Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area and citrus varieties

2.2. Above and belowground sampling of D. aberiae and natural enemies

2.3. D. aberiae population on fruits

2.4. Fruit Damage caused by D. aberie

2.5. Data analysis

3. Results

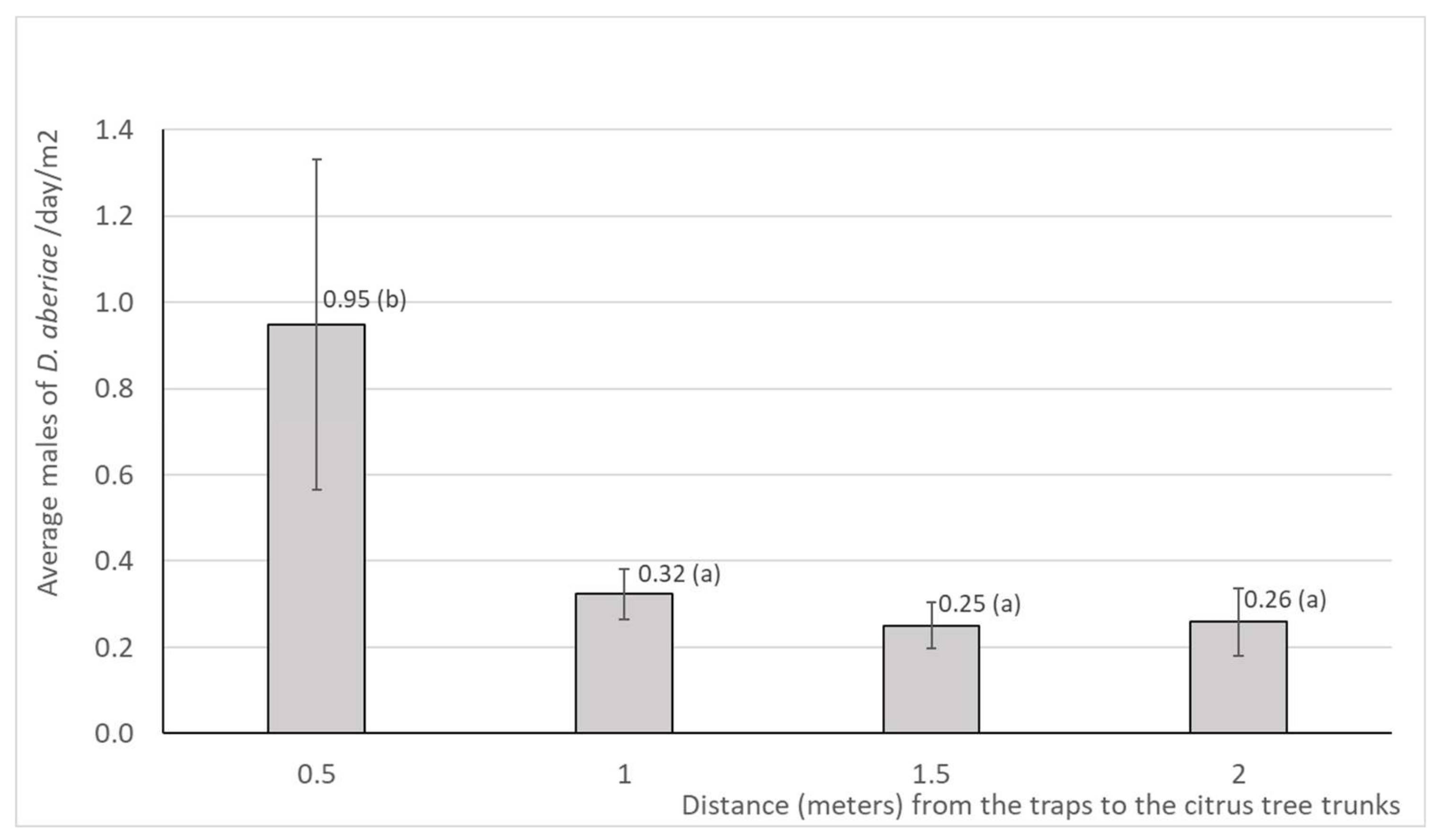

3.1. Soil distribution of D. aberiae males

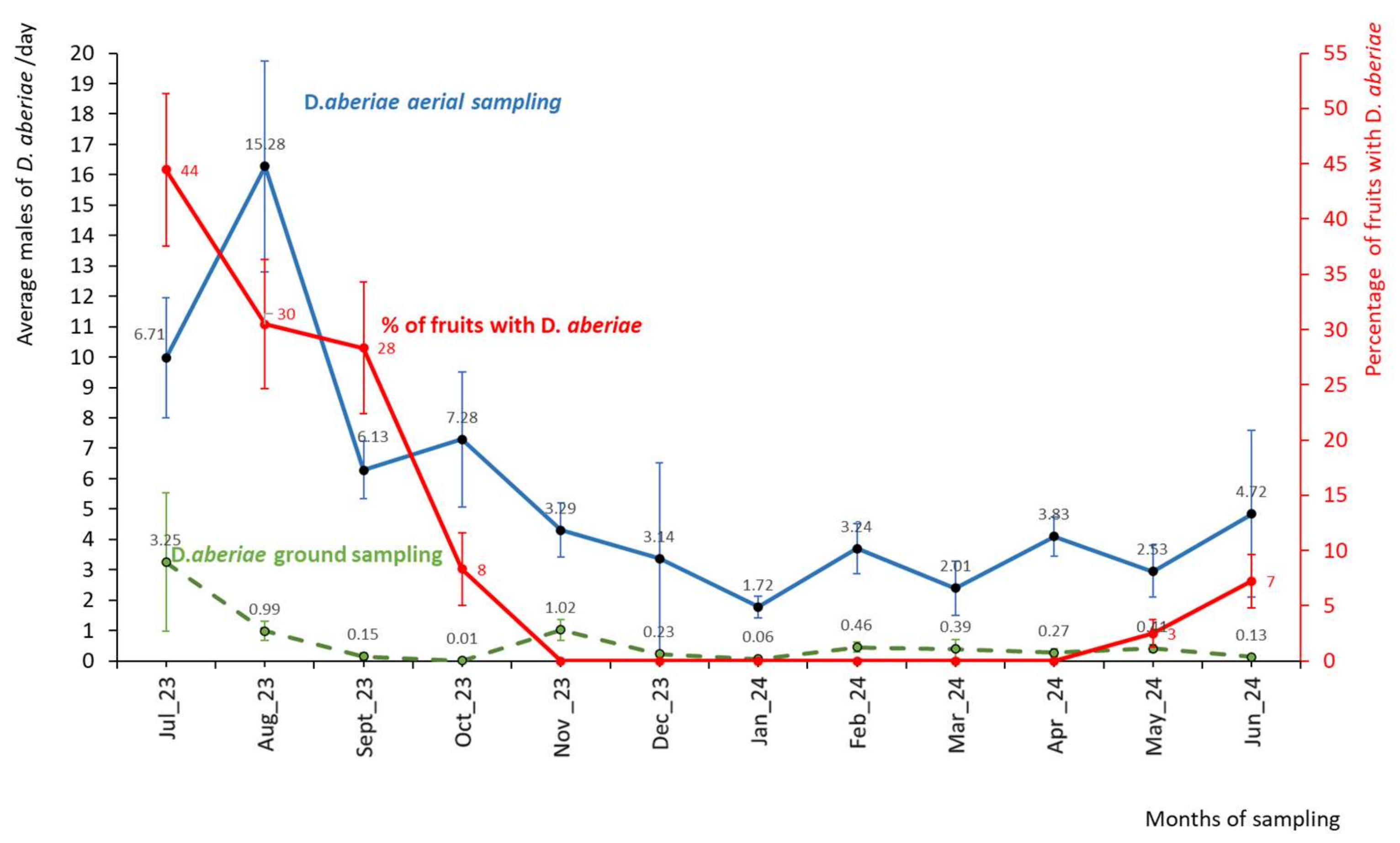

3.2. Above and belowground D. aberiae seasonal evolution

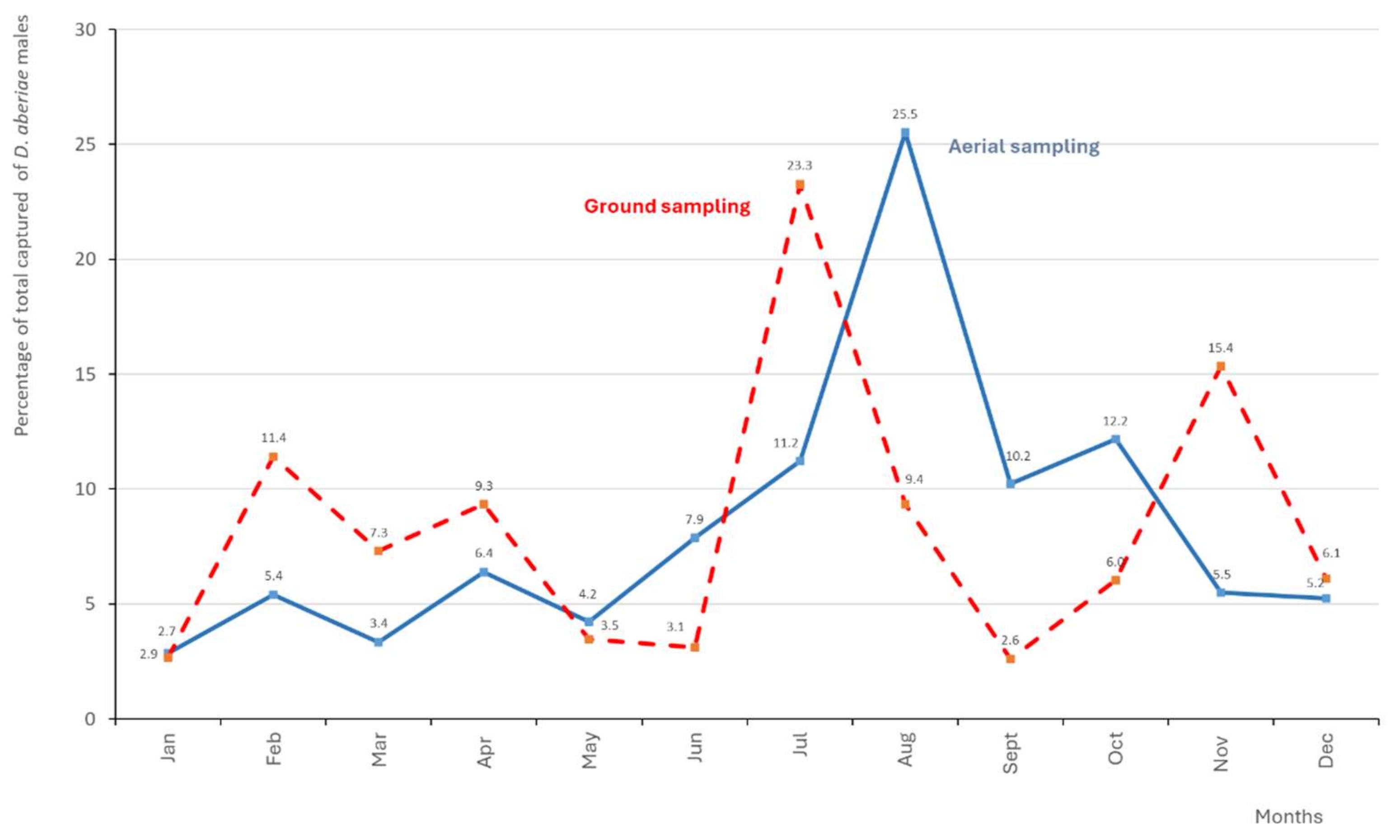

3.3. Male distribution of D. aberiae over the year

3.4. Fruit damage level

3.5. Presence and abundance of natural enemies belowground

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPM | Integrated Pest-Management |

References

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Pajač Živković, I.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. Effect of Climate Change on Introduced and Native Agricultural Invasive Insect Pests in Europe. Insects 2021, 12, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrà, A.; Garcia-Marí, A.; Soto, A. El cotonet de Les Valls, Delottococcus aberiae, nueva plaga de los cítricos. Levante Agrícola 2013, 419, 348–352. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aleixandre-Beltra/publication/259621470_El_cotonet_de_Les_Valls_Delottococcus_aberiae_nueva_plaga_de_los_citricos/links/02e7e535a1553691e6000000/El-cotonet-de-Les-Valls-Delottococcus-aberiae-nueva-plaga-de-los-citricos.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Gavara, A.; Vacas, S.; Navarro-Llopis, V. Geographic Location, Population Dynamics, and Fruit Damage of an Invasive Citrus Mealybug: The Case of Delottococcus aberiae De Lotto in Eastern Spain. Insects 2024, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAPA (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación). Plan de Acción de Delottococcus aberiae (De Lotto). Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/sanidad-vegetal/plan_accion_d_aberiae_mayo2024_tcm30-684109.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Soto, A.; Benito, M.; Puig Bargués, J.; Mocholí, S.; Martínez-Blay, V. Avances en la aplicación del control biológico del cotonet Delottococcus aberiae (De Lotto) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Phytoma España 2020, 318, 26–30. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8412618 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Tena, A.; García-Bellón, J.; Urbaneja, A. Native and naturalized mealybug parasitoids fail to control the new citrus mealybug pest Delottococcus aberiae. J Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacas, S.; Navarro, I.; Marzo, J.; Navarro-Llopis, V.; Primo, J. Sex pheromone of the invasive mealybug citrus pest, Delottococcus aberiae (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). A new monoterpenoid with a necrodane skeleton. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9441–9449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOGV (Diari oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana). Núm. 9961, del 21.10.2024. RESOLUCIÓN de 23 de septiembre de 2024, de la Direcció General de Producción Agrícola y Ganadera, de solicitudes aprobadas (lote número 2) en las ayudas convocadas por la Resolución de 8 de julio de 2022, del director general de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca, por la que se convocan las ayudas de mínimis destinadas a compensar las pérdidas económicas de las explotaciones agrícolas de cítricos y de caqui durante la campaña 2021-2022 como consecuencia de la afección de la plaga de Delottococcus aberiae (De Lotto) y de otros cotonets. 2024, 1-3. Available online: https://dogv.gva.es/datos/2024/10/21/pdf/2024_10030_es.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Martínez-Blay, V.; Perez-Rodriguez, J.; Tena, A.; Soto, A. Density and phenology of the invasive mealybug Delottococcus aberiae on citrus: implications for integrated pest management. J. Pest. Sci. 2018, 91, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Blay, V.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J.; Tena, A., Soto, A. Seasonal Distribution and Movement of the Invasive Pest Delottococcus aberiae (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Within Citrus Tree: Implications for Its Integrated Management. Econ. Entomol. 2018, 111, 6, 2684–2692. [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.C.; Suma, P.; Silva, E.; Blumberg, D.; Mendel, Z. (2004). Management strategies of mealybug pests of citrus in Mediterranean countries. Phytoparasitica 2004, 32, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercher, R.; González, S.; Sánchez-Domingo, A.; Sorribas, J. A Novel Insect Overwintering Strategy: The Case of Mealybugs. Insects 2023, 14, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goolsby, J.; Kirk, A.; Meyerdirk, D.E. Seasonal phenology and natural enemies of Maconellicoccus hirsutus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) in Australia. Fla Entomol. 2002. 85, 494- 498. [CrossRef]

- James, H.C. Sex ratios and the status of the male in Pseudococcinae (Hem. Coccidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 1937, 28, 429–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Li, Z.; Ye, W.; Wang, Y.; Omar, M.A.A.; Ao, Y.; …;Jiang, M. Male mating and female postmating performances in cotton mealybug (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae): effects of female density. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 1145–1150. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Romero, V.; López-Bellido, L.; Lopez-Bellido, R.J. Effect of tillage system on soil temperature in a rainfed Mediterranean Vertisol. Int. Agrophys. 2015, 29, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, T.; Jalali, S.K.; Ramya, S.L.; Prathibha, M. Insecticide resistance and its management. In mealybugs and their Management. Agricultural and Horticultural Crops. Springer, New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 223–229.

- Millar, J.G.; Daane, K.M.; Steven Mcelfresh, J.; Moreira, J.A.; Malakar-Kuenen, R.; Guillén, M.; Bentley, W.J. Development and optimization of methods for using sex pheromone for monitoring the mealybug Planococcus ficus (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae) in California vineyards. J. Econ. Entomol. 2002, 95, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K.E.; Daane, K.M.; Bentley, W.J.; Gill, R.J.; Malakar-Kuenen, R. Mealybugs in California vineyards (Publication 21612); University of California, Agriculture & Natural Resources: Oakland, CA, USA, 2002. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=en&lr=&id=lY-GA8inrnYC&oi=fnd&pg=PA2&dq=17.%09Godfrey,+K.E.%3B+Daane,+K.M.%3B+Bentley,+W.J.%3B+Gill,+R.J.%3B+Malakar-Kuenen,+R.+Mealybugs+in+California+vineyards+&ots=37LfnCv_bm&sig=s8U1-_t5kB0ElIYcqgPfN5oeUW8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Mani, M.; Smitha, M.S.; Najitha, U. Root mealybugs and their management in horticultural crops in India. PMHE. 2016, 22, 103–113. Available online: https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:pmhe&volume=22&issue=2&article=001 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Xu, H.; Humpal, J.A.; Wilson, B.A.L.; Ash, G.J.; Powell, K.S. Mealybug Population Dynamics: A Comparative Analysis of Sampling Methods for Saccharicoccus sacchari and Heliococcus summervillei in Sugarcane (Saccharum sp. Hybrids). Insects 2024, 15, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, C.J. Comparison of the morphology of the adult males of the Rhizoecine, Phenacoccine and Pseudococcine mealybugs (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea) with the recognition of the family Rhizoecidae Williams. Zootaxa 2012, 3291, 1–79. Available online: https://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2012/f/z03291p079f.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Wall, D.H.; Bardgett, R.D.; Behan-Pelletier, V.; Jones, T.H.; Herrick, J.E. Soil Ecology and Ecosystem Services. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. 2012. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=en&lr=&id=J_HTBgrYQdwC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=21.%09Wall,+D.H.,+Bardgett,+R.D.,+Behan-Pelletier,+V.,+Jones,+T.H.,+Herrick,+J.E.+Soil+Ecology+and+Ecosystem+Services.+ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Martínez-Falcón, A.P.; Moreno, C.E.; Pavón, N.P. Litter fauna communities and litter decomposition in a selectively logged and an unmanaged pine-oak forest in Mexico. Bosque 2015, 36, 81–93. Available online: https://revistabosque.org/index.php/bosque/article/view/558 (accessed on 21 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, F.A.; Skvarla, M.J., Fisher, J.R., Dowling, A.P.G., Ochoa, R., Ueckermann, E.A., Bauchan, G.R. Catalogue of snout mites (Acariformes: Bdellidae) of the world. Zootaxa 2016, 152 (1), 001-083. [CrossRef]

- Hayon, I.; Mendel, Z.; Dorchin, N. Predatory gall midges on mealybug pests -diversity, life history, and feeding behavior in diverse agricultural settings. Biol. Control 2016, 99, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso-Guimarães, M.V.; Cruz, M.A.; Martinelli, N.M.; Peronti, A.L.G.B. Description of a new species of cecidomyiid (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) predator of mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) on sugarcane. Pap. Avulsos Zool. 2020, 60, e20206041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pedro, L., Tormos, J., Harbi, A., Ferrara, F., Sabater-Munoz, B., Asís, J.D., & Beitia, F.J.. Acción conjunta de los parasitoides Aganaspis daci y Diachasmimorpha longicaudata para el control de la mosca mediterránea de la fruta, Ceratitis capitata: ¿Una estrategia recomendable?. Levante Agrícola 2020, 450, 5–13. Available online: https://redivia.gva.es/bitstream/handle/20.500.11939/6404/2020_de-Pedro_Acci%c3%b3n.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Moser, M.; Salden, T.; Mikó, I.; Krogmann, L. Synthesis of the host associations of Ceraphronoidea (Hymenoptera): a key to illuminating a dark taxon. ISD, 2024. 8 (6), 6. [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.S.; Valentine, E.W. Mymaridae (Insecta: Hymenoptera) – introduction, and review of genera. Fauna N. Z. 1989, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.T. Systematics, biology, and hosts of the Mymaridae and Mymarommatidae (Insecta: Hymenoptera):1758-1984. Entomography 1986, 4, 185–243. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John-Huber-2/publication/278016087_Premiere_mention_en_Suisse_de_la_famille_Mymarommatidae_Hymenoptera/links/5745abb108ae9f741b42d971/Premiere-mention-en-Suisse-de-la-famille-Mymarommatidae-Hymenoptera.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Lotfalizadeh, H.; Iranpoor, A.; Mohammadi-Khoramabadi, A. First reports of temporally soil-dwelling Chalcidoidea (Hymenoptera). Biharean Biologist. 2019. 13, 89-93. Available online: http://biozoojournals.ro/bihbiol/index.html (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Tscharntke, T.; Klein, A.M.; Kruess, A.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Thies, C. Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity–ecosystem service management. Ecology letters. 2005, 8, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorribas, J.; González, S.; Domínguez-Gento, A.; Vercher, R. Abundance, movements and biodiversity of flying predatory insects in crop and non-crop agroecosystems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommaggio, D.; Peretti, E.; Burgio, G. The effect of cover plants management on soil invertebrate fauna in vineyard in Northern Italy. BioControl 2018, 63, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Campos, C.; Pekas, A.; Aguilar, A.; Garcia-Marí, F. Factors influencing citrus fruit scarring caused by Pezothrips kellyanus. J Pest Sci. 2013, 86, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, M.; Grossman, J.M.; Reberg-Horton, S.C.; Brinton, C.; Crozier, C. Nitrogen delivery from legume cover crops in no-till organic corn production. Agron. J. 2011. 103, 1578-1590. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, J.: Calvo, J.; Urbaneja, A.; Tena, A. The soil mite Gaeolaelaps (Hypoaspis) aculeifer (Canestrini)(Acari: Laelapidae) as a predator of the invasive citrus mealybug Delottococcus aberiae (De Lotto)(Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae): Implications for biological control. Biol. Control 2018, 127, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Campos, C.; Pekas, A.; Moraza, M.L.; Aguilar, A.; Garcia-Marí, F. Soil-dwelling predatory mites in citrus: Their potential as natural enemies of thrips with special reference to Pezothrips kellyanus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Biol. Control 2012, 63, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.J.; Gaugler. R. Factors limiting short-term persistence of entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Appl. Entomol. 2004, 128, 250–253. [CrossRef]

- Le Vieux, P.D.; Malan, A.P. Prospects for using entomopathogenic nematodes to control the vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus, in South African vineyards. SAJEV. 2015, 36, 59–70. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajev/v36n1/12.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Guo, L., Maimaiti, Y., Mijit, M., & Qiu, D. (2012). Entomopathogenic fungi as microbial biocontrol agent. Mol. Plant Breed. 2012, 3, 63–79. Available online: http://mpb.sophiapublisher.com (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Ecology of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in temperate agroecosystems: potential for conservation biological control. Biol. Control. 2007, 43, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutha, M.; Gulsar Banu, J. Variation in Mycosis of Entomopathogenic Fungi on Mealybug, Paracoccus marginatus (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 2015, 87, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathulwe, L.L., Malan, A.P., & Stokwe, N.F. Laboratory screening of entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes for pathogenicity against the obscure mealybug, Pseudococcus viburni (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2021. 32, 397–417. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, I.; Kim, J.S. Soil treatment with Beauveria and Metarhizium to control fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, during the soil-dwelling stage. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 2024, 27, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FRUIT DAMAGE LEVEL (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2023 | 31.75 ± 5.38 | 57.92 ± 4.70 | 8.92 ± 2.30 | 1.42 ± 0.61 |

| 2024 | 55.78 ± 4.21 | 40.31 ± 4.50 | 1.48 ± 0.48 | 2.42 ± 1.11 |

| Shapiro p (2023) | 0.049 | 0.623 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Shapiro p (2024) | 0.151 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

|

Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

W=22.5 p= 0.007 |

W=36.5 p= 0.003 |

W=5.0 p= 0.005 |

W=19 p= 0.68 |

| Significant (α = 0.05) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Arthropods | Distance to trunk (m) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class and Order | Superfamily | Family | Genus | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | Total |

| Insecta | 46 | 42 | 36 | 49 | 173 | |||

| Diptera | 8 | 12 | 14 | 30 | 64 | |||

| Sciaroidea | Cecidomyiidae | 6 | 12 | 14 | 29 | 61 | ||

| Empidoidea | Hybotidae | Platypalpus spp. | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Coleoptera | Staphylinoidea | Staphylinidae | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 16 | |

| Hymenoptera | 33 | 28 | 17 | 15 | 93 | |||

| Ceraphronoidea | Ceraphronidae | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 15 | ||

| Megaspilidae | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Chalcidoidea | Encyrtidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Eulophidae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Mymaridae | Alaptus spp. | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 17 | ||

| Camptoptera spp | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Others | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | |||

| Others | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Cynipoidea | Cynipidae | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Ichneumonoidea | Ichneumonidae | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||

| unidentiffied | 0 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 15 | |||

| Platygastroidea | Scelionidae | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Others | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 8 | |||

| Arachnida | 91 | 88 | 72 | 150 | 401 | |||

| Araneae | 13 | 17 | 15 | 20 | 65 | |||

| Trombidiformes | Bdelloidea | Bdellidae | 66 | 57 | 54 | 124 | 301 | |

| Pseudoscorpionida | 12 | 14 | 3 | 6 | 35 | |||

| Order | Superfamily | Family | Genus | ANOVA (Fratio; Pvalue) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moth (M) | Distance (D) | MxD | ||||

| Diptera | Sciaroidea | Cecidomyiidae | 0.94 (0.503) | 0.90 (0.441) | 1.22 (0.193) | |

| Coleoptera | Staphylinoidea | Staphylinidae | 6.05 (0.000)* | 0.47 (0.701) | 0.82 (0.758) | |

| Hymenoptera | Ceraphronoidea | Ceraphronidae | 1.53 (0.119) | 0.14 (0.937) | - | |

| Mymaridae | Alaptus | 2.28(0.011)* | 0.13 (0.944) | 0.28 (1.00) | ||

| Platygastroidea | Scelionidae | 0.98 (0.463) | 0.37 (0.774) | 0.79 (0.792) | ||

| Trombidiformes | Bdelloidea | Bdellidae | 13.97(0.000)* | 2.08 (0.103) | 1.00 (0.474) | |

| Pseudoscorpionida | 7.62 (0.000)* | 0.82 (0.482) | 0.52 (0.989) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).