Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

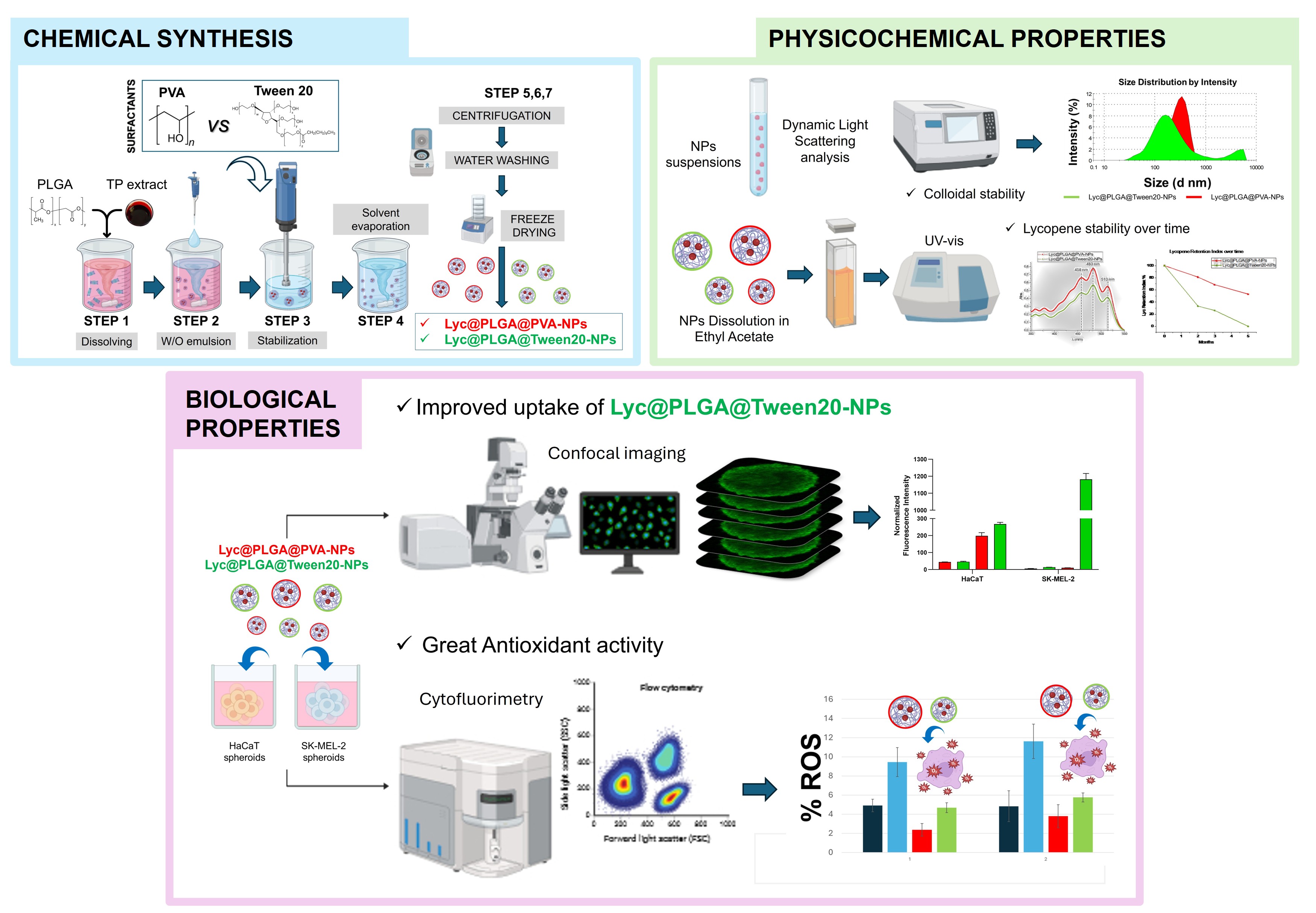

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Analysis of Lyc in the TP Extract

2.3. Preparation of Lyc-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles

2.4. Characterization of Lyc-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles

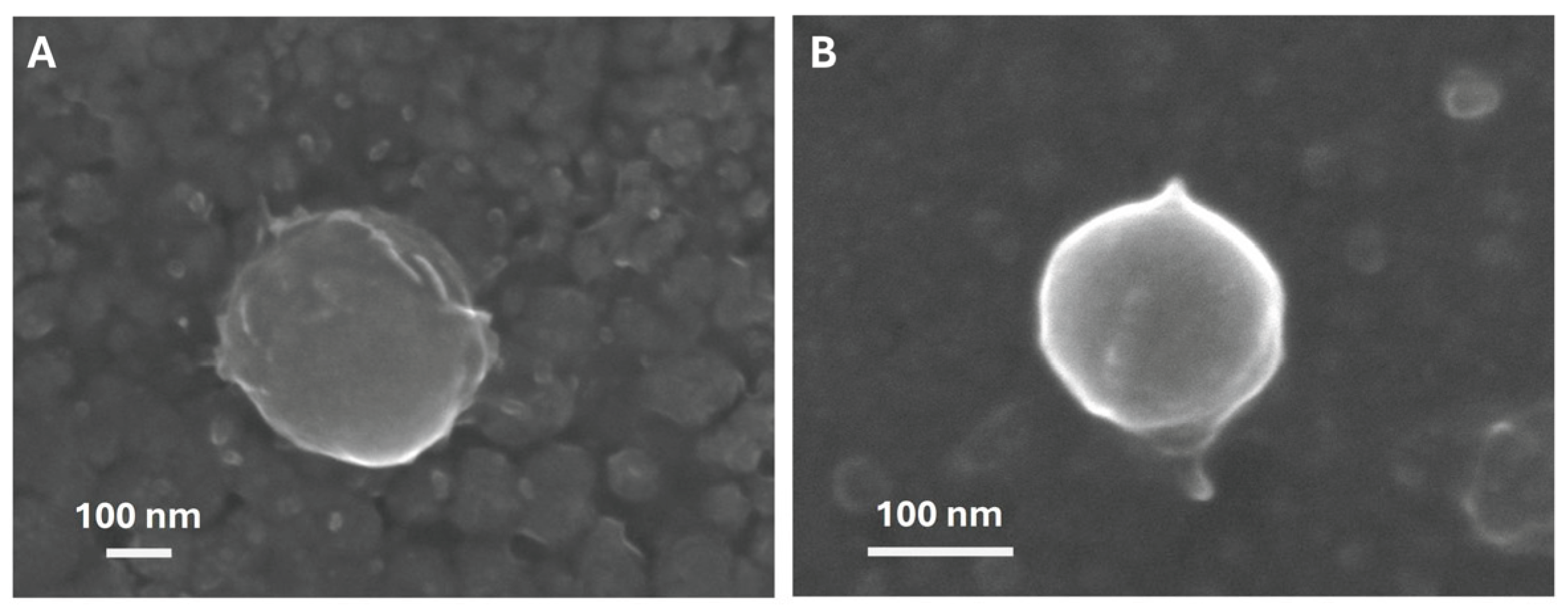

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4.2. Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis

2.4.3. UV–vis Assay

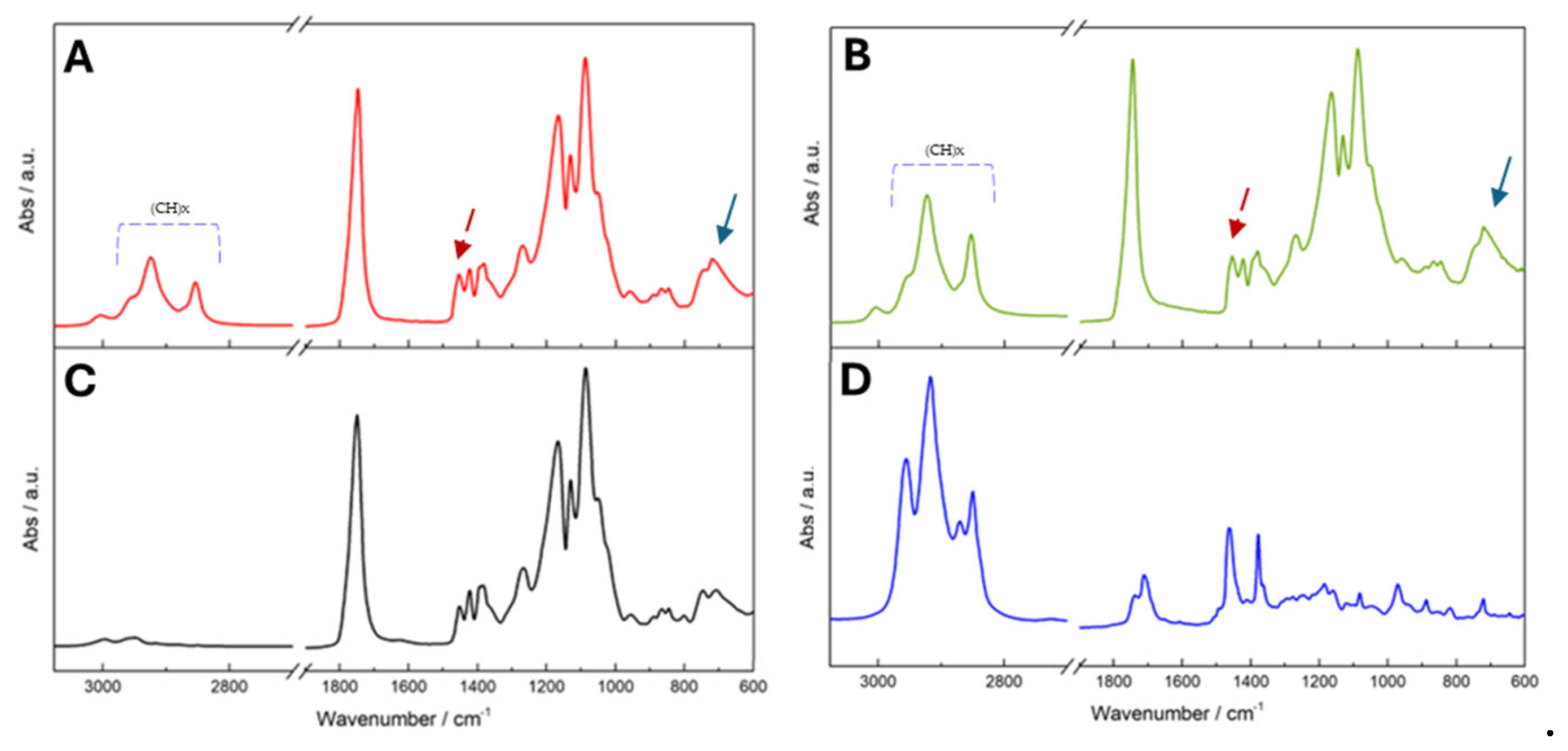

2.4.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.5. Determination of Free Radical Scavenging Activity

2.6. Stability of Lyc-Loaded PLGA NPs

2.7. In Vitro Biological Studies of Lyc-Loaded PLGA NPs

2.7.1. Cell Culture and Spheroids Formation

2.7.2. Cell Viability Test by MTT Assay

2.7.3. Cellular Uptake of Lyc-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles by Confocal Imaging

2.7.4. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Measurement by DCFDA Assay

3. Results

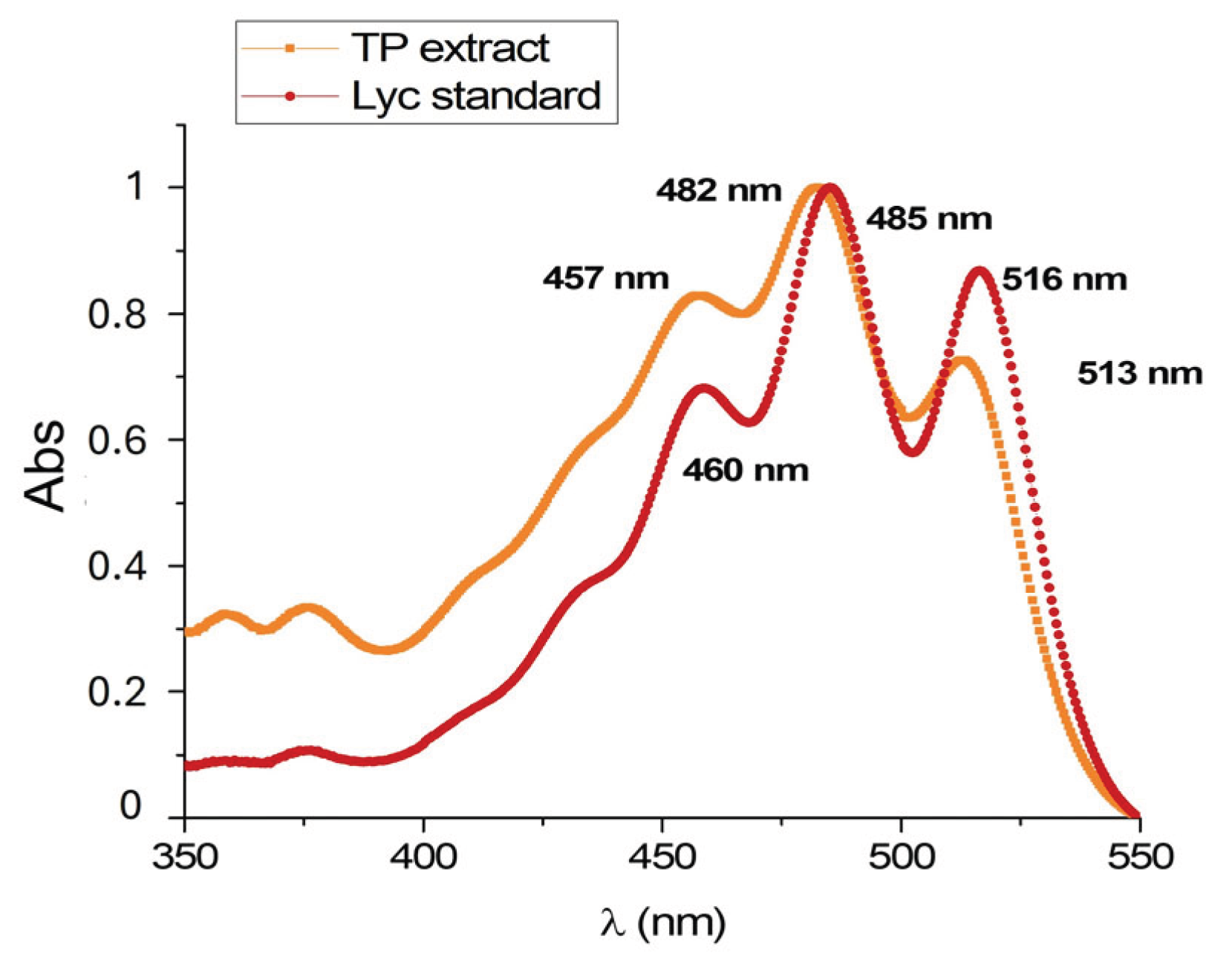

3.1. Characterization of TP Extract

3.2. Charaterization of Lyc@PLGA-NPs

3.2.1. Influence of Surfactants on NPs Physicochemical Properties

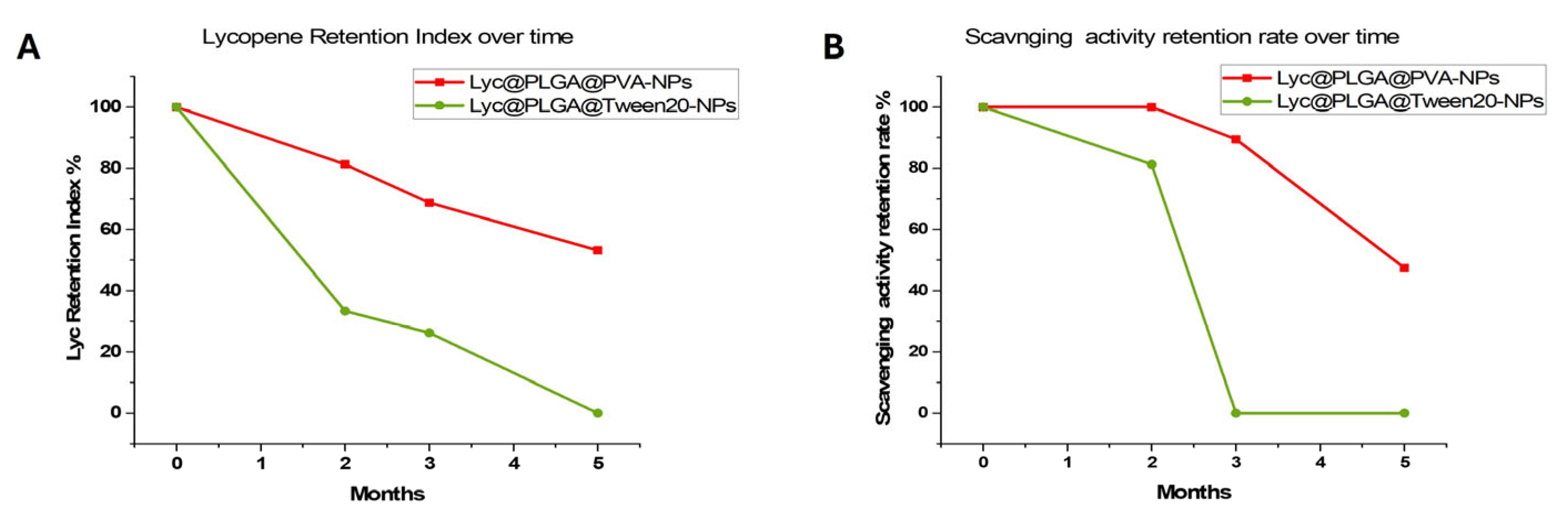

3.2.2. Influence of Surfactants on Lyc Encapsulation and Stability

3.3. Influence of Surfactants on Lyc@PLGA-NPs Interaction with HaCaT and SK-MEL-2 Spheroids

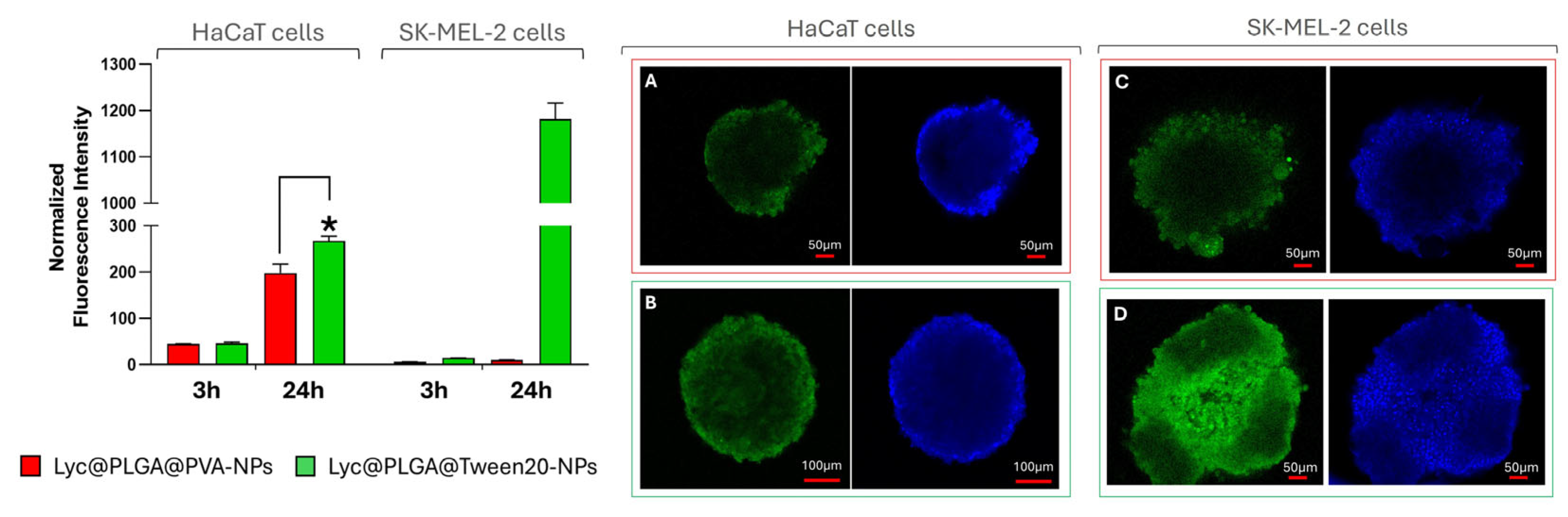

3.3.1. Cells Viability and Uptake of Lyc@PLGA-NPs

3.3.2. Antioxidant Activity of Lyc@PLGA-NPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Lyc | Lycopene |

| PLGA | Poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| PLGA-NPs | PLGA nanoparticles |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| Lyc@PLGA-NPs | Lycopene loaded PLGA nanoparticles |

| Lyc@PLGA@PVA-NPs | Lycopene loaded PLGA nanoparticles with PVA |

| Lyc@PLGA@Tween20-NPs | Lycopene loaded PLGA nanoparticles with Tween20 |

| SC-CO2 | Supercritical CO₂ |

| TP | Tomato peel |

References

- Rodríguez-Mena, A.; Ochoa-Martínez, L.A.; González-Herrera, S.M.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, O.M.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Natural Pigments of Plant Origin: Classification, Extraction and Application in Foods. Food Chemistry 2023, 398, 133908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudzyńska, P.; Sionkowska, A.; Grisel, M. Plant-Derived Colorants for Food, Cosmetic and Textile Industries: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, M.; Iancu, P.; Plesu, V.; Bildea, C.S. Carotenoids Recovery Enhancement by Supercritical CO2 Extraction from Tomato Using Seed Oils as Modifiers. Processes 2022, 10, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Biotech Entrepreneurship: From Idea to Business: A European Perspective; Matei, F., Zirra, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-22140-9. [Google Scholar]

- Caseiro, M.; Ascenso, A.; Costa, A.; Creagh-Flynn, J.; Johnson, M.; Simões, S. Lycopene in Human Health. LWT 2020, 127, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Sina, A.A.I.; Khandker, S.S.; Neesa, L.; Tanvir, E.M.; Kabir, A.; Khalil, M.I.; Gan, S.H. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes and Their Impact on Human Health and Disease: A Review. Foods 2020, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squillace, P.; Adani, F.; Scaglia, B. Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Tomato Pomace: Evaluation of the Solubility of Lycopene in Tomato Oil as Limiting Factor of the Process Performance. Food Chemistry 2020, 315, 126224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalcea, L.; Crăciunescu, O.; Gheonea (Dima), I.; Prelipcean, A.-M.; Enachi, E.; Barbu, V.; Bahrim, G.E.; Râpeanu, G.; Oancea, A.; Stănciuc, N. Supercritical CO2 Extraction and Microencapsulation of Lycopene-Enriched Oleoresins from Tomato Peels: Evidence on Antiproliferative and Cytocompatibility Activities. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsafi, S.R.; Rostamabadi, H.; Babazadeh, A.; Tarhan, Ö.; Rashidinejad, A.; Boostani, S.; Khoshnoudi-Nia, S.; Akbari-Alavijeh, S.; Shaddel, R.; Jafari, S.M. Lycopene Nanodelivery Systems; Recent Advances. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 119, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.C.; De Camargo, B.A.F.; De Araújo, J.T.C.; Chorilli, M. Lycopene: From Tomato to Its Nutraceutical Use and Its Association with Nanotechnology. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 118, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.D.G.N.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Souza, J.; Oliveira, A.; Gullón, B.; De Souza De Almeida Leite, J.R.; Pintado, M. Bio-Availability, Anticancer Potential, and Chemical Data of Lycopene: An Overview and Technological Prospecting. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.S.; Hoyos, C.G.; Molina-Ramírez, C.; Velásquez-Cock, J.; Vélez, L.; Gañán, P.; Eceiza, A.; Goff, H.D.; Zuluaga, R. Extraction and Preservation of Lycopene: A Review of the Advancements Offered by the Value Chain of Nanotechnology. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021, 116, 1120–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascenso, A.; Pinho, S.; Eleutério, C.; Praça, F.G.; Bentley, M.V.L.B.; Oliveira, H.; Santos, C.; Silva, O.; Simões, S. Lycopene from Tomatoes: Vesicular Nanocarrier Formulations for Dermal Delivery. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7284–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butnariu, M.V.; Giuchici, C.V. The Use of Some Nanoemulsions Based on Aqueous Propolis and Lycopene Extract in the Skin’s Protective Mechanisms against UVA Radiation. J Nanobiotechnol 2011, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.B.; VanDeWall, H.; Li, H.T.; Venugopal, V.; Li, H.K.; Naydin, S.; Hosmer, J.; Levendusky, M.; Zheng, H.; Bentley, M.V.L.B.; et al. Topical Delivery of Lycopene Using Microemulsions: Enhanced Skin Penetration and Tissue Antioxidant Activity. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2010, 99, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, F.; Vergaro, V.; De Castro, F.; Biondo, F.; Suranna, G.P.; Papadia, P.; Fanizzi, F.P.; Rongai, D.; Ciccarella, G. Enhanced Bioactivity of Pomegranate Peel Extract Following Controlled Release from CaCO3 Nanocrystals. Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications 2022, 2022, 6341298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakoudi, A.; Spanidi, E.; Mourtzinos, I.; Gardikis, K. Innovative Delivery Systems Loaded with Plant Bioactive Ingredients: Formulation Approaches and Applications. Plants 2021, 10, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, F.; Schiavi, D.; Ciarroni, S.; Tagliavento, V.; De Stradis, A.; Vergaro, V.; Suranna, G.P.; Balestra, G.M.; Ciccarella, G. Thymol-Nanoparticles as Effective Biocides against the Quarantine Pathogen Xylella Fastidiosa. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassarre, F.; Schiavi, D.; Di Lorenzo, V.; Biondo, F.; Vergaro, V.; Colangelo, G.; Balestra, G.M.; Ciccarella, G. Cellulose Nanocrystal-Based Emulsion of Thyme Essential Oil: Preparation and Characterisation as Sustainable Crop Protection Tool. Molecules 2023, 28, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonogi, S.; Riangjanapatee, P. Physicochemical Characterization of Lycopene-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Formulations for Topical Administration. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2015, 478, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanpipit, N.; Mattariganont, S.; Janphuang, P.; Rongsak, J.; Daduang, S.; Chulikhit, Y.; Thapphasaraphong, S. Comparative Study of Lycopene-Loaded Niosomes Prepared by Microfluidic and Thin-Film Hydration Techniques for UVB Protection and Anti-Hyperpigmentation Activity. IJMS 2024, 25, 11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaya-Mercado, J.D.; Garmyn, M.; Gilchrest, B.A.; Russell, R.M. Skin Lycopene Is Destroyed Preferentially over β-Carotene during Ultraviolet Irradiation in Humans. The Journal of Nutrition 1995, 125, 1854–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calniquer, G.; Khanin, M.; Ovadia, H.; Linnewiel-Hermoni, K.; Stepensky, D.; Trachtenberg, A.; Sedlov, T.; Braverman, O.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Combined Effects of Carotenoids and Polyphenols in Balancing the Response of Skin Cells to UV Irradiation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, Z.; Gao, D.; Saladi, R.N.; Lu, Y.; Lebwohl, M.; Wei, H. Protective Effects of Lycopene Against Ultraviolet B-Induced Photodamage. Nutrition and Cancer 2003, 47, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaleddine, A.; Urrutigoïty, M.; Bouajila, J.; Merah, O.; Evon, P.; De Caro, P. Ecodesigned Formulations with Tomato Pomace Extracts. Cosmetics 2022, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkabinde, L.A.; Shoba-Zikhali, L.N.N.; Semete-Makokotlela, B.; Kalombo, L.; Swai, H.; Grobler, A.; Hamman, J.H. Poly (D,L-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanoparticles: Uptake by Epithelial Cells and Cytotoxicity. Express Polym. Lett. 2014, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, M.; Radulović, A.; Jordović, B.; Uskoković, D. Poly(DL-Lactide-co-Glycolide) Nanospheres for the Sustained Release of Folic Acid. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2008, 4, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, G.; Hofland, L.J.; Dogan, F.; Giamas, G.; Gagliano, T.; Zatelli, M.C. Evaluation of Spheroid 3D Culture Methods to Study a Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasm Cell Line. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, S.; Cordelières, F.P. A Guided Tour into Subcellular Colocalization Analysis in Light Microscopy. Journal of Microscopy 2006, 224, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joutsen, J.; Da Silva, A.J.; Luoto, J.C.; Budzynski, M.A.; Nylund, A.S.; De Thonel, A.; Concordet, J.-P.; Mezger, V.; Sabéran-Djoneidi, D.; Henriksson, E.; et al. Heat Shock Factor 2 Protects against Proteotoxicity by Maintaining Cell-Cell Adhesion. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 583–597.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.C.; Ombredane, A.S.; Souza, J.M.T.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Plácido, A.; Amorim, A.D.G.N.; Barbosa, E.A.; Lima, F.C.D.A.; Ropke, C.D.; Alves, M.M.M.; et al. Lycopene-Rich Extract from Red Guava ( Psidium Guajava L.) Displays Cytotoxic Effect against Human Breast Adenocarcinoma Cell Line MCF-7 via an Apoptotic-like Pathway. Food Research International 2018, 105, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Cheng, D.; Niu, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, A. Properties of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) and Progress of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)-Based Biodegradable Materials in Biomedical Research. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C. Tuning the Size of Poly(Lactic-co-glycolic Acid) (PLGA) Nanoparticles Fabricated by Nanoprecipitation. Biotechnology Journal 2018, 13, 1700203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.T.; Haes, A.J. What Does Nanoparticle Stability Mean? J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 16495–16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.A.; Feng, S.-S. Effects of Particle Size and Surface Modification on Cellular Uptake and Biodistribution of Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Pharm Res 2013, 30, 2512–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatin, S.; Maleki Dizaj, S.; Yari Khosroushahi, A. Effect of the Surface Modification, Size, and Shape on Cellular Uptake of Nanoparticles. Cell Biology International 2015, 39, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, H.; Hernández-Parra, H.; Bernal-Chávez, S.A.; Prado-Audelo, M.L.D.; Caballero-Florán, I.H.; Borbolla-Jiménez, F.V.; González-Torres, M.; Magaña, J.J.; Leyva-Gómez, G. Non-Ionic Surfactants for Stabilization of Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biomedical Uses. Materials 2021, 14, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefalt, G.; Ruiz-Cabello, F.J.M.; Borkovec, M. Interaction Forces, Heteroaggregation, and Deposition Involving Charged Colloidal Particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 6346–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, K.; Qin, W.; Ma, L.; Gurzadyan, G.G.; Tang, B.Z.; Liu, B. Eccentric Loading of Fluorogen with Aggregation-Induced Emission in PLGA Matrix Increases Nanoparticle Fluorescence Quantum Yield for Targeted Cellular Imaging. Small 2013, 9, 2012–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zou, L.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Shi, S. PLGA Nanoparticles Loaded with Curcumin Produced Luminescence for Cell Bioimaging. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 639, 122944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Andrades, E.O.; Da Costa, J.M.A.R.; De Lima Neto, F.E.M.; De Araujo, A.R.; De Oliveira Silva Ribeiro, F.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; De Jesus Oliveira, A.C.; Sobrinho, J.L.S.; De Almeida, M.P.; Carvalho, A.P.; et al. Acetylated Cashew Gum and Fucan for Incorporation of Lycopene Rich Extract from Red Guava (Psidium Guajava L.) in Nanostructured Systems: Antioxidant and Antitumor Capacity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 191, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Madan, P.; Lin, S. Effect of Process and Formulation Variables on the Preparation of Parenteral Paclitaxel-Loaded Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles: A Co-Surfactant Study. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016, 11, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, S.; Rahman, M.; Kohli, K. Quality-by-Design Approach as a Systematic Tool for the Development of Nanopharmaceutical Products. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Su, J.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y. Improved Stability and Biocompatibility of Lycopene Liposomes with Sodium Caseinate and PEG Coating. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 311, 143685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhoond Zardini, A.; Mohebbi, M.; Farhoosh, R.; Bolurian, S. Production and Characterization of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers and Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Containing Lycopene for Food Fortification. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nardo, T.; Shiroma-Kian, C.; Halim, Y.; Francis, D.; Rodriguez-Saona, L.E. Rapid and Simultaneous Determination of Lycopene and β-Carotene Contents in Tomato Juice by Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Tong, Q.; Jafari, S.M.; Assadpour, E.; Shehzad, Q.; Aadil, R.M.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rashed, M.M.A.; Mushtaq, B.S.; Ashraf, W. Carotenoid-Loaded Nanocarriers: A Comprehensive Review. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 275, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.T.; Maqsood, S.; Ikram, A.; Khan, A.A.; Raza, A.; Ahmad, A.; Gnedeka, K.T. Encapsulation Techniques of Carotenoids and Their Multifunctional Applications in Food and Health: An Overview. Food Science & Nutrition 2025, 13, e70310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, D.; Keddari, S.; Boufadi, M.Y.; Bessad, L. Lycopene Purification with DMSO Anti-Solvent: Optimization Using Box-Behnken’s Experimental Design and Evaluation of the Synergic Effect between Lycopene and Ammi Visnaga. L Essential Oil. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6335–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmawati, A.; Utami, W.; Yuliani, R.; Da’i, M.; Nafarin, A. Effect of Tween 80 on Nanoparticle Preparation of Modified Chitosan for Targeted Delivery of Combination Doxorubicin and Curcumin Analogue. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 311, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misir, J.; Kassama, L. Nanoencapsulation of Lycopene by PLGA: Effect on Physicochemical Properties and Extended-Release Kinetics in a Simulated GIT System. LWT 2025, 225, 117747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makou, N.B.; Javadi, A.; Anarjan, N.; Torbati, M. Simultaneous Extraction and Nanoemulsification of Lycopene from Tomato Waste: Optimization and Stability Studies of Lycopene Nanoemulsions in Selected Food System. Food Measure 2024, 18, 9671–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnanç Horuz, T.; Belibağlı, K.B. Nanoencapsulation by Electrospinning to Improve Stability and Water Solubility of Carotenoids Extracted from Tomato Peels. Food Chemistry 2018, 268, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Jin, F.; Wang, F. Walnut Protein Isolate-Epigallocatechin Gallate Nanoparticles: A Functional Carrier Enhanced Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Lycopene. Food Research International 2024, 189, 114536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, L.; Morelli, L.; Ochoa, E.; Labra, M.; Fiandra, L.; Palugan, L.; Prosperi, D.; Colombo, M. The Emerging Role of Nanotechnology in Skincare. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 293, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Jeong, S.H.; Shin, W.U.; Lee, G.; Oh, C.; Son, S.W. Influence of Surface Charge of Gold Nanorods on Skin Penetration. Skin Research and Technology 2013, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, F.; Allegretti, C.; Tessaro, D.; Carata, E.; Citti, C.; Vergaro, V.; Nobile, C.; Cannazza, G.; D’Arrigo, P.; Mele, A.; et al. Biocatalytic Synthesis of Phospholipids and Their Application as Coating Agents for CaCO3 Nano–Crystals: Characterization and Intracellular Localization Analysis. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 6507–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y.; Xiang, M.; Wu, F.; Sun, M.; Du, X.; Chen, L. Biocompatible Polyelectrolyte Complex Nanoparticles for Lycopene Encapsulation Attenuate Oxidative Stress-Induced Cell Damage. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 902208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | ζ-potential (mV)1 | Z-average (nm)2 | PdI3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyc@PLGA@PVA-NPs | -28.6±1.15 | 393.5±25.19 | 0.44±0.021 |

| Lyc@PLGA@Tween20-NPs | -43.6±1.47 | 177.6±8 | 0.4±0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).