Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Numerical Model

2.1.1. Chemical Kinetics Mechanisms and Turbulence Models

2.1.2. Soot Formation Mechanism

2.1.3. Computational Grid and Boundary Conditions

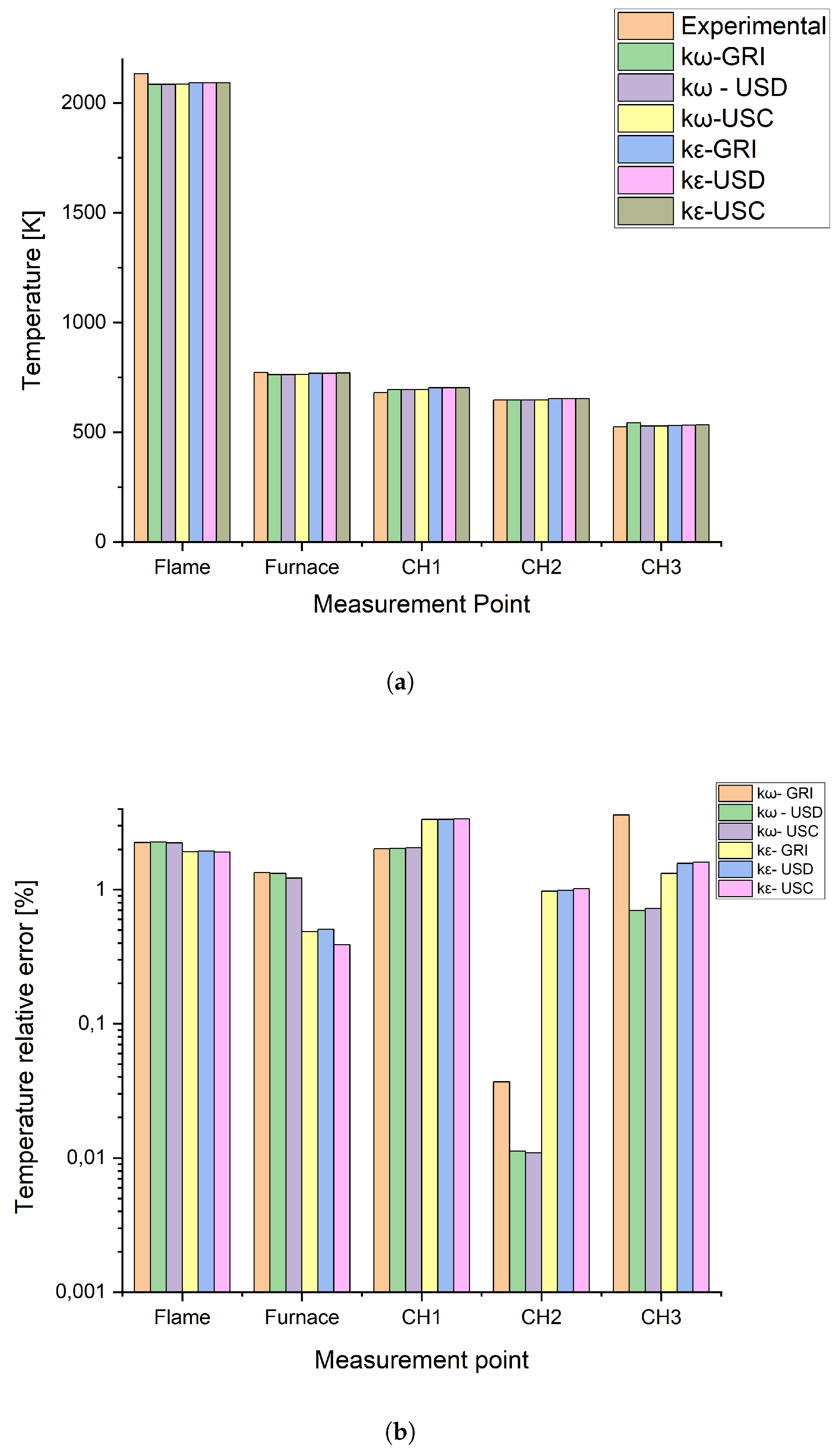

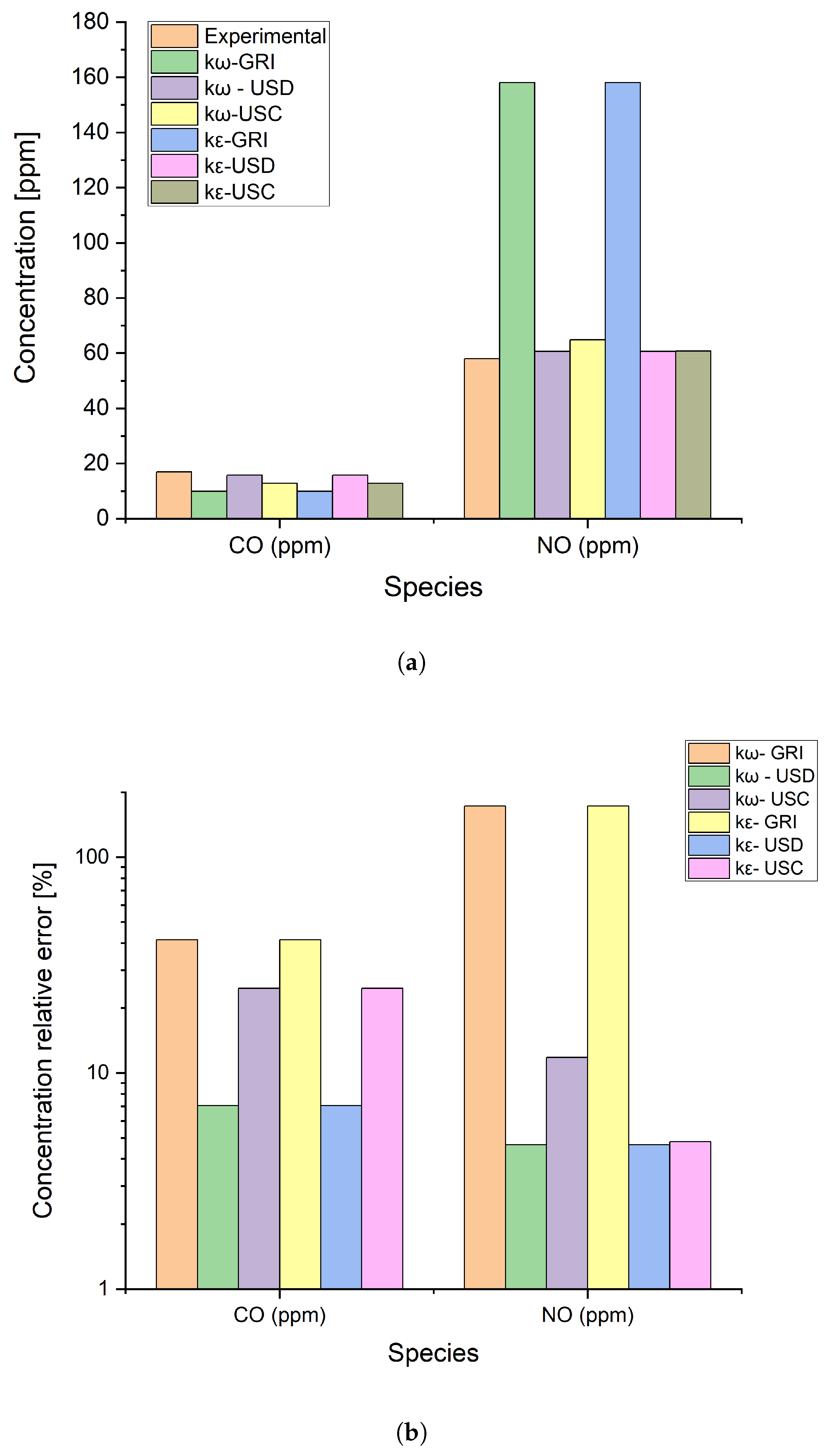

2.1.4. Numerical Model Validation

2.2. Biomethane-Hydrogen Blends

3. Results and Discussion

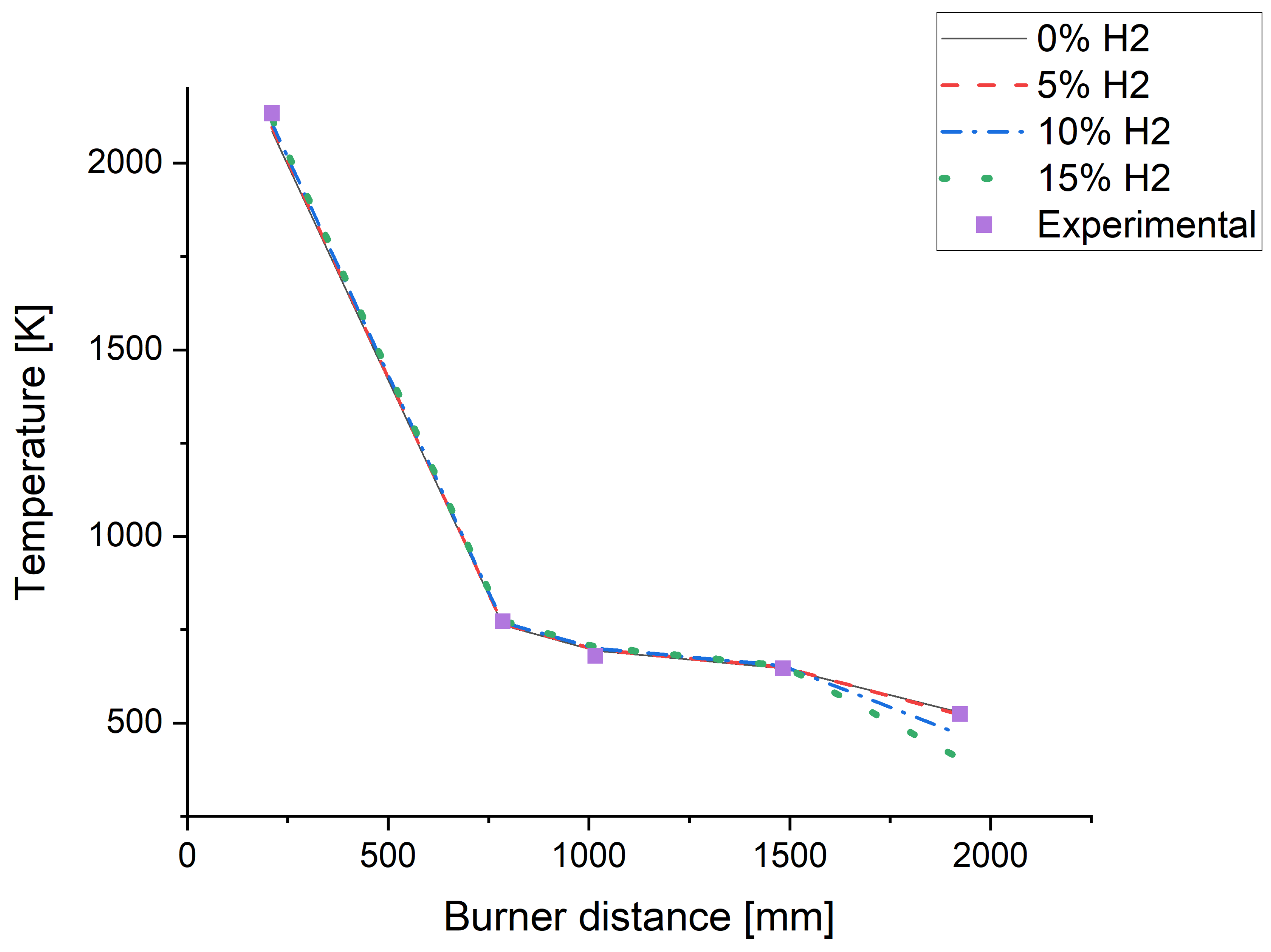

3.1. Flame Structure And Temperature Profile

3.2. Pollutant Emissions

3.3. Radiation Heat Transfer Impacts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA-2024. Global Hydrogen Review 2024 – Analysis, License: CC BY 4.0.

- Naseem, K.; Qin, F.; Khalid, F.; Suo, G.; Zahra, T.; Chen, Z.; Javed, Z. Essential parts of hydrogen economy: Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and application. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.I.; Pitombeira-Neto, A.R.; Bueno, A.V.; Rocha, P.A.C.; de Andrade, C.F. Probabilistic wind speed forecasting via Bayesian DLMs and its application in green hydrogen production. Applied Energy 2025, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lobo, F.L.; Bian, Y.; Lu, L.; Chen, X.; Tucker, M.P.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Z.J. Electrical decoupling of microbial electrochemical reactions enables spontaneous H2 evolution. Energy and Environmental Science 2020, 13, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rezende, T.T.G.; Venturini, O.J.; Palacio, J.C.E.; de Oliveira, D.C.; de Souza Santos, D.J.; Lora, E.E.S.; Filho, F.B.D. Technical and economic potential for hydrogen production from biomass residue gasification in the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulraiz, A.; Bastaki, A.J.A.; Magamal, K.; Subhi, M.; Hammad, A.; Allanjawi, A.; Zaidi, S.H.; Khalid, H.M.; Ismail, A.; Hussain, G.A.; et al. Energy Advancements and Integration Strategies in Hydrogen and Battery Storage for Renewable Energy Systems. iScience, 2025; 111945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichouni, I.E.; Mridekh, A.; Nabil, N.; Rachidi, S.; Hamraoui, H.E.; Mansouri, B.E.; Essalih, A. A review of salt mechanical behavior, stability and site selection of underground hydrogen storage in salt cavern-Moroccan case. Journal of Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Krutoff, A.C.; Wappler, M.; Fischer, A. Key influencing factors on hydrogen storage and transportation costs: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, L.H.S.; da Silva, A.K. Global assessment of hydrogen production from the electrical grid aiming the Brazilian transportation sector. Energy for Sustainable Development 2025, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.L.M.; Alves, C.M.; Andrade, C.F.; de Azevedo, D.C.; Lobo, F.L.; Fuerte, A.; Ferreira-Aparicio, P.; Caravaca, C.; Valenzuela, R.X. Recent Progress and Perspectives on Functional Materials and Technologies for Renewable Hydrogen Production. ACS Omega 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Pournazeri, S.; Princevac, M.; Miller, J.W.; Mahalingam, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Jayaram, V.; Welch, W.A. Effect of hydrogen addition on criteria and greenhouse gas emissions for a marine diesel engine. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 11336–11345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, P.; Cao, E.; Tan, Q.; Wei, L. Effects of alternative fuels on the combustion characteristics and emission products from diesel engines: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 71, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Bao, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H. Numerical simulation of flow, combustion and NO emission of a fuel-staged industrial gas burner. Journal of the Energy Institute 2017, 90, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.H.; Tsolakis, A.; Alagumalai, A.; Mahian, O.; Lam, S.S.; Pan, J.; Peng, W.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. Use of hydrogen in dual-fuel diesel engines. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2023, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kurien, C.; Mittal, M. Computational investigation and analysis of cycle-to-cycle combustion variations in a spark-ignition engine utilizing methane-ammonia blends. Fuel 2025, 386, 134313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.L.; Lewis, A.C. Emissions of NOx from blending of hydrogen and natural gas in space heating boilers. Elementa 2022, 10. Hydrogen burn has higher adiabatic flame temperature...Wright, 2022, assesses the NOx emisson and damage cost of hydrogen blend in natural gas netwok for domestic heating in USA. The authors warns about the poor performing domestic boilers being a critical poit on positive envieromental impact of the use of H2-CH4 blend fot domestic purposes. [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z. Bridging the energy future: The role and potential of hydrogen co-firing with natural gas. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.V.; Vilarrasa-García, E.; Torres, A.E.B.; de Oliveira, M.L.M.; de Andrade, C.F. ANALYSIS OF THE FEASIBILITY OF HYDROGEN INJECTION IN PIPELINE GAS DISTRIBUTION NETWORKS. Revista de Gestao Social e Ambiental 2024, 18. Bueno, 2024, set guidelines for safe blend of H2 in existing natual gás distribution lines, focusses on the characteristics of the net supliying Fortaleza city. It was found a safe range between 2% and 3% for imediat use, and prospected a limit of 10% when adquate H2 embrittlement studies are carried out. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Pluvinage, G.; Julien, C. Reliability index of a pipe transporting hydrogen submitted to seismic displacement. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping 2024, 208. Lucas, 2024, explais the main hypothesis for stell hydrogen embrittlement while predicting realiability index of H2 conductig pippes birried in seismic activity zones. [CrossRef]

- Hasche, A.; Krause, H.; Eckart, S. Hydrogen admixture effects on natural gas-oxygen burner for glass-melting: Flame imaging, temperature profiles, exhaust gas analysis, and false air impact. Fuel 2025, 387. Hasche, 2025, proceeded experimentation burning methane-hydogen blends with pure oxygen. The flame temperature reached up to 2050ºC with an O2 excess combustion, and a controled injection of N2 evidenced the raise os NOx emission with the H2 ratio growth. [CrossRef]

- Gee, A.J.; Smith, N.; Chinnici, A.; Medwell, P.R. Characterisation of turbulent non-premixed hydrogen-blended flames in a scaled industrial low-swirl burner. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 747–757. Adam et al. realizaram a caracterização de misturas de gás natural com hidrogênio em diferentes proporções em uma chama turbulenta não pre-misturada. Os resultados apresentaram uma redução de 33emitida e um aumento de 380characterization of natural gas and hydrogen mixtures in different proportions in a non-premixed turbulent flame. The results showed a 33reduction in emitted radiation and a 380.

- Rahimi, S.; Mazaheri, K.; Alipoor, A.; Mohammadpour, A. The effect of hydrogen addition on methane-air flame in a stratified swirl burner. Energy 2023, 265. Rahimi,2023, developed a CFD code using OpenFOAM, aiming to undesrtande the influences of Hydrogen gas to a Methane burn in different slots of stratified industrial burner. The bigger the hydrogen adition, bigger the CO emisssion reduction and NOx emission raise. For stratified burn cases it was reached a theorical max flame temperature, of 2000K for 100methane and up to 2300k for 40. [CrossRef]

- Kruljevic, B.; Darabiha, N.; Durox, D.; Vaysse, N.; Renaud, A.; Vicquelin, R.; Fiorina, B. Experimentation and simulation of a swirled burner featuring cross-flow hydrogen injection with a focus on the OH* chemiluminescence. Combustion and Flame 2025, 273. Kruljevic, 2025, modeled a swirled partially-premixedhydrogen–air flame with two different hydrogen injection flows, focussing on the OH radicals formation. They found close relation between the heat release rate and the OH radicals in lean regions of the flame, and evidences of higher amounts of OH in the burnt gases in conditions close to stoichiometry. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, B.; Gao, Q.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Experimental and numerical study on adiabatic laminar burning velocity and overall activation energy of biomass gasified gas. Fuel 2022, 320. When burning biomass gasified gas (BGG) Zhou, 2022, predicted most accurately the overall activation energy runing San Diego combustion chemical-kinetic mechanisms, whereas USC-Mech 2.0 displayed the best overall performance. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.P.; Golden, D.M.; Frenklach, M.; Moriarty, N.W.; Eiteneer, B.; Goldenberg, M.; Bowman, C.T.; Hanson, R.K.; Song, S. ; Jr., W.C.G.; et al. GRI-Mech 3.0.

- Mechanical.; of California at San Diego, A.E.C.R.U. Chemical Mechanism: Combustion Research Group at UC San Diego.

- Wang, H.; You, X.; Joshi, A.V.; Davis, S.G.; Laskin, A.; Egolfopoulos, F.; Law, C.K. USC Mech Version II. High-Temperature Combustion Reaction Model of H2/CO/C1-C4 Compounds.

- Ji, C.; Wang, D.; Yang, J.; Wang, S. A comprehensive study of light hydrocarbon mechanisms performance in predicting methane/hydrogen/air laminar burning velocities. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 17260–17274. On the other hand, assessing chemical-kinetic mechanisms for different methane-hydrogen blends and equivalence ratios, Ji, 2017, found that USC-Mech 2.0 performed better for H2 ratios lower than 30Diego mechanism had the best overall performance. [CrossRef]

- Al-ajmi, R.; Qazak, A.H.; Sadeq, A.M.; Al-Shaghdari, M.; Ahmed, S.F.; Sleiti, A.K. Numerical investigation of the potential of using hydrogen as an alternative fuel in an industrial burner. Fuel 2025, 385, 134194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zier, M.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. A review of decarbonization options for the glass industry. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2021, 10. Glass production industry takes relevant place on recent climate crisis in means of global energy demand. Zier, 2021, placed this sector in the third place in means of energy consumed per product mass, mainly due to the high temperature required for the raw glass melting, between 1470K and 1870K.Continous glass melting furnaces that have burners placed by the bottom of the melting bed strongly relies on thermal radiation for the hot spot glass heating up (Zier,2021). Thus, changes on radiative behaviour of the flame due to hydrogen injection, suche as the ones observed by ####, might be of great relevance for industrial process retrofitting. [CrossRef]

- Daurer, G.; Schwarz, S.; Demuth, M.; Gaber, C.; Hochenauer, C. On the use of hydrogen in oxy-fuel glass melting furnaces: An extensive numerical study of the fuel switching effects based on coupled CFD simulations. Fuel 2024. Daurer, 2025, carried out extensive CFD simulations using two validated industrial glass melting furnace models, assessing CH4-O2 and H2-O2 flame shapes and temperatures.... Comparar resultados deste artigo com so nossos e referenciar nos resultados. [CrossRef]

- Kuzuu, N.; Kokubo, Y.; Nishimura, T.; Serizawa, I.; Zeng, L.H.; Fujii, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Saito, K.; Ikushima, A.J. Structural change of OH-free fused quartz tube by blowing with hydrogen-oxygen flame. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2004, 333, 115–123. Kuzuu, 2004, assessed the increasing of OH radical on quartz glass tube due to hydrogen-oxygen flame blowing. [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, Y.; Kuzuu, N.; Serizawa, I.; Zeng, L.H.; Fujii, K. Structural changes of various types of silica glass tube upon blowing with hydrogen-oxygen flame 2004. 349, 38–45. Kokubo, 2004, tested hydrogen-oxygen flame blow on quartz glass tubes contanining different OH concentrations, concerning to ligh band absorption, for microscopic spectroscopy porpuses. [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, H. Modeling analysis on the silica glass synthesis in a hydrogen diffusion flame. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2015, 81, 797–803. The flame hydrolysis deposition technology for silica glass synthesis is modeled by Yao, 2015, highlighting temperature, droplets diameter and OH radicals inflience on the homogeity of the synthesis. The model, burning a hidrogen-oxygen blend, leads to best silica conversion at stoichiometric ratio but hydrogen excess leads to lower OH radical concentration in the glass structure. [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA Journal 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, B.E.B.E.; Spalding, D.B.D.B. Lectures in mathematical models of turbulence / B. E. Launder and D. B. Spalding.; Academic Press: London, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, S.; Moss, J. Predictions of soot and thermal radiation properties in confined turbulent jet diffusion flames; Vol. 116, Elsevier, 1999; pp. 486–503.

- Chui, E.; Raithby, G. Computation of radiant heat transfer on a nonorthogonal mesh using the finite-volume method. Numerical Heat Transfer 1993, 23, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raithby, G.; Chui, E. A finite-volume method for predicting a radiant heat transfer in enclosures with participating media. Journal of Heat Transfer 1990, 112, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, J.; Mathur, S. Finite volume method for radiative heat transfer using unstructured meshes. Journal of thermophysics and heat transfer 1998, 12, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS ® FLUENT, Release 15.0. Help System, Theory Guide.

- Lemmi, G.; Castellani, S.; Nassini, P.; Picchi, A.; Galeotti, S.; Becchi, R.; Andreini, A.; Babazzi, G.; Meloni, R. FGM vs ATF: A comparative LES analysis in predicting the flame characteristics of an industrial lean premixed burner for gas turbine applications. Fuel Communications 2024, 19, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheshlaghi, M.K.G.; Tahsini, A.M. Numerical investigation of hydrogen addition effects to a methane-fueled high-pressure combustion chamber. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33732–33745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, A.H.; Ballal, D.R. Gas turbine combustion: alternative fuels and emissions; CRC press, 2010.

- Gao, Y.; Lu, Z.; Hua, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C.; Gao, W. Experimental study on the flame radiation fraction of hydrogen and propane gas mixture. Fuel 2022, 329, 125443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Axelbaum, R.; Law, C.K. Soot formation in strained diffusion flames with gaseous additives. Combustion and flame 1995, 102, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substance | Chemical Formula | Mole Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| Methane | 92.98% | |

| Ethane | 6.29% | |

| Propane | 0.36% | |

| n-Butane | 0.03% | |

| i-Butane | 0.03% | |

| n-Pentane | 0.001% | |

| Carbon Dioxide | 0.30% | |

| Nitrogen | 0.00% |

| Species | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | 0.00 % | 5.00 % | 10.00 % | 15.00 % |

| CH4 | 92.98 % | 88.33 % | 83.68 % | 79.03 % |

| CO3 | 0.30 % | 0.29 % | 0.27 % | 0.26 % |

| C2H6 | 6.29 % | 5.98 % | 5.66 % | 5.35 % |

| C3H8 | 0.43 % | 0.41 % | 0.39 % | 0.36 % |

| Hydrogen enrichment | CO | NO |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0% | 15.80 ppm | 60.70 ppm |

| 5.0% | 20.24 ppm | 61.73 ppm |

| 10.0% | 23.60 ppm | 63.03 ppm |

| 15.0% | 27.27 ppm | 64.46 ppm |

| Hydrogen enrichment | Flame | Ch5 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0% | 16.54% | 11.61% |

| 5.0% | 16.84% | 11.81% |

| 10.0% | 17.17% | 12.04% |

| 15.0% | 17.52% | 12.29% |

| Hydrogen enrichment | Flame OH | Ch5 OH |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0% | 3324.39 ppm | 404.48 ppm |

| 5.0% | 3455.29 ppm | 431.33 ppm |

| 10.0% | 3591.12 ppm | 459.00 ppm |

| 15.0% | 3717.11 ppm | 490.29 ppm |

| Hydrogen enrichment | Incident radiation |

|---|---|

| 0.0% | 961.3774 |

| 5.0% | 972.3523 |

| 10.0% | 978.276 |

| 15.0% | 965.5321 |

| 20.0% | 958.2644 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).