1. Introduction

Skin, the largest organ of the human body, provides a highly specialized barrier that maintains internal homeostasis and protects against mechanical, thermal, chemical and microbial challenges. Continuous exposure to these stressors makes it particularly vulnerable to acute injuries and chronic lesions. Wound repair relies on a tightly regulated cascade of inflammation, cell migration, proliferation and matrix remodeling [

1]. When any component of this cascade is disrupted—by infection, metabolic imbalance, impaired perfusion or persistent oxidative stress, the healing process can stagnate, giving rise to chronic, non-healing wounds.

Conditions such as diabetic foot ulcers, deep burns and post-surgical complications illustrate the difficulty of managing complex wounds in clinical practice. These lesions often present dysregulated inflammation, limited angiogenesis and inadequate extracellular matrix turnover, factors that collectively delay closure and increase the risk of microbial colonization. Conventional dressings offer protection but usually fail to provide the biological support required for effective regeneration, to maintain an optimal level of moisture or to limit early infection. As the incidence of chronic wounds rises with population aging, diabetes and recurrent infections, the need for advanced bioactive materials that actively participate in tissue repair has become increasingly evident.

Composite systems that merge natural polymers with bioactive ceramics have garnered interest due to their ability to replicate ECM properties while providing structural enhancement and biological usefulness. Collagen is still the most important natural biopolymer because it is so common in ECM and may control how cells behave [

2]. The fibrillar structure of this material helps it stick to things, move around, and grow. Its biodegradability and ability to hold a lot of water make it a good choice for advanced wound dressings [

3]. Collagen-based scaffolds can also hold medicinal compounds since they are naturally porous, which lets you change the local microenvironment.

Hydroxyapatite adds to these qualities by giving the material mechanical stability, bioactivity, and ionic signals that are important for remodelling the matrix [

4]. HAp is a calcium phosphate phase that is quite similar to natural bone mineral. It helps cells stick to it and adds some rigidity, which might be helpful in deep wounds or defects that are under mechanical stress [

5]. Collagen–hydroxyapatite composites have repeatedly demonstrated improved regenerative outcomes, establishing them as a strong platform for next-generation bioactive dressings.

In addition to HAp, several other bioactive ceramics have been investigated for their influence on soft-tissue repair. Bioactive glasses release calcium and silicate ions that encourage fibroblast growth, collagen production, and angiogenesis [

2,

3]. They also have antibacterial properties on their own [

4,

5]. Amorphous calcium phosphates provide quick breakdown and ion release, advantageous for re-epithelialization, while tricalcium phosphates impart moderate structural stability for deeper lesions [

6,

7]. Mesoporous silica enhances therapeutic loading and regulated release, while wollastonite facilitates the creation of a collagen-rich matrix in ischemic wounds [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. When used in controlled amounts, metal-oxide nanoparticles like ZnO, MgO, or CuO add to antibacterial action without harming cells [

6,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Despite these advances, early microbial colonization remains a significant obstacle to successful wound healing. Infection prolongs inflammation, intensifies oxidative stress and increases the risk of systemic complications. For this reason, antimicrobial functionalization is now a key design feature in composite dressings. Essential oils have emerged as appealing candidates because they combine broad-spectrum antimicrobial action with anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative effects and show limited risk of inducing bacterial resistance [

17,

18,

19].

An increasing amount of research shows that EOs could be useful as bioactive ingredients in composite wound dressings [

19]. Lavender oil has been linked to faster wound healing, more collagen deposition, and less redness and pain, especially after surgery [

20,

21]. Basil oil has been proven to help reduce early inflammation, speed up contraction, and speed up re-epithelialization [

22,

23,

24]. Cinnamon oil has significant antibacterial and antioxidant properties that help infected wounds heal by lowering oxidative stress and encouraging the production of keratin and collagen [

25,

26]. Tea tree oil, whether used alone or with rosemary oil, has been shown to work against biofilm development and microbial load, even in infections with methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus [

27,

28,

29]. Thyme oil, which has a lot of thymol and carvacrol, helps with all stages of healing by lowering pro-inflammatory cytokines, speeding up epithelialization, and tea tree encouraging angiogenesis and granulation [

30,

31,

32]. Newer delivery technologies, including PLGA nanoparticles or hydrogel matrices, make these oils even more stable and help them release at the right times [

33,

34]. Research on natural polymer films and hydrogels infused with lavender, thyme, mint, cinnamon, tea tree, rosemary, eucalyptus, or lemongrass indicates significant antibacterial efficacy against

Staphylococcus aureus and

Escherichia coli, in addition to advantageous mechanical characteristics [

35,

36]. Combinations of clove, oregano and tea tree oils with plant - or synthetic -derived polymers also demonstrate broad antimicrobial inhibition and biocompatibility, reinforcing their suitability for infected or high-risk wounds [

37,

38,

39,

40].

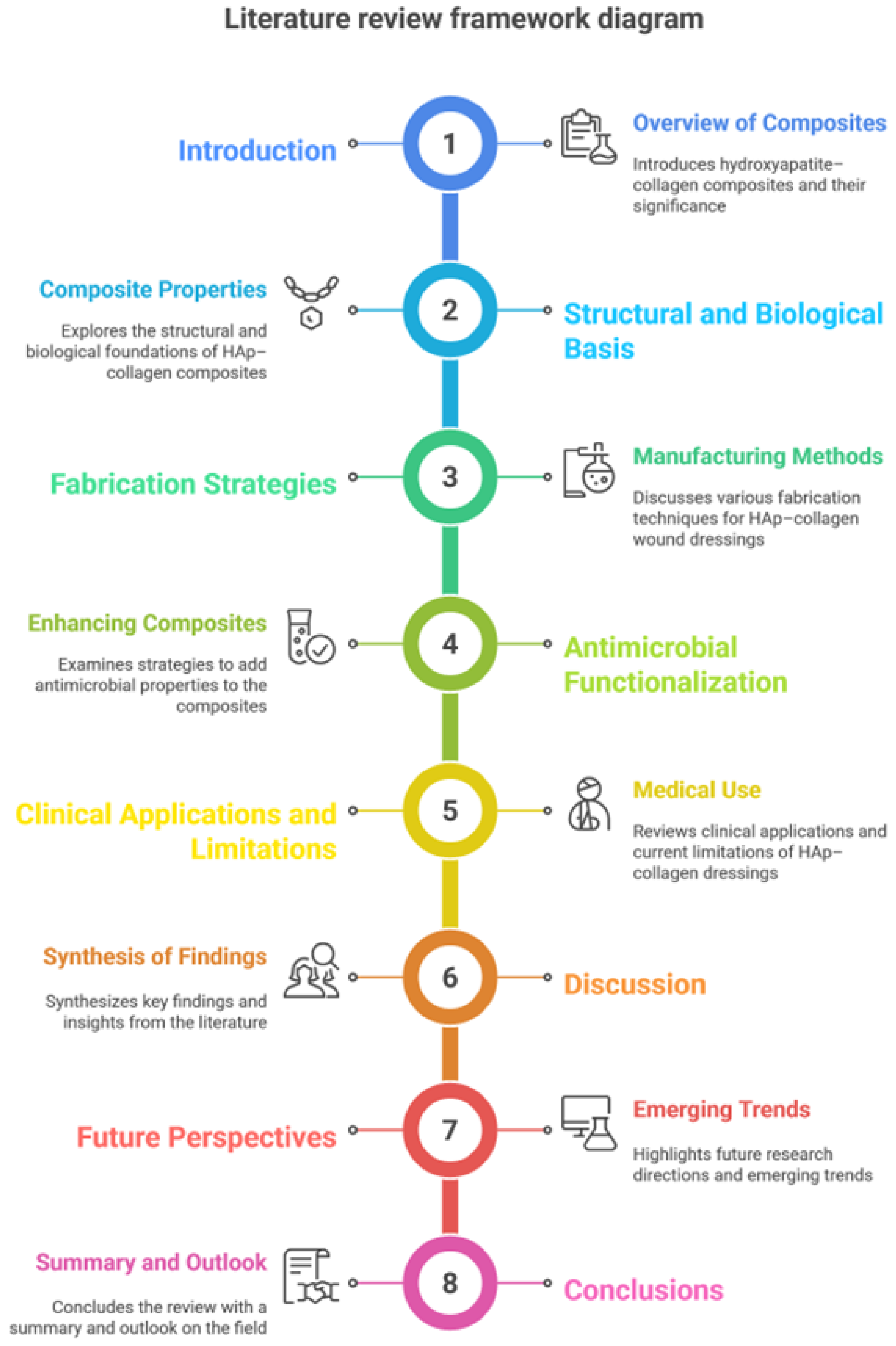

Figure 1.

Literature review framework diagram.

Figure 1.

Literature review framework diagram.

To identify studies relevant to bioactive composite dressings for wound regeneration based on HAp - Coll, searches were conducted in Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science databases using keywords related to wound dressings, biomaterial composites, biocompatibility and bioactive wound healing. Priority was given to publications from the last five years. This review includes articles with the specific theme of composite dressing manufacturing, biological performance, or therapeutic potential in wound healing.

Considering all these aspects, the present review consolidates the existing knowledge on the optimization of Hap-Col composites for wound healing through advanced manufacturing techniques, functionalization with natural antimicrobial agents and evaluation of biological performance. Also, this paper synthesizes recent advances in the design of HAp-col dressings for wound healing, highlights the role of essential oils in infection control and regeneration and presents how these convergent methods can generate new generations of bioactive dressings that meet the clinical requirements of both acute and chronic wounds.

2. Structural and Biological Basis for Hydroxyapatite–Collagen Composites

2.1. Collagen - Biological Scaffold Framework

Collagen is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix and is what gives most connective tissues their strength and flexibility. Its importance in wound healing is mainly due to its highly structured fibrillar structure that helps fibroblasts connect, move, and multiply [

9]. Collagen fibers can retain and bind a lot of water, which helps maintain a moist wound microenvironment[

41]. This is important for the creation of granulation tissue, the growth of new blood vessels, and for faster re-epithelialization. Endogenous collagenases and gelatinases break down collagen in a way that does not produce toxic byproducts, which allows the structure to change shape as the wound heals. In its natural form, collagen is mechanically weak and breaks down quickly when there is inflammation, which can weaken the structure of deep or exuding wounds. These deficiencies require improvement in composite systems aimed at improving stability, durability, and biological efficacy [

42,

43,

44].

2.2. Hydroxyapatite - Bioactive Mineral Component

Hydroxyapatite (Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂) is a calcium phosphate ceramic that closely resembles bone mineral, adding features that make collagen-based scaffolds stronger. Its natural bioactivity facilitates the establishment of a stable interface with host tissues, supported by the release of ions (Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻) and its ability to enhance mineral formation. In the case of a wound, HAp can help maintain local pH, promote fibroblast growth, and stimulate angiogenesis [

45,

46,

47]. Hydroxyapatite adds stiffness and compressive strength, which are more important for deep wounds, those subject to mechanical stress, or those where a portion of the bone is exposed. The mineral part also helps maintain a stable structure during the early inflammatory period, when collagen is rapidly breaking down [

47].

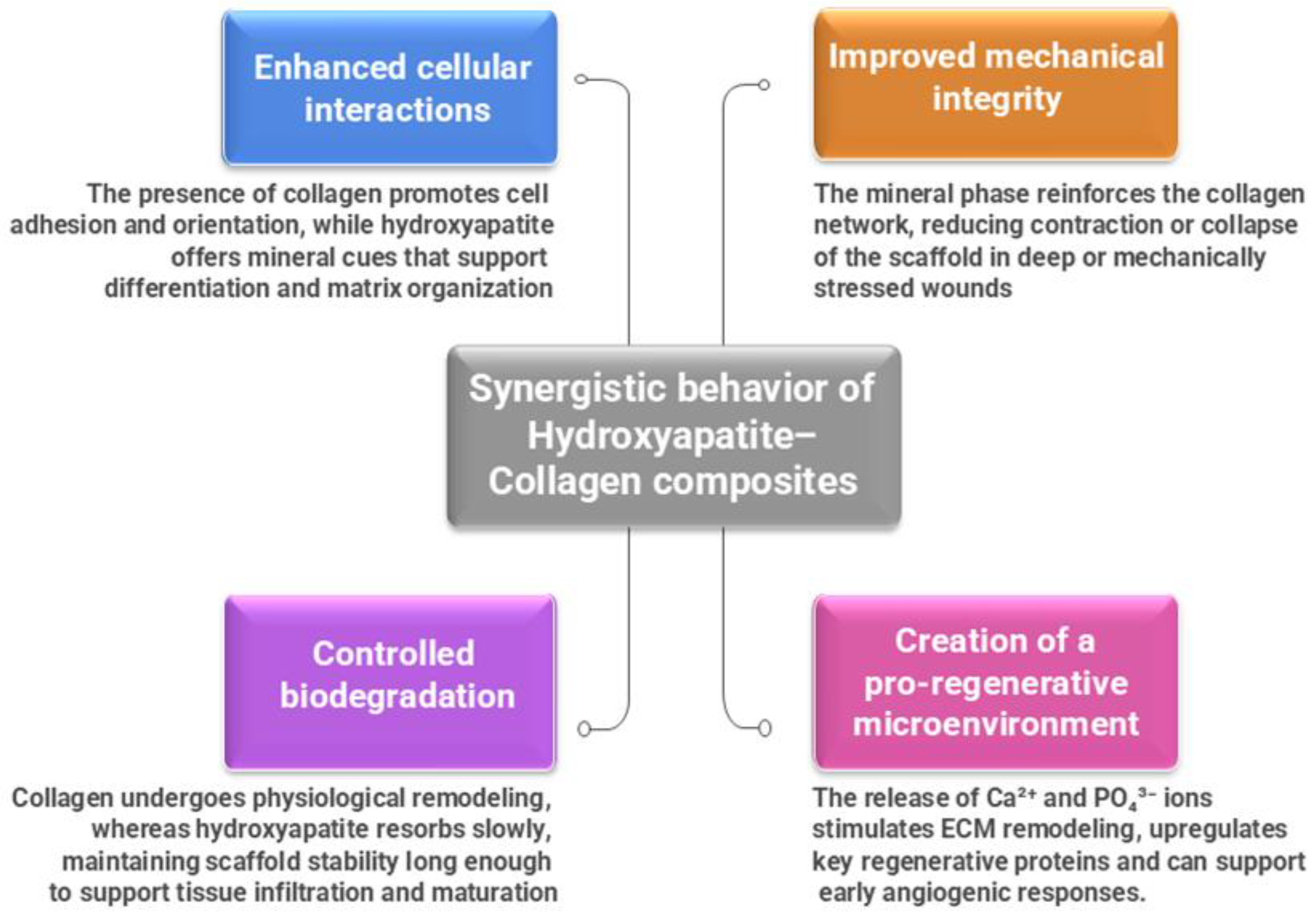

2.3. Synergistic Behavior of Hydroxyapatite–Collagen Composites

When collagen and HAp are combined, they form a hybrid scaffold with characteristics that neither of them possesses separately. The resulting composite material more closely mimics the hierarchical structure of natural tissues, combining the elasticity, hydration, and biological signaling of collagen with the rigidity, bioactivity, and mineral exchange capacity of hydroxyapatite [

48]. Their synergy generates numerous important benefits for their regenerative function.

Figure 2 provides a summary of these combined effects: improved cellular connections, regulated biodegradation, improved mechanical strength, and establishment of a microenvironment that encourages healing [

49].

Figure 2.

Synergistic behavior of Hydroxyapatite–Collagen composites.

Figure 2.

Synergistic behavior of Hydroxyapatite–Collagen composites.

These characteristics make these types of composite materials particularly good for difficult-to-treat wounds, such as persistent ulcers, deep-seated diabetic foot deformities, or wounds with visible bone [

50]. Their ability to act as a mechanically supportive scaffold and, at the same time, a biologically active interface positions them as a promising candidate for regenerative dressings.

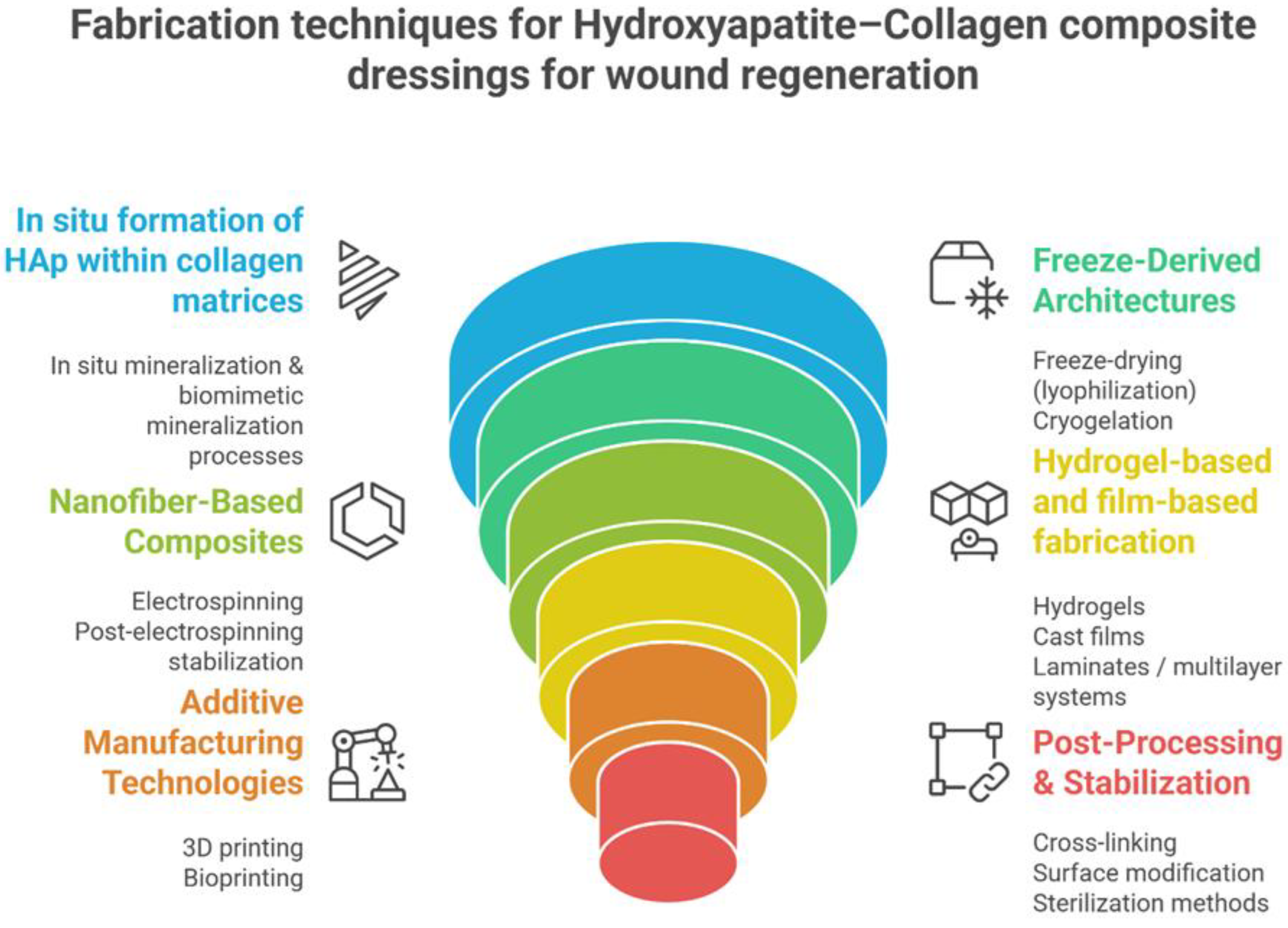

3. Fabrication Strategies for Hydroxyapatite–Collagen Composite Wound Dressings

The structural, mechanical and biological performance of HAp-Col composite dressings are influenced by the manufacturing method [

51,

52,

53]. Processing parameters, such as collagen-mineral ratio, HAp particle size, degree of mineralization, pore architecture, crosslink density and the way the interface between collagen and HAp is formed, influence the degradation behavior, mechanical stability, moisture regulation and release of incorporated therapeutic agents [

54,

55,

56]. By adjusting these variables, it is possible to obtain different materials: from highly absorbent sponges, suitable for exudative wounds, to thin membranes, nanofibrous mats, hydrogels and multilayer constructions with protective or controlled delivery functions[

48,

57].

Figure 3 provides a graphical summary of the main ways in which HAp-Col dressings are manufactured.

Figure 2.

Fabrication techniques for Hap-Col composites dressings for wound regeneration

Figure 2.

Fabrication techniques for Hap-Col composites dressings for wound regeneration

3.1. In Situ Mineralization

In situ mineralization involves the precipitation of hydroxyapatite directly into a collagen matrix by mixing calcium and phosphate precursors under predetermined pH and ionic conditions. This approach closely resembles the initial phases of natural biomineralization and facilitates careful control of the Ca/P ratio, crystal shape, and degree of nucleation on collagen fibrils. The resulting nanocrystalline HAp is uniformly distributed along and within collagen fibers, resulting in a more cohesive interface and stiffer material than physical mixtures [

58].

Biomimetic strategies take the concept even further. Preformed collagen structures are immersed in simulated body fluids (SBFs), calcium phosphate-rich solutions, or polymer-activated precursor liquid systems (PILPs), generating fine-crystal apatite coatings similar to immature bone minerals. Enzyme-assisted mineralization, exemplified by alkaline phosphatase-mediated conversion of organic phosphate precursors, has been investigated to emulate tissue-like mineral gradients [

59]. These methods create more bioactive composites, help cells adhere better to them, and allow for modification of mineral composition [

60]. For soft tissue wounds, lower levels of mineralization are usually better. For wounds with partial exposure of bone tissue or areas subject to mechanical stress, higher amounts of HAp may have better effects.

3.2. Freeze-Drying and Sponge Formation

Freeze-drying (lyophilization) is one of the most widely used techniques for producing porous HAp-Col scaffolds. A uniform mixture of collagen and HAp nanoparticles is freeze-dried in a controlled environment, and the ice crystals act as temporary molds. During freeze-drying, the ice sublimes, creating interconnected porous structures with porosities of 90-95%, with pore diameters typically between 50 and 300 µm. These structures facilitate the passage of oxygen and nutrients, the penetration of cells into them, and the exudate is well managed

[61]. This makes them suitable for chronic or exudative wounds. Changing the freezing rate and polymer concentration changes the alignment, density, and compression behavior of the pores. The addition of HAp makes the matrix stronger and prevents it from shrinking too much when drying, all without losing its porosity

[62]. Cryogelation, a similar method to lyophilization, creates elastic, highly interconnected networks with larger macropores

[63]. These networks are perfect for soft, flexible dressings that need to fit around uneven wound edges or withstand repeated compression

[64,65].

3.3. Electrospinning of Composite Nanofibers

Electrospinning makes it possible to make nanofibrous dressings that resemble natural extracellular matrix at the nanoscale. HAp-Col composite nanofibers can be made by mixing collagen with HAp precursors, placing preformed HAp nanoparticles in collagen solutions, or using simultaneous electrospinning and electrospraying of mineral particles

[66]. Coaxial electrospinning makes it possible to release bioactive chemicals in a controlled or gradual manner

[67]. Electrospun composite membranes have a large specific surface area, tuned fiber diameters, and tunable porosity. These properties help keratinocytes and fibroblasts to attach to the membranes and be properly targeted. They also provide an effective base for loading antimicrobial agents - including essential oils, peptides, metal ions, or antibiotics - allowing for their controlled release

[68]. Post-spinning stabilization (UV irradiation, ethanol vapor, dehydrothermal treatment or genipin crosslinking) is essential for improving moisture stability and adjusting degradation profiles.

3.4. Hydrogel-Based and Film-Based Fabrication

Hydrogels are produced by neutralizing acidic collagen dispersions and allowing fibrillogenesis to proceed in the presence of dispersed hydroxyapatite. The viscoelastic properties and wound degradation kinetics can be modified by changing the collagen concentration, pH, or by adding mild crosslinking agents. These hydrogels can be applied directly to wounds, used as injectable dressings for deep cavities, or partially dried to form flexible films [

69]. Cast films create thin layers with tunable permeability and mechanical strength. These types of films work best as the first contact layer with a wound and can be used with absorbent substrates. Laminated structures—integrating films, nanofibers, and sponges—allow fine control of moisture balance, mechanical behavior, and distribution of incorporated therapeutic agents.

3.5.Additive Manufacturing and Bioprinting

Using additive manufacturing, body-fitting HAp-Col dressings with carefully designed porosity and mineral gradients can be fabricated [

70]. Collagen-based bioinks reinforced with HAp nanoparticles can be extruded layer by layer to generate customized scaffolds. Bioprinting allows for the subsequent incorporation of cells, angiogenic signals, or bioactive molecules [

71]. Although initially developed for bone regeneration, the architectural control offered by 3D printing is increasingly relevant for complex wound dressings—especially for defects that require mechanical support, customized geometry, or integration with bone-soft tissue interfaces [

72].

3.6. Post-Processing and Stabilization

Regardless of the production method, collagen stabilization is essential for maintaining structural integrity and regulating degradation. Chemical crosslinking agents establish covalent connections within the collagen matrix and enhance mechanical strength. When properly optimized, these agents can produce stable and biocompatible scaffolds; however, excessive crosslinking may impair cellular infiltration or excessively slow degradation. Physical approaches, such as ultraviolet irradiation, dehydrothermal treatment, or low-pressure plasma, as well as enzymatic crosslinking, present safer alternatives with a lower risk of cytotoxicity [

69]. Surface modifications can influence hydrophilicity, enhance protein adsorption, or modulate the first cellular response. Sterilization procedures (gamma irradiation, ethylene oxide, supercritical CO₂) should be used to protect both the mineral phase and the collagen matrix, as too harsh conditions may cause collagen denaturation or changes in HAp crystallinity.

Cross-linking and post-processing steps also influence the release profiles of antimicrobial agents, including essential oils, allowing for sustained therapeutic concentrations while avoiding overly concentrated initial release.

4. Antimicrobial Functionalization Strategies

Microbial infection remains one of the main causes of delayed wound healing and is one of the main determinants of chronicity, especially in diabetic ulcers, burns and post-surgical wounds. Although HAp-Col composites provide an excellent regenerative microenvironment, they require additional antimicrobial functionality to prevent early bacterial adhesion, biofilm formation and recurrent infection. Therefore, various antimicrobial strategies have been incorporated into HAp-Col systems, including metal ions, encapsulated antibiotics and, more recently, natural antimicrobial agents such as essential oils

[24,73,74,75,76].

4.1. Metallic ion Functionalization (Ag⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺)

Metal ions are the oldest and most widely investigated antibacterial additives for composite wound dressings. Their ability to disrupt bacterial membranes, generate oxidative stress, and interfere with protein and DNA synthesis makes them potent, broad-spectrum antimicrobial

[47,77,78].

Silver ions (Ag⁺) have demonstrated potent bactericidal activity at low concentrations and have been widely used in commercial wound dressings. Incorporating Ag⁺ into HAp–Col composites enable controlled ionic release while preserving biocompatibility. Silver-loaded collagen scaffolds reduce

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa colonization and shorten the inflammatory phase

[79,80,81,82].

Zinc ions (Zn²⁺) have a dual effect - both as an antimicrobial effect and as a support for epithelialization and collagen remodeling

[83]. Zn²⁺-substituted hydroxyapatite boosts the growth of new blood vessels and speeds up the healing of infected wounds

[77].

Copper ions (Cu²⁺) provide potent bactericidal and antifungal activity and stimulate angiogenesis. Incorporation of Cu²⁺-doped HAp into collagen matrices improves vascularization and combats biofilms

[84,85,86].

4.2. Antibiotic-Loaded Hydroxyapatite–Collagen Composites

Before natural antimicrobials were considered, antibiotics were the main strategy for functionalizing collagen-based wound dressings

[69]. Their incorporation into HAp-Col scaffolds aimed to achieve controlled localized release, necessary to prevent cytotoxic spikes, maintain therapeutic concentrations at the wound interface, and reduce the likelihood of antimicrobial resistance

[87]. A wide range of antibiotics—including tetracycline, gentamicin, vancomycin, and ciprofloxacin—have been successfully incorporated into collagen sponges, Hap-Col composite scaffolds, hydrogels, and electrospun fibrous mats

[87]. Within these systems, hydroxyapatite frequently acts as an additional reservoir capable of retaining and gradually releasing the active molecule, providing a more sustained release profile than collagen alone. Such composites are effective in preventing early bacterial attachment, disrupting biofilm formation, and maintaining a microenvironment that supports tissue regeneration

[88]. Antibiotics added to the HAp-Col composites do not prevent cells from sticking together or growing, meaning the scaffold can function both as a structural guide for healing and as a localized way to deliver antibiotics

[89]. This local delivery also minimizes systemic exposure and lessens the likelihood of adverse effects associated with high-dose systemic therapy.

4.3. Natural Antimicrobial Agents: Essential Oils as Bioactive Functional Additives

As concerns about antibiotic resistance, cytotoxicity, and the need for repeated doses have increased, people have begun to pay more attention to natural antimicrobial agents, especially essential oils from plants

[90]. These chemicals have a wide range of antibacterial actions, combat biofilms, function as antioxidants, and have great potential to reduce inflammation

[74]. Their complex chemical composition makes them less likely to cause microbial resistance and they work very well with both collagen and hydroxyapatite, making them good candidates for use in composite wound dressings

[76,91,92]. Essential oils become more stable and last longer at the wound site when added to HAp-Col sponges, hydrogels, films, or nanofibrous mats

[35,93]. This is because their volatility is reduced and their release is better controlled. Many essential oils work in different ways (they can break down microbial membranes, make them more permeable, and modify the inflammatory response by decreasing levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines)

[19]. Their ability to combat free radicals helps speed healing by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (which would otherwise slow it down). These effects make essential oils seem like good natural alternatives or additions to antibiotics in hydroxyapatite-collagen composite wound dressings.

4.4. Essential Oils Investigated in Hydroxyapatite–Collagen Composite Dressings

A growing number of essential oils have been explored as functional additives in hydroxyapatite-collagen systems due to their synergistic antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties

[91,94]. These oils differ in chemical composition and biological profile, but most share the ability to disrupt bacterial membranes, suppress inflammatory signaling, and support early stages of tissue regeneration

[95,96,97]. When incorporated into HAp-Col sponges, hydrogels, films, or electrospun mats, their stability is greatly improved; the collagen network reduces volatility, while the mineral phase moderates release and helps maintain bioactive concentrations at the wound interface.

Among the best-documented examples, Lavender oil (

Lavandula angustifolia) has repeatedly demonstrated the ability to accelerate reepithelialization, modulate the inflammatory response, and enhance fibroblast proliferation

[98,99]. These effects make it excellent for surgical wounds or burns that are not too deep, where early epithelial cover is very important. Tea tree oil (

Melaleuca alternifolia) is very effective against bacteria, especially against methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus, and because it can stop biofilm formation in contaminated wounds

[29,100,101,102]. Its addition to collagen-based matrices has allowed the creation of composite dressings that can reduce the number of germs without affecting cytocompatibility. Cinnamon oil (

Cinnamomum verum) has a distinct profile, with strong antibacterial and antioxidant properties that can also help with the production of granulation tissue and the deposition of collagen

[103,104,105,106]. This dual antimicrobial and pro-regenerative action recommends it for infected or slow-healing wounds. Basil oil (

Ocimum basilicum), which is rich in linalool and other phenylpropanoids, has been shown to reduce inflammation and kill germs in many preclinical models. It also helps wounds heal faster and re-epithelialize

[22,23,105,107]. Thyme oil (

Thymus vulgaris), mostly composed of thymol and carvacrol, has demonstrated efficacy in diminishing oxidative stress, promoting angiogenesis, and facilitating all stages of the healing cascade

[30,34,108]. In similar uses, oregano oil (

Origanum vulgare) has strong antibacterial and antifungal properties, which makes it a good choice for chronic wounds with a combination of different types of bacteria

[31,109,110,111,112]. Clove oil (

Syzygium aromaticum), which has a lot of eugenols in it, is an antibacterial, antioxidant, and mild pain reliever

[113,114]. In composite scaffolds, it lowers the number of microbes while also alleviating local pain. Rosemary (

Rosmarinus officinalis), lemongrass (

Cymbopogon citratus), and peppermint (

Mentha piperita) are other oils that have further functional benefits. Rosemary oil improves the flow of oxygen to tissues and has strong antioxidant properties, which help cells respond quickly to ischemic or stressful wounds

[115,116]. Lemongrass oil works against a wide spectrum of germs, including

S. aureus,

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa and can lessen oxidative damage by lowering reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxidation

[117]. Peppermint oil has antibacterial properties as well as a cooling and pain-relieving impact that may help with irritation or pain in inflamed tissues

[75,118].

Table 1.

Antimicrobial functionalization strategies in HAp–Col composite dressings.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial functionalization strategies in HAp–Col composite dressings.

| Category |

Mechanism of action |

Advantages in HAp–Col dressings |

Limitations / risks |

Representative essential

examples

|

References |

|

Metallic ions(Ag⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺)

|

Disrupt bacterial membranes

Generate ROS

Interfere with DNA/protein synthesis |

Strong, broad antimicrobial activity

Effective at low concentrations

Synergistic with HAp ionic exchange |

Potential cytotoxicity at high doses

Risk of delayed healing if overdosed

May alter collagen stability |

Ag⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺ doped HAp integrated into collagen sponges/films |

[81,82,119,120,121,122,123] |

|

Encapsulated antibiotics(gentamicin, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline)

|

Inhibit cell wall synthesis

Block protein synthesis

Prevent bacterial replication & biofilm formation |

Strong early infection control

Tunable, localized release

Reduced systemic toxicity

Widely validated clinically |

Risk of resistance development

Thermal/solvent sensitivity

Possible burst release

Narrow spectrum compared with EOs |

Gentamicin-loaded HAp–Col sponges; vancomycin-loaded nanofibers; ciprofloxacin hydrogels |

[87,88,89,90] |

|

Essential oils (Lavender, Tea tree, Cinnamon, Basil, Thyme, Oregano, Clove, Rosemary, Lemongrass, |

Membrane disruption

Anti-biofilm, anti-quorum sensing

Anti-inflammatory

Antioxidant |

Broad-spectrum, multi-target

Low risk of resistance

Combine antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative effects

Good compatibility with collagen and HAp |

|

|

[34,108,113,115,116,117,118,124]) |

These essential oils work together to create a wide range of bioactivities that work well with the structural and osteoconductive properties of hydroxyapatite–collagen composites. Their integration into composite dressings represents a promising strategy for addressing infection, modulating inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration in both acute and chronic wounds. It works as an analgesic, antibacterial, and a cooling agent. It also makes inflamed wounds less painful.

Together, metallic ions, antibiotic encapsulation and essential oil incorporation form a multi-layered antimicrobial strategy for HAp–Col composite wound dressings. While metallic ions and antibiotics provide strong, immediate antimicrobial action, essential oils introduce additional antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative effects, aligning well with modern trends toward multifunctional, bioactive wound care materials.

5. Clinical Applications and Current Limitations

HAp-Col composite materials have gained considerable attention in preclinical research due to the way they combine structural reinforcement with biological functionality. Their dual organic-inorganic composition offers advantages for skin repair, chronic wound management, and regeneration of interfaces where soft tissue meets mineralized structures. Although numerous in vitro and in vivo studies support their therapeutic potential, translation into routine clinical use remains limited. Currently, progress is hampered by the small number of standardized clinical investigations, the complexity of composite biomaterial regulations, and the challenges of scaling up laboratory protocols to industrial manufacturing.

5.1. Clinical Applications in Soft Tissue Wound Healing

Collagen-based dressings are already used clinically for burns, ulcers and surgical wounds, and the addition of hydroxyapatite broadens their applicability to lesions where mechanical stability and enhanced bioactivity are required. HAp-Col composites support fibroblast attachment, stimulate angiogenesis, maintain a moist wound environment and accelerate granulation tissue development. Their interconnected porosity is suitable for conditions characterized by poor healing, such as diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers or partial burns. In these situations, the mineral phase strengthens the scaffold against shrinkage or collapse, while the collagen network facilitates cell migration and extracellular matrix deposition. Functionalization with bioactive molecules - be they growth factors, ions or essential oils - further enhances the antimicrobial and immunomodulatory profile of these composite materials. Preliminary in vivo studies in animal models consistently report faster re-epithelialization, higher collagen density, and improved tissue organization compared to collagen-only dressings. These observations suggest that HAp-Col composites could serve as a new generation of active wound dressings, especially for chronic or contaminated wounds.

5.2. Applications at the Bone–Soft Tissue Interface

Beyond skin repair, HAp-Col composites have been examined as regenerative patches for wounds involving periosteal exposure or defects where soft tissue needs to integrate with the underlying bone [

125]. Their hybrid structure is advantageous in situations such as traumatic injuries with exposed bone, craniofacial and periodontal defects, post-resection tumor cavities, or chronic osteomyelitis. In these cases, hydroxyapatite contributes to osteoconductivity and provides mineral support that guides bone growth, while collagen supports revascularization and organization of newly formed soft tissues. In periodontal applications, mineralized collagen membranes have demonstrated improved defect stability and enhanced new bone formation compared to membranes made of collagen alone [

126]. Such results highlight the need and importance of a composite approach for covering tissue compartments that differ significantly in terms of mechanical stress and biological behavior.

5.3. Lack of Standardized Clinical Trials

Despite encouraging preclinical evidence, standardized clinical trials evaluating HAp-Col wound dressings are rare. The field is fragmented by substantial variability in composite formulations, including the source and purity of collagen, the crystallinity and Ca/P ratio of hydroxyapatite, and the degree of cross-linking. Differences in sterilization protocols, storage conditions, and definitions of clinical endpoints complicate comparison of study results. Most of the available clinical data come from small case series, mixed patient populations, or from applications that focus primarily on bone regeneration rather than cutaneous wound healing. Rigorous, late-stage clinical trials based on harmonized definitions of chronic wounds, standardized imaging and histological assessments, and long-term monitoring of safety and integration are needed to advance the technology. Without such trials, regulatory approval will remain slow, and widespread clinical adoption will continue to lag behind laboratory advances.

5.4. Industrial and Manufacturing Limitations

Scaling HAp-Col composites from laboratory prototypes to industrial products presents more challenges. Natural collagen exhibits batch-to-batch variability, depending on the species, extraction method, and purification process. Hydroxyapatite behaves similarly, with particle size, stoichiometry, and crystallinity strongly influencing the reproducibility of the final material. Achieving consistent porosity, mechanical properties, and loading efficiency of antimicrobial or bioactive molecules requires tight process control and validated manufacturing protocols. Sterilization is another critical bottleneck. Collagen is particularly sensitive to gamma irradiation and high temperatures, while HAp can undergo phase transformations if exposed to inappropriate sterilization conditions. Identifying sterilization methods that preserve both organic and inorganic components—while maintaining release kinetics for incorporated agents—remains essential. Regulatory pathways add further complexity. Composite dressings that combine a biological matrix, a mineral phase, and antimicrobial compounds are often classified as combination devices, which require extensive data on biocompatibility, mechanics, degradation, and stability. Cost and storage stability also influence feasibility: cross-linking agents, mineral precursors, and encapsulated essential oils affect shelf life and increase the cost of large-scale production. Taken together, these limitations explain the current gap between the strong experimental promise of HAp-Col composites and their modest clinical penetration. The transition to routine use will require coordinated efforts to standardize manufacturing parameters, refine sterilization strategies, develop predictive release models, and conduct well-structured clinical trials. Only through such measures can hydroxyapatite-collagen composite dressings fully transition from experimental platforms to reliable therapeutic tools in contemporary wound care.

6. Discussion

The growing number of research articles on hydroxyapatite-collagen composites indicates substantial progress in the field, along with persistent obstacles in translating these biomaterials for clinical use. A consistent finding across multiple investigations is that the efficacy of HAp-Col systems is significantly influenced by the quality of the organic-inorganic interface. In situ mineralization and biomimetic processes produce composites with superior mineral dispersion and improved interfacial bonding compared to basic physical mixtures, leading to increased mechanical stability and bioactivity [

127,

128]. Small variations in the Ca/P ratio, crystallinity, or collagen source can influence degradation behavior and cellular responses, complicating comparisons across studies and impacting reproducibility [

129]

.

Antimicrobial functionalization exemplifies a domain where promising outcomes are accompanied by significant uncertainties. Metal ions, including Ag⁺, Zn²⁺, and Cu²⁺, effectively disrupt bacterial membranes and inhibit early colonization; however, their limited therapeutic windows raise concerns regarding cytotoxicity [

130]. Antibiotic-loaded composites exhibit significant advantages in infected wound models, such as decreased biofilm formation and enhanced tissue organization [

131]; however, their application is limited by resistance patterns and regulatory requirements for controlled release.

Essential oils present a significant alternative due to their synergistic antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. Lavender, thyme, basil, cinnamon, rosemary, oregano, and tea tree oils demonstrate measurable benefits in wound healing, including accelerated re-epithelialization and disruption of resistant

Staphylococcus aureus biofilms [

19]. However, most of the EO-based evidence is still in the preclinical stage, and significant questions remain concerning sterilization stability, long-term release kinetics, and interactions with mineral phases. Furthermore, numerous

in vivo studies utilize acute rodent models, which fail to adequately replicate the complexity of chronic human wounds.

Clinical data regarding HAp–Col dressings are limited. While mineralized collagen matrices have demonstrated efficacy in bone and periodontal direct wound healing studies are restricted to small sample sizes or individual case reports [

69]. The variability in composite formulations, especially regarding mineral fraction, porosity, and cross-linking, limits the capacity to generalize findings. This gap highlights the necessity for standardized methodologies, harmonized clinical endpoints, and multicenter trials.

Manufacturing difficulties further constrain translation. Natural collagen demonstrates variability across batches influenced by species, extraction methods, and purity levels, whereas the properties of HAp, including stoichiometry and crystallinity, necessitate meticulous control to maintain consistency [

132,

133,

134]. Sterilization presents a specific challenge: collagen is susceptible to irradiation, while hydroxyapatite may experience phase transformation if not treated correctly. Creating essential-oil formulations that are resistant to sterilization, along with effective cross-linking strategies is essential for large-scale production.

These findings indicate a field that is scientifically advanced yet fragmented in terms of technology and clinical application. The potential of HAp–Col composites reside not in a singular formulation but in their versatility as a platform for multimodal wound therapies. Future advancements will rely on the integration of advanced fabrication methods with standardized preclinical testing, as well as the development of scalable and reproducible manufacturing processes. The outlined steps suggest that the significant experimental potential of HAp–Col dressings could be effectively converted into dependable clinical instruments for the management of complex wounds.

7. Future Perspectives

Hydroxyapatite–collagen composite wound dressings are undergoing significant innovation due to advancements in fabrication techniques, enhanced functionalization, and sustainable material sourcing. Ongoing research aims to connect experimental prototypes with clinically applicable technologies, highlighting several strategic directions that are crucial for the advancement of next-generation regenerative dressings.

7.1. Integration with 3D printing and bioprinting

Additive manufacturing integration into HAp–Col systems is transforming the design of wound dressings. Three-dimensional printing enables the precise fabrication of constructs with customizable geometry, porosity, and mechanical properties [

135,

136]. Collagen-based inks, enhanced with nano-hydroxyapatite, can be extruded into patient-specific architectures. Bioprinting further expands these capabilities by allowing for the precise placement of cells, growth factors, or antimicrobial components within the scaffold [

137]. Personalized structures show significant potential for addressing irregular wounds, bone–soft tissue interfaces, and lesions that conventional planar dressings fail to adequately support.

7.2. Nanostructuring Strategies Targeting Angiogenesis

A secondary area of research focuses on the development of nanoscale features that promote vascularization [

138,

139,

140]. Aligned nanofibers, surface nanopatterns, and mineral nanocrystals enhance endothelial adhesion, and migration, which are essential for the regeneration of ischemic or chronic wounds. Substituted forms of hydroxyapatite, including copper- or silicon-doped variants, demonstrate significant potential due to their ability to release ions that directly affect angiogenic pathways [

68,

141]. Nanostructured environments enhance oxygen diffusion and regulate early inflammatory responses, providing a comprehensive strategy for facilitating wound repair.

7.3. Cryogels and Body-Temperature Hydrogels

To treat various wound types, it is necessary to use soft, highly hydrated systems. Cryogels, produced via freeze–thaw processes, exhibit extensive interconnecting pores alongside elasticity and rapid rehydration, rendering them appropriate for exudative or cavitary lesions [

63,

64]. Thermosensitive hydrogels, which experience sol-gel transition at physiological temperatures, provide the benefit of injectability and are capable of filling deep or tunneling wounds that are challenging to access [

142]. The integration of hydroxyapatite and essential oils into these matrices facilitates sustained release profiles, maintains moisture balance, and enhances mechanical resilience under physiological conditions.

7.4. Multifunctional Hybrid Systems

One goal for future HAp-Col systems is to incorporate many regenerative and antibacterial mechanisms into one cohesive structure. Synergistic effects, fast microbial suppression, and simultaneous stimulation of osteogenic and angiogenic responses may be achieved by combining essential oils with metallic nanoparticles (e.g., silver, zinc oxide, copper oxide) or doped bioceramics [

122,

143]. Hybrid systems target multiple biological mechanisms, such as membrane disruption, oxidative stress pathways, and mineral signaling, potentially playing a critical role in the management of chronically infected or structurally complex wounds.

7.5. Smart and Stimuli-Responsive Release Systems

Another interesting area of research is the development of stimuli-responsive matrices that may adjust their release behavior according on the wound's biochemical circumstances

[144]. Dressings designed to react to local pH alterations, oxidative stress, or enzymatic activity can release essential oils, metallic ions, or other active compounds only when necessary, thereby minimizing premature depletion and decreasing cytotoxicity. On-demand systems are particularly pertinent for chronic wounds, where variations in inflammation, bacterial load, and exudate composition necessitate a dynamic therapeutic strategy

[145].

7.6. Translational Models and Preclinical Validation

The results of the experiments are promising, but further thorough preclinical testing is necessary before they can be used in clinical practice. If we want to know how HAp-Col composites react in real-life scenarios, we need models that simulate wounds caused by diabetes, ischemia, or polymicrobials. Additionally, it is important to consider the mechanical durability under physiological loads, the consistency between production batches, and the long-term stability after sterilization. Enhanced regulatory frameworks, standardized outcome measures, and harmonized study designs will expedite approvals and enable meaningful comparisons among emerging technologies.

7.7. Sustainable Manufacturing and Green Biomaterial Sourcing

When creating new biomaterials, sustainability is becoming an increasingly important factor. To lessen their effect on the environment and to limit their usage of materials obtained from animals, which provide a greater immunogenic risk, future techniques will likely rely more on collagen derived from marine or agricultural by-products. Similarly, there is a growing interest in environmentally friendly hydroxyapatite synthesis methods that use biomimetic precipitation techniques or plant extracts [

146,

147]. As an alternative to traditional chemical agents, natural cross-linkers like genipin or polyphenols are safer, more sustainable, and help make products that are more biocompatible and industrially efficient.

7.8. Outlook

In the future, HAp-Col composite dressings may serve as platforms for individualized and multipurpose wound treatment thanks to improvements in fabrication methods, functionalization strategies, and environmentally friendly production methods. The integration of 3D bioprinting, nanostructuring, hybrid antimicrobial systems, and intelligent release mechanisms provides a means to develop dressings that can dynamically adjust to the wound environment while facilitating effective tissue regeneration. The ongoing integration of scientific, clinical, and industrial skills will be essential for transforming these advancements into dependable medical devices that may meet the unmet demands of acute and chronic wound management.

8. Conclusions

Hydroxyapatite–collagen composite dressings are a highly promising category of biomaterials for advanced wound treatment. Their hybrid structure integrates the biological compatibility and remodeling capability of collagen with the mechanical reinforcement and ion-mediated bioactivity of hydroxyapatite. When functionalized with antimicrobial agents, such as metallic ions, medicines, or essential oils, these materials can concurrently tackle infection management, inflammatory modulation, and tissue regeneration.

Recent advancements in fabrication strategies have facilitated the creation of various architectures, including porous sponges, nanofibrous membranes, hydrogels, laminated structures, and patient-specific 3D-printed constructs. These systems demonstrate enhanced cellular adhesion, optimized degradation profiles, and the capacity to sustain a regenerative microenvironment. Essential oils enhance the therapeutic potential of composites by exhibiting broad-spectrum antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and antioxidant properties.

Notwithstanding these encouraging advancements, considerable obstacles persist. Clinical studies are insufficient, manufacturing protocols remain unstandardized, and changes induced by sterilization may compromise both mineral and organic phases. Chronic wound physiology, characterized by ischemia, recurrent infection, oxidative stress, and systemic comorbidities, necessitates the development of more advanced preclinical models that accurately reflect patient conditions.

Nanostructuring, bioprinting, stimuli-responsive release mechanisms, and sustainable processing are probably going to be the defining characteristics of the next innovation wave. By bringing together researchers in materials science, microbiology, wound biology, and regulatory science, HAp-Col composites could one day become smart, individualized wound care platforms that can handle the mechanistic and biological difficulties of complicated tissue restoration.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.R. and B.R.D.; methodology, A.R., and A.I.B.; software, D.S.; validation, A.R., A.I.B. and B.R.D.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, D.S.; resources, B.R.D.; data curation, A.I.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.R. and D.S.; visualization, B.R.D.; supervision, B.R.D.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Program for Research of the National Association of Technical Universities—GNAC ARUT 2023, contract 47/2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data reported in this manuscript are available upon official request to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J Dent Res 2010, 89, 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xu, Q.; Hao, R.; Wang, C.; Que, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Chang, J. Multi-Functional Wound Dressings Based on Silicate Bioactive Materials. Biomaterials 2022, 287, 121652. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, D.; Dai, K.; Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Li, H.; Tang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Recent Progress of Collagen, Chitosan, Alginate and Other Hydrogels in Skin Repair and Wound Dressing Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 208, 400–408. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Zheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Li, K. Bioactive Glasses: Advancing Skin Tissue Repair through Multifunctional Mechanisms and Innovations. Biomater Res 2025, 29. [CrossRef]

- Negut, I.; Ristoscu, C. Bioactive Glasses for Soft and Hard Tissue Healing Applications—A Short Review. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13.

- Al-Naymi, H.A.S.; Al-Musawi, M.H.; Mirhaj, M.; Valizadeh, H.; Momeni, A.; Danesh Pajooh, A.M.; Shahriari-Khalaji, M.; Sharifianjazi, F.; Tavamaishvili, K.; Kazemi, N.; et al. Exploring Nanobioceramics in Wound Healing as Effective and Economical Alternatives. Heliyon 2024, 10.

- Wang, S.; Neufurth, M.; Schepler, H.; Tan, R.; She, Z.; Al-Nawas, B.; Wang, X.; Schröder, H.C.; Müller, W.E.G. Acceleration of Wound Healing through Amorphous Calcium Carbonate, Stabilized with High-Energy Polyphosphate. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 494. [CrossRef]

- Heidari, R.; Assadollahi, V.; Shakib Manesh, M.H.; Mirzaei, S.A.; Elahian, F. Recent Advances in Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Formulations and Drug Delivery for Wound Healing. Int J Pharm 2024, 665.

- Manzano, M.; Vallet-Regí, M. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in Biomedicine: Advances and Prospects. Advanced Materials 2025.

- Xue, L.; Deng, T.; Guo, R.; Peng, L.; Guo, J.; Tang, F.; Lin, J.; Jiang, S.; Lu, H.; Liu, X.; et al. A Composite Hydrogel Containing Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Loaded With Artemisia Argyi Extract for Improving Chronic Wound Healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Moreno Florez, A.I.; Malagon, S.; Ocampo, S.; Leal-Marin, S.; Gil González, J.H.; Diaz-Cano, A.; Lopera, A.; Paucar, C.; Ossa, A.; Glasmacher, B.; et al. Antibacterial and Osteoinductive Properties of Wollastonite Scaffolds Impregnated with Propolis Produced by Additive Manufacturing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23955. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, T.; Fauzi, M.B.; Lokanathan, Y.; Law, J.X. The Role of Calcium in Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22.

- Abbas, S.F.; Haider, A.J.; Al-Musawi, S.; Abbas, E.M.; Alnayli, R.S.; Taha, B.A.; Choubani, M.; Arsad, N.; Ibrahim, H.I. Optimizing Wound Healing with Antibacterial Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: A Comparative Analysis of Efficacy and Biological Mechanisms. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2025, 105. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.H.; Azooz, E.A.; Al-Mulla, E.A.J. Nanoparticles-Assisted Wound Healing: A Review. Nano Biomed Eng 2023, 15, 425–435.

- Abbas, S.F.; Haider, A.J.; Al-Musawi, S. Antimicrobial and Wound Healing Effects of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles-Enriched Wound Dressing. Nano 2023, 18. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.; Thirupathi, A.; Corrêa, M.E.A.B.; Gu, Y.; Silveira, P.C.L. The Use of Metallic Nanoparticles in Wound Healing: New Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15376. [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, S.; Padma, V.V.; Santhini, E. Wound Dressings - A Review. BioMedicine (Netherlands) 2015, 5, 24–28. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, J.S.; Matthews, K.H.; Stevens, H.N.E.; Eccleston, G.M. Wound Healing Dressings and Drug Delivery Systems: A Review. J Pharm Sci 2008, 97, 2892–2923. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita, D.; Robu, A.; Antoniac, A.; Antoniac, I.; Ditu, L.M.; Raiciu, A.-D.; Tomescu, J.; Grosu, E.; Saceleanu, A. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Some Plant Essential Oils against Four Different Microbial Strains. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9482. [CrossRef]

- Ghica, M.V.; Albu, M.G.; Kaya, D.A.; Popa, L.; Öztürk, Șevket; Rusu, L.C.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.; Chelaru, C.; Albu, L.; Meghea, A.; et al. The Effect of Lavandula Essential Oils on Release of Niflumic Acid from Collagen Hydrolysates. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2016, 33, 1325–1330. [CrossRef]

- Garzoli, S.; Abdali, Y. El; Agour, A.; Allali, A.; Bourhia, M.; Moussaoui, A. El; Eloutassi, N.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Alzahrani, A.; Ouahmane, L.; et al. Lavandula Dentata L.: Phytochemical Analysis, Antioxidant, Antifungal and Insecticidal Activities of Its Essential Oil. 2022, 11, 311. [CrossRef]

- Fachriyah, E.; Wibawa, P.J.; Awaliyah, A. Antibacterial Activity of Basil Oil (Ocimum Basilicum L) and Basil Oil Nanoemulsion. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; Institute of Physics Publishing, June 22 2020; Vol. 1524.

- Ali Khan, B.; Ullah, S.; Khan, M.K.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Braga, V.A. Formulation and Evaluation of Ocimum Basilicum-Based Emulgel for Wound Healing Using Animal Model. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2020, 28, 1842–1850. [CrossRef]

- Robu, A.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Antoniac, A.; Kaya, D.A.; Coman, A.E.; Marin, M.M.; Ciocoiu, R.; Constantinescu, R.R.; Antoniac, I. The Influence of Basil and Cinnamon Essential Oils on Bioactive Sponge Composites of Collagen Reinforced with Hydroxyapatite. Materials 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- El Atki, Y.; Aouam, I.; El Kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Nayme, K.; Timinouni, M.; Lyoussi, B.; Abdellaoui, A. Antibacterial Activity of Cinnamon Essential Oils and Their Synergistic Potential with Antibiotics. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 2019, 10, 63. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.A.; Stephens, J.C. A Review of Cinnamaldehyde and Its Derivatives as Antibacterial Agents. Fitoterapia 2019, 139, 104405. [CrossRef]

- Haesler, E.; Carville, K. WHAM Evidence Summary: Effectiveness of Tea Tree Oil in Managing Chronic Wounds. WCET Journal 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.; Younis, A.; Javed, T.; Akram, A.; Ahsan, M.; Shabbir, R.; Ali, M.M.; Tahir, A.; El-ballat, E.M.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; et al. River Tea Tree Oil: Composition, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities, and Potential Applications in Agriculture. Plants 2021, 10.

- Labib, R.M.; Ayoub, I.M.; Michel, H.E.; Mehanny, M.; Kamil, V.; Hany, M.; Magdy, M.; Moataz, A.; Maged, B.; Mohamed, A. Appraisal on the Wound Healing Potential of Melaleuca Alternifolia and Rosmarinus Officinalis L. Essential Oil-Loaded Chitosan Topical Preparations. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219561. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Barati, A.; Tonelli, A.E.; Hamedi, H. Chitosan-Based Hydrogels Loading with Thyme Oil Cyclodextrin Inclusion Compounds: From Preparation to Characterization. Eur Polym J 2020, 122. [CrossRef]

- Berechet, M.D.; Gaidau, C.; Miletic, A.; Pilic, B.; Râpă, M.; Stanca, M.; Ditu, L.M.; Constantinescu, R.; Lazea-Stoyanova, A. Bioactive Properties of Nanofibres Based on Concentrated Collagen Hydrolysate Loaded with Thyme and Oregano Essential Oils. Materials 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pandur, E.; Micalizzi, G.; Mondello, L.; Horváth, A.; Sipos, K.; Horváth, G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Thyme (Thymus Vulgaris L.) Essential Oils Prepared at Different Plant Phenophases on Pseudomonas Aeruginosa LPS-Activated THP-1 Macrophages. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.F.; Durço, A.O.; Rabelo, T.K.; Barreto, R. de S.S.; Guimarães, A.G. Effects of Carvacrol, Thymol and Essential Oils Containing Such Monoterpenes on Wound Healing: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2019, 71, 141–155.

- Folle, C.; Díaz-Garrido, N.; Mallandrich, M.; Suñer-Carbó, J.; Sánchez-López, E.; Halbaut, L.; Marqués, A.M.; Espina, M.; Badia, J.; Baldoma, L.; et al. Hydrogel of Thyme-Oil-PLGA Nanoparticles Designed for Skin Inflammation Treatment. Gels 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liakos, I.; Rizzello, L.; Scurr, D.J.; Pompa, P.P.; Bayer, I.S.; Athanassiou, A. All-Natural Composite Wound Dressing Films of Essential Oils Encapsulated in Sodium Alginate with Antimicrobial Properties. Int J Pharm 2014, 463, 137–145. [CrossRef]

- Buriti, B.M.A. de B.; Figueiredo, P.L.B.; Passos, M.F.; da Silva, J.K.R. Polymer-Based Wound Dressings Loaded with Essential Oil for the Treatment of Wounds: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17.

- Borges, J.C.; de Almeida Campos, L.A.; Kretzschmar, E.A.M.; Cavalcanti, I.M.F. Incorporation of Essential Oils in Polymeric Films for Biomedical Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 269, 132108. [CrossRef]

- Haesler, E.; Carville, K. WHAM Evidence Summary: Effectiveness of Tea Tree Oil in Managing Chronic Wounds. WCET Journal 2021, 41. [CrossRef]

- Kennewell, T.L.; Mashtoub, S.; Howarth, G.S.; Cowin, A.J.; Kopecki, Z. Antimicrobial and Healing-Promoting Properties of Animal and Plant Oils for the Treatment of Infected Wounds. Wound Practice and Research 2019, 27, 175–183. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, F.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Ahmad, T.; Akram, M.A.; safdar, A.; Butt, M.S.; Noor, T.; Sher, F. Synthesis and Characterization of PVA/Starch Hydrogel Membranes Incorporating Essential Oils Aimed to Be Used in Wound Dressing Applications. J Polym Environ 2021, 29, 156–174. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Torres, J.E.; Hakim, M.; Babiak, P.M.; Pal, P.; Battistoni, C.M.; Nguyen, M.; Panitch, A.; Solorio, L.; Liu, J.C. Collagen- and Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogels and Their Biomedical Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2021, 146, 100641. [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.M.; Ianchis, R.; Alexa, R.L.; Gifu, I.C.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Savu, D.I.; Popescu, R.C.; Alexandrescu, E.; Ninciuleanu, C.M.; Preda, S.; et al. Development of New Collagen/Clay Composite Biomaterials. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Albu, M.G.; Vladkova, T.G.; Ivanova, I.A.; Shalaby, A.S.A.; Moskova-Doumanova, V.S.; Staneva, A.D.; Dimitriev, Y.B.; Kostadinova, A.S.; Topouzova-Hristova, T.I. Preparation and Biological Activity of New Collagen Composites, Part I: Collagen/Zinc Titanate Nanocomposites. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2016, 180, 177–193. [CrossRef]

- Schyra, P.; Aibibu, D.; Sundag, B.; Cherif, C. Chemical Crosslinking of Acid Soluble Collagen Fibres. Biomimetics 2025, 10.

- Mondal, S.; Park, S.; Choi, J.; Vu, T.T.H.; Doan, V.H.M.; Vo, T.T.; Lee, B.; Oh, J. Hydroxyapatite: A Journey from Biomaterials to Advanced Functional Materials. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2023, 321, 103013. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liao, T.; Lai, L.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Tang, H. Microstructure and Properties of Hydroxyapatite-Containing Ceramic Coatings on Magnesium Alloys by One-Step Micro-Arc Oxidation. Protection of Metals and Physical Chemistry of Surfaces 2022, 58, 552–561. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.L.; Zhang, Z.F.; Min, J.; Yuan, D.; Yu, J.Y.; Yu, P. Beyond Bone Regeneration: Hydroxyapatite’s Emerging Potential in Advanced Wound Management. Mater Today Commun 2025, 48, 113426. [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, S.; Chowdhary, Z.; Rastogi, T. Evaluation and Comparison of Hydroxyapatite Crystals with Collagen Fibrils Bone Graft Alone and in Combination with Guided Tissue Regeneration Membrane. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2019, 23, 234. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, K.; Zhou, T.; Wei, D.; Wu, C.; Ding, J.; Luo, F.; Sun, J.; et al. Enzyme-Mimetic Hydroxyapatite for Diabetic Wound Dressing with Immunomodulation and Collagen Remodeling Functions. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025, 17, 35116–35127. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Tuglu, M.; Özdal-Kurt, F.; Koca, H.; Sarac, A.; Barut, T.; Kazanç, A. The Contribution of Differentiated Bone Marrow Sromal Stem Cell-Loaded Biomaterial to Treatment in Critical Size Defect Model in Rats;

- Sadat-Shojai, M.; Khorasani, M.T.; Dinpanah-Khoshdargi, E.; Jamshidi, A. Synthesis Methods for Nanosized Hydroxyapatite with Diverse Structures. Acta Biomater 2013, 9, 7591–7621. [CrossRef]

- Szcześ, A.; Hołysz, L.; Chibowski, E. Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite for Biomedical Applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2017, 249, 321–330. [CrossRef]

- Alkaron, W.; Almansoori, A.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Hydroxyapatite-Based Natural Biopolymer Composite for Tissue Regeneration. Materials 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Pu’ad, N.A.S.; Koshy, P.; Abdullah, H.Z.; Idris, M.I.; Lee, T.C. Syntheses of Hydroxyapatite from Natural Sources. Heliyon 2019, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bezzi, G.; Celotti, G.; Landi, E.; La Torretta, T.M.G.; Sopyan, I.; Tampieri, A. A Novel Sol–Gel Technique for Hydroxyapatite Preparation. Mater Chem Phys 2003, 78, 816–824. [CrossRef]

- Vladu, A.F.; Albu Kaya, M.G.; Truşcă, R.D.; Motelica, L.; Surdu, V.A.; Oprea, O.C.; Constantinescu, R.R.; Cazan, B.; Ficai, D.; Andronescu, E.; et al. The Role of Crosslinking Agents in the Development of Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Composite Materials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, C.; Gong, H.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, K. Effects of Synthesis Conditions on the Morphology of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles Produced by Wet Chemical Process. Powder Technol 2010, 203, 315–321. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wei, M. Biomineralization of Collagen-Based Materials for Hard Tissue Repair. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1–17.

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3868. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13.

- Katrilaka, C.; Karipidou, N.; Petrou, N.; Manglaris, C.; Katrilakas, G.; Tzavellas, A.N.; Pitou, M.; Tsiridis, E.E.; Choli-Papadopoulou, T.; Aggeli, A. Freeze-Drying Process for the Fabrication of Collagen-Based Sponges as Medical Devices in Biomedical Engineering. Materials 2023, 16.

- Antebi, B.; Cheng, X.; Harris, J.N.; Gower, L.B.; Chen, X.-D.; Ling, J. Biomimetic Collagen–Hydroxyapatite Composite Fabricated via a Novel Perfusion-Flow Mineralization Technique. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2013, 19, 487–496. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Lin, W. An Overview on Collagen and Gelatin-Based Cryogels: Fabrication, Classification, Properties and Biomedical Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 2299. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.C.; Salgado, C.L.; Sahu, A.; Garcia, M.P.; Fernandes, M.H.; Monteiro, F.J. Preparation and Characterization of Collagen-nanohydroxyapatite Biocomposite Scaffolds by Cryogelation Method for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. J Biomed Mater Res A 2013, 101A, 1080–1094. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zheng, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, J. A Bio-Functional Cryogel with Antioxidant Activity for Potential Application in Bone Tissue Repairing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37055. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Sousa, S.R.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Moroni, L.; Monteiro, F.J. A Biocomposite of Collagen Nanofibers and Nanohydroxyapatite for Bone Regeneration. Biofabrication 2014, 6, 035015. [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.Q.; Khan, H. Applications of Co-Axial Electrospinning in the Biomedical Field. Next Materials 2024, 3, 100138. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Sousa, A.; Cunha-Reis, C.; Oliveira, A.L.; Granja, P.L.; Monteiro, F.J.; Sousa, S.R. New Prospects in Skin Regeneration and Repair Using Nanophased Hydroxyapatite Embedded in Collagen Nanofibers. Nanomedicine 2021, 33, 102353. [CrossRef]

- Alberts, A.; Bratu, A.G.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Collagen-Based Wound Dressings: Innovations, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 271. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Li, H. Construction of 3D Bioprinting of HAP/Collagen Scaffold in Gelation Bath for Bone Tissue Engineering. Regen Biomater 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ruan, C.; Niu, X. Collagen-Based Bioinks for Regenerative Medicine: Fabrication, Application and Prospective. Med Nov Technol Devices 2023, 17, 100211. [CrossRef]

- Lemnaru, M.; Albu-Kaya, M.G.; Sonmez, M.; Mitran, V.; Ficai, D.; Ficai, A.; Dragos, G.; Campean, A.; Andronescu, E. Collagen/Hydroxyapatite Bio-Compatible Scaffolds Obtained Through 3D Printing.; August 2018.

- Robu, A.; Georgiana Albu Kaya, M.; Antoniac, A.; Antoniac, I.; Eli Pieptea, E.; Necsulescu, A.; Daniela Raiciu, A.; Eleonora Gherghina, M.; Maria Fratila, A. Collagen-Based Bioactive Wound Dressings Loaded with Basil Essential Oil and Hydroxyapatite. Bull., Series B 87, 2025.

- Gheorghita, D.; Grosu, E.; Robu, A.; Ditu, L.M.; Deleanu, I.M.; Gradisteanu Pircalabioru, G.; Raiciu, A.D.; Bita, A.I.; Antoniac, A.; Antoniac, V.I. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Active Substances in Wound Dressings. Materials 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Robu, A.; Antoniac, A.; Ciocoiu, R.; Grosu, E.; Rau, J. V.; Fosca, M.; Krasnyuk, I.I.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Manescu (Paltanea), V.; Antoniac, I.; et al. Effect of the Antimicrobial Agents Peppermint Essential Oil and Silver Nanoparticles on Bone Cement Properties. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 137. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, I.; Pedram, P.; Moeini, A.; Cerruti, P.; Peluso, G.; Di Salle, A.; Germann, N. Nanotechnology Development for Formulating Essential Oils in Wound Dressing Materials to Promote the Wound-Healing Process: A Review. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mouriño, V.; Cattalini, J.P.; Boccaccini, A.R. Metallic Ions as Therapeutic Agents in Tissue Engineering Scaffolds: An Overview of Their Biological Applications and Strategies for New Developments. J R Soc Interface 2012, 9, 401–419. [CrossRef]

- Sukhodub, L.; Kumeda, M.; Sukhodub, L.; Bielai, V.; Lyndin, M. Metal Ions Doping Effect on the Physicochemical, Antimicrobial, and Wound Healing Profiles of Alginate-Based Composite. Carbohydr Polym 2023, 304, 120486. [CrossRef]

- Pavlík, V.; Sobotka, L.; Pejchal, J.; Čepa, M.; Nešporová, K.; Arenbergerová, M.; Mrózková, A.; Velebný, V. Silver Distribution in Chronic Wounds and the Healing Dynamics of Chronic Wounds Treated with Dressings Containing Silver and Octenidine. The FASEB Journal 2021, 35. [CrossRef]

- Rybka, M.; Mazurek, Ł.; Konop, M. Beneficial Effect of Wound Dressings Containing Silver and Silver Nanoparticles in Wound Healing—From Experimental Studies to Clinical Practice. Life 2022, 13, 69. [CrossRef]

- Khansa, I.; Schoenbrunner, A.R.; Kraft, C.T.; Janis, J.E. Silver in Wound Care—Friend or Foe?: A Comprehensive Review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019, 7, e2390. [CrossRef]

- Nešporová, K.; Pavlík, V.; Šafránková, B.; Vágnerová, H.; Odráška, P.; Žídek, O.; Císařová, N.; Skoroplyas, S.; Kubala, L.; Velebný, V. Effects of Wound Dressings Containing Silver on Skin and Immune Cells. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15216. [CrossRef]

- Vranceanu, D.M.; Ungureanu, E.; Ionescu, I.C.; Parau, A.C.; Pruna, V.; Titorencu, I.; Badea, M.; Gălbău, C. Ștefania; Idomir, M.; Dinu, M.; et al. In Vitro Characterization of Hydroxyapatite-Based Coatings Doped with Mg or Zn Electrochemically Deposited on Nanostructured Titanium. Biomimetics 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yu, T.; Liu, H.; Guan, L.; Li, M.; et al. Strategic Incorporation of Metal Ions in Bone Regenerative Scaffolds: Multifunctional Platforms for Advancing Osteogenesis. Regen Biomater 2025, 12.

- Zhang, Z.; Xue, H.; Xiong, Y.; Geng, Y.; Panayi, A.C.; Knoedler, S.; Dai, G.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Mi, B.; Liu, G. Copper Incorporated Biomaterial-Based Technologies for Multifunctional Wound Repair. Theranostics 2024, 14, 547–570. [CrossRef]

- Spanu, I.; Robu, A.; Antoniac, A.; Corneschi, I.; Manescu (Paltanea), V.; Popescu, L.; Alexandrescu, D. A Bibliometric Analysis of Copper and Antimicrobial Copper Coatings. European Journal of Materials Science and Engineering 2024, 9, 109–124. [CrossRef]

- Cristea (Hohotă), A.-G.; Lisă, E.-L.; Iacob (Ciobotaru), S.; Dragostin, I.; Ștefan, C.S.; Fulga, I.; Anghel (Ștefan), A.M.; Dragan, M.; Morariu, I.D.; Dragostin, O.-M. Antimicrobial Smart Dressings for Combating Antibiotic Resistance in Wound Care. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 825. [CrossRef]

- Almuhanna, Y. Microbial Biofilms as Barriers to Chronic Wound Healing: Diagnostic Challenges and Therapeutic Advances. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 8121. [CrossRef]

- Egawa, S.; Hirai, K.; Matsumoto, R.; Yoshii, T.; Yuasa, M.; Okawa, A.; Sugo, K.; Sotome, S. Efficacy of Antibiotic-Loaded Hydroxyapatite/Collagen Composites Is Dependent on Adsorbability for Treating Staphylococcus Aureus Osteomyelitis in Rats. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2020, 38, 843–851. [CrossRef]

- Robu, A.; Antoniac, A.; Grosu, E.; Vasile, E.; Raiciu, A.D.; Iordache, F.; Antoniac, V.I.; Rau, J. V.; Yankova, V.G.; Ditu, L.M.; et al. Additives Imparting Antimicrobial Properties to Acrylic Bone Cements. Materials 2021, 14, 7031. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.S. do; Tamiasso, R.S.S.; Morais, S.F.M.; Rizzo Gnatta, J.; Turrini, R.N.T.; Calache, A.L.S.C.; de Brito Poveda, V. Essential Oils for Healing and/or Preventing Infection of Surgical Wounds: A Systematic Review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2022, 56. [CrossRef]

- Noura E.; Kamilia A.M. A. The Antibacterial Activity of Nano-Encapsulated Basil and Cinnamon Essential Oils against Certain Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Recovered from Infected Wounds. Novel Research in Microbiology Journal 2021, 5, 1447–1462. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S. Electrospun Nanofibrous Membranes with Essential Oils for Wound Dressing Applications. Fibers and Polymers 2020, 21, 999–1012. [CrossRef]

- Alven, S.; Peter, S.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Enriched with Essential Oils: A Promising Approach for the Treatment of Infected Wounds. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14.

- Dhifi, W.; Bellili, S.; Jazi, S.; Bahloul, N.; Mnif, W. Essential Oils’ Chemical Characterization and Investigation of Some Biological Activities: A Critical Review. Medicines 2016, 3, 25. [CrossRef]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Devecioglu, D.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Capanoglu, E. Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antimycotoxigenic, and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oils: An Updated Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4711. [CrossRef]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents—Myth or Real Alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [CrossRef]

- Predoi, D.; Groza, A.; Iconaru, S.L.; Predoi, G.; Barbuceanu, F.; Guegan, R.; Motelica-Heino, M.S.; Cimpeanu, C. Properties of Basil and Lavender Essential Oils Adsorbed on the Surface of Hydroxyapatite. Materials 2018, 11. [CrossRef]

- Predoi, D.; Iconaru, S.L.; Buton, N.; Badea, M.L.; Marutescu, L. Antimicrobial Activity of New Materials Based on Lavender and Basil Essential Oils and Hydroxyapatite. Nanomaterials 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Faria, L.S.; Santos, L.S.C. A Eficácia Do Óleo Essencial de Melaleuca “Tea Tree” No Tratamento de Feridas Crônicas. Research, Society and Development 2025, 14, e4314749180. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Costantini, S.; De Angelis, M.; Garzoli, S.; Božović, M.; Mascellino, M.T.; Vullo, V.; Ragno, R. High Potency of Melaleuca Alternifolia Essential Oil against Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Molecules 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Karvelas, N.; Samandara, A.; Dragomir, B.R.; Chehab, A.; Panaite, T.; Romanec, C.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Zetu, I.N. Evaluation of Maxillary Molar Distalization Supported by Mini-Implants with the Advanced Molar Distalization Appliance (Amda®): Preliminary Results of a Prospective Clinical Trial. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 6323. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, N.G.; Croda, J.; Simionatto, S. Antibacterial Mechanisms of Cinnamon and Its Constituents: A Review. Microb Pathog 2018, 120, 198–203. [CrossRef]

- Robu, A.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Antoniac, A.; Kaya, D.A.; Coman, A.E.; Marin, M.M.; Ciocoiu, R.; Constantinescu, R.R.; Antoniac, I. The Influence of Basil and Cinnamon Essential Oils on Bioactive Sponge Composites of Collagen Reinforced with Hydroxyapatite. Materials 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- Majdi, C.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Rhourri-Frih, B.; Charrouf, Z.; Barros, L.; Amaral, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical Characterization and Bioactive Properties of Cinnamon Basil (Ocimum Basilicum Cv. ’Cinnamon’) and Lemon Basil (Ocimum × Citriodorum). Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Seyed Ahmadi, S.G.; Farahpour, M.R.; Hamishehkar, H. Topical Application of Cinnamon Verum Essential Oil Accelerates Infected Wound Healing Process by Increasing Tissue Antioxidant Capacity and Keratin Biosynthesis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2019, 35, 686–694. [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, L.P.; Marjanovic-Balaban, Z.R.; Kalaba, V.D.; Stanojevic, J.S.; Cvetkovic, D.J.; Cakic, M.D. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Basil ( Ocimum Basilicum L.) Essential Oil. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2017, 20, 1557–1569. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Shukla, I.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Contreras, M. del M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fathi, H.; Nasrabadi, N.N.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Thymol, Thyme, and Other Plant Sources: Health and Potential Uses. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 32, 1688–1706.

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.; Vazquez-Olivo, G.; Heredia, J. Essential Oils of Oregano: Biological Activity beyond Their Antimicrobial Properties. Molecules 2017, 22, 989. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Dai, T.; Murray, C.K.; Wu, M.X. Bactericidal Property of Oregano Oil Against Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Isolates. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Karadayı, M.; Yıldırım, V.; Güllüce, M. Antimicrobial Activity and Other Biological Properties of Oregano Essential Oil and Carvacrol; 2020;

- Brdjanin, S.; Bogdanovic, N.; Kolundzic, M.; Milenkovic, M.; Golic, N.; Kojic, M.; Kundakovic, T. Antimicrobial Activity of Oregano (Origanum Vulgare L.): And Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.): Extracts. Advanced technologies 2015, 4, 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Iseppi, R.; Truzzi, E.; Sabia, C.; Messi, P. Efficacy and Synergistic Potential of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum Zeylanicum) and Clove (Syzygium Aromaticum L. Merr. & Perry) Essential Oils to Control Food-Borne Pathogens in Fresh-Cut Fruits. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vivcharenko, V.; Trzaskowska, M.; Przekora, A. Wound Dressing Modifications for Accelerated Healing of Infected Wounds. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7193. [CrossRef]

- Miljanović, A.; Grbin, D.; Pavić, D.; Dent, M.; Jerković, I.; Marijanović, Z.; Bielen, A. Essential Oils of Sage, Rosemary, and Bay Laurel Inhibit the Life Stages of Oomycete Pathogens Important in Aquaculture. Plants 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Evangelopoulo, G.; Solomakos, N.; Ioannidis, A.; Pexara, A.; R Burriel, A. A Comparative Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Oregano, Rosemary and Thyme Essential Oils against Salmonella Spp. Biomed Res Clin Pract 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

- Motelica, L.; Ficai, D.; Oprea, O.-C.; Ficai, A.; Ene, V.-L.; Vasile, B.-S.; Andronescu, E.; Holban, A.-M. Antibacterial Biodegradable Films Based on Alginate with Silver Nanoparticles and Lemongrass Essential Oil–Innovative Packaging for Cheese. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2377. [CrossRef]

- Unalan, I.; Slavik, B.; Buettner, A.; Goldmann, W.H.; Frank, G.; Boccaccini, A.R. Physical and Antibacterial Properties of Peppermint Essential Oil Loaded Poly (ε-Caprolactone) (PCL) Electrospun Fiber Mats for Wound Healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Hu, Z.; Shan, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, X. Application of Metal-Organic Frameworks in Infectious Wound Healing. J Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Ma, H.; Yu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, R.; Xiang, Z.; Maria Rommens, P.; Duan, X.; Ritz, U. Multifunctional Metal–Organic Frameworks for Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration. Mater Des 2023, 233, 112252. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Oh, S.; Ong, A.P.; Oh, N.; Liu, Y.; Courtney, H.S.; Appleford, M.; Ong, J.L. Antibacterial and Osteogenic Properties of Silver-Containing Hydroxyapatite Coatings Produced Using a Sol Gel Process. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007, 82, 899–906. [CrossRef]

- Sobczak-Kupiec, A.; Drabczyk, A.; Florkiewicz, W.; Głąb, M.; Kudłacik-Kramarczyk, S.; Słota, D.; Tomala, A.; Tyliszczak, B. Review of the Applications of Biomedical Compositions Containing Hydroxyapatite and Collagen Modified by Bioactive Components. Materials 2021, 14.

- Bardania, H.; Mahmoudi, R.; Bagheri, H.; Salehpour, Z.; Fouani, M.H.; Darabian, B.; Khoramrooz, S.S.; Mousavizadeh, A.; Kowsari, M.; Moosavifard, S.E.; et al. Facile Preparation of a Novel Biogenic Silver-Loaded Nanofilm with Intrinsic Anti-Bacterial and Oxidant Scavenging Activities for Wound Healing. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 6129. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, L.; Hassanzadeh Khankahdani, H.; Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, F. Effect of Aloe Vera Gel Combined with Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) Essential Oil as a Natural Coating on Maintaining Post-Harvest Quality of Peach (Prunus Persica L.) during Storage. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2020, 594, 012008. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X. Preparation and Evaluation of an Injectable HAp/Col I Composite for Promoting Tendon-to-Bone Healing in ACL Reconstruction. Mater Today Bio 2025, 35, 102505. [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Yang, B.-E.; Park, S.-Y.; On, S.-W.; Ahn, K.-M.; Byun, S.-H. Efficacy of Cross-Linked Collagen Membranes for Bone Regeneration: In Vitro and Clinical Studies. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 876. [CrossRef]