1. Introduction

On 20 January 2025, the European Commission approved UV-treated powder derived from

Tenebrio molitor (Tm) larvae as a food ingredient for the general population under regulated conditions [

1]. This decision aligns with the growing interest in edible insects (EI) as a sustainable protein source, yet it also raises concerns regarding allergenicity. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has highlighted potential risks, particularly for individuals with pre-existing allergies to crustaceans, dust mites, mollusks, or components found in insect feed, mandating specific labeling requirements to mitigate these concerns and ensure consumer safety [

2].

The allergenic potential of edible insects (EI) is of particular interest due to their evolutionary proximity to crustaceans and Acari, both of which contain well-characterized allergens. Research has identified proteins such as tropomyosin (TM), α-amylase, and arginine kinase (AK) as major pan-allergens capable of eliciting immune responses. These proteins exhibit IgE-binding cross-reactivity with homologous allergens found in arthropods (e.g., mites, crustaceans), mollusks, and even certain nematodes [

3,

4]. As a result, individuals with shellfish allergies may be at risk of severe allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, when consuming edible insects. While the link between EI consumption and crustacean allergies is well established, the impact of insect-derived allergens on individuals with mite allergies remains less clear, prompting further investigation [

5,

6].

The concept of mite-EI syndrome is gaining attention in allergology as an increasing number of individuals sensitized to house dust mites (HDM) and storage mites report allergic reactions to insect-based foods [

7,

8]. Given the strong cross-reactivity between mites, crustaceans, and insects, ingestion of edible insect products could trigger symptoms ranging from mild oral allergy syndrome to life-threatening anaphylaxis [

9,

10]. Documented cases indicate that individuals with known HDM or crustacean allergies may later develop sensitization to mealworms, grasshoppers, or other edible insects, yet it remains uncertain whether mite sensitization alone is sufficient to induce a true food allergy [

11,

12]. The clinical significance of this cross-reactivity and its potential to contribute to allergic disease burden require further exploration [

13].

Beyond individual sensitization patterns, the allergen exposome—comprising environmental factors such as climate, urbanization, dietary habits, microbiota composition, and exposure to pollutants—plays a crucial role in shaping immune responses [

14,

15]. Geographic variability influences specific IgE (sIgE) profiles, potentially affecting the prevalence and severity of edible insect allergies across different populations. Regions with high, year-round exposure to HDM and storage mites may exhibit distinct sensitization patterns compared to areas where such exposure is less prevalent [

16,

17].

In this context, our study aims to characterize the molecular profile of individuals sensitized to EI despite no prior conscious exposure. Conducted within a subtropical region with persistent HDM and storage mite exposure, yet relatively low rates of intestinal parasitic infections and cockroach sensitization, this research seeks to clarify the clinical relevance of mite-related cross-reactivity and contribute to a broader understanding of emerging food allergies associated with entomophagy [

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Between March and September 2024, we conducted a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients attending the Outpatient Allergy Clinic, Immunotherapy, and Severe Asthma Unit at Hospital Universitario de Canarias in Tenerife, Spain. Eligible participants were required to exhibit IgE-mediated reactivity, as determined by a molecular allergen diagnostic platform, and have a clinical history suggestive of allergy-mediated disease. Sensitization to at least one insect extract—migratory locust (Locusta migratoria, Lm), house cricket (Acheta domesticus, Ad), or mealworm (Tenebrio molitor, Tm)—as detected through IgE microarray analysis, defined the study subgroup for data evaluation. This investigation received approval from the local Ethical Committee (approval code CHUC 2023 66). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, with parental or guardian consent required for individuals under 18 years of age.

Clinical data were extracted from patients’ medical records, including sociodemographic information, clinical history -encompassing past medical conditions and current allergy diagnoses-, and medication details. The severity and stage of allergic diseases were assessed following established guidelines [

20,

21]. Patients who had previously undergone or were currently receiving allergen immunotherapy or monoclonal antibody (biologic) treatment were excluded. Additionally, pregnant, and breastfeeding women were not included in the study.

2.2. Serological Analysis

Blood samples were collected from all participants, assigned unique identification codes, and stored at -40°C until analysis. Samples were thawed immediately before in vitro testing. Total and sIgE levels were measured using the ALEX²

® MacroArray platform (MacroArray Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria) following the manufacturer’s protocol. This multiplex assay includes 282 reagents, comprising 157 whole allergens—among them extracts from Ad, Lm, and Tm—as well as 125 molecular components. These allergens are immobilized on polystyrene nanobeads and deposited onto a nitrocellulose membrane, as previously described [

22].

Total IgE levels were reported in international units per milliliter (IU/mL), while sIgE levels were expressed in kUA/L, with values ≥ 0.3 kUA/L considered positive. The assay included 17 molecular allergens derived from mites: Der p 1, Der p 2, Der p 5, Der p 7, Der p 10, Der p 11, Der p 20, Der p 21, Der p 23, Der f 1, Der f 2, Blo t 5, Blo t 10, Blo t 21, Lep d 2, Gly d 2, and Tyr p 2. Additionally, the microarray incorporated panallergens classified according to their reactivity profiles.

Tropomyosin reactivity was defined by the presence of IgE antibodies targeting Ani s 3, Blo t 10, Der p 10, Pen m 1, or Per a 7. Sensitization to AK was identified through reactivity to at least one of the following molecules: Pen m 2, Bla g 9, or Der p 20. Further markers assessed included Pen m 3 (myosin light chain), Pen m 4 (sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein), Cra c 6 (troponin C), and Der p 11 (paramyosin).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized using medians and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Group differences were analyzed using appropriate statistical tests: Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to parametric continuous variables, while the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests were used for nonparametric continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05. To assess allergen associations, simple logistic regression was performed, adjusting for potential confounding variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

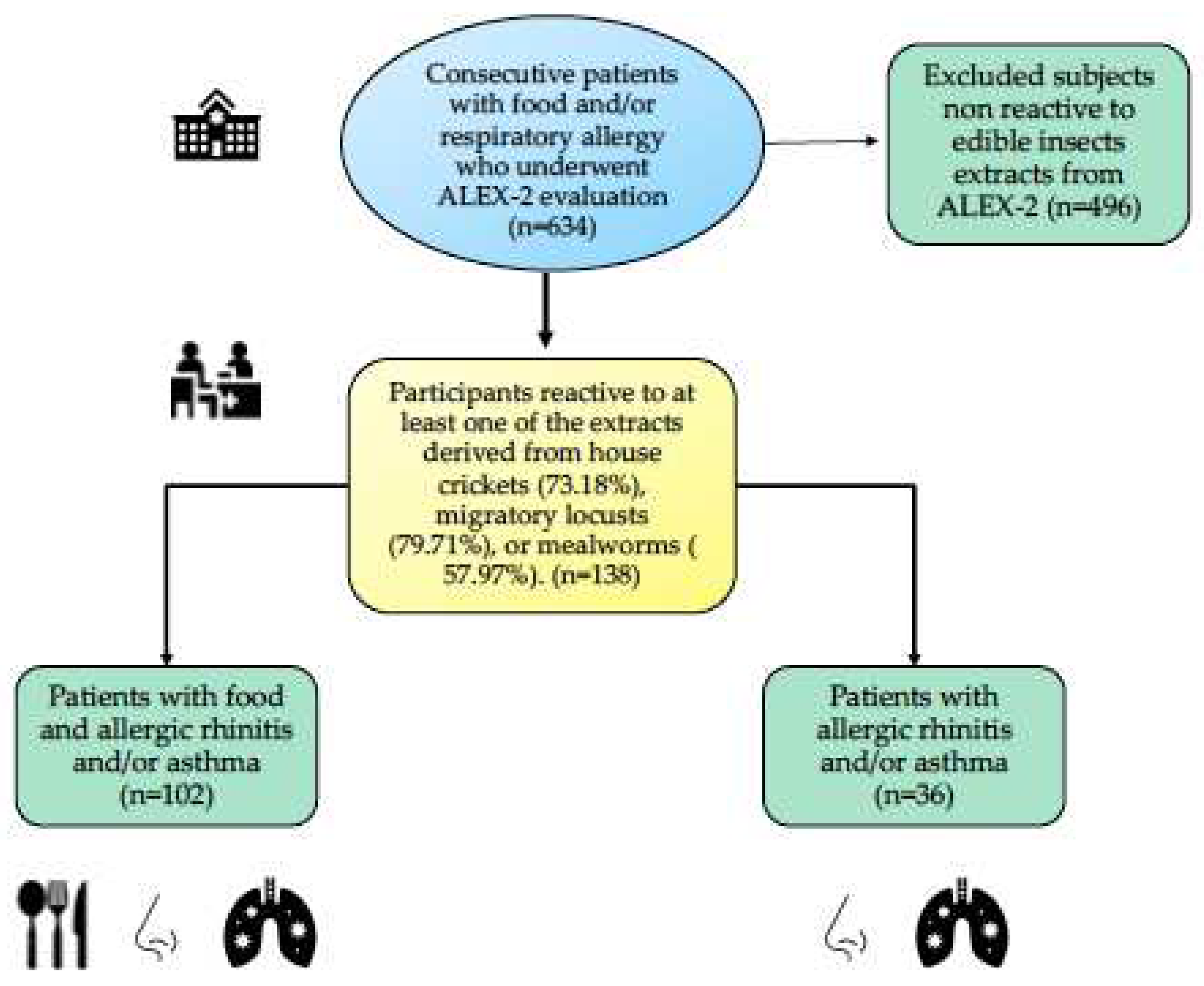

From March to September 2024, we conducted a proteomic analysis using the ALEX²

® MacroArray platform on 634 consecutive patients. Sensitization was identified in 138 individuals (21.76%) to at least one EI extract: Lm, Ad, and/or Tm. Among the sensitized individuals, the majority (102/138) had a clinical history suggestive of food allergy, either alone or in combination with a respiratory condition such as allergic rhinitis and/or asthma, while the remaining 36/138 presented exclusively with allergic rhinitis and/or allergic asthma. Notably, males were disproportionately affected (68.84%), with a median age of 18 years (range: 3–75 years) (

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

3.2. Specific IgE Profile in Pacients with a Sensitization to EI

Sensitization to at least one EI extract was identified in 138 individuals, with the following distribution: Lm in 110 individuals (79.71%), Ad in 101 (73.18%), and Tm in 80 (57.97%). Among the sensitized individuals, 65 (47.1%) exhibited concurrent sensitization to all three EI. Single-reactor cases were distributed as follows: Lm = 22 (15.94%), Ad = 19 (13.76%), and Tm = 8 (5.79%).

Tropomyosin emerged as the serodominant allergen (63.76%) in our cohort, followed by troponin-C (28.98%), AK (26.81%), and sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein (8.69%). Additionally, 6.52% of subjects were sensitized to myosin light chain (Pen m 3), while only one individual (0.72%) displayed IgE reactivity to Der p 11 paramyosin (

Table 2).

Interestingly, 32 out of 138 individuals (23.18%) sensitized to EI showed no IgE reactivity to any of the panallergens—TM, AK, paramyosin, troponin C, and myosin light chain—on the ALEX2® chip. Additionally, only 4 of the 138 subjects (2.89%) sensitized to EI in our study exhibited no reactivity to any of the molecules included in the microarray panel.

3.3. Multiplex IgE Reactivity Profiles in Patients with Sensitization to EI and Exclusively Affected by Respiratory Allergy

All 36 insect-reactive individuals (100%) diagnosed with allergic rhinitis and/or asthma, but not food allergies, were sensitized to at least one mite allergen. Eight allergens—Der f 2, Der p 23, Der p 2, Der p 1, Der f 1, Der p 5, Der p 7, and Blo t 21—were identified in over 50% of the cohort, making them serodominant. The majority of patients were cross-sensitized to group 2 mite allergens, specifically Der f 2 and Der p 2, with lesser cross-sensitization to Gly d 2, Tyr p 2, and Lep d 2. Sensitization to storage mite group 2 allergens was notably high, dominated by Gly d 2 (47.22%), followed by Tyr p 2 (41.66%) and Lep d 2 (36.11%). Remarkably, reactivity to panallergens was infrequent (5 out of 36 patients), with Der p 20 in 3 cases (8.33%), Der p 10 in 1 case (2.77%), and Blo t 10 in 1 case (2.77%). No cases of Der p 11 sensitization were observed (

Table 3).

3.4. Allergen-Specific IgE Levels to TMs, AKs, and Different EI Extracts Were Significantly Correlated

In the investigated cohort, only 6 out of 138 individuals (4.34%) sensitized to EI showed no reactivity to any of the 17 mite allergens tested, which included Der p 1, Der p 2, Der p 5, Der p 7, Der p 10, Der p 11, Der p 20, Der p 21, Der p 23, Der f 1, Der f 2, Blo t 5, Blo t 10, Blo t 21, Lep d 2, Gly d 2, and Tyr p 2. Among these 17 mite-derived molecules, significant (p < 0.05) correlations with sensitization to EI were found only for two allergen groups: AK with Der p 20 (r = 0.26) and TM with Blo t 10 (r = 0.78) and Der p 10 (r = 0.86).

4. Discussion

The increasing use of EI as a sustainable protein source has raised concerns about their allergenic potential [

23,

24]. Mite-EI syndrome exemplifies a complex interplay between insects, mites, and their environments, particularly in subtropical regions with high mite prevalence. This syndrome, a subset of the broader dust mite–crustacean–insect syndrome, underscores the significant cross-reactivity among these arthropods, often affecting individuals sensitized to mites who subsequently develop allergies to crustaceans and EI [

25,

26]. Understanding these immune mechanisms provides valuable insights into allergen cross-reactivity beyond single food sources. Lipid transfer protein (LTP) syndrome, a leading cause of plant-derived food allergies, provides a useful parallel [

27,

28]. LTPs, as stable pan-allergens found in various plant species, often initiate sensitization through inhalant exposure before progressing to food allergies. Similarly, we hypothesize that in mite-prevalent regions, inhalant exposure to either HDM or storage mites may serve as an initial trigger for EI sensitization, even in individuals without prior direct exposure. Former research has demonstrated that shrimp allergy can be strictly dependent on HDM sensitization, a pattern that may extend to EI allergy in certain geographic areas [

29,

30].

4.1. Molecular Sensitization Patterns in the Investigated Cohort

In our study, TM was the most prevalent allergen (63.76%), followed by troponin-C (28.98%), AK (26.81%), and sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein (8.69%) [

31,

32]. A smaller proportion (6.52%) were sensitized to myosin light chain (Pen m 3), and only one individual (0.72%) reacted to Der p 11 paramyosin. Notably, 23.18% of participants exhibited no IgE reactivity to the pan-allergens on the ALEX2

® chip. This contrasts with a Mediterranean cohort where 55.4% of insect-reactive individuals lacked pan-allergen sensitization, suggesting possible regional variations in sensitization profiles [

33]. Interestingly, a subset of four participants in our cohort displayed specific IgE to EI but no reactivity to other food or inhalant allergens, suggesting that EI may serve as a primary sensitizer in some individuals. These findings highlight the potential for EI to be an independent cause of allergic sensitization, rather than solely a result of cross-reactivity.

4.2. Cross-Reactivity Among EI and Other Allergens

Our study confirms clinically relevant cross-reactivity between EI and crustaceans, driven by pan-allergens such as TM, troponin-C, and AK. However, the relationship between mite and EI sensitization remains debated. Previous research suggested an inverse correlation between mite sensitization and IgE reactivity to EI, implying mites might not act as primary sensitizers [

33,

34]. Our findings challenge this assumption, showing that 95.66% of individuals sensitized to EI also reacted to at least one of the 17 investigated mite allergens, with significant correlations (p < 0.05) between EI sensitization and key molecular pan-allergens. In this regard, despite former research has shown that individuals with HDM allergies may experience allergic reactions after consuming EI, the clinical relevance of co-sensitization to mites and EI is still debated, with more studies required to understand the mechanisms of allergic responses. Despite epidemiological data on allergic reactions to EI among patients with mite allergies is scarce, in a recent study of 6,173 individuals, 4.3% showed sensitization to yellow mealworm, with a notable association between this sensitization and HDM allergies [

35]. In our cohort, among the 36 EI-reactive individuals diagnosed exclusively with allergic rhinitis and/or asthma (without food allergies), all were sensitized to at least one mite molecule. However, they exhibited infrequent reactivity to pan-allergens such as Der p 20 (8.33%), Der p 10 (2.77%), and Blo t 10 (2.77%). These findings suggest that while HDM exposure may contribute to EI sensitization, its exact role requires further investigation.

4.3. Insect-Specific Proteins and Sensitization Mechanisms

While cross-reactivity explains some EI sensitization cases, the presence of insect-specific proteins such as chemosensory proteins (CSP), odorant-binding proteins (OBP), and hexamerin suggests alternative sensitization pathways [

36,

37]. These proteins, largely absent in phylogenetically related organisms such as mites and crustaceans, may contribute independently to EI sensitization. The precise immunological mechanisms remain unclear and warrant further research.

4.4. Limitations

Diagnosing mite-EI syndrome is challenging due to overlapping allergens among mites, crustaceans, and EI [

38,

39]. Although component-resolved diagnostics could help distinguish primary sensitization from cross-reactivity, their limited availability restricts precise assessments. Moreover, treatment options for this syndrome remain limited, with management largely focused on avoidance and emergency preparedness in case of anaphylaxis [

40,

41,

42]. A major limitation of our study was the absence of clinical food challenges, which are crucial for assessing the clinical significance of insect-specific sensitization patterns. While food challenges have been used successfully in shrimp-allergic patients, particularly those co-sensitized to specific pan-allergens, similar investigations in mite-allergic populations are lacking [

43,

44,

45]. Furthermore, the sample size of our cohort limits the generalizability of our findings.

5. Future Perspective and Conclusions

Despite the growing recognition of the allergenic potential of edible insects, further research is urgently needed to clarify the clinical relevance of cross-reactivity between mites, crustaceans, and EI. Public health policies should prioritize addressing the risks of allergic reactions to edible insects, particularly among individuals with known mite or shellfish allergies [

46,

47]. Regulatory frameworks should continue to include allergen labeling, consumer education, and further research into strategies for reducing the allergenicity of edible insects.

This investigation highlights regional variations in molecular sensitization profiles among individuals reactive to EI. In subtropical regions, increased mite exposure appears to influence IgE responses to insect proteins, emphasizing the complex interplay between environmental factors and allergen cross-reactivity and suggesting that food sensitization is shaped by multiple determinants. Although the lack of specific food challenge data limits the clinical assessment of insect-specific sensitization in mite-allergic individuals, these findings indicate that EI sensitization should be recognized as a distinct immunological concern rather than an incidental phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RG-P, PP-G and IS-M; methodology, RG-P, and PP-G; software, MF-R, and MC-B; validation and formal analysis, PP-G, and IS-M; investigation, IS-M, MF-R, and MC-B; resources, RG-P, and IS-M; data curation, MF-R, and MC-B; writing—original draft preparation, RG-P; writing—review and editing, RG-P, PP-G and IS-M; project administration RG-P, PP-G and IS-M; funding acquisition RG-P, PP-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundación Canaria Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Canarias (FIISC), Servicio Canario de Salud, grant number OA17/042.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Institutional Ethics Committee CEIC Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain on 2023 October, 26 (reference number CHUC_2023_66) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Servicio Canario de Salud but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Servicio Canario de Salud.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-4, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) for assistance in refining the manuscript text. However, all interpretations, analyses, and conclusions are the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Tm |

Tenebrio molitor |

| EI |

Edible Insects |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| HDM |

House Dust Mites |

| TM |

Tropomyosin |

| Lm |

Locusta migratoria |

| Ad |

Acheta domesticus |

| AK |

Arginine Kinase |

References

- COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2025/89 of 20 January 2025. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202500089 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/edible-insects-science-novel-food-evaluations (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Francis, F.; Doyen, V.; Debaugnies, F.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Caparros, R.; Alabi, T. , et al. Limited cross reactivity among arginine kinase allergens from mealworm and cricket edible insects. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barre, A.; Pichereaux, C.; Simplicien, M.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Benoist, H.; Rougé, P. A Proteomic- and Bioinformatic-Based Identification of Specific Allergens from Edible Insects: Probes for Future Detection as Food Ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Gier, S.; Verhoeckx, K. Insect (food) allergy and allergens. Mol Immunol. 2018, 100, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamberti, C.; Nebbia, S.; Cirrincione, S.; Brussino, L.; Giorgis, V.; Romito, A.; Marchese, C.; Manfredi, M.; Marengo, E.; Giuffrida, M.G.; Rolla, G.; Cavallarin, L. Thermal processing of insect allergens and IgE cross-recognition in Italian patients allergic to shrimp, house dust mite and mealworm. Food Res Int. 2021, 148, 110567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K.Y.; Park, J.W. Insect Allergens on the Dining Table. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020, 21, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotnicka, M.; Karwowska, K.; Kłobukowski, F.; Borkowska, A.; Pieszko, M. Possibilities of the Development of Edible Insect-Based Foods in Europe. Foods 2021, 10, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barre, A.; Pichereaux, C.; Velazquez, E.; Maudouit, A.; Simplicien, M.; Garnier, L.; Bienvenu, F.; Bienvenu, J.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Auriol, C.; Benoist, H.; Rougé, P. Insights into the Allergenic Potential of the Edible Yellow Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor). Foods 2019, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Broekhoven, S.; Bastiaan-Net, S.; de Jong, N.W.; Wichers, H.J. Influence of processing and in vitro digestion on the allergic cross-reactivity of three mealworm species. Food Chem 2016, 196, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, W.N. Grasshopper sensitization in patients allergic to crustaceans, mites, and cockroaches: Should grasshopper-containing products carry a warning? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, A.; Shao, J.; Degreef, J.M.; van Leeuwen, A.; van Ree, R.; Pauli, G.; de Blay, F. Role of tropomyosin as a cross-reacting allergen in sensitization to cockroach in patients from Martinique (French Caribbean island) with a respiratory allergy to mite and a food allergy to crab and shrimp. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007, 39, 85–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, J.C.; Cunha, L.M.; Sousa-Pinto, B.; Fonseca, J. Allergic risks of consuming edible insects: A systematic review. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celebi Sozener, Z.; Ozdel Ozturk, B.; Cerci, P.; Turk, M.; Gorgulu Akin, B.; Akdis, M. , et al. Epithelial barrier hypothesis: Effect of the external exposome on the microbiome and epithelial barriers in allergic disease. Allergy 2022, 77, 1418–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caraballo, L.; Zakzuk, J.; Lee, B.W.; Acevedo, N.; Soh, J.Y.; Sánchez-Borges, M. , et al. Particularities of allergy in the Tropics. World Allergy Organ J. 2016, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muddaluru, V.; Valenta, R.; Vrtala, S.; Schlederer, T.; Hindley, J.; Hickey, P.; Larché, M.; Tonti, E. Comparison of house dust mite sensitization profiles in allergic adults from Canada, Europe, South Africa and USA. Allergy 2021, 76, 2177–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Pérez, R.; Galván-Calle, C.A.; Galán, T.; Poza-Guedes, P.; Sánchez-Machín, I.; Enrique-Calderón, O.M. , et al. Molecular Signatures of Aeroallergen Sensitization in Respiratory Allergy: A Comparative Study Across Climate-Matched Populations. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 26, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González-Pérez, R.; Poza-Guedes, P.; Pineda, F.; Galán, T.; Mederos-Luis, E.; Abel-Fernández, E. , et al. Molecular Mapping of Allergen Exposome among Different Atopic Phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SOIL-TRANSMITTED HELMINTHIASES. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44804/9789241503129_eng.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Bousquet, J.; Schünemann, H.J.; Togias, A.; Bachert, C.; Erhola, M.; Hellings, P.W. , et al. Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma Working Group. Next-generation Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines for allergic rhinitis based on Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) and real-world evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020, 145, 70–80.e3. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Bojcukova, J.; Vlas, T.; Forstenlechner, P.; Panzner, P. Comparison of two multiplex arrays in the diagnostics of allergy. Clin Transl Allergy 2019, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuse, E.R.; Tonnang, H.E.Z.; Yusuf, A.A.; Machekano, H.; Egonyu, J.P.; Kimathi, E. , et al. The global atlas of edible insects: analysis of diversity and commonality contributing to food systems and sustainability. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Tettey, E.; Yunusa, B.M.; Ngah, N.; Debrah, S.K.; Yang, X. , et al. Legal situation and consumer acceptance of insects being eaten as human food in different nations across the world-A comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2023, 22, 4786–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, W.N.; Wünschmann, S.; Agah, S. Grasshopper anaphylaxis in patients allergic to dust mite, cockroach, and crustaceans: Is tropomyosin the cause? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 119, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso, R.; Reese, G.; Leong-Kee, S.; Plante, M.; Lehrer, S.B. Molecular basis of arthropod cross-reactivity: IgE-binding cross-reactive epitopes of shrimp, house dust mite and cockroach tropomyosins. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002, 129, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, B.; Stoenchev, K.V.; Skypala, I.J. Anaphylaxis across Europe: are pollen food syndrome and lipid transfer protein allergy so far apart? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022, 22, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betancor, D.; Gomez-Lopez, A.; Villalobos-Vilda, C.; Nuñez-Borque, E.; Fernández-Bravo, S.; De Las Heras Gozalo, M.; Pastor-Vargas, C.; Esteban, V.; Cuesta-Herranz, J. LTP Allergy Follow-Up Study: Development of Allergy to New Plant Foods 10 Years Later. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lamara Mahammed, L.; Belaid, B.; Berkani, L.M.; Merah, F.; Rahali, S.Y.; Ait Kaci, A. , et al. Shrimp sensitization in house dust mite algerian allergic patients: A single center experience. World Allergy Organ J. 2022, 15, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farioli, L.; Losappio, L.M.; Giuffrida, M.G.; Pravettoni, V.; Micarelli, G.; Nichelatti, M. , et al.. Mite-Induced Asthma and IgE Levels to Shrimp, Mite, Tropomyosin, Arginine Kinase, and Der p 10 Are the Most Relevant Risk Factors for Challenge-Proven Shrimp Allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2017, 174, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangorsch, A.; Jamin, A.; Spiric, J.; Vieths, S.; Scheurer, S.; Mahler, V.; Hofmann, S.C. Allergic Reaction to a Commercially Available Insect Snack Caused by House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Tropomyosin. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marchi, L.; Wangorsch, A.; Zoccatelli, G. Allergens from Edible Insects: Cross-reactivity and Effects of Processing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scala, E.; Abeni, D.; Villella, V.; ViIlalta, D.; Cecchi, L.; Caprini, E.; et al. Investigating Novel Food Sensitization: A Real-Life Prevalence Study of Cricket, Locust, and Mealworm IgE-Reactivity in Naïve allergic Individuals. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.; Huang, C.H.; Lee, B.W. Shellfish and House Dust Mite Allergies: Is the Link Tropomyosin? Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016, 8, 101–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Emilia, M.; Magdalena, C.; Weronika, G.; Julia, W.; Danuta, K.; Jakub, S.; Bożena, C.; Krzysztof, K. IgE-based analysis of sensitization and cross-reactivity to yellow mealworm and edible insect allergens before their widespread dietary introduction. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Linacero, R.; Cuadrado, C. New Research in Food Allergen Detection. Foods. 2022, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pali-Schöll, I.; Meinlschmidt, P.; Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Purschke, B.; Hofstetter, G.; Rodríguez-Monroy, F.A. , et al. Edible insects: Cross-recognition of IgE from crustacean- and house dust mite allergic patients, and reduction of allergenicity by food processing. World Allergy Organ J. 2019, 12, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Popescu, F.D. Cross-reactivity between aeroallergens and food allergens. World J Methodol. 2015, 5, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shroba, J.; Rath, N.; Barnes, C. Possible Role of Environmental Factors in the Development of Food Allergies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019, 57, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluco, S.; Losasso, C.; Maggioletti, M.; Alonzi, C.C.; Paoletti, M.G.; Ricci, A. Edible Insects in a Food Safety and Nutritional Perspective: A Critical Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2013, 12, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. The Potential of Edible Insects as a Safe, Palatable, and Sustainable Food Source in the European Union. Foods 2024, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Lan, F. The effect of immunotherapy on cross-reactivity between house dust mite and other allergens in house dust mite -sensitized patients with allergic rhinitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021, 17, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeckx, K.C.; van Broekhoven, S.; den Hartog-Jager, C.F.; Gaspari, M.; de Jong, G.A.; Wichers, H.J.; van Hoffen, E.; Houben, G.F.; Knulst, A.C. House dust mite (Der p 10) and crustacean allergic patients may react to food containing Yellow mealworm proteins. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014, 65, 364–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekman, H.C.H.P.; Knulst, A.C.; de Jong, G.; Gaspari, M.; den Hartog Jager, C.F.; Houben, G.F. , et al. Is mealworm or shrimp allergy indicative for food allergy to insects? Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałęcki, R.; Bakuła, T.; Gołaszewski, J. Foodborne Diseases in the Edible Insect Industry in Europe-New Challenges and Old Problems. Foods 2023, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abro, Z.; Sibhatu, K.T.; Fetene, G.M.; Alemu, M.H.; Tanga, C.M.; Sevgan, S.; Kassie, M. Global review of consumer preferences and willingness to pay for edible insects and derived products. Glob Food Sec. 2025, 44, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quintieri, L.; Nitride, C.; De Angelis, E.; Lamonaca, A.; Pilolli, R.; Russo, F.; Monaci, L. Alternative Protein Sources and Novel Foods: Benefits, Food Applications and Safety Issues. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).