Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Geological and Historical Background

2.3. Materials

2.4. Methodology

2.5. Description of the Segmentation and Validation Workflow

3. Results

3.1. Processing of Flights

3.2. Integration of the LiDAR–SLAM Point Cloud

3.3. Videogrammetry

3.4. Generation of Point Clouds and Meshes

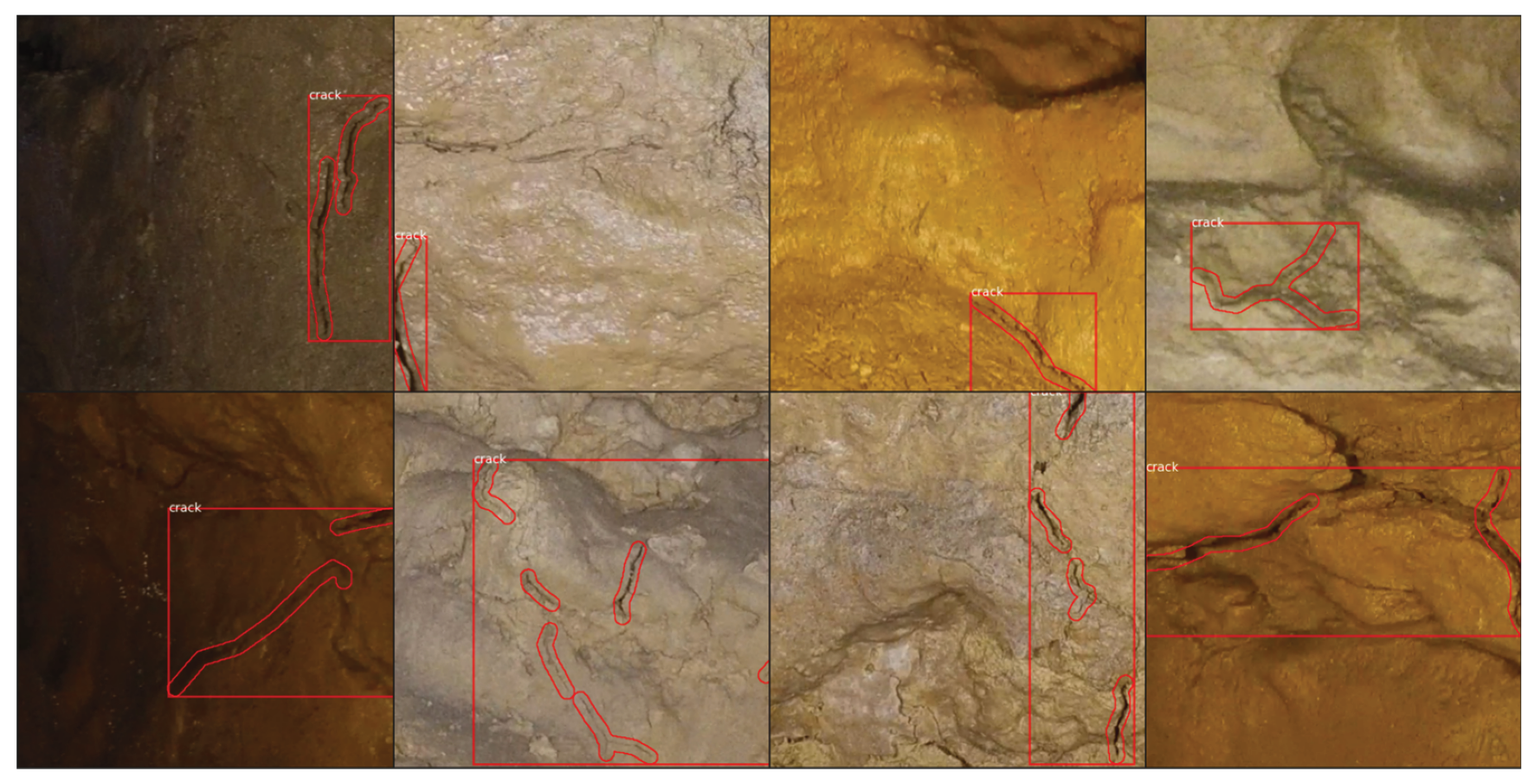

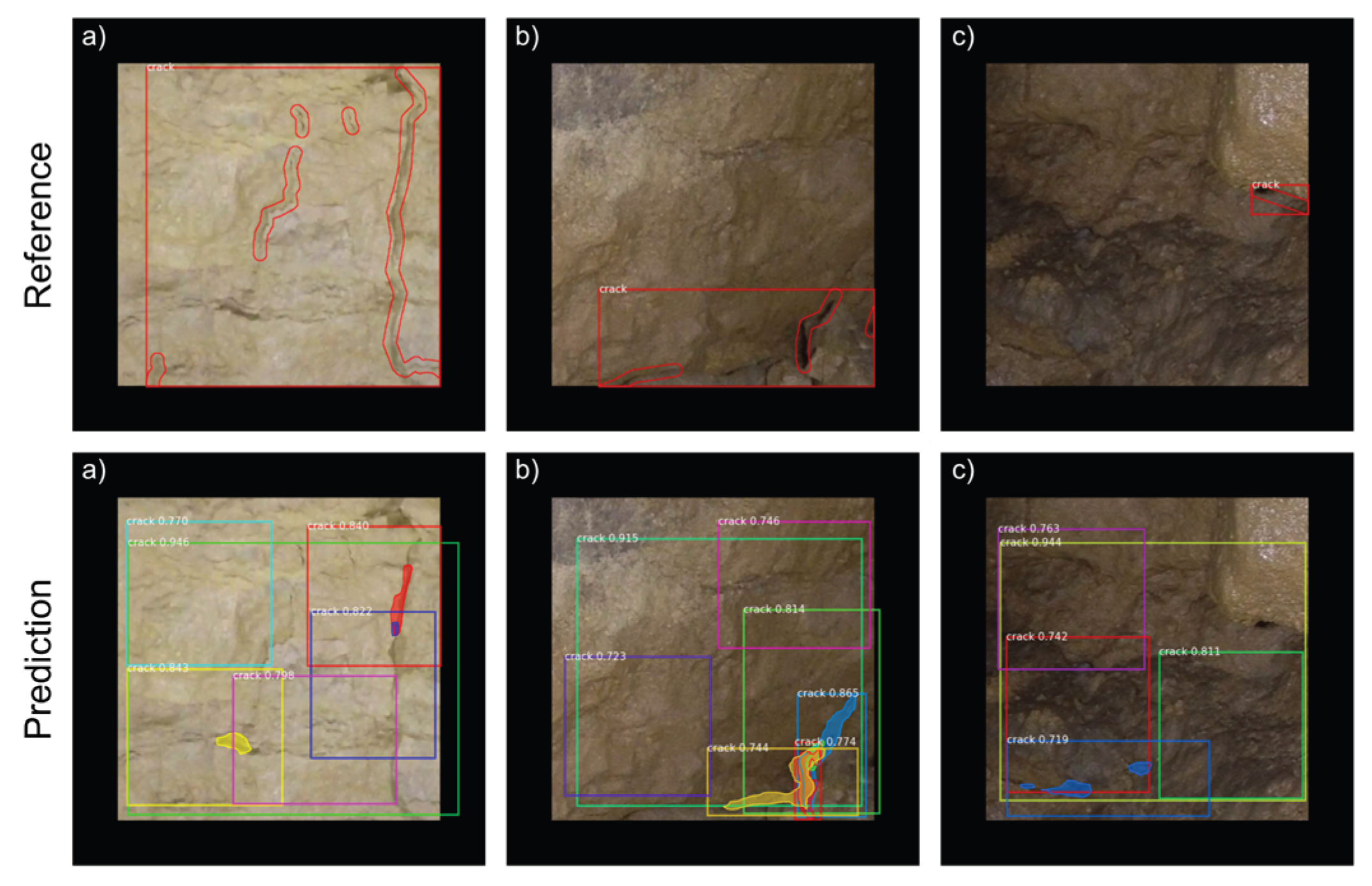

3.5. Segmentation for Crack Detection

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the AI Model for Automated Crack Detection

4.2. Integration of Geospatial Data into a Digital Twin Framework: Infrastructure and Hierarchical Model

4.3. Point Cloud Integration and Web-Based Visualization

4.4. Mesh Integration and Semantic Enrichment

4.5. Deployment Strategy and System Scalability

4.6. Overall Interpretation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLI | Command-Line Interface |

| CNIG | Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica |

| COCO | Common Objects in Context dataset |

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| FPS | Frames per Second |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| GLB | Binary form of glTF |

| glTF | GL Transmission Format |

| IGN | Instituto Geográfico Nacional |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| KTX2 | Khronos Texture 2.0 |

| MVS | Multi-View Stereo |

| NGINX | NGINX Web Server |

| PDAL | Point Data Abstraction Library |

| PNOA | Plan Nacional de Ortofotografía Aérea |

| POI | Point Of Interest |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RoI | Region of Interest |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| ToF | Time-of-Flight |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Fatás Monforte, P. Altamira, símbolo, identidad y marca. In El patrimonio cultural como símbolo. Actas del Simposio Internacional; Garrote, L., Ed.; Fundación del Patrimonio Histórico de Castilla y León: Valladolid, 2011; 163–186.

- de las Heras, C.; Montes, R.; Lasheras, J.A. Altamira: nivel gravetiense y cronología de su arte rupestre. In Pensando el Gravetiense: nuevos datos para la región cantábrica en su contexto peninsular y pirenaico; de las Heras, C., Lasheras, J.A., Arrizabalaga, Á., de la Rasilla, M., Eds.; Monografías del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, 2013, 476–491. Madrid.

- Sanz de Sautuola, M. Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander; Imprenta y Litografía de Telesforo Martínez: Santander, 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Lasheras, J.A. El arte paleolítico de Altamira. In Redescubrir Altamira; Lasheras, J.A., Ed.; Turner: Madrid, 2002; 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lasheras, J.A.; de las Heras, C.; Fatás Monforte, P. El nuevo museo de Altamira. Boletín de la Sociedad de Investigación del Arte Rupestre de Bolivia 2002, 16, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lasheras, J.A.; de las Heras, C. Estudio introductorio a Sanz de Sautuola, M. 1880. Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander. In Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la Provincia de Santander; Botín, E., Ed.; Grupo Santander: Madrid, 2004.

- Lasheras, J.A.; de las Heras, C.; Montes, R.; Rasines, P.; Fatás Monforte, P. La Altamira del siglo XXI (el nuevo Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira). Patrimonio 2002, 23–34.

- Fatás Monforte, P.; Lasheras Corruchaga, J.A. La cueva de Altamira y su museo / The cave of Altamira and its museum. Cuadernos de Arte Rupestre 2014, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moral, S.; Cuezva, S.; Fernández Cortés, Á.; Janices, I.; Benavente, D.; Cañaveras, J.C.; González Grau, J.M.; Jurado, V.; Laiz Trobajo, L.; Portillo Guisado, M. del C.; et al. Estudio integral del estado de conservación de la cueva de Altamira y su arte paleolítico (2007–2009). Perspectivas futuras de conservación; Monografías del Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- Sánchez, M.A.; Foyo, A.; Tomillo, C.; Iriarte, E. Geological Risk Assessment of the Area Surrounding Altamira Cave: A Proposed Natural Risk Index and Safety Factor for Protection of Prehistoric Caves. Engineering Geology 2007, 94, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Moral, S.; Cuezva, S.; Garcia-Anton, E.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Elez, J.; Benavente, D.; Cañaveras, J.C.; Jurado, V.; Rogerio-Candelera, M.A.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. Microclimatic Monitoring in Altamira Cave: Two Decadesof Scientific Projects for Its Conservation. In The Conservation of Subterranean Cultural Heritage; CRC Press, 2014.

- Guichen de, G. Programa de Investigación Para La Conservación Preventiva y Régimen de Acceso de La Cueva de Altamira (2012–2014); Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, 2014, 4.

- Bayarri, V.; Prada, A.; García, F.; Ibáñez, M.; Benavente, D. Integration of Remote-Sensing Techniques for the Preventive Conservation of Paleolithic Cave Art in the Karst of the Altamira Cave. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontemps, Z.; Crovadore, J.; Sirieix, C.; Bourges, F.; Gessler, C.; Lefort, F. Dark-Zone Alterations Expand throughout Paleolithic Lascaux Cave despite Spatial Heterogeneity of the Cave Microbiome. Environmental Microbiome 2023, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Cueva de Altamira. Arte Rupestre Cantábrico. Available online: https://www.arterupestrecantabrico.es/cuevas/cueva-de-altamira.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 42, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Fruit Detection for Strawberry Harvesting Robot in Non-Structural Environment Based on Mask-RCNN. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chang, X.; Bian, S. Vehicle-Damage-Detection Segmentation Algorithm Based on Improved Mask RCNN. IEEE access : practical innovations, open solutions 2020, 8, 6997–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Fu, F. Crack Control Optimization of Basement Concrete Structures Using the Mask-RCNN and Temperature Effect Analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, Z.; Nesheli, S.J.; Landis, E.N. Deep Learning-Based Steel Bridge Corrosion Segmentation and Condition Rating Using Mask RCNN and Yolov8. Infrastructures 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Huo, J.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, H.; Shi, Y. An Improved Mask R-CNN Micro-Crack Detection Model for the Surface of Metal Structural Parts. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhage, A.; Eltaher, M.; Raab, T.; Breuß, M.; Raab, A.; Schneider, A. A Modified Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network Approach for the Automated Detection of Archaeological Sites on High-Resolution Light Detection and Ranging-Derived Digital Elevation Models in the North German Lowland. Archaeological Prospection 2021, 28, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatır, M.E.; İnce, İ.; Korkanç, M. Intelligent Detection of Deterioration in Cultural Stone Heritage. Journal of building engineering 2021, 44, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarri, V.; Prada, A.; García, F. A Multimodal Research Approach to Assessing the Karst Structural Conditions of the Ceiling of a Cave with Palaeolithic Cave Art Paintings: Polychrome Hall at Altamira Cave (Spain). Sensors 2023, 23, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanics, I.S. for R. Suggested Methods for Rock Characterization, Testing and Monitoring; Brown, E.T., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.A.; Bruschi, V.; Iriarte, E. Evaluación del riesgo geológico en las cuevas de Altamira y Estalactitas. In Monografías del Museo y Centro de Investigación Altamira; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, n.d.

- Hoyos, M.; Bustillo, A.; García, A.; Martín, C.; Ortiz, R.; Suazo, C. Características Geológico-Kársticas de La Cueva de Altamira; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, 1981.

- Lasheras, J.A.; Heras, C.; Prada, A.; Fatás, P. La Conservación de Altamira Como Parte de Su Gestión. ARKEOS 2014, 37, 2395–2414. [Google Scholar]

- Ouster, Inc. OS0 Ultra-Wide View High-Resolution Imaging Lidar: Datasheet (Rev7, v3.1); Ouster, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, M.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, Ij.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; Bonino da Silva Santos, L.O.; Bourne, P.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Scientific Data 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Bourdev, L.; Girshick, R.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Zitnick, C.L.; Dollár, P. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2014; Fleet, D.; Pajdla, T.; Schiele, B.; Tuytelaars, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8693, pp. 740–755. [CrossRef]

- Jaikumar, P.; Vandaele, R.; Ojha, V. Transfer Learning for Instance Segmentation of Waste Bottles Using Mask R-CNN Algorithm. ArXiv 2022, abs/2204.07437. [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. New Phytologist 1912, 11, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, H. Digital Twin Research on Masonry–Timber Architectural Heritage Pathology Cracks Using 3D Laser Scanning and Deep Learning Model. Buildings 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, M.; Shi, P.; Ren, R.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Yang, H. Crack Detection and Comparison Study Based on Faster R-CNN and Mask r-CNN. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Trabalon, A.; Moreno-Vegas, S.; Estebanez-Campos, M.B.; Nadal-Martinez, F.; Garcia-Vacas, F.; Prado-Novoa, M. A Low-Cost Validated Two-Camera 3D Videogrammetry System Applicable to Kinematic Analysis of Human Motion. Sensors 2025, 25, 4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuzevičius, D.; Serackis, A. Three-Dimensional Human Head Reconstruction Using Smartphone-Based Close-Range Video Photogrammetry. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Enriquez, O.C.; Valero-Lanzuela, J.J.; Lerma, J.L. Craniofacial 3D Morphometric Analysis with Smartphone-Based Photogrammetry. Sensors 2024, 24, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira Coelho, L.C.; Pinho, M.F.C.; Martinez de Carvalho, F.; Meneguci Moreira Franco, A.L.; Quispe-Enriquez, O.C.; Altónaga, F.A.; Lerma, J.L. Evaluating the Accuracy of Smartphone-Based Photogrammetry and Videogrammetry in Facial Asymmetry Measurement. Symmetry 2025, 17, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčiš, M.; Fraštia, M.; Hideghéty, A.; Paulík, P. Videogrammetric Verification of Accuracy of Wearable Sensors Used in Kiteboarding. Sensors 2021, 21, 8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. Accuracy Evaluation of Videogrammetry Using a Low-Cost Spherical Camera for Narrow Architectural Heritage: An Observational Study with Variable Baselines and Blur Filters. Sensors 2019, 19, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Coder, P.; Sánchez-Ríos, A. An Integrated Solution for 3D Heritage Modeling Based on Videogrammetry and V-SLAM Technology. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Alfio, V.S.; Costantino, D.; Herban, S. Rapid and Accurate Production of 3D Point Cloud via Latest-Generation Sensors in the Field of Cultural Heritage: A Comparison between SLAM and Spherical Videogrammetry. Heritage 2022, 5, 1910–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, B.; Khalaf, Y.H. Potential Use of Drone Ultra-High-Definition Videos for Detailed 3D City Modeling. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currà, E.; D’Amico, A.; Angelosanti, M. HBIM between Antiquity and Industrial Archaeology: Former Segrè Papermill and Sanctuary of Hercules in Tivoli. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PostgreSQL Global Development Group. PostgreSQL; Relational database management system; PostgreSQL Global Development Group, 2025.

- Django Software Foundation. Django Web Framework; Web application framework for Python; Django Software Foundation: Huntersville, NC, USA, 2025.

- Schütz, M. Potree: Rendering Large Point Clouds in Web Browsers. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- Isenburg, M. LASzip: Lossless LiDAR Compression; LiDAR compression software; rapidlasso GmbH, 2025.

- PDAL Contributors. PDAL: Point Data Abstraction Library; Point cloud processing library; PDAL Project, 2025.

- NGINX, Inc. NGINX Web Server; HTTP and reverse proxy server; NGINX, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025.

- Smithsonian Institution Digitization Program Office. Smithsonian Voyager / DPO-Voyager Tools; 3D visualization and annotation toolkit; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Khronos Group. glTF: GL Transmission Format; 3D scene and model transmission format; The Khronos Group, Inc.: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2025.

- Trimesh Developers. Trimesh: Python library for loading and processing 3D geometry; Geometry processing library for Python; 2025.

- McCurdy, D. glTF-Transform: Toolkit for glTF Optimization; 2025.

- Google LLC. Draco Compression Library; 3D geometry compression library; Google LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2025.

- Docker, Inc. Docker; Containerization platform; Docker, Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2025.

- Node.js Foundation. Node.js JavaScript Runtime; JavaScript runtime environment; Node.js Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025.

| Elios 3 | |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Flyability |

| Weight (g) | Approx. 1,900 g includes battery, payload & protection |

| Max. payload (g) | 2,350 g |

| Power source | 4350 mAh LiPo |

| Endurance (min) | 9-12 min |

| Camera | 2.71 mm focal length. Fixed focal |

| Thermal Camera | Sensor Lepton 3.5 FLIR |

| LiDAR Sensors | Ouster OS0-32 beams sensor1 |

| Flight control sensors | IMU, magnetometer, barometer, LiDAR, 3 computer vision cameras and ToF distance sensor |

| Video Records | POI (nº) | FPS | Total Images | Mean Reprojection Error1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight 1 | 5 min 20 s | 12 | 3 fps | 796 (3840x2160 px) | 0.21 px (Pix4D) |

| Flight 2 | 6 min 21 s | 7 | 3 fps | 807 (3840x2160 px) | 1.32 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 3 | 6 min 49 s | 5 | 3 fps | 738 (3840x2160 px) | 2.8 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 4 | 8 min | 5 | 3 fps | 921 (3840x2160 px) | 0.21 px (Pix4D) |

| Flight 5 | 6 min 43 s | 8 | 3 fps | 920 (3840x2160 px) | 1.23 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 6 | 5 min 15 s | 11 | 3 fps | 726 (3840x2160 px) | 1.46 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 7 | 6 min 22 s | 13 | 2 fps | 765 (3840x2160 px) | 1.34 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 8 | 7 min 8 s | 12 | 2 fps | 858 (3840x2160 px) | 1.51 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 9 | 7 min 21 s | 11 | 2 fps | 885 (3840x2160 px) | 0.21 px (Pix4D) |

| Flight 10 | 6 min 35 s | 3 | 2 fps | 649 (3840x2160 px) | 0.21 px (Pix4D) |

| Flight 11 | 7 min 35 s | 3 | 2 fps | 807 (3840x2160 px) | 1.49 px (Metashape) |

| Flight 12 | 7 min 6 s | 6 | 2 fps | 763 (3840x2160 px) | 0.22 px (Pix4D) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).