Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Catalysts Morphology and Structure

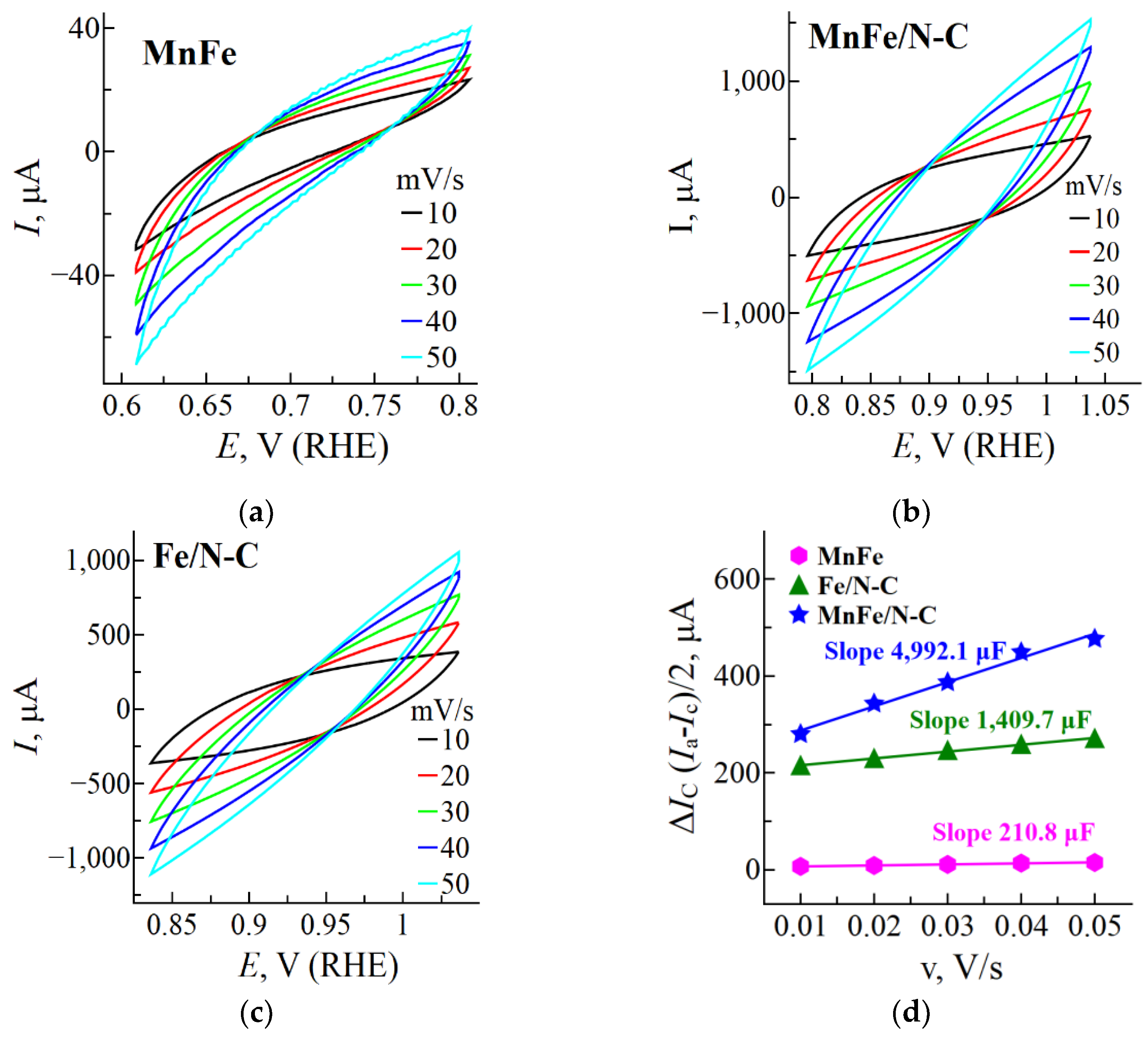

2.2. Determination of the Electrochemically Active Surface Areas (ECSAs)

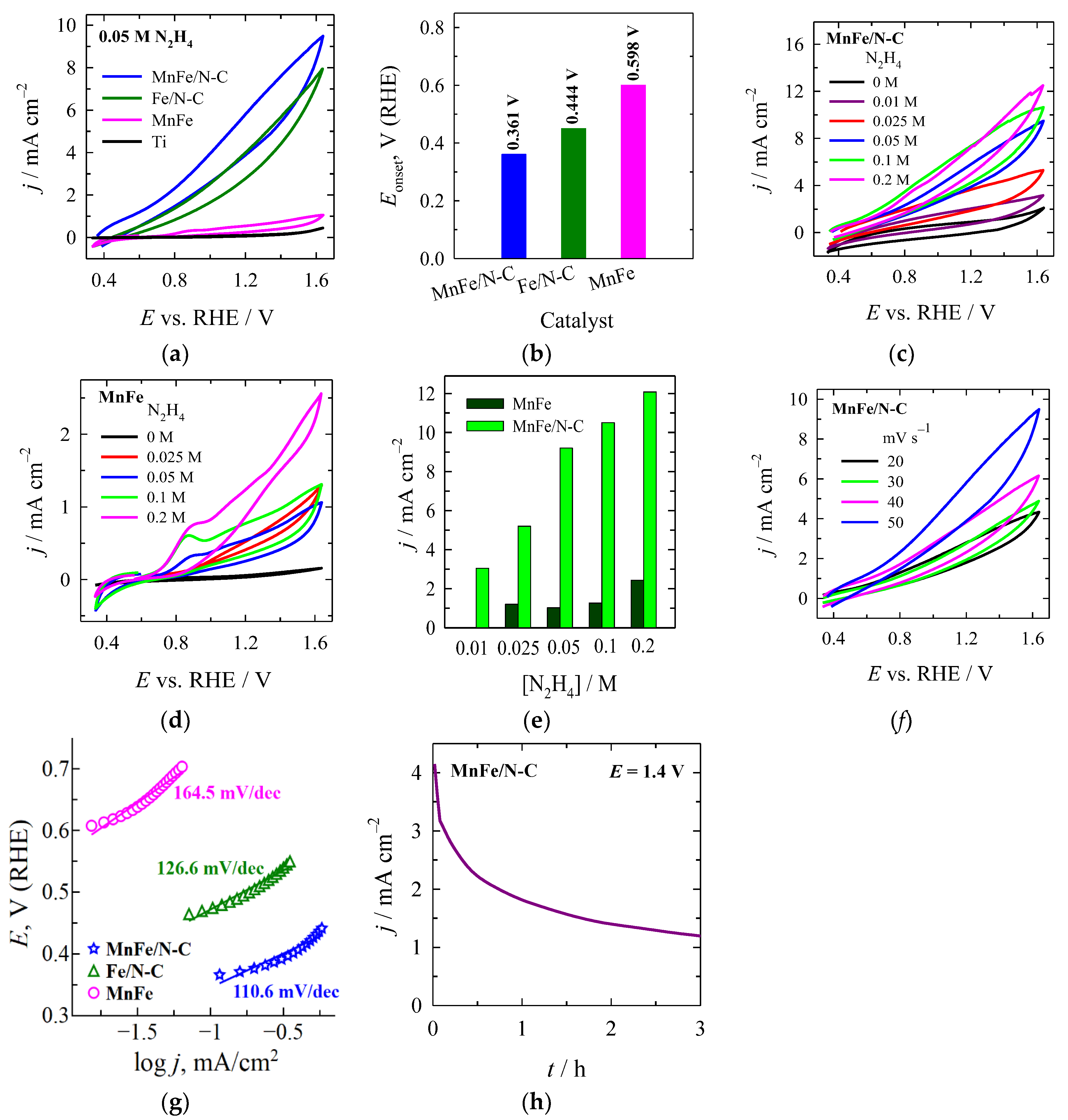

2.3. The Oxidation of Hydrazine

3. Materials and Methods

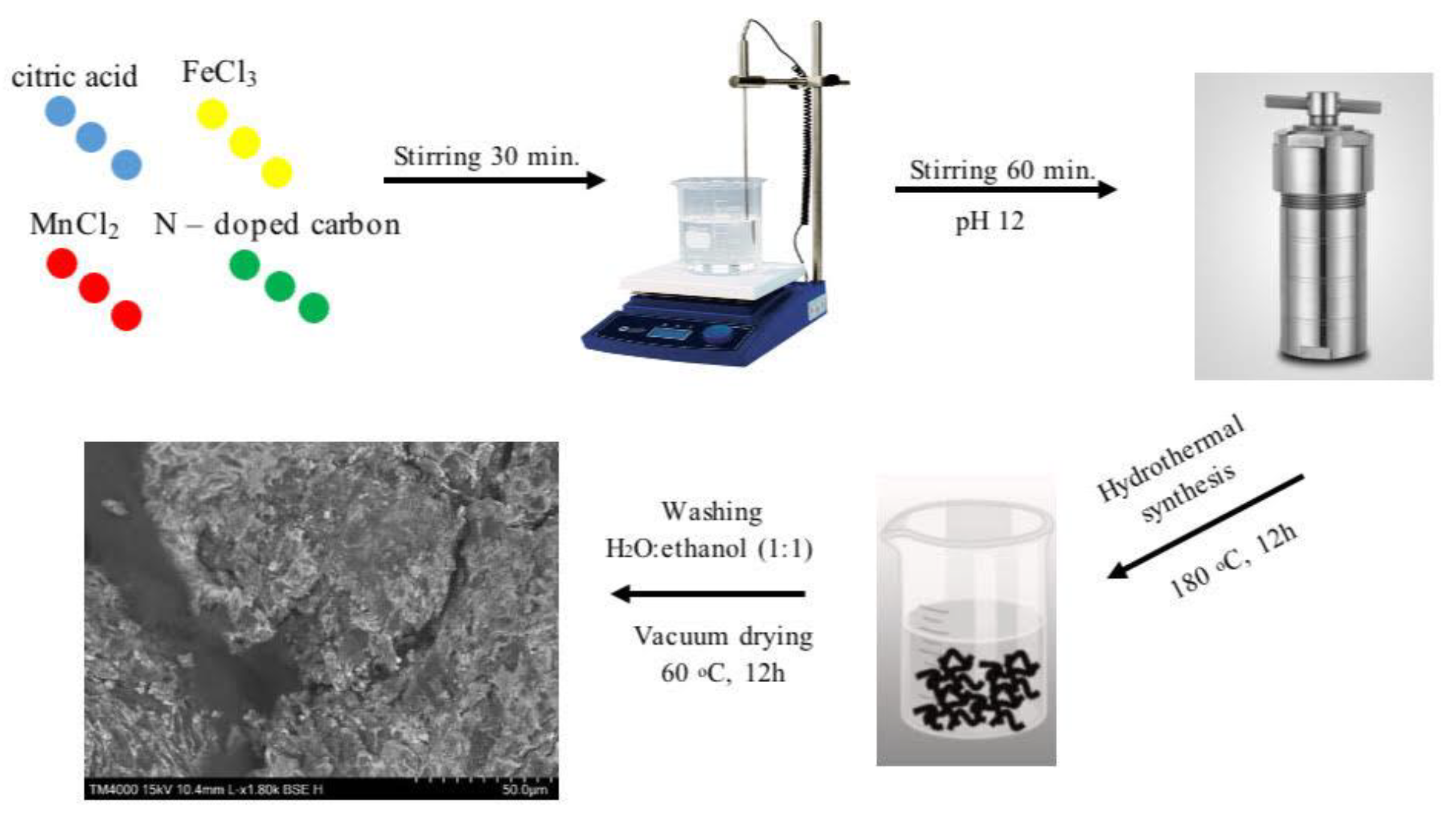

3.1. Synthesis of Metal Particles Supported Nitrogen-Doped Carbon (M/N-C)

3.2. Characterization of Catalysts

3.3. Investigation of Hydrazine Oxidation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamichaney, S.; K. Baranwal, R.; Maitra, S.; Majumdar, G. Clean Energy Technologies: Hydrogen Power and Fuel Cells, Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials, 2020, Volume 3, pp. 366–37120.

- Staffell, I.; Scamman, D.; Velazquez Abad, A.; Balcombe, P.; Dodds, P.E.; Ekins, P.; Shah, N.; Ward, K.R. The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Asazawa, K.; Sakamoto, T.; Kato, T.; Kai, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamada, K.; Fujikawa, H. Platinum-free anionic fuel cells for automotive applications. ECS Trans. 2008, 16, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloveichik, G.L. Liquid fuel cells. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1399–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorms, E.A.; Oshchepkov, A.G.; Bonnefont, A.; Savinova, E.R.; Chatenet, M. Carbon-free fuels for direct liquid-feed fuel cells: Anodic electrocatalysts and influence of the experimental conditions on the reaction kinetics and mechanisms. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy 2024, 345, 123676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y.; Yan, Y.; Xue, Q.; He, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Xia, B.Y. Anodic hydrazine oxidation assists energy efficient hydrogen evolution over a bifunctional cobalt perselenide nanosheet electrode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7649–7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Luo, J. Transition-metal-based electrocatalysts for hydrazine-assisted hydrogen production. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, Q.; Qu, K. Highly enhanced bifunctionality by trace Co doping into Ru matrix towards hydrazine oxidation-assisted energy-saving hydrogen production. Fuel 2024, 360, 130602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Li, R.; Yao, Q.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, K. Highly enhanced hydrazine oxidation on bifunctional Ni tailored by alloying for energy-efficient hydrogen production. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2023, 652, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Su, L.; Yu, X.; Sun, J.; Miao, X. Spin configuration modulation of Co3O4 by Ru-doping for boosting overall water splitting and hydrazine oxidation reaction. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Sun, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, T.; Ma, M.; Fan, Z.; Yang, H.; Liao, F.; Shao, M.; Kang, Z. Nitrogen contained rhodium nanosheet catalysts for efficient hydrazine oxidation reaction. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2024, 343, 123561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Ye, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, B.; Zhou, J.; Liao, H.; Wu, X.; Ding, R.; Liu, E.; Gao, P. Building P-poor Ni2P and P-rich CoP3 heterojunction structure with cation vacancy for enhanced electrocatalytic hydrazine and urea oxidation. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2024, 40, 2306054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; Choi, M.Y.; Choi, H.C. Graphene-oxide-supported Pt nanoparticles with high activity and stability for hydrazine electro-oxidation in a strong acidic solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 420, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Yang, W.; Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Jia, J. High performance of electrocatalytic oxidation and determination of hydrazine based on Pt nanoparticles/TiO2 nanosheets. Talanta 2015, 144, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstopjatova, E.G.; Kondratiev, V.V.; Eliseeva, S.N. Multi-layer PEDOT: PSS/Pd composite electrodes for hydrazine oxidation. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2015, 19, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, S.; Aslışen, B. Hydrazine oxidation at gold nanoparticles and poly (bromocresol purple) carbon nanotube modified glassy carbon electrode. Sensor Actuator B Chem. 2014, 196, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojani, R.; Alinezhad, A.; Aghajani, M.J.; Safshekan, S. Silver nanoparticles/poly ortho-toluidine/modified carbon paste electrode as a stable anode for hydrazine oxidation in the alkaline media. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2015, 19, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-X.; Jiang, L.-Y.; Wang, A.-J.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Feng, J.-J. Simple synthesis of bimetallic AuPd dendritic alloyed nanocrystals with enhanced electrocatalytic performance for hydrazine oxidation reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 190, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.C.; Silva, W.O.; Chatenet, M.; Lima, F.H.B. NiOx-Pt/C nanocomposites: Highly active electrocatalysts for the electrochemical oxidation of hydrazine. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2017, 201, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, Q.; Qu, K. Highly enhanced bifunctionality by trace Co doping into Ru matrix towards hydrazine oxidation-assisted energy-saving hydrogen production. Fuel 2024, 360, 130602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, Y.; Zengin, A.; Gülcan, M. Pd-doped flower like magnetic MnFe2O4 spinel ferrit nanoparticles: Synthesis, structural characterization and catalytic performance in the hydrazine-borane methanolysis. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 110, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Qian, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, G. Magic hybrid structure as multifunctional electrocatalyst surpassing benchmark Pt/C enables practical hydrazine fuel cell integrated with energy-saving H2 production. eScience 2022, 2, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, R.; Silva de Barros, V.V.; Rodrigues de Oliveira, F.E.; Rocha, T.A.; Zignani, S.; Spadaro, L.; Palella, A.; Dias, J.A.; Linares, J.J. On the promotional effect of Cu on Pt for hydrazine electrooxidation in alkaline medium. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 236, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslışen, B.; Koçak, S. Preparation of mixed-valent manganese-vanadium oxide and Au nanoparticle modified graphene oxide nanosheets electrodes for the simultaneous determination of hydrazine and nitrite. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 904, 115875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoğulları, S.; Çιnar, S.; Özdokur, K.V.; Aydemir, T.; Ertaş, F.N.; Koçak, S. Pulsed deposited manganese and vanadium oxide film modified with carbon nanotube and gold nanoparticle: Chitosan and ionic liquid-based biosensor. Electroanalysis 2019, 32, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asazawa, K.; Yamada, K.; Tanaka, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Oguro, K. Electrochemical oxidation of hydrazine and its derivatives on the surface of metal electrodes in alkaline media. J. Power Sources 2009, 191, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Cao, C.; Li, K.; Lyu, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Hu, P.; Wu, J.; Lau, W.-M.; Zhu, X.; Qian, P.; Zheng, J. Regulating electronic structure by Mn doping for nickel cobalt hydroxide nanosheets/carbon nanotube to promote oxygen evolution reaction and oxidation of urea and hydrazine. Chem. Engineer. J. 2023, 452, 139527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, X. Fe/P dual-doping NiMoO4 with hollow structure for efficient hydrazine oxidation-assisted hydrogen generation in alkaline seawater. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy 2024, 347, 123805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Yun, K. Synergistic sulfur-doped tri-metal phosphide electrocatalyst for efficient hydrazine oxidation in water electrolysis: Toward high-performance hydrogen fuel generation. J. Alloys Compn. 2024, 986, 174044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.B.; Salarizadeh, P.; Beitollahi, H.; Tajik, S.; Eshghi, A.; Azizi, S. Electro-oxidation of hydrazine on NiFe2O4-rGO as a high-performance nano-electrocatalyst in alkaline media. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 275, 125313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wen, H.; Wang, P. Bicontinuous nanoporous Ni-Fe alloy as a highly active catalyst for hydrazine electrooxidation. J. Alloys Compn. 2022, 906, 164370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Kannan, P.; Wang, P.; Ji, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Gai, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, R. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped MnO/carbon network as an advanced catalyst for direct hydrazine fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 413, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Park, J.; Bong, S.; Park, J.-S.; Jeong, B.; Lee, J. Pore surface engineering of FeNC for outstanding power density of alkaline hydrazine fuel cells. Chem. Engineer. J. 2024, 479, 147522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Cai, Z.; Zou, J. PBA-derived FeCo alloy with core-shell structure embedded in 2D N-doped ultrathin carbon sheets as a bifunctional catalyst for rechargeable Zn-air batteries. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 316, 121687–121698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, T.; Liang, E.; Li, B. Out-of-plane CoRu nanoalloy axially coupling CosNC for electron enrichment to boost hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 318, 121890–121898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.L.; Liu, W.J.; Hu, X.; Lam, P.K.S.; Zeng, J.R.; Yu, H.Q. Ionothermal carbonization of biomass to construct sp2/sp3 carbon interface in N-doped biochar as efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 400, 125969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Asefa, T. Heteroatom-doped carbon materials for hydrazine oxidation. Adv Mater. 2019, 31, 1804394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Zou, X.; Huang, X.; Goswami, A.; Liu, Z.; Asefa, T. Polypyrrole-derived nitrogen and oxygen Co-doped mesoporous carbons as efficient metal-free electrocatalyst for hydrazine oxidation. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6510–6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, K.; Meng, Y.; Huang, X.; Zou, X.; Chhowalla, M.; Asefa, T. N and O-doped mesoporous carbons derived from rice grains: efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for hydrazine oxidation. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 13588–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthil, C.; Lee, C.W. Biomass-derived biochar materials as sustainable energy sources for electrochemical energy storage devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z. The rational design of biomass-derived carbon materials towards next-generation energy storage: A review, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, X. Wood for application in electrochemical energy storage devices. Cell Reports Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Kong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Lucia, L.A.; Fatehi, P.; Pang, H. Fabrication, characteristics and applications of carbon materials with different morphologies and porous structures produced from wood liquefaction: A review. Chem. Engineer. J. 2019, 364, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragal, E.H.; Fragal, V.H.; Huang, X.; Martins, A.C.; Cellet, T.S.P.; Pereira, G.M.; Mikmeková, E.; Rubira, A.F.; Silva, R.; Asefa, T. From ionic liquid-modified cellulose nanowhiskers to highly active metal-free nanostructured carbon catalysts for the hydrazine oxidation reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Huang, X.; Goswami, A.; Koh, K.; Meng, Y.; Almeida, V.C.; Asefa, T. Fibrous porous carbon electrocatalysts for hydrazine oxidation by using cellulose filter paper as precursor and self-template. Carbon 2016, 102, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upskuviene, D.; Balciunaite, A.; Drabavicius, A.; Jasulaitiene, V.; Niaura, G.; Talaikis, M.; Plavniece, A.; Dobele, G.; Volperts, A.; Zhurinsh, A.; Lin, Y.-W.; Tamasauskaite-Tamasiunaite, L.; Norkus, E. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped carbon catalyst from hydrothermally carbonized wood chips for oxygen reduction. Catal. Commun. 2023, 184, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Yu, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, S. Optimization strategies of preparation of biomass-derived carbon electrocatalyst for boosting oxygen reduction reaction: A minireview. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilari, S.; Pradhan, D. MnFe2O4@nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide nanohybrid: an efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for anodic hydrazine oxidation and cathodic oxygen reduction. Cat. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 5920–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hou, Y.; Jiang, L.; Feng, G.; Ge, Y.; Huang, Z. Progress in hydrazine oxidation-assisted hydrogen production. Energy Rev. 2025, 4, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; El-Harairy, A.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, G.; Xie, Y. Artificial heterointerfaces achieve delicate reaction kinetics towards hydrogen evolution and hydrazine oxidation catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. 2021, 60, 5984–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burshtein, T. Y.; Yasman, Y.; Muñoz-Moene, L.; Zagal, J. H. Eisenberg, D. Hydrazine oxidation electrocatalysis. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 2264–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, D.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Cai, Q.; Zhao, J. Single, Transition Metal Atoms Anchored on C2N Monolayer as Efficient Catalysts for Hydrazine Electrooxidation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 16691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; He, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Hu, G.; Ma, D.; Guo, J.; Fan, H.; Li, W.; Hu, X. Mimicking hydrazine dehydrogenase for efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of N2H4 by Fe−NC. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 38183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lei, L.; Kannan, P.; Subramanian, P.; Ji, S. Grain boundaries derived from layered Fe/Co di-hydroxide porous prickly-like nanosheets as potential electrocatalyst for efficient electrooxidation of hydrazine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 639, 158265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, P.; Wen, H.; Wang, P. Bicontinuous nanoporous Ni-Fe alloy as a highly active catalyst for hydrazine electrooxidation. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 906, 164370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, K.; Farber, E.M.; Burshtein, T.Y.; Eisenberg, D. A multi-doped electrocatalyst for efficient hydrazine oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 17168–17172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Ji, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. Simplifying the creation of iron compound inserted, nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes and its catalytic application. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 857, 157543–157553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Da, Y.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, D.; Zhan, S.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H. Atomically dispersed semimetallic selenium on porous carbon membrane as an electrode for hydrazine fuel cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 13466–13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.C.; Huang, X.; Goswami, A.; Koh, K.; Meng, Y.; Almeida, V.C.; Asefa, T. Fibrous porous carbon electrocatalysts for hydrazine oxidation by using cellulose filter paper as precursor and self-template. Carbon 2016, 102, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Xiao, F.; Cao, E.; Du, S.; Wu, Y.; Ren, Z. Self-assembly-induced mosslike Fe2O3 and FeP on electro-oxidized carbon paper for low-voltage-driven hydrogen production plus hydrazine degradation. ACS Sustain. Chem Eng. 2018, 6, 15727–15736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaj, S.; Ede, S.R.; Karthick, K.; Sam Sankar, S.; Sangeetha, K.; Karthik, P.E.; Kundu, S. Precision and correctness in the evaluation of electrocatalytic water splitting: Revisiting activity parameters with a critical assessment. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 744–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossar, E.; Houache, M.S.E.; Zhang, Z.; Baranova, E.A. Comparison of electrochemical active surface area methods for various nickel nanostructures. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 870, 114246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyitanga, T.; Kim, H. Time-dependent oxidation of graphite and cobalt oxide nanoparticles as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 914, 116297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Cdl, µF | ESA, cm2 | Rf |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnFe | 210.8 | 5.3 | 2.6 |

| Fe/N-C | 1,409.7 | 35.2 | 17.6 |

| MnFe/N-C | 4,992.1 | 124.8 | 62.4 |

| Sample | Electrolyte | Eonset, V vs. RHE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| MnO/N-C | 1 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.286 | [32] |

| N-C | 1 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.397 | [32] |

| Ni-Fe/NF | 1 M KOH + 0.5 M N2H4 | −0.110 | [31] |

| Fe–NC-2–1000 | 1 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.350 | [54] |

| Fe2MoC@NC | 1 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.280 | [57] |

| NiCoFe3O4 | 1.0 M KOH + 0.5 M N2H4 | +0.315 | [29] |

| NiFe3O4 | 1.0 M KOH + 0.5 M N2H4 | +0.595 | [29] |

| CoFe3O4 | 1.0 M KOH + 0.5 M N2H4 | +0.657 | [29] |

| Fe-MOF | 1.0 M KOH + 0.5 M N2H4 | +0.604 | [29] |

| Fe3C@NCNTs | 1.0 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.270 | [58] |

| SeNCM-1000 | 1.0 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.340 | [59] |

| Porous carbon-derived from filter paper (PCDFs-900) | 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) + 0.05 M N2H4 | +0.378 | [60] |

| Fe2O3/ECP-15 | 1.0 M KOH + 0.1 M N2H4 | +0.610 | [61] |

| Fe/N-C | 1.0 M KOH + 0.05 M N2H4 | +0.444 | This study |

| MnFe/N-C | 1.0 M KOH + 0.05 M N2H4 | +0.361 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).