Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Higher Education

2.2. Artificial Intelligence

2.3. Compatibility

2.4. Complexity

2.5. UX

2.6. User Satisfaction

2.7. Performance Expectation

2.8. Introducing AI New Tools

2.9. AI Strategic Alignment

2.10. Availability of Resources

2.11. Competative Pressure (COP)

2.12. Government Regulations (GOR)

2.13. Technological Support

2.14. Facilitating Conditions

2.15. AI Adoption Intention

3. Objectives

4. Methodology

4.1. Participant

4.2. Data Collecttion

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Research Methodologies

5.1. Research Question

5.2. Deductive Approach

5.3. Population

5.4. Sample Size Calculation

5.5. Sampling Method

5.6. Rational for Purposive Sampling

5.7. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Structuring

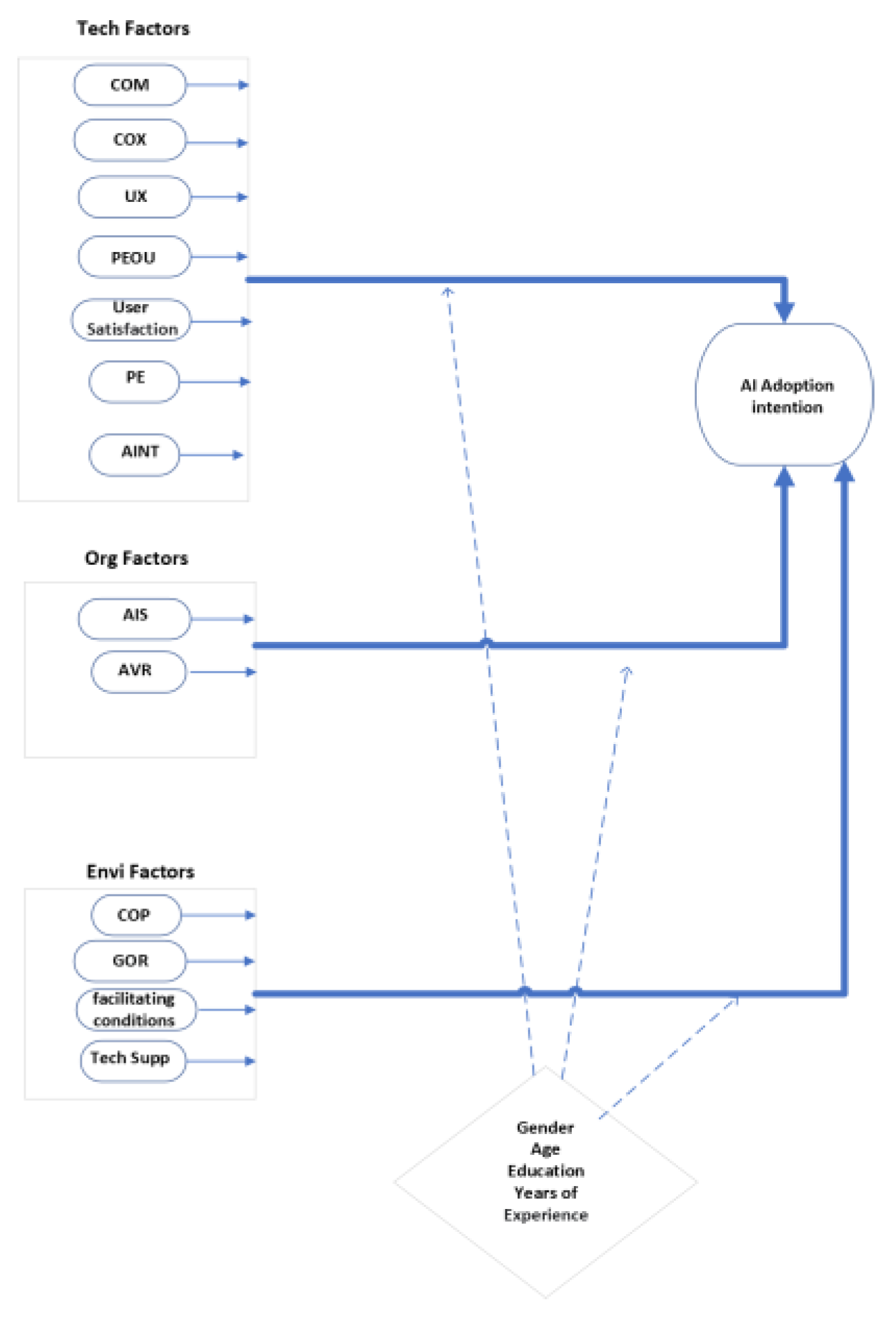

5.8. Research Hypotheses

5.9. The Research Model

5.10. Data Analysis

5.11. Descriptive Analysis

- 1)

- Sample Characteristics

- 2)

- What Type of AI Tools Do You Use for Your Work or School Needs?

- 3)

- How Has Management Supported the Usage of AI in Your Workplace?

- 4)

- What Are Some of the Resources That You Believe Support the Adoption of AI In Yout Organization?

- 5)

- What Are Some of the Assistances Offerd by State Authorities to Motivate the Adoption Of AI?

- 6)

- What Technological Support Does Your Organization Have to Support the Adoption of AI?

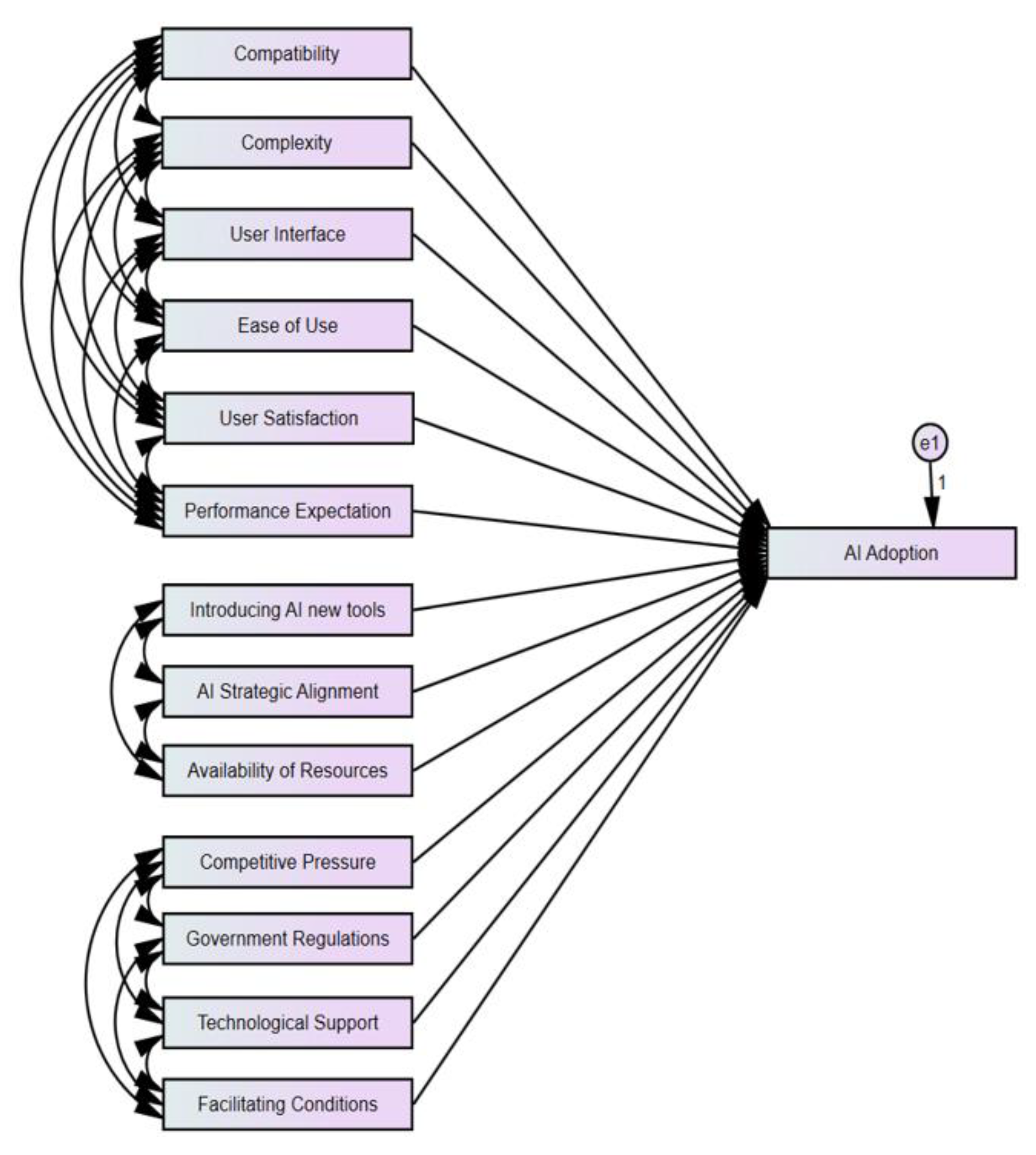

5.12. Testing the Model

- 1)

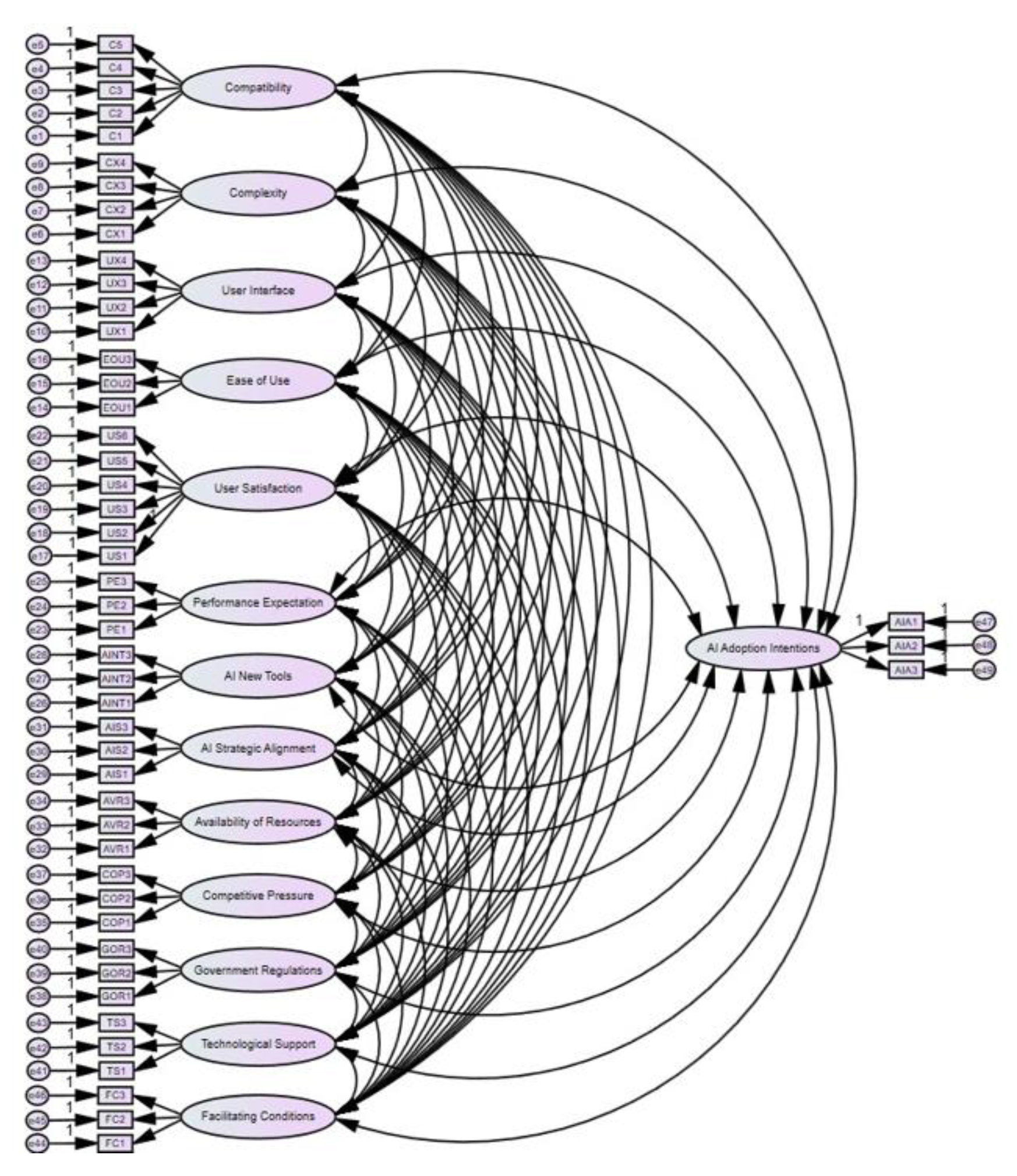

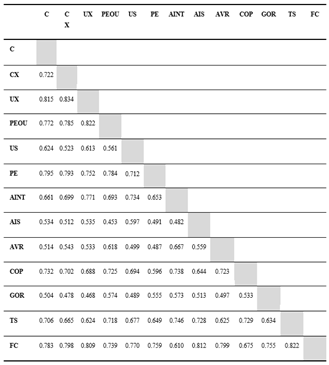

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- 2)

- Goodness of Fit

5.13. Testing the Hypotheses

- 1)

- Testing the first hypothesis

- Compatibility (C) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the first alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Complexity (CX) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the second alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Complexity (CX) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the second alternative sub-hypothesis.

- User Interface (UX) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the third alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p- value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the fourth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- User Satisfaction (US) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the fifth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Performance Expectation (PE) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (.001) is less than 0.01 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the sixth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- AI introducing new tools (AINT) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p- value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the seventh alternative sub-hypothesis.

- AI Strategic Alignment (AIS) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (.003) is less than 0.01 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the eighth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Availability of Resources (AVR) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p- value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the ninth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- As per Byrne (2013), the regression weights indicate that Competitive Pressure (COP) has an insignificant impact on AI adoption intentions. This is because the critical ratio value is less than 2, and the p-value (0.421) is higher than 0.05, indicating that the path is not significant. The tenth null hypothesis is thus accepted.

- As per Byrne (2013), the regression weights indicate Government Regulations (GOR) has an insignificant impact on AI adoption intentions. This is because the critical ratio value is less than 2, and the p-value (0.785) is higher than 0.05, indicating that the path is not significant. The eleventh null hypothesis is thus accepted.

- Technological Support (TS) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the twelfth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- Facilitating Conditions (FC) has a positive significant impact on AI adoption intentions, as indicated by the regression weights; the route is significant since the p-value (***) is less than 0.001 and the crucial ratio value is more than 2 (Byrne, 2013). Consequently, it is decided to embrace the thirteenth alternative sub-hypothesis.

- 2)

- Testing the Second Hypothesis

6. Conclusion and Future Work

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Future Works and Recommedations

- 1)

- Compatibility (C): The results indicate that Compatibility has a significant positive impact on AI adoption intentions. Further research should investigate how institutions might improve the compatibility of artificial intelligence (AI) technology with current systems and processes, to allow a more effortless adoption.

- 2)

- Complexity (CX): Complexity also shows a significant positive impact on AI adoption intentions. Further study endeavors may explore methods to streamline AI technologies and diminish apparent intricacy, promoting wider consumer acceptance.

- 3)

- User Interface (UX): The positive impact of User Interface on AI adoption aspirations underscores the need to craft user-friendly interfaces. Subsequent research should prioritize creating user-friendly and easily available artificial intelligence systems that ad- dress the varied requirements of individuals in higher education.

- 4)

- Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU): The strong correlation between Perceived Ease of Use and AI adoption intentions indicates that institutions should prioritize providing training and support to boost users’ confidence in employing AI technologies. Subsequent studies could investigate the efficacy of various training programs in enhancing the perception of usability.

- 5)

- User Satisfaction (US): User Satisfaction significantly influences AI adoption intentions, indicating that organizations must ensure a positive user experience with AI tools. Subsequent research should investigate the elements influencing user happiness and determine improving methods.

- 6)

- Performance Expectation (PE): The findings reveal that Performance Expectation positively impacts AI adoption intentions. Future research should explore how organizations might effectively convey the anticipated advantages of AI technologies t prospective users.

- 7)

- Demographic Variables: The study highlights the mediating roles of demographic variables such as age, gender, education, and years of experience. Further investigation is needed to explore the impact of these characteristics on the adoption of AI technology and develop strategies accordingly. To summarize, the results of this study highlight the significance of resolving the highlighted elements to improve the intent of higher education institutions to use artificial intelligence. Further investigation should be conducted to examine these aspects, offering practical knowledge for policymakers and educational administrators to promote the effective incorporation of AI in academic environments.

References

- Ahmad, S., Miskon, S., Alkanhal, T.A. and Tlili, I. (2020), “Modeling of business intelligence systems using the potential determinants and theories with the lens of individual, technological, organizational, and environmental contexts-a systematic literature review”, Applied Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 9, pp. 3208–3208.

- ALTakhayneh, S.K., Karaki, W., Hasan, R.A., Chang, B., Shaikh, J.M. and Kanwal,W. (2022), “Teachers’ psychological resistance to digital innovation in Jordanian entrepreneurship and business schools: moderation of teachers’ psychology and attitude toward educational technologies”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A., Dwivedi, Y.K. and Rana, N.P. (2017), “Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: extending utaut2 with trust”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 37 No. 3, pp. 99–110. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.S., Yarborough, M. and Smith, A. (2023). [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M.I. (2020), “Assessing factors affecting intention to adopt AI and ML: The case of the Jordanian retail industry”, Periodicals of Engineering and Natural Sciences (PEN), Vol. 8 No. 4, pp. 2516–2524. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.D. and Hatef, E.A.J.A. (2024), “Types of sampling and sample size determination in health and social science research”, Journal of Young Pharmacists, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 204–215.

- Alsheibani, S., Messom, C. and Cheung, Y. (2020), “Re-Thinking the Competitive Land- scape of Artificial Intelligence”, in “Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS)”, pp. 5861–5870.

- Arshad, Y., Chin, W.P., Yahaya, S.N., Nizam, N.Z., Masrom, N.R. and Ibrahim, S.N.S. (2018), “Small and medium enterprises’ adoption for e-commerce in Malaysia tourism state”, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 10. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X. (2024), “The role and challenges of artificial intelligence in information technol- ogy education”, Pacific International Journal, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 86–92.

- Bearman, M. and Ajjawi, R. (2023), “Learning to work with the black box: pedagogy for a world with artificial intelligence”, British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 54 No. 5, pp. 1160–1173. [CrossRef]

- Beshdeleh, M., Angel, A. and Bolour, L. (2020), “Adoption of EBET Agency’s Cloud Casino Software by using TOE and DOI Theory as a Solution for Gambling Website. Maxwell Beshdeleh et al. Adoption of EBET Agency’s Cloud Casino Software by using TOE and DOI Theory as a Solution for Gambling Website”, Journal of Innovation and Business Research, Vol. 116, pp. 100–119.

- Bharadiya, J.P. (2023), “Machine learning and AI in business intelligence: Trends and opportunities”, International Journal of Computer (IJC), Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 123–134.

- Boonsiritomachai, W., Mcgrath, G.M. and S, B. (2016), “Exploring business intelligence and its depth of maturity in Thai SMEs”, Cogent Business & Management, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 1220663–1220663. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A., Karadeniz, A., Bañeres, D. and Rodríguez, M.E. (2021), “Artificial intel- ligence and reflections from educational landscape: a review of ai studies in half a century”, Sustainability, Vol. 13 No. 2. [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J. (2023), “Does artificial intelligence kill employment growth: the missing link of corporate ai posture”, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 6. [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C. and Villar-López, A. (2011), “Non-technical innovation: organizational memory and learning capabilities as antecedent factors with effects on sustained com- petitive advantage”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 40 No. 8, pp. 1294–1304. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.C. (2010), “A new perspective on Twitter hashtag use: Diffusion of innovation theory”, Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 47, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Ghosh, S.K. and Chaudhuri, R. (2020a), “Knowledge management in im- proving business process: an interpretative framework for successful implementation of ai-crm-km system in organizations”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 1261–1281. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Ghosh, S.K., Chaudhuri, R. and Chaudhuri, S. (2020b), “Adoption of ai- integrated crm system by indian industry: from security and privacy perspective”, Computer Security, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Chen, S., Khan, A., Lim, M.K. and Tseng, M. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Li, L. and Chen, Y. (2020a), “Explore success factors that impact artificial intelligence adoption on telecom industry in china”, Journal of Management Analytics, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 36–68. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chen, P. and Lin, Z. (2020b), “Artificial intelligence in education: a review”,IEEE Access, Vol. 8, pp. 75264–75278.

- Crompton, H. and Song, D. (2021). [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D., Bagozzi, R.P. and Warshaw, P.R. (1989), “Technology acceptance model”, J Manag Sci, Vol. 35 No. 8, pp. 982–1003.

- Dora, M., Kumar, A., Mangla, S.K., Pant, A. and Kamal, M.M. (2021), “Critical success factors influencing artificial intelligence adoption in food supply chains”, International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 60 No. 14, pp. 4621–4640. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y., Edwards, J.S. and Dwivedi, Y.K. (2019), “Artificial intelligence for decision making in the era of Big Data-evolution, challenges and research agenda”, Interna- tional journal of information management, Vol. 48, pp. 63–71.

- Dwivedi, Y.K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T., Williams, and D, M. (2021), “Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy”, In- ternational Journal of Information Management, Vol. 57, pp. 101994–101994.

- Eftimov, L. and Kitanovikj, B. (2023), “Unlocking the path to ai adoption: antecedents to behavioral intentions in utilizing ai for effective job (re)design”, Journal of Human Resource Management - HR Advances and Developments, Vol. 2023 No. 2, pp. 123– 134. [CrossRef]

- Enholm, I.M., Papagiannidis, E., Mikalef, P. and Krogstie, J. (2022), “Artificial intelli- gence and business value: A literature review”, Information Systems Frontiers, Vol. 24 No. 5, pp. 1709–1734.

- Farida, I., Ningsih, W., Lutfiani, N., Aini, Q. and Harahap, E.P. (2023), “Responsible urban innovation working with local authorities a framework for artificial intelligence (ai)”, Scientific Journal of Informatics, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 121–126.

- George, B. and Wooden, O. (2023), “Managing the strategic transformation of higher education through artificial intelligence”, Administrative Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 9, pp. 196–196. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, E.K., Ariffin, N. and Sukmadilaga, C. (2022), “Factors influencing artificial intelli- gence adoption in publicly listed manufacturing companies: a technology, organisation, and environment approach”, International Journal of Applied Economics, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 108–117.

- Govindan, K. (2024), “How artificial intelligence drives sustainable frugal innova- tion: a multitheoretical perspective”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 71, pp. 638–655.

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P. and Kyriakidou, O. (2004), “Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations”, The Milbank Quarterly, Vol. 82 No. 4, pp. 581–629. [CrossRef]

- Greiner, C., Peisl, T.C., Höpfl, F. and Beese, O. (2023), “Acceptance of ai in semi-structured decision-making situations applying the four-sides model of communication-an empirical analysis focused on higher education”, Education Sci- ences, Vol. 13 No. 9. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. and Gupta, C. (2023), “Synchronizing innovation: unveiling the synergy of need-based and curiosity-based experimentation in ai technology adoption for li- braries”, Library Hi Tech News, Vol. 40 No. 9, pp. 15–17. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2011), “PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet”, The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 139–152.

- Hannan, E. (2021a, b), “Ai: new source of competitiveness in higher education”, Competi- tiveness Review: An International Business Journal, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 265–279.

- Harwood, S. and Eaves, S. (2020), “Conceptualising technology, its development and future: The six genres of technology”, Technological forecasting and social change, Vol. 160, pp. 120174–120174.

- Henke, J. (2024), “Navigating the ai era: university communication strategies and per- spectives on generative ai tools”, Journal of Science Communication, No. 03, pp. 23– 23. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2015), “A New Criterion for Assessing Dis- criminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 115–135.

- Hu, L. and Bentler, P.M. (1999).

- Hungund, S. and Mani, V. (2019), “Benchmarking of factors influencing adoption of inno- vation in software product SMEs: An empirical evidence from India”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 26 No. 5, pp. 1451–1468.

- Islam, M.N., Khan, N.I., Inan, T.T. and Sarker, I.H. (2023), “Designing user interfaces for illiterate and semi-literate users: a systematic review and future research agenda”, SAGE Open, Vol. 13 No. 2. [CrossRef]

- Ismatullaev, U.V.U. and Kim, S.H. (2022), “Review of the factors affecting acceptance of ai-infused systems”, Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Er- gonomics Society, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 126–144.

- Jain, R., Garg, N. and Khera, S.N. (2022), “Adoption of ai-enabled tools in social devel- opment organizations in india: an extension of utaut model”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M.H., Kenyon, S., Brown, A., Donahue, C. and Wicher, C. (2022), “Artificial intelligence: a strategy to harness its power through organizational learning”, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 44 No. 3, pp. 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Jöhnk, J., Weißert, M. and Wyrtki, K. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. (2005), Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, Guilford Press, New York, NY.

- Lee, H., Lee, S. and Shin, J. (2020), “An analysis on the satisfaction and perception of performance outcomes of the university information disclosure system”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Educational Management Research, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C. and Chen, X. (2022), “Exploring users’ adoption intentions in the evolution of artificial intelligence mobile banking applications: the intelligent and anthropomorphic perspectives”, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 40 No. 4, pp. 631–658. [CrossRef]

- Low, C., Chen, Y. and Wu, M. (2011). [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R. and Cukurova, M. (2019), “Designing educational technologies in the age of ai: a learning sciences-driven approach”, British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 50 No. 6, pp. 2824–2838. [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, F.H., Isa, N.M., Ishak, K. and Salleh, H. (2024), “Navigating the adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education”, International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship (IJBT), Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.J. (2023), “Searching for inclusive artificial intelligence for social good: par- ticipatory governance and policy recommendations for making ai more inclusive and benign for society”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 83 No. 6, pp. 1496–1505. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K. (2021), “Artificial intelligence and the nhs: a qualitative exploration of the factors influencing adoption”, Future Healthcare Journal, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 648–654. [CrossRef]

- Noordt, C.V. and Misuraca, G. (2020), “Exploratory insights on artificial intelligence for government in europe”, Social Science Computer Review, Vol. 40 No. 2, pp. 426–444.

- Okunlaya, R.O., Abdullah, N.S. and Alias, R.A. (2022a), “Artificial intelligence (ai) library services innovative conceptual framework for the digital transformation of uni- versity education”, Library Hi Tech, Vol. 40 No. 6, pp. 1869–1892. [CrossRef]

- Opesemowo, O.A.G. and Adekomaya, V. (2024), “Harnessing artificial intelligence for advancing sustainable development goals in south africa’s higher education system: a qualitative study”, International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Re- search, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 67–86. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., Froese, F. and Liu, N. (2022), “The adoption of artificial intelligence in employee recruitment: The influence of contextual factors”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 33 No. 6, pp. 1125–1147. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J., Jeong, Y.J., An, Y.S. and Ahn, J.K. (2022), “Analyzing the Factors Influenc- ing the Intention to Adopt Autonomous Ships Using the TOE Framework and DOI Theory”, Journal of Navigation and Port Research, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 134–144.

- Paton, C. and Kobayashi, S. (2019), “An open science approach to artificial intelligence in healthcare”, Yearbook of Medical Informatics, Vol. 28 No. 01, pp. 47–051. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R., Metri, B.A. and Kaushik, N. (2023), “Students’ adoption of ai-based teacher- bots (t-bots) for learning in higher education. Information Technology &Amp”, People, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 328–355. [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R. and Sivathanu, B. (2020), “Adoption of artificial intelligence (ai) for talent ac- quisition in it/ites organizations”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 27 No. 9, pp. 2599–2629.

- Polyportis, A. (2024), “A longitudinal study on artificial intelligence adoption: under- standing the drivers of chatgpt usage behavior change in higher education”, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 6. [CrossRef]

- Popenici, S. and Kerr, S. (2017a, b), “Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teach- ing and learning in higher education”, Technology Enhanced Learning, Vol. 12 No. 1. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. and Millar, V. (2002).

- Priyadarshinee, P., Raut, R.D., Jha, M.K. and Gardas, B.B. (2017), “Understanding and predicting the determinants of cloud computing adoption: A two staged hybrid SEM- Neural networks approach”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 76, pp. 341–362. [CrossRef]

- Qasem, Y.A., Abdullah, R., Yah, Y., Atan, R., Al-Sharafi, M.A. and Al-Emran, M. (2021), “Towards the development of a comprehensive theoretical model for examining the cloud computing adoption at the organizational level”, Recent Advances in Intelligent Systems and Smart Applications, pp. 63–74.

- Rasheed, H.M.W., Yuanqiong, H., Khizar, H.M.U. and Khalid, J. (2024), “What drives the adoption of artificial intelligence among consumers in the hospitality sector: a sys- tematic literature review and future agenda”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Tech- nology, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 211–231. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. (2003), Diffusion of innovations, Free Press, New York.

- Saidakhror, G. (2024), “The impact of artificial intelligence on higher education and the economics of information technology”, International Journal of Law and Policy, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sallu, S., Raehang, R. and Qammaddin, Q. (2024), “Exploration of artificial intelligence (ai) application in higher education”, Architecture and High Performance Computing, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 315–327. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., Sharma, A., Sharma, W.R. and Dillon (2005), “A simulation study to inves- tigate the use of cutoff values for assessing model fit in covariance structure models”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58, pp. 935–943.

- Sun, H., Fang, Y. and Zou, H. (2016), “Choosing a fit technology: understanding mind- fulness in technology adoption and continuance”, Journal of the Association for Infor- mation Systems, Vol. 17 No. 6, pp. 377–412. [CrossRef]

- Tanantong, T. and Wongras, P. (2024), “A utaut-based framework for analyzing users’ intention to adopt artificial intelligence in human resource recruitment: a case study of thailand”, Systems, Vol. 12 No. 1. [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A., Masa’deh, R., Al-Busaidi, K.A., Mohammed, A.B. and Maqableh, M. (2017), “Factors influencing students’ adoption of e-learning: a structural equation modeling approach”, Journal of International Education in Business, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 164–182. [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G. and Fleischer, M. (1990), The Processes of Technological Innovation. Issues in organization and management series, Lexington Books, Lexington, Mas- sachusetts.

- Tuffaha, M. and Perello-Marin, M.R. (2022), “Adoption factors of artificial intelligence in human resources management”, Future of Business Administration, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W., Khanagha, S., Baden-Fuller, C., Mihalache, O.R. and Birkinshaw, J. (2021).

- Wong, J.W. and Yap, K.H.A. (2024), “Factors influencing the adoption of artificial in- telligence in accounting among micro, small medium enterprises (msmes)”, Quantum Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 16–28.

- Wu, W., Zhang, B., Li, S. and Liu, H. (2022), “Exploring Factors of the Willingness to Accept AI-Assisted Learning Environments: An Empirical Investigation Based on the UTAUT Model and Perceived Risk Theory”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 13, pp. 870777–870777. [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V.I., Bond, M. and Gouverneur, F. (2019), “Systematic re- view of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education - where are the educators?”, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, No. 1, pp. 16–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Wang, R. and Pu, C. (2022), ““i am chatbot, your virtual mental health ad- viser.” what drives citizens’ satisfaction and continuance intention toward mental health chatbots during the covid-19 pandemic? an empirical study in china”, Digital Health, Vol. 8.

| Variable | Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 187 | 51 |

| Female | 180 | 49 | |

| Other | - | - | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Age | 18-24 | 55 | 15 |

| 25-33 | 71 | 19.3 | |

| 34-44 | 175 | 47.7 | |

| 45-54 | 40 | 10.9 | |

| 55-65 | 26 | 7.1 | |

| 66 and older | - | - | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Residence | Turkey | 71 | 19.4 |

| USA | 192 | 52.3 | |

| Canada | 104 | 28.3 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Education | Diploma’s degree | - | - |

| Bachelor's degree | 46 | 12.5 | |

| Master's degree | 104 | 28.3 | |

| PhD | 217 | 59.2 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Educational Major | IT | 136 | 37.1 |

| Management | 74 | 20.1 | |

| Accounting | 4 | 1.1 | |

| Medicine | 22 | 6 | |

| Pharmaceutical | 11 | 3 | |

| Other | 120 | 32.7 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Work Experience | Less than 2 years | 58 | 15.8 |

| 2 years - less than 6 years | 78 | 21.3 | |

| 6 years - less than 8 years | 25 | 6.8 | |

| 8 years - less than 10 years | 42 | 11.4 | |

| 10 years and above | 164 | 44.7 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| How long have you been using AI tools or apps? | Less than 6 months | 94 | 25.6 |

| 6 months - less than 1 year | 55 | 15 | |

| 1 year - less than 2 years | 48 | 13.1 | |

| 2 years and more | 170 | 46.3 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 | |

| Where do you most use your preferred AI tool (Type of operating system do you use)? | Windows PC | 269 | 73.3 |

| Mac OS (Mac Book) | 24 | 6.5 | |

| Android (Samsung, Sony, HTC, LG, Motorola…etc.) | 19 | 5.2 | |

| iOS (iPhone) | 46 | 12.5 | |

| Tablet | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Other | 7 | 1.9 | |

| Total | 367 | 100 |

| Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT | 274 | 74.7 |

| QuillBot | 135 | 36.8 |

| Grammarly | 248 | 67.6 |

| Scholarcy | 36 | 9.8 |

| Scite | 43 | 11.7 |

| pdf.ai | 68 | 18.5 |

| other | 24 | 6.5 |

| Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Conferences | 78 | 21.3 |

| Workshops | 108 | 29.4 |

| Training | 128 | 34.9 |

| All of the above | 83 | 22.6 |

| other | 69 | 18.8 |

| Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Application processes | 70 | 19.1 |

| Collaboration strategies | 56 | 15.3 |

| IT development plans | 85 | 23.2 |

| technical knowledge/skills | 97 | 26.4 |

| All of the above | 177 | 48.2 |

| other | 9 | 2.5 |

| Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Social attitudes about morals and ethical concerns | 97 | 26.4 |

| Offer guidelines for the development of AI applications | 71 | 19.3 |

| Protect privacy and Ownership rights | 123 | 33.5 |

| All of the above | 103 | 28.1 |

| Other | 48 | 13.1 |

| Category | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Supportive AI in-house software. | 89 | 24.3 |

| Adoptive operating systems that support AI. | 74 | 20.2 |

| Supportive AI in-house Network. | 75 | 20.4 |

| Not yet there, none of the above. | 175 | 47.7 |

| Other | 8 | 2.2 |

| Latent Variable | Indicator | FL | FLS | AVE (> 0.50) |

CR (> 0.70) |

Cronbach's Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compatibility | ||||||

| C1 | 0.82 | 0.672 |

0.585 |

0.875 |

||

| C2 | 0.663 | 0.440 | ||||

| C3 | 0.831 | 0.691 | 0.883 | |||

| C4 | 0.765 | 0.585 | ||||

| C5 | 0.732 | 0.536 | ||||

| Complexity | CX1 | 0.873 | 0.762 | 0.574 | 0.843 | |

| CX2 | 0.698 | 0.487 | ||||

| CX3 | 0.753 | 0.567 | 0.867 | |||

| CX4 | 0.694 | 0.482 | ||||

| User Interface | ||||||

| UX1 | 0.867 | 0.752 | 0.697 | 0.902 | ||

| UX2 | 0.839 | 0.704 |

0.938 |

|||

| UX3 | 0.848 | 0.719 | ||||

| UX4 | 0.784 |

0.615 |

||||

|

Ease of Use |

||||||

| PEOU1 | 0.874 | 0.764 | 0.585 | 0.807 | ||

| PEOU2 | 0.721 | 0.520 | 0.821 | |||

| PEOU3 | 0.687 | 0.472 | ||||

| User Satisfaction | US1 | 0.763 | 0.582 | 0.615 | 0.905 | |

| US2 | 0.721 | 0.520 | ||||

| US3 | 0.738 | 0.545 |

0.95 |

|||

| US4 | 0.865 | 0.748 | ||||

| US5 | 0.832 | 0.692 | ||||

| US6 | 0.778 |

0.605 |

||||

| Performance Expectation | PE1 | 0.757 | 0.573 | 0.664 | 0.855 | |

| PE2 | 0.811 | 0.658 | 0.881 | |||

| PE3 | 0.872 | 0.760 | ||||

| AI Strategic Alignment | AIS1 | 0.834 | 0.696 | 0.573 | 0.80 | |

| AIS2 | 0.757 | 0.573 | 0.835 | |||

| AIS3 | 0.671 | 0.450 | ||||

| Availability of Resources | AVR1 | 0.704 | 0.496 | |||

| AVR2 | 0.785 | 0.616 | 0.614 | 0.826 | 0.862 | |

| AVR3 | 0.854 | 0.729 | ||||

| Competitive Pressure | COP1 | 0.716 | 0.513 | 0.789 | ||

| COP2 | 0.765 | 0.585 | 0.555 | 0.817 | ||

| COP3 | 0.754 | 0.569 | ||||

| Government Regulations | GOR1 | 0.784 | 0.615 | |||

| GOR2 | 0.682 | 0.465 | 0.528 | 0.77 | 0.814 | |

| GOR3 | 0.711 | 0.506 | ||||

| Technological Support | TS1 | 0.621 | 0.386 | |||

| TS2 | 0.745 | 0.555 | 0.512 | 0.757 | 0.805 | |

| TS3 | 0.772 | 0.596 | ||||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | 0.857 | 0.734 | |||

| FC2 | 0.823 | 0.677 | 0.709 | 0.88 | 0.913 | |

| FC3 | 0.846 | 0.716 | ||||

| AI Adoption Intentions | AIA1 | 0.844 | 0.712 | 0.714 | 0.882 | |

| AIA2 | 0.856 | 0.733 | 0.929 | |||

| AIA3 | 0.834 | 0.696 | ||||

| Fl =Factor loading, FLS=Factor loading squared, AVE =Average Variance Extracted, CR= Composite Reliability | ||||||

| FL = Factor Loading, FLS = Factor Loading Squared, AVE= Average Variance Extracted, CR= Composite Reliability | ||||||

| X2 | 51.213 |

| X2 /DF | 5.12 |

| SRMR | 0.037 |

| CFI | 0.951 |

| TLI | 0.924 |

| NFI | 0.958 |

| IFI | 0.958 |

| RMSEA | 0.07 |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | C | → | AIA | 0.342 | 0.054 | 6.876 | *** | Not Supported |

| H1b | CX | → | AIA | 0.268 | 0.044 | 6.085 | *** | Supported |

| H1c | UX | → | AIA | 0.421 | 0.058 | 8.154 | *** | Not Supported |

| H1d | PEOU | → | AIA | 0.332 | 0.045 | 7.382 | *** | Supported |

| H1e | US | → | AIA | 0.216 | 0.046 | 4.672 | *** | Supported |

| H1f | PE | → | AIA | 0.186 | 0.043 | 4.312 | .001 | Supported |

| H1g | AINT | → | AIA | 0.766 | 0.033 | 23.519 | *** | Supported |

| H1h | AIS | → | AIA | 0.100 | 0.031 | 3.263 | .003 | Supported |

| H1i | AVR | → | AIA | 0.122 | 0.022 | 5.587 | *** | Supported |

| H1j | COP | → | AIA | 0.072 | 0.035 | 1.004 | .421 | Not Supported |

| H1k | GOR | → | AIA | 0.008 | 0.029 | 0.743 | .785 | Not Supported |

| H1l | TS | → | AIA | 0.551 | 0.034 | 8.581 | *** | Not Supported |

| H1m | FC | → | AIA | 0.964 | 0.039 | 25.000 | *** | Supported |

| Model | Structural weights |

|---|---|

| DF | 1 |

| CMIN | 0.455 |

| P | 0.491 |

| NFI Delta-1 | 0.002 |

| IFI Delta-2 | 0.002 |

| Model | Structural weights |

|---|---|

| DF | 2 |

| CMIN | 1.279 |

| P | 0.322 |

| NFI Delta-1 | 0.009 |

| IFI Delta-2 | 0.009 |

| Model | Structural weights |

|---|---|

| DF | 2 |

| CMIN | 4.624 |

| P | 0.099 |

| NFI Delta-1 | 0.017 |

| IFI Delta-2 | 0.017 |

| Model | Structural weights |

|---|---|

| DF | 4 |

| CMIN | 12.939 |

| P | 0.012 |

| NFI Delta-1 | 0.053 |

| IFI Delta-2 | 0.053 |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Effect | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Key Factors (IT) | → | AIA | 1.053 | .095 | 11.110 | *** | 0.692 | 0.479 |

| AI Key Factors (Management) | → | AIA | 1.576 | .201 | 7.829 | *** | 0.676 | 0.456 |

| AI Key Factors (Medicine) | → | AIA | .219 | .338 | .648 | .517 | 0.138 | 0.019 |

| AI Key Factors (Pharmaceutical) | → | AIA | 1.275 | .422 | 3.017 | .003 | 0.675 | 0.456 |

| AI Key Factors (Other) | → | AIA | 1.250 | .097 | 12.890 | *** | 0.764 | 0.584 |

| Model | Structural weights |

|---|---|

| DF | 4 |

| CMIN | 10.625 |

| P | 0.03 |

| NFI Delta-1 | 0.038 |

| IFI Delta-2 | 0.038 |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | Effect | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AI Key Factors (Less than 2 years) |

→ | AIA | .606 | .222 | 2.726 | .006 | 0.339 | 0.115 |

|

AI Key Factors (2 years - less than 6 years) |

→ | AIA | 1.136 | .145 | 7.839 | *** | 0.666 | 0.444 |

|

AI Key Factors (6 years - less than 8 years) |

→ | AIA | 1.481 | .273 | 5.429 | *** | 0.738 | 0.544 |

|

AI Key Factors (8 years - less than 10 years) |

→ | AIA | 1.366 | .098 | 13.886 | *** | 0.907 | 0.823 |

|

AI Key Factors (10 years and above) |

→ | AIA | 1.195 | .080 | 14.890 | *** | 0.760 | 0.578 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).