Introduction

The rise of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools such as ChatGPT has created a new turning point in higher education. Around the world, higher education institutions (HEIs) are rethinking how teaching, learning, and assessment can evolve in the presence of such technologies (Apata et al., 2025). ChatGPT, in particular, has drawn significant attention for its ability to generate human-like responses, provide clear explanations, and assist with writing, coding, and analytical reasoning (Chan & Hu, 2023). As these capabilities continue to expand, they are beginning to influence disciplines in unique ways. In engineering education, where creativity, problem solving, and technical precision are essential, ChatGPT offers both new possibilities for innovation and complex challenges that require careful consideration (Munir et al., 2025).

Although these opportunities are promising, their success relies on how students use the tool. Many students view ChatGPT as an accessible resource for understanding difficult material, explaining technical concepts, debugging code, and fostering self-directed learning (Sarwanti et al., 2024). However, its use has also sparked significant debate among educators who are concerned about plagiarism, the decline of independent thinking (Murtiningsih et al., 2024), and the risk of overreliance on automated assistance (Uppal & Hajian, 2024). This tension raises a broader question for educators and policymakers: how can higher education institutions promote innovation and access while preserving academic integrity and authentic learning?

An important part of this conversation involves the role of institutional support. When universities establish clear policies, provide training, and communicate acceptable uses of artificial intelligence tools, students tend to view ChatGPT as a legitimate learning resource rather than as a shortcut or a violation of academic norms. Studies in engineering settings show that faculty involvement and institutional guidance encourage students to develop positive and responsible attitudes toward AI (Amani et al., 2024). Conversely, limited communication or restrictive policies often create uncertainty. Students may hesitate to use AI tools, even for appropriate purposes, if they fear disciplinary consequences or misunderstand what constitutes ethical use (Qu & Wang, 2025).

In addition to institutional support, ethical concerns have become central to conversations about AI adoption. Both faculty and students ask questions about plagiarism, bias, misinformation, and data privacy. These concerns are especially important in engineering education, where accuracy, accountability, and transparency are vital (Williams, 2024). Many students remain unsure when ChatGPT crosses ethical boundaries or compromises originality and fairness (Ahmed, 2024). Researchers highlight that clear institutional policies and ethics-focused teaching can help students navigate these challenges and use AI responsibly (Kovari, 2025).

Aside from institutional and ethical factors, the challenge of student readiness to use GenAI tools remains. Readiness involves confidence in adopting new technologies and the ability to evaluate their outcomes critically. This emphasis on readiness aligns with prior research showing that learner capability and teacher preparation matter for success, with mathematics background and teacher qualification predicting physics outcomes (Apata, 2019). Students who feel supported, well-informed, and technologically capable are more likely to use ChatGPT for meaningful learning rather than as a shortcut (Yang & Jiang, 2025). However, research shows that readiness levels vary significantly among students, depending on their access to resources, digital skills, and the institutional culture toward technology (Chiu, 2024). Enhancing readiness through AI literacy programs can help students adopt a reflective and responsible approach to using these tools (Feldman & Cherry, 2024).

These aspects of institutional support, ethical awareness, and readiness shape students’ intended use of ChatGPT. When students trust their institutions to promote ethical engagement with AI and feel confident and capable of using it, they are more likely to adopt it positively (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024). Conversely, when ethical concerns and lack of support dominate, the intention to use it often declines even among those who see its potential value (Yparrea & Hernández-Rodríguez, 2024).

Considering these factors, this study examines the connections among institutional support, ethical concerns, student readiness, and the planned use of ChatGPT in engineering education. Specifically, it looks at how supportive institutional settings and ethical perceptions affect students’ willingness to use ChatGPT, and how this willingness predicts their intention to incorporate the tool into their academic work. The study also investigates whether readiness acts as a mediator between institutional and ethical influences and students’ adoption intentions. To achieve these goals, our study will address the following research questions:

To what extent do institutional support and ethical concerns predict students’ readiness to use ChatGPT among engineering students?

To what extent do students’ readiness to use ChatGPT predict intended use of ChatGPT among engineering students?

-

Does Student Readiness mediate the relationship between

a) institutional support and intended use among engineering students?

b) ethical concerns and intended use among engineering students?

Methodology

Participants and context

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of Nigerian university students about their experiences with and intentions to use ChatGPT. Data was collected with Qualtrics between September and October 2025. The dataset contained 942 cases from multiple institutions and disciplines.

For this paper, we focused on engineering students because the research questions concern engineering education. We filtered the dataset to respondents who indicated an engineering major, yielding 118 cases. We estimated the structural equation model in Stata using full-information maximum likelihood to handle missing values. Fifteen cases had no observed responses on the modeled indicators and were excluded, resulting in an analytic sample of 103.

Instrument development and pilot testing

We developed a multi-section questionnaire to assess perceived challenges of ChatGPT, institutional support for AI integration, student readiness, intended use of ChatGPT, and related motivational and academic variables. Items were written in English and rated on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Before the main data collection, we conducted two pilot studies in Nigeria. In Pilot 1 (N = 44), we administered an initial 60-item instrument and used exploratory factor analysis and item statistics to identify poorly performing items and refine wording. Based on these results, we revised and expanded the pool to 75 items. In Pilot 2 (N = 91), we administered the refined instrument and again evaluated reliability and factor structure. Items with weak loadings, cross loadings, or low item total correlations were removed. The final survey for the main study contained 65 items.

In Pilot 2, the subscales used in this paper showed good internal consistency: Ethical Concerns (4 items, α = .79), Institutional Support (4 items, α = .83), Student Readiness (4 items, α = .92), and Adoption Likelihood or Intended Use (4 items, α = .89).

Measures for the present study

For the SEM reported here, we modeled four latent constructs, each measured with the Pilot-2–refined items:

Institutional Support (Support). Three items measured students' perceptions of whether their institution encourages the use of ChatGPT, provides clear guidance on when it is allowed, and has policies that support its adoption.

Ethical Concerns (Ethics). Three items assessed concerns that ChatGPT might threaten privacy, foster dependence on technology, or reduce meaningful human interaction in education.

Student Readiness (Readiness). Four items measured students' interest in ChatGPT, whether they intended to use it for coursework, their comfort using it, and whether they knew how to access it.

Intended Use of ChatGPT (Use). Four items assessed students' likelihood of adopting ChatGPT for academic tasks, their openness to using it in courses, their plans to use it in the near future, and their expectations for using it in upcoming coursework.

Higher scores on all scales indicate greater institutional support, stronger ethical concerns, higher readiness, or increased intended use. Internal consistency estimates for the engineering subset are reported in

Table 2.

Procedure and ethics

We distributed the Qualtrics link through course instructors and student WhatsApp groups. The first page of the survey described the purpose of the study, emphasized that participation was voluntary, and obtained informed consent before any items appeared. Participants could skip any question and could exit the survey at any time without penalty.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at Olabisi Onabanjo University (Nigeria) and Texas A&M University (United States). All procedures followed institutional guidelines for research with human participants.

Data analysis

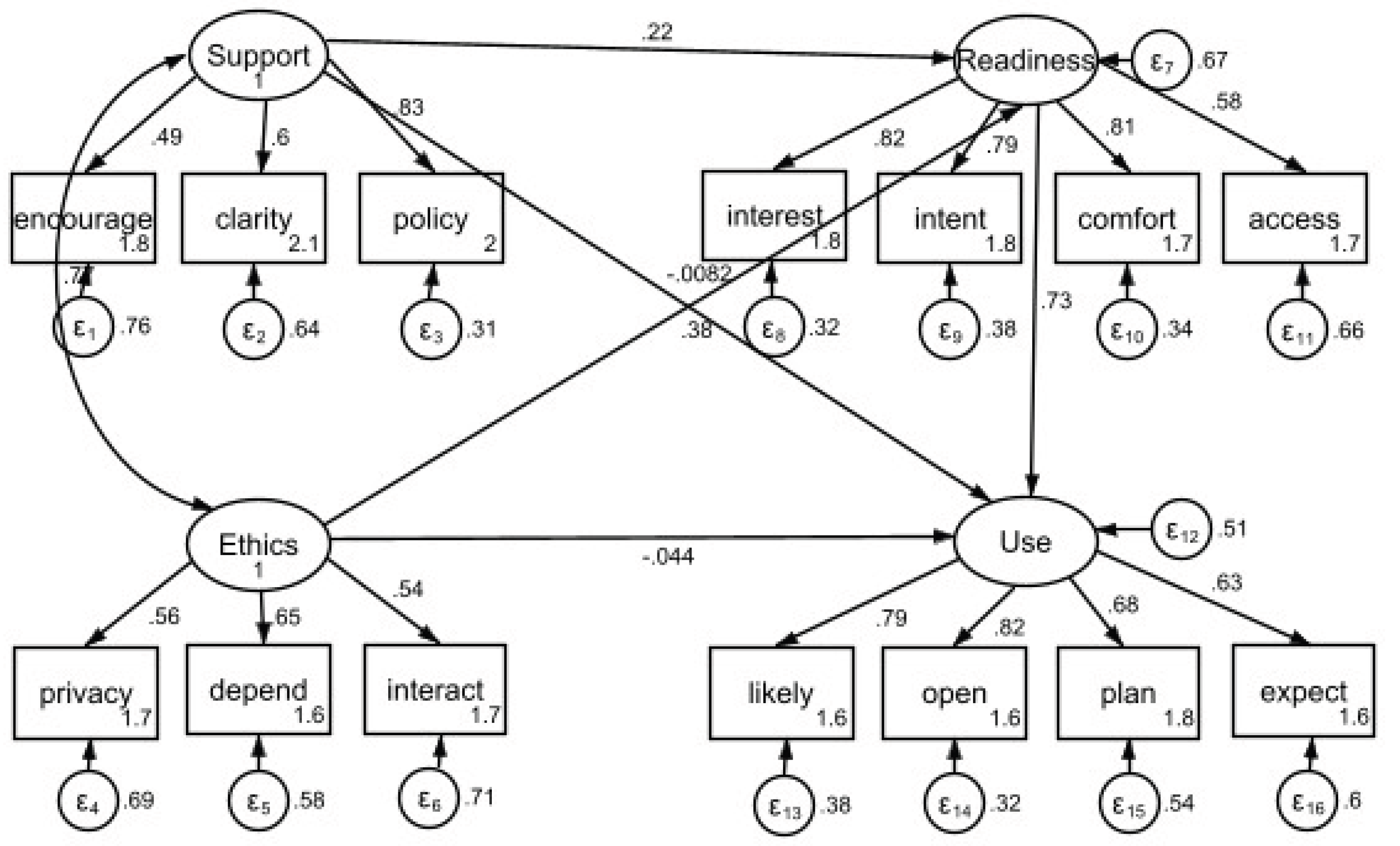

We used SEM in Stata to test the hypothesized relationships among institutional support, ethical concerns, students’ readiness to use ChatGPT, and their intention to use the tool. Items were treated as continuous indicators. We first estimated a confirmatory measurement model with four correlated latent factors. We then specified a structural model in which Support and Ethics predicted Readiness, and Readiness predicted Intended Use. Direct paths from support and ethics to intended use were included to test mediation. Support and ethics were allowed to covary.

Models were estimated using maximum likelihood with missing values (method mlmv), which implements FIML under the assumption that data are missing at random. Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square test, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with 90 percent confidence interval, and pclose, the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Standardized factor loadings and path coefficients are reported in

Table 3 and

Table 5. Indirect and total effects were obtained with the Stata estat teffects command and are summarized in

Table 6.

Results

Preliminary analyses

We analyzed data from a larger Qualtrics survey of Nigerian university students. When we downloaded the file on October 18, 2025, data collection was still in progress. The full dataset contained N = 942 cases. For this paper, we filtered engineering students (n = 118). We used full-information maximum likelihood in Stata to handle item nonresponse. Stata removed 15 cases with no observed responses on the modeled indicators, yielding an analytic sample size of 103.

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all indicators.

Table 2 reports internal consistency for each construct.

Table 3 lists standardized factor loadings from the measurement model.

Table 4 summarizes the global model fit. Support and Ethics were strongly correlated,

r = .77,

p < .001.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for indicators used in the SEM.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for indicators used in the SEM.

| Construct |

Indicator |

N |

M |

SD |

| Institutional Support |

encourage |

91 |

2.27 |

1.26 |

| |

clarity |

91 |

2.26 |

1.09 |

| |

policy |

91 |

2.64 |

1.34 |

| Ethical Concerns |

privacy |

103 |

2.15 |

1.29 |

| |

depend |

103 |

2.15 |

1.34 |

| |

interact |

103 |

2.41 |

1.40 |

| Student Readiness |

interest |

91 |

2.65 |

1.50 |

| |

intent |

91 |

2.56 |

1.45 |

| |

comfort |

91 |

2.49 |

1.49 |

| |

access |

91 |

2.40 |

1.44 |

| Intended Use |

likely |

87 |

2.29 |

1.45 |

| |

open |

87 |

2.37 |

1.46 |

| |

plan |

87 |

2.62 |

1.45 |

| |

expect |

87 |

2.26 |

1.46 |

Table 2.

Internal consistency by construct.

Table 2.

Internal consistency by construct.

| Construct |

Items |

A |

| Institutional Support |

3 |

.67 |

| Ethical Concerns |

3 |

.60 |

| Student Readiness |

4 |

.83 |

| Intended Use |

4 |

.82 |

Table 3.

Standardized factor loadings.

Table 3.

Standardized factor loadings.

| Construct |

Indicator |

Loading (β) |

SE |

p |

| Institutional Support |

encourage |

.49 |

.11 |

< .001 |

| |

clarity |

.60 |

.09 |

< .001 |

| |

policy |

.83 |

.08 |

< .001 |

| Ethical Concerns |

privacy |

.56 |

.09 |

< .001 |

| |

depend |

.65 |

.09 |

< .001 |

| |

interact |

.54 |

.10 |

< .001 |

| Student Readiness |

interest |

.82 |

.05 |

< .001 |

| |

intent |

.79 |

.05 |

< .001 |

| |

comfort |

.81 |

.05 |

< .001 |

| |

access |

.58 |

.08 |

< .001 |

| Intended Use |

likely |

.79 |

.06 |

< .001 |

| |

Open |

.82 |

.05 |

< .001 |

| |

Plan |

.68 |

.07 |

< .001 |

| |

Expect |

.63 |

.08 |

< .001 |

Table 4.

Overall model fit indices.

Table 4.

Overall model fit indices.

| χ² |

Df |

p |

RMSEA |

95% CI |

pclose |

CFI |

TLI |

| 116.48 |

71 |

.001 |

.079 |

[.052, .105] |

.039 |

.898 |

.869 |

Research Question 1

Do Institutional Support and Ethical Concerns predict Student Readiness among engineering students

We tested whether institutional support and ethical concerns predict student readiness to use ChatGPT. Neither path was statistically significant. Institutional support to students’ readiness was β = .223, SE = .275, z = 0.81,

p = .419, 95% CI [−.317, .763]. The path from ethical concern to students’ readiness was moderate in size but not significant, standardized

β = .385,

SE = .287,

z = 1.34,

p = .181, 95% CI [−.178, .948]. Thus, in this sample institutional support and students’ ethical concern did not account for meaningful variation in students’ readiness to use ChatGPT once modeled together. The latent R² for students’ readiness was approximately .33, indicating that most of its variance remained unexplained by institutional support and students’ ethical concern (see

Table 5). See

Figure 1 for standardized paths.

Research Question 2

Does students’ readiness to use ChatGPT predict their intention to use ChatGPT among engineering students

Yes. Students’ readiness to use ChatGPT showed a strong positive association with Intended Use, β = .731, SE = .123, z = 5.93, p < .001, 95% CI [.489, .972] (see

Table 5). The direct paths from institutional support to intended use and from ethical concern to intended use were not significant, β = −.008, p = .973 and β = −.044, p = .881, respectively. The structural model explained about half of the variance in intended use (latent R² = .495). See

Table 5 for the standardized direct paths.

Table 5.

Standardized structural paths and model R².

Table 5.

Standardized structural paths and model R².

| Predictor |

Outcome |

Β |

SE |

z |

p |

95 % CI |

| Institutional Support |

Student Readiness |

.223 |

.275 |

0.81 |

.419 |

[−.317, .763] |

| Ethical Concerns |

Student Readiness |

.385 |

.287 |

1.34 |

.181 |

[−.178, .948] |

| Student Readiness |

Intended Use |

.731 |

.123 |

5.93 |

< .001 |

[.489, .972] |

| Institutional Support |

Intended Use |

−.008 |

.247 |

−0.03 |

.973 |

[−.492, .475] |

| Ethical Concerns |

Intended Use |

−.044 |

.295 |

−0.15 |

.881 |

[−.621, .533] |

| R² |

Student Readiness |

.33 |

|

|

|

|

| R² |

Intended Use |

.49 |

|

|

|

|

Research Question 3

Does students’ readiness to use ChatGPT mediate the relationship between institutional support and their intended use, and between ethical concerns and intended use

We evaluated indirect and total effects. Indirect effects through Readiness were not statistically significant for either predictor. The Support → Readiness → Use indirect effect was

b = .300,

SE = .379,

z = 0.79,

p = .428. The Ethics → Readiness → Use indirect effect was

b = .446,

SE = .376,

z = 1.19,

p = .235. Total effects on Use were also not significant for Support (

b = .285,

p = .606) or Ethics (

b = .377,

p = .466). For interpretation, the corresponding standardized indirects are approximately the product of standardized paths: Support → Readiness → Use ≈ .22 × .73 = .16; Ethics → Readiness → Use ≈ .38 × .73 = .28. See

Table 6 for unstandardized estimates and the reporting note.

We also examined the direct paths from Support and Ethics to Intended Use while controlling for Readiness; both were not significant (Support → Use β = −.008, p = .973; Ethics → Use β = −.044, p = .881; see

Table 5), so there is no evidence of partial mediation. Combined with the non-significant paths from Support and Ethics to Readiness (β = .223, p = .419; β = .385, p = .181), the indirect effects are not supported.

Table 6.

Indirect and total effects for Intended Use.

Table 6.

Indirect and total effects for Intended Use.

| Effect |

Path |

B |

SE |

Z |

p |

β (std.) |

| Indirect |

Support → Readiness → Use |

.300 |

.379 |

0.79 |

.428 |

.163 |

| Indirect |

Ethics → Readiness → Use |

.446 |

.376 |

1.19 |

.235 |

.281 |

| Total |

Support → Use |

.285 |

.553 |

0.52 |

.606 |

.155 |

| Total |

Ethics → Use |

.377 |

.516 |

0.73 |

.466 |

.237 |

Discussion

Engineering education is currently at an inflection point, where the integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT is transforming how students learn, solve problems, and engage with knowledge. This transformation reflects both global trends and local realities in contexts such as Nigeria, where institutions face unique infrastructural, ethical, and pedagogical challenges. The findings of this study show that among institutional support, ethical concerns, and student readiness to use ChatGPT, only readiness significantly predicts the intended use of ChatGPT among engineering students. This outcome reiterates an important point where student capability and confidence have become the driving forces of educational change.

This study shows that students’ readiness to use ChatGPT significantly predict their ChatGPT adoption. This finding is consistent with Kostas et al. (2025) which reveal that students who are technically proficient and psychologically prepared are more likely to use AI tools meaningfully. Similarly, Agyare et al. (2025) found that perceived ease of use and social influence strongly predict behavioral intention to use ChatGPT across countries. In engineering education, where analytical precision and problem-solving are essential, readiness to use GenAI tools bridges curiosity and productive engagement. In Nigeria, this dominance of readiness over institutional and ethical factors reflects persistent infrastructural and policy limitations. Although universities increasingly acknowledge GenAI’s potential, adoption remains hindered by weak institutional frameworks, limited infrastructure, and scarce training opportunities (Suleiman et al., 2025).

The limited effect of institutional support contrasts with findings from contexts where university policies and faculty engagement have accelerated GenAI adoption. For example, Ayanwale et al. (2025) showed that in-service Nigerian teachers’ behavioral intentions to use ChatGPT improved significantly after structured training that built trust and reduced technology anxiety. This suggests that institutional influence can become more significant when universities provide hands-on professional development and policy frameworks. Thus, the non-significance of institutional support in the present study should not be interpreted as its irrelevance but rather as an indication of underdeveloped institutional ecosystems for AI integration in Nigerian engineering education.

Ethical concerns also showed no significant effect on readiness or intended use of engineering students in Nigeria, which is consistent with recent literature suggesting that ethical awareness alone rarely deters AI adoption. Yau & Mohammed (2025) found that Nigerian students often recognize plagiarism and bias as potential risks of generative AI but continue to engage with ChatGPT for its learning benefits. Similarly, Kovari (2025) emphasized that while ethical apprehensions are widespread, their influence on behavior is limited unless institutions actively reinforce ethical engagement through assessment design and dialogue. The current findings suggest that engineering students’ ethical engagement with ChatGPT remains primarily individual rather than institutionally guided, highlighting the need for structured interventions that connect AI ethics to engineering design and professional responsibility.

The relationship between students’ readiness to use ChatGPT and ethical concern also resonates with global concerns about the uneven distribution of AI literacy. The study by Kostas et al. (2025) found that students with higher ICT competence are better equipped to manage ethical challenges and assess AI reliability. In resource-constrained environments like Nigeria, however, limited access to digital tools can widen these gaps. Students’ readiness to use AI tool thus becomes not only a cognitive state but a marker of technological equity. Al-Tayar (2025) made a similar observation in Yemen, noting that socioeconomic barriers moderated the effectiveness of GenAI use among engineering students, despite high levels of awareness. These parallels suggest that developing nations face similar inflection points where enthusiasm for AI integration must be matched by systemic investments in infrastructure, training, and ethics education.

These findings illustrate a critical juncture for Nigerian engineering education. The rapid emergence of GenAI represents technological disruption and an opportunity to redefine pedagogical priorities. The evidence indicates that the transformative potential of GenAI depends less on the availability of policies and more on cultivating student capability, confidence, and curiosity. This reaffirms that educational innovation is most sustainable when human readiness keeps pace with technological advancement. However, the current imbalance where readiness outpaces institutional and ethical support signals that Nigeria’s higher education sector stands at a crossroads between innovation and regulation.

Conclusion

ChatGPT is becoming an important tool in engineering education, but its use raises questions about institutional support, ethical concerns, and student readiness. In this study, we examined how supportive institutional environments and ethical perceptions relate to students’ readiness to use ChatGPT and how readiness predicts their intention to integrate the tool into their academic work. Among the three factors, only students’ readiness to use ChatGPT significantly predicted their intention to use. Institutional support and ethical concerns did not show significant direct or mediated effects on intention to use ChatGPT in this sample of Nigerian engineering students.

One interpretation is that current institutional frameworks and ethics discussions around GenAI in Nigerian engineering programs are still developing, while many students are already exploring ChatGPT on their own. The findings suggest that building students’ capability, confidence, and interest in using GenAI tools is central for adoption, but that such readiness should be guided by clear policies and course-level practices that promote ethical use.

A major limitation of the study is the modest, non-representative sample of engineering students, which limits generalizability. The cross-sectional design also does not allow causal conclusions. Future research should draw on larger and more diverse samples, track changes in readiness and use over time, and examine how specific forms of institutional support and ethics instruction shape students’ engagement with GenAI in engineering education. Future studies should also examine GenAI adoption with explicit attention to gender, socioeconomic status, and disability to ensure that AI-supported learning does not widen existing gaps.

References

- Acosta-Enriquez, B.G.; Arbulú Ballesteros, M.A.; Arbulu Perez Vargas, C.G.; Orellana Ulloa, M.N.; Gutiérrez Ulloa, C.R.; Pizarro Romero, J.M.; Gutiérrez Jaramillo, N.D.; Cuenca Orellana, H.U.; Ayala Anzoátegui, D.X.; López Roca, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceived ethics regarding the use of ChatGPT among Generation Z university students. International Journal for Educational Integrity 2024, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyare, B.; Asare, J.; Kraishan, A.; Nkrumah, I.; Adjekum, D.K. A cross-national assessment of artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot user perceptions in collegiate physics education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2025, 8, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R. Exploring ChatGPT usage in higher education: Patterns, perceptions, and ethical implications among university students. Journal of Digital Learning and Distance Education 2024, 3, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tayar, B.; Noman, M.A.; Amrani, M.A. Generative AI and engineering education: Measuring academic performance amidst socioeconomic challenges in Yemen. Journal of Science and Technology 2025, 30, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, S.; White, L.L.A.; Balart, T.; Shryock, K.J.; Watson, K.L. WIP: Faculty perceptions of ChatGPT: A survey in engineering education. In 2024 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE); 2024, October, IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Apata, O.E. Predictive validity of school and student factors on secondary school students’ academic performance in physics. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) 2019, 9, 34–42. Available online: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jrme/papers/Vol-9%20Issue-5/Series-3/B0905033442.pdf.

- Apata, O.E.; Ajose, S.T.; Apata, B.O.; Olaitan, G.I.; Oyewole, P.O.; Ogunwale, O.M.; Oladipo, E.T.; Oyeniran, D.O.; Awoyemi, I.D.; Ajobiewe, J.O.; Ajamobe, J.O.; Appiah, I.; Fakhrou, A.A.; Feyijimi, T. Artificial intelligence in higher education: A systematic review of contributions to SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequality). International Journal of Educational Management. 2025. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/ijem/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/IJEM-12-2024-0856/1272029/Artificial-intelligence-in-higher-education-a.

- Ayanwale, M.A.; Adelana, O.P.; Bamiro, N.B.; Olatunbosun, S.O.; Idowu, K.O.; Adewale, K.A. Large language models and GenAI in education: Insights from Nigerian in-service teachers through a hybrid ANN–PLS–SEM approach. F1000Research 2025, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.Y.; Hu, W. Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.F. Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2024, 6, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, U.; Cherry, C. Equipping first-year engineering students with artificial intelligence literacy (AI-L): Implementation, assessment, and impact. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. ASEE, 2024, June. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Yparrea, N.; Hernández-Rodríguez, F. Unveiling generative AI in higher education: Insights from engineering students and professors. 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostas, A.; Paraschou, V.; Spanos, D.; Tzortzoglou, F.; Sofos, A. AI and ChatGPT in higher education: Greek students’ perceived practices, benefits, and challenges. Education Sciences 2025, 15, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovari, A. Ethical use of ChatGPT in education: Best practices to combat AI-induced plagiarism. Frontiers in Education 2024, 9, 1465703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovari, A. Ethical use of ChatGPT in education: Best practices to combat AI induced plagiarism. Frontiers in Education 2025, 9, 1465703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.T.; Li, B.; Carter, S.; Hussain, S. Engineering education’s Odyssey with ChatGPT: Opportunities, challenges, and theoretical foundations. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 2025, 53, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtiningsih, S.; Sujito, A.; Soe, K.K. Challenges of using ChatGPT in education: A digital pedagogy analysis. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, J. The impact of AI guilt on students’ use of ChatGPT for academic tasks: Examining disciplinary differences. Journal of Academic Ethics 2025, 23, 2087–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwanti, S.; Sariasih, Y.; Rahmatika, L.; Islam, M.M.; Riantina, E.M. Are they literate on ChatGPT? University language students’ perceptions, benefits and challenges in higher education learning. Online Learning 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, K.; Hajian, S. Students’ perceptions of ChatGPT in higher education: A study of academic enhancement, procrastination, and ethical concerns. European Journal of Educational Research 2025, 14, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.T. The ethical implications of using generative chatbots in higher education. Frontiers in Education 2024, 8, 1331607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jiang, S.; Li, B.; Herman, K.; Luo, T.; Chappell Moots, S.; Lovett, N. Analysing nontraditional students' ChatGPT interaction, engagement, self-efficacy and performance: A mixed-methods approach. British Journal of Educational Technology 2025, 56, 1973–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, M.; Mohammed, A. AI-Assisted Writing and Academic Literacy: Investigating the Dual Impact of Language Models on Writing Proficiency and Ethical Concerns in Nigerian Higher Education. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 2025, 13, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).