1. Introduction

Canadian goldenrod (

Solidago canadensis L.) is one of the most widespread species of the genus

Solidago from the Asteraceae family. This plant, which was first introduced in the 17th century in the Europe as an ornamental species, is now considered one of the most aggressive invasive species in Europe, China, and other regions [

1,

2]. Its ability to spread rapidly and form monodominant communities threatens biodiversity by reducing native species populations and altering ecosystem functions. The rapid expansion of

S. canadensis is driven by mechanisms such as allelopathy and high seed productivity. Additionally, biologically active compounds in its roots significantly inhibit the germination and growth of other plant species [

1,

2]. The successful invasion of

S. canadensis is further facilitated by its ability to alter soil structure and degrade soil quality by depleting nutrients [

2]. Today, it is found globally due to its rapid expansion. It thrives in various soil conditions but grows best in nutrient-rich, moderately moist, heavier soils. The plant is easy to cultivate, thus ensuring a substantial raw material base. At the same time, this plant also provides certain ecosystem benefits, such as supporting pollinators through abundant nectar production [

2,

3].

S. canadensis is also an important resource for the bioeconomy, as it is used in producing natural pesticides, dyes, pharmaceutical products, and even biofuel [

2,

4]. Given its long history of successful use in folk medicine across multiple countries, further scientific exploration is warranted, and its broader application in conventional medicine holds promise.

S. canadensis is characterized by a rich composition of biologically active compounds, such as flavonoids (rutin, quercetin, kaempferol), phenolic acids (chlorogenic, caffeic), terpenoids, saponins, and essential oil [

3,

4,

5]. According to the literature, these groups of bioactive compounds give S. canadensis it’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, diuretic, spasmolytic, antibacterial, and antitumor activities [

3,

6,

7]. The phytotherapeutic uses of S. canadensis include the treatment of chronic nephritis, cystitis, urolithiasis, and rheumatism. Additionally, it is used for anti-inflammatory applications, and as a mouth rinse for oral and throat inflammations [

8,

9,

10].

Several publications have reported on the chemical composition of

S. canadensis essential oil, identifying key compounds such as germacrene D, limonene, α-pinene, β-elemene, and bornyl acetate [

11,

12,

13]. According to the European Pharmacopoeia,

Solidago herba is standardized based on its flavonoid content, requiring a minimum of 0.5% and a maximum of 1.5%, calculated as hyperoside [

14]. The primary flavonoids in the Solidago genus include glycosides of quercetin and kaempferol and their free aglycones [

15,

16,

17]. The plant also contains polyphenolic acids, such as vanillic, gallic, caffeic, ferulic, and chlorogenic acids [

18,

19], as well as oleanane-type triterpene saponins [

3,

20]. Given its rich composition of phenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acids, S. canadensis shows potential for treating inflammatory conditions of the urinary tract, prostate adenoma, and chronic prostatitis.

In Ukraine, dry extracts of

S. canadensis are incorporated into complex herbal medicines like Marelin, Phytolysin, and Prostamed [

21]. In traditional medicine, galenic plant preparations are used to address kidney, urinary tract, and liver diseases. Externally, goldenrod is applied to purulent wounds, furunculosis, and gum abscesses through washes and compresses [

22,

23]. Given its diverse applications, further research is needed to gain knowledge of its chemical profile and pharmacological properties, and to find the most feasible pharmaceutical formulations and dosage forms for the extracts of the present plant.

Alterations to the biologically active compounds in plant extracts can help to amplify their effects. One commonly used approach is the conjugation of components in the extracts with amino acids [

24,

25,

26]. For example, the modification of acyclovir with valine resulted in the formation of a new active compound – valacyclovir – which significantly boosts the systemic plasma levels of acyclovir, thus enhancing patient comfort and clinical effectiveness [

27]. In developing L-lysine aescinate, β-escin (a triterpene saponin from chestnut) was combined with L-lysine [

21,

28]. It was demonstrated that arginine improves the bioavailability (the rate of absorption) and stability of perindopril, while also reducing its side effects [

29]. In another study, the tincture of

Leonurus cardiaca L. was combined with amino acids leading to the development of new extracts with stronger anxiolytic properties [

30]. The combination of highbush blueberry (

Vaccinium corymbosum L., Ericaceae) [

31] and cranberry leaf extracts (

Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton, Ericaceae) [

32] with arginine fostered the creation of novel active ingredients with promising hypoglycaemic and hypolipidemic effects. These examples highlight the potential of modifying

S. canadensis extracts in the development of new active compounds. Previously, it was proven that the

S. canadensis extract obtained with 40% ethanol solution had the most promising anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective activity [

33]. Therefore, this ethanolic extract was selected to be modified with amino acids in the present study.

Medicines derived from plants are known for their favourable safety profile. In combination therapy, plant-origin extracts and tinctures are often used alongside synthetic drugs to improve treatment outcomes and effectiveness. However, the galenic preparations of these plant-origin materials, such as tinctures, liquid extracts, teas and decoctions, often face challenges, such as a low patient adherence and the lack of standardization. In this context, using pharmaceutical 3D printing [

34,

35] for preparing novel oral dosage forms could offer a promising strategy to improve the efficacy and patient compliance of plant-based drug treatments. The successful formulation of 3D-printed medicinal dosage forms for plant-origin materials, such as

S. canadensis extracts, requires multidisciplinary approach and the expertise in e.g., pharmaceutical technology, polymer chemistry, engineering, and pharmacognosy.

The aim of the present study was to investigate and gain knowledge of the chemical composition, toxicity, and the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective activity of S. canadensis dry extract, its amino acids preparations and 3D-printed dosage forms. We also predicted the mechanism of anti-inflammatory action of the extracts using in silico methods, such as molecular docking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The flowering tops of

S. canadensis were collected in Tartu, Estonia (58.36277085085124, 26.747175570884128) in July 2023 and passed to Ukraine. The species was identified by Professor A.R. Grytsyk from Ivano-Frankivsk National Medical University (IFNMU), Ukraine based on the botanical catalogue [

36]. Voucher specimens No. 455–457 were deposited at the Department of Pharmaceutical Management, Drug Technology, and Pharmacognosy, Ivano-Frankivsk National Medical University. The raw plant material was dried for 14 days at room temperature in a well-ventilated space for 10 days and stored in paper bags (around 1 kg).

For preparing the dry extracts, 500.0 g of dried S. canadensis herb was macerated with 1000 ml of 40% aqueous ethanol solution in an extractor at room temperature for one day. Following this, the liquid extract was separated, and the procedure was repeated twice with the new portions of the same extractant (1000 ml each). Three liquid extracts were combined and allowed to settle for two days, and filtered. To modify the extract with amino acids, total six (6) portions of this liquid extract (400 ml each) were prepared. The following amino acids were added in triple equimolar amounts to the content of polyphenolic compounds: phenylalanine (OstroVit, Zambrov, Poland, 2.5786 g), L-arginine (FITS, Tallinn, Estonia, 2.7165 g), glycine (OstroVit, Zambrov, Poland, 1.1712 g), L-lysine (FITS, Tallinn, Estonia, 2.2809 g), β-alanine (OstroVit, Zambrov, Poland, 1.3900 g), and valine (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium, 1.8227 g). These solutions with the amino acids and the remainder of the primary liquid extract were then left to infuse for 24 hours, after which they were evaporated with a rotary vacuum evaporator Buchi B-300 (Buchi AG, Flawil, Switzerland) to form soft extracts, which were further freeze dried (lyophilized) with a SCANVAC COOLSAFE 55-4 Pro freeze drier (LaboGene ApS, Denmark). The dry extracts prepared were referred as S, S-Phe, S-Arg, S-Gly, S-Lys, S-Ala and S-Val, respectively.

2.2. Assay of Main Phytochemicals by Spectrophotometry

The quantification of hydroxycinnamic acids, flavonoids and total phenolic compounds in the dry extract of

S. canadensis and its amino acids preparations was performed with a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Hydroxycinnamic acids were determined based on their reaction with sodium molybdate and sodium nitrite and using chlorogenic acid as a reference compound at the analytical wavelength of 525 nm [

14,

19]. The content of flavonoids was determined using a reaction with aluminum chloride and rutin as a standard compound at the analytical wavelength of 417 nm [

19,

37]. Total phenolic compounds were quantified using gallic acid as a reference standard, and measuring the absorbance at 270 nm [

38,

39]. Each experiment was repeated three times to ensure statistical validity.

2.3. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds by UPLC-MS/MS

The qualitative and quantitative assessment of phenolic compounds in the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations was performed with an ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) system. Chromatographic separation was achieved using an Acquity H-Class UPLC chromatograph (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) equipped with a YMC Triart C18 column (100 × 2.0 mm, 1.9 µm). The column temperature was maintained at a constant 40 °C. The mobile phase was delivered at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, with solvent A consisting of a 0.1% aqueous formic acid solution and solvent B consisting of pure acetonitrile. Gradient elution was applied under the following conditions: solvent B was maintained at 5% from 0 to 1 min, increased to 30% from 1 to 5 min, further increased to 50% from 5 to 7 min, followed by column washing with solvent B from 7.5 to 8 min, and re-equilibration to the initial conditions (5% solvent B) from 8.1 to 10 min. A Xevo triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) was used to investigate the chemical structure of phenolic compounds. Negative electrospray ionization (ESI) mode was applied to generate ions for MS/MS analysis. The instrument parameters were as follows: capillary voltage set to -2 kV, desolvation nitrogen gas heated to 400 °C with a flow rate of 700 l/h, gas flow maintained at 20 l/h, and ion source temperature set at 150 °C. The qualitative identification of phenolic compounds was based on comparing retention times and MS/MS spectral data with analytical-grade standards. Quantification was performed using linear regression fit models and the standard dilution method [

19,

24,

40].

2.4. Assay of Amino Acids by UPLC-MS/MS

The content of amino acids in the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations was determined using an Acquity H-Class UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Xevo TQD mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). A 1 µl sample was injected onto a BEH Amide column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) maintained at 25 °C. The mobile phase consisted of an aqueous solution of 10 mmol ammonium formate with 0.125% formic acid (eluent A) and acetonitrile (eluent B). The mobile phase was delivered at the flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. Gradient elution was applied with the following parameters: 95% B from 0 to 1 min, decreased to 70% B from 1 to 3.9 min, further reduced to 30% B from 3.9 to 5.1 min, followed by column flushing with 70% of eluent A from 5.1 to 6.4 min. At 6.5 min, the gradient was returned to the initial conditions for a total run time of 10 min. The mass spectrometer operated in a positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode with the following settings: capillary voltage of +3.5 kV, cone voltage of 30 V, desolvation gas flow at 800 l/h, and desolvation temperature of 400 °C. The ion source temperature was maintained at 120 °C. Identification and peak assignment of amino acids in S. canadensis extracts were performed by comparing their retention times and MS/MS spectral data with analytical-grade standards. Quantification was achieved using linear regression fit models and the standard dilution method [

19,

41].

2.5. Molecular Docking Analysis

Autodock 4.2 software package (Autodock, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for a receptor-oriented flexible docking. Ligands were prepared using a MGL Tools 1.5.6 program (The Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA, USA). The Ligand optimization was performed using an Avogadro program (Autodock, San Diego, CA, USA). To perform calculations in the Autodock 4.2 program, the receptor and ligand data output formats were converted to a special PDBQT format. The active macromolecule centres of the test compounds with COX-1 (PDB ID: 3KK6) and COX-2 enzymes (PDB ID: 5JW1), wаs used as biological targets for docking. The test compounds were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The receptor maps were generated with MGL Tools and AutoGrid programs. The visual analysis of complexes was performed using a Discovery Studio Visualizer program (Dassault Systèmes, San Diego, CA, USA).

For docking, the physiologically active parts of flavonoids and their glycosides were selected – specifically, the flavonoid skeletons of quercetin, isoquercetin, rutin, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, and kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside. Chlorogenic, neochlorogenic, 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic, and 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acids, which are present in the extracts, may undergo hydrolysis during metabolism to form the main active metabolites – caffeic and quinic acids. Therefore, these acids were also subjected to docking [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Celecoxib was seleced as a reference drug, since its binding sites with COX-1 (PDB ID: 3KK6) and COX-2 (PDB ID: 5JW1) are well known [

46,

47]. The evaluation values obtained from our redocking process (scoring function, free energy, and binding constant) for celecoxib were used as standard reference values.

2.6. Pharmacological Research

The hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory activity and acute toxicity (LD50) of

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations were studied in accordance with the methodological guidelines of the State Expert Center of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine [

48] at the clinical-biological experimental base of IFNMU.

All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the National "General Ethical Principles of Animal Experiments" (Ukraine, 2001) aligning with the provisions of the "European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes" (Strasbourg, 1986) [

49,

50,

51]. We also take into account the ethical and moral-legal principles that ensure humane treatment of experimental animals for scientific and educational purposes (Protocol of the Ethics Committee of IFNMU No. 139/23 dated November 16, 2023).

Total 140 white outbred rats of both sexes (weighing 130-240 g) and 48 sexually mature male mice (weighing 19-25 g), were used in the present study. The animals were bred in the nursery of the clinical-biological experimental base of IFNMU. The animals were standardized based on physiological and biochemical indicators and were kept in accordance with sanitary and hygienic norms on a standard diet. Laboratory animals were housed according to the current "Sanitary Rules for the Arrangement, Equipment, and Maintenance of Experimental-Biological Clinics (Vivariums)" at a temperature of 18-20 °C and relative humidity of 50-55%. They were fed a balanced diet, following a standard regimen with free access to water.

2.6.1. Acute Toxicity of the Extracts

The acute toxicity of the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations was evaluated following the preclinical safety assessment methodology for medicinal products [

48]. Mice were divided into groups, each consisting of six animals: the control group received purified water, and the groups received the dry

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations. The animals were monitored for 14 days with the toxicity levels assessed based on changes in their general condition and mortality rates. The classification of toxicity was determined according to widely accepted standards [

19,

48].

2.6.2. Antimicrobial and Antifungal Activity of the Extracts

The antimicrobial activity of the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations extracts was studied with the clinical isolates of antibiotic-sensitive and antibiotic-resistant microorganisms. Bacterial cultures were identified using biochemical "STAPHYtest 16," "STREPTOtest 16", "ENTEROtest 24" and "NEFERMENTtest 24" micro-tests (Lachema, Czech Republic), and taking into account the set of morphological and cultural characteristics according to the recommendations of the 9th edition of Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology [

52]. Yeast-like fungal cultures were identified based on 40 biochemical tests using the VITEK 2 system with the VITEK 2 YST ID card (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France).

Screening of the antimicrobial activity of the

S. canadensis extracts was performed using the agar diffusion micro-method, developed at the Department of Microbiology, Virology, and Immunology of IFNMU [

53,

54]. This highly sensitive and discriminative method enables to make a reliable separation between active and inactive extracts. Petri dishes placed on a strictly horizontal and even surface were filled with 30 ml of agar. After the medium solidified, the wells with a diameter of 4.0 mm were made using a special punch with even edges. The agar surface was evenly inoculated with a suspension of the test culture (concentration of 1×10⁷ CFU/ml). A volume of 20 µl of plant extracts (at a concentration of 10 mg/ml) was added to the wells. After 24 hours of incubation, the diameters of the bacterial growth inhibition zones were measured. The fungistatic activity was registered after 2 days, while fungicidal activity was recorded after 4 days of incubation. Digital images of the cultures in Petri dishes were obtained and processed using the UTHSCSA ImageTool 3.0 software (The University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, ©1995-2002).

The S. canadensis extracts (including those with amino acids) at a 10 mg/ml concentration did not exhibit any antimicrobial activity. Therefore, they were re-examined at the concentrations of 100 mg/ml. The antimicrobial effects of the extracts were evaluated against such bacterial strains as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, β-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes, α-hemolytic Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumani, Pseudomonas aureginosa, Candida albicans, Candida lusitaniae, and Candida lipolytica.

2.6.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Extracts

The anti-inflammatory activity of the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations was studied on 70 sexually mature, outbred white rats of both sexes (weighing 150-240 g). Acute aseptic inflammation was induced by the sub-plantar administration of a 2% formalin solution (0.1 ml) into the hind paw of the rats. An increase in paw volume indicated the development of an inflammatory response [

33,

48].

The substances being studied were administered to the animals intra-gastrically in the form of aqueous solutions at a dose of 100 mg/kg body weight. For comparison, the anti-inflammatory activity of the following well-known synthetic and plant-origin drugs was also studied: sodium diclofenac (“Diclofenac-Darnitsa” injection solution 25 mg/ml, 3 ml in ampoules, PrJSC “Darnitsa”, Kyiv, Ukraine) and quercetin granules (“Quercetin”, PJSC Scientific-Production Center “Borshchahivskiy Chemical and Pharmaceutical Plant”, Kyiv, Ukraine) [

21]. Sodium diclofenac and quercetin were administered intra-gastrically at the doses of 8 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg body weight, respectively. The extracts and drugs were administered to the animals twice: two hours before the formalin injection and immediately after the injection.

The animals were divided into ten groups, with 7 individuals in each group. Groups 1–7 received the aqueous solutions of S. canadensis herb extracts; Group 8 received sodium diclofenac; Group 9 received quercetin; and Group 10 served as a control group.

The inflammatory response was assessed using an oncometric method [

48]. The measurements were taken before the experiment, and subsequently 1, 3 and 5 hours after the administration of the phlogogenic agent. The anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts was determined by their ability to inhibit the development of formalin-induced paw oedema in rats compared to the control group.

2.6.4. Hepatoprotective Activity of the Extracts

The hepatoprotective activity of

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations was investigated with the model of acute tetrachloromethane-induced hepatitis [

19,

48], since tetrachloromethane is capable of causing changes in the liver of animals at the morphological and biochemical levels.

To study hepatoprotective effects, the test animals (rats) were administered the extracts in a dose of 25 mg/kg body weight. The domestic Ukrainian hepatoprotector, silymarin (“Silibor” tablet the pharmaceutical company "Zdorovya," Kharkiv, Ukraine), was used as a comparison. The coating of tablets was removed, then the tablets were ground in a mortar, and administered orally as a 1% starch suspension at a dose of 25 mg/kg body weight. The animals of a control group were given purified water [

33,

48].

Liver damage in the experimental animals (except for the intact ones) was induced by the subcutaneous administration of a 50% oil solution of tetrachloromethane at a dose of 0.8 ml per 100 g body weight over two days with a 24-hour interval. The extracts and the comparison drug were administered orally 1 hour before and 2 hours after the administration of the hepatotropic agent. The intact animals and those with control pathology were also given purified water in the same manner [

48,

55].

The hepatoprotective activity of S. canadensis extracts was studied with 70 white outbred adult rats (weighing 130-240 g). The animals were divided into the following 10 groups (7 animals in each group): Group 1 – intact animals; Group 2 – control group, the animals received the 50% oil solution of tetrachloromethane; Groups 3-9 – the animals received S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations; Group 10 – the animals received a reference substance (silymarin).

The animals were euthanized by decapitation on the third day after the first administration of tetrachloromethane, and blood was collected. Then, the liver was removed from the animals and it was weighed for calculating a liver mass index (LMI) and for preparing the homogenate. The pharmacotherapeutic effectiveness of the extracts was determined based on the biochemical and functional indicators of liver and blood serum, which were measured 24 hours after the last administration of tetrachloromethane.

Biochemical studies were conducted at the Bioelementology Center of the Ivano-Frankivsk National Medical University (certificate of technical competence No. 191/24 dated July 5, 2024, valid until July 4, 2029). The intensity of peroxidative destructive processes in the animals was assessed by the TBA-active products (TBA-AP) content in the liver homogenate. The effectiveness of the hepatoprotective action of the extracts was assessed by changes in the levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in the blood serum. The present enzymes are the hepatospecific markers of cytolysis. ALT, AST, and ALP activity was determined spectrophotometrically using a standard reagent kits obtained from "Filisit-Diagnostics" (Dnipro, Ukraine). The level of lipid peroxidation products – TBA-AP – was evaluated spectrophotometrically using a reaction with 2-thiobarbituric acid (according to the method of E.N. Korobeynikova) [

56].

2.7. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing of S. canadensis Extracts

Polyethylene oxide, PEO (MW ~900,000, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used at a 12% (w/w) concentration for preparing the aqueous gels containing

S. canadensis extract for semi-solid extrusion (SSE) 3D printing. Total 1.2 g of PEO was dispersed in 10 ml of purified water and allowed to hydrate at room temperature for 13-15 hours [

34,

57]. Tween 80 (Laborat GMBH, Berlin, Germany) was incorporated to enhance the stability and homogeneity of the printing gel and to facilitate the release of

S. canadensis extract from the printed scaffolds [

58]. The printing gel formulation consisted of

S. canadensis extract in varying amounts (0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 g) and 0.5 g of Tween 80 as a surfactant. The viscosity of the printing gels was assessed at 22 ± 2 °C using a Physica MCR 101 rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria).

The 12% PEO-based gels infused with the S. canadensis extract were directly printed using a bench-top SSE 3D printing system (System 30 M, Hyrel 3D, Norcross, GA, USA). The printing process was controlled with a Repetrel software, Rev3.083_K (Hyrel 3D, Norcross, GA, USA). The parameters set for SSE 3D printings were as follows: a printing head speed of 0.5 mm/s, a blunt needle (gauge 21G), and no heating in a syringe and for a printing platform was used.

The two 3D-printed structures prepared and investigated were a 4 × 4 grid lattice (30 × 30 × 0.5 mm) and circular scaffolds with a 20 mm diameter. The present 3D-printed models were generated using Autodesk 3ds Max Design 2017 (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and FreeCAD (version 0.19, released in 2021) [

59]. The 3D-printed lattices were consisted of total six printed layers, whereas the circular scaffolds consisted of five layers.

The 3D printability was investigated by determining the weight and surface area of the printed lattices. The theoretical surface area of a 3D-printed lattice was 324 mm2, and this value was compared with the surface area of the experimental 3D-printed structures [

57,

58]. The images of the printed objects were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, version 1.51k). The weight of the 3D-printed lattices and circular scaffolds were determined with an analytical balance (Scaltec SBC 33, Scaltec, Germany).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were processed using variational statistics, calculating arithmetic means and standard deviations. The reliability of the compared values was assessed using Student’s t-test, with statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), following the methodology outlined in the State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine [

60,

61].

4. Discussion

Total 18 phenolic compounds were identified and quantified in the

S. canadensis dry extract and its amino acids preparations. The most dominant compounds were hydroxycinnamic acids, such as neochlorogenic acid and chlorogenic acid, and additionally 4.5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3.5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, and 3.4-dicaffeoylquinic acid. Rutin and isoquercitrin were the primary flavonoids. Woźniak et al. (2018) reported that

S. canadensis is also rich in flavonols (mainly quercetin and its glycosides), and has significant amounts of kaempferol derivatives [

15]. Our findings are in accordance with the results reported in the literature showing the presence of quercetin compounds, but we found a notably lower content of kaempferol derivatives. Woźniak and co-workers (2018) reported also that caffeoylquinic acid esters form a major group of phenolic compounds. In this group, 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid (neochlorogenic acid) is the predominant one accompanied by various mono- and di-caffeoylquinic acids and feruloylquinic acids [

15]. In our extracts, however, the most abundant compounds were 3.4-dicaffeylquinic, 3.5-dicaffeylquinic, 4.5-dicaffeoylquinic acids and chlorogenic acid, while ferulic acid derivatives were absent. According to the European Pharmacopoeia monograph for

Solidago herba, flavonoids (more specifically hyperoside) are considered as quality markers [

14]. Nevertheless, our study revealed a predominance of rutin and a considerable presence of hydroxycinnamic acids. Therefore, in the standardization of the dry extracts, these two categories of biologically active compounds should be taken into account. It is also important to note that the content of all phenolic compounds and their overall groups identified here was lower in the extracts modified with amino acids, which is associated with adding the amino acids. Therefore, it would be interesting to further investigate it, how this affects their pharmacological activity.

A total of 14 amino acids were identified and quantified in the dry extract of S. canadensis and its amino acids preparations (including 7 essential ones). The predominant amino acids were proline, histidine, serine, alanine, aspartic acid, lysine, and glutamic acid. To our best knowledge, no research work has been published to date providing such results on the amino acid composition of S. canadensis raw material or its extracts, thus making our findings novel and interesting.

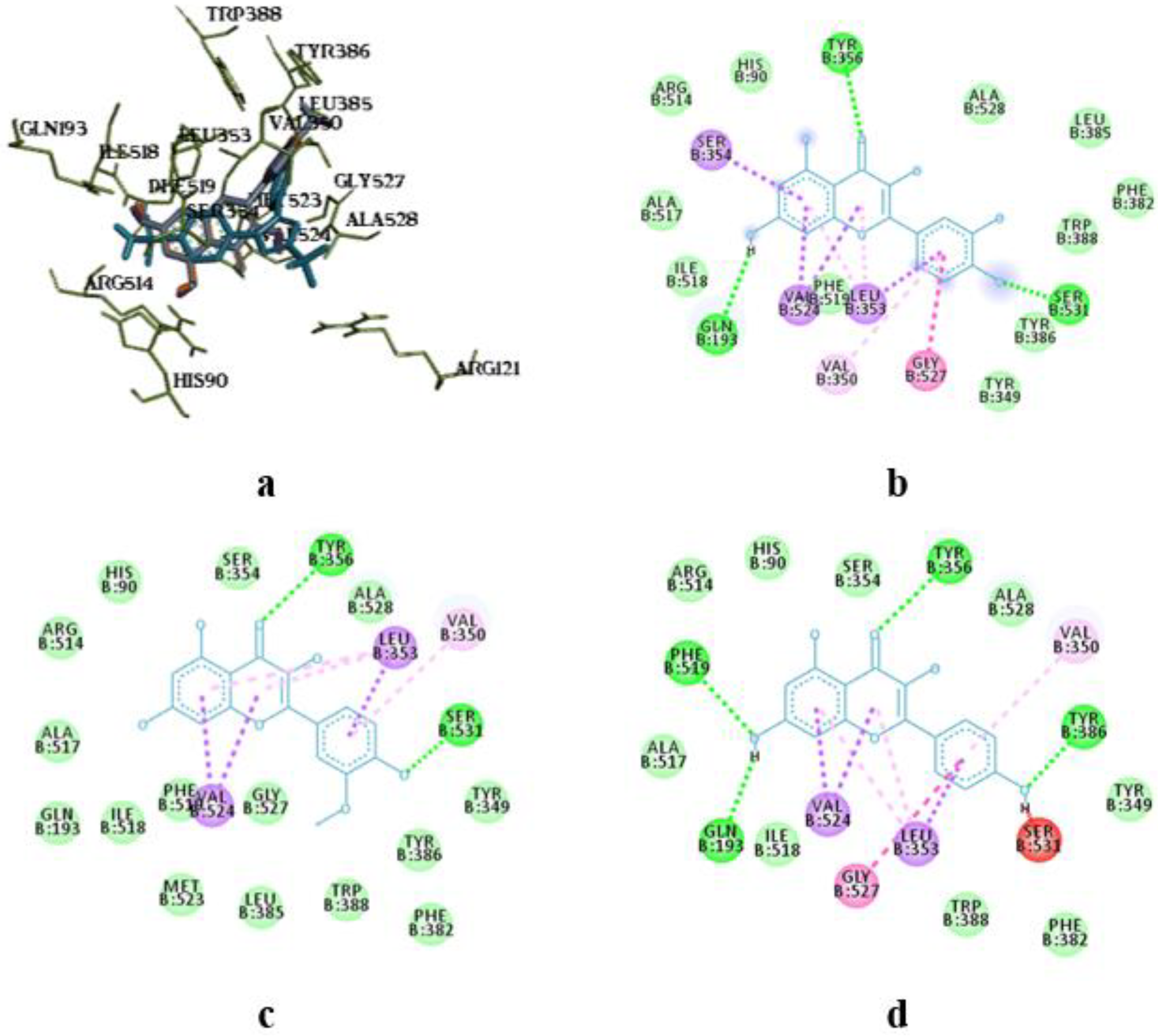

The molecular docking study showed the localization of flavonoid fraction molecules relative to COX-1 and COX-2 revealing that the binding mode of such flavonoid molecules is similar to classical inhibitors. This is evidenced by the superposition of quercetin, isorhamnetin, and kaempferol within the docking site of celecoxib (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

In the case of quercetin and isorhamnetin complexes with COX-2, hydrogen bonds involving phenolic hydroxyl groups with the Ser531 residue play a crucial role in enzyme inhibition (

Figure 4b,c). In the case of kaempferol, this interaction is negated due to forming an unfavourable bond with Ser531 (as seen in

Figure 4d).

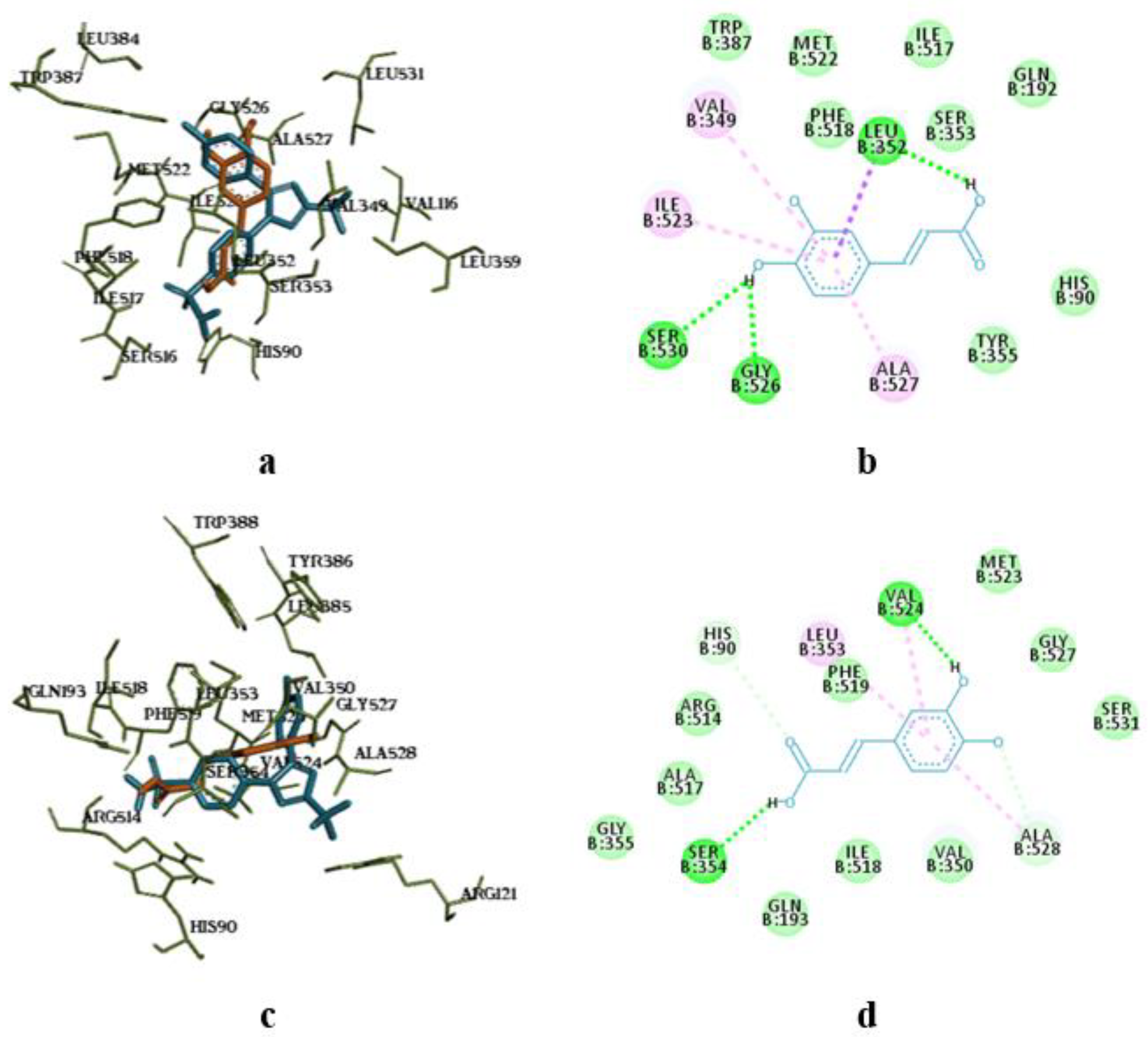

The molecular docking analysis of flavonoid complexes with the active site residues of cyclooxygenases revealed that the formation of a hydrophobic pocket (in addition to hydrogen bonds) contributes to the additional stability and strength of the complexes due to numerous hydrophobic interactions (π-σ, π-π, π-Alk). The binding of caffeic acid to the active sites of cyclooxygenases also occurs within the celecoxib-binding regions (as seen in

Figure 5a,c). As shown in

Figure 5b,d, caffeic acid forms a crucial hydrogen bond for activity expression through its phenolic hydroxyl group with the Ser530 residue and exhibits Van der Waals interactions with the Ser531 residue in the active sites of COX-1 and COX-2, respectively.

The S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations did not cause any fatalities, when administered to mice at 5000 mg/kg body weight. The general condition of the animals remained satisfactory, and only a slight physiological body weight gain (increase) was observed. No alterations in biochemical parameters or morphological structure of internal organs were found in the test animals. Therefore, the findings of the acute toxicity study of the S. canadensis herb extracts confirm the absence of toxic effects after a single intragastric administration at a dose of 5000 mg/kg. This suggests that the median lethal dose (LD₅₀) exceeds the administered dose of 5000 mg/kg, and thus the present extracts can be classified as practically non-toxic preparations (toxicity class V, LD₅₀ > 5000 mg/kg).

As seen in

Table 7, the

S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations showed antimicrobial activity against

Staphylococcus aureus,

Enterococcus faecalis and β-hemolytic

Streptococcus pyogenes. The present dry extracts and preparatons, however, did not inhibit the growth of microorganisms such as α-hemolytic

Streptococcus anginosus,

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

E.coli,

E.coli hly+,

Acinetobacter baumani,

Pseudomonas aureginosa,

Candida albicans,

Candida lusitaniae, and

Candida lipolytica. Therefore, the present preparation had only a moderate antimicrobial activity and relatively narrow microbiological spectrum.

As shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9, the inflammatory process in the rat paw in the control group was accompanied by an increase in its volume, which persisted until the end of the experiment. The administration of the extract preparations to the rats in the groups 1-7 led to varying degrees of inhibition of the inflammatory response compared to the control group. The inhibition effect started from the first hour of the study. The most pronounced anti-inflammatory effect over the entire study period was found in the groups of animals that received the S, S-Phe, S-Arg, S-Gly, and S-Ala extracts at a dose of 100 mg/kg body weight. The total anti-inflammatory activity values were 53.89%, 47.84%, 51.87%, 49.03% and 47.02%, respectively.

Within the first hour of study, all extract preparations (except S-Phe) showed higher inhibitory effect for the inflammatory reaction than that observed with quercetin. Within the first hour, the anti-inflammatory activity of two extracts (S-Arg and S-Val) was at the same level as shown with sodium diclofenac. The inflammatory activity of extract S (without any amino acids) was exceeded by 13.4%. After three hours, the most pronounced anti-inflammatory activity was observed with the S-Gly extract (5.7% higher than the corresponding activity showed with sodium diclofenac). In the animal group receiving S-Lys extract, the anti-inflammatory effect was close to that obtained with sodium diclofenac. The anti-inflammatory activity of the other extracts studied was close to the activity level of diclofenac or slightly lower. After five hours, the anti-inflammatory activity of four S. canadensis extracts (S, S-Phe, S-Arg, and S-Lys) increased, while the corresponding activity was slightly decreased with three extracts (S-Gly, S-Ala, and S-Val). After five hours, however, the anti-inflammatory activity of all extract preparations was higher than the anti-inflammatory activity of quercetin. Four S. canadensis extract preparations (S, S-Phe, S-Arg, and S-Gly) showed the anti-inflammatory activity even higher than that was found with sodium diclofenac by 21.98%, 24.60%, 16.16%, and 11.98%, respectively. In summary, the S. canadensis extracts studied here have an anti-inflammatory activity in the formalin-induced edema model. The most pronounced anti-inflammatory activity was shown with S and S-Arg S. canadensis extracts.

As shown in

Table 10, the administration of tetrachloromethane to the rodents (rats) of a control group led to a significant increase in LMI, thus indicating a liver damage. With the rats receiving

S. canadensis herb extract preparations or silymarin (a hepatoprotective drug), the changes in LMI were less pronounced compared to the intact animals of a control group. The highest hepatoprotective effect was observed with the S. canadensis extract preparation loaded with valine (S-Val), and the hepatoprotective activity was even higher than that induced with silymarin. The three extracts preparations studied (S, S-Ala and S-Lys) presented the hepatoprotective effect equal to silymarin, while S-Phe showed slightly lower effect. The two extract preparations (S-Arg and S-Gly) showed a significantly lower hepatoprotective effect compared to the intact animals (

Table 10). In summary, we showed that the

S. canadensis herb extract preparations (and silymarin) have a hepatoprotective effect by reducing liver swelling and normalizing the organ circulation in rats, and consequently, decreasing the intensity of an inflammatory process.

As seen in

Table 11, a single administration of tetrachloromethane resulted in the development of acute toxic liver damage in rats. With the rats of a control group, a significant enhancement of lipid peroxidation reactions was observed, which could lead to the depletion of an antioxidant defense system and cause the disruption of structural and functional integrity of membranes. This led to the development of a pronounced cytolytic syndrome, which was confirmed by the increase in the activity of ALT in the serum of rats by 2.99 times (p < 0.05), the increase in the activity of AST by 1.72 times (p < 0.05), and the increase in the activity of ALP by 2.64 times (p < 0.05) compared to the intact animal group (

Table 11). The development of acute toxic hepatitis was characterized by the increase in peroxide reactions and by a 2.77-fold (p < 0.05) increase in the content of TBK-AP in the liver homogenate of a control animal group compared to the intact animals.

The administration of

S. canadensis herb extracts and silymarin in a therapeutic and preventive regimen was accompanied by a reduction in pathological manifestations and by a significant decrease in the levels of biochemical indicators relative to values in the control group. As seen in

Table 11, the administration of

S. canadensis extracts S, S-Phe, S-Ala and S-Lys to rats at a dose of 25 mg/kg body weight resulted in a clear decrease in the serum enzyme activity (ALT, AST and ALP) compared to a control animal group. The most pronounced effect was found with the

S. canadensis extracts S and S-Phe, and the enzymes activity was decreased relative to the control group as follows: the ALT activity by 1.67 times (p < 0.05) and 2.09 times (p < 0.05), AST activity by 1.15 times (p < 0.05) and 1.42 times (p < 0.05), and ALP activity by 1.62 times (p < 0.05) and 1.74 times (p < 0.05), respectively. The S. canadensis extract preparations S-Ala and S-Lys presented a slightly lower effect on the development of cytolysis syndrome. These two extract preparations (S-Ala and S-Lys) reduced the ALT activity by 1.21 times (p < 0.05) and 1.37 times (p < 0.05), AST activity by 1.09 times and 1.30 times (p < 0.05), and ALP activity by 1.46 times (p < 0.05) and 1.56 times (p < 0.05), respectively.

The administration of S. canadensis extract preparations S-Arg, S-Gly and S-Val (and silymarin) to rats resulted in a slight decrease in the ALT activity by 6.7%, 7.0% and 11.8% (8.0%) (p < 0.05), AST activity by 1.0%, 2.1% and 6.8% (4.2%), and ALP activity by 11.1%, 8.0% and 19.4% (p < 0.05) (15.6%, p < 0.05) compared to the control group. The administration of the S. canadensis extract (S) to rats decreased the enzymes activity compared to the administration of silymarin: the ALT activity by 1.54 times (p < 0.05), AST activity by 1.11 times, and ALP activity by 1.13 times (p < 0.05). The inclusion of phenylalanine (S-Phe), alanine (S-Ala) and lysine (S-Lys) in S. canadensis extract also enhanced the hepatoprotective activity of the extracts. After the administration of the extract preparations S-Phe, S-Ala and S-Lys, the ALT activity in rats decreased by 1.92 times (p < 0.05), 1.11 times and 1.26 times (p < 0.05), AST activity by 1.36 times (p < 0.05), 1.04 times and 1.24 times (p < 0.05), and ALP activity by 1.49 times, 1.24 times and 1.32 times (p < 0.05) compared to the silymarin group (

Table 11).

The concomitant administration of a hepatotropic toxin and S. canadensis extracts (S, S-Phe, S-Ala, S-Lys, S-Val) at a dose of 25 mg/kg body weight resulted in a significant reduction in the TBK-AP level in the liver homogenate of rats compared to the control animal group. The TBK-AP levels found were 1.74 times (S), 2.15 times (S-Phe), 1.93 times (S-Ala), 2.14 (S-Lys), and 1.51 times (p < 0.05) lower than the TBK-AP levels observed with the control animal group. The administration of the other extract preparations S4, S5 and S9 did not change the TBK-AP level in the liver tissues of rats compared to the control group. The use of silymarin resulted in a 1.36-fold (p < 0.05) decrease in the level of TBK-reactants in the liver homogenate of rats compared to the control group.

The S. canadensis extract (S) and the extract preparations loaded with phenylalanine (S-Phe), alanine (S-Ala), and lysine (S-Lys) reduced the TBK-AP level (compared to a silymarin group) by 1.27, 1.58, 1.42, and 1.56 times, respectively (p < 0.05). The hepatoprotective activity of S-Val was equal to the activity found with silymarin, while the use of extracts S-Arg and S-Gly did not improve the levels of antioxidant system indicators compared to the use of silymarin. In summary, the results suggest that S. canadensis extracts present a clear hepatoprotective activity by inhibiting peroxide destructive processes and reducing the development of cytolysis syndrome under the acute toxic hepatitis induced by tetrachloromethane. The S. canadensis extract preparations S, S-Phe, S-Ala and S-Lys showed even a higher hepatoprotective effect compared to a hepatoprotective drug, silymarin.

The aqueous PEO printing gels loaded with 0.5-1.5 g of S. canadensis extract (in 10 ml of gel) proved feasible for SSE 3D printing. As seen in

Figure 2, the 3D-printed scaffolds (lattices and round-shaped discs) were uniform in shape and size. Moreover, the 3D-printed scaffolds (round-shaped discs) dissolved quickly in purified water at room temperature (22 ± 2 °C), thus indicating their potential as immediate-release oral delivery systems for the present plant extract.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., O.K.,V.J.,L.P. and A.R.; methodology, J.H., O.K., L.P., V.J., L.G., O.Y. and A.R.; software, O.K, Y.H., M.S., V.Z., and O.Y.; validation, O.K., Y.H. and M.S; formal analysis, O.K., Y.H., M.S., V.Z., L.G., O.Y. and A.R.; investigation, O.K., Y.H., M.S., V.Z., L.G., O.Y. and A.R.; resources, J.H. and A.R.; data curation, O.K., Y.H., M.S., V.Z., and O.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, O.K., Y.H., L.P., L.G., J.H. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, O.K., L.P., J.H., and A.R.; visualization, O.K., Y.H., and M.S.; supervision, J.H. and A.R.; project administration, J.H. and A.R.; funding acquisition, J.H. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Optical light microscopy images of the polyethylene oxide (PEO) gels with the S. canadensis extract. Magnification 50×, 100× and 200×. Red scale = 10 µm.

Figure 1.

Optical light microscopy images of the polyethylene oxide (PEO) gels with the S. canadensis extract. Magnification 50×, 100× and 200×. Red scale = 10 µm.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the semi-solid extrusion (SSE) 3D-printed scaffolds loaded with S. canadensis extract. The content of extract in the printing gel (10 g) 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 g (from left to right).

Figure 2.

Photographs of the semi-solid extrusion (SSE) 3D-printed scaffolds loaded with S. canadensis extract. The content of extract in the printing gel (10 g) 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 g (from left to right).

Figure 3.

Superposition of flavonoids compared to celecoxib (a) and intermolecular interaction diagrams of quercetin (b), isorhamnetin (c), and kaempferol (d) in the active site of COX-1. The superposed molecules are shown in the following colors: celecoxib – blue, quercetin – orange, isorhamnetin – grey, and kaempferol – purple.

Figure 3.

Superposition of flavonoids compared to celecoxib (a) and intermolecular interaction diagrams of quercetin (b), isorhamnetin (c), and kaempferol (d) in the active site of COX-1. The superposed molecules are shown in the following colors: celecoxib – blue, quercetin – orange, isorhamnetin – grey, and kaempferol – purple.

Figure 4.

Superposition of flavonoids compared to celecoxib (a) and intermolecular interaction diagrams of quercetin (b), isorhamnetin (c), and kaempferol (d) in the active site of COX-2.

Figure 4.

Superposition of flavonoids compared to celecoxib (a) and intermolecular interaction diagrams of quercetin (b), isorhamnetin (c), and kaempferol (d) in the active site of COX-2.

Figure 5.

Superposition of caffeic acid compared to celecoxib (a, c) and intermolecular interaction diagrams (b, d) in the active sites of COX-1 and COX-2, respectively. The superposition of molecules is shown in the following colors: celecoxib – blue, caffeic acid – orange.

Figure 5.

Superposition of caffeic acid compared to celecoxib (a, c) and intermolecular interaction diagrams (b, d) in the active sites of COX-1 and COX-2, respectively. The superposition of molecules is shown in the following colors: celecoxib – blue, caffeic acid – orange.

Table 1.

Content of phenolics in the S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations.

Table 1.

Content of phenolics in the S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations.

| Compound |

Content in the dry extract, mg/g |

| S [19] |

S-Phe |

S-Arg |

S-Gly |

S-β-Ala |

S-Lys |

S-Val |

| Neochlorogenic acid |

0.86 ± 0.08 |

0.78 ± 0.01 |

0.78 ± 0.02 |

0.94 ± 0.02 |

0.87 ± 0.01 |

0.85 ± 0.03 |

0.84 ± 0.02 |

| Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside |

0.21 ± 0.08 |

0.20 ± 0.01 |

0,21 ± 0.02 |

0.20 ± 0.02 |

0.20 ± 0.01 |

0.20 ± 0.03 |

0.22 ± 0.03 |

| Isoquercitrin |

8.07 ± 0.24 |

0.40 ± 0.03 |

0,42 ± 0.02 |

0.45 ± 0.01 |

0.46 ± 0.02 |

0.46 ± 0.02 |

0.43 ± 0,034 |

| Chlorogenic acid |

11.87 ± 0.42 |

14.34 ± 0.44 |

14.53 ± 0.17 |

16.54 ± 0.34 |

15.57 ± 1.42 |

15.62 ± 0.23 |

15.40 ± 0.41 |

| Quercetin |

8.43 ± 0.19 |

5.964 ± 0.29 |

6.83 ± 0.19 |

6.87 ± 0.08 |

6.50 ± 0.27 |

8.21 ± 0.22 |

6.85 ± 0.10 |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside |

2.98 ± 0.21 |

0.31 ± 0.03 |

0.32 ± 0.00 |

0.36 ± 0.01 |

0.31 ± 0.02 |

0.35 ± 0.01 |

0.36 ± 0.03 |

|

p-Coumaric acid |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0,01 |

0.04 ± 0.00 |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Ferulic acid |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

0,04 ± 0.00 |

0.05 ± 0.00 |

0.05 ± 0.00 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Vanilic acid |

0.21 ± 0.03 |

0.16 ± 0.01 |

0.16 ± 0.01 |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

0.15 ± 0.01 |

0.15 ± 0.02 |

| Caffeic acid |

0.19 ± 0.01 |

0.22 ± 0.02 |

0.24 ± 0.01 |

0.26 ± 002 |

0.22 ± 0.01 |

0.27 ± 0.01 |

0.23 ± 0.01 |

| Kaempferol |

2.67 ± 0.35 |

2.14 ± 0.08 |

2.28 ± 0.04 |

2.27 ± 0.15 |

2.13 ± 0.18 |

2.71 ± 0.30 |

2.45 ± 0.11 |

| 3,4-Dihydroxy-phenylacetic acid |

1,71 ± 0.11 |

0.58 ± 0.01 |

0.62 ± 0.01 |

0.85 ± 0.02 |

0.71 ± 0.02 |

0.64 ± 0.03 |

0.60 ± 0.02 |

| Isorhamnetin |

1.08 ± 0.18 |

0.74 ± 0.01 |

0.80 ± 0.01 |

0.80 ± 0.01 |

0.82 ± 0.03 |

0.99 ± 0.02 |

0.81 ± 0.01 |

| Rutin |

28,23 ± 0.42 |

4.76 ± 0.06 |

5.02 ± 0.22 |

5.35 ± 0.10 |

4.85 ± 0.26 |

5.55 ± 0.20 |

5.33 ± 0.15 |

| Hyperoside |

0.42 ± 0.05 |

0.12 ± 0.00 |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.02 |

0.15 ± 0.01 |

0.13 ± 0.00 |

| 4.5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

3.06 ± 0.31 |

1.82 ± 0.14 |

1.88 ± 0.12 |

2.20 ± 0.22 |

2.33 ± 0.14 |

2.29 ± 0.17 |

2.26 ± 0.07 |

| 3.5-Dicaffeylquinic acid |

4.86 ± 0.27 |

3.67 ± 0.05 |

3.99 ± 0.42 |

4.24 ± 0.29 |

3.93 ± 0.14 |

4.71 ± 0.18 |

4.74 ± 0.18 |

| 3.4-Dicaffeylquinic acid |

25.42 ± 0.53 |

21.25 ± 0.04 |

24.23 ± 2.14 |

25.44 ± 2.39 |

21.78 ± 2.38 |

28.11 ±1.15 |

28.45 ± 2.53 |

| Spectrophotometry, % |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids |

5.34 ± 0.42 |

4.93 ± 0.36 |

2.73 ± 0.26 |

4.34 ± 0.17 |

5.07 ± 0.32 |

3.22 ± 0.29 |

4.42 ± 0.21 |

| Flavonoids |

9.68 ± 0.14 |

5,18 ± 0.36 |

6.07 ± 0.47 |

6.51 ± 0.13 |

7.20 ± 0.06 |

7.55 ± 0.11 |

6.72 ± 0.15 |

| Total phenolic compounds |

11.56 ± 0.28 |

7.61 ± 0.22 |

7.19 ± 0.50 |

7.28 ± 0.09 |

7.68 ± 0.24 |

7.34 ± 0.19 |

7.88 ± 0.37 |

Table 2.

Amino acids composition of the S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations.

Table 2.

Amino acids composition of the S. canadensis extract and its amino acids preparations.

| Compound |

Content in the dry extract, mg/g |

| S [19] |

S-Phe |

S-Arg |

S-Gly |

S-β-Ala |

S-Lys |

S-Val |

| Alanine |

2.09 ± 0.07 |

1.71 ± 0.13 |

1.61 ± 0.06 |

1.95 ± 0.09 |

1.89 ± 0.32 |

1.63 ± 0.19 |

2.02 ± 0.15 |

| Arginine |

1.72 ± 0.05 |

4.45 ± 0.31 |

91.67 ± 3.78 |

8.01 ± 0.37 |

2.23 ± 0.24 |

4.23 ± 0.24 |

2.03 ± 0.12 |

| Aspartic acid |

2.26 ± 0.08 |

2.05 ± 0.20 |

2.02 ± 0.22 |

2.16 ± 0.13 |

1.59 ± 0.22 |

1.85 ± 0.07 |

2.14 ± 0.22 |

| Glutamic acid |

2.01 ± 0.11 |

1.75 ± 0.05 |

1.65 ± 0.14 |

1.78 ± 0.07 |

1.56 ± 0.10 |

1.60 ± 0.02 |

1.74 ± 0.02 |

| Glycine |

0.32 ± 0.04 |

0.32 ± 0.01 |

0.99 ± 0.08 |

92.67 ± 6.40 |

0.51 ± 0.05 |

0.28 ± 0.07 |

0.38 ± 0.07 |

| Histidine |

1.12 ± 0.03 |

0.88 ± 0.04 |

0.05 ± 0.00 |

0.76 ± 0.11 |

1.10 ± 0.01 |

1.26 ± 0.07 |

1.21 ± 0.09 |

| Isoleucine |

0.87 ± 0.04 |

1.08 ± 0.05 |

0.45 ± 0.03 |

0.60 ± 0.18 |

0.67 ± 0.08 |

0.25 ± 0.05 |

0.67 ± 0.08 |

| Leucine |

0.79 ± 0.02 |

1.24 ± 0.12 |

0.71 ± 0.02 |

0.83 ± 0.06 |

0.75 ± 0.07 |

0.67 ± 0.03 |

2.18 ± 0.14 |

| Lysine |

1.31 ± 0.05 |

0.98 ± 0.12 |

0.84 ± 0.10 |

6.78 ± 0.33 |

2.29 ± 0.13 |

231.10 ± 11.61 |

3.60 ± 0.11 |

| Phenylalanine |

1.54 ± 0.06 |

135.51 ± 10.47 |

0.65 ± 0.02 |

0.55 ± 0.01 |

0.49 ± 0.03 |

0.41 ± 0.02 |

0.56 ± 0.06 |

| Proline |

7.32 ± 0.07 |

6.60 ± 0.14 |

6.79 ± 0.27 |

7.80 ± 0.23 |

7.00 ± 0.10 |

6.88 ± 0.13 |

9.16 ± 0.09 |

| Serine |

1.76 ± 0.02 |

1.65 ± 0.10 |

1.50 ± 0.04 |

1.81 ± 0.10 |

1.46 ± 0.09 |

1.48 ± 0.05 |

1.60 ± 0.12 |

| Threonine |

0.75 ± 0.03 |

0.64 ± 0.09 |

0.54 ± 0.16 |

0.78 ± 0.43 |

0.51 ± 0.21 |

0.88 ± 0.05 |

0.63 ± 0.27 |

| Valine |

0.95 ± 0.04 |

1.60 ± 0.20 |

0.49 ± 0.05 |

0.60 ± 0.02 |

0.55 ± 0.04 |

0.99 ± 0.04 |

85.87 ± 3.81 |

| β-Alanine |

- |

- |

- |

- |

127.63 ± 4.75 |

|

|

Table 3.

The molecular docking values for the molecules in the COX-1 and COX-2 binding sites.

Table 3.

The molecular docking values for the molecules in the COX-1 and COX-2 binding sites.

| Molecules |

COX-1 |

COX-2 |

| Affinity DG1 |

EDoc2 |

Ki3 |

Affinity DG1 |

EDoc2 |

Ki3 |

| Quercetin |

-8.8 |

-4.81 |

297.39 μM |

-8.8 |

-5.63 |

75.03 μM |

| Isorhamnetin |

-8.6 |

-5.11 |

179.54 μM |

-8.9 |

-4.48 |

516.88 μM |

| Kaempferol |

-9.2 |

-5.28 |

134.94 μM |

-8.7 |

-6.07 |

35.27 μM |

| Chlorogenic acid |

-7.5 |

-1.85 |

43.74 mM |

-7.1 |

-2.09 |

29.57 mM |

| Neochlorogenic acid |

-8.6 |

-3.57 |

2.42 mM |

-7.4 |

-4.10 |

994.77 μM |

| 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

-7.7 |

+7.51 |

- |

-7.3 |

-0.99 |

188.10 mM |

| 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

-9.0 |

+2.68 |

- |

-6.4 |

-0.67 |

323.17 mM |

| 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid |

-9.0 |

+0.98 |

- |

-7.1 |

-0.96 |

198.68 mM |

| Caffeic acid |

-7.5 |

-4.78 |

314.41 μM |

-7.1 |

-3.53 |

2.60 mM |

| Quinic acid |

-6.1 |

-1.65 |

61.23 mM |

-6.1 |

-1.40 |

93.74 mM |

| Celecoxib |

-10.9 |

-8.65 |

453.15 nM |

-11.9 |

-9.87 |

58.02 nM |

Table 4.

Change in the body weight of mice after a single administration of S. canadensis extracts.

Table 4.

Change in the body weight of mice after a single administration of S. canadensis extracts.

| Group of animals |

, n = 6 |

| Before the experiment begins |

3 days |

7 days |

14 days |

| 1 (Extract S) |

21.95 ± 0.75 |

22.50 ± 0.71 |

23.15 ± 0.88* |

23.83 ± 0.85* |

| 2 (Extract S-Phe) |

23.40 ± 0.88 |

23.82 ± 0.86 |

24.43 ± 0.91 |

25.08 ± 0.82* |

| 3 (Extract S-Arg) |

20.32 ± 1.06 |

20.87 ± 1.14 |

21.28 ± 1.05 |

21.90 ± 1.13* |

| 4 (Extract S-Gly) |

23.02 ± 0.96 |

23.33 ± 1.00 |

23.88 ± 1.01 |

24.53 ± 1.06* |

| 5 (Extract S-Ala) |

20.87 ± 0.96 |

21.28 ± 0.89 |

21.82 ± 0.95 |

22.50 ± 0.80* |

| 6 (Extract S-Lys) |

23.20 ± 1.17 |

23.62 ± 1.12 |

24.22 ± 1.15 |

24.85 ± 1.13* |

| 7 (Extract S-Val) |

22.27 ± 0.61 |

22.70 ± 0.55 |

23.27 ± 0.54* |

23.88 ± 0.49* |

| Intact animals(water purified) |

18.97 ± 0.55 |

19.50 ± 0.57 |

19.88 ± 0.49* |

20.52 ± 0.39* |

Table 5.

Mass of internal organs in mice after a single administration of Solidago canadensis herb extracts.

Table 5.

Mass of internal organs in mice after a single administration of Solidago canadensis herb extracts.

| Group of animals |

, n = 6 |

| Liver |

Heart |

Kidneys |

| 1 (Extract S) |

1.31 ± 0.032 |

0.11 ± 0.009 |

0.28 ± 0.020 |

| 2 (Extract S-Phe) |

1.33 ± 0.069 |

0.12 ± 0.007 |

0.32 ± 0.017 |

| 3 (Extract S-Arg) |

1.30 ± 0.039 |

0.09 ± 0.004 |

0.29 ± 0.015 |

| 4 (Extract S-Gly) |

1.28 ± 0.054 |

0.10 ± 0.009 |

0.28 ± 0.031 |

| 5 (Extract S-Ala) |

1.26 ± 0.028 |

0.10 ± 0.005 |

0.27 ± 0.020 |

| 6 (Extract S-Lys) |

1.32 ± 0.034 |

0.10 ± 0.008 |

0.31 ± 0.025 |

| 7 (Extract S-Val) |

1.28 ± 0.031 |

0.11 ± 0.013 |

0.28 ± 0.020 |

| Intact animals(water purified) |

1.25 ± 0.020 |

0.09 ± 0.012 |

0.27 ± 0.025 |

Table 6.

Biochemical parameters of blood in mice after 14 days of a single administration of modified extracts of S. canadensis (goldenrod) herb.

Table 6.

Biochemical parameters of blood in mice after 14 days of a single administration of modified extracts of S. canadensis (goldenrod) herb.

| Group of animals |

Indicator, , n=6 |

| АLТ, µmol/h.ml |

АSТ, µmol/h.ml |

de Ritis ratio |

| 1 (Extract S) |

0.26 ± 0.031 |

0.30 ± 0.035 |

1.15 |

| 2 (Extract S-Phe) |

0.29 ± 0.029 |

0.32 ± 0.046 |

1.10 |

| 3 (Extract S-Arg) |

0.26 ± 0.034 |

0.30 ± 0.042 |

1.20 |

| 4 (Extract S-Gly) |

0.27 ± 0.033 |

0.34 ± 0.039 |

1.26 |

| 5 (Extract S-Ala) |

0.25 ± 0.043 |

0.31 ± 0.024 |

1.24 |

| 6 (Extract S-Lys) |

0.30 ± 0.054 |

0.32 ± 0.038 |

1.07 |

| 7 (Extract S-Val) |

0.28 ± 0.039 |

0.31 ± 0.040 |

1.11 |

| Intact animals(purified water) |

0.29 ± 0.023 |

0.31 ± 0.033 |

1.09 |

Table 7.

Antimicrobial activity and antifungal activity of S. canadensis extracts at a concentration of 100 mg/ml (diameters of growth inhibition zones, mm).

Table 7.

Antimicrobial activity and antifungal activity of S. canadensis extracts at a concentration of 100 mg/ml (diameters of growth inhibition zones, mm).

| Microorganisms |

ControlEthanol 40% |

S |

S-Phe |

S-Arg |

S-Gly |

S-Ala |

S-Lys |

S-Val |

| Species |

Clinical material |

Resistance |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

Pharynx |

BSSA |

growth |

13.68 ± 0.39* |

11.31 ± 0.50* |

growth |

10.34 ±1.00* |

13.77±0.32* |

10.58±0.19* |

11.78±0.74* |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

Wound |

BSSA, MLs |

growth |

13.09 ± 0.64* |

11.44 ± 0.28* |

growth |

10.51±0.28* |

13.37±0.50* |

11.38±1.46* |

11.62±0.74* |

| Enterococcus faecalis |

Urethra |

Tet, FQin |

growth |

growth |

growth |

13.79±0.49* |

12.55±1.11* |

12.09±0.56* |

0 |

11.86±0.71* |

| β-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes |

Pharynx |

S |

14.60 ± 2.28 |

growth |

growth |

18.18±0.69* |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| α-hemolytic Streptococcus anginosus |

Pharynx |

AMO, Tet,MLs |

15.51 ±1.28 |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Sputum |

S |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Sputum |

b-Lac, Tet |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| E.coli |

Wound |

S |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| E.coli |

Wound |

S |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| E.coli |

Wound |

AMO Tet, FQin |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| E.coli hly+ |

Faeces |

AMO, MLs |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Acinetobacter baumani |

Sputum |

ESbL |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Pseudomonas aureginosa |

Wound |

ESbL |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida albicans |

Oral cavity |

FCZ-R |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida albicans |

Sputum |

FCZ-R |

10.54 ± 0.62 |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida albicans |

Urine |

FCZ-R |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida albicans |

Oral cavity |

FCZ-S |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida lusitaniae |

Oral cavity |

FCZ-R |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

| Candida lipolytica |

Oral cavity |

FCZ-S |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

growth |

Table 8.

Effect of S. canadensis extracts on the development of limb edema in rats.

Table 8.

Effect of S. canadensis extracts on the development of limb edema in rats.

| Group of animals |

Dose, mg/100 g |

, n=7 |

| in 1 hour |

in 1 hours |

in 5 hours |

| 1 (Extract S) |

10 |

18.33 ± 4.21*/# |

22.89 ± 5.23* |

16.57 ± 4.46*/# |

| 2 (Extract S-Phe) |

10 |

25.51 ± 6.80 |

22.06 ± 4.12* |

15.93 ± 3.73*/# |

| 3 (Extract S-Arg) |

10 |

19.86 ± 3.07* |

22.17 ± 5.17* |

18.00 ± 2.89*/# |

| 4 (Extract S-Gly) |

10 |

24.75 ± 6.84* |

18.30 ± 4.25*/# |

19.05 ± 4.17*/# |

| 5 (Extract S-Ala) |

10 |

22.79 ± 6.21* |

21.29 ± 6.09* |

21.60 ± 5.91*/# |

| 6 (Extract S-Lys) |

10 |

21.37 ± 4.79* |

29.30 ± 5.19* |

25.78 ± 6.51* |

| 7 (Extract S-Val) |

10 |

20.40 ± 5.48* |

24.15 ± 7.10* |

27.10 ± 6.69* |

| 8 (Sodium diclofenac) |

0,8 |

20.17 ± 3.18* |

19.86 ± 3.08* |

21.97 ± 4.13* |

| 9 (Quercetin) |

0,5 |

24.22 ± 4.55 |

28.49 ± 6.06* |

32.43 ± 5.76*/** |

| 10 (Control group) |

- |

33.74 ± 6.73 |

47.33 ± 10.68 |

46.52 ± 11.45 |

Table 9.

Anti-inflammatory activity of the S. canadensis extracts in rats.

Table 9.

Anti-inflammatory activity of the S. canadensis extracts in rats.

| Group of animals |

Inflammatory response suppression index, % |

Total anti-inflammatory activity, % |

| in 1 hour |

in 1 hours |

in 5 hours |

| 1 (Extract S) |

45.67 |

51.64 |

64.37 |

53.89 |

| 2 (Extract S-Phe) |

24.37 |

53.41 |

65.75 |

47.84 |

| 3 (Extract S-Arg) |

41.15 |

53.17 |

61.30 |

51.87 |

| 4 (Extract S-Gly) |

26.65 |

61.34 |

59.09 |

49.03 |

| 5 (Extract S-Ala) |

32.46 |

55.03 |

53.56 |

47.02 |

| 6 (Extract S-Lys) |

36.65 |

38.10 |

44.58 |

39.78 |

| 7 (Extract S-Val) |

39.54 |

48.98 |

41.75 |

43.42 |

| 8 (Sodium diclofenac) |

40.26 |

58.05 |

52.77 |

50.36 |

| 9 (Quercetin) |

28.22 |

39.81 |

30.28 |

32.77 |

Table 10.

Coefficient of liver mass of experimental animals (, n = 7.

Table 10.

Coefficient of liver mass of experimental animals (, n = 7.

| Group of animals |

manimal, g |

mliver, g |

LMI, % |

| 1 (Intact animals) |

145.00 ± 11.64 |

4.59 ± 0.56 |

3.16 ± 0.26 |

| 2 (Control group, CCl4) |

153.29 ± 13.79 |

8.40 ± 1.19 |

5.45 ± 0.36* |

| 3 (Extract S) |

188.29 ± 15.49 |

6.57 ± 0.89 |

3.63 ± 0.2*/** |

| 4 (Extract S-Phe) |

203.29 ± 19.74 |

7.79 ± 0.78 |

3.83 ± 0.14*/**/# |

| 5 (Extract S-Arg) |

186.57 ± 25.98 |

7.78 ± 1.80 |

4.15 ± 0.48*/**/# |

| 6 (Extract S-Gly) |

181.57 ± 15.49 |

8.09 ± 1.38 |

4.51 ± 0.98*/**/# |

| 7 (Extract S-Ala) |

220.00 ± 16.02 |

8.02 ± 0.60 |

3.60 ± 0.11*/** |

| 8 (Extract S-Lys) |

213.9 ± 23.68 |

7.64 ± 0.85 |

3.61 ± 0.44** |

| 9 (Extract S-Val) |

216.57 ± 11.54 |

7.26 ± 1.03 |

3.34 ± 0.37** |

| 10 (Silymarin) |

220.00 ± 11.94 |

7.93 ± 0.82 |

3.60 ± 0.22*/** |

Table 11.

The effect of S. canadensis extracts on the course of acute toxic hepatitis in rats caused by the administration of carbon tetrachloride (M ± m).

Table 11.

The effect of S. canadensis extracts on the course of acute toxic hepatitis in rats caused by the administration of carbon tetrachloride (M ± m).

| Group of animals |

Biochemical indicators |

| Blood serum |

Liver homogenate |

| ALT, μmol/h x mL |

AST, μmol/h x mL |

ALP, nmol/s x L |

TBK-AP nmol/g |

| 1 (Intact animals) |

1.55 ± 0.13 |

2.23 ± 0.28 |

1859.14 ± 177.67 |

18.63 ± 2.68 |

| 2 (Control group, CCl4) |

4.64 ± 0.31* |

3.83 ± 0.24* |

4913.29 ± 465.37* |

51.60 ± 8.58* |

| 3 (Extract S) |

2.78 ± 0.39*/**/# |

3.32 ± 0.47*/** |

3025.29 ± 442.29*/**/# |

29.72 ± 3.40*/**/# |

| 4 (Extract S-Phe) |

2.22 ± 0.36*/**/# |

2.69 ± 0.44*/**/# |

2783.86 ± 332.95*/**/# |

23.98 ± 5.69**/# |

| 5 (Extract S-Arg) |

4.33 ± 0.50* |

3.82 ± 0.25* |

4366.86 ± 483.42* |

47.40 ± 10.35* |

| 6 (Extract S-Gly) |

4.30 ± 0.42* |

3.75 ± 0.61* |

4520.00 ± 741.14* |

48.81 ± 5.86*/# |

| 7 (Extract S-Ala) |

3.84 ± 0.54*/** |

3.52 ± 0.51* |

3354.86 ± 407.24*/**/# |

26.71 ± 7.69*/**/# |

| 8 (Extract S-Lys) |

3.39 ± 0.56*/**/# |

2.95 ± 0.46*/**/# |

3148.29 ± 451.68*/**/# |

24.10 ± 4.44*/**/# |

| 9 (Extract S-Val) |

4.09 ± 0.40*/** |

3.57 ± 0.37* |

3962.00 ± 435.33*/** |

34.22 ± 6.20*/** |

| 10 (Silymarin) |

4.27 ± 0.39* |

3.67 ± 0.37* |

4146.71 ± 610.78*/** |

37.82 ± 3.71*/** |

Table 12.

Physical properties of the polyethylene oxide (PEO) printing gels loaded with S. canadensis extract and the corresponding 3D-printed scaffolds.

Table 12.

Physical properties of the polyethylene oxide (PEO) printing gels loaded with S. canadensis extract and the corresponding 3D-printed scaffolds.

| The amount of extract (g) in the printing gel (10 g) |

Viscosity, cP(22 ± 2 °C) |

Surface area of the 3D-printed lattices, mm2 |

Spractical / Stheoretical |

Mass of lattices, mg |

Mass of round-shaped discs, mg |

| 0.5 |

126867 ± 4958 |

347.72 ± 19.56 |

1.07 |

176.4 ± 2.1 |

125.7 ± 1.1 |

| 1.0 |

125233 ± 5132 |

354.36 ± 27.97 |

1.09 |

206.7 ± 2.7 |

148.0 ± 4.6 |

| 1.5 |

102967 ± 1775 |

373.13 ± 29.34 |

1.15 |

220.3 ± 2.5 |

154.4 ± 0.6 |