Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Review Approach

Literature Search Strategy

Inclusion Criteria

Exclusion Criteria

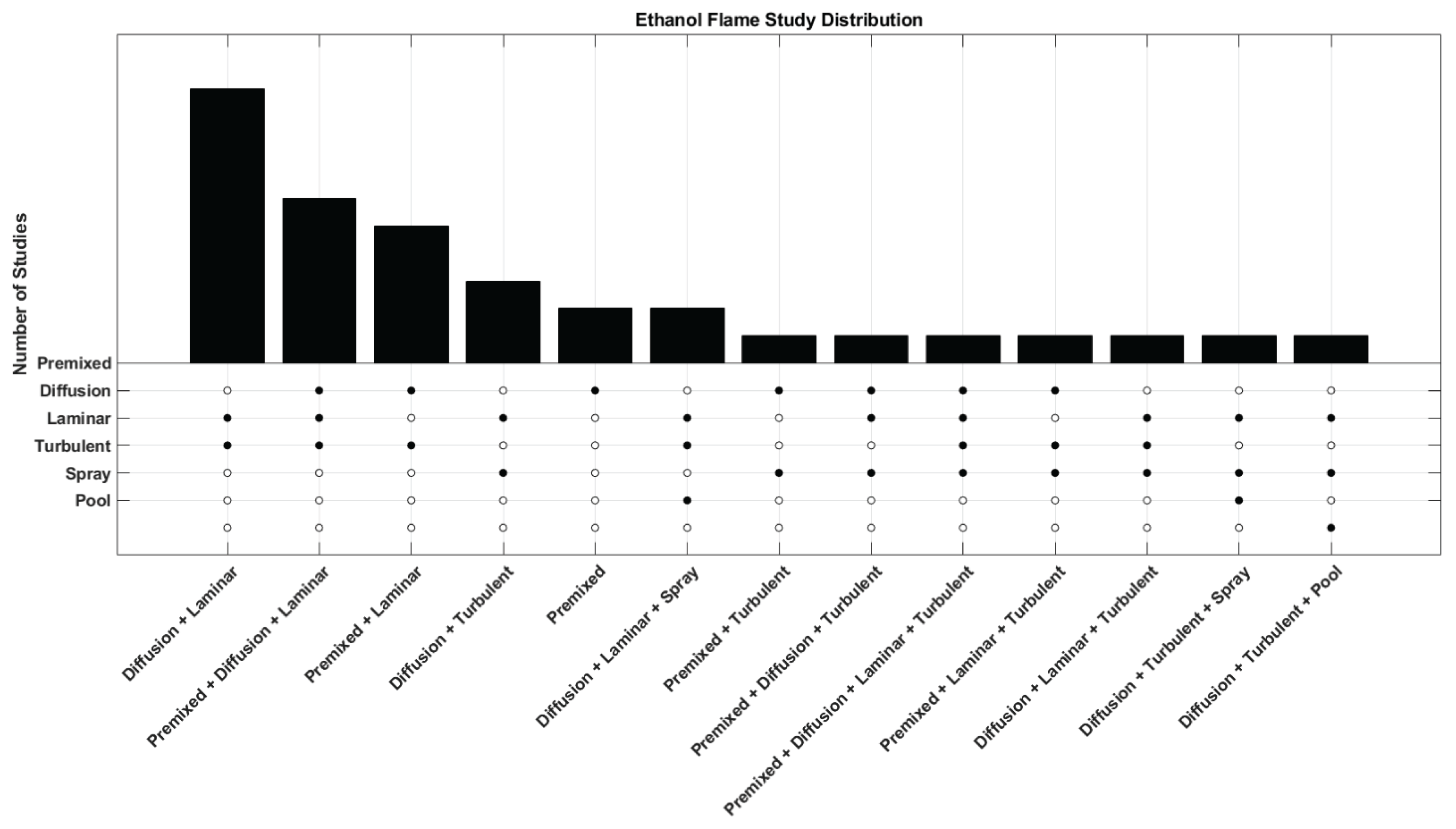

Results

Inventory of Mechanisms

Discussion

Mechanism Diversity and Reduction Techniques

Trade-Offs: Size, Fidelity, and Applicability

Validation in Turbulent and Pool Flames

Gaps and Limitations in Current Literature

Toward Improved Biofuel Combustion Modeling

Concluding Remarks

References

- E. E. A. European Climate, "Renewables 2023: Analysis and forecast to 2028," International Energy Agency, Paris, 2024.

- M. Z. Jacobson, "Roadmaps to Transition Countries to 100% Clean, Renewable Energy for All Purposes to Curtail Global Warming, Air Pollution, and Energy Risk," Earth's Future, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 948-952, October 2017. October. [CrossRef]

- A. Yontar, "Methanol, isobutanol, kerosene, dimethylfuran, ethanol, and isopropanol additives effects on soot concentration at hydrogen-enriched methane flames," Biofuels, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 793–804, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Saggi and P. Dey, "An overview of simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of starchy and lignocellulosic biomass for bio-ethanol production," Bifuels, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 287–299, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Thakur and A. K. Kaviti, "Progress in regulated emissions of ethanol-gasoline blends from a spark ignition engine," Biofuels, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 197–220, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tizvir, M. H. Shojaeefard, G. R. Molaeimanesh, A. Zahedi and B. Kanani, "Sustainable production and application of microalgae-based biodiesel using a renewable hybrid energy system: enhancing emission reduction and engine performance in cold start conditions for greener transportation," Biofuels, 2025.

- S. K. Tulashie, C. A. Osei, R. Kwofie, M. O. Olorunyomi, H. Attagba, O. O. Boateng, R. Adade and P. Mattah, "The potential production of biofuel from Sargassum sp.: turning the waste catastrophe into an opportunity," Biofuels, vol. 15, no. 7, p. 849–863, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, A. K. Cowan, Z. Deng, I. A. Phulphoto, A. Jalil, B. Wang and Z. Yu, "Exploring potential synergies in the integration of anaerobic co-digestion with dark fermentation or microbial electrolysis to enhance methane output," Biofuels, 2025.

- S. C. Trindade, L. A. H. Nogueira and G. M. Souza, "Relevance of LACAf biofuels for global sustainability," Biofuels, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 279-289, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Etghani and H. Mirgolbabaei, "Smart choice transesterification-base-produced biodiesels and their performance characteristics in diesel engine," Biofuels, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 1119-1136, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Naik, V. V. Goud, P. K. Rout and A. K. Dalai, "Production of first and second generation biofuels: A comprehensive review," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 578-597, February 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Iodice, A. Amoresano and G. Langella, "A review on the effects of ethanol/gasoline fuel blends on NOX emissions in spark-ignition," Biofuel Research Journal, vol. 32, pp. 1465-1480, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Gajewski, S. Wyrabkiewicz and J. Kaszkowiak, "Effects of Ethanol–Gasoline Blends on the Performance and Emissions of a Vehicle Spark-Ignition Engine," Energies, vol. 18, no. 3, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Jamuwa, D. Sharma and S. L. Soni, "Performance, emission and combustion analysis of an ethanol fuelled stationary CI engine," Biofuels, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 569-582, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Igwebuike, S. Awad and Y. Andrès, "Bioethanol production from dilute acid hydrolysis of cassava peels, sugar beet pulp, and green macroalgae (Ulva lactuca)," Biofuels, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 1145–1157, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A. V. Babu, B. Balaji and P. S. Ranjit, "Experimental investigation of NOx emission control using carbon nanotube additives and EGR configuration on CRDI engine fueled with ternary fuel," Biofuels, vol. 15, no. 10, p. 1315–1329, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Deepak and M. Mohamed Ibrahim, "A critical review on emulsion fuel formulation and its applicability in compression ignition engine," Biofuels, vol. 15, no. 5, p. 555–573, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Eslami, B. Hosseinzadeh Samani, S. Rostami, R. Ebrahimi and A. Shirneshan, "Investigating and optimizing the mixture of hydrogen-biodiesel and nano-additive on emissions of the engine equipped with exhaust gas recirculation," Biofuels, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 473–484, 2023. [CrossRef]

- U. Paneerselvam and K. Ganapathy, "Effect of hydrogen induction on CI engine characteristics fuelled with kapok oil methyl ester-turpentine blend with diethyl ether.," Biofuels, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 389-405, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Bikkavolu, S. Vadapalli, K. R. R. Chebattina and G. Pullagura, "Effects of stably dispersed carbon nanotube additives in yellow oleander methyl ester-diesel blend on the performance, combustion, and emission characteristics of a CI engine," Biofuels, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 67–80, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, Y. Wang and D. Liu, "Effects of oxygenated biofuel additives on soot formation: A comprehensive review of laboratory-scale studies," Fuel, vol. 313, pp. 1873-7153, April 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, J. Hu, D. Zhang, G. Jia, B. Zhang, S. Wang, W. Zhong, Z. Zhao and J. Zhang, "Overview of the impact of oxygenated biofuel additives on soot emissions in laboratory scale," Fuel Processing Technology, vol. 254, February 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Lay, N. Tang, V. Arangaswamy, I. Ibrahim and M. Liu, "Role of neat biodiesel as pilot fuel in dual-fuel combustion for maritime decarbonization," Biofuels, 2025.

- C.-G. Liu, Y. Xiao, X.-X. Xia, X.-Q. Zhao, L. Peng, P. Srinophakun and F.-W. Bai, "Cellulosic ethanol production: Progress, challenges and strategies for solutions," Biotechnology Advances, vol. 37, pp. 491-504, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shiva, F. C. Barba, R. M. Rodriguez-Jasso, R. K. Sukumaran and H. A. Ruiz, "High-solids loading processing for an integrated lignocellulosic biorefinery: Effects of transport phenomena and rheology – A review," Bioresource Technology, vol. 351, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Kim, o.-C. Park, Y.-S. Jin and J.-H. Seo, ""Bioenergy and Biorefinery from Biomass" through innovative technology development," Biotechnology Advances, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 851-861, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Liu and J. Bao, "High solids loading pretreatment: The core of lignocellulose biorefinery as an industrial technology – An overview," Bioresource Technology, vol. 369, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Warnatz, U. Maas and R. W. Dibble, Combustion: Physical and Chemical Fundamentals, Modeling and Simulation, Experiments, Pollutant Formation, 4th ed., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2006.

- U. Burke, W. K. Metcalfe, S. M. Burke, K. A. Heufer, P. Dagaut and H. J. Curran, "A detailed chemical kinetic modeling, ignition delay time and jet-stirred reactor study of methanol oxidation," Combustion and Flame, vol. 156, pp. 125-136, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Frassoldati, A. Cuoci, T. faravelli and E. Ranzi, "Kinetic Modeling of the Oxidation of Ethanol and Gasoline Surrogate Mixtures," Combustion Science and Technology, vol. 182, pp. 653-667, 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. Poinsot and D. Veynante, Theoretical and Numerical Combustion, 3rd ed., Edwards, 2005.

- N. M. Marinov, "A Detailed Chemical Kinetic Model for High Temperature Ethanol Oxidation," International Journal of Chemical Kinetics, vol. 31, pp. 183-220, 1999. [CrossRef]

- T. Lu and C. K. Law, "A directed relation graph method for mechanism reduction," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 30, pp. 1333-1341, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Lu and C. K. Law, "Toward accommodating realistic fuel chemistry in large-scale computations," Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 192-215, April 2009. [CrossRef]

- B. Ray and H. Mirgolbabaei, "Low-Manifold Biofuel Fast Combustion Simulation," in Proceedings of the Summer Heat Transfer Conference (SHTC2025), Westminster, CO, 2025.

- T. Echekki and H. Mirgolbabaei, "Principal component transport in turbulent combustion: A posteriori analysis," Combustion and Flame, vol. 162, no. 5, pp. 1919-1933, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "The reconstruction of thermo-chemical scalars in combustion from a reduced set of their principal components," Combustion and Flame, vol. 162, no. 5, pp. 1650-1652, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Patton, T. Wignall, H. Mirgolbabaei, J. R. Edwards and T. Echekki, "LES Model Assessment for High Speed Combustion using Mesh-Sequenced Realizations," in 51st AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Orlando, FL, 2015.

- H. Mirgolbabaei, C. Patton, T. Wignall, J. R. Edwards and T. Echekki, "4D data assimilation for large eddy simulation of high speed turbulent combustion," in 51st AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, Orlando, FL, 2015.

- T. Echekki and H. Mirgolbabaei, "Principal Component Transport in Turbulent Combustion," in APS Division of Fluid Dynamics Meeting, San Francisco, CA, 2014.

- H. Mirgolbabaei, T. EChekki and N. Smaoui, "A nonlinear principal component analysis approach for turbulent combustion composition space," International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 4622-4633, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Mirgolbabaei, Low-dimensional manifold simulation of turbulent reacting flows using linear and nonlinear principal components analysis, Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University, 2014.

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "Nonlinear reduction of combustion composition space with kernel principal component analysis," Nonlinear reduction of combustion composition space with kernel principal component analysis, vol. 161, no. 1, pp. 118-126, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "A Moments-Based Method for Turbulent Combustion Based on Principal Components: A priori and a posteriori validation," in 66th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics, Pittsburgh, PA, 2013.

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "A novel principal component analysis-based acceleration scheme for LES–ODT: An a priori study," Combustion and Flame, vol. 160, no. 5, pp. 898-908, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "Nonlinear Principal Component Analysis for Combustion Large-Eddy Simulation," in 65th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics, San Diego, CA, 2012.

- H. Mirgolbabaei and T. Echekki, "Data-Based Optimum Strategies for Combustion Large-Eddy Simulation," in 64th Annual Meeting of the APS Division of Fluid Dynamics, Baltimore, MD, 2011.

- H. Mirgolbabaei, R. Muller and H. Honari, "REDUCED LARGE EDDY FLAME SIMULATION, DIMENSIONAL SURROGATE APPROACH," in 10th Thermal and Fluids Engineering Conference (TFEC), Washington D.C., 2025.

- S. Turns and D. C. Haworth, An Introduction to Combustion: Concepts and Applications, 4th ed., McGraw Hill, 2021.

- A. Griffin, M. Christensen and Ö. L. Gülder, "Effect of ethanol addition on soot formation in laminar methane diffusion flames at pressures above atmospheric," Combustion and Flame, vol. 193, pp. 306-312, July 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Roy, R. Mishra, O. Askari and D. Jarrahbashi, "Reduced ethanol skeleton mechanism for multi-dimensional engine simulation," Journal of the Energy Institute, vol. 106, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Levac, H. Colquhoun and K. K. O'Brien, "Scoping studies: advancing the methodology," Implementation Science, vol. 5, no. 69, 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Tricco, E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O'Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, M. D. Peters, T. Horsley, L. Weeks, S. Hempel, E. A. Akl, C. Chang, J. McGowan, L. Stewart, L. Hartling and M. G. Wilson, "PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation," Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 169, no. 7, pp. 467-473, 2018. [CrossRef]

- "PRISMA," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping#:~:text=The%20PRISMA%20extension%20for%20scoping,of%20the%20literature%20is%20warranted.

- P. Saxena and F. A. Williams, "Numerical and experimental studies of ethanol flames," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 31, p. 1149–1156, 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. K. Metcalfe, S. M. Burke, S. S. Ahmed and H. J. Curran, "A Hierarchical andComparative KineticModeling Studyof C 1−C 2 Hydrocarbonand Oxygenated Fuels," International journal of chemical kinetics, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 638-675, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Olm, T. Varga, É. Valkó, S. Hartl, C. Hasse and T. Turányi, "Development of an Ethanol Combustion Mechanism Based on a Hierarchical Optimization Approach," International journal of chemical kinetics, vol. 48, no. 8, pp. 423-441, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Dubey and K. Bhadraiah, "On the Estimation and Validation of Global Single-Step Kinetics Parameters of Ethanol-Air Oxidation Using Diffusion Flame Extinction Data," Combustion Science and Technology, vol. 183, no. 1, pp. 43-50, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Millán-Merino, E. Fernández-Tarrazo, M. Sánchez-Sanz and F. A. Williams, "A Multipurpose Reduced Mechanism for Ethanol Combustion," Combustion and ame, vol. 193, pp. 112-122, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Abdelsamie, W. Guana, M. Nanjaiahc, I. Wlokas, H. Wiggers and D. Thévenin, "Investigating the impact of dispersion gas composition on the flame structure in the SpraySyn burner using DNS," Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, vol. 40, no. 1-2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Wako, G. Pio and E. Salzano, "Reduced Combustion Mechanism for Fire with Light Alcohols," Fire, vol. 4, no. 86, 2021.

- Bhagatwala, J. H. Chen and T. Lu, "Direct numerical simulations of HCCI/SACI with ethanol," Combustion and Flame, vol. 161, no. 7, pp. 1826-1841, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pereira and A. L. D. Bortoli, "Solutions for a turbulent jet diffusion flame of ethanol with NOx formation using a reduced kinetic mechanism obtained by applying ANNs," Fuel, vol. 231, pp. 373-378, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Minuzzi and J. M. d. Pinho, "A new skeletal mechanism for ethanol using a modified implementation methodology based on directed relation graph (DRG) technique," Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, vol. 42, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pichler and E. Nilsson, "Pathway analysis of skeletal kinetic mechanisms for small alcohol fuels at engine conditions," Fuel, vol. 275, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Work | Type | Fuel |

Species /Reaction |

Reduction Method | Validated Config. | Validation Targets | Notes / Rationale |

| [32] | Detailed (foundational) | Ethanol | ~50+ / ~300+ | N/A (comprehensive mechanism) | Premixed flame (flame speeds), shock tube, JSR | Laminar flame speeds, ignition delays (premixed/JSR) | First detailed ethanol mechanism by LLNL*; widely used for high-T ethanol oxidation. No direct diffusion flame validation in original work, but serves as a foundational model. |

| [55] | Detailed (foundational) | Ethanol (with NOx & C3) |

36–57 / 192–288 | N/A (built from prior C1–C2 chemistry) | Counterflow diffusion flame (laminar, opposed jets); partially premixed flame | Extinction strain rates; flame structure (T, species profiles) | “San Diego” mechanism optimized for ethanol. Validated against shock ignition, flame speeds, and new counterflow diffusion flame experiments (species & temperature profiles at strain ~100 s^–1). Performs as well as larger mechanisms. |

| [56] | Detailed (foundational) | C1–C2 incl. ethanol | 50+ / 200+ | Hierarchical assembly (Galway AramcoMech 1.3) | Premixed flames, shock, RCM, JSR (no specific diffusion flame) | Laminar flame speeds, ignition delays, speciation in reactors | Comprehensive mechanism for small hydrocarbon/alcohol fuels. Validated on extensive datasets (premixed flames, reactors), but no specific diffusion flame validation reported (used mainly as reference mechanism). |

| [57] | Detailed (optimized) | Ethanol | 49 / 251 | Mechanism optimization (genetic algorithm) | Counterflow flames (species profiles), premixed flames, shock tube | Ignition delays, laminar flame speeds, flame species profiles | Optimized detailed model based on Saxena’s mech. Achieved good accuracy for ignition, flame propagation and species profiles in flames. Provides a tuned mechanism over wide conditions; used as “ELTE” mechanism in later studies. |

| [58] | Global (1-step) | Ethanol | 1 overall step | Empirical fit (extinction data) | Counterflow diffusion flame (laminar opposed flow); porous-sphere flame | Extinction strain rate (critical “blow-off” velocity) | Single-step global kinetics fitted to non-premixed flame extinction behavior. Validated by predicting opposed-flow flame extinction limits consistent with experiments. Simplest mechanism for CFD; captures overall reactivity but no intermediate species detail. |

| [59] | Skeletal + QSSA (hybrid) | Ethanol | 31 / 66 (skeletal); 16 / 14 global steps (QSSA) | Path analysis + QSSA steady-state reduction | Counterflow diffusion flame (laminar) – flame structure & extinction; also premixed flames, autoignition | Flame structure (T, major species profiles) and extinction strain rate | Developed multipurpose skeletal (66-step) and reduced QSSA (14-step) mechanisms. Validated against ethanol counterflow flame structure and extinction limits, with performance comparable to a 257-step detailed mechanism. Achieves ~80% CPU reduction vs detailed model with minimal accuracy loss. |

| [60] | Skeletal (reduced) | Ethanol | 35 / 87 | QSSA-based reduction (steady-state for intermediates) | Coflow spray flame (laminar DNS in hot coflow) | Flame structure & quenching (OH/CH2O fields, flame length) | Compact skeletal mechanism for ethanol spray flames. Applied quasi-steady state assumptions to shrink a detailed model to 35 species. Used in DNS of an ethanol spray flame (SpraySyn burner) to study flame quenching under electric fields. Validated by matching flame structure observations; facilitates LES/DNS of spray flames. |

| [61] | Skeletal (reduced for fires) | Ethanol (and MeOH) | ~20–30 / – (not reported exact) | Sensitivity & path analysis | Pool fires, tank fires (turbulent; 3D CFD) | Burning rate, flame height; product yields (CO, soot) | Reduced mechanism for fire scenarios (open-air ethanol/methanol fires). Key intermediates (e.g. C2H2, C2H4, C3H3) retained to predict soot precursors. Validated by 3D CFD of pool fires – good agreement with literature data on flame behavior and emissions. Enables safety simulations (fuel spills, storage fires). |

| [62] | Skeletal (reduced) | Ethanol | 28 / (reactions not stated) | Directed reduction (from ~145-spec detailed) | HCCI autoignition (0D); no direct diffusion flame | Ignition timing, pressure rise in HCCI; (later used in spray flame LES) | 28-species reduced mechanism developed for engine conditions. Validated for HCCI and premixed autoignition (high-pressure) – not initially validated on diffusion flames. Included here for completeness, but excluded from results table since diffusion flame performance is unproven (though it has been used in LES of ethanol flames). |

| [63] | Skeletal (ANN-derived) | Ethanol (with NOx) | 26-30/ 43 | ANN | Turbulent jet diffusion flame (non-premixed) | Flame structure (T, species) and NOx formation | ANN-based reduction produced a 43-step skeletal mechanism for ethanol (including NOx formation chemistry); validated on a turbulent diffusion flame (jet) with predictions agreeing well with literature flame data (species profiles, NOx). This work demonstrates the viability of machine-learning techniques in mechanism reduction for ethanol flames. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).