1. Introduction

Panax Notoginseng is a perennial herb belonging to the family Acanthaceae that has been artificially planted for over 400 years [

1]. Moreover, it exhibits anti-inflammatory and other pharmacological properties and is widely used in the treatment of conditions such as coronary heart disease including angina pectoris [

2,

3,

4]. In recent years, with people being more conscious about health care, the demand for high quality

P.

notoginseng has become more urgent [

5]. However, obstacles related to continuous cropping have seriously restricted the sustainable development of

P.

notoginseng. Agricultural scientists in China have developed a new ecological cultivation model for underforest

P.

notoginseng by intercropping a model of

P. notoginseng and pine forests named PPF, which prioritizes medicinal efficacy by leveraging mutual reinforcement among understory organisms and integrating the ecological requirements for

P. notoginseng growth with the forest ecosystem. Thus, achieving standardized and large-scale production of

P. notoginseng in underforest locations [

8]. The PPF alleviate the land pressure caused by the obstacles of continuous

P. notoginseng cultivation, save production costs, better solve the difficult problems of heavy metals and excessive agricultural residues in traditional cultivation, and improve the quality of

P. notoginseng from the source [

9]. By 2020, the PPF had exceeded 1,333 hm

2, serving as a strong technical strategy for the high-quality production of the medicinal herbs cultivated in underforests based on the principle of habitat diversity for pest control [

10].

The planting process of PPF includes avoiding the use of fertilizers or pesticides. However, the plant remains vulnerable to diseases, significantly impacting both yield and quality. Underground root rot is one of the main diseases affecting the growth and yield of

P. notoginseng in forests, significantly reducing yields [

8]. The incidence rate ranges from 5% to 20%, with severity reaching as high as 60–70%. Research indicates a complex array of pathogens, including

Ilyonectria, Plectosphaerella, Clonostachys, Gibberella, Fusarium, and

Chalara, contributing to

P. notoginseng root rot [

8,

9]. Root rot exacerbates challenges associated with continuous cropping in

P. notoginseng, worsening with each planting cycle. Aboveground, the plant is predominantly affected by black spot and round spot diseases. Black spot disease caused by

Alternaria alternata, it can occur year-round, predominantly affecting leaves. Signs include the formation of round or irregular water-soaked brown spots on leaves, gradually expanding and leading to plant death [

11]. The average annual incidence rate ranges from 20% to 35%, with severe cases exceeding 90% [

12]. Round spot disease, caused by

Mycocentrospora acerina (R. Hartig) Deighton, is a disease with devastating effects on the growth of

P. notoginseng. This disease exhibits a sudden onset and rapid spread, affecting all parts of the plant. Initially, affected leaf spots measure 5–20 mm in diameter, appearing watery, and later develop into brown whorls with a pinpoint-sized center. A transparent point with a needle tip is visible within the lesion, accompanied by a yellow halo at the boundary between diseased and healthy tissue. In humid conditions, lesions turn reddish-brown and develops gray-white mildew on the surface in advanced stages. When multiple lesions occur on leaves, they merge, rot, and eventually detach. Round spot disease leads to annual losses of approximately 20–50%, with severe cases resulting in sterilization [

13]. In 2021, a novel disease,

B. linicola causing

P. notoginseng leaf spots, emerged in the planting base of Lincang City, Yunnan Province, with an incidence rate of 31% and a disease index of 10–20% [

14,

15]. This new disease poses a significant threat to the healthy development of the

P. notoginseng industry in forested areas.

B. linicola is implicated in various plant diseases, including leaf spots in white clover,

Siberian ginseng, and sage, resulting in leaf wilt and production losses [

16,

17,

18]. Tomato stem and leaf rot are also reported due to

B. linicola infection [

19].

The PPF model requires that no chemical agents be used in agricultural production. Research into

P. notoginseng disease control primarily focuses on agricultural, and biological control methods. Biological control offers multiple advantages, such as sufficient resources, low investment, and minimal pollution [

20]. Therefore, the development of biogenic pesticides from plant sources and mineral fungicides has attracted considerable attention. Utilizing biocontrol bacteria such as

Bacillus and

Trichoderma to produce biological control agents shows promise for preventing and managing

P. notoginseng diseases [

21,

22]. Tetramycin, a novel polyene antibiotic, has been isolated from

Streptomyces culture broth, representing a potential advancement in disease management strategies [

23]. It belongs to the group of tetraene macrolide antibiotics, which can inhibit mycelial growth and conidial germination of

Fusarium graminis and

Alternaria, thereby reducing occurrences of wheat scab and kiwifruit rot [

24,

25]. Wood vinegar (WV), comprising water and organic acids, serves as a plant fungicide and insecticide [

26]. WV at a concentration of more than 2.25% can inhibit the mycelial growth and spore germination of

P. ginseng black spot and gray mold bacteria belonging to the family Araliaceae [

27]. Allelopathic substances secreted by pine play an important role in the organic cultivation of

P. notoginseng under forest canopies. The main component of pine needle volatiles, α-pinene, can promote the growth of

P. notoginseng and induce resistance, while α-terpineol, a specific antibacterial component of

Pinus yunnanensis, can significantly inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria. At present, mineral fungicides, mainly Bordeaux liquid, stone sulfur mixture, copper sulfate, and copper pine ester, are widely used. Many copper preparations represent mineral-derived, multi-action site fungicides with outstanding bactericidal performance, low toxicity, low residue, and minimal pollution, thus finding widespread use in plant disease prevention and control [

28].

Therefore, it is necessary to fully understand the occurrence and epidemic characteristics of P. notoginseng leaf spot in order to better provide effective prevention and biological control strategies. In this study, we aimed to explore the biological characteristics, pathogenesis, and biocontrol strategies of pathogenic bacteria causing P. notoginseng leaf spots. Our findings provide scientific insights to support effective prevention and control of P. notoginseng leaf spots in forest environments. It provides the basis for promoting the sustainable, stable, and high-quality development of the Chinese herbal medicine planting industry under the forest.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prevalence and Incidence of B. linicola in Yunnan P. notoginseng Fields

We conducted a census of the understorey

P. notoginseng bases in Lincang, Lancang, and Xundian to assess the occurrence of

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease. At each investigation point, we documented the number of affected plants, disease severity, and total

P. notoginseng plant count. Subsequently, we calculated the incidence rate and severity of the disease, categorizing severity based on spot number and leaf area occupation [

29]. Additionally, we performed a dynamic survey on

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease occurrence in organic

P. notoginseng planted under the forest canopy in Boshang Town, Linxiang District, Lincang City, Yunnan Province (23.70°N, 100.12°E). Starting from the initial stage of leaf spot disease in July, we conducted monthly surveys using a five-point sampling method, with each point covering a 1 m

2 area. We recorded and counted the incidence and severity of

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease (

Table 1). An automatic temperature and humidity recorder (HOBO MX2301A, USA) was installed in the

P. notoginseng forest garden and set to record the temperature and air relative humidity data at hourly intervals. Data were collected once a month to calculate the average, minimum, and maximum monthly temperature and humidity. Two meteorological factors (temperature and relative humidity) affecting the occurrence of leaf spots in

P. notoginseng in 2022 were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation analysis.

Incidence rate is calculated by the following formula:

The severity of the disease is expressed by the disease index, which is calculated according to the following formula:

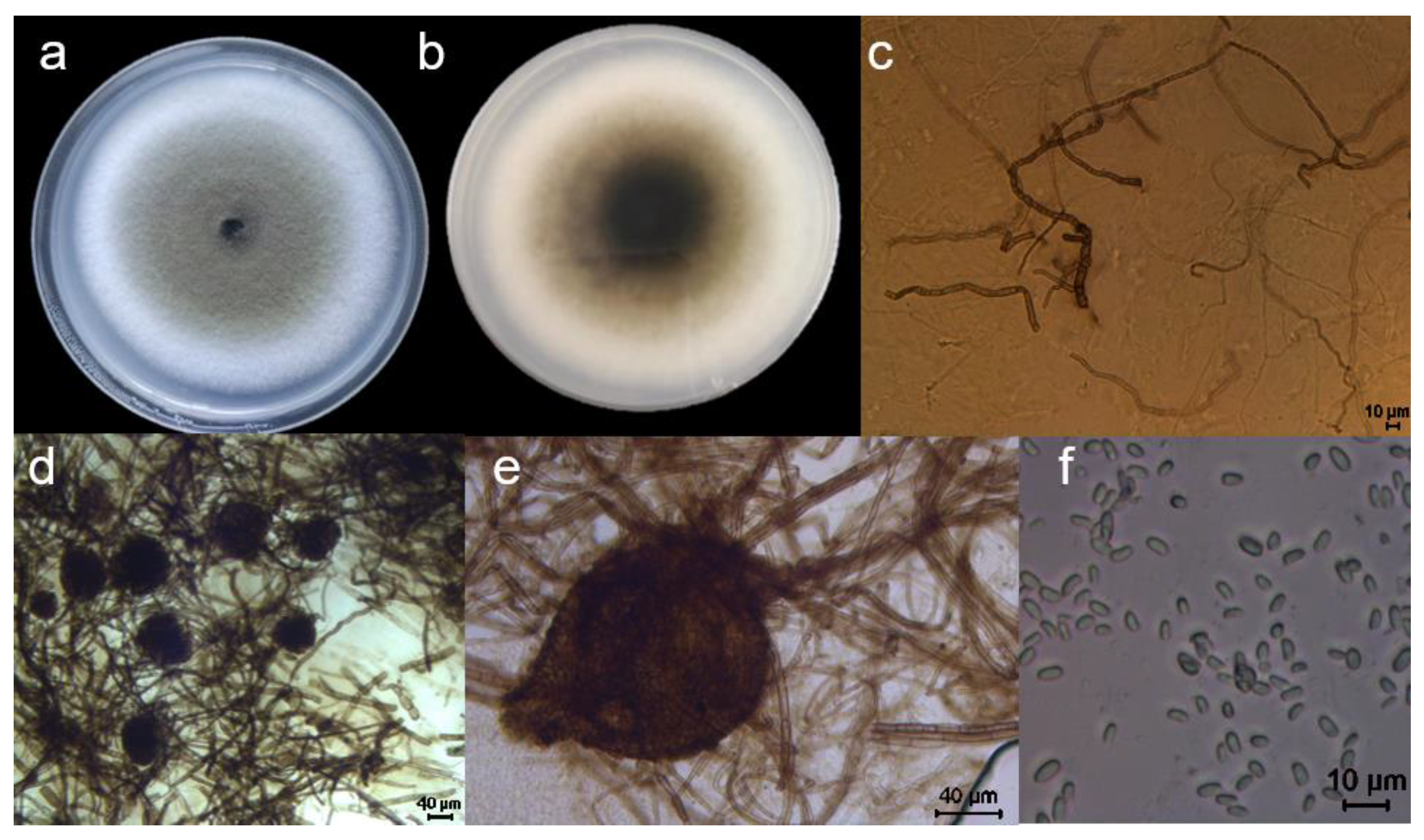

2.2. Morphological Study

P. notoginseng leaf-spotted fungus LYB-2 (B. linicola), isolated from P. notoginseng under the forest of Lincang Xiaodaohe Forest Farm by the National Engineering Research Center of Biodiversity Application Technology, Yunnan Agricultural University, was verified using Koch’s rule.

Strain LYB-2 was activated on a PDA plate and placed in a constant temperature incubator with full illumination (EYELASLI-700, Tokyo, Japan) at 20℃. After 7 d, the morphology, color, and size of the colonies and mycelia were observed via microscopy (Olympus BX43F optical microscope, Japan). Subsequently, the morphology, color, and size of the colonies were examined under a microscope upon conidia and conidiophores production.

2.3. Growth Characteristics at Different Temperatures

The optimum temperatures for representative strains were evaluated. The representative strain on the PDA medium was incubated under varying temperatures of 8°C, 12°C, 16°C, 20°C, 22°C, 26°C, 28°C, 30°C, and 32°C in the dark. When the control colony diameter reached 2/3 of the plate diameter, the cross method was used to measure the colony diameter.

2.4. Growth Characteristics at Different pH Values

The optimum pH for representative strains was assessed. The pH of the medium was adjusted using 1.0 mol/L HCl or NaOH (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). The representative strain was inoculated on PDA medium with pH values of 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0, and 11.0 for the growth assay and sporulation, and then incubated in the dark at 20℃. When the control colony diameter reached 2/3 of the plate diameter, the cross method was used to measure it.

2.5. Study on the Source of B. linicola Primary Infection

2.5.1. Investigation of Infection Sources

The rhizosphere soil from the affected area was collected and sealed in sterile polyethylene bags. The soil was returned to the laboratory for immediate microbial isolation and the detection of pathogenic spores. P. notoginseng leaf spot disease remnants, including P. notoginseng leaves, ground leaves (with obvious spots but no mold layer), stems, taproots, and fibrous roots, were also collected. These samples were placed in sterile paper bags, marked, and brought back to the laboratory. The tissue separation method was used to isolate pathogens and identify the isolates, with five isolates per dish and 10 dishes in total. The growth of pathogenic bacteria in the tissues of the diseased remains was observed, and the number of pathogenic bacterial colonies was recorded. Common plants around the leaf spots of P. notoginseng were collected, especially those with similar signs, and brought back to the laboratory for isolation and identification to determine whether they were intermediate hosts and overwintering sites for pathogenic bacteria.

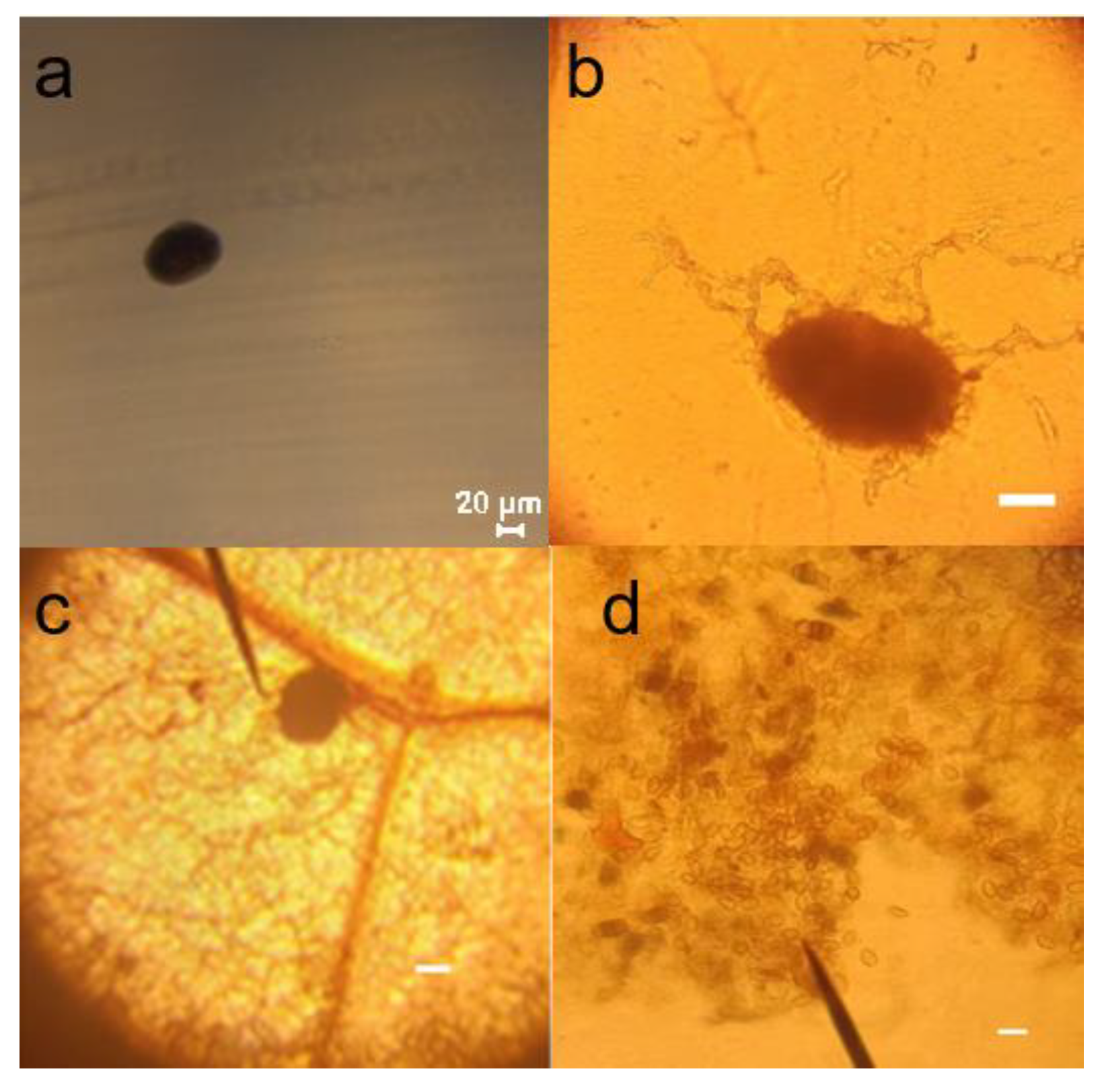

2.5.2. Investigation into Transmission Mode

From August to November 2022, spore traps (Zhejiang Top Cloud-Agri Technology Co., Ltd TPBZ3 Portable spore catcher, Zhejiang, China) were installed at the planting bases of

P. notoginseng in the forest to capture airborne pathogens. The spore catcher was placed on level ground (

Figure 1a). Starting at 8:00 am every day, slides coated with a mixture of carbon tetrachloride and petroleum jelly (100 mL carbon tetrachloride dissolved in 10 g petroleum jelly) were assembled. The number of spores adsorbed on the slides with pathogenic spores of

P. notoginseng leaf spot was determined by changing the slides every day. Full-slide detection was performed using a microscope. A natural collection method was used for auxiliary collection (

Figure 1b). Slides coated with carbon tetrachloride petroleum jelly were placed directly on the ground to collect spores, with five slides being placed under diseased plants. The collection time ranged from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., and the slides were changed daily. Additionally, 5 d per month, slides were viewed under a microscope.

2.6. Sensitivity Testing of B. linicola to Different Fungicides

2.6.1. Determination of Antibacterial Activity of Five Drugs

The antibacterial activities of tetramycin(LiaoningWkioc Bioengineering Co., Ltd, Liaoning, China), copper abietate(Jiangxi Heyi Chemical Co., Ltd, Jiangxi, China), α-terpineol(Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), α-pinene(Sanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), and matrine WV(Shanxi Dewei Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanxi, China) were determined using the mycelium growth rate method. The tested agents were added into PDA medium at a temperature of 40–50 ℃ and then poured into 90 mm diameter Petri dishes. Plates with varying concentrations were prepared, using the same amount of sterile water as the blank control. The concentrations of the tested agents are listed in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. The 5.0-mm diameter mushroom cake was transferred to the center of medicated PDA medium containing different concentration gradients, and unmedicated PDA medium was used as the control group. Each concentration was repeated three times. When the control colony grew to 2/3 of the Petri dish size, the cross method was used to measure the diameter of each treated colony.

2.6.2. Det

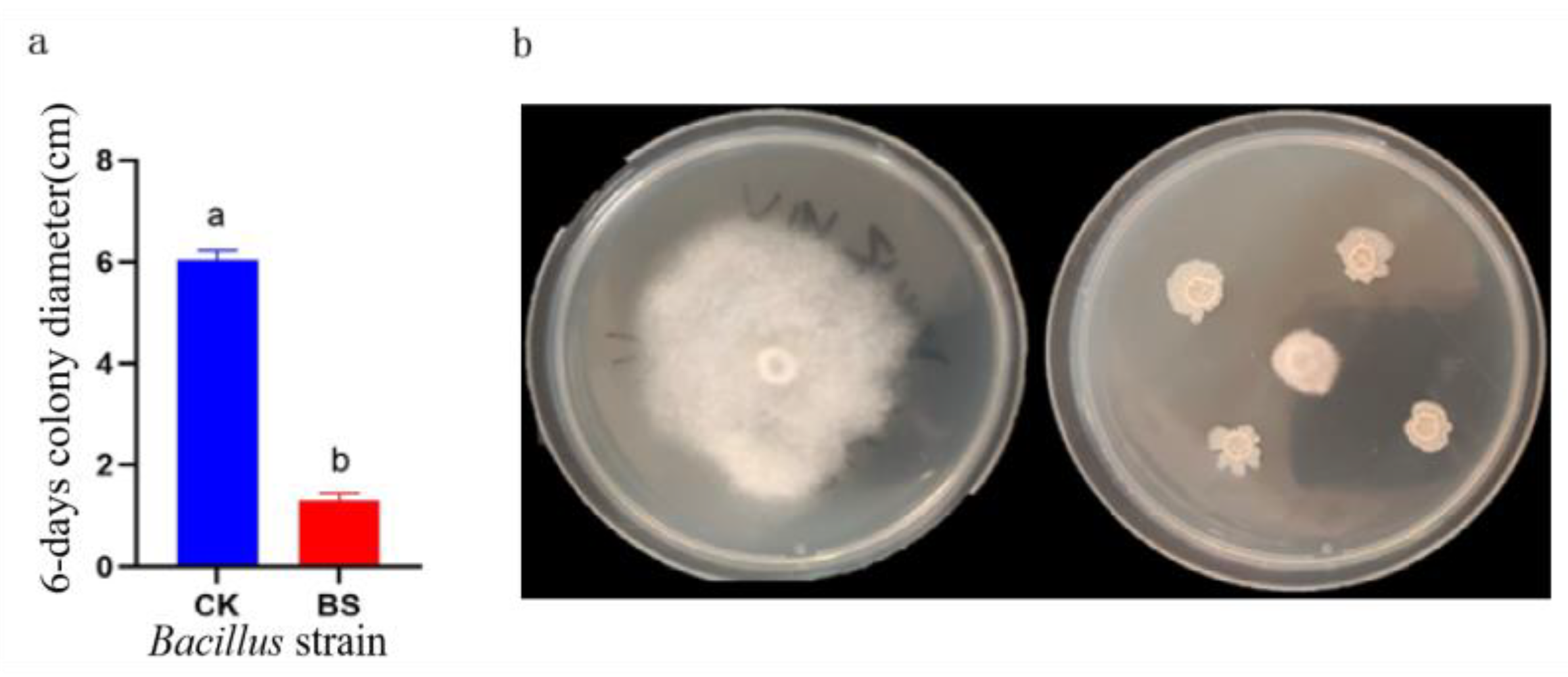

The bacteriostatic activities of

T. harziensis and

B. subtilis were determined using the plate confrontation method.

Trichoderma and

B. subtilis were incubated at 20℃ for three iterations in each treatment. When the control colony grew to 2/3 of the Petri dish size, the diameter was measured using the cross method. The inhibition rate was calculated using the following equation:

The concentration value (mg/L) of each drug was converted into a pair value (X), and the corresponding inhibition rate was converted into a probability value (Y). The regression equation for virulence was established using the least-squares method to calculate the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of each drug.

2.6.3. Field Trials

The experiment was conducted at the Xiasanqi Base of the Liangshan Forest, Boshang Town, Linxiang District, Lincang City, Yunnan Province (23.70°N, 100.12°E). The predominant forest species was Yunnan pine, while the P. notoginseng plants were of 2-year growth, exhibiting similar growth potential. The row spacing of P. notoginseng was maintained at 10–15 cm × 10–15 cm. Uniformity was ensured across experimental plots in terms of soil type, cultivation management, fertilizer application, and water conditions. The primary objective of the trial was to identify leaf spot occurrences in P. notoginseng within forest environments.

By combining the screening results of laboratory agents with the recommended dosage, seven agents including 0.3% tetramycin (LiaoningWkioc Bioengineering Co., Ltd, Liaoning, China), 300 million CFU/g

Trichoderma kirhartz (BioWorks, Inc., USA), 10 billion CFU/g

Bacillus quinquefolium (BioWorks, Inc., USA), 20% copper abietate (Jiangxi Heyi Chemical Co., Ltd, Jiangxi, China), 99% α-terpineol(Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), 97% α-pinene (Sanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China), and matrine WV (Shanxi Dewei Biochemical Co., Ltd, Shanxi, China), were selected and diluted to different concentrations.

Table 3 lists the treatments administered for each drug.

The plots of the experimental agents and blank control were arranged according to random combinations; the plot area was 1.2 m × 5 m, each agent was applied three times, and each treatment was repeated three times. A knapsack sprayer was used to spray under still or breezy weather conditions, avoid applications under high temperature, humid, or rainy conditions to ensure even coverage of the liquid on the leaves of

P. notoginseng. To verify the efficacy of the agent, application was scheduled before the peak occurrence of

P. notoginseng leaf spot under the forest, specifically on October 25, with application occurring once. We selected 80–120

P. notoginseng plants in the plot to perform a fixed-point survey according to the proportion of the disease site to the whole plant. The total number of plants and the number of different disease levels were recorded. The grading criteria for leaf spots of

P. notoginseng were consistent with those described in

Section 2.1. The disease-based survey was conducted 1 d before application and repeated 15 d after application.

The incidence and disease index were calculated in the same manner as described in

Section 2.1, using the following formulas:

The disease index growth rate and prevention and treatment effect are calculated according to the following formula:

where pt0, pt1, CK0, and CK1 represent the disease index before application to the treatment area, the disease index after application to the treatment area, the disease index before application to the control area, and the disease index after application to the control area, respectively.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Excel 2019 and SPSS 19.0. Graphing was conducted using GraphPad 9.0. One-way analysis of variance and multiple comparisons were performed to evaluate the levels of significance level among the samples. DPS V9.5 was used to calculate the virulence regression equation and EC50 values. All tests were repeated thrice.

4. Discussion

Boeremia, formerly referred to as

Phoma. comprises mostly pathogenic species affecting various host plants, including fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants. These pathogens induce rot, necrosis, wilt, and ulcers in fruits, leaves, stems, and roots, significantly impeding plant growth and development. Notably,

B. exigua causes leaf spots in Brazilian sweet potatoes, peas,

Dumasia villosa, and ginseng [

30,

31,

32,

33], while

B. lilacis induces ash necrosis [

34].

B. strasseri causes root rot in mint [

35],

B. exigua var.

Pseudolilacis causes black rot in vegetable thistle [

36], and

B. linicola primarily affects

P. notoginseng during its late growth stage. The weakened growth potential of

P. notoginseng during this period predisposes it to pathogenic bacterial colonization, leading to disease. Under favorable conditions, such as wet soil, the incidence of

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease can reach 80%, posing a severe threat to its cultivation and production. Growers must pay close attention to the disease and implement timely prevention and control measures to reduce economic losses.

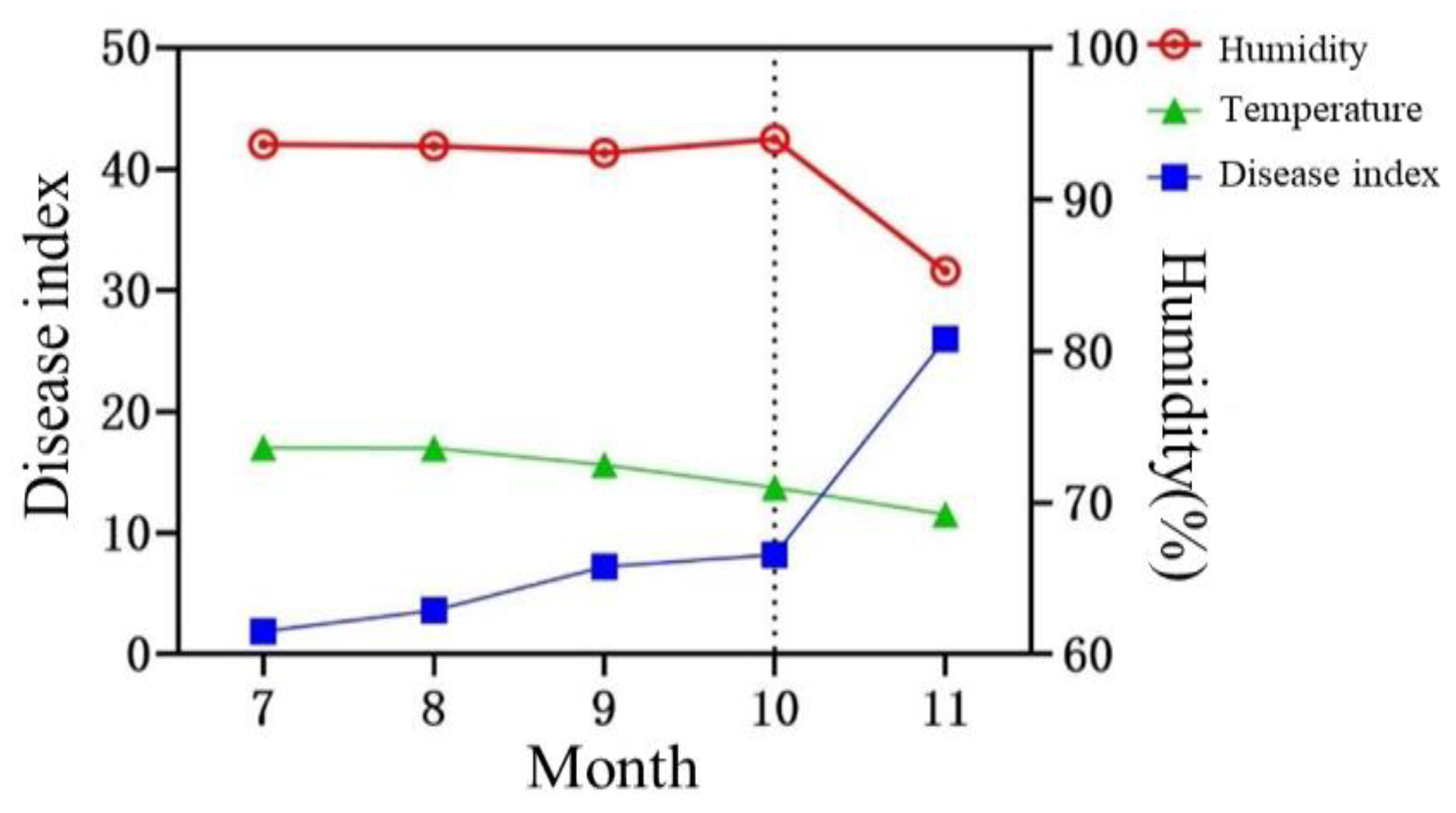

Wet soil conditions significantly favor the growth and survival of

B. exigua [

37]. Malcolmson et al. studied the relationship between soil moisture in eastern Scotland and the distribution of potato gangrene caused by this bacterium. They found that the incidence of this disease was the highest in the northeast region with the highest humidity. Similar considerations apply to low-temperature conditions in northeast China [

38]. This finding is consistent with the results of this study, which found that the organic

P. notoginseng planting base in Lincang forest has a high altitude, abundant rainfall, perennial humidity above 90%, and annual temperature below 20℃. We speculated that temperature and humidity are key meteorological factors affecting the occurrence and prevalence of

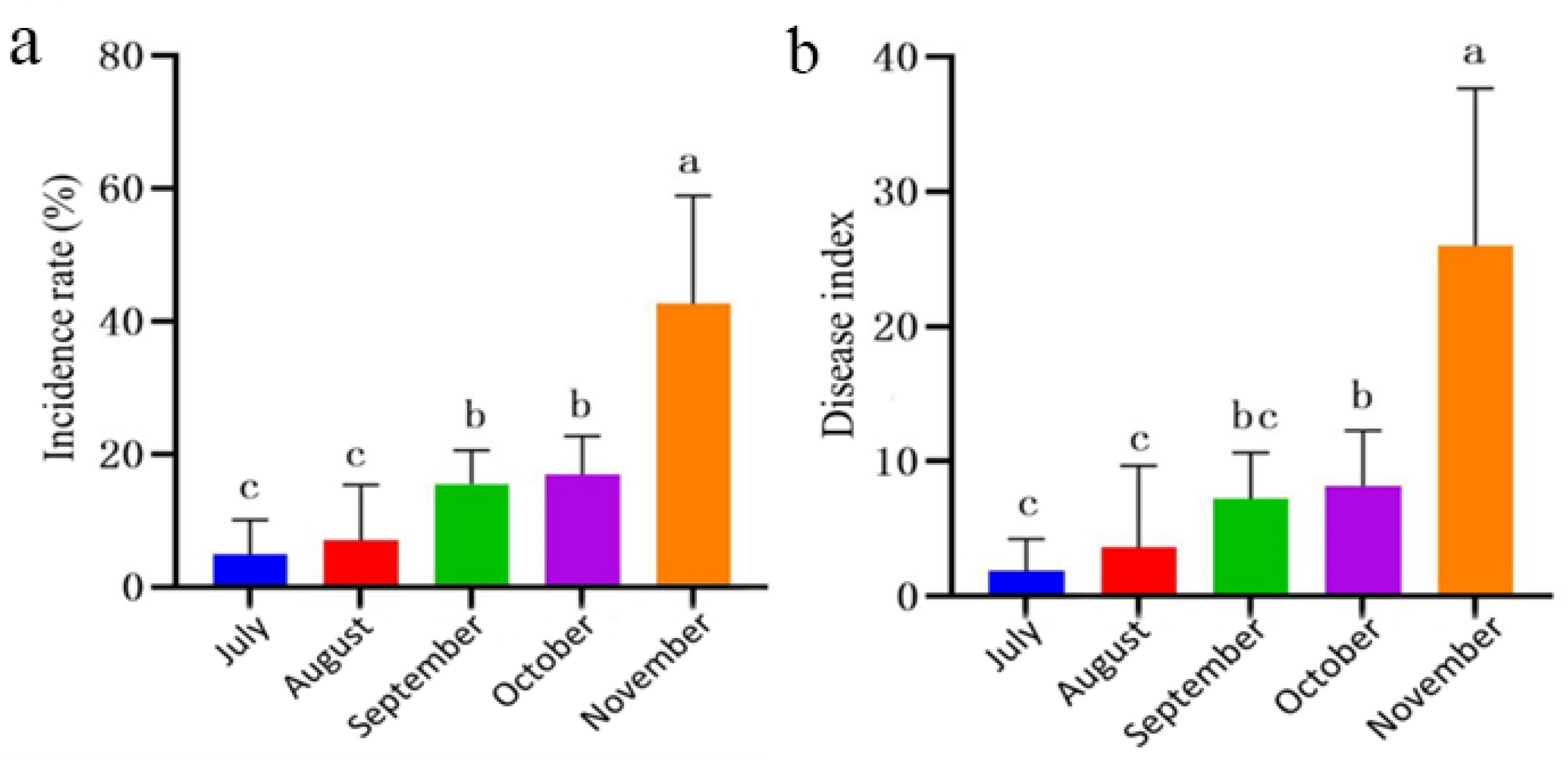

P. notoginseng leaf spots in forests. In this study, the correlation between temperature and humidity and the occurrence of diseases was further analyzed, and the results showed that under high humidity conditions, temperature markedly affected the occurrence of leaf spots in the forest and was the decisive factor. Disease occurrence is the primary basis for disease prevention and control. By analyzing disease occurrences in previous years, it becomes feasible to predict future outbreaks, enabling the implementation of timely forecasting, prevention, and control measures. In our study, we investigated the occurrence of leaf spot disease in

P. notoginseng within forest environments. Our findings revealed that the disease typically initiates in mid-July, with October representing a pivotal period and November marking the peak occurrence. To effectively manage the disease, control measures should be implemented before the peak period. Thus, October 15 was identified as the optimal date for preventive and control interventions in this study.

Trichoderma and

Bacillus are widely used biological control agents. For example,

B. subtilis BS06 can effectively control soybean root rot caused by

Fusarium oxysporum [

39]. Another strain,

B. subtilis WZZ-6, exhibited a high control rate of 72% against

P. notoginseng root rot, achieving a remarkable 100% control effect in both in vitro tuber and plant assays [

40]. Additionally, species such as

T. koningiopsis, T. atroviride, and

T. harzianum have demonstrated inhibitory effects on the growth of

P. notoginseng root rot caused by

F. Solani, Ilyonectria destructans, and

Phytophthora cactorum. Field treatments with

Trichoderma and

Bacillus have been shown to increase

P. notoginseng biomass [

41].

Trichoderma and

Bacillus control the occurrence of diseases mainly through nutrition and space competition, the production of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and enzymes [

41,

42,

43].

B. subtilis JK-14 enhances the resistance of peaches by both inhibiting the growth of postharvest crop disease pathogens such as

Alternaria, Tenuis, and

Botrytis cinerea and activating defense-related enzymes to reduce disease occurrence [

44].

B. subtilis M4 produces iturin to reduce the damage of postharvest gray mold in apples and

Pythium ultimum in soybean seedlings. Furthermore, tetramycin, an antibiotic fungicide, induces the activity of defense-related enzymes to improve disease resistance in plants [

45]. Moreover, purified cell wall-degrading enzymes such as chitinase and glucanase from different

T. harzianum strains can effectively inhibit spore germination and mycelial growth of pathogens such as

Fusarium, Alternaria, and

Botrytis [

46].

Tetramycin can effectively inhibit mycelial growth, spore germination, and bud tube elongation in

Colletotrichum scovillei, a pepper anthracnose pathogen, exerting its antifungal activity by destroying the cell membrane structure [

47]. It also has a significant inhibitory effect on

P. notoginseng root rot [

48]. Additionally, α-terpinol inhibits the mycelial growth and spore germination of

Aspergillus niger and disrupts cell membrane permeability, thereby reducing pathogen infection [

49]. WV demonstrates significant control over

Fusarium wilt in tomatoes, leading to increased tomato yields and reduced activities of MDA and H

2O

2 in tomato leaves. Moreover, WV enhances disease resistance in tomato leaves by increasing the activities of catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase [

50]. Additionally, α-pinene in Zanthoxylum oil inhibits the growth of

F. sulphureum mycelia, disrupts cell membrane integrity, and inhibits spore germination, effectively controlling potato dry rot [

51]. Copper abresinate, with its main active component being copper ions, alters membrane permeability and interferes with enzymatic reactions and respiratory activities, thus inhibiting spore germination [

52]. According to the relevant provisions of the organic product standard GB/T 19630-2019 [

53], this study selected plant protection products suitable for use in the production of organic plants to determine their bacteriostatic effectiveness indoors and verify field control effectiveness.

B. subtilis, tetramycin, α-terpinol, WV, and

Trichoderma exhibited superior inhibition effects on the mycelial growth of

P. notoginseng leaf spot pathogens. The field control results showed that each agent and biocontrol strain had a certain control effect on leaf spot in

P. notoginseng, but there were differences between the agents and biocontrol bacteria. Among them, the control effect of 20% copper abresinate at 500× dilution was significantly higher than that of other products, reaching 82.57%. Moreover, the control effects of

B. subtilis 0.15g/m

2,

T. atroviride BH-10 preparation 0.15 g/m

2, and 0.3% tetramycin 500× dilution were above 70%. These three biological control measures effectively reduced the occurrence and spread of

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease. In summary,

P. notoginseng leaf spot can be effectively controlled by adding 20% copper abietate 500× dilution, 10 billion CFU/g

B. subtilis at 0.15g/m

2, 300 million CFU/g T

. atroviride BH-10 preparation at 0.15 g/m

2, and 0.3% tetramycin 500× dilution.

Figure 1.

Methods of spore capture. (a) Using a spore trap device; (b) Glass slide natural collection.

Figure 1.

Methods of spore capture. (a) Using a spore trap device; (b) Glass slide natural collection.

Figure 2.

Signs of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease across different growth years. (a) Three-year-old P. notoginseng; (b) Two-year-old P. notoginseng; (c, d). Leaf spot signs.

Figure 2.

Signs of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease across different growth years. (a) Three-year-old P. notoginseng; (b) Two-year-old P. notoginseng; (c, d). Leaf spot signs.

Figure 3.

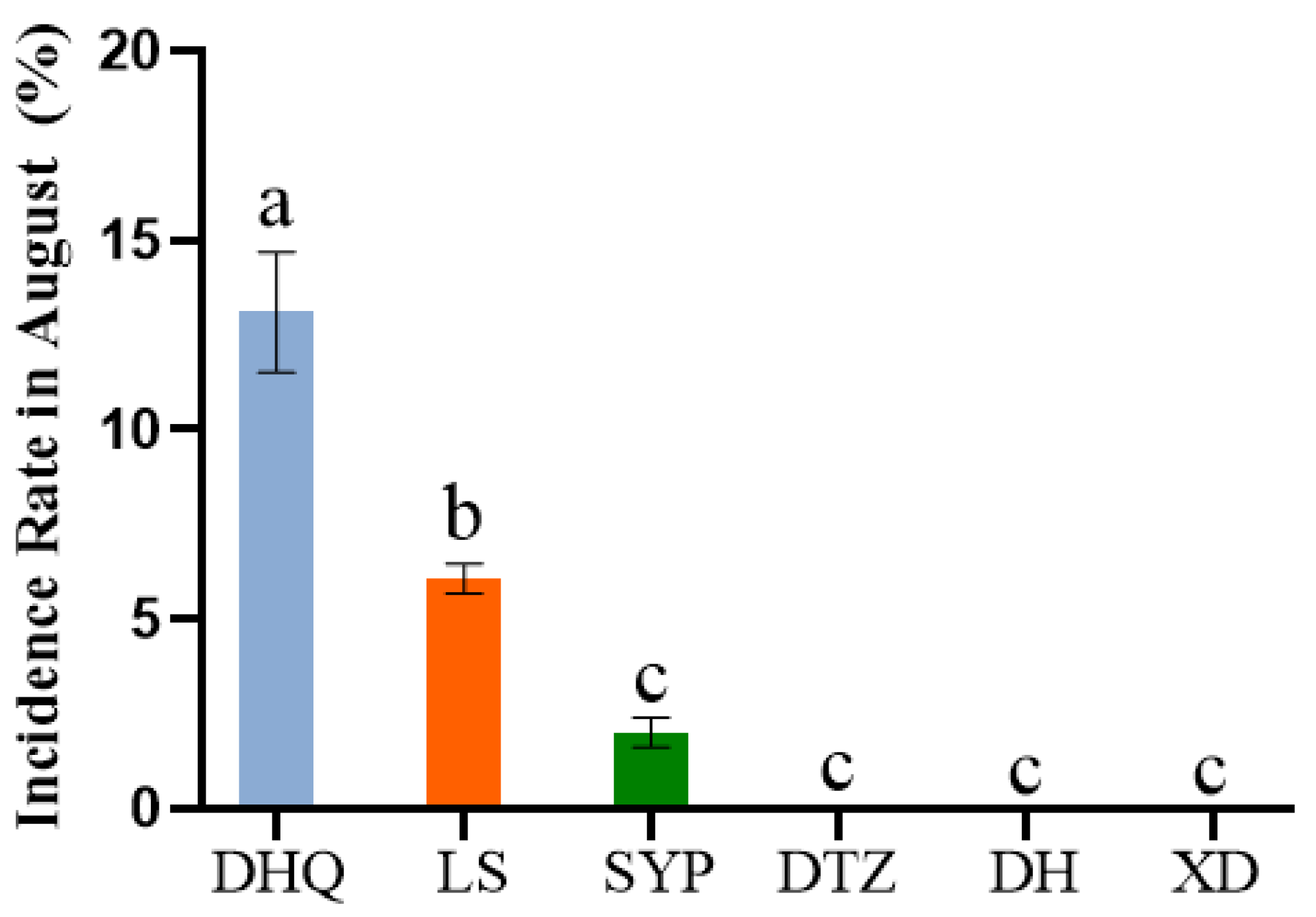

Occurrence of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease across various planting bases. XD: Bo Shang Dao River; LS: Bo Shang Liang Mountain; SYP: Bo Shang Shuang Ying Pan; DTZ: Lan Cang Da Tang Zi; DH: Lan Cang Dong Hui; XD: Xun Dian. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Occurrence of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease across various planting bases. XD: Bo Shang Dao River; LS: Bo Shang Liang Mountain; SYP: Bo Shang Shuang Ying Pan; DTZ: Lan Cang Da Tang Zi; DH: Lan Cang Dong Hui; XD: Xun Dian. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Incidence of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease in forest environments. (a) Incidence rate; (b) Disease index. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Incidence of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease in forest environments. (a) Incidence rate; (b) Disease index. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

The relationship between temperature, humidity, and disease index of P. notoginseng leaf spot.

Figure 5.

The relationship between temperature, humidity, and disease index of P. notoginseng leaf spot.

Figure 6.

Morphological features of LYB-2 grown on PDA medium for 7 d. (a) Top view of the medium; (b) back view of the medium; (c) mycelium; scale bar = 10 μm.(d, e) conidiophore; scale bar = 40 μm. (f) conidia; scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 6.

Morphological features of LYB-2 grown on PDA medium for 7 d. (a) Top view of the medium; (b) back view of the medium; (c) mycelium; scale bar = 10 μm.(d, e) conidiophore; scale bar = 40 μm. (f) conidia; scale bar = 10 μm.

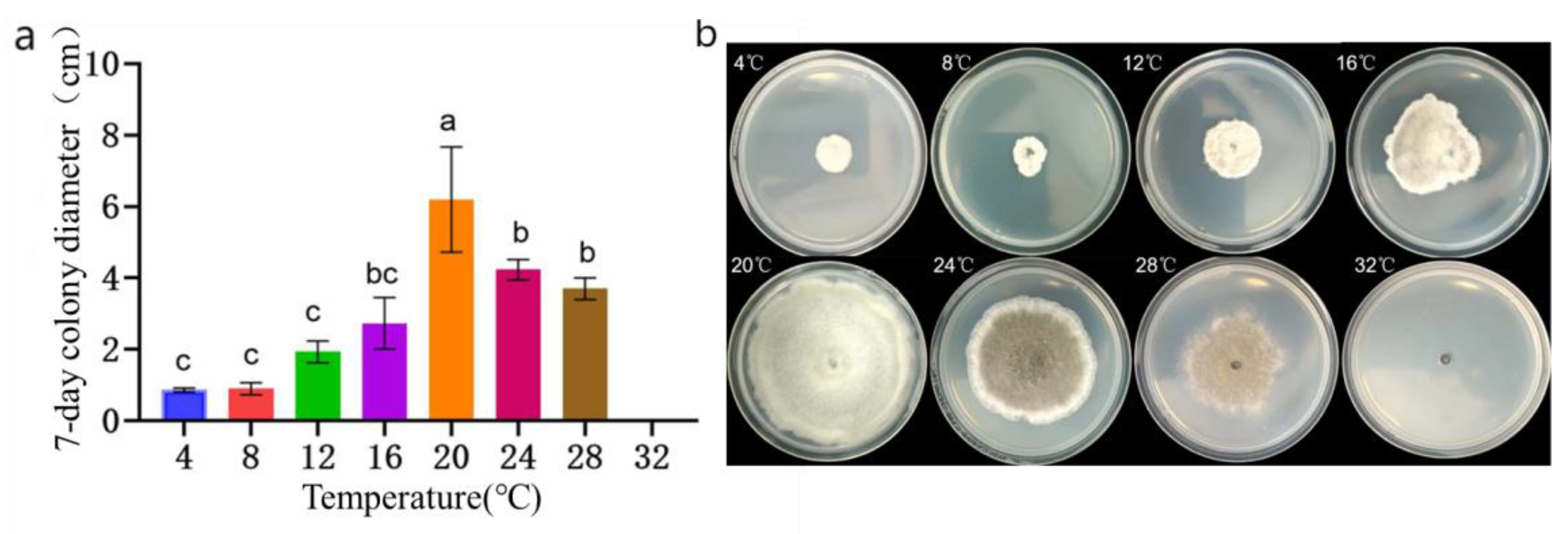

Figure 7.

Colony morphology and diameter of the representative strain LYB-2 at different temperatures. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 7.

Colony morphology and diameter of the representative strain LYB-2 at different temperatures. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

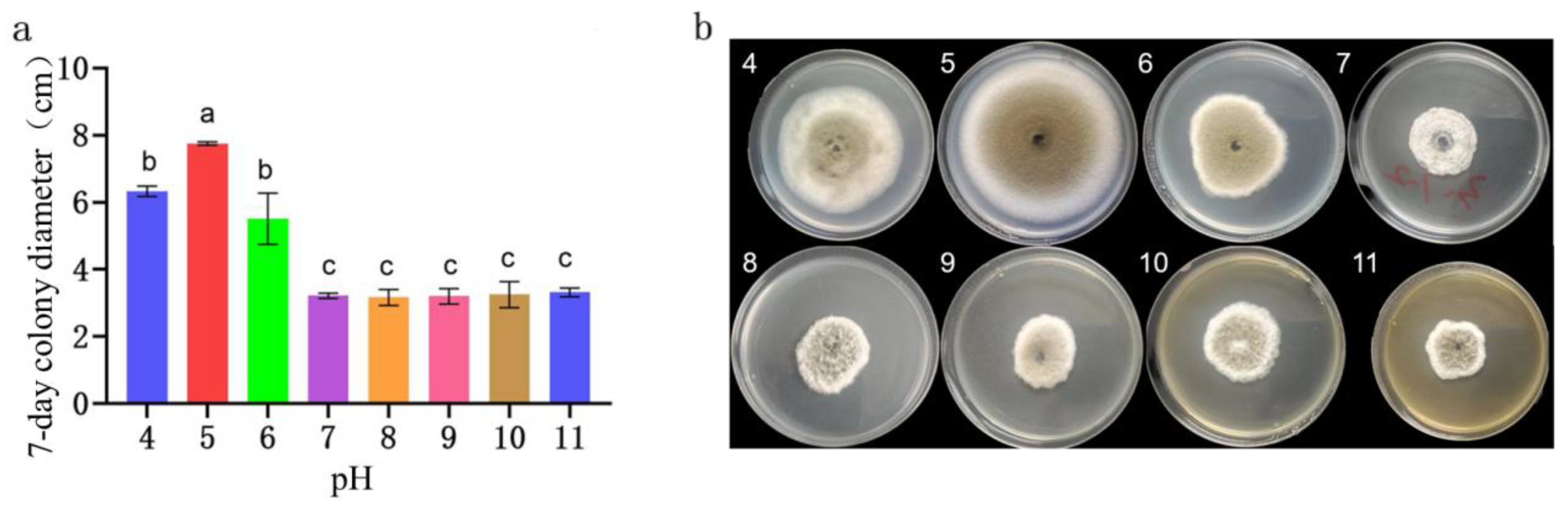

Figure 8.

Colony morphology, diameter of the representative strain LYB-2 at different pH values. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Colony morphology, diameter of the representative strain LYB-2 at different pH values. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

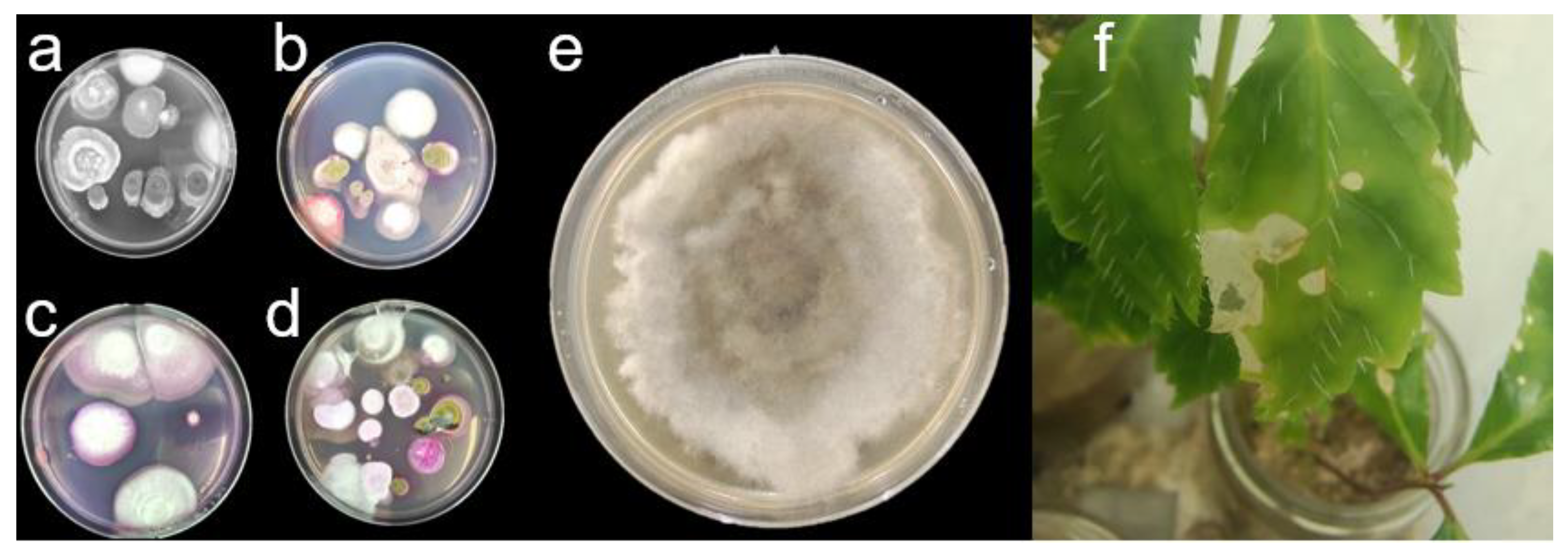

Figure 9.

Isolation of culturable fungi in the rhizosphere soil of diseased P. notoginseng. (a–d) Colonies formed at different dilution concentrations; (e) Purified pathogenic fungal colonies; (f) Pathogenicity determination of the isolate.

Figure 9.

Isolation of culturable fungi in the rhizosphere soil of diseased P. notoginseng. (a–d) Colonies formed at different dilution concentrations; (e) Purified pathogenic fungal colonies; (f) Pathogenicity determination of the isolate.

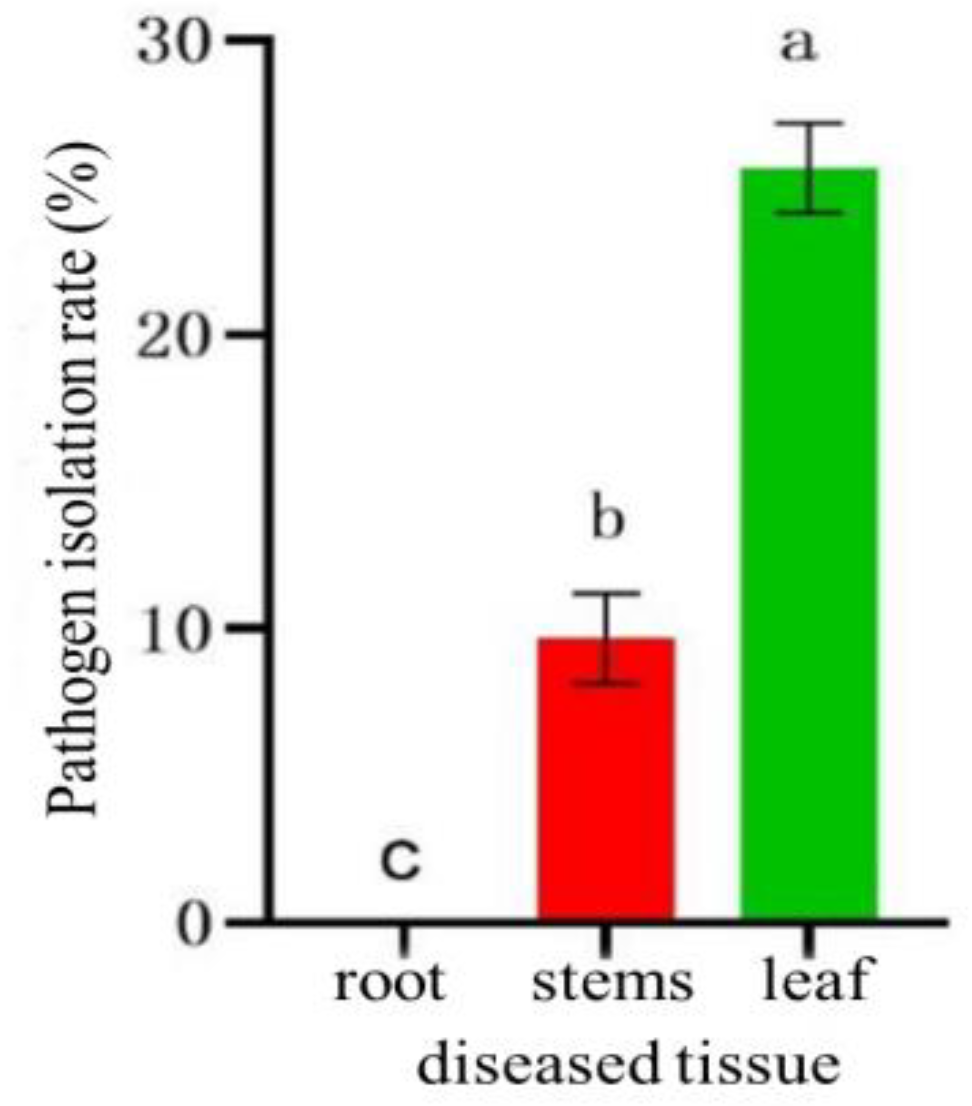

Figure 10.

Isolation rate of pathogenic fungi on different diseased tissues. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 10.

Isolation rate of pathogenic fungi on different diseased tissues. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

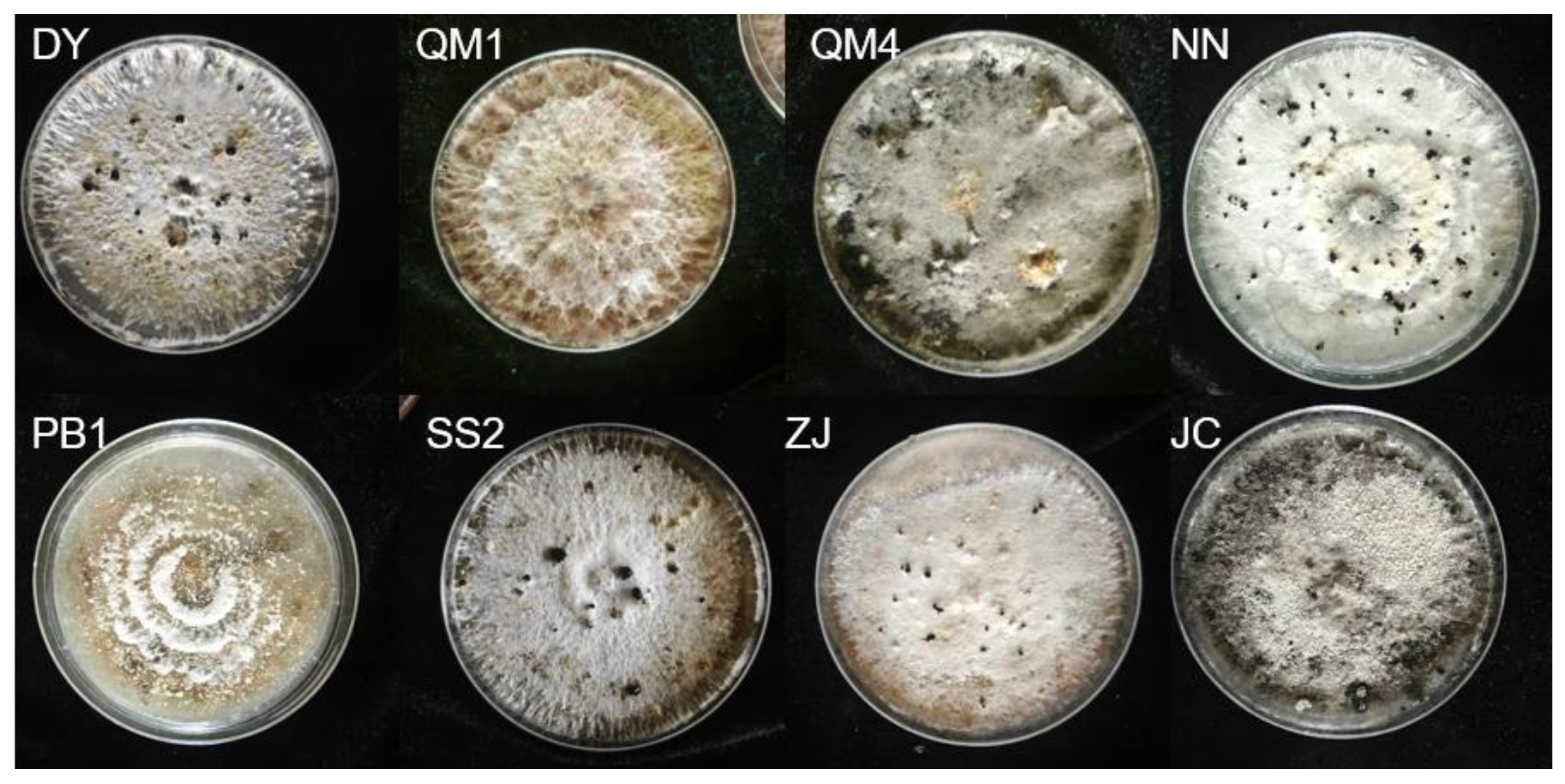

Figure 11.

Fungal isolation on different diseased plants. DY: Duoyi tree; QM: Spartina; PB1: loquat tree; SS: pine; ZJ: Eupatorium adenophorum; NN: Polygonum nepalense; JC: Jincai.

Figure 11.

Fungal isolation on different diseased plants. DY: Duoyi tree; QM: Spartina; PB1: loquat tree; SS: pine; ZJ: Eupatorium adenophorum; NN: Polygonum nepalense; JC: Jincai.

Figure 12.

Microscopic examination of sclerotium and conidia. (a, b) Conidiophore on slides, scale bar = 20 μm; (c) Conidiophore on the lesion, scale bar = 20 μm; (d) Conidia on slides, scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 12.

Microscopic examination of sclerotium and conidia. (a, b) Conidiophore on slides, scale bar = 20 μm; (c) Conidiophore on the lesion, scale bar = 20 μm; (d) Conidia on slides, scale bar = 10 μm.

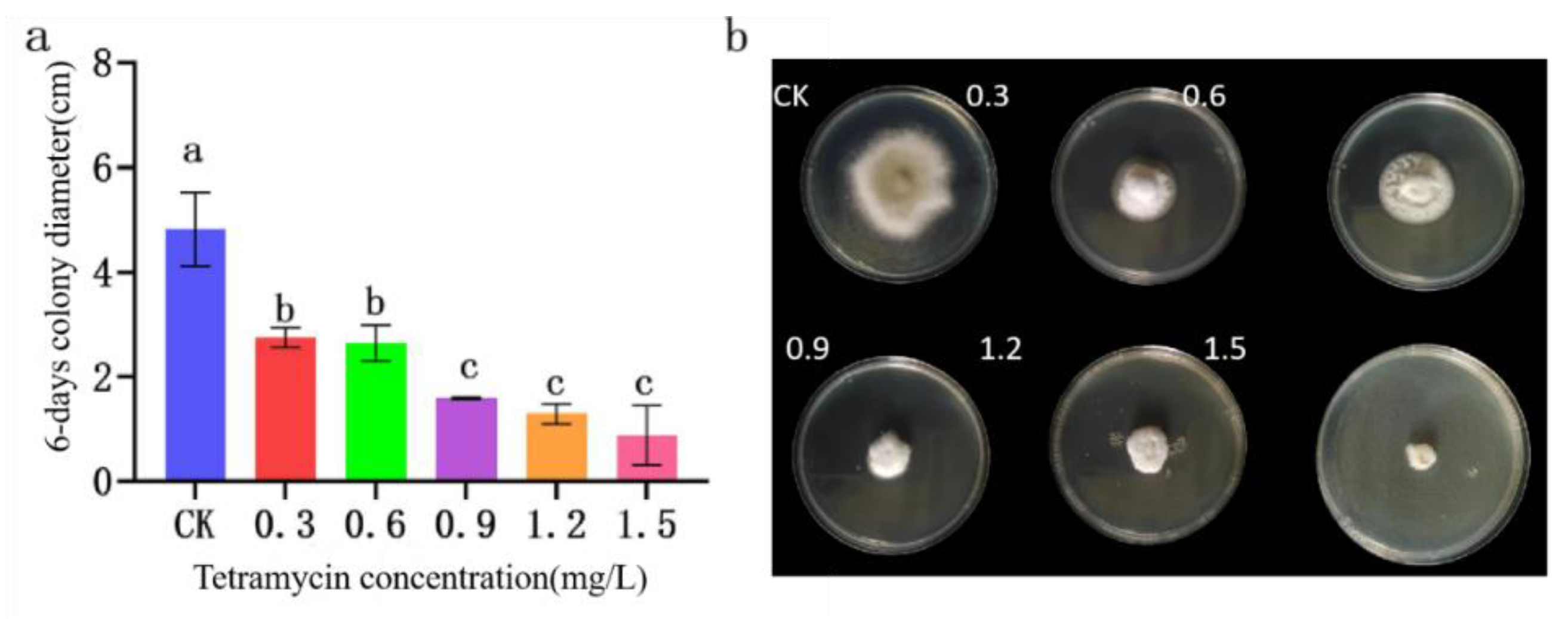

Figure 13.

Effect of tetramycin on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 13.

Effect of tetramycin on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

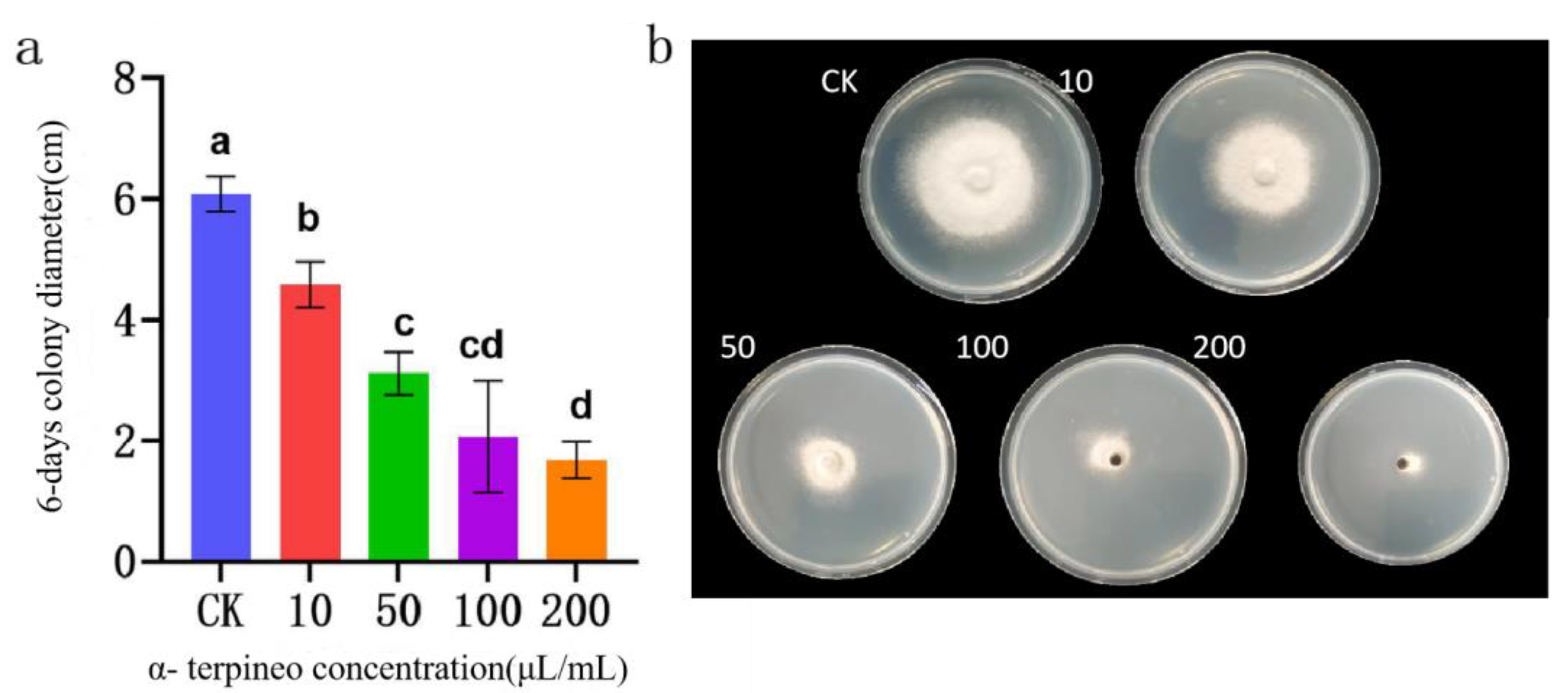

Figure 14.

Effect of α-terpineol on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2 (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 14.

Effect of α-terpineol on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2 (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

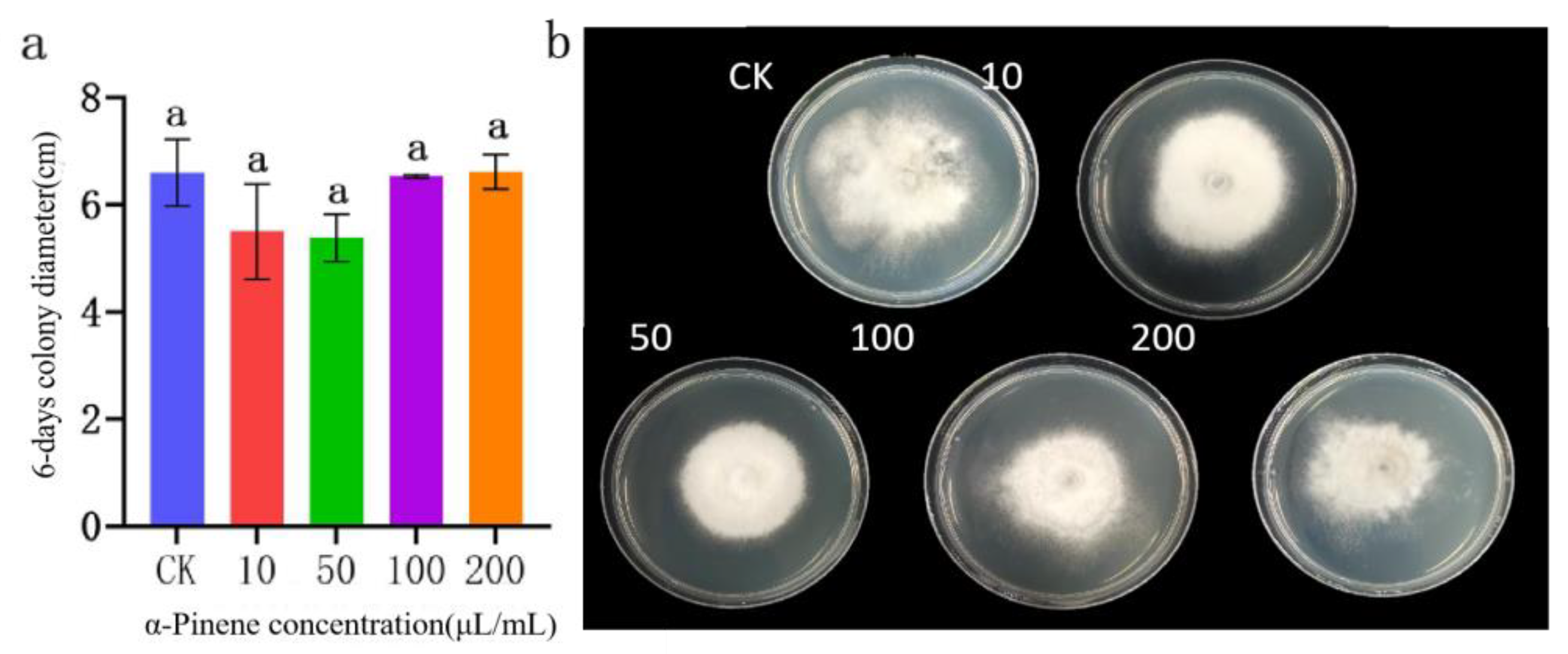

Figure 15.

Effect of α-pinene on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 15.

Effect of α-pinene on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

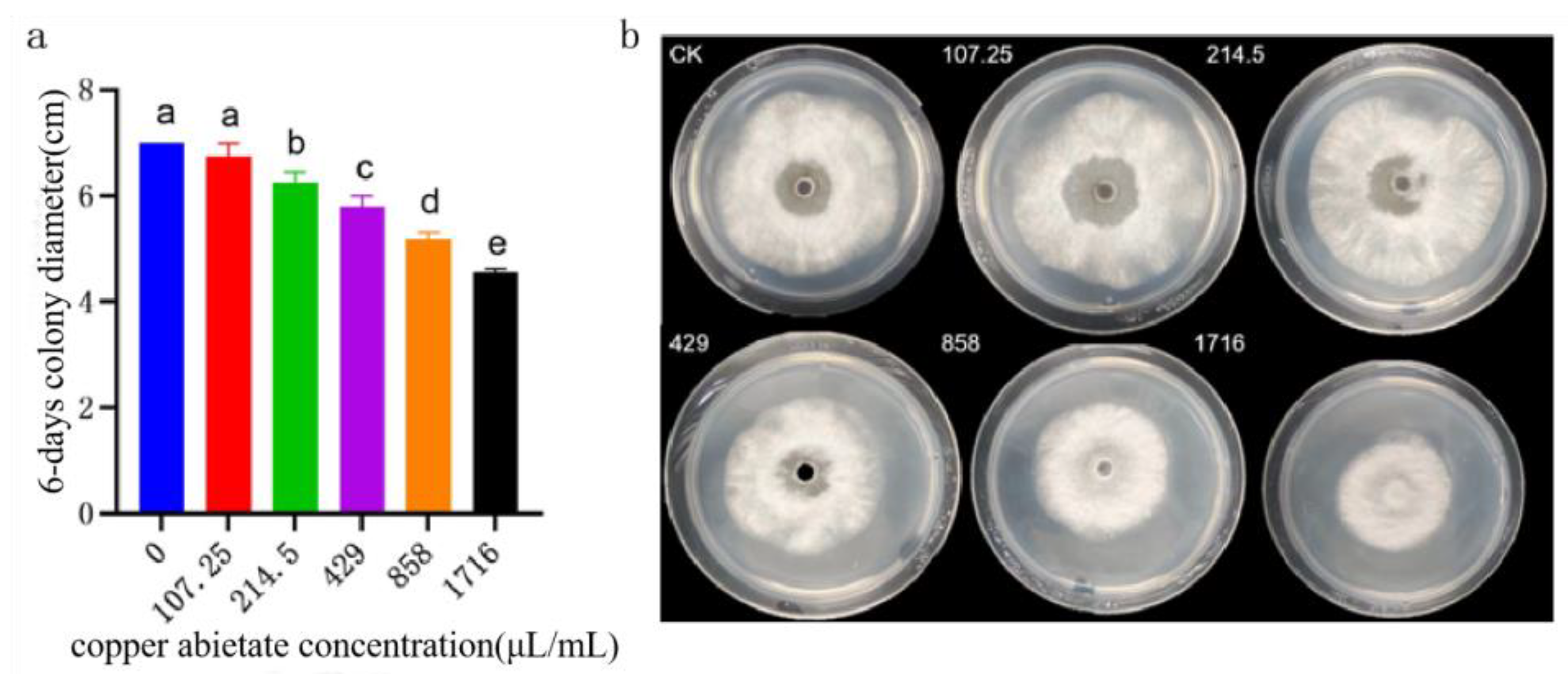

Figure 16.

Effect of copper abietate on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 16.

Effect of copper abietate on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 17.

Effect of WV on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter;(b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 17.

Effect of WV on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter;(b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

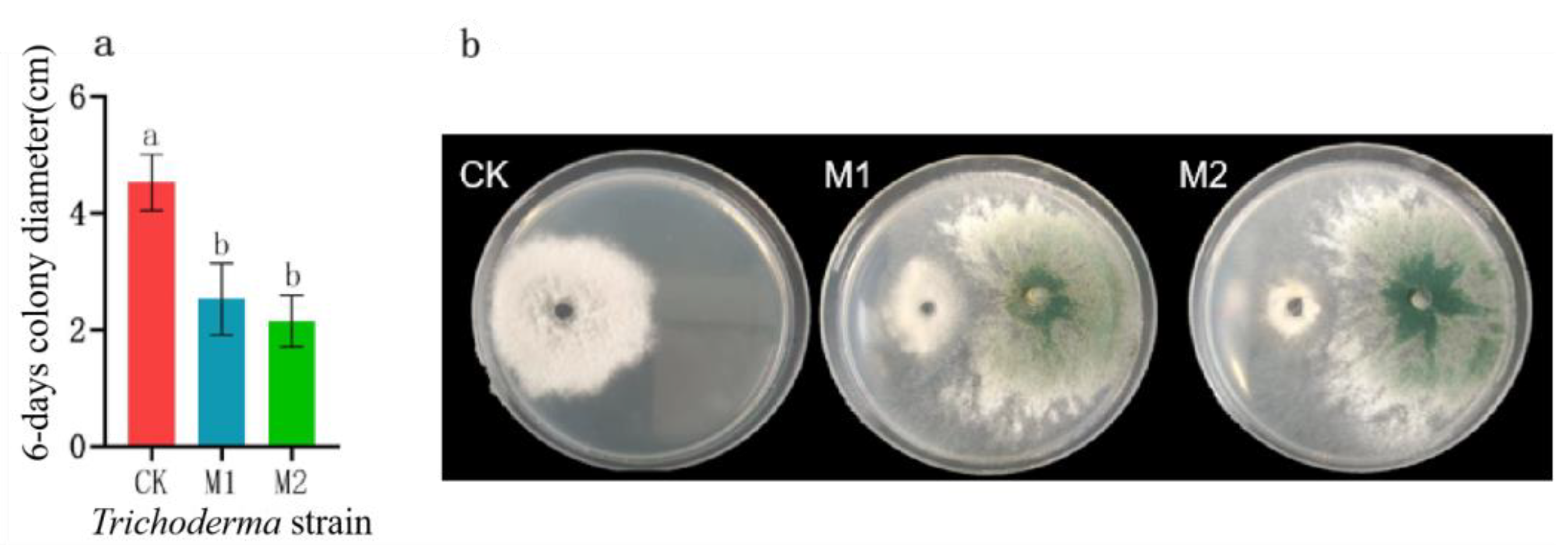

Figure 18.

Effect of Trichoderma on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2 under co-cultivation. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology; M1: Trichoderma atroviride; M2: Trichoderma harzianum. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 18.

Effect of Trichoderma on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2 under co-cultivation. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology; M1: Trichoderma atroviride; M2: Trichoderma harzianum. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

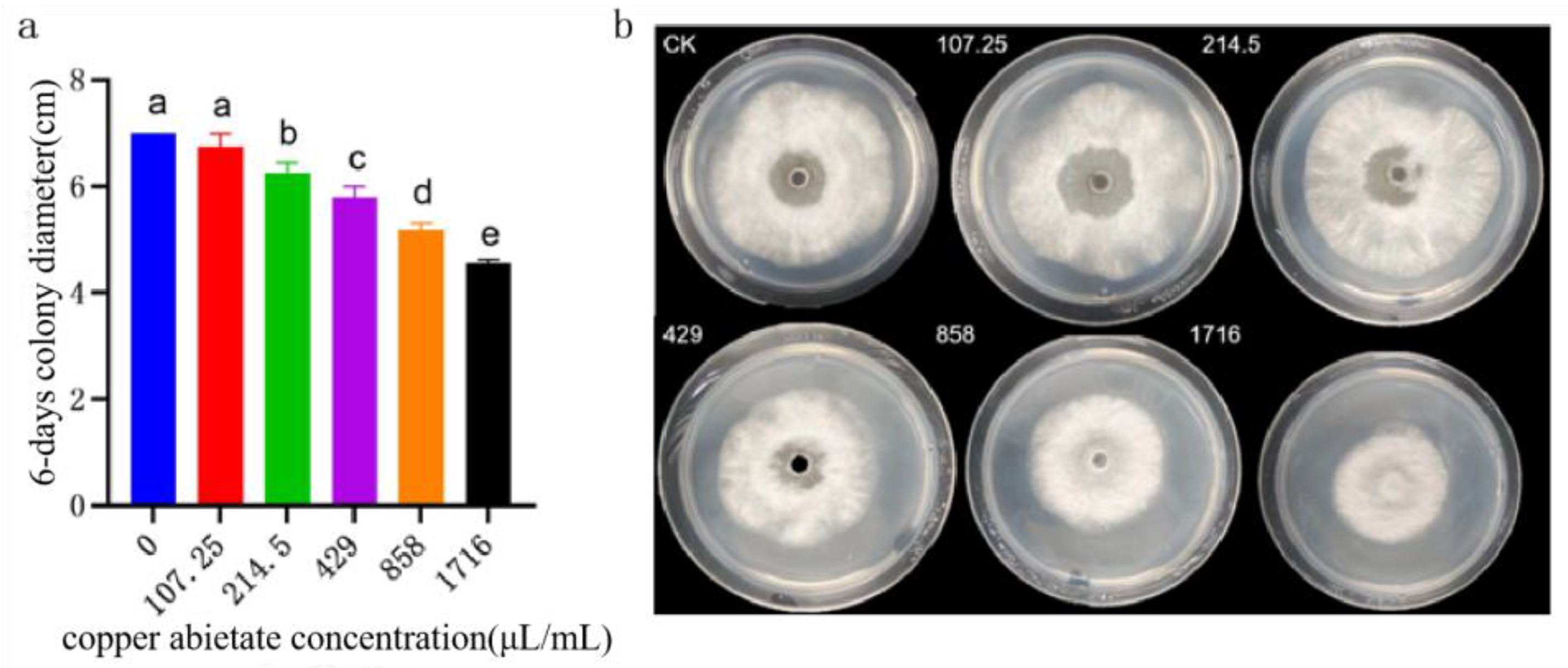

Figure 19.

Effect of copper abietate on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Figure 19.

Effect of copper abietate on the colony growth of B. linicola LYB-2. (a) Colony diameter; (b) Colony morphology. Values of ±standard error are presented with error bars, and different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Table 1.

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease severity grading.

Table 1.

P. notoginseng leaf spot disease severity grading.

| Incidence level |

Incidence degree |

Representative value |

| 1 |

No or virtually no spots |

0 |

| 2 |

Spots are small, 1–2 spots per leaf, less than 5% of leaf area |

1 |

| 3 |

More than 2 spots per leaf, 5–25% of leaf area |

2 |

| 4 |

Spots cover 25–50% of leaf area, leaves do not fall off, or 1/3 of the stem is diseased |

3 |

| 5 |

Spots occupy more than 50% of the leaf area, some or all of the leaves fall off, only the stem remains or the plant dies |

4 |

Table 2.

Concentration settings of the seven agents on the hyphal growth of P. notoginseng leaf spot pathogens.

Table 2.

Concentration settings of the seven agents on the hyphal growth of P. notoginseng leaf spot pathogens.

| Tested agent |

Concentration gradient |

Unit |

| Tetramycin |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

mg/L |

| copper abietate |

107.25 |

214.5 |

429 |

858 |

1,716 |

mg/L |

| α-terpineol |

10 |

50 |

100 |

200 |

— |

μL/mL |

| α-pinene |

10 |

50 |

100 |

200 |

— |

μL/mL |

| Sophora flavescens alt WV |

5,000 |

10,000 |

20,000 |

40,000 |

— |

mg/L |

Table 3.

Treatment concentration of tested agents.

Table 3.

Treatment concentration of tested agents.

| Treatment number |

Test agent |

Treatment concentration |

Treatment method |

| TCK |

Clear water control |

— |

Atomizing |

| T1-1 |

0.3% tetramycin |

500× |

| T1-2 |

1,000× |

| T1-3 |

2,000× |

| T2-1 |

20% copper abietate |

500× |

| T2-2 |

1,000× |

| T2-3 |

2,000× |

| T3-1 |

α-terpineol |

10,000× |

| T3-2 |

25,000× |

| T3-3 |

50,000× |

| T4-1 |

α-pinene |

10,000× |

| T4-2 |

25,000× |

| T4-3 |

50,000× |

| T5-1 |

Sophora flavescens alt WV |

300× |

| T5-2 |

600× |

| T5-3 |

900× |

| T6-1 |

T. harzianum |

100 g/acres |

| T6-2 |

T. atroviride |

100 g/acres |

| T7-1 |

B. subtilis |

100 g/acres |

Table 4.

Correlation analysis between meteorological factors and the severity of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease.

Table 4.

Correlation analysis between meteorological factors and the severity of P. notoginseng leaf spot disease.

| Meteorological factor |

Pearson correlation coefficient |

| Mean monthly temperature, ℃ |

-0.93 |

| Monthly minimum temperature, ℃ |

-0.89 |

| Monthly maximum temperature, ℃ |

-0.31 |

| Average monthly relative humidity, % |

-0.96 |

| Monthly minimum relative humidity, % |

-0.97 |

| Maximum relative humidity in month, % |

0.70 |

Table 5.

Inhibitory effects of various agents on P. notoginseng leaf spot pathogens.

Table 5.

Inhibitory effects of various agents on P. notoginseng leaf spot pathogens.

| Treatment |

Inhibition rate range (%) |

Virulence regression equation |

EC50

|

Correlation coefficient (R2) |

| Tetramycin |

38.56–74.67 |

y=1.4x+5.31 |

0.60 (mg/L) |

0.9368 |

| copper abietate |

3.10–34.76 |

y=1.17x+0.91 |

3,120.05 (mg/L) |

0.9766 |

| α-terpineol |

24.46–72.40 |

y=1.02x+3.29 |

48.14 (μL /mL) |

0.9953 |

| WV |

1.62–78.82 |

y=3.29x-9.95 |

27,385 (mg/L) |

0.9708 |

| α-pinene |

0–13.62 |

— |

— |

— |

| T. atroviride |

52.48 |

— |

— |

— |

| T. harzianum |

44.19 |

— |

— |

— |

| B. subtilis |

78.45 |

— |

— |

— |

Table 6.

The field control efficacy of eight fungicides against P. notoginseng leaf spot disease.

Table 6.

The field control efficacy of eight fungicides against P. notoginseng leaf spot disease.

| Treatment |

Test agent |

Disease index before application |

Disease index after application |

Relative control efficiency |

| TCK |

Clear water control |

0.57±0.12 |

2.9±0.35 |

|

| T1-1 |

0.3% tetramycin |

2.45±0.41 |

3.92±1.03 |

70.2±3.24a |

| T1-2 |

0.7±0.12 |

0.89±0.16 |

69.95±9.6a |

| T1-3 |

1.54±0.38 |

3.19±1.04 |

57.72±13.35a |

| T2-1 |

20% copper rosinate |

1.94±0.25 |

2.65±0.48 |

82.57±5.42a |

| T2-2 |

1±0.26 |

1.47±0.09 |

55.05±27.7a |

| T2-3 |

0.62±0.15 |

1.11±0.27 |

59.62±16.1a |

| T3-1 |

α-terpineol |

1.37±0.3 |

2.98±0.72 |

56.83±10.83a |

| T3-2 |

1.04±0.26 |

2.52±0.61 |

49.32±13.28a |

| T3-3 |

1.27±0.32 |

2.43±0.19 |

51.92±22.66a |

| T4-1 |

α-pinene |

1.82±0.18 |

3.54±0.22 |

58.45±13.53a |

| T4-2 |

1.33±0.05 |

3.24±0.32 |

50.52±12.55a |

| T4-3 |

1.89±0.57 |

3.59±0.61 |

51.74±19.62a |

| T5-1 |

WV |

1.16±0.14 |

1.95±0.31 |

65.06±9.12a |

| T5-2 |

1.38±0.34 |

2.35±0.47 |

64.68±6.86a |

| T5-3 |

1.71±0.3 |

2.43±0.41 |

69.72±9.32a |

| T6-1 |

T. atroviride |

0.6±0.05 |

2.16±0.63 |

40.04±20.02a |

| T6-2 |

T. harzianum |

0.56±0.06 |

0.75±0.16 |

71.3±9.41a |

| T7-1 |

B. subtilis |

1.09±0.25 |

1.27±0.25 |

72.56±8.11a |