Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

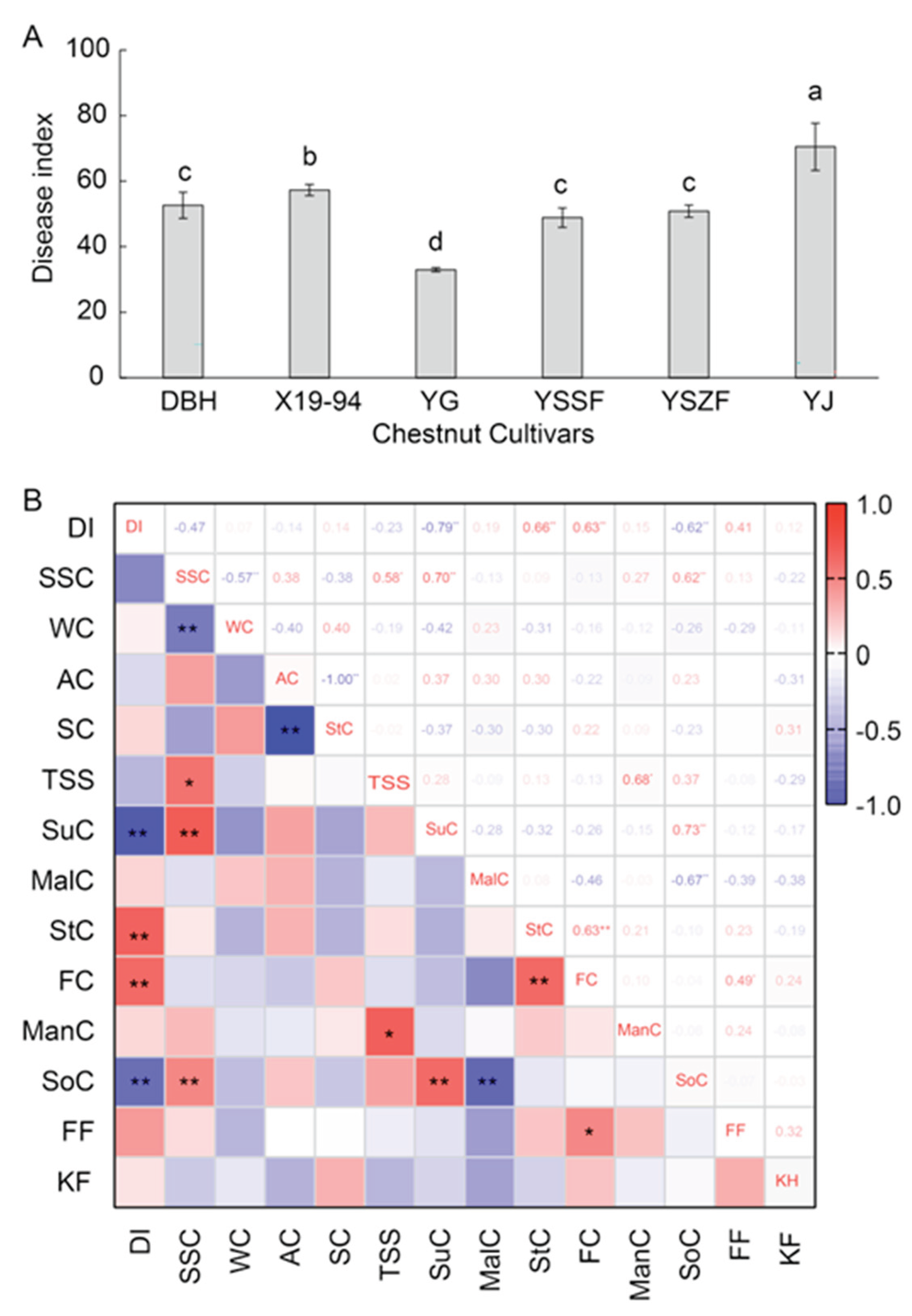

This study aimed to identify fungal species causing fruit rot of chestnut (Castanea mollissima) in Hebei Province, China and analyze the resistance differences among major cultivars. A total of 220 fungal isolates were obtained from healthy and diseased kernels, which were classified into six distinct genera. Based on both morphological and molecular analyses, these isolates were identified as Diaporthe eres (48.6% isolation frequency), Talaromyces rugulosus (22.3%), Alternaria alternata (10.5%), Mucor circinelloides (9.5%), Fusarium proliferatum (5.5%), and Rhizopus stolonifer var. stolonifer (3.6%). Among these, D. eres was firstly reported to cause fruit rot on C. mollissima in China. Moreover, disease resistance evaluation of major cultivars showed significant differences: YG, YSSF, and DBH exhibited strong resistance under both natural conditions (with 1.7% to 5.3% DI after 180 days storage) and artificial inoculation (with 33.0±0.6 to 52.6±4.0 DI); while YJ was highly susceptible (with 47.7% decay incidence and 70.5±7.2 DI). Correlation analysis revealed that the disease index was negatively correlated with sucrose and sorbitol contents, but positively correlated with stachyose and fructose contents. This study advances the understanding of postharvest chestnut fruit rot, and provide a theoretical basis for breeding resistant cultivars and developing control strategies to mitigate losses and ensure food safety.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Disease Surveys and Isolation of Fungi

2.2. Morphological Identification and Characterization

2.3. DNA Extraction and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. Pathogenicity Study

2.5. Assessing of Disease Severity on Chestnut Cultivars

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Disease Symptom and Development During Postharvest Storage

3.2. Fungal Isolation and Identification

3.3. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

3.4. Morphology and Taxonomy

3.5. Pathogenicity Study

3.6. Disease Severity of Virous Chestnut Cultivars

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodell, E. Castanea mollissima: a Chinese chestnut for the Northeast. Arnoldia 1983, 43, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, A.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Qin, L. Physiological response of chestnuts (Castanea mollissima Blume) infected by pathogenic fungi and their correlation with fruit decay. Food Chemistry 2024, 22, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettraino, A.M.; Bianchini, L.; Caradonna, V.; Forniti, R.; Goffi, V.; Zambelli, M.; Testa, A.; Vinciguerra, V.; Botondi, R. Ozone gas as a storage treatment to control Gnomoniopsis castanea, preserving chestnut quality. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 6060–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianelli, G.; Morales-Rodriguez, C.; Thomidis, T.; Vannini, A. Fungal community and toxigenic taxa in chestnut fruits in postharvest conditioning process and storage. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2024, 104, 8953–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.N.; Li, S.M.; Wen, X.L.; Feng, L.N.; Wang, J.F.; Yang, W.J.; Huo, J.H.; Lan, S.H.; Sun, W.M.; Qi, H.X. Identification and biological characteristics of the pathogen causing pink disease of chestnut. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2021, 23, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Laue, B.; Steele, H.; Green, S. Survival, cold tolerance and seasonality of infection of European horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) by Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi. Plant Pathology 2014, 63, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Tian, C. An emerging pathogen from rotted chestnut in China: Gnomoniopsis daii sp. nov. Forests 2019, 10, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, S.; Peng, L.; Zeng, K.; Feng, B.; Jingjing, Y. Compositional shifts in fungal community of chestnuts during storage and their correlation with fruit quality. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2022, 191, 111983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Venâncio, A.; Lima, N. Mycobiota and mycotoxins of almonds and chestnuts with special reference to aflatoxins. Food Research International 2012, 48, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttleworth, L.A.; Guest, D.I. The infection process of chestnut rot, an important disease caused by Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) in Oceania and Europe. Australasian Plant Pathology 2017, 46, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kayal, W.; Chamas, Z.; El-Sharkawy, I.; Subramanian, J. Comparative anatomical responses of tolerant and susceptible European plum varieties to black knot disease. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 3244–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Fang, H.; Jia, Y.; Yun, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Comparative evaluation of physical and chemical properties, nutritional components and volatile substances of 24 chestnut varieties in Yanshan area. Food Chemistry 2025, 477, 143624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Fan, L.; Wang, G. Analysis of nut phenotypic traits and comprehensive evaluation of kernel yield traits of chestnut varieties (strains) in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Forest Research 2025, 38, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Ji, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J. Molecular identification and pathogenicity of Diaporthe eres and D. hongkongensis (Diaporthales, Ascomycota) associated with cherry trunk diseases in China. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, R.; Fu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Hao, N. Characterization of Sclerotinia nivalis causing Sclerotinia rot of Pulsatilla koreana in China. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2015, 143, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, M.; Ze, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Hu, L.; Zhao, N. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium species from herbaceous plants on grassland in Qiaojia County, China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Applied and environmental microbiology 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedvlieg, W.; Kema, G.; Groenewald, J.; Verkley, G.; Seifbarghi, S.; Razavi, M.; Gohari, A.M.; Mehrabi, R.; Crous, P.W. Zymoseptoria gen. nov.: a new genus to accommodate Septoria-like species occurring on graminicolous hosts. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 2011, 26, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, S.; Jo, M.; An, S.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, J.; Jeong, M.-H.; Kim, E.Y.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y. Isolation and identification of Alternaria alternata from potato plants affected by leaf spot disease in Korea: selection of effective fungicides. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular biology and evolution 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.; Biosciences, I.; Carlsbad, C. BioEdit: an important software for molecular biology. GERF Bulletin of Biosciences 2011, 2, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Valent, B.; Lee, F. Determination of host responses to Magnaporthe grisea on detached rice leaves using a spot inoculation method. Plant Disease 2003, 87, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, L.; Shuhang, Z.; Yan, G.; Xinfang, Z.; Guangpeng, W. Diversity analysis of soluble sugar related traits in Chinese chestnut. Journal of Plant Genetic Resources 2023, 24, 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, N.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Talaromyces. Studies in mycology 2014, 78, 175–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pan, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, M.; Zhong, C. First report of Alternaria alternata causing postharvest rot of kiwifruit in China. Plant Disease 2017, 101, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Stielow, J.B.; de Hoog, G.S.; Bensch, K.; Schwartze, V.U.; Voigt, K.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Kurzai, O.; Walther, G. A new species concept for the clinically relevant Mucor circinelloides complex. Persoonia 2019, 44, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moral, A.; Antón-Domínguez, B.I.; Lovera, M.; Arquero, O.; Trapero, A.; Agustí-Brisach, C. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium species associated with wilting and crown rot in almond (Prunus dulcis). Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.Y.; Chen, S.R.; Wei, Y.H.; Lee, F.L.; Fu, H.M.; Yuan, G.F.; Stalpers, J.A. Polyphasic approach to the taxonomy of the Rhizopus stolonifer group. Mycological Research 2007, 111, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lücking, R.; Aime, M.C.; Robbertse, B.; Miller, A.N.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Aoki, T.; Cardinali, G.; Crous, P.W.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Geiser, D.M.; et al. Unambiguous identification of fungi: where do we stand and how accurate and precise is fungal DNA barcoding? IMA Fungus 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; Consortium, F.B.; List, F.B.C.A.; Bolchacova, E.; et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the national academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, H.B.; Jeewon, R.; Hongsanan, S.; Bhat, D.; Tang, S.M.; Lumyong, S.; Mortimer, P.; Xu, J.C.; Erio, C.; et al. Alternaria: update on species limits, evolution, multi-locus phylogeny, and classification. Studies in Fungi 2023, 8, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.Q.; Wang, Y.; Orr, M.C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.B. Identification of species by combining molecular and morphological data using convolutional neural networks. Systematic biology 2022, 71, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Lin, L.; Pan, M.; Fan, X. Studies of Diaporthe (Diaporthaceae, Diaporthales) species associated with plant cankers in Beijing, China, with three new species described. MycoKeys 2023, 98, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Xie, Y.; Huo, G.; Cui, C. Postharvest fruit rot of pear caused by Diaporthe eres in China. Journal of Plant Pathology 2023, 105, 1153–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Wang, J. First report of black rot on persimmon fruits caused by Diaporthe eres in China. Plant Disease 2023, 107, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, O.O.; Singleton, I.; Sant'Ana, A.S. Sources and contamination routes of microbial pathogens to fresh produce during field cultivation: A review. Food Microbiology 2018, 73, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, D.; Jørgensen, H.J.L.; Latz, M.; Manzotti, A.; Ntana, F.; Rojas, E.; Jensen, B. Searching for novel fungal biological control agents for plant disease control among endophytes. Endophytes for a growing world 2019, 31, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Danso Ofori, A.; Zheng, T.; Titriku, J.K.; Appiah, C.; Xiang, X.; Kandhro, A.G.; Ahmed, M.I.; Zheng, A. The role of genetic resistance in rice disease management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Cui, D.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Sui, X.; Fan, Q. Identification and assessment of resistance to Fusarium head blight and mycotoxin accumulation among 99 wheat varieties. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.; Jordá, L.; Torres, M.Á.; Martín-Dacal, M.; Berlanga, D.J.; Fernández-Calvo, P.; Gómez-Rubio, E.; Martín-Santamaría, S. Plant cell wall-mediated disease resistance: Current understanding and future perspectives. Molecular Plant 2024, 17, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schie, C.C.; Takken, F.L. Susceptibility genes 101: how to be a good host. Annual review of phytopathology 2014, 52, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiade, S.R.G.; Zand-Silakhoor, A.; Fathi, A.; Rahimi, R.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.D.; Zulfiqar, U.; Chaudhary, T. Plant metabolites and signaling pathways in response to biotic and abiotic stresses: Exploring bio stimulant applications. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajný, J.; Trávníčková, T.; Špundová, M.; Roenspies, M.; Rony, R.M.I.K.; Sacharowski, S.; Krzyszton, M.; Zalabák, D.; Hardtke, C.S.; Pečinka, A.; et al. Sucrose-responsive osmoregulation of plant cell size by a long non-coding RNA. Molecular Plant 2024, 17, 1719–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; James, D.; Das, S.; Patel, M.K.; Sutar, R.R.; Achary, V.M.M.; Goel, N.; Gupta, K.J.; Reddy, M.K.; Jha, G.; et al. Co-overexpression of SWEET sucrose transporters modulates sucrose synthesis and defence responses to enhance immunity against bacterial blight in rice. Plant, Cell & Environment 2024, 47, 2576–2594. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, D.; Li, C.; Park, H.-J.; González, J.; Wang, J.; Dandekar, A.M.; Turgeon, B.G.; Cheng, L. Sorbitol modulates resistance to Alternaria alternata by regulating the expression of an NLR resistance gene in apple. The Plant Cell 2018, 30, 1562–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Q.; Liu, J.; Lin, X.; Hu, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Huai, B.; Huang, L.; Voegele, R.T.; et al. A unique invertase is important for sugar absorption of an obligate biotrophic pathogen during infection. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 1548–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asad, M.A.U.; Yan, Z.; Zhou, L.; Guan, X.; Cheng, F. How abiotic stresses trigger sugar signaling to modulate leaf senescence? Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 210, 108650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).