Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

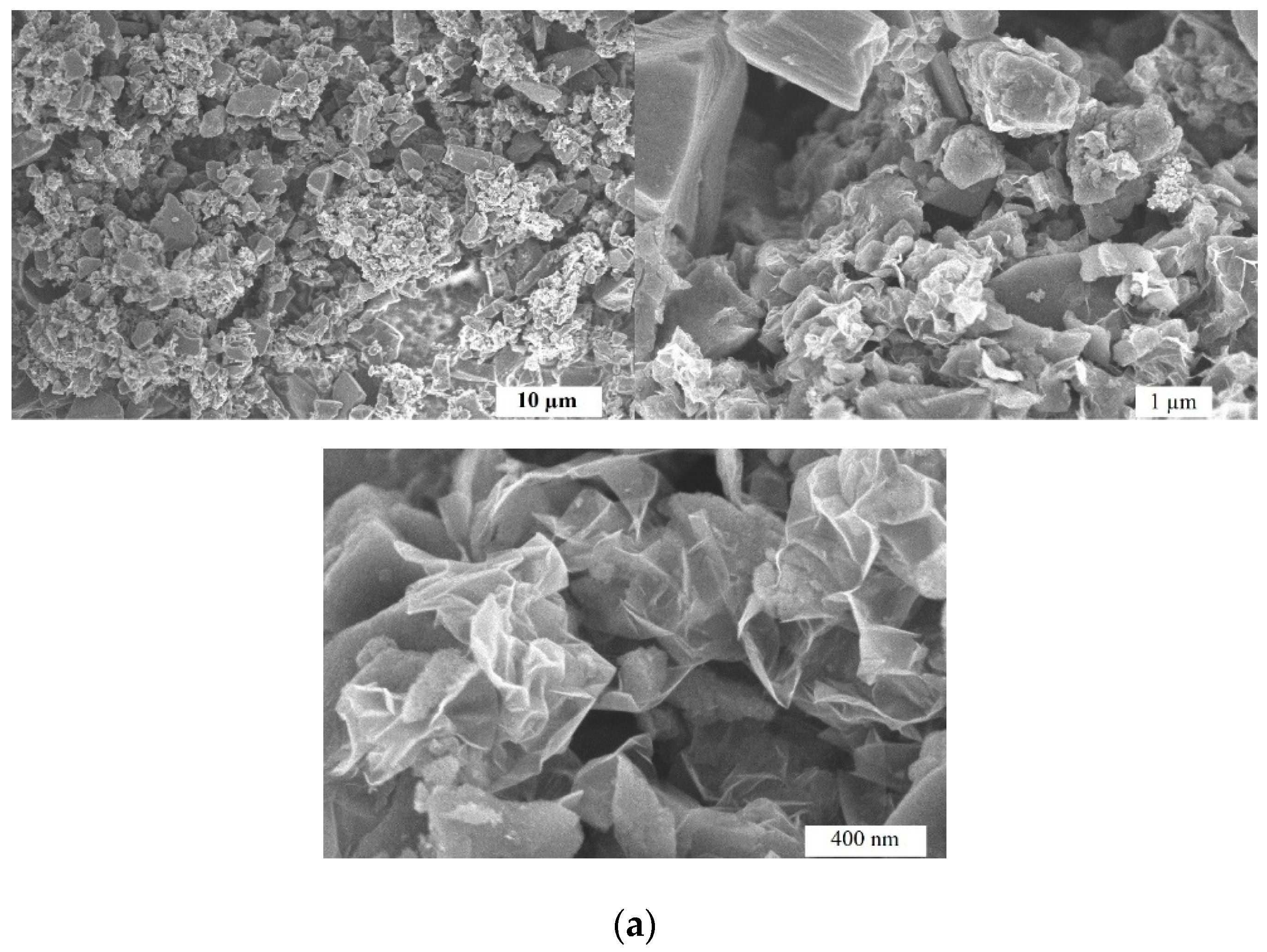

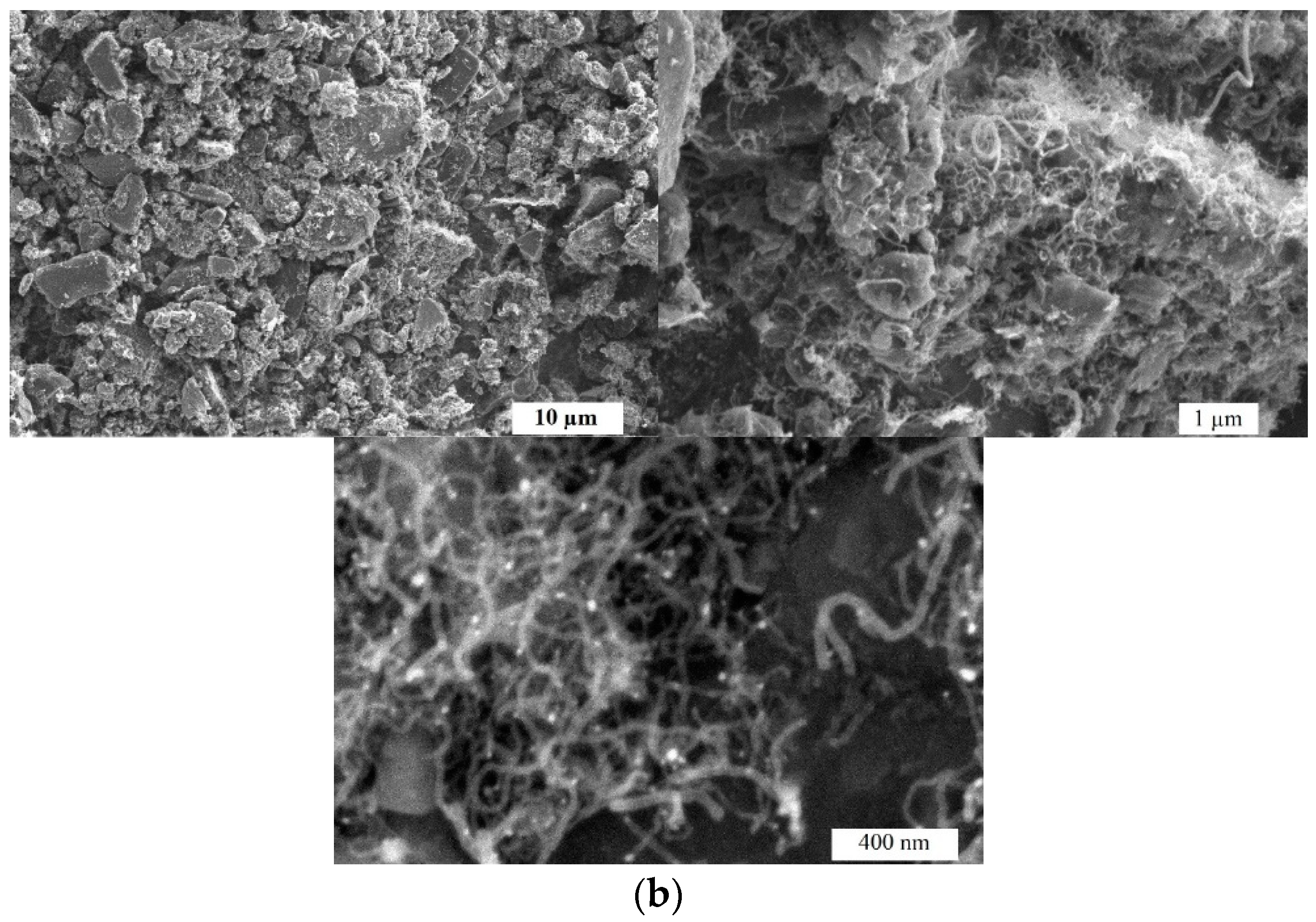

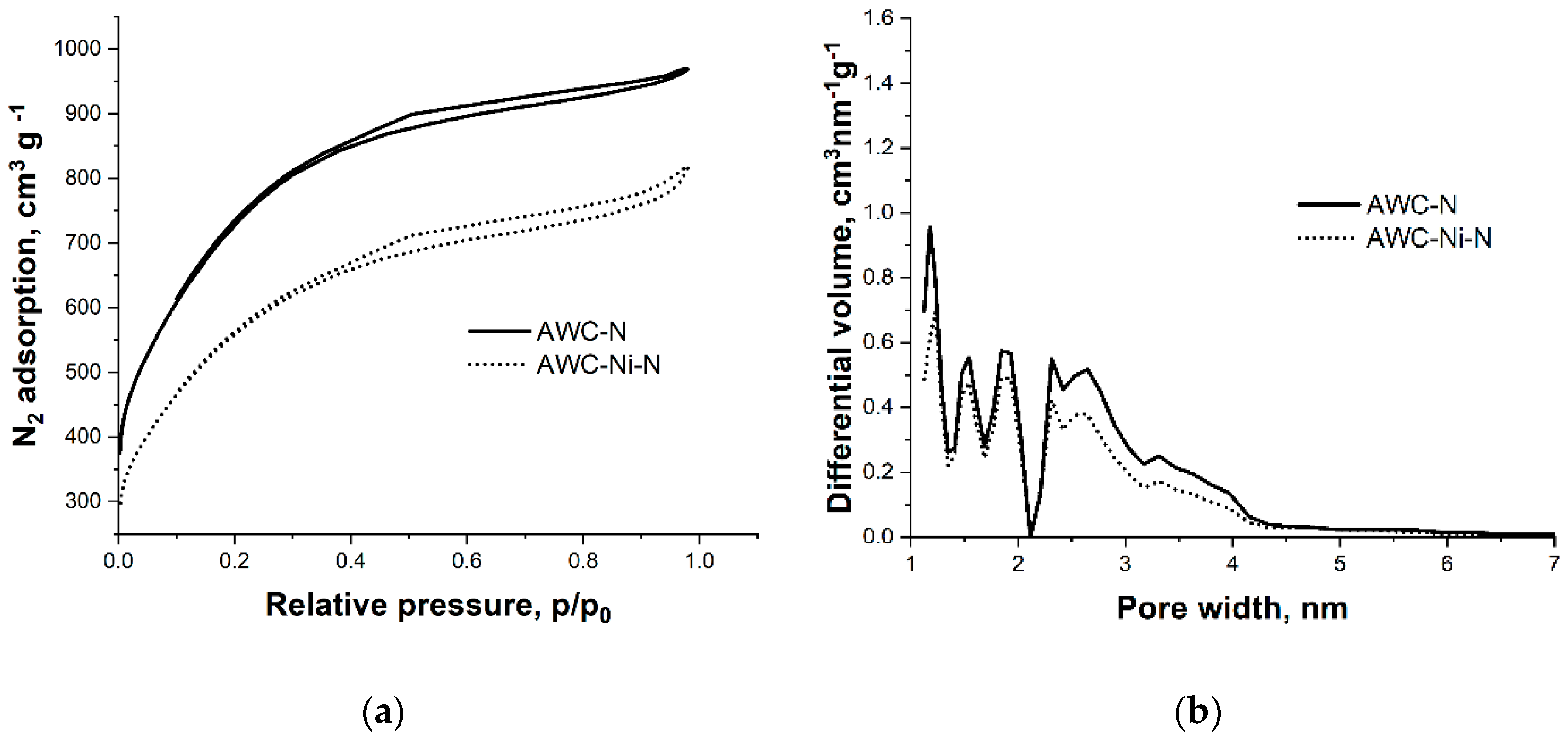

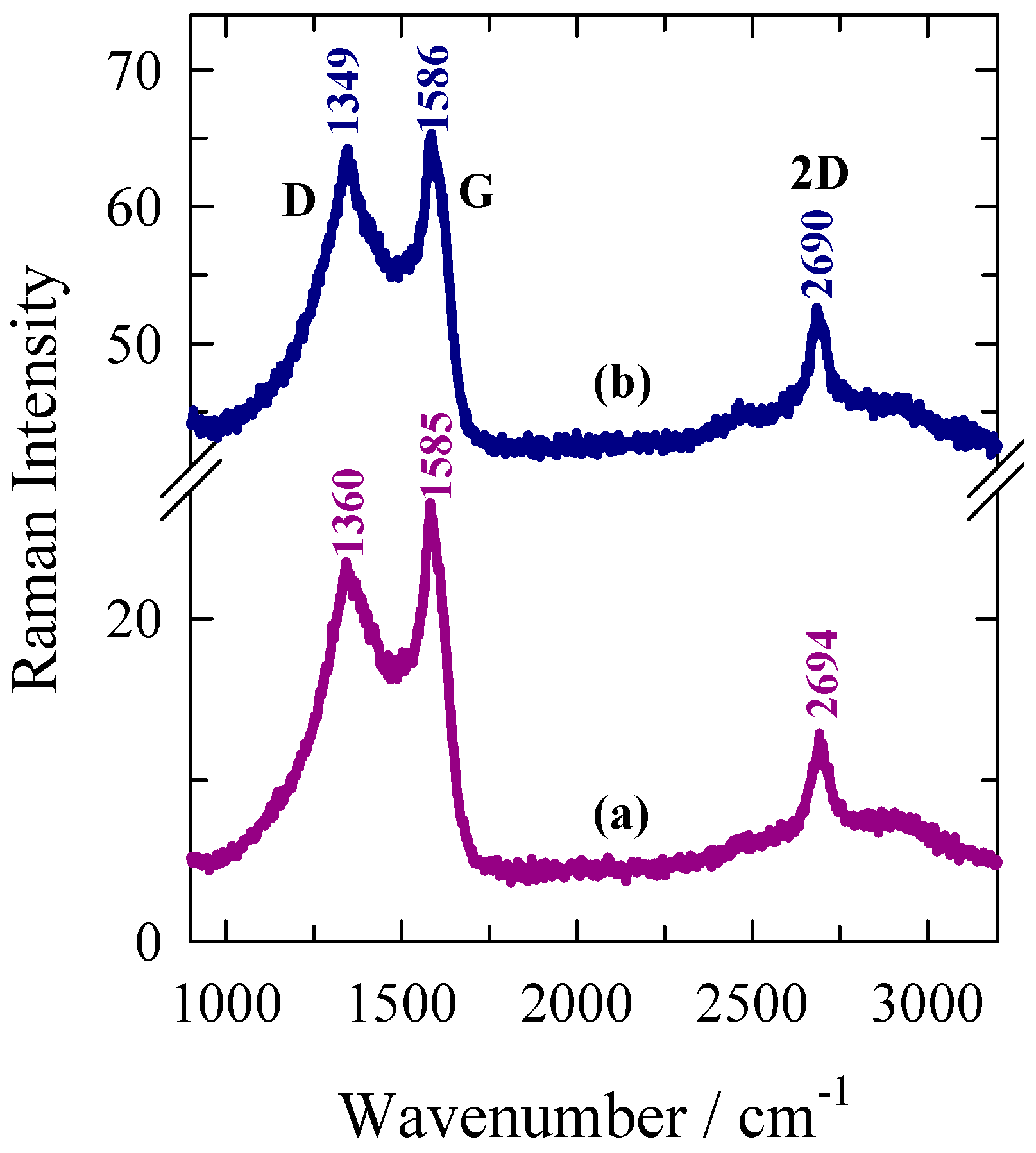

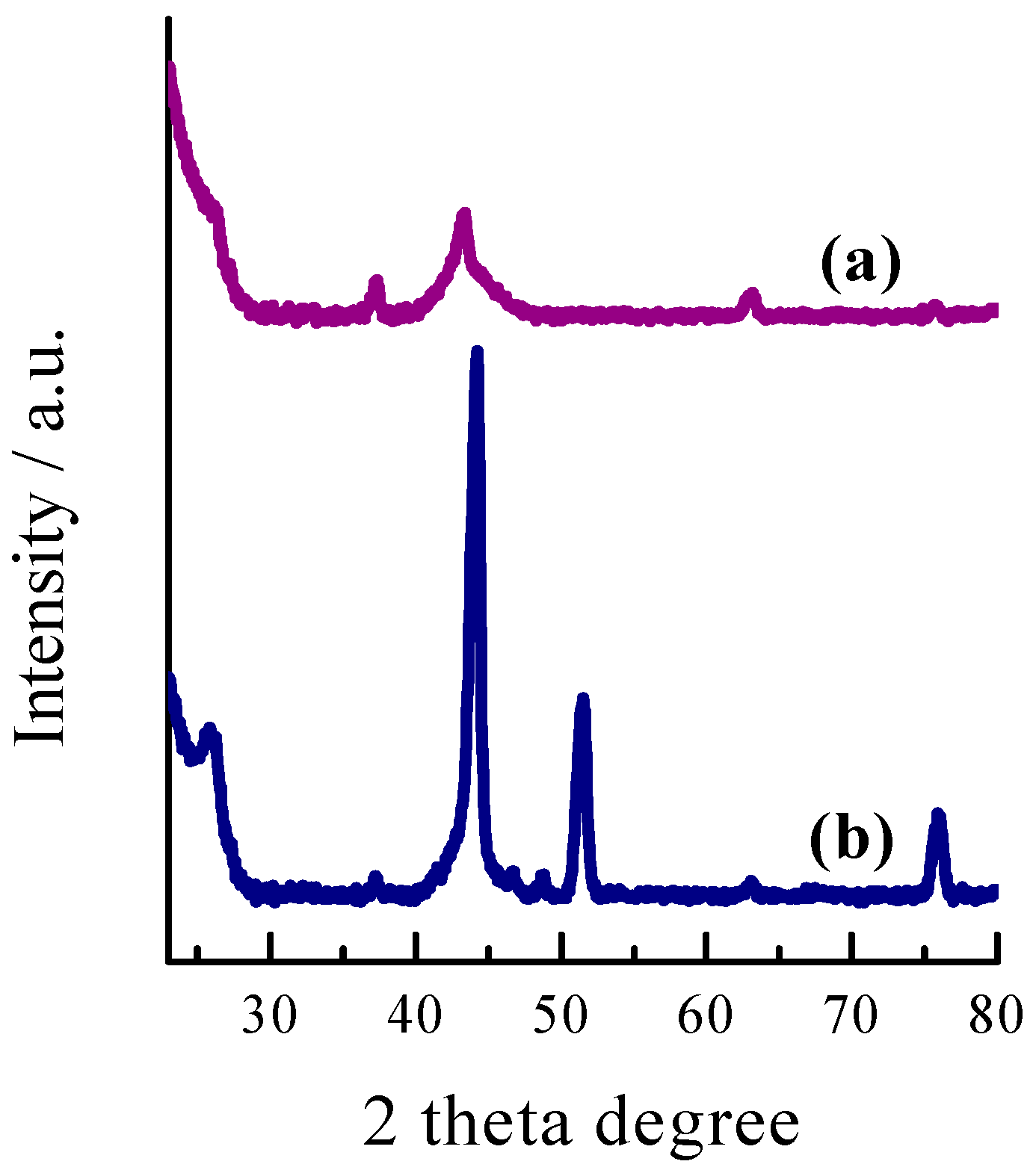

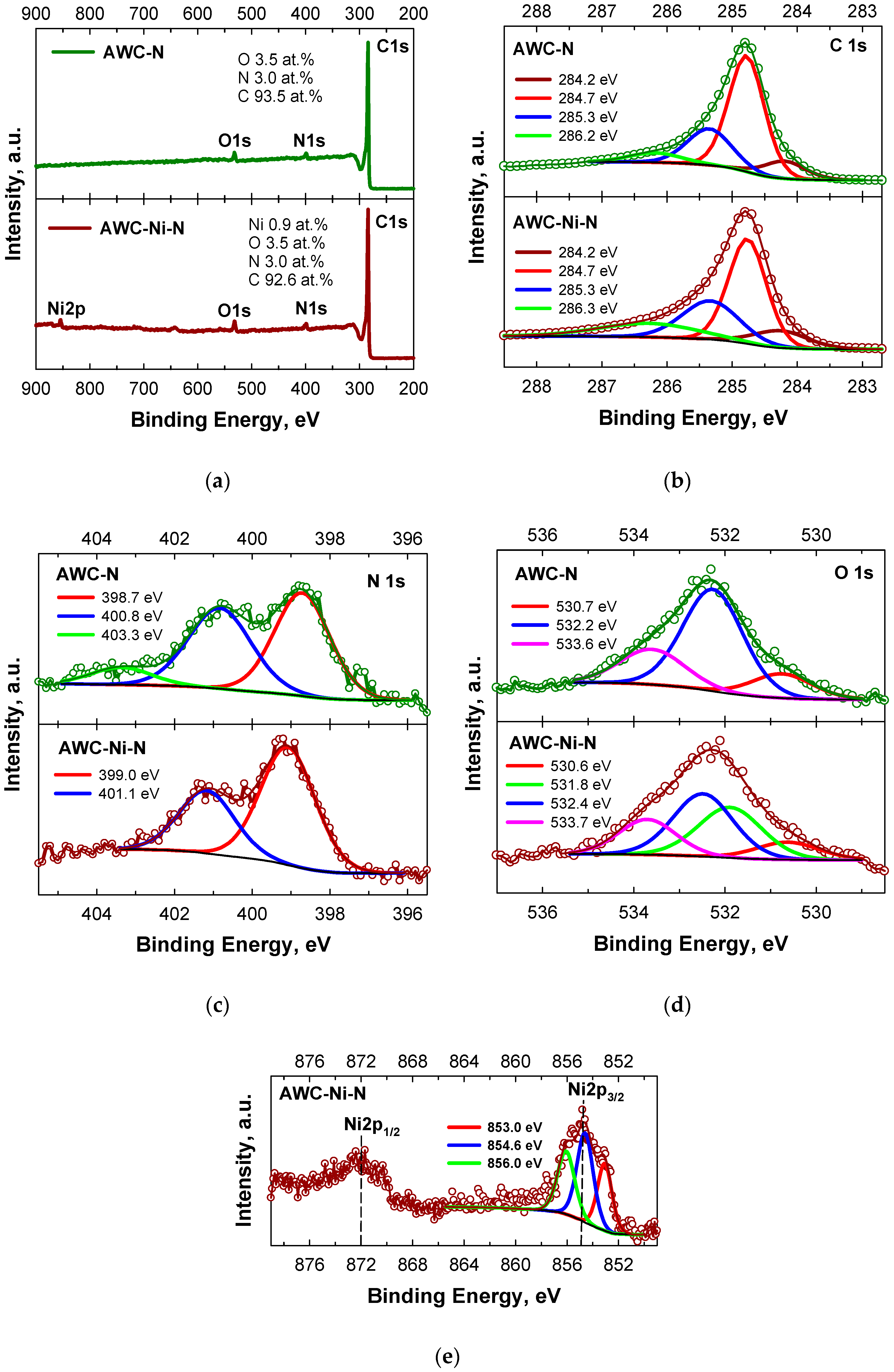

2.1. Microstructure and Morphology Studies

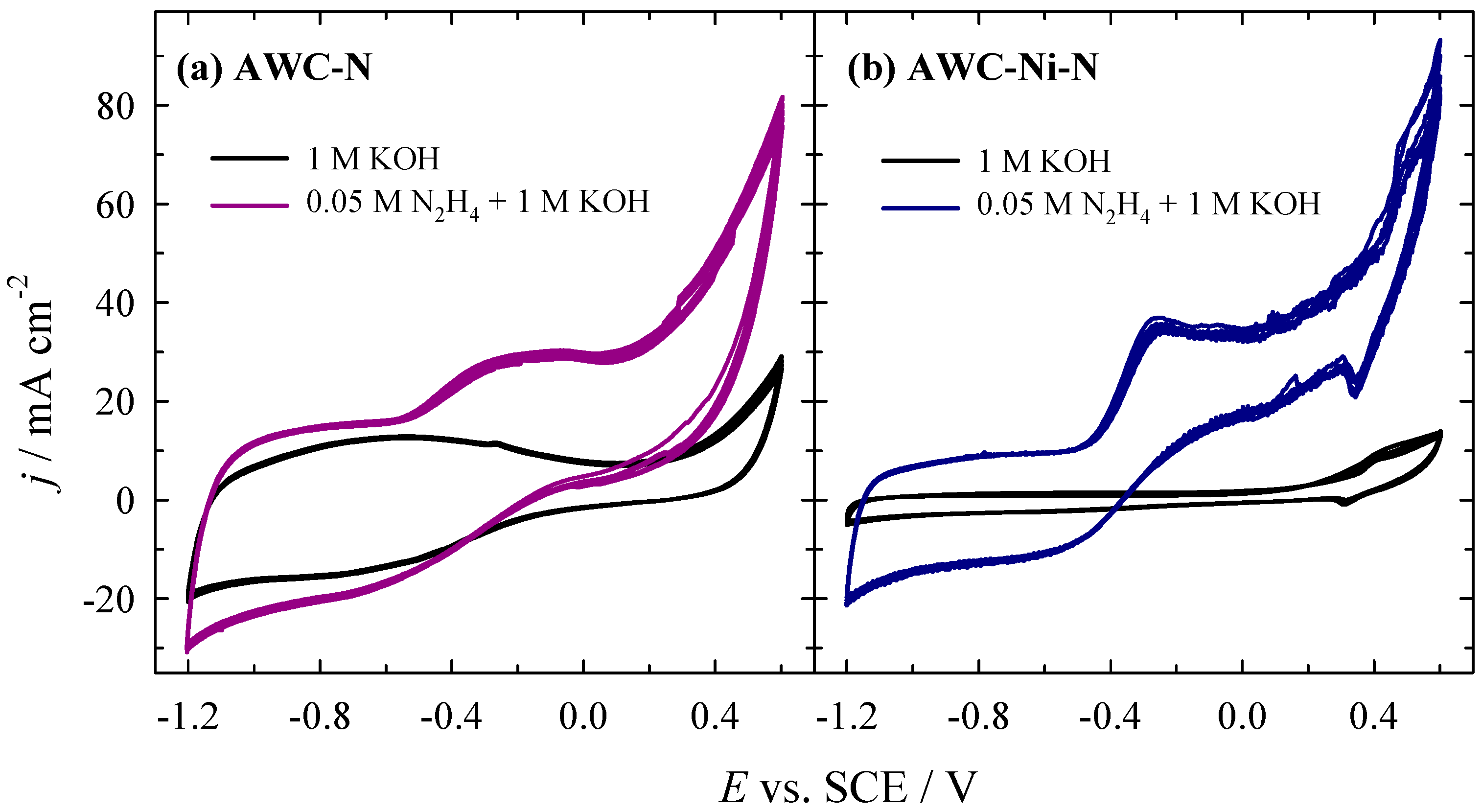

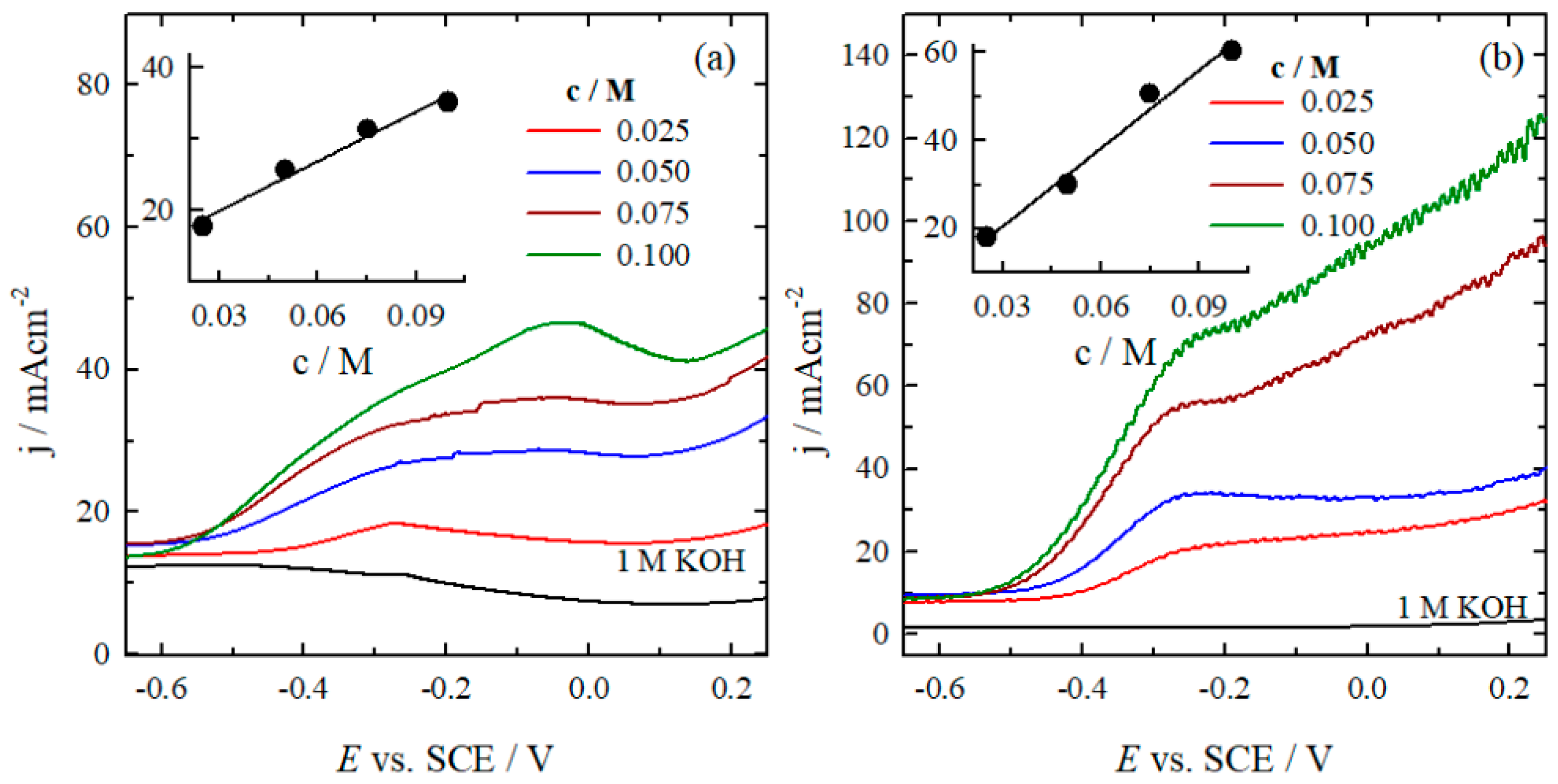

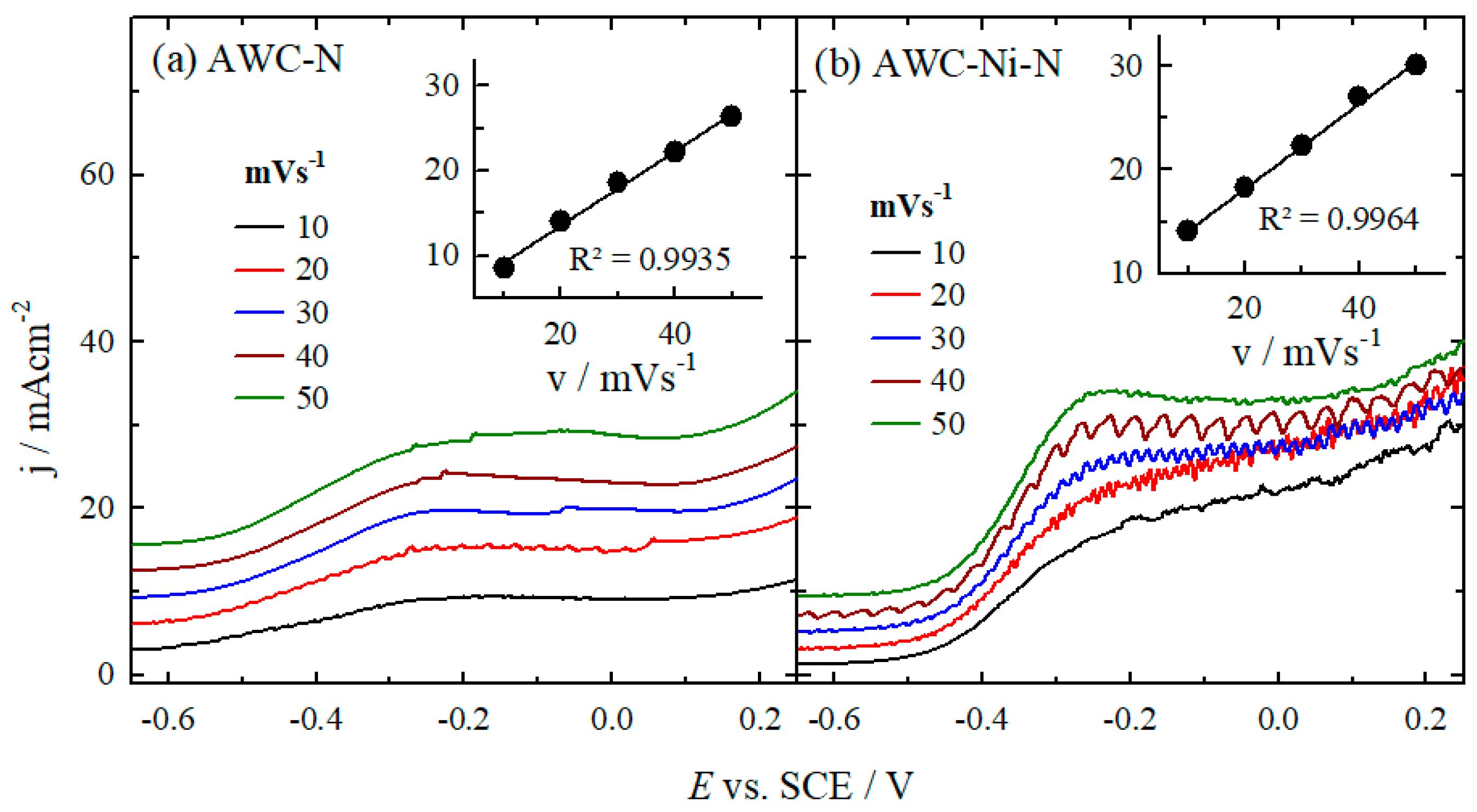

2.2. Determination of Electroactivity of Catalysts for HzOR

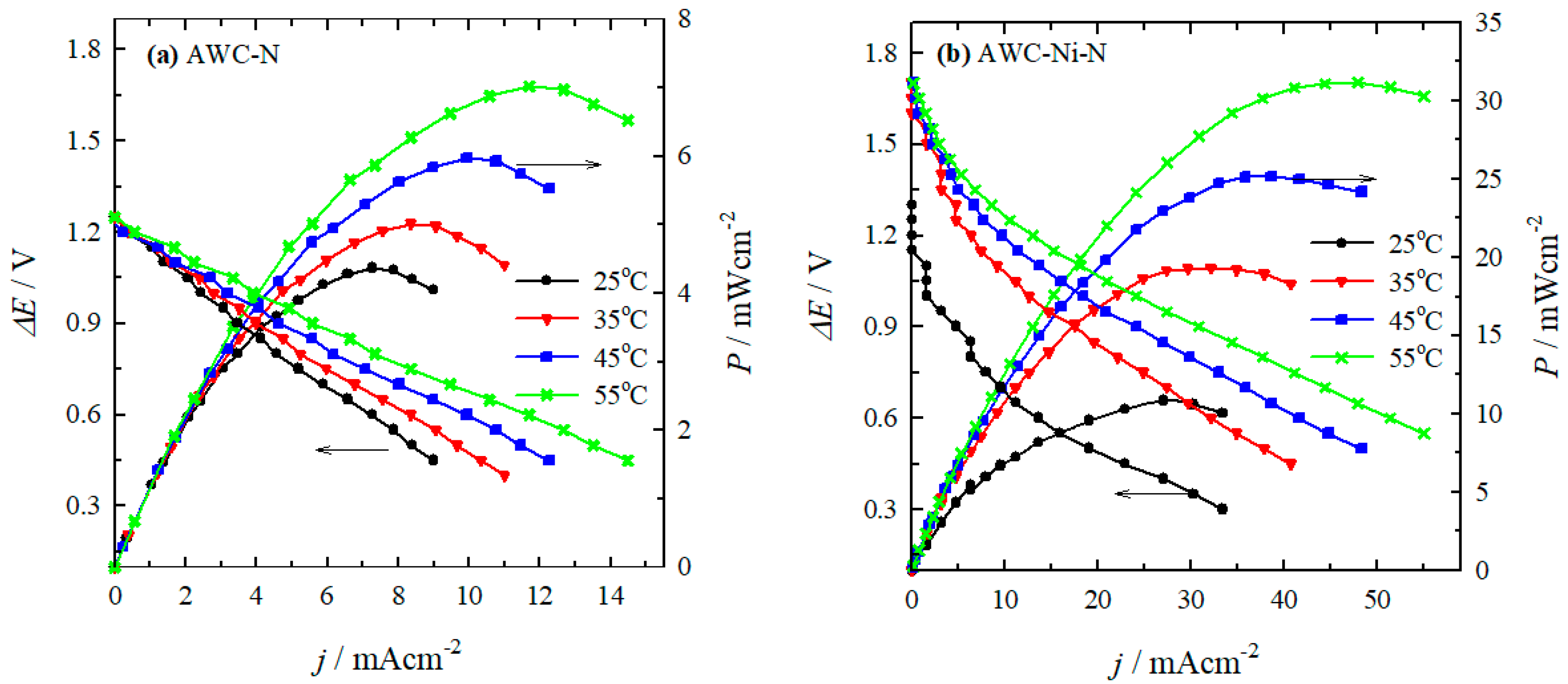

2.3. Performance of Direct N2H4-H2O2 Fuel Cell

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Nitrogen-Doped Activated Carbon Supported Nickel Particles

3.2. Characterization of Catalysts

3.3. Electrochemical Measurements

3.4. Fuel Cell Test Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, T.; Xie, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, X. Biomass-derived functional materials: Preparation, functionalization, and applications in adsorption and catalytic separation of carbon dioxide and other atmospheric pollutants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354(5), 129099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upskuvienė, D.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Drabavičius, A.; Jasulaitienė, V.; Niaura, G.; Talaikis, M.; Plavniece, A.; Dobele, G.; Volperts, A.; Zhurinsh, A. Lin, Y-Ch.; Chen, Y-W.; Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūnaitė, L.; Norkus, E. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped carbon catalyst from hydrothermally carbonized wood chips for oxygen reduction. Catal. Commun. 2023, 184, 106797. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, M. Single-atom catalysts toward electrochemical water treatment. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. Energy 2025, 363, 124783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Men, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, X.; Xiao, J.; Tang, Ch.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Versatile carbon-based materials from biomass for advanced electrochemical energy storage systems. eSci. 2024, 4(5), 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Li, N.; Lu, K.; Dong, Z.; Yang, Y. The emerging development of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots: Synthesis methods, influencing factors and applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 37, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, I.; Kibena-Põldsepp, E.; Mooste, M.; Kozlova, J.; Käärik, M.; Kikas, A.; Treshchalov, A.; Leis, J.; Kisand, V.; Tamm, A.; Holdcroft, S.; Tammeveski, K. Nitrogen and sulphur co-doped carbon-based composites as electrocatalysts for the anion-exchange membrane fuel cell cathode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volperts, A.; Upskuvienė, D.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Jasulaitienė, V.; Niaura, G.; Drabavičius, A.; Plavniece, A.; Dobele, G.; Zhurinsh, A.; Lin, Y-Ch.; Chen, Y-W.; Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūnaitė, L.; Norkus, E. Copper-nitrogen dual-doped activated carbon derived from alder wood as an electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction. Catal. Commun. 2023, 182, 106743. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.M.; Cellet, T.S.P.; Winkler, M.E.G.; Rubira, A.F.; Silva, R. Printing specific active sites for ORR and hydrazine oxidation on N-doped carbon. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 307, 128102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Niu, Y. Oxygen-doped MoS2 nanoflowers with sulfur vacancies as electrocatalyst for efficient hydrazine oxidation. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 906, 115986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghaddosi, S.; Rezaee, S.; Shahrokhian, S. Facile synthesis of N-doped hollow carbon nanospheres wrapped with transition metal oxides nanostructures as non-precious catalysts for the electro-oxidation of hydrazine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 873, 114437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Dai, H.; Li, S. Multifold nanotwin-enhanced catalytic activity of Ni-Zn-Cu for hydrazine oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 997, 174898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y,; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Zeng, S.; Li, R.; Yao, Q.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, K. Highly enhanced hydrazine oxidation on bifunctional Ni tailored by alloying for energy-efficient hydrogen production. J. Colloid Interf. Sci 2023, 652(B), 1848–1856. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, M.; Hu, T. Enhanced catalytic oxidation of hydrazine of CoO/Co3O4 heterojunction on N-doped carbon. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 458, 142537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filanovsky, B.; Granot, E.; Presman, I.; Kuras, I.; Patolsky, F. Long-term room-temperature hydrazine/air fuel cells based on low-cost nanotextured Cu–Ni catalysts. J. Power Sources 2014, 246, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Luo, J. Transition-metal-based electrocatalysts for hydrazine-assisted hydrogen production. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Tian, J. Fine-tuning catalytic performance of ultrafine bimetallic nickel-platinum on metal-organic framework derived nanoporous carbon/metal oxide toward hydrous hydrazine decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48(42), 16001–16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Su, J.; Wang, X.; Cai, P.; Cheng, G.; Luo, W. NiPt nanoparticles supported on CeO2 nanospheres for efficient catalytic hydrogen generation from alkaline solution of hydrazine. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2019, 30(3), 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shah, S.S.; Ahmad, A.; Yurtcan, A.B.; Jabeen, E.; Alshgari, R.A.; Janjua, N.K. Ruthenium and palladium oxide promoted zinc oxide nanoparticles: Efficient electrocatalysts for hydrazine oxidation reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 917, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanindriyoa, A.T.; Prawiraa, TB.M.Y.Y.; Agustaa, M.K.; Maezonob, R.; Dipojono, H.K. Computational design of Ni-Zn based catalyst for direct hydrazine fuel cell catalyst using density functional theory. Procedia Engineer. 2017, 170, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamašauskaitė-Tamašiūnaitė, L.; Šimkūnaitė, D.; Nacys, A.; Balčiūnaitė, A.; Zabielaitė, A.; Norkus, E. Chapter 11-Direct hydrazine fuel cells (DHFCs). Direct Liquid Fuel Cells Fundamentals, Advances and Future 2021, pp. 233–248. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Choudhury, N.A.; Sahai, Y. A comprehensive review of direct borohydride fuel cells. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, M.; Ahadzadeh, I.; Goudarziafshar, H. Direct hydrazine-hydrogen peroxide fuel cell using carbon supported Co@Au core-shell nanocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 15623–15361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedin, K.C.; Cazetta, A.L.; Souza, I.P.A.F.; Spessato, L.; Zhang, T.; Araújo, R.A.; Silva, R.; Asefa, T.; Almeida, V.C. N-doped spherical activated carbon from dye adsorption: Bifunctional electrocatalyst for hydrazine oxidation and oxygen reduction. J. Environ. Chem. Engineer. 2022, 10(3), 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serov, A.; Kwak, Ch. Direct hydrazine fuel cells: A review. App. Catal. B-Environ. 2010, 98, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorms, E.A.; Papaefthymiou, V.; Faverge, T.; Bonnefont, A.; Chatenet, M.; Savinova, E.R.; Oshchepkov, A.G. Mechanism of the hydrazine hydrate electrooxidation reaction on metallic Ni electrodes in alkaline media as revealed by electrochemical methods, online DEMS and ex situ XPS. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 507, 145056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Asazawa, K.; Martinez, U.; Halevi, B.; Suzuki, T.; Arai, S.; Matsumura, D.; Nishihata, Y.; Atanassov, P.; Tanaka, H. Electrooxidation of hydrazine hydrate using Ni–La catalyst for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 234, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.C.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Basri, S. Direct liquid fuel cells: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 10142–10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, D.R. Review of cell performance in anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2018, 375, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.G.; Rashidi, N.; Mahmoodi, R.; Omer, M. Preparation of Pt/G and PtNi/G nanocatalysts with high electrocatalytic activity for borohydride oxidation and investigation of different operation condition on the performance of direct borohydride-hydrogen peroxide fuel cell. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 208, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.C.P.; Vasić, M.; Santos, D.M.F.; Babić, B.; Hercigonja, R.; Sequeira, C.A.C.; Šljukić, B. Performance assessment of a direct borohydride-peroxide fuel cell with Pd-impregnated faujasite X zeolite as anode electrocatalyst. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 269, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayuri, P.; Huang, S.-T.; Mani, V.; Kumar, A.S. A new organic redox species-indole tetraone trapped MWCNT modified electrode prepared by in-situ electrochemical oxidation of indole for a bifunctional electrocatalysis and simultaneous flow injection electroanalysis of hydrazine and hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 268, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Fereira, E.H.M.; Stavale, F.; Achete, C.A.; Capaz, R.B.; Moutinho, M.V.O.; Lombardo, A.; Kulmala, T.S.; Ferrari, A.C. Quantifying defects in graphene via Raman spectroscopy at different excitation energies. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3190–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Soares, J.; Oliveros, M.E.; Garin, C.; David, M.V.; Martins, L.G.P.; Almeida, C.A.; Martins-Ferreira, E.H.; Takai, K.; Enoki, T.; Margalhães-Paniago, R.; Malachias, A.; Jorio, A.; Archanjo, B.S.; Achete, C.A.; Cançado, L.G. Structural analysis of polycrystalline graphene by Raman spectroscopy. Carbon 2015, 95, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorio, A.; Cançado, L.G. Perspectives on Raman spectroscopy of graphene-based systems: from the perfect two-dimensional surface to charcoal. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 15246–15256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorio, A.; Filho, A.G.S. Raman studies of carbon nanostructures. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusovas, R.; Ratautas, K.; Račiukaitis, G.; Niaura, G. Graphene layer formation in pinewood by nanosecond and picosecond laser. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 471, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C. Accessing the robustness of adventitious carbon for charge referencing (correction) purposes in XPS analysis: Insights from a multi-user facility data review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccile, N.; Laurent, G.; Babonneau, F.; Fayon, F.; Titirici, M.M.; Antonietti, M. Structural characterization of hydrothermal carbon spheres by advanced solid-state MAS 13C NMR investigations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 9644–9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Inyang, M.; Zhang, M.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Ro, K.S. Hydrogen peroxide modification enhances the ability of biochar (hydrochar) produced from hydrothermal carbonization of peanut hull to remove aqueous heavy metals: Batch and column tests. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 200–202, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.P.L.; Serov, A.; McCool, G.; Dicome, M.; Sousa, J.P.S.; Soares, O.S.G.P.; Bondarchuk, O.; Petrovykh, D.Y.; Lebedev, O.I.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Kolen’ko, Y.V. New opportunity for carbon-supported Ni-based electrocatalysts: gas-phase CO2 methanation. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 4770–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.; Smart, R.S.C. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy chemical state quantification of mixed nickel metal, oxide and hydroxide system. Surf. Interf. Anal. 2009, 41, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.St.C. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumkin, A.V.; Kraut-Vass, A.; Gaarenstroom, S.W.; Powel, C.J. NIST X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database (SRD 20),Version 5.0 (Web Version), 2023. http:/srdata.nist.gov/xps/.

| Sample | Specific surface area, m2 g–1 | Pore volume, cm3 g–1 | Average pore width, nm | Mesopores from Vt, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BET | DR | DFT | total | micro | meso | |||

| AWC-N | 2217 | 1921 | 1496 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 56.6 |

| AWC-Ni-N | 2050 | 1791 | 1387 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 49.7 |

| Sample | FWHM(G) (cm–1) | La (nm) | I(D'')/I(G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWC-N | 55.7 | 13.6 | 0.51 |

| AWC-Ni-N | 49.8 | 16.1 | 0.55 |

| Sample | C 1s | N 1s | O 1s | Ni 2p3/2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, eV | at. % | Eb, eV | at. % | Eb, eV | at. % | Eb, eV | at. % | |

| AWC-N | 284.2 | 10.49 | 398.7 | 48.38 | 530.7 | 14.89 | ||

| 284.7 | 59.27 | 400.8 | 42.72 | 532.2 | 61.86 | |||

| 285.3 | 23.13 | 403.3 | 8.90 | 533.5 | 23.25 | |||

| 286.2 | 7.11 | |||||||

| AWC-Ni-N | 284.2 | 11.02 | 399.0 | 64.79 | 530.6 | 10.91 | 853.0 | 27.71 |

| 284.7 | 46.92 | 401.1 | 35.21 | 531.8 | 31.82 | 854.6 | 41.55 | |

| 285.3 | 26.00 | 532.4 | 37.26 | 856.0 | 30.75 | |||

| 286.3 | 16.06 | 533.7 | 20.00 | |||||

| Catalyst | T (oC) | Peak power density (mW cm–2) |

j at peak power density (mA cm–2) | E at peak power density (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWC-N | 25 | 4.4 | 7.3 | 0.60 |

| 35 | 5.0 | 8.4 | 0.60 | |

| 45 | 6.0 | 9.9 | 0.60 | |

| 55 | 7.0 | 11.7 | 0.60 | |

| AWC-Ni-N | 25 | 10.8 | 27.0 | 0.40 |

| 35 | 19.3 | 32.2 | 0.60 | |

| 45 | 25.1 | 38.6 | 0.65 | |

| 55 | 31.1 | 47.9 | 0.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).