1. Introduction

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing higher education, fundamentally transforming traditional approaches to teaching, learning, and assessment (Deroncele-Acosta et al., 2024; Tzirides et al., 2024). Recent advances in AI technologies, particularly large language models and intelligent tutoring systems, have introduced unprecedented opportunities for creating personalized learning experiences, automating routine tasks, and fostering interactive learning environments across diverse academic disciplines(Davis, 2024; Li et al., 2024; Parambil et al., 2024; Xiao et al., 2024). While the adoption and impact of AI in STEM fields and language education have been extensively documented, its application and acceptance in humanities, specifically in history education, remain notably understudied (Ayeni et al., 2024).

History education presents unique pedagogical challenges and opportunities for AI integration. The discipline demands specialized cognitive skills, including critical analysis of primary sources, interpretation of complex historical narratives, and synthesis of multifaceted historical events(Mandell, 2008). Recent studies have demonstrated AI's potential to enhance these processes through automated document analysis, historical simulations, and advanced research assistance (Bertram et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2024). For example, Bertram et al.(2021) emphasized that AI tools can support students in efficiently handling historical documents, thereby deepening their understanding of complex events. Similarly, Kim et al. (2024) explored how AI aids students in mastering historical interpretation skills, helping them navigate the complexity of information.

However, empirical research examining students' acceptance and actual usage of AI tools in history education remains remarkably scarce. Yousuf and Wahid (2021) highlighted that while AI demonstrates a wide range of applications in education, its integration within specific disciplines, such as history education, still faces cultural and belief-based resistance. Additionally, Alfredo et al. (2024)) reviewed how AI can improve learning analytics within education, especially showing potential in the humanities.

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology ( UTAUT; Venkatesh et al., 2003) has emerged as a robust theoretical framework for understanding technology adoption in educational contexts (Xue et al., 2024). Through its core constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions—UTAUT explains up to 70% of variance in behavioral intention to use technology (Venkatesh et al., 2012). While numerous studies have successfully applied UTAUT to examine AI adoption in higher education generally (Budhathoki et al., 2024; Tatlı et al., 2024; Xue et al., 2024), its application within specific disciplinary contexts, particularly in humanities-based subjects like history, remains limited. This gap is significant because technology acceptance patterns may vary substantially across academic disciplines due to their distinct pedagogical requirements, learning objectives, and disciplinary cultures.

Two critical gaps emerge from the current literature. First, while research has established AI's potential in history education (Pope & Ma, 2024), there is limited empirical evidence regarding students' acceptance and actual use of AI tools in this specific context. Understanding these patterns is crucial for effective AI integration in history education, as student acceptance significantly influences the success of educational technology implementations. Second, although UTAUT has been validated across various educational technologies (Xue et al., 2024), its applicability in explaining AI adoption within humanities-based disciplines remains underexplored.

This study addresses these gaps through two primary objectives: (1) examining the factors influencing AI acceptance and use among higher education students in history education using the UTAUT framework, and (2) providing comparative evidence from the Malaysian higher education context. Malaysia offers a particularly interesting research context due to its rapid technological advancement in education, cultural diversity, and ongoing digital transformation initiatives in higher education, which may yield unique insights into technology acceptance patterns.

The significance of this study lies in both its theoretical and practical contributions. Theoretically, it extends UTAUT's application to the specific context of AI in history education, providing novel insights into how disciplinary context influences technology acceptance patterns. This extension enriches our understanding of technology adoption models in discipline-specific educational contexts. Practically, understanding the factors affecting AI adoption in history education can help educational institutions develop more effective strategies for integrating AI tools into humanities-based curricula, particularly in culturally diverse educational settings like Malaysia.

Furthermore, this research contributes to the broader discourse on digital transformation in humanities education. By examining AI acceptance in history education, the study provides valuable insights for educators and administrators seeking to enhance traditional humanities instruction through technological innovation while considering student acceptance factors. These insights are particularly timely given the increasing pressure on humanities departments to demonstrate their relevance and adaptability in an increasingly technology-driven educational landscape.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI in History Education (AIHEd)

While Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd) has matured into a well-established research domain, its integration and impact vary significantly across academic disciplines. AIEd encompasses the strategic implementation of AI technologies and methodologies to enhance teaching and learning processes, with the primary goal of delivering personalized, adaptive, and interactive educational experiences (Wang et al., 2024). Within this broader framework, Artificial Intelligence in History Education (AIHEd) represents a specialized application domain that leverages AI technologies to enhance historical inquiry, analysis, and understanding through multiple technological affordances, including automated document processing, historical simulations, and intelligent tutoring systems (Kumar et al., 2023).

Recent studies have begun to explore the potential of AI in history education. Sheng (2023) investigated AI's role in Chinese high schools' history education, highlighting how AI technologies could address the limitations of test-oriented education by promoting deeper learning and critical thinking. Similarly, Sevinch (2023) examined the integration of AI and virtual museums in history education, demonstrating how these technologies can create immersive learning experiences that enhance students' historical understanding.

The emergence of large language models has further expanded AIHEd's possibilities. Nguyen et al. (2023) compared ChatGPT's historical understanding with Vietnamese students' performance, revealing AI's potential in providing personalized assistance and enhancing critical thinking skills in history education. Similarly, Kim et al. (2024) developed a rule-based AI chatbot specifically for history education, demonstrating the feasibility of AI-powered tools for historical inquiry and learning.

Despite these advances, current research on AIHEd reveals several limitations. First, most studies focus on technological capabilities rather than user acceptance and adoption patterns. Second, while research demonstrates AI's potential benefits for history education, empirical evidence regarding student acceptance and actual usage remains limited. Third, existing studies primarily examine specific AI applications or tools, lacking a comprehensive framework for understanding technology acceptance in history education contexts.

2.2. UTAUT in Higher Education AI Adoption

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) is a robust model frequently used to examine technology acceptance in educational settings (Xue et al., 2024). Within higher education, the UTAUT model has provided valuable insights into how students and educators adopt new technologies, including AI, to enhance learning processes(Lu & Lin, 2024). Studies applying UTAUT in higher education consistently highlight performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions as critical determinants of technology adoption (Chatterjee & Bhattacharjee, 2020; Lu & Lin, 2024). These findings suggest that UTAUT can effectively capture the factors influencing AI adoption in specific academic fields, including the humanities-focused discipline of history, which has unique educational demands.

In contexts like Malaysia, where cultural values influence educational dynamics, understanding AI acceptance in history education requires careful consideration of UTAUT’ s core constructs. Dahri et al. (2024) investigated AI-based academic support tools in Malaysian and Pakistani institutions, finding that performance expectancy and social influence are particularly impactful in predicting student acceptance. These factors are highly relevant in Malaysian higher education, where peer and societal influences often play significant roles in shaping student attitudes toward technology adoption, especially in collaborative and interpretative fields like history.

Specific UTAUT applications to AI adoption in higher education further demonstrate the importance of this model’s constructs. Bilquise et al., (2024) explored student acceptance of academic advising chatbots and found that ease of use and social influence significantly predicted acceptance, aligning with UTAUT’s predictions. Similarly, Polyportis & Pahos (2024) applied UTAUT to understand ChatGPT adoption, identifying performance expectancy and effort expectancy as key determinants. These findings suggest that UTAUT’s constructs are applicable to history education, where students’ performance expectations of AI tools (e.g., for enhancing historical inquiry and document analysis) and the perceived ease of use may strongly influence adoption intentions.

Despite UTAUT’s successful application in analyzing AI adoption across educational disciplines, limited research has focused on its use within history education. Given that history education emphasizes critical thinking, source evaluation, and narrative interpretation, the role of AI tools in this context may diverge from more straightforward applications in STEM fields (Raffaghelli et al., 2022). By employing UTAUT, this study aims to bridge this gap, exploring how its constructs can help explain AI acceptance among Malaysian history students, specifically addressing how performance expectancy and facilitating conditions may shape their adoption behaviors.

Overall, UTAUT offers a structured approach to examining how students in Malaysian higher education perceive and engage with AI in history education. Understanding these factors can inform more effective AI tool integration, aligning with both the academic and cognitive needs of students in the humanities, thus enhancing the educational experience in history-focused AI applications.

3. Theoretical Framework, Research Model, and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Theoretical Framework

This study employs the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) as its theoretical foundation to investigate AI acceptance in history education within Malaysian higher education. The UTAUT model, developed through a comprehensive synthesis of eight prominent technology acceptance theories (Venkatesh et al., 2003), has demonstrated robust explanatory power, accounting for up to 70% of variance in behavioral intention across diverse technological contexts. Its theoretical robustness and extensive validation in educational technology research make it particularly suitable for examining the complex dynamics of AI adoption in discipline-specific educational settings.

The UTAUT framework posits four fundamental constructs that drive technology acceptance and use: Performance Expectancy (PE), Effort Expectancy (EE), Social Influence (SI), and Facilitating Conditions (FC). The model theorizes that PE, EE, and SI directly influence behavioral intention, while FC impacts actual use behavior. Additionally, the framework incorporates key moderating variables—age, gender, experience, and voluntariness—to account for individual differences in technology adoption patterns. This study specifically focuses on age and gender as moderators, given their demonstrated significance in educational technology acceptance within the Malaysian context (Krishanan & Khalidah, 2017; Toh et al., 2023).

3.2. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

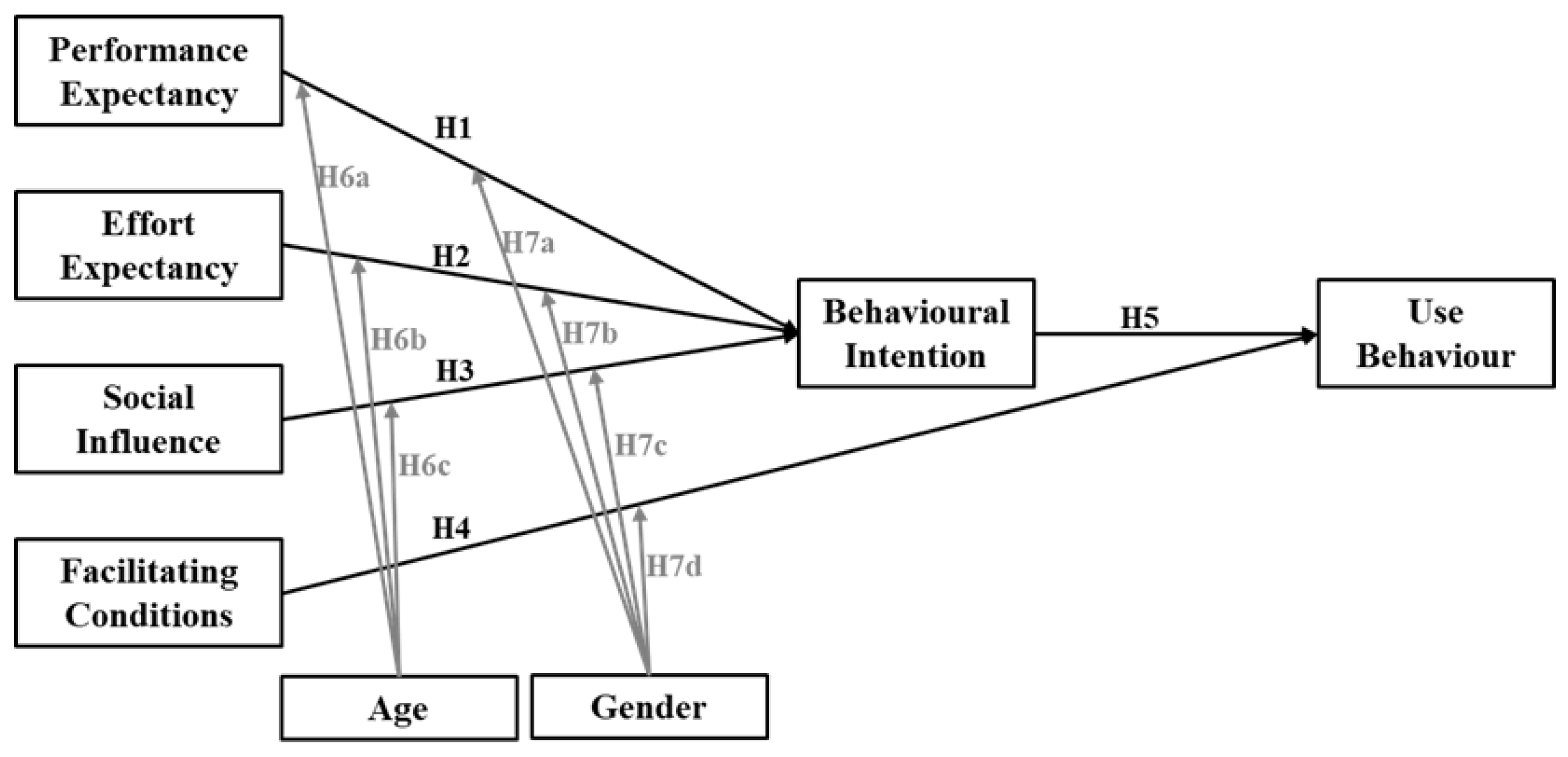

The research model presented in

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between constructs based on UTAUT, with age and gender moderating the specified relationships between the constructs.

Performance Expectancy represents students' perceptions regarding AI tools' utility in enhancing their academic performance in history education. In educational technology research, PE con-sistently emerges as the strongest predictor of behavioral intention (Williams et al., 2015; Xue et al., 2024). Within history education, AI tools offer distinct performance advantages through au-tomated document analysis, personalized learning pathways, and enhanced research capabilities. Recent empirical evidence suggests that students' perceptions of these performance benefits sig-nificantly influence their intention to adopt educational technologies (Dahri et al., 2024). There-fore, we hypothesize:

H1: Performance Expectancy positively influences students' behavioral intention to use AI in history education.

Effort Expectancy represents students' perceived ease of using AI tools in historical studies. In history education, this construct carries particular significance as students must integrate AI capabilities with established historical research methods, including source analysis and interpretative practices (Heng, 2023). Unlike standardized applications in quantitative disciplines, history education requires AI tools to support diverse analytical approaches while maintaining methodological rigor (Chatterjee & Bhattacharjee, 2020). Recent empirical evidence suggests that perceived ease of use significantly influences technology adoption, especially in humanities disciplines where students must balance technical competency with disciplinary expertise (Du & Lv, 2024). Within the Malaysian higher education context, where technological literacy varies among humanities students (Rana et al., 2024), the perceived cognitive accessibility of AI tools becomes crucial for adoption intentions.

H2: Effort Expectancy positively influences students' behavioral intention to use AI in history education

Social Influence reflects the extent to which students perceive those significant others—including faculty, peers, and family members—endorse their use of AI tools in historical studies. This construct's importance is amplified in Malaysian culture, which emphasizes collective decision-making and interpersonal relationships (Polyportis & Pahos, 2024). Recent studies demonstrate that social validation significantly affects technology adoption in educational contexts, particularly in disciplines where traditional teaching methods predominate (Chatterjee & Bhattacharjee, 2020). Therefore:

H3: Social Influence positively influences students' behavioral intention to use AI in history education.

Facilitating Conditions (FC)

Facilitating Conditions encompass students' perceptions of organizational and technical infrastructure supporting AI tool usage in history education. The UTAUT model posits that FC directly influences actual use behavior, as effective technology integration depends critically on supporting resources (Ajigini, 2022). In the context of AI-enhanced history education, these conditions include technical infrastructure, institutional support services, and accessibility of AI platforms. Research indicates that adequate facilitating conditions are essential for sustainable technology adoption in educational settings (Raffaghelli et al., 2022). Thus:

H4: Facilitating Conditions positively influence students' actual use behavior of AI in history education.

Behavioral Intention represents students' expressed commitment to utilize AI tools in their historical studies. Consistent with UTAUT's theoretical framework and empirical validation, behavioral intention serves as a direct antecedent to actual use behavior (O’Dea & O’Dea, 2023). Therefore:

H5: Behavioral Intention positively influences students' actual use behavior of AI in history education.

Age and gender represent critical moderating variables in technology acceptance research, particularly salient in educational contexts. Research indicates that age-related differences in technology self-efficacy and learning patterns significantly influence AI adoption behaviors (Binyamin et al., 2020). Similarly, gender-based variations in technology interaction preferences and social influence susceptibility have been documented in educational technology acceptance studies(Wong et al., 2012). Within Malaysian higher education, these demographic factors carry additional cultural significance, as studies have shown distinct age and gender patterns in technology engagement among humanities students(Ghazali et al., 2022).

Based on theoretical foundations and empirical evidence in educational technology acceptance, we propose:

Age Moderation: H6a-c: Age moderates the relationships between Performance Expectancy (H6a), Effort Expectancy (H6b), and Social Influence (H6c) with Behavioral Intention, such that these relationships are stronger for younger students.

Gender Moderation:H7a-d: Gender moderates the relationships between Performance Expectancy (H7a), Effort Expectancy (H7b), Social Influence (H7c) with Behavioral Intention, and between Facilitating Conditions and Use Behavior (H7d), with varying effects across gender groups.

This theoretical framework and associated hypotheses provide a structured approach to examining AI acceptance in history education within Malaysian higher education.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

This study employed a purposive sampling approach targeting undergraduate and postgraduate students majoring in history at four leading Malaysian universities. The selected institutions - University of Malaya (UM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Taylor's University Malaysia, and Sunway University - represent a mix of public and private higher education institutions, enhancing the sample's representativeness of the Malaysian higher education landscape. The data collection was conducted during the 2024-2025 academic year through an online survey platform. To ensure response quality and participant eligibility, several screening criteria were implemented: (1) participants must be currently enrolled in a history program, (2) have experience with or exposure to AI tools in their academic work, and (3) provide informed consent for participation. The questionnaire was administered in English, which is the primary medium of instruction in Malaysian higher education. 512 valid responses were received.

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the respondents. The sample shows a relatively balanced gender distribution (44.92% male, 55.08% female). The grade level distribution indicates comprehensive coverage across academic years, with undergraduate students comprising 92.58% and postgraduate students 7.42% of the sample. Age distribution reveals that the majority of respondents (53.32%) are below 21 years, followed by 21-year-olds (28.91%), and those above 22 years (17.77%), reflecting the typical age structure in Malaysian higher education institutions.

4.2. Survey Instrument

The survey instrument was developed based on validated scales from prior technology acceptance research, with items adapted to the context of AI usage in history education. All constructs were measured using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("Strongly disagree") to 7 ("Strongly agree"), except for Usage Behavior which employed a frequency-based scale. To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of experts in educational technology and pilot tested with 30 history student. Based on their feedback, minor modifications were made to improve item clarity and contextual relevance.

The measurement items for the core UTAUT constructs - Performance Expectancy (PE), Effort Expectancy (EE), Social Influence (SI), and Facilitating Conditions (FC) - were adapted from Venkatesh et al. (2012). Behavioral Intention (BI) items were adapted from Wu and Wu (2005), while Usage Behavior (UB) was measured using a single-item frequency scale following Venkatesh et al. (2012).

Table 2 presents the complete list of measurement items.

4.3. Data Analysis

To examine the hypothesized relationships within the proposed research model, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed using SmartPLS 4 software. PLS-SEM was selected due to its suitability for predictive and exploratory studies, particularly in contexts where theoretical models are extended with additional constructs or when data normality is not strictly assumed (Hair et al., 2021; Hair et al., 2011). Given the focus of this study on predicting students' behavioral intentions to adopt and use AI technology in history education, PLS-SEM's emphasis on maximizing explained variance aligns well with our research objectives.

The analysis commenced with an evaluation of the measurement model to ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs. This included an assessment of internal consistency reliability using composite reliability scores, indicator reliability via outer loadings, convergent validity through Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity employing both the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Hair et al., 2019). Each construct and its indicators were rigorously evaluated to confirm they met the recommended thresholds, ensuring the robustness of the measurement model.

Following the confirmation of construct reliability and validity, the structural model was assessed. This involved evaluating path coefficients for hypothesized relationships, R-squared (R²) values for endogenous variables, and predictive relevance (Q²) through the blindfolding procedure (Henseler et al., 2016). Bootstrapping (5,000 resamples) was conducted to determine the statistical significance of path coefficients. Effect sizes (f²) were also calculated to evaluate the magnitude of the relationships among constructs, enhancing the interpretive depth of the model's predictive capability.

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

Following established guidelines (Hair et al., 2019; Fornell & Larcker, 1981), we conducted a comprehensive assessment of the measurement model through examining convergent validity, internal consistency reliability, and discriminant validity.

Convergent validity was evaluated through factor loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). As shown in

Table 3, all indicator loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.704 to 0.902, demonstrating satisfactory indicator reliability ( Hair et al., 2019). The AVE values for all constructs surpassed the critical value of 0.50, ranging from 0.555 to 0.764, confirming adequate convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Internal consistency reliability was assessed using three criteria: Cronbach's alpha (α), composite reliability (ρc), and rho_A (ρA). All three reliability coefficients exceeded the threshold of 0.70, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.734 to 0.897, composite reliability from 0.833 to 0.928, and rho_A from 0.739 to 0.899, indicating robust internal consistency reliability (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

Additionally, the overall model fit was assessed through several indices. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value of 0.051 was below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating good model fit (Hair et al., 2017). The Normed Fit Index (NFI) value of 0.827, while slightly below the ideal threshold of 0.90, is still acceptable for exploratory research(Henseler et al., 2016).

Discriminant validity was evaluated using both the Fornell-Larcker criterion and heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). The Fornell-Larcker analysis (

Table 4) revealed that the square root of each construct's AVE (diagonal values) was greater than its correlations with other constructs, supporting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Additionally, all HTMT ratios (

Table 5) were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, ranging from 0.385 to 0.738, further confirming discriminant validity(Henseler et al., 2015).

Collectively, these results demonstrate that our measurement model exhibits satisfactory reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, providing a solid foundation for the structural model assessment.

5.2. Structural Model Assessment t

Following established guidelines for PLS-SEM analysis (Hair et al., 2017), we assessed the structural model through a systematic examination of collinearity, path coefficients, explanatory power (R²), effect sizes (f²), and predictive relevance (Q²).

The evaluation of collinearity among predictor constructs was conducted using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). As shown in

Table 6, all inner VIF values ranged from 1.026 to 3.133, well below the threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2017), indicating that collinearity does not reach critical levels in the structural model.

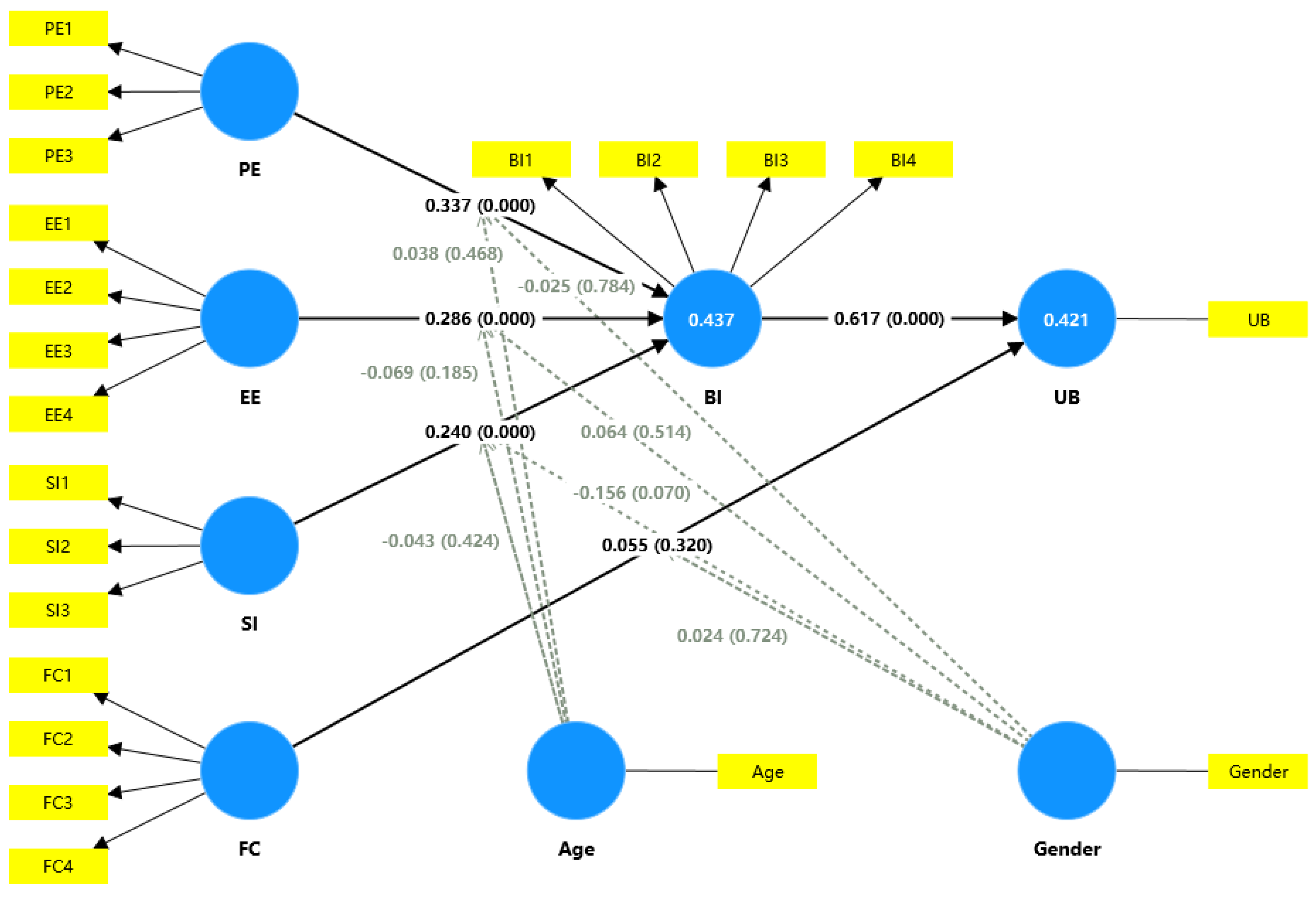

The significance of path coefficients was evaluated through bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 7 presents the results of hypotheses testing. Performance expectancy exhibited the strongest effect on behavioral intention (β = 0.337, t = 4.806, p < 0.001, f² = 0.073), followed by effort expectancy (β = 0.286, t = 3.712, p < 0.001, f² = 0.006) and social influence (β = 0.240, t = 3.600, p < 0.001, f² = 0.036), supporting H1, H2, and H3 respectively. While behavioral intention showed a strong positive effect on usage behavior (β = 0.617, t = 15.213, p < 0.001, f² = 0.527), supporting H5, the relationship between facilitating conditions and usage behavior was not significant (β = 0.055, t = 0.995, p > 0.05), thus H4 was not supported.

The hypothesized moderating effects of age and gender (H6 and H7) were tested but found to be non-significant, as illustrated in Figure 8, indicating that the relationships between the main constructs remain consistent across demographic groups.

The coefficient of determination (R²) values indicate that the model explains 43.7% of the variance in behavioral intention and 42.1% in usage behavior (

Table 8). According to Hair et al. (2019), these R² values represent moderate explanatory power. The model's predictive relevance was assessed using the blindfolding procedure (Hair et al., 2017). The resulting Q² values for behavioral intention (0.294) and usage behavior (0.409) were substantially above zero, confirming the model's predictive relevance.

6. Discussion

6.1. Main Effects of UTAUT Constructs

Performance expectancy emerged as the strongest predictor of behavioral intention (β = 0.337, p < 0.001), consistent with prior UTAUT research in higher education contexts (García-Murillo et al., 2023). This finding aligns with Bertram et al.'s (2021) observation that AI tools significantly support students in handling historical documents and deepening their understanding of complex historical events. The result suggests that history students primarily value AI tools for their potential to enhance academic performance, particularly in areas such as document analysis and historical research assistance (Kim et al., 2024).

Effort expectancy demonstrated the second strongest effect on behavioral intention (β = 0.286, p < 0.001), highlighting the importance of user-friendly AI interfaces. This finding supports Sheng's (2023) argument that history students must effectively integrate AI capabilities with established historical research methods. The significant impact of effort expectancy suggests that perceived ease of use remains crucial for AI adoption in humanities disciplines, where students must balance technical competency with disciplinary expertise (Du & Lv, 2024).

Social influence showed a significant positive effect on behavioral intention (β = 0.240, p < 0.001), reflecting the collective nature of technology acceptance decisions in Malaysian culture (Polyportis & Pahos, 2024). This finding aligns with research highlighting the importance of peer and faculty influence in shaping students' technology adoption behaviors in Malaysian higher education (Dahri et al., 2024).

Surprisingly, facilitating conditions did not significantly influence usage behavior (β = 0.055, p > 0.05), contradicting previous findings in educational technology adoption research (Ajigini, 2022). This unexpected result might be attributed to the increasing accessibility of AI tools through personal devices and cloud-based platforms, potentially reducing students' dependence on institutional infrastructure.

6.2. Demographic Considerations

Contrary to our hypotheses, neither age nor gender exhibited significant moderating effects on the relationships between UTAUT constructs. This finding diverges from previous studies that found demographic differences in technology acceptance patterns (Binyamin et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2012) . The absence of moderating effects suggests that AI acceptance in history education transcends demographic boundaries, possibly due to the widespread exposure to digital technologies among contemporary students.

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our research extends UTAUT's application to AI in history education, contributing to technology acceptance theory in several ways. First, it demonstrates UTAUT's robustness in humanities-based disciplines, with the model explaining 43.7% of variance in behavioral intention. Second, the non-significant effect of facilitating conditions suggests an evolution in how institutional support influences technology adoption in the era of cloud-based AI tools. Third, the absence of demographic moderating effects indicates a possible convergence in technology acceptance patterns among modern students.

Our findings offer several practical implications for educators and institutions implementing AI in history education. Given the strong influence of performance expectancy, implementation strategies should highlight concrete benefits for historical research and analysis tasks. Educational institutions should demonstrate how AI tools can enhance specific history-related activities such as document analysis, source verification, and historical pattern recognition. The significant role of effort expectancy underscores the need for user-friendly AI interfaces that align with historical research methodologies. Institutions should invest in AI tools that integrate seamlessly with existing historical research practices while providing clear instruction and support materials. Furthermore, the importance of social influence suggests that peer learning programs and faculty endorsement can effectively promote AI adoption. While facilitating conditions showed non-significant effects, institutions should maintain support systems that address discipline-specific needs in history education, ensuring that technical infrastructure and support services remain accessible to all students.

7. Conclusion

This study makes several significant contributions to understanding AI acceptance in history education. First, it validates UTAUT's applicability in humanities-based disciplines, providing a theoretical framework for future research in this domain. Second, it offers practical insights for educational institutions seeking to integrate AI tools into history education effectively. Third, it highlights the evolving nature of technology acceptance patterns among contemporary students, where traditional demographic distinctions may be less relevant.

Despite these contributions, several limitations suggest directions for future research. The cross-sectional design limits understanding of how AI acceptance evolves over time, suggesting the need for longitudinal studies. The focus on Malaysian universities may affect generalizability to other cultural contexts, indicating opportunities for cross-cultural comparative studies. Future research could explore discipline-specific variables such as historical thinking skills and disciplinary identity, as well as investigating the relationship between AI acceptance and learning outcomes in history education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W.; methodology, F.W.; software, F.W.; validation, F.W. and X.S.; formal analysis, F.W.; investigation, F.W. and X.S.; resources, F.W.; data curation, F.W. and X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.W.; writing—review and editing, F.W.; visualization, F.W.; supervision, F.W.; project administration, F.W.; funding acquisition, F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it was conducted as part of routine educational assessment and improvement efforts, with all data collected anonymously and no sensitive personal information involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns as they contain sensitive information from the survey participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in this study and the administrative staff from the participating Malaysian universities for their assistance in facilitating the survey distribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ajigini, O. A. (2022). Factors Influencing the Acceptance and Use of Internet of Things by Universities. INFORMATION RESOURCES MANAGEMENT JOURNAL, 35(1). [CrossRef]

- Alfredo, R., Echeverria, V., Jin, Y., Yan, L., Swiecki, Z., Gašević, D., & Martinez-Maldonado, R. (2024). Human-centred learning analytics and AI in education: A systematic literature review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100215. [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, O. O., Hamad, N. M. A., Chisom, O. N., Osawaru, B., Adewusi, O. E., Ayeni, O. O., Hamad, N. M. A., Chisom, O. N., Osawaru, B., & Adewusi, O. E. (2024). AI in education: A review of personalized learning and educational technology. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews, 18(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C., Weiss, Z., Zachrich, L., & Ziai, R. (2021). Artificial intelligence in history education. Linguistic content and complexity analyses of student writings in the CAHisT project (Computational assessment of historical thinking). Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 100038. [CrossRef]

- Bilquise, G., Ibrahim, S., & Salhieh, S. (2024). Investigating student acceptance of an academic advising chatbot in higher education institutions. EDUCATION AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES, 29(5), 6357–6382. 5). [CrossRef]

- Binyamin, S. S., Rutter, M. J., & Smith, S. (2020). The moderating effect of gender and age on the students’ acceptance of learning management systems in Saudi higher education. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 12(1), 30–62. [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, T., Zirar, A., Njoya, E. T., & Timsina, A. (2024). ChatGPT adoption and anxiety: A cross-country analysis utilising the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). Studies in Higher Education, 49(5), 831–846. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., & Bhattacharjee, K. (2020). Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: A quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. EDUCATION AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES, 25(5), 3443–3463. [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N. A., Yahaya, N., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Vighio, M. S., Alblehai, F., Soomro, R. B., & Shutaleva, A. (2024). Investigating AI-based academic support acceptance and its impact on students’ performance in Malaysian and Pakistani higher education institutions. EDUCATION AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES, 29(14), 18695–18744. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A. J. (2024). AI rising in higher education: Opportunities, risks and limitations. Asian Education and Development Studies, 13(4), 307–319. [CrossRef]

- Deroncele-Acosta, A., Bellido-Valdiviezo, O., Sánchez-Trujillo, M. de los Á., Palacios-Núñez, M. L., Rueda-Garcés, H., & Brito-Garcías, J. G. (2024). Ten Essential Pillars in Artificial Intelligence for University Science Education: A Scoping Review. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241272016. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26628355.

- Du, L., & Lv, B. (2024). Factors influencing students’ acceptance and use generative artificial intelligence in elementary education: An expansion of the UTAUT model. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- García-Murillo, G., Novoa-Hernández, P., & Serrano Rodríguez, R. (2023). On the Technological Acceptance of Moodle by Higher Education Faculty—A Nationwide Study Based on UTAUT2. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N., Damia, F., Nasir, M., & Nordin, M. (2022). Moderating Effect of Gender between MOOC-efficacy and Meaningful Learning. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Moderating-Effect-of-Gender-between-MOOC-efficacy-Ghazali-Damia/27d170b71f1c8cd761ad524d7720dc026ccc27c3.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (Third edition). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Heng, W. N. (2023). Adoption of AI technology in education among UTAR students: The case of Chatgpt.

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-J., Kim, N.-H., Kim, D.-H., Kim, H.-J., & Koh, S.-J. (2024). A Study on History Education with Rule-Based Artificial Intelligence Chatbot. Proceedings of the Korea Information Processing Society Conference, 619–620. [CrossRef]

- Krishanan, D., & Khalidah, S. (2017). MODERATING EFFECTS OF AGE & EDUCATION ON CONSUMERS’ PERCEIVED INTERACTIVITY & INTENTION TO USE MOBILE BANKING IN MALAYSIA: A STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING APPROACH. 1(3).

- Kumar, D., Haque, A., Mishra, K., Islam, F., Kumar Mishra, B., & Ahmad, S. (2023). Exploring the Transformative Role of Artificial Intelligence and Metaverse in Education: A Comprehensive Review. Metaverse Basic and Applied Research, 2, 55. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Yu, F., & Zhang, E. (2024). A systematic review of learning task design for K-12 AI education: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100217. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., & Lin, C. (2024). Meta-Analysis of Influencing Factors on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Education. ASIA-PACIFIC EDUCATION RESEARCHER. [CrossRef]

- Mandell, N. (2008). Thinking like a Historian: A Framework for Teaching and Learning. OAH Magazine of History, 22(2), 55–59. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.-H., Nguyen, H.-A., Cao, L., & Hana, T. (2023). ChatGPT’s Understanding of History A Comparison to Vietnamese Students and its Potential in History Education. OSF. [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, X., & O’Dea, M. (2023). Is Artificial Intelligence Really the Next Big Thing in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education? A Conceptual Paper. JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITY TEACHING AND LEARNING PRACTICE, 20(5), 05. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/a52b8c7a-4b07-4603-8685-335056e0182b-0122ce1838/relevance/1.

- Parambil, M. M. A., Rustamov, J., Ahmed, S. G., Rustamov, Z., Awad, A. I., Zaki, N., & Alnajjar, F. (2024). Integrating AI-based and conventional cybersecurity measures into online higher education settings: Challenges, opportunities, and prospects. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100327. [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A., & Pahos, N. (2024). Understanding students’ adoption of the ChatGPT chatbot in higher education: The role of anthropomorphism, trust, design novelty and institutional policy. BEHAVIOUR & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY. [CrossRef]

- Pope, A., & Ma, R. (2024). Exploring Historians’ Critical Use of Generative AI Technologies for History Education. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 61(1), 1071–1073. [CrossRef]

- Raffaghelli, J. E., Elena Rodriguez, M., Guerrero-Roldan, A.-E., & Baneres, D. (2022). Applying the UTAUT model to explain the students’ acceptance of an early warning system in Higher Education. COMPUTERS & EDUCATION, 182, 104468. [CrossRef]

- Rana, M. M., Siddiqee, M. S., Sakib, M. N., & Ahamed, M. R. (2024). Assessing AI adoption in developing country academia: A trust and privacy-augmented UTAUT framework. HELIYON, 10(18), e37569. [CrossRef]

- Sevinch, T. (2023). THE ROLE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND VIRTUAL MUSEUMS IN HISTORY EDUCATION. Raqamli Iqtisodiyot (Цифрoвая Экoнoмика), 5, Article 5. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/the-role-of-artificial-intelligence-and-virtual-museums-in-history-education.

- Sheng, X. (2023). The Role of Artificial Intelligence in History Education of Chinese High Schools. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 8, 238–243. https://doi.org/10.54097/ehss.v8i.4255. [CrossRef]

- Tatlı, H. S., Bıyıkbeyi, T., Gençer Çelik, G., & Öngel, G. (2024). Paperless Technologies in Universities: Examination in Terms of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Sustainability, 16(7), Article 7. [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.-Y., Ng, S.-A., & Phoon, S.-T. (2023). Accentuating technology acceptance among academicians: A conservation of resource perspective in the Malaysian context. Education and Information Technologies, 28(3), 2529–2545. [CrossRef]

- Tzirides, A. O. (Olnancy), Zapata, G., Kastania, N. P., Saini, A. K., Castro, V., Ismael, S. A., You, Y., Santos, T. A. dos, Searsmith, D., O’Brien, C., Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2024). Combining human and artificial intelligence for enhanced AI literacy in higher education. Computers and Education Open, 6, 100184. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu. (2012). Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Wang, F., Zhu, Z., Wang, J., Tran, T., & Du, Z. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review. Expert Systems with Applications, 252, 124167. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. D., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2015). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 28(3), 443–488. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.-T., Teo, T., & Russo, S. (2012). Influence of gender and computer teaching efficacy on computer acceptance among Malaysian student teachers: An extended technology acceptance model. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28, 1190–1207. [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L., & Wu, K.-W. (2005). A hybrid technology acceptance approach for exploring e-CRM adoption in organizations. Behaviour & Information Technology, 24(4), 303–316. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Zhang, T., & He, J. (2024). The promises and challenges of AI-based chatbots in language education through the lens of learner emotions. Heliyon, 10(18), e37238. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L., Rashid, A. M., & Ouyang, S. (2024). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Sage Open, 14(1), 21582440241229570. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, M., & Wahid, A. (2021). The role of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Current Trends and Future Prospects. 2021 International Conference on Information Science and Communications Technologies (ICISCT), 1–7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements,opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas,methods,instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).