1. Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysts have become a crucial part of many industrial activities, such as organic synthesis, oil refining, and pollution control [

1]. Modern heterogeneous catalysts consist of several elements in precise proportions [

1] and are optimized to obtain the greatest reaction rate, which in turn results in optimal selectivity [

1]. The heterogeneous catalyst performance can be improved by modifying the support using approaches such as nanotechnology and nanoscience or controlling the pore structure [

1,

2]. However, the support must retain its specific properties, such as porosity, surface area, dispersion, selectivity, and activity [

3,

4].

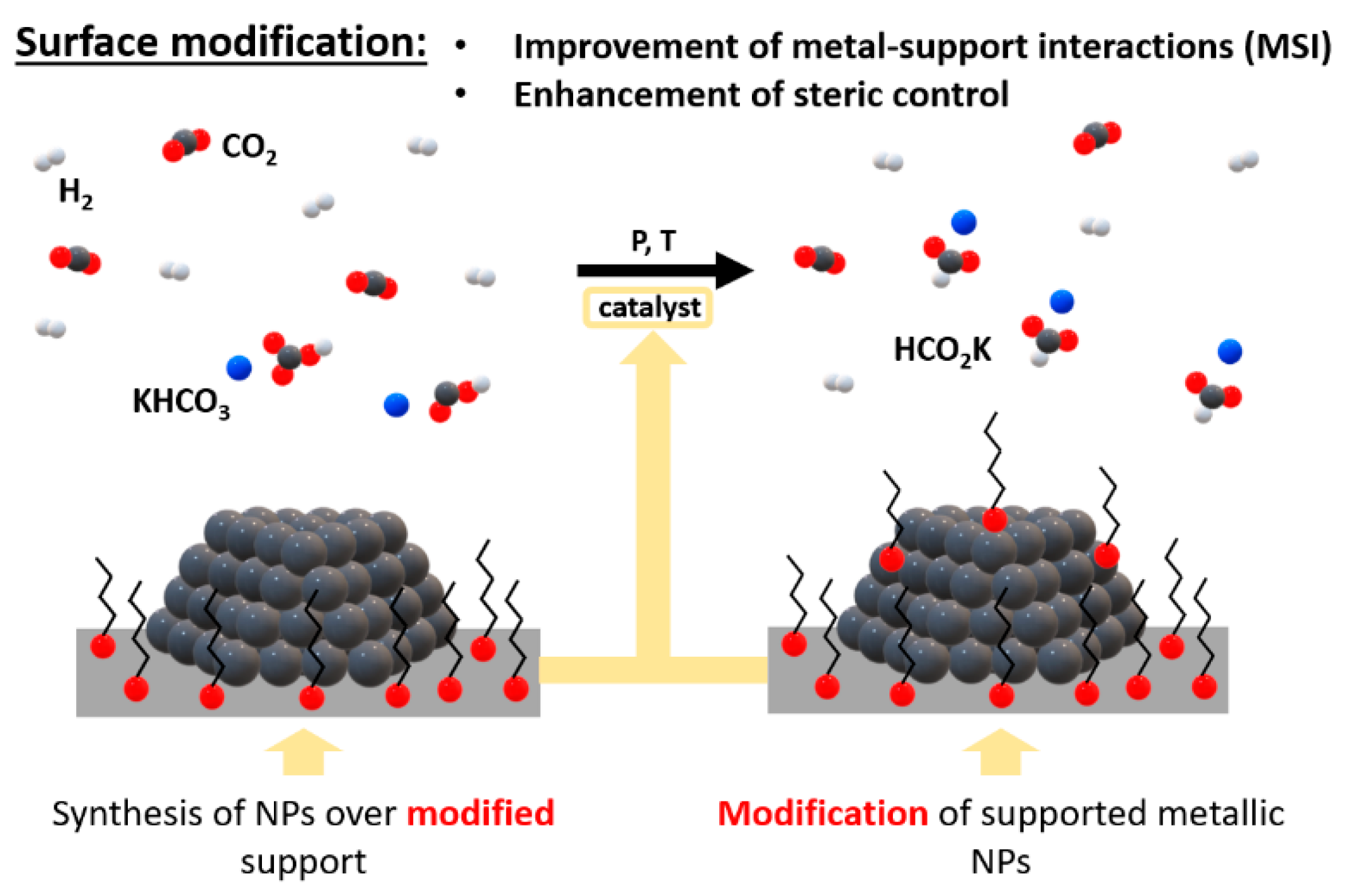

In the design of new catalysts, the appropriate metal-support interactions (MSI) must be achieved, and their tuning can be completed through adjustments of either the composition and/or morphology of support and active phase or through the modifications of their surface (

Scheme 1) [

5,

6]. However, changes in composition and morphology can affect their nature [

7]. Surface modifications can enhance steric control or provide hydrophilic/hydrophobic character that can be suitable for the target substrates and catalysis media [

8]. In this area, the use of organic self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) is of particular interest since these organic modifiers can act as spacers between NPs to minimize sintering and improve stability/recyclability of the catalyst [

9,

10]. Moreover, depending on the functional groups in these modifiers, the catalyst activity can be enhanced through interactions with the substrate [

11] or by conferring a hydrophobic / hydrophilic character to the system to favor catalyst-substrate interactions [

12].

Modification of carbon and silica supported catalysts with organic molecules were previously reported to cover metallic nanoparticles with alkylic chain [

13] or with groups containing amine functionalities [

14] to produce catalytic materials for CO

2 hydrogenation into formate. Organosilanes are among the most used molecules to modify supports and constitute a type of inorganic/organic hybrid materials [

15]. Aminoalkylsilanes, such as (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), are the most commonly reported organosilanes [

16]. Modification occurs through silanization, which is a process that covers a surface such as metal oxide with chloro or alkoxysilane [

17]. Using APTES, this process starts with the hydrolysis of the ethoxy groups that is catalyzed by water, leading to the formation of silanols that condense with the surface hydroxyls to form a monolayer [

18]. The most accepted chemisorption of APTES onto TiO

2 implies one or two Si−O−Ti bonds [

16,

19]. Moreover, APTES can also be applied directly over metallic nanoparticles for their stabilization and functionalization [

20,

21].

Liu et al. reported that APTES directly participates in the synthesis of a protonated Schiff-base which covers Au NPs during the dehydrogenation of FA into CO

2 and H

2 [

22]. Later, the same authors developed a new Au based catalyst for the hydrogenation of CO

2 into formic acid in which the SiO

2 support was modified by APTES and a Schiff-base, reaching a TON of 14470 over 12 h at 90 ºC [

23]. The same year, Mori et al. reported PdAg NPs supported over amine-functionalized mesoporous silica for the reversible CO

2 hydrogenation and release of H

2 [

24]. DFT calculations revealed that the presence of amine affects the O-H dissociation of FA and favors the adsorption of CO

2 in hydrogenation. Additionally, the catalyst could be recovered and reused for 3 runs without loss of activity.

Srivastava reported the preparation of Ru NPs supported over various amine organosilane modified SBA-15 mesoporous silica and their application as catalyst in the hydrogenation of CO

2 into formic acid [

25]. Primary, secondary and tertiary amines were tested and the use of the primary amine provided the highest catalytic activity.

Ionic Liquids (ILs) constitute another type of interesting molecules for support modification [

26,

27] and in catalytic reactions involving CO

2, it was reported that the interactions between IL and CO

2 usually depend on the anion. Indeed, basic anions such as acetate in combination with 1,3-dialkylimidazolium enhanced such interactions [

28] and this type of ILs were used in the hydrogenation of CO

2 to formic acid [

29]. In recent years, Leitner and co-workers reported the preparation of metallic nanoparticles in ionic liquids covalently grafted onto SiO

2 by silanization [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. They recently reported a Ru-based catalyst supported over imidazolium-based supported ionic liquid phase (SILP) for the hydrogenation of CO

2 into formate in the presence of NEt

3 [

35]. The authors first covalently modified the SiO

2 surface with ILs via silanization while the synthesis of the Ru NPs was performed in a second step using the organometallic approach [

36]. Modifications of the alkyl chain and anion resulted very important to modulate the NPs properties and resulted in an increase of the TON by 2 or 10-fold when compared with unmodified Ru/SiO

2 catalyst. Using H/D exchange experiments, the authors determined that the modification favored the desorption of formate from the catalyst surface. However, in recycling experiments, a significant loss of activity was observed, which was attributed to the leaching of IL from the support due to the use of NEt

3 + H

2O as solvent system. Other authors reported Pd NPs supported over poly(ionic liquid)s (PILs) for the hydrogenation of CO

2 into formic acid [

37]. Using this catalytic system, a TOF of 1190 h

-1 was obtained in the presence of NEt

3 aqueous solution and good recyclability was observed during several runs [

37].

Organophosphonic acids (PAs) constitute another common type of molecules used for the modification of support surfaces. These RPO(OH)

2 compounds were especially used to modify metal oxide surfaces [

38]. However, when PAs are used for surface modification, an additional annealing or aging treatment is necessary to produce condensation reactions and form strong bonds between PAs and metal oxide [

10].

In a previous report from our group, ligand capped nanocatalysts were prepared over supports of different nature (metal oxides and carbon based) and tested in Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of CO

2 to formate. The best performance was achieved using TiO

2-based catalysts [

39]. However, upon recycling, a rapid decrease of activity was observed. Here, modifications of the TiO

2 support/catalyst are described using Si and P based molecular modifiers. The newly prepared materials were characterized and tested in the catalytic hydrogenation of CO

2 into formate. The effect of these modifications on the activity and recyclability of these catalysts was particularly looked at.

2. Results and Discussion

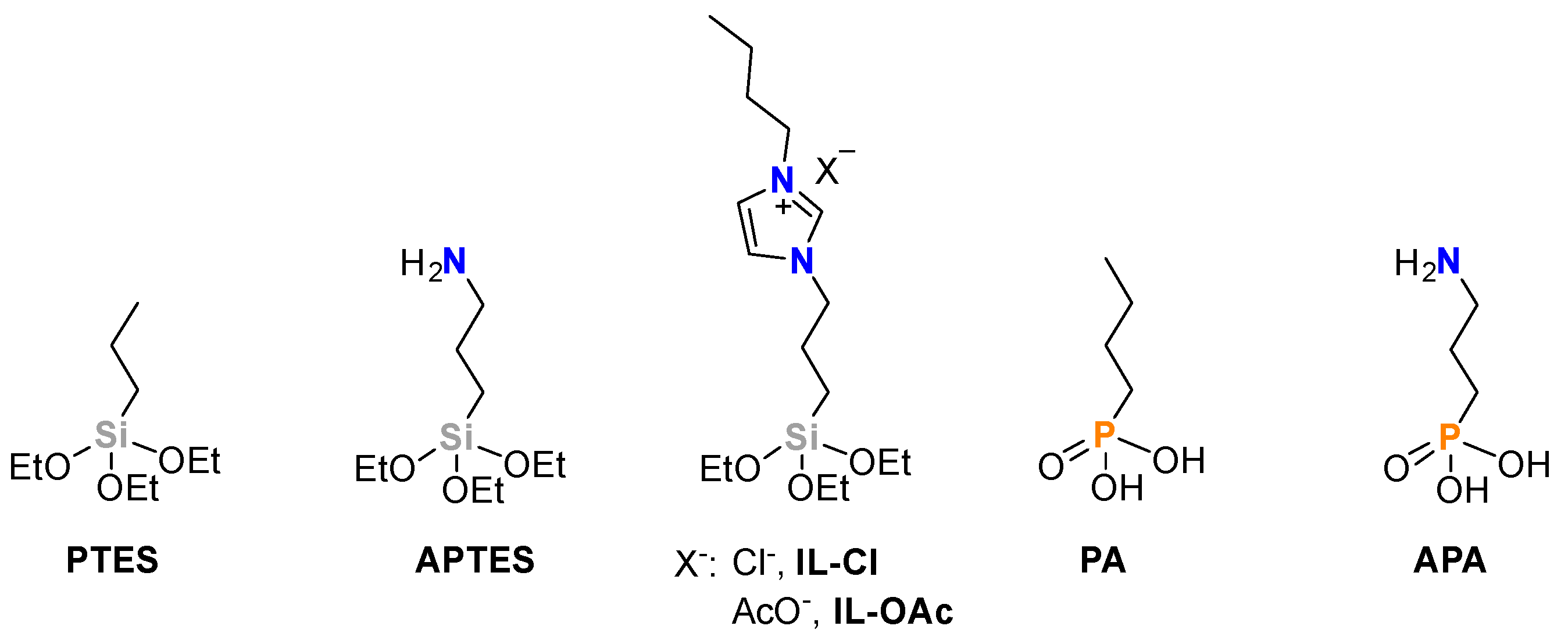

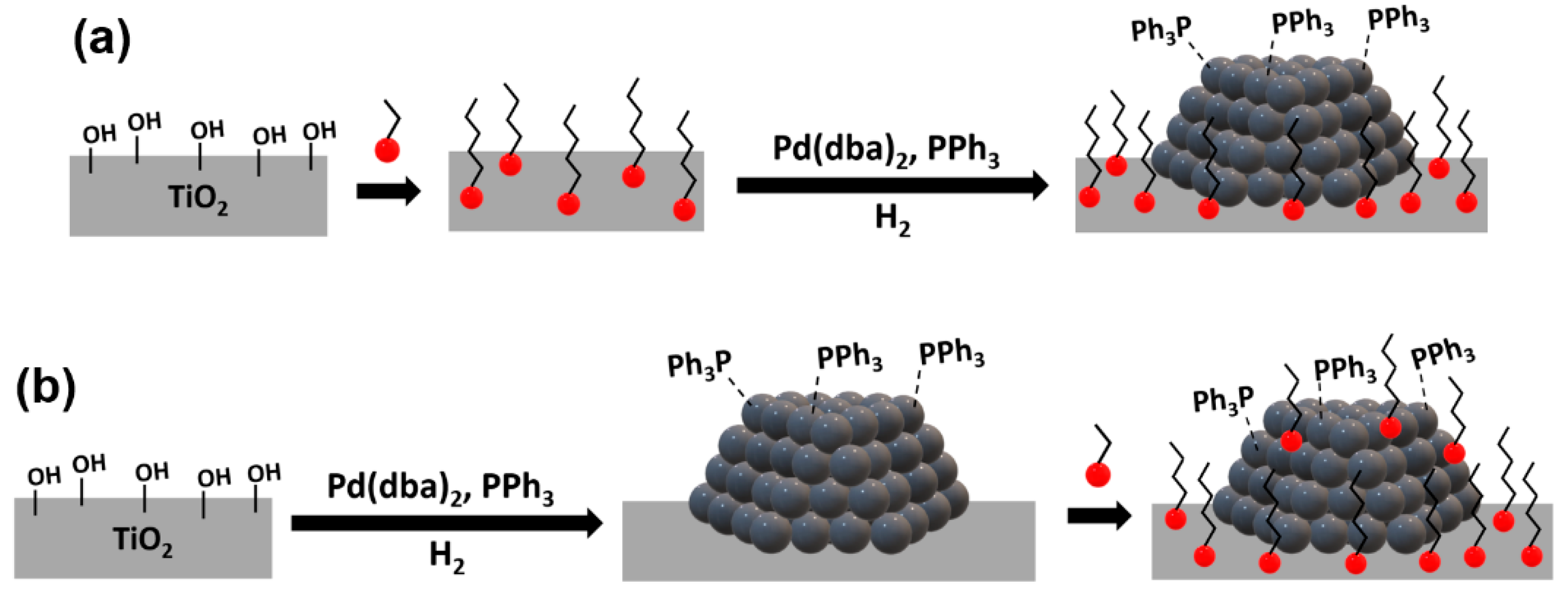

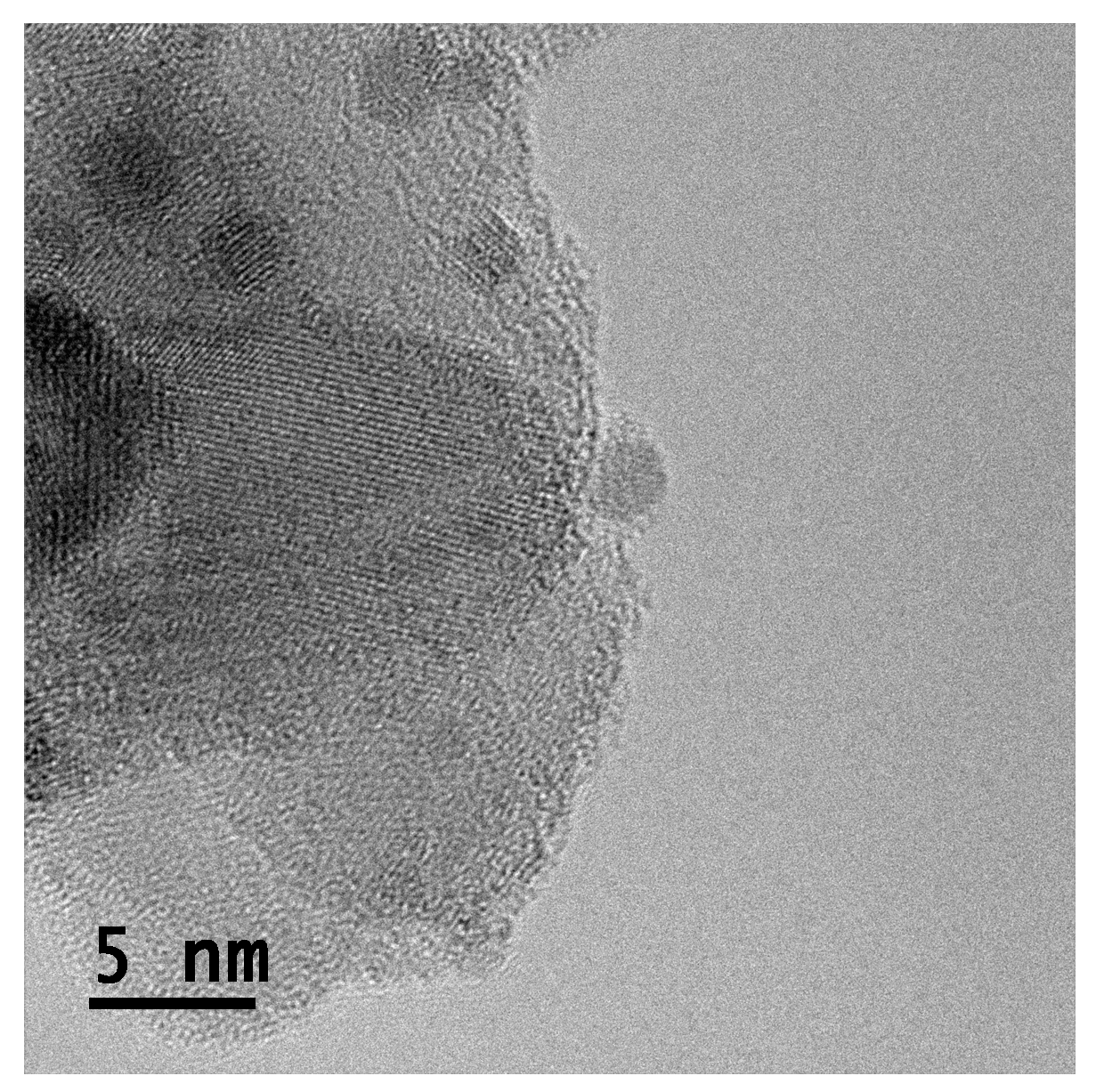

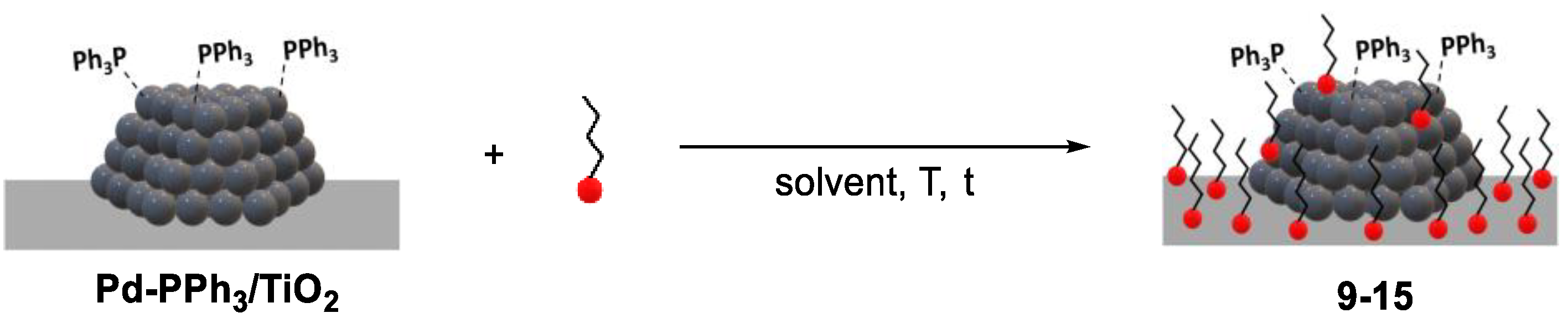

The modified catalysts were prepared according to two distinct approaches using triethoxysilanes (TESs) and organophosphonic acids (PAs) as modifiers (

Figure 1).

In the first approach, the TiO

2 support was modified prior to Pd NP deposition whereas in the second approach, the Pd NPs were initially supported onto TiO

2 [

39] and the modifiers were reacted subsequently (

Scheme 2).

The grafting of the RSi(OEt)

3 modifiers onto TiO

2 was carried out following literature procedures (

Figure 1) [

19,

40]. In a typical synthesis, the reaction was performed in a EtOH:H

2O solution or absolute EtOH. The mixture was then centrifuged and the solid washed several times with H

2O and EtOH and dried under vacuum for several hours.

Optimization of synthesis parameters such as concentration of APTES, APTES/TiO

2 ratio, temperature and time was initially performed (

Table S1). Organophosphonic acids (PAs) containing a butyl chain or a 3-propylamine group were also used as modifiers (

Figure 1). The preparations were carried out using a modifier concentration of 0.01 M at room temperature. For these modifiers, an additional annealing or aging treatment of the material at 120 ºC was performed.

To confirm the successful modification of TiO

2, the samples were first analyzed by FT-IR analysis (

Figure S2, Figure S5 and Figure S7), which corroborated that the condensation between surface TiO

2 hydroxyl groups and silanol groups had taken place via the detection of CH

2 and C-N stretching bands.

Quantification of the anchoring of the modifiers was carried via TGA analysis (

Figure S3, S6 and S8, and Table S2). Apart from the low temperature (< 200 ºC) weight loss associated to the removal of water, a new weight loss between 200 and 450 ºC was detected for the modified TiO

2 samples and was attributed to the loss of anchored modifiers. Variations between 1 and 3.5 wt% were measured depending on the nature and concentration of modifier used.

In view of these results, it was concluded that a series of functionalized TiO

2 supports was successfully prepared using organosilanes and organophosphonic acids as modifiers. FT-IR analysis confirmed the presence of these modifiers at the surface of the TiO

2 supports (

Figure S2, Figure S5 and Figure S7) and TGA (

Figure S3, Figure S6, Figure S8 and Table S2) provided quantitative information about these systems.

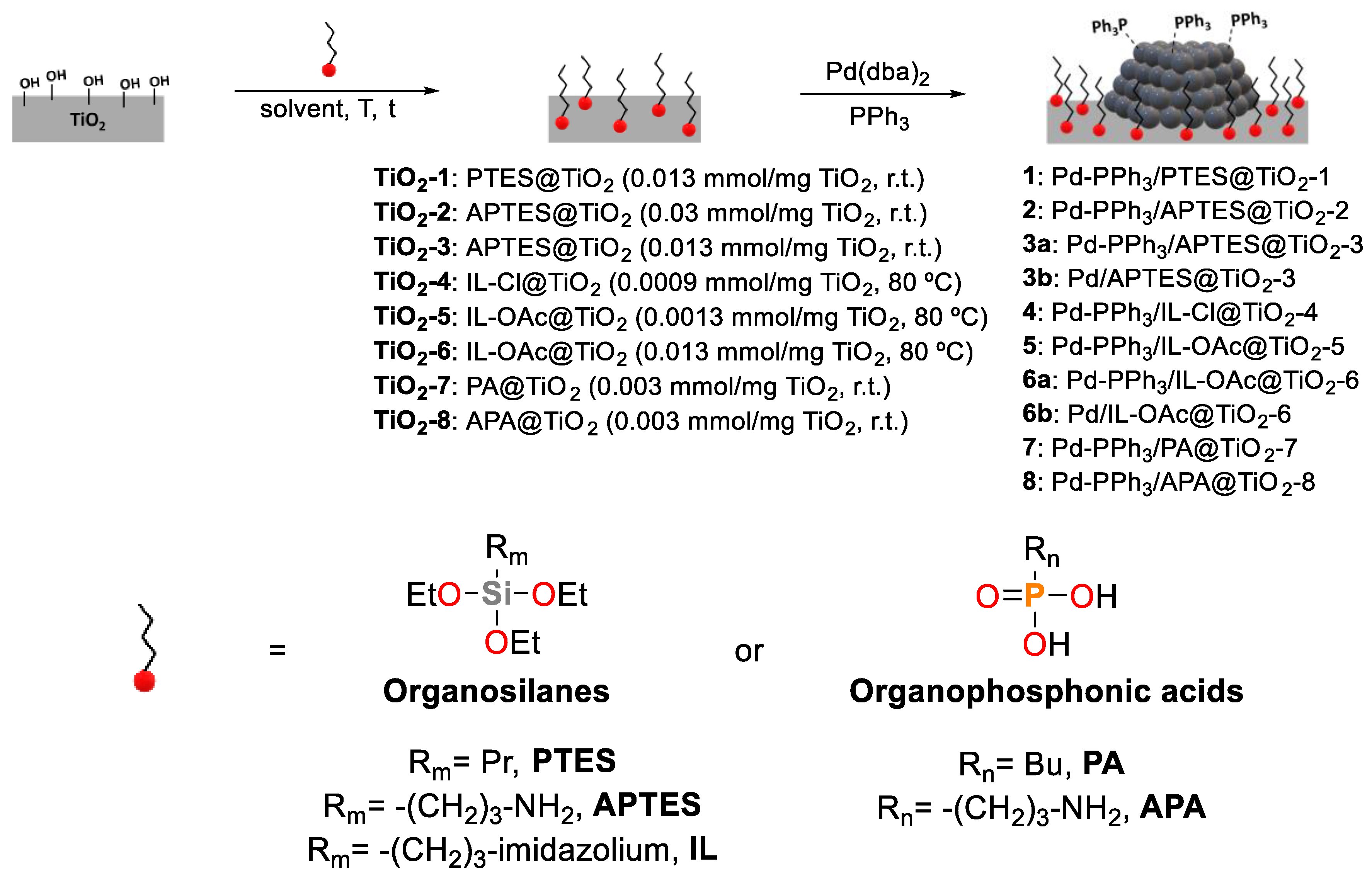

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Supported PPh3-Capped Pd NPs over Modified TiO2

The synthesis of Pd NPs was carried out over the modified TiO

2 supports in the presence of PPh

3 as stabilizing ligand (

Scheme 3). The materials were prepared by decomposition of Pd(dba)

2 under H

2 pressure at room temperature using THF as solvent. A nominal Pd loading of 4 wt% was targeted.

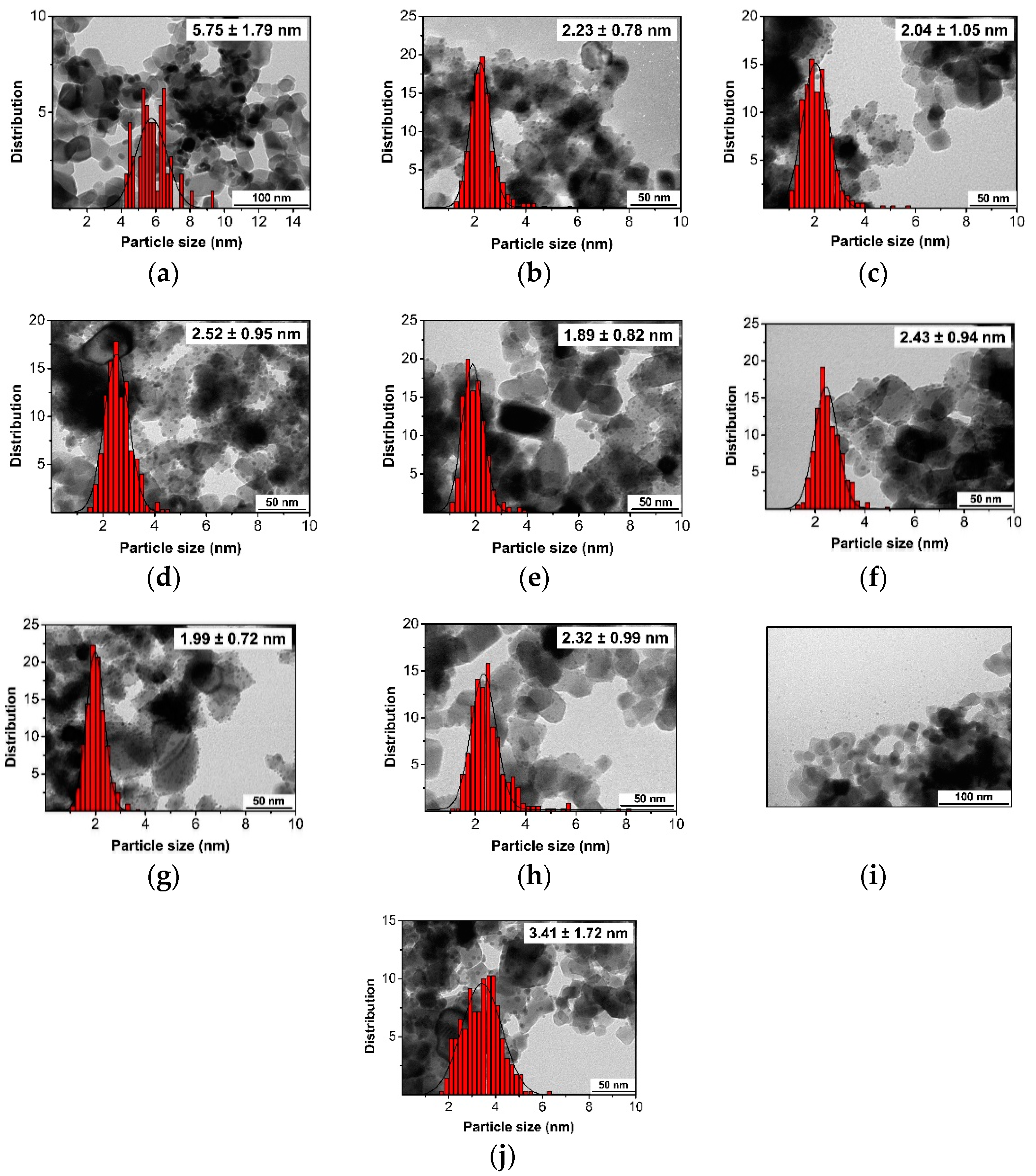

The newly prepared systems were characterized by TEM, HR-TEM, ICP, XPS, FT-IR and TGA. TEM images of the newly synthesized materials are displayed in

Figure 2. In all cases, small and crystalline Pd NPs were formed. The sizes and distributions obtained from TEM measurements and ICP results are summarized in

Table S3. In all cases, Pd loadings between 2.7 and 3.5 wt% were measured.

For catalyst

1 bearing PTES was the TiO

2 modifier (

Figure 2a), the resulting NPs exhibited a size of 5.75 nm with a broad distribution. Some agglomerations of Pd-NPs were also observed. When TiO

2 modified with APTES were employed as support (

Figure 2b,

Figure 2c and

Figure 2d), the Pd NPs sizes ranged from 2.04 nm to 2.52 nm while the Pd content was between 2.75% and 3.36 wt%. The material

2 was also analyzed by HR-TEM (

Figure S10). EDS mapping (

Figure S10c) revealed the presence of Si at the surface of TiO

2 which confirmed the presence of APTES. The catalyst

3b (

Figure 2d), synthesized in the absence of ligand, was also analyzed by HR-TEM (

Figure S11). For this catalyst, the same edge of Si is appreciated (

Figure S11 (c)). The difference in Pd NP size observed for the PTES modified support and those modified with APTES clearly indicated the role of the amine function in the NP stabilization. The largest NPs were obtained when the synthesis was performed in the absence of PPh

3, indicating that this ligand also played a role in the NP stabilization, although to a much lesser extent than the amine group from the support.

When the support was functionalized by organosilanes containing an IL moiety, particles sizes between ca. 1.9 and 2.4 nm were measured (

Figure 2e-2h). The catalyst

4 containing a support modified by IL was also analyzed by HR-TEM and EDS (

Figure S12). Due to the low concentration of IL-Cl employed for synthesis of this catalyst, the layer of Si around TiO

2 was narrow. The presence of P was also observed, indicating that the ligand remained on the NPs. Interestingly, for the materials

5 and

6a, which contain TiO

2 modified by the same organosilane but which differ by the loading of organosilane at the support surface, only a slight difference in size was observed (2.43 vs. 1.99 nm). Moreover, when the synthesis of

6a was repeated in the absence of PPh

3 6b (Entry 8), similar size and Pd loading were observed, indicating that the ligand was not playing an important in the Pd NP stabilization when the IL-containing modifiers were used.

When the PA containing an alkylic chain was used for the modification of the support (

Figure 2i), large Pd agglomerations were observed, and nanoparticles were detected out of the support. This indicated that using this modified support, the NP stabilization was not efficient. When the PA containing an amine group was used as support modifier (

Figure 2j), the sizes of the resulting Pd NPs were 3.41 nm while similar Pd contents were obtained by ICP (

ca. 3.3 wt%) (

Table S3). Both samples revealed Pd NPs with broad distributions. The material

8, containing TiO

2 modified by PAs was analyzed by HR-TEM (

Figure S13). Small agglomerations were observed by HR-HAADF STEM. The presence of phosphorus was detected over the support and over the Pd NPs due to the presence of NH

2-PA and PPh

3.

These results therefore indicated that when organosilanes (TESs) were used to modify TiO2, the NP stabilization was efficient, resulting in smaller Pd-NPs with narrower distributions than for PA-modified supports. However, in terms of Pd loading, no relevant differences were observed. The presence of functional groups in the TESs modifiers also affected the NP stabilization since the materials containing an organosilane with a simple alkyl chain provided larger Pd NPs with broader distribution than with TESs containing either an amine function or an imidazolium group.

Moreover, when the synthesis was performed using the support with higher concentration of APTES, smaller nanoparticles were obtained. The same effect was observed when IL-containing modifiers were used.

XPS analysis was also performed for some of the

Pd-PPh3/mod@TiO2 1-8 catalysts (

Table S4 and

Figures S14, S15 and S16). The data obtained were compared with those of the unmodified

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst. All the spectra were referenced using the C1s signal and set at 285.0 eV. Presence of Si2p, N1s and P2p for

4 catalyst and N1s and P2p for

8 were detected. For Pd3d, no significant differences were observed with the unmodified

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst (335.0 eV). For all the samples, the relative amount of Pdᵟ

+ also revealed similar (

ca. 10%).

To conclude, the synthesis and characterization of the series of catalysts 1-8 based on PPh3-capped Pd NPs were carried out using modified supports. When organosilanes were employed to modify the support, smaller Pd NPs were obtained than when the supports were modified with organophosphonic acids. The presence of -NH2 group in organosilanes and organophosphonic acids influences the structure/composition of the materials since in the absence of -NH2 group, large NPs as well as unsupported NPs and agglomerations were observed.

2.2. Deposition of Modifier over TiO2 Supported PPh3-Capped Pd NPs

A new series of catalysts was synthetized by deposition of TESs and PAs modifiers over the previously synthesized

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 material (

Scheme 4). The newly prepared systems were characterized by TEM and ICP, and FT-IR, TGA, HR-TEM and XPS analyses were also performed for representative examples.

PTES or APTES was reacted with the previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 either at r.t. overnight in a mixture of 95% EtOH, 5% H2O, or at 120 ºC during 4 h using EtOH as solvent. At the end of the reaction, the samples were centrifugated, washed with milli-Q H2O and EtOH and dried overnight at 100 ºC.

The samples were initially analyzed by TEM (

Figure S17) and ICP and the data are summarized in

Table 1.

As described previously, the Pd NPs in the

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst exhibited a mean size of 2.37 ± 0.19 nm [

39]. When the catalyst was modified by deposition of PTES (Entry 1), the size of Pd NPs slightly increased to 2.65 ± 0.80 nm and a Pd content of 3.38 wt% was measured by ICP. When APTES was used as modifier, the mean size of the NPs varied from ca. 1.9 (Entry 3) to 2.7 nm (Entry 2), indicating little effect of the treatment on the Pd NPs. However, relevant decreases in Pd content were observed, indicating that the deposition of modifiers containing an amine group could induced the leaching of Pd from the previously synthesized material. The presence of P (from PPh

3) and Si (from the organosilane) was confirmed by ICP.

When modifiers containing imidazolium groups in the alkyl chain were tested, the NPs mean diameters were between ca. 1.9 (Entry 5) and 2.4 nm (Entry 4) with distributions narrower than 1 nm. However, the Pd content was lower than expected. Surprisingly, when PAs were deposited over Pd-PPh3/TiO2, larger NP sizes were observed as mean diameters of 4.45 ± 1.68 nm (Entry 6) and 3.00 ± 1.14 nm (Entry 7) were measured when PA and APA were employed, respectively. This therefore indicated that the deposition of PAs over Pd-PPh3/TiO2 caused a restructuration of the Pd NPs. In contrast, for these catalysts, the Pd content was almost the same than in the original material, thus suggesting that the reaction of the previously synthesized material with PAs does not induce Pd leaching but could produce some restructuration such as Ostwald’s ripening.

Comparing the NP sizes obtained via the two approaches described in this work, modification over the pre-synthesised

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 NPs (

Table S3) yielded smaller Pd NPs and narrower distributions than when the TiO

2 support was modified in the first step (

Table 1). However, lower Pd contents were obtained.

FT-IR and TGA analyses were also performed on

11 (

Figure S18). Comparing the FT-IR spectra of this sample with that of

TiO2-3 (

Figure S18(a)) (same concentrations and conditions), the same IR signals were detected. However, the TGA analysis revealed a greater amount of organic material at the surface of

TiO2-3 (

Figure S18(b)).

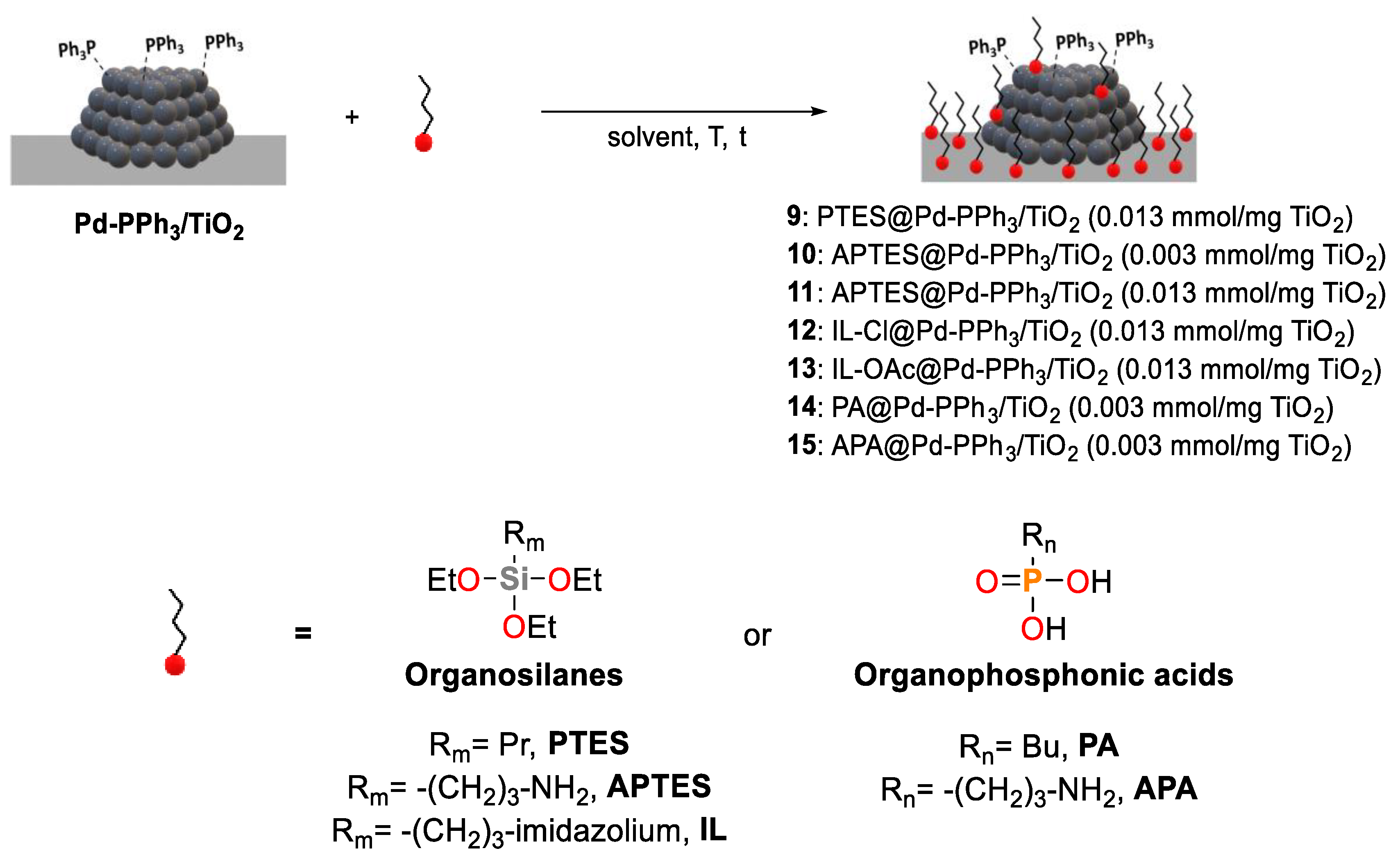

HR-TEM analysis of

11 (

Figure 3 and

Figure S20(a)), a thin layer was detected at the surface of the material. Similar observation was reported by Liu et al. using APTES as modifier [

22]. This layer was ca. 2 nm thick and wrapped both support and Pd particles. EDS mapping (

Figure S20(c)) revealed the Si-based nature of this layer at the surface of both TiO

2 and Pd NPs. Therefore, this evidenced a structural difference for the materials obtained by this approach when compared with those synthesized by reverse deposition.

When HR-TEM analysis of

12 was performed (

Figure S21), agglomerations were detected in some regions of the support (

Figure S21(a) and (b)). Microanalysis also confirmed the presence of P originating from the PPh

3 ligands.

XPS was also employed for the analysis of some of these catalysts (

Figure S24, Figure S25 and Figure S26(b)). The data obtained were compared with those of the unmodified

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst. All the spectra were referenced using the C1s signal and set at 285.0 eV. Presence of Si2p, N1s and P2p for

11 catalyst and N1s and P2p for

15 were detected. Pd spectra was studied with more detail (

Figure S26 ). When P based modifier was used (

15), no significant differences with the unmodified catalyst were observed. However, for sample containing the Si based modifiers, the BEs observed was higher. For

11, a difference of 1 eV was observed (336.0 eV) with the reference catalyst, which could be due to the interaction with the amine functional group from APTES, as previously reported by Kim et al. [

41]. They also observed an increase of BE for Pd when APTES is used on the synthesis of Pd NPs over CNTs and attributed this difference due to the interaction of Pd with amine functional groups and to the particle size (1.85 nm). A combination of interaction of amine and small size could produce the BE observed for

11.

The relative amount of Pdᵟ

+ also revealed different for samples (

Table S6). In unmodified

Pd-PPh3/TiO2, a value of 12.5% was measured. When the aminophosphonic acid was used in the synthesis of

15, the proportion of Pdᵟ

+ was 21.9%. These values remained similar to that of the reference

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst. However, a value as high as 64% was obtained

11 that was attributed to the oxidation of the samples during manipulations.

To conclude, these new catalysts were obtained by deposition of organosilane and organophosphonic acid modifiers over previously synthesized Pd NPs supported on TiO2. When organosilanes were employed as modifiers, smaller Pd NPs were obtained compared with those modified by organophosphonic acids. Using APTES at different concentrations, the use of higher amount of APTES led to lower Pd contents, which was attributed to Pd leaching.

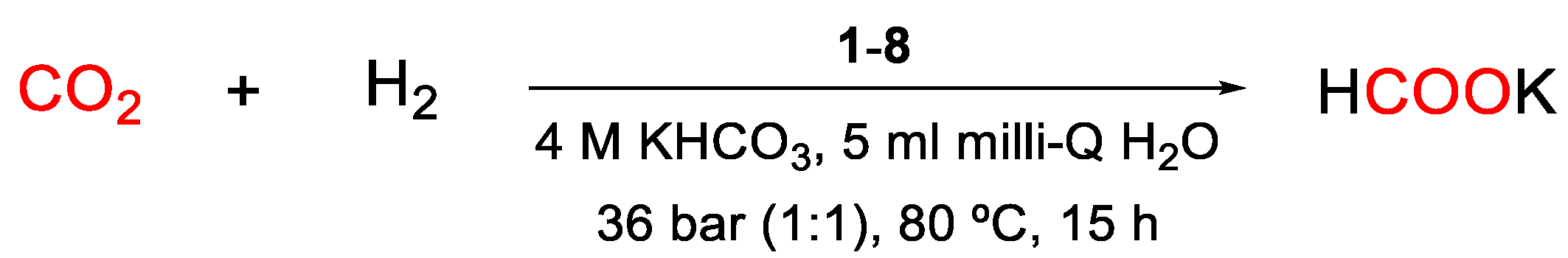

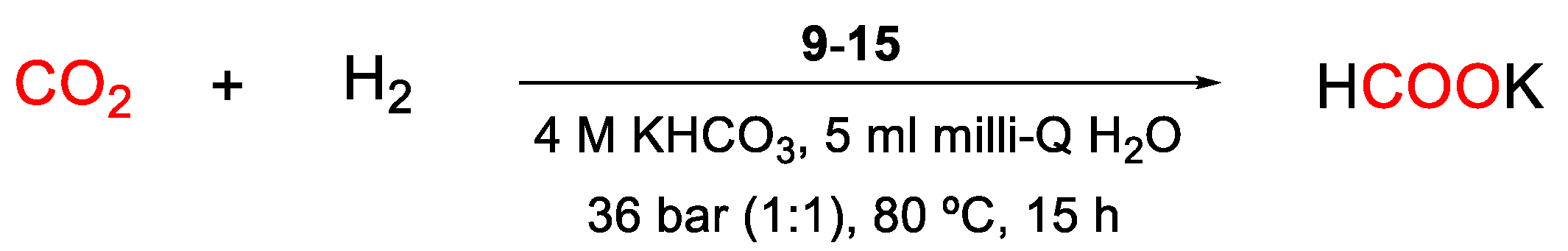

2.3. Hydrogenation of CO2 into Formates Using Modified Catalysts

First, a screening was performed to evaluate the effect of the different modifications carried out on catalysts. These tests were performed at 80 ºC using 36 bar of CO2/H2 (1:1) pressure during 15 h in the presence of KHCO3 as a base and using water as solvent. The results obtained using the Pd-PPh3/modifier@TiO2 1-8 and modifier@Pd-PPh3/@TiO2 9-15 catalysts are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

2.3.1. Hydrogenation of CO2 into Formates Using Catalysts Formed by Deposition of Pd NPs over Modified TiO2 Supports

In

Table 2, the results obtained with systems

1-8 are displayed and compared with those provided by the unmodified

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst (TON of 881, Entry 1) under the same conditions [

39]. When

2 was used as catalyst, a TON of 1057 was reached (Entry 3) whereas using material

8, modified by organophosphonic acid (Entry 11), a decrease in activity was observed and the lowest TON value of the series was measured (694). These results therefore indicated that when the catalyst is formed by deposition of the Pd NPs over the modified support, the nature of the modifier affects the catalyst activity.

Next, the effect of the reaction conditions used for the support modification using APTES was investigated. The results obtained show 3 distinct effects compared with the unmodified catalyst (Entry 1). When low concentration of APTES (0.01 M, 0.003 mmol/mg TiO

2) was used to modify the support, a positive effect on the activity of the resulting catalyst

2 was observed (Entry 3). When the concentration of APTES was increased up to 0.1 M (up to 0.013 mmol/mg TiO

2) (catalyst

3a, (Entry 4), the TON obtained was similar to that obtained with the unmodified catalyst (868), suggesting that the excess of APTES “cancelled out” the positive effect observed at lower concentrations. These results are in contrast with those reported by Mori et al. [

24] using a phenylamine containing organosilane to modify SiO

2, since they observed an increase in catalytic activity when the amount of phenylamine was increased.

Next, the effect of the functional group at the end of the alkyl chain of the modifier was evaluated. For the catalysts formed by modifications with organosilanes, the presence of a functional group (either NH2 or imidazolium group) was clearly beneficial to the catalyst activity since an increase in TON was observed from 588 (for PTES, Entry 2) to ca. 850 for APTES and IL-OAc modified catalysts (Entries 4 and 8). Similar effect was observed for PAs-modified catalysts (Entry 10 vs. 11), although to a lesser extent (635 vs. 694).

For the Pd NPs over TiO2 previously modified by organosilanes containing an IL functionality, the highest TON was obtained with the catalyst 5 (1030, Entry 7).

Based on previous results using organosilane modifiers (

Table 2), the concentration could be the parameter responsible of this difference. This was confirmed by the results obtained with the catalysts

5 and

6a which only differ by the concentrations used during their support synthesis (Entry 7 vs. Entry 8). Indeed, the catalyst

5 containing the support modified at the lower concentration provided a TON of 1030 while when

6a was used, a TON of 776 was obtained. These results were therefore in agreement with the trend previously observed.

The presence of PPh

3 ligand during the synthesis of the Pd NPs over supports modfied with APTES and IL-OAc was evaluated (

Table 2). In both cases, slightly higher TON values were obtained in the absence of PPh

3 (Entry 4 vs. Entry 5 and Entry 8 vs. Entry 9). When

3a was used, a TON of 868 was obtained (Entry 4), while the system without PPh

3,

3b provided a TON of 917 (Entry 5). IL-OAc,

6a, which was synthesized in the presence of PPh

3, reached a TON of 776 (Entry 8) while its analogue without PPh

3,

6b, yielded a TON of 826 (Entry 9).

These catalytic results therefore show that the modification of the TiO2 support by oganosilanes provided a beneficial effect compared with the catalyst containing unmodified TiO2 or TiO2 modified by organophosphonic acids. Moreover, the modifier concentration is a key parameter during the support modification and lower values provide catalysts with higher activities. The presence of a functional group (either NH2 or imidazolium) in the modifiers also improved the activity of the catalysts compared with those containing a simple alkyl chain.

2.3.2. Hydrogenation of CO2 into Formates Using Catalysts Formed by Modifications of Pre-Synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2

The catalysts synthesized by the deposition of the modifier over

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 previously synthesized were evaluated in the CO

2 hydrogenation into formate (

Table 3).

When the results obtained by deposition of organosilane and organophosphonic acid under the same conditions (same concentration, mmol modifier/mg TiO2 ratio and amine substituent on the organosilane and organophosphonic acid) were compared, the system containing a Si as anchoring atom, 10, provided a TON of 581 (Entry 3) whereas when APA was used as modifier, the 15, a TON of 844 was reached (Entry 8).

As the unmodified catalyst provided a TON of 881, it was concluded that the deposition of the organosilane over the presynthesised catalyst had a detrimental effect on the CO2 hydrogenation while the deposition of PA has no significant effect. These results are in contrast with those obtained using the catalyst where Pd NPs were deposited over the modified support and highlight the importance of the synthetic strategy when such catalysts are modified with organic molecules.

The results obtained for hydrogenation of CO

2 to formate using catalysts formed by deposition of APTES at different concentrations are also summarized in

Table 3. As previously mentioned, the system

10 obtained at low concentration (0.01 M of APTES, 0.003 mmol/mg TiO

2), the TON obtained was 581. However, when the same modififer was deposited using a 0.13 M solution, the resulting catalyst

11 provided much higher activity with TONs of 992 (Entry 4).

The performance of catalysts modified by organosilanes containing a propyl, a propylamine or a propyl-imidalozium groups and those modified by PAs containing a butyl and a propylamine substituent were also evaluated (

Table 3). Interestingly, all these catalysts exhibited activities similar to that of the unmodified catalyst, except that modified by an organosilane containing an imidazolium function. It is noteworthy that, as described in the previous section, the catalyst

11 showed a slight positive effect compared to the reference catalyst (Entry 4 vs. Entry 1). The results described here are in clear contrast with those obtained when the support was first modified prior to the deposition of Pd NPs, for which the presence of a functional group (either amine or imidazolium) in the modifier clearly improved the performance of the resulting catalysts. This might be due to the beneficial effect of this group in the anchoring of the NPs when present at the support surface prior to the NP deposition while such a group does not influence the catalytic activity when deposited after NP formation. This thus suggests that the presence of this group does not influence the catalysis but only the preparation of the catalyst.

The catalytic performance of the catalysts

12 and

13, modified by ionic liquid-containing modifiers with distinct anions, are summarized

Table 3. The 2 catalysts tested provided lower TONs (388 and 551, Entry 5 and 6, respectively) than the unmodified catalyst, indicating that the deposition of IL-containing organosilanes over the Pd NPs was detrimental to the catalytic performance of the

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 material.

These catalytic results therefore show that the deposition of organosilane and organophosphonic acid modifiers over previously synthesized Pd NPs supported on TiO2 was not beneficial, in most cases, to the activity of the resulting catalysts.

2.3.3. Reusability Tests

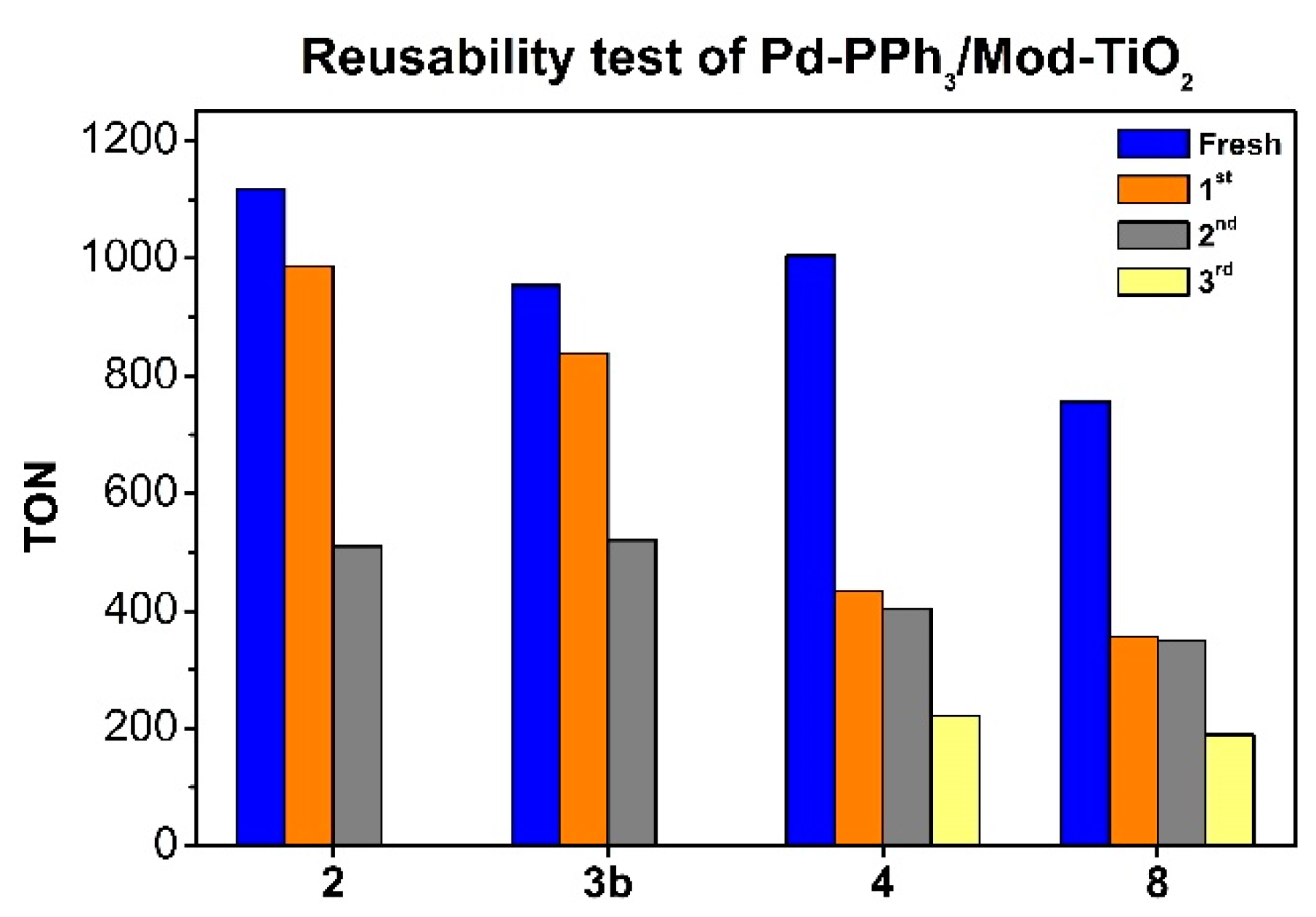

After evaluating the activity of the newly synthesized catalysts, recyclability tests were performed using the most active systems. During these experiments, the catalysts were recovered by filtration over a Nylon membrane after each cycle, washed several times with milli-Q H2O and dry under vacuum for several hours prior to their reuse.

Initially, the catalysts

2,

3b,

4 and

8 were employed to evaluate the effect of the modifiers on the reusability of the materials performing the hydrogenation reactions at 80 ºC. The results obtained for are summarized in

Figure 4. In all cases, a strong decrease in activity was observed after 2 cycles. However, the catalysts

2 and

3b containing the support previously modified by APTES suffered a minimal loss of activity during the first cycle and a large decrease during the 2nd cycle. In contrast, the catalysts

4 and

8 containing the support modified by NH

2-PA and an organosilane containing an imidazolium group suffered a large loss of activity during the 1st recycling but maintained their activity during the 2nd recycling. After the 3rd recycling, a new drop in activity for these catalysts was observed. TEM analysis of the spent catalysts revealed large agglomerations in all samples while no dramatic changes in mean size were measured on non-agglomerated Pd NPs (

Figures S40, S41, S43, and S44).

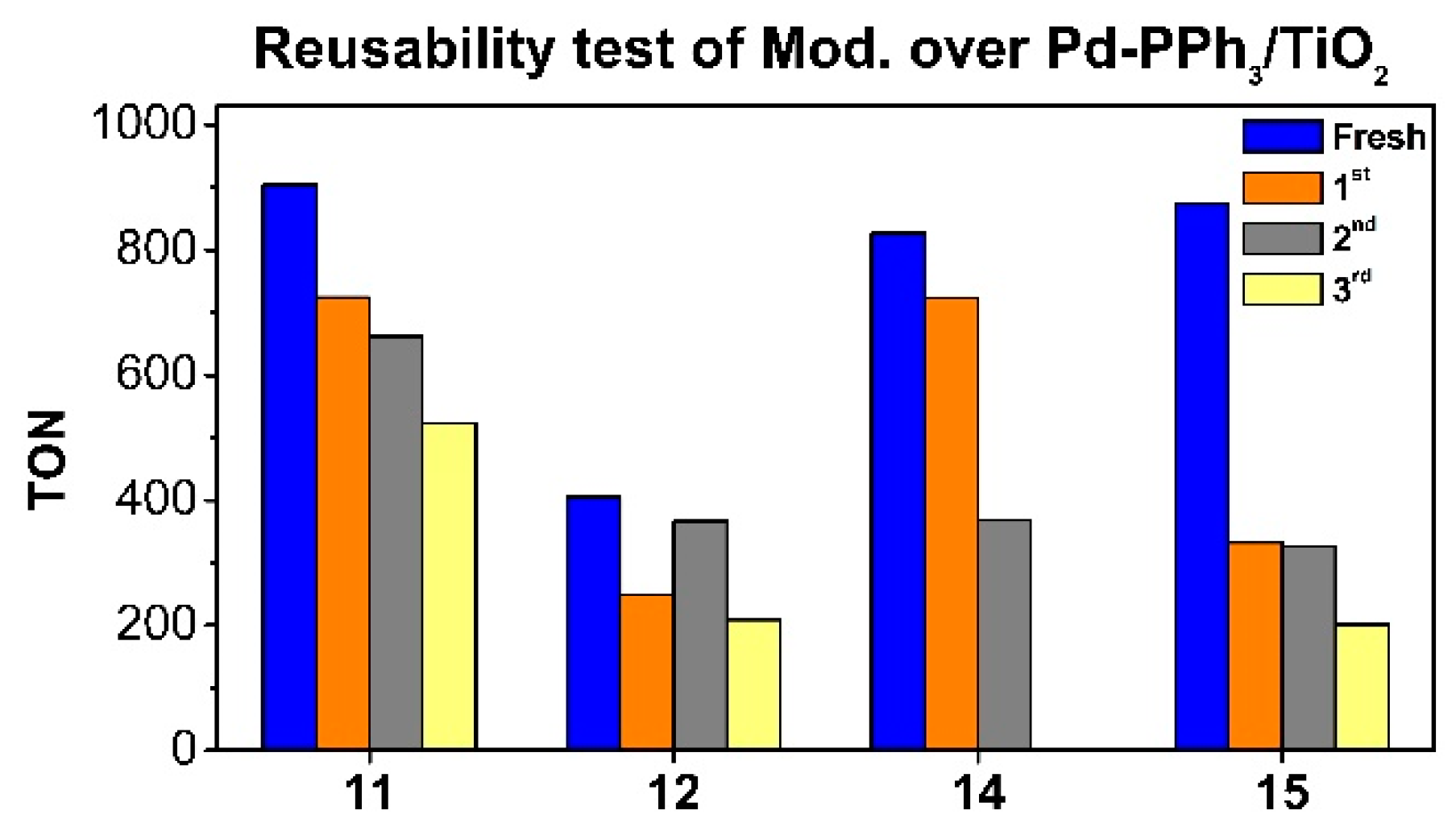

Next, recyclability experiments were performed using the catalysts

11,

12,

14 and

15 under the same conditions (

Figure 5).

11 was the most active system of this series with an initial TON of 904. This catalyst provided a TON of 724 after the 1st recycling, 662 after the 2nd recycling and 524 after the 3rd recycling.

For the catalysts in which deposition of an organophosphonic acid was performed over the previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2, distinct behaviors were observed depending on the functional groups contained in the modifiers. For 15, containing an PA with an amine function, a drastic decrease in activity was observed during the first recycling, with a drop of TON value from 873 to 332. No relevant decrease in activity was observed during the 2nd recycling while a drop of TON to 201 was measured for the 3rd recycling. In contrast, when the catalyst contained a PA modifier with a butyl chain 14, the activity loss during the first recycling was less pronounced (from a TON of 827 to 723) while a sudden drop to 369 was observed during the 2nd recycling. For the catalyst 12 modified by an organosilane containing an imidazolium group, much lower activities were measured (TONs in the range 405 initially to 209 after 3 runs).

TEM analysis of the spent catalysts after 2 recyclings (

Figure S45) revealed that the mean sizes of the Pd NPs in these materials was in all cases in the range 3.5-4 nm (

Table S19) and different degrees of agglomeration were observed. In the case of catalyst

12, for which an increase in Pd NPs mean size from 2.4 nm to ca. 4 nm was observed, the presence of agglomerations was pronounced. For the catalysts modified with PAs

14 and

15, no large variation in size was observed but large agglomerations were detected.

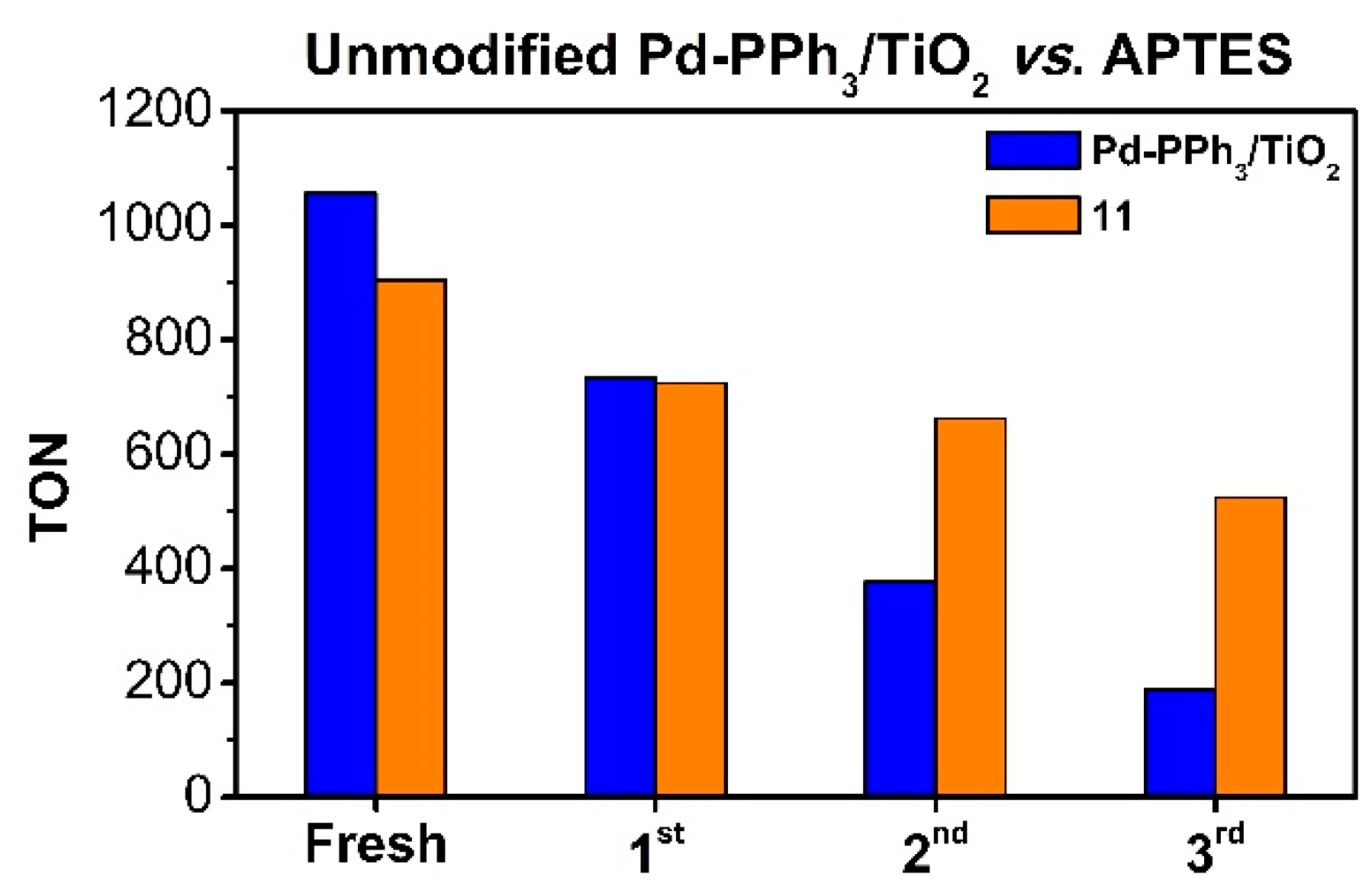

These recycling experiments therefore show that the synthetic procedure used for the modification of the

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst affects the reusability of these materials in the CO

2 hydrogenation into formate. Indeed, the catalysts formed by modification of the support prior to Pd NP deposition suffer a rapid decrease in activity during their recycling and reuse in spite of the initial beneficial effect. In contrast, some of the materials where the modifiers were deposited over the previously anchored Pd NPs onto TiO

2 show a much more gradual decrease in activity and reached a TON > 500 after the 3rd recycling. To evidence the improvement in reusability obtained by catalyst modification in this work, the TON values obtained with the unmodified catalyst

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 during the recycling experiments are compared with those of

11 in

Figure 6. Despite a superior initial activity of the unmodified catalyst, both materials exhibited similar TON values after the 1st recycling and in the 2nd and 3rd recyclings, the modified catalyst clearly showed a better performance.

Important differences were observed by TEM analyses of the spent catalysts since for

11, an increasing of size from 1.86 ± 0.69 nm to 3.53 ± 1.23 nm was measured after two cycles, but only a few agglomerations were observed. In contrast, the Pd NPs in

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 were largely agglomerated after the recyclings and exhibited a mean size of ca. 5 nm. These results thus suggest that the presence of APTES provided additional stabilization and limited the degree of agglomerations of the Pd NPs. This is in agreement with the results reported by Liu et al. who described that the coverage of Au NPs with APTES improved their recovery [

22].

3. Materials and Methods

Pd(dba)2, PPh3, TiO2 (Titanium (IV) oxide nanopowder, 21 nm primary particle size (TEM), ≥ 99.5% trace metals basis, rutile-anatase mixture, specific surface area 35-65 m2/g) and the rest of compounds employed for modification were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any further purification. All solvents were dried from a solvent purification system (SPS) and deoxygenated. Tetrahydrofuran was further dried by refluxing in the presence of sodium/acetophenone. Milli-Q water was employed in catalytic experiments. Any other solvent or reagent employed was reagent grade. Hydrogen (5.0) was purchased from Carburos Metálicos and CO2 (5.3) was purchased from Abelló Linde. All the synthesis were performed using Schlenk techniques under Argon and glovebox using nitrogen as inert gas. The synthesis of nanoparticles were carried in Fischer-Porter bottles and catalytic tests were performed in a stainless steel high-pressure reactor Hel CAT-7 (7 x 10 ml). Characterization techniques that were employed: TEM, HR-TEM, ESEM, FESEM, ICP-OES, TGA, NMR, FT-IR and XPS. All details and corresponding figures could be found in the supporting information.

3.1. Modification of TiO2 with n-Propyltriethoxysilane (PTES) and (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)

In a general synthesis of TiO2-1-3, a solution (mixture EtOH:milli-Q H2O 95:5 v/v), of the accorded concentration of PTES or APTES were prepared into a Schlenk (under Ar). Then, the corresponding amount of TiO2 (mmol (A)PTES/mg TiO2) was added to the solution under vigorous stirring. Reaction was stirred at room temperature overnight. Then, the mixture was centrifuged. Supernatant was removed and the solid was washed several times with milli-Q H2O and EtOH and was dried at 80 ºC under vacuum for several hours.

3.2. Modification of TiO2 with Ionic Liquids (ILs)

First, synthesis of the ILs were performed according to the literature with some variations [

43,

44,

45,

46]. The synthesis of

TiO2-4 was performed according to reported procedures [

47]. A suspension of 2 g of TiO

2 in 80 ml of milli-Q H

2O was added to a previously prepared solution of 659.08 mg (1.8 mmol) of IL-Cl in 2 ml of milli-Q H

2O. Mixture was stirred at 80 ºC for 12 h. After reaction, the mixture was centrifuged and washed twice with milli-Q and once with EtOH. After that, it was dried under vacuum at 60 ºC.

For the ILs with AcO- (TiO2-5 and TiO2-6) as anion TiO2 was added to a solution of IL-OAc (mixture EtOH:milli-Q H2O 95:5 v/v) and the mixture was heated at 80 ºC overnight. The product was washed with EtOH several times and dried under vacuum at 60 ºC.

3.3. Modification of TiO2 with Phosphonic Acids (PAs)

The modification of TiO

2 with PAs (

TiO2-7 and

TiO2-8) was performed according to literature procedures with some variations [

48,

49,

50]. Solutions contained 83.35 µmol of modifier per each square meter of TiO

2 nanopowder which corresponded approximately to a 10-fold excess in respect to build a monolayer in the surface of support.

Solution 10 mM of 3-aminopropylphosphonic acid (APA) (

TiO2-8), (1.46 mmol, 202.84 mg) in 146 ml of milli-Q H

2O was prepared. Then, 0.5 g of TiO

2 was added and the mixture was stirred at r.t. overnight. After this time, the suspension was centrifuged, washed with abundant milli-Q water, EtOH and acetone. The solid was dried at 120 ºC in an oven. It is necessary to produce condensation reactions to give strong bonds between PAs and metal oxide [

51]. So, in this case, after the reaction, the solid was separated by centrifugation, the solvent was removed and solid was placed into an oven at 100 ºC overnight. After that, the solid was aged into a Quartz furnace at 120 ºC under air flow during 6 h. Then, it was washed with abundant milli-Q water and centrifuged every time (5 times). The solid was dried overnight at 100 ºC. When butylphosphonic acid was employed (PA) (

TiO2-7), the synthesis was performed under the same conditions. The only difference was that THF was used as reaction media and for washing and centrifugation.

3.4. Synthesis of Pd NPs with PPh3 as Ligand over Different Modified TiO2 Supports through Organometallic Approach (1-8)

The catalysts were prepared following a previously reported methodology [

39]. To obtain a 4 wt% theorical content of Pd over TiO

2. In a common experiment, metal precursor (Pd(dba)

2), 0.2 eq. of stabilizer (PPh

3) and modified TiO

2 were weighted in the glove box and charged in a Fischer-Porter bottle. Then, solvent (THF) was added, the Fischer-Porter was closed, purged with hydrogen several times and then charged with 3 bar of H

2. The mixture was then heated at 60 ºC and stirred at 700 rpm overnight. After the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and degassed. Samples for TEM analysis were prepared by deposition of several drops of the reaction crude onto a copper grid. The rest of the reaction crude was concentrated and washed several times with abundant hexane. The catalyst was dried under vacuum during several hours.

3.5. Deposition of Modifier over Previously Synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 Systems (9-15)

PTES and APTES (9-11): Specified concentration of PTES or APTES (and determined mmol (A)PTES/mg: Pd-PPh3/TiO2 ratio) and Pd-PPh3/TiO2 previously synthesized were mixed. At r.t., the synthesis was carried out overnight in Schlenk using a mixture of 95% EtOH, 5% milli-Q H2O, while reactions at 120 ºC reaction were performed in an autoclave during 4 h using EtOH as solvent. In both cases, samples were dried overnight in an oven at 105 ºC and stored inside the glove box.

ILs (12-13): Mixture of a specified concentration of IL-Anion and previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 system was prepared at r.t. using a mixture of 95% EtOH, 5% milli-Q H2O, overnight.

PAs (14-15): Mixture of a specified concentration of PAs and previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 system were mixed at r.t. using milli-Q H2O as solvent (for synthesis with APA) or THF (for synthesis with PA), overnight.

3.6. Catalytic Experiments for CO2 Reduction to Formate

Stainless steel high-pressure reactor HEL CAT-7 (7 x 10 ml) was charged with TiO2 supported palladium nanoparticles (20 mg), 20 mg of 1,4-dioxane and 5 ml of a 4 M base solution employing milli-Q water. The reactor was first flushed with 3 cycles of hydrogen to remove the air. Then, the reactor was charged with 10 bar of H2 and heated at 40 ºC under stirring for twenty minutes. At this point, the reactor was depressurized, purged several times with CO2 and charged with 18 bar of CO2 and let under stirring for 20 minutes. Then, the reactor was charged with 18 bar of H2 (1:1, CO2:H2) and heated to reach the temperature under 600 rpm of stirring. The experiment was left 15 h and after this time, the reactor was allowed to cool in an ice bath. When the reactor was cooled, it was depressurized and opened. A small amount of the sample was centrifuged and 100 µl of supernatant were analysed by NMR using D2O as deuterated solvent.

3.7. Recycling Experiments

After every catalytic experiment, the mixture was filtered through a Nylon membrane. The solid was washed several times with abundant milli-Q H2O and dried under vacuum for several hours. At this point, the solid was reused in an identical catalytic experiment.

4. Conclusions

A series of supported Pd-NPs based materials were successfully synthesized using modifiers of different nature (organosilanes, ILs and PAs) following two distinct approaches. The so-called reverse deposition approach requires in the first place to modify the TiO2 support prior to Pd NPs deposition while the 2nd approach was the modification of a pre-synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 by deposition of the modifier over its surface. The newly prepared materials, including the modified TiO2 supports, were characterized by various techniques such as TEM, HRTEM, EDS, FT-IR, TGA, ICP etc.

These catalysts were tested in the hydrogenation of CO2 to formate, and their performance compared with those of the unmodified catalyst Pd-PPh3/TiO2. The modification of the TiO2 support by oganosilanes provided a beneficial effect in catalysis compared with the catalyst containing unmodified TiO2 or TiO2 modified by organophosphonic acids and the modifier concentration is a key parameter during the support modification.

The presence of a functional group (either NH2 or imidazolium) in the modifiers improved the activity of the catalysts. In contrast, the deposition of organosilane and organophosphonic acid modifiers over previously synthesized Pd NPs supported on TiO2 was not beneficial, in most cases, to the activity of the catalyst.

The synthetic procedure used for the modification of the Pd-PPh3/TiO2 catalyst also affected the reusability of these materials in the CO2 hydrogenation into formate and when the modifiers were deposited over the previously anchored Pd NPs onto TiO2, a more gradual decrease in activity was observed.

Scheme 1.

Modifications of catalyst surface for hydrogenation of CO2 to formates in basic media.

Scheme 1.

Modifications of catalyst surface for hydrogenation of CO2 to formates in basic media.

Figure 1.

Modifying agents used for TiO2 modification.

Figure 1.

Modifying agents used for TiO2 modification.

Scheme 2.

Deposition of modifier on a support prior to metal catalyst formation (reverse deposition) (a) and deposition of modifier on a previously synthesized supported metal catalyst (b).

Scheme 2.

Deposition of modifier on a support prior to metal catalyst formation (reverse deposition) (a) and deposition of modifier on a previously synthesized supported metal catalyst (b).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of nanoparticles stabilized with PPh3 supported over modified-TiO2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of nanoparticles stabilized with PPh3 supported over modified-TiO2.

Figure 2.

TEM images and size distributions of Pd-NPs synthesized over modified TiO2 supports. Deposition of TESs and PAs modifiers over previously synthesized Pd-PPh3 supported over TiO2. 1 (a), 2 (b), 3a (c), 3b (d), 4 (e), 5 (f), 6a (g), 6b (h), 7 (i), 8 (j).

Figure 2.

TEM images and size distributions of Pd-NPs synthesized over modified TiO2 supports. Deposition of TESs and PAs modifiers over previously synthesized Pd-PPh3 supported over TiO2. 1 (a), 2 (b), 3a (c), 3b (d), 4 (e), 5 (f), 6a (g), 6b (h), 7 (i), 8 (j).

Scheme 4.

Deposition of TESs and PAs modifiers over previously synthesized Pd-PPh3 supported over TiO2.

Scheme 4.

Deposition of TESs and PAs modifiers over previously synthesized Pd-PPh3 supported over TiO2.

Figure 3.

HR-TEM image of the catalyst 11.

Figure 3.

HR-TEM image of the catalyst 11.

Figure 4.

Recycling experiments with catalysts 2, 3b, 4 and 8 in CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalyst, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 80 ºC, 15 h. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Figure 4.

Recycling experiments with catalysts 2, 3b, 4 and 8 in CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalyst, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 80 ºC, 15 h. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Figure 5.

Recycling experiments with the systems 11, 12, 14 and 15 in the CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalyst, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 80 ºC, 15 h. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Figure 5.

Recycling experiments with the systems 11, 12, 14 and 15 in the CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalyst, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 80 ºC, 15 h. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Figure 6.

Comparation of recycling experiments with 11 and Pd-PPh3/TiO2 for CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalysts, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 15 h. Temperatures employed for 11 and Pd-PPh3/TiO2 were 80 and 60 ºC, respectively. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Figure 6.

Comparation of recycling experiments with 11 and Pd-PPh3/TiO2 for CO2 hydrogenation to formate. Conditions: 20 mg of catalysts, 4 M KHCO3, 5 ml milli-Q H2O, pTotal= 36 bar, p(CO2) = p(H2), 15 h. Temperatures employed for 11 and Pd-PPh3/TiO2 were 80 and 60 ºC, respectively. TON= mmol formate/mmol total of Pd, calculated by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as internal standard.

Table 1.

Characterization data for the deposition of TESs and PAs over the previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 system.1.

Table 1.

Characterization data for the deposition of TESs and PAs over the previously synthesized Pd-PPh3/TiO2 system.1.

| Entry |

System |

Size (nm)2

|

Pd wt%3

|

P wt%3

|

| 1 |

9 |

2.65 ± 0.80 |

3.38 |

- |

| 2 |

10 |

2.69 ± 0.92 |

3.04 |

0.21 |

| 3 |

11 |

1.86 ± 0.69 |

2.57 |

- |

| 4 |

12 |

2.38 ± 0.95 |

1.81 |

- |

| 5 |

13 |

1.87 ± 0.61 |

2.98 |

- |

| 64

|

14 |

4.45 ± 1.68 |

3.10 |

0.82 |

| 75

|

15 |

3.00 ± 1.14 |

3.15 |

- |

Table 2.

Catalytic activity of Pd-PPh3/modifier@TiO2 1-8 with different anchor atoms for CO2 hydrogenation to formate.1.

Table 2.

Catalytic activity of Pd-PPh3/modifier@TiO2 1-8 with different anchor atoms for CO2 hydrogenation to formate.1.

| Entry |

Catalyst |

TON2

|

| 1 |

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 |

881 |

| 2 |

1 |

588 |

| 3 |

2 |

1057 |

| 4 |

3a |

868 |

| 53

|

3b |

917 |

| 6 |

4 |

1043 |

| 7 |

5 |

1030 |

| 8 |

6a |

776 |

| 93

|

6b |

826 |

| 10 |

7 |

635 |

| 11 |

8 |

694 |

Table 3.

Catalytic activity of modifier@Pd-PPh3/TiO2 9-15 with different anchor atoms for CO2 hydrogenation to formate.1.

Table 3.

Catalytic activity of modifier@Pd-PPh3/TiO2 9-15 with different anchor atoms for CO2 hydrogenation to formate.1.

| Entry |

System |

TON2

|

| 1 |

Pd-PPh3/TiO2 |

881 |

| 2 |

9 |

862 |

| 3 |

10 |

581 |

| 4 |

11 |

992 |

| 5 |

12 |

388 |

| 6 |

13 |

551 |

| 7 |

14 |

912 |

| 8 |

15 |

844 |