Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Distillation of Essential Oils

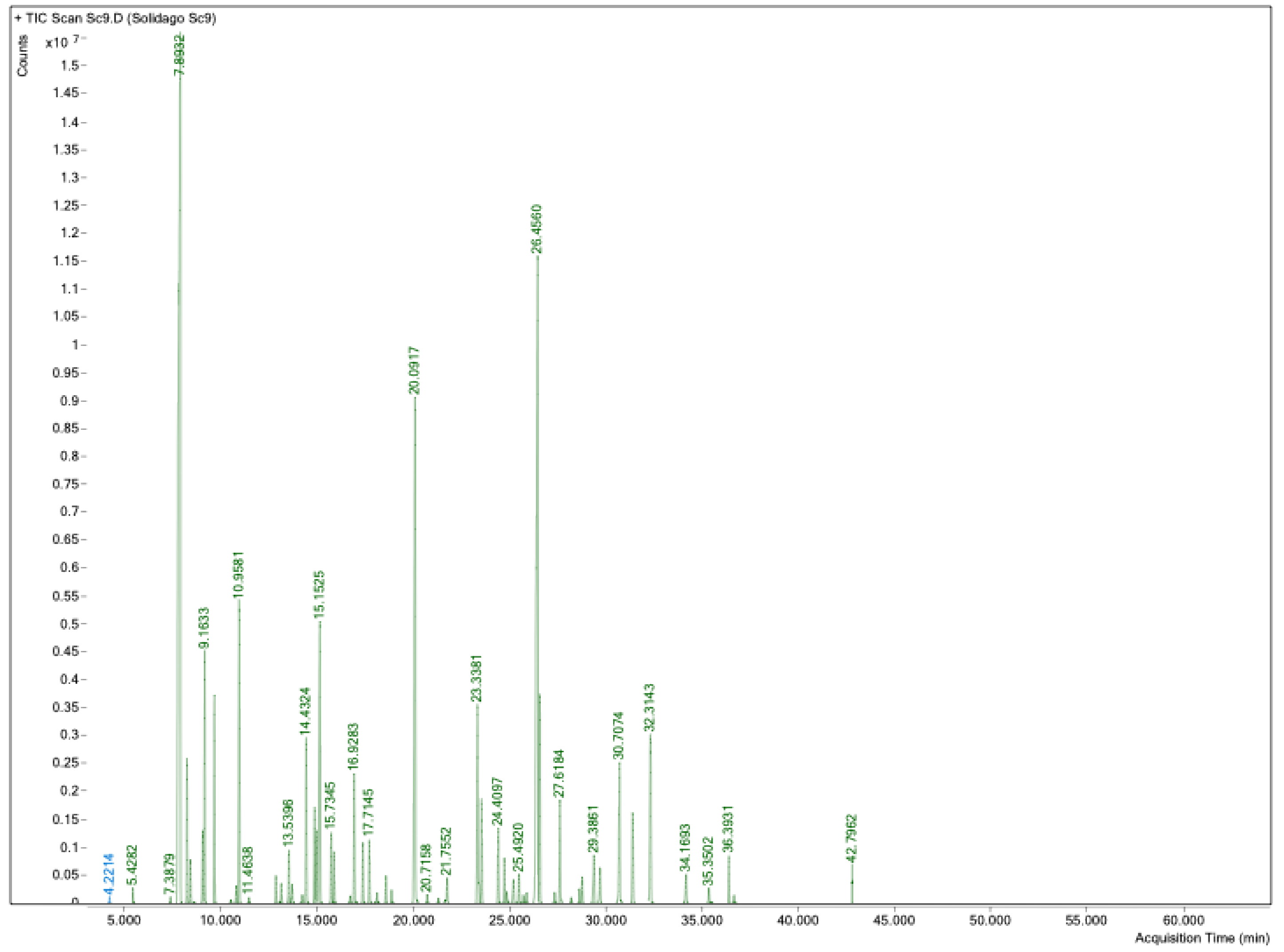

2.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Species Report: Solidago L. Taxonomic Serial No.: 36223. Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

- Estonian Environment Agency Estonian Plant Distribution Atlas 2020; Estonian Environment Agency: Tallinn, Estonia, 2020.

- Bodkin, F.; Bodkin, F. Encyclopaedia Botanica: The Essential Reference Guide to Native and Exotic Plants in Australia 1992.

- Zingel, H.; Muuga, G.; Leht, M.; Kukk, T.; Reier, Ü.; Tuulik, T.; Kuusk, V.; Pihu, S.; Zingel, H.; Oja, T.; et al. Eesti Taimede Määraja (3., Parand. Tr); Eesti Maaülikool: Eesti Loodusfoto, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, R.W.; Chen, S.; Nagy, D.U.; Callaway, R.M. Impacts of Solidago Gigantea on Other Species at Home and Away. Biol Invasions 2015, 17, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljuha, D.; Sladonja, B.; Uzelac Božac, M.; Šola, I.; Damijanić, D.; Weber, T. The Invasive Alien Plant Solidago Canadensis: Phytochemical Composition, Ecosystem Service Potential, and Application in Bioeconomy. Plants 2024, 13, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Gruľová, D.; Baranová, B.; Caputo, L.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Antimicrobial Activity and Chemical Composition of Essential Oil Extracted from Solidago Canadensis L. Growing Wild in Slovakia. Molecules 2019, 24, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelepova, O.; Vinogradova, Y.; Vergun, O.; Grygorieva, O.; Brindza, J. Assessment of Flavonoids and Phenolic Compound Accumulation in Invasive Solidago Canadensis L. in Slovakia. Potr. S. J. F. Sci. 2020, 14, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohne, B.; Dietze, P.; Kitsnik, A. Ravimtaimed: Taskuteatmik: 130 Taimetutvustust, 300 Värvifotot; Egmont Estonia: Tallinn, Estonia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- Koshovyi, O.; Hrytsyk, Y.; Perekhoda, L.; Suleiman, M.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Grytsyk, L.; Yurchyshyn, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A. Solidago Canadensis L. Herb Extract, Its Amino Acids Preparations and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms: Phytochemical, Technological, Molecular Docking and Pharmacological Research. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyk, Y.; Koshovyi, O.; Hrytsyk, R.; Raal, A. Extracts of the Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago Canadensis L.) – Promising Agents with Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory and Hepatoprotective Activity. ScienceRise: Pharmaceutical Science 2024, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apati, P.; Szentmihályi, K.; Balázs, A.; Baumann, D.; Hamburger, M.; Kristó, T.Sz.; Szőke, É.; Kéry, Á. HPLC Analysis of the Flavonoids in Pharmaceutical Preparations from Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago Canadensis). Chromatographia 2002, 56, S65–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobjanschi, L.; Păltinean, R.; Vlase, L.; Babotă, M.; Fritea, L.; Tămaş, M. Comparative Phytochemical Research of Solidago Genus: S. Graminifolia. Note I. Flavonoids. Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fursenco, C.; Calalb, T.; Uncu, L.; Dinu, M.; Ancuceanu, R. Solidago Virgaurea L.: A Review of Its Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radušienė, J.; Karpavičienė, B.; Marksa, M.; Ivanauskas, L.; Raudonė, L. Distribution Patterns of Essential Oil Terpenes in Native and Invasive Solidago Species and Their Comparative Assessment. Plants 2022, 11, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojnicz, D.; Tichaczek-Goska, D.; Gleńsk, M.; Hendrich, A.B. Is It Worth Combining Solidago Virgaurea Extract and Antibiotics against Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli Rods? An In Vitro Model Study. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, M.; Medioni, E.; Prêcheur, I. Inhibition of Candida Albicans Yeast–Hyphal Transition and Biofilm Formation by Solidago Virgaurea Water Extracts. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2012, 61, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baležentienė, L. Secondary Metabolite Accumulation and Phytotoxicity of Invasive Species Solidago Canadensis L. during the Growth Period. Allelopathy Journal 2015, 35, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S.C.; Goodarzi, G.; Watabe, M.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Pai, S.K.; Watabe, K. Antineoplastic Activity of Solidago Virgaurea on Prostatic Tumor Cells in an SCID Mouse Model. Nutrition and Cancer 2002, 43, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C. Book of Home Remedies and Herbal Cures; Smithmark Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S.; Bone, K. The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety; Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier: Edinburgh, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- From Herbs to Healing: Pharmacognosy - Phytochemistry - Phytotherapy - Biotechnology; Szöke, É., Kéry, Á., Lemberkovics, É., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-17300-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.; Chen, T.T. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology; Art of Medicine Press: City of Industry, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.H.K. Chinese Herb Dictionary. Complementary and Alternative Healing University; 2013.

- Yang, X.; Chen, A. Encyclopedic Reference of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Manual from A–Z: Symptoms, Therapy and Herbal Remedies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sõukand, R.; Kalle, R. HERBA: Historistlik Eesti Rahvameditsiini Botaaniline Andmebaas; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, V.E.; Czyborra, P.; Fetscher, C.; Goepel, M.; Michel, M.C. Extracts from Rhois Aromatica and Solidaginis Virgaurea Inhibit Rat and Human Bladder Contraction. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2004, 369, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuschner, C.; Ellenberg, H. Competitive Effects of Introduced Solidago Species on Native Flora. In Plant Invasions: General Aspects and Special Problems; Pyšek, P., Prach, K., Rejmánek, M., Wade, M., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, D.; Joshi, S.; Bisht, G.; Pilkhwal, S. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Solidago Canadensis Linn. Root Essential Oil. J Basic Clin Pharm 2010, 1, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Shao, X.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, H. Solidago Canadensis L. Essential Oil Vapor Effectively Inhibits Botrytis Cinerea Growth and Preserves Postharvest Quality of Strawberry as a Food Model System. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anžlovar, S.; Janeš, D.; Dolenc Koce, J. The Effect of Extracts and Essential Oil from Invasive Solidago Spp. and Fallopia Japonica on Crop-Borne Fungi and Wheat Germination. Food Technol. Biotechnol. (Online) 2020, 58, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, A.H.; Alalwani, A.K.; Ahmed, M.M.; Al-Meani, S.A.L.; Al-Janaby, M.S.; Al-Qaysi, A.-M.K.; Edan, A.I.; Lahij, H.F. Impact of Solidago Virgaurea Extract on Biofilm Formation for ESBL-Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: An In Vitro Model Study. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, P.; Fitz-Binder, C.; Mahmud-Ali, A.; Bechtold, T. Production of a Concentrated Natural Dye from Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago Canadensis) Extracts. Dyes and Pigments 2012, 93, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Pavela, R.; Cianfaglione, K.; Nagy, D.U.; Canale, A.; Maggi, F. Evaluation of Two Invasive Plant Invaders in Europe (Solidago Canadensis and Solidago Gigantea) as Possible Sources of Botanical Insecticides. J Pest Sci 2019, 92, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.-R.; Wang, N.; Luo, H.; Ren, Y.; Shen, Q. Structure and Properties of Cellu-Lose/Solidago Canadensis L. Blend. Cellulose. Chemistry and Technology 2015, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Jasicka-Misiak, I.; Makowicz, E.; Stanek, N. Chromatographic Fingerprint, Antioxidant Activity, and Colour Characteristic of Polish Goldenrod (Solidago Virgaurea L.) Honey and Flower. Eur Food Res Technol 2018, 244, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas of the Estonian Flora. Elurikkus Portal.

- Nkuimi Wandjou, J.G.; Quassinti, L.; Gudžinskas, Z.; Nagy, D.U.; Cianfaglione, K.; Bramucci, M.; Maggi, F. Chemical Composition and Antiproliferative Effect of Essential Oils of Four Solidago Species ( S. Canadensis, S. Gigantea, S. Virgaurea and S.× Niederederi ). Chemistry & Biodiversity 2020, 17, e2000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Koshovyi, O. Volatile Compounds in Distillates and Hexane Extracts from the Flowers of Philadelphus Coronarius and Jasminum Officinale. ScienceRise: Pharmaceutical Science 2024, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Dolgošev, G.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Lepiku, M.; Grytsyk, A.; Koshovyi, O. The Essential Oil Composition in Commercial Samples of Verbena Officinalis L. Herb from Different Origins. Crops 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Liira, J.; Lepiku, M.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Strukov, P.; Gudzenko, A.; Koshovyi, O. The Composition of Essential Oils and the Content of Saponins in Different Parts of Gilia Capitata Sims. Crops 2025, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyk, Y.; Koshovyi, O.; Lepiku, M.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Matus, T.; Melnyk, M.; Grytsyk, L.; Raal, A. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Research in Galenic Remedies of Solidago Canadensis L. Herb. Phyton 2024, 93, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, M.; Pant, B.; Samant, M.; Shah, G.C.; Dhami, D.S. Solidago Virgaurea L.: Chemical Composition, Antibacterial, and Antileishmanial Activity of Essential Oil from Aerial Part. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants 2024, 27, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemba, D.; Thiem, B. Constituents of the Essential Oils of Four Micropropagated Solidago Species. Flavour & Fragrance J 2004, 19, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara Kołodziej Antibacterial and Antimutagenic Activity of Extracts Aboveground Parts of Three Solidago Species: Solidago Virgaurea L., Solidago Canadensis L. and Solidago Gigantea Ait. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi, H.; Kato, M. Allelopathy and Allelochemicals of Solidago Canadensis L. and S. Altissima L. for Their Naturalization. Plants 2022, 11, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranová, B.; Gruľová, D.; Szymczak, K.; Oboňa, J.; Moščáková, K. Composition and Repellency of Solidago Canadensis L. (Canadian Goldenrod) Essential Oil against Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae). AJ 2023, 58, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantan, I.B.; Yalvema, M.F.; Ahmad, N.W.; Jamal, J.A. Insecticidal Activities of the Leaf Oils of Eight Cinnamomum. Species Against Aedes Aegypti. and Aedes Albopictus. Pharmaceutical Biology 2005, 43, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Maggi, F.; Giordani, C.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; Canale, A. Insecticidal Activity of Two Essential Oils Used in Perfumery (Ylang Ylang and Frankincense). Natural Product Research 2021, 35, 4746–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevizan, L.N.F.; Nascimento, K.F.D.; Santos, J.A.; Kassuya, C.A.L.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Vieira, M.D.C.; Moreira, F.M.F.; Croda, J.; Formagio, A.S.N. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant and Anti- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Activity of Viridiflorol: The Major Constituent of Allophylus Edulis (A. St.-Hil., A. Juss. & Cambess.) Radlk. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2016, 192, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapczynski, A.; McGinty, D.; Jones, L.; Letizia, C.S.; Api, A.M. Fragrance Material Review on Cis-3-Hexenyl Salicylate. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2007, 45, S402–S405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.R.D.; Lopes, P.M.; Azevedo, M.M.B.D.; Costa, D.C.M.; Alviano, C.S.; Alviano, D.S. Biological Activities of A-Pinene and β-Pinene Enantiomers. Molecules 2012, 17, 6305–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G.; Filella, I.; Llusià, J.; Peñuelas, J. β-Ocimene, a Key Floral and Foliar Volatile Involved in Multiple Interactions between Plants and Other Organisms. Molecules 2017, 22, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonnasse, A.; Lenoir, J.-C.; Beslay, D.; Crauser, D.; Le Conte, Y. E-β-Ocimene, a Volatile Brood Pheromone Involved in Social Regulation in the Honey Bee Colony (Apis Mellifera). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.S.D.; Nunes, T.A.D.L.; Rodrigues, R.R.L.; Sousa, J.P.A.D.; Val, M.D.C.A.; Coelho, F.A.D.R.; Santos, A.L.S.D.; Maciel, N.B.; Souza, V.M.R.D.; Machado, Y.A.A.; et al. Cytotoxic and Antileishmanial Effects of the Monoterpene β-Ocimene. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Huffaker, A.; Köllner, T.G.; Weckwerth, P.; Robert, C.A.M.; Spencer, J.L.; Lipka, A.E.; Schmelz, E.A. Selinene Volatiles Are Essential Precursors for Maize Defense Promoting Fungal Pathogen Resistance. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, K.; Takikawa, H.; Ogura, Y. Syntheses of (+)-Costic Acid and Structurally Related Eudesmane Sesquiterpenoids and Their Biological Evaluations as Acaricidal Agents against Varroa Destructor. J. Pestic. Sci. 2023, 48, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Siddiqui, M.; Athar, M.; Alam, M.S. d -Limonene Modulates Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Ras-ERK Pathway to Inhibit Murine Skin Tumorigenesis. Hum Exp Toxicol 2012, 31, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lappas, C.M.; Lappas, N.T. D-Limonene Modulates T Lymphocyte Activity and Viability. Cellular Immunology 2012, 279, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.B.; Mehta, A.A. In Vitro Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity of D-Limonene. Asian J Pharm Pharmacol 2018, 4, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlberg, A.; Dooms-Goossens, A. Contact Allergy to Oxidized d -limonene among Dermatitis Patients. Contact Dermatitis 1997, 36, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, M.; Suomela, S.; Kuuliala, O.; Henriks-Eckerman, M.; Aalto-Korte, K. Occupational Contact Dermatitis Caused by D -limonene. Contact Dermatitis 2014, 71, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Species | Origin | Yield of essential oil (mL/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Solidago canadensis | Maltsa village, Viljandi municipality, Viljandi county | 14.7 ±0.5 |

| 2. | Vägeva, Jõgeva municipality, Jõgeva county | 14.9 ± 0.5 | |

| 3. | Ergeme village, Ergeme municipality, Vidzeme region, Läti | 2.7 ± 0.1 | |

| 4. | Luunja alevik, Tartu municipality, Tartu county | 2.9 ± 0.1 | |

| 5. | Pudisoo village, Kuusalu municipality, Harju county | 9.6 ± 0,3 | |

| 6. | Tallinn city | 11.5 ±0.4 | |

| 7. | Kibuna village, Saue municipality, Harju county | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| 8. | Tartu city | 8.5 ± 0.3 | |

| Average | 8.7 ± 0.3 | ||

| 9. | Solidago virgaurea | Kuusalu alevik, Kuusalu municipality, Harju county | 6.1 ± 0.2 |

| 10. | Ivaste village, Kambja municipality, Tartu county | 9.5 ± 0.3 | |

| 11. | Malla village, Viru-Nigula municipality, Lääne-Viru county | 9.0 ± 0.3 | |

| 12. | Tallinn city | 8.0 ± 0.3 | |

| 13. | Kibuna village, Saue municipality, Harju county | 11.3 ± 0.4 | |

| Average | 8.8 ± 0.3 | ||

| No | Compound | Retention index | Structure | Content. % | |||||||||||||

| Experimental | NIST23 | S. canadensis | S.virgaurea | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |||||

| 1 | Hexanal | 800 | 801 | C6H12O | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 936 | 937 | C10H16 | 25.70 | 19.42 | 13.94 | 22.28 | 21.48 | 18.23 | 24.26 | 33.35 | 17.34 | 31.68 | 25.41 | 24.02 | 19.04 |

| 3 | L-β-Pinene | 976 | 978 | C10H16 | 7.92 | 4.88 | 4.10 | 3.49 | 6.27 | 6.81 | 4.11 | 7.47 | 11.68 | 8.03 | 7.79 | 5.29 | 7.72 |

| 4 | Bornane | 976 | 980 | C10H18 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| 5 | Sulcatone | 987 | 986 | C8H14O | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| 6 | β-Myrcene | 992 | 991 | C10H16 | 2.10 | 1.14 | 13.76 | 0.26 | 2.44 | 5.29 | 9.47 | 2.38 | 11.37 | 8.35 | 4.85 | 1.13 | 8.65 |

| 7 | α-Phellandrene | 992 | 1005 | C10H16 | 2.10 | 1.14 | 13.76 | 9.03 | 2.44 | 5.29 | 9.47 | 2.38 | 11.37 | 0.90 | 4.85 | 1.13 | 8.65 |

| 8 | p-Cymene | 1024 | 1025 | C10H14 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.60 | 0.28 | 0.73 | 0.28 | 1.18 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| 9 | D-Limonene | 1029 | 1031 | C10H16 | 7.03 | 5.01 | 5.44 | 9.83 | 9.68 | 4.58 | 2.38 | 4.47 | 2.45 | 1.72 | 2.97 | 2.58 | 1.10 |

| 10 | (Z)-β-Ocimene | 1038 | 1038 | C10H16 | 6.64 | 4.53 | 5.28 | 9.03 | 9.15 | 4.17 | 2.31 | 4.09 | 3.16 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 2.23 | 0.13 |

| 11 | Salicylaldehyde | 1042 | 1047 | C7H6O2 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.22 |

| 12 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 1048 | 1049 | C10H16 | 6.64 | 4.53 | 5.28 | 9.03 | 9.14 | 4.17 | 2.31 | 4.09 | 0.76 | 1.06 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 1.18 |

| 13 | γ-Terpinene | 1058 | 1060 | C10H16 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 14 | Terpinolene | 1088 | 1088 | C10H16 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| 15 | Linalool | 1100 | 1099 | C10H18O | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.24 |

| 16 | Nonanal | 1104 | 1104 | C9H18O | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| 17 | (E)-4.8-Dimethylnona-1.3.7-triene | 1117 | 1116 | C11H18 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| 18 | α-Campholenal | 1126 | 1125 | C10H16O | 0.71 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 2.10 | 1.14 | 4.37 | 1.53 | 2.29 | 0.95 | 0.32 | 1.89 | 2.26 | 1.17 |

| 19 | (Z)-p-Mentha-2.8-dien-1-ol | 1139 | 1133 | C10H16O | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| 20 | (E)-L-Pinocarveol | 1139 | 1139 | C10H16O | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 1.18 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.65 |

| 21 | (Z)-L-Verbenol | 1141 | 1141 | C10H16O | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.26 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.16 |

| 22 | (E)-Verbenol | 1146 | 1144 | C10H16O | 0.78 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 2.51 | 1.53 | 4.86 | 1.80 | 3.34 | 1.23 | 0.50 | 1.67 | 2.43 | 1.11 |

| 23 | Pinocarvone | 1163 | 1162 | C10H14O | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.48 |

| 24 | α-Phellandrene-8-ol | 1167 | 1167 | C10H16O | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 1.02 | 0.37 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.22 |

| 25 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1177 | 1177 | C10H18O | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| 26 | L-α-Terpineol | 1191 | 1190 | C10H18O | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| 27 | (1R)-(-)-Myrtenal | 1196 | 1203 | C10H14O | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 1.49 | 1.23 | 2.60 | 1.04 | 1.82 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 1.42 | 1.96 | 1.39 |

| 28 | Decanal | 1205 | 1206 | C10H20O | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| 29 | (1S)-(-)-Verbenone | 1209 | 1204 | C10H14O | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.90 | 0.56 | 0.85 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.21 |

| 30 | (E)-Carveol | 1219 | 1217 | C10H16O | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 1.15 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.20 |

| 31 | (Z)-Carveol | 1231 | 1229 | C10H16O | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| 32 | L-Carvone | 1244 | 1245 | C10H14O | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.11 |

| 33 | Geraniol | 1255 | 1255 | C10H18O | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.10 |

| 34 | (E.E)-2.4-Decadienal | 1316 | 1317 | C10H16O | 1.08 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.21 |

| 35 | δ-EIemene | 1339 | 1338 | C15H24 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 36 | α-Cubebene | 1351 | 1351 | C15H24 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.55 | 0.29 |

| 37 | Copaene | 1378 | 1376 | C15H24 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 2.08 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.15 | 0.60 | 2.44 | 1.47 |

| 38 | Geranyl acetate | 1385 | 1382 | C12H20O2 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.09 |

| 39 | L-β-Bourbonene | 1387 | 1384 | C15H24 | 1.28 | 0.67 | 2.20 | 0.25 | 0.71 | 4.46 | 1.18 | 1.22 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| 40 | Bicyclosesquiphellandrene | 1393 | 1489 | C15H24 | 1.50 | 3.28 | 1.09 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.17 | 6.69 | 3.31 | 2.45 | 2.00 |

| 41 | β-Elemene | 1394 | 1398 | C15H24 | 2.03 | 6.96 | 5.75 | 1.09 | 3.90 | 0.87 | 6.03 | 1.14 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.42 | 17.15 | 11.55 |

| 42 | Dodecanal | 1409 | 1409 | C12H24O | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| 43 | Caryophyllene | 1423 | 1419 | C15H24 | 1.74 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 1.16 | 0.26 | 1.79 | 2.28 | 1.64 | 0.77 | 0.90 |

| 44 | β-Copaene | 1432 | 1432 | C15H24 | 1.80 | 0.63 | 0.94 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 1.21 | 1.30 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| 45 | γ-Elemene | 1436 | 1434 | C15H24 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 1.39 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| 46 | (E)-α-Bergamotene | 1438 | 1435 | C15H24 | 1.64 | 0.94 | 1.41 | 0.08 | 1.42 | 0.07 | 1.28 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| 47 | Germacrene D | 1446 | 1448 | C15H24 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| 48 | Humulene | 1461 | 1454 | C15H24 | 6.29 | 3.87 | 7.59 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 2.05 | 0.78 | 9.57 | 9.64 | 1.34 | 4.91 | 6.09 |

| 49 | (E)-β-Farnesene | 1460 | 1457 | C15H24 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 1.56 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 1.50 | 1.10 | 1.93 | 0.70 | 0.93 |

| 50 | β-Selinene | 1488 | 1486 | C15H24 | 3.89 | 9.52 | 5.70 | 6.65 | 6.29 | 1.28 | 9.65 | 0.52 | 9.67 | 6.17 | 7.18 | 0.06 | 2.48 |

| 51 | a-Muurolene | 1499 | 1502 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 0.68 | 0.31 | 1.15 | 0.09 |

| 52 | Bicylogermacrene | 1500 | 1496 | C15H24 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 1.41 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.12 | 0.16 | 0.55 | 0.38 |

| 53 | α-Farnesene | 1510 | 1508 | C15H24 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

| 54 | Cubenene | 1535 | 1532 | C15H24 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| 55 | α-Calacorene | 1546 | 1542 | C15H20 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| 56 | Elemol | 1552 | 1549 | C15H26O | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 |

| 57 | Hedycaryol | 1556 | 1553 | C15H26O | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| 58 | E-Nerolidol | 1567 | 1564 | C15H26O | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| 59 | 4.8-Epoxyazulene | 1570 | 1573 | C15H24O | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| 60 | Palustrol | 1570 | 1568 | C15H26O | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| 61 | (Z)-3-Hexenyl benzoate | 1575 | 1570 | C13H16O2 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 1.93 | 0.72 | 1.50 |

| 62 | Spathulenol | 1583 | 1576 | C15H24O | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.84 |

| 63 | Viridiflorol | 1589 | 1591 | C15H26O | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 1.30 | 3.57 | 2.40 |

| 64 | Mintketone | 1598 | 1595 | C15H24O | 0.48 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 1.39 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.46 |

| 65 | Humulene epoxide I | 1614 | 1604 | C15H24O | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.16 |

| 66 | Junenol | 1623 | 1620 | C15H26O | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 4.58 | 2.64 |

| 67 | Benzophenone | 1632 | 1635 | C13H10O | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| 68 | Isospathulenol | 1632 | 1638 | C15H24O | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.88 | 0.08 | 1.39 | 0.43 | 1.14 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.18 |

| 69 | τ-Muurolol | 1644 | 1642 | C15H26O | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| 70 | α-Cadinol | 1658 | 1653 | C15H26O | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

| 71 | (Z)-3-Hexenyl salicylate | 1671 | 1669 | C13H16O3 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| 72 | Bulnesol | 1670 | 1667 | C15H26O | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| 73 | 5-Cyclodecen-1-ol | 1690 | 1690 | C15H24O | 0.59 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 1.49 | 0.78 | 1.99 | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.40 |

| 74 | 1-Pentadecanal | 1715 | 1715 | C15H30O | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 75 | β-Nootkatol | 1721 | 1714 | C15H24O | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 76 | Benzoic acid | 1767 | 1763 | C14H12O2 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.14 | 3.06 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| 77 | 14-Hydroxy-δ-cadinene | 1805 | 1803 | C15H24O | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

| 78 | Neophytadiene | 1840 | 1837 | C20H38 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.34 |

| 79 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 1846 | 1844 | C18H36O | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| 80 | β-Phenylethyl benzoate | 1857 | 1856 | C15H14O2 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.70 |

| 81 | Benzyl salicylate | 1873 | 1871 | C14H12O3 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 1.43 | 2.09 | 11.99 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| 82 | Phytol | 2107 | 2114 | C20H40O | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Compound | Average content, % | Ratio of averages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. canadensis | S. virgaurea | ||

| D-Limonene | 6.05 | 2.17 | 2.8 |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | 5.65 | 1.21 | 4.7 |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | 5.65 | 0.69 | 8.2 |

| L-α-Terpineole | 0.07 | 0.16 | 2.3 |

| Decanal | 0.02 | 0.11 | 5.5 |

| L-Carvone | 0.61 | 0.19 | 3.2 |

| Geraniol | 0.05 | 0.29 | 5.8 |

| Cubebene | 0.03 | 0.08 | 2.7 |

| L-β-Bourbonene | 1.50 | 0.17 | 8.8 |

| 4.8-Epoxyazulene | 0.34 | 0.07 | 4.9 |

| (Z)-3-Hexenyle benzoate | 0.15 | 1.20 | 8 |

| Viridiflorol | 0.15 | 1.69 | 11.3 |

| (Z)-3-Hexanyl salicylate | 0.02 | 0.11 | 5.5 |

| 1-Pentadecanal | 0.01 | 0.07 | 7 |

| β-Nootkatol | 0.09 | 0.02 | 4,5 |

| Benzyl salicylate | 0.08 | 3.14 | 39.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).