1. Introduction

Academic writing plays an important role in university education, but many students still find it difficult, especially when writing in a foreign language. With the emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools (such as ChatGPT), students now have new forms of support in their academic writing process (Aljanabi et al., 2023; Johnston et al., 2024; Mahapatra, 2024). However, the growing integration of GAI into academic writing also brings new challenges for university English instructors, especially in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts. On the one hand, GAI can support EFL students’ learning and improve their writing quality (Imran & Almusharraf, 2023; Sok, & Heng, 2023); on the other hand, it may lead to over-reliance, misuse, or even academic misconduct, potentially hindering the development of students’ own writing competence and language skills (Azeem & Abbas; 2025; Bittle & El-Gayar, 2025). As students begin to rely more on these tools, understanding the factors that shape students’ intention and actual use of GAI is therefore essential for informing instructional strategies and institutional policies.

While current research has discussed the general benefits and challenges of GAI in education (Batista et al., 2024; Bond et al., 2024; Chan & Hu, 2023), few studies have focused on its use in academic writing in EFL contexts. To better understand students’ behavior in this area, this study applies and extends the UTAUT framework (Venkatesh et al., 2003) by adding three new factors: trust in GAI (students’ confidence in the reliability and fairness of AI-generated content) (Nazaretsky et al., 2025), ethical artificial intelligence (AI) literacy (students’ ability to understand and apply ethical principles when using AI) (Long & Magerko, 2020), and academic integrity assurance (students’ belief that using GAI can align with academic honesty and institutional policies) (Lubis et al., 2024).

The research aims to answer the following questions:

What factors influence students’ intention to use GAI tools in academic writing?

Does students’ intention to use lead to their actual use of GAI tools?

Do demographic variables moderate the relationships among the key paths in the model?

By addressing these questions, this study aims to expand the understanding factors affecting students’ adoption of GAI tools for academic writing and provide useful insights for teachers, universities, and policymakers seeking to guide students in using AI tools in appropriate ways.

2. Literature Review

2.1. GAI in Academic Writing

GAI has become an increasingly prominent tool in higher education, particularly in the domain of academic writing. GAI tools offer support across various stages of the writing process, including idea generation, language refinement, content organization, and revision (Jacob et al., 2025; Khalifa & Albadawy, 2024). Their capacity to provide immediate and personalized feedback makes them attractive resources for students facing the demands of university-level writing. Surveys show that approximately one-third of university students report using GAI to support coursework, often in writing-intensive subjects (Intelligent, 2023). While this reflects the growing perceived usefulness of GAI, it also raises pedagogical and ethical concerns, including overreliance, reduced learner agency, and potential violations of academic integrity (Bittle & El-Gayar, 2025).

Recent studies suggest that understanding GAI’s role in academic writing requires attention to both technological and psychological factors (e.g., Jacob et al., 2023). In particular, students’ beliefs about the usefulness of GAI, their confidence in their own writing abilities, their awareness of the limitations of AI-generated content, and their attitudes toward academic honesty are likely to influence how they adopt and apply such tools in academic contexts.

A number of studies have begun to explore the potential of GAI in academic writing. For instance, Khampusaen (2025) conducted a 16-week mixed-methods study with Thai EFL students, finding that ChatGPT integration significantly improved argumentative structure, evidence use, and academic voice across successive drafts. Li et al. (2024) compared ChatGPT (versions 3.5 and 4) and human raters on Chinese EFL essays, concluding that AI feedback matched or exceeded teacher feedback in areas like content organization and language quality. Jacob et al., (2023)’s study demonstrated that students used ChatGPT throughout the writing process—brainstorming, drafting, and revising—while maintaining their own voice. Finally, a mixed-methods study by Apriani et al. (2025) reported that 14 ChatGPT-guided writing sessions significantly raised academic writing scores for Indonesian undergraduates, with students endorsing gains in idea generation and structure.

However, ethical factors have received limited scholarly attention, despite their potential influence on students’ intentions to use GAI (Chanpradit, 2025). In this context, students’ ethical AI literacy—the ability to understand, use, monitor, and critically reflect on AI outputs (Long & Magerko, 2020)—and academic integrity assurance—such as clear AI-use policies, training, and enforcement (Lubis et al., 2024)—may predict students’ intention to use AI. Another psychological factor relevant to GAI usage in academic writing is trust in GAI—the degree to which students believe that generative AI tools are reliable, accurate, and beneficial for their academic tasks (Nazaretsky et al., 2025). Higher levels of trust may increase students’ willingness to use GAI tools.

2.2. UTAUT

The UTAUT framework, proposed by Venkatesh et al. (2003), is a widely used model for explaining individuals’ acceptance and use of new technologies. The framework identifies four key constructs that influence behavioral intention and usage behavior: performance expectancy (the degree to which using a technology is perceived to improve task performance), effort expectancy (the perceived ease of use), social influence (the perceived pressure from others to use the technology), and facilitating conditions (the availability of resources and support for using the technology). UTAUT has been applied across various fields, especially in education (Soares et al., 2025; Xue et al., 2024), to understand how users adopt technological tools in different learning contexts.

However, as the use of GAI in academic writing involves not only technological but also cognitive and ethical dimensions, the original UTAUT framework may be insufficient to fully capture the complexity of students’ decision-making processes. Therefore, this study extends the UTAUT model by incorporating three additional constructs: trust in GAI, ethical AI literacy, and academic integrity assurance. By integrating these factors, the study aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological influences on students’ GAI usage intention and behavior in academic writing.

2.3. Theoretical Model and Hypothesis Development

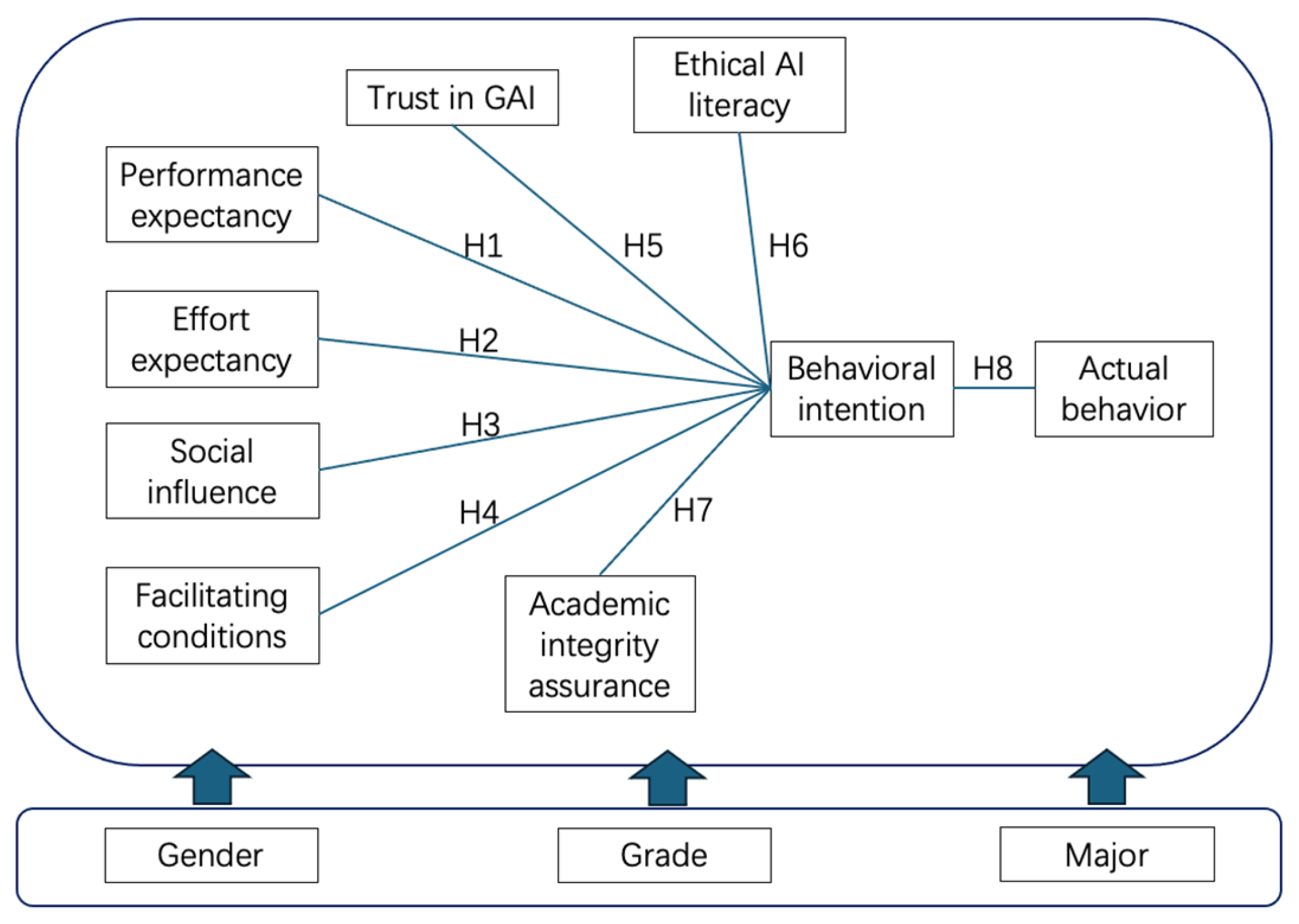

Building upon prior research, this study employs an extended UTAUT model to investigate the factors shaping university students’ adoption of GAI tools in academic writing. In addition to the model’s four core constructs, this study incorporates three writing-specific psychological variables: trust in GAI, ethical AI literacy, and academic integrity assurance (see

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Performance Expectancy (PE)

Performance expectancy (PE) refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular technology will enhance their performance in completing tasks (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the context of academic writing, PE reflects students’ perceptions of how GAI tools—such as ChatGPT—can improve the quality, efficiency, and clarity of their writing outputs. In this study, PE is hypothesized to be a key predictor of students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools for academic writing tasks. The stronger the belief that GAI will help them perform better in writing, the more likely students are to adopt and rely on such tools in their academic work. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Performance expectancy has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.2. Effort Expectancy (EE)

Effort expectancy (EE) refers to the degree to which individuals perceive a technology as easy to use (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the context of academic writing, it captures how simple and user-friendly students find GAI tools during academic writing process. Students are more likely to adopt technologies that they perceive as requiring minimal effort to learn and operate. When GAI tools offer intuitive interfaces, clear outputs, and accessible features, students may feel more confident and willing to use them in their academic writing processes. Previous research has confirmed that ease of use is a significant factor influencing students’ behavioral intention in adopting educational technologies (Xue et al., 2024). In this study, EE is hypothesized to positively influence students’ intention to use GAI tools in academic writing. The easier students perceive these tools to be, the more likely they are to incorporate them into their writing practices. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2. Effort expectancy has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.3. Social Influence (SI)

Social influence (SI) refers to the degree to which individuals perceive that important others—such as peers—believe they should use a particular technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the context of GAI in academic writing, SI reflects the extent to which students’ decisions to adopt tools like ChatGPT are shaped by the opinions and behaviors of those around them. Prior research has shown that SI plays a significant role in shaping technology adoption (Abbad, 2021). In this study, SI is expected to positively predict students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools in completing academic writing tasks. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Social influence has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.4. Facilitating Conditions (FC)

Facilitating conditions (FC) refer to the extent to which individuals perceive that technical and institutional resources are available to support their use of a given technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In the context of academic writing with GAI, FC includes access to reliable internet, appropriate devices, platform availability, and institutional guidance on the use of GAI tools. In this study, FC is considered a contributing factor that supports students’ use of GAI tools in academic writing and is expected to positively influence both behavioral intention and actual usage behavior. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4. Facilitating conditions have a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.5. Trust in GAI (TGAI)

Trust in GAI refers to students’ confidence in the reliability, fairness, and transparency of generative AI tools used in academic writing (Nazaretsky et al., 2025). In this context, students with higher trust in GAI are more likely to engage with such tools in a balanced and strategic manner—for example, using AI to support grammar refinement, structural clarity, or idea generation while maintaining academic integrity. In contrast, students with low trust may avoid using GAI altogether due to concerns about bias, inaccuracy, or ethical risks. Prior studies in educational technology have shown that trust plays a critical role in shaping students’ technology adoption behaviors, especially when the tool involves complex or opaque algorithmic processes (Shin, 2021; Nazaretsky et al., 2025). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Trust in GAI has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention of GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.6. Ethical AI literacy (EAIL)

Ethical AI literacy refers to students’ capacity to understand, evaluate, and apply ethical principles when using generative AI tools in academic contexts (Zou & Schiebinger, 2018; Long & Magerko, 2020). Rather than merely recognizing potential risks, students with high ethical AI literacy are equipped to make informed, responsible decisions about when and how to use AI. This includes the ability to identify biases or misinformation, to judge the appropriateness of using AI-generated content, and to align its use with institutional policies and academic integrity standards. In the context of academic writing, ethical AI literacy enables students to treat GAI tools as supplements that enhance—rather than replace—their original thinking and writing. Prior research shows that ethically informed digital literacy promotes more constructive and intentional engagement with technology (Long & Magerko, 2020). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6. Ethical AI literacy has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention of GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.7. Academic Integrity Assurance (AIA)

Academic integrity assurance refers to students’ belief that the use of generative AI tools in academic writing aligns with ethical standards, institutional policies, and principles of academic honesty (Espinoza et al., 2024). Rather than viewing GAI use as inherently risky or unethical, students with high academic integrity assurance perceive it as a legitimate support tool when used appropriately. This perception may increase their confidence and willingness to engage with such technologies. As a result, academic integrity assurance is expected to positively influence students’ behavioral intention to use GAI tools. Therefore, in the current study it was hypothesized that:

H7. Academic integrity assurance has a significant positive effect on university students’ behavioral intention of GAI tools in academic writing.

2.3.8. Behavioral Intention (BI)

Behavioral intention reflects the degree to which an individual is inclined to adopt and engage with a particular technology (Venkatesh et al., 2003). It functions as a key antecedent of actual usage, mediating the influence of various cognitive and contextual factors. In the context of GAI, it represents university students’ willingness or readiness to incorporate GAI tools into their academic learning practices. Prior research consistently demonstrates that stronger behavioral intention leads to higher levels of actual use (Amid & Din, 2021; Chao, 2019). Based on this, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H8. University students’ behavioral intention positively and significantly influences their actual use of GAI tools.

2.3.9. Moderating Variables

To better understand potential differences in GAI usage patterns, this study incorporates gender, grade level, and academic major as moderating variables. These demographic characteristics may influence how students apply GAI tools in academic writing, thereby affecting the strength or direction of the hypothesized relationships (Strzelecki & El-Arabawy, 2024; Xu et al., 2025).

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a quantitative research design to investigate the factors influencing university students’ use of GAI tools in completing academic writing tasks. A structured questionnaire (see

Appendix A) was developed based on the extended UTAUT framework and supplemented with three new constructs, drawing upon relevant literature.

Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from the Peking University Institutional Review Board. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained electronically.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire consisted of two main sections. The first section gathered demographic information, including participants’ gender, grade, and academic major. The second section focused on factors influencing university students’ use of GAI tools in academic writing. It incorporated both four core constructs from UTAUT framework (Venkatesh et al., 2003) and the three additional constructs relevant to ethical aspects of academic writing (Pintrich et al., 1993; Ramdani, 2018; Wang et al., 2025). All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater agreement. A total of 26 items were retained after preliminary validation and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Demographic variables such as gender, grade, and major were included as potential moderators in the model.

3.2. Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed to undergraduate students from three comprehensive universities in Beijing via a public online survey platform. A total of 1,479 responses were received. After initial screening, responses with patterns suggesting inattentive answering (e.g., excessive straight-lining or identical answers) were excluded following established data-cleaning procedures (Meade & Craig, 2012). As a result, 1400 valid responses were retained, yielding a valid response rate of 94.66%.

Of the 1,400 participants, 707 were male (50.50%) and 693 were female (49.50%). The sample covered a broad distribution across academic years: 346 first-year students (24.71%), 348 second-year students (24.86%), 304 third-year students (21.71%), 342 fourth-year students (24.43%), and 60 fifth-year students (4.29%). In terms of academic disciplines, 248 students majored in Medicine and Health (17.71%), 242 in Humanities and Social Sciences (17.29%), 241 in Education and Psychology (17.21%), 240 in Science and Engineering (17.14%), 222 in Business and Economics (15.86%), and 207 in Information Technology (14.79%).

Table 1 presents the demographic information of students.

3.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first conducted to summarize the demographic characteristics and to examine the distribution of responses across the latent variables. To assess the reliability of the constructs, Cronbach’s α was calculated for each multi-item scale, with a threshold value of 0.70 indicating acceptable internal consistency (Hair et al., 2010). Convergent validity was evaluated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE), with CR > 0.7 and AVE > 0.5 considered acceptable.

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of the AVE values for each construct with the inter-construct correlations. Discriminant validity was deemed satisfactory when each construct’s AVE exceeded the squared correlations with other constructs. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR).

After validation of the measurement model, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized relationships among the constructs, using AMOS 26.0. In addition, multi-group analysis was conducted to explore the potential moderating effects of demographic variables (e.g., gender, academic year, and major) on students’ generative AI usage behavior in academic writing. The explanatory power of the final structural model was examined through the squared multiple correlations (R²) of the outcome variables.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

SPSS 30.0 and AMOS 26.0 were used to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first conducted to examine the underlying structure of the scale. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.744 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating sampling adequacy and the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The total variance explained by the extracted factors reached 55.06%, suggesting that the factor structure accounts for a substantial proportion of the variability in the observed data and demonstrates acceptable construct validity.

To further validate the structure, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. The model fit indices demonstrated acceptable overall model fit: χ²/df = 3.17 (<5), RMSEA = 0.085, SRMR = 0.047, CFI = 0.841, and TLI = 0.802. All standardized factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.85 to 0.91, confirming satisfactory item reliability.

Convergent validity was supported by the values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE), all of which exceeded 0.5, and Composite Reliability (CR), which ranged from 0.91 to 0.92 (see

Table 2). The internal consistency of the scale was also confirmed. The α values for each construct ranged from 0.733 to 0.841, where all of them are above the 0.7 threshold. The means of the constructs were all above 3.0, and the standard deviations ranged from 0.53 to 0.57, indicating acceptable variability.

Discriminant validity was verified by comparing the square roots of AVE values with inter-construct correlations, all of which met the Fornell-Larcker criterion (see

Table 3). The diagonal values represent the square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (√AVE) for each construct, indicating the degree of convergent validity within each construct. The off-diagonal values represent the Pearson correlation coefficients between constructs, reflecting the extent of inter-construct relationships.

Interestingly, the correlations among the four core constructs of the UTAUT model (PE, EE, SI, FC) were either negligible or slightly negative, though none were statistically or practically significant. This pattern suggests that these constructs, while theoretically distinct, may be perceived independently by students in the context of GAI use in academic writing. Such low correlations also support the discriminant validity of the constructs.

Additionally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios were all below the recommended threshold of 0.9, further supporting discriminant validity (see

Table 4).

4. Results

4.1. Structural Model

The study evaluated university students’ acceptance of GAI in academic writing tasks by examining the effects of PE, EE, SI, FC, TGAI, EAIL and AIA on BI. Additionally, the influence of BI on UB was also analyzed.

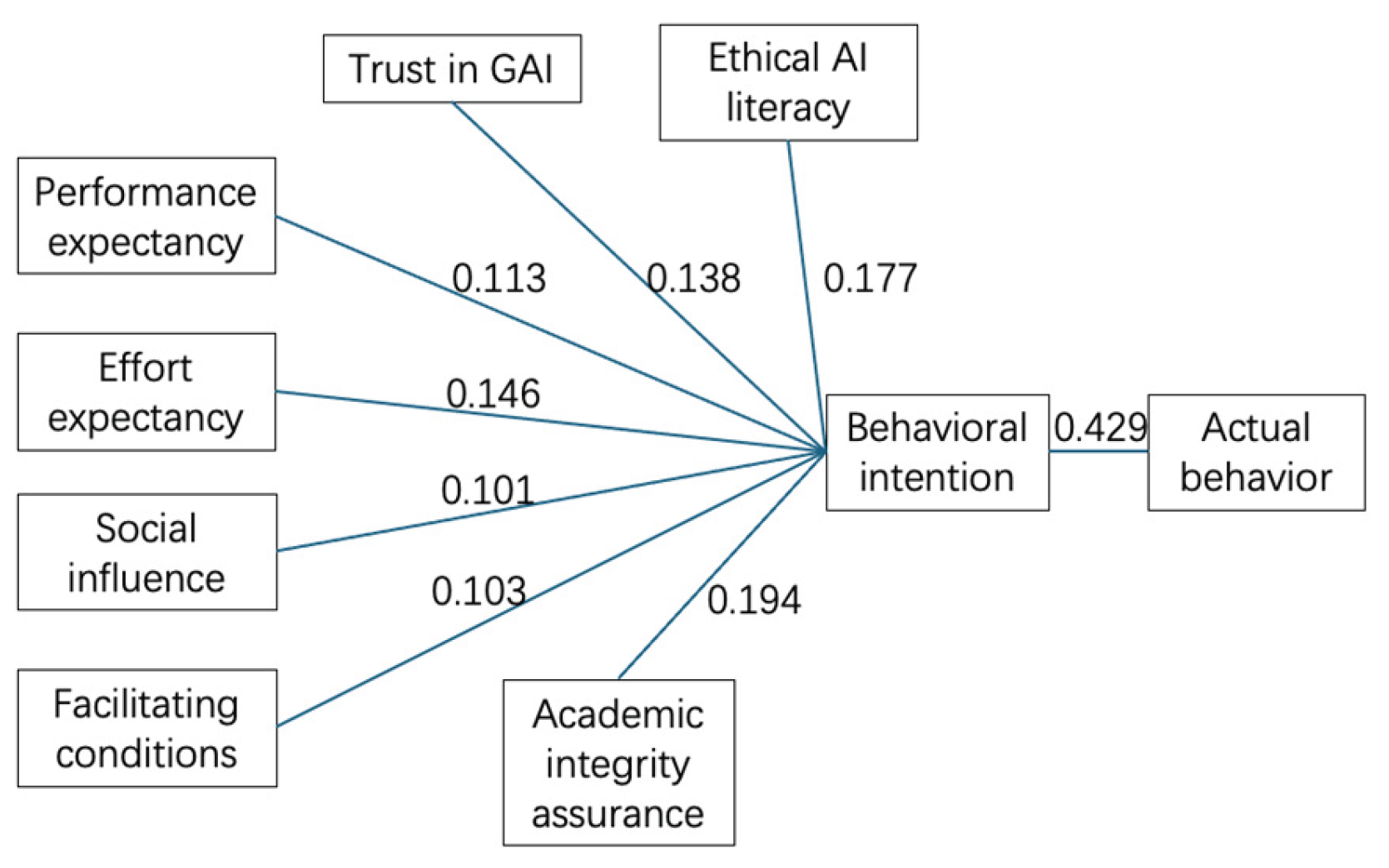

Table 5 below presents the results of hypothesis testing. The findings indicated that PE (β = 0.113, p < 0.001), EE (β = 0.146, p < 0.001), SI (β = 0.101, p < 0.001), FC (β = 0.103, p < 0.001), TGAI (β = 0.138, p < 0.001), EAIL (β = 0.177, p < 0.001), AIA (β = 0.194, p < 0.001) significantly influenced students intention to use GAI, and behavioral intention (β = 0.429, p < 0.001) significantly influenced students’ actual use of GAI. Hence, H1 through H8 were all supported.

The

Figure 2 below illustrates the standardized path coefficients and their significance levels for each hypothesized path.

4.2. Moderating Effects

To examine whether the effects of key predictors on students’ behavioral intention and actual use of GAI tools differed across demographic groups, this study tested the moderating roles of gender, grade level, and academic major using interaction-term regression analyses. The results indicated that none of the demographic variables significantly moderated any of the proposed relationships (all p > 0.05). The results of the moderation analysis are presented in

Table 6.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Findings

The structural model results reveal nuanced insights into what drives university students to use GAI in academic writing. All eight hypothesized paths in the extended UTAUT model were statistically supported. Among all predictors, the path from behavioral intention to actual use emerged strongest (β = 0.429), representing a medium-to-strong effect. This finding aligns with UTAUT theory, emphasizing intention as a pivotal gateway to behavior (Im et al., 2011; Schaper et al., 2007; Venkatesh et a., 2003).

Among antecedents to intention, AIA held the most weight among newly introduced constructs (β = 0.194), followed closely by EAIL (β = 0.177). While both fall within the “small-to-medium” effect range (β between .10 and .29) per Cohen’s conventions, they represent the strongest influences in the expanded model. This underscores how ethical sensitivity and evaluative awareness about AI shape student willingness to adopt GAI tools. These effects resonate with studies highlighting ethical awareness as a central component of AI usage (e.g., Usher & Barak, 2024; Wang et a., 2025). Closely following were EE (β = 0.146) and TGAI (β = 0.138), both also within the small-to-medium range. These findings support the idea that students’ perception of ease of use and confidence in their writing abilities play significant roles—consistent with prior research (e.g., Sha et al., 2025). In addition, the traditional UTAUT constructs—PE (β = 0.113), SI (β = 0.101), and FC (β = 0.103)—while possessing smaller effect sizes, remain statistically significant, as confirmed by previous research (e.g., Blut et al., 2022; Marchewka & Kostiwa, 2007). These results suggest that while traditional constructs in the UTAUT model remain relevant predictors of students’ intention to use GAI, while enhancing AI literacy education may have substantial impact in strengthening that intention.

Interestingly, the moderating analysis revealed that gender, grade, and major did not significantly moderate any of the hypothesized paths. This finding suggests that students’ acceptance and use of GAI tools are largely consistent across demographic groups, possibly reflecting the growing ubiquity and normalization of such tools in higher education. This result is partially inconsistent with previous findings (e.g., Lin & Jiang, 2025; Xu et al., 2025). For example, Xu et al. (2025) reported that gender moderated the effects of novelty value and social influence on behavioral intention, and grade moderated the effect of facilitating conditions. The discrepancy may be attributed to contextual factors such as cultural and institutional environments, the nature of the AI tools involved, or students’ growing familiarity with GAI regardless of demographic background. Additionally, it may reflect a shift toward more equitable access to digital resources and a convergence in students’ attitudes toward emerging technologies across different academic fields.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the factors influencing university students’ use of GAI tools in academic writing by extending the UTAUT framework to include trust in GAI, ethical AI literacy, and academic integrity assurance. The results demonstrated that all eight hypothesized relationships were statistically supported, highlighting the relevance of both technological and psychological variables in shaping students’ behavioral intentions and actual usage. Moreover, the lack of significant moderating effects from gender, grade level, and academic major suggests a relatively consistent pattern of GAI adoption across different student groups. These findings not only enrich the theoretical understanding of GAI use in higher education but also offer practical guidance for promoting ethical and effective integration of AI tools into writing instruction.

5.1. Limitations

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the data were collected through self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to common method bias and social desirability effects, potentially inflating the observed relationships. Second, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between the constructs. Longitudinal or experimental studies are needed to examine how students’ intentions and behaviors regarding GAI use evolve over time. Third, the sample was drawn from three universities in Beijing, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to students in other regions or educational contexts. Future research should consider more diverse samples, including students from different cultural, institutional, and linguistic backgrounds. Finally, while the study introduced three new constructs into the UTAUT framework, other potentially influential factors—such as digital literacy, prior AI usage experience, and teacher attitudes—were not examined and could be incorporated in future models to provide a more comprehensive understanding of GAI adoption in academic writing.

5.2. Implications

The results of this study shed light on several actionable insights for higher education stakeholders. The strong predictive power of the extended UTAUT model suggests that effective integration of GAI tools into academic writing should involve more than just providing access to technology. Educators are encouraged to design instructional approaches that foster students’ confidence in their own writing abilities and cultivate their critical awareness of AI-generated content. These psychological and cognitive supports can help students use GAI tools more thoughtfully and appropriately. In addition, the significant influence of academic integrity assurance points to the necessity of reinforcing ethical considerations in AI-assisted writing. Embedding clear guidance on authorship, originality, and responsible tool use within writing curricula can mitigate potential misuse. Notably, the absence of moderating effects across demographic groups implies that students are responding to GAI use in relatively uniform ways, regardless of their gender, year of study, or academic major. This suggests that broad-based interventions—such as institutional policies and general training programs—may be effective across diverse student populations. Universities may also benefit from establishing transparent usage policies and offering hands-on workshops to ensure students can engage with GAI tools productively and ethically.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, Haiying Liang. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board (protocol code IRB00001052-25022)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all the students who participated in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GAI |

Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| UTAUT |

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| PE |

Performance Expectancy |

| EE |

Effort Expectancy |

| SI |

Social Influence |

| FC |

Facilitating Conditions |

| TGAI |

Trust in GAI |

| EAIL |

Ethical AI Literacy |

| AIA |

Academic Integrity Assurance |

| BI |

Behavioral Intention |

| UB |

Usage Behavior |

| EFL |

English as a Foreign Language |

| CFA |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CR |

Composite Reliability |

| AVE |

Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT |

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio |

| KMO |

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| SRMR |

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| RMSEA |

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| CFI |

Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI |

Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SEM |

Structural Equation Modeling |

| EFA |

Exploratory Factor Analysis |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire constructs and items to analyze intentions to use and actual use of GAI in academic writing.

Table A1.

Questionnaire constructs and items to analyze intentions to use and actual use of GAI in academic writing.

| Items |

Constructs and Contents |

Reference |

| |

Performance Expectancy (PE) |

(Venkatesh et al., 2003) |

| PE1 |

Using GAI tools helps me improve the quality of my academic writing. |

| PE2 |

GAI tools enhance my efficiency in completing academic writing tasks. |

| PE3 |

GAI tools contribute to better organization and clarity in my writing. |

| |

Effort Expectancy (EE) |

| EE1 |

Learning to use GAI tools for academic writing is easy for me. |

| EE2 |

I find it straightforward to interact with GAI tools when writing. |

| EE3 |

It requires little effort for me to use GAI tools in writing assignments. |

| |

Social Influence (SI) |

| SI1 |

People important to me think I should use GAI tools for academic writing. |

| SI2 |

My peers use GAI tools for their academic writing. |

| SI3 |

Teachers or supervisors encourage the use of GAI tools in writing. |

| |

Facilitating Conditions (FC) |

| FC1 |

I have access to necessary resources to use GAI tools effectively. |

| FC2 |

I receive sufficient support when I encounter difficulties with GAI tools. |

| |

Trust in GAI (TGAI) |

Nazaretsky et al., 2025 |

| TGAI1 |

I trust GAI tools to generate accurate and reliable content for academic writing. |

| TGAI2 |

I believe GAI outputs are fair and unbiased. |

| TGAI3 |

I feel confident that I understand how GAI arrives at its suggestions. |

| |

Ethical AI literacy (EAIL) |

|

| EAIL1 |

I understand the appropriate ways to cite or reference content generated by GAI. |

Long & Magerko, 2020 |

| EAIL2 |

I can evaluate whether GAI output is sufficiently accurate and unbiased for academic purposes. |

| EAIL3 |

I know when it is appropriate to rely on GAI assistance and when human judgment is required. |

| |

Academic integrity assurance (AIA) |

|

| AIA1 |

I believe using GAI tools in academic writing, when properly cited, is compatible with my university’s academic integrity policy. |

Lubis et al., 2024 |

| AIA2 |

I feel assured that using GAI for drafting or idea generation can align with academic honesty standards. |

| AIA3 |

I feel confident that I can use GAI tools responsibly without violating plagiarism rules. |

| |

Behavioral Intention (BI) |

Venkatesh et al., 2003 |

| BI1 |

I intend to continue using GAI tools for academic writing. |

| BI2 |

I plan to explore more ways to integrate GAI into my writing process. |

| BI3 |

I would recommend the use of GAI tools for academic writing to others. |

| |

Usage Behavior (UB) |

| UB1 |

I regularly use GAI tools to assist my academic writing. |

| UB2 |

I use GAI tools in different stages of writing (e.g., idea generation, proofreading). |

| UB3 |

I actively integrate GAI suggestions into my written work. |

References

- Abbad, M. M. Using the UTAUT model to understand students’ usage of e-learning systems in developing countries. Education and Information Technologies 2021, 26(6), 7205–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, A.; Din, R. Acceptance and use of massive open online courses: extending UTAUT2 with personal innovativeness. Journal of Personalized Learning 2021, 4(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, S.; Abbas, M. Personality correlates of academic use of generative artificial intelligence and its outcomes: does fairness matter? Education and Information Technologies 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Mesquita, A.; Carnaz, G. Generative AI and higher education: Trends, challenges, and future directions from a systematic literature review. Information 2024, 15(11), 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Chong, A. Y. L.; Tsiga, Z.; Venkatesh, V. Meta-analysis of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): challenging its validity and charting a research agenda in the red ocean. In Association for Information Systems; January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M.; Khosravi, H.; De Laat, M.; Bergdahl, N.; Negrea, V.; Oxley, E.; Siemens, G. A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanpradit, T. Generative artificial intelligence in academic writing in higher education: A systematic review. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 2025, 9(4), 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C. M. Factors determining the behavioral intention to use mobile learning: An application and extension of the UTAUT model. Frontiers in Psychology 10 2019, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Vidaurre, S. M.; Velásquez Rodríguez, N. C.; Gambetta Quelopana, R. L.; Martinez Valdivia, A. N.; Leo Rossi, E. A.; Nolasco-Mamani, M. A. Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence and Its Impact on Academic Integrity Among University Students in Peru and Chile: An Approach to Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2024, 16(20). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getenet, S.; Cantle, R.; Redmond, P.; Albion, P. Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Mizumoto, A. Examining the effect of generative AI on students’ motivation and writing self-efficacy. Digital Applied Linguistics 1 2024, 102324–102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, I.; Hong, S.; Kang, M. S. An international comparison of technology adoption: Testing the UTAUT model. Information & Management 2011, 48(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Almusharraf, N. Analyzing the role of ChatGPT as a writing assistant at higher education level: A systematic review of the literature. Contemporary Educational Technology 2023, 15(4), ep464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intelligent.com. (2023, January 18–19). Nearly a third of college students have used ChatGPT on written assignments. Intelligent.

- Jacob, S. R.; Tate, T.; Warschauer, M. Emergent AI-assisted discourse: a case study of a second language writer authoring with ChatGPT. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning 2025, 5(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H.; Wells, R. F.; Shanks, E. M.; Boey, T.; Parsons, B. N. Student perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence technologies in higher education. International Journal for Educational Integrity 2024, 20(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Albadawy, M. Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update 2024, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampusaen, D. The impact of ChatGPT on academic writing skills and knowledge: An investigation of its use in argumentative essays. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network 2025, 18(1), 963–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovari, A.

Ethical use of ChatGPT in education—Best practices to combat AI-induced plagiarism

. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA, 2025; Vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Z. C. C. The Impact of AI-Assisted Blended Learning on Writing Efficacy and Resilience. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT) 2025, 15(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, W.; Whipple, P. B. Evaluating the role of ChatGPT in enhancing EFL writing assessments in classroom settings: A preliminary investigation. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, Article 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Jiang, P. Factors Influencing College Students’ Generative Artificial Intelligence Usage Behavior in Mathematics Learning: A Case from China. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15(3), 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Magerko, B. What is AI Literacy? Competencies and Design Considerations. In In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Article 3376727); Association for Computing Machinery, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, D. A. Y.; Aryanty, N.; Raudhoh, S. Development and Content Validity of an Instrument for Assessing the Fundamental Aspects of Academic Integrity. Jambi Medical Journal: Jurnal Kedokteran dan Kesehatan 2024, 12(2), 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B. D.; Lee, T. H.; Mannuru, N. R.; Arutla, N. AI and academic integrity: Exploring student perceptions and implications for higher education. In Journal of Academic Ethics; Advance online publication, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S. Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students’ academic writing skills: A mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learning Environments 11 2024, Article 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. A.; Amjad, A. I.; Aslam, S.; Fakhrou, A. Global insights: ChatGPT’s influence on academic and research writing, creativity, and plagiarism policies. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 9 2024, 1486832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchewka, J. T.; Kostiwa, K. An application of the UTAUT model for understanding student perceptions using course management software. Communications of the IIMA 2007, 7(2), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A. W.; Craig, S. B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods 2012, 17(3), 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaretsky, T.; Mejia-Domenzain, P.; Swamy, V.; Frej, J.; Käser, T. The critical role of trust in adopting AI-powered educational technology for learning: An instrument for measuring student perceptions. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2025, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F. Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Reading &Writing Quarterly 2003, 19(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Schaper, L. K.; Pervan, G. P. ICT and OTs: A model of information and communication technology acceptance and utilisation by occupational therapists. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2007, 76, S212–S221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, T. Understanding college students’ acceptance of machine translation in foreign language learning: an integrated model of UTAUT and task-technology fit. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2025, 12(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Lerigo-Sampson, M.; Barker, J. Recontextualising the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Framework to higher education online marking. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 2025, 21(8), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sok, S.; Heng, K. ChatGPT for education and research: A review of benefits and risks. Cambodian Journal of Educational Research 2023, 3(1), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A.; El-Arabawy, S. Investigation of the moderation effect of gender and study level on the acceptance and use of generative AI by higher education students: Comparative evidence from Poland and Egypt. British Journal of Educational Technology 2024, 55(3), 1209–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya Bahadur, G. C.; Bhandari, P.; Gurung, S.; Srivastava, E. Examining the role of social influence, learning value and habit on students’ intention to use ChatGPT: Moderating effect of information accuracy in UTAUT2. Cogent Education 2024, 11, Article 2403287. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, M. F.; Wang, C. Assessing academic writing self-efficacy belief and writing performance in a foreign language context. Foreign Language Annals 2023, 56(1), 144–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, M.; Barak, M. Unpacking the role of AI ethics online education for science and engineering students. International Journal of STEM Education 2024, 11(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M. G.; Davis, G. B.; Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly 2003, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chai, C. S.; Li, J.; Lee, V. W. Y. Assessment of AI ethical reflection: the development and validation of the AI ethical reflection scale (AIERS) for university students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2025, 22(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Shadiev, R.; Li, C. College students’ use behavior of generative AI and its influencing factors under the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Education and Information Technologies 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Rashid, A. M.; Ouyang, S. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in higher education: a systematic review. Sage Open 2024, 14(1), 21582440241229570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Schiebinger, L. AI can be sexist and racist—it’s time to make it fair. Nature 2018, 559(7714), 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).