Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Colocasia esculenta, also known as Chinese taro or taro, is a crop of great importance for the Colombian Pacific region. However, it is threatened by corm rot, which affects the food security of Afro-descendant and indigenous communities in the area. This study aimed to identify some of the phytopathogenic agents responsible for this disease and explore their control using an aqueous extract of Dysphania ambrosioides (paico). Through morphological analyses and ITS gene sequencing, two fungi responsible for the rot were identified: Fusarium solani and Mycoleptodiscus suttonii, and their roles as causal agents of the rot were confirmed in greenhouse experiments. Paico proved effective in controlling the growth of these fungi, with concentrations of 12.5% and 17.5% for M. suttonii, and 17.5% for F. solani. These findings highlight the importance of organic control to ensure food security and sustainable production in vulnerable areas of Colombia, emphasizing the relevance of this study for local communities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Collection of Chinese Yam Samples with Corm rot and Phytopathogenic Agents Identification

Preparation of the Aqueous Extract from Dysphania ambrosioides (Paico)

Experimental Design

3. Results

Sample Collection During Harvest Season and Isolation of Fungal Pathogens

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Elteen, K. H.; Hamad, M. Fungi. Biology and applications. Fungi. Wiley. 2017. 299–332. [CrossRef]

- Asprilla-Perea, J.; Diaz-Puente, J. M. Traditional use of wild edible food in rural territories within tropical forest zones: A case study from the northwestern Colombia. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences 2018, 5, 162–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkezari, J.S.; Namiranian, N.; Gholami, S.; Elahi, M.; Rahmanian, M. Proximal, Microbiological and Nutritional Characterization in Chinese Potato Flour of the White Variety Colocasia esculenta for Application in Functional Foods. Int J Reprod Biomed 2019, 17, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, P.; Saikia, K.; Ahmed, S. S. Pathogenic fungi associated with storage rot of Colocasia esculenta and evaluation of bioformulations against the pathogen. Pest Management in Horticultural Ecosystems 2020, 26, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditika, B.; Kapoor, S.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P. Taro (Colocasia esculenta): Zero wastage orphan food crop for food and nutritional security. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 145, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colariccio, A.; De Fátima-Ramos, A.; Rodrigues, A.L.; Lembo, L.M. First occurrence of Dasheen mosaic virus (DsMV) in Xanthosoma riedelianum (Mangarito) in Brazil. Mexican Journal of Phytopathology url={https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:258434686}. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila, L.; Herrera, L.; Folgueras, M.; Espinosa, M. Patogenicidad de especies fúngicas presentes en los rizomas de malanga (Xanthosoma y Colocasia). Centro agrícola 2016, 43, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwuanyi, J.O.; Obeta, J.A. Fungi associated with storage rots of cocoyam (Colocasia spp) in Nsukka, Nig. Mycopathol 1996, 134, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulai, M.; Norshie, P. M.; Santo, K. G. Incidence and severity of taro (Colocasia esculenta L.) blight disease caused by Phytophthora colocasiae in the Bono Region of Ghana. International Journal of Agriculture & Environmental Science 2020, 7, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anukworji, C.A.; Ramesh, R. P.; Okigbo, R.N. Isolation of fungi causing rot of cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) and control with plant extracts: (Allium sativum, Garcinia kola, Azadirachta indica, and Carica papaya). Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science 2012, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Foronda, C.C.; Salcedo, L.; Barrera, C.C.G. Evaluación de la actividad antifúngica de extractos etanólicos de paico (Chenopodium ambrosioides), khoa (Clinopodium bolivianum) y ruda (Ruta graveolens) frente a Moniliophthora spp aislada a partir de muestras de cacao con moniliasis. Universidad Mayor de San Andrés http://repositorio.umsa.bo/xmlui/handle/123456789/18259. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hartz, S.; Linares, C.E.; Silva de Loreto, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Thomazi, D.I.; Souza, F.; Santurio, J.M. Utilização do ágar suco de tomate (ágar V8) na identificação presuntiva de Candida dubliniensis. Revista da Sociedad Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 2006, 39, 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Sandoval, R.U. , Gutiérrez-Soto, J.G., Rodríguez Guerra, R., Salcedo-Martínez, S.M., Hernández-Luna, C.E., Luna-Olvera, H.A., Jiménez-Bremont, J.F., Fraire Velázquez, S., & Almeyda-León, I.H. Antagonismo de dos Ascomicetos Contra Phytophthora capsici Leonian, Causante de la Marchitez del Chile (Capsicum annuum L.). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 2010, 28, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- ICONTEC. Bioinsumos para uso agrícola. Extractos vegetales empleados para el control de plagas y enfermedades. Requisitos. 2020.

- Leslie, J. F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Wiley. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Restrepo, M.; Bezerra, J.D.P.; Tan, Y.P.; Wiederhold, N.; Crous, P.W.; Guarro, J.; Gené, J. Re-evaluation of Mycoleptodiscus species and morphologically similar fungi. Persoonia: Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2019, 42, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.C.; Maduewesi, J.N.C. Relation of traditional Methods to the magnitude of storage losses of cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott). Nig. J. Plant Protection. 1990, 13, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Crous, L. , Lombard, F., Sandoval-Denis, M.; Seifert, K.A.; Schroers, H.-J.; Chaverri, P.; Gené, J.; Guarro, J.; Hirooka, Y.; et al. Fusarium: more than a node or a foot-shaped basal cell. Studies in Mycology. 2021, 98, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasali, F. M.; Tusiimire, J.; Kadima, J. N.; Agaba, A. G. Ethnomedical uses, chemical constituents, and evidence-based pharmacological properties of Chenopodium ambrosioides L.: extensive overview. Futur J Pharm Sci. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, R.T.; Farias, I.; Grassia, L.; Franchi, G.; Nowill, A.E.; Bittencourt, C.M.; Wagner, T.M.; de Souza, M.M.; Cruz, A.B.; Malheiros, A. Characterization and evaluation of the cytotoxic potential of the essential oil of Chenopodium ambrosioides. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2015, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Castellanos, J.R. Epazote (Chenopodium ambrosioides). Revisión a sus características morfológicas, actividad farmacológica, y biogénesis de su principal principio activo, ascaridol. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 2008, 7, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Delgado, O.; Alvarado-Pineda, R.L.; Yacarini-Martínez, A.E. Actividad antibacteriana in vitro de extracto etanólico crudo de las hojas de Origanum vulgare, frente Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 y Escherichia coli ATCC 25922. J. Selva Andina Res. Soc. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwenye, U. N.; Elegalam, N.N. Antibacterial activity of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosecoe) and garlic (Allium sativum L.) extracts on Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. J. Molecular Med. and Adv. Sci 2005, 1, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Mishra, A.K.; Dubey, N.K.; Tripathi, Y.B. Evaluation of Chenopodium ambrosioides oil as a potential source of antifungal, antiaflatoxigenic and antioxidant activity. Int J Food Microbiol 2007, 115, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, C. M.; Jham, G. N.; Dhingra, O. D.; Freire, M. M. Composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil of the Brazilian Chenopodium ambrosioides L. J Chem Ecol 2008, 34, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

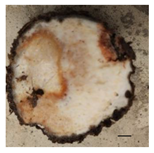

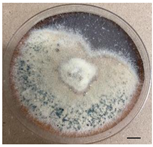

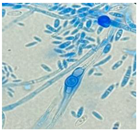

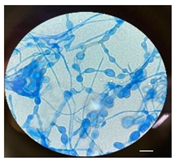

| Causative agent | Symptoms | Macroscopic identification | Microscopic identification. 100X |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium solani |  |

|

|

| Mycoleptodiscus suttonii |  |

|

|

| [%Paico] | % inhibition Fusarium solani | % inhibition Mycoleptodiscus suttonii | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 96 h | 144 h | 48 h | 96 h | 144 h | |

| 7,5 | 12 | 24 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 44 |

| 12,5 | 49 | 52 | 48 | 82 | 93 | 95 |

| 17,5 | 78 | 91 | 94 | 83 | 93 | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).