Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Morphological Variation in Strip Flowers

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Collection of Beneficial Arthropods in Floral Strips

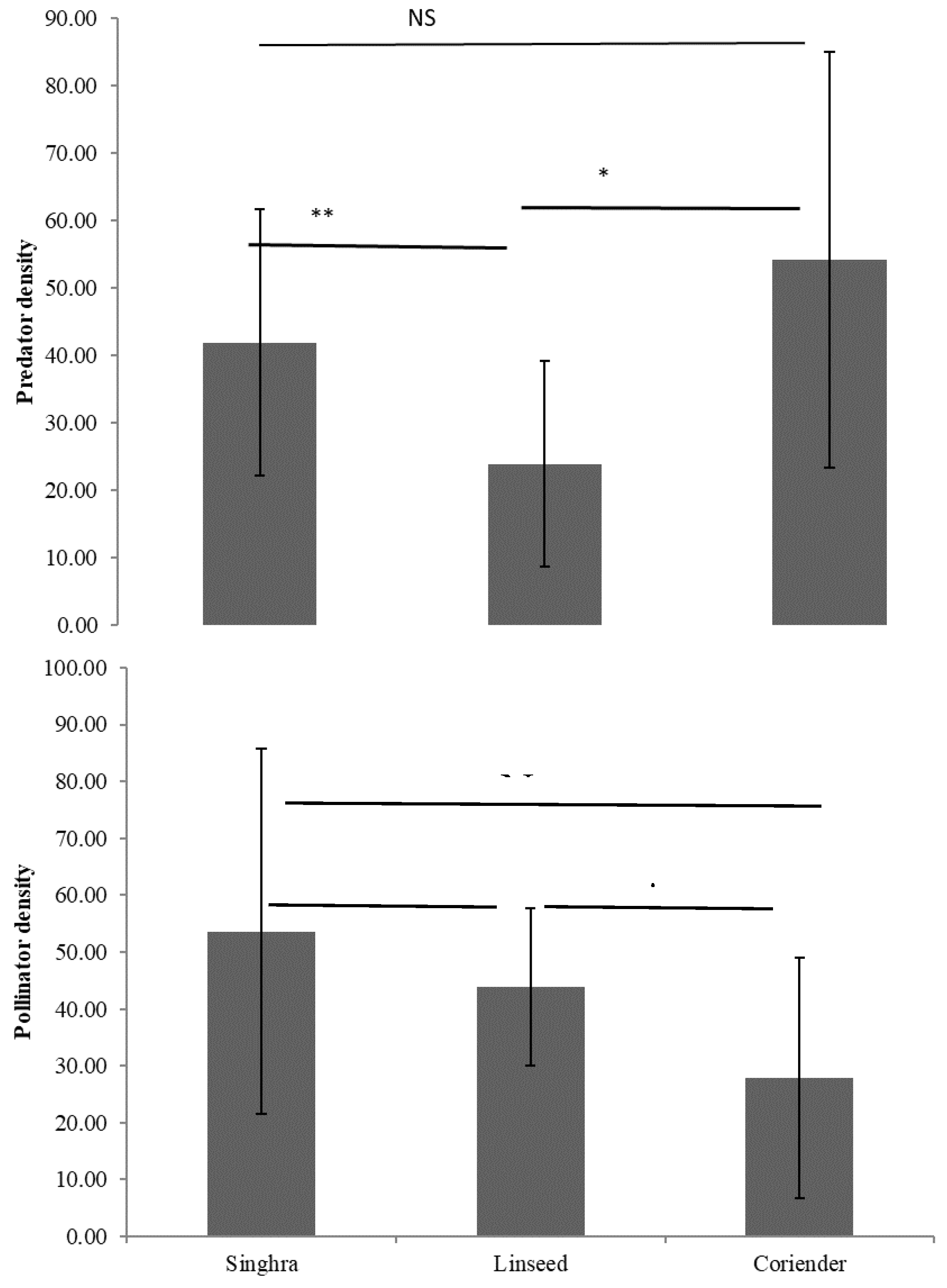

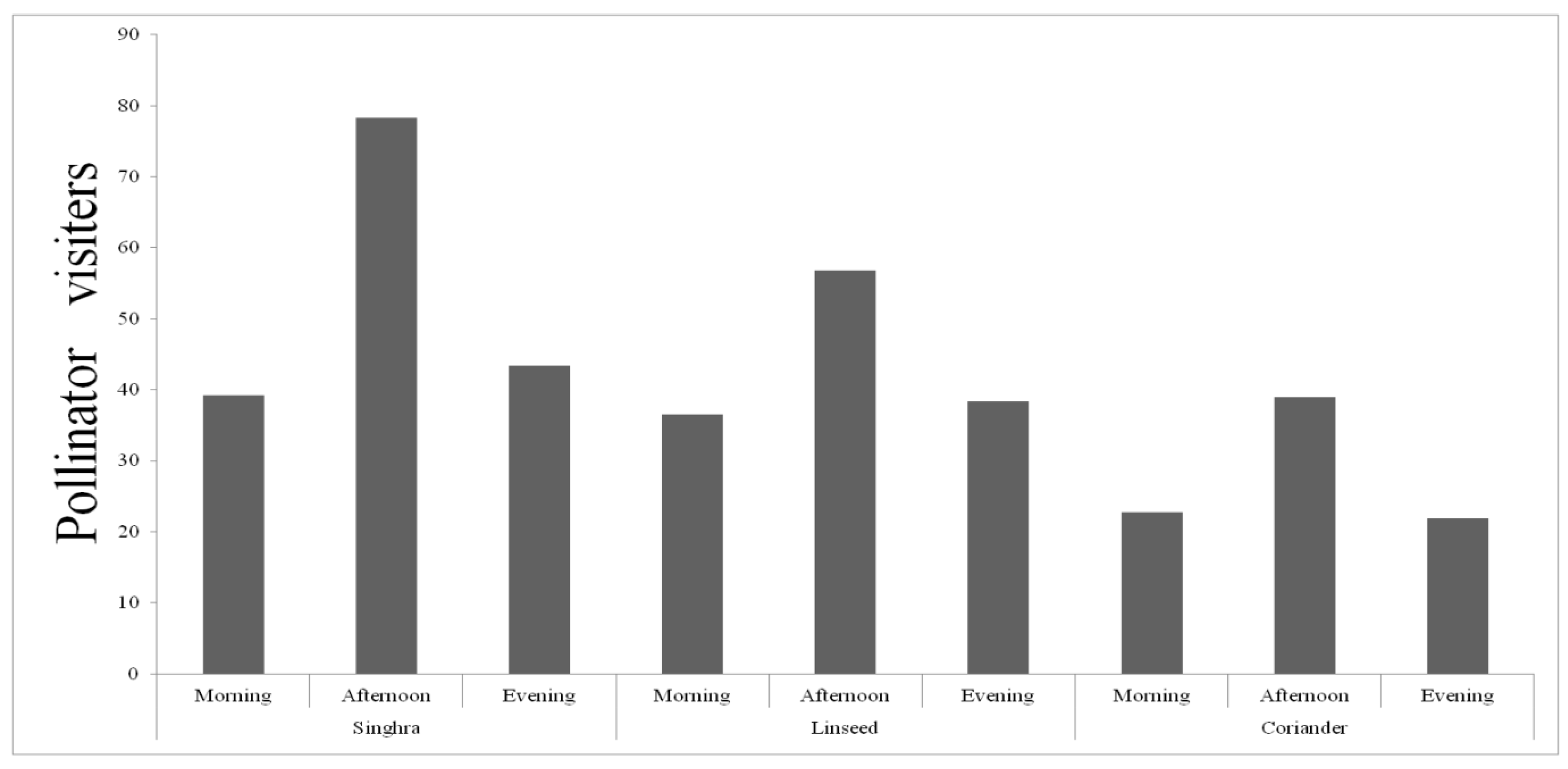

3.2. Effect of Floral Strips on Predators and Pollinators

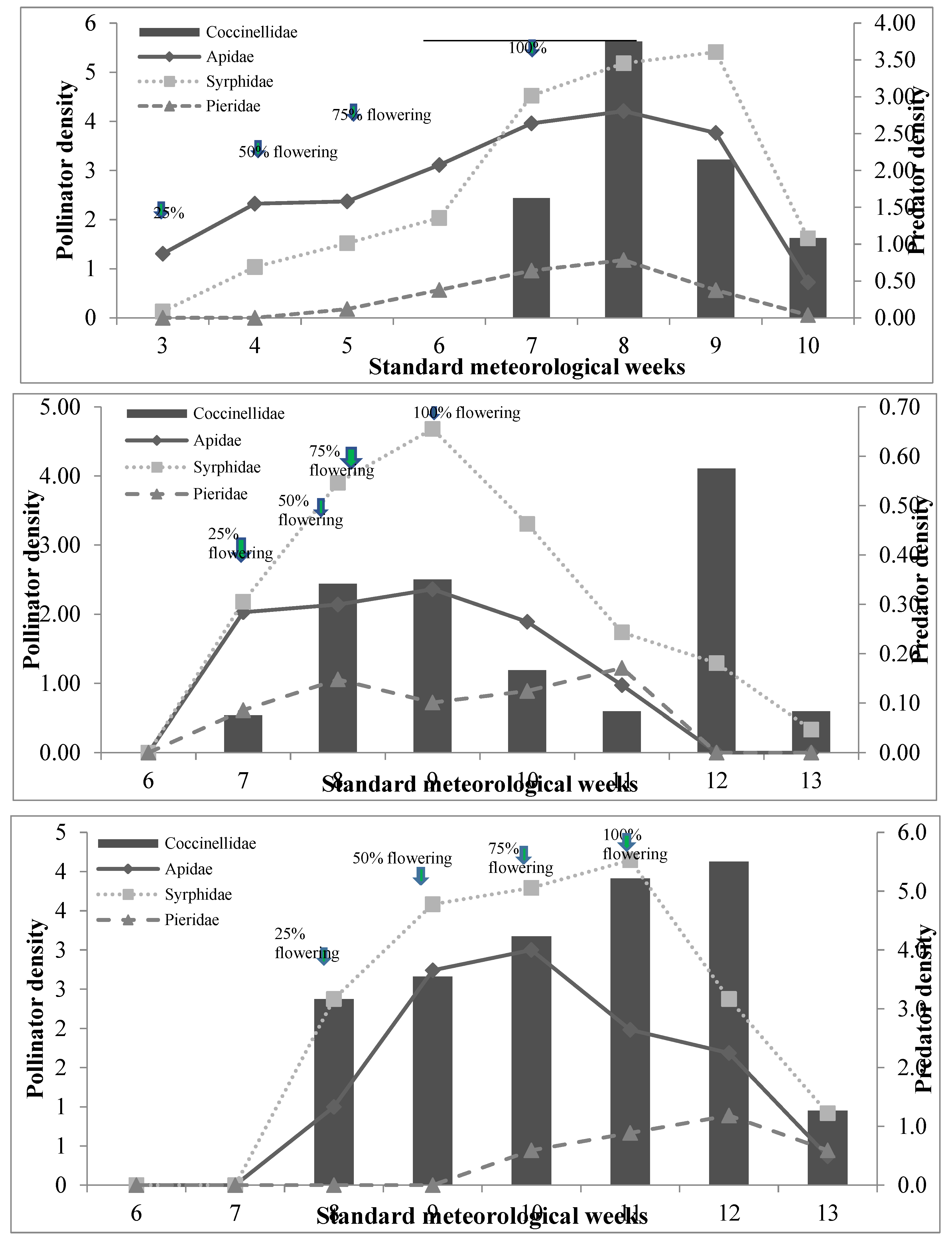

3.3. Population Dynamics of Predators and Pollinators on Floral Strips

3.4. Impact of Abiotic Factors on Predators and Pollinators

3.5. Interaction of Pest and Predator in Relation to Crop Growth Stages

4. Discussion

4.1. Collection of Beneficial Arthropods in Floral Strips

4.2. Effect of Floral Strip on Predators and Pollinators

4.3. Population Dynamics of Predators and Pollinators on Floral Strips

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miransari, M.; Smith, D. Sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ) production in saline fields: a review, Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. These are the top 10 countries that produce the most wheat. Word Economic Forum. 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/top-10-countries-produce-most-wheat/ (accessed on day month year).

- Gaur, N.; Mogalapu, S. 2018. Pests of wheat. In. Omkar (eds) Pests and their management. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Houser, J.; Preiss, E.; White, O.; Fang, H.; Mesnick, L.; Barsky, T.; Tariche, S.; Schreck, J.; Alpert, S. Water resources: agriculture, the environment, and society. Biomed. Sci. 1997, 47, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deol, G.S.; Gill, K.S.; Brar, J.S. Aphid outbreak on wheat and barley in Punjab. Newsletter Aphid Soc. India. 1987, 6, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Farook, U.B.; Khan, Z.H.; Ahad, I.; Maqbool, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Rafieq, I.; Sultan, N. A review on insect pest complex of wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ). J. Entomol. Zool. Studies. 2019, 7, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, W.; Linke, W. Studies of cereal aphids; their occurrence, effect on yield in relation to density levels and their control. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1974, 77, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Stoltz, R.L.; Ni, X.Z. Damage to wheat by Macrosiphum avenae (F. ) (Homoptera: Aphididae) in northwest China. J. Econ. Entomol. 1986, 79, 1688–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguy, S.; Dedryver, C.A. Reduced BYDV–PAV transmission by the grain aphid in a Triticum monococcum line. European J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 123, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.P.; Paul, V.L.; Slater, R.; Warren, A.; Denholm, I.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S. A mutation (L1014F) in the voltage gated sodium channel of the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae, is associated with resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. Pest Manage. Sci. 2014, 70, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; Folke, C. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science. 2015, 347, 6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P. Ecological intensification of agriculture-sustainable by nature. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzman, M.; Bàrberi, P.; Birch, A.N.E.; Boonekamp, P.; Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, S.; Graf, B.; Hommel, B.; Jensen, J.E.; Kiss, J.; Kudsk, P.; Lamichhane, J.R. Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá Herrera, R.; Cotes, B. ; Agustí, N; Tasin, M. ; Porcel, M. Using flower strips to promote green lacewings to control cabbage insect pests. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wratten, S.; Lavandero, B.; Scarratt, S.; Vattala, D. Conservation biological control of insect pests at the landscape scale. IOBC WPRS Bull. 2003, 26, 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, D.A.; Wratten, S.D.; Gurr, G.M. Habitat management to conserve natural enemies of arthropod pests in agriculture. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2000, 45, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurr, G.M.; Wratten, S.D.; Landis, D.A.; You, M. Habitat management to suppress pest populations: progress and prospects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, A.C.; Rehan, S.M. Supporting bees in cities: how bees are influenced by local and landscape features. Insects. 2021, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.X.; Zhu, P.Y.; Gurr, G.M.; Zheng, X.S.; Read, D.M.; Heong, K.L.; Xu, H.X. Mechanisms for flowering plants to benefit arthropod natural enemies of insect pests: Prospects for enhanced use in agriculture. Insect Sci. 2014, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, J.; Murrell, E.; Spiesman, B.J.; Kim, T.N. Native flowering border crops attract high pollinator abundance and diversity, providing growers the opportunity to enhance pollination services. Environ. Entomol. 2022, 51, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wratten, S.D.; Gillespie, M.; Decourtye, A.; Mader, E.; Desneux, N. Pollinator habitat enhancement: benefits to other ecosystem services. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 159, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Kleijn, D.; Williams, N.M.; Tschumi, M.; Blaauw, B.R.; Bommarco, R.; Campbell, A.J.; Dainese, M.; Drummond, F.A.; Entling, M.H.; Ganser, D. , The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: a quantitative synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, A.K.; Landis, D.A. Plant characteristics associated with natural enemy abundance at Michigan native plants. Environ. Entomol. 2007, 36, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Karp, D.S.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Batáry, P.; DeClerck, F.; Gratton, C.; Hunt, L.; Ives, A.; Jonsson, M.; Larsen, A.; Martin, E.A. , When natural habitat fails to enhance biological pest control – Five hypotheses. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 204, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattala, H.D.; Wratten, S.D.; Phillips, C.B.; Wäckers, F.L. The influence of flower morphology and nectar quality on the longevity of a parasitoid biological control agent. Biol. Control. 2006, 39, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, S.W.; Thornburg, R.W. 2007. Nectar chemistry. In Nectaries and nectar (pp. 215-264). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Yan, J.; Wang, G.; Sui, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. Pollinator responses to floral colour change, nectar and scent promote reproductive fitness in Quisqualisindica (Combretaceae). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, O.; Géneau, C.E.; Belz, E.; Weishaupt, B.; Förderer, G.; Moos, S.; Ditner, N.; Juric, I.; Luka, H. Wildflower companion plants increase pest parasitation and yield in cabbage fields: Experimental demonstration and call for caution. Biol. Control. 2014, 76, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, U.; Porcel, M.; Świergiel, W.; Wivstad, M. 2016. Habitat manipulation– as a pest management tool in vegetable and fruit cropping systems, with the focus on insects and mites. SLU, EPOK – Centre for Organic Food & Farming, Uppsala. https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/30032/1/biokontrollsyntes_web.

- Van der Niet, T.; Jürgens, A.; Johnson, S.D. Pollinators, floral morphology and scent chemistry in the southern African orchid genus Schizochilus. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2010, 76, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajulee, M.N.; Montandon, R.; Slosser, J.E. Relay intercropping to enhance predators of the cotton aphids in Texas cotton. Int. J. Pest Manage. 1997, 43, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajulee, M.N.; Slosser, J.E. Evaluation of potential relay strip crops for predator enhancement in Texas cotton. Int. J. Pest Manage. 1999, 45, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltham, H.; Park, K.; Minderman, J.; Goulson, D. Experimental evidence that wildflower strips increase pollinator visits to crops. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 3523–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E.G.; MacRae, I.V.; Philips, C.R. Floral plantings in large-scale commercial agroecosystems support both pollinators and arthropod predators. Insects. 2021, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serée, L.; Chiron, F.; Valantin-Morison, M.; Barbottin, A.; Gardarin, A. Flower strips, crop management and landscape composition effects on two aphid species and their natural enemies in faba bean. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 331, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjwal, N.; Kumar, Y.; Khan, M.S. Flower-visiting insect pollinators of Brown Mustard, Brassica juncea (L. ) Czern and Coss and their foraging behaviour under caged and open pollination. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 9, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, S.M.; Mahfouz, H.M.; Blal, E.F.A.H.; Said, M.; Mahmoud, M.F. Diversity of insect pollinators with reference to their impact on yield production of canola (Brassica napus L. ) in Ismailia, Egypt. Pesticidi i fitomedicina. 2015, 30, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Amin, F.; Sohail, K.; Shah, S.F.; Aziz, A. Incidence of different insect visitors and their relative abundance associated with coriander (Coriandrum sativum) in district Charsadda. Pure Appl. Biol. 2018, 7, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy, C.; Noël, G.; Hatt, S.; Uyttenbroeck, R.; Van de Meutter, F.; Genoud, D.; Francis, F. Flower strips in wheat intercropping system: effect on pollinator abundance and diversity in Belgium. Insects. 2018, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raderschall, C.A.; Lundin, O.; Lindström, S.A.; Bommarco, R. Annual flower strips and honeybee hive supplementation differently affect arthropod guilds and ecosystem services in a mass-flowering crop. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunschke, J.; Lunau, K.; Pyke, G.H.; Ren, Z.X.; Wang, H. Flower color evolution and the evidence of pollinator-mediated selection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 617851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.B. Agronomic aspects of strip intercropping lettuce with alyssum for biological control of aphids. Biol. Control. 2013, 65, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Mori, N.; Battisti, A.; Ashraf, M. Effect of Brassica napus, Medicago sativa, Trifolium alexandrinum and Allium sativum strips on the population dynamics of Sitobean avenae and predators in wheat ecosystem. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016, 4, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Amala, U.; Shivalingaswamy, T.M. Effect of intercrops and border crops on the diversity of parasitoids and predators in agroecosystem. Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control. 2018, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee-Finley, K.; Ryan, M.R. Advancing intercropping research and practices in industrialized agricultural landscapes. Agriculture 2018, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliga, G.A.; Arlotti, D. Wheat-pea intercrop affects activity density and bio control potential of generalist predators. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Haussler, J.; Sahlin, U.; Baey, C.; Smith, H.G.; Clough, Y. Pollinator population size and pollination ecosystem service responses to enhancing floral and nesting resources. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 1898–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Saeed, S.; Sajjad, A.; Whittington, A. In search of the best pollinators for canola (Brassica napus L. ) production in Pakistan. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2011, 46, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, V.; Khan, M.S. Impact of honey bee pollination on pod set of mustard (Brassica juncea L. : Cruciferae) at Pantnagar. The Bioscan 2014, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, T.; Aziz, M.A.; Naeem, M.; Ahmed, M.S.; Bodlah, I. Diversity and relative abundance of pollinator fauna of canola (Brassica napus L. Var Chakwal Sarsoon) with managed Apis mellifera L. in Pothwar Region, Gujar Khan, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Zool. 2018, 50, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, A.F. Cross pollination of fibre flax. Bee world. 1945, 26, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, M.R.; Luna, J.M. Relative attractiveness of potential beneficial insectary plants to aphidophagous hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Environ. Entomol. 2000, 29, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, M.D.; Luna, J.M.; Jepson, P.C.; Wratten, S.D. Relative frequencies of visits to selected insectary plants by predatory hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae), other beneficial insects, and herbivores. Environ. Entomol. 2006, 35, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, B.N.; Bugg, R.L.; Daane, K.M. Attractiveness of common insectary and harvestable floral resources to beneficial insects. Biol. Control. 2011, 56, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós-Jiménez, R.; Pineda, A.; Fereres, A.; Marcos-García, M.Á. Feeding preferences of the aphidophagous hoverfly Sphaerophoria rueppellii affect the performance of its offspring. Biol. Control. 2014, 59, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquart, E.; Hemptinne, J.L. Selectivity in the exploitation of floral resources by hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphinae). Ecography. 2000, 23, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, K.; Tschumi, M.; Lutter, S.; Ramseier, H.; Zingg, S. Competition and facilitation effects of semi-natural habitats drive total insect and pollinator abundance in flower strips. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barda, M.; Karamaouna, F.; Kati, V.; Perdikis, D. Do patches of flowering plants enhance insect pollinators in apple orchards? . Insects 2023, 14, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, M.; Sharma, H.K.; Thakur, R.K.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Rana, K.; Thakur, M.; Ram, B. Diversity of insect pollinators in reference to seed set of mustard (Brassica juncea L. ). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divija, S.D.; Jayanthi, P.K.; Varun, Y.B.; Kumar, P.S.; Krishnarao, G.; Nisarga, G.S. Diversity, abundance and foraging behaviour of insect pollinators in Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus L.). J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 2022, 25, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, W.G. Effects of pollination on floral attraction and longevity. J. Exp. Bot. 1997, 48, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, M.; Ali, H.; Ahmad, S.; Said, F.; Khan, K.A.; Bashir, M.A.; Ali, H. Insect pollinators diversity and abundance in Eruca sativa Mill. (Arugula) and Brassica rapa L.(Field mustard) crops. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.C.; Chen, J.L.; Cheng, D.F.; Zhou, H.B.; Sun, J.R.; Liu, Y.; Francis, F. Impact of wheat–mung bean intercropping on English grain aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) populations and its natural enemy. J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. 2012. Use of intercropping and infochemical releasers to control aphids in wheat (Doctoral dissertation, ULiège. GxABT-Liège Université. Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech).

- Wang, W.L.; Liu, Y.; Ji, X.L.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.B. Effects of wheat-oilseed rape or wheat-garlic intercropping on the population dynamics of Sitobion avenae and its main natural enemies. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 19, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, K.; Chuhan, M.A.; Rasul, A.; Arshad, I. Intercropping of wheat and oilseed crops reduces wheat aphid, Sitobion avenae (Fabricius) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) incidences: a field study. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 56, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha.

- Togni, P.H.; Venzon, M.; Muniz, C.A.; Martins, E.F.; Pallini, A.; Sujii, E.R. Mechanisms underlying the innate attraction of an aphidophagous coccinellid to coriander plants: Implications for conservation biological control. Bio. Control. 2016, 92, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, J.A.; Vandenberg, N.J.; McHugh, J.V.; Forrester, J.A.; Ślipiński, S.A.; Miller, K.B.; Shapiro, L.R.; Whiting, M.F. The evolution of food preferences in Coccinellidae. Bio. Control. 2009, 51, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common name | Scientific name | Intensity | Family | Order | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western honey bee | Apis mellifera Linnaeus | High | Apidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Indian bee | Apis cerana Fabricius | High | Apidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Little honey bee | Apis florae Fabricius | Medium | Apidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Rock bee | Apis dorsata Fabricius | Medium | Apidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Carpenter bee | Xylocopa sp. | Medium | Apidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Sweet bee | Halictus sp.1 | Low | Halictidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Sweet bee | Halictussp.2 | Low | Halictidae | Hymenoptera | Pollinators |

| Hover fly | Ceriana sp. | Low | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Drone fly | Eristalistenax Linnaeus | Medium | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Hover fly | Eristalinustabanoides(Jaenicke) | Low | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators/ predator |

| Lagoon Flies | Eristalinusobscuritarsus(Meijere) | Medium | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Marmalade hoverfly | Episyrphusbalteatus(De geer) | High | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Hoverfly | Eupeodes sp. | High | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators/ predator |

| European hoverfly | Metasyrphus corolla (Fabricius) | Medium | Syrphidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Snout fly | Stomorhinasp. | Low | Rhiniidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Housefly | Musca sp. | Low | Muscidae | Diptera | Pollinators |

| Plain tiger | Danauschrysippus | Medium | Nymphalidae | Lepidoptera | Pollinators |

| Painted lady | Venessacardui(Linnaeus) | Low | Nymphalidae | Lepidoptera | Pollinators |

| Cabbage butterfly | Pieris brassicae | High | Pieridae | Lepidoptera | Pollinators |

| African clouded yellow | Coliaselecto(Linnaeus) | Low | Pieridae | Lepidoptera | Pollinators |

| Howk moth | Macroglossumstellatarum | Low | Sphingidae | Lepidoptera | Pollinators |

| Seed bug | Graptostethusservus(Fabricius) | Low | Lygaeidae | Hemiptera | Pollinators |

| Shield bug | Dolycoris indicus Stal. | Low | Pentatomidae | Hemiptera | Pollinators |

| Lychee Shield bug | Chrysocorispatricius (Fabricius) | Medium | Scutelleridae | Hemiptera | Pollinators |

| Red pumpkin beetal | Raphidopalpafoveicollis | Low | Chrysomelidae | Coleoptera | Pollinators |

| Seven spotted ladybird beetle | Coccinella septempunctata Linnaeus | High | Coccinellidae | Coleoptera | Predator |

| Six-spotted zigzag ladybird | Cheilomenes sexmaculata (Fabricius) | High | Coccinellidae | Coleoptera | Predator |

| Transverse ladybird | Coccinella transversalis (Fabricius) | Medium | Coccinellidae | Coleoptera | Predator |

| Spotted amber ladybeetle | Hippodamiavariegata(Goeze) sp.1 | Low | Coccinellidae | Coleoptera | Predator |

| Harmonia ladybeetle | Harmonia dimidiate (Fabricius) | Medium | Coccinellidae | Coleoptera | Predator |

| Crop name | Flower type | Pollination type | Flower colour | Flowers per plant | Total flowers (Number) |

Diameter of flower (cm) | Ovary length (cm) | Type of pollen | Blooming period (days) | Total pollinators (Number) |

Total Predators (Number) |

|||

| 25% flowering | 50% flowering | 75% flowering | 100% flowering | |||||||||||

| Singhra | Cross Shaped | Cross | Purple and white combination | 14 ± 3# | 24 ± 4 | 38 ± 8 | 48 ± 8 | 124 | 3.2 ± 0.19 | 1.6 | Oval | 49 | 2895 | 544 |

| Linseed | Disk Shape | Cross | Blue | 6 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 32 | 2.4±0.16 | 0.8 | Spherical | 28 | 1185 | 310 |

| Coriander | Asymmetrical | Cross | White | 9 ± 1 | 14 ± 3 | 22 ± 2 | 31 ± 2 | 76 | 1.2 ± 0.11 | 0.2 | Rod | 33 | 836 | 704 |

| Factors | Aphid population | Pollinator population | Predator population | ||||

| Singhra | Linseed | Coriander | Singhra | Linseed | Coriander | ||

| Maximum Temp (0C) | 0.279 | 0.570 | 0.134 | 0.644 | 0.395 | 0.152 | 0.721* |

| Minimum Temp (0C) | 0.392 | 0.356 | 0.516 | 0.943** | 0.187 | 0.162 | 0.889** |

| Maximum RH (%) | -0.049 | -0.020 | 0.168 | -0.498 | -0.008 | 0.085 | -0.618 |

| Minimum RH (%) | -0.010 | 0.045 | 0.265 | -0.499 | 0.236 | 0.131 | -0.621 |

| Rainfall (mm) | -0.834* | -- | -0.467 | 0.138 | -- | 0.125 | 0.381 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).