Atopic Dermatitis. Biomedicines. 2025, 43 13, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noli, C.; Varina, A.; Barbieri, C.; Pirola, A.; Olivero, D. Analysis of Intestinal Microbiota and Metabolic Pathways before and after a 2-Month-Long Hydrolyzed Fish and Rice Starch Hypoallergenic Diet Trial in Pruritic Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).