1. Introduction

Mosquitoes are well known to transmit numerous arboviruses causing viral infections in animals and humans, such as West Nile virus (WNV), Zika, Japanese encephalitis, Chikungunya, and dengue viruses [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In recent years, the development of metagenomic approaches has led to the discovery of many novel viruses in invertebrates [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Studying the viromes of different species of mosquitoes has revealed new viruses referred to as Insect-Specific Viruses (ISVs). The viral interference within the ISV group and pathogenic viruses may dramatically change the viral biodiversity in mosquitoes and thereby predetermine the transmission of pathogenic viruses by mosquitoes to animals and humans [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These are viruses belonging to

Peribunyaviridae, Flaviviridae, Reoviridae, and

Togaviridae families, with all of them being a potential source of viral biodiversity for viruses with dual tropism for invertebrate and vertebrate hosts [

7,

17,

18].

Comparing mosquito viromes from different geographical regions revealed their biodiversity, providing new insights into the phylogeography of mosquito-borne viruses [

5,

6,

19,

20]. Generally, such studies are conducted in countries characterized by warm or tropical climates, such as China, Australia, Mozambique, and the USA, where mosquito-borne viral infections are not uncommon. Sindbis, Inco, and West Nile viruses are usually detected and isolated from mosquitoes in the southern regions of Russia [

21,

22]. No systemic information is available for Western Siberia, where it is also possible for mosquito-borne viruses to circulate. This region has a continental climate with long winters and short summers that may limit the biodiversity of mosquito species and mosquito-associated viruses. Only several studies have reported the detection of WNV markers in birds and human cases of West Nile fever in Western Siberia [

22,

23].

In this study, we sought to investigate the biodiversity of mosquito-borne viruses from different mosquito species collected in Western Siberia using metagenomic approaches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mosquito samples

For the study, 3.910 mosquitoes were collected in the Novosibirsk region during the spring-summer period of 2017–2018. The collection sites were selected in typical mosquito habitats in Western Siberia (

Figure 1.): deciduous and mixed forests with well-developed grassy cover, deforestations with a natural resumption of hardwoods, and stream banks. The mosquitoes were collected using a light trap [

https://survinat.ru/2011/09/metodika-sborov-xraneniya-i-izucheniya-komarov/]. The capture was conducted after sunset. The mosquitoes were transported in a thermal bag, on a damp napkin, at a temperature of 4

°C and stored at minus 18–24

°C. The fragments of the 16S rRNA and COI gene of the mitogenome were sequenced to determine the mosquito species [

11]. The pools of 10–40 mosquitoes were formed using the data on mosquito species and the time of collection.

2.2. Sample preparation

All the mosquitoes were washed in 70% ethanol and then twice in water, followed by homogenization to remove potential surface microorganisms. The homogenization of the samples was performed mechanically by grinding in a mortar with 300 µl of sterile saline. The homogenates were centrifuged at 8,000 g for 5 minutes at 4

°C, and the supernatants were used for the analysis. The total RNA was extracted using Extract RNA reagent (Eurogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and purified on Cleanup Mini spin columns (Eurogen, Russia). The pools were then processed by benzonaze [

24]. The first chain of cDNA was synthesized using the NEBNext Ultra Direction module. The second cDNA chain was synthesized using the UMI Second Strand Synthesis module (Illumina, Lexogen).

2.3. NGS sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The dsDNA libraries were prepared and analyzed by NGS on MiSeq using the Illumina technology. Cutadapt (version 1.18) and SAMtools (version 0.1.18) were used to remove Illumina adapters and re-read. The contigs were assembled de novo using the MIRA assembly (version 4.9.6). The experimentally determined sequences were deposited in GenBank. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) sequences from GenBank with amino acid identity > 20%. The sequences were aligned, and phylogenetic trees were built in Vector NTI Advance 11, MEGA 7/10 (PSU, USA), and Lasergen 7 (Invitrogen). The resulting viral sequences and sequence read archive (SRA) were deposited in GenBank. The phylogenetic trees were calculated by the maximum likelihood method using 500 replicates for bootstraps values.

3. Results

3.1. Mosquito species

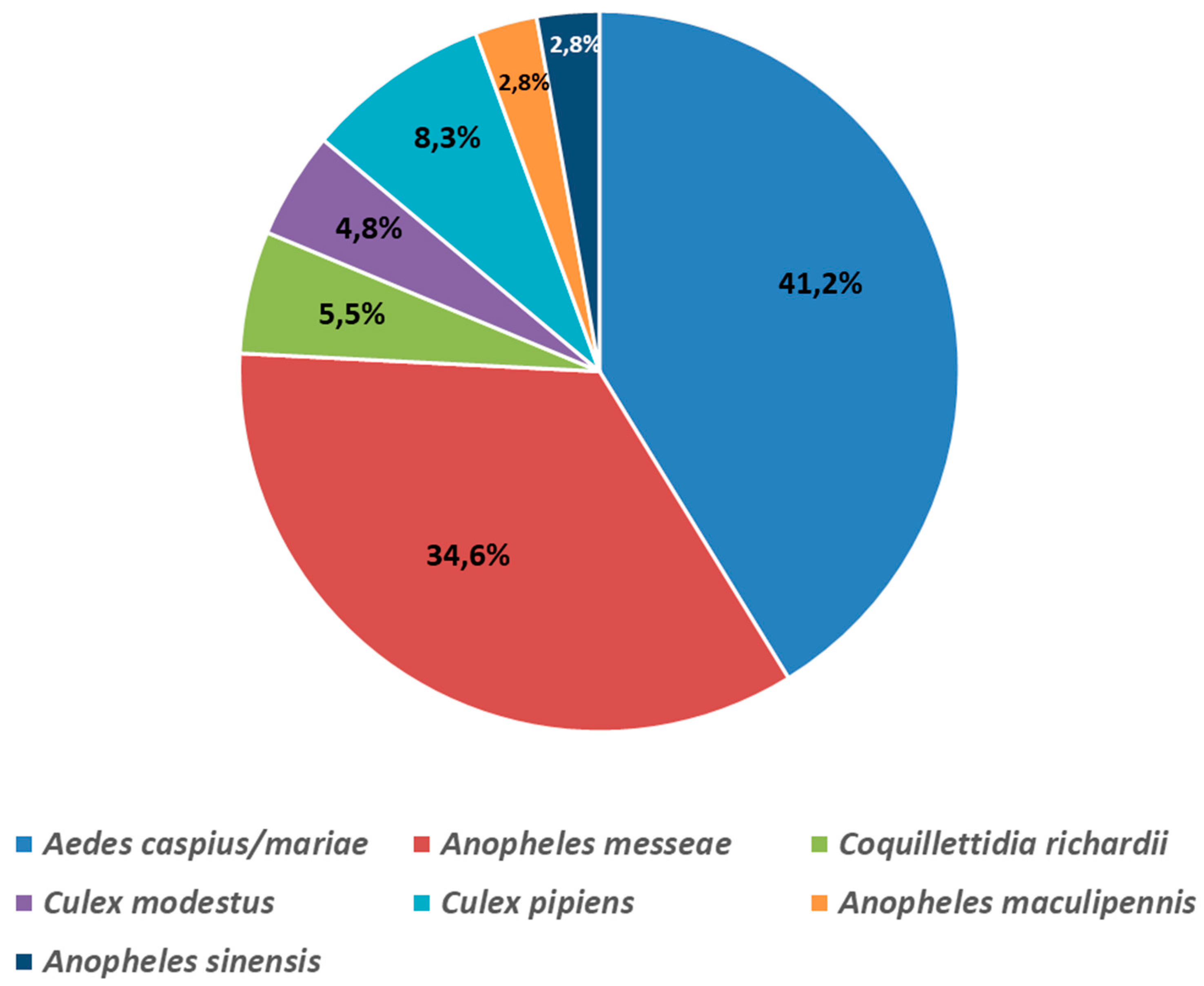

A total of 3,910 mosquitoes were collected in the Novosibirsk suburbs and Novosibirsk region rural district in 2017–2018. The pools of 10–40 mosquitoes were formed to identify the mosquito species for every collection point. The fragments of the 16S rRNA and COI gene of the mitogenome were sequenced to determine the species of mosquitoes (

Figure 2).

Aedes caspius (Pallas, 1771) and

Ae. mariae (Sergent and Sergent, 1903) were found to be the most abundant species, making up to 41.2% of the total.

Anopheles messeae (Falleroni, 1926) accounted for 34.6%,

Culex pipiens (Linnaeus, 1758) for 8.3%,

Coquillettidia richardii (Ficalbi, 1889) for 5.5%,

C. modestus (Ficalbi, 1889) for 4.8%,

An. maculipennis (Meigen, 1818), and

An. sinensis (Wiedemann, 1828) for 2.8%.

3.2. NGS sequencing

One hundred forty-four putative viral sequences were selected in the first step, and of these, 30 sequences with lengths greater than 1239 bp were chosen. Eight sequences with a level of identity > 80% aa) have been previously described as mosquito-borne viruses (

Table 1). These are Partitivirus-like 1 (dsRNA,

Partitiviridae), Hammarskog tombus-like virus (ssRNA (+),

Tombusviridae), Hammarskog picorna-like virus (ssRNA (+),

Picornavirales, unclassified), Lymantria dispar iflavirus 1 (ssRNA (+) viruses,

Iflavirus), Wenzhou noda-like virus 6 (ssRNA (+) viruses, unclassified), Mayapan virus (ssRNA (+), 2 segments, Sanxia permutotetra-like virus 1 (ssRNA (+) viruses, unclassified), Chaq virus-like 1 (RNA viruses, unclassified). Other 22 viral sequences are presented as putative mosquito-borne sequences, with a level of identity less than 79% for viral prototype sequences.

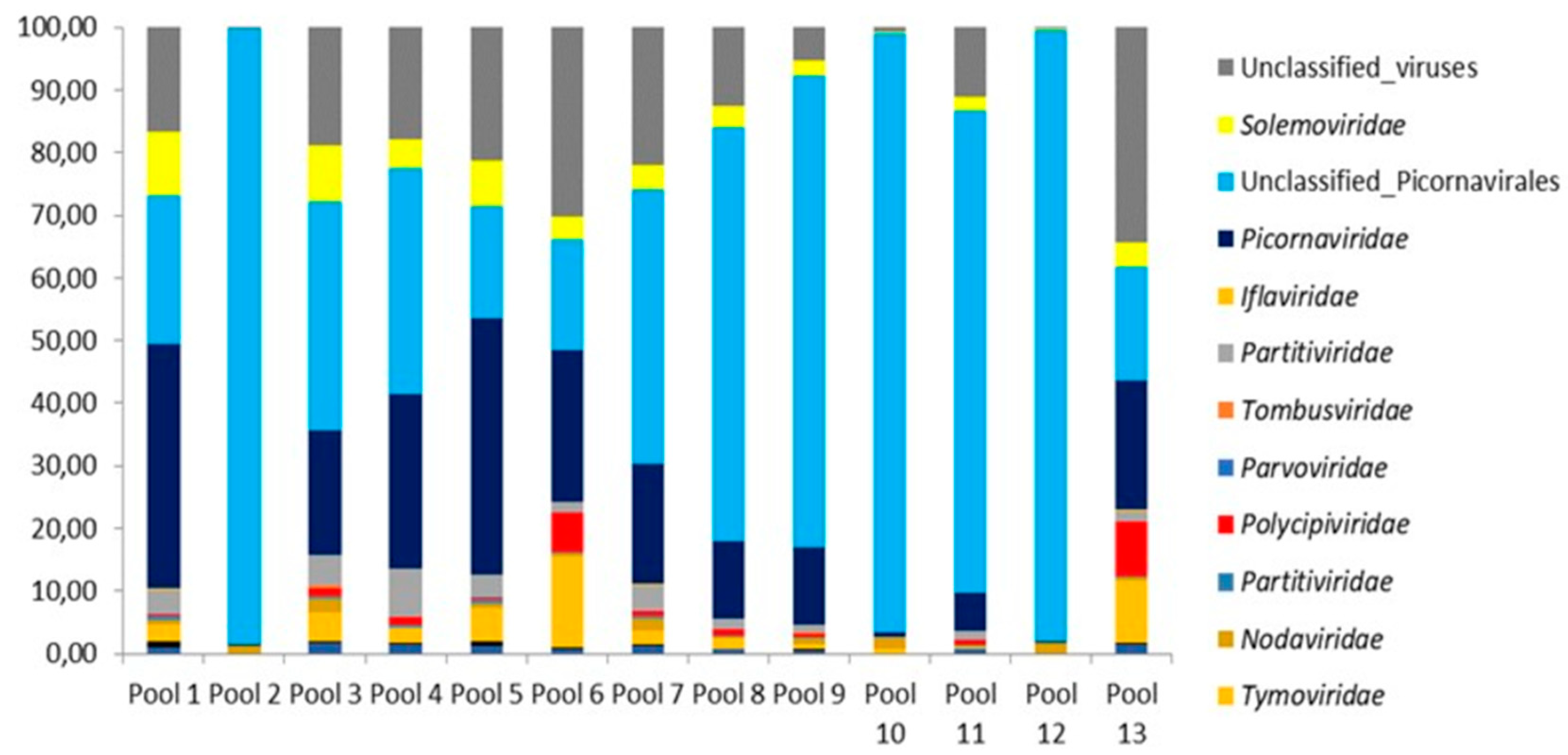

The proportions for classified and unclassified viral reads are presented for 13 mosquito pools (

Figure 3). The prevalence of unclassified and classified picornaviruses was detected practically in all studied pools. Unclassified viral sequences were also analyzed, ranging from 0.13 to 34.27% for the different pools.

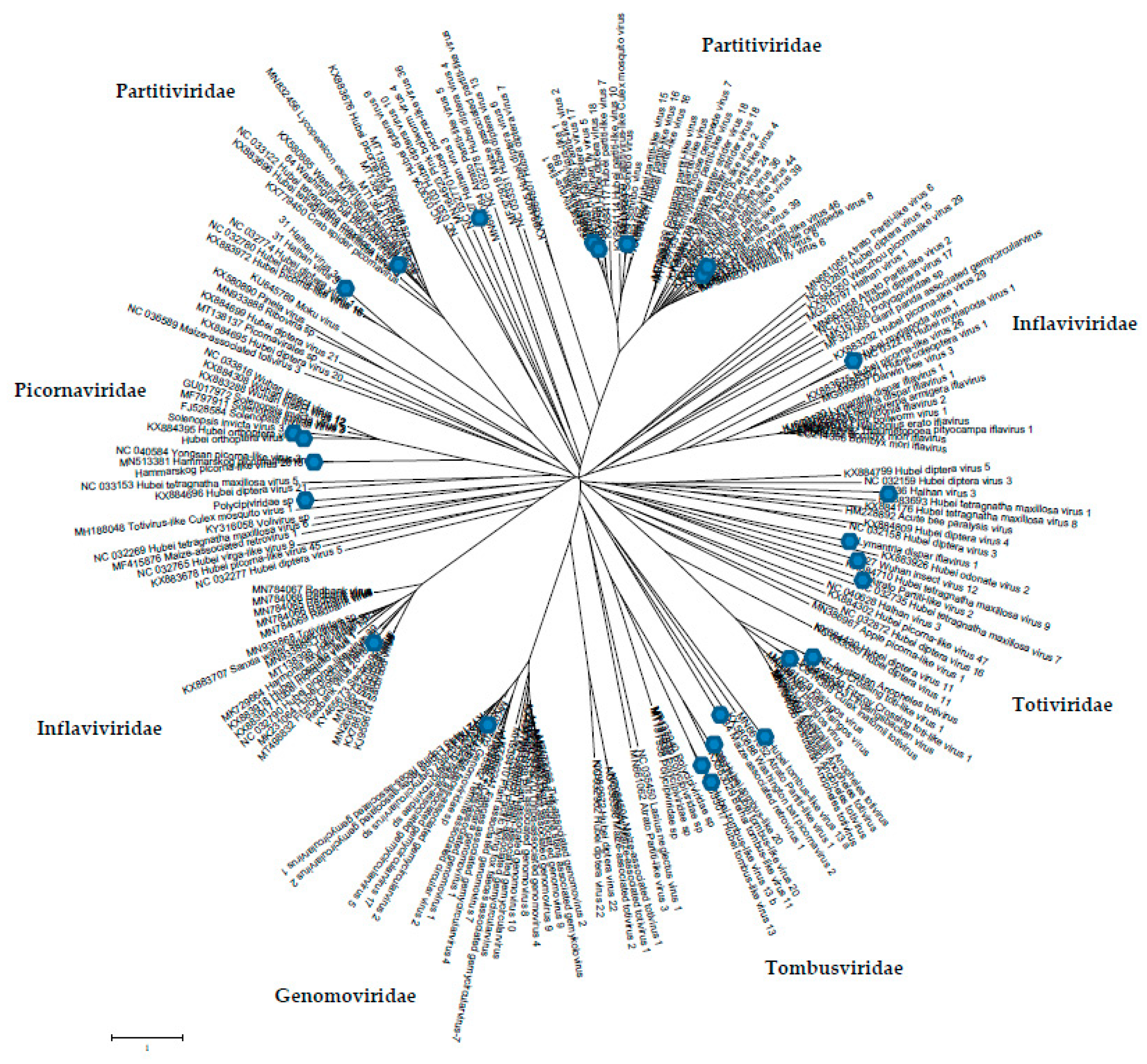

The phylogenetic analysis results for the sequences obtained from mosquitoes are presented in

Figure 4. This phylogeny is based on an amino acid sequence of RdRp, with these data confirming the virome biodiversity of mosquito viruses in nature.

3.2.1. Tymovirales (positive ssRNA)

The complete viral genome tymovirus-like sequence with a 60% identity (according to amino acid sequence) with the previously described Insect-associated tymovirus 1 in Mexico (MN203215) was detected in the

Cq. richardii mosquitoes. This virus has been designated as Inya insect-associated virus 1 (MW251313, MW251314). The genomic positive ssRNA of the Inya insect-associated virus was identified to comprise 6526 bp and three ORF-encoding proteins (

Figure S1). ORF MP of Inya insect-associated virus 1 is RdRp, and this ORF contains a highly conservative "tymobox" near the 5’-end [

25]. The tymobox sequence has 16 nucleotides that are likely part of the subgenomic promoter for the third ORF encoding the coat protein (CP). Previously, the

Tymovirales were well-known as plant viruses [

26]. Inya insect-associated virus 1 can be presumably identified taxonomically by the order

Tymovirales, unclassified

Tymovirales.

3.2.2. Partitiviridae (dsRNA)

Partitivirus-like 1 was detected in

Cq. richardii with an identity level of 89% with an isolate from

Anopheles gambiae collected in Liberia (KX148575). Another novel putative partitivirus was detected in the pool of

Cq. richardii mosquitoes (

Figure S2) and was designated as Krahall insect-associated virus 1 and 2 with an identity level of 60–63% with previously described Atrato Partiti-like virus 2 isolated earlier from

Anopheles darlingi in Colombia (MN661058). In addition, seven suspected partitiviruses were found in the pool of

Cq. richardii mosquitoes. These are: novel insect Talaya 1 and 2 viruses (MW251327–MW251330), with a 68–71% aa identity with previously described Partitivirus-like 1 (Liberia, KX148575); Tarbrook virus (MW251325) with 79% homology with the previously described Sonnbo virus in Sweden (MK440649); Zeyabrook partiti-like_viruses 1 and 2 having similarity of 38–42% with Beihai partiti-like virus 2 (NC_032500) from China. All the prototype sequences were isolated earlier from invertebrates (mollusks, octopuses, mosquitoes, and odonatos). These partitiviruses were preliminarily taxonomically identified as the family

Partitiviridae, unclassified

Partitiviridae.

3.2.3. Totiviridae (monopartite dsRNA)

We have found a novel putative totivirus designated as Zyryana toti-like virus 2 with the prototype Fitzroy Crossing toti-like virus 1 isolated earlier from

Culex annulirostris in Australia (MT498830) (

Table 1). Zyryana toti-like virus 2 with a 51% identity with prototype sequence was detected in the pools of

An. Messeae and

Cq. richardii mosquitoes. The length of the nucleotide sequence of the Zyryana toti-like virus 2 was over 5863 bp, and the ORFs encode two proteins 1112 aa and 807 aa of CP and RdRp. The putative genome organization schemes for these totiviruses are presented in

Figure S3.

3.2.4. Tombusviridae (positive ssRNA).

Tombusviridae (Tolivirales, Tombusviridae) are single-stranded RNA (+) genomes between 3.7 and 4.8 kb in length, currently regarded as plant viruses with a relatively limited host [

27]. We presented the complete polyprotein (4317 bp) for Hammarskog tombus-like virus with 90% identity with a similar virus detected in Sweden (MN513379) and isolated from

Cq. Richiardii in 2017. The 4166 bp partial polyprotein contains three ORF-encoded hypothetical polypeptides: 397 aa, 482 aa, and 409 aa that differ for Hubei tombus-like 20 (

Figure S4). In addition, we found a novel Oyosh tombus-like virus, with 62% identity with Hubei tombus-like virus 13 (NC033017) isolated from house centipedes in China. Four polypeptides are encoded by a prototype genome (5904 bp). The RdRp for

Tombusviridae was translated using a potential alternative mechanism to suppress the stop-codon reading mechanism with the formation of a full-size protein with an elongated C-end of ORF1 [

6].

3.2.5. Picornavirales (positive ssRNA)

Most members of the order Picornavirales have a single molecule of positive sense RNA ranging in length between 7,000 and 12,500 nt. The viral RNA is infectious and serves as a template for replication and mRNA [

28]. Six different picorna-like viruses were identified as mosquito-associated viruses in Western Siberia (

Table 1). We have assembled a complete genome for the Hammarskog picorna-like virus (11507 bp) from

Cq. richardii mosquito that has five OFR encoding 175 aa, 156 aa, 121aa, 376 aa, and 2424 aa polypeptides with 98% aa identity with the previously described Hammarskog picorna-like virus (MN513381) isolated from

Cq. richiardii in Sweden (

Figure S5). In addition, other novel picorno-like viruses were found in

Cq. richardii mosquitoes collected in the Novosibirsk region. These are Miltyush picorna-like viruses 1 and 2, Isses picorna-like virus, Ichacreek insect virus, and polycipiviridae associated with Ora rivulet insects.

Miltyush picorna-like virus was found to have only 36% identity with the previously detected Halhan virus 3 from Haliotis discus hannai in Korea (NC040628). Isses picorna -like virus 1 was found to have 64% identity with previously discovered Washington bat picornavirus in the USA (KX580885). Ichacreek insect virus 3 was identified to have a 44% level of identity with the previously detected Solenopsis invicta virus 3 (GU017972) from Solenopsis invicta in Argentina. Ora rivulet insect-associated polycipiviridae was identified to have a 34% identity level with the previously discovered Polycipivirida sp. isolated from Pteropus lylei in Cambodia (MK161350). The preliminary taxonomic identification for these six viruses is Picornavirales, unclassified Picornavirales.

3.2.6. Iflaviridae (positive ssRNA)

The order Picornavirales also includes some iflaviruses that were found in Cq. richardii mosquito in this study. Lymantria dispar iflavirus 1 was detected with its sequence having 99% identity with already known viral isolates in USA and Russia (KJ629170, MN938851). The alignment and phylogenetic analysis revealed a high sequence identity with the representatives of Iflavirus, the family Iflaviridae (data not shown).

3.2.7. Nodaviridae (Bi-partite positive-sense, ssRNA)

We have assembled practically the whole genome for Wenzhou noda-like virus 6 from

Cq. richardii mosquito and Mayapan virus with 87 and 90% identity levels, respectively. Previously, the sequence of the Wenzhou noda-like virus 6 was identified in

Channeled applesnail in China (KX883260) and Mayapan virus (MH719096) isolated from the

Psorophora ferox mosquito in Nexico (

Figure S6). Other novel nodaviruses were also found in

Cq. richardii mosquitoes collected in the Novosibirsk region. These are Mayzas noda-like virus RNA 2 with a prototype Mayapan virus RNA2 segment (MH719097) with a 43% identity with that isolated from

Psorophora ferox mosquito in Mexico and the insect-associated Uzakla virus with a prototype Mosinovirus (KJ632942) with a 36% identity and isolated from

Culicidae spp. in Cote d’Ivoire.

3.2.8. Permutotetraviridae (dsRNA)

The genomic RNA for permutotetraviruses is 4,582 bp long and encodes three ORFs overlapping in a short region (

Figure S7). The longest ORF (1028 aa) encoding RdRp overlaps with 106 nucleotides with a small ORF (199 aa), presumably encoding the capsid protein. Like all permutotetraviruses, the sequences from

Cq. richardii mosquito pools showed the presence of the virus with a 93% identity with previously detected Sanxia permutotetra-like virus 1 in water striders in China (KX883450). The Uzakla mosquito-associated permutotetra-like virus with a 53% identity to Vespa velutina permutotetra-like virus 2 in France (MN5650551, MN565052) was early described as unclassified Permutotetraviridae.

3.2.9. Other viruses and viral sequences

Two variants of Chaq virus-like 1, Tartas insect associate virus, ZeyaBrook chaq-like virus 2, Kamenka insect-associated virus, and Uzakla insect virus were detected in Cq. richardii. The Chaq virus-like 1 has 82% identity with an earlier described unclassified sequence from Anopheles gambiae in Liberia (KX148554). The ZeyaBrook chaq-like virus 2, Kamenka insect-associated virus, and Uzakla insect virus have a 33–47% identity with the previously unclassified putative viral sequences (KX148556, KX883594, and NC032218) isolated from invertebrates. Only the Tartas insect associate virus may be classified as unclassified Solemoviridae with prototype Atrato Sobemo-like virus 6 (MN661101) with a 61% identity detected in Wyeomyia spp. mosquitoes in Colombia. The Solemoviridae have a relatively small (4–4.6 kb) positive-sense, single-stranded, monopartite RNA genome with 4–5 ORFs, and they are usually associated with plant viruses.

4. Discussion

The application of the metagenomic approach offers novel opportunities for virome analysis [

5,

7,

20]. This approach has provided new insights into the evolution of viruses of clinical importance and has allowed new viruses to be discovered from different viral families such as

Peribunyaviridae [

5],

Rhabdoviridae [

29],

Orthomyxoviridae [

7,

30],

Flaviviridae [

31] and

Reoviridae [

32], as well as unclassified

Chuvirus [

7], and

Negevirus [

33]. Recent metagenomic studies have also confirmed the presence of dengue virus, Zika virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus in mosquitoes in China [

34,

35].

Numerous genetically diverse viruses have also been detected by NGS sequencing in plants, invertebrates and vertebrates in tropical countries [

7,

8]. Phylogenetic analysis has demonstrated that it is possible for all host species and viruses to co-evolve by changing hosts. Mosquitoes are among the most common and important viral vectors of the Zika, dengue, yellow fever, and West Nile viruses that are associated with unprecedented global outbreaks of these infectious in tropical countries [

36,

37]. In addition, mosquitoes are also known to carry insect-specific viruses. Although not directly affecting humans and animals, these viruses can modulate the transmission of pathogenic viruses to vertebrates [

38,

39]. The growth of tourism and trade has also led to an intensive exchange of viral pathogens and their vectors in different geographic regions. Together with the rapid growth of large cities in tropical countries, these are the basis for outbreaks or/and epidemics for mosquito-borne infections among animals and humans, with the environment to maintain the transmission of zoonotic infectious [

40]. In addition, viruses have extraordinary evolutionary potential to generate new pathogenic isolates that can cause severe diseases in humans and/or animals.

The south of the Western Siberian Plain is characterized by a continental climate, with short warm summers and long winters, uniform humidity, and rather abrupt changes in all-weather components over relatively short periods of time [

41]. This region has experienced characteristic negative mean annual temperatures during the last century, with the maximum variations of the mean annual temperature being 3.6 °C over the observation period. The activity season for different species of mosquitoes begins when the ambient temperature rises above 0 °C (early May) and ends in late August or early September, depending on the year. The maximum duration of the mosquito activity period is approximately four to five months. Seventeen species of mosquitoes were earlier found in the forest-steppe and steppe zones of the region [

42]. The mosquito species composition from different foci can drastically vary. For example, the C

q. richardii concentrations can vary from 1.7 to 99.5%, with this species usually dominating in the main forest-steppe and steppe landscapes of the rural part of the Novosibirsk region.

In this study, we used a metagenomic sequencing method to identify the viromes in seven mosquito species collected in the vicinity of Novosibirsk. The metagenomic approach was used to identify the viral diversity in randomly collected mosquitoes. We have identified 30 coding complete viral genomes and viral-like partial sequences of capsid proteins and/or RdRp from mosquitoes (

Table 1). These sequences were classified as putative members of orders:

Tymovirales and

Picornavirales, families:

Partitiviridae, Totiviridae, Tombusviridae, Iflaviridae, Nodaviridae, Permutotetraviridae, Solemoviridae, and four unclassified RNA-viruses. The previously described Partitivirus-like 1, Hammarskog tombus-like virus, Hammarskog picorna-like virus, Lymantria dispar iflavirus 1, Wenzhou noda-like virus 6, Mayapan virus, Sanxia permutotetra-like virus 1, and Chaq virus-like 1 were identified as practically complete genomes with an 82–99% level of identity in

Cq. richardii mosquito. These viruses were earlier found in Liberia (West Africa), Sweden (North Europe), the USA (America), China (Asia), and Mexico (Central America). These findings allow us to hypothesize that these viruses may be widely distributed on a global scale.

Some novel putative viruses and viral sequences have prototype viral sequences with 31% to 79% identity levels, with these prototypes also found in invertebrates from almost all continents. Some of them are associated with different species of mosquitoes. In our study, the main parts of novel viruses were associated with

Cq. richardii mosquito, with this species widespread in the south of Western Siberia [

42]. The role of this mosquito species in the spread of human viral infections in Siberia has not been studied virtually, suggesting that our knowledge concerning mosquito-associated viruses in North Eurasia is very limited and requires further study.

5. Conclusions

We have identified novel and known viral genomes and viral-like partial sequences in mosquitoes collected in the Novosibirsk region of Western Siberia. They were classified as novel putative viruses using the bioinformatics analysis of partial sequences of capsid proteins and RdRp or whole polyproteins (genomes) within the orders Tymovirales and Picornavirales, the families Partitiviridae, Totiviridae, Tombusviridae, Iflaviridae, Nodaviridae, Permutotetraviridae, and Solemoviridae, and four unclassified RNA-viruses. We believe that the virus identification will enhance our understanding of the transmission of RNA viruses by mosquitoes in North Asia. We hope that the discovery and observation of these mosquito-borne viruses can help prevent future outbreaks of viral infections in the region under study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Andean potato mild mosaic virus (APMMV) as a novel Inya insect-associated virus 1 and 2; Figure S2: A novel virus with a 51% identity to Atrato Partiti-like virus 2 was detected in the Anopheles messeae pool and referred to as the Krahall insect-associated virus; Figure S3: The scheme of genome organization for Fitzroy Crossing toti-like virus 1; Figure S4: The scheme of genome organization for Tombus-like virus; Figure S5: The genome organization for the picorna-like virus; Figure S6: The genome organization for nodaviruses (ssRNA); Figure S7: The genome organization for permutotetraviruses.

Author Contributions

V.A.T., A.N.S., M.Y.K., E.P.P., A.V.G., and V.B.L. designed the experiments and analyzed the data; A.N.S., M.Y.K., E.P.P., N.L.T., R.B.B., A.V.G., T.P.M., and T.V.T. performed the experiments; V.A.T., and V.B.L. management of the investigation and obtained funds; V.A.T. and V.B.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the presented version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreements No. 075-15-2019-1665).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this study. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rizzoli, A.; Jimenez-Clavero, M.A.; Barzon, L.; Cordioli, P.; Figuerola, J.; Koraka, P.; Martina, B.; Moreno, A.; Nowotny, N.; Pardigon, N.; Sanders, N. ; Ulbert, S,; Tenorio, A. The challenge of West Nile virus in Europe: Knowledge gaps and research priorities. Euro Surveill. 2015, 20, 21135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A.S.; Morens, D.M. Zika Virus in the Americas—Yet Another Arbovirus Threat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.A.; Dermody, T.S. Chikungunya virus: Epidemiology, replication, disease mechanisms, and prospective intervention strategies. J Clin Investig. 2017, 127, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Scott, T.W.; Zou, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Duda, K.A.; Bhatt, S.; Katzelnick, L.; Howes, R.E.; Battle, K.E.; Simmons, C.P.; Hay, S.I. Global spread of dengue virus types: Mapping the 70 year history. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.D.; Tian, J.H.; Chen, L.J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.X.; Qin, X.C.; Li, J.; Cao, J.P.; Eden, J.S.; Buchmann, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature 2016, 540, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Altan, E.; Deng, X.; Barker, C.M.; Fang, Y.; Coey, L.L.; Delwart, E. Virome of >12 thousand Culex mosquitoes from throughout California. Virology 2018, 523, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.H.; Lin, X.D.; Kang, Y.J.; Chen, L.J.; Qin, X.C.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Zhang, Y.Z. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. Elife 2015, 4, e05378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, K.G.; Biser, T.; Hamilton, T.; Santos, C.J.; Pimentel, G.; Mokashi, V.P.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A. Bioinformatic Characterization of Mosquito Viromes within the Eastern United States and Puerto Rico: Discovery of Novel Viruses. Evol Bioinform Online 2016, 12(S2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junglen, S.; Drosten, C. Virus discovery and recent insights into virus diversity in arthropods. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013, 16, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.L.; Longdon, B.; Lewis, S.H.; Obbard, D.J. Twenty-Five New Viruses Associated with the Drosophilidae (Diptera). Evol Bioinform Online. 2016, 12(S2), 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolling, B.G.; Olea-Popelka, F.J.; Eisen, L.; Moore, C.G.; Blair, C.D. Transmission dynamics of an insect-specific flavivirus in a naturally infected Culex pipiens laboratory colony and effects of co-infection on vector competence for West Nile virus. Virology 2012, 427, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson-Peters, J.; Yam, A.W.; Lu, J.W.; Setoh, Y.X.; May, F.J.; Kurucz, N.; Walsh, S.; Prow, N.A.; Davis, S.S.; Weir, R.; Melville, L.; Hunt, N.; Webb, R.I.; Blitvich, B.J.; Whelan, P.; Hall, R.A. A new insect-specific flavivirus from northern Australia suppresses replication of West Nile virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus in co-infected mosquito cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e56534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, J.L.; Solberg, O.D.; Langevin, S.A.; Brault, A.C. Characterization of a novel insect-specific flavivirus from Brazil: Potential for inhibition of infection of arthropod cells with medically important flaviviruses. J Gen Virol. 2014, 95 Pt 12, 2796–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goenaga, S.; Kenney, J.L.; Duggal, N.K.; Delorey, M.; Ebel, G.D.; Zhang, B.; Levis, S.C.; Enria, D.A.; Brault, A.C. Potential for Co-Infection of a Mosquito-Specific Flavivirus, Nhumirim Virus, to Block West Nile Virus Transmission in Mosquitoes. Viruses 2015, 7, 5801–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, F.; Erasmus, J.H.; Haddow, A.D.; Tesh, R.B.; Weaver, S.C. Eilat virus induces both homologous and heterologous interference. Virology 2015, 484, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Mendelin, S.; McLean, B.J.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; Hobson-Peters, J.; Hall, R.A.; van den Hurk, A.F. The insect-specific Palm Creek virus modulates West Nile virus infection in and transmission by Australian mosquitoes. Parasit Vectors. 2016, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marklewitz, M.; Zirkel, F.; Kurth, A.; Drosten, C.; Junglen, S. Evolutionary and phenotypic analysis of live virus isolates suggests arthropod origin of a pathogenic RNA virus family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015, 112, 7536–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crochu, S.; Cook, S.; Attoui, H.; Charrel, R.N.; De Chesse, R.; Belhouchet, M.; Lemasson, J.J.; de Micco, P.; de Lamballerie, X. Sequences of flavivirus-related RNA viruses persist in DNA form integrated in the genome of Aedes spp. mosquitoes. J Gen Virol. 2004, 85(Pt 7), 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholleti, H.; Hayer, J.; Abilio, A.P.; Mulandane, F.C.; Verner-Carlsson, J.; Falk, K.I.; Fafetine, J.M.; Berg, M.; Blomstrom, A.L. Discovery of Novel Viruses in Mosquitoes from the Zambezi Valley of Mozambique. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e0162751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Neville, P.; Nicholson, J.; Eden, J.S.; Imrie, A.; Holmes, E.C. High-Resolution Metatranscriptomics Reveals the Ecological Dynamics of Mosquito-Associated RNA Viruses in Western Australia. J Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternovoĭ, V.A.; Shchelkanov, M.Iu.; Shestopalov, A.M.; Aristova, V.A.; Protopopova, E.V.; Gromashevskiĭ, V.L.; Druziaka, A.V.; Slavskiĭ, A.A.; Zolotykh, S.I.; Loktev, V.B.; L’vov, D.K. [Detection of West Nile virus in birds in the territories of Baraba and Kulunda lowlands (West Siberian migration way) during summer-autumn of 2002]. Vopr Virusol, 2004; 49, 52–56. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Korobitsyn, I.G.; Moskvitina, N.S.; Tyutenkov, O.Y.; Gashkov, S.I.; Kononova, Y.; Moskvitin, S.S.; Romanenko, V.N.; Mikryukova, T.P.; Protopopova, E.V.; Kartashov, M.Y.; Chausov, E.V.; Konovalova, S.N.; Tupota, N.L.; Sementsova, A.O.; Ternovoi, V.A.; Loktev, V.B. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in wild birds and their ticks in Western Siberia and high level of their mismatch. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2021; 68, 2021.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternovoĭ, V.A.; Protopopova, E.V.; Kononova, Iu. .; Ol’khovikova, E.A.; Spiridonova, E.A.; Akopov, G.D.; Shestopalov, A.M.; Loktev, V.B. [Cases of West Nile fever in Novosibirsk region in 2004, and the genotyping of its viral pathogen]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2007; (1), 21–26. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, M.A.; Wilkinson, E.; Vallari, A.; McArthur, C.; Sthreshley, L.; Brennan, C.A.; Cloherty, G.; de Oliveira, T. Sensitive Next-Generation Sequencing Method Reveals Deep Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Virol. 2017, 91, e01841–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.W.; Howe, J.; Keese, P.; Mackenzie, A.; Meek, D.; Osorio-Keese, M.; Skotnicki, M.; Srifah, P.; Torronen, M.; Gibbs, A. The tymobox, a sequence shared by most tymoviruses: its use in molecular studies of tymoviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuze, J.; Koenig, R.; De Souza, J.; Vetten, H.J.; Muller, G.; Flores, B.; Ziebell, H.; Cuellar, W. The complete genome sequences of a Peruvian and a Colombian isolate of Andean potato latent virus and partial sequences of further isolates suggest the existence of two distinct potato-infecting tymovirus species. Virus Res. 2013, 173, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhlund, P.; Hayer, J.; Lundén, H.; Hesson, J.C.; Blomström, A.L. Viromics Reveal a Number of Novel RNA Viruses in Swedish Mosquitoes. Viruses. 2019, 11, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanborn, M.A.; Klein, T.A.; Kim, H-C. ; Fung, C.K.; Figueroa, K.L.; Yang, Y.; Asafo-Adjei, E.A.; Jarman, R.G.; Hang, J. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals Three Novel and Prevalent Mosquito Viruses from a Single Pool of Aedes vexans nipponii Collected in the Republic of Korea. Viruses 2019, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J.; Firth, C.; Widen, S.G.; Blasdell, K.R.; Guzman, H.; Wood, T.G.; Paradkar, P.N.; Holmes, E.C.; Tesh, R.B.; Vasilakis, N. Evolution of genome size and complexity in the Rhabdoviridae. PLoS Pathog, 2015, 11, e1004664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presti, R.M.; Zhao, G.; Beatty, W.L.; Mihindukulasuriya, K.A.; da Rosa, A.P.T.; Popov, V.L.; Wang, D. Quaranfil, Johnston Atoll, and Lake Chad viruses are novel members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. J Virol. 2009, 83, 11599–11606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, Y.; Atoni, E.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z. Mosquito-associated viruses in China. Virol Sin. 2018, 33, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attoui, H.; Jaafar, F.M.; Belhouchet, M.; Tao, S.; Chen, B.; Liang, G.; de Lamballerie, X. Liao ning virus, a new Chinese seadornavirus that replicates in transformed and embryonic mammalian cells. J Gen Virol, 2006, 87 Pt 1, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakis, N.; Forrester, N.L.; Palacios, G.; Nasar, F.; Savji, N.; Rossi, S.L.; Guzman, H.; Wood, T.G.; Popov, V.; Gorchakov, R.; González, A.V.; Haddow, A.D.; Watts, D.M; da Rosa, A.P.; Weaver, S.C.; Lipkin,W. I.; Tesh, R.B. Negevirus: A proposed new taxon of insect-specific viruses with wide geographic distribution. J Virol. 2013, 87, 2475–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Guo, X.; Wen, S.; Tian, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Ren, J.; Zhou, H.; Lu, H.; Jin, N. Metagenomic Analysis of Flaviviridae in Mosquito Viromes Isolated From Yunnan Province in China Reveals Genes From Dengue and Zika Viruses. Fron Cell Infect Microbiol, 2018; 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klungthong, C.; Gibbons, R.V.; Thaisomboonsuk, B.; Nisalak, A.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Thirawuth, V.; Jarman, R.G. Dengue virus detection using whole blood for reverse transcriptase PCR and virus isolation. J Clin Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2480–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBeaud, A.D.; Bashir, F.; King, C.H. Measuring the burden of arboviral diseases: The spectrum of morbidity and mortality from four prevalent infections. Popul Health Metr. 2011, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.A.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; McLean, B.J.; O’Brien, C.A.; Colmant, A.M.; Piyasena, T.B.; Harrison, J.J.; Newton, N.D.; Barnard, R.T.; Prow, N.A.; Deerain, J.M.; Mah, M.G.; Hobson-Peters, J. Commensal Viruses of Mosquitoes: Host Restriction, Transmission, and Interaction with Arboviral Pathogens. Evol Bioinform Onlne. 2017, 12, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilakis, N.; Tesh, R.B. Insect-specific viruses and their potential impact on arbovirus transmission. Curr Opin Virol. 2015, 15, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E.; Pettersson, J.; Higgs, S.; Charrel, R.; de Lamballerie, X. Emerging arboviruses: Why today? One Health, 2017, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 40. Powers, A M.; Waterman, S.H. A decade of arboviral activity - lessons learned from the trenches. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. [CrossRef]

- Joganzen, B.G. , Petkevich A.N. Acclimatization of fish in Western Siberia. Proc. Baraba branch VNIORKH. 1951, 5, 3–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kononova, Iu.V.; Mirzaeva, A.G.; Smirnova, Iu.A.; Protopopova, E.V.; Dupal, T.A.; Ternovoĭ, V.A.; Iurchenko, Iu.A.; Shestopalov, A.M.; Loktev, V.B. [Species composition of mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) and possibility of the West Nile virus natural foci formation in the South of Western Siberia]. Parazitologiia. 2007; 41, 459–470. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).