1. Introduction

Potato (

Solanum tuberosum L.) is an herbaceous plant belonging to the

Solanaceae family and is considered one of the world’s most important food crops. It serves as a mayor staple food that plays a substantial role in feeding the world's growing population [

1]. It is currently cultivated in more than 100 countries on an estimated 16.8 million hectares of farmland, and 383 million tonnes of potatoes were produced globally in 2023 (The Food and Agriculture Organization’s database, updated in late December 2024). Argentina produces approximately 2.8 million tonnes allocating approximately 75-80 thousand hectares. Potatoes are the most widely consumed vegetable in the country, and their consumption has shown a positive trend over the years [

2].The main variety of potato grown and marketed in Argentina for fresh consumption is Spunta, while Kennebec variety is important in terms of industrial production, as it contains between 18 and 19% dry matter and is suitable for making sticks and puree [

2]. Spunta and Kennebec potato varieties differ in their yield; Kennebec generally showing higher overall yield and better performance under stress conditions, whereas Spunta is more responsive to external factors like biostimulants which can increase tuber number [

3].

Virus infections are a major threat to potato production since they can significantly decrease not only yield but also tuber quality. To date, approximately 50 viruses and one viroid have been reported to naturally infect

S. tuberosum [

4]. Among them,

Potato virus Y (PVY, genus

Potyvirus, family

Potyviridae) and

Potato leafroll virus (PLRV, genus

Polerovirus, family

Solemoviridae), are the most important and damaging potato viruses in the world [

4]. Both are transmitted by aphids (in a non-persistent or persistent manner, respectively) and are prevalent in most potato-growing areas in the world [

5,

6,

7]. PVY reduced total yield and marketable yield by 49% and 65%, respectively [

8]. Similarly, PLRV-infected seed tubers were reported to result in losses of total yield by 60% and marketable tuber yield by 88% [

8]. Of note, studies from China, the world’s largest potato producing country, showed that co-infection of PVY and PLRV caused much greater yield loss than single PVY or PLRV infections [

7]. Moreover, there are reports of mixed PVY and PLRV infections in potatoes worldwide [

9]. Both viruses coexist stably in nature, causing additive or synergistic effects on crop growth and productivity, thereby highlighting the importance of using virus-free seed potatoes or resistant varieties to reduce the impact of such infections [

10].

Natural complete resistance to PVY and PLRV has not been incorporated to date in actual commercial potato cultivars [

6,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Despite the paucity of sources of complete resistance [

15], potato breeders have introduced different types and sources of resistance to PVY and PLRV, originally identified in wild

Solanum germplasm, into some potato cultivars [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Nevertheless, introgression is a laborious process and to date many commercial cultivars remain susceptible. Consequently, at present, potato producers mostly manage diseases caused by PVY and PLRV using certified seeds whose main constraint is the high cost, and/or by insecticide applications with the entailing economic and environmental concerns [

21,

22,

23]. Genetic engineering of potatoes to confer virus resistance offers a more sustainable approach with reduced environmental impact. It also overcomes key challenges in conventional breeding, such as the complexity of tetraploid potato genetics and the need for large populations, whilst shortening times and maintaining the elite cultivar genetic background except for the introduced trait [

19,

24].

Capsid protein (CP)-mediated resistance was one of the first transgenic approaches shown to confer virus resistance (or tolerance) in plants [

25]. High levels of resistance have been reported in transgenic plants expressing the CP of several RNA viruses, including Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), Potato virus X (PVX), Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), and Tobacco rattle virus (TRV), suggesting that CP-mediated resistance may function by interfering with viral disassembly during infection [

26]. Heterologous protection against several strains of PVY as well as other potyviruses can be reached through the expression of the CP of the lettuce mosaic virus (LMV) (CPLMV) in transgenic tobacco plants [

27]. Although this protection was associated with detectable levels of CPLMV accumulation, there was no clear correlation between the level of the protein expression and the degree of protection [

28]. Furthermore, Hassairi et al. [

29] reported similar results in greenhouse evaluations of two potato cultivars transformed with CPLMV coding sequence. Another strategy for achieving viral resistance involves the RNA silencing mechanism. We have previously developed transgenic lines of the potato cultivar Kennebec expressing ORF2 of an Argentinian PLRV isolate (hereinafter referred to as RepPLRV). These lines exhibited resistance to different PLRV isolates, as confirmed by both grafting assays and field trials. Furthermore, the protection mechanism was suggested to be mediated by RNA silencing [

30]. In addition to the detrimental additive effects on crop growth and productivity of mixed infections, the simultaneous presence of multiple viruses poses a significant challenge to the efficacy of RNA silencing as a strategy for viral resistance [

31]. This is because certain viruses encode potent viral suppressors of RNA silencing that compromise the efficiency of this mechanism. Indeed, PVY encodes the Hc-Pro protein, a well-known and strong viral suppressor of RNA. Thus, under natural field conditions, in cases of a mixed infection, PVY could potentially overcome or interfere with the engineered resistance against PLRV [

30,

32].

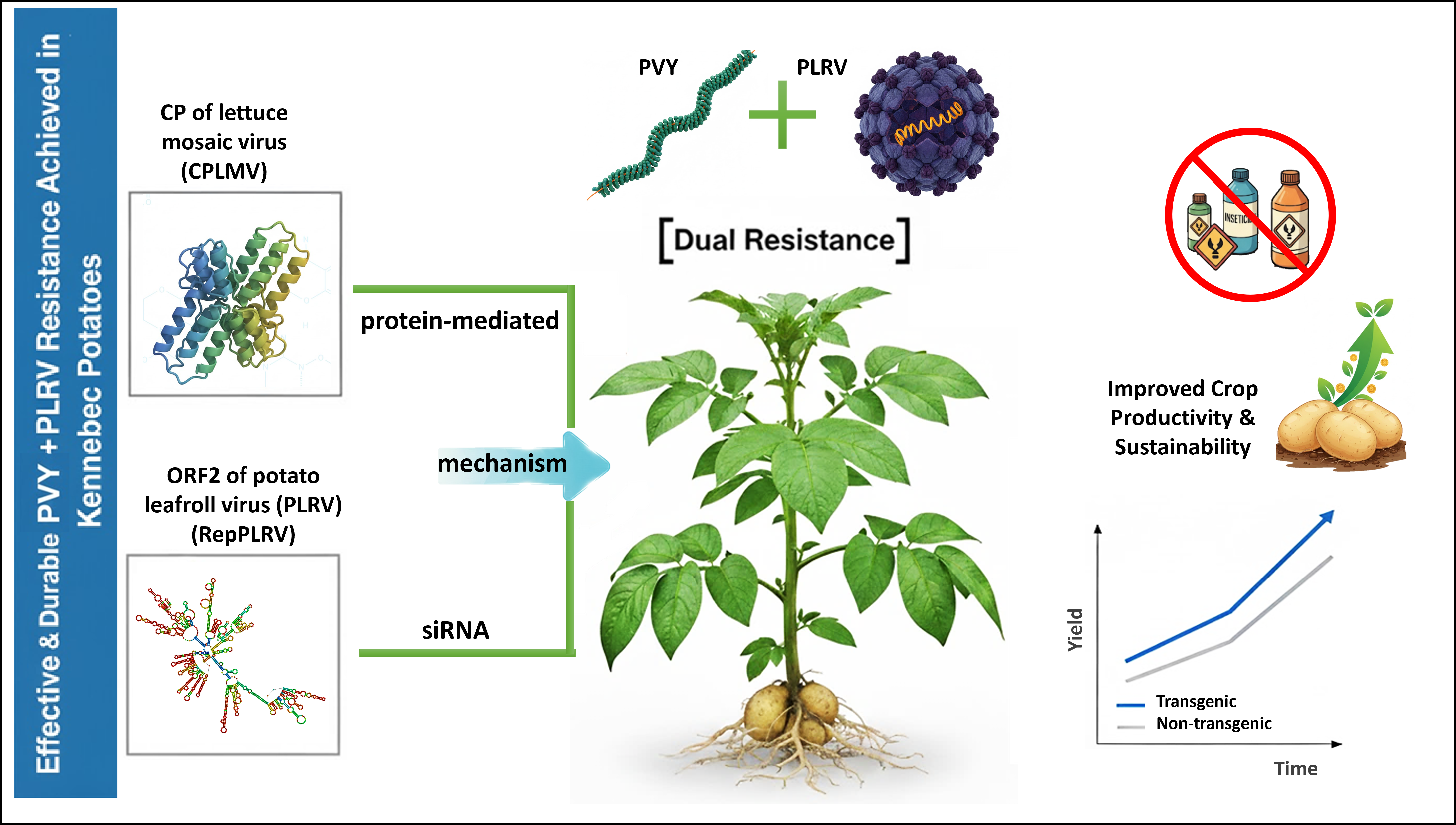

In this context, and with the aim of obtaining transgenic plants simultaneously resistant to PVY and PLRV, our group developed transgenic cv. Kennebec plants expressing the coding sequence for the CPLMV protein as well as the RepPLRV. These transgenic cv. Kennebec potato lines were molecularly and phenotypically characterized, and their resistance to infections caused by both viruses was evaluated. This study represents a significant achievement, demonstrating the successful development of commercially valuable potatoes lines resistant to both PVY and PLRV, while preserving the agronomic performance of the original cultivar under both greenhouse and field conditions.

2. Results

2.1. Generation of Transgenic Plants Engineered to Express the Coat Protein of Lettuce Mosaic Virus and the ORF2 Sequence of Potato Leafroll Virus

With the aim of obtaining transgenic potato plants simultaneously resistant to PVY and PLRV, we developed a unique construct containing cassettes that enable the expression of the coat protein gene of the lettuce mosaic virus (CPLMV) and the ORF2 of potato leafroll virus (RepPLRV), along with a cassette for the expression of the gene

nptII, (pPZP-Kan-CPLMV-RepPLRV binary vector,

Figure 1a), based on PZP200 vector backbone [

33]. Using the

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-based method, we successfully generated 27 transgenic lines cv. Kennebec, hereafter referred to as RY, carrying both CPLMV and RepPLRV transgenes. Two promising RY lines, designated as RY21 and RY25, were selected to conduct further analysis, based on their agronomic performance in the greenhouse and over two consecutive crop seasons (2005–2007) in Malargüe, Mendoza Province (Argentina) [

34]. In addition, the 2CA2 line, a PLRV resistant Kennebec transgenic line expressing only the RepPLRV, transformed with pVH-ATG-rep and described in Vazquez Rovere et al. [

30] was also included as control in the experiments. First, the integrity of the transgenes in the selected potato lines was assessed using PCR techniques. As shown in

Figure 1b, an approximate 1912-bp expected fragment corresponding to the complete RepPLRV was successfully amplified in RY21, RY25 and 2CA2 lines, while an approximate 925-bp fragment corresponding to the complete CPLMV was detected exclusively in the two RY candidate lines. As expected, no amplification was observed in non-transgenic control plants (NT).

Next, reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed to verify the transcription of RepPLRV and CPLMV. As shown in

Figure 1c, a ~1912-bp fragment corresponding to RepPLRV was amplified from the cDNA of RY and 2CA2 transgenic lines, while a ~925-bp CPLMV fragment was detected exclusively in the cDNA of RY lines. As expected, no transgene amplification was observed in NT control plants, whereas the housekeeping control transcript was properly detected in all samples. Since actin gene contains an intron in its sequence, the presence of only a single product corresponding to the spliced messenger confirmed the absence of genomic DNA contamination in the synthesized cDNA samples (

Figure 1c).

2.2. Assessment of Key Molecules Involved in the Resistance Mechanism of RY Transgenic Lines

Since the presence of the CPLMV protein has been shown to be essential for PVY protection in transgenic lines [

27] its expression was evaluated in total protein extracts from both RY lines using commercial polyclonal antibodies against the LMV capsid protein. As shown in

Figure 2a, the CPLMV protein was clearly detected in the RY21 and RY25 samples, as indicated by strong bands at the expected molecular weight (~31 kDa) (

Figure 2a, top panel). Additionally, a band of approximately 35 kDa was observed, likely due to post-translational modification of the CPLMV protein. As expected, no CPLMV signal was observed in NT Kennebec and 2CA2 samples.

Subsequently, since RepPLRV has been suggested as a target of post-transcriptional gene silencing [

30], we performed small RNA sequencing to identify specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) associated with RepPLRV silencing. As shown in

Figure 2b, next-generation sequencing (NGS) revealed numerous 21- to 24-bp siRNA distributed heterogeneously along the RepPLRV sequence in RY21 and, to a lesser extent, in RY25. Although the number of reads mapping to RepPLRV was higher for RY21 than for RY25 (3000 vs 130), both lines exhibited the peaks of siRNA in the same regions. Notably, duplex structures were modeled in areas with the highest reads density, corresponding to regions of strong secondary structure within the RepPLRV RNA. As expected, only two reads from the wild-type Kennebec plant mapped on RepPLRV sequence (

Figure 2b), whereas no relevant results were identified for CPLMV (data not shown).

2.3. Assessment of PVY Viral Resistance of Transgenic Potato Lines Under Greenhouse Conditions

To assess the resistance of the selected RY transgenic plants under high PVY infection pressure, a mechanical inoculation trial was performed on potato plants using recombinant PVY

NTN and necrotrophic PVY

N strains collected and previously characterized from field samples in Mendoza [

34]. Inoculation conditions were optimized to achieve an infection rate of approximately 100% in NT plants. To evaluate the resistance of transgenic RY21 and RY25 lines to PVY infection, virus accumulation was measured in systemic leaf samples three weeks post-inoculation using an ELISA assay (

Figure 3). As expected, NT and 2CA2 infected plants exhibited significantly higher OD values, indicating substantial PVY accumulation. In contrast, RY21 and RY25 infected plants displayed significantly lower OD values, comparable to their respective non-infected controls, suggesting effective suppression of viral accumulation. Statistical analysis confirmed these differences, with highly significant reductions in OD values observed in RY21 and RY25 compared to NT (**p < 0.001). This evaluation assay was conducted three times, yielding consistent results. These results indicate that the RY21 and RY25 transgenic lines exhibit strong resistance to PVY, even under conditions of high infection pressure induced by mechanical inoculation.

2.4. Evaluation of the Growth Parameters of Transgenic Potato Lines Under Greenhouse Conditions

Tuber production was evaluated in transgenic lines RY21 and RY25, as well as in NT and 2CA2 control plants under conditions free of pathogen. The average number of tubers per plant is presented in

Figure 4a. No statistically significant differences in tuber numbers were observed among RY21 and RY25 lines compared to the controls. Tuber fresh weight per plant was also measured as an indicator of total yield (

Figure 4b), and no statistically significant differences in average fresh weight were observed among the transgenic lines and the NT or 2CA2 controls.

Throughout the greenhouse trials, the RY transgenic lines were phenotypically indistinguishable from the NT control cultivar Kennebec in terms of overall plant morphology, including plant size, leaf shape and coloration. Post-harvest evaluation of tuber characteristics further revealed no observable differences between transgenic and NT lines with respect to tuber shape, size, flesh color, or skin texture (data not shown).

These findings indicate that expression of the RepPLRV and CPLMV transgenes in RY21 and RY25 does not affect tuber number, yield, or overall plant and tuber morphology under the tested greenhouse conditions. In sum, the transgenic lines exhibited growth and developmental parameters comparable to the non-transformed commercial cultivar from which they were derived.

2.5. Assessment of Tuber Yield Under Field Conditions

To assess the agronomic performance of selected transgenic lines under optimal, virus-free conditions and to compare them with both the parental cultivar Kennebec and the widely grown commercial variety Spunta, field trials were first conducted during the 2016 growing season in Malargüe, Mendoza Province, Argentina, an officially declared virus-free zone. Tubers harvested from greenhouse plants were used. In this field trial, the mean tuber weight per plant was calculated based on the number of plants grown for each line and compared with those of the commercial cultivars Kennebec and Spunta (

Figure 5a). The cultivar Spunta exhibited the highest mean tuber fresh weight, averaging 0.23 kg per plant. NT control plants showed lower average tuber fresh weight of 0.11 kg. Notably, transgenic lines 2CA2, RY21, and RY25, with average tuber fresh weight of 0.23, 0.21 and 0.13 kg per plant, respectively, showed no significant differences in mean tuber weight compared to either commercial cultivar (NT Kennebec and Spunta) (

Figure 5a). In addition, the general phenotypic appearance of the plants was assessed, revealing no noticeable phenotypic differences between the RY transgenic lines and NT controls (

Figure 5b).

Moreover, three additional consecutive planting campaigns were carried out in a field in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, between 2022 and 2024. Tuber yield was evaluated across these field trials, and the average tuber weight produced by the transgenic lines did not differ significantly from that of the NT or Spunta controls (

Figure 6a). Post-harvest evaluation of tuber characteristics revealed no noticeable differences between transgenic and non-transgenic lines with respect to skin shape, size, or texture (

Figure 6b).

The results obtained under natural field conditions in two distinct regions, Mendoza and Buenos Aires Province, separated by 1080 km, demonstrate that the transgenic lines RY21 and RY25 exhibit agronomic performance comparable to that of the non-transformed Kennebec cultivar from which they were derived. These findings indicate that the RepPLRV and CPLMV transgenes do not affect plant productivity.

2.6. Assessment of Viral Resistance of Transgenic Potato Lines in a Virus-Endemic Zone

Viral resistance evaluations under natural field exposure were performed in two field trials (2016 and 2017 growing seasons) in Tupungato, Mendoza Province, which is a potato production region in which PVY and PLRV infection rates are normally high. A complete randomized block design with three replicates was implemented in the field to evaluate virus infection in RY21 and RY25 transgenic plants, along with control plants (NT and 2CA2). 24 m2 were planted for each of the transgenic lines or with NT cv. Kennebec tubers. Progeny tubers harvested from these plants were subsequently sprout-tested for PLRV and PVY infections.

During the first growing season, tubers obtained from the greenhouse were planted. Since climatic conditions were highly unfavorable tuber production was limited, and most plants generated only a single tuber. A total of 92 tubers produced sprouted plants suitable for serological testing. Initially, ELISA assays were performed, followed by RT-PCR analysis on the same plants. The RT-PCR results corroborated the ELISA findings and, due to its higher sensitivity, was able to detect a greater number of positive plants. In summary, all PVY-positive samples were also found to be infected with PLRV, indicating frequent co-infection. Notably, RT-PCR did not detect any specific amplification products for PVY or PLRV in plants that tested negative for both viruses by ELISA. As shown in

Table 1 and Table 5 out of 21 tubers in the NT group tested positive for both PVY and PLRV (23.8%). Similarly, line 2CA2 showed dual infection in 4 out of 18 tubers (22.2%), with no statistically significant difference compared to the NT group. In contrast, no infection with either of the evaluated virus was detected in lines RY21 (0/31) or RY25 (0/22). These differences were statistically significant, indicating that both transgenic lines exhibited complete resistance to PVY and PLRV under field conditions. The overall field infection rates for PVY and PLRV during the 2016 season were approximately 23%, confirming that virus pressure was sufficiently high to reliably assess resistance performance.

During the second trial conducted in Tupungato, tubers obtained during the 2016 season in Malargüe were planted. During the growing season of 2017, weather conditions were considerably more favorable than in the previous year. As a result, all 283 independent plants successfully produced a total of 848 tubers, each of which was evaluated serologically. Remarkably, neither the non-transformed control (NT) nor any of the transgenic lines tested positive for PLRV, indicating that no PLRV infection was detected under field conditions this season. As shown in

Table 2, the incidence of PVY infection was 22.5% in NT controls and 31.5% in the 2CA2 line; this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.2143, Fisher’s Exact Test). In sharp contrast to the susceptible plants, all plants from RY lines (RY21 and RY25) remained completely free of PVY, representing a highly significant virus protection compared to NT controls (p = 0.0001 and p < 0.00001, respectively; Fisher’s Exact Test).

In conclusion, although average infection rates for PVY and PLRV during the 2016 season reached 23.81%, and PVY incidence among susceptible lines reached 31.5% in the 2017 season, the RY transgenic plants consistently demonstrated strong field resistance to both viruses. These results underscore the potential of RY21 and RY25 as valuable candidates for cultivation in virus-endemic regions.

3. Discussion

Potato production is significantly affected by viral diseases. More than 50 plant viruses have been reported to infect potatoes [

4], with Potato virus Y (PVY) and Potato leafroll virus (PLRV) being among the most economically damaging, causing substantial yield and quality losses worldwide [

4,

35,

36]. Plant pathologists and breeders have attempted to control viral diseases using various methods to ensure the production of virus-free seed potatoes. These methods include thermotherapy and tissue culture, specific breeding strategies for seed production and storage, seed potato certification programs and control of viral vectors using insecticides, biopesticides, and mineral oils. However, as these methods are often ineffective and expensive, the development and use of resistant crop cultivars is the most efficient strategy to mitigate the impact of virus diseases in agricultural settings, particularly in developing countries [

4,

37].

In previous work, we developed transgenic lines of the potato cultivar Kennebec that exhibited resistance to PLRV through the expression of the viral replicase gene (RepPLRV). These lines, including the 2CA2 line, were evaluated through graft inoculation and field trials [

30]. However, because multiple viruses frequently co-infect crops in field conditions, it is essential to engineer resistance to more than one virus simultaneously [

32,

38]. In the present work, to develop transgenic potato plants resistant to both PVY and PLRV, transgenic Kennebec plants expressing both the RepPLRV and the capsid protein gene of Lettuce mosaic virus (CPLMV), referred to as RY lines, were generated.

Firstly, molecular components potentially involved in the resistance mechanism of the transgenic lines were evaluated. Mapping of sRNAs showed a heterogeneous distribution across the RepPLRV sequence in the RY lines. The high abundance of 21- and 22-nt siRNAs is consistent with PTGS-mediated targeting of this region. On the other hand, given that CP-mediated resistance relies on a direct protein-mediated effect, we analyzed total protein extracts from the RY lines and confirmed high levels of LMV capsid protein expression, with no significant variation among the different transgenic lines. Dinant et al. [

27] and Hassairi et al. [

29] reported that the presence of CpLMV protein is essential for achieving PVY resistance in transgenic tobacco and potato plants, respectively. In line with these findings, the detection of CPLMV protein in our potato lines supports the hypothesis that the strong resistance to PVY observed in lines RY21 and RY25 is mediated by this protein. Moreover, small RNA sequencing analysis revealed a very low number of sRNAs derived from the CPLMV coding sequence (fewer than 30 reads). This suggests that the observed resistance is unlikely to involve RNA silencing mechanisms directed against the viral coat protein RNA. Mechanical inoculation of potato plants with PVY can lead to systemic infection; however, PLRV requires transmission by aphids or grafting to establish systemic infection. Therefore, under controlled greenhouse conditions, we could only evaluate resistance through direct inoculation with PVY. The transgenic lines RY21 and RY25 showed resistance under high infection pressure from mechanical inoculation, whereas control plants consistently exhibited high levels of PVY infection.

Assessment of tuber yield in the RY transgenic candidate lines under greenhouse conditions, performed over multiple years, demonstrates that expression of the RepPLRV and CPLMV transgenes does not affect plant productivity. Subsequent field trials confirmed that this conclusion could be extended to virus-free field conditions in Malargüe, Mendoza Province. Under field evaluations, the transgenic lines RY21 and RY25 also exhibited agronomic performance comparable to that of the non-transgenic Kennebec cultivar from which they were derived. No significant differences between the transgenic plants and the NT control plants in terms of growth, yield, and tuber shape were observed, indicating that RY lines retain the high levels of productivity and the characteristics of the original commercial cultivar. Moreover, these results were confirmed across three additional consecutive planting campaigns conducted in a field in Buenos Aires Province between 2022 and 2024.

The viral resistance of the transgenic potato lines was further evaluated under natural field exposure in a virus-endemic area. RY21 and RY25 lines, together with their non-transgenic Kennebec control, were cultivated in field trials to assess their resistance to PVY and PLRV, and to compare phenotypic and agronomic performance. These evaluations were conducted over two consecutive growing seasons in Tupungato. During the growing season of 2016, RY transgenic plants exhibited complete resistance to both PLRV and PVY under natural field conditions. In contrast, all susceptible (non-transgenic) plants that tested positive for one virus were also co-infected with the other, resulting in an overall infection rate of 23.81%. Interestingly, in all 2CA2 infected plants, the presence of PLRV and PVY was detected. Although the 2CA2 line was previously reported to be resistant to PLRV [

30], the occurrence of infection in this trial may indicate a breakdown of resistance, potentially triggered by co-infection with PVY- a phenomenon previously suggested by Vazquez Rovere et al. [

32]. These findings support the central hypothesis of this study: the coexistence of multiple viruses under natural conditions can compromise RNA silencing based resistance strategies. As expected, no tubers from the RY21 or RY25 transgenic lines tested positive for either PLRV or PVY.

During the second field trial in Tupungato (2017 growing season), weather conditions were considerably more favorable than in the previous year. PVY infection was detected in 31.5% of the susceptible control plants, whereas all RY transgenic lines remained completely free of PVY, demonstrating a highly significant level of resistance. Unfortunately, PLRV infection was entirely absent from the field. The field trials in Tupungato were conducted near commercial potato fields where insecticides are routinely applied, possibly at higher intensities during the 2017 season. Such treatments may have disrupted PLRV transmission by killing aphids before they could acquire or transmit the virus during the latent period. However, these insecticides are generally ineffective against PVY transmission, as they do not act quickly enough to prevent the rapid virus transfer by transient aphids [

39]. This situation could therefore explain why PVY, but not PLRV, was detected in susceptible lines during the 2017 field evaluation.

Kennebec potatoes are a popular and important potato variety due to their versatile culinary uses, fungal disease resistance, and high yield.

Final del formulario

Although numerous authors obtained immunity against PVY by transgenesis [

29,

40,

41,

42] to our knowledge, this is the first report describing the development of Kennebec transgenic lines highly resistant to PVY. Moreover, in this study, the 2016 field trial demonstrated that the transgenic lines RY21 and RY25 exhibited immunity to PLRV. Remarkably, this resistance was stably maintained after several years of

in vitro propagation and through at least three tuber generations. To date, PLRV immunity maintained across clonal generations of

S. tuberosum has only been reported by Orbegozo et al. [

18] who generated transgenic ‘Desiree’ plants expressing a hairpin construct derived from the PLRV coat protein gene. However, these plants were not evaluated in field conditions, where multiple viruses frequently co-infect crops, and this resistance strategy may be susceptible to breakdown, as indicated by our observations of the 2CA2 line in the present study.

It is worth noting that achieving durable resistance to PLRV under field conditions has historically been challenging. In 1988, Kaniewski and Thomas [

43] reported that CP-expressing Russet Burbank plants were the first to exhibit resistance to PLRV; however, the only line that remained uninfected in growth chamber assays became completely infected when exposed to natural field conditions [

44]. This highlights the importance of field evaluations to assess the stability of virus resistance and agronomic performance under natural conditions, which can differ substantially from greenhouse outcomes and are essential for pre-commercial biosafety assessments. Transgenic potato plants simultaneously resistant to PLRV and PVY have been previously obtained and different levels of tolerance to these viruses have been reported only in greenhouse conditions [

38,

45]. The lack of validation in the field raises questions about the actual performance of viral resistance under natural conditions where viral pressure, environmental variability, and vector dynamics differ substantially from controlled settings. In the present work, data obtained in the experimental field of Tupungato, a virus endemic-zone, showed that total resistance against PLRV and PVY were achieved in transgenic RY lines of

S. tuberosum cv. Kennebec. These findings demonstrate the durability and robustness of this biotechnological strategy, confirming its ability to provide dual viral resistance in real agricultural environments.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Construction of LMV-REP Plasmid

For the construction of the binary vector pZP-Kana-CPLMV-RepPLRV, the plasmid pBS-LMV (provided by INRA Versailles), containing the sequence coding for LMV capsid under the control of the Cauliflower Mosaic virus 35S (CaMV35S) promoter and the nopaline synthase gene terminator (Tnos), was modified by adding the CaMV 2x35S promoter and the rubisco gene terminator (2x35S-Trbs) cassette from the plasmid pKYLX. The complete PLRV-ORF2 sequence from the Argentinian PLRV isolate (PLRV-Ar) (referred to as RepPLRV, GenBank accession AF220151.1) was inserted into the XhoI restriction site of pBS-LMV- pKYLX vector between the 2X35S and the 2x35S-Trbs. The CPLMV-RepPLRV cassette obtained was released by restriction with the enzymes SpeI and NruI and subcloned into Xbal and HindIII sites of the pZP-Kan binary vector, which carries the nptII gene that allows the selection of plants in media supplemented with kanamycin. The final construct, named pZP-Kan-CPLMV-RepPLRV, was verified by restriction enzyme digestion and was transferred into

Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 (pAL4404) strain following the protocol of electroporation [

46].

4.2. Potato cv. Kennebec Transformation and Regeneration

Leaf discs of

Solanum tuberosum cv. Kennebec were co-cultured with the

A. tumefaciens LBA4404 pAL4404 carrying the pZP-Kan-CPLMV-RepPLRV construct, as previously described by Vazquez Rovere et al. [

30]. Transgenic RY plants, as well as 2CA2 line [

30] were maintained

in vitro by periodic micropropagation in growing chambers (CMP 3244; Conviron, Manitoba, Canada) at 18–22 °C, under an 8/16-h dark/light cycle. Plants were subsequently transferred to soil, in 8 litre pots, and grown under greenhouse conditions for evaluation of growth parameters: virus testing and/or tuber production. Tubers were harvested and kept in darkness at 4°C for up to 6 months before sown in field trials or used directly for the different analysis performed in this study.

4.3. Plant DNA and RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis and RT-PCR

Genomic DNA from kanamycin-resistant plants was extracted according to Dellaporta et al. [

47]. PCR was performed to confirm the presence of the RepPLRV, using primers 5’RepcATG (ATGGGATTACGGTCTGGAGA) and 3’Rep2 (TCAGTGTTCTTTTGTGGTGGCACTCGGA), and the CPLMV, using CP Up (ACTCTAGAGGATCCAAGCTTTATTTTTACAACAATTACCAACAACAAC) and CP low (TTAGTGCAACCCTCTCACGCCTAAGAGAGTATGCATATTCTGATTTACATC) primers. RNA from leaf tissue was isolated using the Trizol commercial extraction system (Invitrogen). For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of RNA was treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cDNA was synthesized using random primers and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNAs were amplified by PCR with specific primers: 5’RepcATG and 3’Rep2 for RepPLRV and CP Up and CP low for CPLMV. Amplification of RepPLRV genomic DNA or cDNA was performed under the following conditions: a denaturation step at 95°C for 1 min. followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. CPLMV from genomic DNA or cDNA was amplified as follows: a denaturation step at 95°C for 1 min. followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

4.4. Plant Total Protein Extraction and Western Blot

Potato leaf samples were ground in mortars with liquid nitrogen, until a fine powder was obtained. Total plant proteins were extracted using buffer 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 400 mM Sucrose, 100 mM TrisHCl pH 8, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-Mercaptoethanol and 2 mM PMSF) [

48], at a ratio of 300 ml per 100 mg of tissue. The mixture was incubated on ice for 10 to 30 min and centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 min at 12000 rpm. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and stored at -80 °C until use. Proteins were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE before blotting on Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). CPLMV protein was detected using an anti-CP rabbit monoclonal primary antibody (Bioreba), followed by an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Merck) and bands were visualized using NBT/BCIP reagents (Promega).

4.5. Detection of Viral RNA

Total RNA was extracted from potato leaf tissue as described above. PCR assays for PLRV RNA detection were performed with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) and specific primers: PLpP0up (ATGATTGTATTGACCCAGTC) and PLpP0low (TCATTCTTGTAATTCCTTTTGGAG) that amplify the complete ORF 0 sequence or PLF (ACDGAYTGYTCYGGTTTYGACTGG) and PLR (TCTGAWARASWCGGCCCGAASGTGA) that amplify the intergenic region of the virus. The reactions were carried out with a denaturation step at 94 ◦C for 4 min followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR assays for PVY RNA detection were performed as described above, using primers: Hc-Pro up (GCGGCAGAAACACTCGTCG) and HC-Pro low (CCTGGGCGCTTCGGCCCAAG). In all cases, amplified products were purified using a QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen), cloned into pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Life Technologies) and sequencing service was performed at National Institute of Agricultural Technology, Biotechnology Institute, Genomics Unit.

4.6. Small RNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from potato leaf tissue as described above with Trizol commercial extraction system (Invitrogen). The Qiagen QIAseq miRNA Library Prep Kit libraries were assembled using the High-Throughput Genomics Shared Resource at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah. They were sequenced using the SAR24-2022 assay on a NovaSeq 6000 PE75x50. Sequencing service was performed at National Institute of Agricultural Technology, Biotechnology Institute, Genomics Unit. Next, the plant siRNAs were mapped to RepPLRV and coverage and positional patterns were assessed via sRNA_Viewer for visualization of small-RNA alignment (

https://github.com/MikeAxtell/sRNA_Viewer).

4.7. Plant Inoculation and Assessment of Virus Resistance in Greenhouse

PVY infection trials were conducted under biosafety greenhouse conditions. Two-week old in vitro grown plants were transplanted in 5 L pots with soil and acclimatized for 2-3 weeks. The N used was variable for non-infected (NI) plants (4 NT and 8 for transgenic lines) and for infected (I) plants (10 NT and 16 for transgenic lines). NT and 2CA2 plants were used as controls.

Plants were mechanically inoculated scraping the epidermal leaf layer with Carborundum and applying a mixture of field PVY-infected potato foliar extract, collected in Tupungato (2007, 2008, 2016 and 2017). Inoculum were confirmed as PVY-positive by ELISA and RT-PCR (data not shown). Subsequently, leaves were washed with water to remove excess abrasive and inoculum. After a week, inoculation was repeated to ensure PVY infection.

Inoculated and uninoculated (used as healthy controls) plants were maintained under a 16h day length, and day/night temperatures of 24 ± 2 °C. Symptoms were monitored throughout the experiment, and PVY infection was assessed three weeks post-inoculation using a commercial DAS–ELISA test following to manufacturer’s instructions (Bioreba). Each test was performed twice. Uninoculated plants were used as healthy controls. Spectrophotometric readings at 405 nm were performed with Multiskan Spectrum equipment (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with air blanking, after different times of substrate reaction, until the highest values were about A405 =1.5-2.0 (between 0.5 and 2 h. of reaction). Twice the mean of the absorbance values of the healthy control was chosen to consider positive for PVY infection. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 8), with significance at p < 0.05.

4.8. Field Trials Evaluations

Candidate resistant transgenic plants were subjected to field trials to analyse agronomic performance and genetic stability of resistance to PLRV and PVY. For each field trial, prior to sowing, the soil was cleared, and the furrows were prepared. Virus-free tubers were stored at low temperature for at least 60 days after harvest. A complete randomized block design with three replicates was used to evaluate the transgenic lines and NT controls. Tubers were planted in rows 4 m long, spaced every 2 m, at a depth of 2 or 3 cm below the soil surface. 24 m2 were planted for each of the transgenic lines or with non-transgenic (NT cv. Kennebec or Spunta) tubers. Average fresh tuber weight obtained (in grams (g)) calculated from the mean value (total tubers weight divided by total number of plants/tubers) of each block. The plots were fenced to avoid vandalism and to prevent access of large animals. Comparative field trials to evaluate the agronomical performance of RY lines were carried out, during the growing seasons of 2005-2006 and 2015-2016, at Malargüe, Mendoza Province, which is a virus-free potato seed-production region of Argentina. Three additional consecutive planting campaigns were carried out in a field in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, between 2022 and 2024. Viral resistance evaluations under natural field exposure were performed in Tupungato, Mendoza Province (Argentina), which is a potato production region in which PVY and PLRV infection rates are normally high. These trials were carried out during two consecutive growing seasons (2015/2016 and 2016/2017). For all trials, the number of plants grown in the field was recorded for each replicate block. Both trials were harvested manually in the autumn, collecting tubers from individual plants separately to avoid mixing. Tubers harvested from each replicate block were bulked by line, then counted and weighed. Tubers were stored at 4ºC until their evaluation. Viral diagnosis was performed by ELISA tests by the Potato Seed Analysis Laboratory of INTA Balcarce. Harvested tubers were sprout-tested. For this test individual buds were excised from tubers and planted in a greenhouse. Emerged young plants were assessed for virus infection by recording symptoms and by ELISA at 2-4 weeks after emergence. In selected cases, results were validated using RT-PCR. Agronomic performance of transgenic lines was compared to that of NT Kennebec and Spunta controls. Biological containment of field trials, assay isolation and disposal of transgenic materials were performed as established by the guidelines of the National Commission on Agrobiotechnology (CONABIA, Argentina, S01:0053198/2005; S01:045507/07; S05:0058167/2014; Expte:2020-72180378).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used for ELISA test statistical analysis using Graphpad Prism 8 software (USA). Statistical significance was set at a value of p < 0.05. Agronomic performance was analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test implemented in InfoStat (

http://www.infostat.com.ar). Statistical significance was set at a value of p < 0.05. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparing each line against NT in the viral resistance evaluation, where “*” denotes p < 0.001.