Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and methods

1. Sampling Technique for Dipterans and Pool Composition

2. High-Throughput Sequencing, and Virus Discovery Pipeline

3. Estimation of Virus Completeness and Virus Naming

4. Data Analysis and Visualization

Results

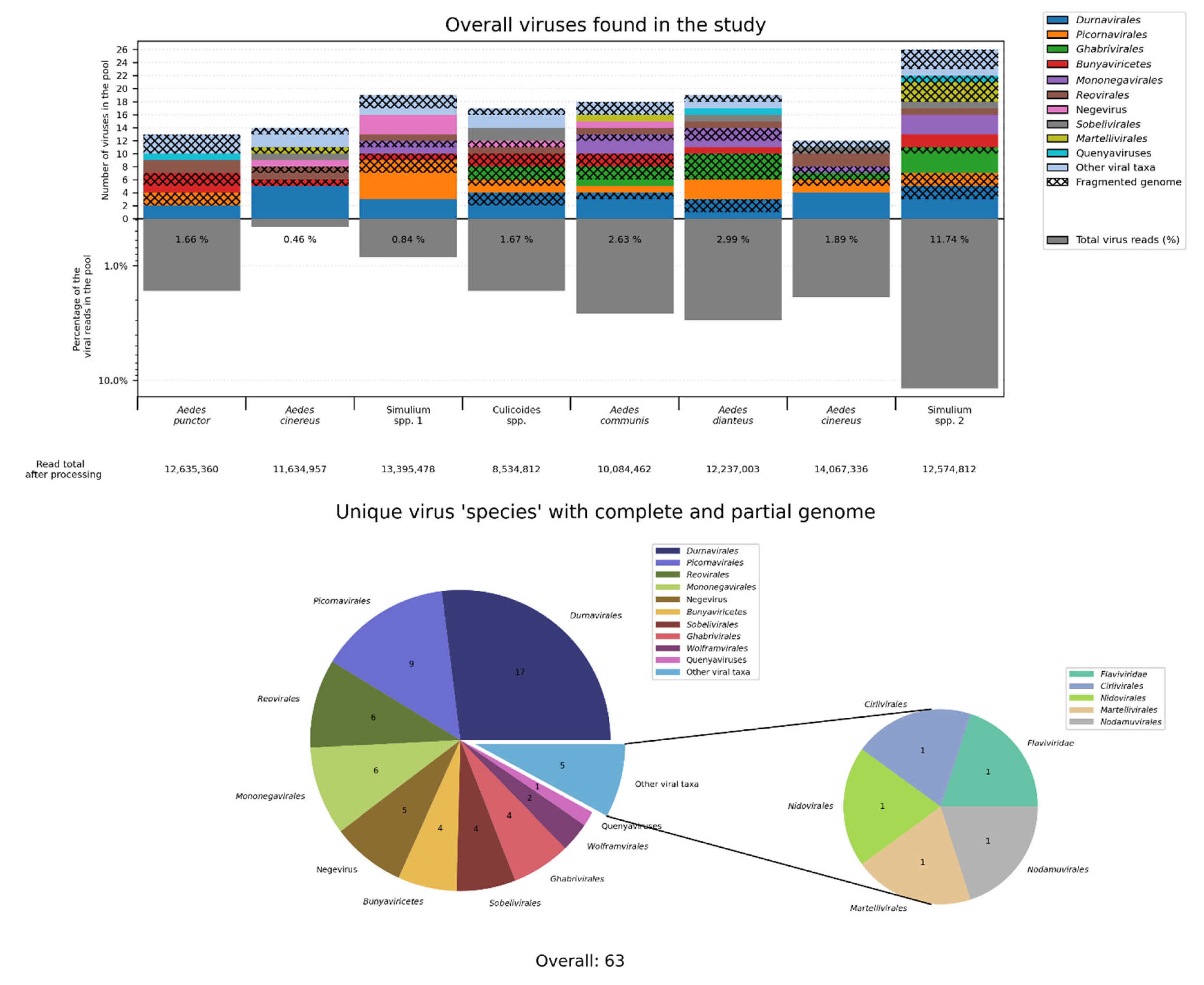

1. High-Throughput Sequencing

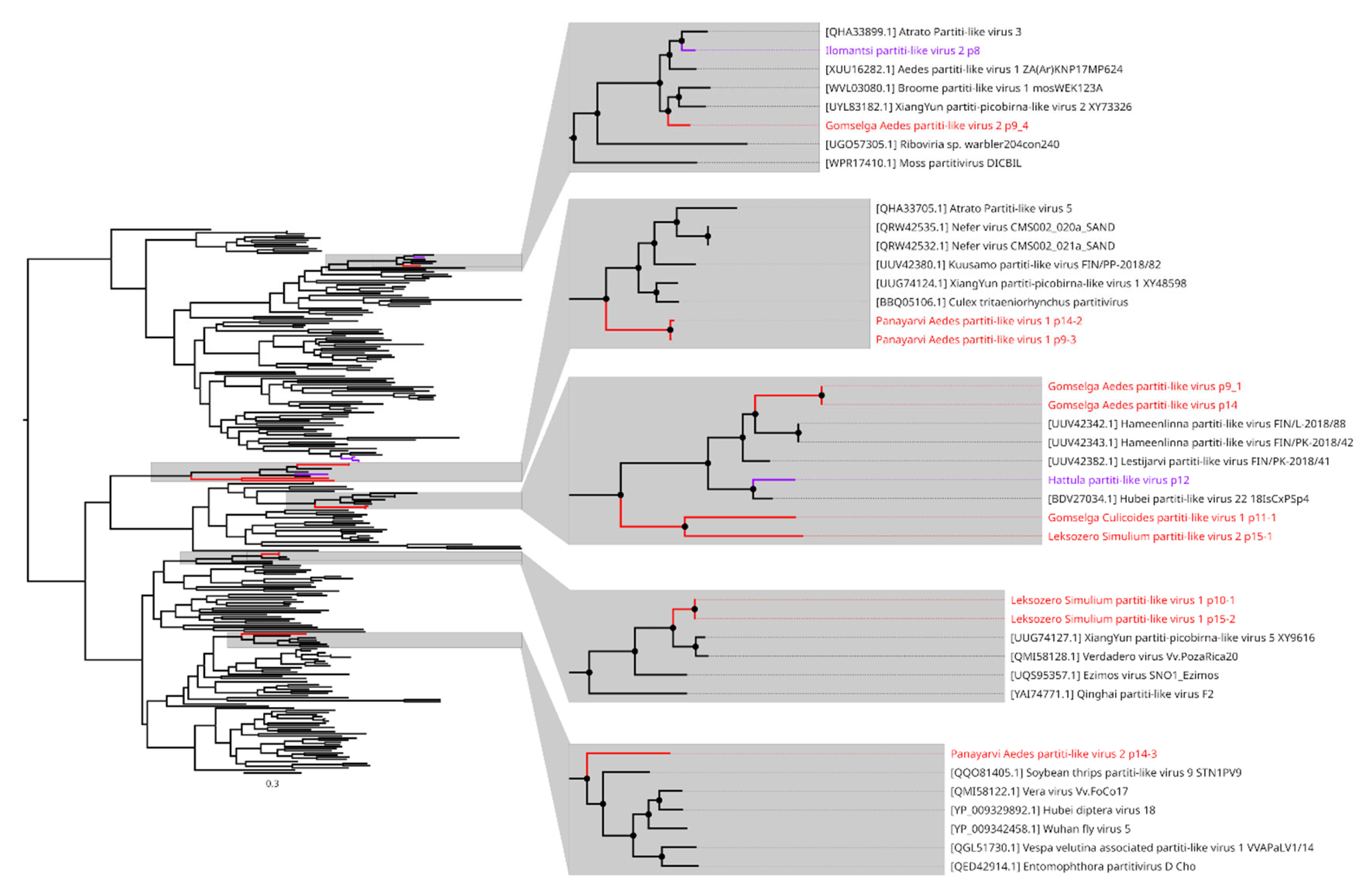

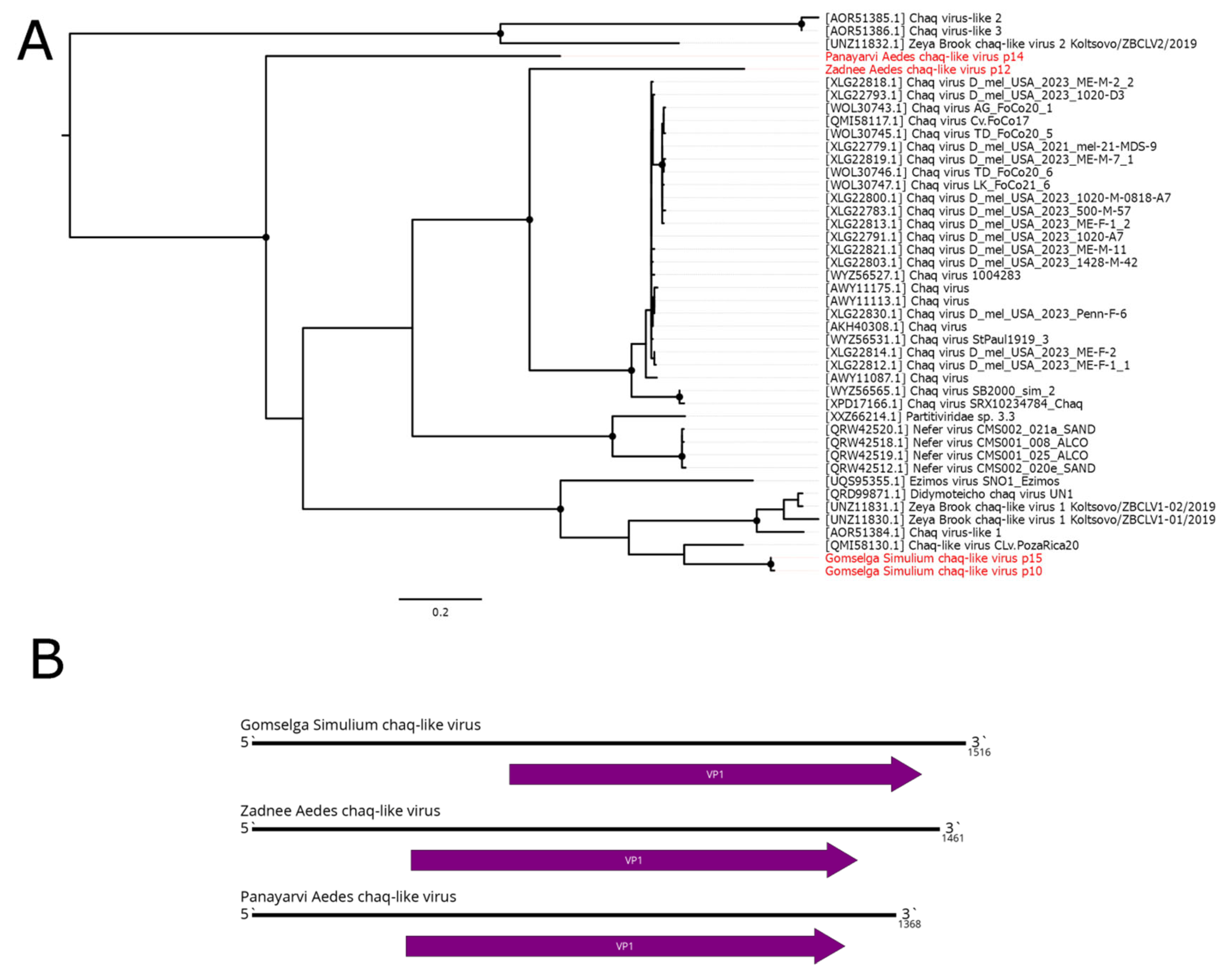

2. Durnavirales

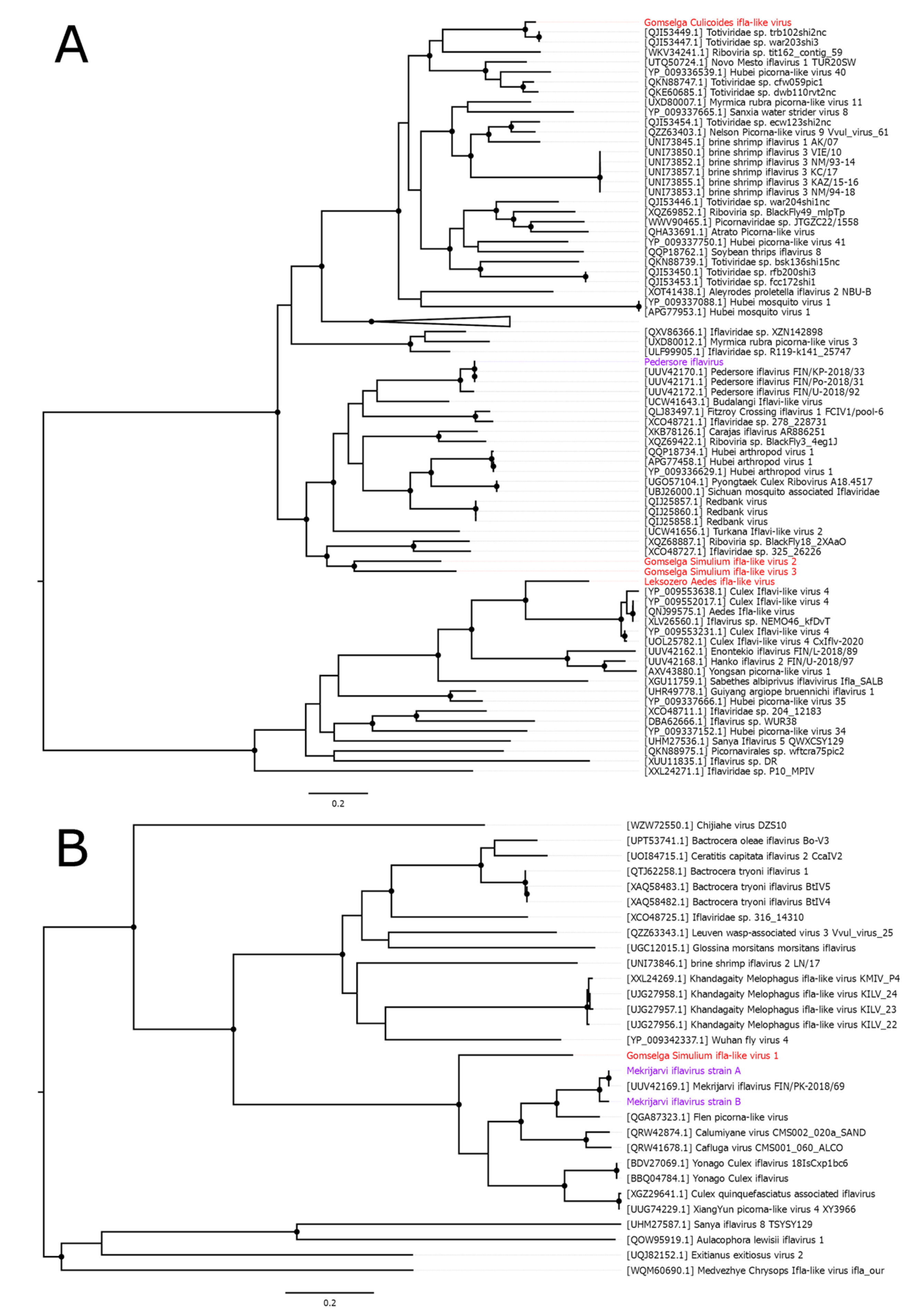

3. Picornavirales

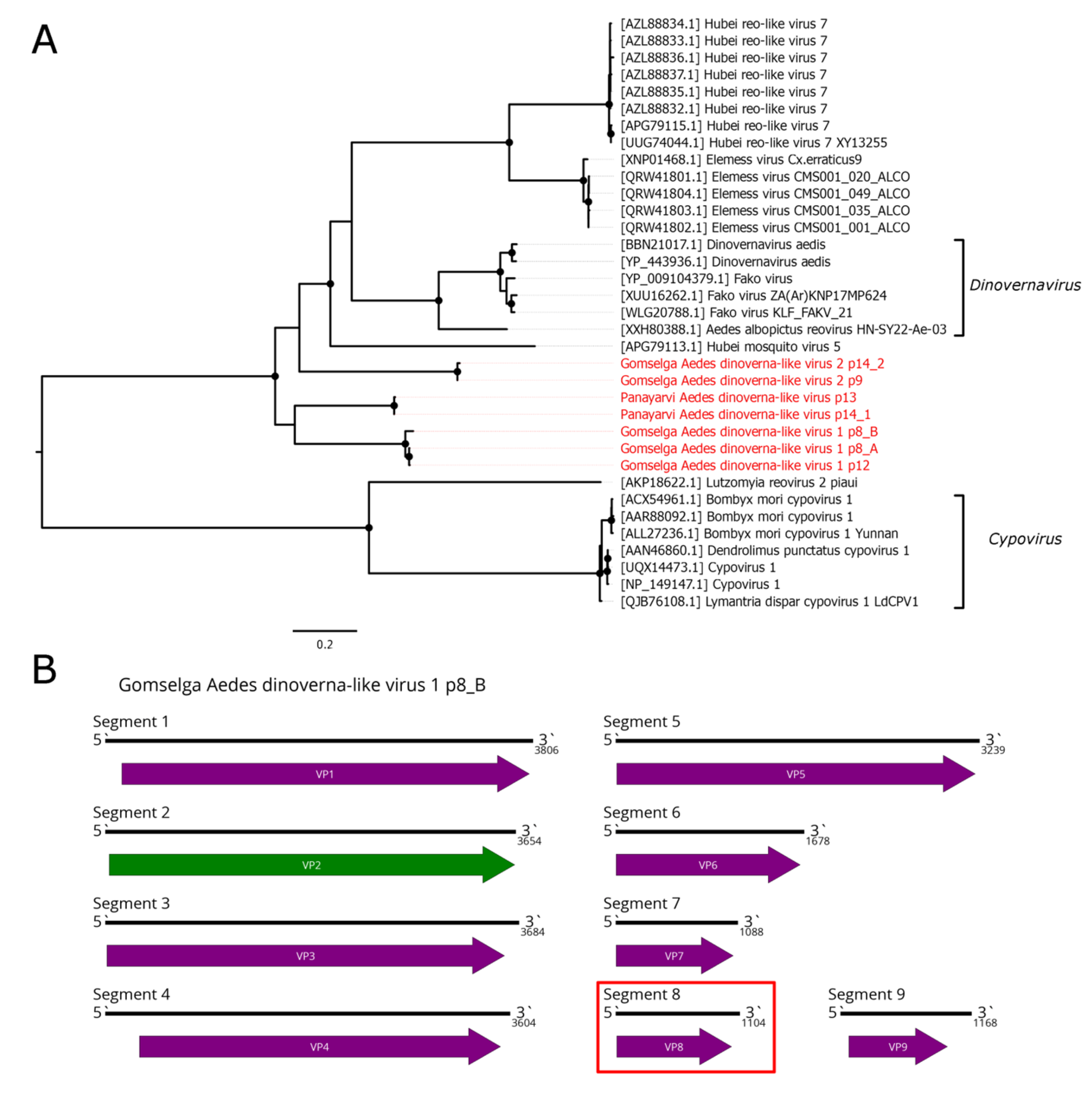

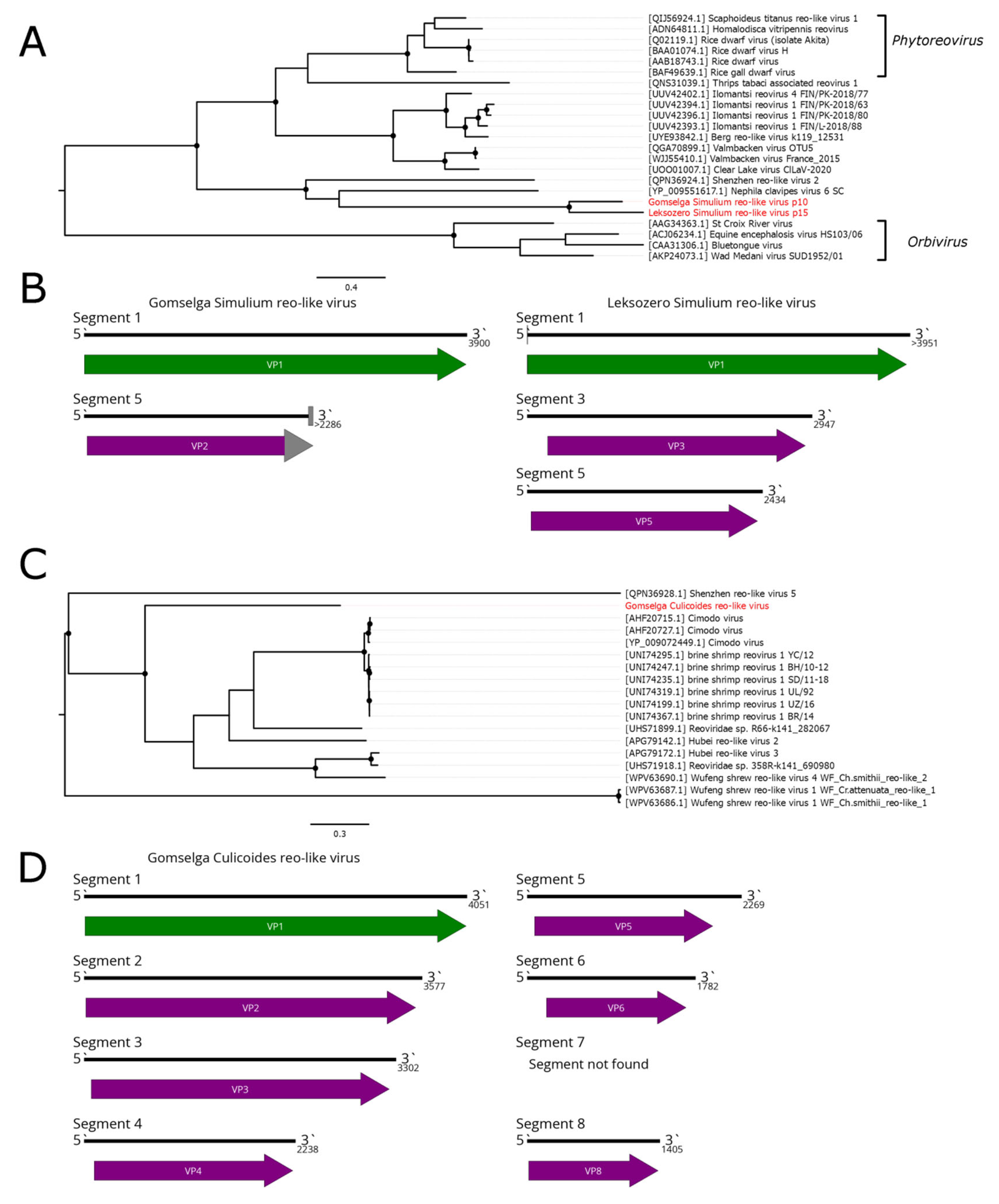

4. Reovirales

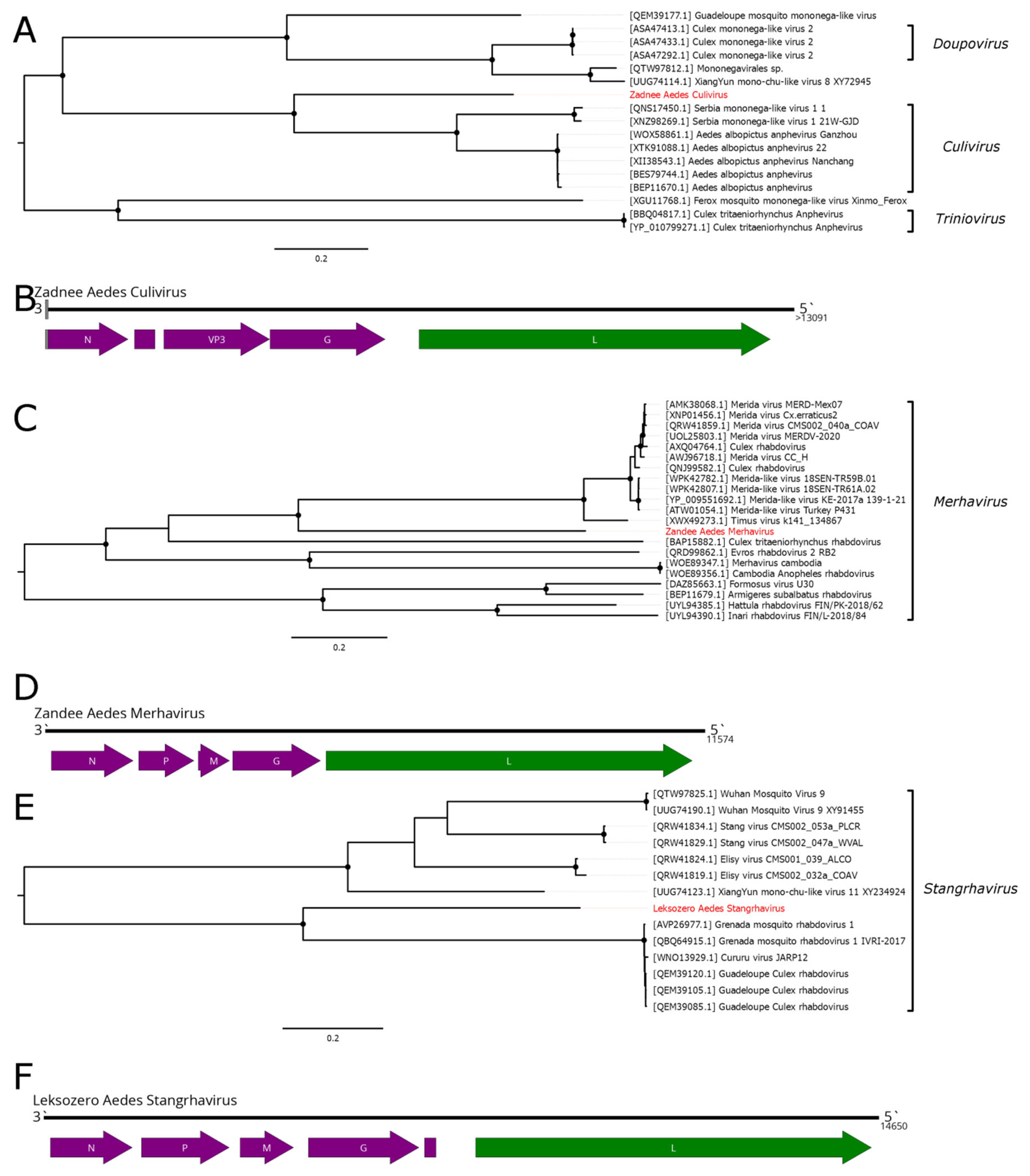

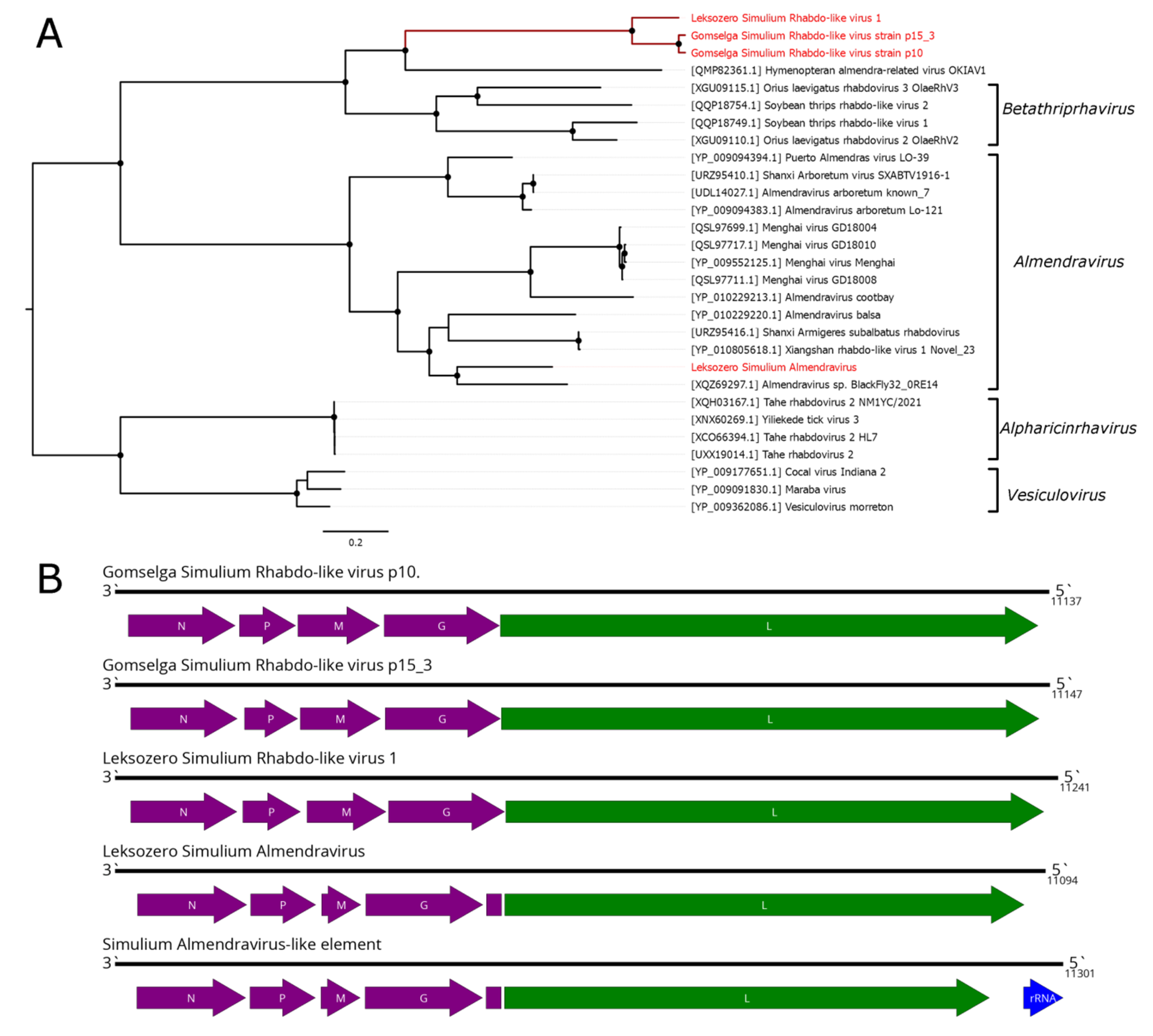

5. Mononegavirales

6. Other Virus Groups

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

References

- De Almeida, P.P.; Aguiar, E.R.G.R.; Armache, J.N.; Olmo, R.P.; Marques, T. The Virome of Vector Mosquitoes. Curr Opin Virol 2021, 49, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; Drake, J.M.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Myers, M.F.; et al. The Global Distribution and Burden of Dengue. Nature 2013, 496, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikan, N.; Smith, D.R. Zika Virus: History of a Newly Emerging Arbovirus. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, e119–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelossi-Cebinelli, G.; Carneiro, J.A.; Yaekashi, K.M.; Bertozzi, M.M.; Bianchini, B.H.S.; Rasquel-Oliveira, F.S.; Zanluca, C.; Duarte dos Santos, C.N.; Arredondo, R.; Blackburn, T.A.; et al. A Review of the Biology of Chikungunya Virus Highlighting the Development of Current Novel Therapeutic and Prevention Approaches. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, A.C. Changing Patterns of West Nile Virus Transmission: Altered Vector Competence and Host Susceptibility. Vet Res 2009, 40, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. Emerging Vector-Borne Flavivirus Diseases: Are Vaccines the Solution? Expert Rev Vaccines 2011, 10, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.; Tian, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Cao, J.; Eden, J.; et al. Redefining the Invertebrate RNA Virosphere. Nature 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseille, R.; Nebbak, A.; Monteil-bouchard, S.; Berenger, J.; Almeras, L.; Parola, P.; Desnues, C. Virome Diversity among Mosquito Populations in a Sub-Urban Region of Marseille, France. Viruses 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoni, E.; Wang, Y.; Karungu, S.; Waruhiu, C.; Zohaib, A.; Obanda, V.; Agwanda, B.; Mutua, M.; Xia, H.; Yuan, Z. Metagenomic Virome Analysis of Culex Mosquitoes from Kenya and China. Viruses 2018, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.T.T.; Culverwell, C.L.; Suvanto, M.T.; Korhonen, E.M.; Uusitalo, R.; Vapalahti, O.; Smura, T.; Huhtamo, E. Characterisation of the RNA Virome of Nine Ochlerotatus Species in Finland. Viruses 2022, 14, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, S.R.; Madhav, M.; Klein, M.J.; Blasdell, K.R.; Paradkar, P.N.; Lynch, S.E.; Eagles, D.; López-Denman, A.J.; Ahmed, K.A. Characterisation of the Virome of Culicoides Brevitarsis Kieffer (Diptera : Ceratopogonidae), a Vector of Bluetongue Virus in Australia. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Sivla, S.; Aragao, C.; Gorayeb, I.; Cruz, A.; Dias, D.; Nascimento, B.; Chiang, J.; Casseb, L.; Neto, J.; et al. Investigation of RNA Viruses in Culicoides Latreille, 1809 ( Diptera : Ceratopogonidae ) in a Mining Complex in the Southeastern Region of the Brazilian Amazon. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmam, S.; Monteil-Bouchard, S.; Robert, C.; Baudoin, J.-P.; Sambou, M.; Aubadie-ladrix, M.; Labas, N.; Raoult, D.; Mediannikov, O.; Desnues, C. Characterization of Viral Communities of Biting Midges and Identification of Novel Thogotovirus Species and Rhabdovirus Genus. Viruses 2016, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langat, S.K.; Eyase, F.; Bulimo, W.; Lutomiah, J.; Oyola, S.O.; Imbuga, M.; Sang, R. Profiling of RNA Viruses in Biting Midges (Ceratopogonidae) and Related Diptera from Kenya Using Metagenomics and Metabarcoding Analysis. mSphere 2021, 6, e00551-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, K.; Bampali, M.; Williams, M.D.C.; Dovrolis, N.; Gatzidou, E.; Papazilakis, P.; Nearchou, A.; Veletza, S.; Karakasiliotis, I. Dissecting the Species-Specific Virome in Culicoides of Thrace. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, W.; Cai, S.; Wang, J.; Kuang, G.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Han, X.; Pan, H.; Shi, M.; et al. Transcriptomic Investigation of the Virus Spectrum Carried by Midges in Border Areas of Yunnan Province. Viruses 2024, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laredo-Tiscareño, S.V.; Garza-Hernandez, J.A.; Tangudu, C.S.; Dankaona, W.; Rodríguez-Alarcón, C.A.; Adame-Gallegos, J.R.; De Luna Santillana, E.J.; Huerta, H.; Gonzalez- Peña, R.; Rivera-Martínez, A.; et al. Discovery of Novel Viruses in Culicoides Biting Midges in Chihuahua, Mexico. Viruses 2024, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayash, D.; Murota, K.; Faizah, A.N.; Amoa-Bosompem, M.; Higa, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Tsuda, Y.; Sawabe, K.; Isawa, H. RNA Virome Analysis of Hematophagous Chironomoidea Ies (Diptera : Ceratopogonidae and Simuliidae) Collected in Tokyo, Japan. Med. Entomol. Zool Vol. 2020(71), 225–243. [CrossRef]

- De Coninck, L.; Hadermann, A.; Colebunders, R.; Njamnshi, K.G.; Njamnshi, A.K.; Mokili, J.L.; Fodjo, J.; Matthijnssens, J. Cameroonian Blackflies (Diptera : Simuliidae) Harbour a Plethora of RNA Viruses. Virus Evol 2025, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkman, L.; Ahlm, C.; Evander, M.; Lwande, O.W. Mosquito-Borne Viruses Causing Human Disease in Fennoscandia—Past, Current, and Future Perspectives. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, RC; Linton, YM; Strickman, DA. Mosquitoes of the World.; Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2021; Vol. 1,2. [Google Scholar]

- Khalin, A. V.; Aibulatov, S. V.; Filonenko, I. V. Mosquito Distribution in Northwestern Russia: Species of the Genera Anopheles Meigen, Coquillettidia Dyar, Culex L., and Culiseta Felt (Diptera, Culicidae). Entomol Rev 2021, 101, 308–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalin, A. V.; Aibulatov, S. V.; Filonenko, I. V. Mosquito Distribution in Northwestern Russia: Species of the Genus Aedes Meigen (Diptera, Culicidae). Entomol Rev 2021, 101, 1060–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glukhova, V. M. The Biting Midges of Karelia. In Fauna of Karelian lakes. Invertebrates; Academy of Sciences USSR Publishing House: Moscow, Leningrad., 1965; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- Usova, Z.V. Black Flies of Karelia and the Murmansk Region; USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House: Moscow, Leningrad, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Khalin, A.V.; Aibulatov, S.V. Preparation Techniques for the Mosquitoes and the Blackflies (Diptera: Culicidae: Simuliidae). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS 2024, 328, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalin, A. V.; Aibulatov, S. V.; Przhiboro, A.A. Sampling Techniques for Bloodsucking Dipterans (Diptera: Culicidae, Simuliidae, Ceratopogonidae, Tabanidae). Entomol Rev 2021, 101, 1219–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Petrić, D.; Zgomba, M.; Boase, C.; Madon, M.B.; Dahl, C.; Kaiser, A. Mosquitoes: Identification, Ecology and Control; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-11622-4. [Google Scholar]

- Glukhova, V. M. Bloodsucking Midges of the Genera Culicoides and Forcipomyia (Ceratopogonidae). ; 5a ed.; 1989; Vol. 3.

- Glukhova, V. M. Culicoides (Diptera, Ceratopogonidae) of Russia and Adjacent Lands. Journal of Dipterological Research 2005, 16, 3–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yankovsky, A.V. A Key for the Identification of Blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae) of Russia and Adjacent Countries (Former USSR). Handbooks for the Identification of the Fauna of Russia Published by Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, 170; ZIN: Sankt-Petersburg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Litov, A.G.; Semenyuk, I.I.; Belova, O.A.; Polienko, A.E.; Van Thinh, N.; Karganova, G.G.; Tiunov, A. V Extensive Diversity of Viruses in Millipedes Collected in the Dong Nai Biosphere Reserve (Vietnam). Viruses 2024, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. Team., the U. Unipro UGENE: A Unified Bioinformatics Toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2013, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3Kazutaka Katoh; Daron M. Standley MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 772–780. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutierrez, S.; Silla-Martinez, J.M.; Gabaldon, T. TrimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-baez, A.S.; Holmes, E.C.; Charon, J.; Pettersson, J.H.; Hesson, J.C. Meta-Transcriptomics Reveals Potential Virus Transfer between Aedes Communis Mosquitoes and Their Parasitic Water Mites. Virus Evol 2022, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, E.J.; Chiba, S.; Ghabrial, S.A.; Maiss, E.; Roossinck, M.; Sabanadzovic, S.; Suzuki, N.; Xie, J.; Nibert, M.; Consortium, I.R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Partitiviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 7, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.L.; Waldron, F.M.; Robertson, S.; Crowson, D.; Ferrari, G.; Quintana, J.F.; Brouqui, J.M.; Bayne, E.H.; Longdon, B.; Buck, A.H.; et al. The Discovery, Distribution, and Evolution of Viruses Associated with Drosophila Melanogaster. PLoS Biol 2015, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; White, V.L.; Schlub, T.; Eden, J.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Holmes, E.C. No Detectable Effect of Wolbachia w Mel on the Prevalence and Abundance of the RNA Virome of Drosophila Melanogaster. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, S.M.; Chen, Y.; Firth, A.E.; Gu, D.M.A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Herrero, S.; De Miranda, J.R.; Ryabov, E. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Iflaviridae. Journal of General Virology 2017, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Brussaard, C.P.D.; Danthi, P.; del Vas, M.; Dermody, T.S.; Duncan, R.; Fāng, Q.; Johne, R.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Spinareoviridae 2022. Journal of General Virology 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Brussaard, C.P.D.; Danthi, P.; Del Vas, M.; Dermody, T.S.; Duncan, R.; Fāng, Q.; Johne, R.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Sedoreoviridae 2022. Journal of General Virology 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanns, K.; Zirkel, F.; Kurth, A.; Drosten, C.; Junglen, S. Cimodo Virus Belongs to a Novel Lineage of Reoviruses Isolated from African Mosquitoes. Journal of General Virology 2014, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, G.K.; Ayllón, M.A.; Bào, Y.; Basler, C.; Bavari, S.; Blasdell, K.R.; Briese, T.; Brown, P.A.; Bukreyev, A.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; et al. Taxonomy of the Order Mononegavirales: Update 2019. Arch Virol 2019, 164, 1967–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, S.R.; Paraskevopoulou, S. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Xinmoviridae 2023. Journal of General Virology 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, P.; Freitas-astúa, J.; Walker, P.J.; Astúa, J.F.-; Bejerman, N.; Blasdell, K.R.; Breyta, R.; Dietzgen, R.G. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Rhabdoviridae 2022. Journal of General Virology 2022, 103, 0–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlund, P.; Hayer, J.; Lundén, H.; Hesson, J.C.; Blomström, A.-L. Viromics Reveal a Number of Novel RNA Viruses in Swedish Mosquitoes. Viruses 2019, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboli, E.; Leggewie, M.; Altinli, M.; Schnettler, E. Mosquito-Specific Viruses—Transmission and Interaction. Viruses 2019, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.B.; Shapiro, A.; White, S.; Rao, S.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Carner, G.; Becnel, J.J. Molecular and Biological Characterization of a Cypovirus from the Mosquito Culex Restuans. J Invertebr Pathol 2011, 91, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.; Green, T.; Rao, S.; White, S.; Carner, G.; Mertens, P.P.C.; Becnel, J.J. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of a Cypovirus (Reoviridae) from the Mosquito Uranotaenia Sapphirina (Diptera : Culicidae). J Virol 2005, 79, 9430–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.T.; Maertens, B.L.; Dunham, T.J.; Rodgers, C.P.; Brehm, A.L.; Miller, M.R.; Williams, A.M.; Foy, B.D.; Stenglein, D. Partitiviruses Infecting Drosophila Melanogaster and Aedes Aegypti Exhibit Efficient Biparental Vertical Transmission. J Virol 2020, 94, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pool | Specimens in the Pool | Species | Location | Coordinates | Collection date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 60 | Aedes punctor (Kirby, 1837) | Kondopozhsky District, Village of Gomselga | 62.0683°N, 33.9592°E | 21.08.2024 |

| 9 | 34 | Aedes cinereus Meigen, 1818 | 31.07.2024; 20.08.2024 | ||

| 10 | 40 | Simulium equinum (Linnaeus, 1758); S. noelleri Friederichs, 1920; S. reptans (Linnaeus, 1758) | 31.07.2024 | ||

| 11 | 60 | Culicoides punctatus (Meigen, 1804); C. impunctatus Goetghebuer, 1920; C. obsoletus (Meigen, 1818) | 01.08.2024 | ||

| 12 | 60 | Aedes communis (De Geer, 1776) | Kostomukshsky Urban Okrug, Near the Village of Pongaguba | 65.0442°N, 30.3567°E | 18.07.2023 – 19.07.2023 |

| 13 | 60 | Aedes diantaeus Howard, Dyar et Knab, 1913 | Muezersky District, Western shore of Lake Leksozero | 63.7898°N, 30.8640°E | 15.07.2023 - 17.07.2023 |

| 14 | 40 | Aedes cinereus Meigen, 1818 | Loukhsky District, Paanajärvi National Park | 66.2437°N, 30.5639°E | 25.06.2024 |

| 15 | 40 | Simulium reptans (Linnaeus, 1758); S. truncatum (Lundström, 1911); S. subpusillum Rubtsov, 1940 | Muezersky District, Western shore of Lake Leksozero | 63.7898°N, 30.8640°E | 15.07.2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).