Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

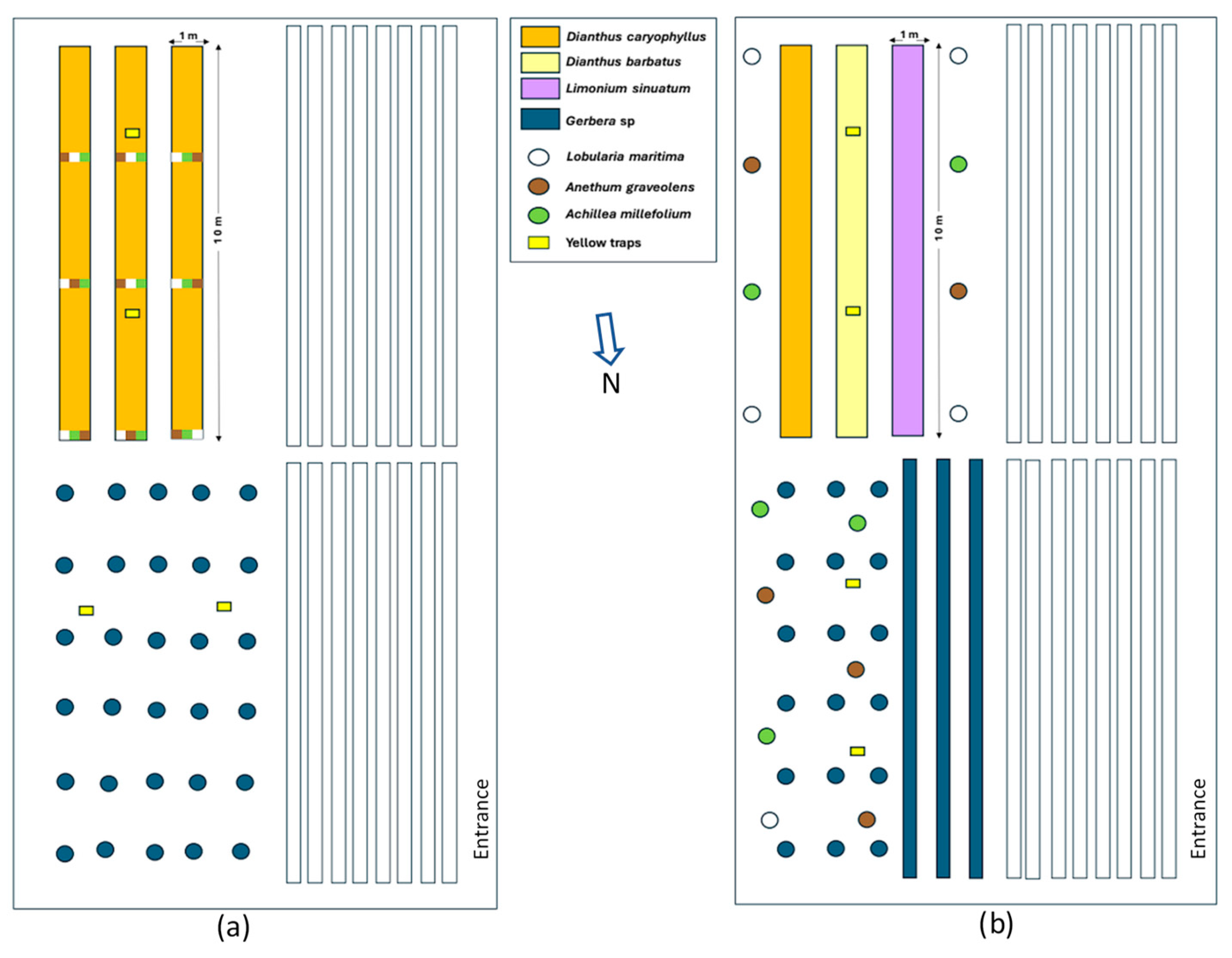

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling Procedure

2.4. Release of Orius laevigatus

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Alyssum | Yarrow | Dill | |

| 2021 | |||

| 18-Feb | Flowering | Vegetative | Vegetative - Initial flowering |

| 2-Mar | Flowering | Vegetative – First inflorescences stems | Flowering |

| 9-Mar | Flowering | Initial flowering | Flowering |

| 23-Mar | Flowering | Flowering | Flowering + Fructification |

| 13-Apr | Flowering | Flowering | Final flowering and fructification |

| 4-May | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering | Senescent |

| 11-May | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering | Senescent |

| 21-May | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering +Fructification | Senescent |

| 22-Jun | Flowering + Fructification | Few flowering + Fructification | Senescent |

| 2025 | |||

| 31-Jan | Flowering | Vegetative | Initial flowering |

| 13-Feb | Flowering | Vegetative | Flowering |

| 27-Feb | Flowering | Vegetative | Flowering |

| 13-Mar | Flowering | Vegetative | Flowering |

| 27-Mar | Flowering + Fructification | Vegetative – First inflorescences stems | Flowering |

| 9-Apr | Flowering + Fructification | Vegetative + Initial flowering | Flowering + Fructification |

| 24-Apr | Flowering + Fructification | Initial flowering | Flowering + Fructification |

| 6-May | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering | Few flowering + Fructification |

| 22-May | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering | Senescent |

| 6-Jun | Flowering + Fructification | Flowering | Senescent |

| 18-Jun | Few flowering + Fructification | Few flowering + Fructification | Senescent |

| 31/1/2025 | 13/2/2025 | 27/2/2025 | 13/3/2025 | 27/3/2025 | 9/4/2025 | 24/4/2025 | 6/5/2025 | 22/5/2025 | 6/6/2025 | 18/6/2025 | |

| Insectary plants1 | |||||||||||

| Alyssum | 7.7 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 9.7 |

| Yarrow | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| Dill | 13.0 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 2.7 | - | - | - |

| Ornamentals2 | |||||||||||

| Carnation | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 19 | 23 | 67 | 33 | 15 | - |

| Sweet William | 80 | 45 | 55 | 40 | 120 | 75 | 75 | 90 | 15 | 10 | - |

| Gerbera daisy | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 13 | 24 |

| Statice | 50 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 70 | 65 | 100 | 120 | 73 | 65 | 60 |

References

- van Lenteren, J.C. The state of commercial augmentative biological control: Plenty of natural enemies, but a frustrating lack of uptake. BioControl 2012, 57, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnakker, J.; Vangansbeke, D.; Duarte, M.; Moerkens, R.; Wäckers, F.L. Predators and Parasitoids-in-First: From Inundative Releases to Preventative Biological Control in Greenhouse Crops. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 595630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolin, P.; Bresch, C.; Desneux, N.; Brun, R.; Bout, A.; Boll, R.; Poncet, C. Secondary plants used in biological control: A review. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2012, 58, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, A.K.; Landis, D.A.; Wratten, S.D. Maximizing ecosystem services from conservation biological control: The role of habitat management. Biol. Control 2008, 45, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, D.K.; Armbrecht, I.; Rivera, B.S.; Lerma, J.M.; Carmona, E.J.; Daza, M.C.; Escobar, S.; Galindo, V.; Gutiérrez, C.; López, S.D.; et al. Does plant diversity benefit agroecosystems? A synthetic review. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, D.A.; Wratten, S.D.; Gurr, G.M. HABITAT MANAGEMENT TO CONSERVE NATURAL ENEMIES OF ARTHROPOD PESTS IN AGRICULTURE. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2000, 45, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, G.M.; Wratten, S.D.; Landis, D.A.; You, M. Habitat Management to Suppress Pest Populations: Progress and Prospects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoabeng, B.W.; Johnson, A.C.; Gurr, G.M. Natural enemy enhancement and botanical insecticide source: a review of dual use companion plants. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2019, 54, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, B.N.; Bugg, R.L.; Daane, K.M. Attractiveness of common insectary and harvestable floral resources to beneficial insects. Biol. Control 2011, 56, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, B.N.; Nelson, E.H.; Daane, K.M. A comparison of candidate banker plants for management of pests in lettuce. Environ. Entomol. 2023, 52, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Kiær, L.P.; Jensen, P.M.; Sigsgaard, L. The effect of floral resources on predator longevity and fecundity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Control 2021, 153, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá Herrera, R.; Ruano, F.; Gálvez Ramírez, C.; Frischie, S.; Campos, M.; Alcala Herrera, R.; Ruano, F.; Gálvez, C.; Frischie, S. Attraction of green lacewings ( Neuroptera : Chrysopidae ) to native plants used as ground cover in woody Mediterranean agroecosystems. Biol. Control 2019, 139, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá Herrera, R.; Castro-Rodríguez, J.; Fernández-Sierra, M.L.; Campos, M.; Alcala Herrera, R.; Castro-Rodríguez, J.; Fernández-Sierra, M.L.; Campos, M. Dittrichia viscosa (Asterales: Asteraceae) as an Arthropod Reservoir in Olive Groves. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Vila, E.; Janssen, D.; Bretones, G.; Salvador, E.; Lara, L.; Téllez, M. Selection of refuges for Nesidiocoris tenuis (Het.: Miridae) and Orius laevigatus (Het.: Anthocoridae): virus reservoir risk assessment. IOBC/OILB, wprs/srop Bull. 2009, 49, 281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Alomar, O.; Gabarra, R.; González, O.; Arnó, J. Selection of insectary plants for ecological infrastructure in Mediterranean vegetable crops; International Organization for Biological and Integrated Control of Noxious Animals and Plants (OIBC/OILB), West Palaearctic Regional Section (WPRS/SROP): Dijon, 2006; Vol. 29, pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin, P.; Bresch, C.; Poncet, C.; Desneux, N. Functional characteristics of secondary plants for increased pest management. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2012, 58, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Pérez, F.R. Trap Crops and Insectary Plants in the Order Brassicales. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2019, 112, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, M.R.; Luna, J.M. Relative Attractiveness of Potential Beneficial Insectary Plants to Aphidophagous Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Environ. Entomol 2000, 29, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennison, J.; Pope, T.; Maulden, K. The potential use of flowering alyssum as a “banker” plant to support the establishment of Orius laevigatus in everbearer strawberry for improved biological control of western flower thrips. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 2011, 68 PP-D, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pumariño, L.; Alomar, O. The role of omnivory in the conservation of predators: Orius majusculus (Heteroptera: Anthocoridae) on sweet alyssum. Biol. Control 2012, 62, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, L.A.; Wratten, S.D. Effects of alyssum flowers on the longevity, fecundity, and sex ratio of the leafroller parasitoid Dolichogenidea tasmanica. Biol. Control 2005, 32, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEGUM, M.; GURR, G.M.; WRATTEN, S.D.; HEDBERG, P.R.; NICOL, H.I. Using selective food plants to maximize biological control of vineyard pests. J. Appl. Ecol. 2006, 43, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, Y.; Riudavets, J.; Gabarra, R.; Agustí, N.; Rodríguez-Gasol, N.; Alins, G.; Blasco-Moreno, A.; Arnó, J. Can Insectary Plants Enhance the Presence of Natural Enemies of the Green Peach Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Mediterranean Peach Orchards? J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gasol, N.; Avilla, J.; Aparicio, Y.; Arnó, J.; Gabarra, R.; Riudavets, J.; Alegre, S.; Lordan, J.; Alins, G. The Contribution of Surrounding Margins in the Promotion of Natural Enemies in Mediterranean Apple Orchards. Insects 2019, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, J.; Wang, K.-H.; Hooks, C.R.R. An evaluation of insectary plants for management of insect pests in a hydroponic cropping system. Biol. Control 2015, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, A.L.S.; Souza, B.; Ferreira, R.B.; Aguiar-Menezes, E.L. Flowers of Apiaceous species as sources of pollen for adults of Chrysoperla externa (Hagen) (Neuroptera). Biol. Control 2017, 106, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, K.; Abbes, K.; Lassoued, M.; Jeddi, K.; Hessini, K.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Chermiti, B. Attractiveness of mediterranean native plants to arthropod natural enemies and herbivores. Arthropod. Plant. Interact. 2025, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, F.J. Evolución del control de plagas en la horticultura española: papel del control biológico aumentativo. Phytoma España 2019, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, E.; González, M.; Paredes, D.; Campos, M.; Benítez, E. Selecting native perennial plants for ecological intensification in Mediterranean greenhouse horticulture. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2018, 108, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Guo, J.-F.; Reitz, S.R.; Lei, Z.-R.; Wu, S.-Y. A global invasion by the thrip, Frankliniella occidentalis: Current virus vector status and its management. Insect Sci. 2020, 27, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Data sheets on Quarantine Pests: Frankliniella occidentalis; 1989.

- Calvo, F.J.; Knapp, M.; van Houten, Y.M.; Hoogerbrugge, H.; Belda, J.E. Amblyseius swirskii: What made this predatory mite such a successful biocontrol agent? Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2015, 65, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsgaard, H. Biological control of thrips on ornamental crops. In Biocontrol in Protected Culture; Heinz, K., Van Driesche, R., Parrella, M., Eds.; Ball Publishing: Batavia, IL, 2004; pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, J.; Alcázar, A.; Lacasa, A.; Llamas, A.; Bielza, P. Integrated pest management strategies in sweet pepper plastic houses in the southeast of Spain. IOBC/WPRS Bull 2000, 23, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, A.; Chau, A.; Heinz, K. Control of Frankliniella occidentalis on greenhouse roses with Amblyseius (Typhlodromips) swirskii and Orius insidiosus. IOBC/WPRS Bull 2008, 32, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, M.; Salvador, E.; Janssen, D.; Lara, L.; Tellez, M. Utilización de Mentha suaveolens Ehrh y Ocimum basilicum Linnaeus como plantas refugio para adelantar la instalación de Orius laevigatus Fieber ( Hemiptera : Anthocoridae ) en cultivo de pimiento. Bol. San. Veg. Plagas 2012, 38, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mound, L.A.; Morison, G.D.; Pitkin, B.R.; Palmer, J.M. Handbooks for the identification of British insects . In part 11. Thysanoptera; Royal Entomological Society of London.: London, 1976; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J.M.; Mound, L.A.; Heaume, G.J. CIE guides to insects of importance to man. 2. Thysanoptera.; CAB International: Wallingford, Oxon, 1989; ISBN 9780851986340. [Google Scholar]

- Curso práctico de entomología; Barrientos, A.J., Barrientos, J.A., Eds.; Manuals: Alicante, Bellaterra; 41; Asociación Española de Entomología; CIBIO; Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, 2004; ISSN ISBN 8449023831. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.L.; Gontijo, L.M. Alyssum flowers promote biological control of collard pests. BioControl 2017, 62, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Sharma, S.; Wratten, S.D. Flowering alyssum (Lobularia maritima) promote arthropod diversity and biological control of Myzus persicae. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2020, 23, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumariño, L.; Alomar, O. Assessing the use of Lobularia maritima as an insectary plant for the conservation of Orius majusculus and biological control of Frankliniella occidentalis. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 2014, 100, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Picó, F.X.; Retana, J. The flowering pattern of the perennial herb Lobularia maritima: an unusual case in the Mediterranean basin. Acta Oecologica 2001, 22, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahşi, Ş.Ü.; Tunç, İ. Development, survival and reproduction of Orius niger (Hemiptera:Anthocoridae) under different photoperiod and temperature regimes. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2008, 18, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Meiracker, R.A.F. Induction and termination of diapause in Orius predatory bugs. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1994, 73, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasini, M.G.; Van Lenteren, J.C. Occurrence of diapause in orius laevigatus. Bull. Insectology 2003, 56, 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Riudavets, J.; Castañé, C.; Gabarra, R. Native Predators of Western Flower Thrips in Horticultural Crops. In Thrips Biology and Management; Parker, B.L., Skinner, M., Lewis, T., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1995; pp. 255–258. ISBN 978-1-4899-1409-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarretta, A.; Travaglini, T.; Kfoury, L.; Ksentini, I.; Yousef-Yousef, M.; Sotiras, M.-I.; El Bitar, A.; Ksantini, M.; Quesada-Moraga, E.; Perdikis, D. Comparison of different trapping devices for the capture of Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) and other non-target insects in the Mediterranean basin. J. Entomol. Acarol. Res. 2024, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alcaide, F.; Quesada-Moraga, E.; Valverde-García, P.; Yousef-Yousef, M. Optimizing decision-making potential, cost, and environmental impact of traps for monitoring olive fruit fly Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araj, S.-E.; Shields, M.W.; Wratten, S.D. Weed floral resources and commonly used insectary plants to increase the efficacy of a whitefly parasitoid. BioControl 2019, 64, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araj, S.-E.; Wratten, S.D. Comparing existing weeds and commonly used insectary plants as floral resources for a parasitoid. Biol. Control 2015, 81, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnó, J.; Oveja, M.F.; Gabarra, R. Selection of flowering plants to enhance the biological control of Tuta absoluta using parasitoids. Biol. Control 2018, 122, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thysanoptera | Orius total | Orius adults | Orius nymphs | Aphididae | Formicidae | Hymenoptera parasitoids | Araneae | Acari | Collembola | TOTAL1 | |

| 2021 | |||||||||||

| Alyssum | 345 | 81 | 17 | 64 | 32 | 56 | 3 | 44 | 101 | 532 | 1226 |

| yarrow | 557 | 188 | 97 | 91 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 39 | 9 | 376 | 1199 |

| Dill | 170 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2660 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 24 | 2863 |

| Total | 1072 | 269 | 114 | 155 | 2702 | 66 | 8 | 89 | 110 | 932 | 5288 |

| 2025 | |||||||||||

| Alyssum | 163 | 88 | 44 | 44 | 0 | 43 | 4 | 23 | 9 | 242 | 649 |

| yarrow | 270 | 59 | 20 | 39 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 32 | 10 | 248 | 657 |

| Dill | 287 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 20 | 333 |

| Total | 720 | 148 | 65 | 83 | 3 | 54 | 14 | 64 | 20 | 510 | 1639 |

| TOTAL (two years) | 1792 | 417 | 179 | 238 | 2705 | 120 | 22 | 153 | 130 | 1442 | 6927 |

| Thysanoptera | Orius | Diptera | Aphididae | Aleyrodidae | Araneae | Coleoptera | Hymenoptera | TOTAL1 | |

| 2021 | 2591 | 12 | 837 | 4146 | 109 | 43 | 22 | 482 | 8371 |

| 2025 | 6607 | 7 | 5531 | 129 | 0 | 82 | 35 | 41 | 12500 |

| TOTAL | 9198 | 19 | 6368 | 4275 | 109 | 125 | 57 | 523 | 20871 |

| Plant species | Comparation of two plant species1 | Comparation of three plant species2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alyssum | Yarrow | Dill | Plant species | Date x Plant | Plant species | Date x Plant | ||||||||||||||

| Mean3 | s.e. | Mean3 | s.e. | Mean4 | s.e. | F5 | p | F6 | p | F7 | p | F6 | p | |||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||||||||||||||

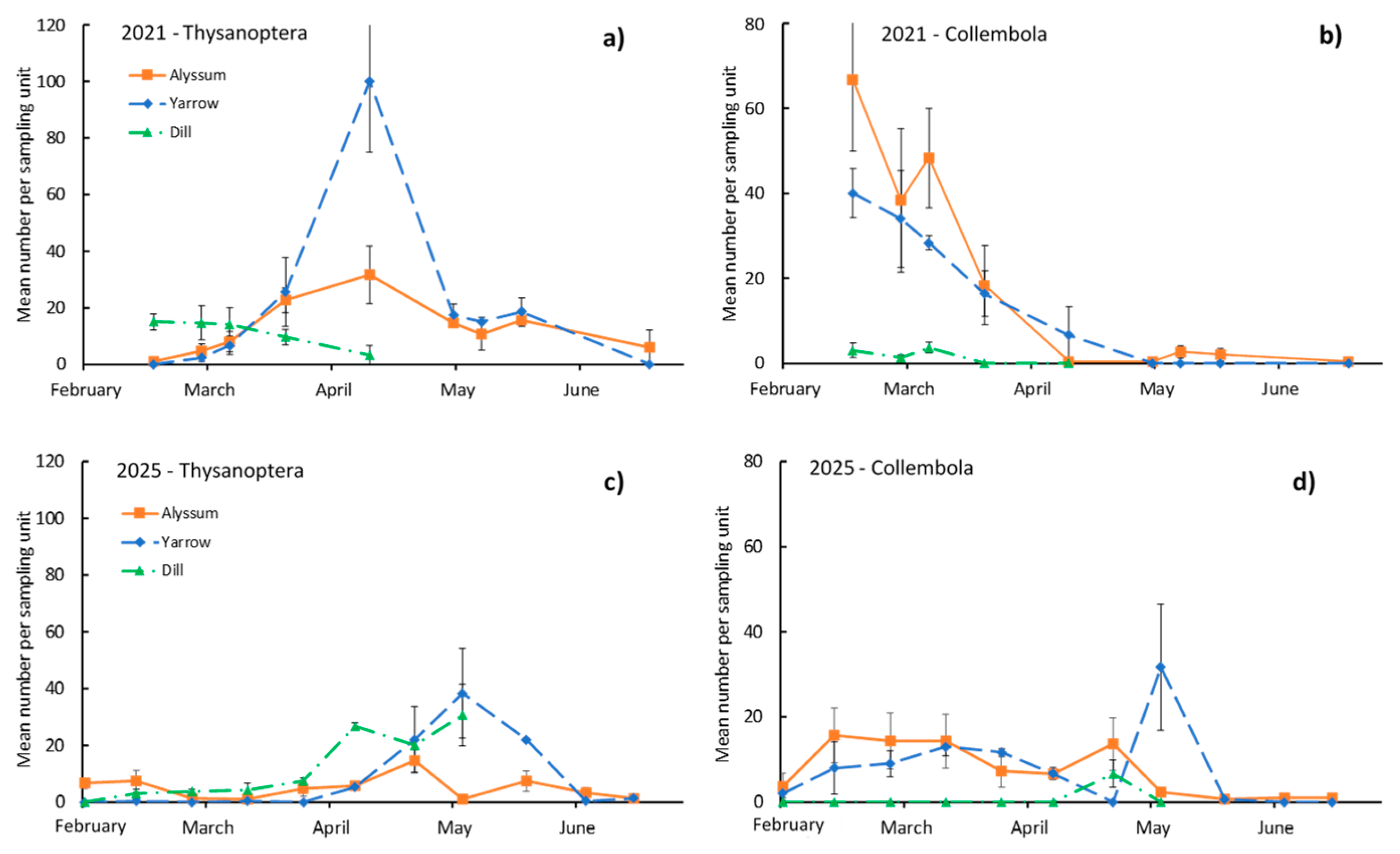

| Thysanoptera | 12.8 | 3.2 | 20.6 | 10.4 | 11.3 | 2.2 | 8.0 | 0.048 (*) | 8.0 | 0.066 | 5.1 | 0.052 | 8.4 | 0.006(*) | ||||||

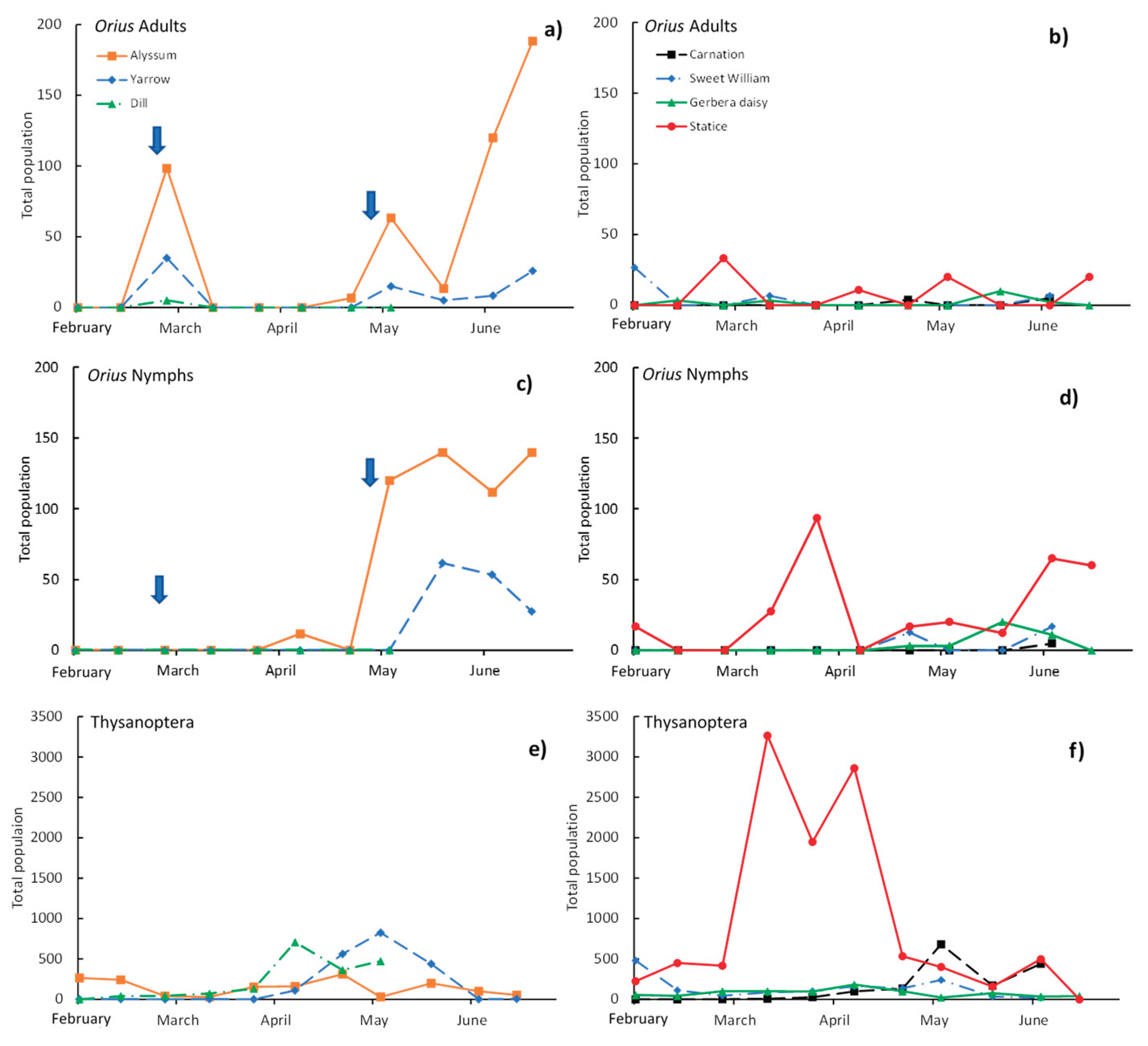

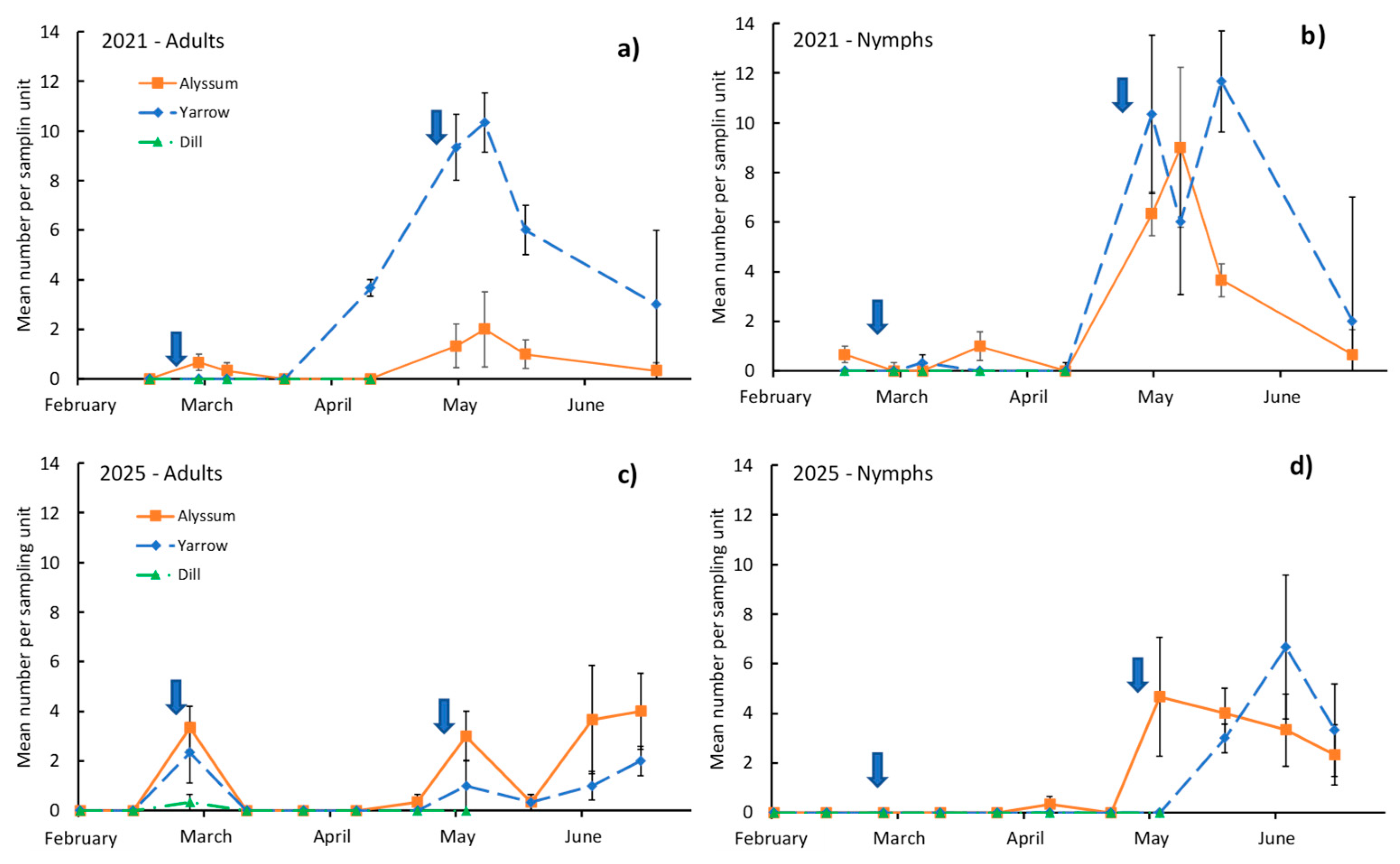

| Orius total | 3.0 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 44.7 | 0.003(*) | 4.0 | 0.056 | 11.2 | 0.009(*) | 19.4 | <0.001(*) | ||||||

| Orius adults | 0.6 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 200.0 | <0.001(*) | 6.0 | 0.027(*) | 97.0 | <0.001(*) | 38.1 | <0.001(*) | ||||||

| Orius nymphs | 2.4 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.112 | 4.6 | 0.028((*) | 2.6 | 0.152 | 2.9 | 0.087 | ||||||

| Aphididae | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 177.3 | 124.9 | 1.1 | 0.349 | 0.7 | 0.483 | 9.6 | 0.014(*) | 3.0 | 0.124 | ||||||

| Formicidae | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.114 | 0.8 | 0.470 | 2.4 | 0.170 | 0.7 | 0.540 | ||||||

| Hymenoptera | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.851 | 1.2 | 0.359 | 0.7 | 0.533 | 1.1 | 0.403 | ||||||

| Araneae | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.597 | 2.9 | 0.107 | 25.8 | 0.001(*) | 1.3 | 0.331 | ||||||

| Acari | 3.7 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 0.038(*) | 1.1 | 0.347 | 10.2 | 0.012(*) | 0.9 | 0.452 | ||||||

| Collembola | 19.7 | 8.4 | 13.9 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 0.115 | 0.9 | 0.423 | 31.3 | 0.001(*) | 2.1 | 0.174 | ||||||

| Total arthropods | 45.4 | 8.0 | 44.4 | 9.6 | 190.9 | 122.4 | 0.0 | 0.871 | 2.7 | 0.130 | 5.2 | 0.050 | 2.7 | 0.142 | ||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Thysanoptera | 4.9 | 1.2 | 8.2 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 4.2 | 6.7 | 0.060 | 3.8 | 0.106 | 7.6 | 0.02(*) | 2.9 | 0.114 | ||||||

| Orius total | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.182 | 1.5 | 0.273 | 14.1 | 0.005(*) | 7.6 | <0.001(*) | ||||||

| Orius adults | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.157 | 1.0 | 0.417 | 8.2 | 0.019(*) | 2.6 | 0.009(*) | ||||||

| Orius nymphs | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.782 | 1.8 | 0.217 | 3.6 | 0.095 | 3.7 | <0.001(*) | ||||||

| Aphididae | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| Formicidae | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 32.9 | 0.005(*) | 0.6 | 0.577 | 15.2 | 0.004(*) | 0.4 | 0.788 | ||||||

| Hymenoptera | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.145 | 0.9 | 0.412 | 2.4 | 0.174 | 1.3 | 0.335 | ||||||

| Araneae | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.295 | 1.4 | 0.299 | 0.9 | 0.465 | 1.0 | 0.466 | ||||||

| Acari | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.904 | 1.8 | 0.223 | 1.2 | 0.370 | 1.9 | 0.182 | ||||||

| Collembola | 7.3 | 1.8 | 7.5 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.910 | 2.6 | 0.123 | 17.8 | 0.003(*) | 2.5 | 0.011(*) | ||||||

| Total arthropods | 19.7 | 2.3 | 19.9 | 5.7 | 13.9 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 0.919 | 4.3 | 0.045(*) | 5.7 | 0.042(*) | 3.5 | 0.001(*) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).