1. Introduction

One of the most important global challenges of the modern world is food security, and the greatest threat to it is the observed increase in air temperature on the Earth surface and its consequences in the form of climate change [

1,

2]. According to long-term forecasts, by the end of the 21st century, the average air temperature will increase by about 3°C [

3]. One of the sectors of the economy that is particularly sensitive to climate change is agriculture [

4]. Extreme weather events, including increasingly frequent droughts and heavy rainfall, have a significant impact on crop yields and food production stability [

5,

6]. Agricultural productivity is also affected by changing soil conditions, disease and pest pressure, and changing crop and land management practices [

7,

8,

9]. These changes pose a serious threat to food security and require adaptation measures and the search for new solutions, such as the selection of resistant species and cultivars, the use of water-saving technologies and the introduction of regenerative agriculture practices [

10,

11]. An example of water-saving solutions is the use of soil additives that retain water, known as hydrogels or superabsorbents (SAP). Superabsorbents are synthetic or bio-derived polymers capable of storing large amounts of water in relation to their own weight. When applied to the soil, these polymers swell, increasing their volume, thereby improving soil structure, increasing its porosity and aggregation, reducing losses caused by water seepage, and thus increasing water capacity [

12,

13]. As a result, they help to mitigate the effects of water scarcity on plants. Thanks to the application of SAP, the root system is better developed and allows for the uptake of water and nutrients from deeper soil layers. In addition, water retention within the root ball allows plants to draw on water reserves during dry periods, which reduces stress, and proper soil moisture translates into better turgor and photosynthetic efficiency of plants, which in turn increases crop yields [

14,

15,

16].

In an era of climate change and global population growth, ensuring sufficient food supplies while caring for natural resources is becoming an important element of the global economy. Legumes play a key role in ensuring food security, as they are a source of feed protein and also support a balanced human diet. In addition, these plants are an important source of fibre, vitamins and minerals [

17]. Legumes are very important for sustainable agriculture due to their ability to biological nitrogen fixation and improve soil structure, thereby increasing soil fertility and improving water and air conditions [

18].

However, the water requirements of legumes are high and varied. This group is very sensitive to uneven rainfall distribution and water shortages during critical periods, which occur during the germination, flowering, pod formation and seed filling. Drought during these periods can significantly reduce seed yield [

19].

Water stress leads to disturbances in the structure and functioning of plant cells through numerous biochemical and physiological changes in plants [

20,

21]. The main factors determining the impact of soil water deficiency on plant physiology are the duration, frequency and intensity of drought. Moderate stress causes changes at the stomatal level, while prolonged and severe water shortages contribute to metabolic and structural changes [

22,

23]. In legumes, stress associated with soil water deficiency limits basic life processes (photosynthesis and transpiration), which adversely affects growth and development and, as a consequence, reduces seed yield and quality, often through changes in protein content and anti-nutritional substances [

19,

24]. The impact of drought stress on the photosynthetic apparatus of plants is well known [

19,

24,

25]. Photosystem II (PSII) is more sensitive to water deficiency than photosystem I (PSI), and severe stress caused by limited soil water availability can contribute to its damage [

23,

27]. One method of studying the effect of stress factors on the functioning of the photosynthetic apparatus is to measure chlorophyll fluorescence. Analysis of individual parameters provides a wealth of information about the functioning of PSII in plants exposed to biotic and abiotic stress factors [

23,

28,

29]. Chlorophyll pigments are an indicator of plant vitality and resistance to environmental stresses [

30]. Their content in leaves depends on habitat and weather conditions, but above all it is a genetic trait [

31]. Under conditions of water deficit, cells in the leaves shrink and become denser, which leads to an increase in the concentration of small and large molecules in the cell, including chlorophyll [

32]. However, other authors report a decrease in chlorophyll content under water shortage conditions, which may be caused by excessive production of reactive oxygen species that damage chloroplasts and accelerate chlorophyll breakdown under water deficit [

19,

20].

The aim of the study was to assess the effect of superabsorbent on the condition of selected legume species grown with different watering frequencies.

2. Materials and Methods

Three, two-factor pot experiments were conducted in MICRO-CLIMA phytotrons from SNIJDERS LABS. The objects of the study were three legume species: faba bean (

Vicia faba L.), pea (

Pisum sativum L.) and soybean (

Glycine max (L.) Merrill). The first factor was the superabsorbent (SAP) rate - 0, 2, 4, 6 g·kg

-1 of substrate (SAP0, SAP2, SAP4, SAP6), while the second factor was the watering frequency - the subjects were watered every 1, 3, 6, 9 days (W1, W3, W6, W9). The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design, with 4 replicates. The substrate, dried for 72 hours at 50ºC, was a mixture of horticultural soil for vegetables and sand in a ratio of 5:2. Pots with a capacity of 0.5 l were filled with substrate (300 g) mixed with an appropriate rate of granulated hydrogel (Aqua Terra Hydrogel). The seeds of faba bean (Granit cultivar), pea (Hubal cultivar) and soybean (Aldana cultivar) were treated with an antifungal dressing (Funaben) before sowing and then sown in moist substrate (3 seeds per pot). The faba bean were sown at a depth of 4-5 cm, the pea at 3-4 cm and the soybean at 1.5 cm. The pots were placed in a phytotron chamber. The conditions in the phytotron are presented in

Table 1.

For each hydrogel rate, the maximum water capacity of the soil was determined using Vanschafi cylinders. In the 3-leaf stage of pea (BBCH 13) and faba bean (BBCH 13) and the 3-leaf stage of soybean (BBCH 13), different watering frequencies were introduced (every 1, 3, 6 and 9 days). All pots were weighed and watered to optimal conditions (60% of field water capacity).

2.1. Measurement Methods and Laboratory Analyses

During the experiments, measurements of chlorophyll fluorescence and the leaf greenness index (SPAD) were performed. Direct chlorophyll a fluorescence measurements were performed using a non-invasive (in vivo) method with a PocketPEA fluorometer (Hansatech Instruments – WB). Two indices were assessed: Fv/Fm, determining the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII), and PI, the PSII performance index. Chlorophyll fluorescence indices were used to determine the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus and to assess the physiological condition of the plants. SPAD measurements were performed using a SPAD – HYDRO N-TesterTM chlorophyll meter. The device measures the differences between light absorption by the leaf at two wavelengths (650 and 950 nm), and the quotient of these differences is the leaf greenness index, or relative chlorophyll content. Measurements were taken for each treatment one day before the planned watering date. Four measurements were taken for treatments watered every 1, 3 and 6 days, and three measurements for treatments watered every 9 days. The results presented are the average of all measurements for a given watering frequency. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements were performed in 9 replicates, and the SPAD index in 3 replicates (one replicate as the average of 30 measurements). In the BBCH 50 phase (first flower buds visible), the plants were cut and the following measurements were taken: height, number of nodes, dry weight of the aboveground part (shoot) and underground part (root).

The collected results were statistically analyzed for a completely randomized design using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the Statgraphic Centurion XVI programme. To compare the differences between the means for the main factors and interactions, a multiple confidence interval test (Tukey's test) was used at a significance level of p≤0.05.

4. Discussion

The climate changes observed in recent years and the associated irregular rainfall, prolonged droughts and sudden violent storms causing rapid runoff of rainwater from fields indicate the need for rational water management in agriculture. The use of artificial irrigation systems is often uneconomical and/or impossible for technical and environmental reasons. Areas with light, permeable soils with low water retention are most sensitive to lack of rainfall. Legumes are among the species most sensitive to water stress, but the requirements of individual species vary. This group is particularly sensitive to uneven rainfall distribution and water shortages during critical periods, which occur during germination, flowering, pod formation, and seed development. Drought during these periods affects morphological traits and physiological processes and can significantly reduce yields [

19,

33,

34]. The use of a soil additive in the form of a superabsorbent can be an effective way to retain water in the soil. However, for the hydrogel to work effectively, regular rainfall is required to allow water to be absorbed and then made available to plants.

The growth of cells and organs in plants requires large amounts of energy and water availability. In order for cells to increase in size, water from the intercellular space must enter them. During water shortage, the plant limits its growth by inhibiting cell division and cell growth [

35]. Restricting the growth of the aboveground part of the plant is one of the defense mechanisms against water stress. The results of our research showed a significant impact of the superabsorbent on the biometric parameters of legumes. Faba bean and pea plants were significantly taller after the application of hydrogel. In addition, the application of SAP at a rate of 6 g·kg

-1 increased the dry weight of the underground parts of faba beans and peas (by 56.8% and 85.9%, respectively) compared to the control. Regular water supply caused the superabsorbent to retain water in the soil and make it available to plants as needed, so that the plants did not experience drought stress. This enabled the proper development of aboveground and underground biomass. In addition, the superabsorbent improved soil structure and enabled better root system development. Ryan et al. [

36] demonstrated a significant effect of hydrogel on soybean biometric parameters under field conditions. According to the authors, the most effective was the application of SAP at a rate of 7.5 kg·ha

-1, which contributed to an increase in plant height by 35.6%, leaf area by 93.4%, number of pods per plant by 99.3% and dry plant mass by 39.8% compared to the control treatment. In field studies conducted by Shankarappa et al. [

37], the use of superabsorbent in the cultivation of lentils at a rate of 5 kg·ha

-1 resulted in a 22.0% increase in the number of pods per plant, and the plants were 16.6% taller compared to the control. Youssef et al. [

38], based on studies conducted in Egypt, showed that the application of superabsorbent at a rate of 0.7% of soil weight significantly increased the parameters of vegetative growth of peas, i.e. plant height, number of leaves per plant, dry weight of above-ground and underground parts, and root length compared to the control where SAP was not applied. Norodinvand et al. [

39] demonstrated a significant effect of hydrogel on dry matter accumulation in common peas. The application of SAP at a rate of 0.5 and 1.0% of soil mass significantly increased the dry matter of plants. In contrast, Akhter et al. [

40] obtained different results, showing no effect of hydrogel at rates of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3% of soil weight on the length, fresh weight and dry weight of chickpea shoots.

Our experiment demonstrated the effect of watering frequency on the biometric characteristics of legumes. Plants watered daily were significantly taller and developed a greater number of nodes compared to plants watered every 3, 6 and 9 days. They also had significantly higher dry weight of the above-ground and below-ground parts. Only in soybeans was the dry weight of the underground parts significantly higher in the treatment watered least frequently (every 9 days) compared to treatments watered more frequently. Differences in response to stress result from species differences and strategies for adapting to water deficit. Field beans and peas are among the species that are more sensitive to periodic water shortages. Under optimal conditions, they are characterized by rapid shoot and root growth, but under conditions of water shortage, they limit biomass development. Soybeans, on the other hand, originate from a warmer climate and have developed certain adaptations to dry conditions. Under conditions of soil water shortage, this species limits the development of its above-ground parts and at the same time intensively develops its root system in order to reach deeper for water [

41]. This is confirmed by the research of Desclaux et al. [

42], who showed that soybean plants subjected to water shortages were shorter because they developed fewer nodes per plant and shorter internodes. Sadeghipour and Abbasi [

43] showed that water deficit in soybean cultivation stimulated defense mechanisms and caused flower and pod shedding, which reduced the number of pods per plant, the number of seeds per pod and seed weight. In turn, in the study by Ohashi et al. [

44], drought stress limited the growth and development of pods and reduced the dry weight of the vegetative part of soybeans. Reductions in growth parameters in peas under water deficit conditions were also demonstrated by Bodah et al. [

45] and Osman [

46].

One way to determine the efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus is to measure the chlorophyll fluorescence emitted from chloroplasts. This is a quick, non-invasive method of assessing the physiological condition of plants growing in different environmental conditions. Chlorophyll fluorescence indices are used as one of the most effective parameters for estimating photosynthetic activity [

47]. A decrease in photosynthetic activity under water deficit conditions limits the growth and productivity of crops [

48]. The Fv/Fm index determines the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II and can be used to determine the condition of plants under stress conditions [

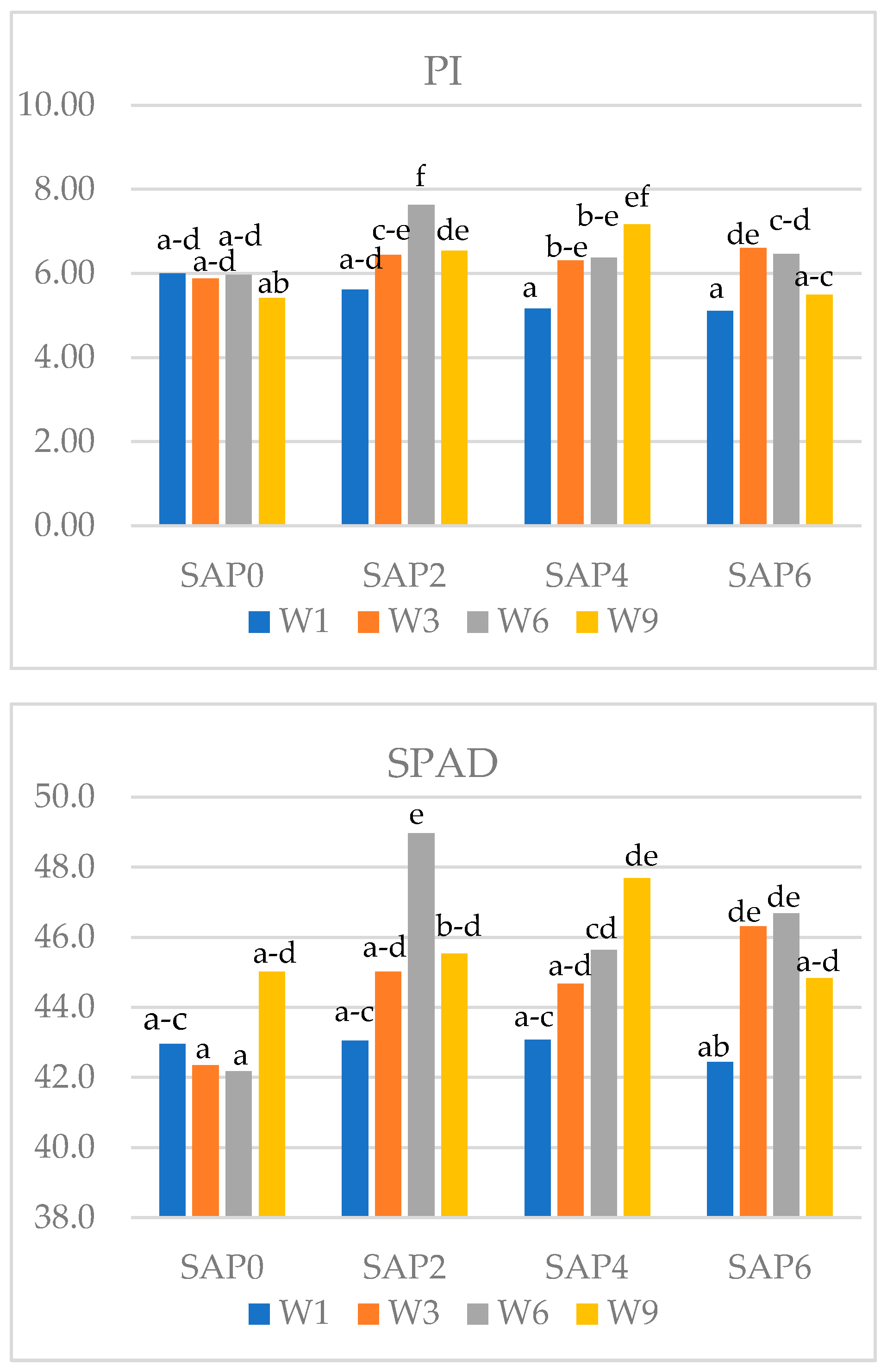

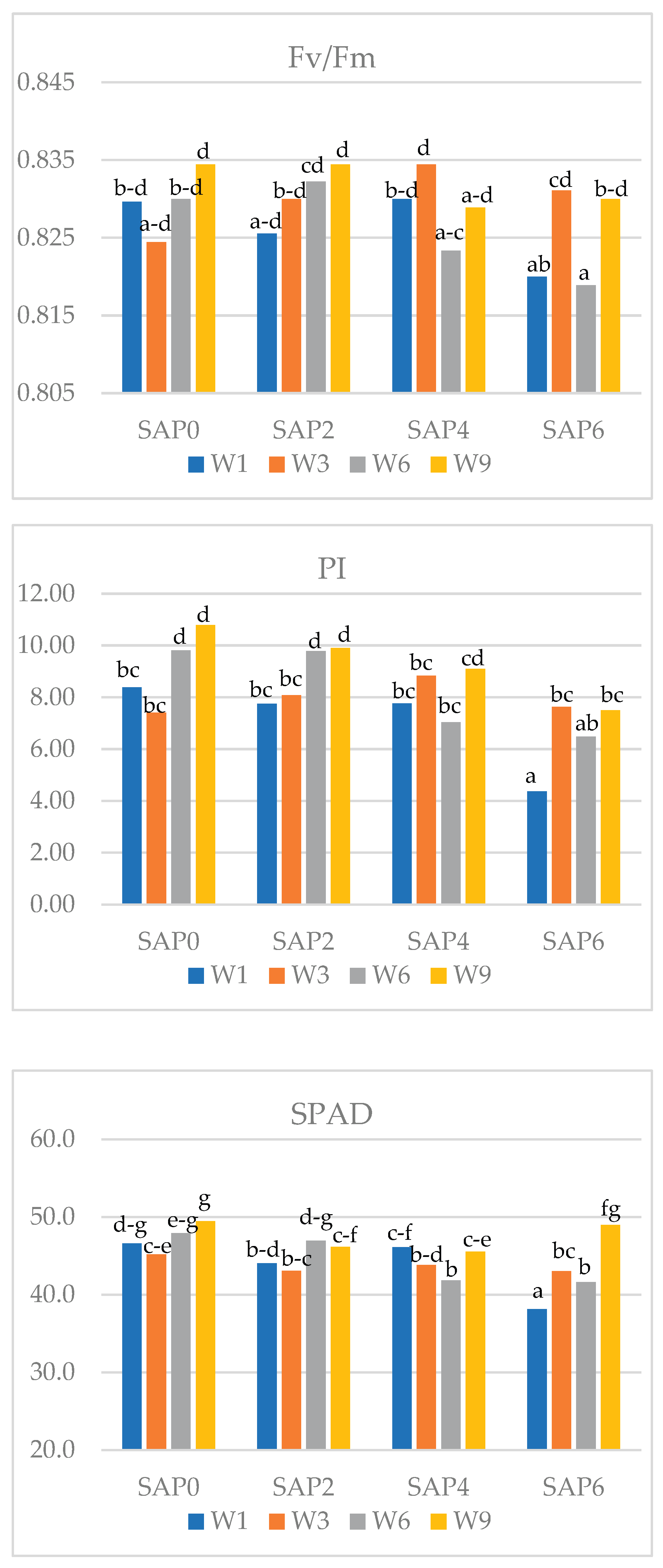

49]. The results of our research did not show a significant effect of superabsorbent on the Fv/Fm index in faba beans and peas. In soybeans, the application of the highest rate of superabsorbent significantly reduced the Fv/Fm index value compared to the other treatments. This could have been caused by an excessive rate of SAP, which led to poorer soil aeration and root hypoxia, which in turn limited nutrient uptake and PSII efficiency.

The effect of watering frequency on the chlorophyll fluorescence index was demonstrated. In faba beans and peas, the highest values of this index were recorded with daily watering compared to treatments watered less frequently. In contrast, the response was reversed in soybeans, with plants watered every 9 days showing higher PSII efficiency compared to those watered more frequently. The different response of soybeans to moisture conditions can be explained by the genetic adaptation of this species to periodic water shortages and high temperatures. In studies conducted by Abid et al. [

48], drought stress did not significantly affect the Fv/Fm index in tolerant cultivars of faba beans, while in a cultivar sensitive to water shortage, a significant decrease in Fv/Fm was observed at 30% relative humidity, which may suggest disturbances in PSII functioning. In turn, Allahmoradi et al. [

50] showed a decrease in the maximum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) in beans under water deficit conditions during the vegetative phase, compared to plants growing under optimal conditions. Ali et al. [

51] demonstrated an 85.7% reduction in the Fv/Fm index under water deficit conditions in two soybean cultivars compared to optimal conditions in a greenhouse experiment.

Another important chlorophyll fluorescence index that describes the amount of effective energy converted by photosystem II is the PSII vitality index (PI). This index expresses the plant's ability to defend itself against stress [

23]. The results of our research showed that the use of hydrogel at the highest rate of 6 g ka

-1 of substrate significantly reduced the PI index compared to other rates and the control treatment in soybeans and the SAP rate of 4 g·kg

-1 of substrate in field beans. In peas, however, the addition of hydrogel increased the PI index compared to the control. Furthermore, the highest values of the PSII functioning index in all legume species studied were observed in the treatments watered least frequently (every 9 days), and the PI value decreased with increasing watering frequency. In studies conducted by Allahmoradi et al. [

50], drought stress during the vegetative growth phase reduced the PI index in mungbean (

Vigna radiata L.) by 76.4% compared to the control treatment and by 75.9% compared to the treatment on which stress was initiated during the generative growth phase.

Drought conditions alter the content of photosynthetic pigments. Damage to thylakoid membranes and inhibition of biosynthesis lead to chlorophyll degradation. This limits the plant's ability to absorb light, leading to reduced photosynthetic intensity [

52,

53]. Studies have shown a variation in the relative chlorophyll content in leaves depending on the rate of hydrogel applied. In peas, the lowest SPAD index value was recorded in the control treatment, where no hydrogel was used, while in soybeans, the use of the highest rate of SAP reduced the relative chlorophyll content in the leaves compared to the other treatments. The response of individual species differed due to species differences in water management strategies in peas and soybeans. In peas, higher SAP rates improved soil moisture conditions, which resulted in higher chlorophyll content in the leaves. In soybeans, on the other hand, the highest rate of SAP may have caused root hypoxia, which limited nutrient uptake and disrupted chlorophyll metabolism. Compared to field peas, soybeans require better aerated soil due to their taproot system. Ahmed et al. [

54] showed that the leaf greenness index in green beans increased after the application of superabsorbent (from 0.1 to 0.9% of soil mass) compared to the control field (without SAP). A significant increase in the SPAD index was also noted in peas after the application of superabsorbent at a dose of 0.7% of soil mass in the plots, compared to the treatment without SAP [

38].

The results of our research showed that in all plant species studied, the leaf greenness index was higher under conditions of maximum water shortage (watering every 9 days) compared to plants watered every 1, 3 and 6 days. Drought caused water loss and reduced cell turgor, resulting in thinner leaves and increased chlorophyll density per unit leaf area [

32]. In studies by Rahbarian et al. [

33], the total chlorophyll content in chickpea (

Cicer arietinum L.) leaves decreased under conditions of limited soil moisture (25% ppw) by 12.4% in the seedling stage and by 57.5% at the beginning of flowering, while the opposite relationship was observed in the pod formation stage. Higher chlorophyll content in leaves was observed under water deficit conditions compared to control conditions (by 27.2%). A decrease in the SPAD index under water deficit was also observed in peas [

38,

55].