1. Introduction

A nanoemulsion is a dispersed system in which droplets of one phase (usually oily) are dispersed in another phase (usually aqueous) and have an extremely small size, usually in the range of 10 to 300 nanometers. This nanometer size gives nanoemulsions unique physical and functional properties, such as high stability and high specific surface area. The nanometric size of nanoemulsions enables greater absorption of encapsulated compounds into the body due to the enhanced permeability of the cellular and tissue membranes [

1]. This is particularly beneficial for lipophilic or low-water-solubility compounds, such as certain vitamins and pharmaceuticals, as the nanoemulsion enhances their dispersion in aqueous solutions and facilitates their absorption into the body [

2]. Furthermore, the encapsulation of compounds in nanoemulsions affords protection from external factors such as oxidation, light and heat, which otherwise cause degradation. This is particularly crucial for compounds that are susceptible to degradation, such as antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and certain pharmaceuticals, which are preserved for an extended period under optimal conditions [

3]. Because of these properties, the popularity of nanoemulsions as encapsulation systems has gained a lot of attention in the last years, and they can used in a diverse range of applications, notably within the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and food industries [

4]

.

Flaxseed oil, also known as linseed oil and used in this study as dispersed phase, is obtained from the seeds of the flax plant (

Linum usitatissimum). It is recognized for its many nutritional properties and health benefits such as high levels of antioxidants, skin benefits and anti-inflammatory properties, among others [

5]. It is a rich source of essential fatty acids, particularly alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), a type of omega-3 that plays a key role in maintaining the integrity of the skin's lipid barrier. This facilitates the retention of moisture by the skin, resulting in a more even, hydrated and healthy appearance. The high omega-3 and antioxidant content of flax oil has been demonstrated to reduce inflammation and soothe the skin, which is beneficial for individuals with conditions such as acne, rosacea, eczema or psoriasis. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated to alleviate swelling and redness in individuals with sensitive or irritated skin [

6,

7].

In contrast to chemical sunscreens, which absorb UV rays and convert them into heat, zinc oxide functions as a physical blocker or mineral filter. This results in the formation of a layer on the surface of the skin that reflects and scatters UV radiation, thereby preventing its penetration into the skin [

8]. This makes it an appropriate choice for individuals with sensitive skin, as it is less prone to causing irritation or allergic [

9]. Furthermore, it is one of the few approved ingredients that provides protection against both UVB rays and UVA rays. In addition to its photoprotective effects, zinc oxide has been demonstrated to possess soothing and anti-inflammatory properties, rendering it a beneficial agent for individuals with skin prone to irritation. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated to alleviate redness and inflammation, which is beneficial in the aftermath of sun exposure [

10,

11].

In order to stabilise nanoemulsions, a surfactant is needed. Appyclean 6552 is a non-ionic surfactant comprising amyl, capryl, and lauryl xylosides derived from wheat. The plant origin of this surfactant ensures its safety, as it is biodegradable and has a low toxicity to the environment (OECD 301F and OECD 311). It has been used before stabilising nanoemulsions and protecting active ingredients from heat and sun [

12,

13]. In this study, a thickener (Aerosil® COK84) is incorporated into the nanoemulsions to form the cream texture and increase viscosity. Aerosil®COK 84 is a combination of the fumed silica Aerosil®200 and highly dispersed aluminum oxide (AEROXIDE®Alu C) in a 5:1 ratio. It possesses spherical particles in the nanoscale range and it is considered as a thickening and gelling agent [

14]. In addition, it has applications in paintings, pharmaceutical, cosmetic and food industry [

15,

16,

17,

18].

The present study systematically designs and characterises a bio-based linseed-oil nanoemulsion co-stabilised by ZnO nanoparticles and the biodegradable surfactant Aerosil 6552, and subsequently reinforced with fumed silica/alumina. Following a detailed discussion of the materials and preparation protocol, a response-surface methodology is employed to identify the optimal oil/ZnO ratio. This is then followed by an examination of how incremental amounts of Aerosil can be used to tailor the formulation's droplet size distribution, rheology, physical stability and in-vitro SPF. The work elucidates the multiscale mechanism through which ZnO and Aerosil confer synergistic Pickering and network structuring effects by integrating complementary techniques. These techniques include laser diffraction, multiple light scattering, oscillatory rheometry, UV spectrophotometry and FE-SEM. The findings provide both a mechanistic framework and practical guidelines for formulating greener, highly stable sunscreens, thereby bridging the fundamental colloidal principles outlined above with the applied results discussed in the following sections.

3. Results and Discussion

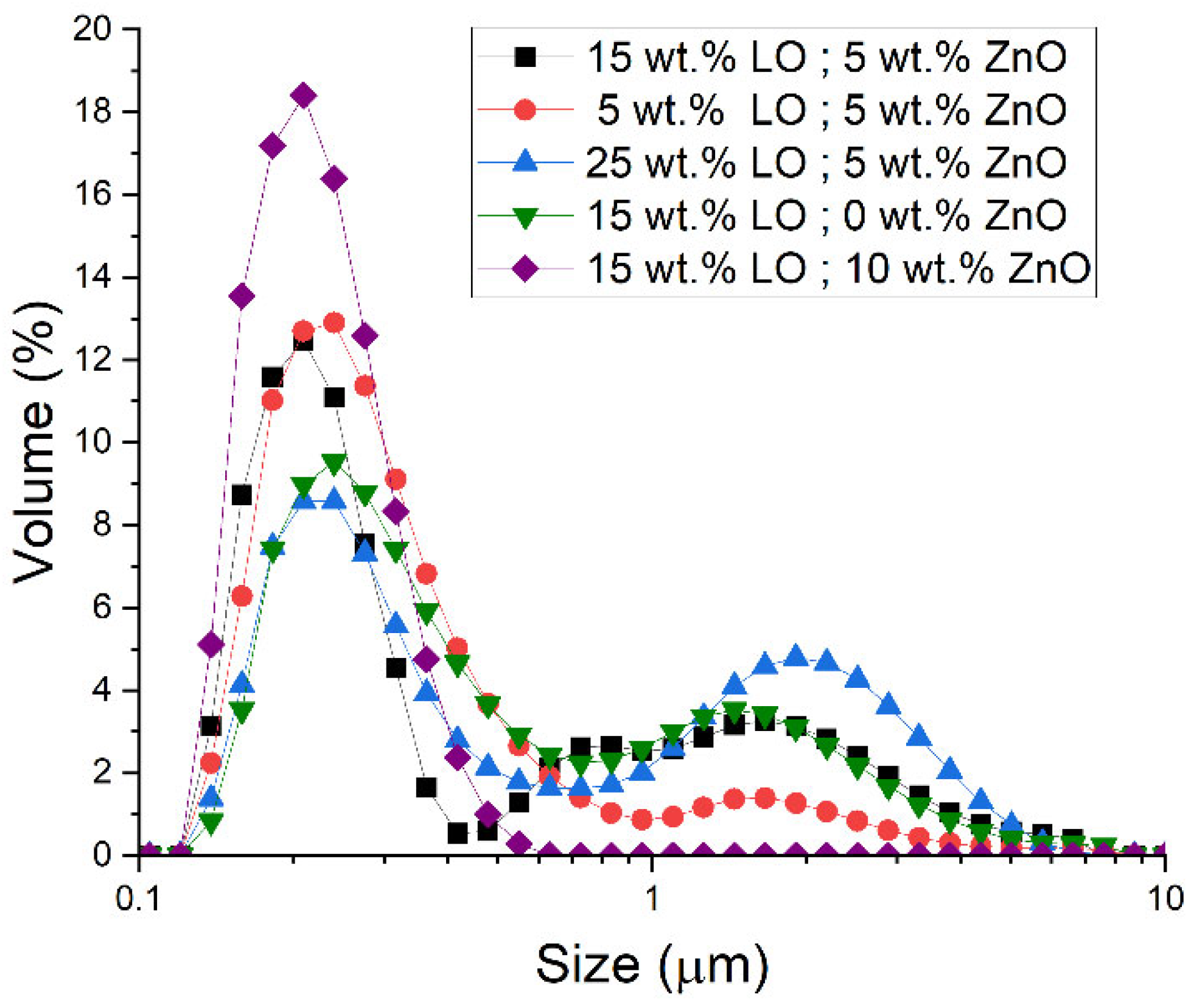

Figure 1 compares the droplet size distributions of linseed oil nanoemulsions formulated with varying linseed oil and ZnO nanoparticle concentrations. All samples exhibited nanometric droplet sizes; however, it was possible to discern clear trends in the distribution shape and location as a function of composition. It is noteworthy that increasing the linseed oil content results in a shift in the droplet size distribution toward larger diameters and frequently broadens the distribution. For instance, the formulation with the highest oil fraction displays a prominent tail of larger droplets in

Figure 1, suggesting the presence of microscale droplets. Conversely, nanoemulsions with reduced oil content yield a more constrained, monomodal distribution, with a concentration of smaller droplets and an absence of substantial, large-droplet tails. Quantitatively, the Sauter mean diameter D

3,2 demonstrates a marked increase with oil concentration: D

3,2 increases from approximately 261 nanometers at the lowest oil loading to around 370 nanometers at the highest (see

Table 2). This phenomenon can be attributed to the process of agglomeration, wherein larger average droplets are formed when a greater quantity of linseed oil is dispersed, while maintaining a constant ZnO level and energy input. This phenomenon aligns with the principles of emulsion theory and corroborates the findings of previous studies. Specifically, an elevated dispersed-phase fraction tends to generate larger droplets and more extensive size distributions, provided that the surfactant concentration or homogenization energy remains proportionately constant [

23]. The presence of larger droplets at elevated oil levels can be ascribed to inadequate emulsifier coverage, which leads to increased coalescence during the emulsification process. This phenomenon results in a diminished total interfacial area and consequently a heightened D

3,2. In essence, as the linseed oil fraction increases, the emulsification process is unable to maintain the same fine droplet size, resulting in a systematic upward shift in the mean droplet diameter.

Conversely, an increase in the concentration of ZnO nanoparticles results in a decrease in droplet size. Higher loadings of ZnO have been found to be associated with smaller droplet diameters and narrower size distributions in the nanoemulsions. As illustrated in

Figure 1, formulations containing ZnO exhibit a slight shift in their droplet size distributions toward the left, indicating smaller droplet sizes. Additionally, these formulations demonstrate a more pronounced distribution compared to their ZnO-free counterparts. For instance, at a given intermediate oil concentration, the addition of ZnO (at 10 wt.%) has been shown to reduce the peak droplet size and suppress the population of large droplets observable in the tail of the distribution. Consequently, D

3,2 decreases with increasing ZnO content. For instance, a nanoemulsion containing ZnO (e.g., 5 wt.%) demonstrates a mean droplet size that is smaller than a comparable formulation devoid of ZnO (see

Table 2). A modest incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles has been demonstrated to yield a more uniform and finer dispersion of oil droplets, suggesting a potential for enhanced oil dispersion properties. This outcome can be explained by the role of ZnO nanoparticles at the oil–water interface. The ZnO particles likely function as Pickering co-stabilizers, adsorbing at droplet interfaces alongside the surfactant and impeding droplet coalescence. In essence, the nanoparticles provide supplementary steric and/or electrostatic barriers surrounding the droplets, thereby facilitating the formation and stabilization of smaller droplets. As indicated by the extant literature, analogous reductions in droplet size with solid particle additives have been reported in Pickering emulsions. For instance, the addition of sufficient colloidal stabilizers (e.g., cellulose nanofibers or silica) has been shown to yield smaller D

3,2 values by preventing coalescence and effectively increasing the allowable interfacial area [

24,

25]. It is noteworthy that in the present system, the ZnO nanoparticles were dispersed in the continuous phase prior to emulsification, ensuring their rapid availability to anchor at newly formed oil–water interfaces. This phenomenon likely contributes to the observed decrease in mean droplet size and the tightening of the size distribution with higher ZnO concentration.

From a scientific and practical perspective, these findings underscore the necessity of achieving an optimal balance in formulation. An elevated oil fraction, if not offset by an adequate amount of surfactant or stabilizer, will result in the production of larger, less uniform droplets. This, in turn, has the potential to compromise the stability of the nanoemulsion. Indeed, larger droplets possess a reduced total surface area and have been shown to accelerate destabilization phenomena such as creaming or coalescence. In contrast, the incorporation of solid nanoparticles, such as ZnO, has been shown to enhance emulsification efficiency and stability through the establishment of a Pickering stabilization effect. This results in the formation of smaller droplets that exhibit greater resistance to coalescence. This outcome is favorable for application goals such as UV-blocking finishes, as smaller droplets and uniform distributions generally result in more stable and transparent formulations. In summary, the droplet size analysis demonstrates a clear correlation with formulation composition: larger oil fractions yield larger average droplets, while higher ZnO nanoparticle concentrations promote smaller and more uniform droplets. The findings, both qualitative and quantitative, demonstrate the efficacy of manipulating the oil-to-surfactant ratio and incorporating inorganic nanoparticles to regulate the size of nanoemulsion droplets (see

Figure 1 and

Table 2).

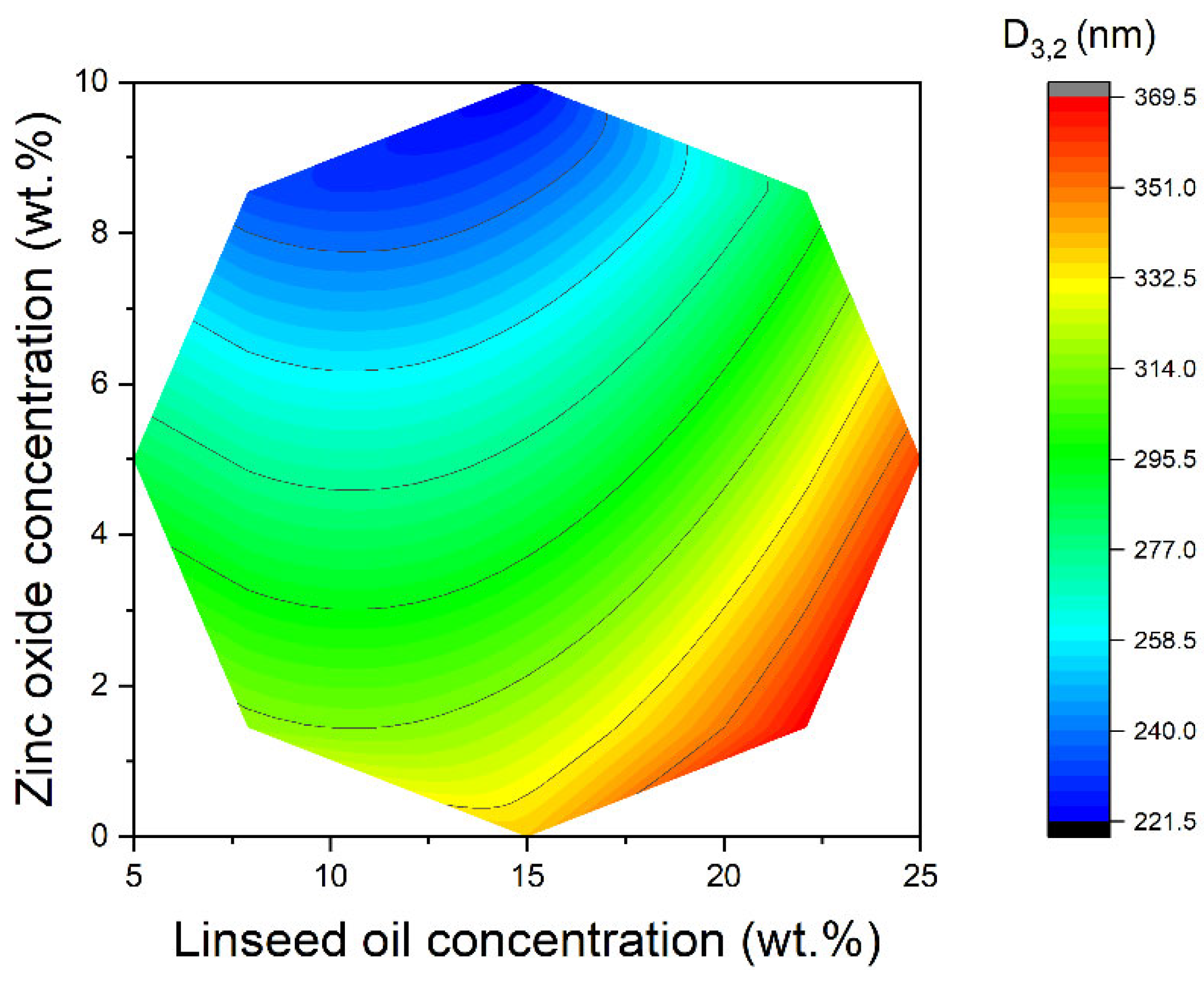

A thorough analysis of the results obtained and presented in

Table 2, employing the response surface methodology enables the formulation of an equation (R

2 = 0.91) that establishes a correlation between D

3,2 and the concentrations of linseed oil (LO) and zinc oxide (ZnO):

Figure 2 shows the curved, quadratic 2D response surface of the Sauter mean droplet diameter in relation to the concentrations of linseed oil (LO) and zinc oxide (ZnO). The pronounced curvature of the surface indicates that second-order effects are significant and that the relationship is not simply linear. Notably, zinc oxide concentration exerts the largest influence on D₃,₂. Within the explored design window, D₃,₂ decreased monotonically with rising ZnO concentration, and the smallest droplets were obtained at the highest ZnO level tested. No evidence of a plateau or rebound was detected, underscoring that ZnO concentration is the dominant factor governing droplet size in this system, while the LO · ZnO interaction term did not reach statistical significance. A curvature is observed along the LO axis. D

3,2 increases sharply at high oil loadings due to insufficient stabiliser coverage, but does not drop indefinitely at the lowest LO. Therefore, the response surface trends indicate that moderate oil amounts and the highest concentration of ZnO produce the smallest droplets, whereas excess oil or the absence of ZnO leads to larger D

3,2 values. According to the quadratic surface model (Equation 3) and

Figure 2, there is a clear optimum region in which the Sauter mean diameter is at its smallest. This optimal point corresponds to Sample 8 in

Table 1, which had the smallest D

3,2 value of all the formulations tested. Sample 8's formulation lies at an intermediate LO concentration and a relatively high ZnO concentration within the design space. In practical terms, this means that using a moderate amount of linseed oil combined with a high level of ZnO nanoparticles produces the finest droplet size. The model predicts a unique minimum rather than a ridge or plateau, indicating that this combination of linseed oil (LO) and zinc oxide (ZnO) is truly optimal for minimizing droplet diameter. Identifying the optimal region for droplet size has important implications for nanoemulsion formulation and stability. Emulsions with a smaller D₃,₂ have slower creaming rates and a lower likelihood of coalescence because the fine droplets have weaker buoyancy (according to Stokes' law) and are more uniformly stabilized.

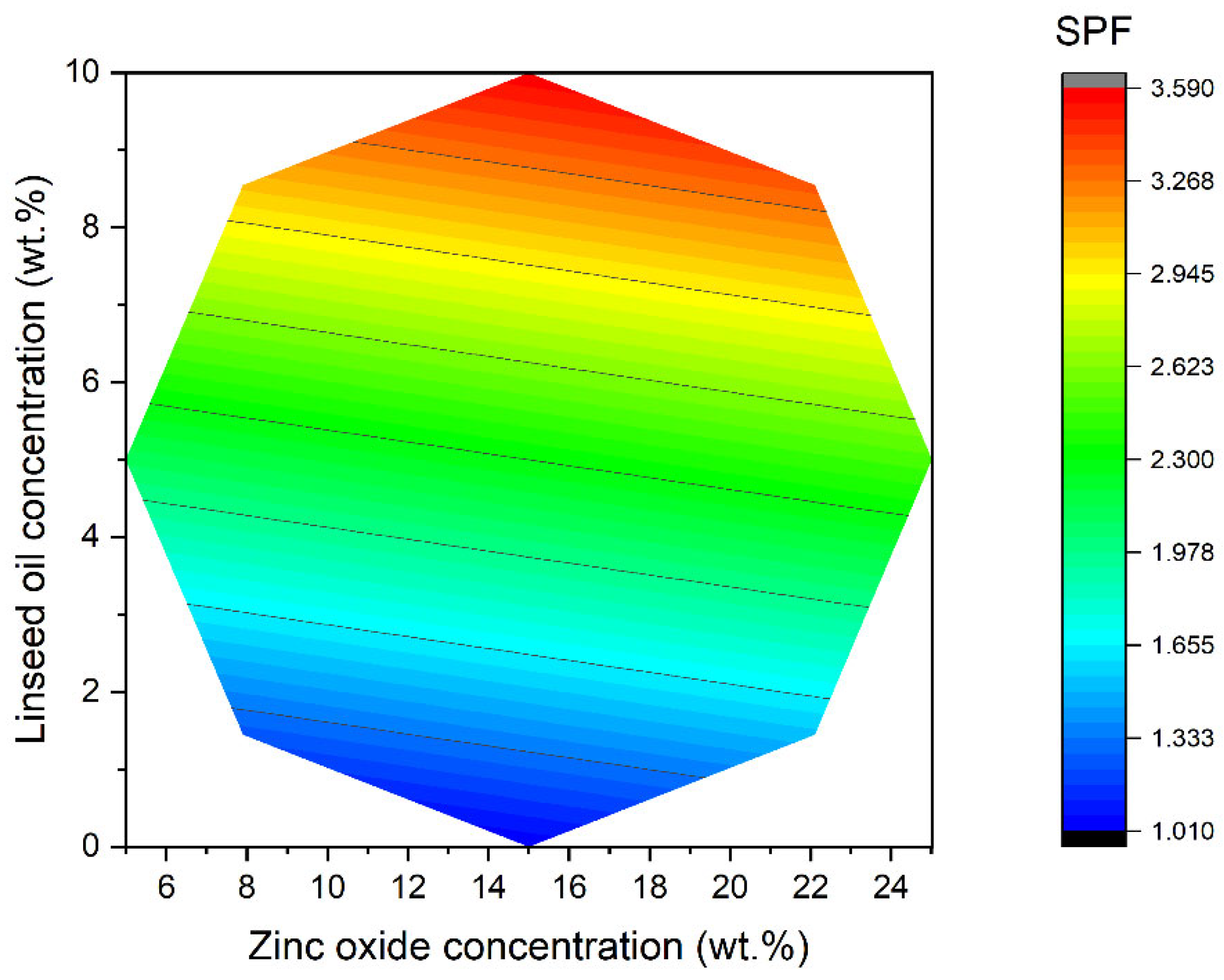

The analysis of the results obtained for the Sun Protection Factor (SPF), calculated using Mansur's equation, yielded an equation (R

2=0.92) relating this parameter to the concentrations of linseed oil (LO) and zinc oxide (ZnO):

As demonstrated in

Table 2, within the compositional window that was explored, the in-vitro Sun Protection Factor (SPF) ranges from 0.39 to 3.51. The lowest value recorded (sample 7, LO 15 wt.%, 0 wt.% ZnO) indicates that linseed oil, when applied in isolation, provides only marginal UV screening, consistent with the extant literature which attributes an SPF < 2.0 to most plant oils. Conversely, the introduction of zinc oxide has been demonstrated to raise the SPF in every case; at the same LO level (15 wt.%), the transition from 0 to 5 to 10 wt.% ZnO elevates SPF from 0.39 (sample 7) to 2.34/2.37 (samples 9–10) and finally to 3.51 (sample 8). These increments are consistent with the well-established primary role of micron- or nano-sized ZnO as a broadband physical filter, the efficacy of which is approximately proportional to the volume fraction of particles. Nonetheless, the absolute SPF values remain below those of commercial ZnO creams (typically SPF 15–30 for ≥15 wt.% ZnO), presumably due to the fact that the studied samples are a much simpler formulation [

26]. Equation 3 captures these trends with a linear main-effect term for ZnO and a smaller but positive coefficient for LO. The greater magnitude of the ZnO coefficient quantitatively confirms that SPF depends much more strongly on ZnO loading than on the oil phase itself. From a chemical perspective, this outcome is anticipated. ZnO has been demonstrated to attenuate UVA/UVB via two mechanisms: firstly, via scattering, and secondly, via band-gap absorption [

27]. In contrast, LO supplies trace phenolics that absorb weakly in the UVB region. As demonstrated in

Figure 3, the fitted surface is characterised by is contours that are almost parallel to the LO axis, but exhibit a steepening gradient with respect to ZnO, thereby underscoring its predominant role. It is evident that a shallow optimum (SPF = 3.5) emerges at an LO of 15 wt.% and a ZnO of 10 wt.%, coinciding with experimental point 8. This is analogous to the optimum for Sauter mean diameter.

The physical stability of the optimal emulsion, formulated with 15 wt.% linseed oil and 10 wt.% zinc oxide, was monitored by multiple light scattering to determine and quantify possible destabilization mechanisms. After seven days, an increase in backscattering was observed in the lower part of the vial, indicating a destabilization mechanism due to the sedimentation of zinc oxide particles. This sedimentation process may be due to the high density of zinc oxide particles compared to the rest of the system and the low viscosity of the emulsion. However, the system showed no signs of destabilization through creaming or coalescence. Thus, the Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI) value for this system was 4.2 ± 0.4 after seven days of ageing. In order to enhance physical stability, modulate rheological properties and augment SPF, Aerosil COK 84 was incorporated into the formulation. Two distinct concentrations were evaluated and compared with the previous optimum (0 wt.% Aerosil COK 84).

The addition of fumed silica/alumina nanoparticle to linseed oil-in-water nanoemulsions containing ZnO has been shown to have a significant effect on the properties of the resultant emulsions. Specifically, an increase in silica concentration has been demonstrated to result in a transformation of rheological and viscoelastic behaviour, alterations to microstructure, and enhancements in physical stability and UV protection performance. These effects are attributed to the ability of Aerosil to establish a particle network within the continuous phase, thereby complementing the roles of oil and ZnO in the formulation.

The rheological parameters presented in

Table 3 demonstrate a distinct, concentration-dependent transition from a nearly Newtonian emulsion to a highly structured, shear-thinning gel. In the absence of Aerosil COK 84, the consistency index k is recorded as 0.019 Pa · sⁿ and the flow index n is 0.90, suggesting a low-viscosity liquid whose shear stress is nearly proportional to the shear rate. The introduction of 1 wt% Aerosil results in a substantial increase in k, raising it by more than an order of magnitude to 0.334 Pa · sⁿ. Concurrently, n is reduced to 0.27, indicating the initiation of a three-dimensional particulate network that contributes to yield behaviour and pronounced pseudoplasticity. It is evident that at 2 wt% Aerosil, the network is fully developed, as evidenced by the increase in k to 3.50 Pa·sⁿ, concomitant with the decrease in n to 0.14. It is evident that the incorporation of varying quantities of Aerosil COK 84 results in significant alterations to the flow behaviour of the nanoemulsions. As demonstrated in

Figure 4 and

Table 3, an increase in silica levels has been observed to result in elevated viscosity and shear-thinning behavior in emulsions. Even at low shear rates, formulations with high Aerosil content exhibit significantly increased apparent viscosity (often by orders of magnitude) compared to silica-free emulsions. This phenomenon is indicative of the formation of a shear-thinning fluid. This behaviour is indicative of fumed silica dispersions, wherein a three-dimensional network of silica aggregates accumulates at rest and disintegrates under flow. The network is formed from hydrogen bonds and van der Waals attractions between silica particles (and alumina sites), which create a transient gel-like structure in the aqueous continuous phase. Consequently, nanoemulsions with elevated Aerosil concentrations exhibit resistance to flow until a critical shear (yield stress) is attained, at which point they undergo facile flow. This rheology is highly beneficial for product stability and application: the formulation remains thick and prevents phase separation during storage, yet it can be spread easily when rubbed.

The oscillatory rheology (

Figure 5) further highlights the structural changes induced by Aerosil COK 84. As the silica concentration increases, the nanoemulsion undergoes a transition from a predominantly viscous liquid to a more elastic, solid-like material. It has been demonstrated that with the addition of Aerosil, G′ undergoes a substantial increase that can surpass G″ across a spectrum of frequencies. This phenomenon is indicative of the development of a weak gel structure, characterized by predominant elasticity. The network of silica particles endows the system with the capacity to store elastic energy: under small deformations, the structure resists and recoils (high G′), rather than flowing irreversibly. The emergence of a frequency-independent plateau in G′ at low frequencies for the samples formulated with the fumed silica (as illustrated in

Figure 5) is indicative of a percolated network or gel within the sample. Consequently, the loss tangent (G″/G′) decreases with silica content, indicating a transition towards solid-like behavior. These viscoelastic trends are consistent with a particle-bridged droplet network in the emulsions. In this study, it is hypothesized that Aerosil particles in the continuous phase connect via weak bonds and possibly anchor to droplet interfaces, creating an elastic cage that traps the oil droplets. This finding is consistent with reports that the incorporation of colloidal silica into emulsions results in a substantial augmentation of the yield stress and plateau modulus when compared to formulations devoid of silica. It can thus be concluded that Aerosil functions as a structuring agent, thereby converting a purely viscous emulsion into a viscoelastic gel. In contrast, the combination of ZnO and oil alone did not yield the robust gel-like moduli that were observed with silica. It is evident that the supplementation of Aerosil is pivotal in the customization of the linear viscoelastic response.

The physical stability of the nanoemulsions, quantified by the Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI) in

Table 3, improves markedly with increasing Aerosil content. Conversely, a lower TSI is indicative of reduced phase separation or creaming over time. The data demonstrate that samples devoid of Aerosil exhibit elevated TSI values, indicative of diminished stability. Conversely, samples incorporating Aerosil demonstrate reduced TSI values, suggesting enhanced stability. This enhancement can be directly attributed to the rheological and microstructural effects discussed above. In essence, the arrest of the mobility of droplets and solid particles is induced by silica. Droplet creaming and sedimentation are greatly suppressed because the gel character can counteract the gravitational force on the dispersed particles.

The progressive enrichment of the optimised linseed-oil/ZnO nanoemulsion with Aerosil COK 84 resulted in a measurable enhancement of its photo-protective performance. As demonstrated in

Table 3, the in-vitro SPF exhibited an increase with the incorporation of Aerosil, with statistical significance attained at p < 0.05. Despite the fact that the absolute gains are modest in comparison to the increase achieved by ZnO itself, they are noteworthy for two reasons. Firstly, the rise occurs without altering either the active ZnO dose or the oil/surfactant ratio, evidencing a genuine synergistic contribution from the fumed silica/alumina particles. Secondly, the incremental SPF is accompanied by markedly lower TSI values and a rheology shift from a nearly Newtonian fluid to a weak-gel network. Collectively, these factors delay sedimentation of ZnO and immobilise droplets, thereby preserving the optical homogeneity that is essential for reproducible UV screening.

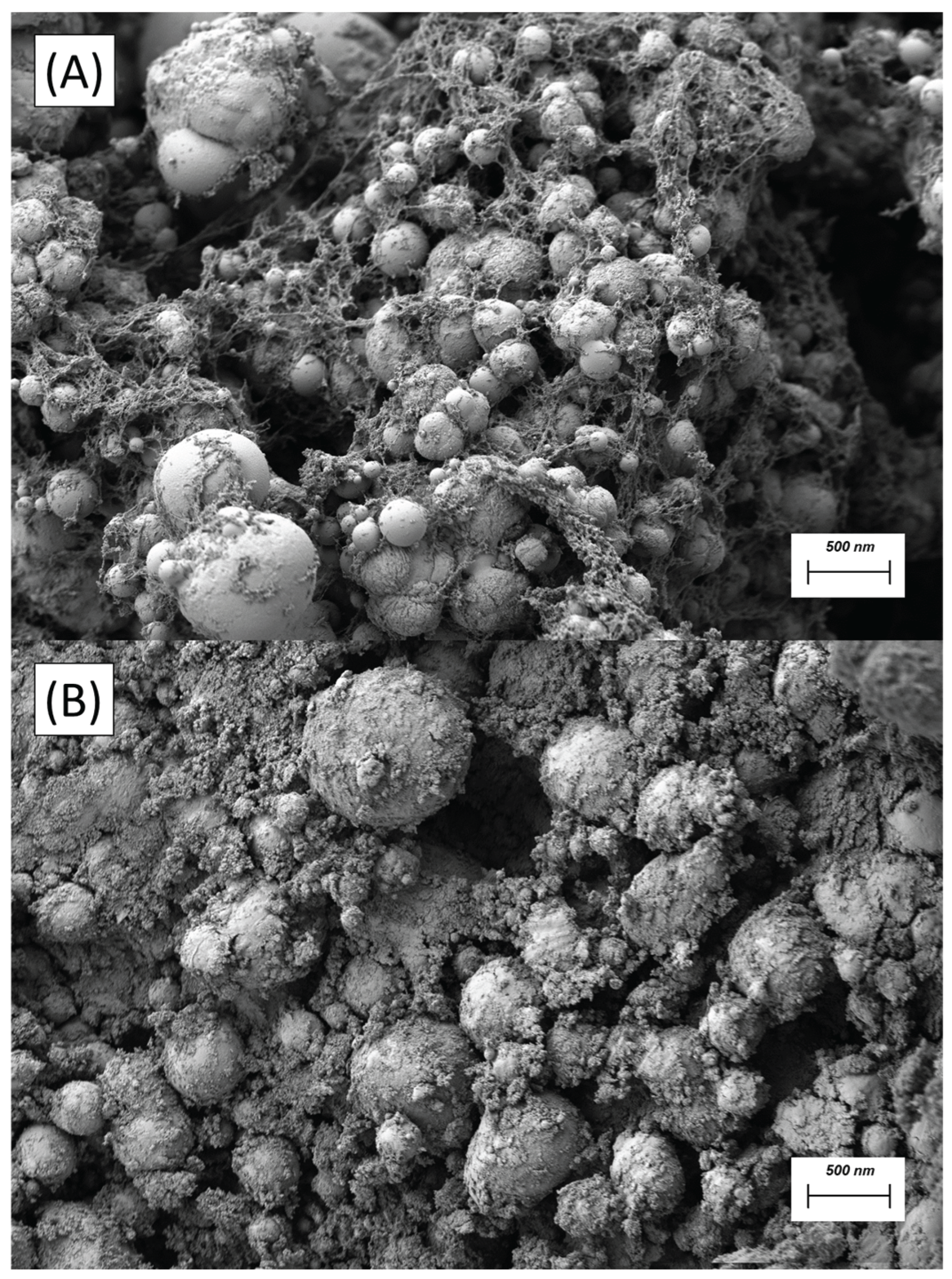

Figure 6 provides a direct microstructural comparison between the silica-free nanoemulsion (6A) and its counterpart enriched with 1 wt.% Aerosil COK 84 (6B). In micrograph 6A, the oil droplets are distinctly delineated by a thin, continuous corona of adsorbed ZnO nanoparticles, giving rise to a classic Pickering shell. The individual droplets remain largely isolated, and the inter-droplet spaces appear dark and unfilled, indicating that the particle layer is confined to the oil/water interface. The configuration under discussion stabilizes the dispersion against coalescence. However, the absence of an interconnecting particle scaffold leaves significant voids through which droplets may still migrate under gravity or applied shear. The addition of fumed silica/alumina (6B) transforms this discrete architecture into a densely interconnected network. While ZnO continues to armor each droplet, Aerosil aggregates are now observed to be bridging neighboring interfaces and populating the continuous phase, thereby producing a space-filling, fractal-like skeleton. Such a percolated silica framework immobilizes both droplets and ZnO particles, thereby accounting for the pronounced rise in low-frequency elasticity, the order-of-magnitude jump in consistency index, and the halving of the Turbiscan Stability Index reported elsewhere in the manuscript.

When considered collectively, micrographs 6A and 6B provide confirmation of a two-level Pickering mechanism. At the primary level, ZnO exhibits a tendency to adhere to the oil–water interface, a property that functions to reduce interfacial tension and sterically impede droplet coalescence. In the secondary level, Aerosil aggregates are distributed across the continuous phase, forming interconnected networks with ZnO-coated droplets to produce a cohesive, load-bearing gel. This gel functions to impede both sedimentation and creaming, thereby ensuring the stability and integrity of the system.