Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Sequence Analysis of XTH Genes

2.2. Phylogenetic Classification of ZjXTH, Their Motif, and Gene Structure Analysis

2.3. Chromosomal Localization, Synteny Analysis, and PPI of ZjXTH Genes

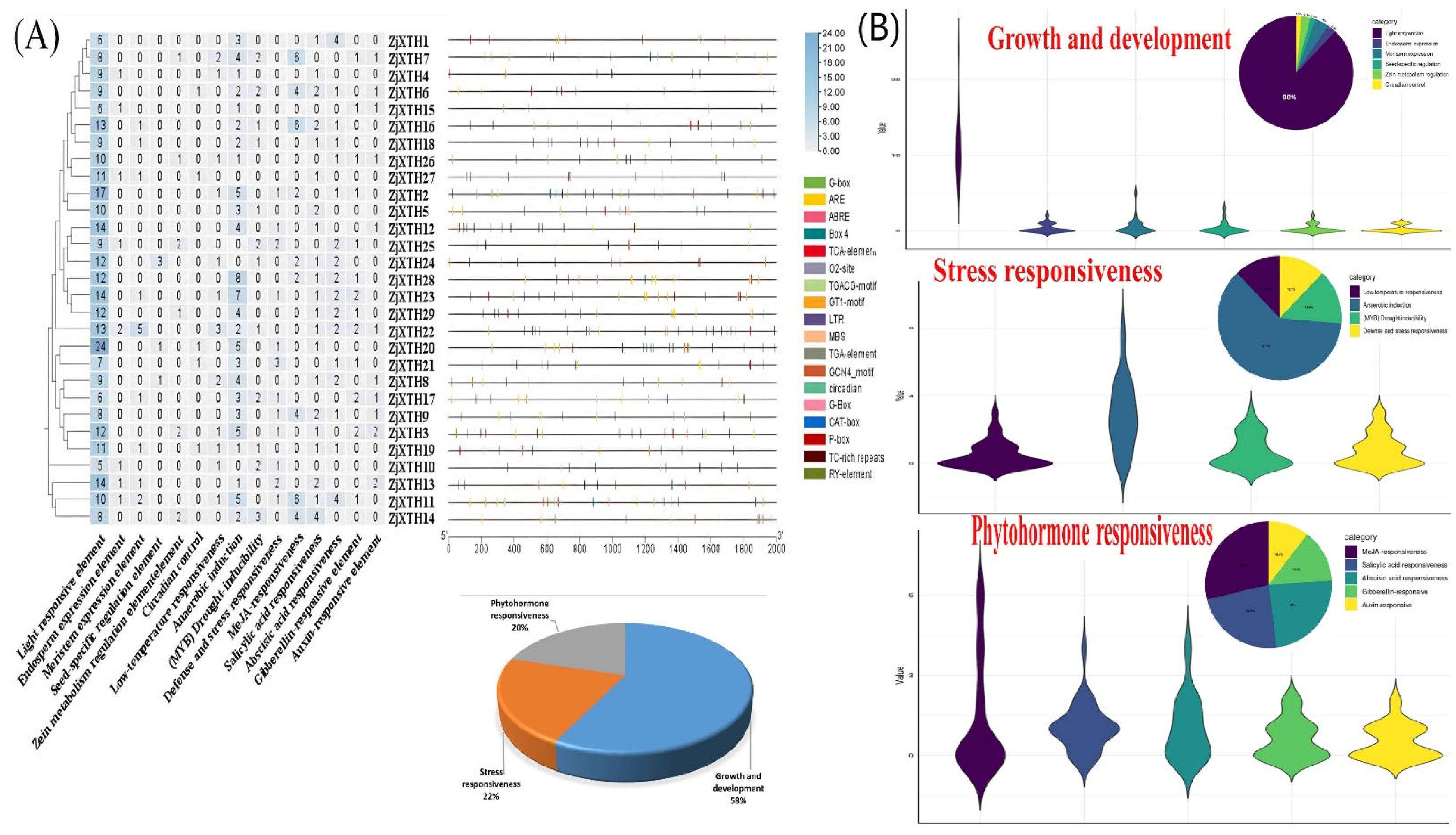

2.4. Cis-Regulatory Elements in the Promoter Region of ZjXTH

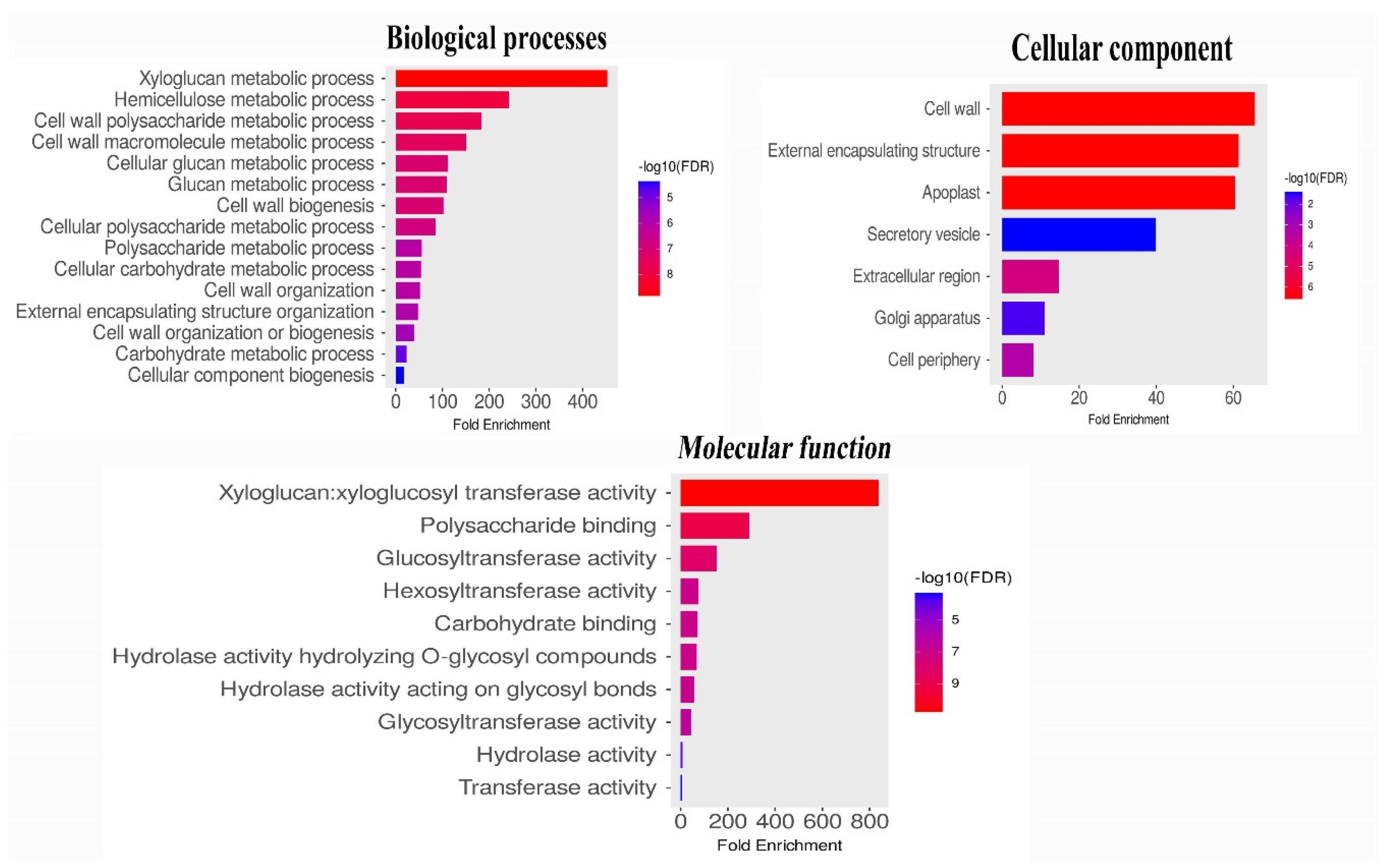

2.5. Functional GO Annotation and Ka/KS Analysis of ZjXTHs

2.6. Expression Patterns of ZjXTHs on Subcellular Levels and Different Tissues

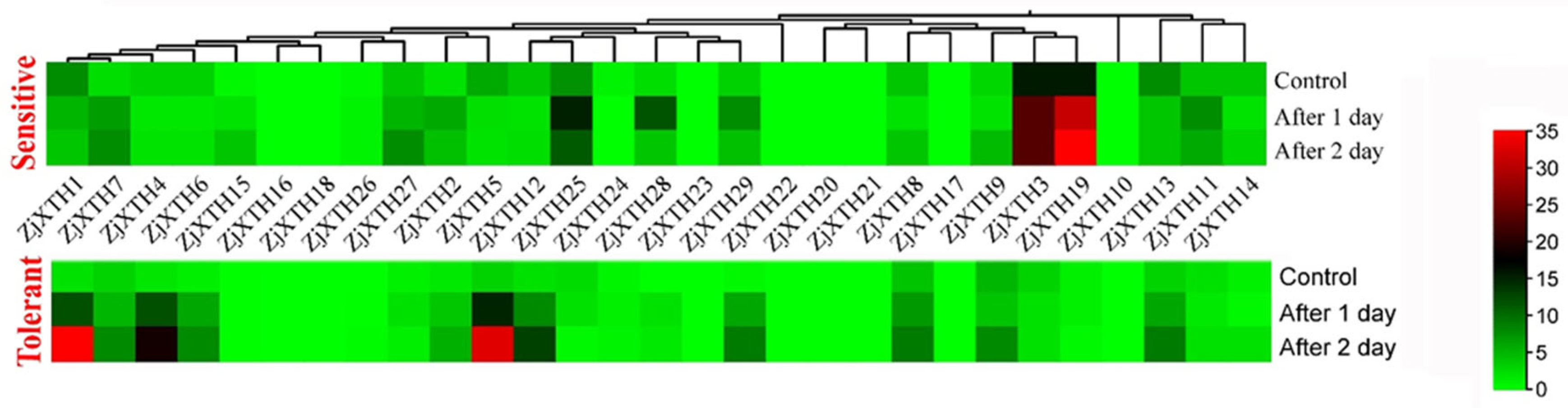

2.7. Expression Profiles of ZjXTH Under Salt Stress

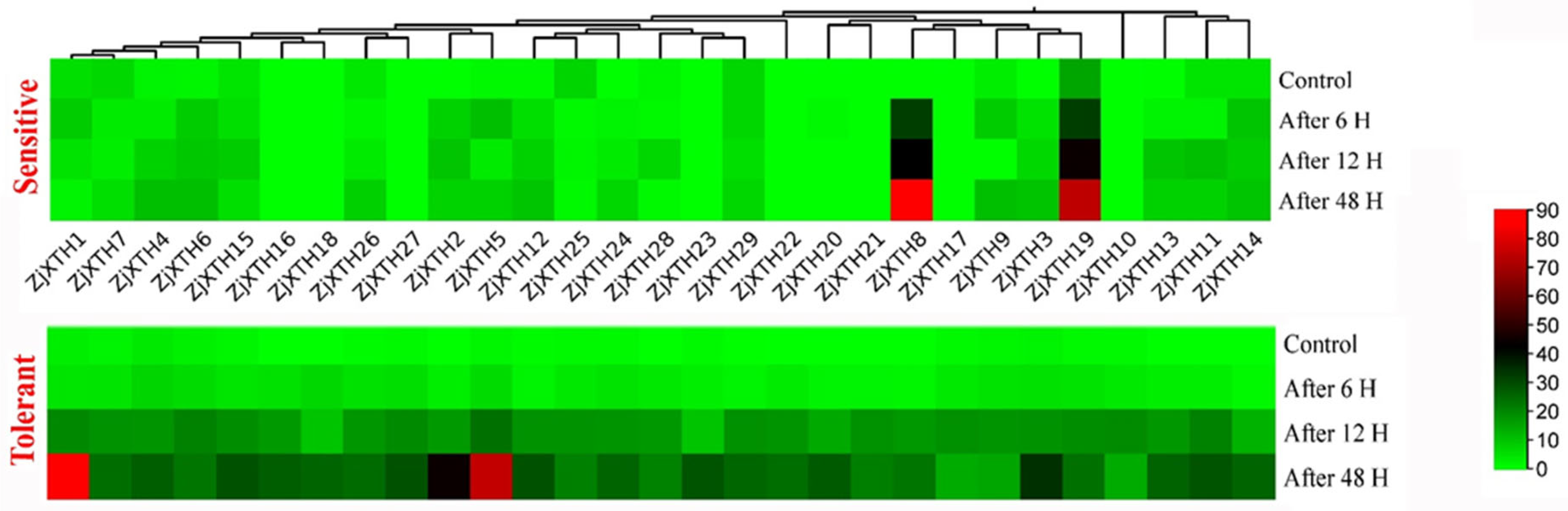

2.8. Expression Profiles of ZjXTH Under Drought Stress

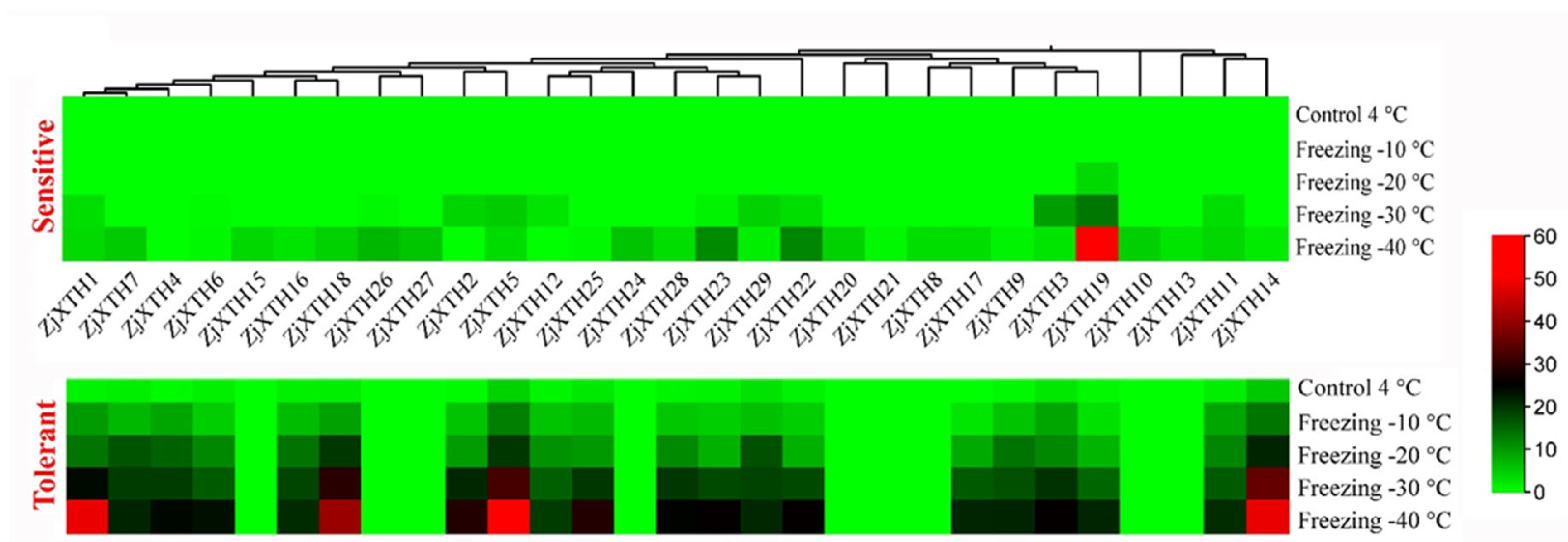

2.9. Expression Profiles of ZjXTH Under Freezing Stress

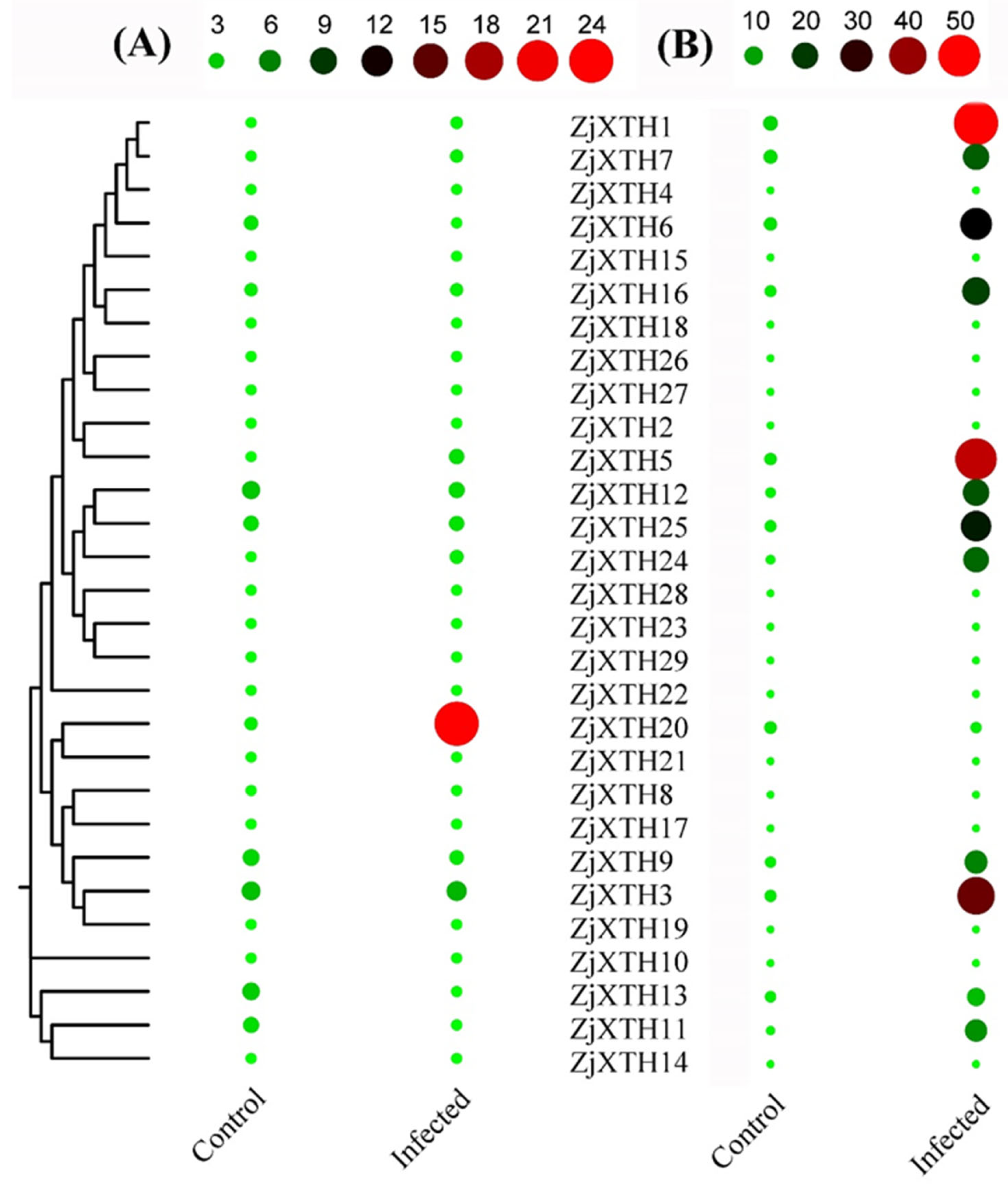

2.10. Expression Profiles of ZjXTH Response to Phytoplasma Infection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genome-Wide Identification of XTH Genes

4.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

4.3. Motif Analysis and Exon-Intron Structure of ZjXTHs

4.4. Chromosomal Locations, Synteny and Duplications Analyses of ZjXTHs

4.5. Cis-Element Putative Promoter Regions and Ka/Ks Analysis

4.6. Protein Interaction Network and Gene Ontology

4.7. Gene Expression Analysis of ZjXTH Genes Under Various Stresses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Carpita, N. C.; Gibeaut, D. M. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. The Plant Journal 1993, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, C.; Bauer, S.; Brininstool, G.; Facette, M.; Hamann, T.; Milne, J.; et al. Toward a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 2004, 306, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novaković, L.; Guo, T.; Bacic, A.; Sampathkumar, A.; Johnson, K. L. Hitting the wall—sensing and signaling pathways involved in plant cell wall remodeling in response to abiotic stress. Plants 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y. The plant cell wall: Biosynthesis, construction, and functions. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2021, 63, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk, I.; Fisher, L. H. C.; Vickers, M.; Akinyemi, A.; Didion, T.; Swain, M.; et al. Transcriptional and metabolomic analyses indicate that cell wall properties are associated with drought tolerance in Brachypodium distachyon. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, K.; Tucker, M. R.; Chowdhury, J.; Shirley, N.; Little, A. The plant cell wall: a complex and dynamic structure as revealed by the responses of genes under stress conditions. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J. K. C.; Braam, J.; Fry, S. C.; Nishitani, K. The XTH family of enzymes involved in xyloglucan endotransglucosylation and endohydrolysis: current perspectives and a new unifying nomenclature. Plant and cell physiology 2002, 43, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sandt, V. S. T.; Suslov, D.; Verbelen, J.-P.; Vissenberg, K. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase activity loosens a plant cell wall. Annals of botany 2007, 100, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedes, E.; Suslov, D.; Vandenbussche, F.; Kenobi, K.; Ivakov, A.; Van Der Straeten, D.; et al. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) overexpression affects growth and cell wall mechanics in etiolated Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Journal of experimental botany 2013, 64, 2481–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Nishitani, K. A comprehensive expression analysis of all members of a gene family encoding cell-wall enzymes allowed us to predict cis-regulatory regions involved in cell-wall construction in specific organs of Arabidopsis. Plant and cell physiology 2001, 42, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M. J.; Eklöf, J. M.; Michel, G.; Kallas, A. M.; Teeri, T. T.; Czjzek, M.; et al. Structural Evidence for the Evolution of Xyloglucanase Activity from Xyloglucan Endo-Transglycosylases: Biological Implications for Cell Wall Metabolism. The Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1947–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Ding, M.; Zhao, R.; Deng, S.; et al. Populus euphratica XTH overexpression enhances salinity tolerance by the development of leaf succulence in transgenic tobacco plants. Journal of experimental botany 2013, 64, 4225–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, R.; Rose, J. K. C.; Nishitani, K. A surprising diversity and abundance of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolases in rice. Classification and expression analysis. Plant Physiology 2004, 134, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saladié, M.; Rose, J. K. C.; Cosgrove, D. J.; Catalá, C. Characterization of a new xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) from ripening tomato fruit and implications for the diverse modes of enzymic action. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 2006, 47, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Valliyodan, B.; Prince, S.; Wan, J.; Nguyen, H. T. Characterization of the XTH gene family: new insight to the roles in soybean flooding tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Liu, A.; Qu, X.; Liang, J.; Song, M. Genome-wide identification, and phylogenetic and expression profiling analyses, of XTH gene families in Brassica rapa L. and Brassica oleracea L. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cui, C.; Xing, A.; Xu, X.; Sun, Y.; Tian, Z.; et al. Identification and response analysis of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolases (XTH) family to fluoride and aluminum treatment in Camellia sinensis. BMC genomics 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Kong, D.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Tahir, M.; et al. Identification of High Tolerance to Jujube Witches’ Broom in Indian Jujube (Ziziphus mauritiana Lam.) and Mining Differentially Expressed Genes Related to the Tolerance through Transcriptome Analysis. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Y.; Seo, Y. S.; Kim, S. J.; Kim, W. T.; Shin, J. S. Constitutive expression of CaXTH3, a hot pepper xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase, enhanced tolerance to salt and drought stresses without phenotypic defects in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Dotaerang). Plant cell reports 2011, 30, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. F.; Shi, Y. Z.; Lei, G. J.; Fry, S. C.; Zhang, B. C.; Zhou, Y. H.; et al. XTH31, Encoding an in Vitro XEH/XET-Active Enzyme, Regulates Aluminum Sensitivity by Modulating in Vivo XET Action, Cell Wall Xyloglucan Content, and Aluminum Binding Capacity in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4731–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; He, H.; Han, T.; Di, P.; Sechet, J.; et al. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase-hydrolase30 negatively affects salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany 2019, 70, 5495–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Fang, S.; Chen, H.; Cai, W. The brassinosteroid-responsive xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 19 (XTH19) and XTH23 genes are involved in lateral root development under salt stress in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 2020, 104, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, D.; Johnson, K. L.; Hao, P.; Tuong, T.; Erban, A.; Sampathkumar, A.; et al. Cell wall modification by the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase XTH19 influences freezing tolerance after cold and sub-zero acclimation. Plant, Cell & Environment 2021, 44, 915–930. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Guo, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Pang, X.; Li, Y. Autotetraploidization in Ziziphus jujuba Mill. var. spinosa enhances salt tolerance conferred by active, diverse stress responses. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 165, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yan, M.; Yu, J.; Zhou, X.; Bao, J.; et al. Effect of Saline–Alkali Stress on Sugar Metabolism of Jujube Fruit. Horticulturae. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, L.; Han, Y.; Cao, B.; Song, L. Effects of elevated temperature and drought stress on fruit coloration in the jujube variety ‘Lingwuchangzao’ (Ziziphus jujube cv. Lingwuchangzao). Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 274, 109667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Song, S.; Bo, W.; et al. Comparative transcriptome profiling reveals cold stress responsiveness in two contrasting Chinese jujube cultivars. BMC Plant Biology 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, J.; Ye, X.; Tan, B.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification of Ziziphus jujuba TCP transcription factors and their expression in response to infection with jujube witches’ broom phytoplasma. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2019, 41, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; et al. The effector PHYL1JWB from Candidatus Phytoplasma ziziphi induces abnormal floral development by destabilising flower development proteins. Plant, Cell & Environment 2024, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, A.; Dou, W.; Qi, J.; Long, Q.; Zou, X.; et al. Systematic Analysis and Functional Validation of Citrus XTH Genes Reveal the Role of Csxth04 in Citrus Bacterial Canker Resistance and Tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M. H. T.; Han, S.; Sami, A.; Haider, M. Z.; Shafiq, M.; Ali, M.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of XTH gene family in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) against different insecticides to enhance defense mechanism. Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Hou, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.; Pang, X.; et al. Multiple responses contribute to the enhanced drought tolerance of the autotetraploid Ziziphus jujuba Mill. var. spinosa. Cell & Bioscience 2021, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, B.; Ackah, M.; Jin, X.; Ayittey, D. M.; Amoako, F. K.; Zhao, W. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase (XTH) Gene Family: Expression Pattern during Magnesium Stress Treatment in the Mulberry Plant (Morus alba L.) Leaves. Plants. [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-López, L. G.; López-Espinoza, M. Y.; Juárez-Verdayes, M. A.; López-Meyer, M. Genome-wide characterization of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene family in Solanum lycopersicum L. and gene expression analysis in response to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, W. A surprising diversity of Xyloglucan Endotransglucosylase/Hydrolase in wheat: New in Sight to the roles in Drought Tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Ding, A.; Kong, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene family in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Genes 2018, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yao, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Guo, Q.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene family in poplar. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, G.; Xu, P.; Li, G.; Ma, C.; Li, P.; et al. Genome-wide identification of xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase gene family members in peanut and their expression profiles during seed germination. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Han, J.; Lu, W.; Ren, Z. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY gene family in the cucumber genome and transcriptome-wide identification of WRKY transcription factors that respond to biotic and abiotic stresses. BMC plant biology 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, C.; He, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of Expansin Genes in Wild Soybean (Glycine soja) and Functional Characterization of Expansin B1 (GsEXPB1) in Soybean Hair Root. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Talbot, M.; Llewellyn, D. J. Pectin Methylesterase and Pectin Remodelling Differ in the Fibre Walls of Two Gossypium Species with Very Different Fibre Properties. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e65131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. H.; Sohn, K. H.; Choi, H. W.; Hwang, I. S.; Lee, S. C.; Hwang, B. K. Pepper pectin methylesterase inhibitor protein CaPMEI1 is required for antifungal activity, basal disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance. Planta 2008, 228, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 43. Bethke, G.; Grundman, R. E.; Sreekanta, S.; Truman, W.; Katagiri, F.; Glazebrook, J. Arabidopsis PECTIN METHYLESTERASEs Contribute to Immunity against Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiology 2014, 164, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Jia, L.; Yang, D.; Hu, Y.; Njogu, M. K.; Wang, P.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic and Expression Pattern Analysis of GATA Family Genes in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Plants, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, S.; Xiao, Y. Light intensity affects growth, photosynthetic capability, and total flavonoid accumulation of Anoectochilus plants. HortScience 2010, 45, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, X.; Shen, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; et al. The GATA transcription factor GNC plays an important role in photosynthesis and growth in poplar. Journal of experimental botany 2020, 71, 1969–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, M. F.; Mostafa, K.; Aydin, A.; Kavas, M.; Aksoy, E. GATA transcription factor in common bean: A comprehensive genome-wide functional characterization, identification, and abiotic stress response evaluation. Plant Molecular Biology 2024, 114, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordas, C. A.; Sioulas, C. Safflower yield, chlorophyll content, photosynthesis, and water use efficiency response to nitrogen fertilization under rainfed conditions. Industrial crops and products 2008, 27, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Kim, J.; Yoon, E. K.; Jang, S.; Ko, K.; Lim, J. SHORT-ROOT controls cell elongation in the etiolated arabidopsis hypocotyl. Molecules and cells 2022, 45, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Furuta, Y.; Awano, T.; Mizuno, K.; Mitsuishi, Y.; Hayashi, T. Suppression and acceleration of cell elongation by integration of xyloglucans in pea stem segments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 9055–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. K.; Kim, J. E.; Park, J.-A.; Eom, T. J.; Kim, W. T. Constitutive expression of abiotic stress-inducible hot pepper CaXTH3, which encodes a xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase homolog, improves drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. FEBS letters 2006, 580, 3136–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.; Qiao, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of wheat xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) gene family revealed TaXTH17 involved in abiotic stress responses. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Gai, Y. Isolation and characterization of Populus xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase (XTH) involved in osmotic stress responses. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 155, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lian, B.; Lv, X.; Sun, M.; Wei, F.; An, L.; et al. Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase-hydrolase 22 positively regulates response to cold stress in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 220, 119273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhan, H.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; et al. Genome-wide identification of gene family in Musa acuminata and response analyses of and xyloglucan to low temperature. Physiologia Plantarum 2024, 176, e14231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Locations | Deduced Protein | ||||||||||||||||

| Gene Name | Protein ID | AA | bp | Chr | Signal peptide (SP) | LOC | Start | End | MW(KDa) | PI | II | AI | GRAVY | ||||

| ZjXTH1 | XP_015899780.1 | 288 | 865 | 1 | 22 | LOC107433023 | 2142963 | 2144333 | 32,104.7 | 5.24 | 38.45 | 60.31 | -0.439 | ||||

| ZjXTH2 | XP_015875377.2 | 297 | 899 | 1 | 34 | LOC107412146 | 994499 | 995798 | 33,451.7 | 5.4 | 34.94 | 77.41 | -0.292 | ||||

| ZjXTH3 | XP_015868033.1 | 336 | 1014 | 12 | 25 | LOC107405483 | 17889849 | 17892964 | 38,242.9 | 6.23 | 42.04 | 66.67 | -0.475 | ||||

| ZjXTH4 | XP_060672082.1 | 271 | 815 | 1 | _ | LOC107432095 | 2146026 | 2147442 | 30,453.67 | 5.26 | 36.72 | 55.79 | -0.577 | ||||

| ZjXTH5 | XP_015874851.4 | 296 | 877 | 1 | 30 | LOC107411692 | 1002556 | 1004014 | 33,595.72 | 6.2 | 40.42 | 69.49 | -0.401 | ||||

| ZjXTH6 | XP_015899683.3 | 291 | 878 | 1 | 25 | LOC107432937 | 2139826 | 2141413 | 32,396.09 | 5.42 | 38.32 | 64.71 | -0.374 | ||||

| ZjXTH7 | XP_015899503.3 | 292 | 867 | 1 | 25 | LOC107432789 | 2137263 | 2138660 | 32,320.89 | 5.42 | 35.55 | 62.71 | -0.398 | ||||

| ZjXTH8 | XP_015898435.1 | 293 | 881 | 11 | 19 | LOC107431919 | 7545976 | 7548758 | 33,835.31 | 9.38 | 43.23 | 62.25 | -0.499 | ||||

| ZjXTH9 | XP_048322840.2 | 310 | 928 | 12 | 27 | LOC107428620 | 6457682 | 6460783 | 34,870.81 | 8.13 | 50.18 | 77.97 | -0.137 | ||||

| ZjXTH10 | XP_015892932.3 | 295 | 883 | 9 | 26 | LOC107427100 | 15865101 | 15867060 | 34,701.11 | 8.56 | 37.48 | 66.1 | -0.513 | ||||

| ZjXTH11 | XP_015890447.3 | 293 | 882 | 7 | 30 | LOC107425034 | 14371805 | 14373572 | 33,370.77 | 6.94 | 40.81 | 72.9 | -0.31 | ||||

| ZjXTH12 | XP_015887252.2 | 281 | 842 | 3 | 29 | LOC107422327 | 13280316 | 13282451 | 32,220.62 | 9.17 | 36.22 | 74.95 | -0.3 | ||||

| ZjXTH13 | XP_015884034.2 | 304 | 911 | 1 | 33 | LOC107419753 | 16657548 | 16659222 | 35,202.27 | 4.75 | 39.29 | 64.74 | -0.518 | ||||

| ZjXTH14 | XP_048328785.2 | 292 | 875 | 4 | 24 | LOC107416878 | 25908816 | 25911364 | 33,164.31 | 5.41 | 32.69 | 69.42 | -0.275 | ||||

| ZjXTH15 | XP_015875279.3 | 292 | 882 | 1 | 27 | LOC107412056 | 979197 | 980607 | 32,874.68 | 5.82 | 38.58 | 64.49 | -0.418 | ||||

| ZjXTH16 | XP_060671190.1 | 297 | 891 | 1 | 30 | LOC107411876 | 969728 | 976681 | 33,09.22 | 6.81 | 41.14 | 68.32 | -0.367 | ||||

| ZjXTH17 | XP_015874702.3 | 283 | 851 | 10 | 19 | LOC107411602 | 17245584 | 17247133 | 31,912.58 | 6.79 | 48.08 | 64.13 | -0.494 | ||||

| ZjXTH18 | XP_048332201.1 | 294 | 884 | 1 | 29 | LOC107406936 | 2149644 | 2151057 | 33,056.15 | 8.56 | 35.37 | 69.69 | -0.296 | ||||

| ZjXTH19 | XP_048320582.2 | 352 | 1045 | 6 | 35 | LOC107403271 | 8140587 | 8143653 | 40,646.18 | 8.66 | 49.22 | 71.22 | -0.422 | ||||

| ZjXTH20 | XP_060668086.1 | 281 | 846 | 10 | 26 | LOC132799666 | 6971363 | 6973149 | 32,513.47 | 5.48 | 35.04 | 73.49 | -0.513 | ||||

| ZjXTH21 | XP_060676394.1 | 279 | 837 | 9 | _ | LOC125424114 | 6979194 | 6981594 | 32,552.23 | 6.19 | 35.98 | 60.07 | -0.713 | ||||

| ZjXTH22 | XP_015898303.1 | 295 | 887 | 12 | 24 | LOC107431811 | 25837449 | 25840155 | 34,115.81 | 8.62 | 36.67 | 67.76 | -0.451 | ||||

| ZjXTH23 | XP_015893429.2 | 300 | 903 | 4 | 32 | LOC107427557 | 6965305 | 6966770 | 33,878.08 | 6.95 | 42.65 | 72.5 | -0.288 | ||||

| ZjXTH24 | XP_024928685.3 | 293 | 882 | 4 | 25 | LOC107416347 | 6947614 | 6949140 | 33,775.19 | 9.47 | 36.74 | 68.26 | -0.465 | ||||

| ZjXTH25 | XP_048328992.1 | 311 | 936 | 1 | _ | LOC107412897 | 6046322 | 6048175 | 34,908 | 8.97 | 43.25 | 65.79 | -0.406 | ||||

| ZjXTH26 | XP_015875174.3 | 305 | 918 | 1 | _ | LOC107411968 | 1008911 | 1010755 | 34,241.17 | 4.98 | 43.09 | 67.51 | -0.283 | ||||

| ZjXTH27 | XP_060671181.1 | 288 | 867 | 1 | 26 | LOC107411514 | 982063 | 988879 | 32,731.87 | 5.97 | 34.92 | 74.51 | -0.29 | ||||

| ZjXTH28 | XP_048336175.2 | 300 | 903 | 9 | 32 | LOC125424038 | 23312053 | 23313630 | 34,157.58 | 8.54 | 39.98 | 73.13 | -0.293 | ||||

| ZjXTH29 | XP_048327183.1 | 300 | 903 | 4 | 32 | LOC125421763 | 6952934 | 6954513 | 33,92.92 | 8.54 | 42.4 | 71.5 | -0.305 | ||||

| Gene1 | Gene2 | Identity (%) | Ks | Ka | Ka/Ks | MAY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZjXTH1 | ZjXTH7 | 94.77 | 2.0593 | 1.6380 | 0.79 | 1.68 |

| ZjXTH2 | ZjXTH5 | 68.75 | 2.1000 | 1.8905 | 0.9 | 1.72 |

| ZjXTH4 | ZjXTH6 | 91.54 | 0.6033 | 0.0675 | 0.11 | 4.94 |

| ZjXTH17 | ZjXTH8 | 71.84 | 0.7556 | 0.8956 | 1.18 | 6.19 |

| ZjXTH23 | ZjXTH28 | 93.67 | 0.0545 | 0.0605 | 1.11 | 4.46 |

| ZjXTH12 | ZjXTH29 | 66.9 | 2.4965 | 1.2844 | 0.51 | 2.04 |

| ZjXTH15 | ZjXTH26 | 80.51 | 0.2084 | 0.3212 | 1.54 | 1.7 |

| ZjXTH16 | ZjXTH18 | 86.81 | 0.1081 | 0.1524 | 1.41 | 8.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).