Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

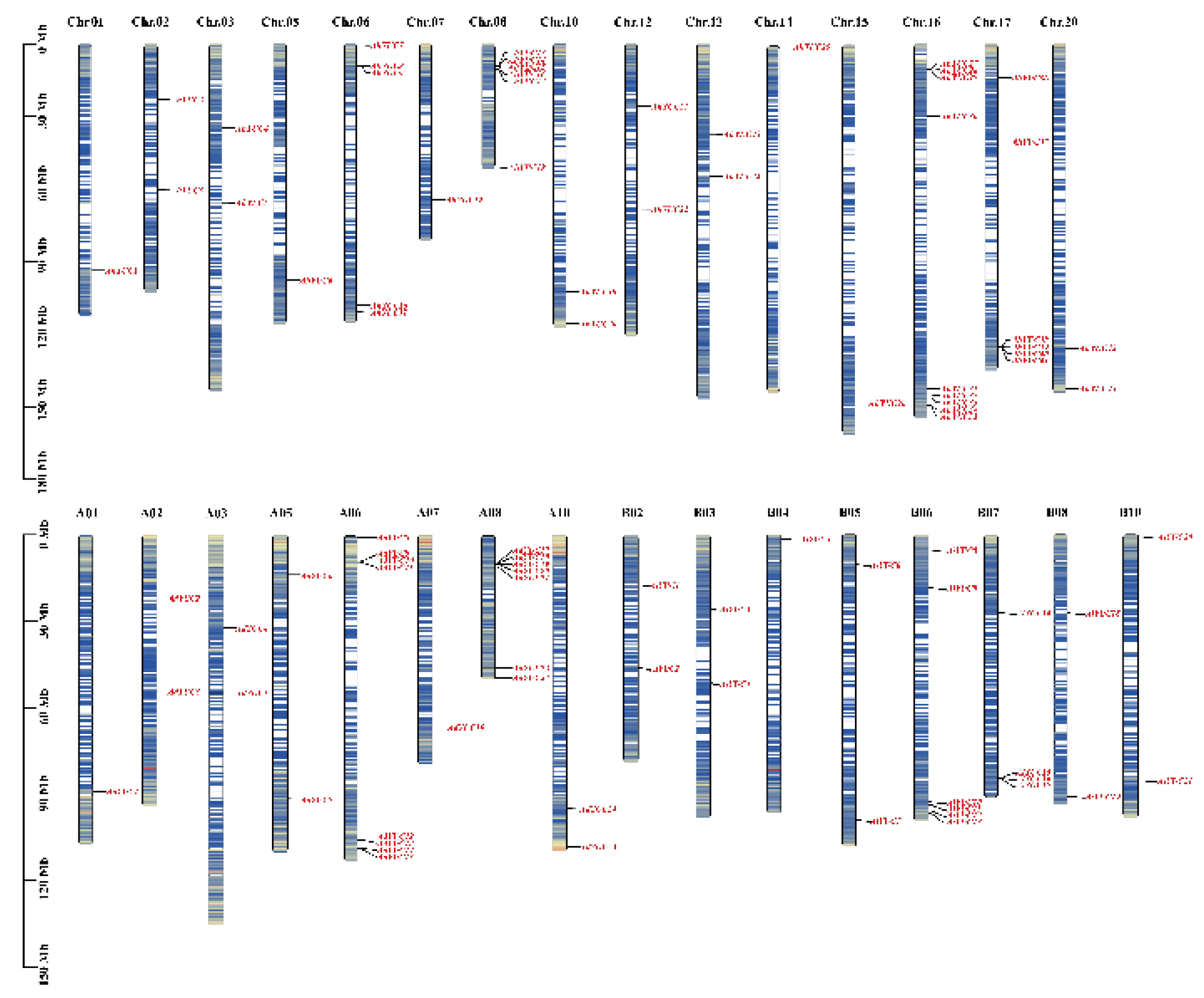

2.1. Identification of Peanut YUC Members and Chromosome Location

2.2. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization Prediction of Peanut YUC Members

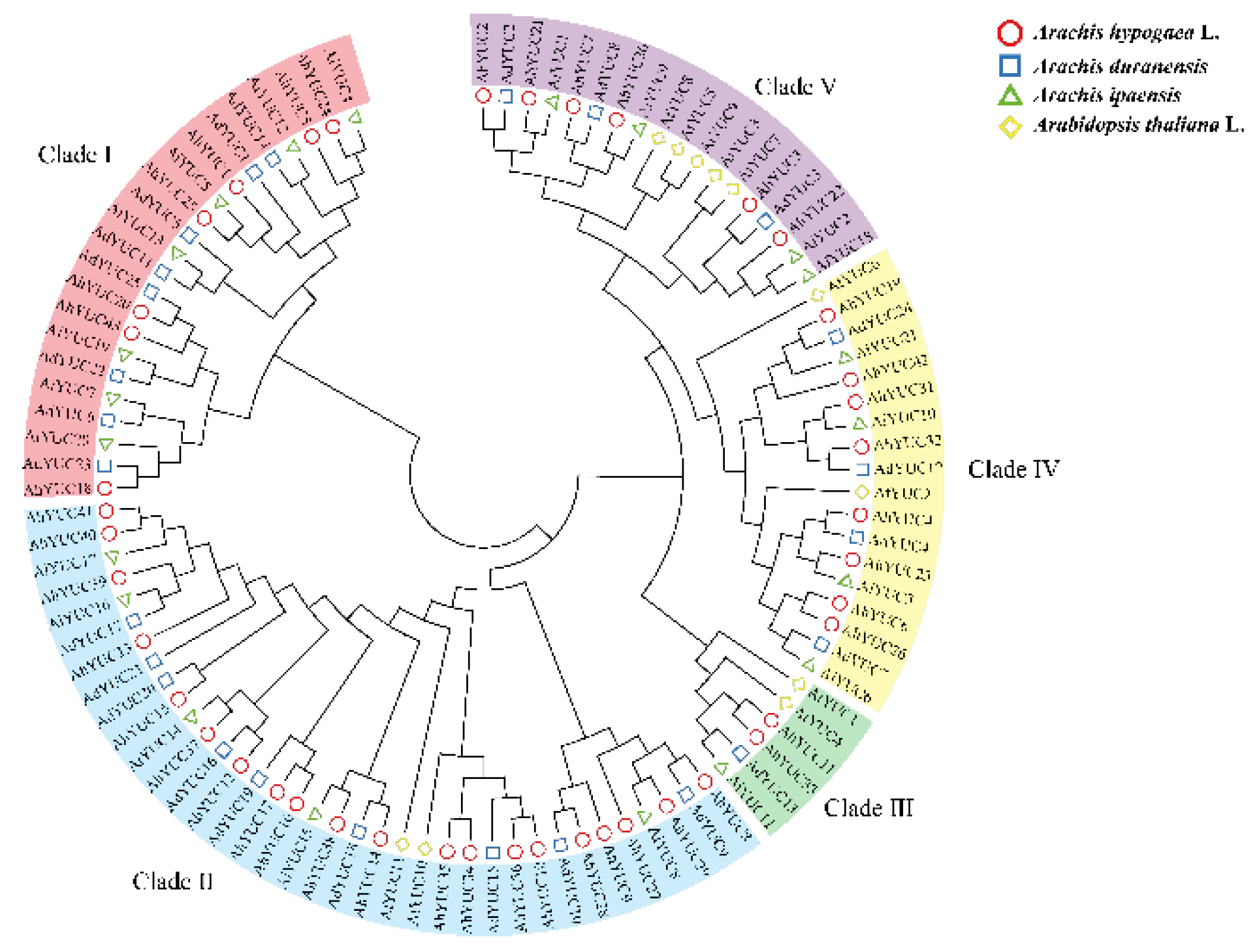

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of Peanut YUC Members

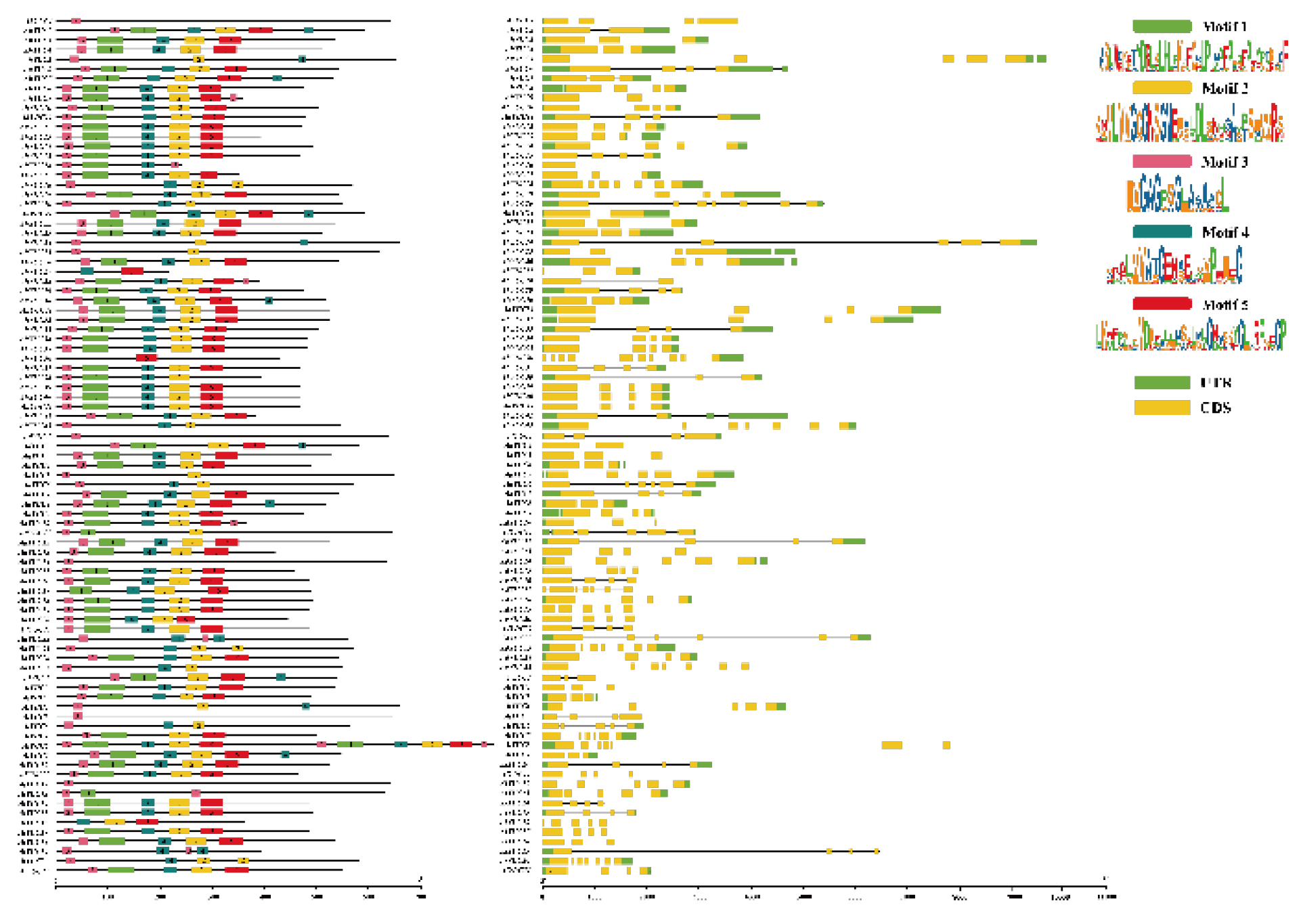

2.4. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structural of Peanut YUC Members

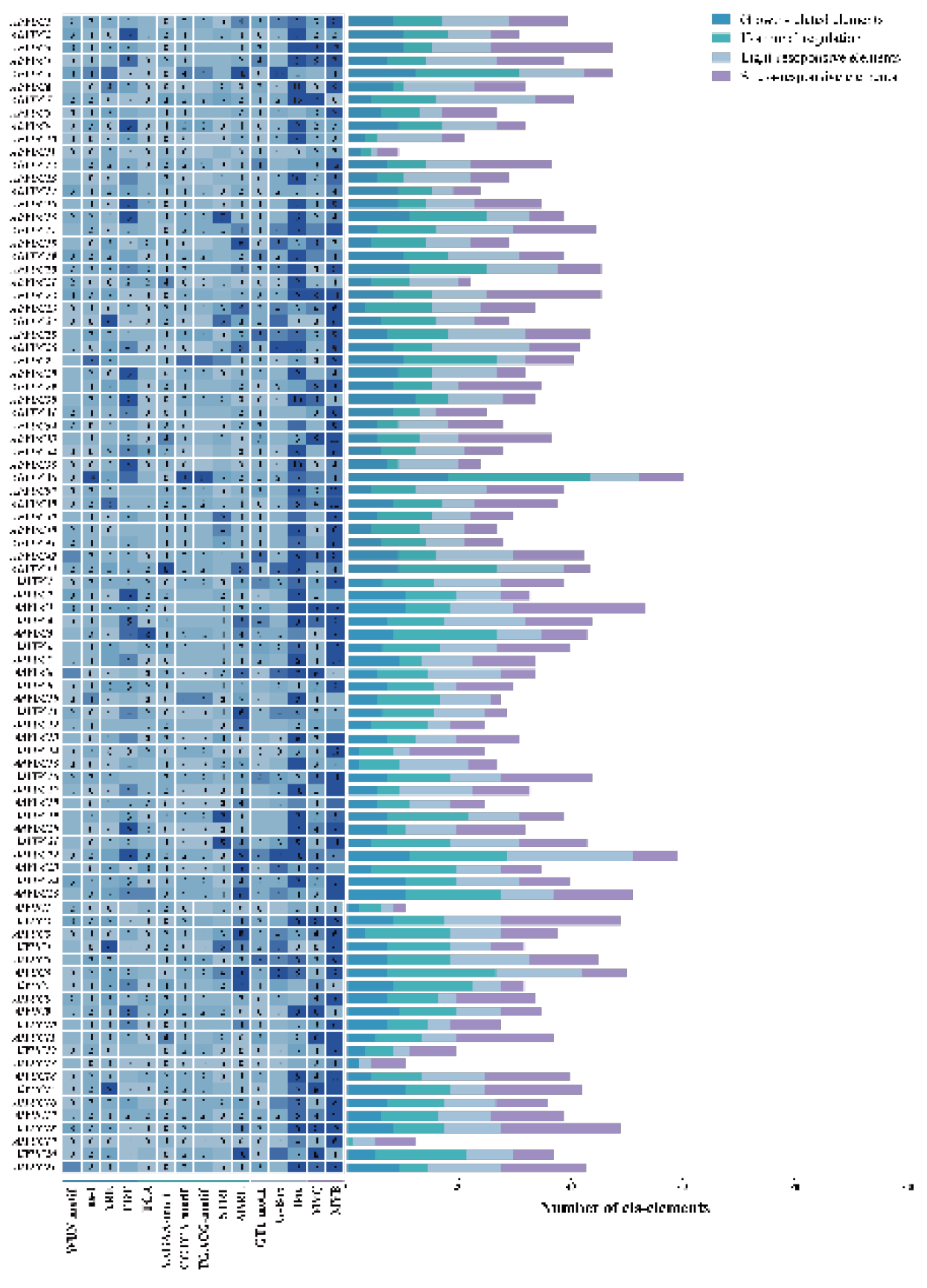

2.5. Cis-Acting Elements of Peanut YUC Genes in the Promoter Region

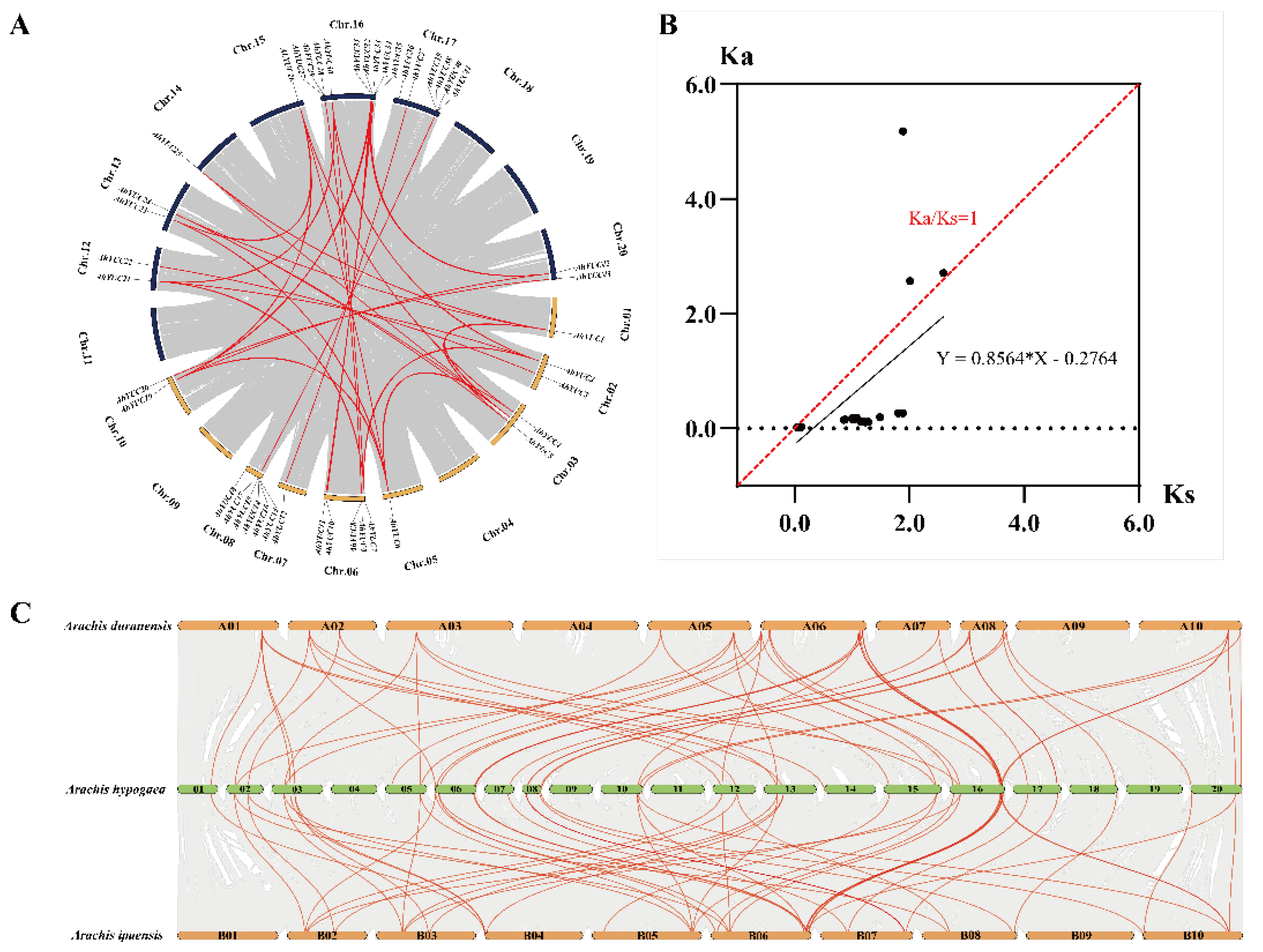

2.6. Collinearity and Estimation of Ka/Ks Ratios of YUC Genes in Peanut

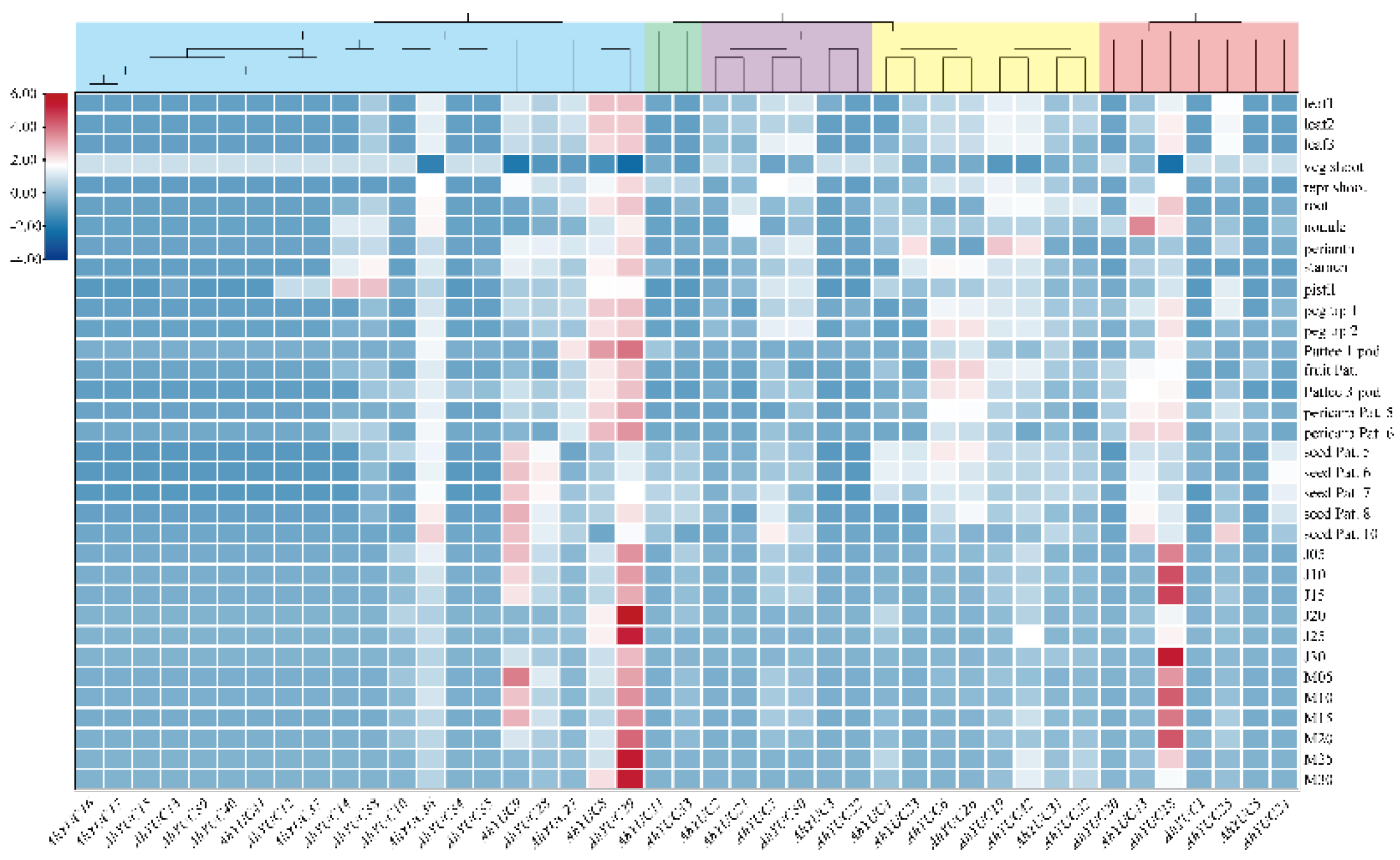

2.7. Expression Patterns of AhYUCs in Different Tissues

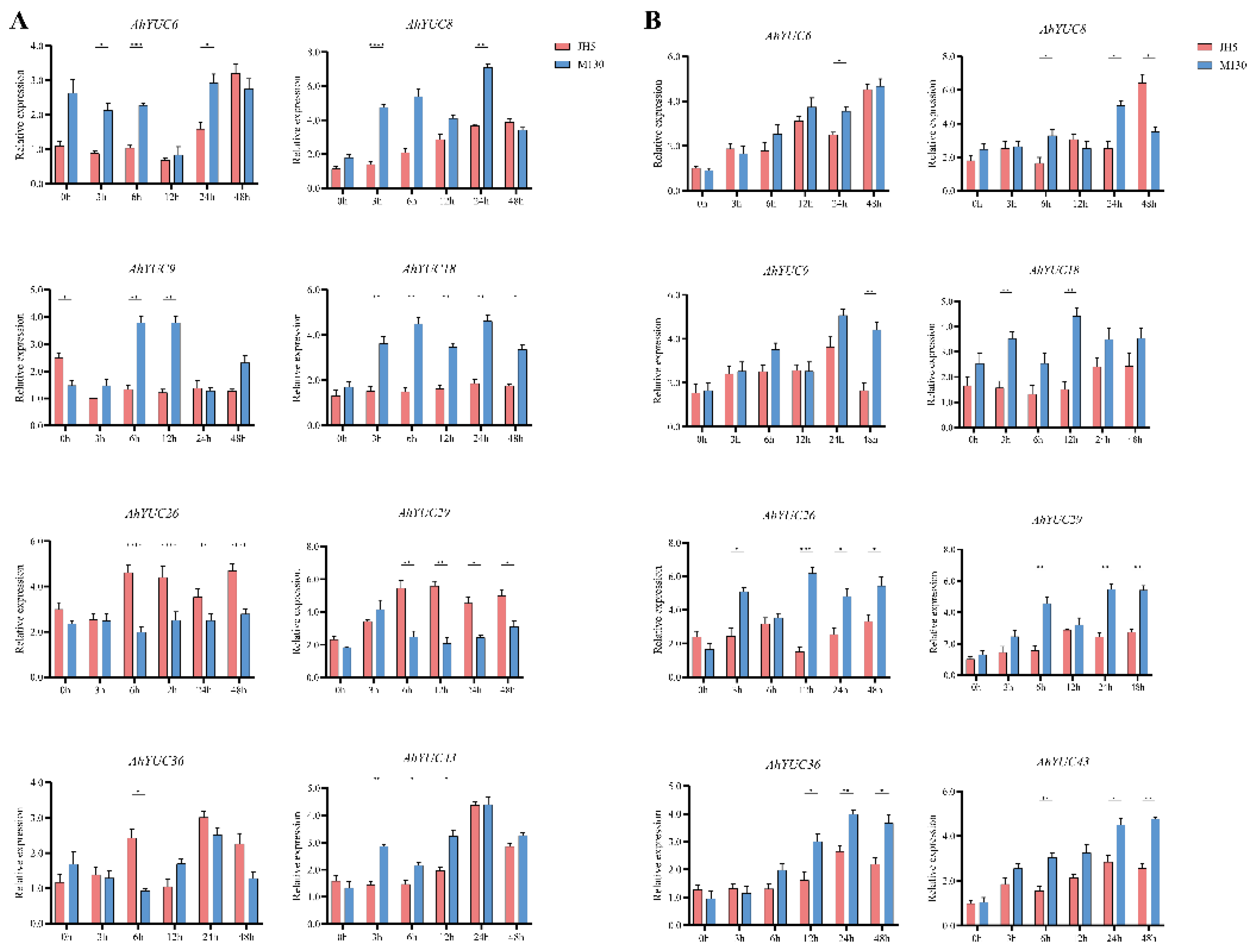

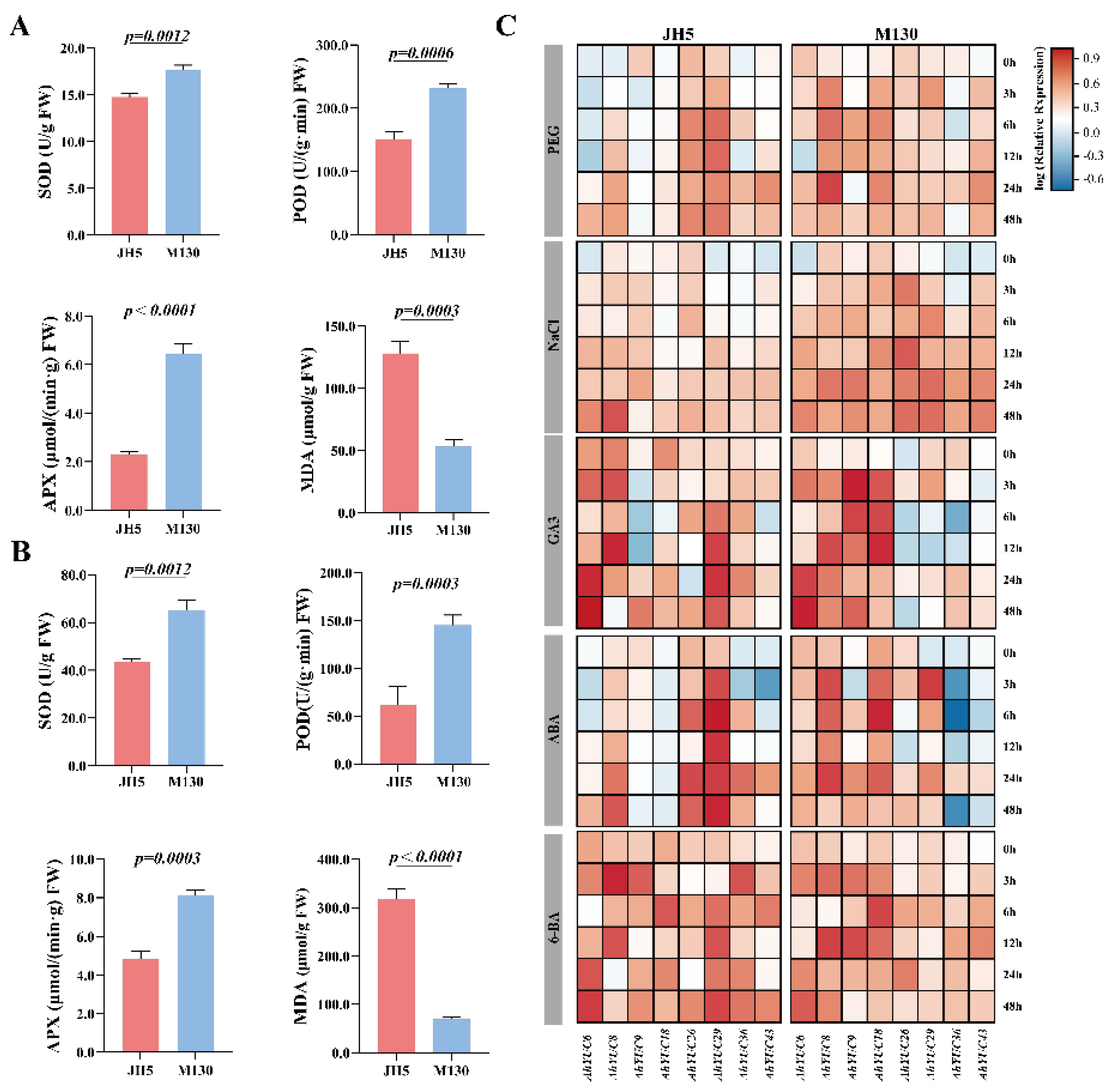

2.8. Physiological and Biochemical Differences Between Two Genotypes Genotypes and Expression Analysis of AhYUC Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Chromosome Localization

4.2. Physicochemical Properties, Phylogenetic Tree and Gene Structure Analysis

4.3. Prediction of Cis–Acting Elements in the Promoter Region

4.4. Collinearity and Estimation of Ka/Ks Ratios Analysis

4.5. In Silico Expression Analysis of AhYUC Genes in Thirty-Fourt Tissues

4.6. Plant Materials, Growth Conditions and Treatments

4.7. Hormone and Abiotic Stress Treatments for qRT-PCR Analysis

4.8. RNA Extracted and qRT–PCR Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Jodder, J. miRNA-mediated regulation of auxin signaling pathway during plant development and stress responses. J Biosci. 2020, 45, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Sáez, R.; Voß, U. Auxin metabolism controls developmental decisions in Land plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Duan, Y.; Quan, R.; Feng, M.; Ren, J.; Tang, Y.; Qing, M.; Xie, K.; Guo, W.; Wu, X. CsTCP14-CsIAA4 module-mediated repression of auxin signaling regulates citrus somatic embryogenesis. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, ML.; Garay-Arroyo, A.; García-Ponce, B.; Sánchez, MP.; Álvarez-Buylla, ER. Hormonal regulation of stem cell proliferation at the Arabidopsis thaliana root stem cell niche. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 628491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukaya, H.; Kozuka, T.; Kim, GT. Genetic control of petiole length in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Lu, C.; Wu, J.; Wei, Y.; Gao, J.; Jin, J.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, G.; Yang, F. Transcriptional Cascade in the Regulation of Flowering in the Bamboo Orchid Arundina graminifolia. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonini, S.; Østergaard, L. Female reproductive organ formation: A multitasking endeavor. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2019, 131, 337–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, P.; Grierson, D.; Gao, L. Ripening and rot: How ripening processes influence disease susceptibility in fleshy fruits. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1831–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, CM. Auxin homeostasis in plant stress adaptation response. Plant Signal Behav. 2007, 2, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Di, D.-W. Precise Regulation of the TAA1/TAR-YUCCA Auxin Biosynthesis Pathway in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, J.; Shen, P.; Li, Q.; Wu, W.; Jiang, X.; Qin, L.; Huang, J.; Cao, X.; Qi, F. High-Level production of Indole-3-acetic Acid in the metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1916–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, C.; Shen, X.; Mashiguchi, K.; Zheng, Z.; Dai, X.; Cheng, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Chory, J.; Zhao, Y. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASES OF ARABIDOPSIS and YUCCAs in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18518–18523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnaev, I.I.; Gunbin, K.V.; Suslov, V.V.; Akberdin, I.R.; Kolchanov, N.A.; Afonnikov, D.A. The phylogeny of class B Flavoprotein Monooxygenases and the origin of the YUCCA protein family. Plants 2020, 9, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Yang, H.; Shang, C.; Ma, S.; Liu, L.; Cheng, J. The Roles of Auxin Biosynthesis YUCCA Gene Family in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayanathan, M.; Faryad, A.; Abeywickrama, T.D.; Christensen, J.M.; Neilsonx, E.H.J. The auxin gatekeepers: Evolution and diversification of the YUCCA family. Plant J. 2025, 124, e70563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kamiya, N.; Morinaka, Y.; Matsuoka, M.; Sazuka, T. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X. Genome-wide analysis and expression patterns of the YUCCA genes in Maize. J Genet Genomics 2015, 42, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, H.; Feng, D. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the TaYUCCA gene family in wheat. Mol Biol Rep. 2021, 48, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Li, H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the YUCCA gene family in soybean (Glycine max L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 81, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.; Fan, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Fu, J. Identification and evolution analysis of YUCCA genes of Medicago sativa and Medicago truncatula and their expression profiles under abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1268027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Che, G.; Ding, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, W.; Ning, K.; Zhao, J.; Tesfamichael, K.; et al. Different cucumber CsYUC genes regulate response to abiotic stresses and flower development. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 20760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Hu, X.; Liu, R.; Gao, T.; Zhao, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis on YUCCA gene family in Isatis indigotica fort. And IiYUCCA6-1 functional exploration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Xiao, N.; Wu, F.; Mo, B.; Kong, W.; Yu, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of YUCCA Gene Family in Mikania micrantha. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Ma, C.; Qiao, K.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Peng, R.; Fan, S.; Ma, Q. Systematical characterization of YUCCA gene family in five cotton species, and potential functions of YUCCA22 gene in drought resistance of cotton. Ind Crops Prod. 2021, 162, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Jia, Q.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Yan, Q.; Xue, C.; Chen, X.; Yuan, X. Genome-wide identification, expression analysis, and potential roles under abiotic stress of the YUCCA gene family in Mung bean (Vigna radiata L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Christensen, SK.; Fankhauser, C.; Cashman, JR.; Cohen, JD.; Weigel, D.; Chory, J. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 2001, 291, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Dai, X.; De-Paoli, H.; Cheng, Y.; Takebayashi, Y.; Kasahara, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Zhao, Y. Auxin overproduction in shoots cannot rescue auxin deficiencies in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, YM.; Park, HJ.; Su'udi, M.; Yang, JI.; Park, JJ.; Back, K.; Pake, YM.; An, G. Constitutively wilted 1, a member of the rice YUCCA gene family, is required for maintaining water homeostasis and an appropriate root to shoot ratio. Plant Mol Biol. 2007, 65, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qi, L.; Li, Y.; Chu, J.; Li, C. PIF4-mediated activation of YUCCA8 expression integrates temperature into the auxin pathway in regulating arabidopsis hypocotyl growth. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jung, J.; Han, D.; Seo, P.; Park, W.; Park, C. Activation of a flavin monooxygenase gene YUCCA7 enhances drought resistance in Arabidopsis. Planta 2012, 235, 923–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Gao, S.; Tian, H.; Wu, W.; Robert, HS.; Ding, Z. Local transcriptional control of YUCCA regulates auxin promoted root-growth inhibition in response to aluminium stress in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halward, T.; Stalker, T.; LaRue, E.; Kochert, G. Use of single-primer DNA amplifications in genetic studies of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Plant Mol Biol. 1992, 18, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Li, Z.; Sun, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Comprehensive analysis and selection of high oleic peanut varieties in China: A study on agronomic, yield, and quality traits. Oil Crop Science 2024, 9, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Jia, K.; Meng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wan, S. Transcriptome profiling of aerial and subterranean peanut pod development. Sci Data 2024, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertioli, D.J.; Cannon, S.B.; Froenicke, L.; Huang, G.; Farmer, A.D.; Cannon, E.K.; Liu, X.; Gao, D.; Clevenger, J.; Dash, S.; et al. The genome sequences of Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, the diploid ancestors of cultivated peanut. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Ji, C.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, K.; Li, F.; Li, K.; et al. Genome of an allotetraploid wild peanut Arachis monticola: a de novo assembly. Gigascience 2018, 7, giy066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertioli, D.J.; Jenkins, J.; Clevenger, J.; Dudchenko, O.; Gao, D.; Seijo, G.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C.M.; Ren, L.; Farmer, A.D.; Pandey, M.K.; et al. The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut Arachis hypogaea. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, W.; Chen, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Pandey, M.K.; Zhang, C.; Chang, W.C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Tang, R.; et al. The genome of cultivated peanut provides insight into legume karyotypes, polyploid evolution and crop domestication. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Hong, Y.; Lan, H.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; et al. Sequencing of cultivated peanut, Arachis hypogaea, yields insights into genome evolution and oil improvement. Mol. Plant. 2019, 12, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Qi, F.; Zhou, Z.; Du, P.; Shi, L.; Dong, W.; Huang, B.; Han, S.; Pavan, S.; et al. A telomere-to-telomere genome assembly of the cultivated peanut. Mol Plant. 2025, 6, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xue, H.; Li, G.; Chitikineni, A.; Fan, Y.; Cao, Z.; Dong, X.; Lu, H.; Zhao, K.; et al. Pangenome analysis reveals structural variation associated with seed size and weight traits in peanut. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; He, M.; Li, L.; Cui, S.; Hou, M.; Wang, L.; Mu, G.; Liu, L.; Yang, X. Identification and expression analysis of WRKY gene family under drought stress in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huai, D.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, L.; Jiang, H.; et al. Genome-wide identification of peanut PIF family genes and their potential roles in early pod development. Gene. 2021, 781, 145539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, L.; Wan, L.; Huai, D.; Kang, Y.; Shi, L.; Jiang, H.; Lei, Y.; Liao, B. Genome-wide systematic characterization of bZIP transcription factors and their expression profiles during seed development and in response to salt stress in peanut. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Miao, P.; Mu, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Meng, C.; Yang, X. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Expression Profile of F-Box Protein Family Genes Shed Light on Lateral Branch Development in Cultivated Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Horticulturae. 2024, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Yi, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, F.; Feng, J. Two complete telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies of Medicago reveal the landscape and evolution of its centromeres. Mol Plant. 2025, 18, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 48; Liang, S.; Duan, Z.; He, X.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, Q.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; et al. Natural variation in GmSW17 controls seed size in soybean. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 7417. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Cui, C.; Chai, L.; Zheng, B.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Tu, J. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of the YUCCA gene family in Brassica napus. Oil Crop Sci. 2022, 7, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, B.; Geng, X.; Ding, X.; Yan, N.; Wang, W.; Sun, X.; Zheng, C. Biological function and stress response mechanism of MYB transcription factor family genes. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Deng, X.; Li, J. MYB112 connects light and circadian clock signals to promote hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2023, 35, 3485–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qi, L.; Li, Y.; Chu, J.; Li, C. PIF4–mediated activation of YUCCA8 expression integrates temperature into the auxin pathway in regulating Arabidopsis hypocotyl growth. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkens, A.; Schindler, U.; Cashmore, A. The G-box: a ubiquitous regulatory DNA element in plants bound by the GBF family of bZIP proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 1995, 20, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woude, L.; Perrella, G.; Snoek, B.; Hoogdalem, M.; Novák, O.; Verk, M.; Kooten, H.; Zorn, L.; Tonckens, R.; Dongus, J.; et al. HISTONE DEACETYLASE 9 stimulates auxin-dependent thermomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana by mediating H2A.Z depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 25343–25354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alonso, M.-M.; Sánchez-Parra, B.; Ortiz-García, P.; Santamaría, M.E.; Díaz, I.; Pollmann, S. Jasmonic Acid-Dependent MYC Transcription Factors Bind to a Tandem G-Box Motif in the YUCCA8 and YUCCA9 Promoters to Regulate Biotic Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y. The Arabidopsis MATERNAL EFFECT EMBRYO ARREST45 protein modulates maternal auxin biosynthesis and controls seed size by inducing AINTEGUMENTA. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 1907–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2430–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Tian, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z. Auxin production in diploid microsporocytes is necessary and sufficient for early stages of pollen development. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Qin, G.; Tsuge, T.; Hou, X.; Ding, M.; Aoyama, T.; Oka, A.; Chen, Z.; Gu, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. SPOROCYTELESS modulates YUCCA expression to regulate the development of lateral organs in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jung, J.; Han, D.; Seo, P.; Park, W.; Park, C. Activation of a flavin monooxygenase gene YUCCA7 enhances drought resistance in Arabidopsis. Comparative Study 2012, 235, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, S.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Z.; Shang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H. Overexpression of auxin synthesis gene PagYUC6a in poplar (Populus alba × P. glandulosa) enhances salt tolerance. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025, 311, 143712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorrai, R.; Boccaccini, A.; Ruta, V.; Possenti, M.; Costantino, P.; Vittorioso, P. Abscisic acid inhibits hypocotyl elongation acting on gibberellins, DELLA proteins and auxin. AoB Plants 2018, 10, ply061. [Google Scholar]

- Voorrips, R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Appel, R.D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; Kissinger, J.C. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools-II: A "one for all, all for one" bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant. 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A Toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevenger, J.; Chu, Y.; Scheffler, B.; Ozias-Akins, P. A developmental transcriptome map for allotetraploid Arachis hypogaea. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cui, S.; Dang, P.; Yang, X.; Wei, X.; Chen, K.; Liu, L.; Chen, C.Y. GWAS and bulked segregant analysis reveal the Loci controlling growth habit-related traits in cultivated Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Mu, G. Multi-omics and miRNA interaction joint analysis highlight new insights into anthocyanin biosynthesis in peanuts (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 818345. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).