Submitted:

06 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

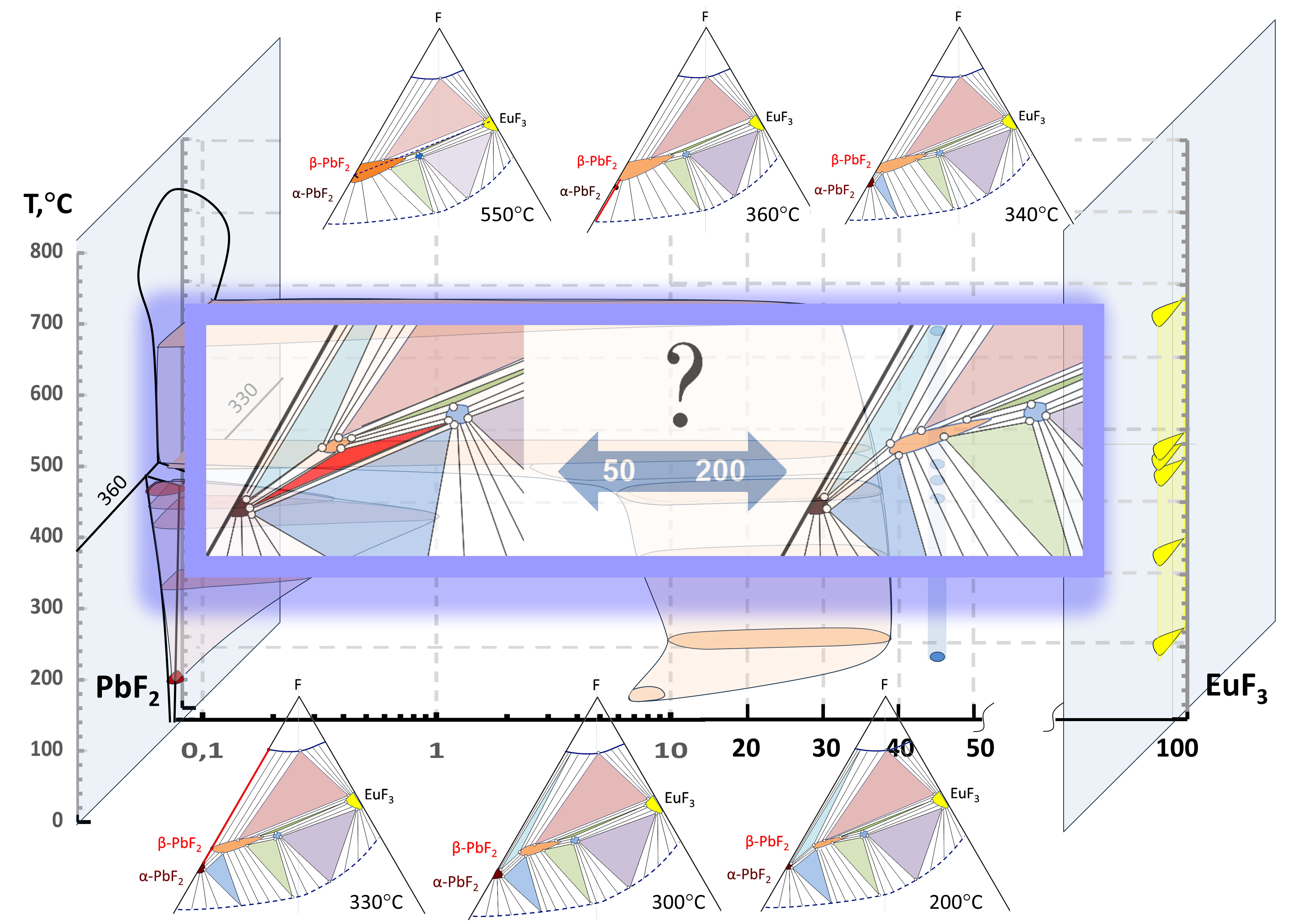

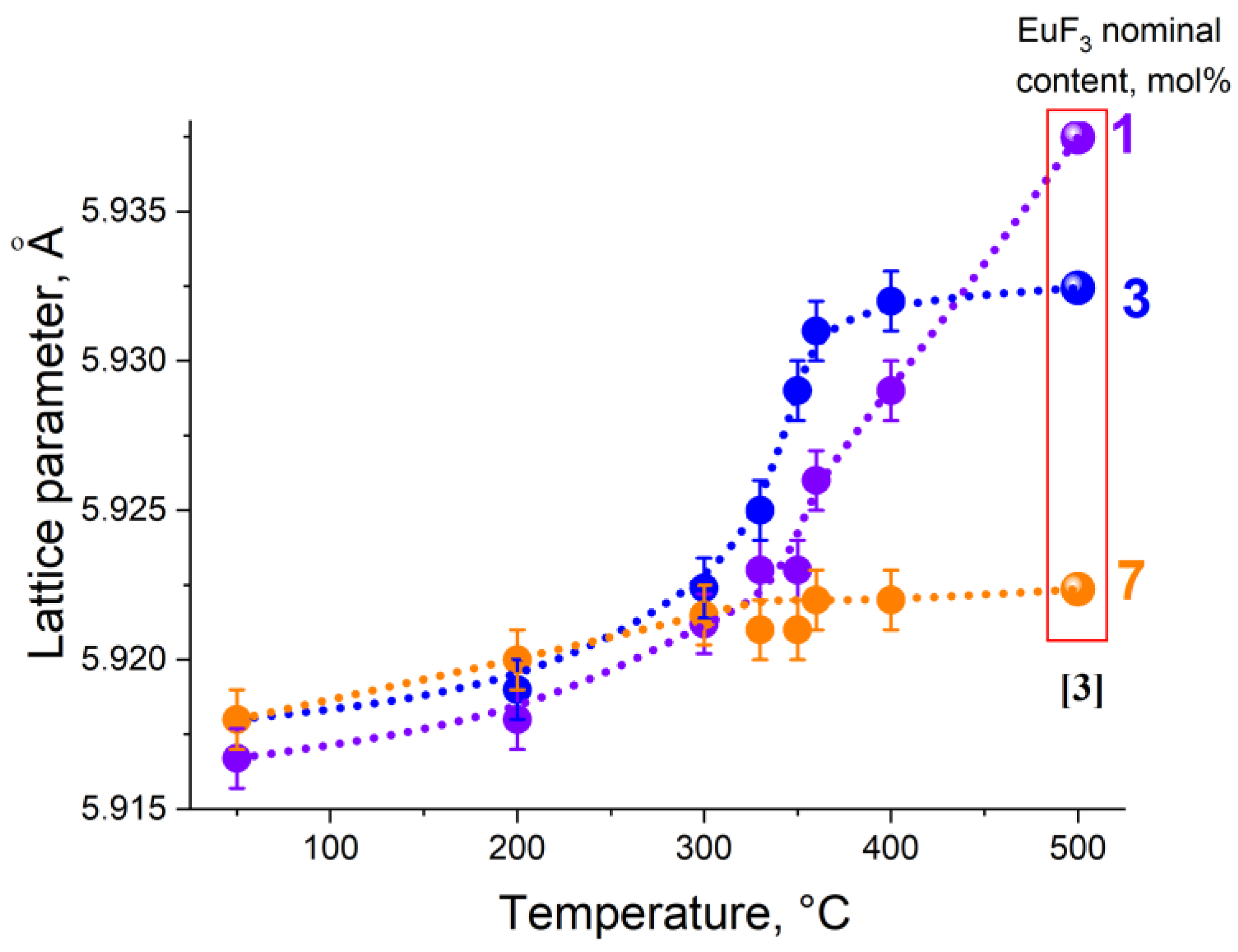

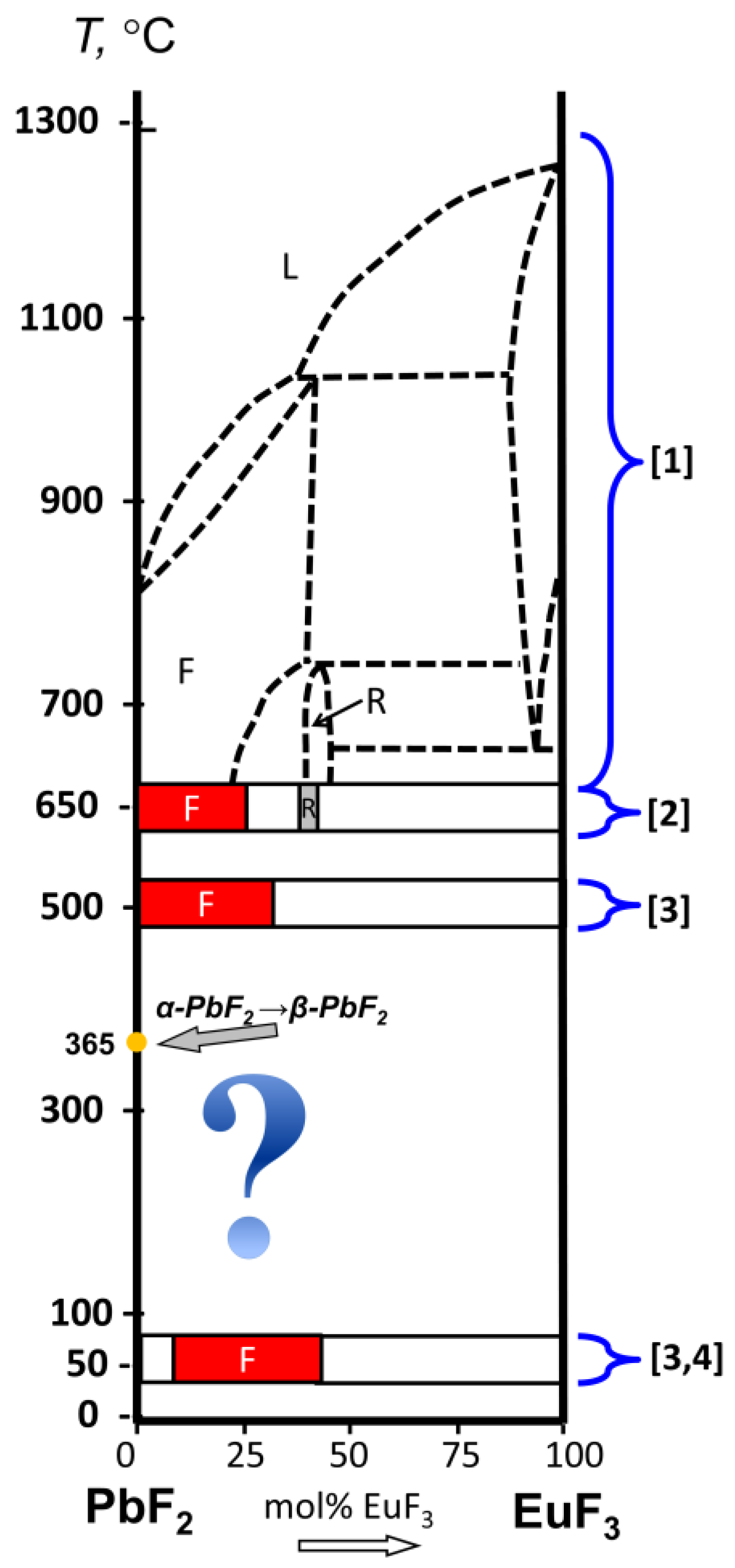

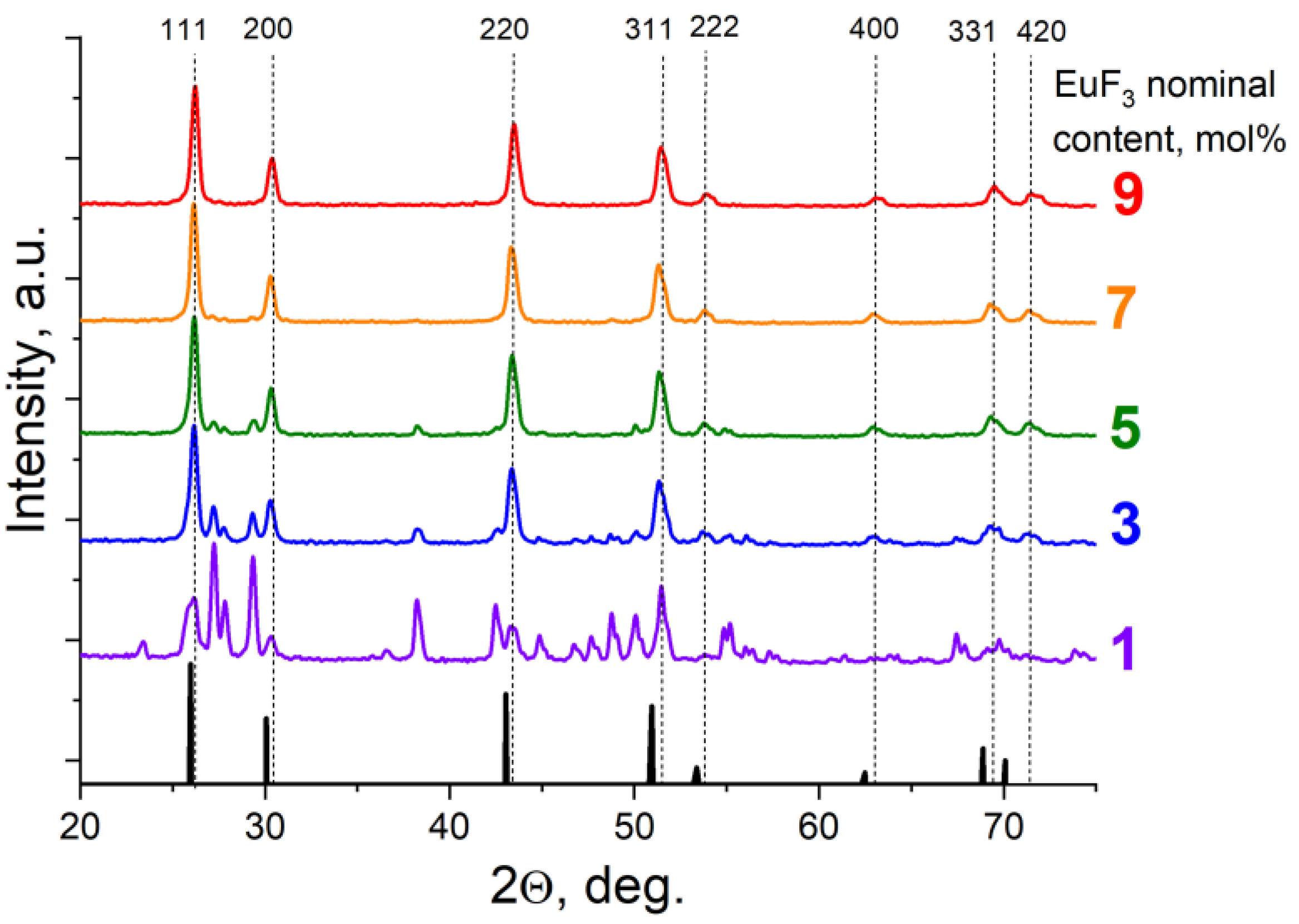

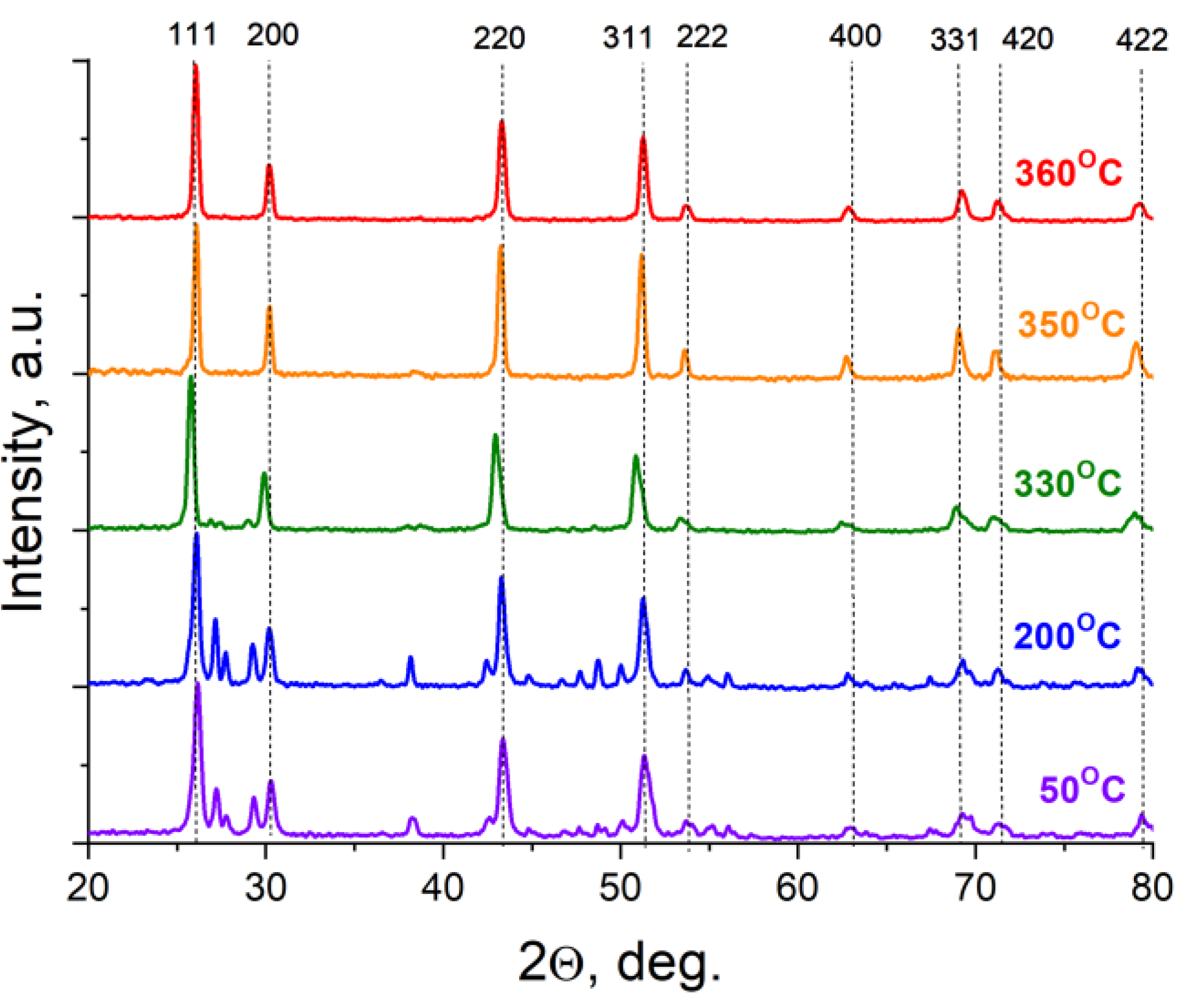

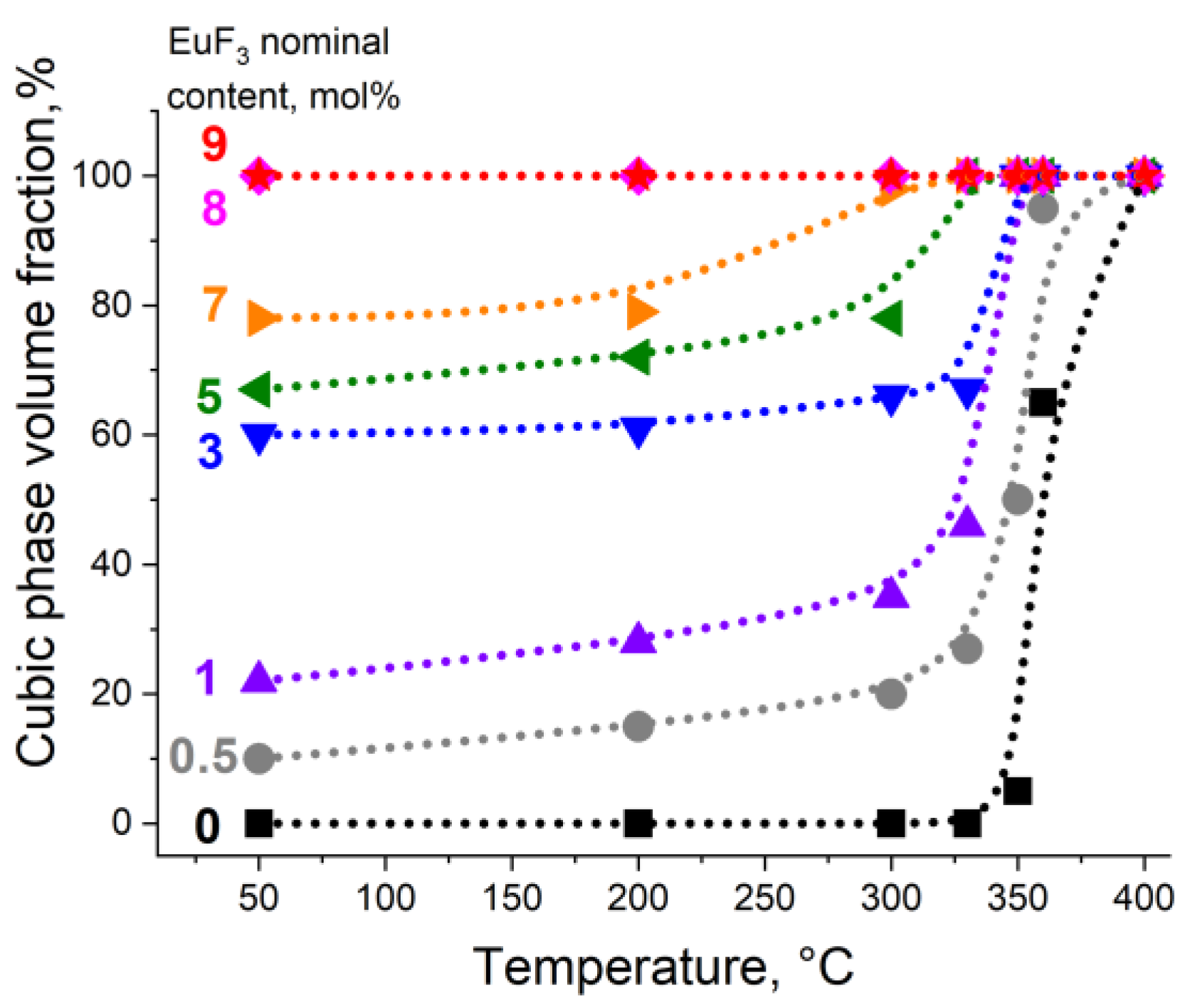

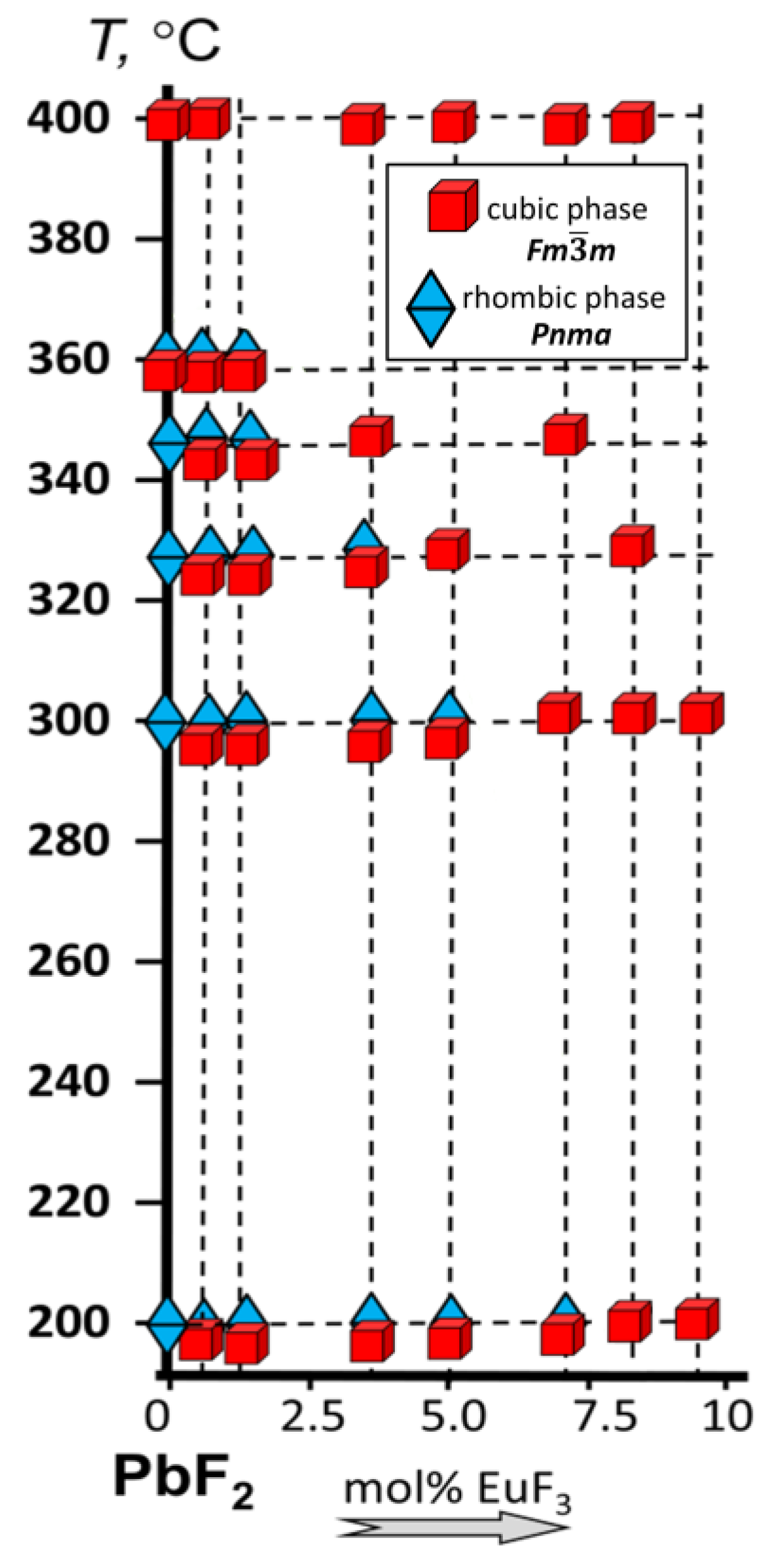

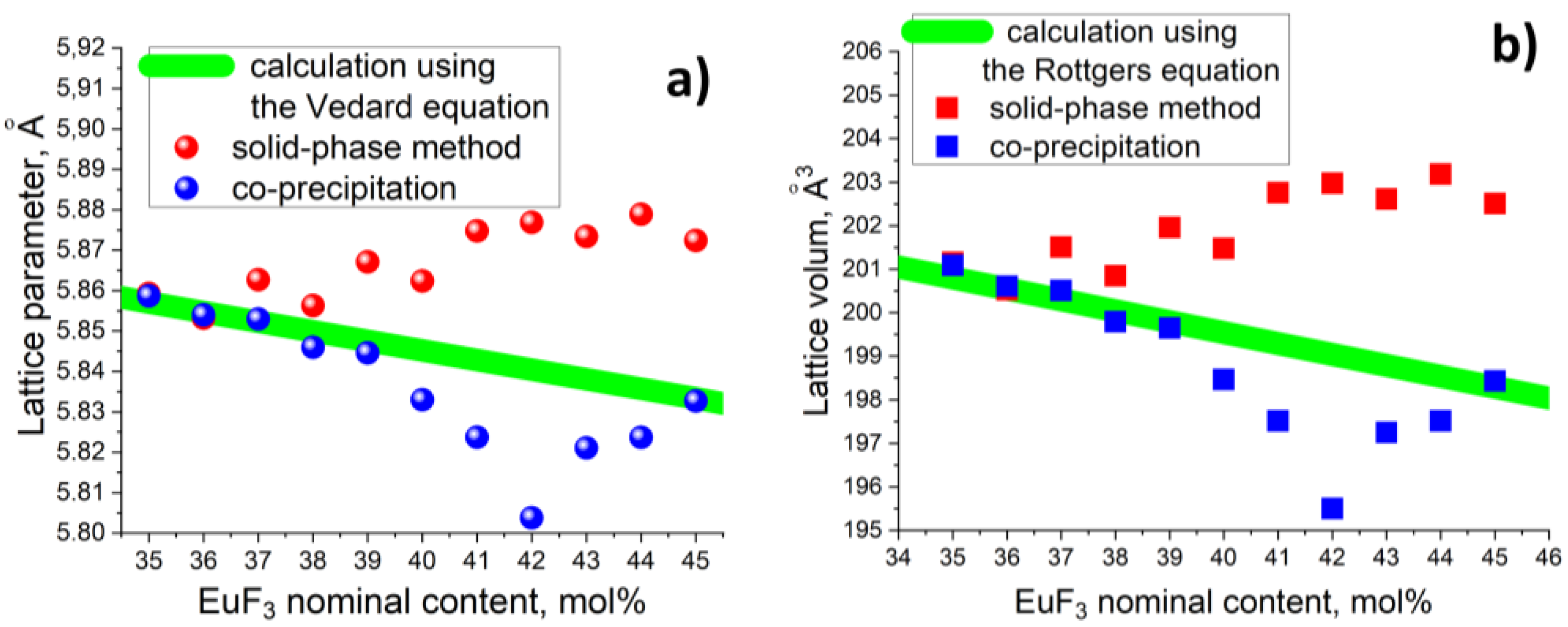

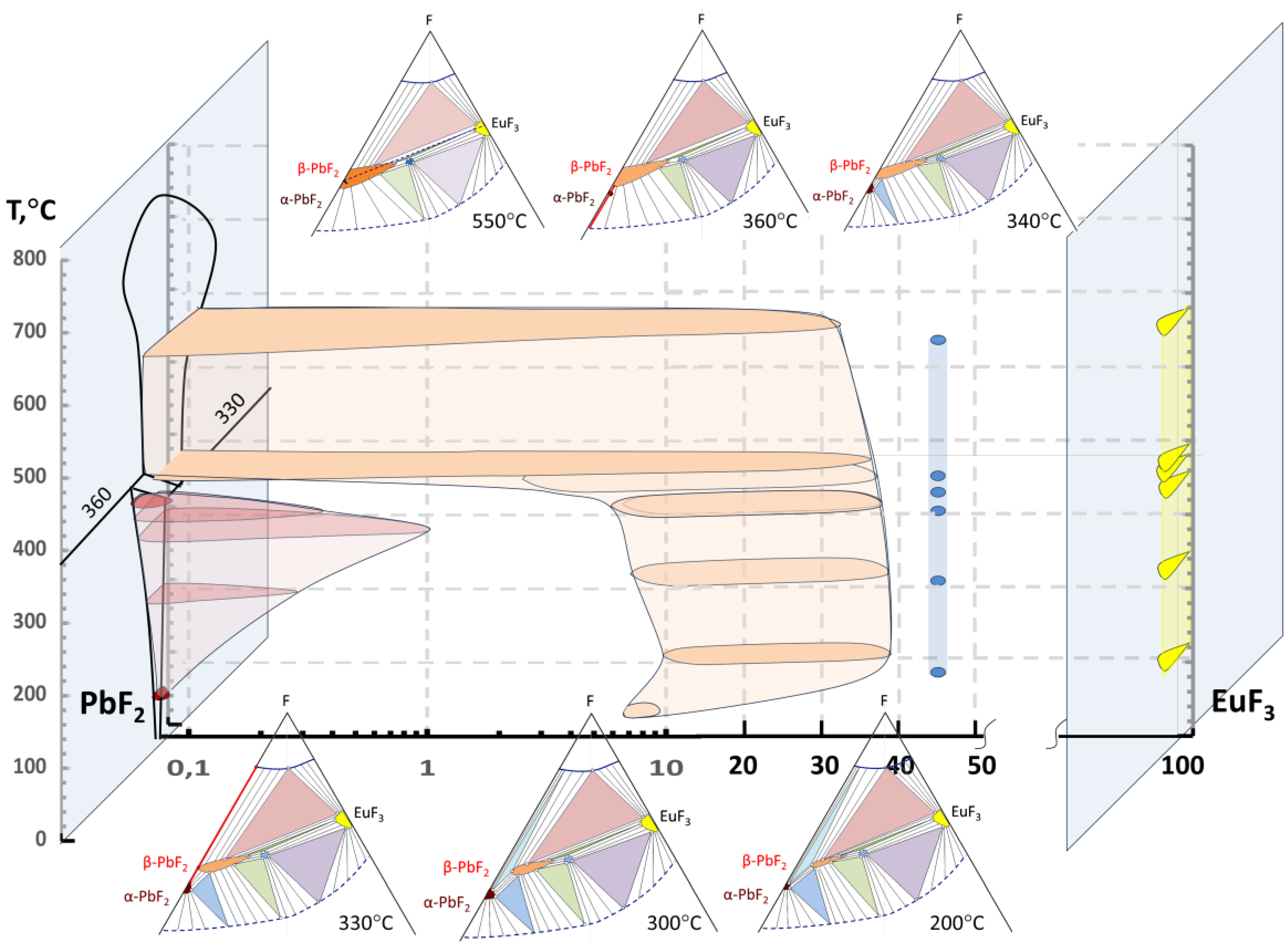

3.1. Position of the Solvus line on the PbF2-EuF3 Diagram

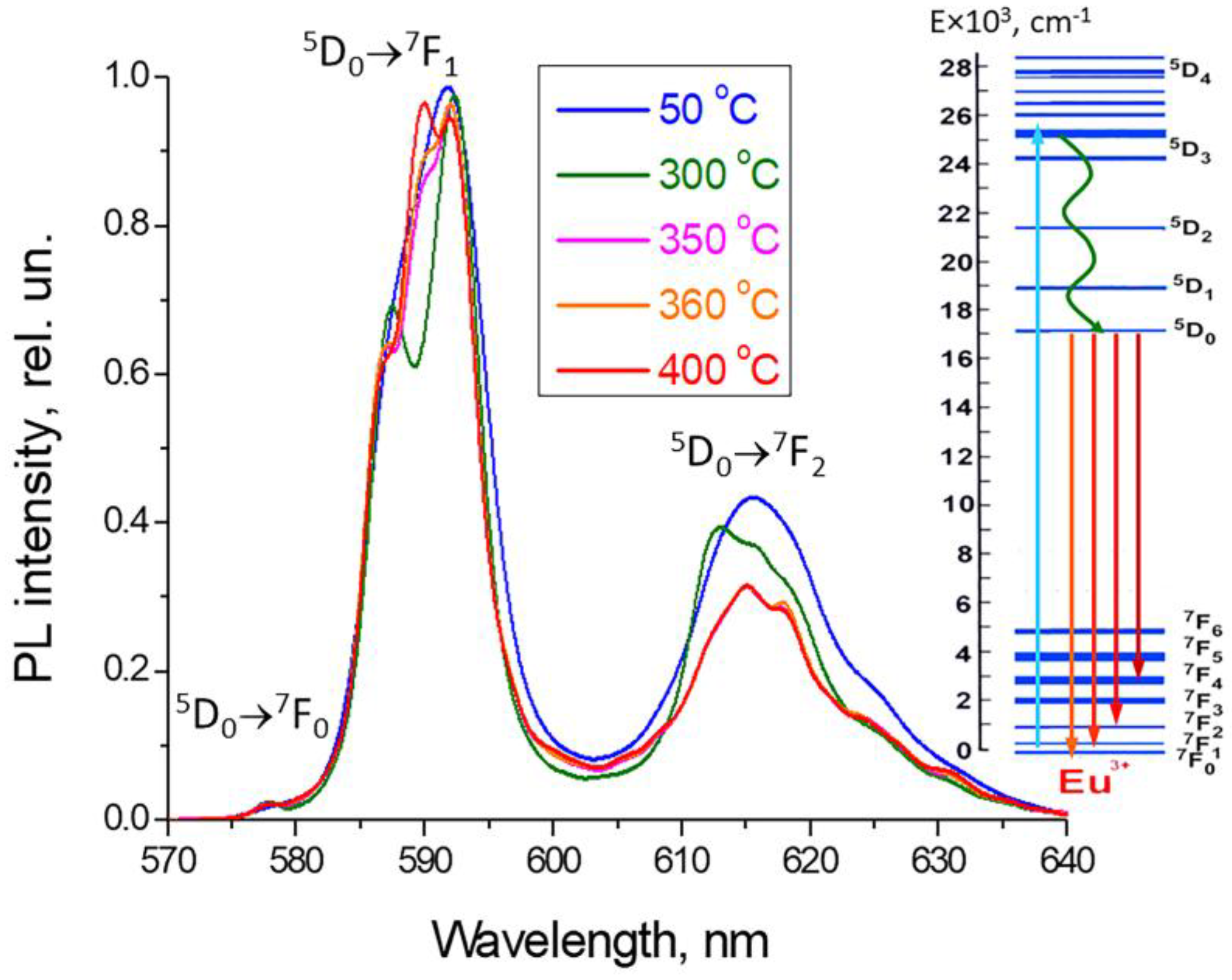

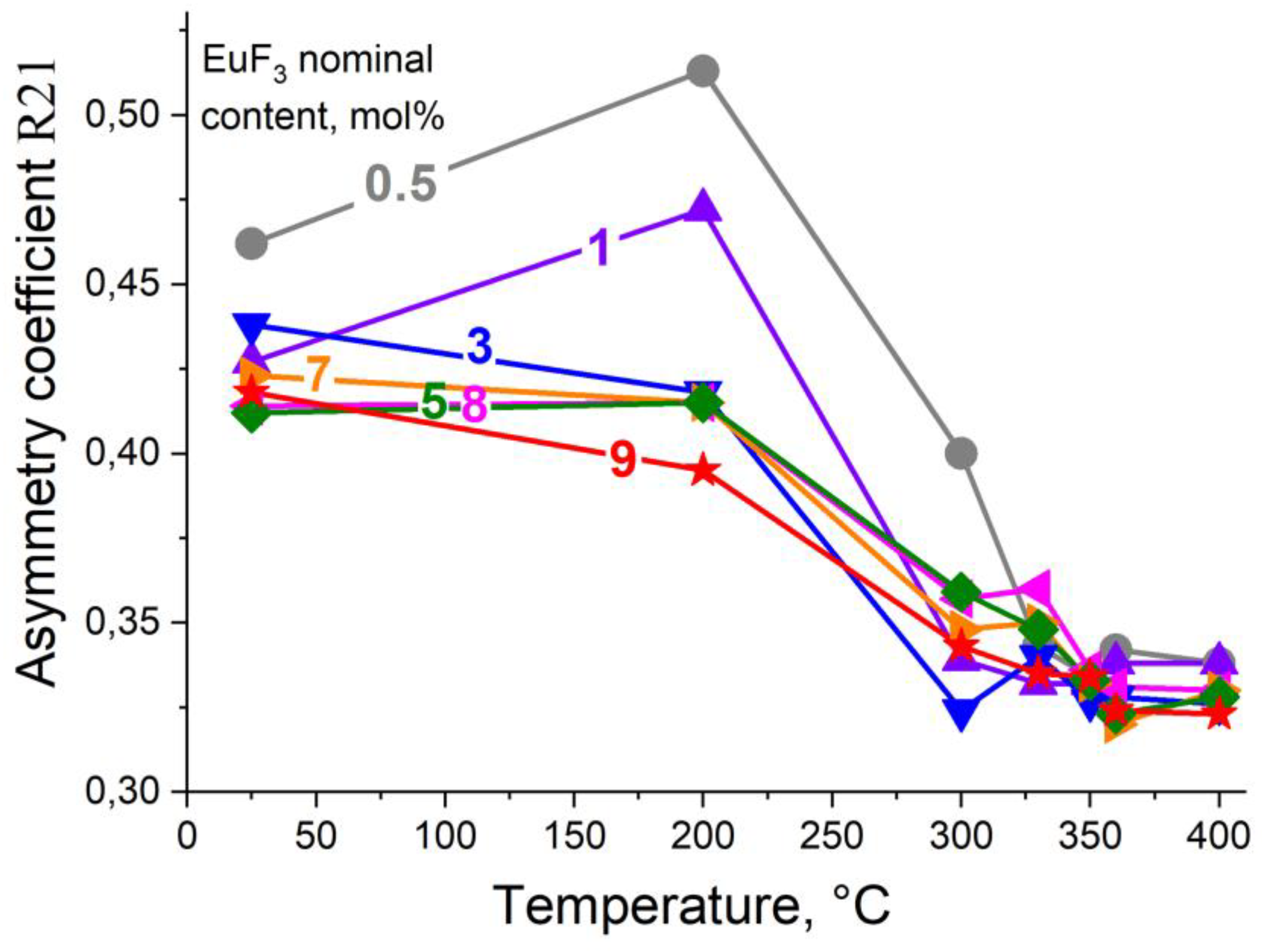

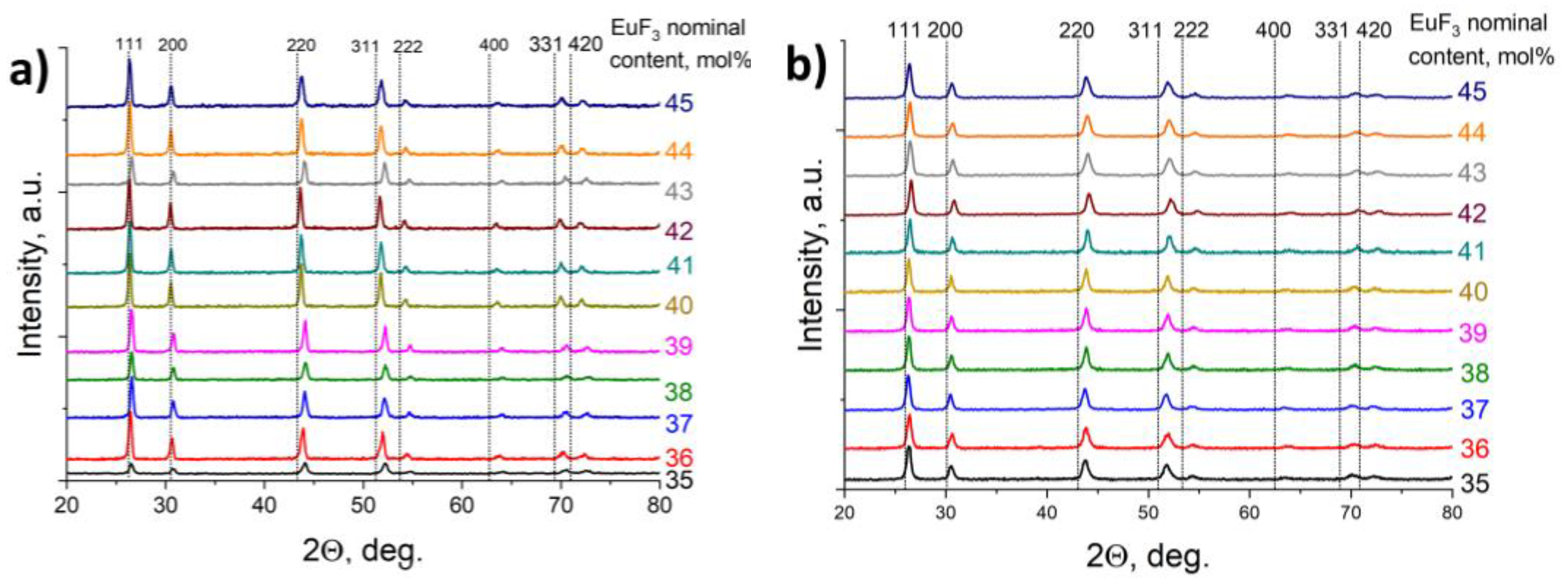

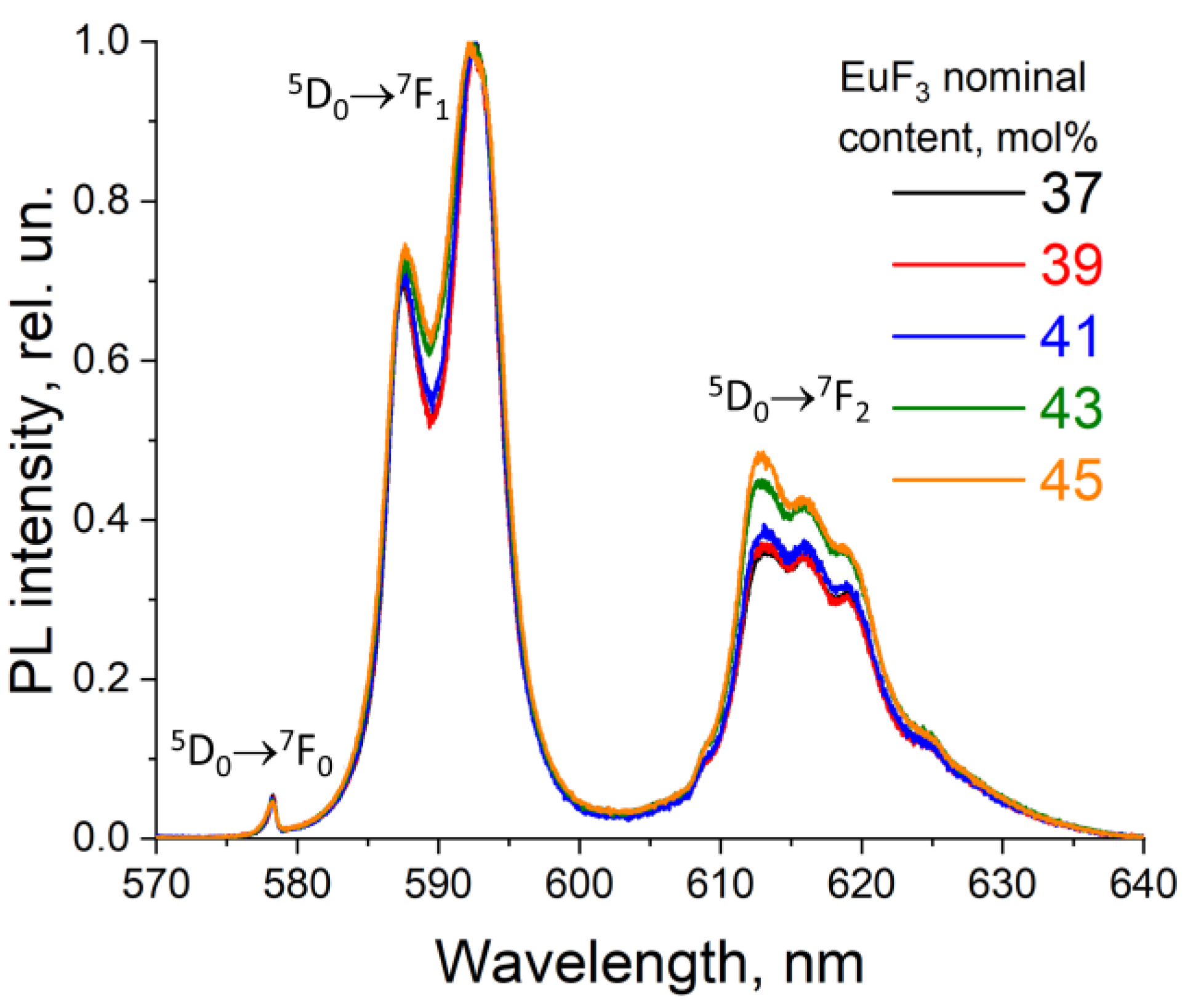

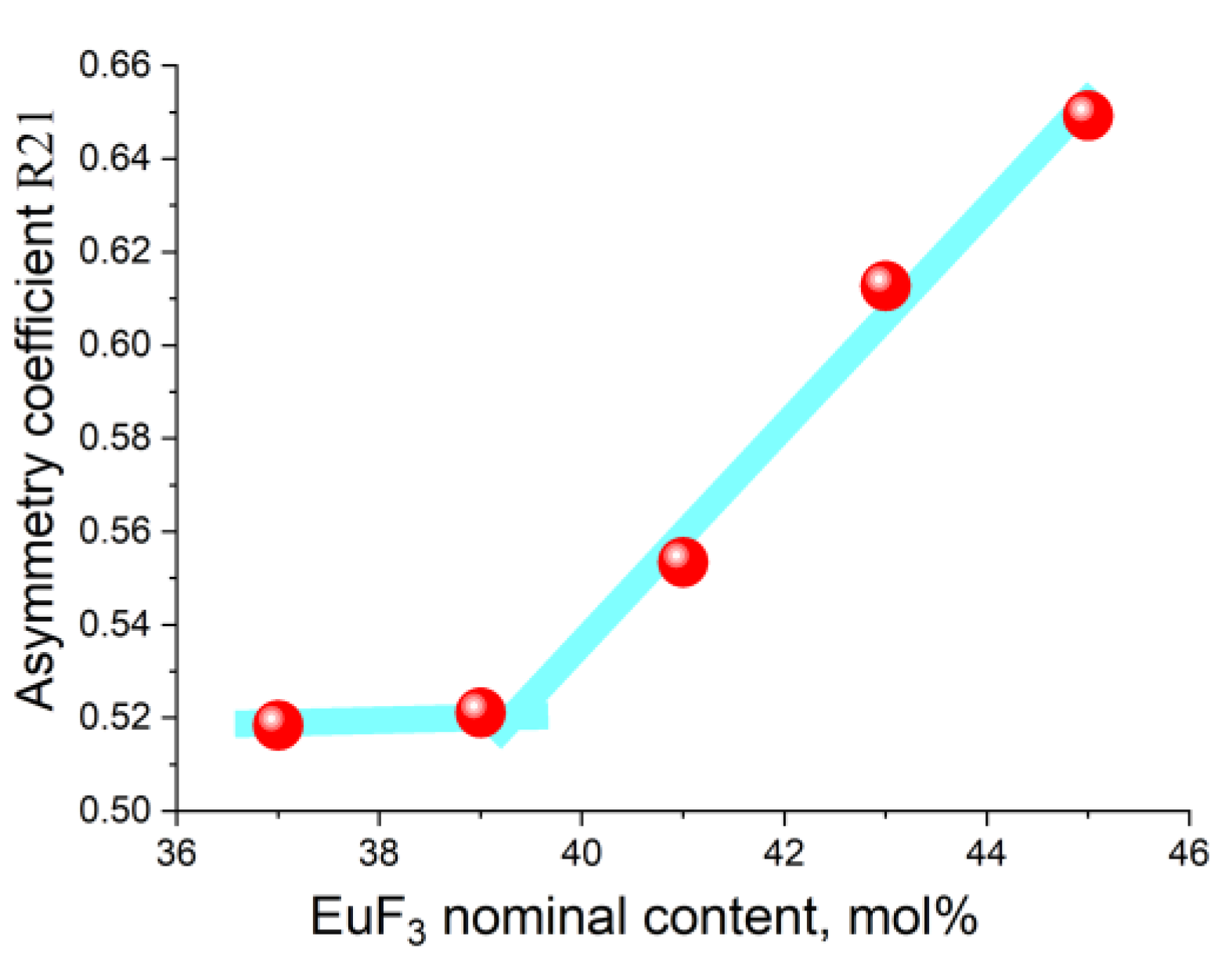

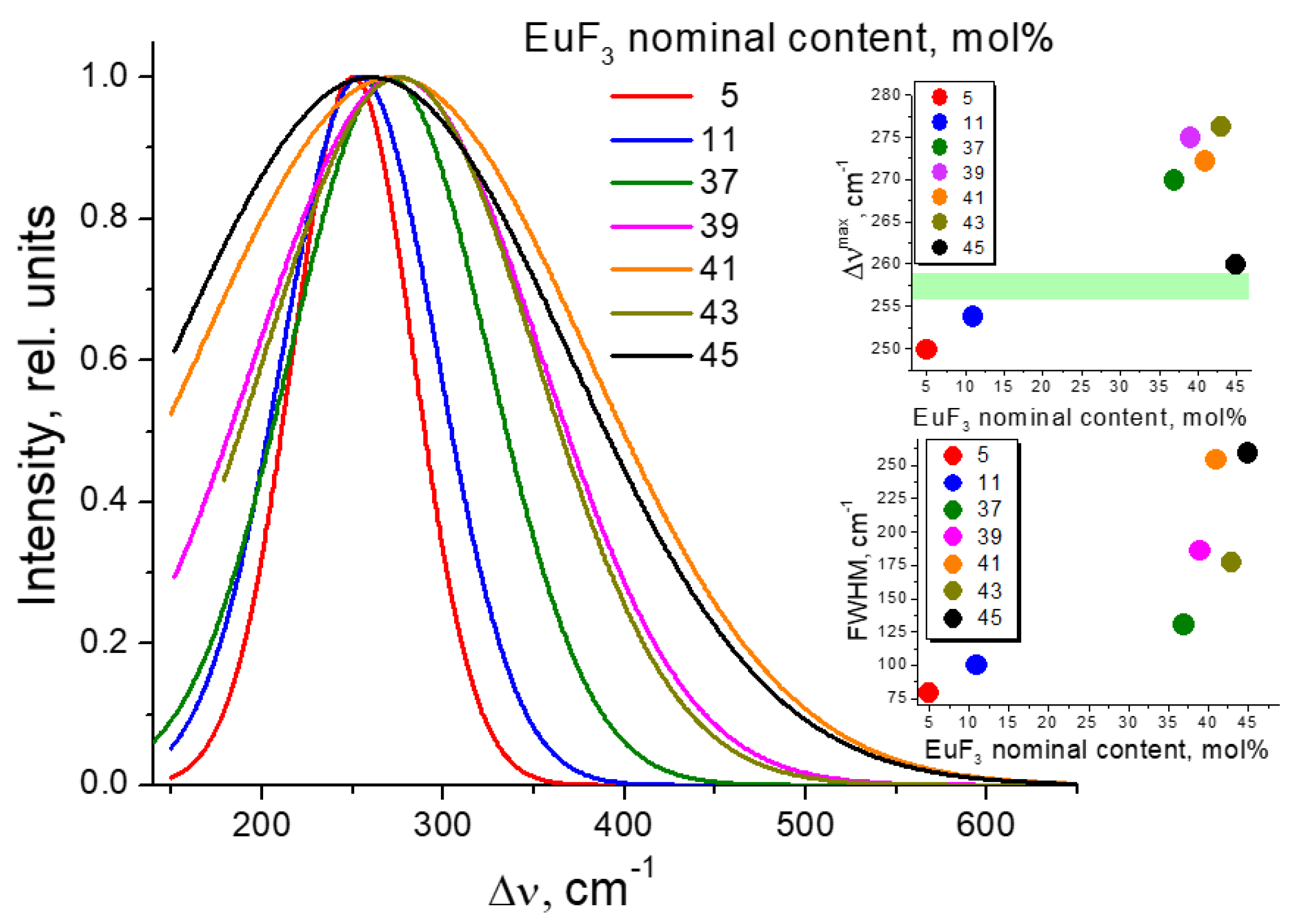

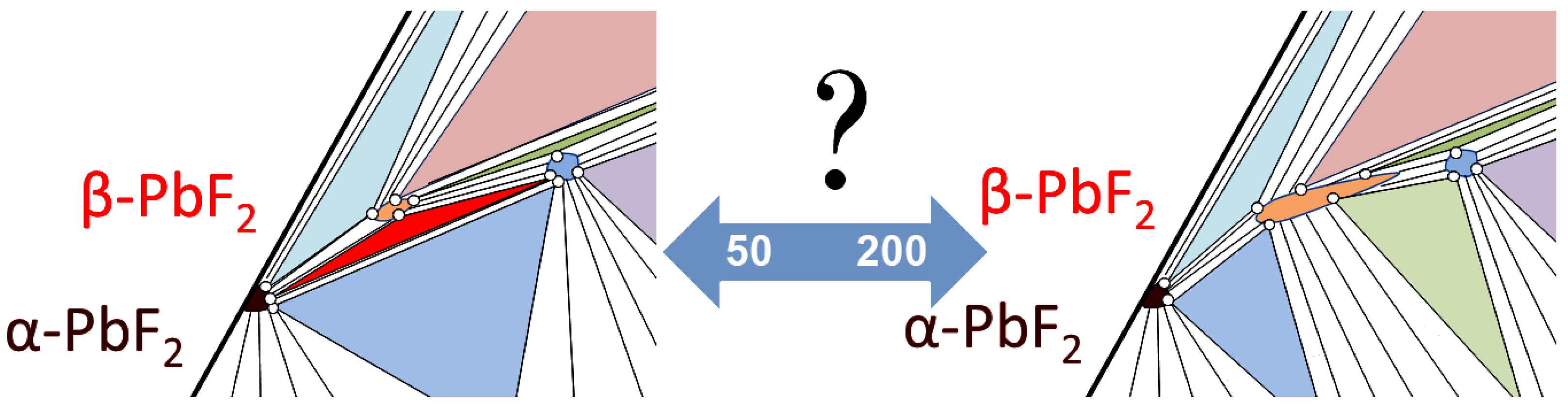

3.2. Determining the Existence Region of the Rhombohedral R-Phase in the PbF2-EuF3 System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ntoupis, V.; Linardatos, D.; Saatsakis, G.; Kalyvas, N.; Bakas, A.; Fountos, G.; Kandarakis, I.; Michail, C.; Valais, I. Response of Lead Fluoride (PbF2) Crystal under X-Ray and Gamma Ray Radiation. Photonics 2023, 10 (1), 57. [CrossRef]

- PbF2 - Lead Fluoride Scintillator Crystal | Advatech UK https://www.advatech-uk.co.uk/pbf2.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- A roadmap for sole Cherenkov radiators with SiPMs in TOF-PET – IOPscience https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1361-6560/ac212a (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cantone, C.; Carsi, S.; Ceravolo, S.; Di Meco, E.; Diociaiuti, E.; Frank, I.; Kholodenko, S.; Martellotti, S.; Mirra, M.; Monti-Guarnieri, P.; Moulson, M.; Paesani, D.; Prest, M.; Romagnoni, M.; Sarra, I.; Sgarbossa, F.; Soldani, M.; Vallazza, E. Beam Test, Simulation, and Performance Evaluation of PbF2 and PWO-UF Crystals with SiPM Readout for a Semi-Homogeneous Calorimeter Prototype with Longitudinal Segmentation. Front. Phys. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kurosawa, S.; Yokota, Y.; Yanagida, T.; Yoshikawa, A. Optical and Scintillation Property of Ce, Ho and Eu-Doped PbF2. Radiat. Meas. 2013, 55, 120–123. [CrossRef]

- Buchinskaya, I. I.; Fedorov, P. P. Lead Difluoride and Related Systems. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2004, 73 (4), 371–400. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A. K.; Patwe, S. J.; Achary, S. N.; Mallia, M. B. Phase Relation Studies in Pb1−xM′xF2+x Systems (0.0⩽x⩽1.0; M′=Nd3+, Eu3+ and Er3+). J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177 (4–5), 1746–1757. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, O. B.; Mayakova, M. N.; Smirnov, V. A.; Runina, K. I.; Avetisov, R. I.; Avetissov, I. C. Luminescent Properties of Solid Solutions in the PbF2-EuF3 and PbF2–ErF3 Systems. J. Lumin. 2021, 238, 118262. [CrossRef]

- Sevostjanova, T. S.; Khomyakov, A. V.; Mayakova, M. N.; Voronov, V. V.; Petrova, O. B. Luminescent Properties of Solid Solutions in the PbF2–Euf3 System and Lead Fluoroborate Glass Ceramics Doped with Eu3+ Ions. Opt. Spectrosc. 2017, 123 (5), 733–742. [CrossRef]

- Savikin, A. P.; Egorov, A. S.; Budruev, A. V.; Perunin, I. Y.; Grishin, I. A. Visualization of 1.908-Μm Radiation of a Tm:YLF Laser Using PbF2-Based Ceramics Doped with Ho3+ Ions. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2016, 42 (11), 1083–1086. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Niu, X.; Zhang, P.; Tan, H.; Ma, F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Hang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Z. Energy Transfer and Cross-Relaxation Induced Efficient 2.78 Μm Emission in Er3+/Tm3+: PbF2 Mid-Infrared Laser Crystal. Crystals 2021, 11 (9), 1024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Su, Z.; Xu, J.; Xin, K.; Hang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yin, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H. Efficiently Strengthen and Broaden 3 Μm Fluorescence in PbF2 Crystal by Er3+/Ho3+ as Co-Luminescence Centers and Pr3+ Deactivation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 811, 152027. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Yin, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Hang, Y.; Chen, Z. Sensitization and Deactivation Effects of Nd 3+ on the Er 3+ : 27 Μm Emission in PbF 2 Crystal. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9 (4), 1698. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, P.; Niu, X.; Liao, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, S.; Hang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yin, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z. Ultra-Broadband and Enhanced near-Infrared Emission in Bi/Er Co-Doped PbF2 Laser Crystal. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 895, 162704. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin N. I.; Ivanovskaya N. A.; Buchinskaya I. I. Ionic Conductivity of Cold Pressed Nanoceramics Pr-=SUB=-0.9-=/SUB=-Pb-=SUB=-0.1-=/SUB=-F-=SUB=-2.9-=/SUB=- Obtained by Mechanosynthesis of Components. Phys. Solid State 2023, 65 (1), 101. [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, B. P. The Rare Earth Trifluorides: The High Temperature Chemistry of the Rare Earth Trifluorides 2. Introduction to Materials Science of Multicomponent Metal Fluoride Crystals; Arxius de les seccions de ciències; Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 2000.

- Achary, S. N.; Patwe, S. J.; Tyagi, A. K. Powder XRD Study of Ba 4 Eu 3 F 17 : A New Anion Rich Fluorite Related Mixed Fluoride. Powder Diffr. 2002, 17 (3), 225–229. [CrossRef]

- Dombrovski, E. N.; Serov, T. V.; Abakumov, A. M.; Ardashnikova, E. I.; Dolgikh, V. A.; Van Tendeloo, G. The Structural Investigation of Ba4Bi3F17. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177 (1), 312–318. [CrossRef]

- Patwe, S..; Achary, S..; Tyagi, A.. Synthesis and Characterization of Ba1−xErxF2+x (0.00≤x≤1.00). Mater. Res. Bull. 2002, 37 (14), 2243–2253. [CrossRef]

- Patwe, S. J.; Achary, S. N.; Tyagi, A. K. Synthesis and Characterization of Y1-XPb2+1.5xF7 (−1.33 ≤ x ≤ 1.0). Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36 (3–4), 597–605. [CrossRef]

- Loiko, P.; Rytz, D.; Schwung, S.; Pues, P.; Jüstel, T.; Doualan, J.-L.; Camy, P. Watt-Level Europium Laser at 703 Nm. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46 (11), 2702. [CrossRef]

- Kopylov, N.I.; Polyvyannyi, I.R.; Ivakina, L.P.; Antonuk, V.I. System ZnS-Na2S Russian J. Neorg.Khimii. 1978, 23(11), 3095-3101.

- Mayakova, M. N.; Voronov, V. V.; Iskhakova, L. D.; Kuznetsov, S. V.; Fedorov, P. P. Low-Temperature Phase Formation in the BаF2-CeF3 System. J. Fluor. Chem. 2016, 187, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Karimov, D. N.; Sorokin, N. I.; Chernov, S. P.; Sobolev, B. P. Growth of MgF2 Optical Crystals and Their Ionic Conductivity in the As-Grown State and after Partial Pyrohydrolysis. Crystallogr. Reports 2014, 59 (6), 928–932. [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, Y.; Ueda, K.; Katsumata, T.; Noda, Y. Low-Temperature Formation of Pb2OF2 with O/F Anion Ordering by Solid State Reaction. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 277, 363–367. [CrossRef]

- Strekalov, P. V.; Mayakova, M. N.; Runina, K. I.; Petrova, O. B. Organic Phosphor and Lead Fluoride Based Luminescent Hybrids. Tsvetnye Met. 2021, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Borik, M. A.; Gerasimov, M. V.; Kulebyakin, A. V.; Larina, N. A.; Lomonova, E. E.; Milovich, F. O.; Myzina, V. A.; Ryabochkina, P. A.; Sidorova, N. V.; Tabachkova, N. Y. Structure and Phase Transformations in Scandia, Yttria, Ytterbia and Ceria-Doped Zirconia-Based Solid Solutions during Directional Melt Crystallization. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 844, 156040. [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, N. I. Molar Volume Correlation between Nonstoichiometric M1 − XRxF2 + x (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5) and Ordered MmRnF2m + 3n (m/n = 8/6, 9/5) Phases in Systems MF2–RF3 (M = Ca, Sr, Ba, Pb; and R = Rare-Earth Elements). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 64 (3), 351–356. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. The Raman Effect: Applications; The Raman Effect; M. Dekker, 1971.

- Bazhenov, A. V.; Smirnova, I. S.; Fursova, T. N.; Maksimuk, M. Y.; Kulakov, A. B.; Bdikin, I. K. Optical Phonon Spectra of PbF2 Single Crystals. Phys. Solid State 2000, 42 (1), 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds; Wiley, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Thangadurai, P.; Ramasamy, S.; Kesavamoorthy, R. Raman Studies in Nanocrystalline Lead (II) Fluoride. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2005, 17 (6), 863–874. [CrossRef]

- Crystallography Open Database https://www.crystallography.net/cod/1530196.html (accessed on 05 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).