Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

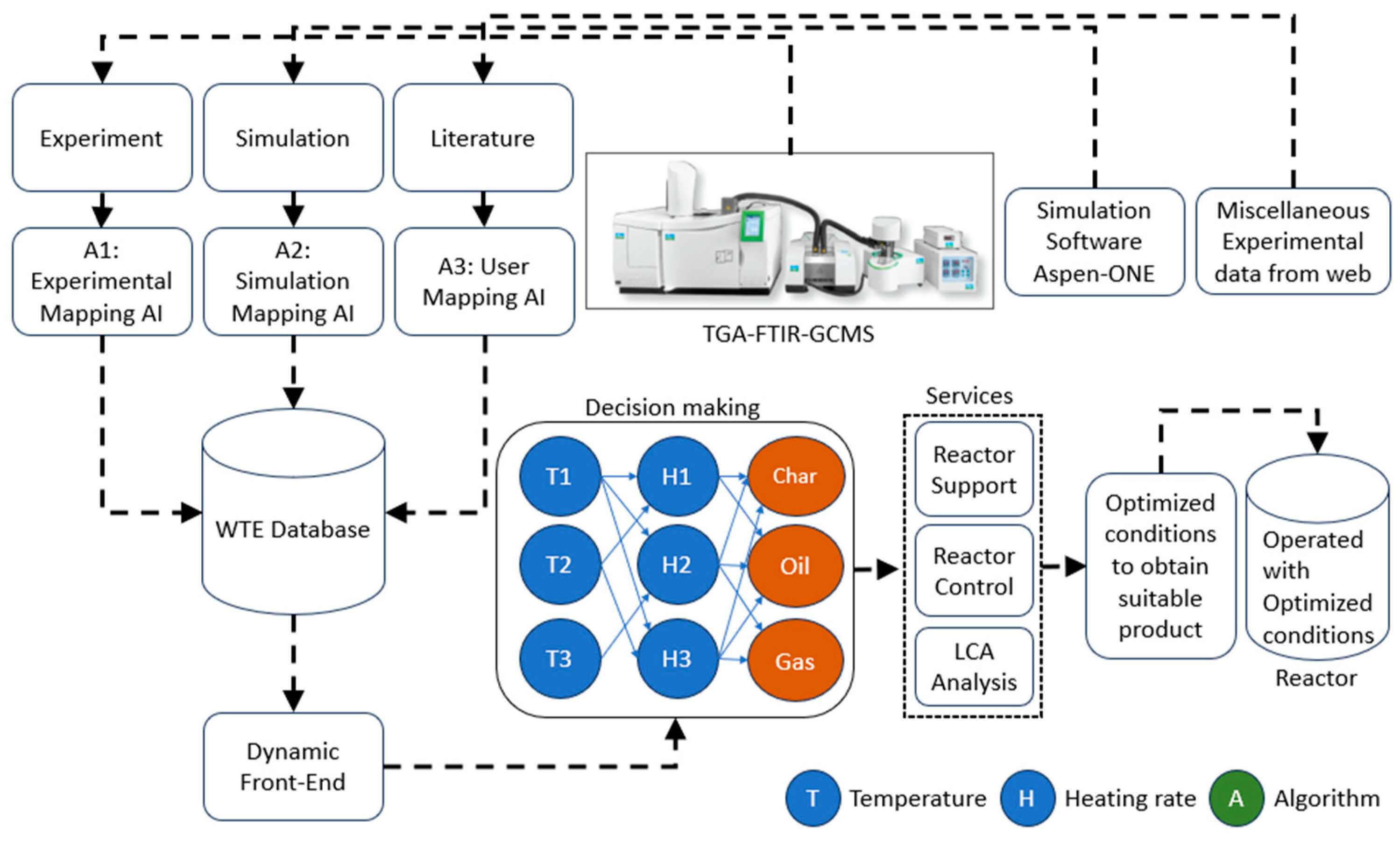

2.1. Integration of experimental setup (reactor) with TG-FTIR-GCMS system

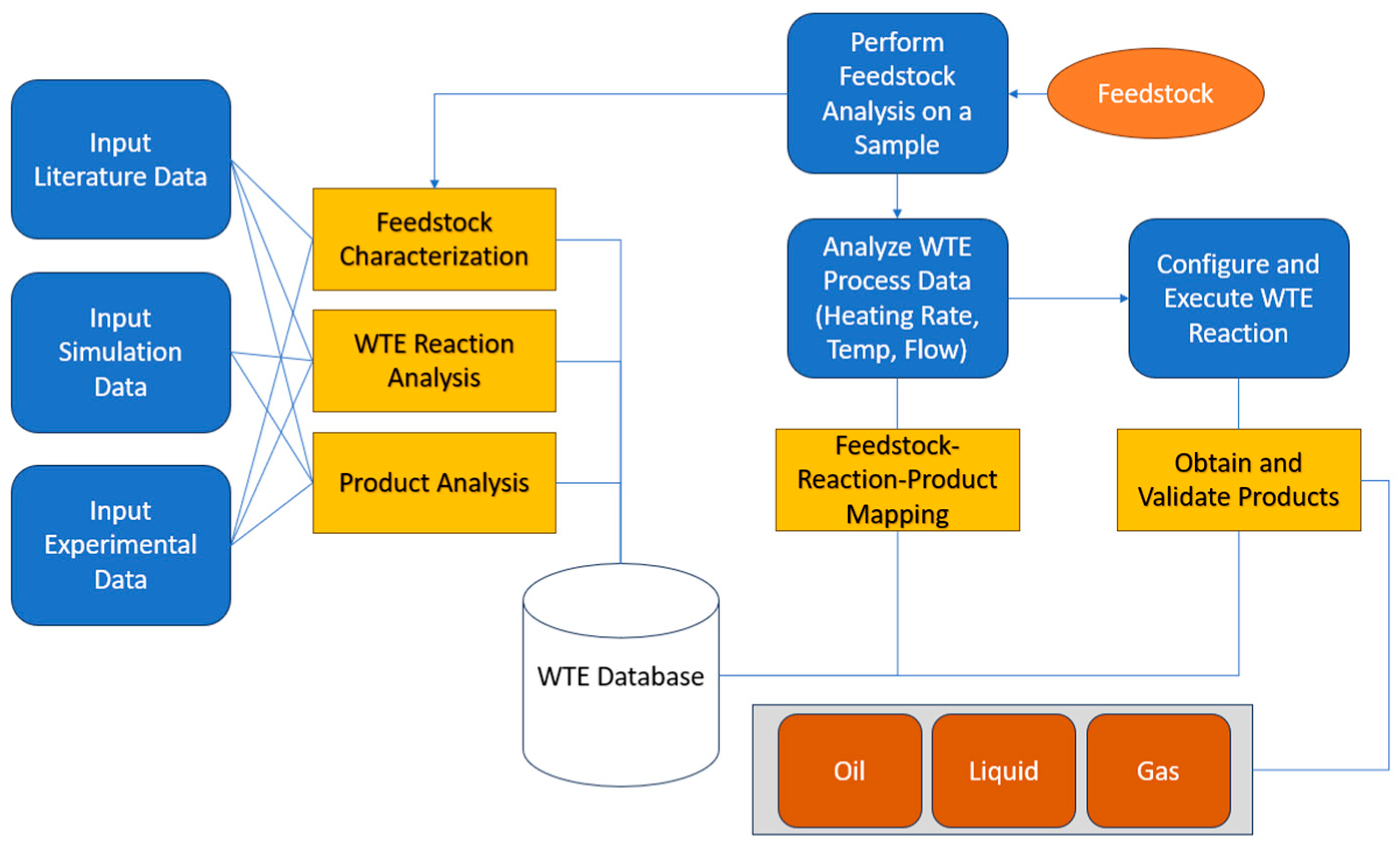

2.3. Process Model integrated with WTE database

2.4 Life cycle analysis (LCA)

3. Results and Discussion

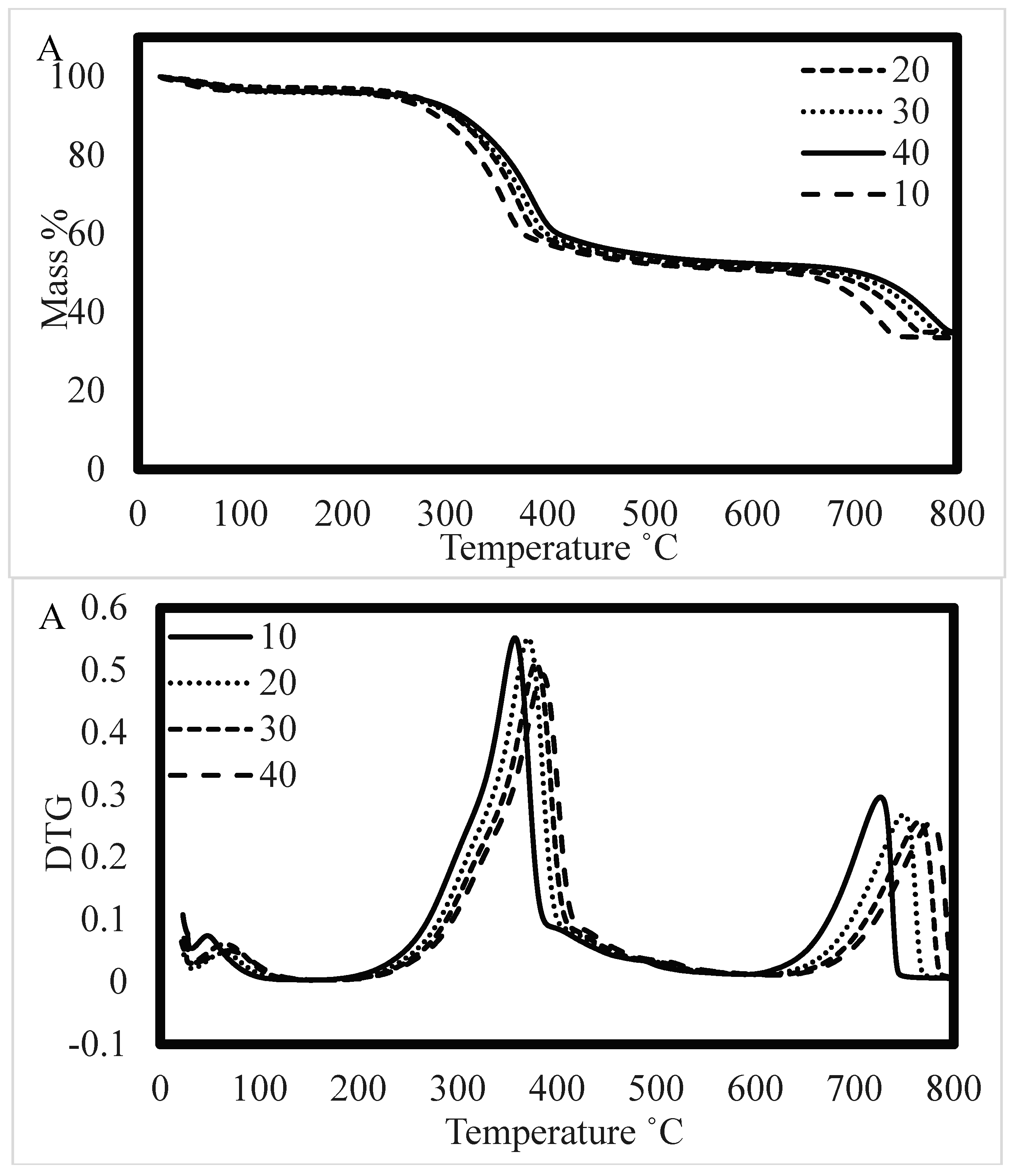

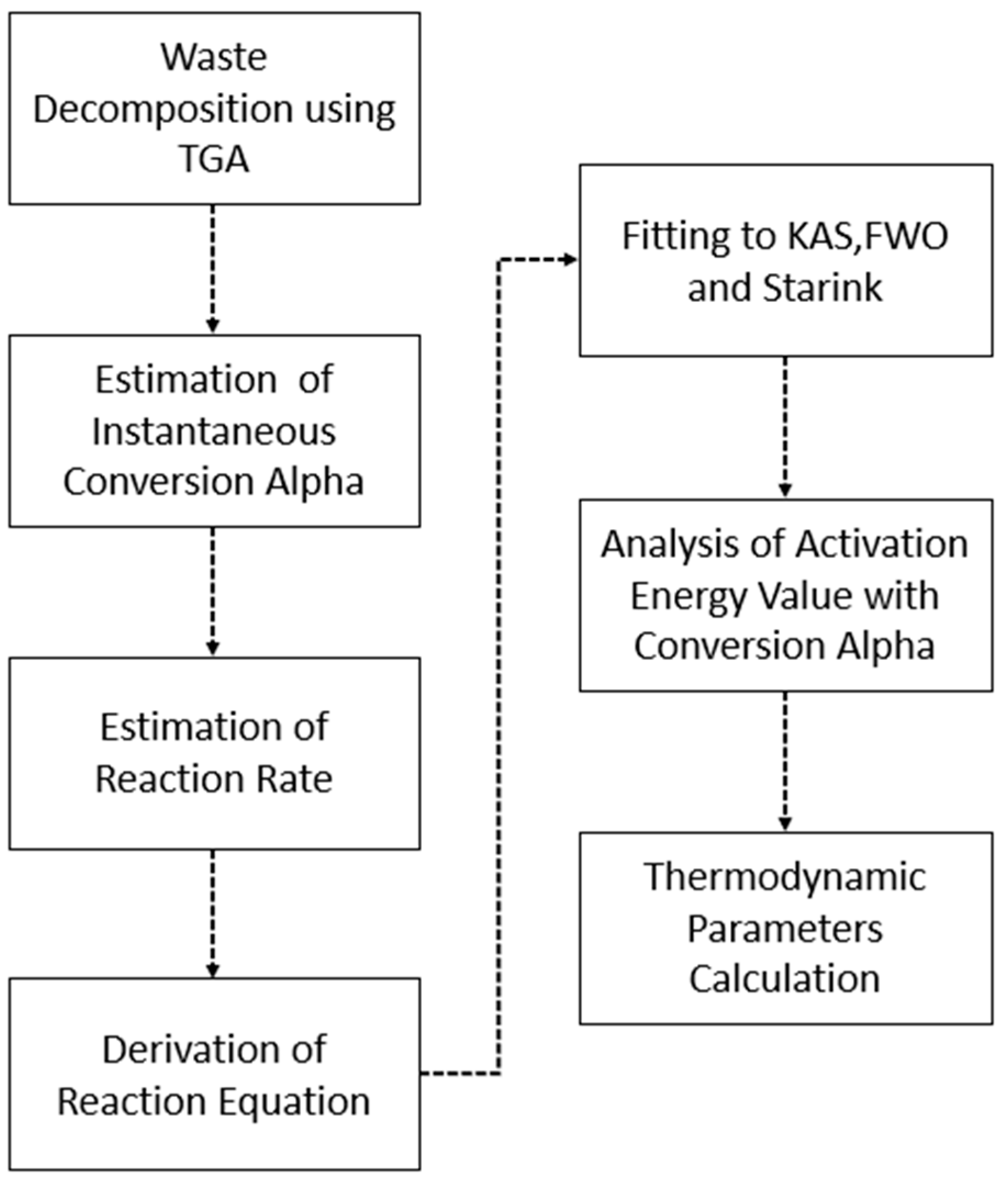

3.1. Integration of thermal analysis

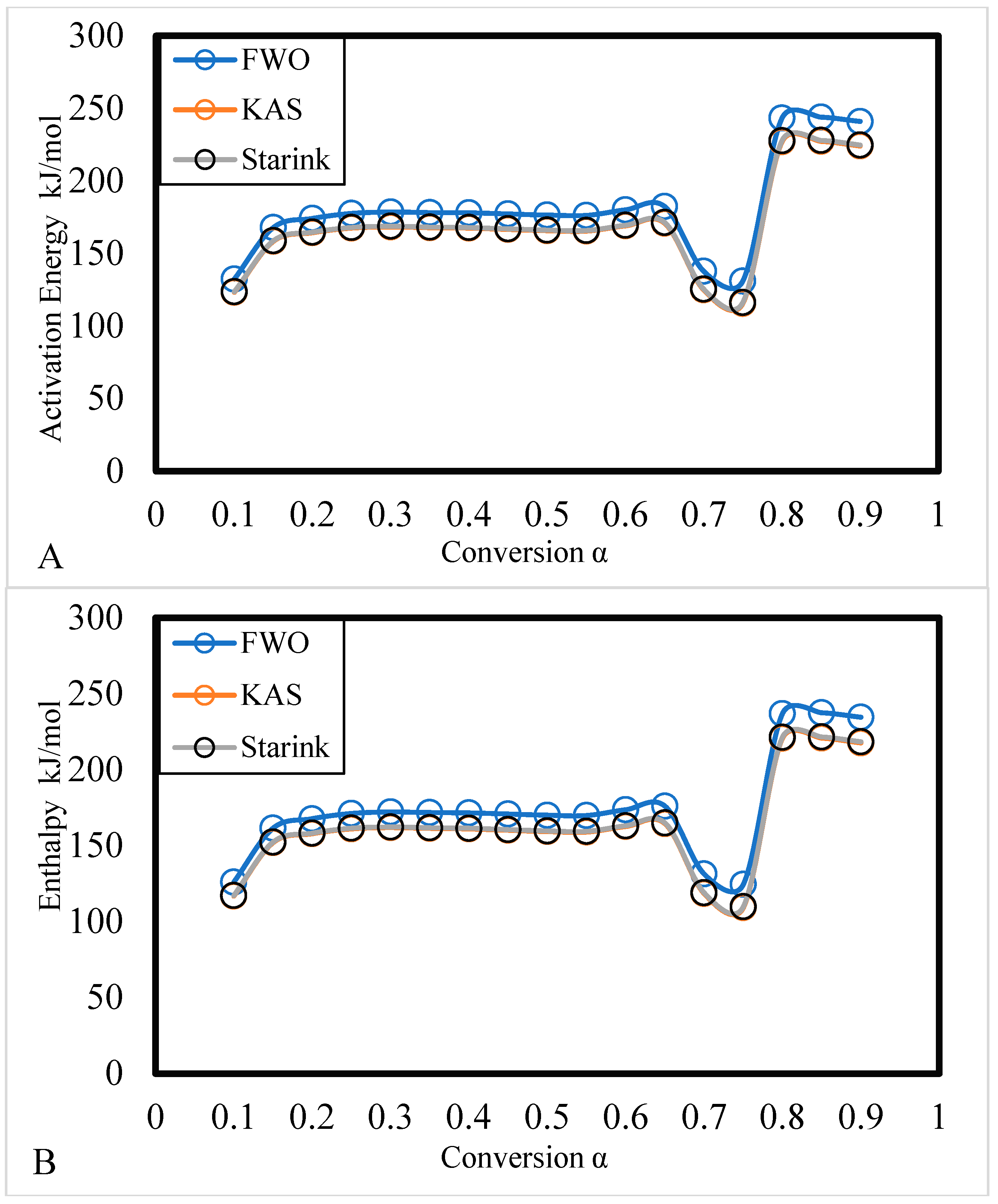

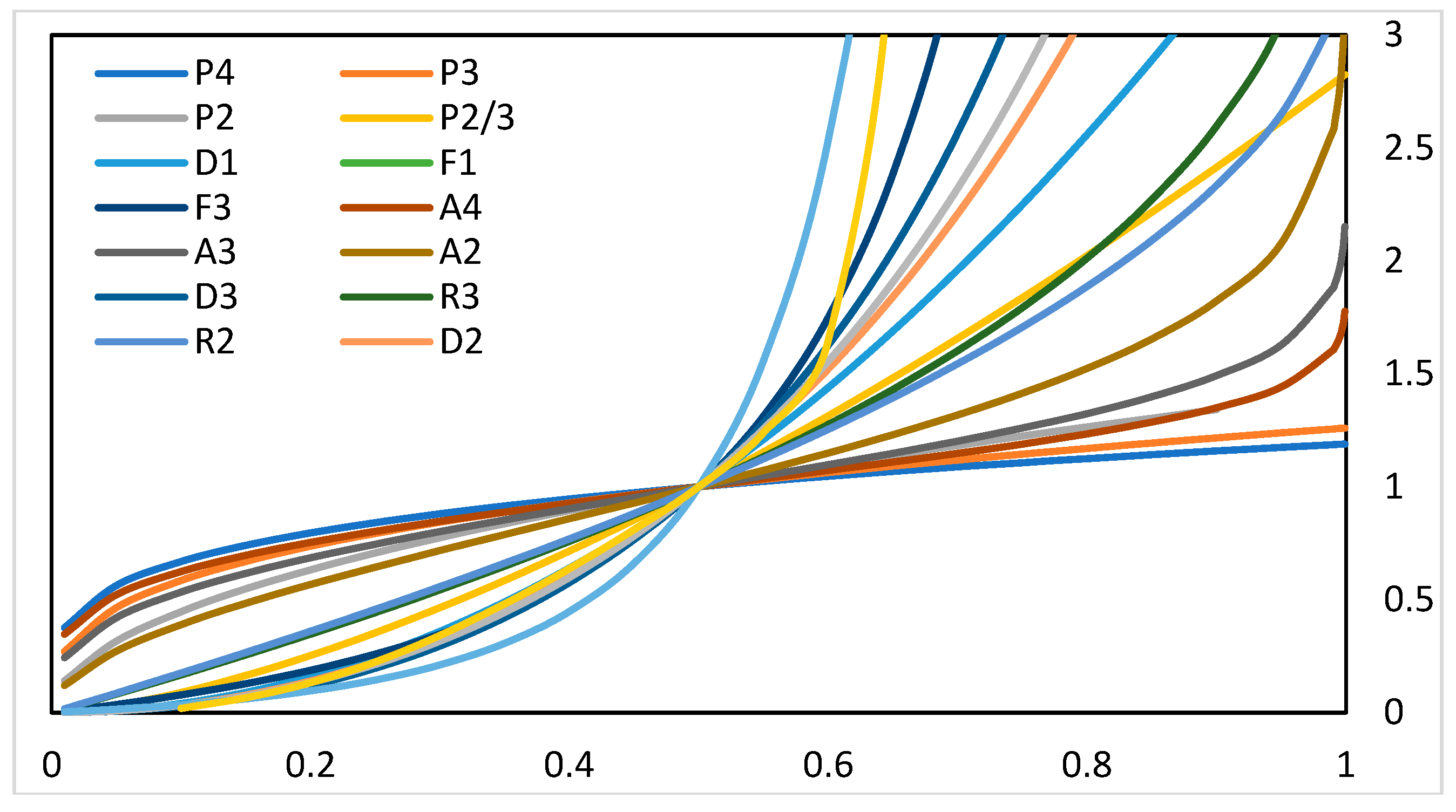

3.1.1. Kinetic Analysis

3.1.2. Thermodynamic Analysis

| Alpha | Activation Energy (E) kJ/mol | Pre-exponential factor (A) | R2 | Enthalpy (∆H) kJ/mol |

Gibbs Free Energy (∆G) kJ/mol |

Entropy (∆S) J/mol |

| FWO Model | ||||||

| .10 | 132.37 | 3.52E+97 | 0.68 | 126.02 | -1099.63 | 1606.35 |

| .15 | 167.92 | 2.54E+124 | 0.91 | 161.57 | -1456.38 | 2120.52 |

| .20 | 174.11 | 1.20E+129 | 0.96 | 167.77 | -1518.50 | 2210.04 |

| .25 | 177.56 | 4.84E+131 | 0.98 | 171.21 | -1553.09 | 2259.90 |

| .30 | 178.55 | 2.73E+132 | 0.99 | 172.21 | -1563.06 | 2274.27 |

| .35 | 178.17 | 1.40E+132 | 0.99 | 171.82 | -1559.20 | 2268.71 |

| .40 | 177.97 | 1.00E+132 | 1.00 | 171.63 | -1557.27 | 2265.93 |

| .45 | 177.19 | 2.55E+131 | 1.00 | 170.84 | -1549.39 | 2254.56 |

| .50 | 176.44 | 6.93E+130 | 0.99 | 170.10 | -1541.88 | 2243.74 |

| .55 | 176.26 | 5.05E+130 | 0.99 | 169.91 | -1540.05 | 2241.10 |

| .60 | 180.04 | 3.63E+133 | 0.98 | 173.70 | -1578.00 | 2295.80 |

| .65 | 182.40 | 2.20E+135 | 0.81 | 176.05 | -1601.66 | 2329.90 |

| .70 | 137.77 | 4.24E+101 | 0.61 | 131.42 | -1153.84 | 1684.49 |

| .75 | 130.94 | 2.95E+96 | 0.55 | 124.60 | -1085.32 | 1585.73 |

| .80 | 243.30 | 2.25E+181 | 0.98 | 236.96 | -2212.82 | 3210.72 |

| .85 | 243.87 | 6.02E+181 | 0.99 | 237.52 | -2218.49 | 3218.89 |

| .90 | 240.91 | 3.48E+179 | 1.00 | 234.56 | -2188.76 | 3176.04 |

| 185.03 | 178.69 | -1628.09 | 2367.99 | |||

| KAS Model | ||||||

| .10 | 123.22 | 4.33E+90 | 0.65 | 116.88 | -1007.85 | 1474.086 |

| .15 | 158.35 | 1.49E+117 | 0.90 | 152.00 | -1360.35 | 1982.111 |

| .20 | 164.26 | 4.39E+121 | 0.95 | 157.92 | -1419.70 | 2067.653 |

| .25 | 167.49 | 1.21E+124 | 0.98 | 161.15 | -1452.10 | 2114.354 |

| .30 | 168.30 | 4.95E+124 | 0.99 | 161.96 | -1460.24 | 2126.075 |

| .35 | 167.76 | 1.93E+124 | 0.99 | 161.42 | -1454.82 | 2118.263 |

| .40 | 167.44 | 1.11E+124 | 0.99 | 161.10 | -1451.60 | 2113.624 |

| .45 | 166.55 | 2.32E+123 | 1.00 | 160.20 | -1442.59 | 2100.643 |

| .50 | 165.69 | 5.26E+122 | 0.99 | 159.35 | -1434.02 | 2088.298 |

| .55 | 165.40 | 3.15E+122 | 0.99 | 159.05 | -1431.07 | 2084.034 |

| .60 | 169.01 | 1.70E+125 | 0.98 | 162.67 | -1467.36 | 2136.338 |

| .65 | 170.84 | 4.09E+126 | 0.79 | 164.50 | -1485.71 | 2162.784 |

| .70 | 124.87 | 7.69E+91 | 0.56 | 118.53 | -1024.44 | 1498 |

| .75 | 115.57 | 7.19E+84 | 0.48 | 109.22 | -931.07 | 1363.429 |

| .80 | 227.05 | 1.18E+169 | 0.98 | 220.70 | -2049.68 | 2975.598 |

| .85 | 227.27 | 1.73E+169 | 0.99 | 220.92 | -2051.91 | 2978.817 |

| .90 | 224.06 | 6.58E+166 | 1.00 | 217.72 | -2019.76 | 2932.471 |

| 172.77 | 166.43 | -1505.07 | 2190.69 | |||

| Starink Model | ||||||

| .10 | 123.59 | 8.19E+90 | 0.65 | 117.24 | -1011.52 | 1479.38 |

| .15 | 158.73 | 2.91E+117 | 0.91 | 152.39 | -1364.19 | 1987.65 |

| .20 | 164.66 | 8.72E+121 | 0.96 | 158.31 | -1423.65 | 2073.35 |

| .25 | 167.90 | 2.43E+124 | 0.98 | 161.55 | -1456.14 | 2120.18 |

| .30 | 168.71 | 1.01E+125 | 0.99 | 162.37 | -1464.35 | 2132.00 |

| .35 | 168.18 | 3.99E+124 | 0.99 | 161.84 | -1458.99 | 2124.28 |

| .40 | 167.86 | 2.30E+124 | 0.99 | 161.52 | -1455.82 | 2119.72 |

| .45 | 166.97 | 4.87E+123 | 1.00 | 160.63 | -1446.86 | 2106.80 |

| .50 | 166.12 | 1.11E+123 | 0.99 | 159.78 | -1438.34 | 2094.52 |

| .55 | 165.83 | 6.71E+122 | 0.99 | 159.49 | -1435.42 | 2090.32 |

| .60 | 169.45 | 3.66E+125 | 0.98 | 163.11 | -1471.78 | 2142.72 |

| .65 | 171.30 | 9.15E+126 | 0.79 | 164.96 | -1490.34 | 2169.47 |

| .70 | 125.39 | 1.89E+92 | 0.56 | 119.05 | -1029.62 | 1505.46 |

| .75 | 116.18 | 2.09E+85 | 0.49 | 109.84 | -937.24 | 1372.32 |

| .80 | 227.70 | 3.65E+169 | 0.98 | 221.35 | -2056.21 | 2985.00 |

| .85 | 227.93 | 5.50E+169 | 0.99 | 221.59 | -2058.58 | 2988.42 |

| .90 | 224.74 | 2.12E+167 | 1.00 | 218.39 | -2026.52 | 2942.21 |

| 173.26 | 166.92 | -1509.99 | 2197.78 | |||

3.2. Simulation and comparison of experimental vs model results

| Feedstock | Gasification | H2 | CO2 | CH4 | CO | C2H4 | C2H6 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE (polyethylene) | 750 C | 41.67 | 20.77 | 30.22 | 1.14 | 1.35 | 4.86 | [33] |

| PP (polypropylene) | 750 C | 36.99 | 27.82 | 26.57 | 1.68 | 0.86 | 6.08 | [33] |

| PC (polycarbonate) | 750 C | 36.35 | 36.80 | 23.19 | 2.34 | 0.27 | 1.06 | [33] |

| Plastic Waste | 650 – 1100 C | 64 | 4-6 | 3.30 | 25.7 | [36] | ||

| Plastic Waste (polyethylene box used for fruit packing) |

850 C – 1100 C | 40.86 | 0.37 | 9.10 | 0.1 | C3H8 (12.8) |

28 | [35] |

| thermoset-insulated wire and cable waste was investigated | 750 C (10-14 L in 20 g waste) |

4-7 | 10-13 | 7-13 | [37] | |||

| waste polyethylene | 700 C to 900 C | 16-36 | 35-20 | 21-9 | 20-27 | 3-4 | 2 | [32] |

| PE | 740 (Pyro) | 0.8 | 4.2 | 11.4 | 7.3 | [34] | ||

| PP | 760 (Pyro) | 0.7 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 6.4 | [34] | ||

| MSW1 | 750 | 0.46 | 3.3 | 0.03 | 21.67 | Simulation Work | ||

| MSW2 | 750 | 0.72 | 3.71 | 0.06 | 19.67 | Simulation Work | ||

| MSW3 | 750 | 0.57 | 4.86 | 0.03 | 32.78 | Simulation Work | ||

| MSW4 | 750 | 0.39 | 3.22 | 0.05 | 20.54 | Simulation Work | ||

| MSW5 | 750 | 0.42 | 4.51 | 0.02 | 24.89 | Simulation Work |

3.3. Integration of characteristics temperature profiles with degradation stages

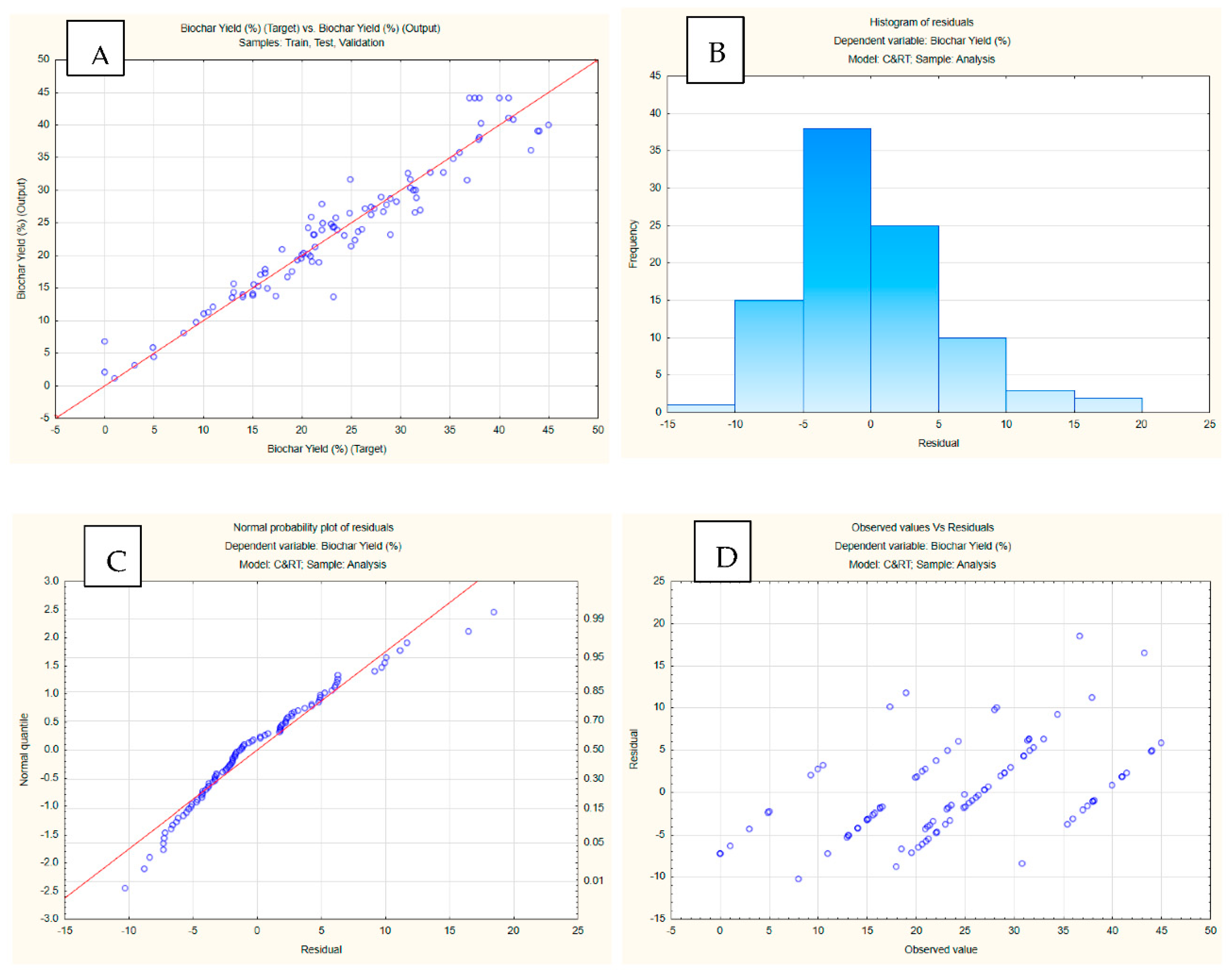

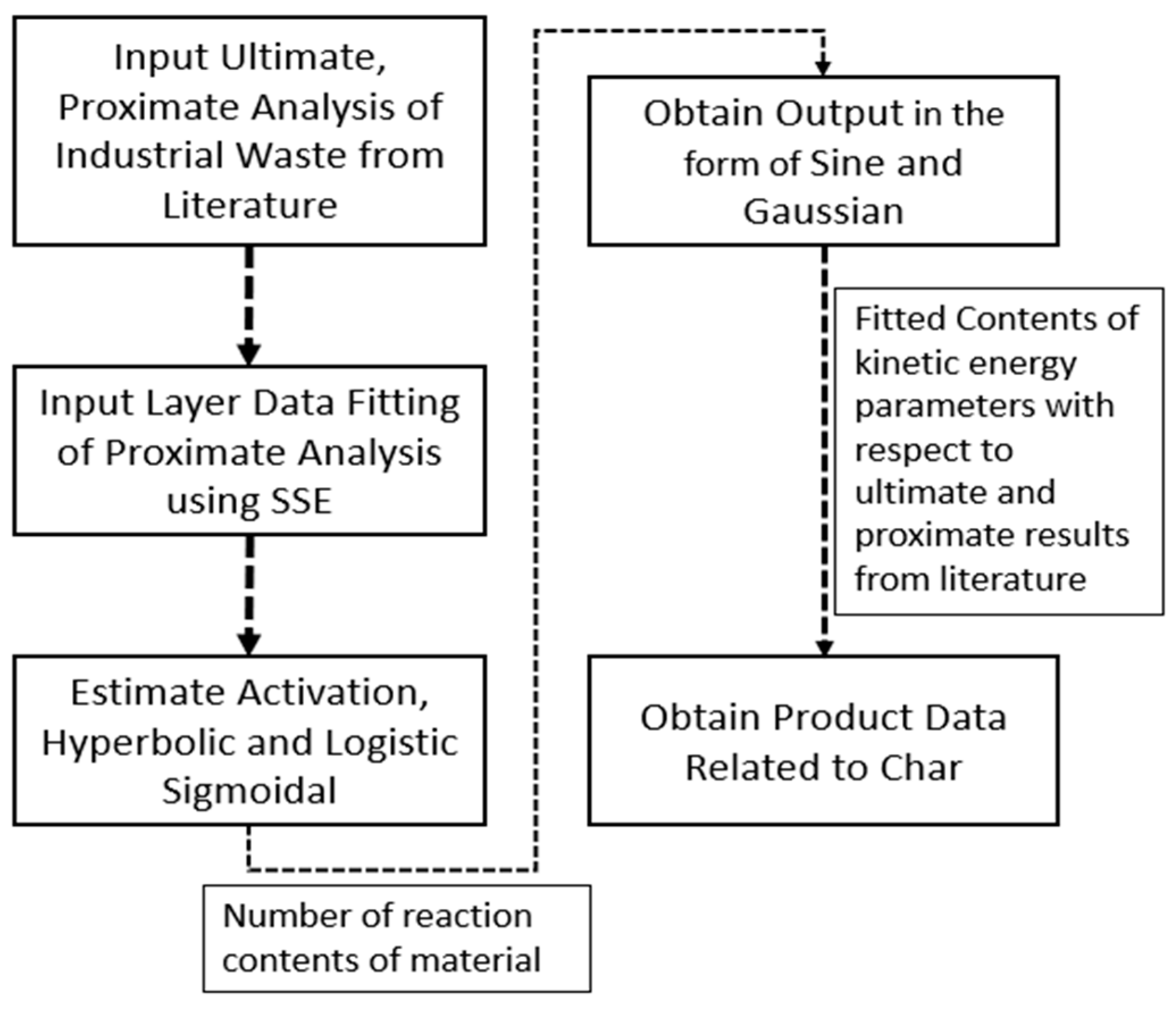

3.4. Machine learning integration

| Training perf. | Test perf. | Validation perf. | Training error | Test error | Validation error | Training algorithm | Error function | Hidden activation | Output activation | |

| MLP 17-4-1 | 0.965952 | 0.942402 | 0.983619 | 3.54672 | 8.411035 | 3.863005 | BFGS 39 | SOS | Exponential | Logistic |

| Name | Type | Mean | Std.Dev | Minimum | Maximum | |

| 1 | Mositure Biomass (%) | Continuous | 6.954043 | 3.647334 | 0.24 | 15.3 |

| 2 | Volatile Matter Biomass (%) | Continuous | 75.00191 | 10.64811 | 53.45 | 93.3 |

| 3 | Fixed Carbon Biomass (%) | Continuous | 12.05745 | 6.750243 | 0.5 | 26 |

| 4 | Ash Biomass (%) | Continuous | 6.439787 | 7.123538 | 0.1 | 30.77 |

| 5 | C Biomass (%) | Continuous | 47.84819 | 7.158147 | 26.99 | 63.85 |

| 6 | H Biomass (%) | Continuous | 6.223511 | 1.39789 | 2.2 | 8.77 |

| 7 | O Biomass (%) | Continuous | 41.735 | 11.70229 | 3.74 | 52.01 |

| 8 | N Biomass (%) | Continuous | 1.644362 | 2.053307 | 0 | 11.26 |

| 9 | C Polymer (%) | Continuous | 75.28128 | 17.49003 | 38.19 | 92.4 |

| 10 | H Polymer (%) | Continuous | 9.257128 | 3.663661 | 4.8 | 15.47 |

| 11 | O Polymer (%) | Continuous | 9.138617 | 13.94997 | 0 | 47.66 |

| 12 | N Polymer (%) | Continuous | 1.828936 | 2.816565 | 0 | 6.4 |

| 13 | Cl Polymer (%) | Continuous | 3.776596 | 13.85951 | 0 | 56.5 |

| 14 | Time (h) | Continuous | 0.440319 | 0.169226 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| 15 | Heating Rate (oC/min) | Continuous | 22.76596 | 26.78686 | 5 | 100 |

| 16 | Polymer Ratio (%) | Continuous | 41.06383 | 29.13358 | 0 | 100 |

| 17 | Temperature (oC) | Continuous | 638.4043 | 197.9807 | 390 | 1250 |

| 18 | Biochar Yield (%) | Continuous | 23.95819 | 10.57809 | 0 | 45 |

3.5. Life cycle analysis

| H2 | CO2 | CH4 | CO | |

| Percentage | 4 | 40.5 | 0.2 | 240 |

| Value $ | 12 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| cost | 48 | 141.75 | 0.24 | 48 |

| Revenue | $237.99/Run and $33,318/Year | |||

3.6. Process controller

4. Conclusion

References

- Liu, T.; McConkey, B.; Huffman, T.; Smith, S.; MacGregor, B.; Yemshanov, D.; Kulshreshtha, S. , Potential and impacts of renewable energy production from agricultural biomass in Canada. Applied Energy 2014, 130, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antar, M.; Lyu, D.; Nazari, M.; Shah, A.; Zhou, X.; Smith, D. L. , Biomass for a sustainable bioeconomy: An overview of world biomass production and utilization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 139, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourmelon, G. , Global plastic production rises, recycling lags. Vital Signs 2015, 22, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, C.; Pandyaswargo, A. H.; Onoda, H. , Environmental Impact of Plastic Recycling in Terms of Energy Consumption: A Comparison of Japan’s Mechanical and Chemical Recycling Technologies. Energies 2023, 16(5), 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiat, I.; Al-Ansari, T. , A review of carbon capture and utilisation as a CO2 abatement opportunity within the EWF nexus. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2021, 45, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D.; Misra, S.; Nizami, A.-S.; Rehan, M.; van Leeuwen, R.; Tabacchioni, S.; Goel, R.; Sarma, P.; Bakker, R.; Sharma, N.; Kwant, K.; Diels, L.; Elst, K. , Towards the development of a biobased economy in Europe and India. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39(6), 779–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J. M.; Bourtsalas, A. , Assessment of Co-Gasification Methods for Hydrogen Production from Biomass and Plastic Wastes. Energies 2023, 16(22), 7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Lopez Ruiz, V. R.; Lincaru, C.; Condrea, E. , Specialization Patterns for the Development of Renewable Energy Generation Technologies across Countries. Energies 2023, 16(20), 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathour, R. K.; Devi, M.; Dahiya, P.; Sharma, N.; Kaushik, N.; Kumari, D.; Kumar, P.; Baadhe, R. R.; Walia, A.; Bhatt, A. K. , Recent trends, opportunities and challenges in sustainable management of rice straw waste biomass for green biorefinery. Energies 2023, 16(3), 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L. S.; Stolz, C. M.; Amario, M.; Silva, A. L. N. d.; Haddad, A. N. , Use of Post-Consumer Plastics in the Production of Wood-Plastic Composites for Building Components: A Systematic Review. Energies 2023, 16(18), 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Bhavanam, A.; Jana, A.; Peela, N. R. , Co-pyrolysis of bamboo sawdust and plastic: Synergistic effects and kinetics. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsin, G.; Pütün, A. E. , A comparative study on co-pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass with polyethylene terephthalate, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride: Synergistic effects and product characteristics. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, D.; Jin, Q.; Deng, S.; Stančin, H.; Tan, H.; Mikulčić, H. , Synergistic effects of biomass and polyurethane co-pyrolysis on the yield, reactivity, and heating value of biochar at high temperatures. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 194, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsin, G.; Kılıç, M.; Apaydin-Varol, E.; Pütün, A. E.; Pütün, E. , A thermo-kinetic study on co-pyrolysis of oil shale and polyethylene terephthalate using TGA/FT-IR. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Yao, D.; Yang, H.; Shao, J.; Chen, H. , Thermal behavior, kinetics and gas evolution characteristics for the co-pyrolysis of real-world plastic and tyre wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, R.; Chong, C. T.; Asik, J. A.; Ani, F. N. , Optimization studies of microwave-induced co-pyrolysis of empty fruit bunches/waste truck tire using response surface methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Evrendilek, F.; Zhang, X.; Buyukada, M. , TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS analyses of pyrolysis behaviors and products of cattle manure in CO2 and N2 atmospheres: Kinetic, thermodynamic, and machine-learning models. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 195, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiminaitė, I.; González-Arias, J.; Striūgas, N.; Eimontas, J.; Seemann, M. , Syngas Production from Protective Face Masks through Pyrolysis/Steam Gasification. Energies 2023, 16(14), 5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, S.; Gravely, E.; Mosby, I.; Duncan, E.; Finnis, E.; Horgan, M.; LeBlanc, J.; Martin, R.; Neufeld, H. T.; Nixon, A.; Pant, L.; Shalla, V.; Fraser, E. , Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labour and rural communities. Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 68, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabee, W.; Saddler, J. , Bioethanol from lignocellulosics: status and perspectives in Canada. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101(13), 4806–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmey, J.; Ahiekpor, J. C.; Narra, S.; Achaw, O.-W.; Ansah, H. F. , Municipal Solid Waste Generation Trend and Bioenergy Recovery Potential: A Review. Energies 2023, 16(23), 7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ahmad, M. S.; Alhumade, H.; Elkamel, A.; Sammak, S.; Shen, B. , A hybrid kinetic and optimization approach for biomass pyrolysis: The hybrid scheme of the isoconversional methods, DAEM, and a parallel-reaction mechanism. Energy Convers. Manage. 2020, 208, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiwango, E.; A. Gabbar, H. Synergistic interactions, kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of co-pyrolysis of municipal paper and polypropylene waste. Waste Manage. 2022, 146, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumbach, G. D.; Alves, J. L. F.; Da Silva, J. C. G.; De Sena, R. F.; Marangoni, C.; Machado, R. A. F.; Bolzan, A. , Thermal investigation of plastic solid waste pyrolysis via the deconvolution technique using the asymmetric double sigmoidal function: Determination of the kinetic triplet, thermodynamic parameters, thermal lifetime and pyrolytic oil composition for clean energy recovery. Energy Conv. Manag. 2019, 200, 112031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, S.; Eimontas, J.; Striūgas, N.; Zakarauskas, K.; Praspaliauskas, M.; Abdelnaby, M. A. , Pyrolysis kinetic behavior and TG-FTIR-GC–MS analysis of metallised food packaging plastics. Fuel 2020, 282, 118737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, S. L.; Shah, Z.; Alves, J. L. F.; da Silva, J. C. G.; Iqbal, A. , Pyrolysis of the freshwater macroalgae Spirogyra crassa: evaluating its bioenergy potential using kinetic triplet and thermodynamic parameters. Renew. Energ. 2021, 179, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyavaram, S. R.; Uppala, L.; Sivaprakash, S.; Reddy, P. H. P. , Thermal behaviour of hydrochar derived from hydrothermal carbonization of food waste using leachate as moisture source: Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 373, 128734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Suvarna, M.; Li, L.; Pan, L.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Ok, Y. S.; Wang, X. , A review of computational modeling techniques for wet waste valorization: Research trends and future perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 133025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagali, A. A.; Hu, S.; Li, H.; Chi, H.; Qing, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Xiang, J. , Thermal behavior, synergistic effect and thermodynamic parameter evaluations of biomass/plastics co–pyrolysis in a concentrating photothermal TGA. Fuel 2023, 331, 125724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P. , In-depth analyses of kinetics, thermodynamics and solid reaction mechanism for pyrolysis of hazardous petroleum sludge based on isoconversional models for its energy potential. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2021, 146, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zaini, I. N.; Wang, S.; Mu, W.; Jönsson, P. G.; Yang, W. , Synergistic effect of the co-pyrolysis of cardboard and polyethylene: A kinetic and thermodynamic study. Energy 2021, 229, 120693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xiao, B.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Luo, S. , Syngas production from catalytic gasification of waste polyethylene: Influence of temperature on gas yield and composition. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34(3), 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Bian, C.; Wang, G.; Bai, B.; Xie, Y.; Jin, H. , Co-gasification of plastic wastes and soda lignin in supercritical water. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 388, 124277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogu, O.; Pelucchi, M.; Van de Vijver, R.; Van Steenberge, P. H. M.; D'Hooge, D. R.; Cuoci, A.; Mehl, M.; Frassoldati, A.; Faravelli, T.; Van Geem, K. M. , The chemistry of chemical recycling of solid plastic waste via pyrolysis and gasification: State-of-the-art, challenges, and future directions. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 84, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Gholizadeh, M.; Hu, X. , Cross-interaction during Co-gasification of wood, weed, plastic, tire and carton. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 250, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saebea, D.; Ruengrit, P.; Arpornwichanop, A.; Patcharavorachot, Y. , Gasification of plastic waste for synthesis gas production. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongen, A. , Methane-rich syngas production by gasification of thermoset waste plastics. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18(3), 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.; Kazan, D. , Pyrolysis kinetics and thermal characteristics of microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata and Tetraselmis sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 187, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A. A. D.; de Morais, L. C. , Kinetic parameters of red pepper waste as biomass to solid biofuel. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 204, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Kumar, P. , A novel pseudo-multicomponent isoconversional approach for the estimation of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of potato stalk thermal degradation. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 376, 128846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammohan, D.; Kishore, N.; Uppaluri, R. V. S. , Insights on kinetic triplets and thermodynamic analysis of Delonix regia biomass pyrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushwaha, R.; Singh, R. S.; Mohan, D. , Comparative study for sorption of arsenic on peanut shell biochar and modified peanut shell biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 375, 128831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Tian, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, T. , Pyrolytic characteristics of fine materials from municipal solid waste using TG-FTIR, Py-GC/MS, and deep learning approach: Kinetics, thermodynamics, and gaseous products distribution. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Cao, C.; Hu, H.; Ren, Y.; Guo, G.; Gong, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Yao, H. , Perspective on the disposal of PVC artificial leather via pyrolysis: Thermodynamics, kinetics, synergistic effects and reaction mechanism. Fuel 2022, 327, 125082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W.; Fan, M., Pyrolysis Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Typical Plastic Waste. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, (2), 2385-2390. [CrossRef]

- Zaker, A.; Chen, Z.; Zaheer-Uddin, M.; Guo, J. , Co-pyrolysis of sewage sludge and low-density polyethylene – A thermogravimetric study of thermo-kinetics and thermodynamic parameters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9(1), 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, B.; Yang, D.; Ming, X.; Jiang, Y.; Hao, J.; Qiao, Y.; Tian, Y. , TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS study on pyrolysis mechanism and products distribution of waste bicycle tire. Energy Conv. Manag. 2018, 175, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Bi, H.; Jiang, C.; Ni, Z.; Tian, J.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, Z.; Lin, Q. , Experimental study of the co-pyrolysis of sewage sludge and wet waste via TG-FTIR-GC and artificial neural network model: Synergistic effect, pyrolysis kinetics and gas products. Renew. Energ. 2022, 184, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Ding, L. , Investigation of co-pyrolysis characteristics and kinetics of municipal solid waste and paper sludge through TG-FTIR and DAEM. Thermochim. Acta 2021, 700, 178889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, I.; Tomić, T.; Katančić, Z.; Erceg, M.; Papuga, S.; Vuković, J. P.; Schneider, D. R. , Catalytic pyrolysis of mechanically non-recyclable waste plastics mixture: Kinetics and pyrolysis in laboratory-scale reactor. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 296, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ahmad, M. S.; Shen, B.; Yuan, P.; Shah, I. A.; Zhu, Q.; Ibrahim, M.; Bokhari, A.; Klemeš, J. J.; Elkamel, A. , Co-pyrolysis of lychee and plastic waste as a source of bioenergy through kinetic study and thermodynamic analysis. Energy 2022, 256, 124678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasertpong, P.; Onsree, T.; Khuenkaeo, N.; Tippayawong, N.; Lauterbach, J. , Exposing and understanding synergistic effects in co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastic waste via machine learning. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Xiao, H.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Naqvi, S. R., Prediction of Bio-oil Yield and Hydrogen Contents Based on Machine Learning Method: Effect of Biomass Compositions and Pyrolysis Conditions. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, (9), 11050-11060. [CrossRef]

| Conversion range (α) | Temperature range (K) | Reactions | Activation energy (Ea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α ≤ 0.17 | 25-380 | liberation of retained moisture and the simultaneous degradation of smaller sugar molecules | Increased from starting point to 100-150 kJ mol-1 |

| 0.17 ≤ α ≤ 0.5 | 380-470 | Degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin | Increased from 150-180 kJ mol-1, and then decreed from 180 to 140 kJ mol-1 |

| 0.5 ≤ α ≤ 0.8 | 470-520 | Degradation of lignin | from 180 to 220 kJ mol-1 |

| 0.8 ≤ α ≤ 1.0 | 520-800 | Lignin degradation and char formation | Decreased from 240 to 120 kJ mol-1 |

| Conversion range (α) | Temperature range (K) | Reactions | Activation energy (Ea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α ≤ 0.17 | 25-370 | liberation of retained moisture and the simultaneous degradation of smaller sugar molecules | Increased from starting point to 100-140 kJ mol-1 |

| 0.17 ≤ α ≤ 0.5 | 370-480 | Degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin | Increased from 140-190 kJ mol-1, and then decreed from slightly with 5 kJ mol-1 and |

| 0.5 ≤ α ≤ 0.8 | 480-510 | Degradation of lignin | Increased from 190 to 260 kJ mol-1 |

| 0.8 ≤ α ≤ 1.0 | 510-800 | Lignin degradation and char formation | Decreased from 260 to 110 kJ mol-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).