1. Introduction

Tabanidae (Diptera) is a cosmopolitan family, with members mostly being nuisance pests for people and livestock because of their painful bite and persistent biting behavior [

1]. The Tabanidae family is more diverse than any other haematophagous insect family and includes more than 4000 described species [

2,

3]. In Russia, 114 species are described, with six genera being the most represented:

Tabanus,

Atylotus,

Heptatoma,

Chrysops,

Haematopota and

Hybomitra [

4].

Adult tabanids are fast fliers and can cover a distance of up to 2 km daily. Both males and females use sugars of plant origin, such as nectar, to provide energy for flight. Most females seek a blood meal after mating in order to produce eggs, with the size of blood meal varying from 20 μl for small species up to 600 μl for larger species [

1].

Pastured cattle, wildlife species and even humans suffer from tabanids attacks. In addition to blood loss from feeding, tabanids cause extreme annoyance. Large numbers of tabanids in the area can reduce weight gain and milk production of the cattle. For instance, in French Guiana, the mean daily weight gain for cattle during the season of horsefly activity is 418 grams, which is 327 grams less than the annual average [

5]. In Russia, authors report losses of up to 30% in milk production and reductions of as much as 45% in weight gained during tabanid season [

4]. Tabanids can cause additional economic losses due to their impact on human outdoor recreational activities, such as trekking, fishing, swimming and camping [

1].

Tabanid biology and feeding behavior make them suitable vectors for the transmission of viral, bacterial and other pathogens [

1,

5]. The transmission of filarial nematodes

Loa loa [

6],

Elaeophora schneideri [

7],

Dirofilaria roemeri [

8]

, and

Dirofilaria repens, as well as protozoa

Haemoproteus metchnikovi and

Trypanosoma theileri, involves disease agent replication or development within tabanid [

1]. Mechanical transmission by tabanids (primarily

Chrysops spp.,

Hybomitra spp. and

Tabanus spp.) plays a major role in the transmission of equine infectious anemia virus [

1]. Other viruses such as bovine leukemia virus [

1,

9], bovine viral diarrhea virus [

1], and hog cholera virus can also be mechanically transmitted by tabanids; however, this is not a main route of infection for those pathogens [

1]. There are reports of mechanical transmission of

Bacillus anthracis,

Anaplasma marginale (normally biologically transmitted by ticks), and

Francisella tularensis, as well as some other bacterial pathogens. Protozoa pathogen

Besnoitia besnoiti and many species of

Trypanosoma genus can also be mechanically transmitted by various species of tabanids [

1].

Advances in sequencing technologies and bioinformatics have greatly expanded our knowledge of viral biodiversity. Thousands of new viruses were discovered, mostly in arthropods [

10,

11,

12]. Currently, viromes of well-established vector invertebrates, such as mosquitoes [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and ixodid ticks [

18,

19,

20] are being actively studied, while other blood-sucking invertebrates are receiving much less attention. To our knowledge, no specific work dedicated to description of the tabanid virome exists. However, the viromes of five unidentified specimens of tabanids (

Tabanidae sp.) were uncovered during a large-scale insect virome study. As a result, five new viruses were discovered: Wuhan horsefly virus, Jiujie fly virus, Wuhan horsefly virus 3, Hubei picorna-like virus 17, and Hubei toti-like virus 19 [

11].

In this work, we explored the RNA viromes of several species of Hybomitra, Tabanus, Chrysops, and Haematopota genera collected in Russia. Overall, we were able to identify and assemble 14 full coding genomes of novel viruses, 4 partial coding genomes, as well as several fragmented viral sequences, which presumably belong to another 12 new viruses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Pooling of Tabanids

Tabanids were collected manually in 2021 in the Primorye Territory and Ryazan Region, Russia. Tabanids were collected far from areas with large aggregations of livestock. Tabanid species were determined immediately after collection using taxonomy keys [

21,

22]. Species composition of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) pools, location collection, and date of material collection are presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Sample Preparation and High-Throughput Sequencing

Hybomitra spp and

Tabanus spp. were individually homogenized in 700 μl of saline solution and

Chrysops spp. specimens were homogenized in 500 μl of saline solution (FSASI Chumakov FSC R&D IBP RAS, Russia). Homogenization was carried out using Tissue Lyser II for 12 min at 25 s

−1. Equal amounts of individual homogenates were pooled together on the basis of genera and collection site (

Table 1).

RNA isolation, rRNA depletion, library preparation and HTS were carried out as described previously [

23]. All obtained raw reads were deposited in the sequence read archive (BioProject accession number PRJNA1026651).

2.3. High-Throughput Sequencing Assembly and Analysis

Adapter sequences, bases with low quality (< Q30) and short reads (length < 35) were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [

24]. Processed reads were used for de novo contig assembly with SPAdes v3.13.0 using the ‘rnaviral’ option [

25]. The resultant contigs were screened for viral sequences using the blastn algorithm in BLAST v2.9.0+ with the nt database, and contigs containing virus-related sequences were extracted for further investigation [

26].

In some cases, the obtained contigs themselves were additionally reassembled using SeqMan 7.0.0 (DNAstar Inc., Madison, WI, USA). After assembly, open reading frames were extracted from putative viral genome sequences and were tested using the blastp algorithm to detect virus related contigs. Some contigs with very high identities to known human pathogens (sequenced in the same run) were filtered out as possible contaminations.

We identified the closest relatives of each virus sequence using online the blastp algorithm. For each virus sequence with similar closest relative results, an estimation of evolutionary divergence was performed to assess whether they belong to the same virus species.

The abundance of viral reads in each pool was estimated using Bowtie2 v.2.3.5.1 [

27] software as described earlier [

23].

2.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

From the obtained contigs, we extracted either the polyprotein (if available) or RNA-dependent polymerase protein sequence. Homologs of the extracted sequence were extracted from the database performing online blastp searches with default parameters. The obtained sequences were filtered to remove sequences with low length, using custom python script.

Subsequently, these sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.310 [

28] with E-INS-i algorithm and 1000 cycles of iterative refinement. Alignments were processed using the TrimAL v1.4. rev 15 program [

29] in order to remove ambiguously aligned regions with automated region detection (“automated1” option). After that, sequences containing more than 10% of gaps or unknown amino acids were removed from alignments using custom python script. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using the phyML 3.3.20200621 program [

30] with 1000 bootstrap replications. Phylogenetic trees were annotated using custom python script and visualized in FigTree v.1.4.4. Custom python scripts used in the work are available at GitHub (

https://github.com/justNo4b/slepni_scripts).

2.5. Data visualization

Phylogenetic trees were visualized using FigTree v.1.4.4. Genomes of the viruses were drawn using custom Python script (

https://github.com/justNo4b/GenomeDrawing). All post-processing of the images was performed with the GIMP v.2.10.24 program.

2.6. Virus Passages in Cell Lines

Three cell cultures were used in the work: a HAE/CTVM8 cell line [

31], originating from

Hyalomma anatolicum ticks; a C6/36 cell line, originated from

Aedes albopictus mosquitoes; and a porcine embryo kidney (PEK) cell line. The PEK cell line was maintained at 37° C in Medium 199 of Earle’s salts (FSASI Chumakov FSC R&D IBP RAS, Moscow, Russia), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Paisley, UK). The C6/36 was maintained at 32° C in L-15 medium (FSASI Chumakov FSC R&D IBP RAS, Moscow, Russia), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Paisley, UK). The HAE/CTM8 cell line was maintained at 28 °C in L-15 medium, supplemented with 20% FBS, 10% Tryptose Phosphate Broth, 1% L-glutamine and 2 µg/ml ciprofloxacin antibiotic.

Before cell infection, pooled tabanid homogenates were filtered via centrifugation for 15 min at 1500 rcf using Corning Costar Spin-X 0.45 µm centrifuge tube filters (Corning, NY, USA).

For the experiment on the C6/36 and PEK cell lines, cells were seeded in the 96-well cell culture plates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon-si, Korea) and cultivated for one to two days. Then, cells were infected with either 30 μl of pools of tabanids homogenate, or 30 μl of the cultural fluid collected from the previous virus passage, before being incubated in the thermostat at 32°C for the PEK cell line and at 28°C for the C6/36 cell line for 6–7 days. Three passages were performed overall.

For the experiment on the HAE/CTVM8 cell line, cells were seeded in the 96-well cell culture plates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon-si, Korea) and cultivated for seven days. Then, cells were infected with 30 μl of pools of tabanids homogenate and kept in the thermostat at 28°C. Medium was changed at weekly intervals via the removal and replacement of 150 μl.

An additional passaging experiment was performed on pool 7. For this experiment, C6/36 and PEK cells were seeded in flat-sided culture tubes (Nunc, Waltham, MA, USA) in 2.2 mL of growth medium and cultivated for two days. Then, cells were infected with either 200 μl of pools of tabanids homogenate, or 200 μl of the cultural fluid collected from the previous virus passage, and incubated in the thermostat at 32°C for PEK cell line and at 28°C for C6/36 cell line for 6–7 days. Six passages were performed overall.

2.6. Virus Detection After Passages

In order to detect viruses during passages, oligonucleotide pairs were designed for each virus detected via high-throughput sequencing (

Table S1). For detection, total RNA was isolated from samples and reverse transcription was performed using random oligonucleotides, as described earlier [

23]. Then, PCR was performed using cDNA, virus-specific oligonucleotides and DreamTaq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania). The obtained PCR products were analyzed in agarose gel, with bands of target length being extracted from gel. Then, they were purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced with an Applied Biosystems 3500 genetic analyzer (Waltham, MA, USA) using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania). Obtained sequences were analyzed using SeqMan 7.0.0. The sample was counted as positive on a virus if the results were confirmed via sequencing.

2.7. Virus Detection by qPRC

In order to estimate viral load during passages, TaqMan probes were designed for viruses that we were able to detect using PCR. Prior to the RNA isolation procedure, 1 μg of the PEK cells RNA and 2 ×10

4 copies of poliovirus RNA were added to each sample as an internal control. Total RNA was than isolated from samples using TRI reagent LS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was carried out with random oligonucleotides using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Evrogen JSC, Moscow, Russia) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription for the internal control was carried in a separate tube using PVR1 oligonucleotide (

Table S2).

The qPCR was carried out using the R-412 qPCR reaction kit (Syntol, Moscow, Russia) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For each virus, a specific oligonucleotide pair and fluorescent probe were used (

Table S1). Samples were amplified in a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) fluorescent detector. The obtained amplification data were analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager v.3.1 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

The qPCR for the internal control sample was carried out using the same reaction kit and equipment. We employed poliovirus-specific oligonucleotides and a probe to do so (

Table S2).

3. Results

3.1. High-Throughput Sequencing

In the study we processed ten pools of tabanids from two distant regions of Russia: Primorye Territory and Ryazan Region, collected in the 2021. Several species were studies from four genera: Hybomitra, Chrysops, Tabanus, and Haematopota.

We obtained 7–18 million reads per pool after filtration and managed to assemble 15 complete viral coding sequences (

Figure 1,

Table S3). In four more cases, we were able to assemble partial coding sequences of the viruses (with gaps estimated to be less than 10% of the coding sequence). Additionally, we detected genome fragments that may indicate the presence of at least 12 more viruses in the studied samples (

Figure 1,

Table S4). All detected viruses, except for one, were significantly different from those already described in the public databases and thus could be considered novel. All of them were close to various groups of the RNA viruses, including the Negevirus group,

Narnaviridae,

Totiviridae,

Flaviviridae,

Xinmoviridae,

Permutotetraviridae,

Dicistroviridae,

Phasmaviridae,

Solinviviridae,

Rhabdoviridae,

Iflaviridae,

Chuviridae and

Solemoviridae.

The number of viruses in the samples varied greatly. No virus was detected in three pools (Pools 4, 5 and 10), while 10 were detected in pool 7 (Chrysops relictus) and six were detected in pools 6 and 8. Presence of the viral reads was low overall, reaching a maximum at 2.68% in pool 7.

3.2. Negev-like viruses

Negevirus is a genus, proposed by Vasilakis and co-authors [

32]. However, it is still officially unrecognized by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Negeviruses are characterized by single-stranded, positive-sense RNAs with poly(A) tails. The genome of the viruses range in size from 9 to 10 kb and encode three overlapped open reading frames (ORFs). All negeviruses were isolated from mosquitoes and phlebotomine sand flies [

32]. Recently, several similar negev-like were discovered in various insects during virome studies. Many of those discovered have a longer genome size and up to five non-overlapping ORFs [

33,

34].

Here, we report the discovery of three negev-like contigs in our study. These were preset in pool 1 (

Hybomitra brevis), pool 6 (

Haematopota pluvialis) and pool 7 (

C. relictus). These contigs were 11.6–11.9 kb in length, and contained 5 ORFs with an overall layout similar to that of negev-like viruses (

Figure 2B). According to BLAST assessments, all the contigs had quite low similarity (39.2–44.3%) to the closest relatives. Comparison of contigs with each other using a blast program showed that they are only distantly related with each other (68.9–71.2% identity with 51–68% of query cover), suggesting that each contig represents a separate novel negev-like virus (

Table S5). The viruses were named Xanka Hybomitra negev-like virus (XHNV), Melisia Haematopota negev-like virus (MelHNV), and Medvezhye Chrysops negev-like virus (MedCNV). All those viruses had a relatively low abundance in the pools, accounting for 0.01%, 0.23% and 1.08% of the total reads, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that all these viruses formed a single well-supported group (

Figure 2A), with a sister relationship to a clade formed by viruses of fruit flies of the genera

Zeugodacus,

Ceratitis, and

Bactocera [

34]. It should be noted that, within the tabanid clade, MedCNV and MelHNV, both of which are found in tabanids in the Ryazan region, form a well-supported group. However, tabanid phylogenetic trees placed genus

Haematopota and

Hybomitra closer to each other, than to the genus

Chrysops [

3]. Such a situation hints towards the geographically driven evolution of tabanid negev-like viruses.

3.3. Flavi-like virus

Classical

Flaviviridae members are small, enveloped viruses with positive-sense RNA genomes. They are generally 9–13 kb in length. All members lack poly-A tails, and only members of the genus

Orthoflavivirus contain a cap structure. Others instead possess an internal ribosomal entry site. All members encode a single ORF that is processed by viral and cellular proteases into several structural and non-structural proteins. Non-structural proteins contain regions encoding a serine protease, RNA helicase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and the order of these domains is conservative within the family [

35].

Recently, several groups of viruses were discovered with homology to the

Flaviviridae polymerases, and some of them had segmented genomes. One of those groups contained viruses with huge monopartite RNA genomes, up to 30 kb in length [

10,

11]. Those viruses were found in insects, ticks, and even plants [

10,

11,

36,

37].

In this work, we discovered a 20.9 kb contig with homology to the

Flaviviridae polymerase in pool 6 (

Ha. pluvialis). The contig contained a single ORF 6715 aa in length, flanked by untranslated regions on the 5` and 3` ends (

Figure 3B). According to BLAST analysis, the contig had a 41.7% identity with 15% cover to the Orthopteran flavi-related virus. Thus, it represents a novel flavi-like virus, and it was named Medvezhye Haematopota flavi-like virus (MHFV).

MHFV had 0.29% abundance in the pool. Phylogenetic analysis showed (

Figure 3A), that MHFV groups together with the Xingshan cricket virus [

37] (with <70% bootstrap support). Other close relatives (with < 70% bootstrap support) include viruses of the

Culex mosquitoes (Placeda virus [

38], Culex tritaeniorhynchus flavi-like virus [

33]), and

Musca domestica (Shayang fly virus 4 [

37]).

3.4. Xinmo-like virus

The family known as

Xinmoviridae contains single negative-strand RNA viruses 9–14 kb in length, encoding three to six proteins. Viruses within the family have mostly been discovered using HTS in various species of insect, including mosquitoes, parasitoid wasps, flies, dragonflies, and others. The taxonomy of

Xinmoviridae has recently been revised, with several new genera being created [

39].

Here, we found several contigs with a homology to the

Xinmoviridae proteins (

Figure 4B). The first one was found in pool 6 (

Ha. pluvialis) and was 11.5 kb in length. It encoded four ORFs with a typical

Xinmoviridae layout. According to the BLAST, the closest relative was the Hubei diptera virus 11 (

Alasvirus muscae) with a 35.9% aa identity in the polymerase (98% query cover). Such a low identity across the polymerase shows that this contig represents a genome of the novel virus, and it was named Medvezhye Haematopota xinmo-like virus (MHXV).

In mixed pool 8 (

C. pictus/ C. caecutiens), we found two contigs encoding

Xinmoviridae-related proteins. One of them encoded four proteins, including partial polymerase, and the second one encoded approximately 70–80% of the polymerase. After performing a protein alignment of the partial fragments of this contig on MHXV polymerase, we concluded that they are likely to belong to the single virus named Medvezhye Chrysops xinmo-like virus (MCXV), with about 500 nt gap in the polymerase region. This virus polymerase had a 60.1% amino acid identity with the MHXV polymerase (

Table S6) and a 39.2% identity to the closest relative found in the Genbank (98% query cover).

Additionally, in pool 6 (

Ha. pluvialis), there were small 580 nt contig that encoded a part of a

Xinmoviridae-like polymerase; however it was distant to both MHXV and MCXV (

Table S6). Working name of the genome fragment is given in

Table S4.

The abundance of MHXV in the pool was 0.18%, while that of MCXV was 0.01%. Phylogenetic analysis showed that MHXV and MCXV form a monophyletic group in the

Xinmoviridae family polymerase tree (

Figure 4A), with the closest relatives being viruses of diptera (Hubei diptera virus 11 [

11], Shuangao fly virus 2 [

12], and Gudgenby Calliphora mononega-like virus [

40]) and wasps (Hymenopteran anphe-related viruses OKIAV72 and OKIAV71 [

41]).

During revisions of the

Xinmoviridae taxonomy, criteria were introduced for a new genera and species. According to the accepted proposal, a new virus species must have a near-complete coding genome and an RdRp amino acid identity of 66% or lower, while a novel

Xinmoviridae genus should have RdRp amino acid identity lower than 60% [

39].

MCXV does not qualify as a novel virus species due to a large gap in the polymerase sequence. MHXV has a 35.9% identity in the polymerase to the closest relative and have a complete coding genome determined. Thus, MHXV may qualify as a novel Xinmoviridae genus according to those guidelines.

3.5. Toti-like viruses

Classical members of the

Totiviridae contain single-segment double-stranded RNA genomes of 4.5–7 kbp in length, with two often overlapping ORFs. The first ORF encodes major capsid protein (CP), and the second one encodes RdRp. Classical totiviruses infect eukaryotic microorganisms, such as

Leishmania spp. and

Trichomonas spp., or fungi [

42]. However, the results of recent metagenomic studies show a large diversity of toti-like viruses in the insects [

11].

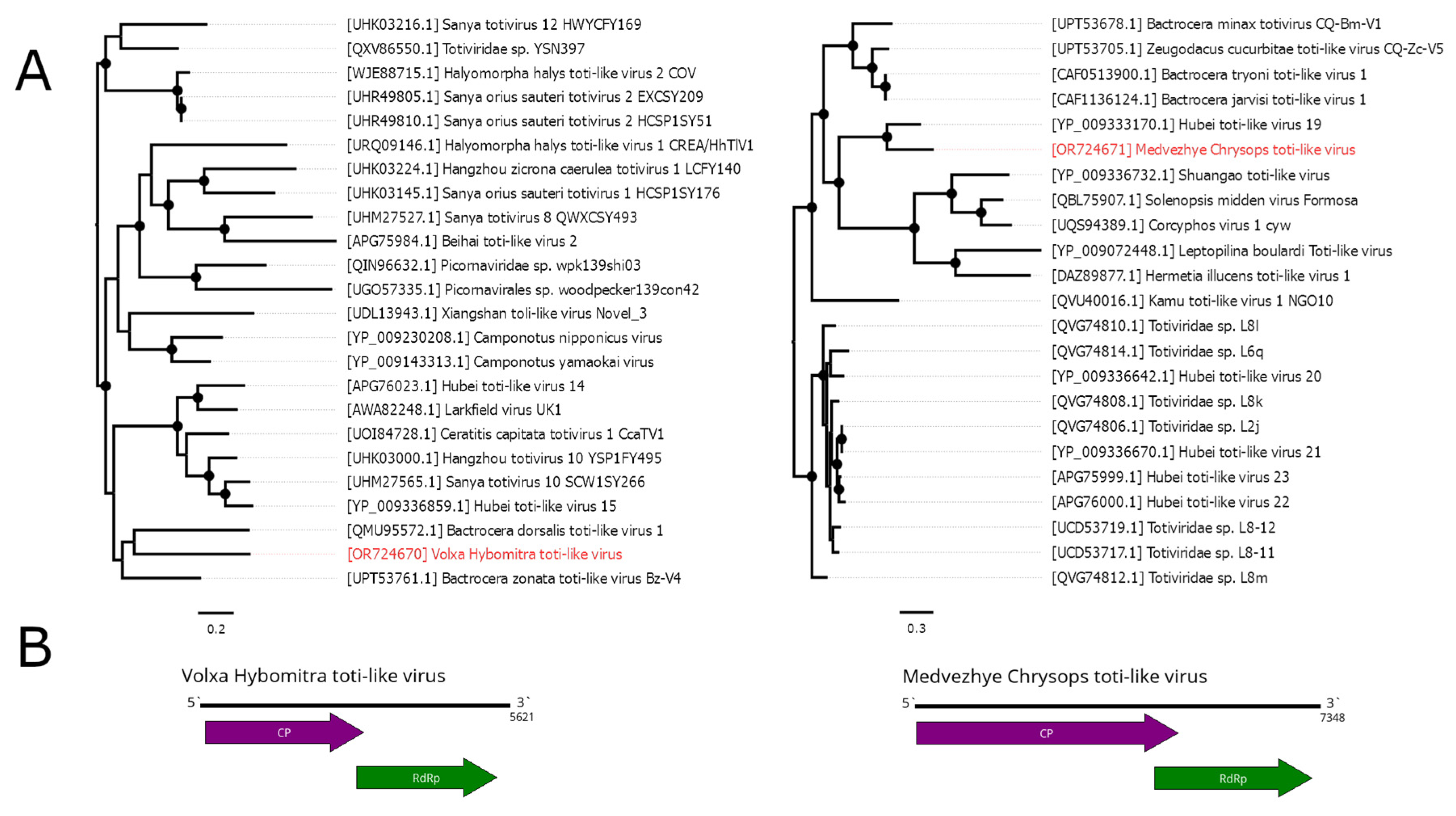

In the current study, we were able to find several contigs containing

Totiviridae – like ORFs (

Figure 5B). In pool 2 (

Hybomitra nigricornis), we found a single 5621 nt contig with two distinct ORFs, that had homology to the

Totiviridae CP and RdRp. According to RdRp BLAST, it had a 41.1% identity to the closest relative (Bactrocera zonata toti-like virus). Such a low identity across polymerase shows that this contig represents a genome of the novel virus, and it was named Volxa Hybomitra toti-like virus (VHTV). VHTV had 0.01% abundance in the pool.

In pool 8 (C. pictus/ C. caecutiens), we were able to detect a 7348 nt contig containing two ORFs with homology to the Totiviridae CP and RdRp. According to the RdRp BLAST, there was a 60% similarity to the closest relative (Hubei toti-like virus 19), and thus we considered it a novel virus and named it Medvezhye Chrysops toti-like virus (MCTV). The abundance of MCTV in the pool was 0.03%.

Additionally, in pool 9 (T. autumnalis/ T. bromius), we detected four contigs with homology to the Totiviridae proteins; however, we were not able to assemble a complete genome from them. Contigs had a 67–79 % identity to the CP and RdRp of the Hubei toti-like virus 19, and 54.2–67.9% identity to the MCTV. Thus, we can speculate that all of them belong to a genome of a single virus, which is more closely related to the Hubei toti-like virus 19 than to MCTV.

Phylogenetically, MCTV and VHTV belong to two unrelated groups of toti-like viruses (

Figure 5A). VHTV seems to be close (although with < 70% bootstrap support) to the viruses of the genus

Bactrocera fruit flies (Bactrocera dorsalis toti-like virus 1 [

43] and Bactrocera zonata toti-like virus Bz-V4 [

34]). MCTV formed a monophyletic group with the Hubei toti-like virus 19 [

11], isolated from unspecified species of tabanids. Other relatives include viruses found in wasps, ants and, soldier flies, while viruses of fruit flies form a separate monophyletic group.

3.6. Narna-like viruses

Classical members of the

Narnaviridae family are capsidless viruses that possess a positive-strand RNA genome 2.3–2.9 kb in length. The genome encodes a single viral protein—RdRp. Classical

Narnaviridae members infect fungi. Recently, a vast number of narna-like viruses was found in insects [

44]. While of these follow the classical

Narnaviridae genome plan, there are data indicating that at least some of them encode second functional ORF on the minus strand of the genome [

45,

46].

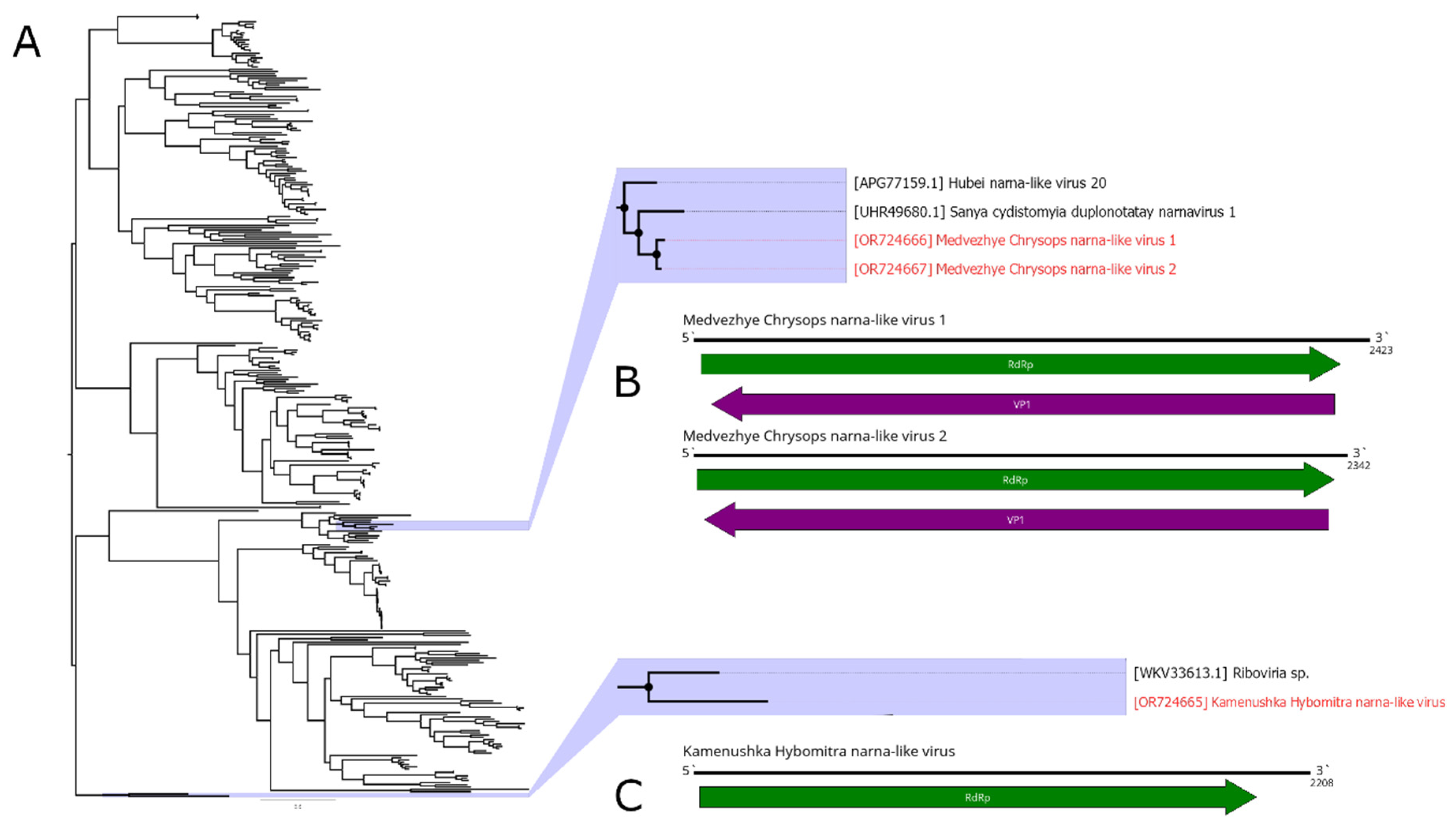

Here, we detected three narna-like contigs (

Figure 6B, C). The first one was detected in pool 2 (

H. nigricornis) and was 2208 nt in length. It contained a single ORF with homology to the narna-like RdRp and, according to BLAST, had 52.5% identity to the closest relative. Thus, we considered this contig as a genome of the novel narna-like virus and named it Kamenushka Hybomitra narna-like virus (KHNV). KHNV had an extremely low presence in the pool (less than 0.01%).

In pool 7 (C. relictus), we found two narna-like contigs. They were similar in length (2423 and 2342 nt) and had two ORFs, with one of them encoding RdRp. According to the RdRp BLAST, both had around 51% identity to the RdRp of the Sanya cydistomyia duplonotatay narnavirus 1. When compared with each other, polymerase-encoding ORFs of the two detected contigs had 87.2% identity. Thus, we considered those two contigs as two separate novel narna-like viruses and named them Medvezhye Chrysops narna-like virus 1 (MCNV1) and Medvezhye Chrysops narna-like virus 2 (MCNV2). The abundance of the MCNV1 and MCNV2 in the pool was 0.61% and 0.23%, respectively.

Phylogenetically KHNV formed a monophyletic group with an RdRp found in the metagenome of a

Parus caudatus (insectivorous bird) with no other close relatives (

Figure 6A). MCNV1 and MCNV2 formed a monophyletic group with Sanya cydistomyia duplonotatay narnavirus 1 (found in the

Sanya cydistomyia tabanid) and Hubei narna-like virus 20 (found in the unspecified Diptera) [

11].

3.7. Solemo-like viruses

The members of the

Solemoviridae family are non-enveloped plant viruses with a ~4–6 kb positive sense RNA genome. They use such mechanisms as ribosomal frameshifting, leaky scanning and subgenomic RNA production to express viral proteins [

47]. Recently, many new viruses with RdRps related to

Solemoviridae were discovered. These novel viruses are mostly found in insects and can drastically differed in their overall genome structure, for example, by having a different ORF count and/or by splitting the genome into two segments [

11].

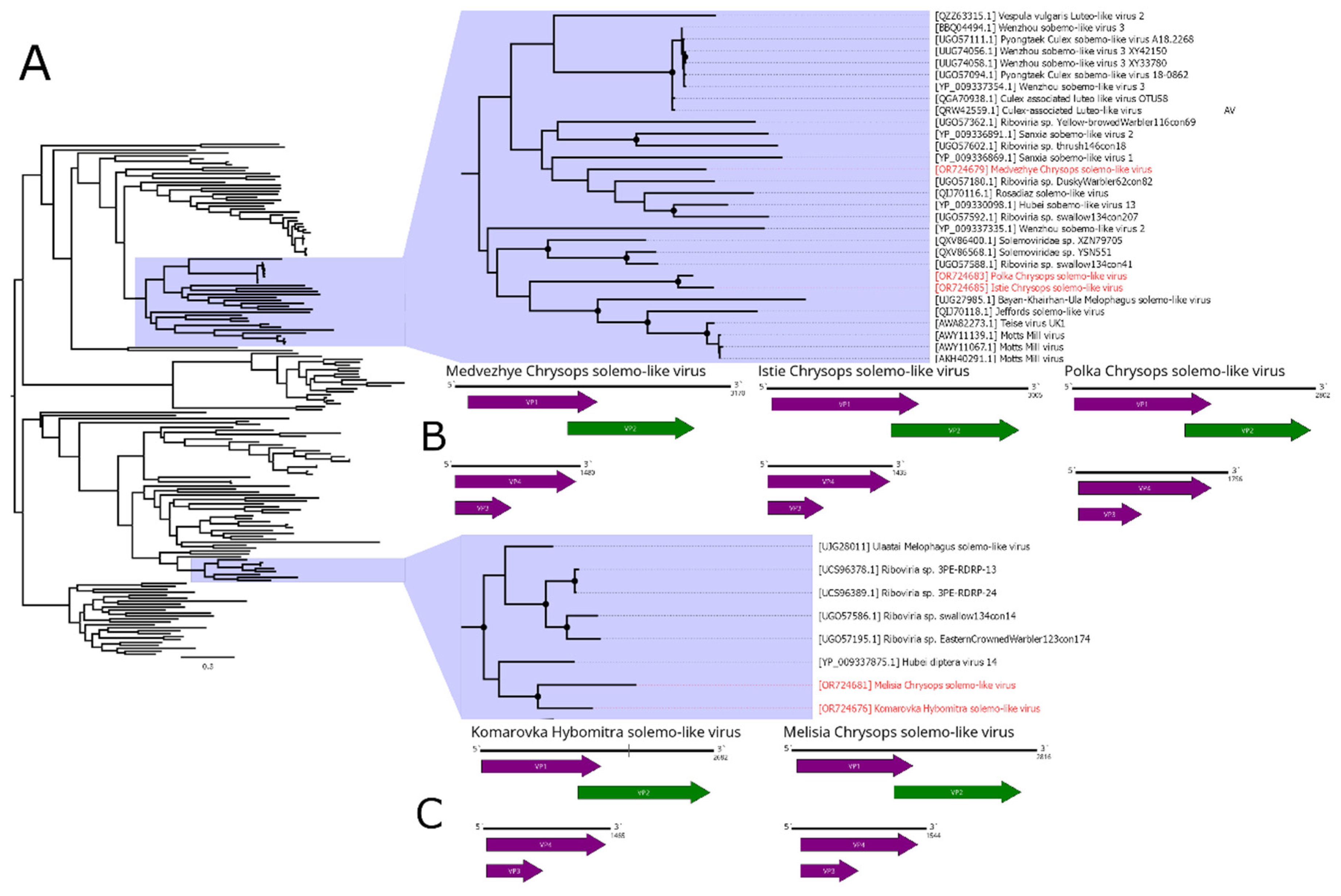

In this work, we discovered a number of

Solemoviridae-related contigs (

Figure 7B,C). In pool 2 (

H. nigricornis), we found four contigs. We identified one of them as a full second segment with 52.7% identity to the closest GenBank relative. We were able to assemble three remaining fragments into a partial sequence of the first segment (with only 5 nt remained unknown), using its closest GenBank relative (Ulaatai Melophagus solemo-like virus [

23]), as a reference. Overall, the first segment had a 63.6% identity in the RdRp. Therefore, we considered those two contigs to constitute a genome of the single solemo-like virus, and named it Komarovka Hybomitra solemo-like virus (KHSV). Overall, KHSV had less than 0.01% abundance in the studied pool.

In pool 8 (C. pictus/ C. caecutiens), we identified two solemo-related contigs. One of them contained a full sequence with an ORF layout typical for a segmented solemo-like virus and had a 46.6% identity to the closest GenBank relative in the RdRp. The second contig, according to BLAST, had a 42.2% identity to the closest relative and contained a partial sequence of the second segment, with approximately 10–15 aa missing on the 5` side of the VP3 ORF. Therefore, we considered these two contigs as a genome of the single solemo-like virus and named it Istie Chrysops solemo-like virus (ICSV). ICSV abundance in the studied pool was 0.01%.

In pool 7 (C. relictus), we found several contigs with homology to solemo-like proteins. Three contigs had a homology to the RdRp of the different viruses (39.5–55.7% identity), and all of them had a typical segmented solemo-like ORF layout. Other three contigs had an ORF layout typical for the second segment of the solemo-like viruses and homology CP (35.4 - 52.6% identity). Therefore, we considered these six contigs to be genomes of the three novel solemo-like viruses, and named them Medvezhye Chrysops solemo-like virus (MCSV), Melisia Chrysops solemo-like virus (MelCSV), and Polka Chrysops solemo-like virus (PCSV). MelCSV had the highest abundance (0.28%) in the studied pool, while the abundance of MCSV and PCSV was lower, standing at 0.13% and 0.05%, respectively. The first and second segments were grouped together only on the basis of their homology to similar viruses found in the GenBank.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the polymerase sequence showed that identified viruses are divided into three distinct groups (

Figure 7A). MelCSV and KHSV formed a monophyletic group related to the viruses of odonata (Hubei diptera virus 14 [

11]), birds (Riboviria sp. viruses), and

Melophagus ovinus L., 1758 (Ulaatai Melophagus solemo-like virus [

23]). PCSV and ICSV formed another monophyletic group, related (although with < 70% bootstrap support) to the other Diptera viruses, including viruses of

Drosophila (Teise virus, Motts Mill virus [

48,

49]),

Musca vetustissima (Jeffords solemo-like virus [

40]), and

M. ovinus (Bayan-Khairhan-Ula Melophagus solemo-like virus [

23]). MCSV formed a separate branch, with low bootstrap support to any proposed groupings.

3.8. Permutotetra-like virus

The

Permutotetraviridae family contains the single genus

Alphapermutotetravirus, with two member species that infect Lepidopteran insects. They are characterized by the monopartite single-stranded (+) RNA genome, containing two overlapping ORFs. The first ORF encodes unique internally permuted polymerase, with a C–A–B arrangement of the canonical motifs found in the palm subdomain of all polymerases. The second ORF encodes a capsid protein and is expressed from a subgenomic RNA [

50]. The recent metagenomic advancements in virology resulted in the discovery of many new permuto-like viruses [

11].

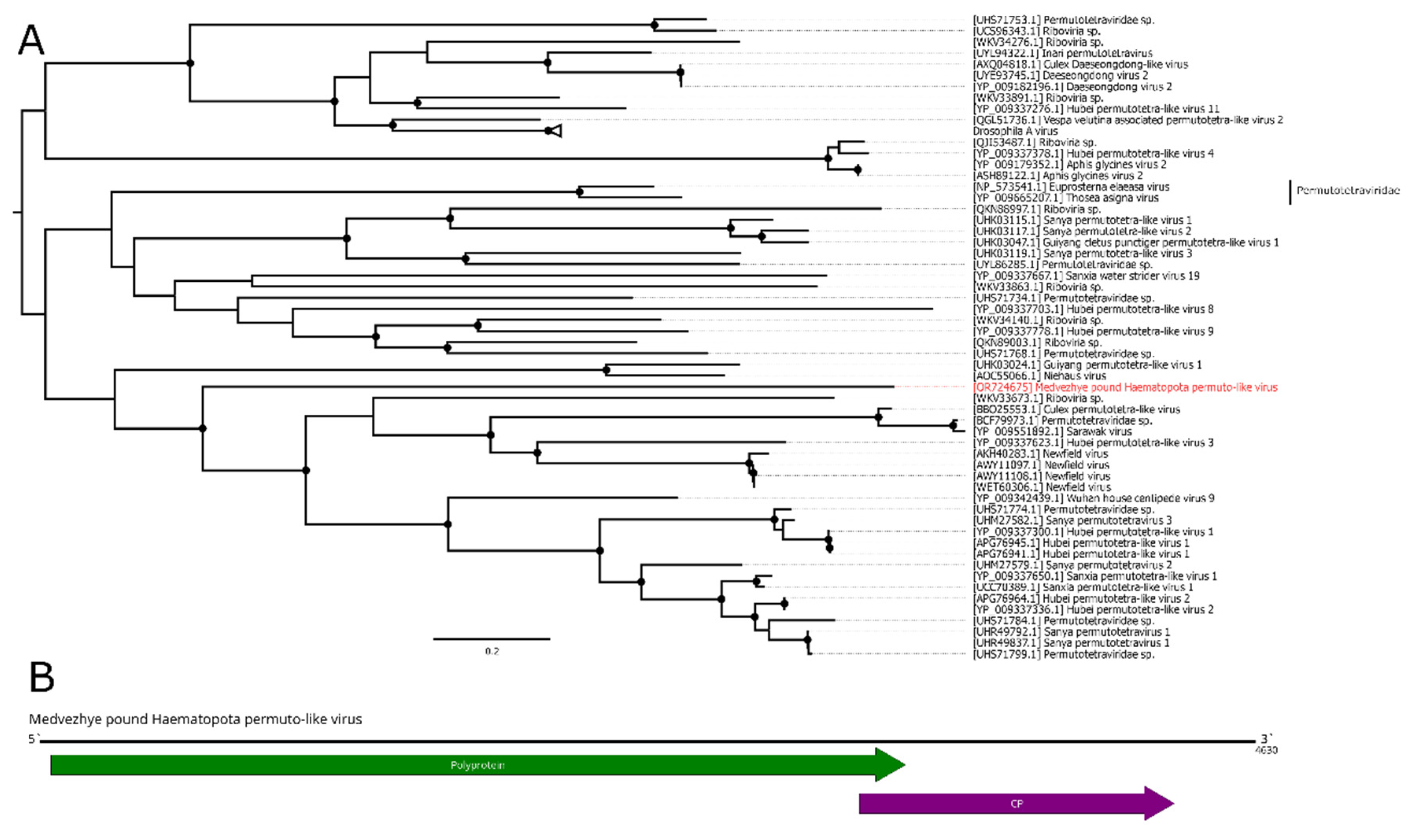

In this work, we discovered a 4.6 kb contig with homology to the permuto-like polymerase in pool 6 (

Ha. pluvialis). Further analysis showed that it had two ORFs in the typical permuto-like order: the first one encoded a polyprotein with the RdRp domain, then the second one encoded CP (

Figure 8B). According to the BLAST analysis of the polyprotein ORF, there was only a 35.8% identity to the closest relative with 61% query cover. Such a low identity across polyprotein shows that this contig represent a genome of a novel virus, and it was named Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus (MHPV). MHPV had 0.03% abundance in the pool. Phylogenetically, MHPV is a sister group to various permuto-like viruses of the insects (

Figure 8A).

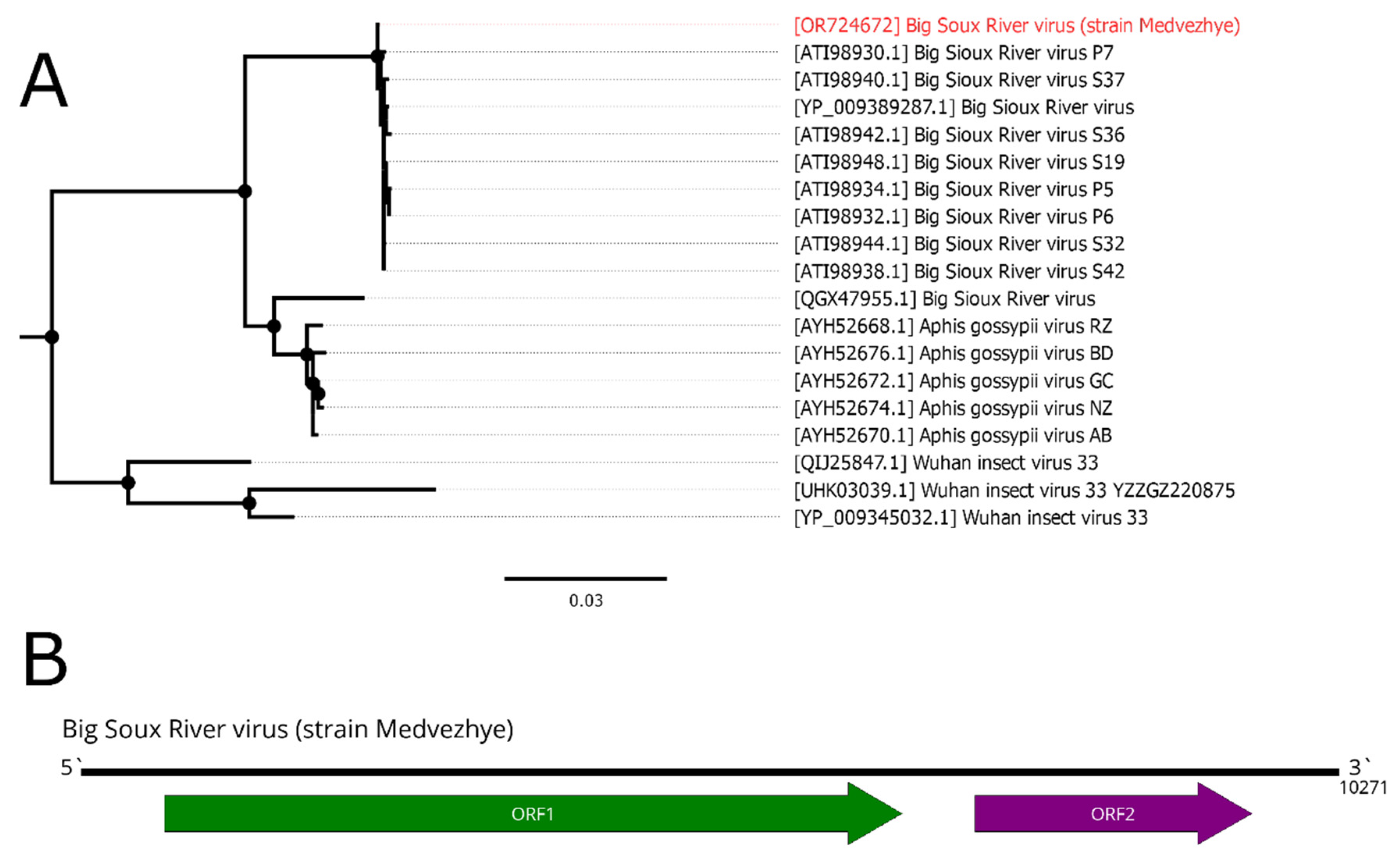

3.9. Big Sioux River virus

Big Sioux River virus (BSRV) is a dicistro-like virus. It has a positive-strand RNA genome of 10 kb with two ORFs, typical for the

Dicistroviridae members. The first one encodes nonstructural proteins, including RdRp, and the second one encodes capsid proteins. BSRV was first isolated from honeybees (

Apis mellifera) [

51], and later detected in the soybean aphid (

Aphis glycines) and

Culex tritaeniorhynchus mosquitoes in China [

16], and

Aphis fabae in Kenya [

52].

We detected a 10271 nt long contig in pool 7 (

C. relictus). It had two ORFs, typical for the

Dicistroviridae (

Figure 9B), as well as a very high homology to the BSRV (99% identity with 99% query cover) in the RdRp-encoding ORF. Thus, we considered this contig as a genome of the novel BSRV strain and called it strain Medvezhye. Phylogenetically, our strain formed a clear monophyletic group with all other BSRV strains, except QGX47955, which clustered together with several isolates of the Aphis gossypii virus (

Figure 9A).

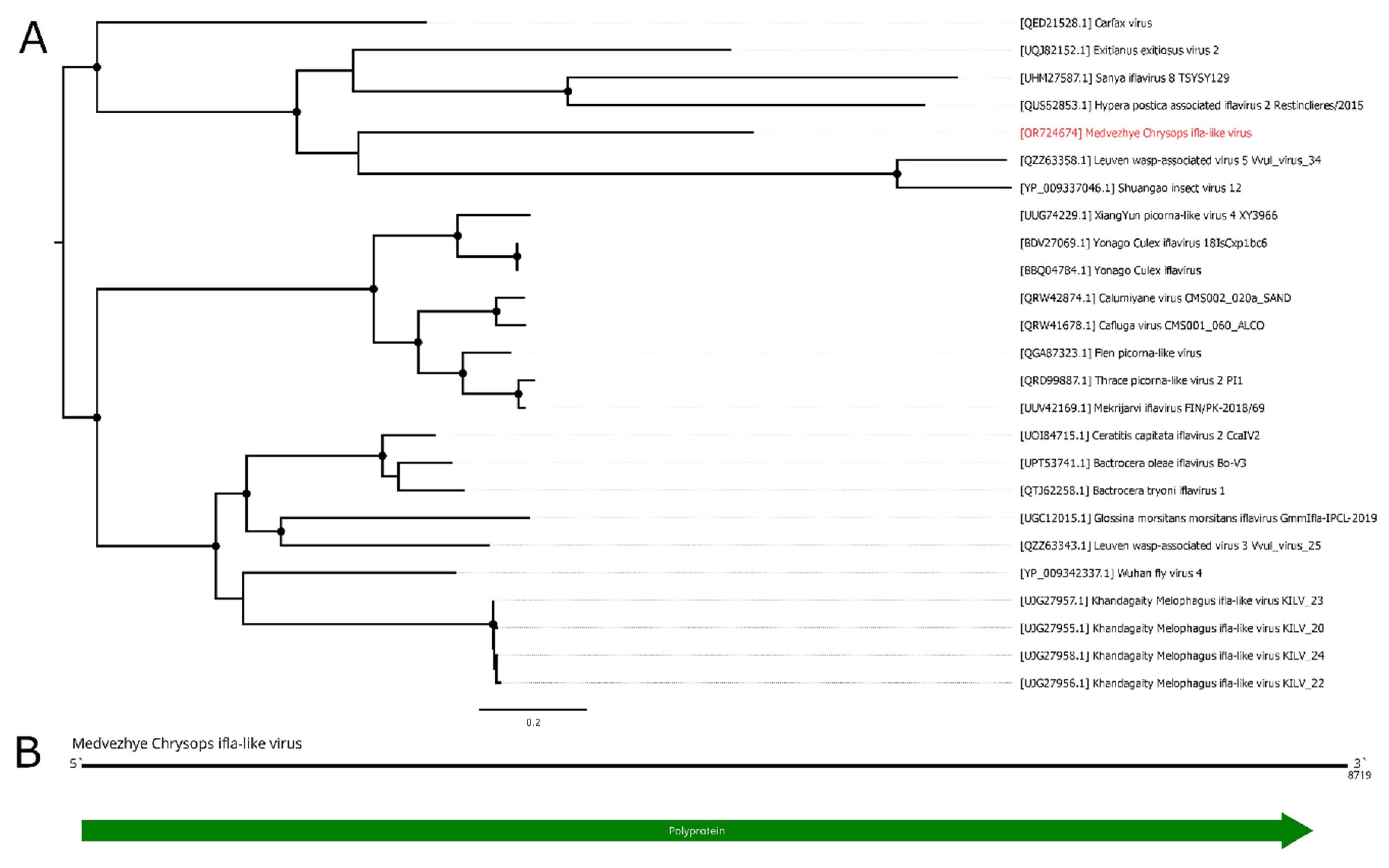

3.10. Ifla-like viruses

Classical members of the

Iflaviridae family are non-enveloped, single-stranded, non-segmented, and positive-sense RNA viruses. The genome is 9–11 kb in length and encodes a single ORF. This ORF encodes a polyprotein that is processed into several virus proteins, including RdRp. All members of the

Iflaviridae family are isolated from arthropods [

53]. Recently, the diversity of iflaviruses expanded significantly due to the study of insect viromes using HTS approaches [

11].

In the current work, we managed to find several ifla-related contigs in the studied material. The first one, found in pool 8 (

C. pictus/ C. caecutiens), was 8719 nt long and had a single ORF (

Figure 10B). According to BLAST of these ORF, it had 34.5% identity to the closest relative (Exitianus exitiosus virus 2); however, the contig was truncated compared to a full ifla-like genome, lacking 5`UTR and a small 5`-terminal part of the polyprotein encoding sequence. Thus, we considered this contig to be a partial genome of the novel ifla-like virus, and named it Medvezhye Chrysops ifla-like virus (MCIV). MCIV had a 0.02% presence in the pool.

In pool 2 (

H. nigricornis), we found seven contigs related to various ifla-like viruses; however we were not able to assemble them in a single genome. Contigs varied in length (408 – 1234 nt) and had 31.8–63% identity to the closest relative according to online BLAST. At the same time, those contigs showed higher identity (

Table S7) to the MCIV polyprotein (35 – 72%). Additionally, we found a single 381 nt contig in the pool 3(

Hybomitra stigmoptera), with homology to ifla-like protein. Interestingly, ORF this contig encoded was closer to the MCIV polyprotein (79.9% identity), than to the NODE_21_length_616 contig from the

H. nigricornis pool (52% identity), and to the closest GenBank entry (39.6%). Thus, we assume that at least one ifla-like virus might exist in the discussed

Hybomitra pools. Working names of genome fragments are given in

Table S4.

Phylogenetically MCIV forms a monophyletic group (

Figure 10A) with ifla-like viruses of various insects (Shuangao insect virus 12 [

11]), including leafhoppers (Exitianus exitiosus virus 2 [

54]), mantis fly (Sanya iflavirus 8), alfalfa weevil beetle (Hypera postica associated iflavirus 2 [

55]), and common wasp (Leuven wasp-associated virus 5 [

56]). Although we were not able to construct a reliable phylogenetic tree using genome fragments found in the

H. nigricornis and

H. stigmoptera, we can speculate that they are likely to group in a monophyletic group with the MCIV due to its higher polyprotein identity compared to any GenBank entry.

3.11. Virus-like fragments

In addition to the abovementioned toti-like, ifla-like, and xinmo-like genome fragments, we also managed to detect contigs related to the following virus groups: Orthophasmavirus (

Bunyavirales,

Phasmaviridae), Nora virus (

Picornavirales,

Noraviridae),

Solinviviridae (

Picornavirales),

Chuviridae (

Jingchuvirales) and

Rhabdoviridae (

Mononegavirales) genome fragments. Working names of genome fragments are given in

Table S4.

Solinviviridae-like contigs were detected in both pool 7 (

С. relictus) and pool 8 (

C. pictus/ C. caecutiens). In both cases, amino acid sequences of the fragments showed similarity (38–82% identity for different fragments) to the polyprotein of the Hangzhou solinvi-like virus 2 (

Table S4), which was found in the

Orthetrum testaceum dragonfly metagenome. However, contigs from both pools had very high levels of similarity (96.9–99.5% identity), even on the nucleotide level, and abundance of reads in pool 8 was very low (

Table S8). We believe that the possibility of read contamination during sequencing run in case of pool 8 is likely, and do not consider reads in pool 8 as a detected virus.

There was a single 616 nt Nora-virus-like contig found in the pool 6 (Ha. pluvialis). Its closest relative (42.9% aa identity) was Caledonia beadlet anemone nora virus-like virus 1, found in a common sea anemone Actinia equine.

Orthophasma-like contigs were found in three pools: pool 1 (

H. brevis), pool 8 (

C. pictus/ C. caecutiens), and pool 9 (

T. autumnalis/ T. bromius). In the

C. pictus/ C. caecutiens pool, we were able to assemble sequences that represent a full coding sequence of the glycoprotein, and about 80% of the RdRp and nucleocapsid protein. In the two other pools, contigs were significantly smaller. Overall, contigs encode ORFs related to all three

Orthophasmavirus segments, with amino acid identity varying from 31.5 to 69.3% and the closest relative in most cases being Tibet bird virus 1, detected in the bird feces metagenome. Detected contigs showed 42–77.3% identity in a pool-to-pool comparison, implying that contigs from different pools belong to different viruses (

Table S9 – S10).

In pool 7 (С. relictus), three contigs encoding rhabdo-like RdRp were detected. Further investigation showed that one of them was related to the Wuhan fly virus 3 and Shayang fly virus 3 (Rhabdoviridae, Alphadrosrhavirus), while the other two contigs were related to the Hubei lepidoptera virus 2 (Rhabdoviridae, Alphapaprhavirus). This shows that there may be at least two different rhabdo-like viruses in the С. relictus pool.

In pool 9 (T. autumnalis/ T. bromius) we detected five contigs with homology to Chuviridae RdRp and glycoprotein. Most of the fragments were related to the megalopteran chu-related virus 119, with 32.4–52.8% identity.

3.12. Virus isolation

In addition to the high-throughput sequencing, we performed research on the ability of the discovered viruses to reproduce in three cell cultures: C6/36—originating from

Aedes albopictus; HAE/CTVM8—originating from

Hyalomma anatolicum ticks; and pig embryo kidney (PEK) cell line. Cell lines were infected with pools of the tabanid homogenate, as described in

Table 1. For C6/36 and PEK cell lines, three blind passages were performed. In the case of the HAE/CTVM8 cell line, three weeks of persistent infection with weekly changes of the culture medium were performed. After this, we tested the collected supernate using virus-specific oligonucleotides. PCR-positive results were confirmed using Sanger sequencing of the obtained PCR product. Thirteen viruses were detected in the HAE/CTVM8 cell culture after three weeks of persistence, eleven viruses were detected in the C6/36 cell culture, and nine viruses were detected in the PEK cell culture. Overall, seventeen viruses were detected using PCR (

Table 2).

Since the amount of the viruses detected was particularly big, we decided to better estimate their replication dynamic by quantifying the virus amount on each passaging step using qPCR with TaqMan probes. qPCR analysis was performed for all positive in PCR viruses, except MCIV, MedCNV, and MCSV. The results are presented in

Figures S1-S14.

No cases were observed where viral load consistently increased. Overall, in the majority of cases, viral load decreased with each passage (PEK and C6/36 cell lines) or week of chronic infection (HAE/CTVM8 cell line). In some cases, we observed the virus load increase between the first and second weeks of chronic infection in HAE/CTVM8 cell line (Barsukovka Hybomitra ifla-like virus, MCNV2, PCSV, MelCSV, BSRV, and VHTV). We also observed virus load increase between the first and second passage in C6/36 cell line in VHTV. Additionally, virus load increased between the second and third weeks of chronic infection for Medvezhye Tabanus toti-like virus in HAE/CTVM8 and between the second and third PEK cells. The same could be said for ICSV in the HAE/CTVM8 cell line.

The third passage in the PEK cell line was additionally tested on the presence of viruses using HTS. Overall, genome fragments of eight viruses were detected (

Table 3). Five of them were also detected via PCR (

Table 2), while three of them were detected only via HTS. It should be noticed, however, that only a small number of reads were detected and we were not able to assemble full coding genome for any of detected virus after 3 passages in PEK cell line.

Additionally, we performed six passages of the pool 7 (C. relictus) in the PEK and C6/36 cell lines. However, no viruses were detected in both cultures using virus-specific PCR oligonucleotides.

4. Discussion

Viromes of some blood-sucking ectoparasites, such as mosquitoes and ticks, have been relatively well-studied [

13,

14,

15,

16,

18,

19,

20], due to their importance as a vectors for various human and animals pathogens. Viromes of tabanids, the largest group of haematophagous insects [

2,

3], remain relatively unstudied. Here, we present data on the virome of several species of

Hybomitra, Tabanus, Chrysops, and

Haematopota genera which were collected in Russia. Previously, the viromes of five unidentified specimens of tabanids were studied using HTS, and five novel viruses were discovered [

11].

Here, we explored RNA viromes of several species of tabanids, collected in different parts of Russia, namely, from Primorye Territory and Ryazan Region. In our study, different pools contained from 0 to 10 viruses, with about 3 viruses per pool on average. Virus diversity was higher in the samples collected in the Ryazan Region (

Figure 1). Currently, with different species of tabanids analyzed and collected in places that are far from each other at a different time, it is hard to determine whether this difference is a result of territory, tabanid species, or some other factors.

ICTV species determination guidelines differ for different genera [

39,

57], and in many cases they are not actively used for novel viruses discovered via HTS [

47,

53,

58]. At the same time, ICTV requires uncultivated virus genome sequences to have at least a complete coding sequence in order to be accepted for taxonomic classification [

59]. Here, for simplicity, we used one universal criterionfor a novel virus, namely, that it should have less than 90% similarity amino acid identity in the polymerase-encoding ORF to the closest relative. We also proposed working names for all detected viruses. Obviously, the final decision on their nomenclature and classification can only be made by the ICTV.

Overall, we were able to identify 30 novel viruses. Fourteen of them had complete coding sequence assembled, and thus can be accepted for further taxonomic classification [

59]. Overall, the identified viruses included positive-sense and negative-sense RNA viruses from 12 distinct groups. Only one virus from among these had previously been described, while the others differed significantly from the viruses found in the GenBank database. Moreover, MHXV even qualified a genus demarcation criteria in the

Xinmoviridae family according to the ICTV guidelines [

39]. Thus, our work contributes to the description of virus biodiversity.

In most cases, newly discovered viruses clustered together with each other, other viruses of the tabanids or members of the Diptera. In the case of toti-like, solemo-like and narna-like viruses, several clusters of tabanid viruses were observed across phylogenetic tree. Previously, a similar situation had been observed for solemo-like viruses of the

M. ovinus [

23]. Interestingly, in several cases (xinmo-like viruses, ifla-like viruses and one group of the toti-like viruses), viruses found in wasps were closely related to tabanid viruses, with mosquito viruses, for example, being more distant. While this situation may be the consequence of our lack of knowledge regarding insect viruses, it may also be a sign of virus interspecies transmission due to ecological interactions. For example, sand wasps can prey on the various species of tabanids [

5,

60]. Overall, additional information about insect viromes will improve our understanding of virus speciation.

There are several viruses that are known to be mechanically transmitted by tabanids [

1,

9]. Here, we did not find any of those viruses, or any viruses that may be considered their close relatives. This was an expected result, since we collected tabanids far from areas with large aggregations of livestock.

BSRV was the only known virus that was found in the pools. This was the first recorded detection of BSRV in tabanids. It have previously been detected in honeybees (

A. mellifera)[

51], and later in the soybean aphid (

A. glycines) and

C. tritaeniorhynchus mosquitoes in China [

16], as well as in

Ap. fabae in Kenya [

52]. It should be noted, however, that honeybees BSRV had only 87% similarity both strains isolated from

C. tritaeniorhynchus, as well as with a strain isolated from

Ap. fabae [

52].

Here, we attempted to isolate novel viruses using three different cell cultures. Sixteen viruses were detected on the third passage; however, the virus load in qPCR was decreasing in the majority of cases. No cases were observed where viral load consistently increased. These data indicate that, in the majority of cases, even if viruses are able to replicate in cell cultures, their reproduction level is very low and virus is being slowly eliminated from cell cultures.

In several cases, viral load increased between the first and second or the second and third passage. Those cases may be a sign of the ongoing virus adaptation to the cell cultures, and further work is needed in order to determine if they are able to reproduce stably or will be ultimately eliminated from cell culture. It should be noted that, in the majority of cases, an increase in viral load was observed during persistence in the HAE/CTVM8 cell line. The question of whether this is a result of the properties of this specific cell culture, or a result of a virus persistence cultivation scheme (passages were used with C6/36 and PEK cell lines), should be the subject of future research.

5. Conclusions

We explored RNA viromes of several species of tabanids collected in Russia. Full coding sequences of fourteen novel viruses were assembled. In four more cases, we were able to assemble partial coding sequences of the viruses and detected genome fragments that may indicate the presence of at least 12 more viruses in the studied samples. Thus, our work contributes to the description of virus biodiversity.

All detected viruses were studied on their ability to replicate in the C6/36, HAE/CTVM8, and PEK cell lines. While seventeen viruses were detected using PCR on the third passage (for PEK and C6/36 cell lines) or third week of chronic infection (HAE/CTVM8), viral load steadily decreased in majority of cases. No cases were observed where viral load consistently increased. It seems that three passages are insufficient to conclude the isolation of viruses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Oligonucleotides used for PCR-detection of the novel viruses; Table S2: Table S2. Oligonucleotides used for internal control Poliovirus RT-qPCR; Table S3: Characteristics of viruses with complete and partial coding sequences; Table S4: Characteristics of genome fragments detected in the study; Table S5: Similarity estimation within tabanid negev-like viruses using discontiguous megablast on the full genome; Table S6: Similarity estimation within tabanid xinmo-like sequences using L protein amino acid sequence; Table S7: Similarity estimation within tabanid ifla-like sequences using polyprotein amino acid sequence; Table S8: Similarity estimation within tabanid solinvi-like sequences using polyprotein amino acid sequence; Table S9: Similarity estimation of pool 1 orthophasma-like contig with orthophasma-like sequences from pools 8 and 9 using amino acid sequences; Table S10: Similarity estimation of pool 9 orthophasma-like contig with orthophasma-like sequences from pools 8 and 1 using amino acid sequences; Figure S1: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Xanka Hybomitra negev-like virus; Figure S2. Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Volxa Hybomitra toti-like virus. Figure S3: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Kamenushka Hybomitra narna-like virus. Figure S4: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus; Figure S5: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Polka Haematopota nora-like virus. Figure S6: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Big Soux River virus (strain Medvezhye). Figure S7: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Melisia Chrysops solemo-like virus; Figure S8: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Polka Chrysops solemo-like virus; Figure S9. Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Medvezhye Chrysops narna-like virus; Figure S10: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Medvezhye Chrysops rhabdo-like virus; Figure S11: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Istie Chrysops solemo-like virus; Figure S12: Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Medvezhye Tabanus toti-like virus; Figure S13. Dynamic of the real-time quantification cycle (Cq) during passages of the Komarovka hybomitra solemo-like virus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.L. and G.G.K.; formal analysis, A.G.L.; investigation, A.G.L., O.A.B., I.S.K., A.S.K., M.N.G., A.A.R., L.V.G., G.G.K; resources, G.G.K; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.L., O.A.B., I.S.K., M.N.G., G.G.K; writing—review and editing, A.G.L., O.A.B., I.S.K., M.N.G., G.G.K; visualization, A.G.L; supervision, G.G.K; project administration, G.G.K; funding acquisition, G.G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, Grant no. 21-14-00245.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Raw high throughput sequencing data obtained during this study are available in the SRA database (BioProject accession number PRJNA1026651). Obtained virus sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (accession numbers OR724662 - OR724699).

Acknowledgments

The tick cell line HAE/CTVM8 was kindly provided by Lesley Bell-Sakyi from the Tick Cell Biobank (University of Liverpool, United Kingdom).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baldacchino, F.; Desquesnes, M.; Mihok, S.; Foil, L. D.; Duvallet, G.; Jittapalapong, S. Tabanids: Neglected subjects of research, but important vectors of disease agents! Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pape, T.; Blagoderov, V.; Mostovski, M. B. Order Diptera Linnaeus, 1758. Zootaxa 2011, 3148, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, S. I..; Bayless, K. M.; Yeates, D. K.; Wiegmann, B. M. Molecular phylogeny of the horse flies: a framework for renewing tabanid taxonomy. Syst. Entomol. 2016, 41, 56–72. [CrossRef]

- Akbaev, R. M.; Cherednichenko, D. A.; Borets, L. S. Species composition of horseflies (Diptera: Tabanidae) in the moscow region. Izv. Orenbg. State Agrar. Univ. 2021, 88, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Desquesnes, M. Livestock Trypanosomoses and their Vectors in Latin America; World organisation for animal health: Paris, France, 2004; ISBN 929044634X. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Hope, L. A.; Bockarie, M. J.; Molyneux, D. H. Loa loa Ecology in Central Africa: Role of the Congo River System. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, June 26. [CrossRef]

- Couvillion, C. E.; Nettles, V. F.; Sheppard, D. C.; Joyner, R. L.; Bannaga, O. M. Temporal occurrence of third-stage larvae of elaeophora schneideri in tabanus lineola hinellus on south island, south carolina. J Wildl Dis 1986, 22, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D.M. Spratt Distribution of third-stage Dirofilaria roemeri (Nematoda: Filarioidea) in the tissues of tabanidae (Diptera). Int. J. Parasitol. 1974, 4, 477–480.

- Hasselschwert, D. L.; French, D.; Hribar, L.; Luther, D.; Leprince, D.; Van De Maaten, M.; Whetstone, C.; Foil, L. Relative Susceptibility of Beef and Dairy Calves to Infection by Bovine Leukemia Virus Via Tabanid (Diptera:Tabanidae) Feeding. J. Med. Entomol. 1993, 30, 472–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, S.; Ka, S.; Zirkel, F.; Donath, A.; Petersen, M.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Drosten, C.; Misof, B.; Junglen, S. Viromics of extant insect orders unveil the evolution of the flavi-like superfamily. Virus 2021, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.; Tian, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Qin, X.; Li, J.; Cao, J.; Eden, J.; Buchmann, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E. C.; Zhang, Y. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Shi, M.; Tian, J.; Lin, X.; Kang, Y.; Chen, L.; Qin, X.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E. C.; Zhang, Y. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. Elife 2015, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseille, R.; Nebbak, A.; Monteil-bouchard, S.; Berenger, J.; Almeras, L.; Parola, P.; Desnues, C. Virome Diversity among Mosquito Populations in a Sub-Urban Region of Marseille, France. Viruses 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atoni, E.; Wang, Y.; Karungu, S.; Waruhiu, C.; Zohaib, A.; Obanda, V.; Agwanda, B.; Mutua, M.; Xia, H.; Yuan, Z. Metagenomic Virome Analysis of Culex Mosquitoes from Kenya and China. Viruses 2018, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, M.; Wahaab, A.; Shan, T.; Wang, X.; Khan, S.; Di, D.; Xiqian, L.; Zhang, J.-J.; Anwar, M. N.; Nawaz, M.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Shao, D.; Qiu, Y.; Wei, J.; Ma, Z. A Metagenomic Analysis of Mosquito Virome Collected From Different Animal Farms at Yunnan – Myanmar Border of China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z. A Metagenomic Survey of Viral Abundance and Diversity in Mosquitoes from Hubei Province. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P. T. T.; Culverwell, C. L.; Suvanto, M. T.; Korhonen, E. M.; Uusitalo, R.; Vapalahti, O.; Smura, T.; Huhtamo, E. Characterisation of the RNA Virome of Nine Ochlerotatus Species in Finland. Viruses 2022, 14, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, E.; Rose, K.; Eden, J.; Lo, N.; Abeyasuriya, T.; Shi, M.; Doggett, S. L.; Holmes, E. C. Extensive Diversity of RNA Viruses in Australian Ticks. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, J. H.; Shi, M.; Bohlin, J.; Eldhol, V.; Brynildsrud, O. B.; Paulsen, K. M.; Andreassen, Å.; Holmes, E. C. Characterizing the virome of Ixodes ricinus ticks from northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sadiq, S.; Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, X.; Shen, J.; Chen, H.; Hao, Z.; Wille, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, F.; Wang, H.-W.; Yang, W.-D.; Xu, Q.-Y.; Wang, W.; Gao, W.-H.; Holmes, E. C.; Zhang, Y.-Z. RNA viromes from terrestrial sites across China expand environmental viral diversity. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ler, P. A. Key to the insects of Russian Far East. Vol. VI. Diptera and Siphonaptera. Pt 2.; Ler, P. A., Ed.; Dal’nauka: Vladivostok,Russia, 2001; ISBN ISBN 5–8044–0087–8.

- Bey-Bienko, G. Y. Key to insects of the European part of the USSR Volume 5. Diptera, fleas.; Bey-Bienko, G. Y., Ed.; Nauka: Leningrad, USSR, 1969.

- Litov, A. G.; Belova, O. A.; Kholodilov, I. S.; Gadzhikurbanov, M. N.; Gmyl, L. V; Oorzhak, N. D.; Saryglar, A. A.; Ishmukhametov, A. A.; Karganova, G. G. Possible Arbovirus Found in Virome of Melophagus ovinus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A. A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A. S.; Lesin, V. M.; Nikolenko, S. I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A. D.; Pyshkin, A. V.; Sirotkin, A. V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M. A.; Pevzner, P. A. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; Mcginnis, S.; Madden, T. L. NCBI BLAST : a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2013, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazutaka Katoh; Daron M. Standley MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780.

- Capella-Gutierrez, S.; Silla-Martinez, J. M.; Gabaldon, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. PhyML : “A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood.” Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 696–704.

- Bell-Sakyi, L. Continuous cell lines from the tick Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum. J. Parasitol. 1991, 77, 1006–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilakis, N.; Forrester, N. L.; Palacios, G.; Nasar, F.; Savji, N.; Rossi, S. L.; Hilda Guzman, A.; Wood, T. G.; Popov, V.; Gorchakov, R.; González, A. V.; Haddow, A. D.; Watts, D. M.; Ravassos, A. P. A.; Weaver, S. C.; Lipkin, W. I.; Tesh, B. Negevirus : a Proposed New Taxon of Insect-Specific Viruses with. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2475–2488. [CrossRef]

- Faizah, A. N.; Kobayashi, D.; Isawa, H.; Amoa-bosompem, M.; Murota, K.; Higa, Y.; Futami, K.; Shimada, S.; Kim, K. S.; Itokawa, K.; Watanabe, M.; Tsuda, Y.; Minakawa, N.; Miura, K.; Hirayama, K.; Sawabe, K. Deciphering the Virome of Culex vishnui Subgroup Mosquitoes, the Major Vectors of Japanese Encephalitis, in Japan. Viruses 2020, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gu, Q.; Niu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. The Diversity of Viral Community in Invasive Fruit Flies (Bactrocera and Zeugodacus) Revealed by Meta-transcriptomics. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 83, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, P.; Becher, P.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E. A.; Meyers, G.; Monath, T.; Muerhoff, S.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-hesse, R.; Smith, D. B.; Stapleton, J. T.; Consortium, I. R. ICTV ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debat, H.; Bejerman, N. Two novel flavi-like viruses shed light on the plant-infecting koshoviruses. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Lin, X.; Vasilakis, N.; Tian, J.; Li, C.; Chen, L.; Eastwood, G.; Diao, X.; Chen, M.-H.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.-C.; Widen, S. G.; Wood, T. G.; Tesh, R. B.; Xu, J.; Holmes, E. C.; Zhanga, Y.-Z. Divergent Viruses Discovered in Arthropods and Vertebrates Revise the Evolutionary History of the Flaviviridae and Related Viruses. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, J.; Dudas, G.; Haas-stapleton, E.; Kistler, A. L.; Li, L. M.; Logan, P.; Ratnasiri, K.; Retallack, H. Single mosquito metatranscriptomics identifies vectors, emerging pathogens and reservoirs in one assay. Elife 2021, 10, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, S. R.; Paraskevopoulou, S. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Xinmoviridae 2023. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, in press. in press.

- Mahar, J. E.; Shi, M.; Hall, R. N.; Strive, T.; Holmesa, E. C. Comparative Analysis of RNA Virome Composition in Rabbits and Associated Ectoparasites. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafer, S.; Paraskevopoulou, S.; Zirkel, F.; Wieseke, N.; Donath, A.; Petersen, M.; Jones, T. C.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; Middendorf, M.; Junglen, S.; Misof, B.; Drosten, C. Re-assessing the diversity of negative strand RNA viruses in insects. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Virus Taxonomy Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; King, A. M. Q., Adams, M. J., Carstens, E. B., Lefkowitz, E. J., Eds.; Elsevier, 2012.

- Zhang, W.; Gu, Q.; Niu, J.; Wang, J. The RNA Virome and Its Dynamics in an Invasive Fruit Fly, Bactrocera dorsalis, Imply Interactions Between Host and Viruses. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 80, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, E. J.; Dempsey, D. M.; Hendrickson, R. C.; Orton, R. J.; Siddell, S. G.; Smith, D. B. Virus taxonomy: The database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D708–D717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retallack, H.; Popova, K. D.; Laurie, M. T.; Sunshine, S.; DeRisi, J. L. Persistence of Ambigrammatic Narnaviruses Requires Translation of the Reverse Open Reading Frame. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derisi, J. L.; Huber, G.; Kistler, A.; Retallack, H.; Wilkinson, M.; Yllanes, D. An exploration of ambigrammatic sequences in narnaviruses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sõmera, M.; Fargette, D.; Hébrard, E.; Sarmiento, C.; Consortium, I. R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Solemoviridae 2021. J. Gen. Virol. 2021, 102, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, C. L.; Waldron, F. M.; Robertson, S.; Crowson, D.; Ferrari, G.; Quintana, J. F.; Brouqui, J. M.; Bayne, E. H.; Longdon, B.; Buck, A. H.; Lazzaro, B. P.; Akorli, J.; Haddrill, P. R.; Obbard, D. J. The discovery, distribution, and evolution of viruses associated with Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medd, N. C.; Fellous, S.; Waldron, F. M.; Xue, A.; Nakai, M.; Cross, J. V; Obbard, D. J. The virome of Drosophila suzukii, an invasive pest of soft fruit. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrington, R. A.; Jiwaji, M.; Awando, J. A. Advances in Tetravirus Research : New Insight into the Infectious Virus Life Cycle and an Expanding Host Range. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2020, 34, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runckel, C.; Flenniken, M. L.; Engel, J. C.; Ruby, J. G.; Ganem, D.; Derisi, J. L. Temporal Analysis of the Honey Bee Microbiome Reveals Four Novel Viruses and Seasonal Prevalence of Known Viruses, Nosema, and Crithidia. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamonje, F. O.; Michuki, G. N.; Braidwood, L. A.; Njuguna, J. N.; Mutuku, J. M.; Djikeng, A.; Harvey, J. J. W.; Carr, J. P. Viral metagenomics of aphids present in bean and maize plots on mixed-use farms in Kenya reveals the presence of three dicistroviruses including a novel Big Sioux River virus - like dicistrovirus. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valles, S. M.; Chen, Y.; Firth, A. E.; Gu, D. M. A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Herrero, S.; Miranda, J. R. De; Ryabov, E. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Iflaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreason, S. A.; Lahey, Z.; Ayala-Ortiz, C.; Simmonds, A. Genome Sequences of Novel I fl aviruses in the Gray Lawn Leafhopper, an Experimental Vector of Corn Stunt Spiroplasma. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- François, S.; Antoine-Lorquin, A.; Kulikowski, M.; Frayssinet, M.; Filloux, D.; Fernandez, E.; Roumagnac, P.; Ogliastro, R. F. 5 and M. Characterisation of the Viral Community Associated with the Alfalfa Weevil ( Hypera postica ) and Its Host Plant, Alfalfa ( Medicago sativa ). Viruses 2021, 13, 1–16.

- Remnant, E. J.; Baty, J. W.; Bulgarella, M.; Dobelmann, J.; Quinn, O.; Gruber, M. A. M.; Lester, P. J. A Diverse Viral Community from Predatory Wasps in Their Native and Invaded Range, with a New Virus Infectious to Honey Bees. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICTV. Genus: Betaricinrhavirus Available online: https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/negative-sense-rna-viruses/w/rhabdoviridae/1657/gegen-betaricinrhavirus (accessed on 20.10.23).

- Simmonds, P.; Becher, P.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E. A.; Meyers, G.; Monath, T.; Muerhoff, S.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-hesse, R.; Smith, D. B.; Stapleton, J. T.; Consortium, I. R. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile : Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaenssens, E. M.; Roux, S.; Brister, J. R.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Kuhn, J. H.; Varsani, A.; Yigang, T.; Reyes, A.; Lood, C.; Lefkowitz, E. J.; Sullivan, M. B.; Edwards, R. A.; Simmonds, P.; Rubino, L.; Sabanadzovic, S.; Krupovic, M.; Dutilh, B. E. Guidelines for public database submission of uncultivated virus genome sequences for taxonomic classification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, July, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EVANS, H. E. A review of prey choice in bembicine sand wasps (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2002, 31, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Abundance of viruses (top) and virus-containing reads (bottom) in each studied pool. Distinct virus groups are marked by color. If only individual fragments of virus genome are obtained, the section is marked by crosses. Pools of tabanids from Primorsky Krai and Ryazan Region are indicated in red and black, respectively, in the X-axis caption.

Figure 1.

Abundance of viruses (top) and virus-containing reads (bottom) in each studied pool. Distinct virus groups are marked by color. If only individual fragments of virus genome are obtained, the section is marked by crosses. Pools of tabanids from Primorsky Krai and Ryazan Region are indicated in red and black, respectively, in the X-axis caption.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the negev-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the negev-like viruses genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the negev-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the negev-like viruses genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye Haematopota flavi-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye Haematopota flavi-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye Haematopota flavi-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye Haematopota flavi-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the xinmo-like viruses. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of the Xinmoviridae family and related viruses. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the RdRp, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Taxa recognized by ICTV are labeled. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the xinmo-like viruses genomes. Grey bar on the genome represents a gap in the sequence. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the xinmo-like viruses. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of the Xinmoviridae family and related viruses. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the RdRp, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Taxa recognized by ICTV are labeled. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the xinmo-like viruses genomes. Grey bar on the genome represents a gap in the sequence. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the toti-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of the toti-like viruses. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the RdRp, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Trees are midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Volxa Hybomitra toti-like virus and Medvezhye Chrysops toti-like virus genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the toti-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of the toti-like viruses. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the RdRp, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Trees are midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Volxa Hybomitra toti-like virus and Medvezhye Chrysops toti-like virus genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the narna-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B, C) Scheme of the narna-like viruses genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the narna-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B, C) Scheme of the narna-like viruses genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the solemo-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B, C) Scheme of the solemo-like virus genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green. The gap in the Komarovka Hybomitra solemo-like virus is marked on its genome.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the solemo-like viruses described in the study. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B, C) Scheme of the solemo-like virus genomes. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green. The gap in the Komarovka Hybomitra solemo-like virus is marked on its genome.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye pound Haematopota permuto-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Big Sioux River virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the ORF1, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Virus strain discovered in the current article is marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Big Sioux River virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Big Sioux River virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the ORF1, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Virus strain discovered in the current article is marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Big Sioux River virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 10.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye Chrysops ifla-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye Chrysops ifla-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Figure 10.

Phylogenetic relationships and genomic structure of the Medvezhye Chrysops ifla-like virus. (A) Phylogenetic relationships. Analysis was performed using amino acid sequences of the polyprotein, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Nodes with >70% bootstrap support are marked with a circle. Scale bar represents the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Viruses discovered in the current article are marked in red. Tree is midpoint-rooted for the clarity of the figure only. (B) Scheme of the Medvezhye Chrysops ifla-like virus genome. RdRp-encoding ORF is marked in green.

Table 1.

Collection and pooling of tabanids.

Table 1.

Collection and pooling of tabanids.

| Pool Number |

Region |

Species in the pool |

Specimen Number |

Location |

Date |

| 1 |