Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

2.2. Catalytic Evaluation

2.3. Catalyst Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

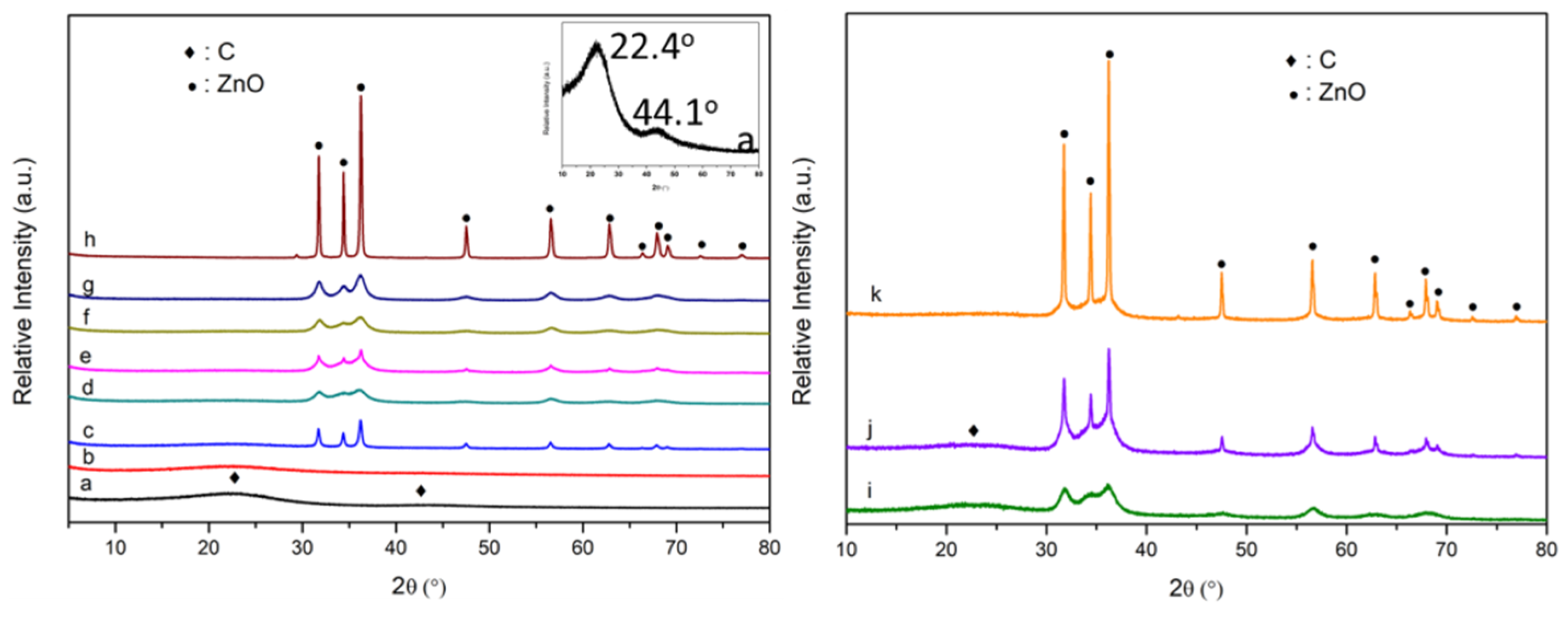

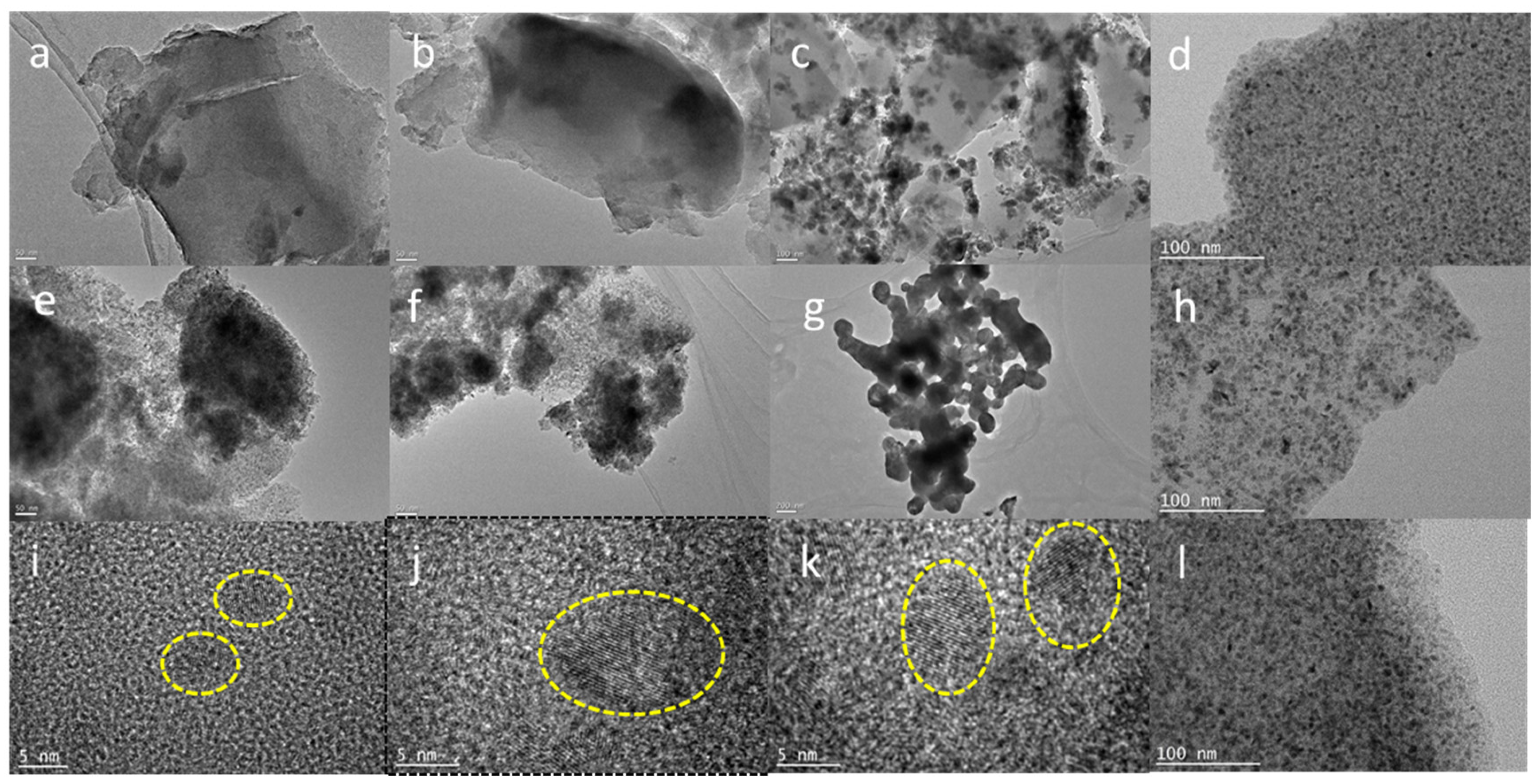

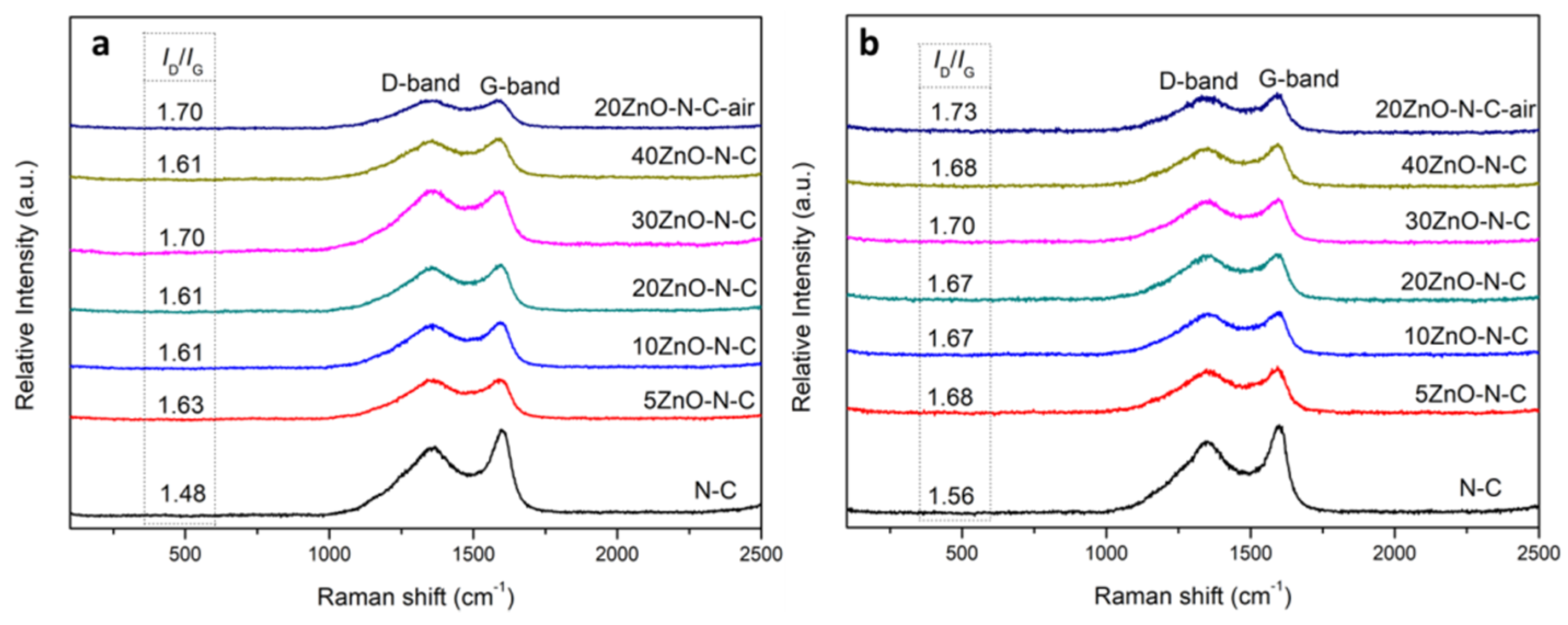

3.1. The Phase Structure and Nanoparticle Size of the Catalyst

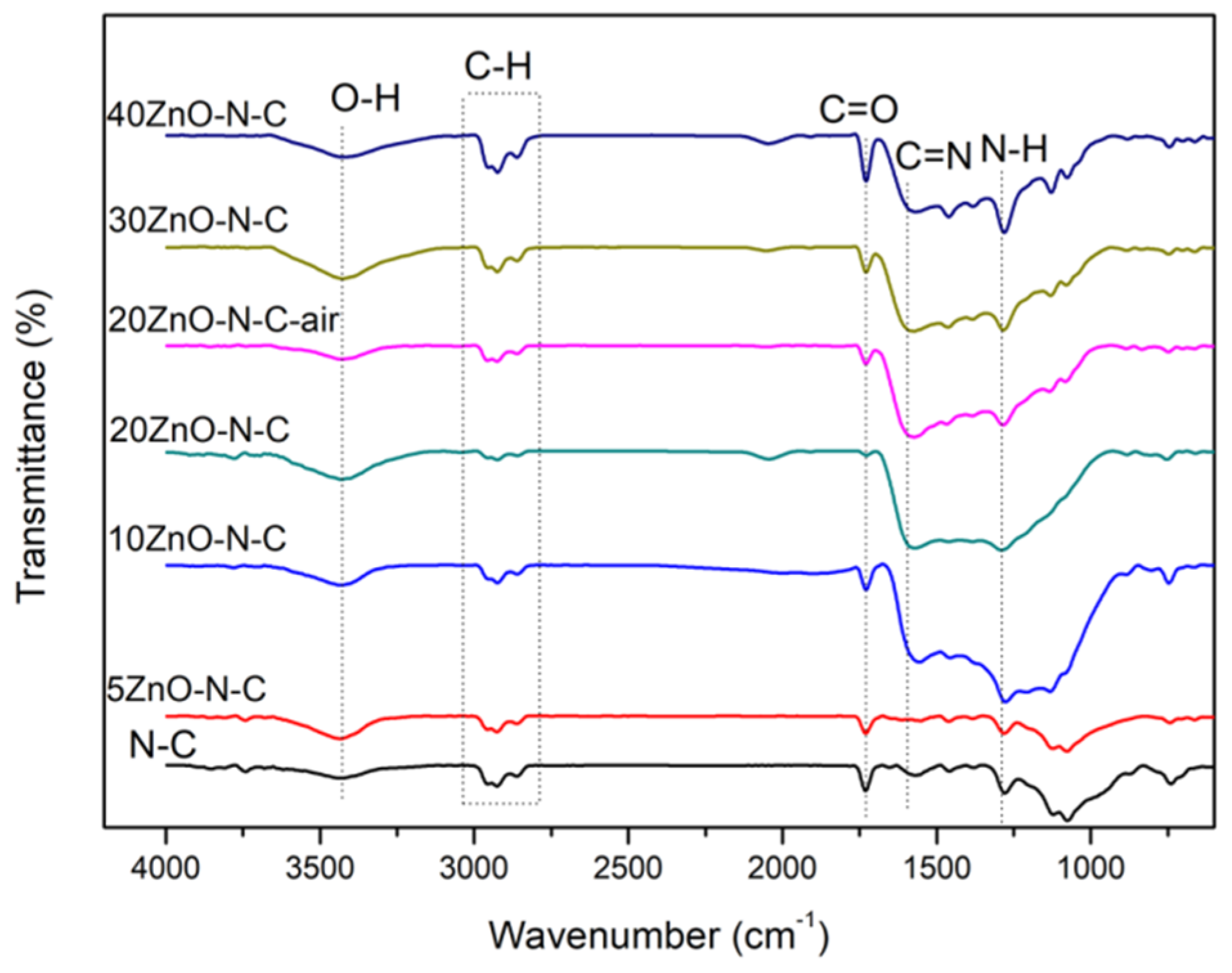

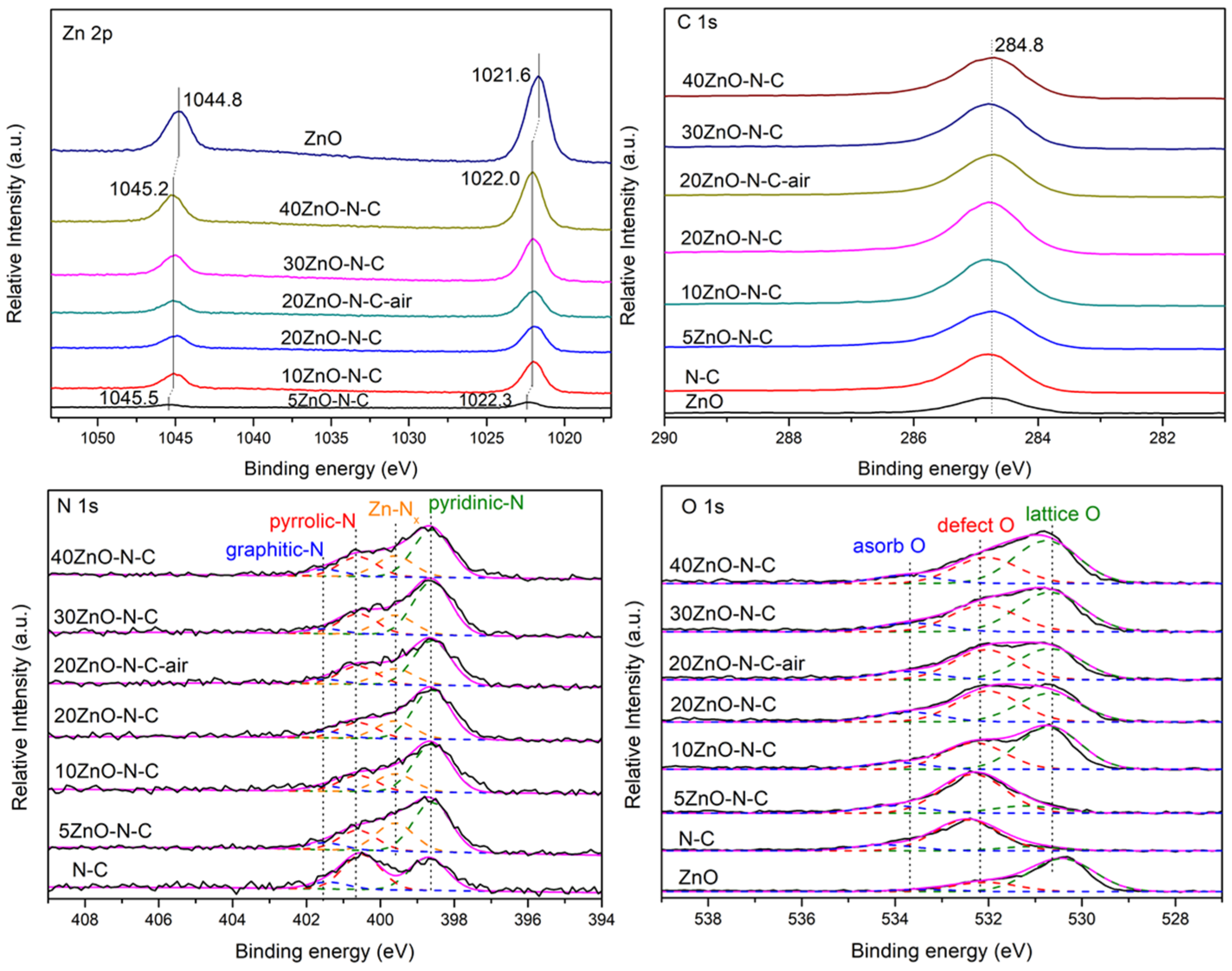

3.2. The Surface Composition and State of the Catalyst

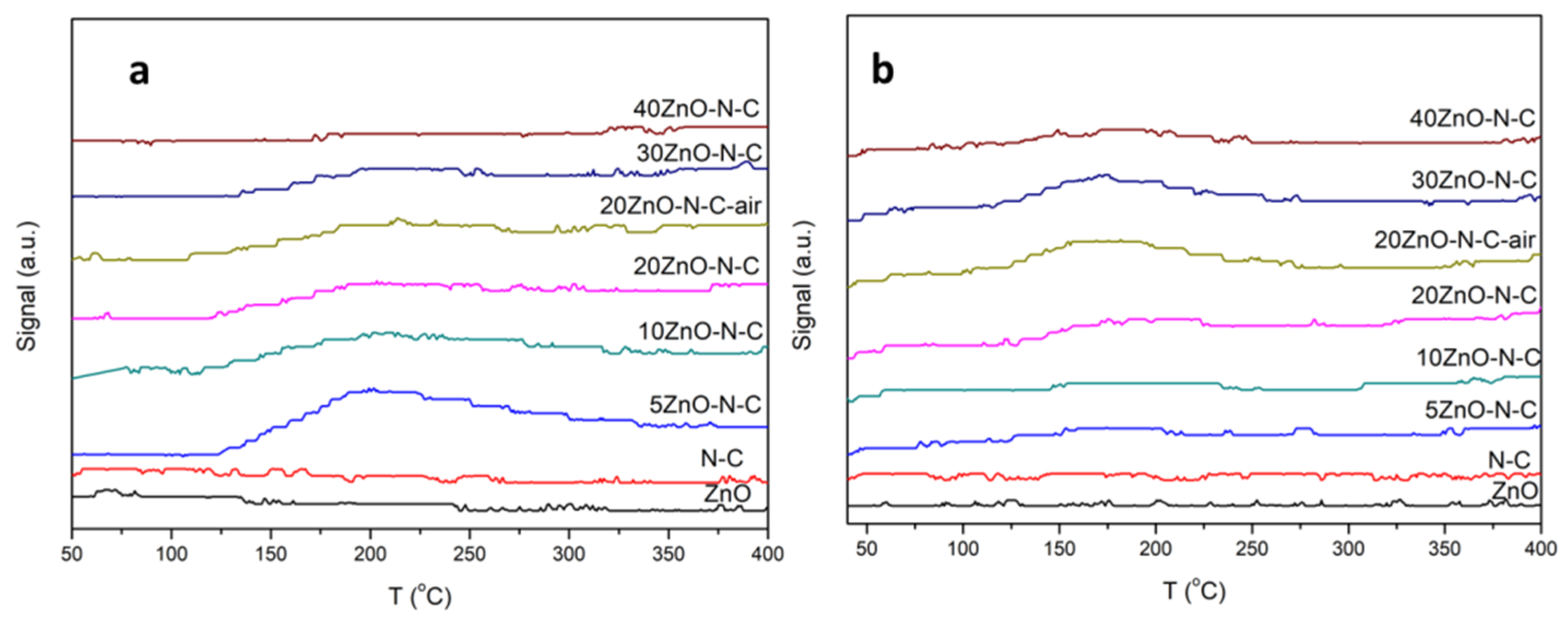

3.3. The Acidity and Basicity of the Catalysts

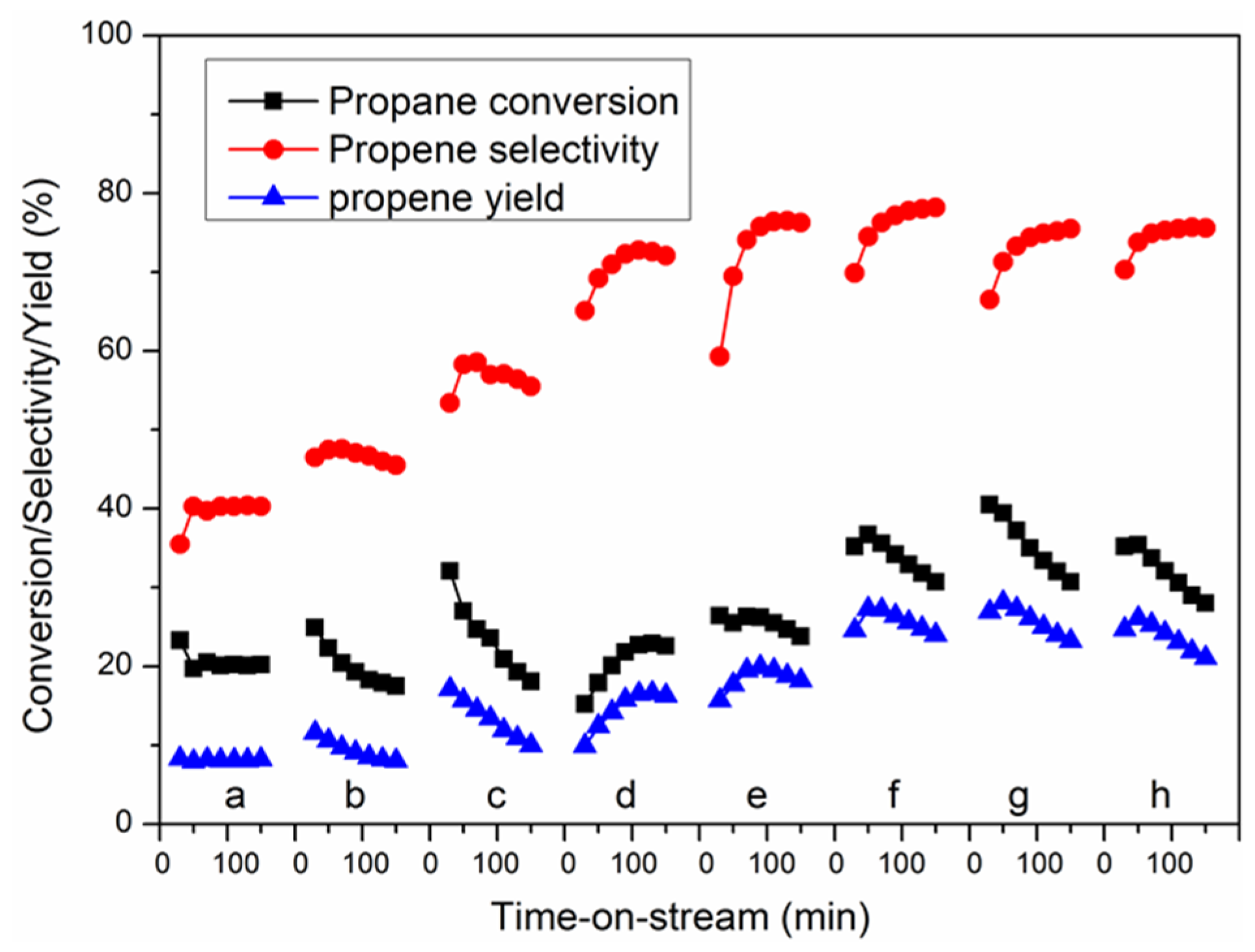

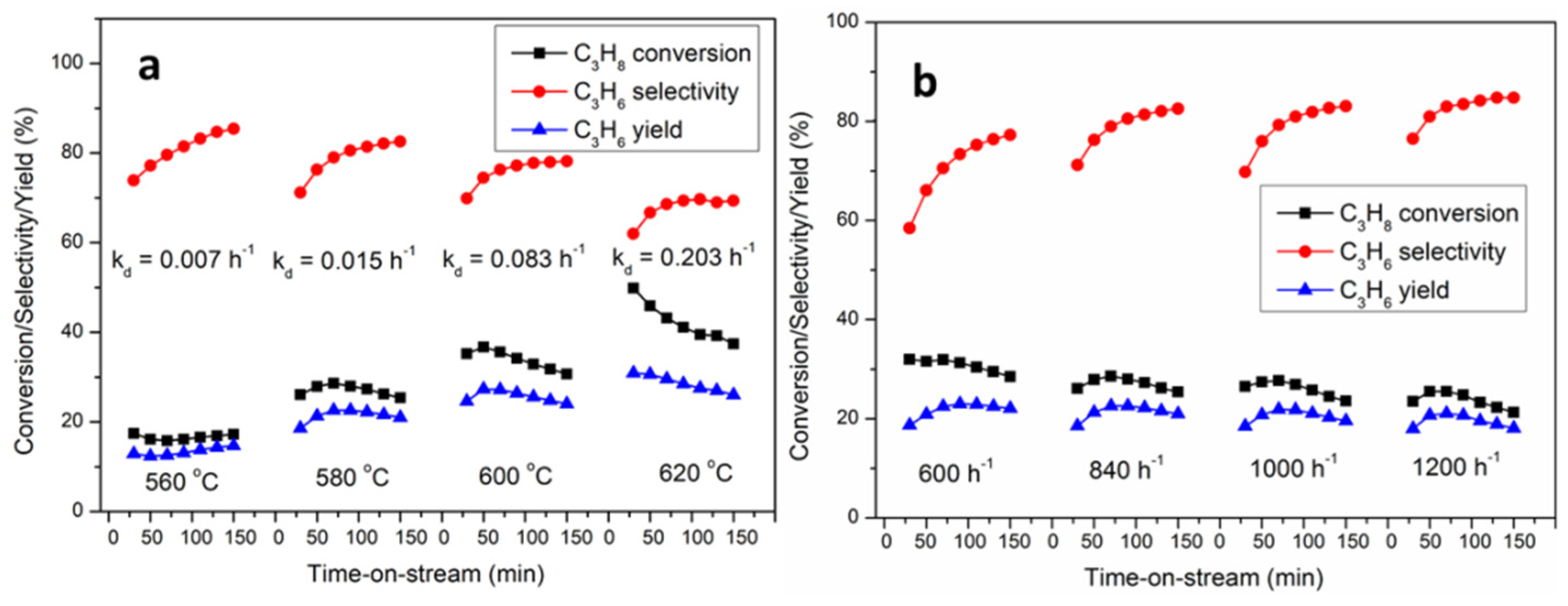

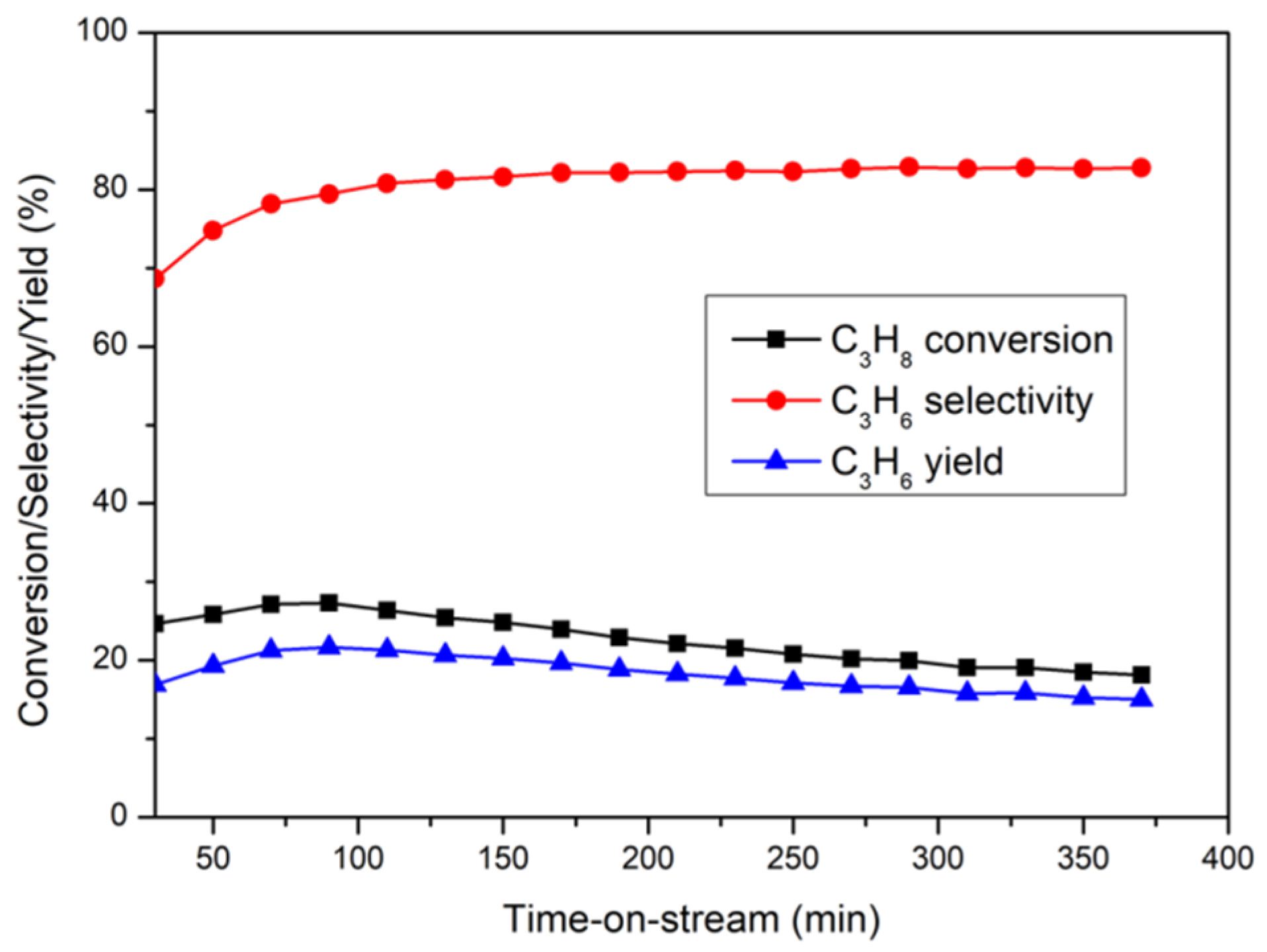

3.4. Catalytic Performance and Stability for PDH

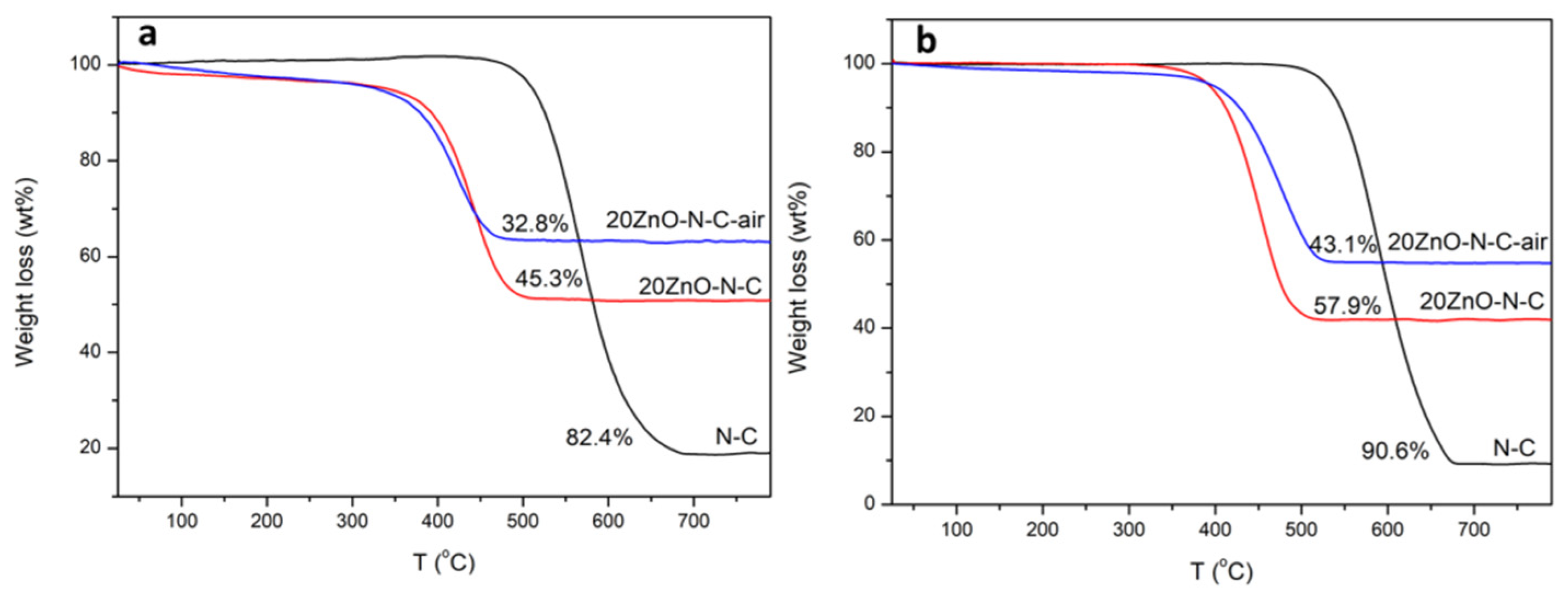

3.5. The Deactivation of the Catalyst

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data and code availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest or competing interests

Ethical approval

References

- van Koppen PAM, Bowers MT, Haynes CL, Armentrout PB (1998) Reactions of ground-state Ti+ and V+ with propane: Factors that govern C-H and C-C bond cleavage product branching ratios. J Am Chem Soc 120: 5704-5712. [CrossRef]

- Ali W, Prakash G, Maiti D (2021) Recent development in transition metal-catalysed C-H olefination. Chem Sci 12: 2735-2759. [CrossRef]

- Waku T, Biscardi JA, Iglesia E (2003) Active, selective, and stable Pt/Na-[Fe]ZSM5 catalyst for the dehydrogenation of light alkanes. Chem Commun: 1764-1765. [CrossRef]

- Zhang JS, Nakaya Y, Shimizu K, Furukawa S (2023) Surface engineering of titania boosts electroassisted propane dehydrogenation at low temperature. Angew Chem Int Ed. [CrossRef]

- Lu JL, Fu BS, Kung MC, Xiao GM, Elam JW, Kung HH, Stair PC (2012) Coking- and sintering-resistant palladium catalysts achieved through atomic layer deposition. Science 335: 1205-1208. [CrossRef]

- Sattler JJHB, Ruiz-Martinez J, Santillan-Jimenez E, Weckhuysen BM (2014) Catalytic dehydrogenation of light alkanes on metals and metal oxides. Chem Rev 114: 10613-10653. [CrossRef]

- Sun YN, Wu YM, Tao L, Shan HH, Wang GW, Li CY (2015) Effect of pre-reduction on the performance of Fe2O3/Al2O3 catalysts in dehydrogenation of propane. J Mol Catal A Chem 397: 120-126. [CrossRef]

- M Cheng, Zhao HH, Yang J, Zhao J, Yan L, Song HL, Chou LJ (2018) The catalytic dehydrogenation of isobutane and the stability enhancement over Fe incorporated SBA-15. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 266: 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Zhao ZJ, Wu TF, Xiong CY, Sun GD, Mu RT, Zeng L, Gong JL (2018) Hydroxyl-mediated non-oxidative propane dehydrogenation over VOx/γ-Al2O3 catalysts with improved stability. Angew Chem Int Ed 57: 6791-6795. [CrossRef]

- Cheng E, McCullough L, Noh H, Farha O, Hupp J, Notestein J (2020) Isobutane dehydrogenation over bulk and supported molybdenum sulfide catalysts. Ind Eng Chem Res 59: 1113-1122. [CrossRef]

- Han SL, Zhao D, Otroshchenko T, Lund H, Bentrup U, Kondratenko VA, Rockstroh N, Bartling S, Doronkin DE, Grunwaldt J, Rodemerck U, Linke D, Gao ML, Jiang GY, Kondratenko EV (2020) Elucidating the nature of active sites and fundamentals for their creation in Zn-containing ZrO2-based catalysts for nonoxidative propane dehydrogenation. ACS Catal 10: 8933-8949. [CrossRef]

- Wang YS, Suo YJ, Ren JT, Wang Z, Yuan ZY (2021) Spatially isolated cobalt oxide sites derived from MOFs for direct propane dehydrogenation. J Colloid Interf Sci 594: 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Zeng L, Zhao ZJ, Tian H, Wu TF, Gong JL (2016) Platinum-modified ZnO/Al2O3 for propane dehydrogenation: minimized platinum usage and improved catalytic stability. ACS Catal 6: 2158-2162. [CrossRef]

- Cheng M, Zhao HH, Yang J, Zhao J, Yan L, Song HL, Chou LJ (2019) Facile synthesis of ordered mesoporous zinc alumina catalysts and their dehydrogenation behavior. RSC Adv 9: 9828-9837. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Chen SG, Yang N, Deng MM, Ibraheem S, Deng JH, Li J, Li L, Wei ZD (2019) Ultrahigh-loading zinc single-atom catalyst for highly efficient oxygen reduction in both acidic and alkaline media. Angew Chem Int Ed 58: 7035-7039. [CrossRef]

- Shi XX, Chen S, Li S, Yang YQ, Guan QQ, Ding JN, Liu XY, Liu Q, Xu WL, Lu JL (2023) Particle size effect of SiO2-supported ZnO catalysts in propane dehydrogenation. Catal Sci Technol 13: 1866-1873. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Y, Lobo RF (2023) Zinc speciation and propane dehydrogenation in Zn/H-ZSM-5 catalysts. ACS Catal 13: 4971-4984. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer NM, Hu B, Das U, Kim H, Greeley J, Curtiss LA, Stair PC, Miller JT, Hock AS (2014) Propylene hydrogenation and propane dehydrogenation by a single-Site Zn2+ on silica catalyst. ACS Catal 4: 1091-1098. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi SMT, Mezari B, Magusin PCMM, Pidko EA, Hensen EJM (2012) Structure and reactivity of Zn-modified ZSM-5 zeolites: The importance of clustered cationic Zn complexes. ACS Catal 2: 71-83. [CrossRef]

- D Zhao, YM Li, SL Han, YY Zhang, GY Jiang, YJ Wang, K Guo, Z Zhao, CM Xu, RJ Li, CC Yu, J Zhang, BH Ge, EV Kondratenko (2019) ZnO Nanoparticles encapsulated in nitrogen-doped carbon material and silicalite-1 composites for efficient propane dehydrogenation. iScience 13: 269-276. [CrossRef]

- Cao TL, Dai XY, Fu Y, Qi W (2023) Coordination polymer-derived non-precious metal catalyst for propane dehydrogenation: Highly dispersed zinc anchored on N-doped carbon. Appl Surf Sci 607: 155055. [CrossRef]

- Feng QP, Xie XM, Liu YT, Zhao W, Gao YF (2007) Synthesis of hyperbranched aromatic polyamide-imide and its grafting onto multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J Appl Polym Sci 106: 2413-2421. [CrossRef]

- Duan GG, Liu SW, Jiang SH, Hou HQ (2019) High-performance polyamide-imide films and electrospun aligned nanofibers from an amide-containing diamine. J Mater Sci 54: 6719-6727. [CrossRef]

- Singh K, Nancy, Kaur H, Sharma PK, Singh G, Singh J (2023) ZnO and cobalt decorated ZnO NPs: Synthesis, photocatalysis and antimicrobial applications. Chemosphere 313: 137322. [CrossRef]

- Han JH, Johnson I, Lu Z, Kudo A, Chen MW (2021) Effect of local atomic structure on sodium ion storage in hard amorphous carbon. Nano Lett 21: 6504-6510. [CrossRef]

- Z Liu, ZY Du, W Xing, ZF Yan (2014) Facial synthesis of N-doped microporous carbon derived from urea furfural resin with high CO2 capture capacity. Mater Lett 117: 273-275. [CrossRef]

- Cao PK, Liu YM, Quan X, Zhao JJ, Chen S, Yu HT (2019) Nitrogen-doped hierarchically porous carbon nanopolyhedras derived from core-shell ZIF-8@ZIF-8 single crystals for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. Catal Today 327: 366-373. [CrossRef]

- Wang LH, Han XD, Zhang YF, Zheng K, Liu P, Zhang Z (2011) Asymmetrical quantum dot growth on tensile and compressive-strained ZnO nanowire surfaces. Acta Mater 59: 651-657. [CrossRef]

- Wong TI, Tan HR, Sentosa D, Wong LM, Wang SJ, Feng YP (2012) Epitaxial growth of ZnO film on Si(111) with CeO2(111) as buffer layer. J Phys D Appl Phys 45: 415306. [CrossRef]

- JG Yu, HZ Xing, QQ Zhao, HB Mao, Y Shen, JQ Wang, ZS Lai, ZQ Zhu (2006) The origin of additional modes in Raman spectra of N+-implanted ZnO. Solid State Commun 138: 502-504. [CrossRef]

- Zhao HH, Song HL, Zhao J, Yang J, Yan L, Chou LJ (2020) The Reactivity and deactivation mechanism of Ru@C catalyst over hydrogenation of aromatics to cyclohexane derivatives. Chemistryselect 5: 4316-4327. [CrossRef]

- Liang MF, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wang FY, Miao ZC, Diao LC, Mu JL, Zhou J, Zhuo SP (2022) Understanding the role of metal and N species in M@NC catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. Appl Catal B: Environ 306: 121115. [CrossRef]

- Gunawan ER, Suhendra D, Hidayat I, Kurniawati L (2018) Optimization of alkyldiethanolamides synthesis from terminalia catappa L. kernel oil through enzymatic reaction, J Oleo Sci 67: 949-955. [CrossRef]

- Przepiórski J, Skrodzewicz M, Morawski AW (2004) High temperature ammonia treatment of activated carbon for enhancement of CO2 adsorption. Appl Surf Sci 225: 235-242. [CrossRef]

- Qi W, Liu W, Zhang BS, Gu XM, Guo XL, Su DS (2013) Oxidative dehydrogenation on nanocarbon: Identification and quantification of active sites by chemical titration, Angew Chem Int Ed 52: 14224-14228. [CrossRef]

- Sun XY, Li B, Su DS (2014) Revealing the nature of the active site on the carbon catalyst for C-H bond activation, Chem Commun 50: 11016-11019. [CrossRef]

- Zheng FC, Yang Y, Chen QW (2014) High lithium anodic performance of highly nitrogen-doped porous carbon prepared from a metal-organic framework. Nat Commun 5: 5261 . [CrossRef]

- QQ Guo, Jing W, Hou YQ, Huang ZG, M GQ a, Han XJ, Sun DK (2015) On the nature of oxygen groups for NH3-SCR of NO over carbon at low temperatures. Chem Eng J 270: 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Ren YJ, Zhang F, Hua WM, Yue YH, Gao Z (2009) ZnO supported on high silica HZSM-5 as new catalysts for dehydrogenation of propane to propene in the presence of CO2. Catal Today 148: 316-322. [CrossRef]

- Zhao HH, Song HL, Chou LJ, Zhao J, Yang J, Yan L (2017) Insight into the structure and molybdenum species in mesoporous molybdena-alumina catalysts for isobutane dehydrogenation. Catal Sci Technol 7: 3258-3267. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Liu X, Blume R, Zhang AH, Schloegl R, Su DS (2008) Surface-modified carbon nanotubes catalyze oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane. Science 322: 73-77. [CrossRef]

- Otroshchenko T, Jiang G, Kondratenko VA, Rodemerck U, Kondratenko EV (2021) Current status and perspectives in oxidative, non-oxidative and CO2-mediated dehydrogenation of propane and isobutane over metal oxide catalysts. Chem Soc Rev 50: 473-527. [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Atomic content (%) | ||||||||

| Zn | N | O | C | ||||||

| Pyridinic-N | Zn-Nx | Pyrrole-N | Graphitic-N | Zn-O | C=O | O-H | |||

| N-C | 0 | 1.62 | 0 | 1.72 | 0.34 | 0 | 6.96 | 2.02 | 87.36 |

| 5ZnO-N-C | 1.46 | 3.44 | 1.95 | 1.39 | 0.48 | 1.29 | 6.02 | 1.25 | 82.73 |

| 10ZnO-N-C | 6.52 | 2.77 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.29 | 5.37 | 3.78 | 1.09 | 78.20 |

| 20ZnO-N-C | 5.26 | 3.16 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 0.40 | 4.32 | 4.20 | 1.02 | 79.49 |

| 30ZnO-N-C | 8.48 | 3.30 | 1.19 | 1.25 | 0.30 | 6.63 | 4.86 | 1.22 | 72.76 |

| 40ZnO-N-C | 10.73 | 3.04 | 1.34 | 1.26 | 0.43 | 8.20 | 4.66 | 1.33 | 69.02 |

| 20ZnO-N-C-air | 6.27 | 2.45 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.25 | 5.53 | 5.39 | 1.58 | 76.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).