Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Hydrodistillation of Essential Oil

2.3. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vélez-Gavilán, J. Verbena Officinalis (Vervain) 2020. CABI Compendium. 56184. [CrossRef]

- Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Dominiak, J.; Luczkiewicz, M.; Ekiert, H. Verbena Officinalis (Common Vervain) – A Review on the Investigations of This Medicinally Important Plant Species. Planta Med 2020, 86, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polumackanycz, M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Añibarro-Ortega, M.; Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Plenis, A.; Viapiana, A. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Common and Lemon Verbena. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Chou, G.; Wang, Z. Two New Iridoids from Verbena Officinalis L. Molecules 2014, 19, 10473–10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehecho, S.; Hidalgo, O.; García-Iñiguez De Cirano, M.; Navarro, I.; Astiasarán, I.; Ansorena, D.; Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. Chemical Composition, Mineral Content and Antioxidant Activity of Verbena Officinalis L. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xin, F.; Sha, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, Y.-S. Two New Secoiridoid Glycosides from Verbena Officinalis. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research 2010, 12, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia; 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Kokotkiewicz, A.; Miceli, N.; Taviano, M.F.; Maugeri, A.; Cirmi, S.; Synowiec, A.; Gniewosz, M.; Elansary, H.O.; et al. Production of Verbascoside, Isoverbascoside and Phenolic Acids in Callus, Suspension, and Bioreactor Cultures of Verbena Officinalis and Biological Properties of Biomass Extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, E.S.; El-Shazly, M.A.M.; El-Ashkar, A.M.; Aboushousha, T.; Ghareeb, M.A. Chemical Profiling of Verbena Officinalis and Assessment of Its Anti-Cryptosporidial Activity in Experimentally Infected Immunocompromised Mice. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gan, Y.; Yu, J.; Ye, X.; Yu, W. Key Ingredients in Verbena Officinalis and Determination of Their Anti-Atherosclerotic Effect Using a Computer-Aided Drug Design Approach. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1154266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibitz-Eisath, N.; Eichberger, M.; Gruber, R.; Sturm, S.; Stuppner, H. Development and Validation of a Rapid Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Diode Array Detector Method for Verbena Officinalis L. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2018, 160, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Hafsi, C.; Mohsni, I.; Ksouri, R. Évaluation de Différents Procédés d’extraction Des Composés Phénoliques d’une Plante Médicinale : Verbena Officinalis. Biologie Aujourd’hui 2021, 215, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, L.; D’Arena, G.; Minervini, M.M.; Deaglio, S.; Fusco, B.M.; Cascavilla, N.; De Feo, V. Verbena Officinalis Essential Oil and Its Component Citral as Apoptotic-Inducing Agent in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2009, 22, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohini, K.; Mohini, U.; Amrita, K.; Aishwarya, Z.; Disha, S.; Padmaja, K. Verbena Officinalis (Verbenaceae): Pharmacology, Toxicology and Role in Female Health. IJAM 2022, 13, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posatska, N.M.; Grytsyk, A.R.; Struk, O.A. RESEARCH OF STEROID AND VOLATILE COMPOUNDS IN VERBENA OFFICINALIS L. HERB. Scientific and practical journal 2024, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Qin, J.; Fu, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W. Chemical Constituents from Verbena Officinalis. Chem Nat Compd 2011, 47, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, A. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine; Second edition.; DK Publishing Inc., 2000.

- Popova, A.; Mihaylova, D.; Spasov, A. Plant-Based Remedies with Reference to Respiratory Diseases – A Review. TOBIOTJ 2021, 15, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, V.I.; Beketova, H.V. Results of a Randomised Controlled Study on the Efficacy of a Combination of Saline Irrigation and Sinupret Syrup Phytopreparation in the Treatment of Acute Viral Rhinosinusitis in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years. Clin Phytosci 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, V.N. Compendium 2020. Medicines; MORION: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.; Liu, X.; Ma, D.; Hua, X.; Jin, N. Optimization of Polysaccharides Extracted from Verbena Officinalis L and Their Inhibitory Effects on Invasion and Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Trop. J. Pharm Res 2017, 16, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encalada, M.A.; Rehecho, S.; Ansorena, D.; Astiasarán, I.; Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. Antiproliferative Effect of Phenylethanoid Glycosides from Verbena Officinalis L. on Colon Cancer Cell Lines. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2015, 63, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, R.; Adhikary, S.; Ahmad, S.; Alam, M.A. In Vitro Antimelanoma Properties of Verbena Officinalis Fractions. Molecules 2022, 27, 6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, W.-Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.-F.; Xu, S.-L.; Liu, J. Study on In-Vivo Anti-Tumor Activity of Verbena Officinalis Extract. Afr. J. Trad. Compl. Alt. Med. 2013, 10, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziurka, M.; Kubica, P.; Kwiecień, I.; Biesaga-Kościelniak, J.; Ekiert, H.; Abdelmohsen, S.A.M.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; El-Ansary, D.O.; Elansary, H.O.; Szopa, A. In Vitro Cultures of Some Medicinal Plant Species (Cistus × Incanus, Verbena Officinalis, Scutellaria Lateriflora, and Scutellaria Baicalensis) as a Rich Potential Source of Antioxidants—Evaluation by CUPRAC and QUENCHER-CUPRAC Assays. Plants 2021, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyk, A.R.; Posatska, N.M.; Klymenko, А.O. OBTAINING AND STUDY OF PROPERTIES OF EXTRACTS VERBENA OFFICINALIS. Pharmaceutical review. 2016, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, E.; García-Mina, J.M.; Calvo, M.I. Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Verbena Officinalis L. Leaves. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2008, 63, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharachorloo, M.; Amouheidari, M. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oil Isolated from Verbena Officinalis. Journal of Food Biosciences and Technology 2016, 6, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchooli, N.; Saeidi, S.; Barani, H.K.; Sanchooli, E. In Vitro Antibacterial Effects of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Verbena Officinalis Leaf Extract on Yersinia Ruckeri, Vibrio Cholera and Listeria Monocytogenes. Iran J Microbiol 2018, 10, 400–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq, A.; Khan, A.; Minhas, A.M.; Aqeel, T.; Assiri, A.M.; Bukhari, I.A. Anti-Hyperlipidemic Effects of Caralluma Edulis (Asclepiadaceae) and Verbena Officinalis (Verbenaceae) Whole Plants against High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia in Mice. Trop. J. Pharm Res 2017, 16, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Oliveira, S.M.; Dias, E.; Girol, A.P.; Silva, H.; Pereira, M.D.L. Exercise Training and Verbena Officinalis L. Affect Pre-Clinical and Histological Parameters. Plants 2022, 11, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekara, A.; Amazouz, A.; Benyamina Douma, T. Evaluating the Antidepressant Effect of Verbena Officinalis L. (Vervain) Aqueous Extract in Adult Rats. Basic Clin. Neurosci. J. 2020, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, T.; Imam, S.A.; Kamal, M. Antidepressant Activity of Methanolic Extract of Verbena Officinalis Linn. Plant in Mice. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2015, 8, 308–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian, A.; Kazemi, F.; Mehrzadi, S.; Dehpour, A.R.; Mehr, S.E.; Rezayat, S.M. Anticonvulsant Effects of Aerial Parts of Verbena Officinalis Extract in Mice: Involvement of Benzodiazepine and Opioid Receptors. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2017, 22, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyk, Y.; Koshovyi, O.; Lepiku, M.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Matus, T.; Melnyk, M.; Grytsyk, L.; Raal, A. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Research in Galenic Remedies of Solidago Canadensis L. Herb. Phyton 2024, 93, 2303–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Koshovyi, O. Volatile Compounds in Distillates and Hexane Extracts from the Flowers of Philadelphus Coronarius and Jasminum Officinale. ScienceRise: Pharmaceutical Science 2024, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalchat, J.-C.; Garry, R.-P. Chemical Composition of the Leaf Oil of Verbena Officinalis L. Journal of Essential Oil Research 1996, 8, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotkiewicz, A.; Zabiegala, B.; Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Bucinski, A.; Ekiert, H.; Luczkiewicz, M. Accumulation of Volatile Constituents in Agar and Bioreactor Shoot Cultures of Verbena Officinalis L. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2021, 144, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, L.D.; D’ Arena, G.; Minervini, M.M.; Deaglio, S.; Sinisi, N.P.; Cascavilla, N.; Feo, V.D. Active Caspase-3 Detection to Evaluate Apoptosis Induced by Verbena Officinalis Essential Oil and Citral in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Cells. Rev. bras. farmacogn. 2011, 21, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Khosla, P.K.; Puri, S. Improving Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites through Biotic and Abiotic Elicitation. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, M.; Sarac, I. Essential Oils from Plants. JBBS 2018, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Choi, D.; Park, S.; Park, T. Carvone Decreases Melanin Content by Inhibiting Melanoma Cell Proliferation via the Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP) Pathway. Molecules 2020, 25, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.T.F.D.; Ganzella, F.A.D.O.; Cardoso, G.C.; Pires, V.D.S.; Chequin, A.; Santos, G.L.; Braun-Prado, K.; Galindo, C.M.; Braz Junior, O.; Molento, M.B.; et al. L-Carvone Decreases Breast Cancer Cells Adhesion, Migration, and Invasion by Suppressing FAK Activation. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2023, 378, 110480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Costache, I.-I.; Miron, A. Anethole and Its Role in Chronic Diseases. In Drug Discovery from Mother Nature; Gupta, S.C., Prasad, S., Aggarwal, B.B., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-41341-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh, S.-A.; Abbasi-Maleki, S.; Mousavi, Z. Anti-Depressive-like Effect of Monoterpene Trans-Anethole via Monoaminergic Pathways. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2022, 29, 3255–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami-Faradonbeh, N.; Amini-Khoei, H.; Zarean, E.; Bijad, E.; Lorigooini, Z. Anethole as a Promising Antidepressant for Maternal Separation Stress in Mice by Modulating Oxidative Stress and Nitrite Imbalance. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, M.; Abbasi-Maleki, S.; Abdolghaffari, A.H. The Antidepressant Potential of (R)- (-)-Carvone Involves Antioxidant and Monoaminergic Mechanisms in Mouse Models. Phytomedicine Plus 2024, 4, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, V.Y.; Torricelli, A.S.; Giassi, A.C.C.; Coslope, L.A.; Viana, M.B. Anxiolytic Effects of Repeated Treatment with an Essential Oil from Lippia Alba and (R)-(-)-Carvone in the Elevated T-Maze. Braz J Med Biol Res 2012, 45, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagawa, M.; Satou, T.; Yukimune, C.; Ishibashi, A.; Seimiya, H.; Yamada, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Koike, K. Anxiolytic-Like Effect of Illicium Verum Fruit Oil, Trans -Anethole and Related Compounds in Mice. Phytotherapy Research 2014, 28, 1710–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M. , Varoni, E. M., Iriti, M., Martorell, M., Setzer, W. N., Del Mar Contreras, M., Salehi, B., Soltani-Nejad, A., Rajabi, S., Tajbakhsh, M., & Sharifi-Rad, J. Carvacrol and human health: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy research : PTR 2018, 32, 1675–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mączka, W. , Twardawska, M., Grabarczyk, M., & Wińska, K. Carvacrol-A Natural Phenolic Compound with Antimicrobial Properties. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aslam, M.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, I.; Afzaal, M.; Arshad, M.U.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Khames, A.; et al. Therapeutic Application of Carvacrol: A Comprehensive Review. Food Science & Nutrition 2022, 10, 3544–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansi, V.G.; Bidya, D.S. Carvacrol and its effect on cardiovascular diseases: From molecular mechanism to pharmacological modulation. Food Bioscience 2024, 57, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmani, H.; Hakimi, Z.; Arab, Z.; Marefati, N.; Mahdinezhad, M.R.; RezaeiGolestan, A.; Beheshti, F.; Soukhtanloo, M.; Mahnia, A.; Hosseini, M. Carvacrol Attenuated Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress and Depression and Anxiety like Behaviors in Lipopolysaccharide-Challenged Rats. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrouh, F.; Dakka, N.; Bakri, Y. The Antifungal Activity of Moroccan Plants and the Mechanism of Action of Secondary Metabolites from Plants. Journal de Mycologie Médicale 2017, 27, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Uddin, S.J.; Shaw, S.; Islam, M.A.; Ahmed, M.I.; Chandra Shill, M.; Karmakar, U.K.; Yarla, N.S.; Khan, I.N.; et al. Phytol: A Review of Biomedical Activities. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 121, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamdar, A.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Bernstein, A.I.; Miller, G.W.; Richardson, J.R.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal-derived semiochemical 1-octen-3-ol disrupts dopamine packaging and causes neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110, 19561–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, T.; Tao, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Ren, S.; Xu, H. Curcumin: An Epigenetic Regulator and Its Application in Cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 156, 113956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-J.; Sun, Yu.-L.; Ruan, X.-F. Bornyl acetate: A promising agent in phytomedicine for inflammation and immune modulation. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.R.; Endo, E.H.; Filho, B.P.D.; Nakamura, C.V.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; De Souza, A.; Young, M.C.M.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Cortez, D.A.G. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Properties of Piper ovatum Vahl. Molecules 2009, 14, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country of origin | Company | Webpage | Yield of EO, mL/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia 1 | Kubja Herbal Farm (2023) | https://kubja.ee/ | 1.51 |

| Estonia 2 | Kubja Herbal Farm (2024) | https://kubja.ee/ | 1.85 |

| UK | Clinic Naturae | https://clinicnaturae.com/ | 1.23 |

| Greece | You Herb It | https://www.youherbit.com/ | 4.68 |

| USA, South Carolina | Trifecta Botanicals | https://www.trifectabotanicals.com/ | 5.15 |

| Germany | Greek Herbay | https://greekherbay.com/ | 3.69 |

| Hungary | Herba Peru - Luci Vita | https://herbaperu.eu/ | 0.32 |

| Ukraine 1 | Collected from nature | Collected from nature | 1.21 |

| Ukraine 2 | PhytoBioTechnologies | https://www.goldenfarm.com.ua/en/fitobiotehnologii-ukraina/ | 0.31 |

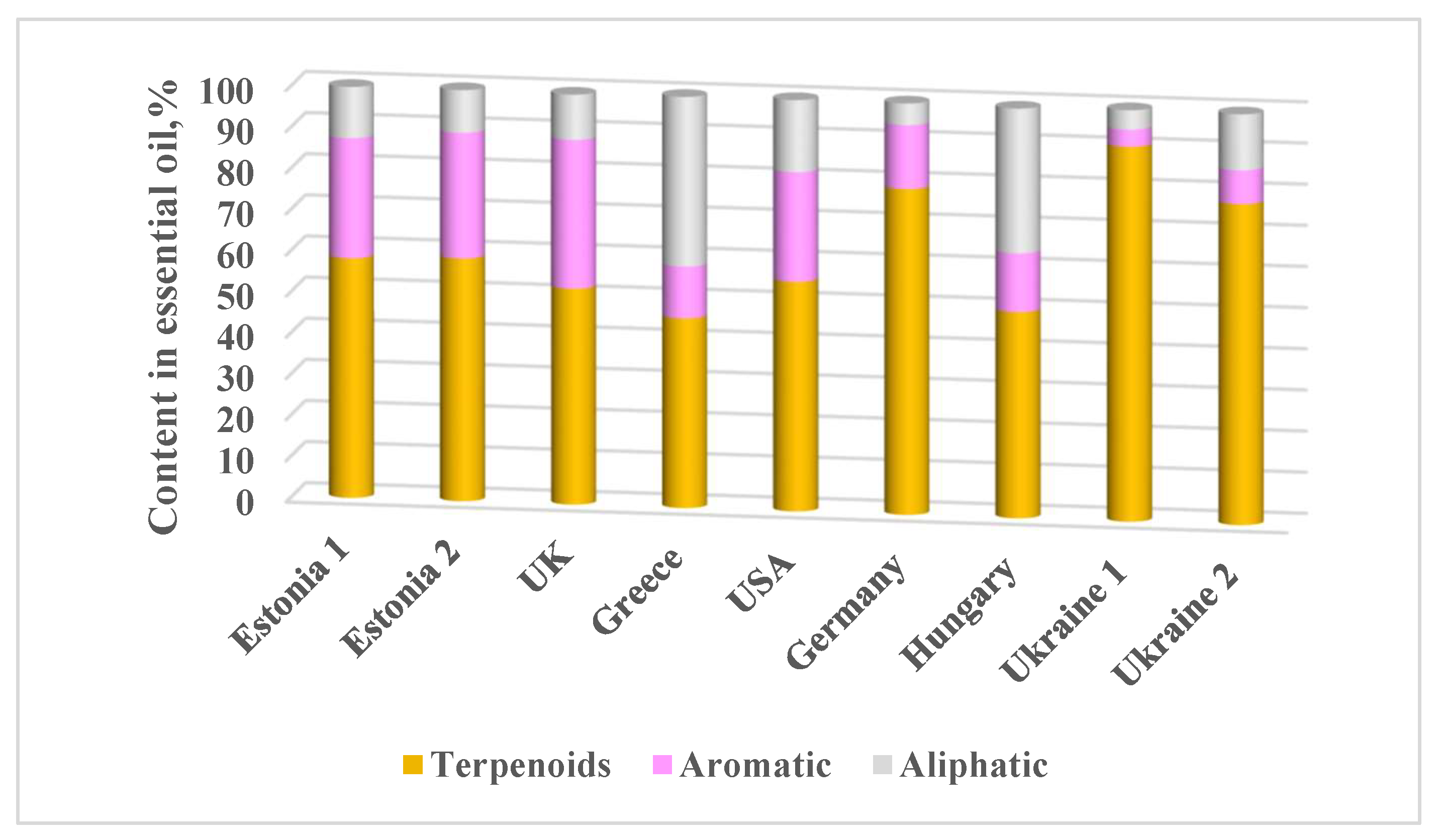

| Compound | RI | Library RI | Content in essential oil, % | Mentioned in previous studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia 1 | Estonia 2 | UK | Greece | USA | Germany | Hungary | Ukraine 1 | Ukraine 2 | ||||

| Hexanal | 800 | 801 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.09 | |

| 1-Hexanol | 865 | 868 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| p-Xylene | 866 | 865 | 1.81 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.17 | |

| α-Pinene | 932 | 932 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.71 | [13,37,39] |

| (E)-2-Heptenal | 955 | 958 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Benzaldehyde | 958 | 962 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.14 | [15] |

| α-Sabinene | 973 | 974 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | [13,39] |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 978 | 980 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.02 | 2.49 | 0.56 | 1.25 | 7.76 | 2.29 | 6.04 | [38] |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 987 | 986 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [28] |

| β-Myrcene | 991 | 991 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.95 | |

| 2-Pentyl-furan | 991 | 993 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 1.16 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.18 | |

| (Z)-2-(2-Pentenyl)furan | 1002 | 1002 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.84 | |

| (E,E)-2,4-Heptadienal | 1010 | 1012 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 2.54 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.16 | |

| o-Cymene | 1024 | 1022 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 5.75 | 3.03 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.14 | [13,39] |

| p-Cymene | 1024 | 1025 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 5.75 | 3.03 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.14 | [37] |

| D-Limonene | 1028 | 1031 | 1.66 | 1.41 | 0.32 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 5.43 | 0.42 | 1.05 | 3.22 | [28,37,38,39] |

| Eucalyptol | 1030 | 1032 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 1.62 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.05 | [28,37,38,39] |

| Benzeneacetaldehyde | 1043 | 1045 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.55 | [38] |

| (E)-2-Octenal | 1057 | 1060 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| γ-Terpinene | 1059 | 1060 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 | [13,37,39] |

| Artemisia ketone | 1058 | 1062 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 1-Octanol | 1070 | 1070 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Linalool | 1100 | 1099 | 2.28 | 1.76 | 1.04 | 2.02 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 2.09 | 0.10 | 0.23 | [28,38,39] |

| Nonanal | 1104 | 1104 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.20 | |

| α-Thujone | 1105 | 1103 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.78 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.03 | [38] |

| β-Thujone | 1105 | 1114 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [38] |

| Camphor | 1145 | 1145 | 1.76 | 1.08 | 0.23 | 1.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.91 | 0.09 | 0.02 | [38] |

| L-Menthone | 1154 | 1164 | 4.80 | 3.88 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.02 | [38] |

| DL-Menthol | 1172 | 1173 | 3.29 | 3.42 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.05 | [15,38] |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1178 | 1177 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.67 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.04 | [13,37,38,39] |

| Acetophenone | 1184 | 1183 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| α-Terpineol | 1191 | 1189 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 1.03 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.06 | [13,38,39] |

| Methyl salicylate | 1194 | 1192 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 1.15 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.06 | |

| (E)-Dihydrocarvone | 1197 | 1201 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Estragole | 1199 | 1196 | 8.17 | 6.53 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.01 | [38] |

| Decanal | 1206 | 1206 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| β-Citronellol | 1228 | 1220 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |

| Anisole | 1236 | 1235 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Pulegone | 1240 | 1237 | 2.31 | 1.51 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| L-Carvone | 1245 | 1245 | 20.36 | 16.27 | 3.77 | 3.04 | 0.36 | 2.87 | 5.82 | 0.05 | 0.15 | [38] |

| Piperitone | 1255 | 1253 | 1.31 | 0.89 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.92 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [37] |

| (E)-2-Decenal | 1262 | 1263 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| (E)-Cinnamaldehyde | 1270 | 1270 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 1.19 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| (E)-Citral | 1272 | 1270 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 3.33 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [13,37,39] |

| Anethole | 1287 | 1287 | 15.38 | 20.48 | 25.64 | 6.41 | 12.64 | 6.48 | 6.80 | 0.02 | 0.05 | [13,38,39] |

| L-Bornyl acetate | 1288 | 1285 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 7.43 | 15.86 | [39] |

| Thymol | 1292 | 1291 | 2.69 | 3.39 | 2.41 | 2.13 | 6.44 | 1.38 | 1.20 | 0.00 | 0.10 | [28,37] |

| Menthyl acetate | 1295 | 1295 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Carvacrol | 1302 | 1299 | 5.16 | 4.64 | 22.98 | 18.49 | 7.39 | 11.51 | 3.16 | 0.07 | 0.10 | [37] |

| (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal | 1317 | 1317 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 1.22 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| α-Terpinyl acetate | 1351 | 1350 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Eugenol | 1359 | 1357 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 2.52 | 1.81 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| n-Capric acid | 1369 | 1373 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Copaene | 1378 | 1376 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 1.34 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.00 | [13,37,39] |

| L-β-Bourbonene | 1387 | 1384 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 2.43 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 2.15 | |

| Methyleugenol | 1406 | 1402 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 1.45 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Caryophyllene | 1423 | 1419 | 0.26 | 0.82 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 2.62 | 0.85 | 0.46 | 1.61 | 2.74 | [28,39] |

| (Z)-β-Copaene | 1438 | 1432 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 3.01 | 4.03 | |

| (E)-Geranylacetone | 1454 | 1453 | 0.43 | 0.66 | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.12 | 0.41 | 2.34 | 0.41 | 0.76 | |

| Humulene | 1457 | 1454 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 5.59 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 2.31 | 5.00 | [39] |

| γ-Muurolene | 1479 | 1477 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 48.82 | 0.00 | [39] |

| α-Curcumene | 1485 | 1483 | 0.72 | 2.13 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 8.04 | 1.52 | 14.78 | 16.76 | [28,37] |

| (E)-β-Ionone | 1488 | 1486 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 2.16 | 2.51 | 1.48 | 7.54 | 2.35 | 1.81 | 5.41 | |

| Bicyclogermacren | 1500 | 1496 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 2.23 | [13,37,39] |

| β-Bisabolene | 1511 | 1509 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.00 | [28] |

| γ-Cadinene | 1517 | 1513 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.90 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 3.52 | [2] |

| Myristicin | 1524 | 1519 | 0.64 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| δ-Cadinene | 1526 | 1524 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.13 | [37] |

| D-Spathulenol | 1581 | 1576 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 3.32 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.35 | [37] |

| Caryophyllene oxide | 1587 | 1581 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 1.04 | 3.92 | 0.59 | 0.20 | 0.26 | [28,37] |

| Cedrol | 1605 | 1599 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| α-Humulene epoxide II | 1613 | 1606 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.20 | |

| β-Asarone | 1624 | 1626 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 2.24 | 3.21 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Benzophenone | 1629 | 1635 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 | [15] |

| Selin-11-en-4-α-ol | 1658 | 1653 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.79 | |

| ar-Turmerone | 1668 | 1664 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 1.08 | 1.34 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Asarone | 1683 | 1678 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 3.60 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Apiol | 1685 | 1682 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 1.72 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | |

| ent-Germacra-4(15),5,10(14)-trien-1β-ol | 1690 | 1690 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.61 | |

| Acorenone B | 1693 | 1701 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.40 | |

| Myristic acid | 1765 | 1768 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 2.12 | 1.05 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Phenanthrene | 1776 | 1776 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 1.48 | 2.55 | |

| Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 1846 | 1844 | 1.18 | 2.60 | 8.99 | 3.89 | 1.56 | 0.47 | 4.79 | 4.35 | 5.96 | [15] |

| Phthalic acid | 1870 | 1869 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 6.03 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.05 | |

| Farnesyl acetone | 1920 | 1918 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.27 | |

| Methyl palmitate | 1927 | 1926 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 1.95 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 1.21 | 0.37 | 0.64 | |

| Dibutyl phthalate | 1964 | 1965 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 1.37 | 1.58 | 3.45 | |

| Palmitic acid | 1977 | 1968 | 8.78 | 7.17 | 0.11 | 35.02 | 13.49 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 2.95 | [38] |

| Methyl linolenate | 2097 | 2099 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 1.79 | 0.54 | 0.93 | |

| Phytol | 2109 | 2114 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 2.01 | 7.01 | 1.60 | 4.23 | [38] |

| Hexacosane | 2594 | 2600 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.97 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 1.46 | 0.78 | 1.28 | |

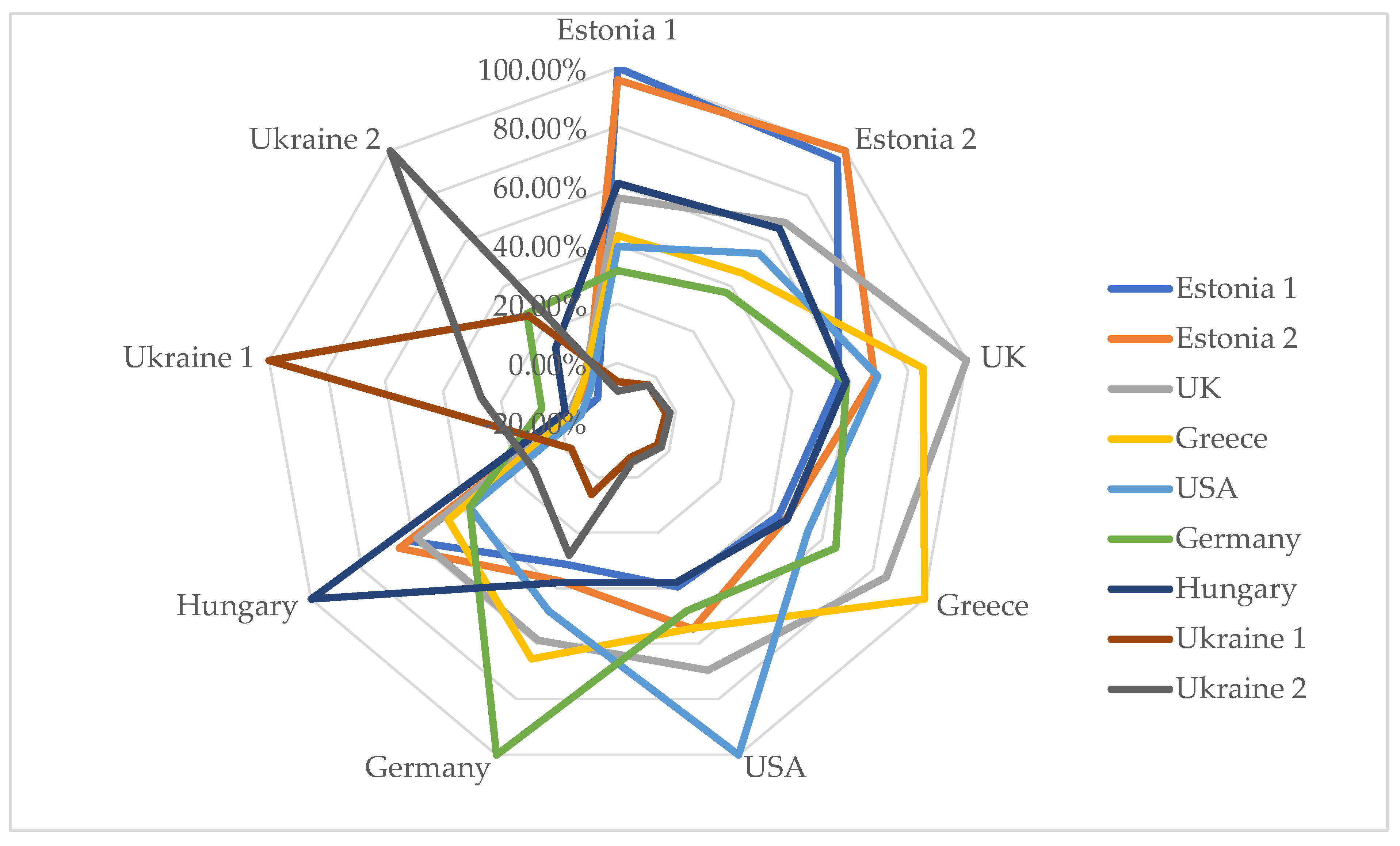

| Country | Estonia 1 | Estonia 2 | UK | Greece | USA | Germany | Hungary | Ukraine 1 | Ukraine 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pairwise similarity coefficient, % | |||||||||

| Estonia 1 | 100,00 | 95,93 | 55,95 | 43,16 | 39,46 | 31,28 | 60,87 | -6,39 | -9,52 |

| Estonia 2 | 95,93 | 100,00 | 68,24 | 45,83 | 54,56 | 37,31 | 65,47 | -3,67 | -3,87 |

| UK | 55,95 | 68,24 | 100,00 | 85,17 | 69,42 | 58,67 | 58,60 | -3,37 | -2,09 |

| Greece | 43,16 | 45,83 | 85,17 | 100,00 | 54,33 | 65,39 | 46,28 | -4,40 | -2,09 |

| USA | 39,46 | 54,56 | 69,42 | 54,33 | 100,00 | 48,22 | 37,94 | -7,31 | -5,60 |

| Germany | 31,28 | 37,31 | 58,67 | 65,39 | 48,22 | 100,00 | 37,93 | 6,07 | 27,92 |

| Hungary | 60,87 | 65,47 | 58,60 | 46,28 | 37,94 | 37,93 | 100,00 | -1,93 | 12,69 |

| Ukraine 1 | -6,39 | -3,67 | -3,37 | -4,40 | -7,31 | 6,07 | -1,93 | 100,00 | 26,98 |

| Ukraine 2 | -9,52 | -3,87 | -2,09 | -2,94 | -5,60 | 27,92 | 12,69 | 26,98 | 100,00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).