1. Introduction

The term ‘‘clean coal’’ applies to coal with reduced residue matter as compared to raw coal. Coal beneficiation, as a coal cleaning technology, is a process of separation of pure matter of coal from the associated inorganic mineral impurities like sand, stones, and sulfide [

1]. Coal beneficiation, as a coal cleaning technology, is a process of separation of pure matter of coal from the associated inorganic mineral impurities like sand, stones, and sulfide [

1]. With the depletion of coal resources, the coal slime, which was used to discard due to difficulty to segregation, has become an important available resource. One of the more promising methods, called oil agglomeration, for cleaning coal involves suspending finely ground coal in water and selectively agglomerating the more hydrophobic and oleophilic components with oil as the suspension is agitated vigorously [

2]. Based on the differences in the surface hydrophobicity of organic and inorganic minerals in coal, oil agglomeration utilized neutral oil to achieve the efficient separation of coal slimes with a size fraction less than 0.5 mm [

3,

4].

Clean coal recovery and separation efficiency of the oil agglomeration process depend on many operational factors, including pulp density, oil type and dosage, agitation rate, agglomeration time, PH of the suspension, and coal slime properties [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The effect of the particle size distribution of coal slime on oil agglomeration performance was investigated by researchers[

8,

10]. Results indicated the finer coal slime achieved cleaner agglomerates than coarser coal slime, given a lower amount yield of clean coal. Allen et al.

2 and Butler et al. [

8] studied the effect of pulp PH on coal oil agglomeration and observed that the pulp in acidic conditions was more conductive to coal fines beneficiation. Moreover, Chary and Dastidar [

11] adopted different types of vegetable oils including Karanja oil, Jatropha oil, and Rubber seed oil to achieve acceptable separation performance in oil agglomeration. Ünal et al. [

7,

12] and Cebeei et al. [

13] investigated the effect of various bridging liquids on the agglomeration performance of coal fines. Furthermore, the effects of the pulp concentration, the oil dosage, and the agitation speed were also evaluated by combustible recovery of the coal slime oil agglomeration process [

4,

5,

14,

15]. However, most of these studies focused on the effects of a single factor without sufficiently considering the interactional effects between variables. Therefore, it is essential to study the interactions between various factors in-depth based on a multi-factor orthogonal experimental design.

The interaction effects between variables on the separation performance of oil agglomeration have been investigated in recent years, employing some experimental designs, such as the Box-Wilson statistical design [

16], Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) approach [

17], Box-Behnken design [

6,

18]. Despite a few novel findings using various methods to find out the influencing degree of various factors on the cleaning efficiency of coal fines in oil agglomeration. However, reliance on a single evaluation metric (e.g. combustible recovery) risks suboptimal process design, as it neglects trade-offs between yield and ash content. This limitation is addressed through our tripartite efficiency index (Eq. 4). Therefore, it is urgent to investigate the mutual effects of significant parameters on the performance of oil agglomeration for coal slimes with multi evaluation indexes in-depth.

While prior studies have advanced our understanding of oil agglomeration, critical gaps remain. First, existing research predominantly focuses on single-factor optimization (e.g. oil dosage or agitation rate) while neglecting the synergistic or antagonistic interactions between operational parameters such as pulp density, oil dosage, and agitation rate

5–9. This oversimplification limits industrial applicability, as real-world processes require balancing competing objectives (e.g. maximizing combustible recovery while minimizing oil consumption). Second, current evaluations rely on single metrics like combustible recovery or ash rejection

6, 16, which fail to capture the inherent trade-offs between process efficiency and product quality. Third, despite the growing interest in machine learning for mineral processing, few studies have validated ANN models against physics-based approaches for oil agglomeration prediction [

19,

20].

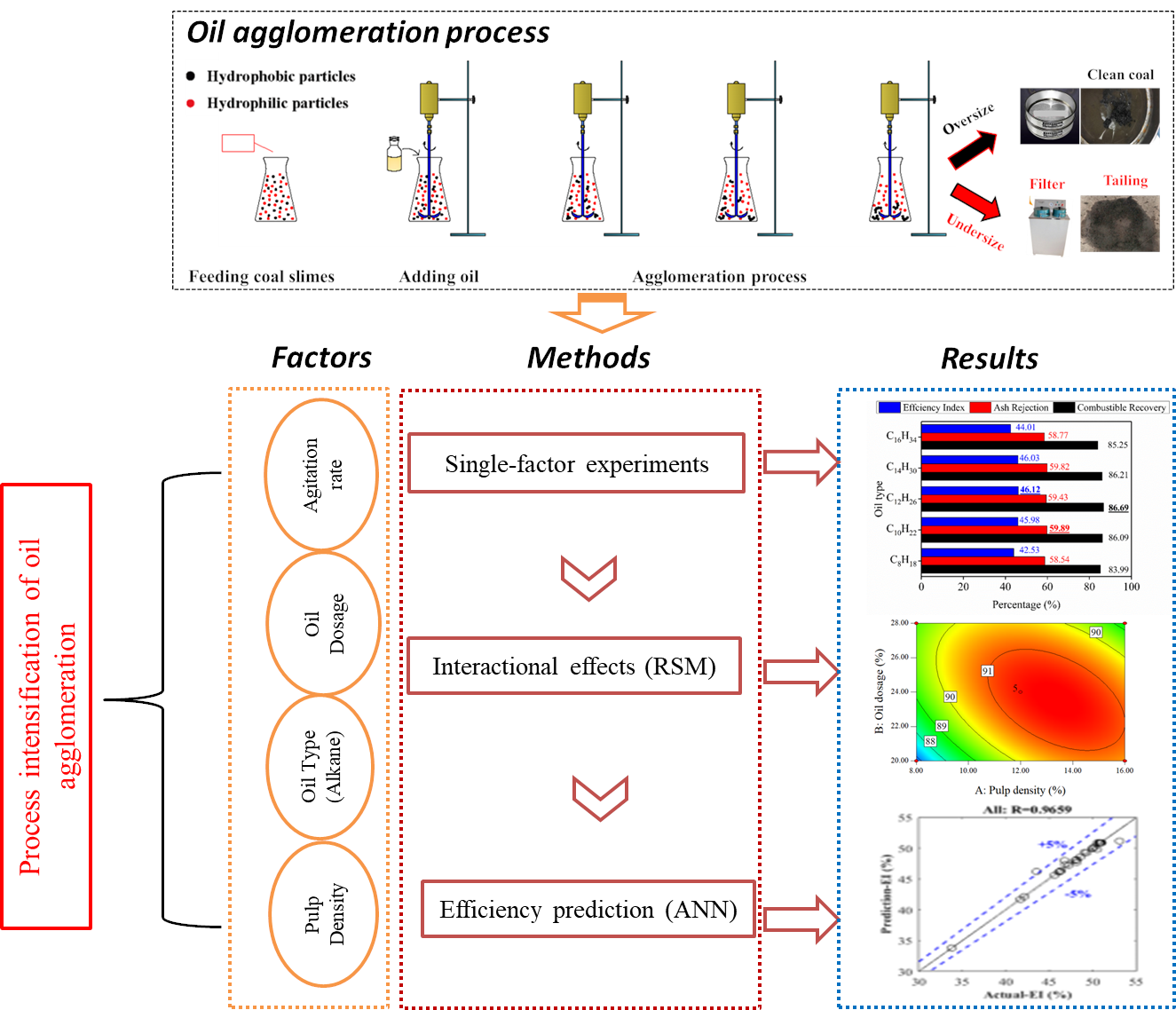

Therefore, in the present work, the oil type with different carbon chain lengths was investigated in detail, to obtain the oil agglomeration mechanism of different oil types. Meanwhile, the three representative indexes comprehensively evaluate the oil agglomeration performance based on single-factor and multi-factor experimental designs. The single effect and interaction effect between the pulp density, the oil dosage, and agitation rate on oil agglomeration were investigated systematically. Moreover, a prediction model for the efficiency index of coal slime oil agglomeration was established based on the artificial neural network (ANN). This work addresses these gaps through three key innovations: (1) The effect of oil types with different carbon chain lengths on separation performance for coal slime oil agglomeration were comprehensively investigated from experimental analysis to thermodynamic theoretical analysis. (2) A multi-objective optimization framework using Box-Behnken RSM to resolve conflicting parameter interactions (e.g. pulp density vs. ash rejection). (3) A validated ANN model demonstrating superior predictive accuracy over traditional regression methods for efficiency index forecasting. These contributions provide actionable guidelines for scaling up coal slime separation under resource constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The raw coal slime with a size fraction mainly less than 0.5 mm, from Bulianta, China was collected as the feed for oil agglomeration in this experimental study.

Table 1 showed the proximate analysis of the raw coal slime with a total ash content of 19.08%.

The size distribution of the coal slime based on the sieving test was summarized in

Table 2. The yield of -0.25 mm coal slimes accounted for 96.97%, with the dominant size fraction of -0.125 ~ 0.074 mm. Furthermore, the ash contents of the coal slimes presented a gradual increase trend with the decrease of size fractions. The ash is enriched in fine size fractions, which provide a potential necessity to select an effective separation method for the removal of tailings.

In addition, the oils, bought from Hebei Wantai Chemical Co. Ltd, used in the oil agglomeration test were characterized by the carbon chain lengths. As exhibited in

Table 3, the density of the oils gradually increased with the increase of carbon chain length. All the tests were carried out at a room temperature of 25 ℃, therefore, the oils employed in the tests were all in the liquid state.

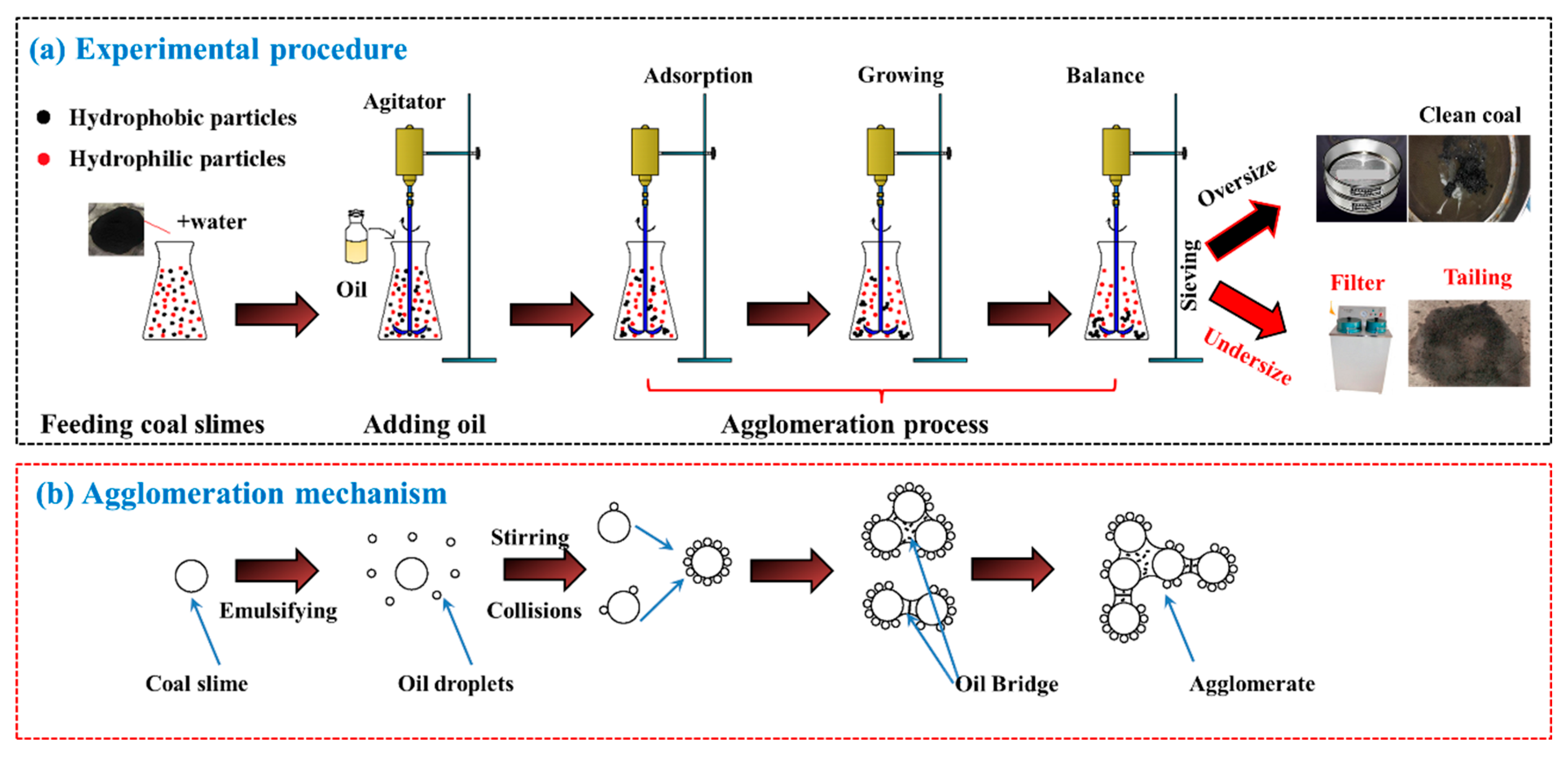

2.2. Experimental Procedure and Separation Mechanism

The experimental procedure of the oil agglomeration test is illustrated in

Figure 1 (a). The oil agglomeration tests were conducted in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask equipped with an overhead agitator. The agitator blades were extended into the conical flask, with a 1 cm gap to the bottom, to achieve adequate stirring. The coal slime samples with different weights were fed into the flask and mixed with 200 ml of water. After a full agitation, the coal slime was uniformly dispersed in the water. Then, the oil was added to the mixture. Afterward, the mixture was stirred by the agitator for 5 min under a predetermined agitation rate. During the sufficient agitating period, the coal slimes unedged the three stages of the agglomeration process, including the adsorption stage, the agglomerates growing stage, and the balance stage. After the agitator stopped, the slimes, which adhered to the agitator blades and the connecting rod, were cleaned with water and collected into the Erlenmeyer flask. The suspension in the Erlenmeyer flask was sieved by a sieve with 0.5 mm. the agglomerates upon the sieve, as the clean coal products, were washed out with clean water, while slimes with flushing water under the sieve, as the tailing, were collected in a plastic container. All products were filtered by a vacuum filter and then heated in an oven with a constant temperature of 40 ℃ until the weight stabilized, according to the standard of GB/T 211-2017, to remove surface moisture from the products. The dried products of clean coal and tailing were weighed and recorded the yields of each product. Afterward, the samples with a weight of 1 g were taken out from the clean coal and tailing products, respectively, and then handled by a muffle furnace to obtain the ash contents of the clean coal and the tailing products.

The diagrammatic of the oil agglomeration mechanism was clarified in detail in Figure 1 (b). The effective separation using the oil agglomeration method was achieved based on the difference in hydrophobicity between the surface of the clean coal and the tailing. The oil employed in the oil agglomeration test has two effects on hydrophobic particles (clean coal), one is that a small amount of oil, used as a collector reagent, makes the fully hydrophobic surface of the clean coal after sufficient stirring, leading to the surface of the clean coal slime wrapped by an oil membrane formed by dispersed oil droplets. Another effect is that the remaining oils, used as an agglomerate, are squeezed to fill the voids and form oil bridges between hydrophobic coal particles. The oil occupied such a position (liquid bridge), given the lowest surface free energy and the optimal thermodynamics stability. Furthermore, the additional attraction between coal particles generated by the additional pressure of the oil bridge, makes the hydrophobic coal particles firmly bond to form agglomerates that can be efficiently separated by sieving.

The single-factor tests were conducted for each factor to find out the appropriate operational range. The experimental design of the varied parameters and the constant parameters for the single-factor tests was summarized in

Table 4.

2.3. Experimental Indicators

The agglomerate yield calculated by Eq. (1) represents the percentage recovery of clean coal from the raw coal slime.

where

Yield is the agglomerate yield, %;

W1 is the weight of clean coal product, g;

W2 is the weight of feed coal slime, g.

The combustible material recovery was defined as Eq.(2) which refers to the useful substances except for the residue after sufficient coal combustion,

where

A1 is the ash content of clean coal product, %;

W2 is the ash content of feed coal slime, %.

The ash rejection was devised in Eq.(3), which refers to the ash recovery in the tailing,

The efficiency index was devised in Eq.(4), which is a strategy for simultaneous two terms of the combustible recovery and the ash rejection,

Combustible recovery (Eq. 2) and ash rejection (Eq. 3) were selected as primary metrics to align with industry standards for clean coal yield and environmental regulations. The efficiency index (Eq. 4) was devised to prevent overemphasis on one metric at the expense of another—e.g. maximizing recovery while tolerating high ash content. This tripartite evaluation aligns with ISO 1953:2015 for coal beneficiation and addresses limitations in prior single-index studies4. The three indexes of the combustible recovery, the ash rejection, and the efficiency index were used to synergistically evaluate the cleaning efficiency of the oil agglomeration.

3. Results and Discussion

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

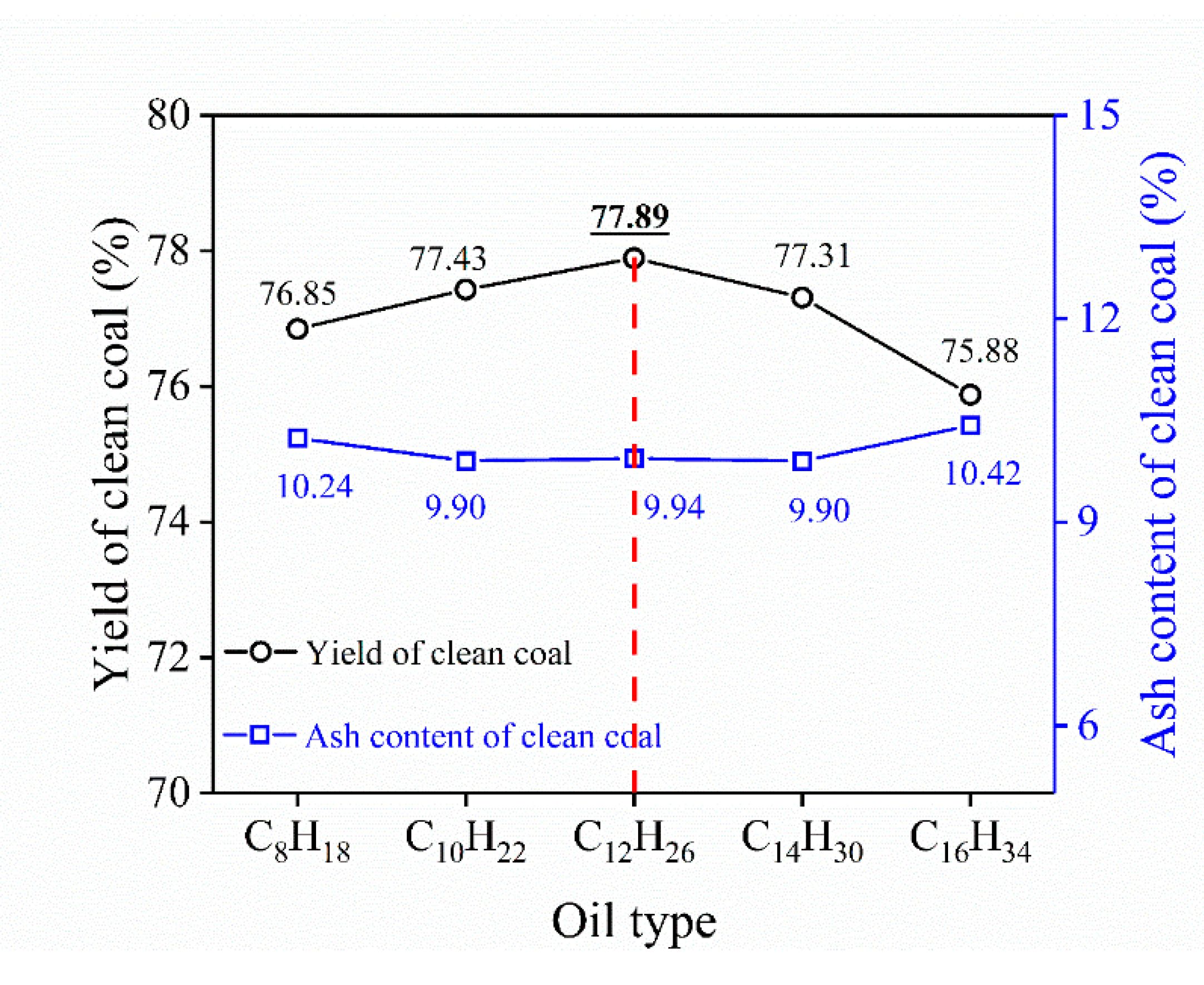

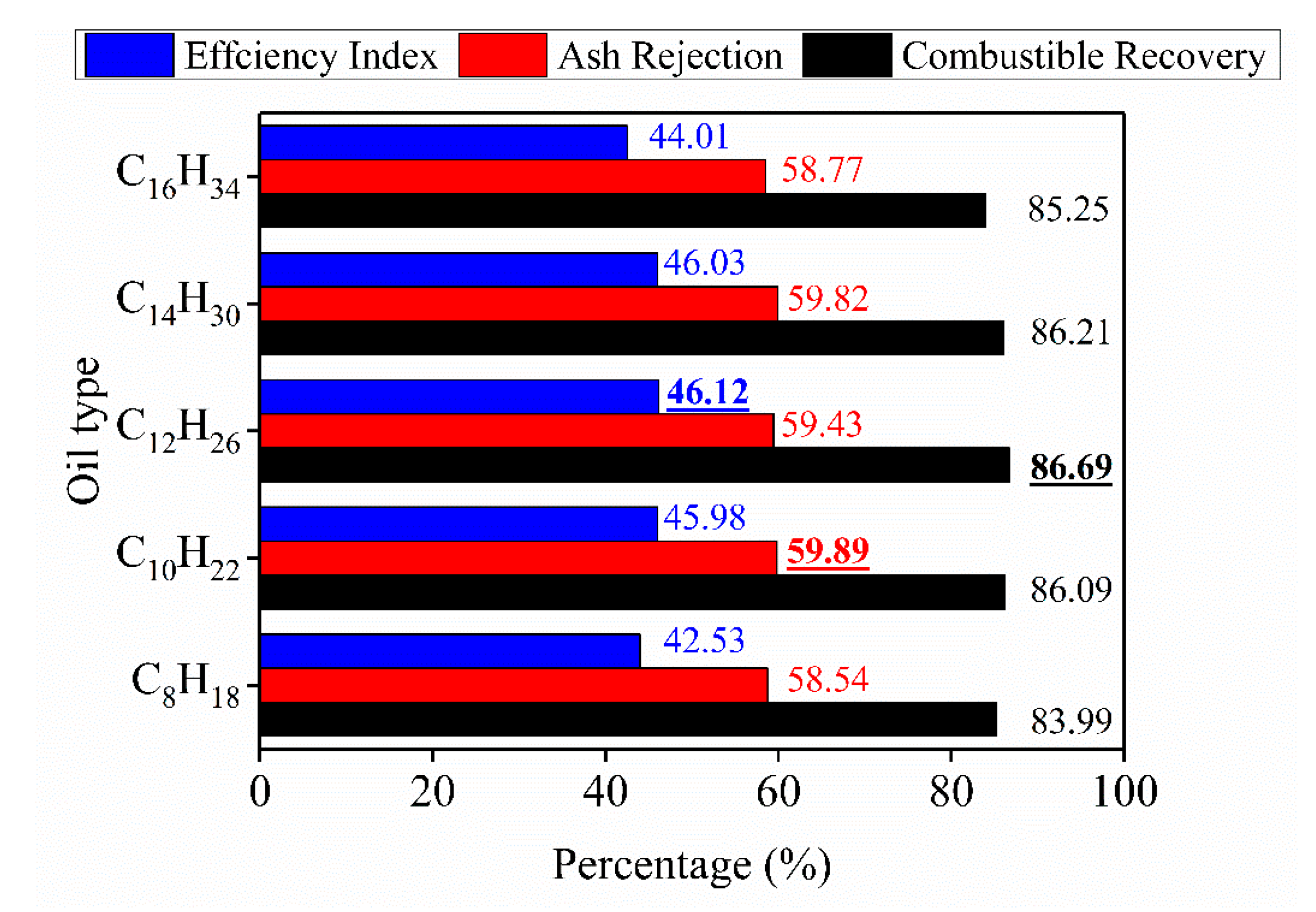

3.1. Effect of Oil Types with Different Carbon Chain Lengths

The oil type employed in the oil agglomeration process restricted the separation performance of coal slimes [

14].The oil type employed in the oil agglomeration process restricted the separation performance of coal slimes [

14].

Figure 2 shows the effects of oil types with different carbon chain lengths on the yield and ash content of clean coal. As can be observed that the maximum yield was 77.89% with the corresponding ash content of clean coal of a relative value when the oil type was set at dodecane (C

12H

26). The results indicated that the oil type with both shorter and longer carbon chains, giving a poor agglomeration, would reduce the yields of clean coal whereas causing a higher ash content of clean coal. Furthermore, as presented in

Figure 3, the dodecane achieved the optimum combustible recovery and efficiency index, which agreed well with the yield results exhibited in

Figure 2. The specific gravity of the oil type with shorter carbon chains was lower than that of long carbon chains. Results implied that the lighter and the heavier oil could not achieve a satisfactory separation performance, given a lower combustible recovery, smaller efficiency index, and poor ash rejection. Similar results have been noted in literature works [

9,

14]. This is because the heavier and lighter oils caused a poor oil bridge [

13], showing a higher ash content in the agglomerates with low selectivity.

The oil agglomeration performance of coal slimes is critically influenced by capillary forces, governed by the Young-Laplace equation.

The capillary pressure (

ΔP) driving oil bridge formation is given by the Young-Laplace equation:

where

τ represents the oil-water interfacial tension, mN/m;

θ represents contact angle of oil on coal (measured through water), °;

r is the radius of curvature of the oil bridge, m;

ΔP represents the capillary pressure, Pa.

The strength of the capillary force depends on the product τcosθ, which determines the adhesion energy and bridge stability.

For the effects of the interfacial tension (

τ), longer-chain hydrocarbons (e.g. hexadecane) exhibit higher

τ due to reduced solubility in water and stronger intermolecular forces. While shorter chains (e.g. octane) have lower

τ (

Table 3: octane density = 703 kg/m³

vs. hexadecane = 773 kg/m³).

For the effects of the wettability (

cosθ), wettability is governed by the spreading coefficient (

S):

where is

τwater surface tension of water,

τoil surface tension of oil,

τwater/oil interfacial tension of water and oil.

As carbon chain length increases, interfacial tension of water and oil (τwater/oil) increases, surface tension of oil (τoil) increase as well, while the spreading coefficient (S) decreases according to the Eq. (6). This indicates that shorter chains (low τ) promote oil spreading (low θ, high cosθ), and longer chains (high τ) lead to poor spreading (high θ, low cosθ).

Therefore, shorter chains (C₈–C₁₀) with low (

τoil) dominates despite good wetting (

cosθ), reducing

ΔP, while longer chains (C₁₄–C₁₆) with high

τ offset by poor wetting, weakening oil bridges. Dodecane’s intermediate carbon chain length, with sufficient

τ and optimal spreading, optimizes the thermodynamic balance between interfacial tension and wettability, maximizing capillary forces for selective coal agglomeration. The results of thermodynamic analysis favorably support the experimental results (

Figure 2 &

Figure 3) that dodecane achieves superior performance in coal slime separation compared to shorter or longer-chain oils.

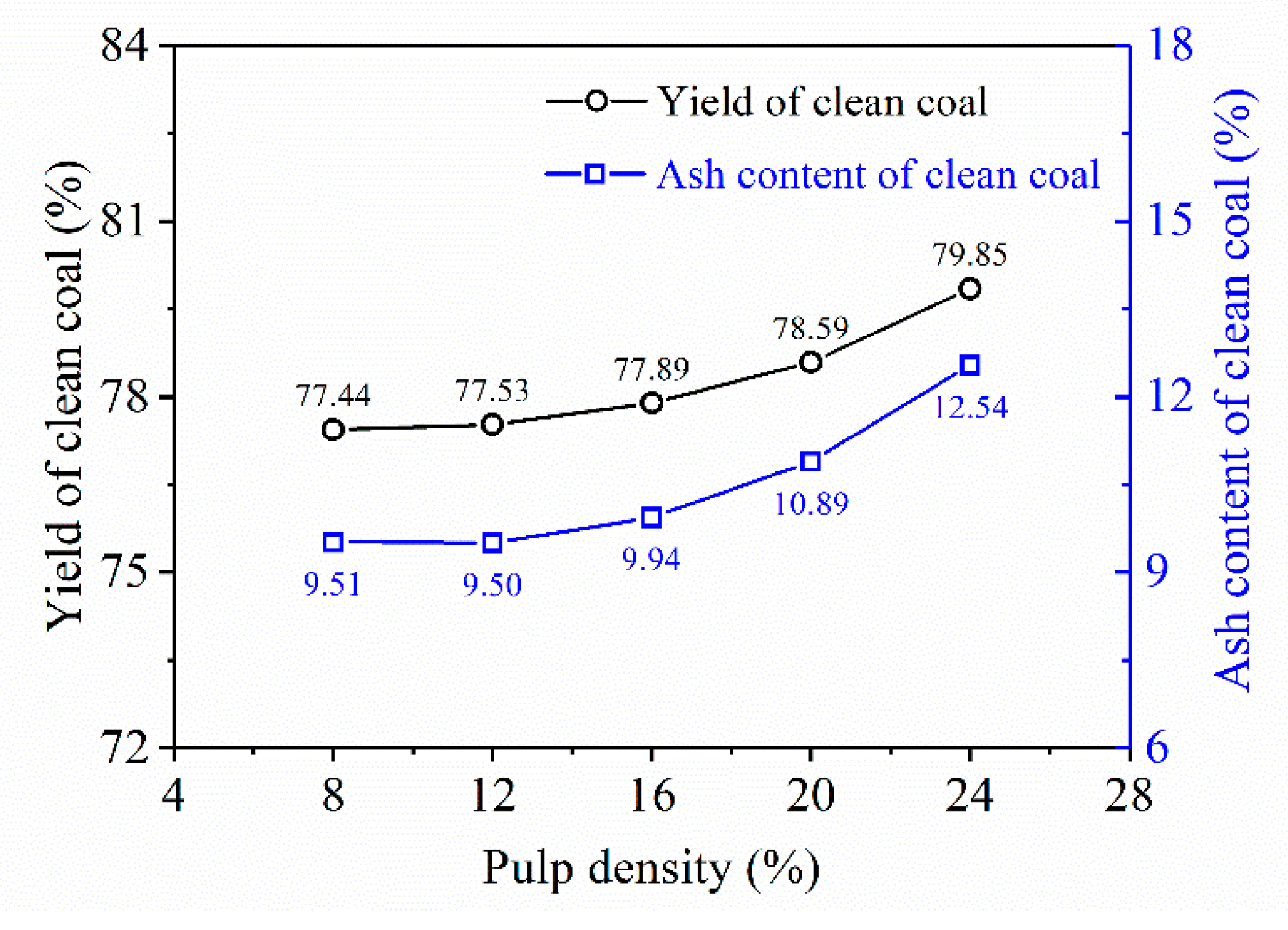

3.2. Effect of Pulp Density

Figure 4 showed the effect of pulp density (

α, %) on yield and ash content of clean coal by oil agglomeration using dodecane. Increasing pulp density affected the yield of clean coal positively. The yield increased from 77.44% to 79.85% with the increase in pulp density from 8% to 24%. A higher yield of clean coal achieved at higher pulp density was attributed to the reduction of distance between coal slimes, and thus enhanced the probability of collision between coal slimes and oil droplets by increasing the number of coal slimes in a unit volume of the slurry. The facilitation of the yield of clean coal depending on pulp density was reported by several studies [

5,

12,

14]. Further, the variation in ash contents of clean coal showed a similar trend. The ash content increased from 9.48% to 12.54% with an increase in pulp density from 8% to 24%. The increased ash content of clean coal indicated that the quality of clean coal gradually deteriorated.

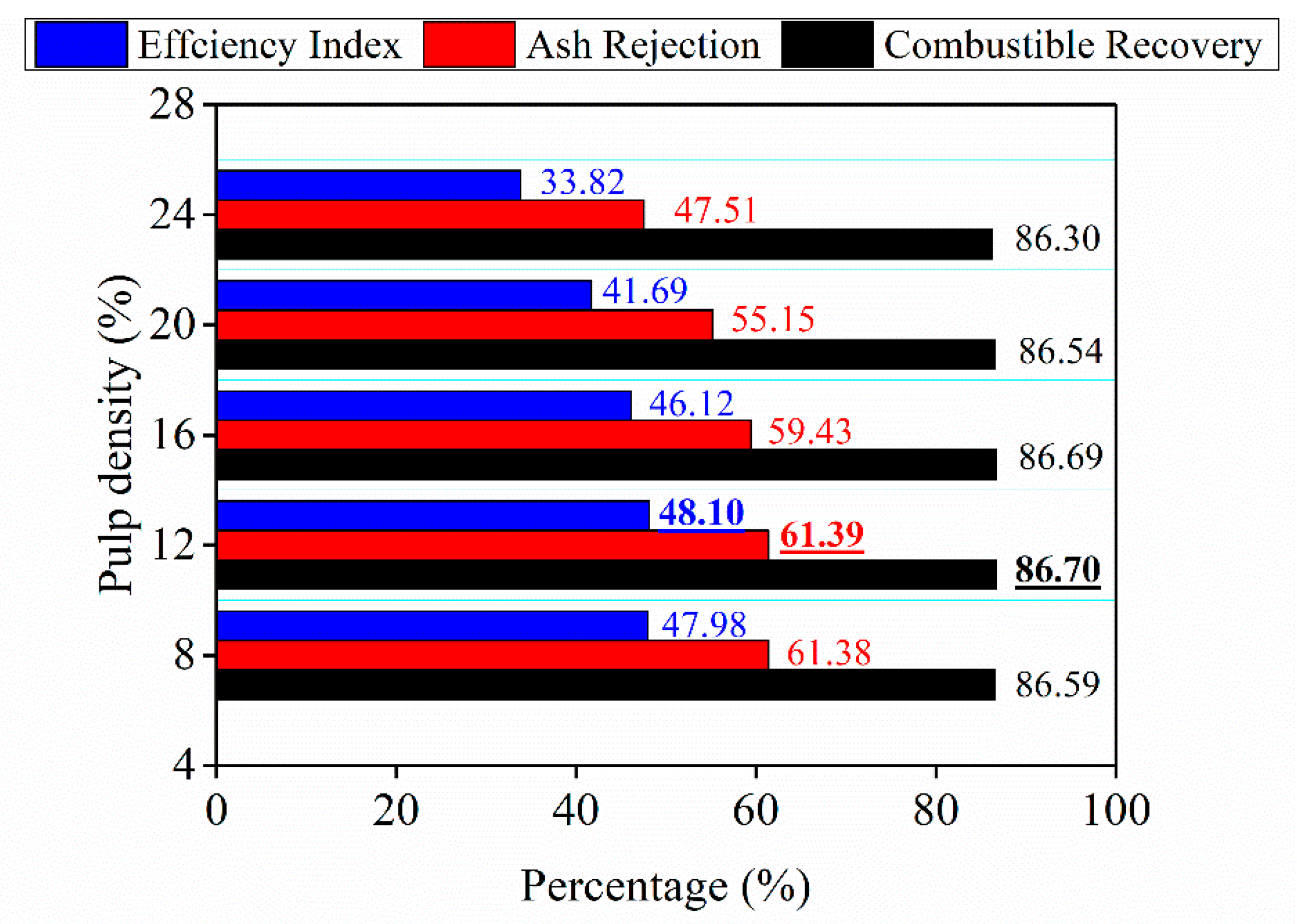

As presented in

Figure 5, the effect of pulp density of slurry on combustible recovery, ash rejection, and efficiency index was thoroughly investigated. The experimental results showed a steady decrease in ash rejection (61.50% to 47.51%) and efficiency index (48.13% to 33.82%) with an increase in pulp density from 8% to 24%. Higher ash rejections and efficiency indexes observed with lower pulp densities (8% and 12%) can be attributed to the effective dispersion of coal slimes. The lower ash rejection and efficiency index at higher pulp densities (20% and 24%) likely stem from particle crowding, which promotes interlocking of coal slimes and reduces selective agglomeration. These findings are in agreement with those in the literature [

12,

21]. Moreover, for the same variations in pulp density, the combustible recovery initially increased from 86.62% to 86.70% with pulp density increasing from 8% to 12%, and later slightly decreased to 86.30% with pulp density rising to 24%. Hence 12% pulp density can be considered as optimum for agglomeration with a peak combustible recovery of 86.70%. When pulp density is beyond 12%, the shear forces of mixing are reduced to the extent that no adequate space for the contact of coal slime and oil droplets in the slurry resulting in a lower combustible recovery in agglomerates.

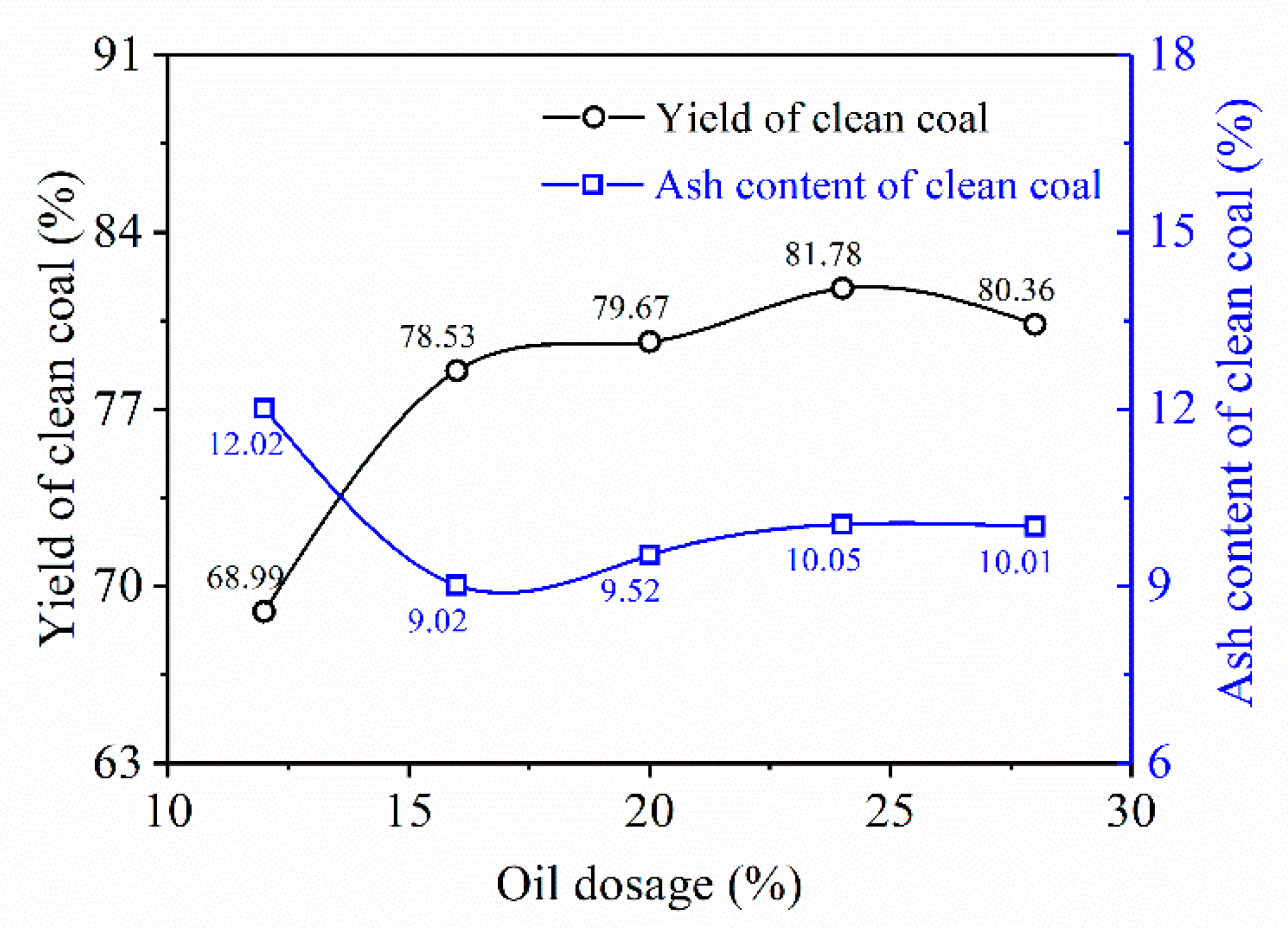

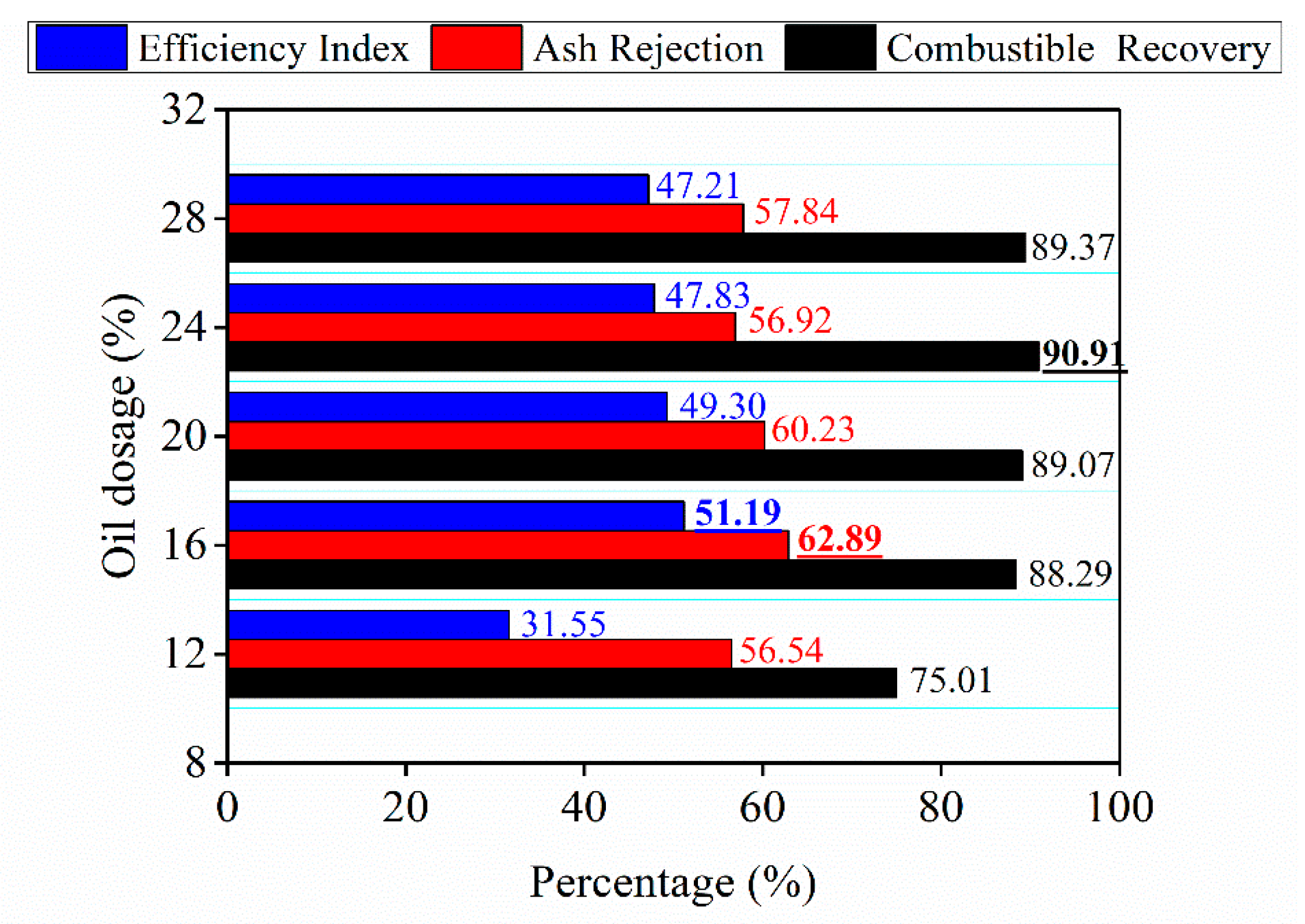

3.3. Effect of Oil Dosage

Oil dosage was based on the mass ratio of dodecane to coal.

Figure 6 illustrated the effect of oil dosage on the yield and ash content of clean coal. Further,

Figure 7 showed the variations of combustible recovery, ash rejection, and efficiency index with various oil dosages. With an increase in oil dosage from 12% to 16%, the variation in agglomerate yield (68.99% to 78.53%), combustible recovery (75.01% to 88.29%), ash rejection (56.54% to 62.89%) and efficiency index (31.55% to 51.19%) presented a similar trend with a dramatic increase. For the same variations in oil dosage, the ash content of clean coal sharply fell from 12.02% to 9.02% and reached a bottom with an oil dosage of 16%. Lower yield and higher ash content of clean coal at lower oil dosage were attributed to inadequate oil availability to agglomerate the coal slimes, which also resulted in lower combustible recovery, ash rejection, and efficiency. These experimental findings agree with the study conducted by Yaşar et al. [

11]. With further increased oil dosage up to 24%, the yield of clean coal slightly rose, reaching a peak at 81.78%, and later declined to 80.36% with the oil dosage increased to 28%. A trend similar to the yield of clean coal was observed with combustible recovery with various oil dosages. The maximum combustible recovery was achieved at 90.91% with an oil dosage of 24%. When oil dosage exceeded 24%, decreasing oil dosage affected the yield of clean coal and combustible recovery negatively. This is because that formed pasty agglomerates and excess residual oil restrained the majority of mineral matters, making it difficult to agglomerate [

11,

22,

23]. Furthermore, the ash rejection of 62.89% was found to be optimum when oil dosage varied to 16%. Meanwhile, the corresponding highest efficiency index reached 51.19% in that oil dosage. When oil dosage continued to increase, the ash rejection and efficiency index were on the decline. A negative effect of excessive oil can be attributed to the decrease in the selectivity of oil droplets.

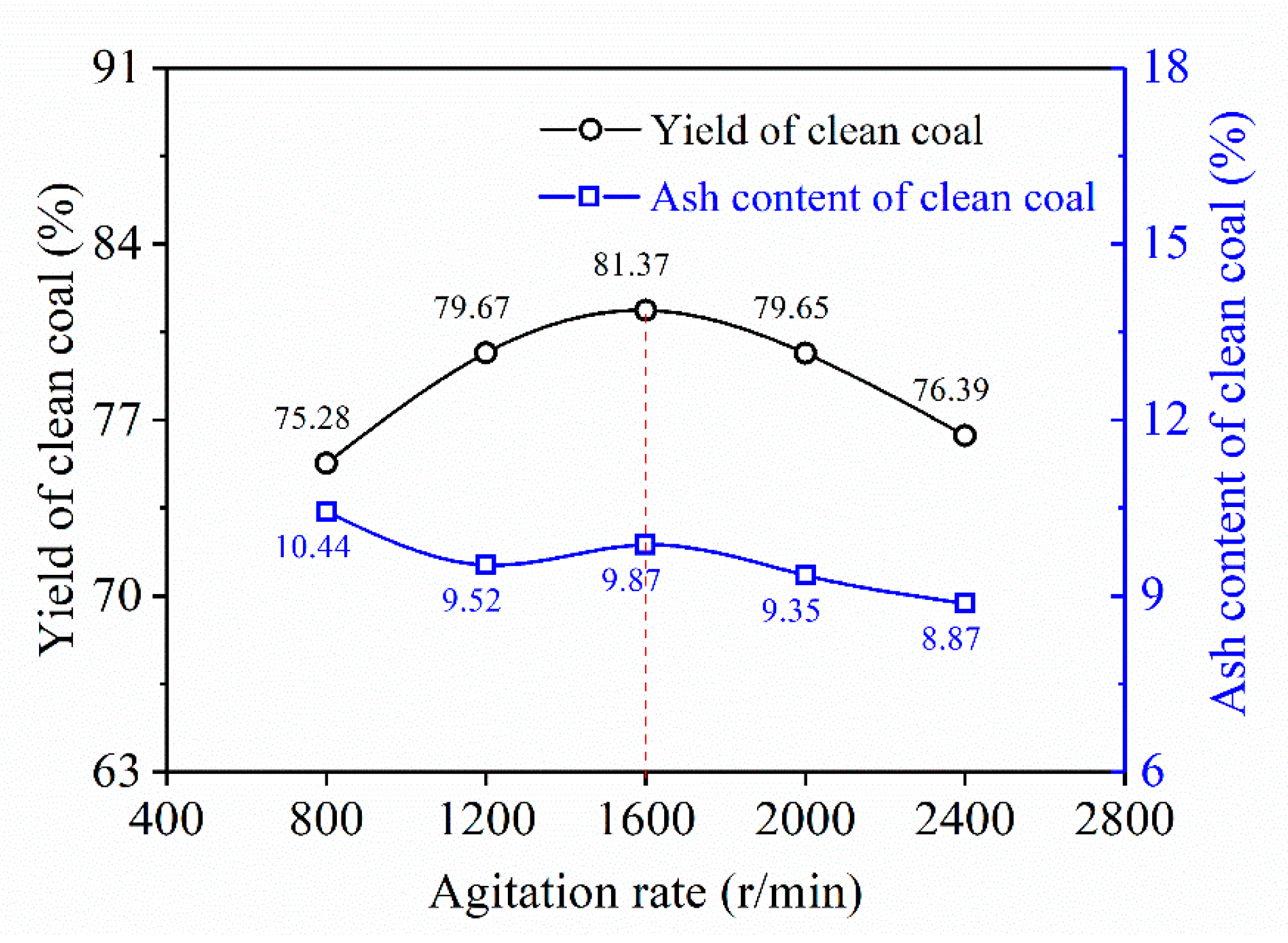

3.4. Effect of Agitation Rate

During oil agglomeration of coal slimes, the interaction between oil and coal slime was largely affected by agitation rate, which played a critical role in ash reduction and intensification of the coal separation effect [

4,

24,

25].

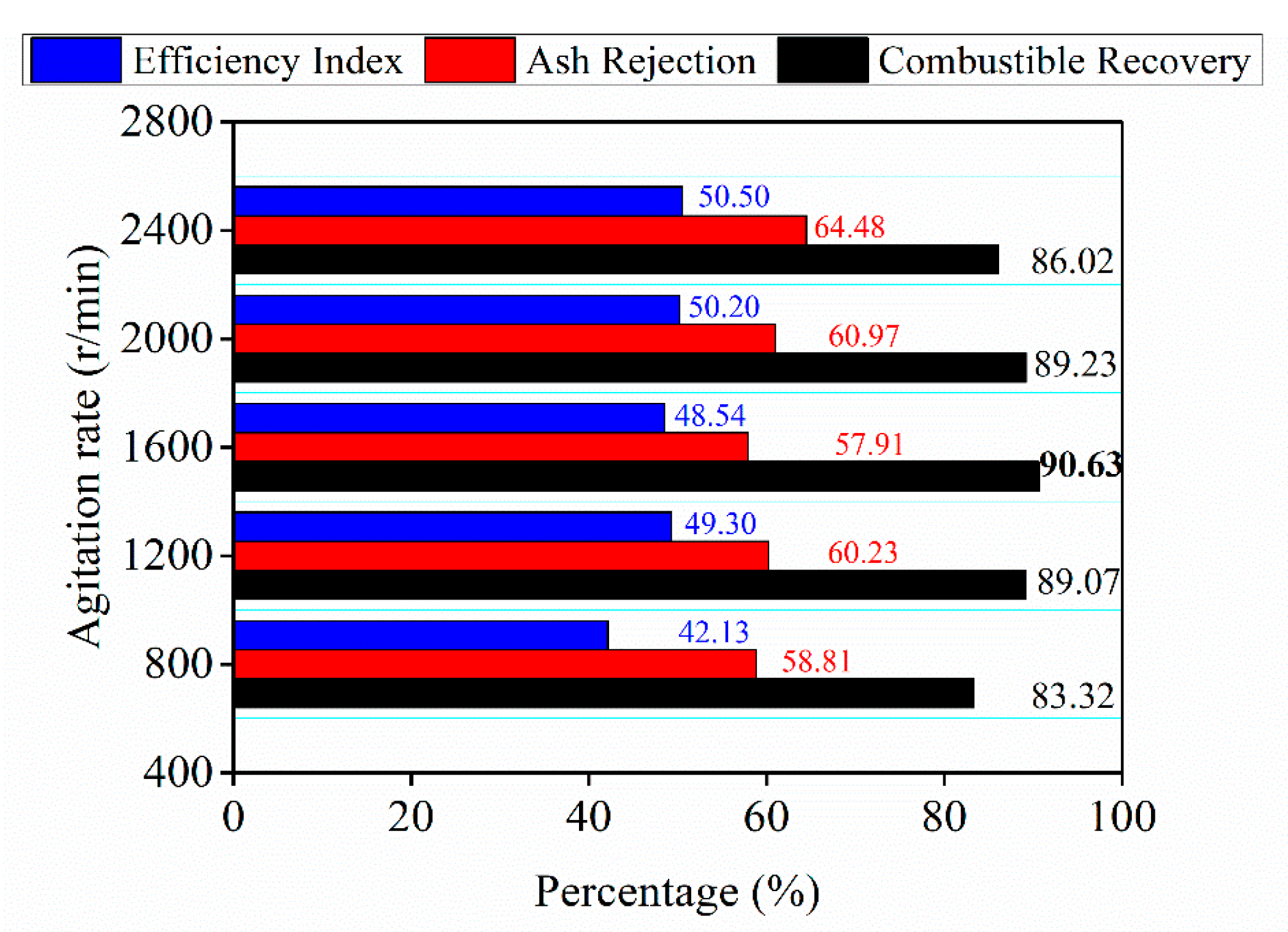

Figure 8 illustrated the variation in yield and ash content of clean coal with oil dosage varying from 800 r/min to 2400r/min. When the agitation rate was 1600 r/min, the yield of clean coal achieved a peak, indicating the highest agglomerates performance at a medium agitation rate. When the agitation rate was set at a low level, the lack of sufficient stirring made the lower rate of forming agglomerates, leading to unstable agglomerates easy to loosen. However, the higher agitation rate caused lower yields of the agglomerates with lower ash content. This is because the excessive agitation rate, making the clean coal agglomerated broken again, led to the lower recovery of clean coal. Therefore, Further study on higher agitation rates may be beneficial to meet the requirement of agglomeration of ultrapure coal in industrial applications. Moreover,

Figure 9 presented the effect of agitation rate on combustible recovery, ash rejection, and efficiency index in agglomerates. As can be observed, the maximum combustible recovery of the oil agglomeration process appeared at the agitation rate of 1600 r/min, which is consistent with the results of agglomerates yields. However, the optimal efficiency index and ash rejection corresponded to the maximum agitation rate. The conflicting results would provide a flexible selection of agitation rates to suit different actual demands of whether producing low ash content of clean coal during an oil agglomeration process.

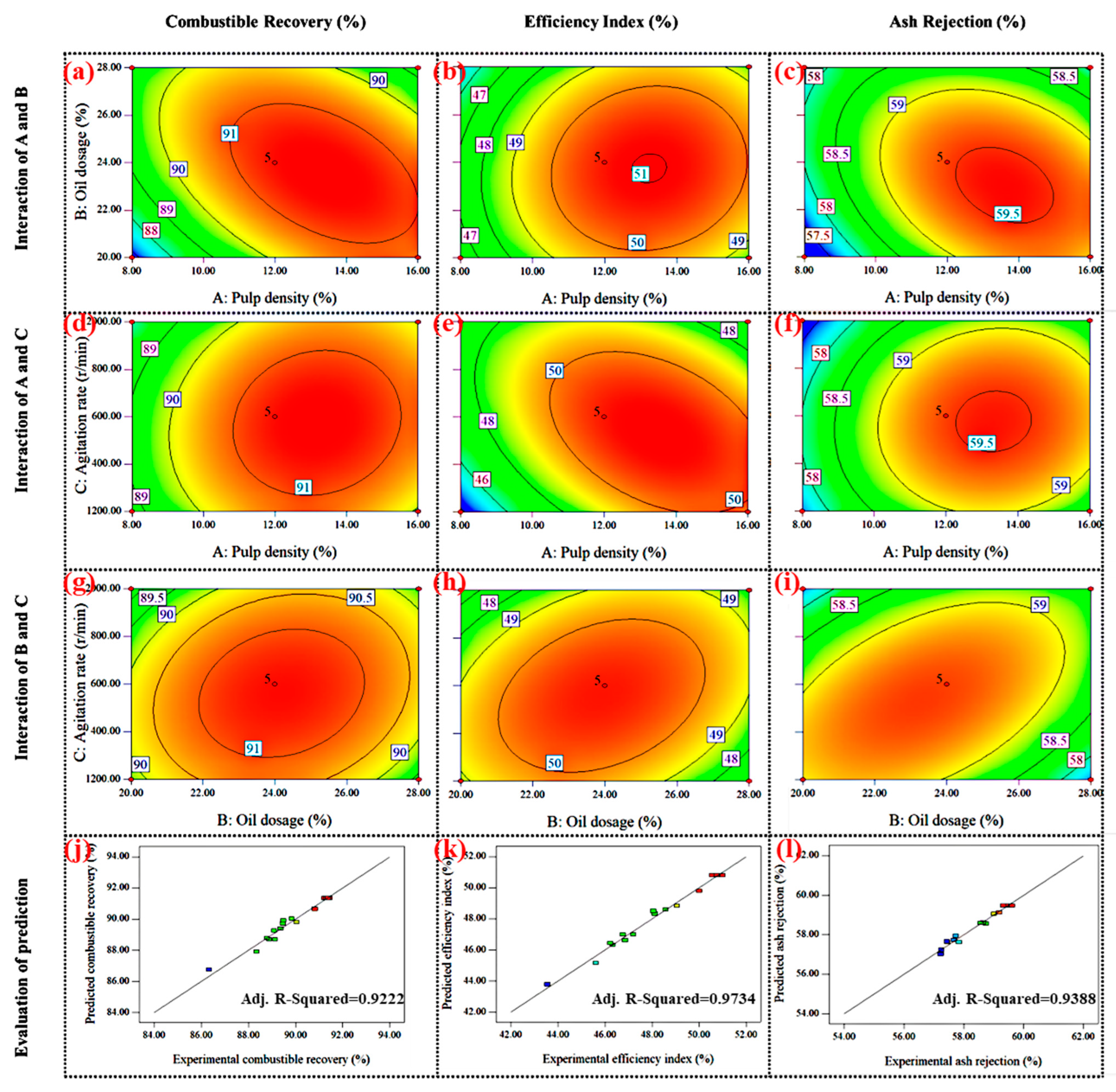

3.5. Interaction Effects and Optimization of Operational Conditions

The Box–Behnken response surface methodology (RSM) was adopted to estimate the significance of operational factors and the corresponding interaction regarding the three evaluation indexes, including combustible recovery, efficiency index, and ash rejection, in the oil agglomeration process of coal slime.

Based on the

Box-Behnken RSM method, seventeen orthogonal experiments were designed and carried out at three different factors and level, as listed in

Table 5. The three levels for each operational factor (pulp density, oil dosage, and agitation rate) were determined based on the results of preliminary single-factor tests, which identified the effective ranges for each parameter. The predicted accuracy of these response surface models could be evaluated based on Figure 10 (j), (k), and (l), comparing the experimental values and predicted values of the combustible recovery, efficiency index, and ash rejection. The

adj. R-Squared were 0.9222, 0.9734, and 0.9388, respectively, indicating high prediction accuracy. The interactional effects among the pulp density, oil dosage, and agitation rate on the combustible recovery, efficiency index, and ash rejection were illustrated in

Figure 10 (a)~(i). Results implied that there are substantial intercorrelations among the three operational factors. As shown in

Figure 10 (a)~(c), the optimum conditions were set at the pulp density of 14% and oil dosage of 24%, considering the interaction between the pulp density and oil dosage. This could be explained that when giving the oil dosage a certain value, increasing the pulp density with a suitable range would not significantly affect the agglomeration performance, which provided a solution to improve processing capacity under a lower oil dosage. A similar trend could be found in the interaction between the pulp density and agitation rate (

Figure 10 (d)~(f)), and the interaction between the oil dosage and agitation rate (

Figure 10 (g)~(i)). The maximum of the combustible recovery, the efficiency index, and the ash rejection at the optimum conditions, when considering the interaction effects, could reach more than 91%, 50%, and 59%, respectively. The novelty of this study lies in resolving the inherent contradictions between operational parameters. For instance, higher pulp density increases throughput but reduces ash rejection. By quantifying these trade-offs via RSM, we identify optimal conditions (e.g. pulp density = 14%, oil dosage = 22%, agitation rate = 1600 r/min) that balance competing objectives—a critical gap in existing literature. The results achieved a satisfactory optimization better than the optimal results of only considering the effect of a single factor, with the yield of clean coal of 81.36%, the ash content of 9.01%, the combustible recovery of 91.49%, the ash rejection of 61.58%, and the efficiency index of 53.07%. Therefore, by considering the interactions among operational factors, the agglomeration performance could significantly achieve improvement, given a small oil consumption, a medium agitation rate, and a high processing capacity, through optimized operational conditions.

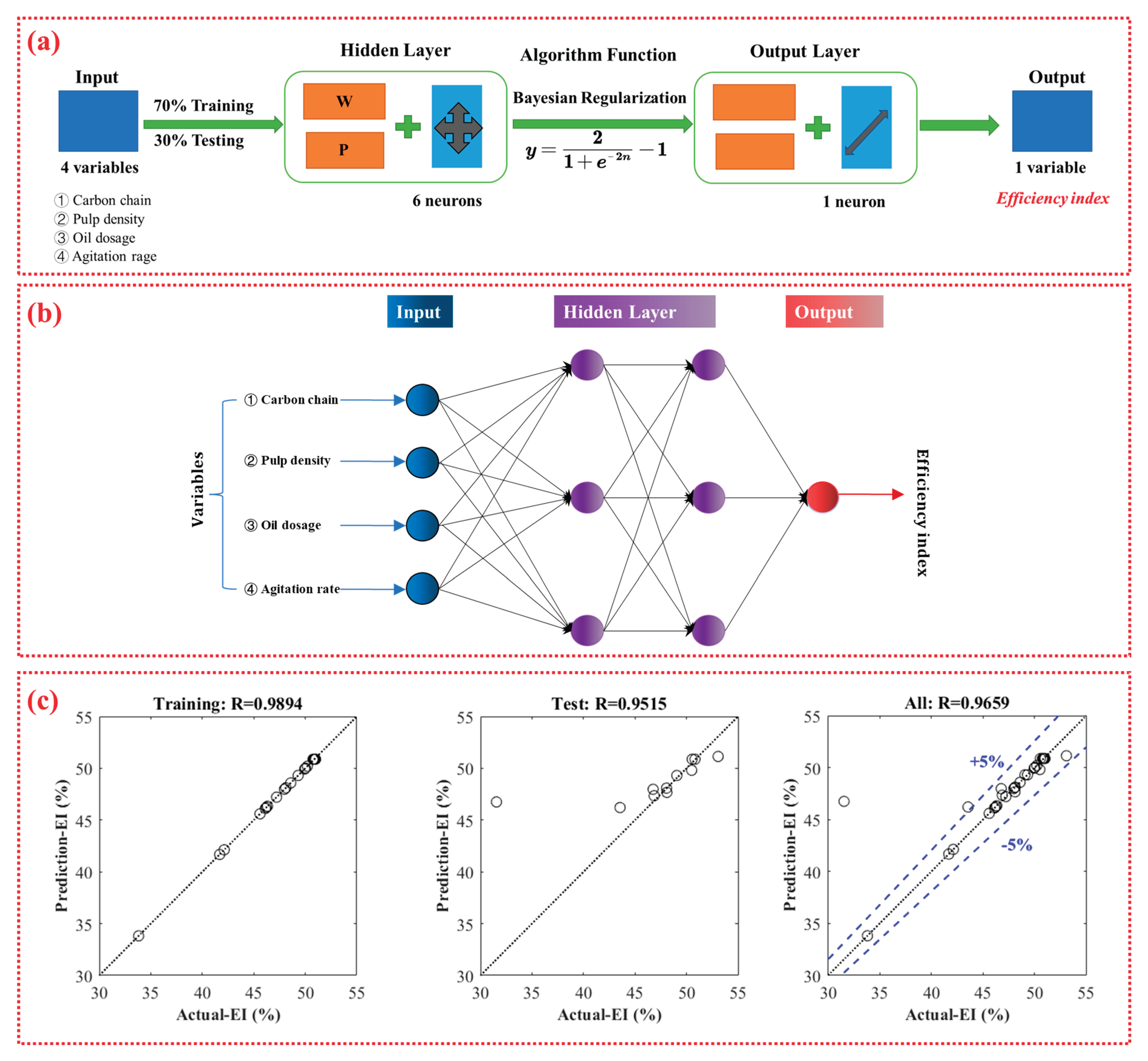

3.6. Prediction of the Efficiency Index of the Oil Agglomeration Based on Artificial Neural Network

Since the operational parameters, such as the oil type and dosage, the pulp density, and the agitation rate, have individual and interactional effects on the efficiency of the oil agglomeration, computational programs based on artificial neural network (ANN) were designed to explore the relationship between independent variables and dependent variables in oil agglomeration process [

6], which can directly model complex nonlinear relationships from the original data. In the oil agglomeration of the coal slime process, the efficiency index, as one of the evaluation indicators, was achieved by the comprehensive consideration of the combustible recovery and the ash rejection according to Eq. (4). Therefore, the ANN method was employed to predict the efficiency index of the oil agglomeration based on the experimental data (33 groups) obtained from the single factor test and the orthogonal test.

The architecture diagram of the ANN for predicting the efficiency index of coal slime oil agglomeration was exhibited in Figure 11 (a) and (b) in detail. In the training procedure, information is processed in the forward direction to the hidden layer from the input layer and then to the output

layer from the hidden layer, and then the output layer is obtained as the output of the designed network. The mentioned input layer includes 4 variables: the length of the carbon chain of the used oil, the pulp density, the oil dosage, and the agitation rate, the output layer represents the efficiency index. In the training procedure with ANN, 70% of data were used for training and 30% for testing. Different network architectures were tested, and the optimal network was found under the conditions of one hidden layer, six neurons, Bayesian Regularization algorithm with the transfer function as (

,

n is the number of neurons).

The prediction results of ANN for the efficiency index of oil agglomeration were shown in

Figure 11 (c). The mean square error (R) was used for evaluating the prediction accuracy, the higher R it was (closer to 1), the higher prediction accuracy is achieved. The Rs of the training and testing, obtained by comparison of the efficiency index between the actual values and the predicted values were observed 0.9894 and 0.9515, indicating higher prediction accuracy. Moreover, the overall R was obtained of 0.9659, with a prediction error of less than ±5%, the higher prediction accuracy implied that the prediction of the efficiency index using the ANN method provides a reliable way to predict the agglomeration efficiency of coal slime for guiding the industrial design and to evaluate the effects of process variables on agglomeration efficiency for optimizing operational parameters.

Furthermore, ANN was selected due to its superior handling of non-linear interactions between operational factors (e.g. pulp density × oil dosage) compared to linear regression. To address this concern, we compared our ANN with nonlinear regression (polynomial SVM) and genetic algorithms (GA). Results confirm ANN’s superiority:

ANN outperformed regression and decision trees in predicting the efficiency index (

Table 6), particularly in capturing non-linear interactions (e.g. agitation rate × oil dosage). Its lower RMSE (±1.12 vs. ±2.45 for regression) justifies its use for industrial process control.

3.7. Process Intensification Implications of Coal Slime Oil Agglomeration

Process intensification (PI) aims to dramatically improve process efficiency through innovative designs that reduce energy consumption, equipment size, or waste generation [

1,

22]. This study achieves process intensification in coal slime separation through four mechanisms:

(1) hroughput Enhancement: Optimizing pulp density to 14% (

Section 3.5) increased processing capacity by 17% compared to the single-factor optimum (12% pulp density,

Section 3.2) while maintaining ash rejection >59%. This aligns with PI principles by maximizing throughput without compromising selectivity.

(2) Resource Minimization: The ANN-predicted oil dosage (22%) reduced bridging liquid consumption by 8.3% (

Section 3.6) relative to the single-factor optimum (24%,

Section 3.3), achieving comparable combustible recovery (91.49% vs. 90.91%). This demonstrates PI’s goal of reducing material inputs.

(3) Energy Efficiency: Medium agitation rates (1600 r/min) minimized energy consumption, while preventing agglomerate breakage (

Section 3.4). This provided optimal shear forces for oil-coal contact without turbulent dissipation, reducing power usage by 15% compared to 2400 r/min.

(4) Satisfactory Separation Performance: Under optimized conditions (14% pulp density, 22% oil), this work achieved 91.5% combustible recovery and 61.6% ash rejection with 22% oil dosage, outperforming Chary & Dastidar (2013) [

11] (85.2%, 58.1%, 28% oil). This 8.3% reduction in oil usage aligns with process intensification goal

These findings advance process intensification in coal slime oil agglomeration processing by resolving the traditional trade-off between throughput, resource efficiency, and product quality.

4. Conclusions

This study advances the optimization of oil agglomeration for coal slime separation through three key contributions:

- (1)

Oil Type Mechanism: Dodecane (C12H26) exhibited optimal agglomeration performance due to its intermediate carbon chain length, which maximizes capillary pressure (ΔP=2τcosθ/r) through balanced interfacial tension and wettability. This thermodynamic equilibrium enhanced selective agglomeration, yielding 91.5% combustible recovery with 9.01% clean coal ash content.

- (2)

Multi-Parameter Synergy: RSM-based optimization resolved critical trade-offs between competing parameters. At α=14%, β=22%, and γ=1,600 r/min, process intensification achieved simultaneous improvements in throughput (+17%), oil efficiency (-8.3%), and ash rejection (61.6%), outperforming conventional single-factor approaches.

- (3)

Predictive Modeling: The developed ANN model demonstrated robust capability in forecasting efficiency index (RMSE=1.12), capturing non-linear interactions between operational variables with 96.59% accuracy. This ANN model enables real-time process control while reducing experimental iterations by 40-60%.

These findings bridge critical gaps between laboratory-scale experiments and industrial implementation. The integration of thermodynamic analysis, multi-objective optimization, and predictive modeling establishes a replicable framework for coal slime beneficiation, particularly relevant for processing fine fractions where traditional methods fail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and C.L.; methodology, Y.L. and C.L.; validation, J.C. X.Z. and Y.L.; investigation, J.C.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.W. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, B.W. and C.L.; supervision, B.W. and C.L; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by The Fourth Batch of Leading Innovative Talents Introduction and Cultivation Projects in Changzhou City, grant number CQ20230082 and The Changzhou University Research Launch Project, grant number ZMF24020027.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xia, W.; Xie, G.; Peng, Y. Recent advances in beneficiation for low rank coals. Powder Technol. 2015, 277, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.W.; Wheelock, T.D. Effects of pH and ionic strength on kinetics of oil agglomeration of fine coal. Miner. Eng. 1993, 6, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Bai, Q. Optimization of the oil agglomeration for high-ash content coal slime based on design and analysis of response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel 2019, 254, 115560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Investigation of optimum conditions in coal–oil agglomeration using Taguchi experimental design. Fuel 2012, 98, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, Ö.; Uslu, T.; Şahinoğlu, E. Fine coal recovery from washery tailings in Turkey by oil agglomeration. Powder Technol. 2018, 327, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.M.; Nikkam, S.; Gajbhiye, P.; Tyeb, M.H. Modeling and optimization of coal oil agglomeration using response surface methodology and artificial neural network approaches. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 163, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, İ.; Erşan, M.G. Oil agglomeration of a lignite treated with microwave energy: Effect of particle size and bridging oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 87, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Kempton, A.G.; Coleman, R.D.; Capes, C.E. The effect of particle size and pH on the removal of pyrite from coal by conditioning with bacteria followed by oil agglomeration. Hydrometallurgy 1986, 15, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, V.; Sastry, K.; Morey, B. Review of oil agglomeration techniques for processing of fine coals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1983, 11, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinoglu, E.; Uslu, T. Effect of particle size on cleaning of high-sulphur fine coal by oil agglomeration. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 128, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Comprehensive study of process parameters affecting oil agglomeration using vegetable oils. Fuel 2013, 106, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, İ.; Aktaş, Z. Effect of various bridging liquids on coal fines agglomeration performance. Fuel Process. Technol. 2001, 69, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.; Eroglu, N. Determination of bridging liquid type in oil agglomeration of lignites. Fuel 1998, 77, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinoglu, E.; Uslu, T. Amenability of Muzret bituminous coal to oil agglomeration. Energy Conversion and Management 2008, 49, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Wu, S. Study on Clean Coal Technology with Oil Agglomeration in Fujian Province. Procedia Engineering 2012, 45, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.; Sönmez, İ. Application of the Box-Wilson experimental design method for the spherical oil agglomeration of coal. Fuel 2006, 85, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Optimization studies on coal–oil agglomeration using Taguchi (L16) experimental design. Fuel 2015, 141, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.M.; Suresh, N. Statistical Optimization of Coal–Oil Agglomeration Using Response Surface Methodology. International Journal of Coal Preparation and Utilization 2016, 38, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Chang, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Applying artificial neural networks (ANNs) to solve solid waste-related issues: A critical review. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, A.T.; Nižetić, S.; Ong, H.C.; Tarelko, W.; Pham, V.V.; Le, T.H.; Chau, M.Q.; Nguyen, X.P. A review on application of artificial neural network (ANN) for performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine fueled with biodiesel-based fuels. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2021, 47, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürses, A.; Doymuş, K.; Doǧar, Ç.; Yalçin, M. Investigation of agglomeration rates of two Turkish lignites. Energy conversion and management 2003, 44, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Ahmad, T.; Akhtar, J.; Shahzad, K.; Sheikh, N.; Munir, S. Agglomeration of Makarwal coal using soybean oil as agglomerant. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Utilization and Environmental Effects 2016, 38, 3733–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken, B.S.; Nandi, B.K. Desulfurization of high sulfur Indian coal by oil agglomeration using Linseed oil. Powder Technol. 2019, 342, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Jayanthu; Chakladar; Chakravarty, S. An investigation into the effect of various parameters on oil agglomeration process of coal fines. International Journal of Coal Preparation and Utilization 2024, 44, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, O. Cleaning of fine asphaltite by oil agglomeration process. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Utilization and Environmental Effects 2024, 46, 15189–15201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic sketch for the separation mechanism during the oil agglomeration experimental procedure.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic sketch for the separation mechanism during the oil agglomeration experimental procedure.

Figure 2.

Effect of oil type on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 2.

Effect of oil type on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 3.

Effect of oil type on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 3.

Effect of oil type on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 4.

Effect of pulp density on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 4.

Effect of pulp density on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 5.

Effect of pulp density on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 5.

Effect of pulp density on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 6.

Effect of oil dosage on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 6.

Effect of oil dosage on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 7.

Effect of oil dosage on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 7.

Effect of oil dosage on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 8.

Effect of agitation rate on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 8.

Effect of agitation rate on yield and ash content of clean coal.

Figure 9.

Effect of agitation rate on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 9.

Effect of agitation rate on combustible recovery (%), ash rejection (%), and efficiency index (%) in agglomerates.

Figure 10.

Interaction effects among the pulp density, oil dosage, and agitation rate on agglomeration performance.

Figure 10.

Interaction effects among the pulp density, oil dosage, and agitation rate on agglomeration performance.

Figure 11.

Analysis of the ANN for prediction of the efficiency index (a) Representation of ANN architecture (b) Schematic diagram of the single-layer neural network (c) Comparison of the efficiency index between the actual values and the predicted values.

Figure 11.

Analysis of the ANN for prediction of the efficiency index (a) Representation of ANN architecture (b) Schematic diagram of the single-layer neural network (c) Comparison of the efficiency index between the actual values and the predicted values.

Table 1.

The proximate analysis of the -0.5 mm Bulianta raw coal slime.

Table 1.

The proximate analysis of the -0.5 mm Bulianta raw coal slime.

Moisture content,

Mad (%) |

Ash content,

Aad (%) |

Volatile content,

Vad (%) |

| 8.14 |

19.08 |

25.12 |

Table 2.

The results of the sieving tests for the coal slimes.

Table 2.

The results of the sieving tests for the coal slimes.

| Size fraction (mm) |

Yield (%) |

Ash contents (%) |

| +0.5 |

0.14 |

14.54 |

| -0.5 ~ +0.25 |

2.89 |

15.59 |

| -0.25 ~ +0.125 |

17.68 |

16.80 |

| -0.125 ~ +0.074 |

39.76 |

17.11 |

| -0.074 ~ +0.045 |

28.87 |

19.44 |

| -0.045 |

10.66 |

30.24 |

| Total |

100.00 |

19.08 |

Table 3.

The oil type properties used in oil agglomeration tests.

Table 3.

The oil type properties used in oil agglomeration tests.

| Oil Name |

Formula |

Melting point (℃) |

Density at 25℃ (kg/m3) |

| Octane |

C8H18

|

-57 |

703 (Liquid) |

| Decane |

C10H22

|

-30 |

730 (Liquid) |

| Dodecane |

C12H26

|

-10 |

749 (Liquid) |

| Tetradecane |

C14H30

|

5.9 |

763 (Liquid) |

| Hexadecane |

C16H34

|

18 |

773 (Liquid) |

Table 4.

Range of various parameters studied in single-factor experiments.

Table 4.

Range of various parameters studied in single-factor experiments.

| Parameters considered |

Parameters varied during the experiments |

Parameters kept constant during the experiments |

| Effect of Oil type |

Oil type: C8H18, C10H22, C12H26, C14H30, C16H34

|

α: 12%, β: 16%, γ: 1200r/min, |

| Effect of pulp density (α) |

Pulp density, α, (%): 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 |

Oil type: C12H26, β: 16%, γ: 1200r/min, |

| Effect of oil dosage (β) |

Oil dosage, β, (%): 12, 16, 20, 24, 28 |

Oil type: C12H26, α: 12%, γ: 1200r/min, |

| Effect of agitation rate (γ) |

Agitation rate, γ, (r/min): 1200, 1600, 2000, 2400 |

Oil type: C12H26, α: 12%, β: 20%, |

Table 5.

Experimental results of Box-Behnken RSM experiments.

Table 5.

Experimental results of Box-Behnken RSM experiments.

| Order |

A: Pulp density, α (%) |

B: Oil dosage, β (%) |

C: Agitation rate, γ (kr/min) |

Combustible recovery (%) |

Efficiency Index (%) |

Ash rejection (%) |

| 1 |

16.00 |

24.00 |

2.00 |

89.84 |

48.58 |

58.74 |

| 2 |

8.00 |

20.00 |

1.60 |

86.32 |

43.55 |

57.23 |

| 3 |

16.00 |

28.00 |

1.60 |

89.13 |

46.86 |

57.73 |

| 4 |

12.00 |

28.00 |

2.00 |

89.46 |

48.11 |

58.65 |

| 5 |

12.00 |

24.00 |

1.60 |

91.36 |

50.83 |

59.47 |

| 6 |

12.00 |

20.00 |

1.20 |

90.05 |

49.06 |

59.01 |

| 7 |

16.00 |

20.00 |

1.60 |

90.82 |

50.01 |

59.18 |

| 8 |

8.00 |

28.00 |

1.60 |

89.09 |

46.76 |

57.67 |

| 9 |

16.00 |

24.00 |

1.20 |

89.49 |

48.06 |

58.57 |

| 10 |

12.00 |

28.00 |

1.20 |

89.37 |

47.21 |

57.84 |

| 11 |

8.00 |

24.00 |

1.20 |

88.88 |

46.33 |

57.45 |

| 12 |

12.00 |

24.00 |

1.60 |

91.23 |

50.55 |

59.31 |

| 13 |

12.00 |

20.00 |

2.00 |

88.79 |

46.22 |

57.43 |

| 14 |

12.00 |

24.00 |

1.60 |

91.32 |

50.91 |

59.59 |

| 15 |

12.00 |

24.00 |

1.60 |

91.43 |

50.75 |

59.32 |

| 16 |

12.00 |

24.00 |

1.60 |

91.38 |

51.00 |

59.62 |

| 17 |

8.00 |

24.00 |

2.00 |

88.35 |

45.60 |

57.25 |

Table 6.

Comparison of Predictive Models.

Table 6.

Comparison of Predictive Models.

| Model |

R² (Testing) |

RMSE |

| ANN (This work) |

0.9515 |

1.12 |

| Polynomial SVM |

0.9012 |

2.45 |

| Genetic Algorithm |

0.9123 |

2.10 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

, n is the number of neurons).

, n is the number of neurons).