1. Introduction

The cultivation of chili pepper (

Capsicum annuum L.) is fundamental to both the economy and food systems in Mexico. However, its production is constrained by viral infections such as the

Pepper huasteco yellow vein virus (PHYVV) and the

Pepper golden mosaic virus (PepGMV), both belonging to the genus Begomovirus of the family Geminiviridae [

1]. Plants infected with PHYVV typically exhibit symptoms including vein yellowing, yellow mosaic, leaf distortion, leaf curling, stunted growth, and yield reduction [

2]. In the case of PepGMV, the symptoms include golden mosaic, leaf deformation, and reduction in plant size [

3]. Its primary vector for both viruses is the whitefly (

Bemisia tabaci Genn.) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), which has a high transmission capacity and has developed resistance to insecticides, complicating efficient control [

4,

5].

In Mexico, PHYVV and PepGMV are widely distributed across

C. annuum production areas. Both viruses have been detected in domesticated cultivars and wild populations. Their presence has been reported in northern states such as Tamaulipas and Sinaloa, as well as in central and southern regions, including Puebla and the State of Mexico [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Specifically, PepGMV has been identified in regions like Baja California, Sonora, the Comarca Lagunera, San Luis Potosí, Michoacán, Campeche, Yucatán, Puebla, and the State of Mexico [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The use of resistant genotypes is the most effective strategy to reduce

Begomovirus incidence and minimize agrochemical use [

13]. Wild relatives of cultivated species are recognized as valuable sources of resistance genes for pests and diseases [

14]. Regarding wild plants, Hernández-Verdugo et al. [

15] and Godínez-Hernández et al. [

16] identified wild accessions of

C. annuum and

C. chinense with resistance to PHYVV. These species are important because they represent the genetic basis from which current commercial cultivars have been derived. For instance, transcriptomic analysis under biotic and abiotic stress in

C. chinense led to the identification of the

CchGLP gene in the BG-3821 accession, which encodes a germin-like protein associated with PHYVV resistance [

17,

18]. Furthermore, García-Neria and Rivera-Bustamante [

19] demonstrated that BG-3821 displays natural resistance to both PepGMV and PHYVV, involving defense mechanisms such as systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and restricted viral replication.

Additionally, a phenomenon of symptom remission or recovery has been reported in pepper plants experimentally infected with PepGMV dimers. This recovery is associated with a specific resistance mechanism involving the accumulation of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), suggesting the participation of post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) as an antiviral defense pathway. Unlike general resistance, this response was specific to PepGMV and not observed with PHYVV, supporting the hypothesis of highly selective defense mechanisms in certain pepper accessions [

20]. Despite these advances, no commercial pepper cultivars in Mexico have been confirmed to possess resistance to both PHYVV and PepGMV.

Traditionally, resistance screening has been performed through inoculation with

B. tabaci. While effective, this method requires high technical expertise, specialized infrastructure, and extended evaluation periods [

21,

22]. As an alternative, biolistic (gene gun) inoculation has proven effective for introducing viral DNA directly into plant tissues, particularly in

Capsicum species [

20,

21]. This approach circumvents the limitations associated with vector- or

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transmission, making it particularly useful for recalcitrant species [

22,

23].

In this study, it was proposed that pepper accessions with varying degrees of domestication would display differential resistance to PepGMV and PHYVV infection. Therefore, 15 Capsicum annuum accessions with different levels of domestication were inoculated separately with infectious PepGMV and PHYVV dimers by bioballistics, in order to identify sources of genetic resistance or tolerance to these viruses. The results revealed significant differences in symptom severity and disease progression among accessions and domestication levels, with wild and semidomesticated accessions generally exhibiting lower severity and Area Under the Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC), particularly in response to PHYVV. Additionally, viral DNA was detected in asymptomatic plants by PCR, indicating that some plants were able to restrict the replication or expression of these viruses. For instance, the wild accession Acc-106 showed resistance to PepGMV and tolerance to PHYVV. These findings contribute to the understanding of genetic resistance to Begomovirus in C. annuum.

2. Results

2.1. Evolution of the Symptoms of PepGMV and PHYVV

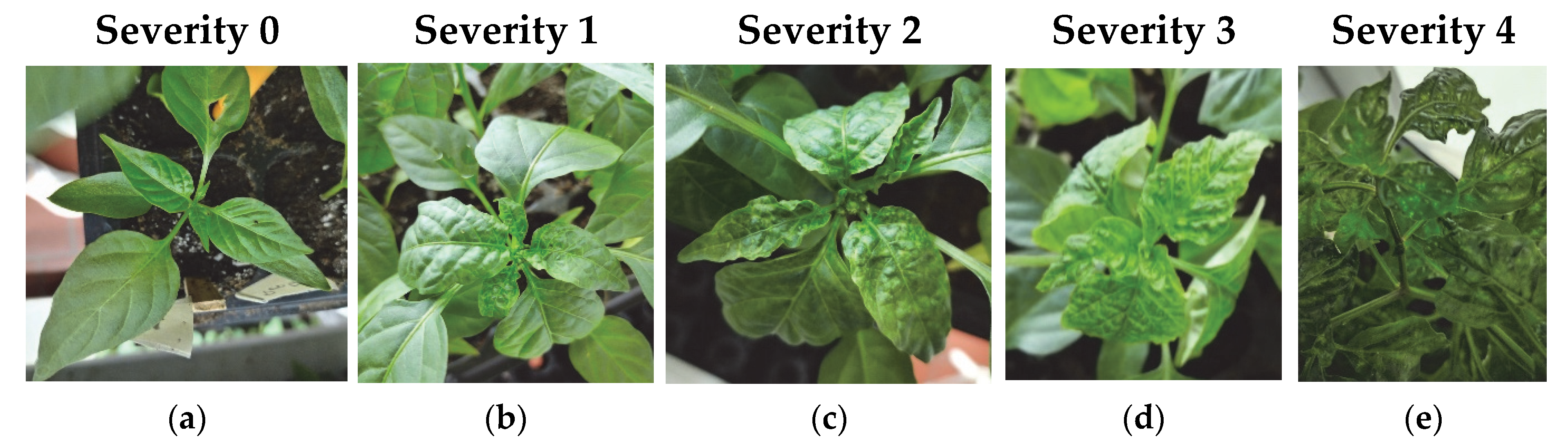

The control plants from the 15 accessions that were inoculated with tungsten particles lacking viral DNA did not exhibit any symptoms of viral infection. In contrast, plants inoculated with PepGMV and PHYVV developed characteristic symptoms, the progression of which was monitored at 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 days postinoculation (dpi) to establish a specific severity scale for each virus. Symptom evolution was documented photographically in representative plants that displayed typical symptoms at varying degrees of severity for PepGMV (

Figure 1) and PHYVV (

Figure 2). The images were classified and described according to the observed symptoms, following the severity scale presented in Table 5. Although both viruses generally induce similar symptoms in pepper plants, the descriptions accounted for the phenotypic particularities associated with each infection. The first symptoms induced by both viruses were observed starting at 7 dpi.

2.1.1. Development of PepGMV Symptoms

PepGMV resistant plants remained asymptomatic (severity = 0) throughout the 35 dpi duration of the experiment (

Figure 1a). Plants that developed initial symptoms of PepGMV exhibited small bumps or yellow spots at the base of the inoculated leaves (

Figure 1b). These bumps and spots expanded and became more pronounced, forming yellow mosaics on the leaf surface. The symptoms intensified and spread across the leaf, covering a larger area (

Figure 1c). Subsequently, infected leaves displayed deformations and chlorosis, with yellow mosaics distributed over the entire leaf surface. The leaves became curled and showed an irregular texture (

Figure 1d). In severe cases, the leaves were completely deformed, becoming elongated and wavy, with prominent yellow blotches (

Figure 1e).

2.1.2. Development of PHYVV Symptoms

As with PepGMV, PHYVV resistant plants remained asymptomatic throughout the 35 dpi evaluation period (

Figure 2a). Initial symptoms appeared as slight yellowing of the veins at the base of the leaves (

Figure 2b). In more advanced stages, the yellowed veins formed a reticulated pattern extending from the base to the middle of the leaf. These symptoms intensified and spread across the leaf, covering a larger area (

Figure 2c). In the most advanced stages, infected leaves exhibited severe deformation and chlorosis, with an intense yellow hue and a prominent network of veins affecting approximately 90% of the surface. The leaves showed a downward bend at the midsection and developed an irregular texture (

Figure 2d). In extreme cases, the leaves adopted a spoon-like shape, with yellow venation distributed across the entire surface. These symptoms represented the most severe expression of PHYVV infection (

Figure 2e).

2.2. Response of Pepper Accessions to PepGMV and PHYVV Inoculation

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each virus allowed us to evaluate the effect of accession, evaluation time (dpi), and their interaction on the severity of symptoms induced by PepGMV and PHYVV. For both viruses, highly significant differences were observed among accessions and across evaluation times (p < 0.001), indicating that both factors had a substantial influence on symptom expression. In contrast, the interaction between accession and time was not significant, suggesting that although the accessions differed in their overall severity levels, the temporal pattern of symptom development was consistent across accessions. In other words, the increase or stability of symptom severity over time followed a similar trend among all accessions, with none exhibiting atypical progression.

Notably, the effect of accession was more pronounced in response to PHYVV (f = 22.495) than to PepGMV (f = 9.493), indicating greater differentiation in accession response to PHYVV. Likewise, the progressive increase in symptom severity over time was more marked in PHYVV infected plants (f = 40.16), suggesting a more aggressive or persistent infection compared to PepGMV (f = 13.553).

2.3. Incidence and Severity of PepGMV and PHYVV Infection

Symptom assessment at 35 dpi revealed substantial variability in both incidence and severity among the 15

Capsicum annuum accessions inoculated with PepGMV and PHYVV (

Table 1). Overall, higher incidence and severity were observed in response to PHYVV compared to PepGMV.

For PepGMV, incidence ranged from 0% (Acc-106) to 67% (Acc-12 and Acc-113), with an overall average of 40% (

Table 1). The mean severity across all accessions was 0.65. The accession with the lowest severity was Acc-106 (0.0, Pico Paloma), while the highest was Acc-113 (1.33, Bola). Although the mean severity recorded for all 15 accessions in response to PepGMV did not exceed 1.4 on the 0–4 scale (

Table 2), the differences among some accessions were statistically significant.

In the case of PHYVV, incidence was generally higher, with a mean of 77%, ranging from 13% (Acc-106) to 100% (Acc-113) (Table 5). The overall mean severity was 1.10, with the lowest value again in Acc-106 (0.13, Pico Paloma), while the highest severity was observed in Acc-06 (2.30, Guajillo).

2.4. Influence of the Level of Domestication of Accessions on the Response to Viral Inoculation

The results of the factorial ANOVA by domestication group revealed a significant effect on symptom severity (PepGMV: f = 13.055, p < 0.001; PHYVV: f = 63.663, p < 0.001), indicating that the degree of domestication had a considerable influence on symptom expression. Specifically, wild and semidomesticated accessions exhibited lower severity levels compared to domesticated ones, suggesting greater tolerance or natural resistance in less domesticated groups. Time also had a significant effect on both virus treatments (PepGMV: f = 12.535, p < 0.001; PHYVV: f = 34.779, p < 0.001), confirming that symptom severity increased over time (dpi). In contrast, the interaction between domestication level and time was not significant (PepGMV: f = 0.226, p = 0.986; PHYVV: f = 1.051, p = 0.396), indicating that the temporal progression of symptoms was consistent within each domestication group. In other words, although symptom severity differed by domestication level, the pattern of increase or stability over time remained similar across groups.

Table 2 shows the mean severity, severity range (minimum and maximum values among accessions within each group) and percentage of incidence for domestication groups (wild, semidomesticated, and domesticated) of

C. annuum accessions. On average, domesticated accessions exhibited higher severity and incidence against both viruses, particularly PHYVV. In contrast, wild accessions recorded the lowest values for both parameters.

These results suggest that domestication may increase susceptibility to both viruses, with a more pronounced effect observed in the case of PHYVV. The difference in symptom severity between domesticated and wild accessions may be attributed to the domestication syndrome, which encompasses drastic or gradual changes in plant physiology, anatomy, and defense related traits. Additionally, resistance or susceptibility mechanisms may vary depending on the virus species and environmental conditions.

2.5. Area Under the Disease Progression Curve (AUDPC)

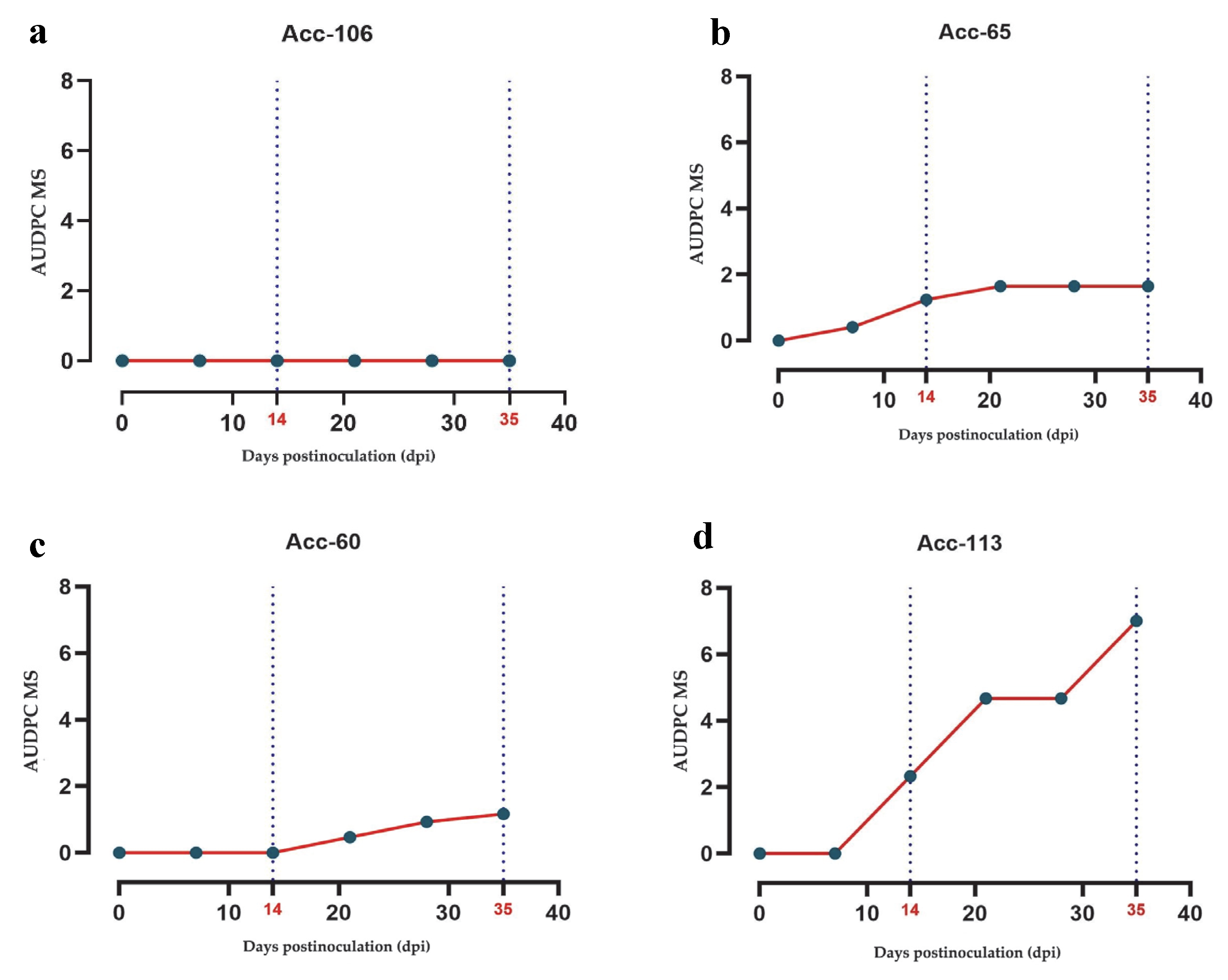

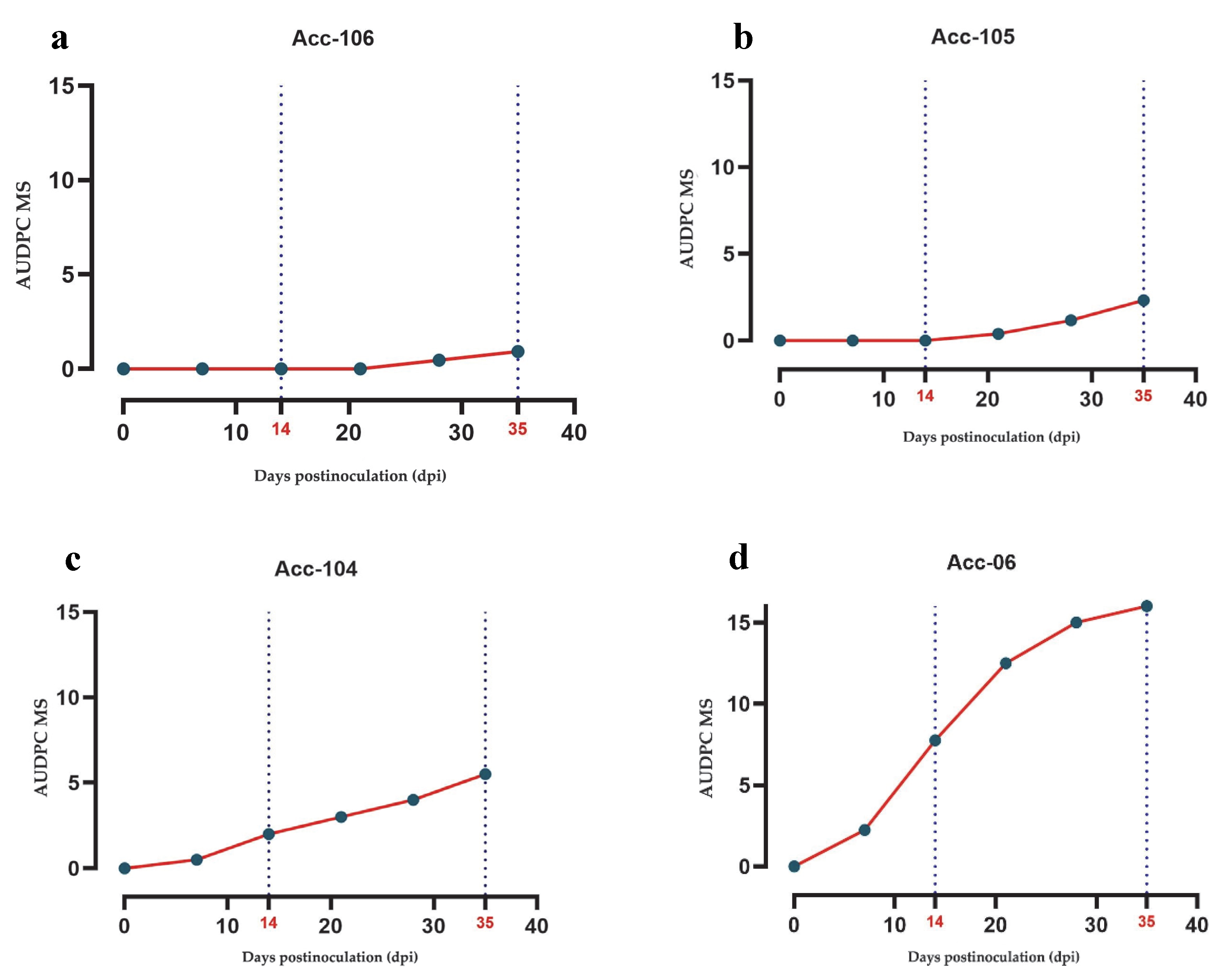

The results of the AUDPC, calculated from the mean severity and incidence for each of the 15 accessions inoculated with PepGMV and PHYVV during the 35 dpi period, as well as the classification of the accessions are presented in

Table 3. Based on these AUDPC values, the accessions were classified according to the categories described in Table 6, which defines the criteria for resistant (R), tolerant (T), moderately susceptible (MS), susceptible (S), and highly susceptible (HS).

The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis for AUDPC revealed significant differences among accessions for both viruses: PepGMV (χ² = 54.12, df = 14, p < 0.001) and PHYVV (χ² = 43.17, df = 14, p < 0.001).

Using these categories, phenotyping enabled the establishment of specific symptom progression profiles for each accession, facilitating their classification.

For PepGMV, most accessions were classified as tolerant, three as moderately susceptible (Acc-104, Acc-105, Acc-113), and one as resistant (Acc-106). In the case of PHYVV, the response was more heterogeneous: seven accessions were tolerant, seven moderately susceptible, and one susceptible (Acc-06).

Overall, accessions inoculated with PepGMV exhibited lower AUDPC values compared to those inoculated with PHYVV, suggesting that PHYVV induced greater severity in most of the evaluated accessions.

The disease induced by PepGMV showed wide variability in AUDPC progression. Accession Acc-106 (wild, Tabasco) was the only one classified as resistant (AUDPC = 0), exhibiting no symptoms (

Figure 3a Among the domesticated accessions, Acc-60 (Huacle, Oaxaca) and Acc-65 (Cascabel, Jalisco) displayed low AUDPC values (1.17 and 1.65, respectively), indicating a tolerant response (

Figure 3b,c). In contrast, Acc-113 (Bola), an improved variety, recorded the highest AUDPC value (7.00), reflecting greater susceptibility (

Figure 3d).

For PHYVV, increased disease progression and accumulation were observed in most accessions. Although Acc-106 (wild, Tabasco) maintained a low AUDPC value (0.93), other wild accessions such as Acc-105 and Acc-104 (both Amashito types) also showed low AUDPC values (2.33 and 5.50, respectively), being classified as tolerant and moderately susceptible (

Figure 4a–c). In contrast, the domesticated accession Acc-06 (Guajillo) exhibited the highest AUDPC value (16.00) and was therefore classified as susceptible (

Figure 4d).

2.6. Identification of PepGMV and PHYVV in Asymptomatic Plants by PCR

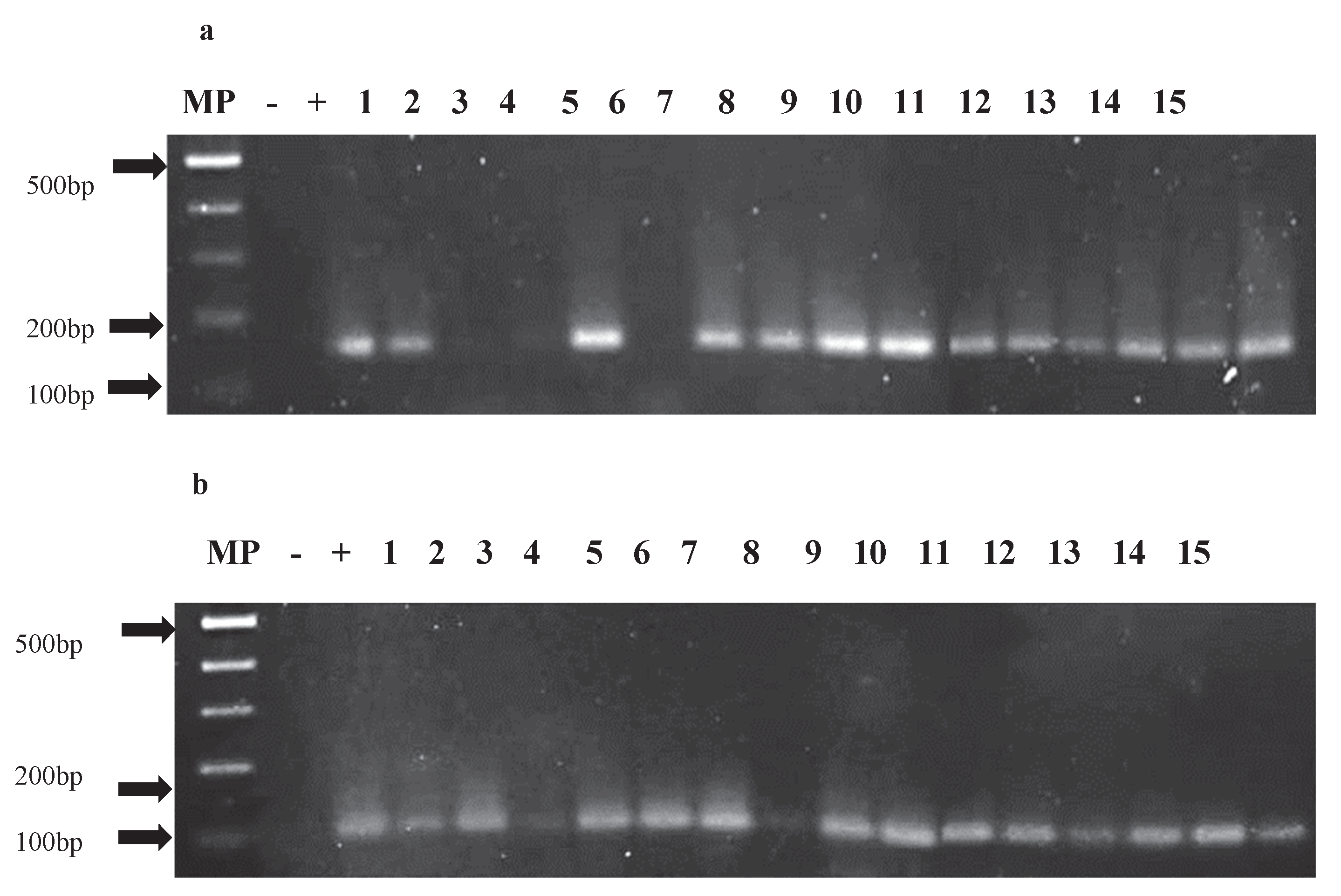

Out of the 167 asymptomatic plants, 154 were analyzed, yielding a 96% rate of positive detection. Specifically, 98% of the samples tested positive for PepGMV, while 91% were positive for PHYVV. PCR analysis targeting fragments of the replication (Rep) and capsid (CP) genes for both viruses confirmed the presence of viral DNA in some asymptomatic individuals.

Figure 5 illustrates the amplification of PepGMV genes in Accession Acc-106. In plants 2, 3, and 5, no amplification of the Rep gene was detected (

Figure 5a), while in plant 7, the CP gene was not amplified (

Figure 5b). Both genes play essential roles in the viral infection cycle Rep in replication and CP in “encapsidation”, and their lack of amplification may be associated with the activation of the plant’s defense mechanisms that interfere with viral gene expression.

3. Discussion

Several studies have highlighted the importance of wild

Capsicum populations as valuable genetic sources for pathogen resistance due to their high genetic diversity and adaptability [

15,

24,

25]. These populations, not subjected to artificial selection processes, exhibit a wide phenotypic and genotypic variability, including high levels of disease resistance [

25]. This genetic diversity present in these groups has been used to identify individuals with different degrees of resistance or tolerance, which can be useful in breeding programs aimed at managing viral diseases such as those caused by PepGMV and PHYVV [

26]. In this study, the use of bioballistic inoculation of infectious clones allowed a precise assessment of resistance across 15 wild, semidomesticated, and domesticated

Capsicum annuum accessions. Our findings revealed that wild and semidomesticated accessions consistently exhibited lower levels of symptom severity and incidence compared to domesticated ones. The wild accession Acc-106 did not develop any symptoms after PepGMV inoculation and showed a tolerant response to PHYVV, with a mean severity of 0.13 and an incidence of 13% at 35 dpi. In contrast, some domesticated accessions, such as Acc-06 and Acc-113, developed more severe symptoms, reflecting higher susceptibility to viral infection. These findings align with those of Godínez-Hernández et al. [

16] who evaluated 49 populations of wild habanero pepper (

Capsicum chinense) from Yucatán, Mexico, and reported significant resistance to PHYVV, attributed to low viral DNA accumulation and absence of visible symptoms in experimentally infected plants. Subsequently, Barrera-Pacheco et al. [

17] identified the

CchGLP gene in the wild accession BG-3821 of

C. chinense, associating it with resistance to PHYVV. More recently, Retes-Manjarrez

et al. [

27,

28] confirmed these findings by identifying wild populations of

C. annuum with a high level of resistance to PHYVV, in which the presence of the

CchGLP gene was also detected in the three lines evaluated.

Among the key mechanisms potentially underlying viral resistance is the restriction of viral movement within the plant [

19,

29,

30]. Although viral DNA quantification was not performed, the viral Rep and CP genes of PepGMV were detected in 98% of asymptomatic plants, and those of PHYVV in 91% of asymptomatic plants, suggesting that the virus was able to replicate but not to trigger visible symptoms. This observation aligns with previous studies indicating that begomovirus resistance may involve limited viral replication or activation of host defense responses that suppress viral DNA accumulation in infected tissues [

4,

16]. These resistance mechanisms have been further associated with transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing, DNA methylation, and inhibition of viral movement proteins within the host plant [

10,

19,

30,

38]. Although absolute viral DNA levels were not quantified in our study, the presence of the virus in asymptomatic plants suggests that certain accessions, particularly wild ones, may possess mechanisms that limit viral replication or spread to undetectable levels, which coincides with what has been reported in resistant accessions of

Capsicum in previous studies [

15,

16,

19,

31].

Our results show that symptom severity and incidence induced by PepGMV and PHYVV were significantly influenced by the degree of domestication, with wild accessions generally exhibiting lower symptom progression and lower AUDPC values. This trend is consistent with what was reported by Hernández-Verdugo et al. [

15], who found high levels of begomovirus resistance in wild

Capsicum annuum accessions, and with what was pointed out by Meyer and Purugganan [

25], who argue that domestication process may reduce the genetic variability associated with defense genes.

Regarding symptom development, both viruses (PepGMV and PHYVV) induced visible symptoms from 7 dpi, with more pronounced and persistent symptoms observed in PHYVV infected plants. Systematic photographic documentation, along with the development of a pictorial scale of severity, allowed for a detailed description of symptom evolution and the establishment of reliable visual categories. This five level scale (ranging from 0 to 4), not only complements previously published scales by Anaya-López [

31] for PepGMV and by Torres-Pacheco [

32] for PHYVV, but also provides a visual framework adapted for evaluating

Capsicum under controlled conditions.

The wide phenotypic variability observed among accessions in response to both viruses reflects the underlying genetic diversity and differing domestication levels of the evaluated materials. In this context, visual phenotyping, complemented with the calculation of the area under the disease progression curve (AUDPC), offered a robust tool to integrate the temporal dynamics of the disease progression. This phenotyping strategy, widely validated in plant pathology [

33,

34], enabled the detection of differentiated patterns in the progression of symptom severity and incidence. Accessions inoculated with PHYVV tended to develop higher AUDPC values than those inoculated with PepGMV, confirming a more aggressive infection by the former. Once again, accession Acc-106 stood out as the only one with zero or minimal AUDPC values, reinforcing its classification as resistant. Together, systematic visual characterization using a pictorial scale, combined with quantitative analysis through AUDPC, strengthens the selection process of resistant or tolerant genotypes and provides a solid methodological foundation for future breeding efforts and resistance evaluations against begomoviruses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

The pepper accessions evaluated correspond to genetic material stored in the Germplasm Bank of the Centro de Ciencias Agropecuarias de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes. We selected 15 accessions of

Capsicum annuum with high genetic diversity, originating from different regions of Mexico and exhibiting various degrees of domestication: wild, semidomesticated, domesticated or cultivated. This set includes

Criollo de Morelos 334 (CM334), an accession known for its resistance to

Phytophthora capsici (

Table 4).

4.2. Plant Production

The seeds of each accession were germinated following the procedure proposed by García-Nevárez et al. [

35] with some modifications. A pregermination treatment with 10% NaOH was applied for 4 minutes followed by four 1 minute rinses with distilled water. The seeds were then soaked in a solution of 5000 mg/L of gibberellic acid (Bio Gib

®) for 24 h at 25 °C. Afterward, the seeds of each accession were sown in 50 cavity trays previously prepared with Peat moss as a substrate. Following sowing, a fungicide suspension (3.0 mL per cavity of Intercaptan

® 2.0 g/L) was applied. The seedlings were watered, covered with black plastic, and incubated in darkness at room temperature until emerged. Once the seedlings emerged, the plastic was removed, and the trays were maintained under a photoperiod of 16 h light / 8 h darkness at a temperature of 28 ± 2 °C. developed 4 to 6 true leaves, virus inoculation was performed using bioballistics [

20].

4.3. Viral Clones and Inoculum Preparation

The viral clones of PepGMV and PHYVV used for inoculation were kindly donated by Dr. Rafael Rivera Bustamante, from the Laboratorio de Virología Vegetal of the CINVESTAV-IPN Irapuato. These correspond to infectious dimers of PepGMV and PHYVV, constructed and described by Carrillo-Tripp et al. [

20]. For particle preparation, 60 mg of 0.7 μm tungsten particles (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were used. The particles were washed with 2.0 mL of HNO₃, sonicated for 20 minutes with H₂O and ice in Corex glass tubes, and then transferred to 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. After centrifugation, the HNO₃ was decanted, and 1.0 mL of absolute ethanol was added. The mixture was sonicated and stirred for 1 minute, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Ethanol was discarded, and 1 mL of sterile distilled water was added. Then, 250 μL of the particle suspension was taken, and 700 μL of sterile distilled water were added. To coat the particles with viral DNA (infectious dimeric clones), the suspension was sonicated and 50 μL were transferred to a new 1 mL tube (sufficient for six bombardments). Then, 5 μL (1 μg/μL) of viral DNA, 50 μL of 2.5 M CaCl₂, and 20 μL of 0.1 M spermidine were added. The mixture was vortexed for 1 minute, sonicated, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet containing the DNA-coated particles was washed once with 500 μL of absolute ethanol, then sonicated and centrifuged again at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Finally, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 60 μL of ethanol for biolistic bombardment [

2].

4.4. Inoculation of Plants with PepGMV and PHYVV by Bioballistics

The infectious clones PepGMV and PHYVV were inoculated separately. The plants of each accession were arranged on individual trays, each corresponding to a specific accession. The number of plants per tray ranged from a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 45 plants, depending on seed availability and germination rate, which among accessions. Each tray was divided into three sections: one for inoculation with PepGMV, another for PHYVV, and a third section with five control plants that were bombarded only with particles lacking viral DNA. This design allowed the response of each accession to infection by both begomoviruses to be evaluated independently.

The particles previously coated with the PepGMV and PHYVV clones were applied using bioballistics device. Inoculation was performed on the first and second youngest leaves; each shot was directed at the center of the leaf blade, near the main vein. The tungsten microparticles were accelerated by helium pressure to 100 or 120 psi using an adapted delivery device [

2].

4.5. Evaluation of PepGMV and PHYVV Symptoms in Pepper Accessions

The inoculated plants were kept in a growth chamber with a photoperiod of 16:8 (light: dark) at an average temperature of 27±2 °C [

16]. Symptom severity caused by the viruses was evaluated qualitatively using the scales proposed by Anaya-López [

31] for PepGMV and by Torres-Pacheco [

32] for PHYVV, with some modifications (

Table 5). Weekly severity ratings were recorded for each plant and accession, starting at 7 days and continuing up to 35 days postinoculation (dpi). Disease progression was documented through photographs taken at 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 dpi to identify virus-induced symptoms and phenotypic traits, and to relate them to the severity scale.

Disease progression was assessed by calculating the Area Under the Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC), using mean severity values recorded at times 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 dpi. Based on these values and following the classification proposed by Reyes-Tena et al. [

36] with modifications, accessions were categorized into five groups: Resistant, Tolerant, Moderately Susceptible, Susceptible, and Highly Susceptible (

Table 6). This classification integrated the slope of the curve and the mean severity at 35 dpi for each accession.

4.6. Analysis of Viral Infection by PCR in Asymptomatic Plants

Tissue samples were collected from distal leaves (new leaves) at 14 dpi from plants of each accession that did not exhibit characteristic viral symptoms. For DNA extraction, 0.01 grams of pulverized tissue were used following the CTAB protocol with modifications [

37]. To detect PepGMV and PHYV viral DNA, 20 ng of DNA were used for PCR. Amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (SelectCycler™ II. Select BioProducts) using virus specific primers. For PepGMV, a 121 bp fragment of the Rep protein gene was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CAAAGCTGGTGATCCGAAAACG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GTTAAACGAGGATAATGGATAAGG-3′. A 104 bp fragment of the CP protein gene was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CCCATCGTGTAGGCAAGCGTTTCTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CATGACCTGTGTGTGTGGTGTGTGTGTGTTCTTG-3′ [

20]. For PHYVV, a 142 bp fragment of the Rep protein gene was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CGTCTCCCTCAACTACAAAACC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-ATCGGTTGTTCGTGCATTGG-3′. For the CP protein gene, a 99 bp fragment was amplified using the forward primer 5′-CCTCAGCTTGGGTTAATCGC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CCTTACAGGGACCTTCACAACC-3′ [

38]. PCR conditions for both viruses were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under ultraviolet light using a DyNA Dual-Intensity UV Transilluminator.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

The weekly data on symptom severity, recorded by plant and accession, were organized into a database for statistical analysis. The mean weekly severity per accession caused by each virus was estimated, along with the percentage of incidence (% of plants with severity > 0). Based on the data on mean severity and incidence, the Area Under the Disease Progression Curve (AUDPC) was calculated use formula proposed by Pedroza [

39]. AUDPC values were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test to detect significant differences in disease progression and total disease accumulation among accessions.

The response of pepper accessions to viral inoculation was analyzed independently for each virus (PepGMV and PHYVV). For each case, a two-way factorial ANOVA was performed considering the effects of accession and time (dpi) on symptom severity. Differences among accessions at 35 dpi were analyzed using Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). The effect of domestication level on virus induce severity was assessed by grouping accessions into domesticated, semidomesticated, and wild accessions categories. Differences in severity at 35 dpi among these groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (p < 0.05).

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.3), and graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism (version 10.5.0).

5. Conclusions

This study revealed significant variability in symptom severity, incidence, and area under the disease progression curve (AUDPC) among C. annuum accessions inoculated with the begomoviruses PepGMV and PHYVV. Wild and semidomesticated accessions exhibited lower susceptibility compared to domesticated ones, suggesting that the degree of domestication influences resistance levels to these viral pathogens. Notably, the wild accession Acc-106 (from Tabasco) showed resistance to PepGMV and tolerant behavior against PHYVV, highlighting its potential as a valuable genetic resource for breeding programs targeting viral resistance. Overall, this work underscore of Mexican wild germplasm as potential source of resistance genes against begomoviruses in pepper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KVLR. and DLTS.; methodology, KVLR., JFMD. and DLTS.; formal analysis, JJLR. and EGG.; investigation, KVLR.; writing—original draft preparation, KVLR.; writing—review and editing, JJLR., EGG., JFMD., JSR., DLTS. and RRB.; supervision, JJLR., EGG., JFMD., JSR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Autonomous University of Aguascalientes under research projects number PIBT23-1 and PIAgRN-24-1.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the other specific data is available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the grant awarded by SECRETARIA DE CIENCIA, HUMANIDADES, TECNOLOGÍA E INNOVACION (SECIHTI), grant number 667012.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, Y.H.; Jung, M.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, P.H.; Her, N.H.; Lee, J.H.; Ryu, K.H.; Paek, K.Y.; Harn, C.H. Transgenic peppers that are highly tolerant to a new CMV pathotype. Plant Cell Reports 2009, 28, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Tiznado, J.A.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Ascencio-Ibanez, J.T.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Inoculation of peppers with infectious clones of a new geminivirus by a biolistic procedure. Phytopathology-New York And Baltimore Then St Paul 1993, 83, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo Gracia-Medrano, R.M.; Maldonado-Borges, J.I.; Sánchez-Cach, L.A.; Minero-García, Y.; Hernández-Zepeda, C.; Moreno-Valenzuela, O.A. Preliminary identification and phylogenetic relationships of begomoviruses associated with Capsicum spp. in the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Revista mexicana de fitopatología 2022, 40, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Tiznado, J.A.; Acosta-García, G.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; González-Chavira, M.; Rivera Bustamante, R.F.; Maya-Hernández, V.; Guevara-González, R.G. Presence of the Geminivirus, Huasteco del Chile (PHV), Texan Tamaulipas Chili Variant (TPV-T) and Chinese Tomato (VCDT), in the states of Guanajuato, Jalisco and San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 2002, 20, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Lozano, J.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Fauquet, C.M.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Interactions between Geminiviruses in a naturally occurring mixture: Pepper huasteco virus and Pepper golden mosaic virus. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pacheco, I.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A.; Brown, J.K.; Becerra-Flora, A.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Detection and distribution of geminiviruses in Mexico and the southern United States. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Espinal, L.A.; Enríquez-Verdugo, I.; Melgoza-Villagómez, C.M.; Retes-Manjarrez, J.E.; Velarde-Félix, S.; Linares-Flores, P.J.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A. Phylogenetic analysis and distribution of Begomovirus in the culture of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) in Sinaloa, Mexico. Revista fitotecnia Mexicana 2018, 41, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Aguilar, J.J.; Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Camacho-Beltrán, E.; López-Luque, C.A.; Leyva-López, N.E.; Jiménez-Díaz, F.; Voloudakis, A.; Santos-Cervantes, M.E.; Méndez-Lozano, J. Identification of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus, Pepper huasteco yellow vein virus and Pepper golden mosaic virus associated with pepper diseases in northern Mexico. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2019, 41, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Macorra, E.J.; Ávila-Alistac, N.; Lagunes-Fortiz, E. Viruses and viroids in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria as a management alternative. Phytopathology 2023, 41, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. RNA silencing against geminivirus: complementary action of posttranscriptional gene silencing and transcriptional gene silencing in host recovery. Journal of virology 2009, 83, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodelo-Urrego, M.; García-Arenal, F.; Pagan, I. The effect of ecosystem biodiversity on virus genetic diversity depends on virus species: A study of chiltepin-infecting begomoviruses in Mexico. Virus Evolution 2015, 1, vev004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Nájera, J.F.; Aybar-Serna, S.; Arispe-Vázquez, J.L.; Terrones-Salgado, J.; Flores-Yáñez, A.; Vargas-Hernández, M.; De Lira-Ramos, K.V.; Carnero-Avilés, L.; Felipe-Victoriano, M.; Mayo-Hernández, J. Report of Pepper golden mosaic virus in Native Apaxtleco Chili Pepper in Guerrero, Mexico. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 2025, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, B.K.; Dasgupta, I. Begomovirus research in India: a critical appraisal and the way ahead. Journal of Biosciences 2012, 37, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Verdugo, S.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F.; Vázquez-Yanes, C.; Oyama, K. The wild relatives of the chili pepper (Capsicum spp.) as genetic resources. Boletín Sociedad Botánica de México 1998, 62, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Verdugo, S.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F.; Oyama, K. Screening wild plants of Capsicum annuum for resistance to pepper huasteco virus (PHV): Presence of viral DNA and differentiation among populations. Euphytica 2001, 122, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez-Hernández, Y.; Anaya-López, J.L.; Díaz-Plaza, R.; González-Chavira, M.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F.; Guevara-González, R.G. Characterization of resistance to pepper huasteco geminivirus in chili peppers from Yucatan, Mexico. HortScience 2001, 36, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Pacheco, A.; Joaquín-Ramos, A.D.J.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; González-Chavira, M.M.; Perez-Perez, M.C.I.; Guevara-Olvera, L.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.G. Analysis of transcriptional expressions induced in Capsicum chinense BG-3821 under conditions of biotic and abiotic stress. Agrociencia 2008, 42, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Anaya-López, J.L.; Pérez-Mora, E.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Muñoz-Sánchez, C.I.; Guevara-Olvera, L.; González-Chavira, M.M. Inducible gene expression by Pepper huasteco virus in Capsicum chinense plants with resistance to geminivirus infections. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2005, 27, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Neria, M.A.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Characterization of Geminivirus resistance in an accession of Capsicum chinense Jacq. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2011, 24, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Lozoya-Gloria, E.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Symptom remission and specific resistance of pepper plants after infection by Pepper golden mosaic virus. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentería-Canett, I.; Xoconostle-Cázares, B.; Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Geminivirus mixed infection on pepper plants: synergistic interaction between PHYVV and PepGMV. Virology journal 2011, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, K.; Rodríguez-Mora, D.M.; Vaca-Vaca, J.C. Optimization of the conditions of inoculation by bioballistics of a Begomovirus in tomato and tobacco. Colombian Journal of Biotechnology 2013, 15, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasca-González, M.R.; Rivera-Herrera, Y.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; González-Chavira, M.M.; Guevara-Olvera, L.; Muñoz-Sánchez, C.I.; Guevara-González, R.G. Study of the transcriptome in Capsicum chinense Jacq. resistant to the huasteco yellow vein virus of the chili. Agrociencia 2008, 42, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pickersgill, B. Relationships between weedy and cultivated forms in some species of chili peppers (genus Capsicum). Evolution 1971, 25, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R.S.; Purugganan, M.D. Evolution of crop species: genetics of domestication and diversification. Nature reviews genetics 2013, 14, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, R.; Hodgkin, T. The use of wild relatives in crop improvement: a survey of developments over the last 20 years. Euphytica 2007, 156, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retes-Manjarrez, J.E.; Hernández-Verdugo, S.; Pariaud, B.; Melgoza-Villagómez, C.M.; Pacheco-Olvera, A.; Parra-Terraza, S.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A. Detección de resistencia al virus huasteco vena amarilla del chile y su heredabilidad en genotipos silvestres de Capsicum annuum L. Interciencia 2016, 41, 541–547. Interciencia 2016, 41, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Retes-Manjarrez, J.E.; Hernández-Verdugo, S.; Pariaud, B.; Hernández-Espinal, L.A.; Parra-Terraza, S.; Trejo-Saavedra, D.L.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F.; Garzón-Tiznado, J.A. Resistance to Pepper huasteco yellow vein virus and its heritability in wild genotypes of Capsicum annuum. Botanical Sciences 2018, 96, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, R. The movement of viruses in plants. Annual Review of Phytopathology 1989, 27, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.R.; Hagen, C.; Lucas, W.J.; Gilbertson, R.L. Exploiting chinks in the plant’s armor: Evolution and emergence of geminiviruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 2005, 43, 361–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-López, J.L.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; González-Chavira, M.; Garzon-Tiznado, J.A.; Pons-Hernandez, J.L.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Hernández-Verdugo, S. Resistance to geminivirus mixed infections in Mexican wild peppers. HortScience 2003, 38, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Pacheco, I. Geminiviruses involved in the yellow curl of the chili: Interactions between PHV and TPV. Dissertation, Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the I.P.N, Irapuato Unit, Irapuato, Guanajuato, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shaner, G.; Finney, R.E. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on the expression of slow-mildewing resistance in Knox wheat. Phytopathology 1977, 67, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, I.; Piepho, H.P. The area under the disease progress stairs: calculation, advantage, and application. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nevárez, G.; Quiñones-Pando, F.J.; Luján-Favela, M.; Chávez-Sánchez, N. Integrated management of chili weevil. Delicias, Chihuahua, Mexico. INIFAP 2010, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Tena, A.; Rodríguez-Alvarado, G.; Luna-Ruíz, J.J.; Arreola-Romero, V.; Arriaga-Solorio, K.L.; Gómez-Dorantes, N.; Fernández-Pavía, S.P. Tolerance to virulence phenotypes of Phytophthora capsici in pasilla pepper cultivars. HortScience 2021, 56, 1239–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 1990, 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Gandarilla, M.G.; Rodríguez-Negrete, E.A.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Superinfection by PHYVV alters the recovery process in PepGMV-infected pepper plants. Viruses 2020, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroza, S.A. Analysis of the area under the disease progression curve. Quantitative Phytopathology: A Statistical Approach in Epidemic Analysis Minicourse. In X Congreso de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Fitopatología, XXVI Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Fitopatología 1999, September.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).