1. Introduction

Heterogeneous catalysts are widely used in various industrial catalytic processes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Their advantages include mechanical strength, thermal and chemical stability, ease of recycling, and separation from reaction mixtures [

2,

4]. However, a significant disadvantage of heterogeneous catalysts is lower selectivity compared to homogeneous systems. This limitation has prompted researchers to develop new catalytic materials that combine the desired properties of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts [

7]. In this context, the selection of a suitable support material plays a critical role in determining the catalyst's overall performance and efficiency. Typically, metal oxides, aluminosilicates, carbon are widely used as a solid support for metal catalysts due to their high thermochemical stability [

2,

8,

9]. There are many studies on the use of polymers as supports for metal particles [

3,

9,

10,

11]. One of the main problems of using polymers as supports in catalytic systems is their low specific surface area, which limits the availability of active centers and, consequently, the efficiency of catalysis. To solve this problem, hybrid supports combining the structural advantages of mineral materials and the functionality of polymers are used.

Fixation of metal complexes with macromolecular ligands on inorganic supports is the focus of attention as a promising approach to the creation of heterogeneous catalysts with embedded metal nanoparticles [

12,

13,

14]. Wissing et al. [

15] developed Au and Pd nanoparticles (NPs) on zeolite L crystals decorated with photoactive polymer brushes. The role of the polymer is to reduce metal salts to the corresponding metallic NPs by releasing highly reductive ketyl radicals upon UV light irradiation, stabilizing the in situ formed metallic NPs and preventing their aggregation. Zeolite-polymer NPs were investigated in the stereoselective semi-hydrogenation of alkynes to Z-alkenes and oxidation of benzyl alcohols to aldehydes. Zhao et al. [

16] employed chitosan (CS) and montmorillonite (Mt)-based composites, modified with either Al or Al–Fe, as supports for immobilizing Pd⁰ nanoparticles. Chitosan and Pd⁰ nanoparticles were incorporated into the interlayer spaces of the pillared Mt. The developed catalysts (Pd

0@CS/Al-Mt and Pd

0@CS/Al-Fe-Mt) showed high catalytic efficiency and stability in Sonogashira coupling reactions. Almost 100% yield was obtained in the Sonogashira reaction of iodobenzene with phenylacetylene at 0.16 mol% Pd loading for only 1 h. Nagarjuna et al. [

17] synthesized a palladium catalyst using functionalization of polyethyleneimine (PEI) on alumina followed by adsorption of palladium. XPS analysis of the developed catalysts (Pd-PEI-AO and rPd-PEI-AO) showed favorable interaction of PdCl

42– with PEI nitrogen molecules. The catalysts were successfully tested in the catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol and hydrogen generation from ammonia borane. Earlier, Rakap et al. [

18] investigated the preparation and catalytic properties of polyvinyl butyral-immobilized palladium catalyst deposited on TiO

2 (Pd-PVB-TiO

2) in the hydrolysis of unstimulated ammonia-borane solution for hydrogen production. Maximum hydrogen generation rates of ∼642 mL H

2 min

–1 (g Pd)

–1 and ∼4367 mL H

2 min

–1 (g Pd)

–1 were observed during hydrolysis at 25 °C and 55 ± 0.5 °C, respectively. Szubiakiewicz et al. [

19] reported that modification of silica with polyvinylpyrrolidone followed by loading of palladium catalyst improved the formation of the target product (tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol) in the hydrogenation of furfural. It was shown that PVP promotes stabilization of Pd particles and prevents their agglomeration on the catalyst surface. Antonetti et al. [

20] developed a polyketone-SiO

2 (PK/SiO

2) composite for use as a support for Pd catalysts. The synthesized catalysts were tested in the selective hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde to hydrocinnamaldehyde in decalin and the oxidation of 1-phenylethanol to acetophenone in water. Pd/PK and Pd/SiO

2 were also prepared for comparison. The Pd nanoparticles supported on the hybrid composite exhibited significantly smaller sizes and a more uniform size distribution compared to those supported on conventional SiO₂ or PK. The PK/SiO

2-based palladium catalysts demonstrated higher activity and stability. The authors attribute this to the improved surface area of the hybrid composite and the stabilizing effect of the polymer. Ródenas et al. [

21] developed UVM-7/polydopamine (PDA)-based Pd⁰ nanoparticle catalysts supported on porous silica for the hydrogenation of 4-nitrophenol. The catalysts demonstrated higher efficiency compared to analogous systems lacking PDA.

In our previous works, we described a one-pot method for the synthesis of applied polymer-metal catalysts from aqueous solutions of polymers and metals. The method of preparation of such catalysts excludes the stages of high-temperature calcination and reduction [

12,

13,

22,

23].

The aim of the present work was to determine the effect of a polymer-modified and support on catalytic properties of palladium catalysts. Poly(4-vinylpyridine) (P4VP) and chitosan (CS) were used as the polymer-modifier. The polymer-metal complexes were deposited on solid supports (MgO, SBA-15). The obtained results were confirmed by IRS, TEM, XPS, SEM, EDX methods. The reaction behavior of hybrid catalysts has been studied in the low-temperature hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol, phenylacetylene and 2-hexyne-1-ol.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Pd Catalysts Deposited on Polymer-Modified Supports

The palladium catalysts supported on polymer-modified supports were prepared by adsorption method.

Table 1 summarizes the results of Pd

2+ ions adsorption on MgO and silica (SBA-15), modified with poly(4-vinylpyridine) (P4VP) and chitosan (CS). The palladium content in the catalysts was estimated based on the change in the concentration of Pd²⁺ ions in the mother liquor before and after immobilization. The concentration of palladium in the solution was determined using photoelectric colorimetry (PEC). According to PEC data, palladium was almost completely adsorbed onto the surface of the supports. The calculated palladium content based on PEC measurements was approximately 1 wt.%, which was confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental analysis.

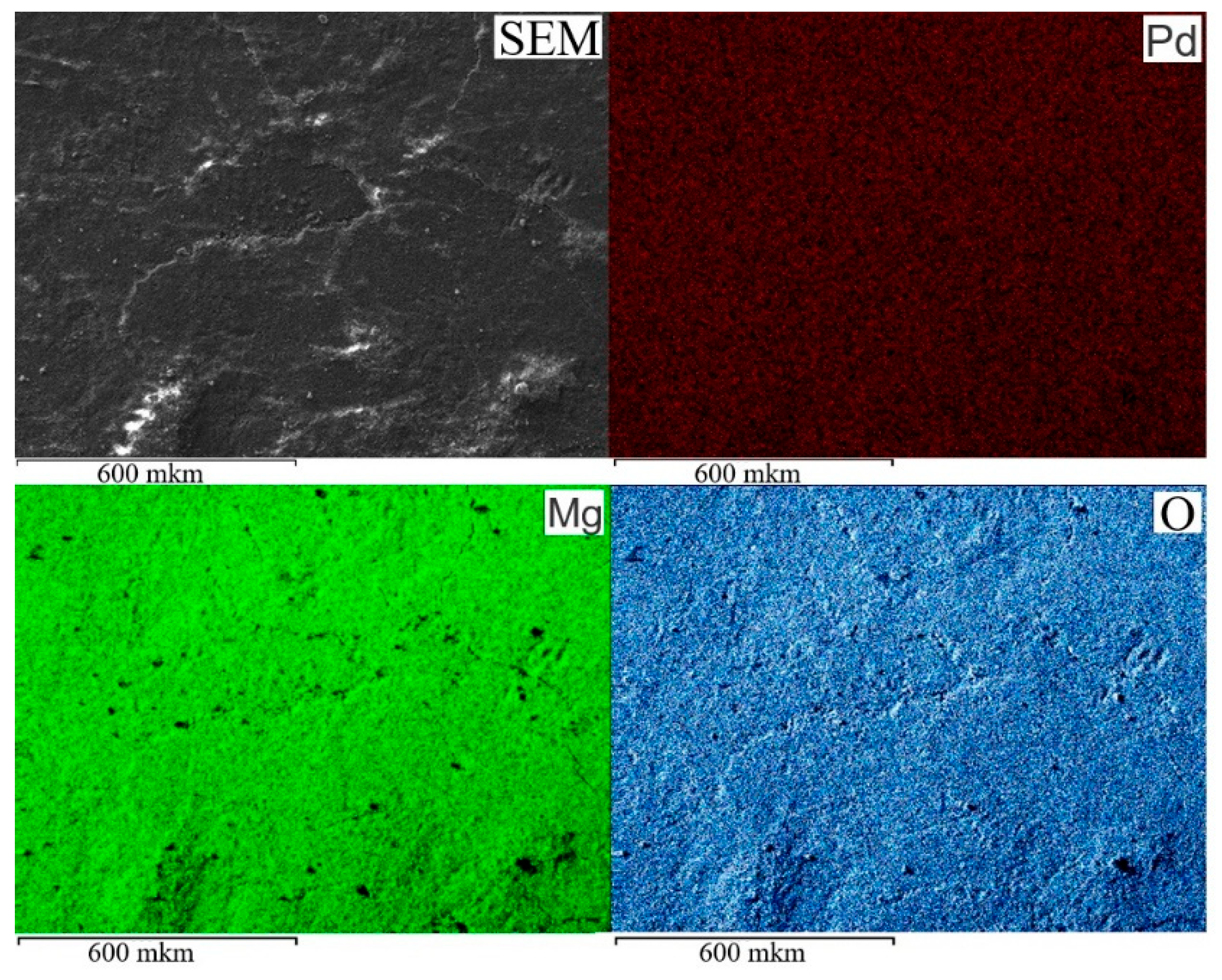

SEM and EDX elemental mapping images of Pd, Mg, and O from 1%Pd-P4VP/MgO catalyst (

Figure 1) demonstrate a uniform distribution of all elements corresponding to SEM image. This suggests that Pd is homogeneously deposited on P4VP/MgO support.

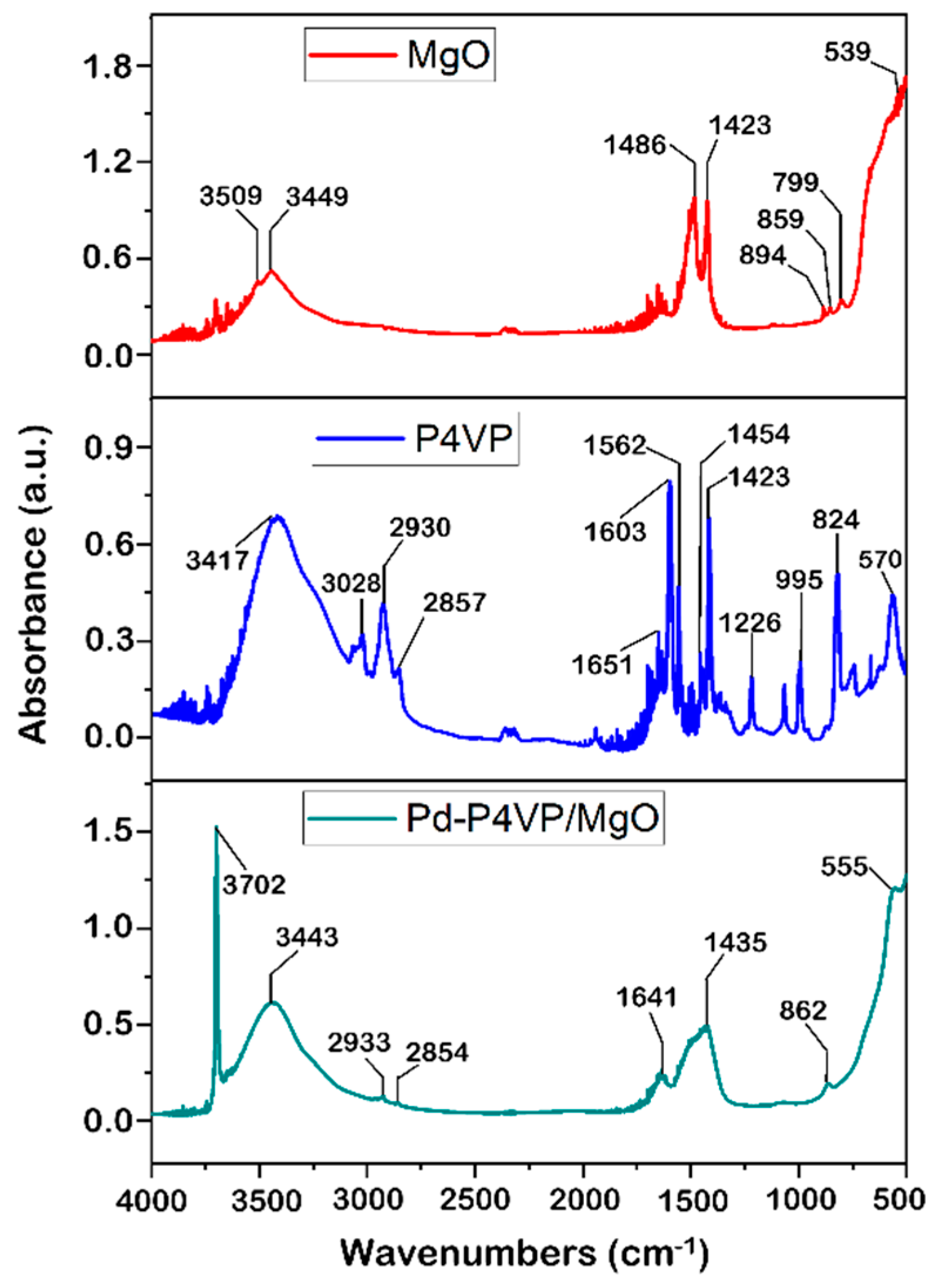

Figure 2 shows IR spectra of MgO, P4VP and 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO. The spectrum of MgO shows characteristic bands at 859 cm

–1 and 894 cm

–1 attributed to Mg–O vibrations [

24,

25]. The distinct bands observed at 1423 cm

–1 and 1486 cm

–1 are attributed to vibrations of surface hydroxyl groups [

24]. The detected broad bands at 3449 cm

–1 and 3509 cm

–1 are due to OH stretching vibrations of water molecules [

24]. In the spectrum of P4VP (

Figure 2, blue line), the C=N absorption peaks are assigned at 1603 cm

–1 and 1562 cm

–1 due

to the stretching vibration of the pyridine ring. The absorption bands at 1454 cm

–1 and 1423 cm

–1 correspond to stretching vibrations of C=C bond [

26,

27]. In the spectrum of the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO composite, the absorption bands at 2933 and 2854 cm⁻¹ are attributed to C–H stretching vibrations of the P4VP backbone, confirming the presence of the polymer. The bands observed at 1641 and 1435 cm⁻¹ can be assigned to C=N and C=C stretching vibrations of the pyridine ring, although these peaks may overlap with absorption bands of –OH groups from magnesium oxide. A distinct band at 862 cm⁻¹ is associated with Mg–O vibrations. Some overlap and shifting in the 1400–1650 cm⁻¹ region suggest possible interactions between P4VP and MgO, as well as coordination of Pd with nitrogen atoms in the pyridine ring.

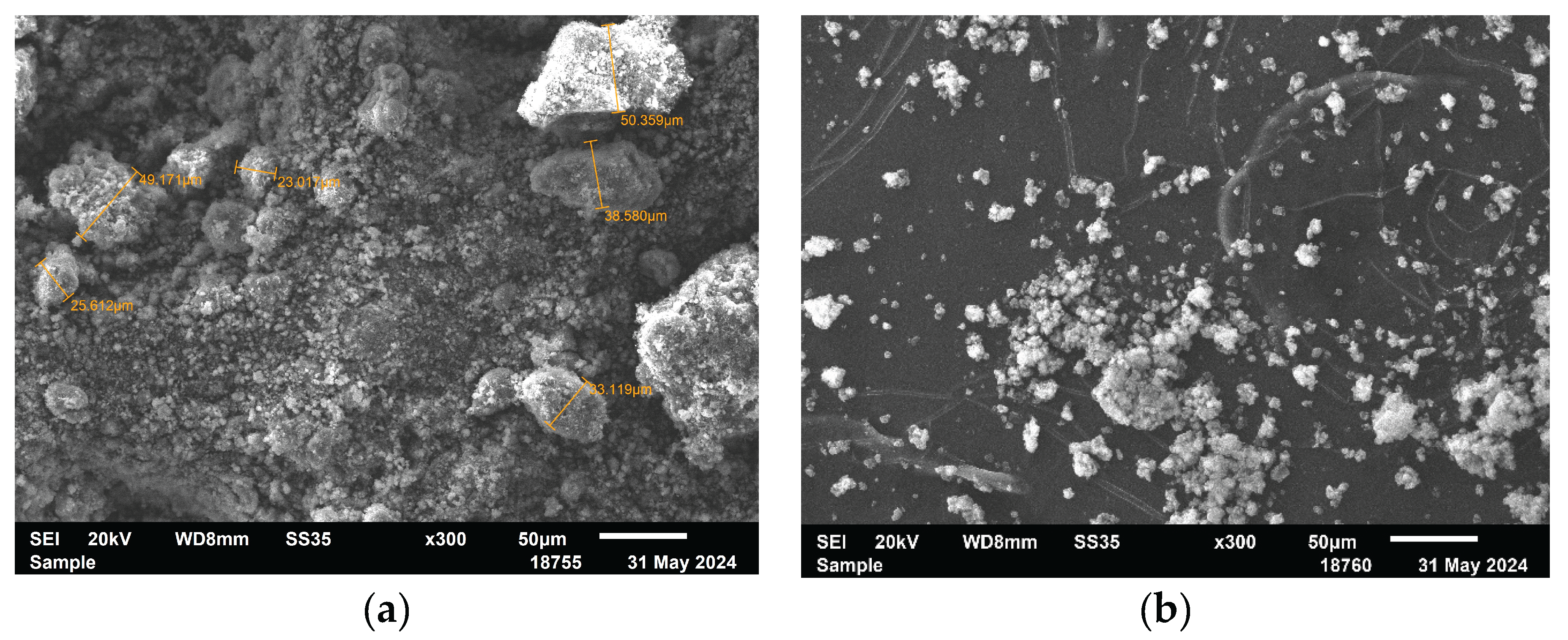

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images reveal clear morphological changes in magnesium oxide (MgO) after modification with the polymer ligand and subsequent palladium deposition. The unmodified MgO (

Figure 3a) shows a heterogeneous structure composed of both small particles and large aggregates, which appear to consist of smaller primary crystallites. In the case of the P4VP/MgO composite (

Figure 3b), smaller and more compact aggregates are observed. These aggregates also appear to be composed of fine particles; however, the boundaries between them are less distinct, and the overall morphology is smoother, indicating coverage or partial embedding by the polymer. The 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (

Figure 3c) exhibits a densely packed, fused structure, likely resulting from polymer-induced agglomeration of MgO particles in the presence of palladium ions during catalyst preparation. These morphological transformations indicate successful modification of the MgO support with both the polymer and palladium species.

TEM images of palladium catalysts immobilized on P4VP-modified MgO and SBA-15 supports are shown in

Figure 4. The TEM image of the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (

Figure 4a) shows well-dispersed Pd nanoparticles uniformly distributed over the surface of the polymer-modified support. The analysis of a TEM microphotograph of the catalyst at a higher magnification level (

Figure 4b) indicates that the Pd particles are approximately 2–3 nm in size. In contrast, the 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 catalyst exhibits significantly larger Pd particles, with sizes ranging from 8 to 10 nm (

Figure 4c,d). The image in

Figure 4c also reveals uniform pore channels arranged in parallel, which is a characteristic structural feature of the SBA-15 silica matrix [

22,

28,

29].

In order to assess the oxidation state of palladium during the hydrogenation process, the catalysts were pretreated with molecular hydrogen in a reactor at 40 °C for 30 min, followed by analysis using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Figure 5 shows the Pd 3d region of the XPS spectra for the reduced 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–CS/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15, and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 catalysts. XPS analysis of the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO and 1%Pd–CS/MgO samples is complicated by the overlap of the Pd 3d signals with the Mg KLL Auger transitions, making precise interpretation difficult [

30,

31] (

Figure 5a,b). Despite this, deconvolution of the spectra reveals a shoulder at a binding energy of ~335.2 eV, which can be attributed to metallic palladium (Pd⁰) [

32,

33].

The deconvoluted Pd 3d XPS spectrum of the reduced 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 catalyst revealed the presence of palladium in different oxidation states on the catalyst surface. Specifically, the Pd 3d₅/₂ peaks observed at 335.8 eV and 338.2 eV were assigned to metallic palladium (Pd⁰) and Pd²⁺ species, respectively [

32]. The proportion of palladium in the zero-valence state was approximately 50%. A similar Pd 3d spectrum was obtained for the reduced 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 catalyst, exhibiting nearly identical peak positions and a comparable Pd⁰ to Pd²⁺ ratio. Notably, in all cases, the Pd 3d peaks were positively shifted, which can be attributed to the stabilization of Pd species by the polymer matrices and the formation of small Pd nanoparticles [

32,

33].

2.2. Catalytic Properties of Pd Catalysts, Deposited on Polymer-Modified Supports, in the Hydrogenation Process

The catalytic properties of the developed palladium catalysts were investigated in the hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds (2-propen-1-ol, phenylacetylene, 2-hexyn-1-ol) in an ethanol medium at a temperature of 40 °C and atmospheric hydrogen pressure. The activity of catalysts was evaluated by measuring the hydrogen uptake as a function of time.

Figure 6 shows the results of evaluation of activity of the catalysis in hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol.

The semi-hydrogenation point (50 mL of H₂ uptake) was reached after approximately 6 and 8 minutes of reaction for the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO and 1%Pd–CS/MgO catalysts, respectively. In contrast, for the 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 catalysts, this value was achieved only after 15 minutes of reaction (

Figure 6a). The reaction rate profiles, calculated from the hydrogen uptake data, show that in all cases the rate initially increased sharply, reaching maximum values of 5.2×10⁻⁶, 4.5×10⁻⁶, 3.0×10⁻⁶, and 2.7×10⁻⁶ mol/s for 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–CS/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15, and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15, respectively, followed by a subsequent decline (

Figure 6b,

Table 3).The higher catalytic activity observed for the MgO-based catalysts is likely due to the smaller size of Pd nanoparticles compared to those supported on SBA-15. Furthermore, the MgO-supported catalysts also exhibited higher selectivity toward propanol (82–83%) at complete substrate conversion, compared to the SBA-15-based catalysts (77–78%) (

Table 3).

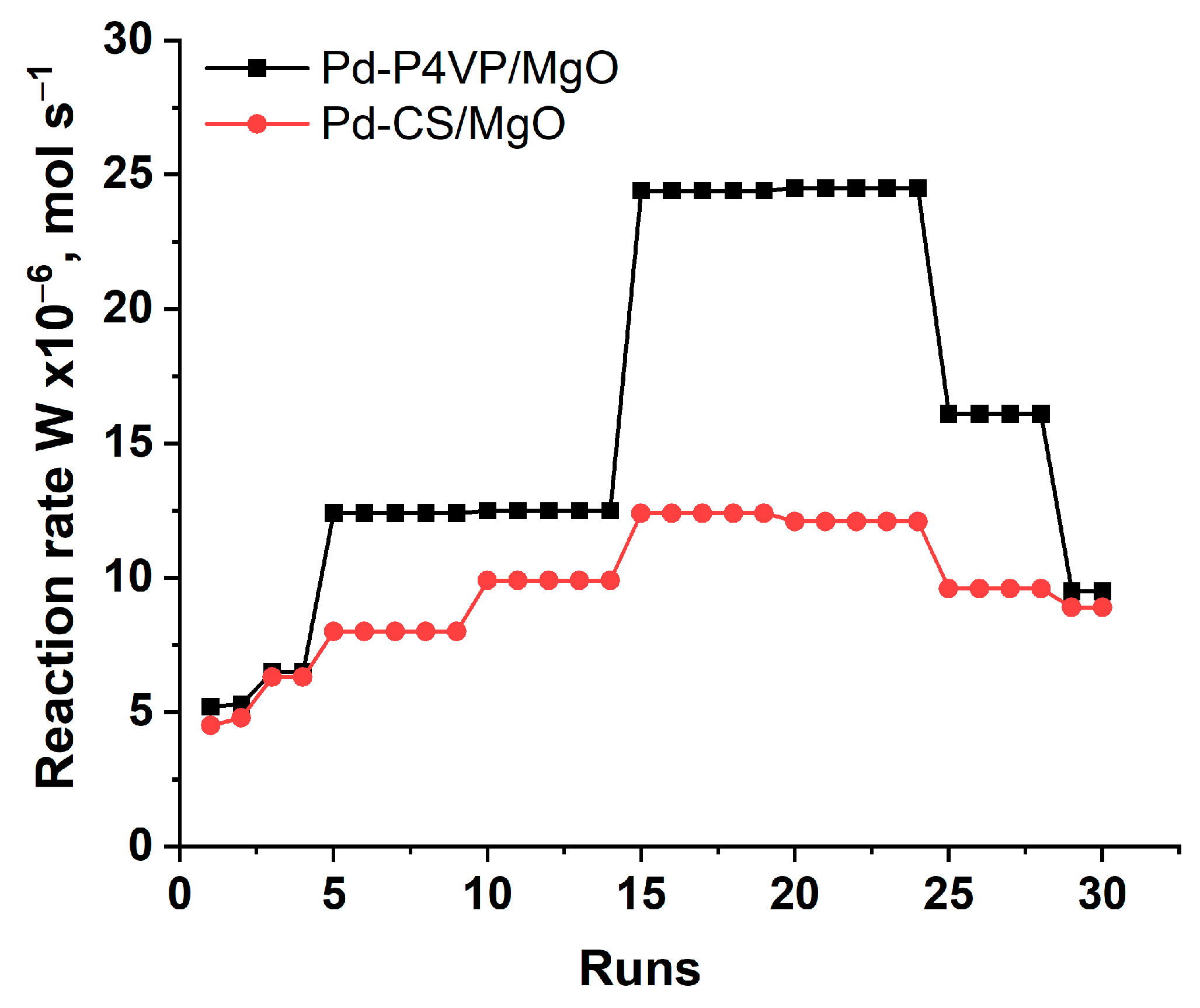

The 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst exhibited higher activity than 1%Pd–CS/MgO during the stability tests in the hydrogenation of successive portions of 2-propen-1-ol. Although both catalysts showed comparable activity during the first run, the difference between them increased progressively with the number of runs. For both systems, the reaction rate increased over the first 15 cycles, which may be attributed to the gradual swelling of the polymer–metal layer in ethanol. This effect was more pronounced for Pd–P4VP/MgO, likely due to the higher solubility and swelling ability of poly(4-vinylpyridine) compared to chitosan [

34]. After the 25th run, the activity of both catalysts began to decline, probably due to the accumulation of the saturated hydrogenation product, which could lead to shrinkage of the polymer layer. Nevertheless, by the 30th run, the activity of both catalysts remained higher than in the first run, confirming their overall operational stability.

Figure 7.

Reuse of 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO and 1%Pd–CS/MgO catalysts in hydrogenation of 2-propen-l-ol.

Figure 7.

Reuse of 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO and 1%Pd–CS/MgO catalysts in hydrogenation of 2-propen-l-ol.

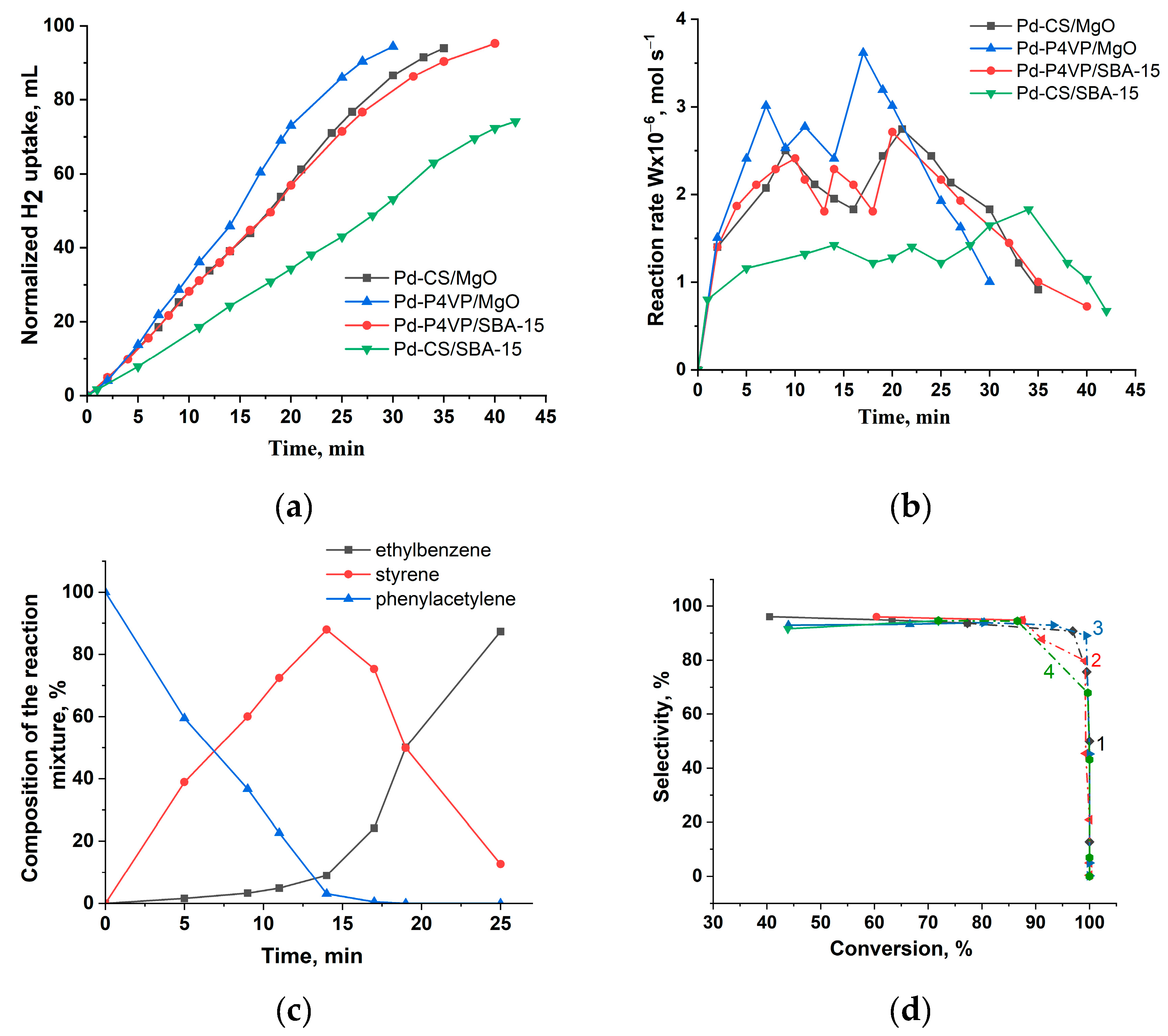

The catalytic performance of P4VP- and CS-modified palladium catalysts in the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene is shown in

Figure 8. Catalysts based on MgO exhibited higher activity compared to those supported on SBA-15. At the same time, P4VP-modified catalysts demonstrated greater activity than the corresponding chitosan-containing systems. The semi-hydrogenation point (50 mL) was reached after 14, 17, 17, and 28 minutes for 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–CS/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15, and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15, respectively (

Figure 8a). The hydrogenation rate of phenylacetylene, calculated from the hydrogen uptake data, is presented in

Figure 8b. In all cases, the reaction rate (W) increased rapidly within the first minutes and remained relatively constant until the semi-hydrogenation point. After that, the rate further increased, reached a maximum, and then sharply declined.

According to the chromatographic analysis, styrene is accumulated in the reaction medium on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO in the initial period, and then is reduced to ethylbenzene (

Figure 8c). Accumulation of styrene was also accompanied by the formation of small amounts of ethylbenzene, and its yield at the semi-hydrogenation point (14 min) was 9%. At the same time, the yield of styrene was 88%. The composition of the reaction mixture changed similarly on the rest Pd catalysts (

Figure S1a–c). The curves of the dependence of selectivity on conversion (

Figure 8d) show that all catalysts demonstrated similar selectivity to styrene (93–95%).

The hydrogenation rate and selectivity of the catalysts during phenylacetylene hydrogenation, calculated based on hydrogen uptake and chromatographic analysis data, respectively, are summarized in

Table 4.

Catalysts modified with poly(4-vinylpyridine) (P4VP) demonstrated higher activity and styrene selectivity compared to those containing chitosan (CS). Additionally, Pd catalysts supported on MgO showed greater hydrogenation activity than their SBA-15-based counterparts, as reflected in the higher hydrogenation rates for both the C≡C and C=C bonds. Notably, all catalysts demonstrate sufficiently high selectivity to styrene (93–95%) even at relatively high substrate conversion (77–93%).

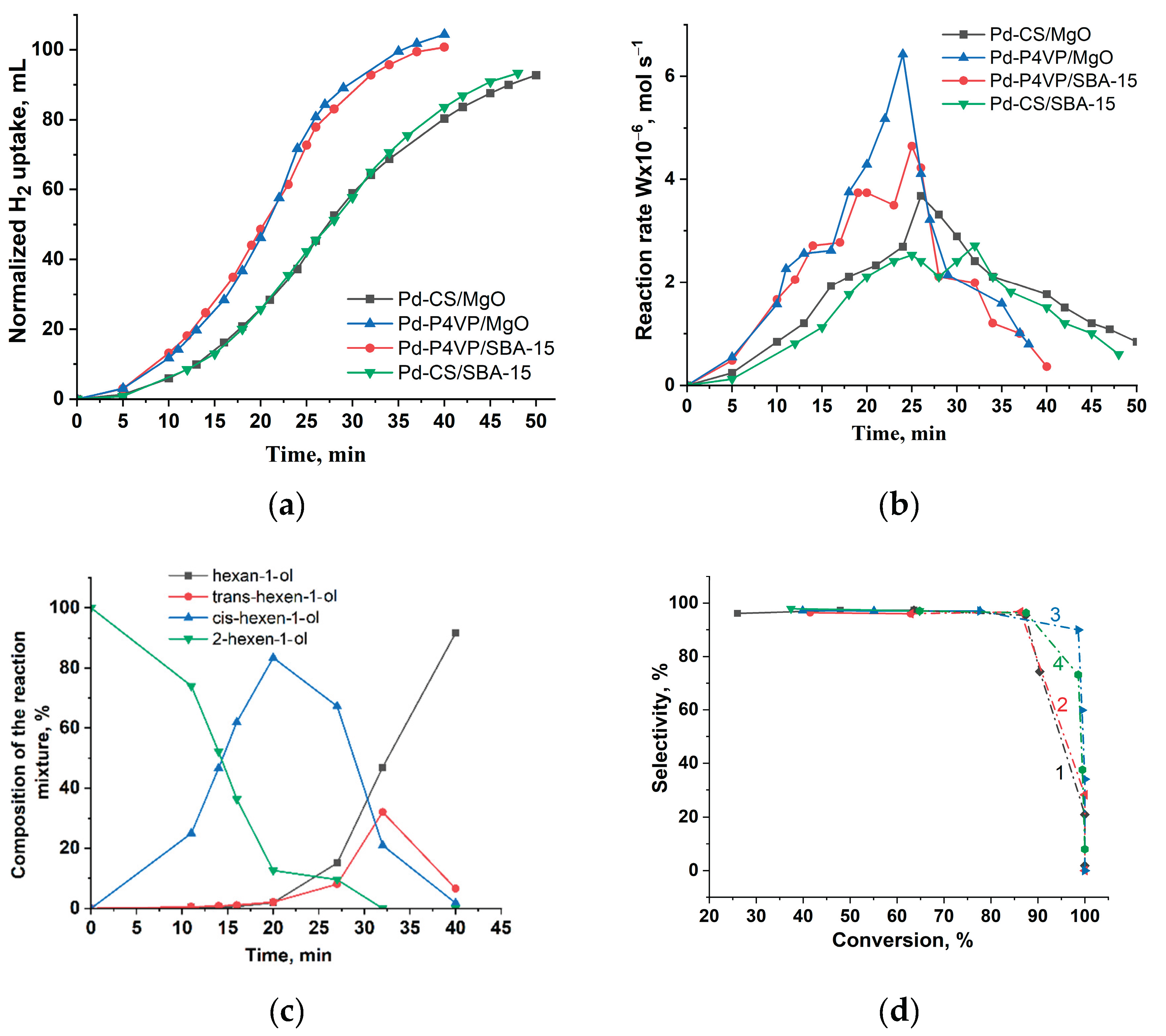

Figure 9 shows the results of catalyst activity evaluation in the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol.

Figure 9a presents the hydrogen uptake curves, while

Figure 9b displays the reaction rate profiles calculated from the hydrogen uptake data. Catalysts modified with P4VP exhibited higher activity compared to their chitosan-containing counterparts. Notably, the nature of the inorganic support (MgO vs. SBA-15) had a relatively minor effect on the overall hydrogenation kinetics. The semi-hydrogenation point (50 mL) was reached after 18, 25, 19, and 25 minutes for 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–CS/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15, and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15, respectively. As shown in

Figure 9b, the reaction rate gradually increased during the initial stage of the reaction. After reaching the semi-hydrogenation point, the rate sharply increased, followed by a rapid drop after passing the maximum. Before the semi-hydrogenation point, both P4VP-modified catalysts (1%Pd–P4VP/MgO and 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15) showed comparable reaction rates. However, beyond this point, 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO demonstrated slightly higher activity. A similar trend was observed for the chitosan-based catalysts, where the MgO-supported system outperformed the SBA-15-supported one at later stages of hydrogenation.

According to the chromatographic analysis, cis-2-hexen-1-ol is accumulated in the reaction medium on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO in the initial period, and then is reduced to hexan-1-ol (

Figure 9c). Accumulation of cis-2-hexen-1-ol was accompanied by the formation of small amounts of trans-2-hexen-1-ol and hexan-1-ol, and their yield at the semi-hydrogenation point was 1.3% and 0.8%, respectively. At the same time, the yield of cis-2-hexen-1-ol was 85%. After passing the semi-hydrogenation point (18 min), part of cis-2-hexen-1-ol accumulated was also transformed to trans-2-hexen-1-ol, which was eventually reduced to hexan-1-ol. The composition of the reaction mixture changed similarly on the rest Pd catalysts (

Figure S2a–c). The curves of the dependence of selectivity on conversion (

Figure 9d) shows that all catalysts possessed a near the same selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol.

A comparison of the catalytic properties of the catalysts during the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol is presented in

Table 5.

The nature of the polymer modifier significantly affected the catalysts activity. Catalysts modified with P4VP were more active than those containing chitosan. In contrast, the choice of support (MgO or SBA-15) had almost no effect on the rate of triple bond (C≡C) hydrogenation, but slightly influenced the hydrogenation of the double bond (C=C), with MgO-based catalysts being slightly more active than those supported on SBA-15 at this stage. It is noteworthy that neither the polymer nor the support affected the selectivity toward cis-2-hexen-1-ol, which remained consistently high (96–97%) for all catalysts tested.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Chitosan (CS, Mw 250,000), poly(4-vinylpyridine) (P4VP, Mw 60,000), magnesium oxide (MgO, pure grade), mesostructured silica SBA-15, palladium(II) chloride (PdCl₂, Pd content 59–60%), 2-propen-1-ol, phenylacetylene and 2-hexyn-1-ol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Ethanol (reagent grade) was obtained from Talgar Alcohol LLP (Talgar, Kazakhstan).

3.2. Synthesis of Pd Catalysts

The catalysts were prepared via a sequential adsorption method [

12,

35]. A 5 mL solution of 1.9×10

–2 M P4VP (0.01 g in 5 mL of water) or CS (0.016 g in 5 mL of water) was added dropwise to a suspension of the support (1 g MgO or SBA-15 in 15 mL of water) at room temperature, and resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h. Then, 5 mL of a 1.9×10

–2 M K

2PdCl

4 solution was added dropwise and stirred for 3 h. The concentration of polymer and palladium salt solutions (1.9×10

-2 M) were taken from a calculation for the preparation of catalysts with 1% palladium content and [Pd:polymer] molar ratio = 1:1 [

35]. The resulting catalyst was kept in the mother liquor for 12–15 h. Thereafter, it was washed with water, and then dried in air.

The quantitative content of Pd in aqueous solutions was detected via photoelectrocolorimetry (PEC). The measurement was carried out using an SF-2000 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (OKB Spektr, St. Petersburg, Russia) according to calibration curves (wavelength λ = 425 nm) [

23].

3.3. Characterisation of the Catalysts by Physicochemical Methods

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs were obtained on a scanning electron microscope JSM-6610 LV ("JEOL" Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15-20 kV. EDX elemental analysis was performed using an energy-dispersive detector built into the microscope (EDX Oxford Instruments) [

12].

IR spectra were obtained using a Nicolet iS5 from Thermo Scientific (USA), with a resolution of 3 cm

-1 in the 4000–400 cm

−1 region. Pellets for infrared analysis were obtained by grinding a mixture of 1 mg sample with 100 mg dry KBr, followed by pressing the mixture into a mold [

12].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs were obtained on a Zeiss Libra 200FE transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV [

12].

X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of palladium composites were recorded on an ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray and ultraviolet photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) [

12].

3.4. Methodology of Hydrogenation

The hydrogenation of the 2-propen-1-ol and acetylene compounds (2-hexyn-1-ol and phenylacetylene) was carried out in a thermostated glass reactor according to the procedure described in Ref [

13]. The reaction was carried out in an ethanol medium (25 mL) at atmospheric hydrogen pressure and a temperature of 40 °C, under intensive stirring (600–700 oscillations per minute). Before hydrogenation, the nanocatalyst (0.05 g) was reduced with hydrogen in the reactor for 30 min under conditions of intensive stirring. After the hydrogen treatment, a substrate (0.3 mL of 2-propen-1-ol and 0.25 mL of 2-hexyn-1-ol and phenylacetylene) was added to the reactor.

The hydrogenation products were analyzed using gas–liquid chromatography on a Chromos GC1000 chromatograph (Chromos Engineering, Dzerzhinsk, Russia) with a flame ionization detector in isothermal mode. A BP21 capillary column (FFAP) with a polar phase (PEG modified with nitroterephthalate) was used. This device was 50 m in length and 0.32 mm in inner diameter. The column temperature was 90 °C, the injector temperature was 200 °C, and helium served as the carrier gas. A total of 0.2 mL of the sample was investigated. Selectivity was calculated as the fraction of the target product present in the reaction products at a given degree of substrate conversion [

13].

4. Conclusions

The primary goal of this study was to investigate how the nature of the polymer modifier and the inorganic support influences the structure and catalytic behavior of Pd-based hybrid catalysts in the selective hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds. To this end, a series of Pd-based catalysts supported on MgO and mesostructured silica SBA-15, modified with P4VP and CS, were successfully synthesized via sequential adsorption of polymers and palladium ions under ambient conditions. Comprehensive physicochemical characterization using spectrophotometry, elemental analysis, IR spectroscopy, SEM, TEM, and XPS confirmed the formation of ternary hybrid systems (metal–polymer–support), with strong evidence of metal anchoring and potential interactions between the polymer and support surface.

TEM analysis revealed that the nature of the inorganic support plays a crucial role in determining Pd nanoparticle size and dispersion. Pd–P4VP/MgO catalysts showed uniformly distributed nanoparticles with smaller sizes (2–3 nm), while Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 systems exhibited larger, less uniformly distributed particles (8–10 nm). XPS data obtained after hydrogen pretreatment of the catalysts revealed partial reduction of Pd²⁺ to Pd⁰ (~50%), indicating that during hydrogenation conditions, palladium exists in a mixed oxidation state. Additionally, all samples exhibited binding energy shifts, which may be attributed to metal–polymer interactions and the small size of Pd nanoparticles.

Analysis of the hydrogenation results obtained for three model substrates (2-propen-1-ol, phenylacetylene, and 2-hexyn-1-ol) under mild conditions (40 °C, 1 atm H₂) revealed the following key observations:

- Catalysts supported on MgO exhibited higher activity in the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol and phenylacetylene compared to those based on SBA-15, which correlates with the formation of smaller and more uniformly dispersed Pd nanoparticles (2–3 nm on MgO vs. 8–10 nm on SBA-15), as confirmed by TEM analysis. In contrast, for the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol, the nature of the inorganic support had an insignificant effect on catalytic activity.

- P4VP-modified catalysts demonstrated higher activity than their chitosan-containing counterparts across all studied hydrogenation reactions. This difference became particularly pronounced during long-term stability tests conducted for Pd–P4VP/MgO and Pd–CS/MgO in the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol. In both cases, the reaction rate increased progressively with each subsequent substrate addition, likely due to swelling of the polymer layer in ethanol. However, the rate enhancement was more significant for the Pd–P4VP/MgO system, which can be attributed to the superior swelling capacity of poly(4-vinylpyridine) compared to chitosan.

- Selectivity trends were found to be substrate-dependent. In the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol, MgO-supported catalysts exhibited higher selectivity toward propanol than their SBA-15-supported counterparts. In the case of 2-hexyn-1-ol and phenylacetylene hydrogenation, neither the type of support nor the nature of the polymer modifier significantly affected selectivity: all catalysts exhibited consistently high selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol (96–97%) and styrene (93–95%), respectively.

These findings demonstrate that by varying the nature of the polymer modifier and the inorganic support, it is possible to tune both the activity and selectivity of polymer-modified palladium catalysts for selective hydrogenation reactions. The hybrid approach combining metal, polymer, and support opens up promising pathways for designing efficient and tunable heterogeneous catalytic systems. Importantly, the results highlight that the optimal choice of polymer and support should be made individually for each target reaction, as their influence on catalytic performance is strongly substrate-dependent

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Figure S1: Changes in the composition of the reaction mixture during the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene in the presence of 1%Pd–CS/MgO (a), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (b) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (c); Figure S2: Changes in the composition of the reaction mixture during the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol in the presence of 1%Pd–CS/MgO (a), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (b) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (c).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.A.; methodology, E.T.T.; software, A.A.N., S.N.A. and A.I.J.; validation, A.I.J., S.N.A., A.T.Z. and M.K.M.; formal analysis, A.S.A. and E.T.T.; investigation, S.N.A., A.I.J., A.A.N. and A.T.Z.; resources, A.S.A. and E.T.T.; data curation, S.N.A., A.I.J. A.A.N. and M.K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.A. and E.T.T.; writing—review and editing, A.S.A. and E.T.T.; visualization, E.T.T.; supervision, A.S.A.; project administration, A.S.A.; funding acquisition, A.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19679984).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The XPS and TEM studies were performed on the equipment of the Resource Centers “Physical methods of surface investigation” and “Nanotechnology” of the Scientific Park of St. Petersburg University. The IRS, elemental analysis and SEM studies were carried out on the equipment of the Laboratory of Physical Research Methods of D.V. Sokolsky Institute of Fuel, Catalysis and Electrochemistry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Friend, C.M.; Xu, B. Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Central Science for a Sustainable Future. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouramiri, B.; Hadadianpour, E.; Saghebi, S. Palladium supported on alumina as a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for direct arylation of 6-substituted imidazo[2,1-b]thiadiazole via C single bond H bond activation. Tetrahedron Letters 2024, 150, 155286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Shin, S.-J.; Baek, H.; Choi, Y.; Hyun, K.; Seo, M.; Kim, K.; Koh, D.-Y.; Kim, H.; Choi, M. Dynamic metal-polymer interaction for the design of chemoselective and long-lived hydrogenation catalysts. Science Advances 2020, 6, eabb7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erigoni, A.; Diaz, U. Porous Silica-Based Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Catalysts: A Review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Shrivastava, S.; Sharma, V.; Srivastava, P.; Shankhwar, V.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Agarwal, D.D. Karanja seed shell ash: A sustainable green heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. Results in Engineering 2023, 18, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Mathai, S. Recent advances in heterogeneous magnetic Pd-NHC catalysts in organic transformations. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 2023, 996, 122768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E. , Toste, F.D., Somorjai, G.A. Polymer-Encapsulated Metallic Nanoparticles as a Bridge Between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis. Catalysis Letters 2015, 145, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deelen, T.W.; Hernández Mejía, C.; de Jong, K.P. Control of metal-support interactions in heterogeneous catalysts to enhance activity and selectivity. Nature Catalysis 2019, 2, 955–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Lyalin, A.; Taketsugu, T. Role of the Support Effects on the Catalytic Activity of Gold Clusters: A Density Functional Theory Study. Catalysts 2011, 1, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Pan, H.; Chen, J.; Fan, L.; Guo, J.; Wang, W. Palladium supported on urea-containing porous organic polymers as heterogeneous catalysts for C–C cross coupling reactions and reduction of nitroarenes. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2021, 25, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, B.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Zhang, J. Polymer-supported chiral palladium-based complexes as efficient heterogeneous catalysts for asymmetric reductive Heck reaction. Green Synthesis and Catalysis 2024, 5, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukharbayeva, F.; Zharmagambetova, A.; Talgatov, E.; Auyezkhanova, A.; Akhmetova, S.; Jumekeyeva, A.; Naizabayev, A.; Kenzheyeva, A.; Danilov, D. The Synthesis of Green Palladium Catalysts Stabilized by Chitosan for Hydrogenation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharmagambetova, A.; Auyezkhanova, A.; Talgatov, E.; Jumekeyeva, A.; Buharbayeva, F.; Akhmetova, S.; Myltykbayeva, Z.; Nieto, J.M.L. Synthesis of polymer protected Pd–Ag/ZnO catalysts for phenylacetylene hydrogenation. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas, M.; El Haskouri, J.; Ros-Lis, J.V.; Marcos, M.D.; Amorós, P.; Úbeda, M.Á.; Pérez-Pla, F. Highly Active Hydrogenation Catalysts Based on Pd Nanoparticles Dispersed along Hierarchical Porous Silica Covered with Polydopamine as Interfacial Glue. Catalysts 2020, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissing, M.; Niehues, M.; Ravoo, B.J.; Studer, A. Synthesis and Immobilization of Metal Nanoparticles Using Photoactive Polymer-Decorated Zeolite L Crystals and Their Application in Catalysis. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis 2020, 362, 2245–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Q.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.; Zeng, M. Chitosan supported Pd0 nanoparticles encaged in Al or Al-Fe pillared montmorillonite and their catalytic activities in Sonogashira coupling reactions. Applied Clay Science 2020, 195, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarjuna, R.; Sharma, S.; Rajesh, N.; Ganesan, R. Effective Adsorption of Precious Metal Palladium over Polyethyleneimine-Functionalized Alumina Nanopowder and Its Reusability as a Catalyst for Energy and Environmental Applications. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 4494–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakap, M.; Kalu, E.E.; Özkar, S. Polymer-immobilized palladium supported on TiO2 (Pd–PVB–TiO2) as highly active and reusable catalyst for hydrogen generation from the hydrolysis of unstirred ammonia–borane solution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubiakiewicz, E.; Modelska, M.; Brzezinska, M.; Binczarski, M.J.; Severino, C.J.; Stanishevsky, A.; Witonska, I. Influence of modification of supported palladium systems by polymers: PVP, AMPS and AcrAMPS on their catalytic properties in the reaction of transformation of biomass into fuel bio-components. Fuel 2020, 271, 117584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, C.; Toniolo, L.; Cavinato, G.; Forte, C.; Ghignoli, C.; Ishak, R.; Cavani, F.; Raspolli Galletti, A.M. A hybrid polyketone–SiO2 support for palladium catalysts and their applications in cinnamaldehyde hydrogenation and in 1-phenylethanol oxidation. Applied Catalysis A: General 2015, 496, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas, M.; El Haskouri, J.; Ros-Lis, J.V.; Marcos, M.D.; Amorós, P.; Úbeda, M.Á.; Pérez-Pla, F. Highly Active Hydrogenation Catalysts Based on Pd Nanoparticles Dispersed along Hierarchical Porous Silica Covered with Polydopamine as Interfacial Glue. Catalysts 2020, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyezkhanova, A.S.; Zharmagambetova, A.K.; Talgatov, E.T. Jumekeyeva, A.I.; Akhmetova, S.N.; Myltykbayeva, Z.K.; Kalkan, I.; Koca, A.; Naizabayev, A.A.; Zamanbekova, A.T. Chitosan-Modified SBA-15 as a Support for Transition Metal Catalysts in Cyclohexane Oxidation and Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts 2025, 15, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgatov, E.; Auyezkhanova, A.; Zharmagambetova, A.; Tastanova, L.; Bukharbayeva, F.; Jumekeyeva, A.; Aubakirov, T. The Effect of Polymer Matrix on the Catalytic Properties of Supported Palladium Catalysts in the Hydrogenation of Alkynols. Catalysts 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnami, A.; Croué, J.-P.; Aghayani, E.; Pourakbar, M. A catalytic ozonation process using MgO/persulfate for degradation of cyanide in industrial wastewater: mechanistic interpretation, kinetics and by-products. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 36965–36977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Velavan, R.; Batoo, K.M.; Raslan, E.H. Microstructure, optical and photocatalytic properties of MgO nanoparticles. Results in Physics 2020, 16, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; Santillán, R.; Fuentes Camargo, I.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Andraca Adame, J.A.; Martínez Gutiérrez, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(2-vinylpyridine) and Poly(4-vinylpyridine) with Metal Oxide (TiO2, ZnO) Films for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange and Benzoic Acid. Polymers 2022, 14, 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Pang, T.; Wu, L.; Guan, Y.; Yin, L. In situ synthesis of the Fe3O4@poly(4-vinylpyridine)-block-polystyrene magnetic polymer nanocomposites via dispersion RAFT polymerization. Nanocomposites 2022, 8, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elías, V.R.; Ferrero, G.O.; Oliveira, R.G.; Eimer, G.A. Improved stability in SBA-15 mesoporous materials as catalysts for photo-degradation processes. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2016, 236, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry Krishna Charan, P.; Ranga Rao, G. Investigation of chromium oxide clusters grafted on SBA-15 using Cr-polycation sol. Journal of Porous Materials 2012, 20, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, J.M.; Morales, M.V.; Rodriguez-Ramos, I.; Rocha, M. CuPd Bimetallic Nanoparticles Supported on Magnesium Oxide as an Active and Stable Catalyst for the Reduction of 4-Nitrophenol to 4-Aminophenol. International Journal of Green Technology 2018, 3, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, M.; Nowicka, E.; Douthwaite, M.; Iqbal, S.; Miedziak, P.; Edwards, J.K.; Brett, G.L.; He, Q.; Knight, D.W.; Morgan, D.J.; et al. Multifunctional supported bimetallic catalysts for a cascade reaction with hydrogen auto transfer: synthesis of 4-phenylbutan-2-ones from 4-methoxybenzyl alcohols. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 1928–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Yuan, F.; Zhu, Y. Improvement Effect of Ni to Pd-Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst for Selective Hydrogenation of Cinnamaldehyde to Hydrocinnamaldehyde. Catalysts 2018, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, P.; Tan, W.; Jiang, F.; Tang, R. Palladium supported on amino functionalized magnetic MCM-41 for catalytic hydrogenation of aqueous bromate. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 38743–38749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharmagambetova, A.K.; Talgatov, E.T.; Auyezkhanova, A.S.; Tumabayev, N.Z.; Bukharbayeva, F.U. Effect of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the catalytic properties of Pd/γ-Fe2O3 in phenylacetylene hydrogenation. Reac. Kinet. Mech. Cat. 2020, 131, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharmagambetova, A.K.; Talgatov, E.T.; Auyezkhanova, A.S.; Bukharbayeva, F.U.; Jumekeyeva, A.I. Polysaccharide-Stabilized PdAg Nanocatalysts for Hydrogenation of 2-Hexyn-1-ol. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

SEM/EDX elemental mapping images of 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst.

Figure 1.

SEM/EDX elemental mapping images of 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst.

Figure 2.

IR spectra of the MgO, P4VP, P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO.

Figure 2.

IR spectra of the MgO, P4VP, P4VP/MgO, 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO.

Figure 3.

SEM images of MgO (a) P4VP/MgO (b), 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (c).

Figure 3.

SEM images of MgO (a) P4VP/MgO (b), 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (c).

Figure 4.

TEM images of the Pd–P4VP/MgO (a,b) and 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (c,d) catalysts at different magnifications.

Figure 4.

TEM images of the Pd–P4VP/MgO (a,b) and 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (c,d) catalysts at different magnifications.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of Pd3d of the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (a) and 1%Pd–CS/MgO (b), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (c) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (d) after treatment with H2.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of Pd3d of the 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (a) and 1%Pd–CS/MgO (b), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (c) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (d) after treatment with H2.

Figure 6.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a) and the change in reaction rate (b) over the developed palladium catalysts during the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.3 mL.

Figure 6.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a) and the change in reaction rate (b) over the developed palladium catalysts during the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.3 mL.

Figure 8.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a), the change in reaction rate (b), the change in the composition of the reaction mixture on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (c) and dependence of selectivity to styrene with the substrate conversion on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (curve 1), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (curve 2), 1%Pd–CS/MgO (curve 3) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (curve 4) (d) at the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.25 mL.

Figure 8.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a), the change in reaction rate (b), the change in the composition of the reaction mixture on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (c) and dependence of selectivity to styrene with the substrate conversion on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (curve 1), 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 (curve 2), 1%Pd–CS/MgO (curve 3) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (curve 4) (d) at the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.25 mL.

Figure 9.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a), the change in reaction rate (b), the change in the composition of the reaction mixture on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (c) and dependence of selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol with the substrate conversion on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (curve 1), 1%Pd– P4VP/SBA-15 (curve 2), 1%Pd–CS/MgO (curve 3) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (curve 4) (d) at the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.25 mL.

Figure 9.

Kinetics of the hydrogen uptake (a), the change in reaction rate (b), the change in the composition of the reaction mixture on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO catalyst (c) and dependence of selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol with the substrate conversion on 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO (curve 1), 1%Pd– P4VP/SBA-15 (curve 2), 1%Pd–CS/MgO (curve 3) and 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 (curve 4) (d) at the hydrogenation of 2-hexyn-1-ol. Reaction conditions: T—40 °C, PH2—1 atm, mcat—0.05 g, solvent C2H5OH—25 mL, substrate—0.25 mL.

Table 1.

Results of Pd ions deposition on polymer-modified support.

Table 1.

Results of Pd ions deposition on polymer-modified support.

| Catalyst |

m(Pd)

before

adsorption, mg |

m(Pd)

after

adsorption, mg |

Ads. degree, % |

Pd content, % |

| PEC |

EDX |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO |

10.1 |

0.1 |

99 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| 1%Pd–CS/MgO |

0.1 |

99 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 |

0.4 |

96 |

1.0 |

n.a. |

| 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 |

0.5 |

95 |

1.0 |

n.a. |

Table 3.

Catalytic properties of Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports, in the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol *.

Table 3.

Catalytic properties of Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports, in the hydrogenation of 2-propen-1-ol *.

| Catalyst |

Wmax·10−6,

mol s−1

|

Selectivity, % |

Conversion, % |

| Propanal |

Propanol |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO |

5.2 |

16.6 |

83.4 |

100 |

| 1%Pd–CS/MgO |

4.5 |

17.8 |

82.2 |

100 |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 |

3.0 |

22.6 |

77.4 |

100 |

| 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 |

2.7 |

22.0 |

78.0 |

100 |

Table 4.

Results of the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene on synthesized Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports*.

Table 4.

Results of the hydrogenation of phenylacetylene on synthesized Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports*.

| Catalyst |

Wmax·10−6, mol s−1

|

Selectivity to styrene, % |

Conversion, % |

| С≡С |

С=С |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO |

3.0 |

3.6 |

94 |

77 |

| 1%Pd–CS/MgO |

2.5 |

2.7 |

93 |

93 |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

95 |

88 |

| 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

94 |

87 |

Table 5.

The results of 2-hexyn-1-ol hydrogenation on the synthesized Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports*.

Table 5.

The results of 2-hexyn-1-ol hydrogenation on the synthesized Pd catalysts, deposited on polymer-modified supports*.

| Catalyst |

W·10−6, mol s−1

|

Selectivity to cis-2-hexen-1-ol, % |

Conversion, % |

| С≡С |

С=С |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/MgO |

3.7 |

6.4 |

97 |

81 |

| 1%Pd–CS/MgO |

2.7 |

3.7 |

97 |

78 |

| 1%Pd–P4VP/SBA-15 |

3.7 |

4.6 |

97 |

86 |

| 1%Pd–CS/SBA-15 |

2.5 |

2.7 |

96 |

88 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).