1. Introduction

In a rapidly evolving era of digital transformation, generative Artificial Intelligence (genAI) tools, exemplified by ChatGPT, are expected to reshape education [

1,

2]. Universities, which are the longstanding pillars of human intellect are now at a critical juncture, grappling with the dualities of genAI innovation and disruption [

3,

4,

5]. For university educators, the shift brought about by genAI evokes both the allure of unprecedented opportunities and the disquieting specter of obsolescence [

6,

7]. Recent reports highlighted the growing uncertainty among university educators regarding genAI adoption, which may carry significant implications for higher education [

8,

9]. This uncertainty is rooted not merely in technological unfamiliarity and perceived risks but in the very identity and purpose of education itself [

10,

11,

12].

A primary concern among educators is the perceived threat that genAI poses to their professional roles [

13,

14]. In higher education, genAI models have the ability to generate coherent course plans, automate students’ assessments, and simulate dialogues and feedback [

2,

8,

15,

16]. However, these advantages of genAI raise unsettling concerns. There is growing apprehension that the university educator—traditionally seen as the cornerstone of intellectual inquiry—may be rendered superfluous. Budget-conscious institutions might increasingly view genAI as a cost-effective substitute for human expertise. While these fears are understandable, they risk reducing genAI to a narrative of displacement, overlooking its potential for collaborative synergy alongside human educators [

17,

18].

The second issue represents a deeper existential challenge to university educators, namely the preservation of originality and intellectual integrity in the genAI era [

19,

20,

21]. The core of academia, built upon the pillars of critical thinking and innovation, faces a new test. GenAI tools with their remarkable ability to generate text, images, and videos, challenge the traditional notions of authorship and creativity [

22,

23,

24]. In this context, critical concerns emerge. The presence of genAI in classrooms may erode the authenticity of student work, while growing reliance on these tools could diminish the intellectual contributions of educators themselves. These issues strike at the core of academic purpose, demanding a redefinition of how originality is cultivated in an era of ubiquitous genAI [

3,

17,

25].

In higher education, resistance to genAI adoption is often reinforced by tradition—a defining trait of institutions that value historical continuity [

26,

27]. Thus, university educators —particularly those deeply embedded in established practices— find the leap to integrating novel technologies including genAI in their routine practice a daunting and even threatening task [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Technological readiness among university educators, though critical, remains far from universal [

32,

33,

34]. Yet, history demonstrates that resistance to innovation seldom delays its ultimate course [

35,

36]. From personal computers and internet search engines to smartphones and digital classrooms, higher education has consistently, albeit reluctantly adapted to technological change [

37,

38,

39]. For educators and institutions ready to embrace the genAI transformation, the opportunities would be both significant and far-reaching as recently highlighted by Kurtz et al. and Dempere et al. [

40,

41].

Building on the aforementioned points, genAI would inevitably present higher education with transformative tools that challenges traditional pedagogical boundaries and motivate the students to engage in the learning process [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Far beyond novelty, genAI has the potential to revolutionize teaching, learning, and assessment by automating routine tasks, personalizing education, and enabling innovative instructional methods [

7,

46,

47]. Yet, genAI adoption in higher education remains controversial [

48,

49]. Concerns about academic integrity, faculty readiness, and equitable access highlight the complexity of this transition [

50,

51]. Considering the current evidence pointing to widespread adoption of genAI in higher education, particularly among university students, the key question is not whether genAI will reshape the educational landscape, but how effectively universities can successfully integrate it into its policies [

52,

53,

54,

55]. By drawing on established frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), stakeholders in higher education can anticipate barriers and develop strategies to ensure genAI complements—rather than replaces—the essential role of human educators [

56,

57].

The rapid rise of genAI tools in higher education, particularly ChatGPT, has been well-documented across multiple studies. By mid-2023, approximately one-quarter of surveyed Arab students in a multinational study reported actively engaging with ChatGPT [

58]. This adoption was driven by determinants such as perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, positive attitudes toward technology, social influence, and minimal anxiety or perceived risks [

58]. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), similar patterns of genAI adoption have emerged, reflecting an emerging norm among university students in Arab countries [

59]. Globally, this trend has been corroborated by a multinational study conducted across Brazil, India, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States [

60]. The widespread use of ChatGPT for university assignments, as reported in several recent studies, indicates a global shift in student behavior that transcends cultural and geographic boundaries [

52,

61,

62].

The growing adoption of genAI by students and educators in higher education calls for rigorous research to assess its impact and inform responsible, ethical, and effective integration [

63,

64,

65]. GenAI implications extend beyond technological novelty, challenging the very foundations of higher education—learning outcomes, academic integrity, and pedagogical frameworks [

8,

66]. Thus, the current study aimed to evaluate university educators’ attitudes toward genAI. This study employed a TAM-based approach recognizing that genAI adoption is shaped by Perceived Usefulness and Effectiveness [

67,

68,

69]. This study also sought to confirm the validity of the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT tool, which was specifically developed to assess educators’ perspectives on ChatGPT [

70]. Conducted in a multinational context, the study aimed to generate broad, generalizable insights to inform higher education policy in both the Arab region and globally.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framework

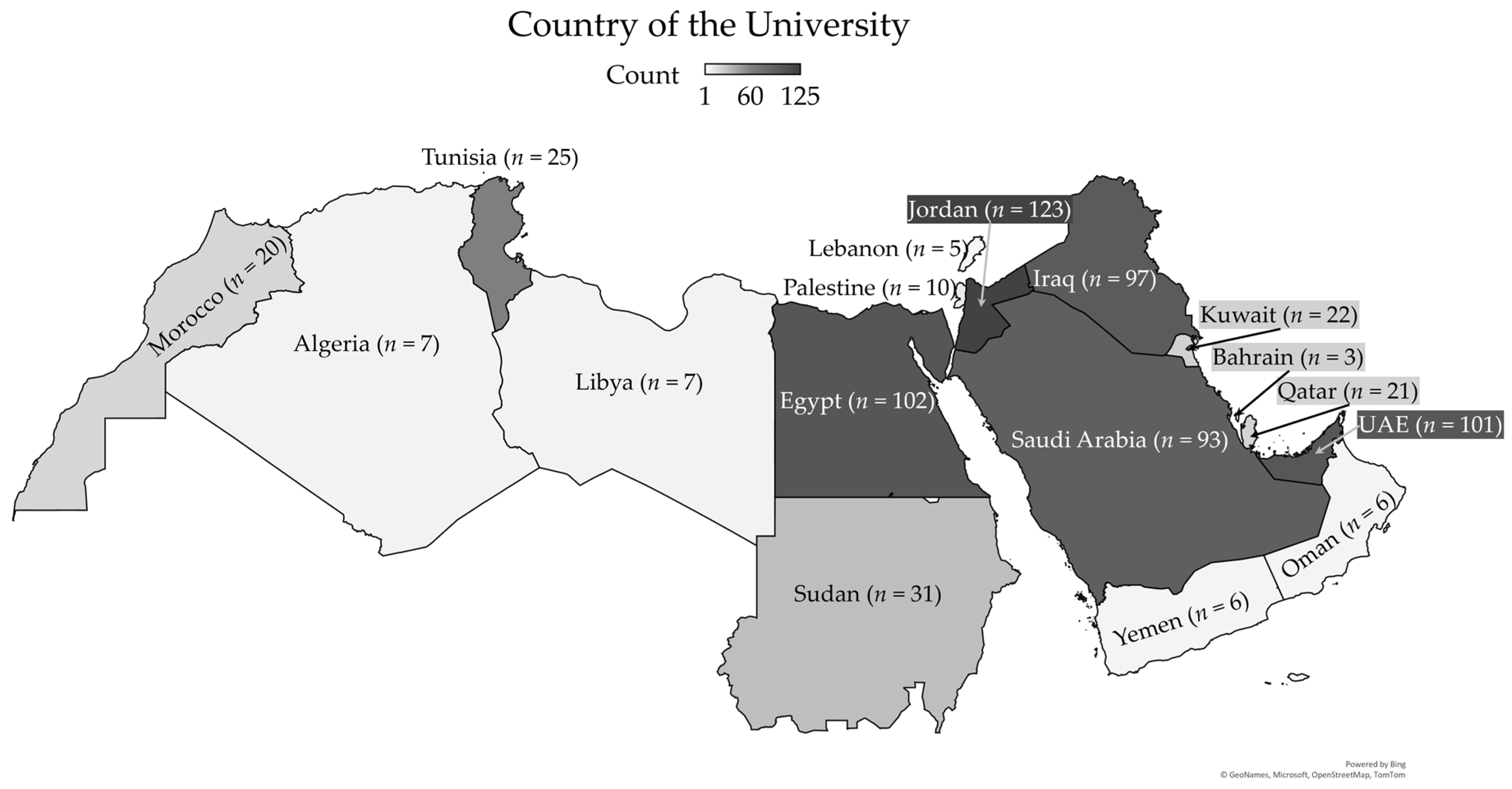

This cross-sectional study was conducted from November to December 2024 using the previously validated Ed-TAME-ChatGPT tool [

70]. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed through convenience sampling to facilitate rapid data collection. The survey targeted academics in Arab countries, specifically those residing in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

The study was theoretically grounded in the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT framework, an education-adapted extension of the TAM, which categorizes predictors of genAI attitude into three interrelated domains: positive enablers, perceived barriers, and contextual traits, with attitudinal outcomes measured as Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness [

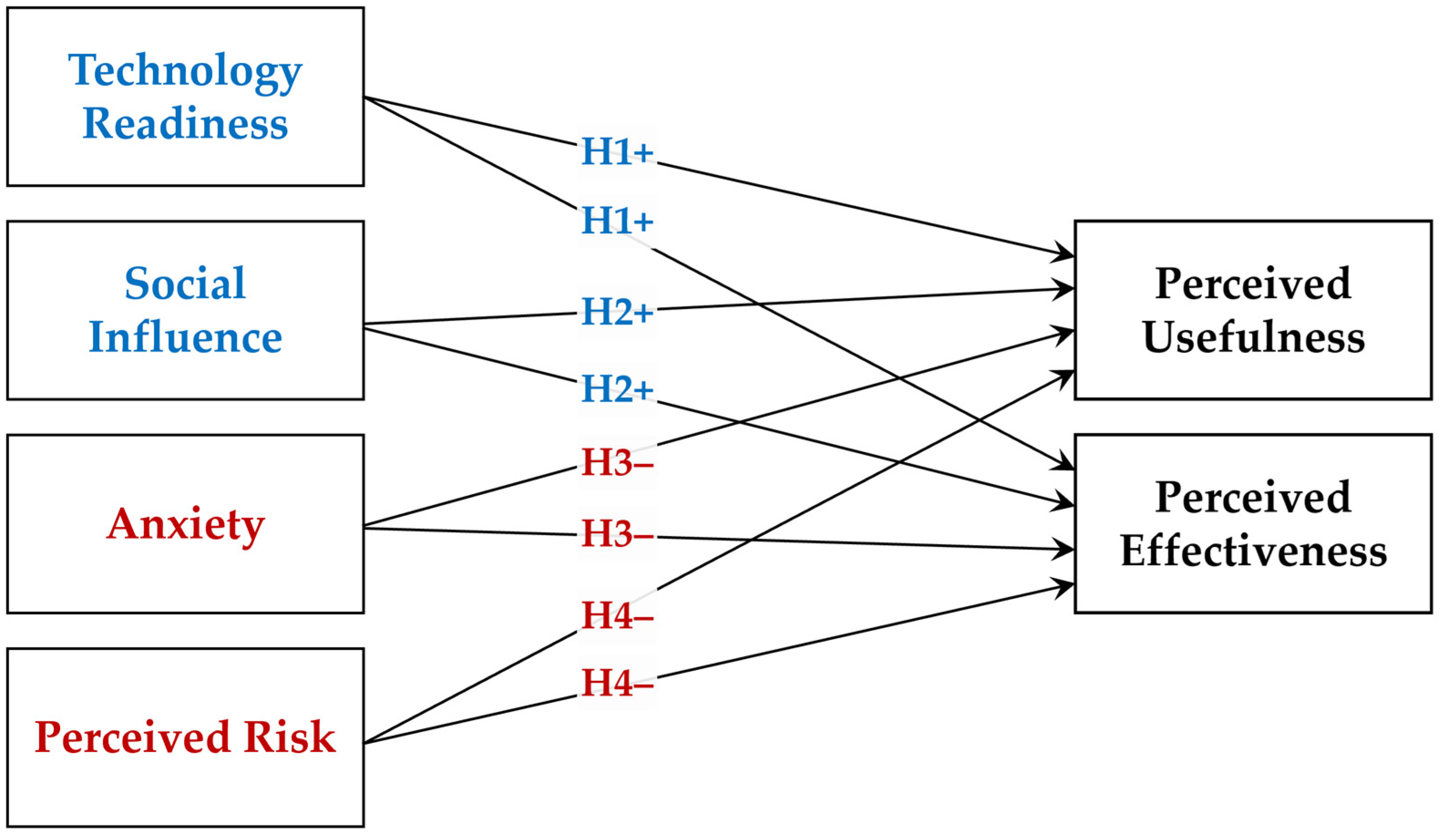

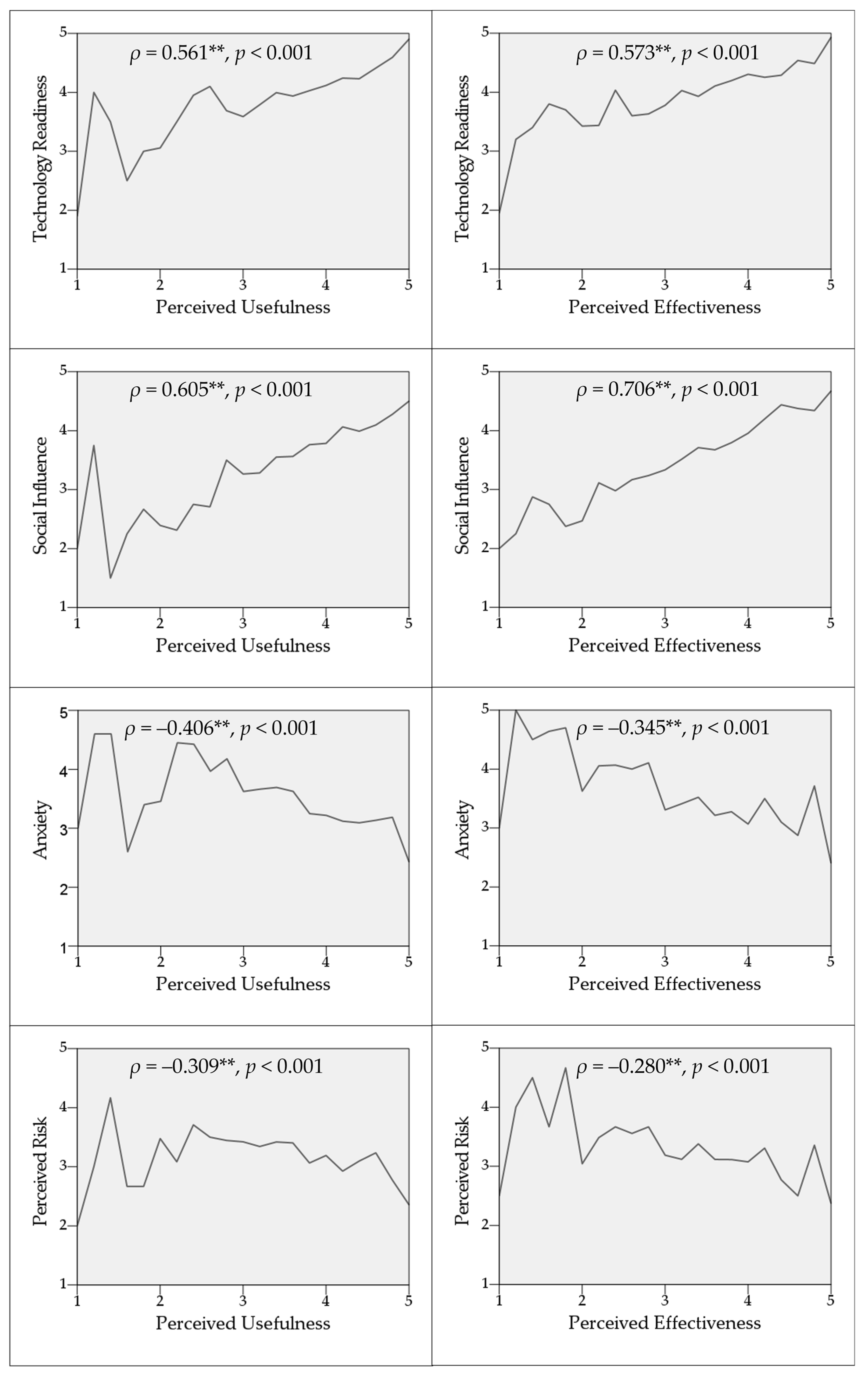

70]. The framework posits that educators’ attitudes—specifically Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness of genAI—are influenced by four key factors: Technology Readiness, Social Influence, Anxiety, and Perceived Risks.

Guided by Ed-TAME-ChatGPT instrument, the following hypotheses were tested (

Figure 1):

H1: Technology Readiness positively predicts Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness.

H2: Social Influence positively predicts Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness.

H3: Anxiety negatively predict Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness.

H4: Perceived Risks negatively predict Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness.

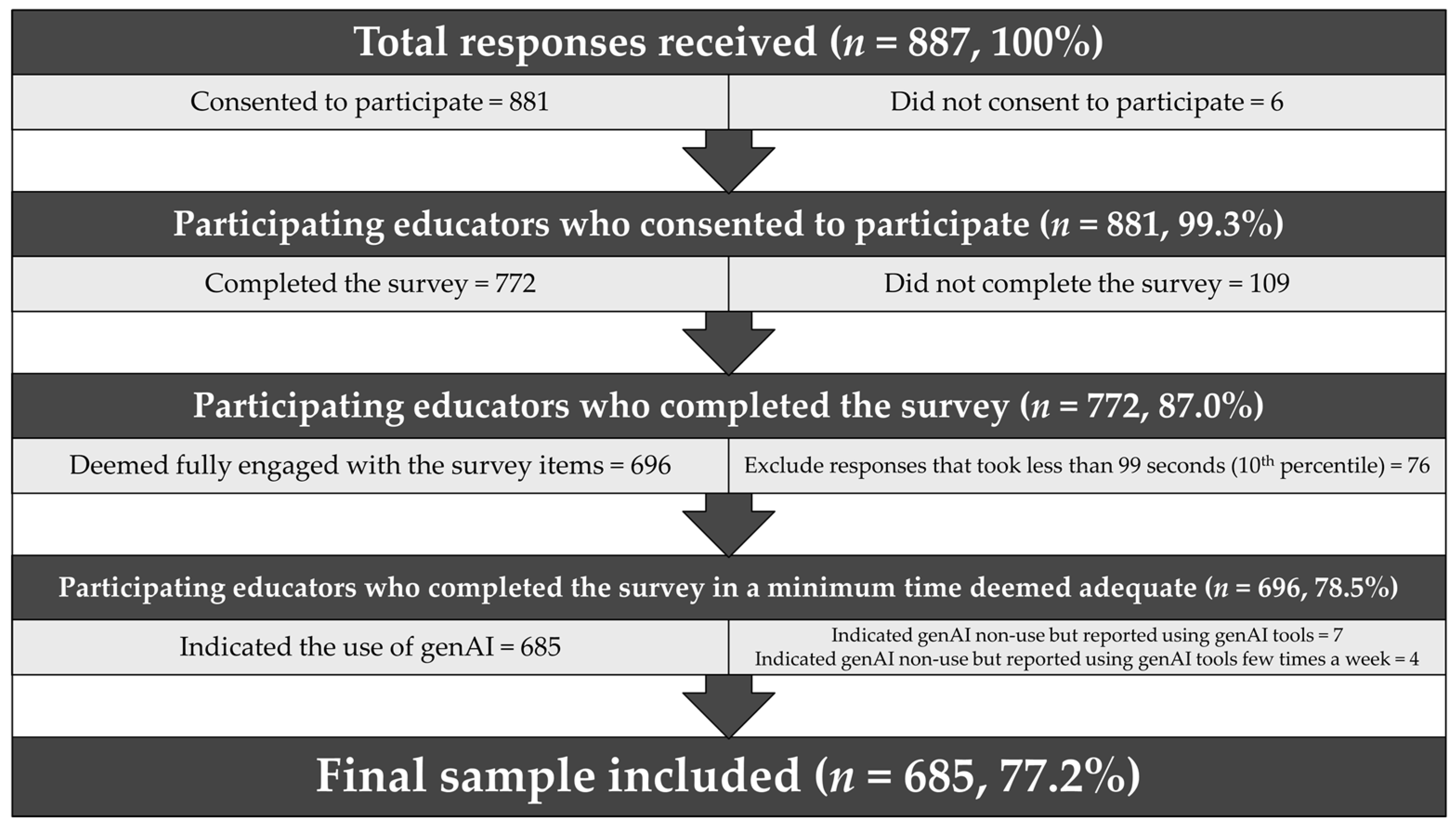

2.2. Recruitment of Participants, Sample Size Determination, and Ethical Approval

To maximize outreach, we utilized our professional networks and social media platforms, including LinkedIn, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Telegram for survey link distribution. A snowball sampling approach was employed, encouraging initial participants to distribute the survey link further within their networks, thereby expanding the respondent pool [

71]. The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc., San Mateo, California, USA), with no incentives provided for participation and it was provided concurrently in Arabic and English. For quality control (QC) purposes, the survey access was limited to a single response per IP address, and the duration of survey completion was noted.

Our study design adhered to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) guidelines which suggest a minimum of 200 participants for sufficient statistical power [

72,

73]. Given the multinational scope of the study and the variability in educational contexts, a larger target sample of over 500 educators was pursued to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

The survey began with an electronic informed consent form, ensuring participants’ understanding of the study objectives and explicit agreement to participate. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Deanship of Scientific Research at Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman, Jordan, granted on 12 November 2024. IP addresses were removed from the dataset following data collection to maintain participant confidentiality during analysis.

2.3. Introductory Section of the Survey and Demographic Variables’ Assessment

The survey began with an introductory section outlining the study objectives and the following eligibility criteria: (1) respondents understood that their answers would remain confidential and their identities anonymous, (2) participants confirmed they were faculty members currently employed at an Arab university, and (3) they voluntarily agreed to participate in the research by completing the questionnaire. Following this introduction, participants were presented with a mandatory electronic informed consent form, which was required before proceeding to the demographic assessment.

Demographic questions assessed participants’ characteristics, starting with their age group (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, or 55+ years) and sex (male or female). Nationality was selected from a comprehensive list, including Algerian, Bahraini, Egyptian, Emirati, Iraqi, Jordanian, Kuwaiti, Lebanese, Libyan, Moroccan, Omani, Palestinian, Qatari, Saudi, Sudanese, Tunisian, Yemeni, or "Others" for unlisted nationalities. Participants also identified the country where their university is located, using the same list of options provided for nationality. The countries were later grouped into five categories: Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE); Levant and Iraq (Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine); Egypt and Sudan; the Maghreb (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia); and Others (Yemen and Others).

Further questions categorized faculty members by discipline (Humanities, Health Sciences, or Scientific disciplines) and university type (Public or Private). Participants indicated their highest academic qualification (Bachelor’s degree, Master’s or specialization degree, or PhD/doctoral/fellowship degree) and specified whether it was obtained from an Arab or non-Arab country. Lastly, participants were asked to report their current academic rank (Teaching Assistant, Lecturer, Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, or Professor).

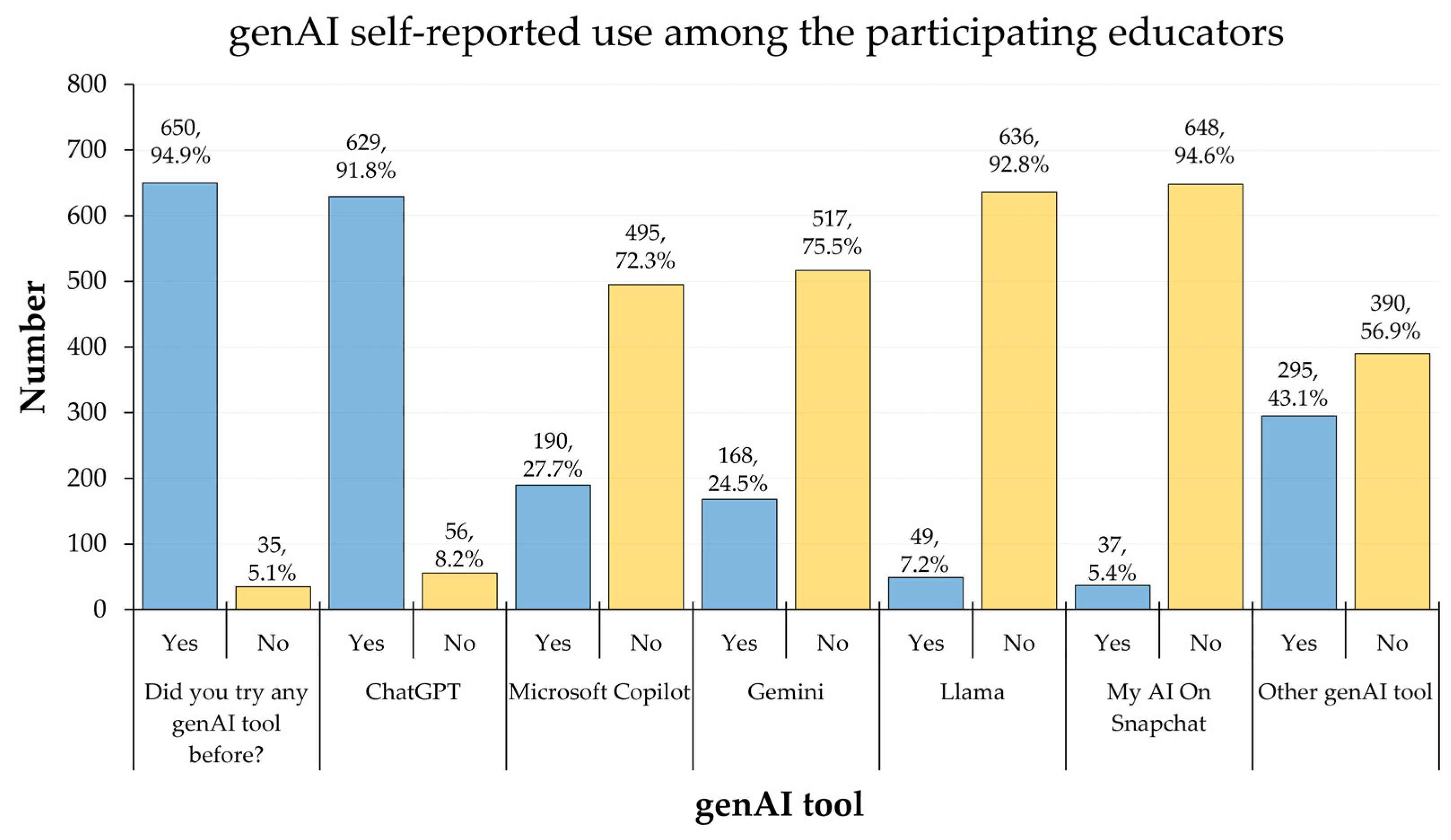

2.4. Assessment of genAI Use, Frequency of Use, and Self-Rated Competency

Participants’ experiences with genAI were assessed through a structured sequence of questions. Initially, respondents were asked whether they had ever used any genAI tool (Yes/No). If they indicated previous genAI use, they were further asked to specify whether they had used ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot, Gemini, Llama, My AI on Snapchat, or other genAI tools (Yes/No for each). A composite genAI use score was calculated by summing affirmative responses across these tools, with each "Yes" response contributing 1 point and each "No" contributing 0.

Frequency of genAI use was measured by asking, "How often do you use generative AI tools?" with response options categorized as daily, a few times a week, weekly, or less than weekly. To assess self-rated genAI competency, the participants were asked to rate their proficiency with genAI tools on a four-point scale: very competent, competent, somewhat competent, or not competent. Self-rated genAI competency was dichotomized into competent/very competent versus somewhat competent/not competent, while frequency of genAI use was categorized as daily versus less than daily.

2.5. Ed-TAME-ChatGPT Constructs and Items

The Ed-TAME-ChatGPT tool assessed faculty perspectives across six theoretical constructs using a series of statements rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Disagree, 2 = Somewhat Disagree, 3 = Neutral/No Opinion, 4 = Somewhat Agree, 5 = Agree) as outlined by Barakat et al. in [

70]. The exact items for each construct were as follows: Perceived Usefulness with five items: (1) I think that ChatGPT is helpful to improve the quality of my academic duties; (2) I think that ChatGPT use would be helpful to increase my research output; (3) I think that ChatGPT would be helpful to find research information more quickly and accurately; (4) I believe that using ChatGPT would enhance the quality of research output; and (5) I think that using ChatGPT would provide me with new insights on my research. Perceived Effectiveness with five items: (1) ChatGPT would be helpful in increasing student engagement with academic tasks; (2) ChatGPT would be helpful in improving the overall quality of education and students’ performance; (3) ChatGPT would be helpful in enhancing the creativity in my academic duties; (4) I feel comfortable with the idea of incorporating ChatGPT into my academic duties; and (5) Adopting ChatGPT would efficiently enhance my performance in academic duties.

The Technology Readiness construct comprised five items: (1) I regularly incorporate technology into my research and teaching; (2) I have the habit of staying up to date with the latest technological advancements; (3) I feel comfortable using technology to assist in my academic duties; (4) I am confident in my ability to learn new technologies quickly; and (5) I regularly seek training and resources to improve my technological skills. The Social Influence construct comprised four items: (1) I would adopt ChatGPT if it is recommended by a reputable colleague in my academic field; (2) I believe that using ChatGPT in research and teaching is an acceptable practice among my academic colleagues; (3) I would be more likely to use ChatGPT if my students express a positive attitude toward it; and (4) I would be more likely to use ChatGPT if it was recommended by my university or college.

The Anxiety construct comprised five items: (1) I fear that ChatGPT would disrupt the traditional methods of research and teaching; (2) I am concerned about the reliability of ChatGPT in research and education; (3) I fear that the use of ChatGPT would lead to errors in my research and academic duties; (4) I am concerned about the potential impact of ChatGPT on the originality of my work; and (5) I am concerned about new ethical issues created by ChatGPT in research and teaching. Finally, the Perceived Risk comprised three items: (1) Adopting ChatGPT could lead to loss of academic jobs or reduced job security for academics; (2) I feel concerned that using ChatGPT would negatively impact the quality of my research and teaching; and (3) I feel concerned about the privacy and security of my data when using ChatGPT.

2.6. Statistical and Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and JASP software (Version 0.19.0, accessed 9 November 2024) [

74]. To validate the structure of the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT scale, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using maximum likelihood estimation with Oblimin rotation. Sampling adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure, while factorability was confirmed with Bartlett’s test of sphericity. A subsequent CFA was conducted to validate the latent factor structure of the scale. Model fit was evaluated using multiple fit indices, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), goodness of fit index (GFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). Internal consistency for each Ed-TAME-ChatGPT construct was measured using Cronbach’s α, with a threshold of ≥0.60 considered acceptable for reliability [

75,

76].

Ed-TAME-ChatGPT construct scores were calculated as the average of item scores within each construct, with Agree = 5, Somewhat Agree = 4, Neutral/No Opinion = 3, Somewhat Disagree = 2, and Disagree = 1. Data normality for scale variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which indicated non-normality across all constructs (

p < 0.001). Consequently, non-parametric tests were applied for univariate analysis, including the Mann-Whitney

U test (M-W) and Kruskal-Wallis test (K-W). Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test for associations. To examine the bivariate association between Ed-TAME-ChatGPT constructs, Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient (

ρ) was used [

77]. This non-parametric test was selected because the constructs showed non-normal distribution as stated earlier.

To explore the determinants of educators’ attitudes toward genAI, specifically Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness, univariate analyses were initially conducted to identify candidate predictors based on a significance threshold of

p ≤ 0.100. Multivariate linear regression models were then applied, with the validity of each model confirmed through analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multicollinearity diagnostics were performed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), with a threshold of VIF > 5 indicating potential multicollinearity issues [

78]. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at

p < 0.050.

4. Discussion

In this large multinational study of university educators in Arab countries, the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT instrument demonstrated strong construct validity and internal consistency, supporting its use as a theory-driven tool for assessing attitudes toward genAI in higher education. The multivariate analyses affirmed the theoretical model: Technology Readiness and Social Influence emerged as strong positive predictors of Perceived genAI Usefulness and Effectiveness, while Anxiety was consistently associated with more negative perceptions. These findings reinforce the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT explanatory utility and its consistency with broader TAM-based research on digital innovation in education. The results suggests that Ed-TAME-ChatGPT represents a coherent framework that aligns with established evidence obtained via TAM-based studies for technology acceptance (e.g., using online platform, metaverse, etc.) in education [

79,

80,

81,

82]. The validated Ed-TAME-ChatGPT framework provides educational institutions with a practical means to benchmark faculty readiness for genAI adoption and to guide targeted interventions that address both enabling factors and barriers. This is especially critical in a context where faculty attitudes, while broadly supportive of genAI tools like ChatGPT, remain shaped by underlying concerns about academic integrity, pedagogical impact, and institutional preparedness [

83,

84]. These concerns revolve around the absence of clear policies, particularly regarding academic integrity, learning effectiveness, and teaching efficiency, as demonstrated by Jiang et al. analysis of X (formerly Twitter) data [

85].

The findings of this study highlighted the ubiquitous adoption of genAI among university faculty in Arab countries. Notably, 95% of the participants in this study reported previous use of genAI tools, with an overwhelming 92% specifically using ChatGPT. This near-universal engagement with genAI tools among university educators marks a profound departure from earlier phases of digital adoption in academia, suggesting not merely a passing interest but an accelerating transformation in the way educators interface with technology. This trend aligns with the growing evidence from diverse educational settings across the globe among the students and educators alike [

86,

87,

88,

89]. For example, Ogurlu and Mossholder reported that while 67% of educators were aware of ChatGPT in a qualitative study, its use was more limited, reflecting the rapid escalation in both awareness and functional engagement observed in the current study [

90]. Similarly, Kiryakova et al. documented widespread ChatGPT adoption among Bulgarian university professors, especially for tasks integral to academic duties, such as grammar correction, translation, transcription, and educational content creation [

88]. In Malaysia, Au observed that approximately half of surveyed faculty reported using ChatGPT for academic purposes, further reinforcing the notion that this technological shift is neither isolated nor region-specific [

91].

This body of evidence collectively contradicts the prevailing notion that novel technologies such as genAI tools are primarily the domain of students which was shown in various studies in different contexts through the notable work of Strzelecki [

52,

61,

92,

93]. While previous studies, including a systematic review by Deng et al. [

94], and research from the UAE [

59], Jordan [

95], Indonesia [

96], Nigeria [

97], Slovakia, Portugal, and Spain [

98], have predominantly documented the adoption of genAI among students for tasks such as academic writing assistance and information synthesis, the present study findings revealed a parallel evolution among faculty. This result highlighted that educators are not merely passive observers of technological shifts but active participants, integrating these tools into their professional routines in line with findings by Al-kfairy and Bhat et al. [

99,

100].

Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness which were the central attitudinal outcomes in this study, both strongly predicted by core constructs of the Ed-TAME-ChatGPT framework. The results of hypothesis testing further affirmed the theoretical model as follows. Technology Readiness (H1) and Social Influence (H2) were consistently and positively associated with both Perceived Usefulness and Effectiveness, while Anxiety (H3) demonstrated significant negative associations. Perceived Risk (H4), while theoretically important, showed weaker and inconsistent effects, emerging as non-significant in the model predicting usefulness and only approaching significance in the effectiveness model.

Consistent with H1, Technology Readiness emerged as a significant positive predictor of both Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness. Faculty who reported feeling confident, comfortable, and proactive in using new technologies were more likely to view genAI favorably. This finding aligns with existing literature identifying technology readiness as a key enabler of innovation adoption in academic settings and highlights the importance of institutional investment in digital literacy development [

101,

102,

103]. Importantly, H1 reinforces the principle that access to technology, when paired with familiarity and self-efficacy, fosters engagement and skill development [

104,

105]. This is an aspect that should be considered in order to decrease any genAI-related digital divide and improve educational equity as shown by Afzal et al. [

106]. Thus, the positive association between Technology Readiness and genAI attitudes emphasizes the crucial role of institutional investment in digital literacy and continuous faculty development [

107]. However, it is important to highlight that technology readiness alone does not guarantee advanced technology use but rather basic operational comfort—a distinction that policymakers must consider when designing faculty genAI training programs [

108].

Hypothesis 2 was also supported, with Social Influence emerging as the strongest positive predictor of both Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness of genAI. These findings underline the important role of perceived normative support in shaping faculty attitudes toward educational innovation and suggest that social context may exert a notable influence on genAI adoption in higher education [

109,

110,

111]. The prominence of Social Influence in the predictive models highlights the importance of cultivating an institutional culture that visibly supports genAI integration. Strategies such as peer-led professional development, recognition of early adopters, and student engagement initiatives may serve to reinforce the positive view of genAI use as a social norm [

112,

113,

114].

The findings also supported H3, with Anxiety demonstrating a significant negative association with both Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Effectiveness of genAI. Educators who reported discomfort, uncertainty, or ethical concerns regarding genAI were less likely to perceive it as beneficial. This finding highlights the role of psychological and moral apprehensions as substantive barriers to genAI adoption in academic settings as recently reported among health students in Arab countries [

55]. Notably, Anxiety reflects more than technological unfamiliarity; it encompasses deeper concerns related to academic integrity, intellectual displacement, and the erosion of scholarly originality [

115,

116]. In contrast, H4 in this study, which posited that Perceived Risk such as job displacement, data privacy, and academic quality concerns would negatively influence attitudes toward genAI, was not supported. Perceived Risk did not emerge as a significant predictor of educators’ attitudes in the multivariate analysis of Perceived Usefulness or Perceived Effectiveness. These findings suggest that although risk-related concerns are present among educators, they exert limited influence on core attitudinal outcomes once factors such as Social Influence, Anxiety, and Technology Readiness are accounted for. This may indicate that risk perceptions are either normalized within the broader discourse on digital transformation or are outweighed by the perceived benefits of genAI in academic practice.

Interestingly, while nationality and university location significantly predicted Perceived Effectiveness in this study, they did not emerge as significant predictors of Perceived Usefulness. This distinction may reflect the contextual nature of what “Effectiveness” means in practice. While Perceived Usefulness is likely driven by individual-level assessments of productivity and utility—relatively stable across academic cultures—Perceived Effectiveness may be more sensitive to the institutional environment, pedagogical norms, and broader educational infrastructure. For example, faculty working in universities with greater digital integration or institutional endorsement of AI may feel that genAI tools are more effectively implemented, regardless of their personal views on usefulness [

117]. Similarly, cultural factors tied to nationality—such as openness to pedagogical innovation, attitudes toward automation, or institutional trust—may influence how educators evaluate genAI’s capacity to deliver meaningful educational outcomes [

118]. These findings suggest that effectiveness perceptions are not merely individual judgments but are shaped by the academic settings in which educators operate [

119]. For example, The GCC region investment in digital transformation strategies, paired with sustained professional development and integration of emerging technologies into educational policy, likely accounts for this higher genAI competency [

120,

121,

122]. Conversely, regions with lower reported genAI competence may reflect resource limitations, restricted access to training, or a cultural hesitancy toward disruptive technologies [

106,

123,

124]. These findings highlight the need for regionally customized educational policies, where disparities in technological equity are addressed not through uniform policies but through context-sensitive strategies that prioritize both capacity-building and resource allocation [

125].

A noteworthy and somewhat counterintuitive finding in this study was the inverse association between academic qualification level and Perceived Usefulness of genAI. Educators holding a PhD or equivalent consistently rated genAI as less useful than those with a master’s or even a bachelor’s degree, a trend confirmed in both univariate and multivariate analyses. This pattern may reflect deeper epistemological reservations among doctoral-trained faculty, who often emphasize originality, methodological rigor, and theoretical depth—qualities they may perceive as compromised by AI-generated outputs. Moreover, seasoned academics may be more entrenched in established workflows and less receptive to altering scholarly habits with emerging technologies. In contrast, educators with lower academic ranks may prioritize efficiency, accessibility, and practical enhancement of academic tasks—leading to more favorable appraisals of genAI’s usefulness. This distinction suggests that Perceived Usefulness is not merely a function of exposure or competence, but also of disciplinary culture, academic identity, and professional expectations [

126].

4.1. Policy Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study highlight the importance of developing evidence-informed, context-sensitive policies for integrating genAI into higher education. Rather than relying on generalized technology access strategies, institutional responses should prioritize individual faculty readiness, address psychological and ethical barriers, and reduce regional disparities. The significant roles of Technology Readiness, Social Influence, and Anxiety in shaping faculty attitudes toward genAI suggest multiple actionable insights for intervention.

Given that Social Influence emerged as the most powerful predictor of both perceived usefulness and effectiveness of genAI, institutional strategies should prioritize the cultivation of normative support and peer-led momentum. Social Influence in the context of educational technology adoption encompasses perceived endorsement from colleagues, students, and leadership, which can significantly shape individual attitudes and behaviors. This finding aligns with broader theoretical perspectives, including the UTAUT, which positions Social Influence as a key determinant of behavioral intention which should be taken into consideration in educational policies that aim to integrate genAI use as a routine useful practice [

111,

114,

127].

The consistent predictive power of Technology Readiness across both attitudinal outcomes highlights the need to move beyond tool provision and toward structured capacity-building. Institutions should develop targeted, discipline-specific professional development programs that emphasize applied genAI use in teaching, research, and administration. Importantly, these programs should accommodate differing levels of technological fluency. Intergenerational mentorship—pairing digitally fluent early-career academics with senior faculty—could help bridge confidence gaps and normalize genAI use across career stages. Such inclusive strategies are essential for fostering equitable genAI readiness across academic ranks and disciplines [

128].

The negative association between Anxiety and both Perceived Usefulness and Effectiveness in this study reinforces the need for clear ethical and pedagogical boundaries around genAI use [

129]. Faculty unease—whether tied to intellectual displacement, originality concerns, or fear of losing academic integrity—is not merely reactionary but rooted in legitimate academic concerns [

130]. Institutions must therefore craft transparent, enforceable guidelines on acceptable genAI applications in both instruction and scholarship [

131]. These guidelines should be co-developed with faculty to ensure they are grounded in academic reality and uphold principles of academic integrity. Topics such as data privacy, authorship, plagiarism detection, and acceptable assistance in assessments should form the core of these frameworks [

131].

The finding that nationality and university location predicted Perceived Effectiveness—but not Usefulness—highlights the influence of institutional and regional disparities in infrastructure, genAI integration, and digital culture. Faculty in GCC countries and private universities reported more favorable attitudes, likely due to greater institutional support. To address these structural inequities, policymakers should invest in under-resourced institutions and establish national digital literacy standards that respect local educational systems. Regional collaboration through faculty exchanges, joint training, and academic consortia can further bridge gaps in genAI preparedness and foster equitable adoption across higher education contexts.

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

While the current study offered valuable insights into the adoption of genAI among university educators in the Arab region, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the use of convenience and snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias, as participants were drawn primarily from the authors’ professional networks and social media platforms, potentially limiting the representativeness of the broader academic population in Arab universities. Second, the reliance on self-reported data for both genAI frequency of use and genAI competency raises concerns about social desirability bias, where participants may have either overestimated or underestimated their technological proficiency. Third, the cross-sectional design, while useful to get a snapshot of educators attitude to genAI, constrained the ability to assess how attitudes and practices evolve over time with continued exposure to genAI tools. Finally, while the study spanned multiple Arab countries, variations in national education policies, technological infrastructure, and institutional culture may limit the generalizability of the findings beyond the sampled regions.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the study possesses several notable strengths that reinforce the validity and relevance of its findings. First, the inclusion of a large and diverse sample of university educators across multiple academic disciplines and geographical regions provided a comprehensive snapshot of genAI adoption patterns in Arab universities. Second, the study employed rigorous QC measures, including minimum completion time thresholds and the verification of unique IP addresses, which helped to ensure the integrity of data and participant engagement which addressed caveats in survey studies as reported by Nur et al. [

132]. Third, the use of the validated Ed-TAME-ChatGPT scale, a psychometrically valid instrument, ensured strong construct validity and internal consistency, enhancing the methodological robustness of our study. Finally, the exploration of multiple demographic, professional, and institutional predictors helped to provide actionable insights for policy development and faculty support strategies. These strengths ensured that the findings remain highly relevant for policymakers, academic leaders, and institutional decision-makers in the attempt to address the challenges of genAI successful integration in higher education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Malik Sallam; methodology, Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Asmaa Al-Qaisi, Osama Mohamed Ibrahim, Mohammed Sallam; software, Malik Sallam; validation, Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan and Mohammed Sallam; formal analysis, Malik Sallam; investigation, Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Asmaa Al-Qaisi, Osama Mohamed Ibrahim, Mohammed Sallam; resources, Malik Sallam; data curation, Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Asmaa Al-Qaisi, Osama Mohamed Ibrahim, Mohammed Sallam; writing—original draft preparation, Malik Sallam; writing—review and editing, Malik Sallam, Ahmad Samed Al-Adwan, Maad M. Mijwil, Doaa H. Abdelaziz, Asmaa Al-Qaisi, Osama Mohamed Ibrahim, Mohammed Sallam; visualization, Malik Sallam; supervision, Malik Sallam; project administration, Malik Sallam. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.